Maize plants with significantly reduced carbonic anhydrase activity have impaired growth at subambient CO2, but photosynthesis in these plants is not limited under current atmospheric conditions.

Abstract

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) catalyzes the first biochemical step of the carbon-concentrating mechanism of C4 plants, and in C4 monocots it has been suggested that CA activity is near limiting for photosynthesis. Here, we test this hypothesis through the characterization of transposon-induced mutant alleles of Ca1 and Ca2 in maize (Zea mays). These two isoforms account for more than 85% of the CA transcript pool. A significant change in isotopic discrimination is observed in mutant plants, which have as little as 3% of wild-type CA activity, but surprisingly, photosynthesis is not reduced under current or elevated CO2 partial pressure (pCO2). However, growth and rates of photosynthesis under subambient pCO2 are significantly impaired in the mutants. These findings suggest that, while CA is not limiting for C4 photosynthesis in maize at current pCO2, it likely maintains high rates of photosynthesis when CO2 availability is reduced. Current atmospheric CO2 levels now exceed 400 ppm (approximately 40.53 Pa) and contrast with the low-pCO2 conditions under which C4 plants expanded their range approximately 10 million years ago, when the global atmospheric CO2 was below 300 ppm (approximately 30.4 Pa). Thus, as CO2 levels continue to rise, selective pressures for high levels of CA may be limited to arid climates where stomatal closure reduces CO2 availability to the leaf.

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) catalyzes the reversible hydration of CO2 into bicarbonate (Badger and Price, 1994; Moroney et al., 2001), and multiple independently evolved families of CA are found across all kingdoms of life (Hewett-Emmett and Tashian, 1996). In land plants, the β-CAs are most abundant and have been implicated in photosynthesis (Ludwig, 2012). In photosynthetic bacteria (Fukuzawa et al., 1992; So et al., 2002; Dou et al., 2008) and green algae (Funke et al., 1997; Moroney et al., 2011), CA plays an essential role in providing CO2 to the active site of Rubisco. However, the role of CA in C3 plants is less clear (Badger and Price, 1994), because it does not appear to limit photosynthesis but does affect stomatal conductance and guard cell movement (Hu et al., 2010). In C4 plants, CA provides HCO3− to the initial carboxylating enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), driving the production of the C4 acid oxaloacetic acid. The total amount of leaf CA activity varies significantly across evolutionary lineages of C4 plants (Gillon and Yakir, 2001; Cousins et al., 2008); however, there is little evidence to support a physiological role for this large natural variation in CA activity. This suggests that the importance of CA activity across C4 plants may vary and may be related to the C4 evolutionary linage or the specific environment to which a particular species has adapted.

In the C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis, which has very high leaf CA activity, the cytosolic β-CA is essential but not rate limiting for C4 photosynthesis (von Caemmerer et al., 2004). In antisense F. bidentis with less than 20% of wild-type leaf CA activity, rates of photosynthesis were reduced, and plants with less than 10% of wild-type CA required high CO2 (1–2 kPa) for growth. Alternatively, in many C4 grasses, CA activity appears to almost limit the rates of photosynthesis (Hatch and Burnell, 1990; Cousins et al., 2008). For example, CA activity in maize (Zea mays) leaves is approximately 10% of that in wild-type F. bidentis (Cousins et al., 2008); however, both species have high rates of CO2 assimilation typical of C4 photosynthesis. While the requirement of CA for C4 photosynthesis may differ between independent evolutionary C4 lineages, to date, a mutant analysis has not been performed to examine the role of CA on C4 photosynthesis in any monocot species.

Therefore, we used a mutational approach to test the role of CA activity in the C4 monocot maize, which contains five annotated genes encoding β-CAs within its genome. Two homologs (Chr.2-GRMZM2G414528 and Chr.7-GRMZM2G145101) are predicted to be localized to mitochondria and are structurally conserved across grass species as single orthologs. A gene encoding β-CA on chromosome 8 (GRMZM2G094165) is a duplicated homolog unique to maize and is predicted to be chloroplast localized. Two annotated β-CAs (GRMZM2G121878 and GRMZM2G348512) are arranged as tandem duplicates on chromosome 3. The gene annotated as GRMZM2G121878 is conserved across all grass species (Ca1) and is the first gene in the tandem gene set. Although GRMZM2G348512 is annotated as a single gene in maize, RACE mapped two separate genes (sequentially Ca2 and Ca3). Thus, the tandem Ca locus is composed of three genes in maize (Ca1–Ca3) and is reported as four genes in Sorghum bicolor (Wang et al., 2009) and three in Setaria italica (Zhang et al., 2012).

The detailed genetic characterization of the Ca loci in maize allows for a directed targeting of the genes most likely involved in the first step of C4 photosynthesis. Here, we present, to our knowledge, the first mutagenesis and physiological characterization of ca mutants in a C4 monocot to determine whether CA is rate limiting for photosynthesis in a C4 monocot. The low CA activity observed in maize leaves, despite the numerous genes encoding CA, provides a test for the requirement of CA for C4 photosynthesis in a species with naturally low levels of CA. We show that CA1 accounts for the majority of the leaf CA activity. We also show that, under low-CO2 conditions, photosynthetic rates are compromised. In addition, photosynthetic isotope discrimination shows that the uncatalyzed hydration of CO2 contributes significantly to bicarbonate pools in the double mutant, which has only 3% of wild-type CA activity. The data presented demonstrate that CA is not rate limiting for C4 photosynthesis in maize under current atmospheric conditions. In addition, the interplay between stomatal and biochemical limitations for photosynthesis under different environmental conditions is discussed.

RESULTS

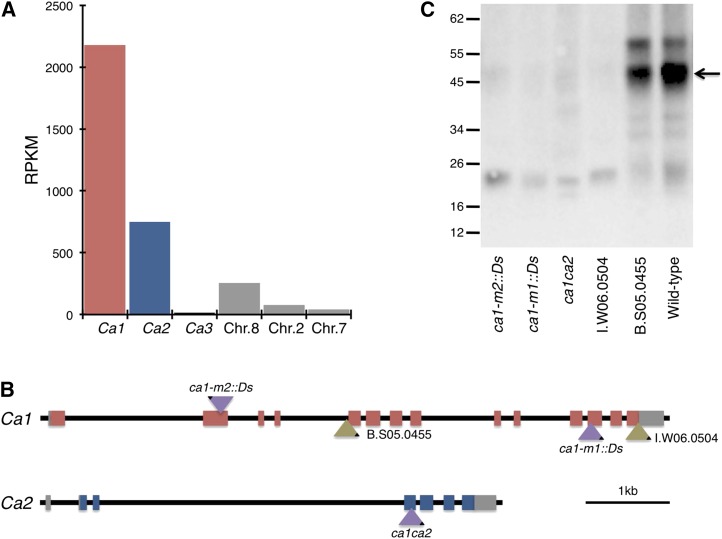

Two Highly Expressed Ca Genes Are Correlated with C4 Photosynthesis

The resolved Ca gene structures in maize, described above, were used with RNA-seq data from deeply sequenced maize leaf tissue to examine the expression level of each Ca gene (Fig. 1A). Unlike most RNA-seq pipelines that permit multiple mapped alignments, a stringent filter was applied (see “Materials and Methods”) so that only unique reads were aligned to a region of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of each Ca gene. This enables the expression profile of each Ca gene to be assayed independently, despite the high level of sequence homology within the gene family. At the tip of the developing seedling leaf (which is photosynthetically active; for a description of leaf gradient used, see Li et al., 2010), Ca1 and Ca2 encode more than 85% of the Ca transcript pool. However, Ca3 is expressed at very low levels (less than 0.5% of total reads mapped) in the leaf, indicating that it is a paralogous duplication. This result is confirmed by the available maize expression atlas data (Sekhon et al., 2011), which shows Ca3 expression mostly in nonphotosynthetic tissues (Supplemental Fig. S1). Given these results, we restricted our genetic characterization to the tandemly arranged Ca1 and Ca2 genes.

Figure 1.

Ds insertional mutants disrupt the two most highly expressed Ca genes. A, Unique RNA-seq reads from the tip of the third leaf of a maize seedling were mapped to the 3′ UTR of each Ca gene to quantify the expression of each member of the gene family (for a description of RNA-seq read mapping, see “Materials and Methods”). RPKM, Reads per kilobase per million reads. B, Insertional mutagenesis of the tandemly arranged Ca genes on maize chromosome 3. Gene models are drawn to scale. Red and blue boxes represent exons of Ca1 and Ca2, respectively, and gray boxes denote UTRs. Bronze triangles show the positions and orientations of donor Ds elements used to generate the insertion alleles characterized (purple triangles). Black corners of triangles show the promoter proximal ends of the Ds elements. C, Immunoblot of wild-type and Ds lines challenged with an antibody raised against rice CA. The arrow indicates the predominant CA isoform, which is absent in both ca1 single and ca1ca2 double mutants.

Dissociation Transposition Generates Mutant Alleles in Tandemly Arranged Ca Genes

To investigate the role of CA in maize, we conducted an insertional mutagenesis to generate an allelic series of the Ca1 and Ca2 genes. Using the Activator (Ac) and Dissociation (Ds) system (Ahern et al., 2009; Vollbrecht et al., 2010), a reverse-genetic screen was performed using two donor Ds elements (B.S05.0455 and I.W06.0504) located within Ca1 in two near-isogenic W22 inbred lines. We exploited the intrinsic property of Ds to transpose locally (Alleman and Kermicle, 1993) to create tandem mutations in linked Ca genes. Ds was mobilized from Ca1, resulting in intragenic insertion alleles of Ca1 and intergenic insertion alleles in Ca2 (Fig. 1B). The donor Ds B.S05.0455 is located in the fourth intron of Ca1, but CA1 protein accumulated in homozygotes, indicating that the element is spliced efficiently from the mature mRNA (Fig. 1C). When B.S05.0455 was mobilized, an intragenic transposition event was recovered in which the Ds element was duplicated, creating an insertion into exon 12 of Ca1 while retaining a copy at the donor site. This insertion eliminates CA1 protein, creating the loss-of-function ca1 (ca1-m1::Ds) single mutant (Fig. 1C). The donor Ds I.W06.0504 is inserted into the last exon of Ca1, and plants homozygous for this Ds insertion do not accumulate CA1 protein (Fig. 1C). When I.W06.0504 was mobilized, an intragenic transposition event was recovered in which the Ds element inserted into the second exon of Ca1, leaving behind an 8-bp footprint in the last exon of Ca1. Immunoblots indicated that this allele also has no CA1 protein (Fig. 1C), resulting in a second complete loss-of-function ca1 allele (ca1-m2::Ds).

To generate ca1ca2 double mutants, we screened for intergenic transpositions of Ds from line I.W06.0504. One insertion allele was recovered in which the donor Ds inserted into the third exon of Ca2, with a linked 8-bp excision allele in the last exon of Ca1. This 8-bp footprint causes a frame shift that adds 62 amino acids to the end of CA1 and is sufficient to eliminate CA1 protein (Fig. 1C). Therefore, from this intergenic transposition event, a double mutant was recovered (ca1-d1 ca2-m1::Ds, hereafter referred to as ca1ca2). All three insertion alleles were heritable, and plants carrying each allele were backcrossed to the reference line (B73) before characterization.

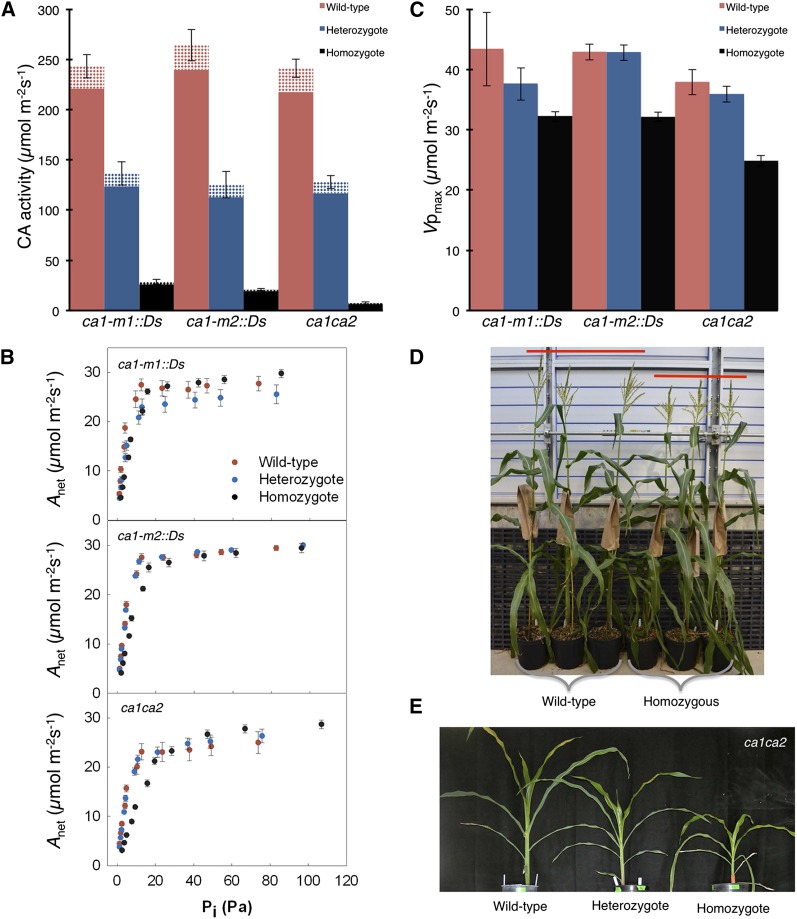

Mutant Plants Have Normal CO2 Assimilation Rates under Ambient CO2 Partial Pressure

The reduction of CA activity in ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants was quantified by total leaf CA activity assays (soluble plus membrane fractions) measured with a membrane inlet mass spectrometer (see “Materials and Methods”). Both ca1 single mutants show similar decreases in CA activity, and although other Ca genes are transcribed, homozygous ca1 mutants had approximately 10% of wild-type CA activity (Fig. 2A). Heterozygous ca1 mutants had intermediate CA activity, demonstrating the additive nature of the mutation and the absence of a compensatory up-regulation of Ca genes in response to reduced total CA (Fig. 1C). Thus, while Ca2 constitutes 22.6% of the leaf transcript pool, CA2 protein is not able to compensate for the decrease in CA activity in either ca1 single mutant. These data indicate that the transcript levels of Ca1 and Ca2 are not directly correlated with the activity levels, suggesting a posttranscriptional regulation of CA. The ca1ca2 double mutant had only 3% of wild-type CA activity (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic measurements predict plant growth phenotypes in CA mutant plants. A, CA activity of CA single and double mutant lines grown under elevated CO2 (928 Pa). Solid and hatched bars show CA activity in the soluble and membrane fractions, respectively. B, Net CO2 assimilation (Anet) in response to changes in intercellular pCO2 (Pi; A-Pi curve) measured at an oxygen partial pressure of 18.6 kPa, leaf temperature of 25°C, and irradiance of 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. C, Maximum in vivo Vpmax estimated from the initial slope of the A-Pi curve and plotted for each CA mutant line. D, Wild-type and homozygous CA double mutant plants grown in the greenhouse at ambient pCO2. E, CA double mutant plants grown at low CO2 (9.3 Pa).

The residual CA activity in the double mutant is likely from anaplerotic CA functioning in the mitochondria, chloroplasts, or bundle sheath cytosol and, therefore, does not significantly contribute to the carbon-concentrating mechanism of C4 photosynthesis. The activities of PEPC and Rubisco were also assayed, but there were no differences between wild-type and mutant plants grown under 928 Pa of CO2 (Table I). Thus, under saturating CO2 conditions, the mutations in Ca1 and Ca2 do not appear to have major secondary effects on the activities of other photosynthetic enzymes or plant growth (Table I). A rate constant of leaf CA of 2.5 mol m−2 s−1 bar−1 in maize was reported previously (Cousins et al., 2008), which corresponds to a CA activity of 88 μmol m−2 s−1 at the CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) used in this study. The CA activity of wild-type plants was approximately 220 to 240 μmol m−2 s−1 in the soluble fraction. Although this activity is 2.6 times higher than the value reported previously, it remains in the range of CA activity measured across C4 lineages (Cousins et al., 2008).

Table I. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of the CA mutants.

| Net Rate of CO2 Assimilationa |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Quantum Yield | Low CO2 (9.3 Pa) | Ambient CO2 (37.2 Pa) | High CO2 (139.5 Pa) | Rubisco Activity | PEPC Activity | Total Leaf Nitrogen | Dry Biomass |

| mol mol−1 | μmol m−2 s−1 | mg g−1 dry wt | g | |||||

| ca1-m1 | ||||||||

| Wild type | 0.027 ± 0.003 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 27.5 ± 1.2 | 27.7 ± 0.5 | 38.9 ± 1.8 | 217.7 ± 30.6 | 52.5 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 0.6 |

| Heterozygote | 0.027 ± 0.001 | 8.3 ± 0.5 | 23.0 ± 1.7 | 25.5 ± 0.3 | 39.8 ± 2.6 | 221.8 ± 29.8 | 50.9 ± 1.8 | 7.6 ± 0.6 |

| Homozygote | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 26.1 ± 0.6 | 29.8 ± 1.0 | 38.9 ± 3.8 | 212.8 ± 23.1 | 54.7 ± 4.3 | 6.8 ± 0.7 |

| ca1-m2 | ||||||||

| Wild type | 0.031 ± 0.001 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 27.6 ± 0.8 | 29.5 ± 1.5 | 38.7 ± 5.2 | 176.0 ± 24.9 | 54.3 ± 1.7 | 7.7 ± 0.2 |

| Heterozygote | 0.034 ± 0.001 | 9.0 ± 0.1 | 26.8 ± 0.6 | 30.1 ± 1.9 | 44.7 ± 4.3 | 196.9 ± 27.2 | 52.0 ± 2.5 | 7.4 ± 1.7 |

| Homozygote | 0.031 ± 0.001 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 25.5 ± 0.9 | 29.5 ± 0.8 | 40.6 ± 3.5 | 199.0 ± 54.4 | 53.0 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 1.2 |

| ca1ca2 | ||||||||

| Wild type | 0.029 ± 0.001 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 1.7 | 25.0 ± 2.2 | 37.3 ± 0.9 | 195.8 ± 34.4 | 48.1 ± 1.0 | 7.7 ± 0.7 |

| Heterozygote | 0.024 ± 0.001 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 21.6 ± 0.9 | 26.3 ± 1.4 | 38.1 ± 1.0 | 180.9 ± 27.4 | 48.2 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.2 |

| Homozygote | 0.029 ± 0.001 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 21.2 ± 0.7 | 28.7 ± 0.9 | 37.4 ± 1.0 | 220.7 ± 15.9 | 53.3 ± 2.1 | 9.9 ± 0.7 |

| ANOVAsb | ||||||||

| Genotype | ns | WTa, HZab, HMb | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Line | ns | m1a, m2a, ca1ca2b | m1ab, m2a, ca1ca2b | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Interaction | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

To assess the physiological consequences of reduced CA activity, the rates of net CO2 assimilation were measured in response to pCO2 (Fig. 2B) and light intensity (Supplemental Fig. S2). Net CO2 assimilation decreased at subambient CO2 levels (9.3 Pa) in both ca1 single mutants and ca1ca2 double mutants compared with the wild type (Table I). Additionally, the in vivo maximal rate of PEPC (Vpmax), estimated from the initial slope of the CO2 response curve, was significantly lower in both ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants compared with the wild type (Fig. 2C). However, no difference in net CO2 assimilation was observed between genotypes at ambient or high pCO2, nor was there a difference in the quantum yield at high CO2 (Table I). This suggests that under ambient and higher pCO2, the amount of HCO3− is sufficient to maintain levels of photosynthesis, but under low pCO2, CA limits photosynthesis. Furthermore, CA mutants grown at elevated CO2 (10,000 ppm, 928 Pa of CO2) showed no difference in aboveground biomass or total leaf nitrogen compared with the wild type (Table I). However, ca1ca2 plants grown at ambient pCO2 in the greenhouse were, on average, 5% (9.6 cm) shorter than wild-type plants (Fig. 2D; n = 3, P = 0.0193). When grown at subambient CO2 (100 ppm, 9.3 Pa of CO2), the dry weight was approximately 20% and 45% lower in single and double mutants, respectively, compared with the wild type (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, under elevated pCO2, there is sufficient conversion of CO2 to HCO3− to maintain rates of net CO2 assimilation; however, under low CO2 availability, additional CA activity is required to maintain high rates of C4 photosynthesis in maize.

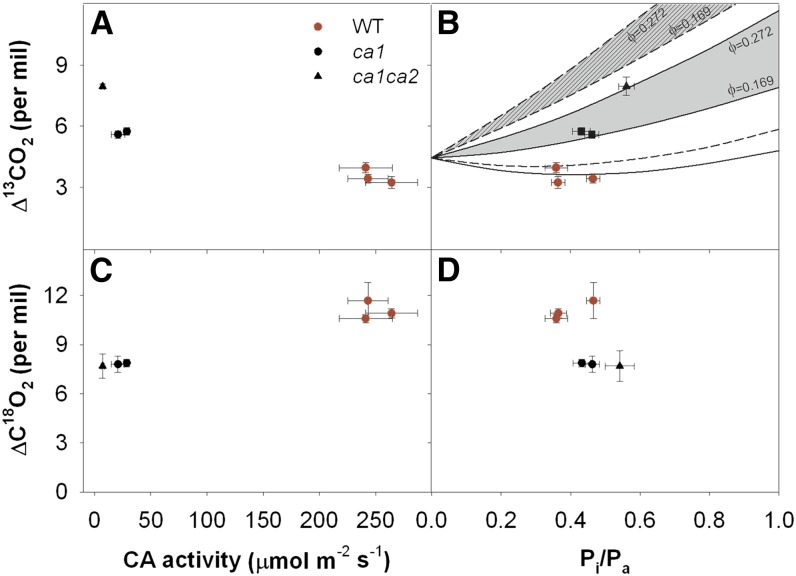

Reduced CA Activity Affects Isotopic Discrimination

The low CA activity is further substantiated by large differences in leaf 13CO2 (∆13C) and C18O2 (∆18O) isotope exchange in high pCO2-grown CA mutants compared with the wild type. The ∆13C increased approximately 2‰ and 4‰ in ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants, respectively (Fig. 3A). The increase in ∆13C with lower CA activity is consistent with previous studies of CA mutants in F. bidentis (Cousins et al., 2006a) and with models of CA activity and ∆13C in C4 plants. Theoretically, the increase in ∆13C measured in the ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants could be explained by either a decrease in the efficiency of the CO2 concentration mechanism (leakiness, the proportion of carbon fixed by PEPC, which subsequently leaks out of the bundle sheath cells) or an increase in the ratio of PEPC to CA activity (Vp/Vh; Farquhar, 1983; Cousins et al., 2006a; Ubierna et al., 2011). However, gas-exchange measurements (Fig. 2, B and C) suggest that leakiness does not increase in the CA mutants but is likely lower than in wild-type plants. For example, comparison of in vivo Vpmax relative to the light-saturated photosynthesis indicates that, despite the delivery of 30% and 38% less CO2 to the bundle sheath cells in ca1 and ca1ca2, respectively, net rates of CO2 assimilation in mutants are comparable with those in the wild type. This suggests that leakiness in the single and double mutants is less than in the wild type and would impart a decreased ∆13C in the mutants.

Figure 3.

Decreased CA activity impacts leaf discrimination against 13CO2 and C18O2 in high-pCO2-grown plants. A and B, Leaf discrimination against 13CO2 (∆13CO2) in relation to CA activity (A) and the ratio of intercellular to ambient pCO2 (Pi/Pa; B). The solid and dashed lines represent the theoretical relationship between ∆13CO2 and Pi/Pa (see Eq. 3) assuming CA-catalyzed hydration or uncatalyzed hydration, respectively, with Vp/Vh = 0 (see Eq. 4). The gray areas delineate theoretical ∆13CO2 assuming Vp/Vh = 1 and a leakiness (ϕ) of 0.272 (calculated from wild-type [WT] plants; top limit) or 0.161 (expected in mutants due to lower Vpmax; bottom limit). Solid and hatched gray areas delineate theoretical ∆13CO2 assuming CA-catalyzed hydration or uncatalyzed hydration, respectively (see Eq. 4). C and D, Photosynthetic discrimination against C18O2 (∆C18O2) in relation to CA activity (C) and the ratio of intercellular to ambient pCO2 (D).

Alternatively, higher Vp/Vh values and uncatalyzed conversion of CO2 to HCO3− will increase ∆13C (Fig. 3B). Assuming that Vp/Vh is near 0 in wild-type plants, the measured ∆13C is effectively modeled with a leakiness of 0.272, which is typical for many C4 grasses (Henderson et al., 1992; Cousins et al., 2008). The measured ∆13C in the ca1 mutants is predicted with a Vp/Vh of 1 (with some CA activity) and leakiness of 70% of the wild type. However, for the ca1ca2 mutants, leakiness is estimated to be approximately 38% of the wild type. In this case, ∆13C is only modeled with a Vp/Vh of 1, and there is a significant nonenzymatic fractionation occurring during the hydration of CO2 to HCO3−. These data confirm that the CA in the ca1 single mutants is just sufficient to supply HCO3− to PEPC. However, in the ca1ca2 double mutant, there is insufficient CA activity and the supply of HCO3− is driven in part by the uncatalyzed reaction. The low CA activity in the ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants also decreased ∆18O by reducing the isotopic equilibrium between CO2 and the isotopically enriched water within the leaf (Fig. 3, C and D), which is consistent with previous observations in F. bidentis CA mutants (Cousins et al., 2006b). These large differences in isotopic discrimination without drastic effects on CO2 assimilation support the hypothesis that ∆13C and ∆18O are sensitive to reduced CA activity in C4 plants. Additionally, the changes in ∆13C and ∆18O further support the hypothesis that leaf-level CA activity is very low in the ca1 and ca1ca2 mutants even though the rates of net CO2 assimilation are not significantly impacted at ambient pCO2.

DISCUSSION

The genetic and physiological analysis of CA mutants in maize presented here provides, to our knowledge, the first genetic analysis of the catalytic requirement of CA in a C4 monocot. Although the lack of a strong CA-deficient phenotype may seem contrary to previous reports that high CA activity is needed to maintain C4 photosynthesis (Hatch and Burnell, 1990), it is important to consider that C4 evolved multiple independent times across monocot and dicot lineages (Sage et al., 2011). Thus, while relatively high CA activity is required for the C4 dicot F. bidentis (von Caemmerer et al., 2004), the independent evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the monocots may have selected an alternative mechanism for providing substrate to PEPC. For instance, C4 species with low CA activity may increase the supply of HCO3− by altering mesophyll conductance to CO2 or increasing the scavenging of HCO3− with higher rates of PEPC activity. Such changes may be sufficient to maintain the flux of carbon through the carbon-concentrating mechanism for C4 photosynthesis. It is also possible that PEPC is either tightly associated with CA or colocalized, thus providing an opportunity for metabolic channeling of substrate to PEPC. Regardless of the mechanisms, our findings indicate that total CA activity in the leaf can be dramatically reduced in maize with little consequence for growth under ambient CO2 conditions. This result is surprising given that maize has one of the lowest CA activity levels measured (Gillon and Yakir, 2001; Cousins et al., 2008). Thus, by perturbing CA activity in maize, we provide evidence for a limited catalytic requirement of CA in this C4 monocot. This result contrasts with observations in a dicot C4 species with high CA activity, and it remains to be seen how broad the findings from maize can be extended to other C4 grasses.

Previous studies in maize have used inhibitors to assess the impact of CA on rates of photosynthesis (Badger and Pfanz, 1995; Salama et al., 2006). By limiting zinc availability, a CA limitation can be imposed, as zinc is required for CA catalysis (Salama et al., 2006). However, zinc deficiency also results in a general reduction in photosynthesis and total protein in chickpea (Cicer arietinum; a C3 plant), suggesting that the pleiotropic effects of zinc deficiency, not specifically CA limitation, are responsible for reduced rates of CO2 fixation. Ethoxyzolamide inhibition of CA activity has also been attempted in leaf peels of maize, resulting in reduced photosynthetic oxygen evolution (Badger and Pfanz, 1995). Interestingly, the authors noted that “the reduction in photosynthesis is less than would be expected from the theoretical requirement for CA” (Badger and Pfanz, 1995), suggesting that the ethoxyzolamide inhibition of CA was inefficient. However, due to the nature of the assay, there are several possible explanations for this result, including a limited requirement for CA to provide substrate to PEPC for photosynthesis. These earlier studies highlight the need for genetic mutants that provide a specific reduction in CA activity, in an otherwise wild-type background, without indirectly inhibiting other aspects of photosynthesis.

The loss-of-function mutants in maize described in this study have extremely low CA activity; however, mutant plants do not have reduced rates of photosynthesis under current atmospheric pCO2. While our results demonstrate that CA does not limit photosynthesis at ambient pCO2, we cannot exclude the possibility for some role in C4 photosynthesis, because the ca1ca2 mutant plants still maintain low levels of CA activity (3% of the wild type) in total leaf extracts. The CA activity in the total leaf extracts of the mutants is predictably greater than zero because of other CAs in different subcellular compartments and in different cell types. α-CAs present in the chloroplasts of mesophyll cells are thought to function in PSII (Lu and Stemler, 2002). In addition, our analysis revealed two β-CAs that are predicted to be mitochondria targeted. Therefore, while the mutants retain a small amount of CA activity, this is consistent with what was observed in F. bidentis CA mutants (von Caemmerer et al., 2004). While it is arguable that a small, highly localized pool of CA would have a low activity when measured on a leaf area basis but could be important for photosynthesis, there is no evidence for such an isoform, and as discussed above, there are other plausible hypotheses for the lack of a photosynthetic phenotype in the maize CA mutants.

Although CA may not be rate limiting for C4 photosynthesis in maize, our data highlight that CA is still important for maintaining high rates of net CO2 assimilation when CO2 delivery into the leaf is reduced. For example, at current pCO2, CA activity in C4 monocots may be limiting when the diffusion of CO2 into the leaf is restricted under environmental stresses such as high temperature and drought. Rates of C4 photosynthesis in the grasses are especially sensitive to stomatal closure because of the inherently low stomatal conductance in these species (von Caemmerer, 2000; von Caemmerer and Furbank, 2003; von Caemmerer et al., 2008). This likely explains why the net CO2 assimilation in response to changes in intercellular pCO2 curves of mutant plants grown under elevated CO2 had normal rates of CO2 assimilation at ambient CO2 levels but ca1ca2 mutants had a mild growth phenotype when grown in pots at ambient pCO2 in the greenhouse, where stomatal limitation is more likely. Because the requirement for CA may depend on stomatal responses, increased levels of CA activity may have a large effect on photosynthetic water use efficiency.

Indeed, a critical role for CA in maintaining photosynthesis under drought may continue to drive selection for CA activity in C4 grasses. Natural variation in CA activity is potentially beneficial for plant breeders who are tasked with improving yield under stress conditions, such as the record drought seen throughout the midwestern United States in 2012. An analysis of CA variation in maize, especially in drought-tolerant varieties, would reveal if selection has already inadvertently been applied for high CA activity in current breeding programs. Regardless, the examination of the role of CA under water stress will be the focus of future experimentation.

In contrast with modern CA requirements, it is likely that high CA activity in the leaf was essential during the Oligocene epoch, when many C4 plants likely arose because of low atmospheric pCO2 (Sage and Coleman, 2001; Edwards et al., 2010; Sage et al., 2012). This is highlighted by the reduction in growth when CA mutants were grown under low pCO2 (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S3). Unlike a controlled growth chamber experiment, a continuing rise in global atmospheric pCO2 will likely be accompanied by climatic changes (drought and temperature) with considerable regional variability (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2013), making it difficult to speculate on the requirement for CA in the future. It has been reported that maize is unlikely to benefit from rising pCO2, except under drought stress (Leakey et al., 2006). This again highlights the importance of investigating the role of CA under temperature and drought stress conditions, which may be a part of future climatic shifts.

The results presented here also impact efforts aimed at engineering C4 traits into C3 monocots, which include the introduction of a cytosolic CA into rice (Oryza sativa; Hibberd and Covshoff, 2010; Sage et al., 2012). Not only does this mutant analysis suggest that an increase in CA may not be achieved through transcriptional overexpression due to posttranscriptional regulation, because Ca2 transcript levels do not correlate with CA2 protein accumulation, but it also raises questions about the optimal level of CA. Our results suggest that a low level of CA could be maintained under current ambient pCO2, but it would be beneficial to have an inducible increase in CA under low-CO2 conditions. This would allow the plant to conserve resources under moderate growth conditions and respond to stomatal closure with high levels of CA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ds Reverse Genetic Screen

Populations for identifying Ds insertions into Ca genes were generated by test crossing female maize (Zea mays) plants (W22 inbred) lacking Ac with males carrying the Ds donor and Ac-im (Conrad and Brutnell, 2005). A total of 540 purple and spotted test-cross kernels were planted in 10 flats (9 columns by 6 rows; Hummert 11-0770) filled with MetroMix 360 (Hummert 10-0356-1) and Turface MVP (Hummert 10-2400) mixed in a 3:1 ratio by volume. Flats were grown under standard greenhouse conditions at the Boyce Thompson Institute in Ithaca, NY. After approximately 10 d, a single one-eighth-inch punch of tissue was harvested from each plant. The tissue from 18 individual plants was combined in a single tube, resulting in a total of 30 pools. DNA was then extracted from these pools using the cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide protocol for DNA isolation (available upon request). A two-primer strategy was used to identify new Ds insertions by PCR, where a single target gene primer was paired with a Ds-specific primer. Phire Taq (Thermo Scientific F-122L) was used for amplification following the recommended standard reaction and cycling conditions. PCR products were resolved using standard agarose gel electrophoresis. Pools containing putative insertions were deconvoluted to a single plant using the Phire Plant Direct PCR Kit (Thermo Scientific F-130) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Tissue was collected from a leaf other than the one used for the first collection. Finally, the exact location of the new insertion was determined by Sanger sequencing of the amplified insertion product using the Ds end primer.

Mapping Unique Reads to the 3′ UTR of Maize Ca Genes

RNA-seq reads from maize leaf tip tissues were obtained as described previously (Wang et al., 2011). Nearly 290 million reads from leaf tips were used to align 125 bp of all 3′ UTR sequences of the six maize Ca genes. Alignments were performed using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner algorithm with default settings (Li and Durbin, 2009). The alignment results were then processed using a custom Perl script to identify unique mapped reads (available upon request). Final counts were normalized by the total number of all reads mapped before plotting.

CA Immunoblot Analysis

Maize seedlings were grown in a BDW-40 chamber (Conviron) with a 12-h day/night period. The chamber was set for 31°C/22°C day/night temperatures with a light intensity of 550 µmol m−2 s−2 and relative humidity of 50%. The plants were watered as needed and grown at ambient pCO2. Two-week-old leaf blade tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in a Fluid Management Harbil 5G-HD paint shaker. Protein extracts were prepared in buffer containing 50 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mm dithiothreitol, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Extracts were centrifuged at 17,000g for 15 min, and the resulting protein concentration was measured using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies). Samples were normalized using SDS sample buffer containing 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 μg of total protein of each sample was loaded onto NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels (Life Technologies). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes at 200 V for 1 h and challenged overnight with a primary polyclonal antibody (from rabbit) made against rice (Oryza sativa) CA at a dilution of 1:10,000 (generously provided by Jim Burnell). The secondary anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody (from donkey; GE Healthcare) was used at a dilution of 1:50,000. Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Life Sciences) were used, and labeled proteins were visualized with the Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ System.

Growth Conditions for Physiological Measurements

Plants were grown in a controlled-environment growth chamber (Biochambers; TPC-19) at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 500 µmol quanta m−2 s−1 at plant height, relative humidity of approximately 50%, air temperature of 31°C/22°C day/night with a 16-h day, and CO2 concentration of either 928 Pa (1%; high-CO2 plants) or 11.8 Pa (0.0018%; low-CO2 plants). Plants were grown for 22 d in 1.8-gallon pots containing commercial soil (Sunshine LC1; Sun Gro Horticulture), fertilized weekly (Peters 20-20-20), and watered daily.

Plant and Leaf Composition and Dry Matter Analysis

Dry mass was estimated by weighing harvested aboveground biomass that had been dried for 96 h at 65°C. Additionally, 1.5 to 2 mg of leaf material was placed in tin capsules and combusted in a hydrogen/carbon/nitrogen elemental analyzer (ECS 4010; Costech Analytical) to determine leaf nitrogen concentration.

CA Activity Assay

Leaf discs were extracted on ice in a glass homogenizer in 1 mL of 50 mm HEPES (pH 7.8), 1% (v.v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 2% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Crude extracts were centrifuged at 4°C for 1 min at 13,300g, and the supernatant was collected for soluble CA assay. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μL of extraction buffer, centrifuged at 4°C for 1 min at 2,500g, and the supernatant was collected for the membrane fraction (Furbank et al., 2001). Activity was measured using a membrane inlet mass spectrometer to measure the rates of 18O2 exchange from labeled 13C18O2 to H216O at 25°C with a total carbon concentration of 1 mm (Badger and Price, 1989; von Caemmerer et al., 2004; Cousins et al., 2008). The hydration rates were calculated from the enhancement in the rate of 18O loss over the uncatalyzed rate, and the nonenzymatic first-order rate constant was applied at pH 7.4, appropriate for the mesophyll cytosol (Jenkins et al., 1989).

Gas-Exchange Measurements

For high-CO2-grown plants, net rates of CO2 assimilation were measured on the uppermost fully expanded leaf using a LI6400XT (LI-COR Biosciences) and LI6400-22 leaf chamber with LI6400-18 light source at an oxygen partial pressure of 18.6 kPa and a leaf temperature of 25°C. Light response curves were made at a CO2 concentration of 37.2 Pa and decreasing light from 1,500 to 1,000, 800, 500, 300, and 100 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 photosynthetically active radiation. The quantum yield was estimated from the initial slope of the light response curves. The CO2 response curves were made at saturating photosynthetically active radiation of 1,000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 and at 37.2 to 18.6, 9.3, 4.7, 7.4, 14, 27.9, 46.5, 74.4, 93, and 139.5 Pa CO2. The in vivo Vpmax was estimated from the initial slope of the CO2 response curves according to von Caemmerer (2000).

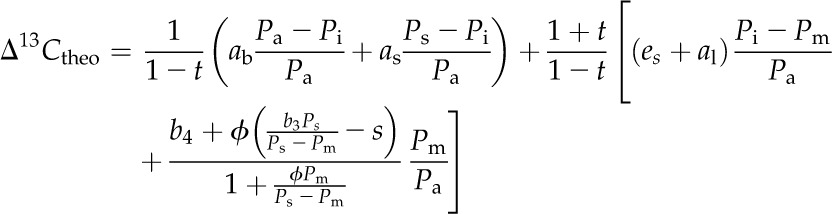

Online Leaf CO2 Discrimination

For high-CO2-grown plants, leaf discrimination against 13CO2 and C18O2 was measured by coupling the LICOR-6400XT to a tunable diode laser absorption spectroscope (TDL-AS, TGA 100A; Campbell Scientific) as described previously (Ubierna et al., 2013). The absolute concentrations of 12C16O2, 13CO2, and C18O2 of the chamber inlet (reference) and outlet (sample) air streams were measured by the TDL-AS and calibrated using a gain and offset calculated from two calibration tanks (Liquid Technology), according to Bowling et al. (2003) and Ubierna et al. (2013). The mole fractions of the isotopologs were expressed in the common delta notation, δ13C (‰; against the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite standard) and δ18O (‰; against the Vienna Mean Ocean Water standard). Photosynthetic discrimination (Δ13C and Δ18O) was estimated as described by Evans et al. (1986):

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where δe, δo, Pe, and Po are the δ and pCO2 air entering (e) and leaving (o) the leaf chamber, respectively.

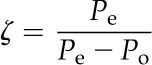

Photosynthetic isotope discrimination against 13CO2 was modeled according to the C4 isotope model (Farquhar, 1983), including the ternary effect (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012):

|

(3) |

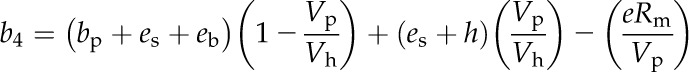

where Pa, Pi, Ps, and Pm are the pCO2 in the atmosphere, intercellular space, bundle sheath cells, and mesophyll cells, respectively, and es (1.1‰), ab (2.9‰), as (4.4‰), al (0.7‰), and s (1.8‰) are the fractionations associated with CO2 diffusion through the dissolution, leaf boundary layer, diffusion in air, aqueous diffusion, and leakage from the bundle sheath cells, respectively. Rubisco fractionation (b3) is calculated as b′3 − (eRd + fVo)/Vc, with b′3 (30‰), e (0‰), and f (11.6‰) as the fractionation associated with Rubisco, respiration, and photorespiration, respectively, and Rd, Vo, and Vc as the rates of respiration, Rubisco oxygenation, and carboxylation, respectively (von Caemmerer, 2000). The fractionation of PEPC, respiration, and the isotopic equilibrium during the dissolution of CO2 and the conversion to HCO3− (b4) is calculated (Farquhar, 1983; Cousins et al., 2006a) as:

|

(4) |

where bp (2.2‰) is the fractionation by PEPC (O’Leary, 1981), es (1.1‰) is the fractionation as CO2 dissolves (O’Leary, 1984), and eb (−9‰) is the equilibrium fractionation factor of the CA-catalyzed hydration/dehydration reactions of CO2 and HCO3− (Mook et al., 1974). Alternatively, during the hydration/dehydration reactions, the uncatalyzed equilibrium fractionation factor eb = −7.8‰ (Marlier and O’Leary, 1984). The fractionation when CO2 and HCO3− are not at equilibrium is dependent on the rate of CA-mediated CO2 hydration (Vh), the rate of PEPC (Vp), es, and the catalyzed fractionation during CO2 hydration (h). The catalyzed hydration reaction has a fractionation factor of 1.1‰ (calculated by summing the catalyzed CO2 and HCO3− equilibrium fractionation factor −9.0‰ and the catalyzed dehydration fractionation factor 10.1‰; Mook et al., 1974; Paneth and O’Leary, 1985), whereas the uncatalyzed reaction has a 6.9‰ fractionation factor (Marlier and O’Leary, 1984). The fractionation attributed to mitochondrial respiration is e at a rate of mesophyll CO2 release of Rm.

Rubisco and PEPC Activity Assays

Leaf discs were extracted similarly to the CA assays described above. However, Rubisco activity was spectrophotometrically measured according to Walker et al. (2013) in 100 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid, pH 8.0, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm creatine phosphate, 20 mm NaHCO3, 0.5 mm ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate, 0.2 mm NADH, 12.5 units mL−1 creatine phosphate kinase, 250 units mL−1 CA, 22.5 units mL−1 phosphoglycerolkinase, 20 units mL−1 glyceraldehyde-3-phosphodehydrogenase, 56 units mL−1 triose isomerase, and 20 units mL−1 glycerol-3-phosphodehydrogenase. PEPC activity was assayed in 100 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid, pH 8.0, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm NaHCO3, 0.2 mm NADH, 5 mm Glc-6-P, 12 units mL−1 malate dehydrogenase, and 4 mm phosphoenolpyruvate. NADH consumption was monitored at 340 nm.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Expression profile of the tandemly duplicated CA genes in Z. mays.

Supplemental Figure S2. Net rates of CO2 assimilation in response to changes in PAR.

Supplemental Figure S3. Dry weight biomass of mutant plants grown at low CO2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kevin Ahern for technical and field assistance with the insertional mutagenesis screen, Lwanga Nsubuga for assistance with the gas-exchange measurements, Charles Cody for technical assistance with growth chamber experiments, and Jim Burnell for providing the anti-CA antibody.

Glossary

- PEPC

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- UTR

untranslated region

- pCO2

CO2 partial pressure

- Vpmax

maximal rate of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- ∆13C

difference in leaf 13CO2

- ∆18O

difference in leaf C18O2

- Vp/Vh

ratio of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase to carbonic anhydrase activity

- EPPS

4-2(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine propane sulfonic acid

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. IOS–1127017 and IOS–1314143 to T.P.B. and Major Research Instrumentation grant no. DBI0923562 to A.B.C.) and by the Department of Energy (Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Photosynthetic Systems grant no. DE–FG02_09ER16062 to A.B.C. and Division of Biosciences, Life Sciences Research Foundation Fellowship to A.J.S.).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Ahern KR, Deewatthanawong P, Schares J, Muszynski M, Weeks R, Vollbrecht E, Duvick J, Brendel VP, Brutnell TP. (2009) Regional mutagenesis using Dissociation in maize. Methods 49: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleman M, Kermicle JL. (1993) Somatic variegation and germinal mutability reflect the position of transposable element Dissociation within the maize R gene. Genetics 135: 189–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Pfanz H. (1995) Effect of carbonic anhydrase inhibition on photosynthesis by leaf pieces of C3 and C4 plants. Aust J Plant Physiol 22: 45–49 [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. (1989) Carbonic anhydrase activity associated with the cyanobacterium Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Physiol 89: 51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Price GD. (1994) The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 45: 369–392 [Google Scholar]

- Bowling DR, Sargent SD, Tanner BD, Ehleringer JR. (2003) Tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy for stable isotope studies of ecosystem-atmosphere CO2 exchange. Agric For Meteorol 118: 1–19 [Google Scholar]

- Conrad LJ, Brutnell TP. (2005) Ac-immobilized, a stable source of Activator transposase that mediates sporophytic and gametophytic excision of Dissociation elements in maize. Genetics 171: 1999–2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. (2006a) Carbonic anhydrase and its influence on carbon isotope discrimination during C4 photosynthesis: insights from antisense RNA in Flaveria bidentis. Plant Physiol 141: 232–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. (2006b) A transgenic approach to understanding the influence of carbonic anhydrase on C18OO discrimination during C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 142: 662–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. (2008) C4 photosynthetic isotope exchange in NAD-ME- and NADP-ME-type grasses. J Exp Bot 59: 1695–1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z, Heinhorst S, Williams EB, Murin CD, Shively JM, Cannon GC. (2008) CO2 fixation kinetics of Halothiobacillus neapolitanus mutant carboxysomes lacking carbonic anhydrase suggest the shell acts as a diffusional barrier for CO2. J Biol Chem 283: 10377–10384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EJ, Osborne CP, Strömberg CA, Smith SA, Bond WJ, Christin PA, Cousins AB, Duvall MR, Fox DL, Freckleton RP, et al. (2010) The origins of C4 grasslands: integrating evolutionary and ecosystem science. Science 328: 587–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Sharkey T, Berry J, Farquhar G. (1986) Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Funct Plant Biol 13: 281–292 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. (1983) On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol 10: 205–226 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA. (2012) Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant Cell Environ 35: 1221–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa H, Suzuki E, Komukai Y, Miyachi S. (1992) A gene homologous to chloroplast carbonic anhydrase (icfA) is essential to photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation by Synechococcus PCC7942. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 4437–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke RP, Kovar JL, Weeks DP. (1997) Intracellular carbonic anhydrase is essential to photosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at atmospheric levels of CO2: demonstration via genomic complementation of the high-CO2-requiring mutant ca-1. Plant Physiol 114: 237–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Scofield GN, Hirose T, Wang XD, Patrick JW, Offler CE. (2001) Cellular localisation and function of a sucrose transporter OsSUT1 in developing rice grains. Aust J Plant Physiol 28: 1187–1196 [Google Scholar]

- Gillon J, Yakir D. (2001) Influence of carbonic anhydrase activity in terrestrial vegetation on the 18O content of atmospheric CO2. Science 291: 2584–2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD, Burnell JN. (1990) Carbonic anhydrase activity in leaves and its role in the first step of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 93: 825–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. (1992) Short-term measurements of carbon isotope discrimination in several C4 species. Aust J Plant Physiol 19: 263–285 [Google Scholar]

- Hewett-Emmett D, Tashian RE. (1996) Functional diversity, conservation, and convergence in the evolution of the α-, β-, and γ-carbonic anhydrase gene families. Mol Phylogenet Evol 5: 50–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd JM, Covshoff S. (2010) The regulation of gene expression required for C4 photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 181–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Boisson-Dernier A, Israelsson-Nordström M, Böhmer M, Xue S, Ries A, Godoski J, Kuhn JM, Schroeder JI. (2010) Carbonic anhydrases are upstream regulators of CO2-controlled stomatal movements in guard cells. Nat Cell Biol 12: 87–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2013) Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp 3–29 [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CLD, Furbank RT, Hatch MD. (1989) Inorganic carbon diffusion between C4 mesophyll and bundle sheath cells: direct bundle sheath CO2 assimilation in intact leaves in the presence of an inhibitor of the C4 pathway. Plant Physiol 91: 1356–1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leakey AD, Uribelarrea M, Ainsworth EA, Naidu SL, Rogers A, Ort DR, Long SP. (2006) Photosynthesis, productivity, and yield of maize are not affected by open-air elevation of CO2 concentration in the absence of drought. Plant Physiol 140: 779–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Ponnala L, Gandotra N, Wang L, Si Y, Tausta SL, Kebrom TH, Provart N, Patel R, Myers CR, et al. (2010) The developmental dynamics of the maize leaf transcriptome. Nat Genet 42: 1060–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YK, Stemler AJ. (2002) Extrinsic photosystem II carbonic anhydrase in maize mesophyll chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 128: 643–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M. (2012) Carbonic anhydrase and the molecular evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 35: 22–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlier J, O’Leary M. (1984) Carbon kinetic isotope effects on the hydration of carbon dioxide and dehydration of bicarbonate ion. J Am Chem Soc 106: 5054–5057 [Google Scholar]

- Mook W, Bommerson J, Staverman W. (1974) Carbon isotope fractionation between dissolved bicarbonate and gaseous carbon dioxide. Earth Planet Sci Lett 22: 169–176 [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Bartlett SG, Samuelsson G. (2001) Carbonic anhydrase in plants and algae. Plant Cell Environ 24: 141–153 [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JV, Ma Y, Frey WD, Fusilier KA, Pham TT, Simms TA, DiMario RJ, Yang J, Mukherjee B. (2011) The carbonic anhydrase isoforms of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: intracellular location, expression, and physiological roles. Photosynth Res 109: 133–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary M. (1981) Carbon isotope fractionation in plants. Phytochemistry 20: 553–567 [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary M. (1984) Measurement of the isotope fractionation associated with the diffusion of carbon dioxide in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem 88: 823–825 [Google Scholar]

- Paneth P, O’Leary MH. (1985) Carbon isotope effect on dehydration of bicarbonate ion catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase. Biochemistry 24: 5143–5147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Christin PA, Edwards EJ. (2011) The C4 plant lineages of planet Earth. J Exp Bot 62: 3155–3169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Coleman JR. (2001) Effects of low atmospheric CO2 on plants: more than a thing of the past. Trends Plant Sci 6: 18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sage TL, Kocacinar F. (2012) Photorespiration and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 63: 19–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama ZA, El-Fouly MM, Lazova G, Popova LP. (2006) Carboxylating enzymes and carbonic anhydrase functions were suppressed by zinc deficiency in maize and chickpea plants. Acta Physiol Plant 28: 445–451 [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon RS, Lin H, Childs KL, Hansey CN, Buell CR, de Leon N, Kaeppler SM. (2011) Genome-wide atlas of transcription during maize development. Plant J 66: 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So AKC, John-McKay M, Espie GS. (2002) Characterization of a mutant lacking carboxysomal carbonic anhydrase from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Planta 214: 456–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Cousins AB. (2011) The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions: assumptions and calculations with CO2 isotope discrimination. J Exp Bot 62: 3119–3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Kramer DM, Cousins AB. (2013) The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions in Zea mays, Miscanthus × giganteus and Flaveria bidentis. Plant Cell Environ 36: 365–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollbrecht E, Duvick J, Schares JP, Ahern KR, Deewatthanawong P, Xu L, Conrad LJ, Kikuchi K, Kubinec TA, Hall BD, et al. (2010) Genome-wide distribution of transposed Dissociation elements in maize. Plant Cell 22: 1667–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S (2000) Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Cousins AB, Badger MR, Furbank RT (2008) C4 photosynthesis and CO2 diffusion. In JE Sheehy, PL Mitchell, B Hardy, eds, Charting New Pathways to C4 Rice. International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Philippines, pp 95–116 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Furbank RT. (2003) The C4 pathway: an efficient CO2 pump. Photosynth Res 77: 191–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Quinn V, Hancock NC, Price GD, Furbank RT, Ludwig M. (2004) Carbonic anhydrase and C4 photosynthesis: a transgenic analysis. Plant Cell Environ 27: 697–703 [Google Scholar]

- Walker B, Ariza LS, Kaines S, Badger MR, Cousins AB. (2013) Temperature response of in vivo Rubisco kinetics and mesophyll conductance in Arabidopsis thaliana: comparisons to Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Environ 36: 2108–2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Si Y, Dedow LK, Shao Y, Liu P, Brutnell TP. (2011) A low-cost library construction protocol and data analysis pipeline for Illumina-based strand-specific multiplex RNA-seq. PLoS ONE 6: e26426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Gowik U, Tang H, Bowers JE, Westhoff P, Paterson AH. (2009) Comparative genomic analysis of C4 photosynthetic pathway evolution in grasses. Genome Biol 10: R68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Liu X, Quan Z, Cheng S, Xu X, Pan S, Xie M, Zeng P, Yue Z, Wang W, et al. (2012) Genome sequence of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) provides insights into grass evolution and biofuel potential. Nat Biotechnol 30: 549–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.