Abstract

Background

Stress is a well-documented factor in the development of addiction. However, no longitudinal studies to date have assessed the role of stress in mediating the development of substance use disorders (SUD). Our previous results have demonstrated that a measure called Transmissible Liability Index (TLI) assessed during pre-adolescent years serves a significant predictor of risk for substance use disorder among young adults. However, it remains unclear whether life stress mediates the relationship between TLI and SUD, or whether stress predicts SUD.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal study involving 191 male subjects to assess whether life stress mediates the relationship between TLI as assessed at age 10–12 and subsequent development of SUD at age 22, after controlling for other relevant factors.

Results

Logistic regression demonstrated that the development of SUD at age 22 was associated with stress at age 19. A path analysis demonstrated that stress at age 19 significantly predicted SUD at age 22. However, stress did not mediate the relationship between the TLI assessed at age 10–12 and SUD in young adulthood.

Conclusions and scientific significance

These findings confirm that stress plays a role in the development of SUD, but also shows that stress does not mediate the development of SUD. Further studies are warranted to clarify the role of stress in the etiology of SUD.

Keywords: Stress, substance use disorders, youth

Introduction

Stress is a well-documented factor in the development of addiction (1,2). A recent review by Zucker and colleagues (3) listed several other factors that have also been reported to be associated with the development of substance use disorders (SUD), such as antisocial comorbidity in a parent, involvement with deviant peers, poor parenting, exposure to abuse or conflict, low social competence in early childhood, or early use of substances. The conclusions of that review are consistent with our own findings concerning factors associated with the development of SUD (4–7). However, no longitudinal studies to date have assessed the role of stress in mediating or moderating the development of substance use disorders among adolescents making the transition to young adulthood. The few studies of this area which have been conducted to date have been limited by their use of a cross-sectional rather than longitudinal study design.

Our own research group has been conducting a large longitudinal study of the development of SUDs and related phenomena among subjects as they make the transition from preadolescence to adulthood. This study has focused on the role of transmissible liability which quantifies risk for substance use disorder (TLI) (8), which serves as a continuous measure of behavioral undercontrol (9), utilizing a measure called the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI). Transmissible liability can be defined as risk for SUD encompassing both genetic and environmental components shared between parents and the offspring. Our previous results have demonstrated that TLI assessed during pre-adolescent years serves a significant predictor of measuring risk for cannabis use disorder among young adults (8). However, it remains unclear whether life stress mediates that relationship, or whether stress predicts SUD. Mediation can be defined as a hypothesized causal chain in which an intervening variable serves as a mediator between the predictor and an outcome variable (such as the development of SUD). Information concerning mediation could potentially facilitate targeted early interventions for stress, which might in turn decrease the development of SUD.

The current longitudinal study assessed whether life stress mediates the relationship between TLI as assessed at age 10–12 and subsequent development of SUD, after controlling for other relevant factors (7,8,10,11). We hypothesized that stress would mediate the development of SUD.

Methods

The subjects in this ongoing study were male offspring of men with a lifetime history of a SUD (SUD + probands, n = 250, called the HAR group) and men with no lifetime history of a SUD (SUD – probands, n = 250, called the LAR group). These subjects had been recruited for participation in a longitudinal project designed to elucidate the etiology of SUD, which was conducted at the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research (CEDAR). Probands were considered to have a lifetime history of SUDs if they met DSM-III-R dependence or abuse criteria for any substance other than nicotine, caffeine, or alcohol. The participants were initially recruited when they were 10–12 years of age, and subsequent assessments were conducted at age 12–14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, and then annually until age 30. Stress was measured as the sum of two groups of stress-related subscale scores (“Challenging-Uncontaminated Composite” score and “Negative Outcome Composite” score) on the Life Events Questionnaire (LEQ). Path analysis (mediation analyses) was used to assess whether life stress assessed at age 19 mediates the relationship between TLI and SUD at age 22. Among the covariates included in the analyses is a measure of heritable liability to substance use disorders developed at CEDAR, known as the Transmissible Liability Index, or TLI, measured at study entry.

Data collection and procedures

The subjects in this study were part of a longitudinal research study examining the etiology of SUD in families, known as the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research, or CEDAR. The children were recruited through their biological fathers and initially assessed in late childhood at ages 10 through 12 years of age. The recruitment procedure was designed to yield a group of children at high average risk for SUD, identified by having fathers with a lifetime history of drug use disorders (abuse or dependence involving illicit substances) and a comparison group at low average risk, identified by having fathers without SUD or other major mental disorders. Fathers were the focus of recruitment rather than mothers because of the higher rate of SUD among the fathers. Also, the TLI has been shown to have 80% heritability when it was focused on the fathers (12), and in a family study predicted SUD outcome by age 19 with 68% accuracy (8). Fathers were considered to have a SUD if they ever met DSM-III-R criteria for abuse or dependence involving substances other than nicotine, caffeine, or alcohol, Diagnoses were made according to DSM-III-R, the most recent DSM edition when the study was initiated.

Multiple recruitment sources were used to minimize bias that could potentially occur if all of the subjects were recruited from one source. Approximately 89% of the families were recruited from the community through public service announcements and advertisements as well as by direct telephone contact conducted by a market research firm, and 11% were recruited from clinical sources (7,13). Psychosis, mental retardation, and neurological injury were exclusionary criteria for participation of the family. Prior to participation in the study, written informed consent was obtained from husbands and wives, and assent was obtained from offspring. The offspring were the focus of the current study. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The subjects were recruited at age 10–12, and subsequent evaluations were conducted at ages 12–14, 16, 19, and 22, which covered the peak years for initiation of cannabis use disorders and other SUD. Overall attrition rate from baseline assessment to age 22 assessment was 39% (14).

Measures

Diagnostic evaluation was conducted with an expanded version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (15), which was the most recent DSM edition when the study was initiated. Offspring psychopathology was assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E) (16). The onset date of each diagnosis was determined to the nearest month. Each family member was individually administered the research protocol in a private room by a different clinical associate. The diagnostic interviews were documented by a staff of experienced clinical associates. Training the clinical associates involved observation of several interviews and conducting joint interviews in the presence of an experienced interviewer. The training procedures were found to produce inter-rater reliabilities exceeding 0.80 for all major diagnostic categories. Diagnoses were determined in a consensus conference using the best estimate diagnostic procedure (17). The diagnostic data, in conjunction with all available pertinent medical records and social and legal history, were reviewed in a clinical case conference chaired by a board-certified psychiatrist and another psychiatrist or psychologist and the clinical associates who conducted the interviews. Stress was measured as the sum of two groups of stress-related subscale scores (“Challenging-Uncontaminated Composite” score and “Negative Outcome Composite” score) on the Life Events Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (LEQ) (18). The Challenging Uncontaminated Composite score was designed to assess stress in which the person has no control, i.e. “my parents got divorced”, and the Negative Outcome Composite score was designed to assess stress associated with the subject’s own behavior (including drug use behaviors), i.e. “I got in trouble with the law”. The LEQ is a widely-used measure that has demonstrated good reliability and validity for assessing presumptive stress associated with life events (19). Additional information concerning the assessments and the validity of those assessment instruments has been provided elsewhere (20–22).

Data analysis

Based on the concept of common transmissible liability to SUD, the transmissible liability index (TLI) has been developed at the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research (CEDAR) and has been utilized in this project. TLI has been shown to be a significant predictor of SUD (8). The TLI is a method enabling quantification of this latent trait utilizing high risk design for a SUD and item response theory. The rationale and method of deriving the TLI have been described in prior reports (8,9,23,24). The construction of the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI) was a multi-stage process. First, items were selected from psychological and psychiatric questionnaires and aggregated into conceptual domains. Emphasis in item selection focused on characteristics indicating deficient psychological self-regulation spanning cognitive, emotion, and behavior domains of measurement. After the selection of the initial pool of items was completed, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis conducted. Constructs reflecting the measurement domains that distinguished offspring of father with and without substance use disorders (indicating transmissible SUD liability) were retained. Next, the constructs were submitted to confirmatory factor analysis to ensure unidimensionality of the index. Lastly, item response theory (IRT) analysis was performed to calibrate the items (determine item discrimination and threshold parameters). The TLI derived in this fashion thus contained the fewest and most robust items, accounting for 26% of item variance and having internal reliability of 0.87 (8).

Logistic regression analyses (8,25) were conducted to determine whether stress at age 19 predicted SUD at age 22, after allowing for the effects of deviant peers, TLI, and demographic factors. A path analysis was conducted to assess mediation effects and moderation effects associated with TLI, after allowing for factors such as demographic variables and socioeconomic status (SES) (26). Mediated paths were tested using the method described by Sobel (27), as updated by Mackinnon (28). Path analyses using that method have been found to be a productive method of assessing mediated paths in our previous work involving adolescent substance use disorders (8,29). ROC analyses were performed to assess the extent to which stress discriminated between those who developed SUD versus those who did not develop SUD (30). Other variables included in the ROC analyses included socioeconomic status, TLI, and DUSI Drug Use Chart current drug use at age 19.

Results

The sample included 500 males, which included 72.8% white, 24.6% black, and 2.6% other subjects. The high risk group (HAR) had lower SES (p <0.001) and a higher percentage of African Americans than the low risk group (LAR) (p <0.001) (Table 1). Consequently, demographic variables were included in outcome analyses. The mean age upon entry into the study was 11.19 ± 0.90 years. The mean TLI measured at baseline was 0.13 ± 0.88. The mean socioeconomic status was 40.83 ± 13.25. The mean stress level at age 19 was 4.33 ± 4.00 of a possible 54 items (range 0–26). By the age 22 assessment, 35% of the subjects had been diagnosed with a SUD. A comparison of those who were retained throughout the course of the study versus those who attrited is provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of high risk (HAR) and low risk (LAR) sample.

| HAR (n = 250) | LAR (n = 250) | F | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 71.6 | 79.6 | 5.87 | 0.05 |

| Black | 25.6 | 16.8 | ||

| Other | 2.8 | 3.6 | ||

| SES (M, SD) | 37.64 (12.22) | 44.00 (13.58) | 30.37 | 0.001 |

SES, socioeconomic status.

Table 2.

Comparison of retained and attrited segment of the sample.

| Attrited (n = 199) | Retained (n = 301) | F | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 74.4 | 76.4 | 0.79 | 0.67 |

| Black | 21.6 | 20.9 | ||

| Other | 4.0 | 2.7 | ||

| SES (M, SD) | 39.18 (12.80) | 41.90 (13.52) | 5.07 | 0.03 |

SES, socioeconomic status.

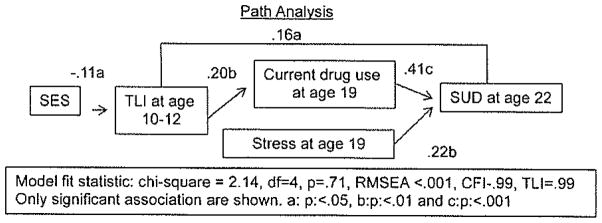

First, logistic regression analysis was conducted, which demonstrated that the development of SUD at age 22 was associated with stress at age 19 (OR = 2.10, p = 0.004, 95% CI 1.26, 3.50). Next, a path analysis was conducted, which demonstrated a good model fit statistic: Chi-square = 2.14, df = 4, p = 0.71, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) <0.0001, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) = 0.99, TLI = 0.99. Stress at age 19 significantly predicted SUD at age 22 (b = 0.22, p <0.05); however, stress did not mediate the relationship between the TLI assessed at age 10–12 and SUD at age 22, as is demonstrated in Figure 1. In contrast, TLI did significantly predict the subsequent development of SUD. Drug use at age 19 mediated the association between TLI at age 10–12 and SUD at age 22 (b = 0.08, p <0.01). Only significant associations are shown on that Figure.

Figure 1.

Model fit statistic: Chi-square = 2.14, df = 4, p = 0.71, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) <0.001, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI) = 0.99, Transmissible Liability Index (TLI) = 0.99. Only significant associations are shown. (a) p <0.05, (b) p <0.01 and (c) p <0.001. SES, socioeconomic status; SUD, substance use disorder.

Finally, ROC analyses were conducted, which demonstrated similar findings for the two different measures of stress, including stress in which the person has no control and stress as the result of the subject’s own behavior (including drug-taking stress). Specifically, the Challenging Uncontaminated Composite score provided an overall correct classification = area under the curve = 0.82, sensitivity = 0.85, and specificity = 0.68, while the Negative Outcome Composite score yielded an overall correct classification = area under the curve = 0.82, sensitivity = 0.83, and specificity = 0.71. The area under the curve = 0.82 values for both measures of stress is considered to be in the “good” range (0.80–0.90) for distinguishing outcomes (30), including outcomes such as SUD versus not-SUD on the basis of stress.

Discussion

These findings of this longitudinal study suggest that stress at age 19 predicts SUD at age 22 among teenagers making the transition to young adulthood beyond the effects of TLI and demographic factors. However, the findings of this study do not support the hypothesis that stress mediates the relationship between TLI (risk for SUD) and SUD. Thus, the hypothesis of the study was not confirmed. These findings confirm the role of stress as an important factor in the development of SUD. These findings also suggest that the effects of TLI at age 10–12 and of stress on the development on SUD are relatively independent of each other. Thus, stress appears to play a role in the development of SUD, because stress predicts SUD. However, the nature of that role remains unclear, because stress does not mediate the development of SUD. Further studies are warranted to clarify the role of stress in the etiology of SUD.

There are limitations to our research design that should be noted when interpreting our findings. First, the sample was not a random sample from across the United States, so the results may not generalize to the United States as a whole. Also, the study sample was primarily male, so the results of the study may not generalize to women. In addition, stress and was measured by a check-list, without confirmation from other data. Furthermore, no biological confirmation of substance use was performed. However, this study had the methodological advantage of being a longitudinal study, while most studies of SUD have been cross-sectional studies or brief longitudinal studies. Future studies are warranted to clarify the etiology, the optimal treatment modalities, and the optimal treatment utilization patterns for adolescents and young adults with cannabis use disorders and other SUD (23,24,31). For example, future etiology studies are warranted to longitudinally study the separate behaviors assessed in the TLI. The results of those future etiology studies and treatment outcome studies will have important implications for health professionals, clinicians, and treatment consumers. Furthermore, in the current era of health care reform in the United States, studies are warranted to translate research findings among adolescents and young adults into public policy, in order to maximize the effectiveness of treatment provided for SUD (32).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 DA05605, R01 DA019142, R01 DA14635, K02 DA017822, K05 DA031248, and the NIDA Clinical Trials Network); from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA013370, R01 AA015173, R01 AA14357, R01 AA13397, K24 AA15320, and K02 AA000291).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady KT, Sinha R. Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders: the neurobilogical effects of chronic stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1483–1493. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol-disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: a multilevel developmental problem. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark DB, Cornelius J, Vanyukov M. Childhood antisocial behavior and adolescent alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res Health. 2002;26:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark DB, Cornelius JR, Wood DS, Vanyukov ME. Psychopathology risk transmission in children of parents with substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:685–691. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark DB, Cornelius MS, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Childhood risk categories for adolescent substance involvement: a general liability typology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Reynolds M, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Early age of first sexual intercourse and affiliation with deviant peers predict development of SUD: a prospective longitudinal study. Addictive Behav. 2007;32:850–854. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Mezzich A, Ridenour T, Reynolds M, Vanukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between boyhood and young adulthood: clarifying the phenotype and environtype. Am J Addictions. 2009;18:36–47. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridenour TA, Kirisci L, Tarter R, Vanyukov MM. Could a continuous measure of individual transmissible risk be useful in clinical assessment of substance use disorder?: Findings from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.018. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB, Hayes J, Tarter R. PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornelius JR, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, Fabrega H, Haas GL, Jones-Barlock A, Mezzich JE, Ulrich RF. Gender effects on the clinical presentation of alcoholics at a psychiatric hospital. Comprehen Psychiat. 1996;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Moss L, Tarter RE, Reynolds MD, Maher BS, Kirillova GP, et al. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders: phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behav Genet. 2009;39:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornelius JR, Reynolds M, Martz BM, Clark DB, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Premature mortality among males with substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2008;33:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirisci, et al. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID, 4/1/87 revision) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. J Am Acad Child Psych. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosten TA, Rounsaville BJ. Sensitivity of psychiatric diagnosis based on the best estimate procedure. Am J Psych. 1992;149:1225–1227. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coddington RD. The significance of life events as etiologic factors in the diseases of children-I. J Psychosomat Res. 1972;16:205–213. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(72)90045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coddington RD. Coddington Life Events Scales (CLES) In: Rush AJ Jr, First MB, Blacker D, editors. Handbook of psychiatric measures. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008. pp. 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanyukov MM, Neale MC, Moss HB, Tarter RE. Mating assortment and the liability to substance abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark DB, Pollock NK, Mezzich A, Cornelius J, Martin C. Diachronic assessment and the emergence of substance use disorders. J Child Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;10:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB, Hayes J, Tarter R. PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Addict Behav. 2010;35:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Simkevitz HF, Kirillova GP, Maher BS, Clark DB. Liability to substance use disorders: 2. A measurement approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Kirillova GP, Maher BS, Clark DB. Liability to substance use disorders: common mechanisms and manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dohrenwend B, Levav I, Shrout P, Schwartz S, Naveh G, Link B, Skodal A, Steuve A. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorder. The causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;225:946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobell MD. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Reynolds M, Habeych M. Relation between cognitive distortions and neurobehavior disinhibition on the development of substance use during adolescence and substance use disorder by young adulthood: a prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fawcett T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2006;27:861–874. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Substance Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornelius JR, Clark DB. Translational research involving adolescent substance abuse. In: Miller P, Kavanagh D, editors. Chapter 16, in Translation of addictions science into practice: update and future directions. New York, NY: Elsevier Press; 2007. pp. 341–360. [Google Scholar]