Abstract

Traumatic hip dislocations are associated with chondral and labral pathology as well as loose bodies that can be incarcerated in the joint. These types of injury often lead to traumatic arthritis. In some cases an osseo-labral fragment may become incarcerated in the joint that is not readily visualized preoperatively. In place of open surgery, hip arthroscopy permits a technique to remove loose bodies and repair labral tears to restore joint congruity and achieve fracture reduction and fixation.

It is well known that hip fracture-dislocations typically cause loose bodies. These are often found on post-reduction computed tomography (CT) scans or with radiographic evidence of incongruity. The incidence of loose bodies associated with hip fracture-dislocations has been reported to be as high as 81%.1 The pattern of labral pathology with hip dislocations is not well understood. However, bucket-handle labral tears have been previously reported.2, 3 The incidence of post-traumatic arthritis in hip dislocations is as high as 24% with simple dislocations (no fracture), and even higher rates have been reported with fracture-dislocations.1, 4, 5, 6 Acetabular fractures are commonly fixed through an extra-articular approach or with surgical dislocation. However, these approaches have increased rates of complications and morbidity compared with modern hip arthroscopy techniques. There is scant literature on the reduction and internal fixation of acetabular fractures arthroscopically. A recent case report described 2 cases of superior rim fractures in athletes associated with femoroacetabular impingement.7 In those cases the fractures were fixed with cannulated screws placed extra-articularly by arthroscopic visualization.

In this article we present a 46-year-old woman involved in a motor vehicle collision who sustained a posterior acetabular fracture-dislocation with incarcerated loose bodies and an osseous bucket-handle labral tear.

Surgical Technique

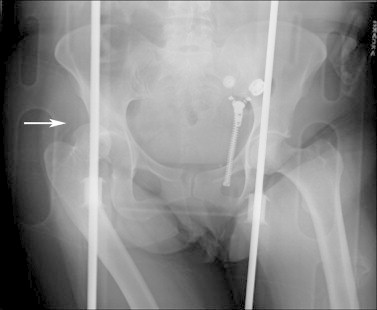

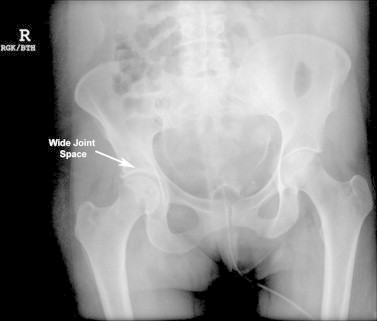

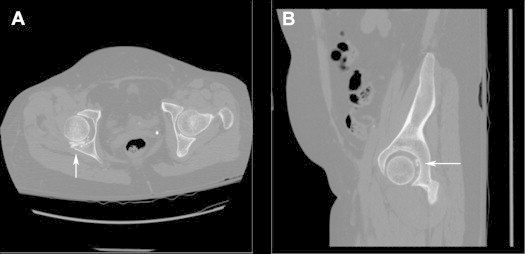

Plain radiography showed a right hip posterior fracture-dislocation (Fig 1). The dislocation was reduced within 2 hours of injury, after which the patient was transferred to our level 1 trauma center for definitive workup and treatment. Post-reduction radiographs and CT scans were obtained and showed malreduction of the right hip (Fig 2) with incarcerated osseo-labral fragments (Fig 3). The patient was placed in skeletal traction through the tibia to minimize chondral injury and to maintain reduction of the hip. After her associated injuries were addressed and she was cleared for surgery by the trauma service, it was decided that she would benefit from arthroscopic management of the incarcerated fragments. The indications and contraindications for arthroscopic treatment of a bucket-handle labral tear and acetabular fracture are detailed in Table 1.

Fig 1.

Radiograph of anteroposterior view from outside hospital showing fracture-dislocation (arrow) of right hip and acetabulum.

Fig 2.

Preoperative radiograph of anteroposterior view of reduced right hip. The increased joint space on the right implies incarcerated fragments.

Fig 3.

Preoperative CT scans show incarcerated fragments (arrows) that are easily visible on (A) axial and (B) sagittal views.

Table 1.

Indications and Contraindications for Arthroscopic Treatment of Bucket-Handle Labral Tear and Acetabular Fracture

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

|

|

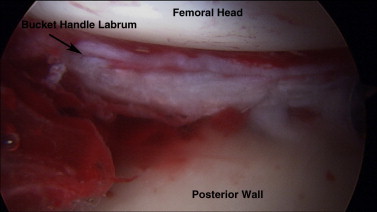

A right hip arthroscopy was pursued to extract the osseous fragments, reduce and internally fix the acetabulum, and repair the labrum. The patient was placed in a supine position with adequate traction to distract the joint. The hip was prepared and draped in the standard fashion. A 3-portal technique with a 70° arthroscope was used: anterolateral, mid anterior, and posterolateral. The steps of the technique and associated pearls are detailed in Table 2. The surgical technique is detailed in Video 1. Intraoperative assessment showed a bucket-handle tear of the posteroinferior labrum with osseous attachment and joint incarceration at the 7-o'clock to 10:30 clock-face position (Fig 4). There was also marginal impaction and contusion of the posterior acetabular wall, 7 × 16 mm, at the 8- to 10-o'clock position. Two osseous fragments were found in the central compartment, approximately 8 × 5 mm each. In addition, there was fraying of the superior labrum consistent with possible chronic pincer impingement at the 11-o'clock to 12:30 clock-face position.

Table 2.

Technical Steps and Pearls for Arthroscopic Treatment of Bucket-Handle Labral Tear and Acetabular Fracture

| Steps | Pearls |

|---|---|

| Preoperative CT |

|

| Diagnostic arthroscopy |

|

| Reduction |

|

| Fixation |

|

| Femoroacetabular impingement |

|

| Postoperative |

|

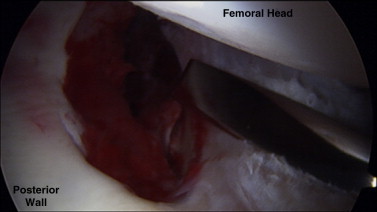

Fig 4.

Arthroscopic view of right hip through anterolateral viewing portal. The femoral head, posterior wall of the acetabulum, and bucket-handle tear of the labrum are well visualized.

Loose bodies were excised with a pituitary grasper. The bucket-handle labral tear had an attached osseous fragment that was reduced under direct visualization with the use of a switching stick (Figs 5 and 6). The amount of bony deficit across the posterior acetabulum was estimated to be approximately 25% to 30%. Therefore an effort was made to preserve the labrum that had been detached from the posterior acetabulum. The labrum was repaired to the posterior acetabulum from the 7- to 10-o'clock position with 3 anchors posteroinferiorly: two 2.9-mm polylactic acid–hydroxyapatite anchors and one 5.5-mm polylactic acid–hydroxyapatite anchor (Fig 7). The labrum was subsequently refixed by use of 2 looped sutures. The 5.5-mm anchor was used more posterosuperiorly and was also attached to the labrum by use of a loop suture construct. The refixation of the labrum incorporated the still attached labral-chondral fragment (Fig 8). No additional treatment was performed for the osteochondral lesion because the underlying bony surface was trabecular and bleeding. Labral fraying and grade 1 chondromalacia were treated with debridement and chondroplasty, respectively. In this setting it is important to identify and address any femoroacetabular impingement. If this is missed, it can subsequently place increased stress on the repair and lead to failure of the repair. In our patient there was, in fact, evidence of chronic impingement, and therefore to protect the labral repair posteriorly, an osteoplasty was performed across the head-neck junction using an arthroscopic shaver and arthroscopic burr. The ligament of Weitbrecht and the retinacular vessels were identified and protected throughout the case. General taper concavity was assessed by dynamic examination including flexion, extension, internal rotation, external rotation, abduction, and adduction. Repeat inspection within central compartment showed the labral refixation to be stable. Dynamic examination with the patient under anesthesia showed the hip to be stable with flexion, extension, internal rotation, external rotation, abduction, and adduction. There was no evidence of subluxation or instability. The patient was subsequently placed in an anti-rotation position with a bolster pillow.

Fig 5.

Arthroscopic view of right hip through anterolateral viewing portal showing intra-articular reduction maneuver for labral-chondral fragment. A switching stick (not shown) was also used in performing reduction of the fragment.

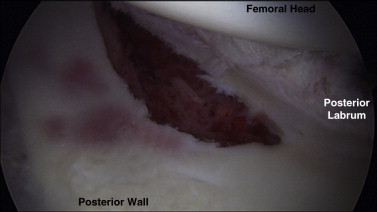

Fig 6.

Arthroscopic view of right hip through anterolateral viewing portal showing reduced labral-chondral fragment. Chondral contusions on the posterior acetabular wall as a result of initial trauma are well visualized.

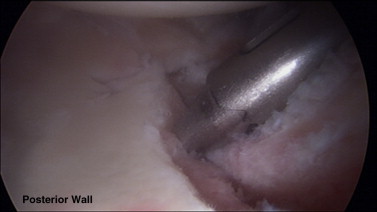

Fig 7.

Arthroscopic view through anterolateral portal showing anchor placement for stabilization of labral-chondral fragment.

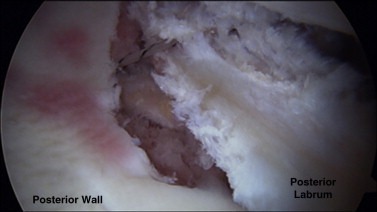

Fig 8.

Arthroscopic view of final fixation from anterolateral portal of labral-chondral fragment showing refixation of labrum.

Postoperatively, the patient was allowed flat-foot weight bearing of up to 20 lb and performed continuous passive motion exercises for 8 weeks on the affected side. She was also given naproxen sodium for 6 weeks for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis and enoxaparin for 2 weeks as deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

Discussion

In this technical note we have described an incarcerated osseo-labral fragment that was reduced and underwent labral repair with arthroscopic anchors in an acute setting. The incidence and pattern of labral and chondral injury associated with traumatic hip dislocation are not known. Loose bodies have been shown to play a role in chondral degeneration.8 However, radiographs are not as sensitive as CT scans for evaluating joint congruity.

Baird et al.9 showed in a cadaveric study that radiolucent 4-mm cubes placed in the hip could not be seen radiographically whereas 2-mm cubes were detected on CT scans. Dameron3 reported on a hip fracture-dislocation and subsequent bucket-handle tear of the labrum. Radiographs in this case showed increased joint space after initial closed reduction. Mullis and Dahners10 found that 7 of 9 hip dislocation patients had loose bodies although no loose bodies were detected preoperatively and the joints were congruent on imaging. This illustrates that conventional radiographs and CT scans do not depict the extent of chondral or labral pathology associated with traumatic hip dislocation. Ilizaliturri et al.2 performed hip arthroscopy in 17 patients with post-traumatic hip dislocation who continued to have mechanical symptoms after reduction. Among these patients, Ilizaliturri et al. found 14 anterior labral tears and 6 posterior labral tears and a high incidence of chondral injury for both the acetabulum and femoral head. From these results, they advocated performing hip arthroscopy in patients who have had traumatic hip dislocations and continue to have associated mechanical symptoms and loose bodies after reduction. However, hip arthroscopy is associated with complications such as sciatic nerve palsy, scrotum pressure wound, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, and fluid extravasation. Trauma patients pose multiple challenges to performing hip arthroscopy. This includes patients with same-side trauma that precludes application of traction necessary for hip arthroscopy. In addition, trauma patients are particularly vulnerable to fluid extravasation because of multiple injuries and abdominal injuries, as well as the trauma to the capsule and hip joint. Bartlett et al.11 reported a case of acetabular fracture of both columns in which intra-abdominal compartment syndrome developed and, subsequently, cardiac arrest occurred more than 2 hours into hip arthroscopy to remove a loose body. Hip arthroscopy cannot be advocated for every patient who has a traumatic hip dislocation. However, hip arthroscopy instead of open dislocation is an option for loose body removal and labral repair associated with traumatic hip dislocations. This technical note shows that posterior hip dislocations may result in malreduction due to loose bodies and osseo-labral incarceration that are not shown on preoperative imaging.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: K.J.S. receives support from Smith & Nephew Endoscopy, Wake Forest Baptist Health. S.M. receives support from Wake Forest Innovations Spark Award and Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation (OREF) Resident Clinician Scientist Award. A.J.S. receives support from Smith & Nephew Endoscopy, Bauerfiend AG, Johnson & Johnson (stockholder).

Supplementary Data

Right hip arthroscopy with patient in supine position with adequate traction. A 3-portal technique (anterolateral, mid anterior, and posterolateral) with a 70° arthroscope was used to extract the osseous fragments, reduce and internally fix the acetabulum, and repair the labrum.

References

- 1.Epstein H.C. Traumatic dislocations of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;92:116–142. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilizaliturri V.M., Jr., Gonzalez-Gutierrez B., Gonzalez-Ugalde H., Camacho-Galindo J. Hip arthroscopy after traumatic hip dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(suppl):50S–57S. doi: 10.1177/0363546511411642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dameron T.B., Jr. Bucket-handle tear of acetabular labrum accompanying posterior dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein H.C. Posterior fracture-dislocations of the hip; long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1103–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhyay S.S., Moulton A. The long-term results of traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63:548–551. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B4.7298682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyay S.S., Moulton A., Srikrishnamurthy K. An analysis of the late effects of traumatic posterior dislocation of the hip without fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65:150–152. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.65B2.6826619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson C.M., Stone R.M. The rarely encountered rim fracture that contributes to both femoroacetabular impingement and hip stability: A report of 2 cases of arthroscopic partial excision and internal fixation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1018–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans C.H., Mazzocchi R.A., Nelson D.D., Rubash H.E. Experimental arthritis induced by intraarticular injection of allogenic cartilaginous particles into rabbit knees. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:200–207. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird R.A., Schobert W.E., Pais M.J. Radiographic identification of loose bodies in the traumatized hip joint. Radiology. 1982;145:661–665. doi: 10.1148/radiology.145.3.7146393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullis B.H., Dahners L.E. Hip arthroscopy to remove loose bodies after traumatic dislocation. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:22–26. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000188038.66582.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartlett C.S., DiFelice G.S., Buly R.L., Quinn T.J., Green D.S., Helfet D.L. Cardiac arrest as a result of intraabdominal extravasation of fluid during arthroscopic removal of a loose body from the hip joint of a patient with an acetabular fracture. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:294–299. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199805000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Right hip arthroscopy with patient in supine position with adequate traction. A 3-portal technique (anterolateral, mid anterior, and posterolateral) with a 70° arthroscope was used to extract the osseous fragments, reduce and internally fix the acetabulum, and repair the labrum.