Abstract

The function of the ligamentum teres remains poorly understood, but tears have been recognized as a source of hip pain. In some patients with complete ligamentum teres tears, symptoms of instability are described. Microinstability and excess motion are hypothesized to be a source of pain and mechanical symptoms. Efforts in recent years to improve symptoms have led to the development of techniques used to reconstruct the ligamentum teres, with some early evidence that reconstruction can improve symptoms in appropriately selected patients. We describe our technique for ligamentum teres allograft reconstruction using anchors made only of suture seated in the acetabular floor.

The function of the ligamentum teres (LT) remains poorly understood. In the immature hip, the LT provides a source of vascularity,1 but in the adult hip, it has historically been thought to provide little biological or biomechanical function.2,3 However, the LT has been found to be as robust as the anterior cruciate ligament4 and becomes tightest when the hip is in a position with the least stability2—flexion, adduction, and external rotation. It is also known to possess nociceptors and mechanoreceptors,5,6 further suggesting a role far greater than that of a vestigial remnant.

There have been several recent reports establishing LT tears as a source of hip pain,7,8 successfully treated with the aid of arthroscopic debridement.7,9 Although many patients benefit from LT debridement, some authors have reported ongoing discomfort or feelings of hip instability in patients after LT resection, in positions such as extension or internal rotation or during a squat.10

Some authors have emphasized the importance of the LT in the stability of the hip joint specifically in patients with dysplasia and hyperlaxity.4,10,11 Several reported techniques for LT reconstruction have resulted in improved patient symptoms and function, specifically regarding stability symptoms.12-14

We report a novel technique using double-loaded “all-suture” anchors in the medial acetabular wall that achieves excellent stability and minimizes the risk of intrapelvic and hip joint injury, as well as complications, by metal or plastic foreign bodies (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Pearls and Pitfalls

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

Advantages of Described Technique

|

|

|

|

Technique

After a thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation suggests longstanding hip LT–related instability symptoms, the decision is made to arthroscopically reconstruct the LT. Our standard hip arthroscopy technique has been described previously.15 It is performed with the patient in the supine position on a traction table, and the bony prominences of the foot and ankle are well padded. Traction is gradually placed on the limb, and a spinal needle is inserted to break the suction seal of the hip. Once adequate working space is developed, the anterolateral and anterior portals are established to allow access to the central compartment. With a combination of 30° and 70° arthroscopes, by use of both portals, good visualization of the LT and fovea can be achieved. The surgeon first performs work in both the central and peripheral compartments, addressing all soft-tissue and bony pathology. If a complete LT tear is identified (Fig 1), the stump is cleared with a combination of ablators and shavers down to the acetabular fossa. Debridement can also be completed later using these devices through a bone tunnel drilled in the femoral head.

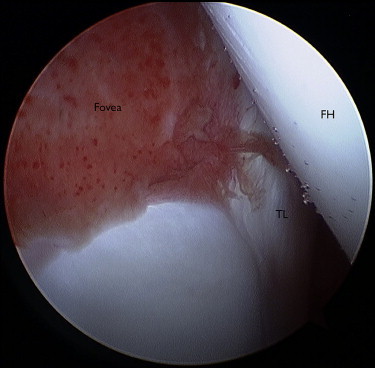

Fig 1.

Arthroscopic image of a right hip joint, viewed with a 30° 2.9-mm arthroscope from the midtrochanteric portal, showing an empty fovea with no LT visualized. Reactive synovitic tissue is seen in the cotyloid fossa. (FH, femoral head, TL, transverse ligament.)

The LT graft is prepared on the back table before any tunnel preparation or drilling. We prefer to use a thick single-stranded tibialis posterior or double-stranded semitendinosus allograft with a diameter of approximately 8 mm. Once the graft is prepared, it is left on the Graftmaster (Acufex Graftmaster III, Smith & Nephew, Andover, MA) to allow pre-tensioning. The femoral tunnel line is then chosen under fluoroscopic guidance and direct visualization, and a 2-cm incision is made laterally over the greater trochanter at the entry point. An anterior cruciate ligament–type guidewire is drilled, and when appropriately placed, a 1:1 (graft diameter–to–drill diameter) anterior cruciate ligament drill (VersiTomic rigid drilling system; Stryker, Mahwah, NJ) is drilled over the guidewire to exit in the center of the femoral head–LT attachment at the middle of the fovea capitis (Video 1). We always use a dilator (VersiTomic rigid drilling system) to make sure that the tunnel width is adequate for our graft and to compact and smooth the inner tunnel walls. Soft tissue is cleared from the lateral cortex of the greater trochanter to avoid possible interposition and difficulty in shuttling the graft. A plug (Tibial Plug; Stryker) is placed in the bone tunnel to prevent fluid escape while the remainder of the tunnel preparation is undertaken.

The acetabulum is next approached, first by clearing soft tissue from the footprint of the LT in the posteroinferior aspect of the cotyloid fossa. A burr (5.5-mm hip burr; Stryker) is used to superficially decorticate the footprint to allow a good bleeding bed for bone ingrowth (Figs 2A and 2B), with care taken not to remove excess bone and thin the acetabular wall excessively. The use of burring also ensures that there is adequate space available for the LT with the hip in a neutral position. The first anchor position must be carefully pre-planned, and using curved drill guides (Stryker) can be very helpful. This technique allows the surgeon to drill the acetabular anchors either through the femoral tunnel or through the hip joint itself, enabling optimal positioning. The first 2.3-mm double-loaded all-suture anchor (Iconix, No. 5 ultra-strength wire; Stryker) is then drilled at a location planned to be the center of the reconstructed LT (Fig 2C). The anchor drill is advanced slowly through the acetabular wall (approximately 6 to 8 mm in depth). When the surgeon believes that the medial cortex is about to be breached, using fluoroscopy, he or she maintains minimal forward pressure on the drill to avoid plunging into the pelvis, potentially damaging the obturator vessels. It is important to alert the anesthesia team to watch for changes in the patient's vital signs while acetabular drilling is under way. Once the drill hole is established, the anchor is shuttled through the drill guide to penetrate the medial cortex (Fig 2D). The anchor is deployed to form an all-suture knot on the medial side of the cortex (rather than in a bone tunnel, which is typically used in the acetabular rim). To avoid suture entanglement in the femoral head–neck bone tunnel, only one limb should be kept in the tunnel at a time and the other limbs should be shuttled through the joint, to be used later. A second anchor is then placed in a similar fashion, at least 5 mm away from the first anchor. The direction of drilling should be changed to avoid tunnel convergence; this can be achieved either by changing femoral rotation or by drilling through the joint.

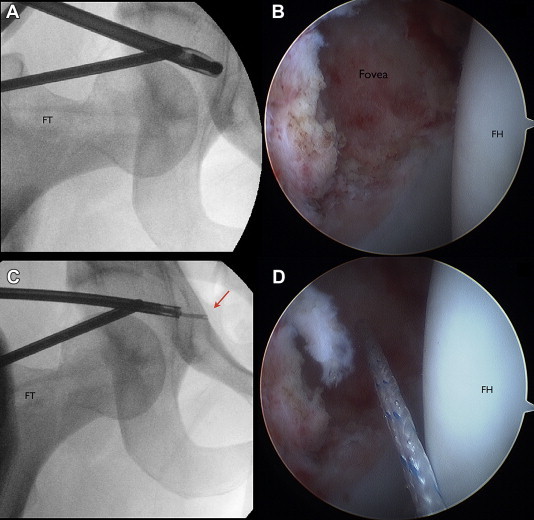

Fig 2.

Intraoperative fluoroscopic and arthroscopic images of a right hip, viewed with a 30° 2.9-mm arthroscope from the midtrochanteric portal. (A) A burr is used to prepare the bony bed at the origin of the LT. (B) The fovea is ready to accept the graft, with a bleeding bony bed. (C) The curved (12°) Iconix guide is leading a 2.3-mm all-suture anchor to the medial cortex (within the pelvis), which will serve as the point of fixation for the LT graft (arrow). (D) Suture coming out of anchor. (FH, femoral head; FT, femoral tunnel.)

The graft is shuttled in an outside-in manner through the bone tunnel (Figs 3A-3C). If a single-stranded graft is used, 1 end of the suture is passed a few times with a free needle through 1 side of the graft, with one-third of the suture being left free for later knot tying. If a double-stranded graft is used, the needle is passed through the center of the graft. The surgeon pulls on the other end of the suture (the joint side), which shuttles the graft into the joint until it seats in the acetabular footprint. A knot pusher can be positioned over the short end (tunnel side) of the suture to assist in graft advancement. Once the graft has been successfully shuttled into the footprint, the tunnel side of the suture is retrieved from the joint side and the LT graft is secured by tying a knot. A SpeedStitch device (ArthroCare, Austin, TX) is then used to pass the other 3 sutures (1 from the first anchor and 2 from the additional anchor) through the base of the graft (Figs 3D and 3E). This allows increased surface contact between the graft and bony bed (Fig 4). The advantage of the SpeedStitch device is that it functions as both a grasper and a suture passer, allowing accurate suture passage with relative ease.

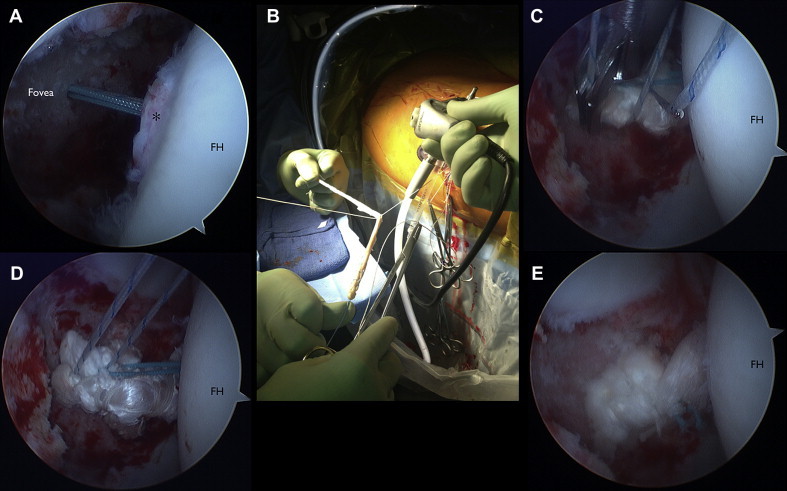

Fig 3.

Arthroscopic images of a right hip, viewed with a 30° 2.9-mm arthroscope from the midtrochanteric portal. (A) Double-loaded 2.3-mm all-suture anchor passing through femoral tunnel. The asterisk indicates the remnant of the LT. (B) A double-stranded graft is shuttled through the femoral tunnel by tying a limb of 1 suture to the midpoint of the graft and drawing it in with tension on the other end of the suture. An arthroscopic knot is then tied. (C) The SpeedStitch device is used to pass the additional sutures through the graft. (D) The sutures are tied. (E) Graft tension while in external rotation of femoral head (FH).

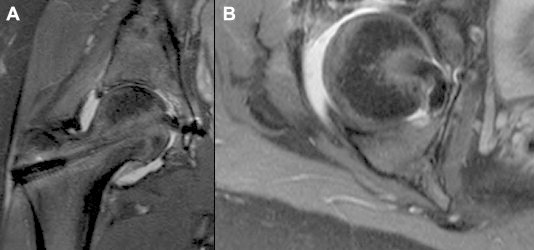

Fig 4.

Magnetic resonance images of right hip obtained 6 weeks after arthroscopic LT reconstruction, showing graft position: coronal (A) and axial (B) views. The axial view shows the wide origin of the new LT creating a large amount of surface contact with the lateral cortex's bony bed.

Once the graft is secured to the fossa, its position is checked through hip range of motion both with and without traction. Traction is released, and the graft is tensioned and secured in the femur with an interference screw (Stryker) when the femur is placed in slight extension and extreme external rotation (50° to 60°). The wounds are washed and closed in a standard fashion after the excess graft is cut at the lateral femoral cortex. Postoperatively, a brace is secured to avoid extension and external rotation, and physical therapy is begun immediately in the brace with passive range of motion to avoid intra-articular adhesions. Weight bearing is restricted to “toe touch” for the first 2 weeks, and partial weight bearing is then commenced, for 4 more weeks. Return to play is allowed at 5 months postoperatively.

Discussion

We have described our technique for reconstruction of the LT. Hip preservation experts are still defining the indications for LT reconstruction. It is established that injury to the LT can be a source of hip pain.7,8 Reports in the literature described the incidence of LT tears seen on hip arthroscopy as between 4% and 17.5%,2 but a recent study found tears in 51% of patients who underwent hip arthroscopy.16 The authors suggested that the improved understanding of LT tears has allowed a better arthroscopic assessment and more accurate diagnosis.

The vast majority of patients with LT tears respond well to debridement7,17 because even complete disruption of the LT typically presents as pain, not instability.7 Only when debridement has failed to result in a good outcome, when instability is the primary symptom, and after concomitant pathology such as femoroacetabular impingement, labral tears, or patulous capsular tissue has been addressed should LT reconstruction be considered.13

There are several benefits to our technique using all-suture anchors. It allows reconstruction of the LT without the use of metal or plastic anchors that, if dislodged—whether inside the joint or into the pelvis—could cause significant harm to the patient. Furthermore, the curved design of the all-suture drill guides used enables anchor placement independent of the location or orientation of the femoral tunnel. This gives the surgeon more control over the position of the graft in the cotyloid notch and improves safety by allowing the surgeon more freedom to avoid the critical structures medial to the acetabulum. It also allows placement of secondary anchors with relative ease adjacent to the primary anchor, allowing the graft a wider footprint for ingrowth. A strong understanding of advanced hip arthroscopic techniques and the anatomy of the pelvis is necessary when one is performing any LT reconstruction technique.

The understanding of the function of the LT will continue to grow, and the indications for reconstructions will continue to be refined. Further studies are needed to clarify the indications and limitations of LT reconstruction. We have found the described technique safe and reproducible in appropriately selected patients.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: O.M-D. receives support from University of Colorado and ArthroCare.

Supplementary Data

Step-by-step surgical guide for our LT reconstruction technique with both Sawbones (Pacific Research Laboratories, Vashon, WA) and arthroscopic demonstrations.

References

- 1.Trueta J. The normal vascular anatomy of the human femoral head during growth. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39:358–394. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.39B2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardakos N.V., Villar R.N. The ligamentum teres of the adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:8–15. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapandji I.A. The physiology of the ligamentum teres. In: Kapandji I.A., editor. Ed 2. Volume 2. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1978. p. 42. (The physiology of the joints). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenger D., Miyanji F., Mahar A. The mechanical properties of the ligamentum teres: A pilot study to assess its potential for improving stability in children's hip surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:408–410. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000271332.66019.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leunig M., Beck M., Stauffer E., Hertel R., Ganz R. Free nerve endings in the ligamentum capitis femoris. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:452–454. doi: 10.1080/000164700317381117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarban S., Baba F., Kocabey Y., Cengiz M., Isikan U.E. Free nerve endings and morphological features of the ligamentum capitis femoris in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;16:351–356. doi: 10.1097/01.bpb.0000243830.99681.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd J.W., Jones K.S. Traumatic rupture of the ligamentum teres as a source of hip pain. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray A.J.R., Villar R.N. The ligamentum teres of the hip. An arthroscopic classification of its pathology. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:575–578. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haviv B., O'Donnell J. Arthroscopic debridement of the isolated ligamentum teres rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1510–1513. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1318-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin R.L., Palmer I., Martin H.D. Ligamentum teres: A functional description and potential clinical relevance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1209–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1663-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindner D., Sharp K.G., Trenga A.P., Stone J., Stake C.E., Domb B.G. Arthroscopic ligamentum teres reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2:e21–e25. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amenabar T., O'Donnell J. Arthroscopic ligamentum teres reconstruction using semitendinosus tendon: Surgical technique and an unusual outcome. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;1:e169–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philippon M.J., Pennock A., Gaskill T.R. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the ligamentum teres: Technique and early outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1494–1498. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.28576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson J.M., Field R.E., Villar R.N. Arthroscopic reconstruction of the ligamentum teres. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:436–441. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mei-Dan O., McConkey M.O., Young D. Hip arthroscopy distraction without the use of a perineal post. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e1–e5. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20121217-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Botser I.B., Martin D.E., Stout C.E., Domb B.G. Tears of the ligamentum teres. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:117S–125S. doi: 10.1177/0363546511413865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto Y., Usui I. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative rupture of the ligamentum teres femoris. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:689.e1–689.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.04.116. www.arthroscopyjournal.org Available online at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Step-by-step surgical guide for our LT reconstruction technique with both Sawbones (Pacific Research Laboratories, Vashon, WA) and arthroscopic demonstrations.