Abstract

This review will focus the roles of TNF-alpha, IL-1 alpha, and IL-1 beta in the mammalian testis and in two testicular pathologies, testicular torsion and orchitis. TNF alpha in the testis is produced by round spermatids, pachytene spermatocytes, and testicular macrophages. The type 1 TNF receptor has been found on Sertoli and Leydig cells and numerous studies suggest a paracrine mode of action for TNF alpha in the normal testis. IL-1 alpha has been reported to be produced by Sertoli cells, testicular macrophages, and possibly postmeiotic germ cells. IL-1 receptors have been reported on Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, testicular macrophages, and germ cells suggesting both autocrine and paracrine functions. While these proinflammatory cytokines have important roles in normal testicular homeostasis, an elevation of their expression can lead to testicular dysfunctions. Testicular torsion is a clinical pathology with results in testicular ischemia and surgical intervention is often required for reperfusion. A pivotal role for IL-1beta in the pathology of testicular torsion has been recently described whereby an increase in IL-1beta production after reperfusion of the testis is correlated with the activation of the stress-related kinase, c-jun N-terminal kinase, and ultimately resulting in neutrophil recruitment to the testis and germ cell apoptosis. In autoimmune orchitis, on the other hand, TNF alpha produced by T-lymphocytes and macrophages of the testis has been implicated in the development and progression of the disease. Thus, both proinflammatory cytokines, TNF alpha and IL-1, have significant roles in normal testicular functions as well as in certain testicular pathologies.

Introduction

The mammalian testis is an immunologically privileged site whereby tight junctions between Sertoli cells typically segregate germ cell autoantigens within the adluminal and luminal compartments of the seminiferous tubules [1]. Proinflammatory cytokines and other immune modulators must be tightly regulated in order to prevent inflammatory and immune responses in the testis. This review will focus on the localization and functional roles of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the mammalian testis and described two pathological conditions of the testis where a role for the proinflammatory cytokines has been determined.

TNFα is a multifunctional cytokine with effects not only in the proinflammatory response [2] but in immunoregulatory responses [3], and apoptosis [4]. TNFα is produced in numerous cell types and is initially synthesized as a transmembrane precursor that undergoes proteolytic cleavage from the cell surface to a soluble monomer of 17 kDa [5]. Soluble or secreted TNFα forms biologically active homotrimers; however, trimerization of TNFα may also occur with other members of the TNF protein family forming membrane-anchored heterotrimers that are also biologically active [6].

Two families of TNFα receptors (TNFR) have been highly characterized. The TNFR type 1 family includes TNFR1 (p55TNFR; CD120a), Fas (CD95), death receptor (DR)3, DR4, DR5, and DR6 [7]. The type 1 TNFRs are known for their ability to induce cell death via an amino acid motif in their cytoplasmic domains termed the death domain (DD) [7]. Upon ligand binding to the TNFR1 the intracellular adaptor protein TRADD (TNFR-associated death domain protein) is recruited to the DD of the receptor. TRADD can then recruit FADD (Fas-associated death domain protein) ultimately leading to the activation of caspases and cell death [7,8]. Alternatively, TRADD bound to TNFR1 can lead to the recruitment of cIAP (cellular inhibitor of apoptosis) or RIP (receptor interacting protein) enabling the binding of TRAF-2 (TNFR-associated factor-2). This complex formation does not result in apoptosis but rather leads to the activation of the NFκB pathway and/or the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or p38 [7]. Thus TNFR1 has dual signaling capabilities for either cell death or cell survival. Which pathway is selected appears to be a function of the adaptor proteins.

The TNFR type 2 family includes the TNFR2 (p75TNFR; CD120b), CD30, CD40, lymphotoxin receptor, RANK, and BAFF. The intracellular domains of these receptors do not contain DD but contain domains that associate with different TRAFs leading to the activation of cell signaling events [7,8].

The IL-1family of peptides consists of three gene products, IL-1α, IL-1β, and the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) [9]. Both IL-1α and IL-1β are secreted by macrophages and have been termed the 'alarm cytokines'. They are pleiotropic cytokines with many well characterized effects on immune responses [10,11]. Both IL-1α and IL-1β are known to cause inflammation and induce the expression of proinflammatory peptides such as inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase 2, IL-6, and TNFα [10]. In fact, IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNFα stimulate their own as well as each other's production in an amplification loop [10,11].

Both IL-1α and IL-1β are initially synthesized as precursors of 31 kDa that get proteolytically processed to their mature, 17 kDa forms [12]. IL-1α is processed by calpain while IL-1β is processed by IL-1β-converting enzyme also know as caspase-1 [12]. IL-1α and IL-1β differ from other cytokines in that they lack a signal sequence and cannot pass through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus. Their mechanism of secretion is not completely understood [13]. On the other hand, IL-1Ra does have a signal sequence and is secreted by the well characterized ER-Golgi pathway [14].

Two receptors have been described, IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1RI) and IL-1 type II receptor (IL-1RII), both receptors bind IL-1α and IL-1β and both receptors have reported to be expressed on many cell types. The IL-1RI is a signaling receptor. Following ligand binding to the receptor a protein termed IL-1R acceptor protein is recruited to the complex. This complex then triggers the activation of IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) which ultimately leads to gene activation [15]. On the other hand, IL-1RII is a non-signaling receptor that has been reported to be a decoy receptor [16]. Therefore, ligand binding to signaling IL-1 receptor, IL-1RI, may be regulated by the binding of ligand to IL-1RII or can be blocked by the binding of IL-1Ra to the IL-1RI. To add yet another level of complexity both receptors may be released from the cell surface and bind soluble ligand [17]. Both the IL-1 and TNFα signaling pathways can be stimulated under normal and pathological conditions in the testis.

Testicular torsion is characterized by a twisting of the spermatic cord that renders the testis ischemic. Surgical intervention is usually necessary for counter-rotation of the testis and reperfusion of the tissue [18]. In rodent models of testicular torsion there is an increase in neutrophils to the testis that is associated with oxidative stress and germ cell-specific apoptosis [19-21]. Recent data has demonstrated an increase in TNFα and IL-1β expression after reperfusion of the testis and that IL-1β may be responsible for stimulating a stress-related kinase signaling pathway leading to neutrophil recruitment from the testicular vasculature [22]. Another testicular pathology is autoimmune orchitis which occurs in several species. In humans several idiopathic diseases have been described that are similar to autoimmune orchitis, and these diseases are associated with male infertility [23]. In an animal model system termed experimental autoimmune orchitis (EAO) TNFα production by testicular T lymphocytes [24] and macrophages [25] has been linked to progression of the disease. Understanding the roles of proinflammatory cytokines in the testis and in testicular pathologies will aid in the development of therapies to rescue the testis from the adverse effects of inflammation and will give insights into male infertility.

Role of TNFα in the normal testis

Localization of TNFα and TNFα receptors in the testis

By enriching for specific germ cell populations using unit gravity sedimentation and analyzing for the secretion of bioactive TNFα and for TNFα mRNA De et al [26] have shown that round spermatids secreted TNFα and both pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids contained TNFα mRNA, though at two different transcript sizes [26]. Results from in situ hybridization studies confirmed the presence of TNFα mRNA in the round spermatids and pachytene spermatocytes and detected mRNA in testicular interstitial macrophages as well [26].

Interstitial testicular macrophages have also been described a possible a source of TNFα. Early studies by Hutson [27] on collagenased dispersed rat testicular macrophages found TNFα activity in the conditioned media. However, later studies from the same investigators, found that no TNFα was detected in testicular interstitial fluid or in testicular macrophages isolated without collagenase [28] suggesting that TNFα is not constitutively expressed in the normal testis. Treatment of non-collagenase isolated rat testicular macrophages with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) did induce TNFα secretion indicating that TNFα may be produced by testicular macrophages under certain conditions [28].

To determine which cell type TNFα may be acting upon De et al [26] performed Northern blot analysis for TNFR1 in isolated cell populations and found that Sertoli and Leydig cells contained the mRNA for TNFR1. Using cultured porcine Sertoli cells Mauduit and coworkers [29] demonstrated that Sertoli cells bound radiolabeled TNFα via TNFR1 and that treatment with follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) upregulated TNFR1. TNFR2 or the p75 TNF receptor was not detected [29].

Taken together results of the above studies suggest that TNFα is normally produced by germ cells, notably round spermatids, and that the receptors are on Sertoli and Leydig cells.

Role of TNFα in the seminiferous epithelium

Numerous functional roles for TNFα in the mammalian have been described by a number of laboratories. In germ cells TNFα has been reported to increase the expression of cytochrome P450 aromatase, an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of estrogen from androgens [30]. The TNFα-mediated increase in cytochrome P450 aromatase was found to be predominantly in pachytene spermatocytes, while an inhibitory effect was observed in round spermatids [30].

TNFα also acts in indirect ways to support spermatogenesis. As stated earlier, TNFα can stimulate the activation of the transcription factor NFκB and, indeed in, cultures of rat Sertoli cells TNFα stimulated nuclear NFκB binding [31]. The intracellular androgen receptor (AR) in Sertoli cells binds and mediates testosterone signaling. Studies by Delfino et al [32] found that TNFα stimulated binding of NFκB to the AR promoter and increased endogenous AR in primary cultures of Sertoli cells.

TNFα has also been shown to suppress Mullerian inhibiting substance (MIS). MIS is essential for normal sex differentiation and its expression is strictly regulated. Expression of MIS in Sertoli cells is high in the fetal to prepubertal period but then decreases after puberty. Studies by Hong et al [33] have shown that TNFα is the molecule responsible for suppression of MIS. Treatment of testis organ cultures with TNFα caused a decrease in MIS expression and testis from TNFα knockout mice showed high and prolonged MIS expression. The suppressive ability of TNFα on MIS was found to be due to the activation of NFκB which subsequently associated with and repressed the transcription factor SF-1 [33].

Transferrin is a major transporter of iron into cells [34]. In the testis where the blood-testis barrier prevents macromolecules and several electrolytes from entering the adluminal compartment iron is transported into the compartment from the circulatory system by transferrin produced in Sertoli cells [35]. Early studies showed that transferrin production is regulated by germ cells [36]. More recently, TNFα was found to increase transferrin mRNA and protein levels in Sertoli cells in vitro [37]. The effect of TNFα on Sertoli cell transferrin production was also found to be dependent on the stage of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium with Sertoli cells from stages IX-XI and XIII most clearly responding [38]. These results together with those indicating that TNFα is secreted by germ cells [26] suggest that TNFα produced by germ cells acts in a paracrine manner to upregulate transferrin production by Sertoli cells and thus maintain spermatogenesis.

TNFα has also been shown to stimulate lactate dehydrogenase A expression in Sertoli cells [39]. Postmeiotic germ cells utilize lactate derived from Sertoli cells rather than glucose as an energy substrate [40]. Lactate dehydrogenase A is a key enzyme involved in lactate production. Treatment of Sertoli cells with TNFα caused a dose-dependent increase in lactate dehydrogenase A mRNA expression [39]. In other studies it was also found that TNFα increased the activity of lactate dehydrogenase in cultured Sertoli cells [41]. These results again suggest an important paracrine mode of action for TNFα on maintaining spermatogenesis. Monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) are responsible for the transportation of lactate across the plasma membrane and recent studies have demonstrated the presence of MCT2 in differentiated murine germ cells and suggest it may play a role in lactate uptake [42]. Interestingly, TNFα was found to inhibit MCT2 expression. These results led Boussouar et al [42] to hypothesize that the inhibitory effect of TNFα on MCT2 in germ cells was related to the stimulatory effect of TNFα on Sertoli cell lactate production and would prevent an over accumulation of lactate in the germ cells.

Studies by Pentikainen et al [43] have found that TNFα inhibited in a concentration dependent manner the germ cell apoptosis observed in segments of human seminiferous epithelium cultured under serum-free conditions. TNFα down-regulated Fas ligand (FasL) production by segments of seminiferous epithelium; thus, Pentikainen et al [43] suggested that TNFα produced by germ cells works in a paracrine fashion to down-regulate FasL production by Sertoli cells and promote germ cell survival. TNFα has also been reported to increase both membrane-bound and soluble forms of Fas in cultured Sertoli cells [44]. Sertoli cells treated with low concentrations of TNFα secreted the soluble form of Fas that was capable of inhibiting a basal level of apoptosis. At higher concentrations of TNFα, however, upregulation of membrane bound Fas was predominant and the germ cells were susceptible to FasL-mediated apoptosis. These results suggest that under physiologically low concentrations of TNFα the soluble form of Fas is produced by Sertoli cells and acts as a survival factor for germ cells; whereas, at high concentrations TNFα such as during inflammation TNFα induces membrane bound Fas which primes the Sertoli cells for FasL induced cell death [44].

Another way in which TNFα exerts a paracrine effect on Sertoli cells is through the stimulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) [45]. By increasing IGFBP-3 levels in treated Sertoli cells TNFα was able to antagonize the action of IGF-1 on FSH binding to Sertoli cells [45]. TNFα was able to increase IL-1α and IL-6 production from cultures of rat Sertoli cells [46]. These data suggest that TNFα can alter the cytokine secretion profile of Sertoli cells that may affect Sertoli cell functions and ultimately spermatogenesis.

Studies investigating the signal transduction pathways stimulated by TNFα in Sertoli cells have found that treatment of murine Sertoli cells with TNFα resulted in the activation of JNK as well as p38 MAPK [47]. By employing a specific p38 inhibitor it was demonstrated that activation of the p38 MAPK pathway led to the production of IL-6 by TNFα stimulated Sertoli cells and activation of the JNK pathway increased surface expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) [47]. Since TNFα plays a role in increasing cell adhesion molecules, De Cesaris et al [47] suggested that the effect of TNFα on Sertoli cells may be pathogenic in the outbreak of autoimmune disorders in the testis.

TNFα has also been shown to effect Sertoli cell tight junction assembly, collagen α 3(IV) synthesis, and enzymes and their inhibitors that effect the extracellular matrix (ECM) [48]. By increasing the expression of matrix metalloprotease-9, TNFα has been found to perturb Sertoli cell tight junction formation; however, TNFα also increased the inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 and collagen α 3(IV) production suggesting a feedback mechanism to replenish the collagen network and reform tight junctions [48]. These results have led Siu et al [48] to suggest that TNFα influences the dynamics of the Sertoli cell tight junctions through effects on the ECM.

Glutathione S-transferase-α (GSTα) is an enzyme expressed by Sertoli cells involved primarily in detoxification. TNFα was found to decrease basal as well as hormone-stimulated GSTα in cultures Sertoli cells [49]. Benbrahim-Tallaa et al [49] suggested that increased levels of TNFα in the testis may alter the detoxification processes against genotoxic products during spermatogenesis.

TNFα in combination with other cytokines and lipopolysaccharides has been shown to stimulate inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and nitrite in Sertoli cells as well as seminiferous pertitubular cells [50]. Similarly treating Sertoli cells with a combination of cytokines that included TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 caused a more than additive effect on transferrin and cGMP secrection [51].

Based on the above studies TNFα has numerous roles in normal testicular functions (Table 1). At least one study suggests that the levels of TNFα produced in the testis may be an important factor. Low levels of TNFα may preferentially regulate normal testicular homeostasis; whereas, elevated levels influence or initiate pathological conditions in the testis.

Table 1.

Summary of the Effects of TNFα on Sertoli, Leydig, and Peritubular Cells

| Sertoli Cells | Leydig Cells | Peritubular Myoid Cells |

| increase cytochrome | decrease testosterone [52-56] | increase PAI-1 [57] |

| P450 aromatase [30] | ||

| increase NFκB activity [31] | ||

| increase AR [32] | ||

| decrease MIS [33] | ||

| increase transferrrin [37,38] | ||

| increase LDH-A [39,41] | ||

| decrease MCT2 [42] | ||

| decrease FasL [43] | ||

| increase Fas [44] | ||

| increase IGFBP-3 [45] | ||

| increase IL-6 [46,47] | ||

| increase ICAM and VCAM [47] | ||

| increase MMP9 [48] | ||

| increase TIMP-1 and collagen [48] | ||

| decrease GST [49] |

Role of TNFα in testicular interstitial cells

Since testicular macrophages may be a source of TNFα and since testicular macrophages and Leydig cells are intimately associated through membrane digitations a role for TNFα in Leydig cell steroidogenesis has been investigated. Treatment of isolated murine Leydig cells with TNFα resulted in a significant decrease in basal testosterone secretion as well as cAMP-stimulated testosterone production [52]. This TNFα inhibitory affect on the cAMP-stimulated testosterone production in Leydig cells was found to be due to a decrease in mRNA and protein levels of two cytochrome P450 enzymes important in testosterone biosynthesis, cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme and 17α-hydroxylase/C17–20 lyase [52]. Furthermore, Li et al [53] have demonstrated that the inhibitory affect of TNFα on 17α-hydroxylase/C17–20 lyase gene expression is mediated via protein kinase C. The inhibitory affect of TNFα on LH/hCG-induced testosterone secretion has also been reported in porcine Leydig cells [54]. In these studies the mechanism of the inhibitory affect of TNFα was reported to be due to a decrease in steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mRNA and protein levels [54]. Results from two independent studies have also shown that the TNFα inhibitory affects on Leydig cell testosterone secretion may involve a sphingomyelin/ceramide-dependent pathway [55,56]. Thus, results from numerous laboratories employing mouse, rat, or porcine Leydig cells have reported an inhibitory affect of TNFα on testosterone production; however, it remains unclear whether Leydig cells are normally exposed to TNFα under normal testicular homeostasis or only after testicular macrophages are activated.

Besides having an affect on Leydig cell testosterone production TNFα has also been reported to increase plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) expression in rat testicular peritubular cells indicating that it may be involved in controlling protease activity [57]. The authors suggest, however, that the biological effects of TNFα on PAI-1 may be secondary to due to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling since TNFα also increased EGFR mRNA and EGF binding in the peritubular cells [57]. Table 1 summarizes the key roles of TNFα in the mammalian testis.

Role of IL-1 in the normal testis

Localization of IL-1 and IL-1 receptors in the testis

It appears that some controversy exists on the exact cell type in the mammalian testis that produces IL-1; however, the procedures used and the age of the animals may account for some of these differences. Early studies in the rat identified an IL-1-like factor in the testis that first appears during puberty, is stage dependent, and is correlated with spermatogonial DNA synthesis [58]. Results of autoradiographic studies on membrane preparations from the mouse testis revealed that IL-1α displayed significantly higher binding then IL-1β and the highest binding density was observed in the interstitial areas of the testis [59]. By employing RT-PCR and in situ hybridization techniques Jonsson et al [60] have demonstrated that the IL-1-like protein is IL-1α and not IL-1β or IL-6. Extracts of seminiferous tubule segments also demonstrated the presence of bioactive IL-1 but not IL-6. Results of the in situ hybridization studies revealed the IL-1α mRNA was localized to Sertoli cells in animals greater than 20 days of age. In younger rats no IL-1α transcripts were detected in the testis. The IL-1α mRNA was present in Sertoli cells at all stages of the seminiferous epithelium except stage VII which was negative [60]. Interestingly the presence of IL-1α in Sertoli cells is dependent upon the presence of germ cells. In animals depleted of germ cells either by exposure to radiation prenatally or by treating adults with busulfan no IL-1α mRNA was detected in Sertoli cells [60]. Studies by Cudicini et al [61] have demonstrated the presence of IL-1α in human Sertoli cells but also demonstrated the presence of IL-1α and IL-1β in isolated Leydig cells. Rozwadowska et al [62] also demonstrated IL-1α mRNA expression in seminiferous tubules and IL-1β mRNA expression in the interstitium of human testis. Further, Hales et al [63] demonstrated the presence of IL-1 mRNA in testicular macrophages. In contrast, Haugen et al [64] reported the presence of IL-1α protein and mRNA in isolated postmeiotic germ cells.

To further complicate matters regarding IL-1 in the testis, Gustafsson et al [65] reported that three isoforms of IL-1α are produced in the testis that may be posttranslational modifications of the IL-1α precursor and their differential effects are unknown. Also the IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-1Ra, has been reported to be constitutively produced by isolated mouse Sertoli cells, but since the molecule was found intracellularly and no IL-1Ra bioactivity could be detected in the conditioned media [66] an inhibitory role may be unlikely.

Both IL-1Rs have been reported in the testes of mouse, rat, and human. IL-1RI and IL-1RII mRNA were observed in Sertoli, Leydig, and testicular macrophages from all three species whereas, only the rodent germ cells expressed IL-1RI and IL-1RII mRNA [67].

Role of IL-1 in the seminiferous epithelium

IL-1α has been reported to be a potent growth factor for immature Sertoli cells. Recent studies by Petersen et al [68] have not only identified the IL-1RI in cultures of Sertoli cells from 8 to 9 day rats but also demonstrate that IL-1α enhances Sertoli cell proliferation. Treatment of Sertoli cells with a combination of IL-1α and FSH showed a synergistic affect on proliferation [68]. These results suggest that IL-1α may serve as a growth factor for Sertoli cells (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the Effects of IL-1 α and IL-1β on Sertoli and Leydig Cells

Role of IL-1 in testicular interstitial cells

The intimate association of Leydig cells and interstitial macrophages has prompted several studies investigating possible immuno-endocrine interactions. Numerous early studies have reported that IL-1 inhibits basal and LH/hCG-stimulated testosterone production by Leydig cells [69-71]. However, other studies have shown that IL-1β can stimulate testosterone levels in Leydig cells [72,73]. The apparent discrepancies in the results may come from differences in the experimental conditions or methodologies. In cultures of isolated rat Leydig cells from animals 10 to 20 days old IL-1β caused a dose-dependent increase in the incorporation of 3H-thymidine into DNA [74]. IL-1α also had an affect on 3H-thymidine incorporation; however, it was much less potent than IL-1β. The effect of IL-1β was not observed in Leydig cell isolated from older animals suggesting that IL-1β may play a role in the proliferation of Leydig cells during prepubertal development [74].

Mice that lack a functional IL-1 signaling receptor (IL-1RI) exhibit normal fertility, have normal serum testosterone, and normal testicular levels of steroidogenic enzymes suggesting that IL-1 receptor signaling is not required in Leydig cell steroidogenesis [75]. However, in studies where intratesticular macrophages have been depleted either via the injection of silica or by genetic mutation the development of normally functioning Leydig cells is impaired [76]. These observations lead Hales [69] to suggest that during testicular development and under non-inflammatory conditions interstitial macrophages provide the appropriate microenvironment to support Leydig cells. Table 2 summarizes the key functional roles of IL-1α and IL-1β in the mammalian testis.

Proinflammatory cytokines in testicular pathology

Testicular torsion

Recent studies from our laboratory have reported an increase in the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β after ischemia/reperfusion (IR) of the testis and suggest a role for the proinflammatory cytokines as early mediators of IR-injury in the testis [22]. In the human, ischemia of the testis can result during a medical condition known as testicular torsion in which there is twisting of the spermatic cord. It is a medical emergency and surgical intervention is usually required for reperfusion of the testis; however, even after reperfusion testicular atrophy is common. Early studies from our laboratory have shown that IR of the rat testis results in a permanent loss of spermatogenesis despite the return of blood flow [77] and the continued presence of functional Leydig [78] and Sertoli cells [79]. The IR-induced loss of spermatogenesis has been shown to be the result of germ cell-specific apoptosis [20,21,80]. Occurring contemporaneously with the IR-induced germ cell-specific apoptosis is an increase in neutrophils [20,21] and reactive oxygen species [19] in the testis. Germ cell-specific apoptosis after IR of the testis is dependent upon the recruitment of neutrophils to the testis [5], and we have recently reported that an increase in proinflammatory cytokines after IR of the testis is correlated with activation of signaling pathways leading to neutrophil recruitment [22].

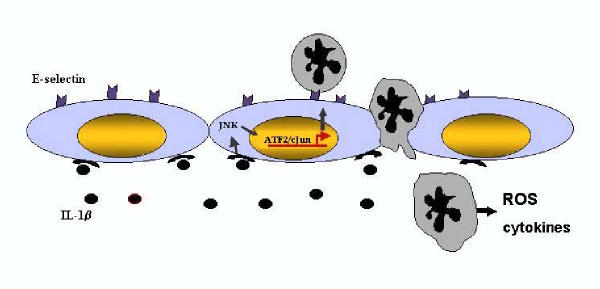

As early as 0.5 hr after IR of the murine testis an increase in the expression of both TNFα and IL-1β is observed [22] and this precedes the activation of JNK. JNK is a stress-related kinase that plays a critical role in the cellular response to many types of cellular stress. Two transcription factors downstream of JNK, ATF-2 and c-jun, are also activated, and immunolocalization of activated, phosphorylated, JNK (phospho-JNK) demonstrated immunoreactivity in intratesticular blood vessels [22]. Corresponding with this was an increase in E-selectin mRNA and protein 4 hr after IR of the testis [22]. Indeed, the E-selectin promoter is known to contain a positive regulatory domain II site which has been shown to bind a heterodimer of ATF-2 and c-jun [81]. E-selectin is an endothelial cell adhesion molecule responsible for the tethering and slow rolling of neutrophils to endothelial cells [82]. These results suggest that an increase in TNFα and/or IL-1β after IR of the testis stimulates the activation JNK signaling pathway leading to the expression of E-selectin in endothelial cells and ultimately neutrophil recruitment (Figure 1). In order to determine if TNFα, IL-1β, or both proinflammatory cytokines were eliciting this response, the cytokines were injected either alone or in combination to the testis and phosphorylation of JNK and neutrophil recruitment was examined. Results from these experiments revealed that injection of IL-1β mimicked the effects of IR on the testis, causing an activation of JNK and a recruitment of neutrophils to the testis [22]. Thus, an increase in IL-1β after IR of the testis stimulates an intracellular signaling cascade in testicular endothelial cells resulting in neutrophil recruitment and eventually germ cell death. The cell type responsible for the increase in IL-1β production after IR of the testis is currently unknown. Even though TNFα did not have a role in neutrophil recruitment or JNK activation in the testis, preliminary experiments in our lab suggest that the increase in TNFα may lead to the activation of NFκB in Sertoli cells (Lysiak and Turner, unpublished) and may influence germ cell apoptosis by increasing FasL expression in Sertoli cells. Identification of the mechanisms involved in germ cell-specific apoptosis after IR may lead to the development of therapies aimed at interrupting specific pathways in order to prevent the IR-induced loss of spermatogenesis.

Figure 1.

Following ischemia/reperfusion of the testis IL-1β expression is increased. Corresponding with the increase in IL-1β is an activation of JNK localized to endothelial cells in the testis. Two downstream transcription factors of JNK, ATF-2 and c-jun are also activated and are known to form a heterodimer and upregulate E-selectin expression. E-selectin expressed on the surface of endothelial cells aids in the recruitment of neutrophils to the testis. Once neutrophils are bound to endothelial cells they can transmigrate through the endothelial cells into the interstitium where they are poised to release factors such as reactive oxygen species or other cytokines. The source of IL-1β production after ischemia/reperfusion of the testis is currently unkown; however, Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and interstitial macrophages are candidates.

Autoimmune orchitis

Autoimmune orchitis can occur spontaneously in dogs [83] and mink [84] and after vasectomy in rabbits [85] and guinea pigs [86]. Mice that have been thymectomized within 4 days of birth also develop a similar autoimmune orichitis [87]. In humans several idiopathic diseases of the testis have been described that are similar to autoimmune orchitis and are associated with male infertility [23]. Animals injected with homologous testis antigen also develop autoimmune orchitis [88]. This animal model system is known as experimental autoimmune orchitis (EAO) and is widely used to study this disease.

A role for proinflammatory cytokines in EAO has been described by Yule and Tung [24], who demonstrated that injection of a TNF neutralizing antibody abrogated the effects of EAO. By generating T-lymphocyte clones from mice with EAO and injecting them into normal mice Yule and Tung [24] demonstrated the T-lymphocyte clones induced the testicular autoimmune disease. The T-lymphocytes responsible for the transfer of EAO were found to be of the CD4+ subset and have a cytokine secretion profile of TNFα, IL-2, and IFNγ. To determine if TNFα had a role in the development of EAO orchitogenic T-lymphocytes were injected into recipient mice along with an anti-TNFα neutralizing antibody. Results from these experiments demonstrated that when TNFα was neutralized in vivo, orchitis elicited by an orchitogenic T-lymphocyte clone was significantly attenuated suggesting an important role for TNFα in EAO [24].

Recent studies by Suescun et al [25] provide further evidence for the involvement of TNFα in EAO. Rats with EAO exhibited a significant increase in the number of TNFα-positive testicular macrophages. Testicular macrophages isolated from animals with EAO and cultured secreted increased amounts of TNFα in the media compared to macrophage isolated from control animals [25]. An increase in the number of TNFR1 positive germ cells during EAO was also noted suggesting a possible role for TNFα in germ cell apoptosis during EAO. Suescun et al [25] postulate that TNFα is probably involved in the progression of EAO because of its ability to increase endothelial cell permeability, to facilitate monocyte extravasation in the testis, and to activate T cells and macrophages through both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. In biopsies of human testicular pathologies involving inflammation an increase in the number of macrophages and in TNFα expression by testicular macrophages has also been observed adding further evidence for the involvement of TNFα in testicular inflammation [89].

Conclusions

TNFα and IL-1 are produced in the testis under normal physiological conditions and play an important role in maintaining testicular function. Certain pathologic conditions, for example testicular torsion and autoimmune orchitis, however cause an increase in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines. This increase in expression shifts the balance in favor of inflammatory and immune responses. Once immune cells are either recruited to the testis (neutrophils, lymphocytes) or activated in the testis (macrophages) germ cell apoptosis is observed and spermatogenesis is disrupted. By identifying the cells upon which the proinflammatory cytokines react and by identifying intracellular signaling cascades activated during pathologic conditions of the testis targets for specific therapies may be uncovered that will aid in maintaining testicular function.

References

- Head JR, Neaves WB, Billingham RE. Immune privilege in the testis. I. Basic parameters of allograft survival. Transplantation. 1983;36:423–429. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198310000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers W. Tumor necrosis factor. Characterization at the molecular, cellular and in vivo level. FEBS Lett. 1991;285:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80803-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B. TNF, immunity and inflammatory disease: lessons of the past decade. J Investig Med. 1995;43:227–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SJ, Reddy EP. Modulation of life and death by the TNF receptor superfamily. Oncogene. 1998;17:3261–3270. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cseh K, Beutler B. Alternative cleavage of the cachetin/tumor necrosis factor propeptide results in a larger inactive form of secreted protein. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16256–16260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlgans T, Mannel DN. The TNF-TNF Receptor System. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1581–1585. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak TW, Yeh WC. Signaling for survival and apoptosis in the immune system. Arthitis Res. 2002;4:S243–S252. doi: 10.1186/ar569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg SP, Brewer MT, Verderber E, Heimdal P, Brandhuber BJ, Thompson RC. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist is a member of the interleukin 1 gene family: evolution of a cytokine control mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:5232–5236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Biological basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stylianou E, Saklatvala J. Interleukin-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;30:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte RN, Voronov E. Interleukin-1 – a major pleiotropic cytokine in tumor-host interactions. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2002;12:277–290. doi: 10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubartelli A, Cozzolino F, Talio M, Sitia R. A novel secretory pathway for interleukin-1 beta, a protein lacking a signal sequence. EMBO J. 1990;9:1503–1510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend W. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:167–226. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S, Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell. 2003;11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auron PE. The interleukin 1 receptor: ligand interactions and signal transduction. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:221–237. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(98)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MU, Falk W. The interleukin-1 receptor complex and interleukin-1 signal transduction. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1997;8:5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson RNC. The continuing conundrum of testicular torsion. Br J Surg. 1985;72:509–510. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysiak JJ, Nguyen QAT, Turner TT. Peptide and nonpeptide reactive oxygen scavengers provide partial rescue of the testis after torsion. J Androl. 2002;23:400–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TT, Tung KSK, Tomomasa H, Wilson LW. Acute testicular ischemia results in germ cell-specific apoptosis in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1267–1274. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysiak JJ, Turner SD, Nguyen QAT, Singbartl K, Ley K, Turner TT. Essential role of neutrophils in germ cell-specifc apoptosis following ischemia/reperfusion injury of the mouse testis. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:718–725. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.3.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysiak JJ, Nguyen QAT, Kirby JL, Turner TT. Ischemia-reperfusion of the murine testis stimulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase in a pathway to E-selectin expression. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:202–210. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung KSK, Lu CY. Immunologic basis of reproductive failure. In: Kraus FT, Damjanov I, and Kaufman N, editor. In Pathology of Reprouction Failure. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1989. pp. 308–333. [Google Scholar]

- Yule TD, Tung KSK. Experimental autoimmune orchitis induced by testis and sperm antigen-specific T cell clones: An important pathogenic cytokine is tumor necrosis factor. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1098–1107. doi: 10.1210/en.133.3.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suescun MO, Rival C, Theas MS, Calandra RS, Lustig L. Involvment of tumor necrosis factor-α in the pathogenesis of autoimmune orchitis in rats. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:2114–2121. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.011189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SK, Chen HL, Pace JL, Hunt JS, Terranova PF, Enders GC. Expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in mouse spermatogenic cells. Endocrinology. 1993;133:389–396. doi: 10.1210/en.133.1.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson JC. Secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha by testicular macrophages. Reprod Immunol. 1993;23:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(93)90027-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, Hutson JC. Physiological relevance of tumor necrosis factor in mediating macrophage-Leydig cell interactions. Endocrinology. 1994;134:63–69. doi: 10.1210/en.134.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauduit C, Besset V, Caussanel V, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor α receptor p55 is under hormonal (follicle-stimulating hormone) control in testicular Sertoli cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;224:631–637. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguiba S, Chater S, Delalande C, Benahmed M, Carreau S. Regulation of aromatase gene expression in purified germ cells of adult male rats: Effects of transforming growth factor β, tumor necrosis factor α, and cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monosphosphate. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:592–601. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino F, Walker WH. Stage-specific nuclear expression of NF-κB in mammalian testis. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1696–1707. doi: 10.1210/me.12.11.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delfino FJ, Boustead JN, Fix C, Walker WH. NF-κB and TNF-α stimulate androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;201:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(03)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CY, Park JH, Seo KH, Kim JM, Im SY, Lee JW, Choi HS, Lee K. Expression of MIS in the testis is downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha through the negative regulation of SF-1 transactivation by NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6000–6012. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6000-6012.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen P, Listowsky I. Iron transport and storage proteins. Annul Rev Biochem. 1980;49:357–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester SR, Griswold MD. The testicular iron shuttle: a nurse function of the Sertoli cells. J Androl. 1994;15:381–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallard BJ, Griswold MD. Germ cell regulation of Sertoli cell transferrin mRNA levels. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:393–401. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-3-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigillo F, Guillou F, Fontaine I, Benahmed M, Le Magueresse-Battistoni B. In vitro regulation of rat Sertoli cell transferrin expression by tumor necrosis factor α and retinoic acid. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;148:163–170. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(98)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boockfor FR, Schwarz LK. Effects of interleukin-6, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor alpha on transferrin release from Sertoli cells in culture. Endocrinology. 1991;129:256–262. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-1-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussouar F, Grataroli R, Ji J, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor-α stimulates lactate dehydrogenase A expression in porcine cultured Sertoli cells: Mechanisms of action. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3054–3062. doi: 10.1210/en.140.7.3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootegoed JA, Den Boer P. Energy metabolism of spermatids: a review. In: Hamilton DW, Waites GMH, editor. In Cellular and Molecular Events in Spermiogenesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Nehar D, Mauduit C, Boussouar F, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated lactate production is linked to lactate dehydrogenase A expression and activity increase in porcine cultured Sertoli cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1964–1971. doi: 10.1210/en.138.5.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussouar F, Mauduit C, Tabone E, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Benahmed M. Developmental and hormonal regulation of the monocarboxylate transporter 2 (MCT2) expression in the mouse germ cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1069–1078. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.010074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentikainen V, Erkkila K, Suomalainen L, Otala M, Pentikainen MO, Parvinen M, Dunkel L. TNFα down-regulates the Fas ligand and inhibits germ cell apoptosis in the human testis. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2001;86:4480–4488. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.9.4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccioli A, Starace D, D'Alesssio A, Starace G, Padula F, De Cesaris P, Filippini A, Ziparo E. TNF-α and IFN-γ regulate expression and function of the Fas system in the seminiferous epithelium. J Immunol. 2000;165:743–749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besset V, Le Magueresse-Battistoni B, Collette J, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 expression in cultured porcine Sertoli cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:296–303. doi: 10.1210/en.137.1.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan JP, Syed V, Jegou B. Regulation of Sertoli cell IL-1 and IL-6 production in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;134:109–118. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(97)00172-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cesaris P, Starace D, Riccioli A, Padula F, Filippini A, Ziparo E. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces interleukin-6 production and integrin ligand expression by distinct transduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7566–7571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu MKY, Lee WM, Cheng CY. The interplay of collagen IV, tumor necrosis factor-α, gelatinase B (matrix metalloprotease-9), and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 in the basal lamina regulates cell-tight junction dynamics in the rat testis. Endocrinology. 2003;144:371–387. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Boussouar F, Rey C, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibits glutathione S-transferase-α expression in cultured porcine Sertoli cells. J Endocrinol. 2002;175:803–812. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauche F, Stephan JP, Touzalin AM, Jegou B. In vitro regulation of an inducible-type NO synthase in the rat seminiferous tubule cells. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:431–438. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeben E, Wuyts A, Proost P, Damme JV, Verhoeven G. Identification of IL-6 as one of the important cytokines responsible for the ability of mononuclear cells to stimulate Sertoli cell functions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;132:149–160. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(97)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Hales DB. The role of tumor necrosis factor-α in the regulation of mouse Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2438–2444. doi: 10.1210/en.132.6.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Youngblood GL, Payne AH, Hales DB. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibition of 17α-hydroxylase/c17-20 lyase gene (Cyp17) expression. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3519–3526. doi: 10.1210/en.136.8.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauduit C, Gasnier F, Rey C, Chauvin MA, Stocco DM, Louisot P, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibits Leydig cell steroidogenesis through a decrease in steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2863–2868. doi: 10.1210/en.139.6.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budnik LT, Jahner D, Mukhopadhyay AK. Inhibitory effects of TNFα on mouse tumor Leydig cells: possible role of ceramide in the mechanism of action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;150:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meroni SB, Pellizzari EH, Canepa DF, Cigorraga SB. Possible involvement of ceramide in the regulation of rat Leydig cell function. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;75:307–313. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Magueresse-Battistoni B, Pernod G, Kolodie L, Morera AM, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor-α regulates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in rat testicular peritubular cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1097–1105. doi: 10.1210/en.138.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soder O, Syed V, Callard GV, Toppari J, Pollanen P, Parvinen M, Froysa B, Ritzen EM. Production and secretion of an interleukin-1-like factor is stage dependent and correlates with spermatogonial DNA synthesis in the rat seminiferous epithelium. Int J Androl. 1991;14:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1991.tb01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao T, Mitchell WM, Tracey DE, De Souza. Identification of interleukin-1 receptors in mouse testis. Endocrinology. 1990;127:251–258. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-1-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson CK, Zetterstrom RH, Holst M, Parvinen M, Soder O. Constitutive expression of interleukin-1α messenger ribonucleic acid in rat Sertoli cells is dependent upon interaction with germ cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3755–3761. doi: 10.1210/en.140.8.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudicini C, Lejeune H, Gomez E, Bosmans E, Ballet F, Saez J, Jegou B. Human Leydig cells and Sertoli cells are producers of interleukins-1 and -6. J Clinic Endocrinol Metabol. 1997;82:1426–1433. doi: 10.1210/jc.82.5.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozwadowska N, Fiszer D, Kurpisz M. Interleukin-1 system in testis – quantitative analysis: Expression of immunomodulatory genes in male gonad. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2001;495:177–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales DB. Testicular macrophage modulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;57:3–18. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen TB, Landmark BF, Josefen GM, Hansson V, Hogset A. The mature form of interleukin-1α is constitutively expressed in immature male germ cells from rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;105:R19–R23. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson K, Sultana T, Zetterstrom CK, Setchell BP, Siddiqui A, Weber G, Soder O. Production and secretion of interleukin-1α proteins by rat testis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:492–497. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeyse D, Lunenfeld E, Beck M, Prinsloo I, Huleihel M. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is produced by Sertoli cells in vitro. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1521–1527. doi: 10.1210/en.141.4.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez E, Morel G, Cavalier A, Lienard MO, Haour F, Courtens JL, Jegou B. Type I and type II interleukin-1 receptor expression in rat, mouse, and human testes. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:1513–1526. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.6.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Boitani C, Froysa B, Soder O. Interleukin-1 is a potent growth factor for immature rat Sertoli cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;186:37–47. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales DB. Interleukin-1 inhibits Leydig cell steroidogenesis primarily by decreasing 17α-hydroxylase/C17-20 lyase cytochrome P450 expression. Endocrinology. 1992;131:2165–2172. doi: 10.1210/en.131.5.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T, Wang D, Nagpal ML, Calkins JH, Chang WC, Chi R. Interleukin-1 inhibits cholesterol side-chain cleavage cytochrome P450 expression in primary cultures of Leydig cells. Endocrinology. 1991;129:1305–1311. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-3-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauduit C, Chauvin MA, Hartman DJ, Revol A, Morera AM, Benahmed M. Interleukin-1 alpha as potent inhibitor of gonadotropin action in porcine Leydig cells: site(s) of action. Biol Reprod. 1992;46:1119–1126. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.6.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven G, Cailleau J, Damme JV, Billiau A. Interleukin-1 stimulates steroidogenesis in cultured rat Leydig cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1988;57:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(88)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren DW, Pasupuleti V, Lu Y, Platler BW, Horton R. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 stimulate testosterone secretion in adult male rat Leydig cells in vitro. J Androl. 1990;11:353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Khan SJ, Dorrington JH. Interleukin-1 stimulates deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in immature rat Leydig cells in vitro. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1853–1857. doi: 10.1210/en.131.4.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen PE, Pollard JW. Normal sexual function in male mice lacking a functional type I interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor. Endocrinology. 1998;139:815–818. doi: 10.1210/en.139.2.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales DB. Testicular macrophage modulation of Leydig cell steroidogenesis. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;57:3–18. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TT, Brown KJ. Spermatic cord torsion: loss of spermatogenesis despite return of blood flow. Biol Reprod. 1993;49:401–407. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LA, Turner TT. Leydig cell function after experimental testicular torsion despite loss of spermatogenesis. J Androl. 1995;16:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner TT, Miller DW. On the synthesis and secretion of rat seminiferous tubule proteins in vivo after ischemia and germ cell loss. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1275–1284. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysiak JJ, Turner SD, Turner TT. Molecular pathway of germ cell apoptosis following ischemia/reperfusion of the rat testis. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1465–1472. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read MA, Whitely MZ, Gupta S, Pierce JW, Best J, Davis RJ, Collins T. Tumor necrosis factor α-induced E-selectin expression is activated by the nuclear factor-κB and c-jun N-terminal kinase/p38 mitogen activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2753–2761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel EJ, Ley K. Distinct phenotype of E-selectin-deficient mice. E-selectin is required for slow leukocyte rolling in vivo. Circ Res. 1996;79:1196–1204. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz TE, Lombard LA, Tyler SA, Norris WP. Pathology and familial incidence of orchitis and its relation to thyroiditis in a closed beagle colony. Exp Mol Pathol. 1976;24:142–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(76)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung KSK, Ellis L, Teuscher C, Meng A, Blaustein JC, Kohno S, Howell R. The black mink (mustela vision): a natural model of immunologic male infertility. J Exp Med. 1981;154:1016–1032. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.4.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi PE, Kosuda LL, Hsu KC, Andres GA. Immune complex orchitis in vasectomized rabbits. J Exp Med. 1976;143:382–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung KSK. Allergic orchitis lesions are adoptively transferred from vasoligated guinea pigs to syngeneic recipients. Science. 1978;201:833–835. doi: 10.1126/science.684410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi O, Nishizuka Y. Expermental autoimmune orchitis after neonatal thymectomy in the mouse. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;46:425–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung KSK, Menge AC. Sperm and testicular autoimmunity. In: Rose NF, Mackay IR, editor. In The Autoimmune Diseases. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 537–590. [Google Scholar]

- Frungieri MB, Calandra RS, Lustig L, Meineke V, Khon FM, Vogt HJ, Mayerhofer A. Macrophages in the testis of infertile men: number, distribution pattern and identification of expressed genes by laser-microdissection and RT-PCR analysis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:298–306. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]