Abstract

Hepatic production and release of endothelin-1 (ET-1) binding to endothelin B (ETB) receptors, overexpressed in the lung microvasculature, is associated with accumulation of pro-angiogenic monocytes and vascular remodeling in experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) after common bile duct ligation (CBDL). We have recently found that lung vascular monocyte adhesion and angiogenesis in HPS involve interaction of endothelial C-X3-C motif ligand 1 (CX3CL1) with monocyte CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1), although whether ET-1/ETB receptor activation influences these events is unknown. Our aim was to define if ET-1/ETB receptor activation modulates CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling and lung angiogenesis in experimental HPS. A selective ETB receptor antagonist, BQ788, was given for 2 weeks to 1-week CBDL rats. ET-1 (±BQ788) was given to cultured rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells overexpressing ETB receptors. BQ788 treatment significantly decreased lung angiogenesis, monocyte accumulation, and CX3CL1 levels after CBDL. ET-1 treatment significantly induced CX3CL1 production in lung microvascular endothelial cells, which was blocked by inhibitors of Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/ERK pathways. ET-1–induced ERK activation was Ca2+ independent. ET-1 administration also increased endothelial tube formation in vitro, which was inhibited by BQ788 or by blocking Ca2+ and MEK/ERK activation. CX3CR1 neutralizing antibody partially inhibited ET-1 effects on tube formation. These findings identify a novel mechanistic interaction between the ET-1/ETB receptor axis and CX3CL1/CX3CR1 in mediating pulmonary angiogenesis and vascular monocyte accumulation in experimental HPS.

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension result in vascular alterations in several organ systems, which impair the function of these organs.1,2 The hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is one such complication, in which intrapulmonary vascular abnormalities cause abnormal arterial gas exchange in 5% to 30% of cirrhotic patients.3–5 The presence of HPS significantly decreases quality of life and increases mortality in those affected.6 Currently, the pathogenesis of vascular alterations in HPS is incompletely understood, limiting the development of effective medical therapies.

Chronic common bile duct ligation (CBDL) in the rat is an established experimental model of HPS that reproduces the physiological abnormalities of human disease.7–16 These animals develop pulmonary microvascular dilations and also develop vascular remodeling, which is linked to the accumulation of intravascular monocytes and vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) production.11,12,17,18 Pulmonary vasodilation results, in large part, from Ca2+-dependent and protein kinase B/Akt–independent activation of pulmonary vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)/NO, by hepatic production and release of endothelin-1 (ET-1) and stimulation of lung vascular endothelin B (ETB) receptors.9,19 ET-1/ETB receptor activation also enhances pulmonary vascular monocyte accumulation,14 thereby promoting angiogenesis through monocyte VEGF-A production and activation of Akt and ERK. However, how ET-1/ETB receptor activation modulates monocyte accumulation and whether ETB receptor activation has direct effects on angiogenesis are unknown.

We have recently found that the chemokine ligand/receptor pair C-X3-C motif ligand 1 (CX3CL1)/CX3C chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1) is up-regulated in the pulmonary microvasculature after CBDL and contributes to monocyte accumulation and to angiogenesis after CBDL.20 Interaction between the membrane-bound form of CX3CL1 with CX3CR1 is unique in the ability to cause firm adhesion between cell types (monocyte-endothelium).21–24 In addition, the secreted soluble form of CX3CL1, through interaction with the CX3CR1 on endothelial cells, can drive angiogenesis through Akt and ERK activation.25 However, whether ET-1/ETB receptor activation after CBDL influences monocyte accumulation or angiogenesis by affecting lung CX3CL1/CX3CR1 expression has not been tested. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to define if the ET-1/ETB receptor activation modulates the pulmonary CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis and to determine how it contributes to vascular remodeling in experimental HPS. To do this, we assessed the effects of selective ET receptor inhibition on pulmonary angiogenesis and CX3CL1/CX3CR1 expression in vivo and evaluated the effects of exogenous ET-1 on pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell CX3CL1 expression and angiogenesis in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA), 250 to 300 g, were subjected to CBDL (the common bile duct was doubly ligated and divided) or sham operation (mobilization of the common bile duct without ligation), after i.p. injection of 80/10 mg/kg ketamine/xylazine to achieve anesthesia.8,14,26 A selective ETB receptor antagonist, BQ788 (1 × 10−7 mol/day; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or saline was given i.v. using a miniosmotic pump (ALZET model 2002; ALZET, Cupertino, CA) placed into the femoral vein for 2 weeks to 1-week CBDL rats, as previously described.14 All assessments were made at 3 weeks after surgery. Eight animals were used in each group. Portal venous pressure and spleen weight were measured to evaluate the development of portal hypertension. Lung and plasma samples were obtained for further analysis. The study was approved by the University of Texas at Houston Health Science Center Animal Welfare Committee and conformed to NIH guidelines on the use of laboratory animals.

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

Arterial blood was drawn from the femoral artery, as previously described,8,12,14 and analyzed on an ABL80 FLEX blood gas analyzer (Radiometer America, Westlake, OH). The alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient (AaPO2) was calculated as follows:

| (1) |

Immunofluorescence and IHC Data

Sections (5 μm thick) of 4% paraformaldehyde, paraffin-fixed lung and liver tissues were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies. For immunofluorescent staining of ED1 (a monocyte marker; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and factor VIII (FVIII; Cell Marque, Austin, TX), Texas Red and fluorescein secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) were used. For immunostaining of ED1, ED2 (tissue resident macrophage marker; Serotec), CD3 (T-cell marker; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and CD45R (B-cell marker; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), biotinylated secondary antibodies were used. After incubation with streptavidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase (Vector Laboratories), peroxidase activity was detected with the DAB Peroxidase Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories). Sections are imaged with a Nikon Eclipse E200 Binocular Microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Controls are incubated with secondary antibody only.

Lung Microvessel Density Quantitation

The degree of pulmonary angiogenesis was evaluated by quantifying microvessel densities in lung sections immunostained with the endothelial marker FVIII, as previously described.11,20 All stained objects were counted in a blinded manner. Vessels with thick muscular walls or larger than 100 μm in diameter were excluded. Five randomly scanned fields of three sections from each animal were investigated. The average microvessel count in each group was expressed relative to the count of the sham group as fold control values.

Endothelial Cell Culture

Rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (RPMVECs; Vec Technologies, Rensselaer, NY) were maintained and subcultured in complete media MCDB-131 (Vec Technologies) at 37°C in the presence of humidified 95% air and 5% CO2. Cell passages were between 2 and 10.

Adenoviral RPMVEC Infection and Treatments

RPMVECs were plated in 6-well plates and allowed to reach 80% confluence. Adenoviral-CMV-ETB receptor constructs (1000 viral particle per cell) were added to cells for 24 to 48 hours to recapitulate in vivo alterations of HPS, as previously described.19 Adenovirus-cytomegalovirus–green fluorescent protein (AdCMV-GFP) constructs were used as control. After transfection, cells were stimulated with 1 to approximately 50 nmol/L ET-1 (Bachem Americas, Inc, Torrance, CA) in the absence or presence of a selective ETB receptor antagonist (BQ788) and specific inhibitors for the phospholipase C (PLC)/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin pathway [U73122, 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), BAPTA acetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM), and W7], mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/ERK (U0126), and Akt (wortmannin) (Calbiochem). Cell and supernatant CX3CL1 expression was measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Akt and ERK phosphorylation was assessed by using Western blot analysis.

Measurement of Cell Culture Medium CX3CL1 Levels

RPMVEC supernatant CX3CL1 levels were measured with a commercial ELISA kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA from lung or RPMVECs was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) reagent, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was prepared using The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System and TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for rat CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 were from Life Technologies. Expression levels were normalized to expression of 18S rRNA.

Western Blot Analysis

Equal amounts of proteins from the lung or cell lysates, obtained as previously described, were fractionated on Criterion Tris-HCl Gel (4% to 20%; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Incubation with primary antibodies against ED1, Akt, p-Akt (Ser473), ERK, and p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc, Danvers, MA) was followed by addition of horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies and detection with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate Pico-West luminol reagent (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL). The density of autoradiographic signals was assessed with a ScanMaker i900 scanner (Microtek Lab, Carson, CA) and quantitated with ImageJ software version 1.47 (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Endothelial Tube Formation Assay

ET-1 stimulation of endothelial cell tube formation (in vitro angiogenesis) was assessed by culturing RPMVECs on growth factor–reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). RPMVECs were transfected with AdCMV-ETB receptor constructs (1000 viral particle per cell) for 40 hours, as previously described. A total of 4 × 104 transfected RPMVECs per well were added to a 48-well plate coated with Matrigel and incubated (Eagle's basal medium-2 with 1.5% fetal bovine serum) for 3 to 12 hours at 37°C. ET-1 (10 nmol/L) was administered in the presence or absence of a selective ETB receptor antagonist (BQ788) and specific inhibitors for the PLC/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin pathway (U73122, 2-APB, BAPTA-AM, W7), MEK/ERK (U0126), Akt (wortmannin), and an anti-CX3CR1 neutralizing antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs, East Orange, NJ). Five random fields per well were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E200 Binocular Microscope. Endothelial tubular structures were skeletonized, and total tube length was quantified in a blinded manner and expressed as fold control values.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with the Student's t-test or the analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons between groups. Measurements are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance was designated as P < 0.05.

Results

Selective ETB Receptor Inhibition Blocks Lung Chemokine CX3CL1 Expression and Monocyte Accumulation in Experimental HPS

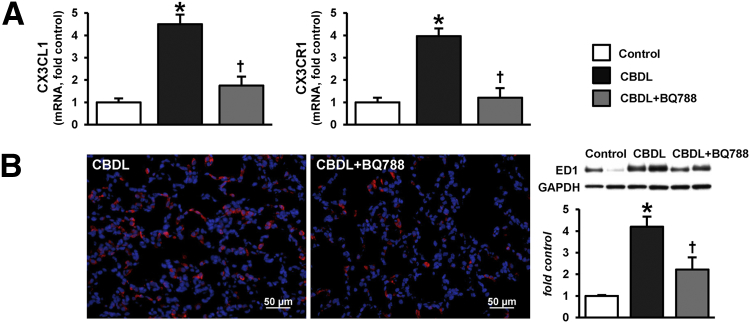

To evaluate the specific effects of ETB receptor blockade on lung monocyte alterations in experimental HPS, a selective ETB receptor antagonist, BQ788, was given to 1-week CBDL animals for 2 weeks, as previously described.14 Lung mRNA levels of CX3CL1 and its receptor, CX3CR1, were measured by real-time RT-PCR. Monocyte accumulation in the lung vasculature was assessed by ED1 (CD68, a pan-monocyte marker) immunohistochemistry (IHC) and protein levels. Relative to sham animals, CBDL animals developed significant portal hypertension, reflected by elevated portal venous pressure and spleen weight and a widened AaPO2, indicating the development of HPS. BQ788 administration to CBDL animals improved gas exchange abnormalities without influencing portal hypertension (Supplemental Figure S1), similar to prior reports.14

CBDL also resulted in a marked increase in pulmonary CX3CL1 expression and endothelial staining, which was accompanied by vascular monocyte infiltration, consistent with our prior findings.20 These increases in lung were significantly attenuated by the blockade of the ETB receptor with BQ788 (Figure 1). CX3CR1 mRNA levels also increased in CBDL lung, reflecting the increase in monocyte numbers on the basis of ED1 IHC and protein levels. Accordingly, the decline in lung vascular monocyte accumulation after BQ788 administration was associated with a reduction in lung CX3CR1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of ETB receptor inhibition with BQ788 on lung CX3CL1/CX3CR1 levels and monocyte accumulation after CBDL. A: mRNA levels for CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 in lung. B: Representative immunofluorescence staining for ED1 (monocyte marker, red) in lung and representative immunoblots and summary of lung ED1 protein levels. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8 animals for each group). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus CBDL. Scale bar = 50 μm. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

To define whether monocyte infiltration and modulation by ETB receptor inhibition are selective events in the lung after CBDL, we evaluated other immune cell types in the lung and assessed liver monocyte subsets. At the light level, cells infiltrating the lung appeared to be mononuclear and stained for ED1, not ED2 (CD163, resident macrophage marker) (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S2). When CBDL lung (with and without BQ788 treatment) was stained for CD3 (T-cell marker) and CD45R (B-cell marker), there was no detectable accumulation, supporting a selective influx of monocytes (Supplemental Figure S3). Both infiltrated circulating monocyte and resident macrophage (Kupffer cell) subsets contribute to liver injury after CBDL.27–29 To determine whether systemic ETB receptor blockade influences these cells, we assessed ED1 (monocyte marker) and ED2 (resident Kupffer cell marker) staining. There was a marked increase in both ED1 and ED2 staining in the liver after CBDL, which was not influenced by BQ788, supporting a lack of effect of ETB receptors on monocyte alterations in the liver (Supplemental Figure S4).

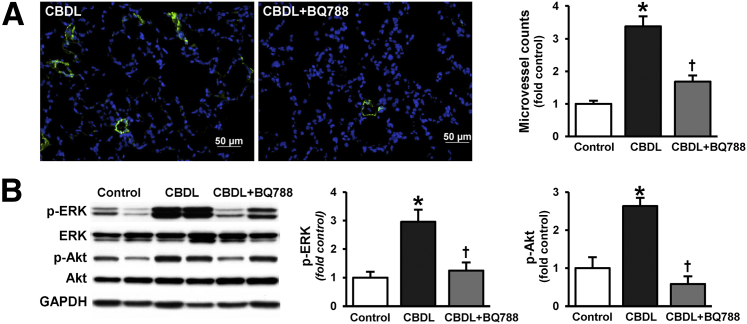

Selective ETB Receptor Antagonist Decreases Lung Angiogenesis and Angiogenic Signaling Pathway Activation

To define whether changes in CX3CL1/CX3CR1 expression and monocyte accumulation due to ETB receptor inhibition influence activation of angiogenic pathways and angiogenesis, we assessed lung Akt and ERK activation and angiogenesis after CBDL, with or without BQ788 treatment (Figure 2). Akt and ERK phosphorylation and lung angiogenesis were significantly increased after CBDL, as previously described,11,20 and were ameliorated by BQ788 administration.

Figure 2.

Effects of ETB receptor inhibition with BQ788 on pulmonary angiogenesis and Akt and ERK phosphorylation after CBDL. A: Representative immunofluorescence images of lung microvessel staining (FVIII, green) and quantitation of microvessel density after CBDL. B: Representative immunoblots of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) after CBDL and summary of protein levels for p-Akt/Akt and p-ERK/ERK. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8 animals for each group). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus CBDL. Scale bar = 50 μm. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

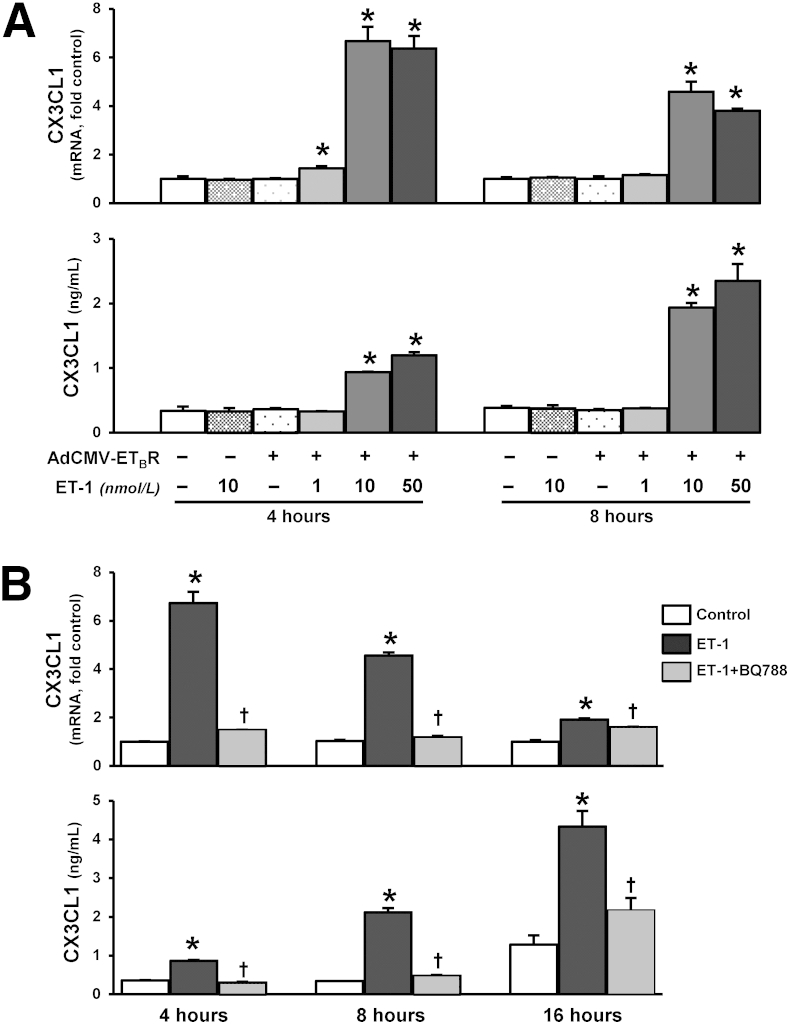

Effects of ET-1 on CX3CL1 Expression in Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells

To explore whether the ET-1/ETB receptor axis directly influences endothelial CX3CL1 expression, we generated ETB receptor overexpressing RPMVECs as an in vitro model of pulmonary microvascular alterations in experimental HPS (Supplemental Figure S5).14,17,19,30 CX3CL1 mRNA and supernatant protein levels were quantified by real-time RT-PCR and ELISA. ET-1 administration to control RPMVECs did not alter CX3CL1 mRNA or protein production. ET-1 stimulation of ETB receptor overexpressing RPMVECs induced a significant dose- and time-dependent increase in cellular CX3CL1 mRNA production and supernatant protein levels (Figure 3A), which were blocked by ETB receptor inhibition (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Effects of ET-1 on CX3CL1 production in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. A: CX3CL1 mRNA and supernatant protein levels in RPMVECs treated with 1, 10, and 50 nmol/L ET-1 for 4 and 8 hours, respectively. B: CX3CL1 mRNA and supernatant protein levels in 10 nmol/L ET-1–treated RPMVECs in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788, respectively, for 4, 8, and 16 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus ET-1 treatment.

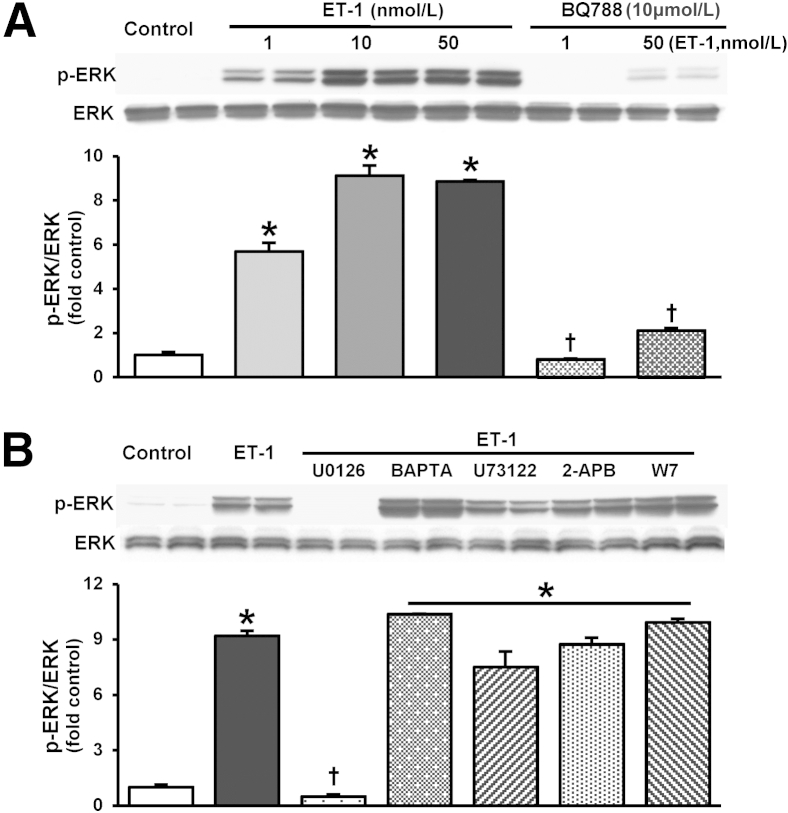

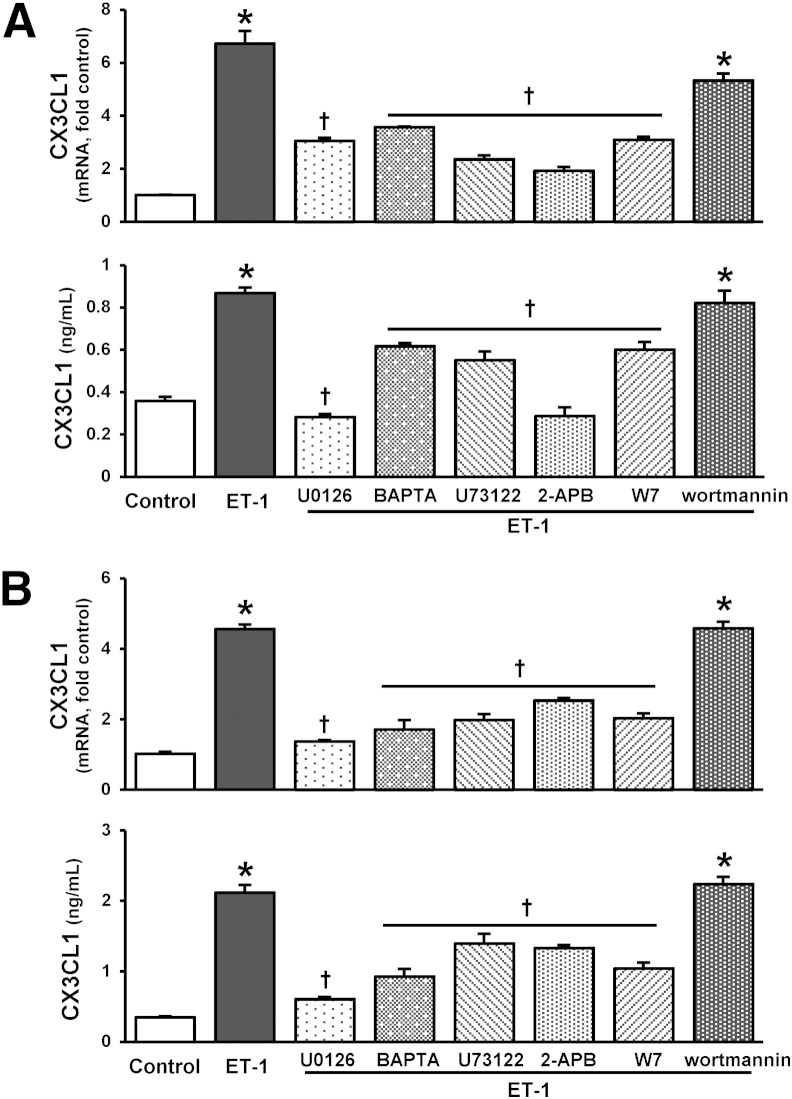

To define pathways involved in ET-1 stimulation of CX3CL1 in RPMVECs, we assessed activation of signaling pathways recognized either to regulate endothelial CX3CL1 production or to be activated by ETB receptor stimulation, PLC/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin, MEK/ERK, and Akt.19,31–33 ET-1 administration did not influence Akt activation in either control or ETB receptor overexpressing endothelial cells, consistent with our prior in vitro findings (Supplemental Figure S6).19 ET-1 stimulation of ETB receptor overexpressing cells resulted in ETB receptor–dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure S3), which was attenuated by specific MEK inhibition (Figure 4B), but did not induce ERK activation in control cells (Supplemental Figure S6A). The activation of ERK was not altered by Ca2+ signaling pathway inhibitors, including U73122 (PLC), 2-APB (InsP3), BAPTA-AM (calcium chelator), and W7 (calmodulin), demonstrating Ca2+-independent MEK/ERK activation (Figure 4B). Inhibition of either MEK/ERK activation or PLC/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin significantly attenuated ET-1–induced CX3CL1 mRNA and protein production, whereas Akt inhibition did not (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Effects of ET-1 on ERK activation in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. Representative immunoblots and graphs summarize ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Thr202/Tyr204) in RPMVECs treated with 1, 10, and 50 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 5 minutes (A); and 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 and inhibitors of PLC/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin pathway (5 μmol/L U73122, 20 μmol/L 2-APB, 5 μmol/L BAPTA-AM, and 10 μmol/L W7, respectively) (B). Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus ET-1 treatment.

Figure 5.

Effects of Ca2+ and MEK/ERK pathway inhibition on ET-1–stimulated CX3CL1 production in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. CX3CL1 mRNA and supernatant protein levels in RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of inhibitors of MEK/ERK (10 μmol/L U0126), PLC/InsP3/Ca2+/calmodulin pathway (5 μmol/L U73122, 20 μmol/L 2-APB, 5 μmol/L BAPTA-AM, and 10 μmol/L W7), and Akt (0.5 μmol/L wortmannin) for 4 (A) and 8 (B) hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus ET-1 treatment.

Effects of ET-1 on VEGF-A Expression in Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells

VEGF-A is also established to contribute to vascular remodeling in experimental HPS.11,20 To evaluate if ET-1 modulates expression of VEGF-A in lung endothelium, we measured VEGF-A mRNA levels after ET-1 administration in ETB-overexpressing pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. ET-1 stimulation did not influence VEGF-A expression (Supplemental Figure S7).

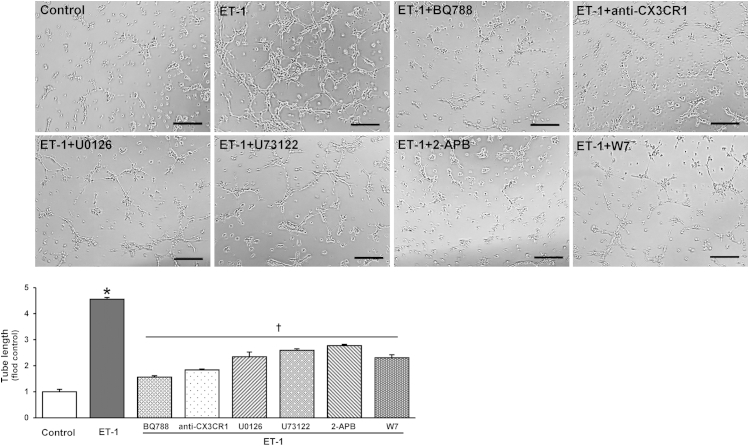

Effects of ET-1 on In Vitro Angiogenesis in Pulmonary Microvascular Endothelial Cells

To determine whether and how ET-1 modulates endothelial cell angiogenic properties, we assessed tube formation after ET-1 stimulation of ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs in the presence or absence of BQ788 (Figure 6). Relative to untreated cells, ET-1 stimulation resulted in a marked increase in tube formation expressed by relative tube length. This increase was completely inhibited by BQ788 pretreatment and was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with a neutralizing CX3CR1 antibody. Accordingly, pretreatment of endothelial cells with specific inhibitors of Ca2+ signaling and MEK/ERK also significantly decreased ET-1–stimulated tube formation to a similar degree to CX3CR1 inhibition.

Figure 6.

Effects of ET-1 on endothelial tube formation in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. Representative images of tubular structure formation and summary of relative tube length in RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of inhibitors of 10 μmol/L BQ788, 10 ng/mL anti–CX3CR1-neutralizing antibody, 5 μmol/L MEK/ERK inhibitor (U0126), and Ca2+ pathway inhibitors (2.5 μmol/L U73122, 20 μmol/L 2-APB, and 5 μmol/L W7) for 6 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05 versus control; †P < 0.05 versus ET-1 treatment. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Discussion

Our prior work has demonstrated an important role for the ET-1/ETB receptor system in the development of intrapulmonary vasodilation in experimental HPS, through the sequential activation of eNOS/NO signaling.14,15,19,30 We have also shown that lung CX3CL1 expression is increased after CBDL and drives the accumulation of VEGF-A–producing monocytes and lung angiogenesis.20 In the present study, we define that ET-1/ETB receptor activation has a novel direct effect on lung microvascular endothelial cell CX3CL1 expression, thereby linking these two pathways and the effects on the microvasculature. Specifically, we found that ET-1 stimulation of ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs in vitro directly increased CX3CL1 expression through two independent intracellular signaling pathways, MEK/ERK and Ca2+. Furthermore, inhibition of ET-1/ETB activation in vivo using a selective ETB receptor antagonist significantly reduced pulmonary CX3CL1 expression, decreased vascular monocyte accumulation, and improved angiogenesis and HPS. Finally, we found that ET-1/ETB receptor activation in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs drives tube formation in vitro, in part through increased CX3CL1 production. These observations directly link ET-1/ETB receptor activation and endothelial CX3CL1 production in the pathogenesis of pulmonary vascular alterations in experimental HPS.

In CBDL lung, monocyte accumulation and adhesion to the microvasculature are important pathogenic features that involve up-regulation and activation of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway.12,20 A variety of stimuli are recognized to increase CX3CL1 mRNA and protein expression in vascular endothelial cells, including proinflammatory cytokines (lipopolysaccharide, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, and IL-1), glucose, and resistin.34–37 These stimuli generally signal through several intracellular pathways, including mitogen-activated protein kinases (ERK and p38), NF-κB, and STAT-1, that modulate cellular CX3CL1 expression and shedding.38–40 Several of these pathways are also activated by ET-1,31,33,41–44 which is up-regulated after CBDL. In addition, ET-1 acting through either the ETA or ETB receptor, has been established to increase production of other chemokines and adhesion molecules in a variety of cell types.45–47 Therefore, we hypothesized a potential link between pulmonary microvascular ET-1/ETB receptor activation and CX3CL1 alterations in experimental HPS. Our most important finding is that ET-1, via the ETB receptor, directly induces ERK- and Ca2+-dependent and Akt-independent CX3CL1 production in rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. However, the significance of this finding is underlined by the in vivo observation that ETB receptor blockade using BQ788 also reduces CX3CL1 levels in lung in conjunction with improving HPS after CBDL. The finding that both mRNA levels and the secreted form of CX3CL1 are increased in ET-1–treated endothelial cells suggests that ET-1 may not only alter transcription, but could also influence cleavage or shedding from the membrane. CX3CL1 shedding occurs at the cell surface within the transmembrane domain and is attributed to specific sheddases, a disintegrin and metalloproteases 10 and 17 (known as tumor necrosis factor-α–converting enzymes).48–50 Further studies are needed to define if and how ET-1 directly influences shedding of CX3CL1.

Our prior work has shown that ET-1/ETB receptor activation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling stimulates eNOS activation and NO-mediated pulmonary vasodilation, independent of Akt activation after CBDL.19 This effect on Ca2+ pathways is influenced by the level of ETB receptor expression in the pulmonary microvasculature, which is increased in the setting of elevated shear stress.19 Herein, we confirm that the level of ETB receptor expression in RPMVECs influences cellular responses to ET-1 and that ET-1 does not directly activate Akt in vitro. We do identify ET-1 activation of both Ca2+- and ERK-dependent pathways as important intracellular modulators of CX3CL1 expression. Lung Akt activation is increased in vivo during angiogenesis after CBDL and is inhibited by ETB receptor, CX3CR1, or VEGF-A blockade.11,20 These findings are consistent with the concept that ET-1 effects on Akt in the pulmonary endothelium in vivo are mediated indirectly, through up-regulation of CX3CL1 autocrine/paracrine signaling and/or VEGF-A produced by adherent intravascular monocytes; each of these events activates Akt and is decreased by ETB receptor inhibition. These findings support that ET-1 initiates a cascade of alterations in the pulmonary microvasculature in the setting of increased pulmonary endothelial ETB receptor expression after CBDL, which results in activation of multiple signaling pathways in endothelial cells relevant to monocyte adherence and angiogenesis.

The in vitro endothelial cell tube formation assays are also consistent with direct and indirect effects of ET-1 on angiogenesis in the pulmonary microvascular endothelium in the setting of ETB receptor overexpression. The finding that ETB receptor inhibition blocks ET-1 effects on RPMVEC tubular structure formation is consistent with prior findings that ET-1 directly induces endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenic morphological characteristics18,51,52 and with the in vivo studies in which ETB receptor inhibition decreased angiogenesis. These effects are likely mediated through ERK and Ca2+ signaling pathways.53,54 Our observation herein that blockade of CX3CR1 also inhibits ET-1–driven tubular structure formation supports that CX3CL1 production by ET-1 results in autocrine effects on endothelial cell angiogenic potential. These findings occur in parallel to the established in vivo effects of CX3CL1 on monocyte adherence after CBDL. These results support that ET-1 modulation of endothelial CX3CL1 production is one key indirect pathway for influencing endothelial angiogenesis and monocyte adherence. Future studies need to address the precise interaction between ET-1 and CX3CL1 in pulmonary angiogenesis using genetic approaches to selectively ablate endothelial CX3CL1 expression.

In endothelial cells from other tissues, ET-1 has been reported to increase expression of members of the VEGF family (VEGF-A and VEGF-C), indirectly regulating cell proliferation and angiogenic responses.51,52,55 In contrast, our in vitro studies herein demonstrate that ET-1 does not increase VEGF-A expression in RPMVECs over a 4- to 18-hour time frame. This finding suggests that endothelial production of VEGF in response to ET-1 may vary by tissue and is consistent with the lack of effect of ET-1 on Akt activation in RPMVECs. We have identified intravascular monocytes recruited into the lung after CBDL as a major source of VEGF-A production, supporting a paracrine mechanism for monocytes in the development of lung angiogenesis in experimental HPS.11,20 However, a degree of VEGF-A staining has also been detected in the lung microvasculature once experimental HPS has developed, suggesting that additional mediators and cell types may modulate VEGF-A production in pulmonary microvasculature in vivo after CBDL.

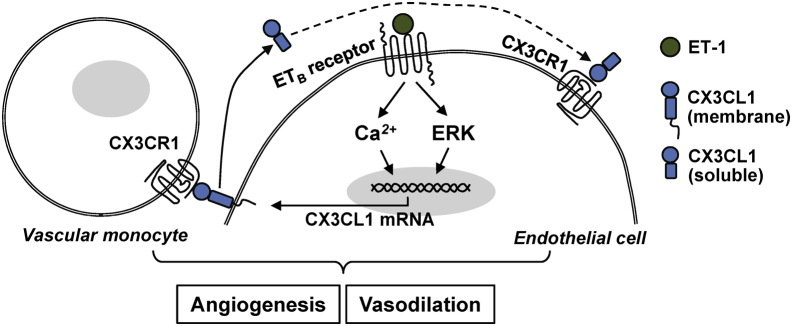

We have identified a novel synergistic interplay between ET-1 acting through the ETB receptor and increased CX3CL1 expression in RPMVECs that contributes to altered angiogenic potential and influences monocyte adhesion and the clinical expression of experimental HPS (Figure 7). These effects occur through Ca2+- and MEK/ERK-mediated intracellular signaling pathways and are supported by in vivo findings showing that ETB receptor blockade inhibits lung angiogenesis and monocyte accumulation by down-regulation of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling. This direct link between hepatic ET-1 production and pulmonary vascular alterations in experimental HPS may have relevance to human disease on the basis of the recent finding that hepatic venous ET-1 levels are elevated in patients with pulmonary microvascular dilation relative to those without pulmonary microvascular alterations.56 Understanding the cellular mechanisms of experimental HPS may provide important insight into understanding and treating human disease.

Figure 7.

Working model of the ET-1/ETB receptor axis and the pulmonary vascular endothelial CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway in the development of experimental HPS.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant 5DKR01DK056804 (M.B.F.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental Data

Effects of ETB receptor inhibition with BQ788 on portal hypertension and gas exchange after CBDL. Portal venous pressure (PVP), spleen weight, and AaPO2 in control, CBDL-treated, and BQ788-treated CBDL animals. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8 animals for each group). ∗P < 0.05 versus sham; †P < 0.05 versus CBDL.

Effects of CBDL on lung macrophage subsets. CBDL lung sections were immunostained for ED1 (CD68, monocyte marker) and ED2 (CD163, tissue resident macrophage marker). Infiltrated monocytes in the lung after CBDL were positive for ED1, but not ED2, supporting an influx of circulating monocytes. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Evaluation of lymphocyte infiltration in lung after CBDL. Lung sections were immunostained for CD3 (T-cell marker) and CD45R (B-cell marker). Normal spleen was used as a positive control. No detectable lymphocyte accumulation was seen in lung after CBDL. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Effects of BQ788 on hepatic monocyte and macrophage alterations. CBDL liver sections, with and without BQ788 treatment, were immunostained for ED1 (CD68, monocyte marker) and ED2 (CD163, tissue resident macrophage/Kupffer cell marker). BQ788 neither influences ED1 nor ED2 staining in the liver after CBDL. Scale bar = 100 μm.

ETB receptor mRNA expression in RPMVECs transfected with AdCMV-ETB receptor constructs. ETB receptor mRNA levels in RPMVECs infected with control (AdCMV-GFP) or AdCMV-ETB receptor constructs for 40 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05.

Effects of ET-1 on Akt and ERK activation in RPMVECs. A: Representative immunoblots of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) in control RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 5 and 15 minutes, respectively. ET-1 administration did not influence ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation in control cells. B: Representative immunoblots of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) in RPMVECs transfected with AdCMV-ETB receptor or AdCMV-GFP constructs and treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 5 and 15 minutes, respectively. ET-1 stimulation induced a significant ETB receptor–dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas Akt activation was not influenced.

Effects of ET-1 on VEGF-A production in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. VEGF-A mRNA levels in RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 4, 8, and 16 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ET-1 stimulation did not influence VEGF-A mRNA production in endothelial cells.

References

- 1.Cahill P.A., Redmond E.M., Sitzmann J.V. Endothelial dysfunction in cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;89:273–293. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee J.S., Semela D., Iredale J., Shah V.H. Sinusoidal remodeling and angiogenesis: a new function for the liver-specific pericyte? Hepatology. 2007;45:817–825. doi: 10.1002/hep.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Roisin R., Krowka M.J. Hepatopulmonary syndrome: a liver-induced lung vascular disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2378–2387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Roisin R., Krowka M.J., Herve P., Fallon M.B., ERS Task Force Pulmonary-Hepatic Vascular Disorders Scientific Committee ERS Task Force PHD Scientific Committee Pulmonary-hepatic vascular disorders (PHD) Eur Respir J. 2004;24:861–880. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00010904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schenk P., Schoniger-Hekele M., Fuhrmann V., Madl C., Silberhumer G., Muller C. Prognostic significance of the hepatopulmonary syndrome in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallon M.B., Krowka M.J., Brown R.S., Trotter J.F., Zacks S., Roberts K.E., Shah V.H., Kaplowitz N., Forman L., Wille K., Kawut S.M. Impact of hepatopulmonary syndrome on quality of life and survival in liver transplant candidates. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1168–1175. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sztrymf B., Rabiller A., Nunes H., Savale L., Lebrec D., LePape A., de Montpreville V., Mazmanian M., Humbert M., Herve P. Prevention of hepatopulmonary syndrome by pentoxifylline in cirrhotic rats. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:752–758. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fallon M.B., Abrams G.A., McGrath J.W., Hou Z., Luo B. Common bile duct ligation in the rat: a model of intrapulmonary vasodilatation and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G779–G784. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo B., Tang L., Wang Z., Zhang J., Ling Y., Feng W., Sun J.Z., Stockard C.R., Frost A.R., Chen Y.F., Grizzle W.E., Fallon M.B. Cholangiocyte endothelin 1 and transforming growth factor beta1 production in rat experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thenappan T., Goel A., Marsboom G., Fang Y.H., Toth P.T., Zhang H.J., Kajimoto H., Hong Z., Paul J., Wietholt C., Pogoriler J., Piao L., Rehman J., Archer S.L. A central role for CD68(+) macrophages in hepatopulmonary syndrome: reversal by macrophage depletion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1080–1091. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1303OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J., Luo B., Tang L., Wang Y., Stockard C.R., Kadish I., Van Groen T., Grizzle W.E., Ponnazhagan S., Fallon M.B. Pulmonary angiogenesis in a rat model of hepatopulmonary syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1070–1080. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J., Ling Y., Luo B., Tang L., Stockard C., Grizzle W.E., Fallon M.B. Analysis of pulmonary heme oxygenase-1 and nitric oxide synthase alterations in experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1441–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunes H., Lebrec D., Mazmanian M., Capron F., Heller J., Tazi K.A., Zerbib E., Dulmet E., Moreau R., Dinh-Xuan A.T., Simonneau G., Herve P. Role of nitric oxide in hepatopulmonary syndrome in cirrhotic rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:879–885. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2009008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling Y., Zhang J., Luo B., Song D., Liu L., Tang L., Stockard C., Grizzle W., Ku D., Fallon M.B. The role of endothelin-1 and the endothelin B receptor in the pathogenesis of experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. Hepatology. 2004;39:1593–1602. doi: 10.1002/hep.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallon M.B., Abrams G.A., Luo B., Hou Z., Dai J., Ku D.D. The role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the pathogenesis of a rat model of hepatopulmonary syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:606–614. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9247483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L., Zhang M., Luo B., Abrams G.A., Fallon M.B. Biliary cyst fluid from common bile duct ligated rats stimulates eNOS in pulmonary artery endothelial cells: a potential role in hepatopulmonary syndrome. Hepatology. 2001;33:722–727. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo B., Liu L., Tang L., Zhang J., Stockard C., Grizzle W., Fallon M. Increased pulmonary vascular endothelin B receptor expression and responsiveness to endothelin-1 in cirrhotic and portal hypertensive rats: a potential mechanism in experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. J Hepatol. 2003;38:556–563. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang M., Luo B., Chen S.J., Abrams G.A., Fallon M.B. Endothelin-1 stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the pathogenesis of hepatopulmonary syndrome. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G944–G952. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.5.G944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang L., Luo B., Patel R.P., Ling Y., Zhang J., Fallon M.B. Modulation of pulmonary endothelial endothelin B receptor expression and signaling: implications for experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L1467–L1472. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00446.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J., Yang W., Luo B., Hu B., Maheshwari A., Fallon M.B. The role of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 in pulmonary angiogenesis and intravascular monocyte accumulation in rat experimental hepatopulmonary syndrome. J Hepatol. 2012;57:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazan J.F., Bacon K.B., Hardiman G., Wang W., Soo K., Rossi D., Greaves D.R., Zlotnik A., Schall T.J. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–644. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai T., Hieshima K., Haskell C., Baba M., Nagira M., Nishimura M., Kakizaki M., Takagi S., Nomiyama H., Schall T.J., Yoshie O. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teupser D., Pavlides S., Tan M., Gutierrez-Ramos J.C., Kolbeck R., Breslow J.L. Major reduction of atherosclerosis in fractalkine (CX3CL1)-deficient mice is at the brachiocephalic artery, not the aortic root. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17795–17800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408096101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volin M.V., Huynh N., Klosowska K., Reyes R.D., Woods J.M. Fractalkine-induced endothelial cell migration requires MAP kinase signaling. Pathobiology. 2010;77:7–16. doi: 10.1159/000272949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S.J., Namkoong S., Kim Y.M., Kim C.K., Lee H., Ha K.S., Chung H.T., Kwon Y.G., Kim Y.M. Fractalkine stimulates angiogenesis by activating the Raf-1/MEK/ERK- and PI3K/Akt/eNOS-dependent signal pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2836–H2846. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00113.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo B., Liu L., Tang L., Zhang J., Ling Y., Fallon M.B. ET-1 and TNF-alpha in HPS: analysis in prehepatic portal hypertension and biliary and nonbiliary cirrhosis in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G294–G303. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00298.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karlmark K., Weiskirchen R., Zimmermann H., Gassler N., Ginhoux F., Weber C., Merad M., Luedde T., Trautwein C., Tacke F. Hepatic recruitment of the inflammatory Gr1+ monocyte subset upon liver injury promotes hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:261–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.22950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramachandran P., Iredale J.P. Macrophages: central regulators of hepatic fibrogenesis and fibrosis resolution. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1417–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wynn T.A., Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:245–257. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L., Luo B., Wang Z., Abrams G.A., Fallon M.B. Endothelin-1 stimulates eNOS expression and activity in rat pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Hepatology. 2001;34:184A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Q.W., Edvinsson L., Xu C.B. Role of ERK/MAPK in endothelin receptor signaling in human aortic smooth muscle cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creighton J.R., Masada N., Cooper D.M., Stevens T. Coordinate regulation of membrane cAMP by Ca2+-inhibited adenylyl cyclase and phosphodiesterase activities. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L100–L107. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00083.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deliu E., Brailoiu G.C., Mallilankaraman K., Wang H., Madesh M., Undieh A.S., Koch W.J., Brailoiu E. Intracellular endothelin type B receptor-driven Ca2+ signal elicits nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41023–41031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.418533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Imaizumi T., Yoshida H., Satoh K. Regulation of CX3CL1/fractalkine expression in endothelial cells. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2004;11:15–21. doi: 10.5551/jat.11.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumiya T., Ota K., Imaizumi T., Yoshida H., Kimura H., Satoh K. Characterization of synergistic induction of CX3CL1/fractalkine by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma in vascular endothelial cells: an essential role for TNF-alpha in post-transcriptional regulation of CX3CL1. J Immunol. 2010;184:4205–4214. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manduteanu I., Dragomir E., Calin M., Pirvulescu M., Gan A.M., Stan D., Simionescu M. Resistin up-regulates fractalkine expression in human endothelial cells: lack of additive effect with TNF-alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manduteanu I., Pirvulescu M., Gan A.M., Stan D., Simion V., Dragomir E., Calin M., Manea A., Simionescu M. Similar effects of resistin and high glucose on P-selectin and fractalkine expression and monocyte adhesion in human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:1443–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida M., Ito T., Nakamura T., Igarashi H., Oono T., Fujimori N., Kawabe K., Suzuki K., Jensen R.T., Takayanagi R. ERK pathway and sheddases play an essential role in ethanol-induced CX3CL1 release in pancreatic stellate cells. Lab Invest. 2013;93:41–53. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee A.S., Jung Y.J., Kim D.H., Lee T.H., Kang K.P., Lee S., Lee N.H., Sung M.J., Kwon D.Y., Park S.K., Kim W. Epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate decreases tumor necrosis factor-α–induced fractalkine expression in endothelial cells by suppressing NF-κB. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:503–510. doi: 10.1159/000257494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Isozaki T., Otsuka K., Sato M., Takahashi R., Wakabayashi K., Yajima N., Miwa Y., Kasama T. Synergistic induction of CX3CL1 by interleukin-1beta and interferon-gamma in human lung fibroblasts: involvement of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 signaling pathways. Transl Res. 2011;157:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cramer H., Schmenger K., Heinrich K., Horstmeyer A., Boning H., Breit A., Piiper A., Lundstrom K., Muller-Esterl W., Schroeder C. Coupling of endothelin receptors to the ERK/MAP kinase pathway: roles of palmitoylation and G(alpha)q. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:5449–5459. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulasekaran P., Scavone C.A., Rogers D.S., Arenberg D.A., Thannickal V.J., Horowitz J.C. Endothelin-1 and transforming growth factor-beta1 independently induce fibroblast resistance to apoptosis via AKT activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:484–493. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0447OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerstung M., Roth T., Dienes H.P., Licht C., Fries J.W. Endothelin-1 induces NF-kappaB via two independent pathways in human renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27:294–300. doi: 10.1159/000101999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McWhinnie R., Pechkovsky D.V., Zhou D., Lane D., Halayko A.J., Knight D.A., Bai T.R. Endothelin-1 induces hypertrophy and inhibits apoptosis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L278–L286. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00111.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen P., Shibata M., Zidovetzki R., Fisher M., Zlokovic B.V., Hofman F.M. Endothelin-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 modulation in ischemia and human brain-derived endothelial cell cultures. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;116:62–73. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simonson M.S., Ismail-Beigi F. Endothelin-1 increases collagen accumulation in renal mesangial cells by stimulating a chemokine and cytokine autocrine signaling loop. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:11003–11008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li L., Chu Y., Fink G.D., Engelhardt J.F., Heistad D.D., Chen A.F. Endothelin-1 stimulates arterial VCAM-1 expression via NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in mineralocorticoid hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:997–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000095980.43859.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garton K.J., Gough P.J., Blobel C.P., Murphy G., Greaves D.R., Dempsey P.J., Raines E.W. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates the cleavage and shedding of fractalkine (CX3CL1) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37993–38001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hurst L.A., Bunning R.A., Sharrack B., Woodroofe M.N. siRNA knockdown of ADAM-10, but not ADAM-17, significantly reduces fractalkine shedding following pro-inflammatory cytokine treatment in a human adult brain endothelial cell line. Neurosci Lett. 2012;521:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hundhausen C., Misztela D., Berkhout T.A., Broadway N., Saftig P., Reiss K., Hartmann D., Fahrenholz F., Postina R., Matthews V., Kallen K.J., Rose-John S., Ludwig A. The disintegrin-like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood. 2003;102:1186–1195. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spinella F., Garrafa E., Di Castro V., Rosano L., Nicotra M.R., Caruso A., Natali P.G., Bagnato A. Endothelin-1 stimulates lymphatic endothelial cells and lymphatic vessels to grow and invade. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2669–2676. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salani D., Taraboletti G., Rosano L., Di Castro V., Borsotti P., Giavazzi R., Bagnato A. Endothelin-1 induces an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and stimulates neovascularization in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1703–1711. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chim S.M., Qin A., Tickner J., Pavlos N., Davey T., Wang H., Guo Y., Zheng M.H., Xu J. EGFL6 promotes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis through the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22035–22046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung H.J., Kim J.H., Shim J.S., Kwon H.J. A novel Ca2+/calmodulin antagonist HBC inhibits angiogenesis and down-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25867–25874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garrafa E., Caprara V., Di Castro V., Rosano L., Bagnato A., Spinella F. Endothelin-1 cooperates with hypoxia to induce vascular-like structures through vascular endothelial growth factor-C, -D and -A in lymphatic endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2012;91:638–643. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koch D.G., Bogatkevich G., Ramshesh V., Lemasters J.J., Uflacker R., Reuben A. Elevated levels of endothelin-1 in hepatic venous blood are associated with intrapulmonary vasodilatation in humans. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:516–523. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1905-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effects of ETB receptor inhibition with BQ788 on portal hypertension and gas exchange after CBDL. Portal venous pressure (PVP), spleen weight, and AaPO2 in control, CBDL-treated, and BQ788-treated CBDL animals. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8 animals for each group). ∗P < 0.05 versus sham; †P < 0.05 versus CBDL.

Effects of CBDL on lung macrophage subsets. CBDL lung sections were immunostained for ED1 (CD68, monocyte marker) and ED2 (CD163, tissue resident macrophage marker). Infiltrated monocytes in the lung after CBDL were positive for ED1, but not ED2, supporting an influx of circulating monocytes. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Evaluation of lymphocyte infiltration in lung after CBDL. Lung sections were immunostained for CD3 (T-cell marker) and CD45R (B-cell marker). Normal spleen was used as a positive control. No detectable lymphocyte accumulation was seen in lung after CBDL. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Effects of BQ788 on hepatic monocyte and macrophage alterations. CBDL liver sections, with and without BQ788 treatment, were immunostained for ED1 (CD68, monocyte marker) and ED2 (CD163, tissue resident macrophage/Kupffer cell marker). BQ788 neither influences ED1 nor ED2 staining in the liver after CBDL. Scale bar = 100 μm.

ETB receptor mRNA expression in RPMVECs transfected with AdCMV-ETB receptor constructs. ETB receptor mRNA levels in RPMVECs infected with control (AdCMV-GFP) or AdCMV-ETB receptor constructs for 40 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ∗P < 0.05.

Effects of ET-1 on Akt and ERK activation in RPMVECs. A: Representative immunoblots of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) in control RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 5 and 15 minutes, respectively. ET-1 administration did not influence ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation in control cells. B: Representative immunoblots of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) in RPMVECs transfected with AdCMV-ETB receptor or AdCMV-GFP constructs and treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 5 and 15 minutes, respectively. ET-1 stimulation induced a significant ETB receptor–dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas Akt activation was not influenced.

Effects of ET-1 on VEGF-A production in ETB receptor–overexpressing RPMVECs. VEGF-A mRNA levels in RPMVECs treated with 10 nmol/L ET-1 in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L BQ788 for 4, 8, and 16 hours. Values are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments in duplicate). ET-1 stimulation did not influence VEGF-A mRNA production in endothelial cells.