Introduction

Inherited bleeding disorders are caused by the deficiency or dysfunction of plasma proteins required for the development of a physiological hemostatic process1,2. Von Willebrand disease (vWD), haemophilia A and haemophilia B are the most common inherited disorders of hemostasis. In their severe forms, these disorders are life-threatening. However advanced treatment modalities have enabled even severely affected patients to reach the same life expectancy of the general male population at least in high-income countries3,4. Indeed, after the dramatic events of widespread blood-borne virus transmission in the 1970s–1980s in haemophilic patients, leading to a 35-to-40-year reduction in life expectancy in Canadian patients5, there has been a strong drive towards continuous improvement, primarily in the safety of replacement therapy6. There is now a very high degree of safety from risk of blood borne transmission of pathogens as evidenced by the absence of reported transmission of blood-borne viruses in persons with haemophilia since the late 1980s to date7. The safety of current replacement therapies was recently confirmed by a prospective surveillance program ongoing since 2008 and based on regular monitoring of 22,242 European patients (European Haemophilia Safety Surveillance System; www.euhass.org). Regular factor prophylaxis as a therapeutic regimen has been proven effective in preventing haemophilic arthropathy8. Even in the presence of neutralizing antibodies (inhibitors) directed against the deficient clotting factor, particularly in haemophilia A, bleeding can usually be treated successfully using activated variants of coagulation factors9. Moreover, immune tolerance induction (ITI), based on the long-term intravenous infusion of large doses of FVIII, eradicates inhibitors in as many as two-thirds of patients10. Therefore, improving quality of life has become the primary objective of care in developed countries; thus multiple modalities (psychosocial support, physiotherapy, integration into community life, etc), not just the infusion of the deficient factor, are made available to the patient and his family, to allow them to fully experience good health.

The haemophilia care in Canada

Canada is a very large country geographically. With a total of 9.98 million square kilometres, Canada is the world’s second-largest country by total area consisting of 10 provinces and 3 territories. Provinces have a great deal of power relative to the federal government, with jurisdiction over many public goods such as health care (but also education, welfare, and intra-provincial transportation). Current Canada’s total population estimate (http://www.statcan.gc.ca/) is 35,295,770. The Canadian Hemophilia Registry identified a total of 2,966 haemophilia A patients, 690 haemophilia B patients, 3,963 patients affected by vWD and 1,740 patients with other bleeding disorders, including rare platelet disorders (http://fhs.mcmaster.ca/chr/data.html). Factors usage from 2007 to 2012 is reported in Table I. In 2012 a total of 190,189,628 FVIII IU were used and the mean per capita FVIII usage was 5.39 IU while a total of 45,772,681 FIX IU consumption was registered with a mean per capita FIX usage of 1.29 IU. Some patients live many hundreds of kilometers from the nearest Haemophilia Treatment Centre (HTC). A number of strategies are used to provide care to them. Home infusion is encouraged where feasible. Specialists in the HTC create links with local practitioners to coordinate care in distant locations. Telemedicine is used to communicate with patients and their caregivers. Nurse coordinators connect extensively with patients by telephone. Some centre teams conduct outreach clinics to smaller centers where a concentration of patients reside. Programs funded by government or the local chapter of the CHS provide financial support for families to travel to the HTC for annual assessments. Electronic infusion reporting systems are used to report product use. Distribution of the 24 Haemophilia Treatment Centers (HTCs) in Canada is shown in Figure 1.

Table I.

Reported use of factor concentrates in Canada from 2007 to 2012.

| 2012–2013 | 2011–2012 | 2010–2011 | 2009–2010 | 2008–2009 | 2007–2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Product | Unit | Quantity | Quantity | Quantity | Quantity | Quantity | Quantity |

| Factor Eight Inhibitor Bypassing Activity | IU | 14.059.865 | 14.059.865 | 12.139.931 | 11.406.109 | 9.492.307 | 7.096.409 |

| Compl.prot.total Octaplex | IU | 3.360.500 | 3.360.500 | 9.942.500 | 920.000 | 12.600 | 0 |

| Factor IX | IU | 42.975.510 | 42.975.510 | 43.612.325 | 39.861.108 | 37.136.322 | 33.569.155 |

| Factor VIIa | IU | 1.463.400 | 1.463.400 | 1.248.000 | 1.107.000 | 1.227.000 | 978.600 |

| Factor VIIa rec. NiaStase® | mg | 25.483 | 25.483 | 30.502 | 30.686 | 34.124 | 33.740 |

| Porcine FVIII | IU | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 249.340 |

| Recombinant Factor VIII | IU | 178.234.199 | 178.234.199 | 178.792.631 | 164.791.696 | 155.487.497 | 144.129.307 |

| Factor VIII/VWF | IU | 28.730.716 | 28.730.716 | 26.711.363 | 24.364.514 | 20.701.440 | 18.620.052 |

| Factor XI | IU | 35.890 | 35.890 | 51.275 | 74.455 | 64.575 | 85.705 |

| Factor XIII | IU | 559.000 | 559.000 | 533.000 | 471.750 | 522.000 | 444.250 |

| Fibrinogen | g | 542 | 542 | 933 | 390 | 1.188 | 901 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of Haemophilia Treatment Centers across Canada

The standard of care for haemophilia in Canada

A functional, efficient, and accountable system of haemophilia care has been developed in Canada mostly at the initiative of the comprehensive care centers, without acting official mandates. However, several Canadian provinces have since designated provincial haemophilia programs in specific centres (e.g. British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec). The existing system is thus an eloquent testimony to the goodwill and constructive collaboration among patients and their families, health care providers and funders. The idea that a national standard of care for haemophilia be developed for Canada was first promulgated in the conference “Comprehensive Care for the Canadian Haemophiliac”, Winnipeg, May 1978, organised by the Canadian Haemophilia Society (CHS) in close collaboration with its own multi-disciplinary Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee (MSAC).

To analyze the scope of the initiative, we will refer to the definition given in 1998 in the Standards for comprehensive care of haemophilia in Canada, agreed upon during a “second” Winnipeg conference, on April 30 – May 1, 1998.

The Association of Haemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada (AHCDC) and the CHS felt that national standards of care for haemophilia should be developed for the following reasons:

to preserve the integrity of the network of Haemophilia Comprehensive Care Programs;

to assure equal access and equal standards of care;

to establish a reference for discussion of future advances and needs;

to be a reference point and unifying force for staff of various organizations that are geographically dispersed and serve a small population;

to promote discussion and research regarding optimal ways to deliver care; and

to provide the basis for the design of clinics, for accreditation, and for audit and evaluation.

At its Annual General Meeting in Edmonton, the AHCDC appointed a working group on standards of care with two of us (Irwin Walker and Jerome Teitel) as co-chairs. The working group was later expanded to become a multidisciplinary one.

With the aim of developing national standards, a national multidisciplinary committee, including members of the CHS, the Canadian Association of Nurses in Haemophilia Care (CANHC), Canadian Association of Physiotherapists in Haemophilia Care (CAPHC), and the Canadian Social Workers in Haemophilia Care (CSWHC) was initiated to further the initiatives of the AHCDC. The National Standards Committee for Haemophilia Treatment Centres conducted a first conference on April 20, 2005. It was attended by the representatives from the CHS and the AHCDC. An important recommendation from the meeting was that Haemophilia Comprehensive Care should be delivered according to a set of uniform national standards and wherever possible these standards should be needs-based, data-driven and supported by evidence of effectiveness. The meeting also held that generic national standards be developed, but as they would be implemented locally the system must be flexible and adaptable, with the emphasis being the delivery of a uniformly high quality of care.

The meeting also formalised the constitution of a multidisciplinary standards of care working group to develop comprehensive standards of care for haemophilia, led by the AHCDC. All four health care provider groups and CHS were represented in the working group.

Simultaneously, the Ontario clinics were working on provincial standards of care, and they published their document which later became the template for the national standards. This work was spearheaded by the Provincial Haemophilia Coordinator at the time, Julia Sek, and the co-chairs of that group were Jerome Teitel and John Plater. After a series of meetings and deliberations, the first edition of the Canadian Haemophilia Standard of Care was published in 2007 (Canadian Comprehensive Care Standards for Haemophilia and Other Inherited Bleeding Disorders, http://www.haemophilia.ca/en) for use by Haemophilia Treatment Centres, hospital administrations, and provincial Ministries of Health. It has to be acknowledged that this national document was largely based on the Ontario Provincial standards.

The premises of the Canadian comprehensive care standards for haemophilia and other inherited bleeding disorders are that:

- improved quality of life is the ultimate goal of care, with an emphasis on measurable outcomes and independent living;

- inherited bleeding disorders are rare and therefore collaboration among HTCs and networks needs to be encouraged;

- bleeding disorders and their treatments are associated with a number of complications - medical, psychological and social-that may affect quality of life of affected individuals and so care needs to be comprehensive;

- evaluation and documentation of clinical outcomes are essential components of a comprehensive program;

- standards of care are measures that HTCs can adhere to and which can be used for auditing. Key indicators are signals that demonstrate whether a standard has been attained. They provide a way in which to measure and communicate the impact or result of the standard, as well as the process.

- accountability for utilization of factor replacement product is necessary due to its potential to cause adverse events and its high cost; this is equally true for products used in centres and at home in supervised home therapy programmes;

- HTCs have a responsibility to participate in research, education and innovation to the degree that they are capable. Regional differences within the province or region must be acknowledged in the provision of care for people with bleeding disorders.

Future perspective and conclusions

The vision is to provide comprehensive care to all individuals with inherited bleeding disorders, guided by clear standards, facilitated by engagement with stakeholders, and driven by needs and best practice, resulting in best outcomes. The focus of these standards is on the structural and resource requirements necessary for a HTC to effectively provide care, and on its functions and responsibilities.

In 2009 in response to a request from the AHCDC executive, the Standards group initiated a self assessment survey among Canadian Haemophilia Treatment Centers according to the specific standards (Table II, III, IV) and key indicators (see appendix 1) proposed. Standards of care are measures that Haemophilia Treatment Centres can adhere to and which can be used for self-evaluation and auditing. Key indicators are signals that demonstrate whether a standard has been attained. They provide a way in which to measure and communicate the impact or result of the standard, as well as the process. The goal was to validate the Canadian clinic standards by assessing acceptability and adherence. The average adherence by all clinics to all standards was 92% (standards being adhered to by an average of 22 of 24 HTCs). Adherence levels below 83% (20 of 24 HTC) were observed for only 4 standards; for two of these standards the low adherence was due to a lack of core team members, particularly social workers and physiotherapists and possibly administrative staff as well. As indicated by statements from the World Federation of Haemophilia and by the Canadian standards, a lack of any of these team members is particularly serious considering their importance. Lack of complete adherence to other standards was due to a variety of reasons, in most cases either easily explainable or spurious.

Table II.

Standards - 1. Scope of care

The HTC will:

|

Table III.

Standards - 2. Quality Measures1

The HTC will:

|

This section describes expected activities of an HTC that contribute to the quality of both the individual centre and the Canadian HTC network.

Table IV.

Standards - 3. Therapeutic Services1

The HTC will:

|

This section describes the actions required of an HTC in the direct delivery of therapeutic services.

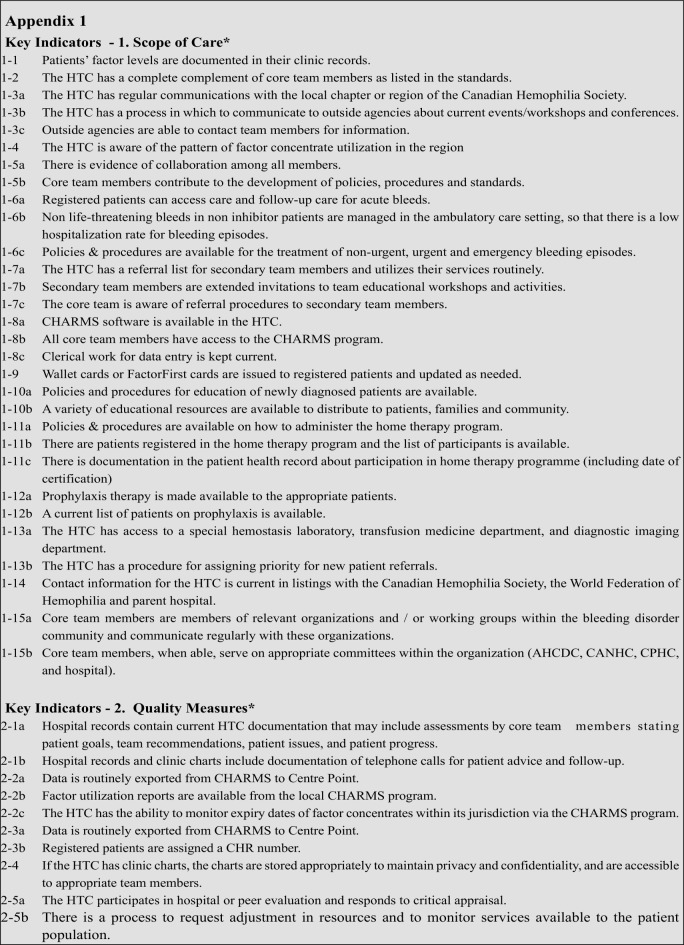

Appendix 1.

No correlation was found between the level of adherence to the standards and any one of a variety of HTC descriptors. The general level of acceptability of the standards was high; most clinics (20 of 24, 83%) thought the standards were useful and 22 of 24 clinics (92%) expressed their willingness to participate in evaluation and accreditation processes once these are established.

To fulfill the proposed standards of care a full audit process, modeled on the Ireland and UK experience, has been planned by the AHCHC-led Canadian Haemophilia Standards Group, but has been slowed down by unexpected privacy issues encountered early in the process.

Complementarily to this process, and in order to gather information that can be used to advocate for adequate resources in clinics, a CHS task force led by Past-President, Pam Wilton, has developed a Haemophilia/Bleeding Disorder Clinic evaluation process to be led by CHS to roll out in 2013. The proposed process, which is supported by the Executive Committee of the AHCDC, consists of an assessment of the services and resources in Haemophilia/Bleeding Disorder Clinics through interviews with clinic personnel and a patient questionnaire. This survey is evaluating the adequacy of the physical, material and human resources in Canada’s 24 HTC. The overall goal is to identify any gaps in resources that may prevent Haemophilia/Bleeding Disorder Clinics from delivering care and treatment according to the Canadian Comprehensive Care Standards for Haemophilia and Other Inherited Bleeding Disorders and that may lead to sub-optimal patient outcomes (see Table I, II, III).

The primary objectives are:

- to conduct a thorough assessment of the services and resources in Haemophilia/Bleeding Disorder Clinics in each province;

- to prepare a detailed report and recommendations for hospital administrators and/or Ministry of Health officials in each province;

- to identify and meet key decision-makers in each province with the goal of maintaining and improving the care for people with inherited bleeding disorders;

- to follow up support implementation of recommendations.

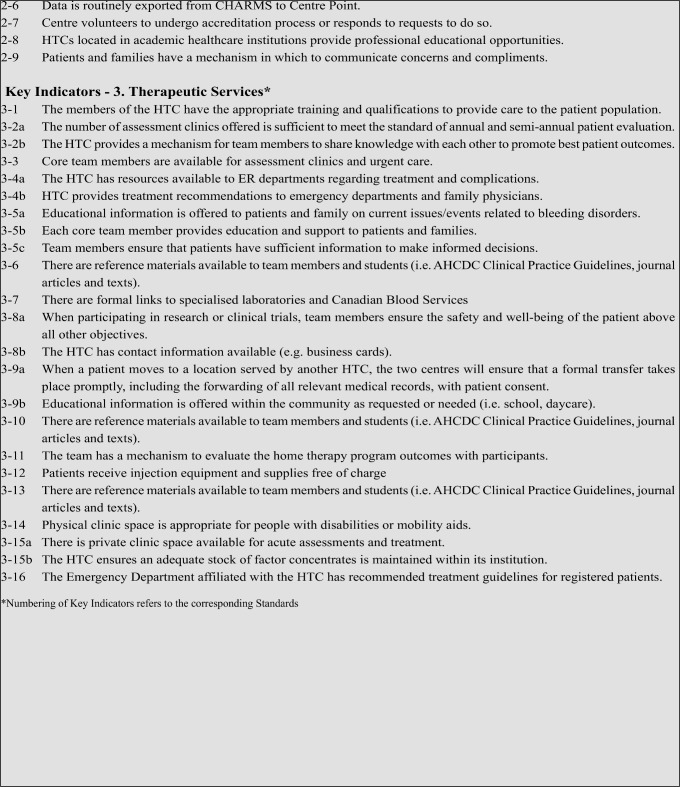

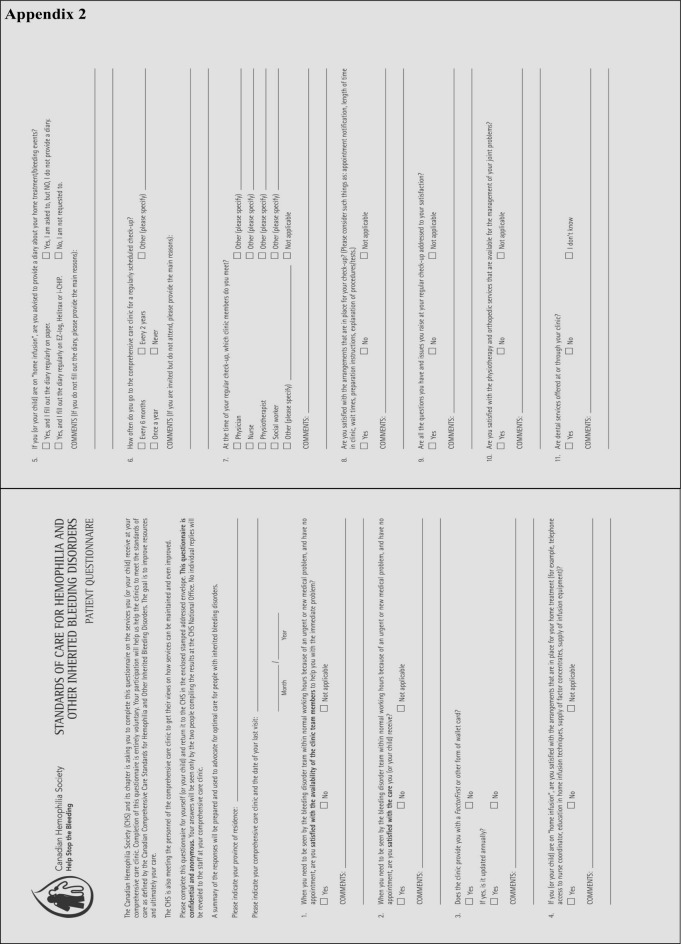

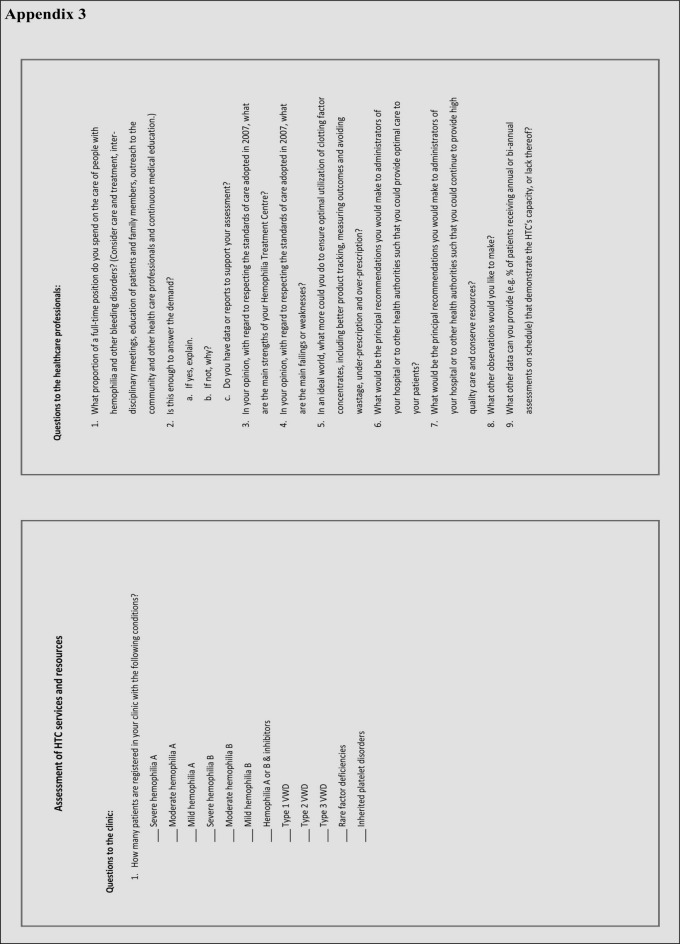

Interviews with clinic personnel and patient questionnaires (see appendix 2, 3) are used in the evaluation.

Appendix 2.

Appendix 3.

The process is based on a successful initiative by the Quebec Chapter of the CHS. Study interviewers met all 37 clinic personnel across Quebec in half-hour meetings. These face-to-face interviews are preferred to a written survey to allow dialogue and clarification of responses. The resulting report is validated by the clinic directors and recommendations are made to the Ministry of Health. The same approach will be applied to all clinics across Canada.

To promote a consistent approach, the interviews are conducted by David Page, CHS National Executive Director, and Michel Long, CHS National Program Manager and, in Ontario, Sarah Crymble, Haemophilia Provincial Coordinator. The patient questionnaire was originally developed for the Irish and U.K. HTC audits, and has been modified by the group preparing the Canadian audit.

The observations, based on the clinic interviews and patient questionnaires, will be assembled in a draft report by the CHS National Office for each clinic and then shared first with the clinic director. Once vetted and approved by the clinic director a final report will be shared with the local chapter Board of Directors. Then, if necessary, a strategy will be developed to approach the appropriate health authorities - hospital administration, regional health authority of Ministry of Health - with a proposal to better meet the standards of care. Up to now, most of the Ontario assessments have been concluded and the visits in Western Canada have been scheduled for winter 2014. We expect that by the end of April 2014 the visits will be completed. Patient questionnaires are actively being distributed by Centres and responses are being received.

In summary, the process of haemophilia centre accreditation in Canada was born with the cooperation of patients and doctors. It will serve as the model to standardize and, where necessary, to improve the care of Canadian haemophilia patients. There is no “end” to such a process. In our opinion, many important results have been achieved, and several important lessons can be learned. As well, we are sure that interesting and actionable results will stem from the ongoing process.

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kumar R, Carcao M. Inherited abnormalities of coagulation: haemophilia, von Willebrand disease, and beyond. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60:1419–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lillicrap D. vonWillebrand disease: advances in pathogenetic understanding, diagnosis, and therapy. Blood. 2013;122:3735–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-498303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darby SC, Kan SW, Spooner RJ, et al. Mortality rates, life expectancy, and causes of death in people with haemophilia A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood. 2007;110:815–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tagliaferri A, Rivolta GF, Iorio A, et al. Mortality and causes of death in Italian persons with haemophilia, 1990–2007. Haemophilia. 2010;16:437–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2009.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker IR, Julian JA and Association of Haemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada. Causes of death in Canadians with haemophilia, 1980–1995. Haemophilia. 1998;4:714–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.1998.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannucci PM. Treatment of haemophilia: building on strength in the third millennium. Haemophilia. 2011;17(Suppl 3):1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2011.02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blood safety monitoring among persons with bleeding disorders-United States, May 1998–June 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;51:1152–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iorio A, Marchesini E, Marcucci M, Stobart K, Chan AK. Clotting factor concentrates given to prevent bleeding and bleeding-related complications in people with haemophilia A or B. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;(9):CD003429. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003429.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iorio A, Matino D, D’Amico R, Makris M. Recombinant Factor VIIa concentrate versus plasma derived concentrates for the treatment of acute bleeding episodes in people with haemophilia and inhibitors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Aug 4;(8):CD004449. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004449.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hay CR, Di Michele DM. The principal results of the International Immune Tolerance Study: a randomized dose comparison. Blood. 2012;119:1335–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-369132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]