Abstract

Diverse etiologic events are associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. During hepatocarcinogenesis, genetic events likely occur that subsequently cooperate with long-term exposures to further drive the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. In this study, the frequent loss of the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma was modeled in response to diverse hepatic stresses. Loss of RB did not significantly affect the response to a steatotic stress as driven by a methionine- and choline-deficient diet. In addition, RB status did not significantly influence the response to peroxisome proliferators that can drive hepatomegaly and tumor development in rodents. However, RB loss exhibited a highly significant effect on the response to the xenobiotic1,4-Bis-[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene. Loss of RB yielded a unique proliferative response to this agent, which was distinct from both regenerative stresses and genotoxic carcinogens. Long-term exposure to 1,4-Bis-[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene yielded profound tumor development in RB-deficient livers that was principally absent in RB-sufficient tissue. These data demonstrate the context specificity of RB and the key role RB plays in the suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma driven by xenobiotic stress.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the predominant manifestation of primary liver cancer and represents the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.1 HCC is unique among cancers in that most cases can be traced to diverse high-risk etiologic events.2 Unlike lung cancer or melanoma, wherein smoking or solar exposure are predominating risks, for HCC, multiple etiologic events can be driving the disease.1,2 Hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infections have diverse effects on liver biology but are the primary etiologic events for HCC.2 Similarly, chronic alcoholism progressing to liver cirrhosis is a well-known etiologic event for HCC. Exposure to environmental carcinogens, such as aflatoxin B1, can also lead to HCC1; furthermore, with the obesity epidemic, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis is anticipated to be a significant etiologic factor for HCC.3

Despite the diversity of etiologic events, the prevailing model for the development of HCC is that these processes lead to mutational or epigenetic changes in cells of the liver that initiate tumor development and facilitate disease progression.1,4–7 One would expect that given the chronic nature of HCC development, specific genetic events occurring early in the disease could subsequently alter the cellular response to etiologic events and thereby contribute to disease initiation and progression. A key genetic event in the etiology of HCC is loss of heterozygosity at 13q, which occurs in approximately 20% of liver cancers.8 This locus encodes the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor, RB1, and sequencing, and other approaches have indicated that mutation or homozygous deletion of RB1 occurs relatively frequently in disease.9,10 RB is a key negative regulator of cell cycle. Our group and others have found that RB1 loss plays a key role in deregulating the response to genotoxic carcinogens, allowing for inappropriate response to hepatocarcinogens, such as aflatoxin B1 and diethyl nitrosamine (DEN).11,12 This loss of cell cycle control is associated with increased tumor burden in mice treated with such agents.11,13,14 These results reinforced the concept that RB is a functional tumor suppressor in mouse models. Interestingly, RB1 loss in combination with the potent oncogene MYC had veritably no effect on tumor development.15 In addition, in combination with TP53 loss, RB deficiency only served to enhance genotoxic-driven tumor development.16 Therefore, whether the effects of RB deficiency are specifically related to genotoxic stresses or generally applicable to hepatocarcinogenesis remains unknown.

In rodent models, as in humans, there are multiple pathways to HCC development.17–19 A variety of DNA-damaging agents, such as DEN, are known genotoxic hepatocarcinogens. However, long-term exposure to a number of additional agents can lead to HCC in mice through diverse mechanisms. For example, to mimic metabolic dysfunction, mice are fed specific diets, such as a methionine choline–deficient diet, to induce fatty liver.17 Similarly, there are xenobiotics, such as phenobarbital and 1,4-Bis-[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene (TCPOBOP), that modulate the constitutive androstane receptor to drive liver tumorigenesis.17,20 Lastly, there are synthetic peroxisome proliferators that serve as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists that are potent rodent carcinogens.18,21 Although the human relevance of some rodent carcinogen models is debatable, such models allow the ability to decipher the interaction between genetic events and facets of liver biology that are clearly germane to human disease (eg, fatty or cirrhotic liver). We investigated how RB1 status influences the response to multiple nongenotoxic carcinogenic stresses in mouse models. These findings indicate that RB has stress context–specific activities but can serve to restrain tumor development driven by nongenotoxic carcinogens.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Generation

Mice with liver-specific deletion of RB1 (Rb1f/f;Alb-cre+) and genetically similar controls without Cre-mediated recombination (Rb1f/f) were used in this study. All mice were 8 weeks old at the time of analysis or the beginning of time course experiments. The generation and genotyping of these mice have been discussed previously.22 All experiments and protocols were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 8th edition (NIH) and were approved by Thomas Jefferson University.

TCPOBOP Compound

TCPOBOP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 0.6 mg/mL. The experimental solution was kept at room temperature in a light-restricted container for no longer than 6 months.

Wy-14,643 Compound and MCDD

Wy-14,643 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide, and mice were given a 40 mg/kg dose (in corn oil) every 24 hours via gavage for either 72 hours or 2 weeks, accordingly. The methionine- and choline-deficient diet (MCDD) was purchased from Test Diet (St. Louis, MO) and made specific to our needs.

Short-Term Carcinogen Treatment

For acute TCPOBOP, DEN, and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) treatments, 8-week-old Rb1f/f and Rb1f/f and Alb-cre+ littermates received a single i.p. injection of 3 mg/kg TCPOBOP, 20 mg/kg DEN, or 10% CCl4 in corn oil. TCPOBOP vehicle mice received an injection of an equivalent amount of corn oil. Treated animals and matched controls were sacrificed 24 (DEN), 48 (CCl4), 72, or 216 hours after treatment. Body and liver weights were measured, and tissue was separated for genotyping, sectioning, and protein extraction. Tissue harvesting and preparation were performed as previously described.22 Genetically similar mice received a special MCDD, whereas vehicle mice continued to receive regular chow. Mice were kept on the diet consistently for 2 weeks. The mice were fasted 24 hours before sacrifice, yet they still had unrestricted access to water during this time. At the time of sacrifice, mice were weighed and photographed, and then livers were excised, weighed, and imaged in the same manner. Mice treated with the PPARα8 activator Wy-14,643 received the drug via gavage once a day for either 72 hours or 2 weeks. Vehicle mice received an equivalent amount of corn oil for the same duration. For all treatments, a subset of mice received a single i.p. injection of 150 mg/kg 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in saline 1 hour before sacrifice.

Long-Term TCPOBOP Treatment

Rb1f/f and Rb1f/f;Alb-cre+ littermates were aged to 8 weeks and then given long-term biweekly injections of TCPOBOP for 24 weeks for a total of 12 injections. Experimental animals were then sacrificed 5 weeks after the last TCPOBOP injection. Control animals were aged to 32 weeks and sacrificed in the same manner as experimental animals. As described above, body and liver weights were measured, and liver tissue was harvested in the same fashion. Tumor burden was noted by counting visible, resectable tumors before harvesting. In some cases, tumor tissue was excised from the liver and harvested for separate analysis. Images were also obtained from each liver for further analysis.

IHC, Immunofluorescence, and Immunoblotting

After sacrifice, the left lobe of the liver was fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and mounted in paraffin wax for sectioning. Each liver was sectioned at 5 μm and used as follows. Commercially available monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) to analyze DNA synthesis, phospho-histone H3 S10 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) to monitor mitotic progression, and Ki-67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for proliferation analysis were used for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. IHC staining protocols have been previously described.16,22 H&E staining was performed via a standard protocol. Other sections of the liver were flash frozen for protein extraction. Liver nuclei protein preparation and immunoblotting techniques were previously described. Immunoblot antibodies were commercially available: PCNA (P-10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX), MCM7 (141.2; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and Lamin B (M-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Statistical Analysis

Slides were scored in a blind fashion for at least 600 hepatocytes from several fields for each staining. For histologic assessment, a veterinary pathologist scored slides in a blind fashion (A.W.). Statistical significance between groups was calculated with a 2-tailed unpaired t-test. Differences were classified as statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

RB Status Has Limited Effect on Histologic Response to Diverse Hepatic Stressors

Distinct etiologic events promote human liver cancer.1,2 To determine how the loss of RB1 in the liver may impinge on the response to diverse carcinogenic stresses, we used Rb1f/f and Rb1f/f;Alb-cre mice. We have previously demonstrated the effective liver-specific deletion of RB in this model.22 These mice were exposed to three agents: i) TCPOBOP, a potent xenobiotic constitutive androstane receptor agonist that can initiate and promote tumor development4; ii) MCDD, which induces fatty liver in mice23; and iii) the PPARα/γ activator Wy-14,643, which is a potent mitogen and carcinogen in rodent models.17

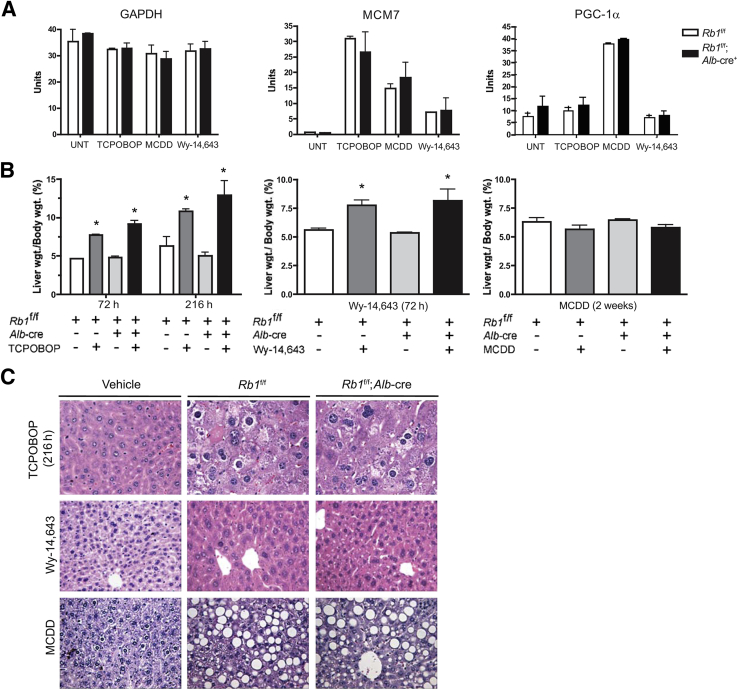

To probe the molecular response to each stress, we initially investigated specific targets associated with proliferation and fat accumulation. To monitor proliferation-associated transcription, MCM7 RNA levels were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. TCPOBOP resulted in significantly increased MCM7 RNA levels when compared with the control mice (Figure 1A). The MCDD and treatment with Wy-14,643 also induced MCM7 expression, albeit to a lesser extent. Pgc1α is a marker for fatty deposits in the liver and was used to delineate molecular events associated with fatty liver. TCPOBOP and Wy-14,643 had no effect on PGC-1α (official symbol, PPARGC1A) expression, whereas MCDD significantly induced this gene associated with lipid metabolism (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mice with RB-sufficient and RB-deficient livers were treated with TCPOBOP, Wy-14,643, and MCDD. A: Effects on gene expression as determined by real-time PCR analysis. B: Excised livers were weighed and normalized to body weight. For each condition, at least five livers were measured. C: Representative images of liver tissue from mice treated with TCPOBOP, Wy-14,643, and MCDD stained with H&E. Data are presented as means ± SD (A and B). ∗P < 0.05 versus untreated as determined by Welch's t-test. Original magnification: ×20. UNT, untreated.

To examine the effect of RB loss on tissue homeostasis, mice were sacrificed and livers were weighed before histologic processing (Figure 1B). As expected, Wy-14,643 significantly increased liver mass (P < 0.05). MCDD had little overall effect on liver weight. In neither case was liver weight significantly influenced by RB1 status. At both 72 and 216 hours after TCPOBOP exposure, RB-deficient and control mice displayed a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in liver weight compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 1B). Further histologic analysis of liver sections after treatments yielded expected phenotypes (Figure 1C). MCDD resulted in massive accumulation of fat deposits in the livers generating steatosis, whereas Wy-14,643 had minimal effect on liver histologic findings but induced mild dysplasia with some nuclear atypia. TCPOBOP induced significant dysplasia with pleomorphic nuclear features. In no case were these histologic manifestations significantly altered by RB status (Figure 1C).

RB Loss Specifically Uncouples the Cellular Response to TCPOBOP

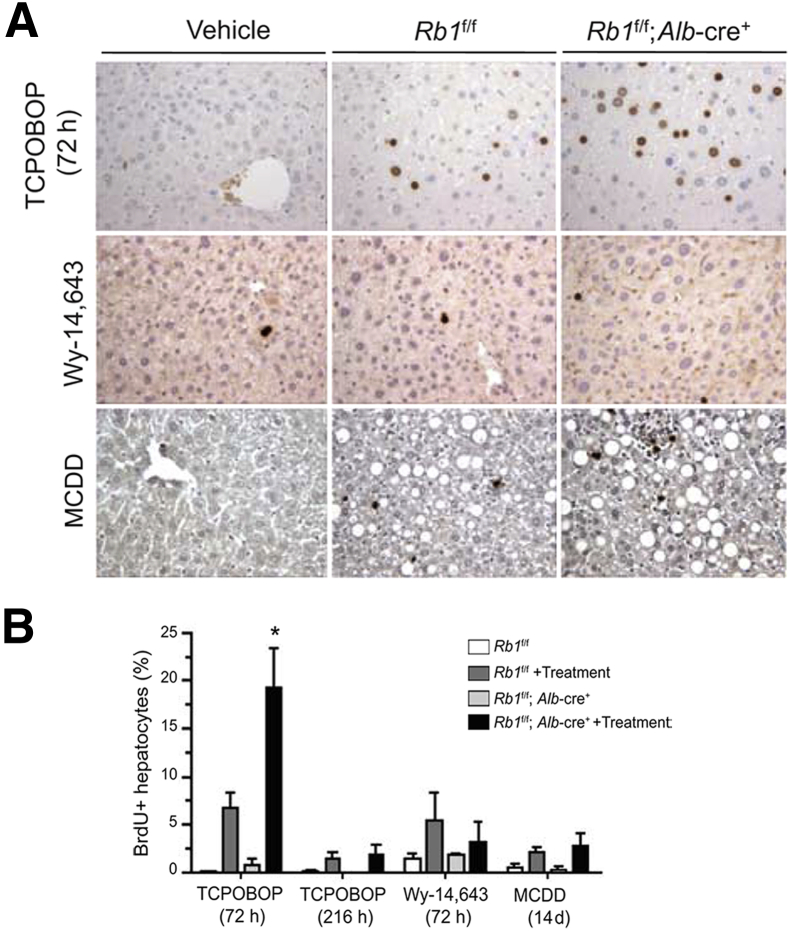

Cell cycle progression was measured in liver tissue to better elucidate the influence of RB1 status on the phenotypic response to each of the stresses. All animals were labeled with BrdU 1 hour before sacrifice. Despite the profound effect of Wy-14,643 on liver size, it resulted in modest induction of proliferation at 72 hours after treatment. This increase in proliferation was not affected by RB1 status (Figure 2, A and B). The proliferative response was transient; at 2 weeks after Wy-14,643 treatment, livers had returned to a basal level of proliferation via BrdU analysis (data not shown). Mice given MCDD exhibited a limited increase in proliferation as determined by BrdU incorporation, which was similarly unaffected by the presence of RB (Figure 2, A and B). These combined data suggest that RB1 status has little effect on the liver under the effects of Wy-14,643 or MCDD. In contrast, TCPOBOP-treated livers had significant (P < 0.05) deregulation of proliferation with RB-deficient livers demonstrating a twofold increase in BrdU incorporation compared with the RB-sufficient livers. This effect was transient, and all proliferation returned to basal levels by 216 hours after treatment (Figure 2, A and B). However, livers remained large and exhibited little apoptotic cell death after TCPOBOP treatment (not shown). These data suggest that RB deficiency has a particular effect on the response to TCPOBOP.

Figure 2.

Mice with RB-sufficient and RB-deficient livers were treated with TCPOBOP, Wy-14,643, and MCDD. A: Representative images show the effects on proliferation as determined by BrdU incorporation. B: Quantitation of BrdU incorporation from mice treated with the agents for the times indicated. All data are from at least five livers. Data are presented as means ± SD. ∗P < 0.05 versus TCPOBOP-treated RB-sufficient livers as determined by Welch's t-test. Original magnification: ×20 (A).

TCPOBOP Impinges on RB Pathways in a Unique Fashion

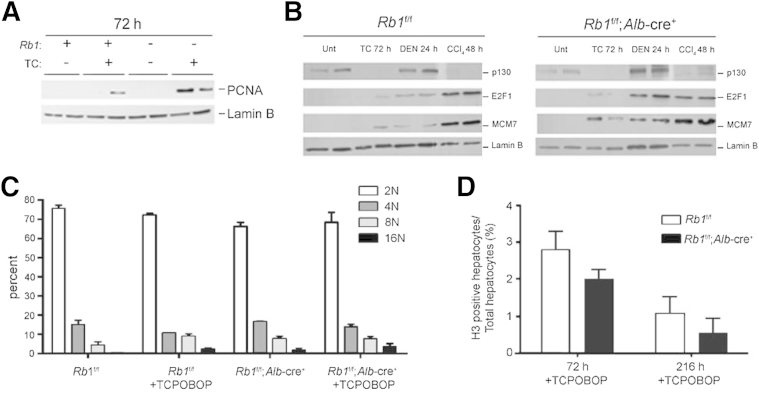

Prior work has described pathways through which discrete stresses affect proliferative pathways to drive cell cycle progression.13,24 To understand the signaling involved distal to TCPOBOP exposure, levels of key proteins involved in cell cycle control in the liver were evaluated. Consistent with the enhanced proliferation, we observed that the E2F-regulated protein PCNA was significantly stimulated in RB-deficient livers exposed to TCPOBOP, relative to RB-sufficient controls (Figure 3A). We have previously reported that two pathways lead to the stimulation of E2F target genes, one being the canonical regenerative pathways that diminish p130 levels and yield conventional mitogenic signaling and the other being a genotoxic-induced pathway whereby RB controls the levels of E2F proteins to specifically yield cell cycle entry in RB-deficient models.13 For these analyses, we compared TCPOBOP and either DEN, a genotoxic carcinogen, or CCl4, which yields regeneration. TCPOBOP functioned similarly to CCl4 in leading to the attenuation of p130 status irrespective of RB status (Figure 3B). However, TCPOBOP had a relatively modest effect on E2F1 expression, and there was only effective induction of the MCM7 protein in RB-deficient liver tissue, similar to the PCNA expression data. These data indicate that TCPOBOP uses a signaling pathway more similar to regeneration to yield cell cycle entry but in an RB-dependent fashion. Consistent with this conclusion, TCPBOP-treated cells maintain appropriate ploidy (Figure 3C) and progress into mitosis (Figure 3D), which is indicative of regenerative signals as opposed to genotoxic stresses.

Figure 3.

Mice with RB-sufficient and RB-deficient livers were treated with TCPOBOP for 72 hours. A: Liver extracts were prepared and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins; all samples were analyzed in duplicate. B: Mice with RB-sufficient and RB-deficient livers were treated with TCPOBOP, DEN, or CCl4 and sacrificed at the indicated time points. Liver extracts were prepared and immunoblotted for the indicated proteins; all samples were analyzed in duplicate. C: Hepatocyte ploidy was measured by flow cytometry. D: Mitosis measured by phospho-histone H3 staining. Data are from four mice in each group and represent means ± SD (C and D).

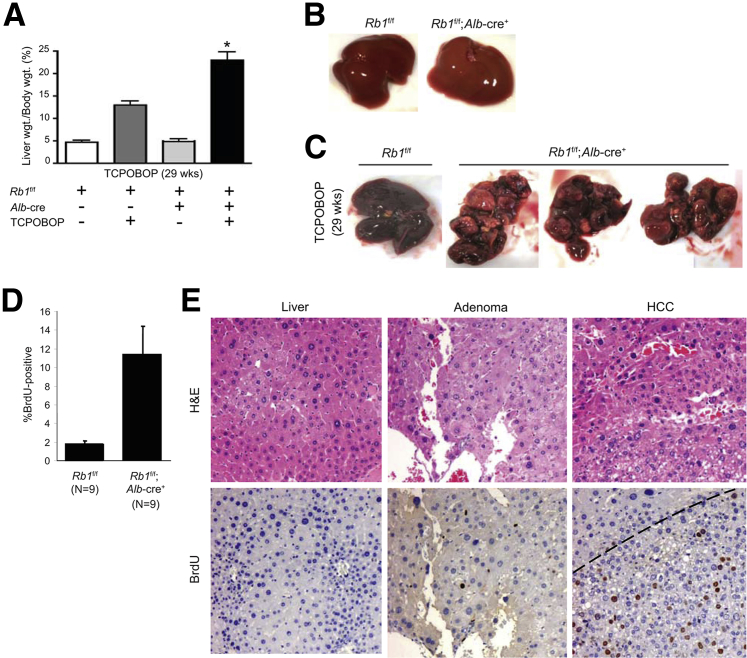

RB Loss Sensitizes to TCPOBOP-Mediated Tumor Development

To investigate whether RB functions as a tumor suppressor in response to long-term TCPOBOP exposure, mice were administered TCPOBOP on a biweekly basis for 24 weeks. Treated mice were not exposed to TCPOBOP for the next 5 weeks to allow for recovery and tumor progression. Before sacrifice, mice received a single injection of BrdU. After sacrifice, livers were excised, photographed, and weighed. As can be seen in Figure 4A, after treatment, both RB-sufficient and RB-deficient livers weighed significantly (P < 0.05) more than untreated control livers; however, this was especially evident in RB-deficient livers, where a twofold increase was seen when compared with RB-sufficient TCPOBOP-treated livers. Visual examination revealed that the increased liver weight was due to enhanced tumor burden (Figure 4, B and C). No tumors were visible in animals not treated with TCPOBOP, regardless of RB status.

Figure 4.

Mice were treated in the long-term with TCPOBOP and resultant livers excised after 29 weeks. A: Liver weight was determined for all mice. B: Representative images indicate that control tumors lack spontaneous tumors after 29 weeks regardless of RB status. C: Representative images indicate that RB-deficient livers exposed to TCPOBOP exhibit multiple large tumors on visual inspection. D: Quantitation of BrdU staining of liver lesions in RB-positive versus RB-negative tumors. E: Representative tissues were stained for H&E and BrdU incorporation. Dashed line represents approximate border between tumor and normal tissue. Data are presented as means ± SD (A and D). ∗P < 0.05 versus TCPOBOP-treated RB-sufficient livers as determined by Welch's t-test. Original magnification: ×20 (E).

Although the remnant liver tissue remained quiescent, as determined by BrdU incorporation (Figure 4D), all long-term TCPOBOP-treated livers exhibited dysplasia, with RB-deficient liver tissue exhibiting significant accumulation of hepatocytes with abnormally large nuclei (Figure 4E). In contrast, the adenomas and HCCs that arose in the RB-deficient livers were highly proliferative (Figure 4E). These data indicate a profound effect of RB loss on tumorigenesis driven by the nongenotoxic carcinogen TCPOBOP.

Discussion

RB loss occurs at a relatively high frequency in liver cancer. Because of the role of RB in cell cycle control, it has been expected that RB deficiency would have a general effect on the response to carcinogenic stresses. However, this study suggests specificity of RB function that would not have been heretofore expected.

Mice that harbor specific deletion in the liver have been found to develop tumors under the exposure of genotoxic carcinogens. However, RB loss in the presence of nongenotoxic carcinogens has, to our knowledge, never been explored. In the analysis of regenerative processes, we previously demonstrated no effect of RB loss on cell cycle control in terms of either cell cycle entry or exit.13 Similarly, we found no discernible effect of RB loss on the proliferative response to peroxisome proliferators or diets inducing steatosis (Figure 2). There are multiple explanations for these findings, but perhaps the most likely explanation is the myriad of overlapping cell cycle pathway regulators, including CDK inhibitors (eg, p27Kip1) and RB-related proteins (eg, p130), that maintain appropriate control of cellular proliferation in the absence of RB. Thus, the effect of RB loss is limited to specific responses and contexts.

Human HCC is particularly challenging to mimic in mouse models. In part, this is due to the absence of good models for hepatitis C virus– and hepatitis B virus–driven carcinogenesis.17–19 However, the key underlying feature of most HCCs is cirrhosis, which can be emulated through a variety of long-term exposures.1,17–19 The xenobiotic constitutive androstane receptor agonist agent TCPOBOP is similar in function to the tumor promoter phenobarbital.25 The underlying mechanism through which such agents promote tumor development is somewhat obscure, although clearly the repeated proliferative cycles induced by TCPOBOP serve to promote tumor development.26 In the absence of a genotoxic stress (eg, DEN), TCPOBOP is a relatively weak carcinogen, and as shown here only relatively low-grade adenomas arose in the RB-sufficient mice (Figure 4). Loss of RB strikingly synergizes with TCPOBOP in tumor development, yielding massive conversion to HCC in a large fraction of the liver tissue. On the basis of the acute response to TCPBOPOP, we would suspect that increased proliferative response in RB-deficient livers underlies this feature of disease. However, because quiescence readily develops after the cessation of TCPOBOP treatment, the genesis of HCC must reflect genetic and epigenetic alterations that drive HCC. In this fashion, this model mimics the pattern of long-term exposures in humans and suggests that the early loss of RB in a preneoplastic lesion would promote the acquisition of additional mutational events that facilitate the development of HCC. Because TCPOBOP of itself is not particularly genotoxic, these findings would suggest that RB loss can function as an initiator to drive the development of disease. This concept is borne out in clinical specimens, where tumors that lack RB (13q14 loss of heterozygosity) are associated with chromosome instability and poor overall outcome.27

These data reinforce the concept that RB loss has a specific effect on liver biology, leading to aberrant response to a subset of stresses. We found that RB controls the response to long-term exposure to nongenotoxic carcinogens that induce cirrhosis. In such contexts, RB serves as a potent tumor suppressor. Importantly, this transcends multiple carcinogenic stresses and supports the contention that RB deficiency is an important participant in the suppression of liver tumor development.

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute grant CA127387 (E.S.K.).

C.R. and J.H. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: C.R. is currently employed by PerkinElmer. All contributions to this study were performed before the onset of this relationship.

Current address of C.R., PerkinElmer, Downer's Grove, IL.

References

- 1.Farazi P.A., DePinho R.A. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badvie S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:4–11. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.891.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelotti G.A., Machado M.V., Diehl A.M. NAFLD, NASH and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:656–665. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGivern D.R., Lemon S.M. Tumor suppressors, chromosomal instability, and hepatitis C virus-associated liver cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:399–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bioulac-Sage P., Laurent-Puig P., Balabaud C., Zucman-Rossi J. Genetic alterations in hepatocellular adenomas. Hepatology. 2003;37:481. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian Y., Yang W., Song J., Wu Y., Ni B. Hepatitis B virus X protein-induced aberrant epigenetic modifications contributing to human hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2810–2816. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00205-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puszyk W.M., Trinh T.L., Chapple S.J., Liu C. Linking metabolism and epigenetic regulation in development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2013;93:983–990. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent-Puig P., Zucman-Rossi J. Genetics of hepatocellular tumors. Oncogene. 2006;25:3778–3786. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skawran B., Steinemann D., Becker T., Buurman R., Flik J., Wiese B., Flemming P., Kreipe H., Schlegelberger B., Wilkens L. Loss of 13q is associated with genes involved in cell cycle and proliferation in dedifferentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1479–1489. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X., Xu H.J., Murakami Y., Sachse R., Yashima K., Hirohashi S., Hu S.X., Benedict W.F., Sekiya T. Deletions of chromosome 13q, mutations in Retinoblastoma 1, and retinoblastoma protein state in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4177–4182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed C.A., Mayhew C.N., McClendon A.K., Yang X., Witkiewicz A., Knudsen E.S. RB has a critical role in mediating the in vivo checkpoint response, mitigating secondary DNA damage and suppressing liver tumorigenesis initiated by aflatoxin B1. Oncogene. 2009;28:4434–4443. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayhew C.N., Carter S.L., Fox S.R., Sexton C.R., Reed C.A., Srinivasan S.V., Liu X., Wikenheiser-Brokamp K., Boivin G.P., Lee J.S., Aronow B.J., Thorgeirsson S.S., Knudsen E.S. RB loss abrogates cell cycle control and genome integrity to promote liver tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:976–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed C.A., Mayhew C.N., McClendon A.K., Knudsen E.S. Unique impact of RB loss on hepatic proliferation: tumorigenic stresses uncover distinct pathways of cell cycle control. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1089–1096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park T.J., Kim H.S., Byun K.H., Jang J.J., Lee Y.S., Lim I.K. Sequential changes in hepatocarcinogenesis induced by diethylnitrosamine plus thioacetamide in Fischer 344 rats: induction of gankyrin expression in liver fibrosis, pRB degradation in cirrhosis, and methylation of p16(INK4A) exon 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2001;30:138–150. doi: 10.1002/mc.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saddic L.A., Wirt S., Vogel H., Felsher D.W., Sage J. Functional interactions between retinoblastoma and c-MYC in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClendon A.K., Dean J.L., Ertel A., Fu Z., Rivadeneira D.B., Reed C.A., Bourgo R.J., Witkiewicz A., Addya S., Mayhew C.N., Grimes H.L., Fortina P., Knudsen E.S. RB and p53 cooperate to prevent liver tumorigenesis in response to tissue damage. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1439–1450. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newell P., Villanueva A., Friedman S.L., Koike K., Llovet J.M. Experimental models of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2008;48:858–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakiri L., Wagner E.F. Mouse models for liver cancer. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:206–223. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y., Meyer C., Xu C., Weng H., Hellerbrand C., ten Dijke P., Dooley S. Animal models of chronic liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G449–G468. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00199.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragani T.A., Manenti G., Galliani G., Della Porta G. Promoting effects of 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene in mouse hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:225–228. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez F.J., Shah Y.M. PPARalpha: mechanism of species differences and hepatocarcinogenesis of peroxisome proliferators. Toxicology. 2008;246:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayhew C.N., Bosco E.E., Fox S.R., Okaya T., Tarapore P., Schwemberger S.J., Babcock G.F., Lentsch A.B., Fukasawa K., Knudsen E.S. Liver-specific pRB loss results in ectopic cell cycle entry and aberrant ploidy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4568–4577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koteish A., Mae Diehl A. Animal models of steatohepatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:679–690. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourgo R.J., Thangavel C., Ertel A., Bergseid J., McClendon A.K., Wilkens L., Witkiewicz A.K., Wang J.Y., Knudsen E.S. RB restricts DNA damage-initiated tumorigenesis through an LXCXE-dependent mechanism of transcriptional control. Mol Cell. 2011;43:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith G., Henderson C.J., Parker M.G., White R., Bars R.G., Wolf C.R. 1,4-Bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene, an extremely potent modulator of mouse hepatic cytochrome P-450 gene expression. Biochem J. 1993;289(Pt 3):807–813. doi: 10.1042/bj2890807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ledda-Columbano G.M., Pibiri M., Loi R., Perra A., Shinozuka H., Columbano A. Early increase in cyclin-D1 expression and accelerated entry of mouse hepatocytes into S phase after administration of the mitogen 1, 4-Bis[2-(3,5-Dichloropyridyloxy)] benzene. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:91–97. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64709-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishida N., Nishimura T., Ito T., Komeda T., Fukuda Y., Nakao K. Chromosomal instability and human hepatocarcinogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:897–909. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]