Abstract

Objective

Multiple biomarkers are used to assess sepsis severity and prognosis. Increased levels of the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) were previously observed in sepsis but also in end-organ injury without sepsis. We evaluated associations between sRAGE and (i) 28-day mortality, (ii) sepsis severity, and (iii) individual organ failure. Traditional biomarkers procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP) and lactate served as controls.

Methods

sRAGE, PCT, CRP, and lactate levels were observed on days 1 (D1) and 3 (D3) in 54 septic patients. We also assessed the correlation between the biomarkers and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury (AKI) and acute heart failure.

Results

There were 38 survivors and 16 non-survivors. On D1, non-survivors had higher sRAGE levels than survivors (p = 0.027). On D3, sRAGE further increased only in non-survivors (p < 0.0001) but remained unchanged in survivors. Unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for 28-day mortality was 8.2 (95% CI: 1.02–60.64) for sRAGE, p = 0.048. Receiver operating characteristic analysis determined strong correlation with outcome on D3 (AUC = 0.906, p < 0.001), superior to other studied biomarkers. sRAGE correlated with sepsis severity (p < 0.00001). sRAGE showed a significant positive correlation with PCT and CRP on D3. In patients without ARDS, sRAGE was significantly higher in non-survivors (p < 0.0001) on D3.

Conclusion

Increased sRAGE was associated with 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis, and was superior compared to PCT, CRP and lactate. sRAGE correlated with sepsis severity. sRAGE was increased in patients with individual organ failure. sRAGE could be used as an early biomarker in prognostication of outcome in septic patients.

Keywords: Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, sepsis, procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, biomarker

Introduction

Severe sepsis represents over 20% of admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU) and remains the leading cause of death, representing an important clinical and economical target. Multiple laboratory markers have been evaluated as a determinant of severity of organ failure in sepsis, and were used for prognostication of outcome [1]. Specific biomarkers with an established role in sepsis include C-reactive protein (CRP) [2], procalcitonin (PCT) [3], lactate, cytokines, coagulation parameters, and others. These markers are used both clinically and experimentally to diagnose sepsis and guide treatment [4–6].

Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a multiligand receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell surface molecules that acts as a pattern recognition receptor. RAGE was initially identified in the lung tissue which has the highest basal level of expression of RAGE under normal conditions [7]. RAGE activates pathways responsible for acute and chronic inflammation. The soluble type of this receptor, sRAGE, which acts as a decoy receptor, is a novel biomarker that has been linked to severity of sepsis and its outcome [8–11]. However, other studies linked sRAGE to chronic [12,13] or acute lung injury [10,14–18], coronary artery disease [19], cardiogenic shock [20], end-stage renal disease [21], severe trauma [22] or other diseases [11] without sepsis. Given the conflicting findings, the potential benefits of sRAGE as an independent biomarker in patients with sepsis are not yet fully elucidated.

In our study, we evaluated sRAGE as a novel marker of inflammation in septic patients with or without organ injury. We also assessed traditional biomarkers – CRP, PCT, lactate, creatinine – and their correlation with survival, severity of illness and organ injury, and with sRAGE. We hypothesized that sRAGE will have a positive correlation with severity of illness, and a negative correlation with survival. To test these hypotheses, we serially evaluated: (1) The association between plasmatic sRAGE levels early after admission and 28-day mortality, (2) the correlation between sRAGE and severity of illness, and (3) correlation of sRAGE with established biochemical markers of sepsis severity (PCT, CRP, lactate, creatinine) and organ injury.

Patients and methods

Ethical aspects

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the 1st Medical Faculty, Charles University and the General University Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic. A separate approval of the Institutional Review Board, University of Pittsburgh, was obtained for an independent data analysis by the Clinical and Translational Research Institute, University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health.

The purpose and procedures of the study were explained to participants and/or their legal representatives, and signed informed consents were obtained. The study enrolled patients older than 18 years admitted for sepsis to mixed ICU of the General University Hospital in Prague, Czech Republic. The plasmatic levels of sRAGE, procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), lactate and creatinine were assessed on admission, which was considered day 1 (D1), and on day 3 (D3).

Patients

Fifty-four patients with the age of 54 ± 16 years (mean ± SD) admitted to the mixed population ICU with clinical symptoms of sepsis were enrolled in a prospective observational study. The diagnosis of sepsis was established with regard to the previously published clinical criteria [23,24]. The severity of illness was evaluated according to the Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II criteria. The presence of selected organ injury was determined based on generally accepted criteria for individual organs. For acute kidney injury (AKI), the criteria of Acute Kidney Injury Network were used [25]; for lung injury, criteria for acute respiratory distress syndrome were used [26]. Acute heart failure was defined as a need for inotropic support to maintain cardiac index > 2.0 L/min/m2 monitored by a thermodilution method and systolic blood pressure >90 mmHg in the absence of hypovolemia. These criteria were similar to those used in a study by Selejan et al. [20].

Laboratory analyses

All routine biochemical parameters such as creatinine, lactate, CRP were determined by standard clinical-chemistry methods. PCT was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay Vidas Brahms. sRAGE levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Quantikine, R&D Systems Europe Ltd, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK).

Reference ranges used were as follows: PCT 0.0–0.05 μg/L, CRP 0.0–7.0 mg/L, creatinine 44–110 mmol/L, lactate 0.5–2.0 mmol/L. For sRAGE, widely accepted reference range was not established; however, the reference range of plasma sRAGE declared by the manufacturer for 42 healthy subjects was 382–4329 pg/mL, mean 1655 ± 693 pg/mL. In a contemporaneous study from our center using the same methodology, a healthy control group (n = 154) had sRAGE levels 1723 ± 643 pg/mL [27]. The intra-assay coefficient of variation (means 571–3189) was 4.8–6.1%, while inter-assay coefficient of variation (means 519–2890) was 6.7–8.7%. Kit series number was DRG00.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistica CZ 7.0 software (StatSoft Inc, USA), Cutoff Finder freeware (http://molpath.charite.de/cutoff/index.jsp) or SPSS 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, USA). Mann-Whitney U test was performed to compare continuous variables between two groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of individual biomarkers to predict outcome. Comparison of ROC curves was used to evaluate the diagnostic performance of individual biomarkers [28]. Logistic regression was used to test the independent association of sRAGE and 28-day mortality. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used as a measure of linear relationship between two sets of data. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the patient population are shown in Table I. There were 38 survivors and 16 non-survivors. The non-survivors tended to be older, but this trend did not reach statistical significance.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the patient population.

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Females | 13 (24%) |

| Males | 41 (76%) |

| Age (years), median (interquartile range) | 64 (57; 76) |

| 28-days survival, n (%) | |

| Yes | 38 (70%) |

| No | 16 (30%) |

| Blood culture, n (%) | |

| G+ bacteria | 8 (15%) |

| G− bacteria | 16 (30%) |

| Fungi | 8 (15%) |

| Negative | 22 (40%) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | |

| Yes | 9 (17%) |

| No | 45 (83%) |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | |

| Yes | 35 (65%) |

| No | 19 (35%) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | |

| Yes | 18 (33%) |

| No | 36 (67%) |

| APACHE score, median (interquartile range) | 27 (22; 36) |

APACHE, Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation.

No patients died within the period of the three days when blood samples were collected. There were no patients lost to follow-up. There were no differences between different etiologic agents of sepsis (i.e. Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative vs. mycotic) in individual biomarkers (data not shown).

Survival and severity of illness

sRAGE levels were significantly higher in non-survivors vs. survivors on both D1 and D3. In non-survivors, the levels further increased between D1 and D3, while they remained similar in survivors (Figure 1). The ROC analysis of sRAGE for 28-day mortality revealed area under curve (AUC) greater than 0.5 on both D1 (AUC = 0.660; p = 0.066) and D3 (AUC = 0.913; p < 0.001), suggesting poor correlation with 28-day mortality on D1 but excellent correlation on D3 [29]. On both days, sRAGE was significantly better predictor of 28-day mortality than PCT (D1: AUC = 0.377, p = 0.157; D3: AUC = 0.669, p = 0.053) or CRP, respectively (D1: AUC = 0.444; p = 0.523; D3: AUC = 0.419, p = 0.357). Lactate was superior to sRAGE on D1 (AUC = 0.805, p < 0.001) but not on D3 (AUC = 0.747; p = 0.005) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Differences in sRAGE levels between survivors and non-survivors on days 1 and 3. sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristics of individual biomarkers for predicting 28-day mortality. Left panel, day 1; right panel, day 3. sRAGE shows superior characteristics to other biomarkers on day 3. sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products; PCT, procalcitonin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Using pooled sRAGE data from both D1 and D3, unadjusted odds ratio for 28-day survival was 8.250 (95% CI 1.017; 60.636), p = 0.048 for cutoff sRAGE level of 1721 pg/mL.

Logistic regression showed independent association of increased sRAGE on D3 with 28-day mortality(OR1.002;95%CI = 1.00004; 1.00396; p = 0.014), with best cut-off sensitivity 94% and specificity 79%, cut-off value 2003 pg/mL. No such statistically significant association was identified for D1.

sRAGE levels correlated well with the severity of the illness on D3 (p < 0.0001) but not on D1 when only a borderline significance was observed (p = 0.059) (Figure 3). We also dichotomized sRAGE levels on D3 in non-survivors to ‘low’ vs. ‘high’. Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis did not show difference in survival time (5.5 ± 1.7 days vs. 5.9 ± 2.4 days; p = 0.925; See Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/21695717.2013.849357). When the entire patient population, i.e. both survivors and non-survivors, was dichotomized around the median sRAGE level on D3 (940 pg/mL) to ‘low’ vs. ‘high’, the difference in survival time between the groups was significant (p = 0.007; Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, available online at http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/21695717.2013.849357).

Figure 3.

The correlation between soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) levels and Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score on days 1 and 3.

Lactate levels were significantly higher in non-survivors vs. survivors on D1 and D3 (p = 0.0006 and p < 0.0001, respectively). PCT was higher in non-survivors only on D3 (p = 0.041). CRP and creatinine did not differ between non-survivors and survivors at either time-point (Table II).

Table II.

Number of patients with individual organ failures.

| Number of failing organs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Survivors | 18 | 12 | 7 | 1 |

| Non-survivors | 0 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

Non-survivors had a higher number of failing organs per patient vs. survivors (p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney test).

Correlation between biomarkers

As expected, sRAGE showed a significant positive correlation with serum creatinine (r = 0.237, p = 0.037 on D1; and r = 0.397, p = 0.015, on D3; respectively). A strong positive correlation was found in sRAGE and lactate at both D1 and D3 (r = 0.453 and r = 0.529, respectively, p < 0.001).

sRAGE values showed a significant positive correlation with CRP and PCT only on D3 (CRP: r = 0.496, p = 0.016; PCT: r = 0.45, p = 0.007, respectively). Strong positive correlation of sRAGE and PCT on D3 was observed both in survivors and non-survivors.

Pairwise comparison of ROC curves of individual biomarkers did not reveal any statistically significant differences on D1. However, the diagnostic ability of sRAGE was significantly superior to both PCT (p = 0.0004) and CRP (p = 0.002) on D3 but not lactate (p = 0.19). Lactate had better diagnostic ability than either PCT (p = 0.038) or CRP (p = 0.014).

Organ injury

There was a higher number of failing organs per patient in non-survivors (mean = 2; IQR 2–2) vs. survivors (mean = 1; IQR 0–1; p < 0.001; Table II). The number of organ failures in non-survivors did not affect survival time (p = 0.719, Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, available online). However, in the entire patient population, i.e. in both survivors and non-survivors, the survival time was significantly different depending on the number of organ failures (p < 0.001; Supplementary material, online).

ARDS

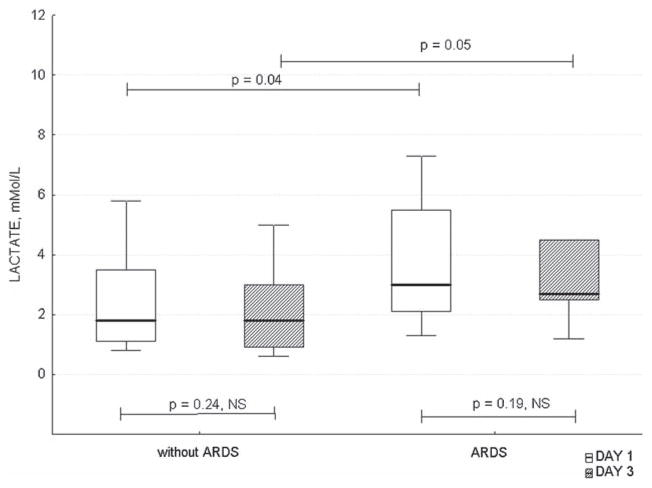

sRAGE levels were similar in septic patients with vs. without ARDS on D1, but were higher on D3 vs. D1 (p = 0.027). sRAGE levels also increased in patients with ARDS between D1 and D3 (Figure 4). In patients without ARDS, sRAGE was significantly higher in non-survivors vs. survivors on D3. Similar values were observed in non-survivors and survivors in patients with ARDS on D3, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table III). Lactate was higher in patients with vs. without ARDS on both D1 and D3, but the levels did not change over time in subgroups (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Differences in sRAGE levels between patients with vs. without ARDS on days 1 and 3. sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Table III.

Biomarkers in survivors and non-survivors.

| Day 1

|

Day 3

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-survivors n = 16 | survivors n = 38 | p-value* | non-survivors n = 16 | survivors n = 38 | p-value* | |

| CRP mg/L | 183 (36;286) | 195 (98;320) | 0.55 | 190 (46;266) | 196 (129;276) | 0.54 |

| PCT ng/mL | 9.4 (0.82;13.05) | 12.20 (4;36.60) | 0.14 | 33.90 (12.95;74.51) | 20 (5.10;51) | 0.041 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 2261 (895;3366) | 1033.50 (605;1789) | 0.037 | 5263 (2621;6091) | 940 (561;1758) | < 0.0001 |

| Lactate mmol/L | 3.50 (2.20;8.50) | 1.75 (1.10;2.90) | 0.0006 | 3.90 (2.55;12.10) | 1.45 (0.90;2.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 172 (100;271.50) | 151 (91;252) | 0.51 | 201.50 (177;267) | 155 (91;248) | 0.10 |

Medians (IQR) of measured parameters on day 1 and day 3 in survivors and non-survivors.

sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products; PCT, procalcitonin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Figure 5.

Differences in lactate levels between patients with vs. without ARDS on days 1 and 3. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Acute kidney injury

sRAGE was higher in non-survivors vs. survivors in subgroups of patients with or without AKI. sRAGE was higher in survivors with AKI vs. without AKI (Table IV). Irrespective of survival, sRAGE, lactate and creatinine were higher in patients with vs. without AKI on both D1 and D3, while PCT was higher only on D3 (Table V).

Table IV.

sRAGE levels in survivors and non-survivors with respect to organ injury.

| non-survivors | survivors | |

|---|---|---|

| ARDS | ||

| yes | 7 | 2 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 5328 (3664;5674) | 1101 (783;1419) |

| no | 36 | 9 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 5197 (2305;7040) | 940 a (542;1798) |

| AKI | ||

| yes | 14 | 21 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 4693 (2341;5909) | 1699 c,d (7650;3010) |

| no | 2 | 17 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 5901 (5328;6475) | 607 b (487;976) |

| AHF | ||

| yes | 10 | 8 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 5656 (2223;6516) | 1436 (596;3047) |

| no | 6 | 30 |

| sRAGE pg/mL | 4693 (2949;5406) | 854 e (515;1755) |

sRAGE levels in survivors and non-survivors based on the presence or absence of individual organ injury on day 3. Values represent median (IQR).

p = 0.002 between survivors and non-survivors;

p = 0.012 between survivors and non-survivors;

p = 0.001 between survivors and non-survivors;

p = 0.008 between survivors with AKI vs. without AKI;

p = 0.025 between survivors and non-survivors.

ARDS; acute respiratory distress syndrome; AKI; acute kidney injury; AHF, acute heart failure.

Table V.

Differences in biomarkers in patients with or without acute kidney injury.

| sRAGE pg/mL | PCT ng/mL | CRP mg/L | Lactate mmol/L | Creatinine μmol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1/AKI no | 742 (516;1714) | 12.9 (1.8;25) | 164 (38;320) | 1.6 (1.1;2.3) | 91 (66;124) |

| D1/AKI yes | 1541 (987;3129) | 11 (2.6;36.6) | 238 (41;290) | 2.4 (1.3;5.5) | 224 (147;423) |

| p value | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.14 | 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| D3/AKI no | 710 (491;1281) | 10.5 (4.3;32) | 129 (50;214) | 1.4 (0.9;2.5) | 92 (66;172) |

| D3/AKI yes | 2399 (1419;5011) | 34 (12.8;75) | 249 (129;284) | 2.6 (1.2;4.5) | 206 (160;342) |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.01 | < 0.0001 |

Differences in measured parameters on days 1 and 3 depending on the presence of acute kidney injury, irrespective of the survival. Values represent median (IQR). p values were determined by a Mann-Whitney test. sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products; PCT, procalcitonin; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Acute heart failure

sRAGE was higher in non-survivors vs. survivors in patients with acute heart failure, but not in patients without (Table IV). Irrespective of survival, on D1, patients with vs. without acute heart failure had higher CRP and creatinine. On D3, patients with vs. without acute heart failure had higher PCT, sRAGE and creatinine. Differences in other biomarkers did not reach statistical significance (Table VI).

Table VI.

Differences in biomarkers in patients with or without acute heart failure.

| sRAGE pg/mL | PCT ng/mL | CRP mg/L | Lactate mmol/L | Creatinine μmol/L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1/AHF no | 1055 (560;1849) | 13.5 (8.5;47.5) | 226 (113;343) | 1.9 (1.1;3.1) | 124 (76;270) |

| D1/AHF yes | 1960 (1011;3710) | 5.6 (0.7;5.6) | 52 (24;257) | 2.4 (1.2;6.4) | 180 (135;333) |

| p value | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| D3/AHF no | 997 (581;2709) | 20 (6.6;64.8) | 197 (118;266) | 1.8 (0.9;2.75) | 155 (79;286) |

| D3/AHF yes | 2863 (1436;6091) | 27.8 (16.1;60.5) | 177 (33;265) | 3.8 (1.5;9.85) | 205 (173;257) |

| p value | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

Differences in measured parameters on days 1 and 3 depending on the presence of acute heart failure, irrespective of the survival. Values represent median (IQR). p values were determined by a Mann-Whitney test. sRAGE, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products; PCT, procalcitonin; CRP, C-reactive protein; AHF, acute heart failure.

Discussion

We serially investigated sRAGE, a novel biomarker, in patients with sepsis with or without organ failure. Our results document that early sRAGE levels correlated with the 28-day mortality from sepsis, and that sRAGE levels on D3 correlated with the severity of illness. Moreover, sRAGE correlated well with established biomarkers of sepsis, further strengthening its value. Only sRAGE and lactate had predictive value for 28-day mortality on D1 and D3; PCT was also able to predict mortality only on D3. sRAGE was superior in predicting outcome to PCT or CRP. CRP was unable to predict 28-day mortality in our study population.

sRAGE was also increased in non-survivors vs. survivors in patients without ARDS or acute heart failure. Non-surviving patients with ARDS or acute heart failure had also higher sRAGE levels compared to survivors. sRAGE was increased in non-survivors vs. survivors irrespective of the presence of AKI. Our findings support a valuable role of sRAGE in determining the prognosis early in the course of sepsis with or without organ failure.

None of the currently used biomarkers shows optimal sensitivity and specificity for sepsis [1]. Individual biomarkers have different characteristics. Clinically, it is advised to use a panel of biomarkers to increase the accuracy of the assessment of inflammatory disease, and to differentiate sepsis from systemic inflammatory response syndrome [30]. We explored the trends of multiple sepsis biomarkers over the first 48 hours of inflammatory response. Rather than absolute values, the increasing trend in sRAGE was characteristic for non-survivors in our cohort. Similar trend was observed also for PCT. Both of these parameters, or their trends, could be useful in predicting survival.

We observed an increasing PCT levels in non-survivors over the 48 hours. Karlsson et al. could not demonstrate a difference in PCT between survivors vs. non-survivors in sepsis, but mortality was significantly decreased in patients with decreasing PCT levels within the first 72 hours [31]. This underscores the importance of a serial assessment of biomarkers, with individual values being less informative than the trend over time.

A strong correlation of sRAGE with APACHE II scores, reflecting the severity of illness, was also demonstrated. This correlation was also tighter over time. We chose APACHE II scoring system over Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS) or others [32], because APACHE II was shown to correlate well with SOFA and it outperformed SOFA in predicting mortality in critically ill patients [33,34], the primary endpoint of our study.

Correlation between plasma levels of sRAGE with PCT or CRP was shown only on D3, i.e. after 48 hours, both in survivors and non-survivors, which is surprising, given the early onset of PCT production in sepsis.

The role of RAGE in sepsis has been explored only in a limited number of experimental and clinical studies so far that yielded controversial results. RAGE is expressed in high levels in lung tissue even under normal conditions whereas other tissues express RAGE at low levels, including immune system cells. RAGE binds variety of ligands actively participating in inflammation and immune responses. One of these ligands is high-mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 (HMBG-1). The interaction of HMBG-1 with cell-surface RAGE triggers inflammatory response due to activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine. Increased NF-κB activation has been demonstrated to be a predictor of outcome in septic patients [35].

The origin of circulating sRAGE is not yet fully explored. The evidence suggests that sRAGE is probably produced by ectodomain shedding [36,37]. Experimental models of sepsis using sRAGE as a therapy showed attenuation of inflammation-induced lung injury [38]. These findings are further corroborated by studies using knock-out mice (RAGE−/−) that are protected from certain chronic inflammatory diseases. sRAGE administered to wild-type mice resulted in better protection from inflammation than observed in RAGE−/− mice, suggesting that sRAGE may also prevent other ligands from interacting with receptors other than RAGE [39]. Anti-RAGE antibody was efficient in improving survival from experimental sepsis in a dose-dependent fashion, even when the treatment was delayed. The survival achieved by blocking the receptor were similar to survival in RAGE−/− or RAGE+/− mice [40].

Specific studies assessed sRAGE in patients with ALI and/or sepsis with organ dysfunction. A separate body of literature explored the role of sRAGE in chronic inflammatory diseases, including diabetes mellitus and its complications, coronary artery disease or neuroinflammatory diseases.

First reports exploring the role of sRAGE in a clinical setting concluded that sRAGE is increased in sepsis and the magnitude of its increase correlates with sepsis severity. Higher levels were observed in non-survivors [9]. Given the fact that RAGE is primarily located in the basal surface of alveolar type I cells, there were concerns that sRAGE may be associated with lung injury rather than sepsis. This was based on experimental data supporting the role of sRAGE in lung injury [41]. Using sRAGE as therapeutic modality rather than a biomarker attenuated endotoxin-induced lung injury in a murine model [38]. Several clinical studies supported the role of RAGE in lung diseases. In COPD patients, sRAGE levels were higher than in healthy controls, but surprisingly lower values were seen in acute exacerbation of COPD compared to stable COPD [13]. In contrast, Miniati et al. showed opposite results, with lower sRAGE levels in COPD patients [12]. In lung transplant patients, higher plasma RAGE levels correlated with the duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay [14]. Serum sRAGE was significantly decreased in lung cancer patients compared with healthy controls or patients with tuberculosis [16]. In ALI/ARDS patients, plasma and alveolar sRAGE correlated with lung injury and infection over time [17]. sRAGE also correlated with impaired lung function in infants and young children undergoing cardiac surgery [18].

Most importantly, two studies focused on sRAGE in septic patients with or without ALI. Kikkawa et al. documented an increase in sRAGE on day 1 in septic patients who did not develop ALI vs. those with ALI [10]. These finding are in contradiction to a larger study by Jabaudon et al. who reported higher sRAGE levels in patients with ALI/ARDS, regardless of presence or absence of sepsis [15]. Nakamura et al. found in patients with ARDS with severe infection that higher sRAGE were associated with death in ARDS patients, but severity of illness was not. HBGB-1 correlated with sRAGE [42]. Narvaez-Rivera et al. showed a positive correlation between sRAGE, SOFA and mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia and ARDS [43].

In our study, all patients met the criteria for sepsis. Given the current conundrum germane to the role of sRAGE in sepsis and/or ARDS, we further explored the role of sRAGE and other biomarkers in dichotomized patient population with vs. without ARDS. On D1, there were no differences in sRAGE between these groups, while on D3, patients with ARDS had higher sRAGE levels. The lack of difference in sRAGE levels on D1 argues against a major effect of ALI/ARDS in our study population. On D3, the levels of sRAGE were higher in non-survivors vs. survivors in patients without ARDS. Similar values were observed in patients with ARDS. Thus, our results support the hypothesis that sRAGE in septic patients is more reflective of the severity of sepsis and ultimate outcome, irrespective of the presence of ARDS. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution since there were only nine patients with ARDS in our study, and only two patients survived. The hypothesis that sRAGE can reliably predict survival in septic patients with ARDS needs to be tested in a larger study in this specific population with high mortality.

In our study, sRAGE levels also correlated with AKI. Creatinine was used as a surrogate marker of renal function. We observed strong correlation between sRAGE and creatinine, which corroborates previously described correlation between sRAGE and renal function [21]. sRAGE levels in survivors were higher in patients with AKI vs. without AKI. This may represent either higher production of sRAGE with AKI, or delayed elimination. On the contrary, Nakashima et al showed inverse correlation between sRAGE and CRP, with no prognostic value of sRAGE for mortality in hemodialysis patients [44]. Of note, no patient received hemodialysis or a continuous renal replacement therapy within the first 48 h of treatment in our study, leaving the creatinine levels unaffected by this therapy.

Increased sRAGE levels were also previously linked to cardiovascular disease and chronic inflammation outside sepsis. In patients with with congestive heart failure (CHF), high sRAGE levels were associated with higher incidence of cardiac death vs. low sRAGE levels [45]. sRAGE, but not AGE, was related to ischemic etiology independent of age, sex, diabetes, renal function, clinical severity, or other variables. Moreover, sRAGE was directly associated with the extent of coronary artery disease in patients with CHF [19]. We observed higher sRAGE levels in patients with acute heart failure on D1 and on D3 (p = 0.02). Also, sRAGE increased between D1 and D3 only in patients with heart failure. This may represent an effect of both CHF (the presence of which was not known to us) and acute heart failure associated with sepsis. Our results are in contrast to the recent report by Selejan et al. that non-survivors of cardiogenic shock had lower sRAGE levels than survivors [20]. These conflicting results are difficult to directly compare and interpret. Our study enrolled septic patients with secondary organ complications, while Selejan et al. studied patients in cardiogenic shock without sepsis. They also observed a negative correlation of sRAGE and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II score, which is in striking contrast to our findings. Surprisingly, survivors in the study by Selejan et al. had similar sRAGE levels as patients with acute myocardial infarction or healthy controls. These conflicting reports may suggest that sRAGE may play a different role in the pathophysiology of sepsis vs. acute heart failure. In this regard, our findings support the dominant role of the sepsis on sRAGE levels, rather than the effect of heart failure.

We did not address the possible confounding effects of pre-existing diabetes, congestive heart failure, or corticosteroid treatment of sepsis on biomarkers evaluated in our study. We cannot rule out that other medical conditions and/or therapeutic interventions could also have an independent impact on outcome. Given the small sample size we cannot rule out the possibility of confounding through multiple organ failure. Future studies should examine large sample size to address this issue directly.

Conclusions

Early increased plasma sRAGE levels showed excellent correlation with 28-day mortality, and with severity of illness in patients with sepsis. In non-survivors, sRAGE levels were increasing over the first three days, underscoring the importance of serial measurements. Positive correlations of plasmatic levels of sRAGE with traditional markers of sepsis severity, i.e. CRP, PCT and lactate were observed. sRAGE was increased in patients with ARDS, AKI or acute heart failure. sRAGE could serve as an additional independent predictor of the 28-day mortality, being superior to the traditional biomarkers. The prognostic efficacy in septic patients with ARDS needs to be determined in a larger study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers UL1 RR024153 and UL1 TR000005 to the Clinical and Translational Science Institute, University of Pittsburgh, and by the Research Program P25 of the Charles University in Prague.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care. 2010;14:R15. doi: 10.1186/cc8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent JL, Donadello K, Schmit X. Biomarkers in the critically ill patient: C-reactive protein. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhart K, Meisner M. Biomarkers in the critically ill patient: procalcitonin. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochreiter M, Schroeder S. Procalcitonin-based algorithm. Management of antibiotic therapy in critically ill patients. Anaesthesist. 2011;60:661–73. doi: 10.1007/s00101-011-1884-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochreiter M, Kohler T, Schweiger AM, Keck FS, Bein B, von Spiegel T, Schroeder S. Procalcitonin to guide duration of antibiotic therapy in intensive care patients: a randomized prospective controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;13:R83. doi: 10.1186/cc7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhart K, Hartog CS. Biomarkers as a guide for antimicrobial therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(Suppl 2):S17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley ST, Ehrhardt C. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and the lung. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:917108. doi: 10.1155/2010/917108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bopp C, Bierhaus A, Hofer S, Bouchon A, Nawroth PP, Martin E, Weigand MA. Bench-to-bedside review: the inflammation-perpetuating pattern-recognition receptor RAGE as a therapeutic target in sepsis. Crit Care. 2008;12:201. doi: 10.1186/cc6164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bopp C, Hofer S, Weitz J, Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP, Martin E, Buchler MW, Weigand MA. sRAGE is elevated in septic patients and associated with patients outcome. J Surg Res. 2008;147:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikkawa T, Sato N, Kojika M, Takahashi G, Aoki K, Hoshikawa K, Akitomi S, Shozushima T, Suzuki K, Wakabayashi G, Endo S. Significance of measuring S100A12 and sRAGE in the serum of sepsis patients with postoperative acute lung injury. Dig Surg. 2010;27:307–12. doi: 10.1159/000313687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamagishi S, Matsui T. Soluble form of a receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) as a biomarker. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010;2:1184–95. doi: 10.2741/e178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miniati M, Monti S, Basta G, Cocci F, Fornai E, Bottai M. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in COPD: relationship with emphysema and chronic cor pulmonale: a case-control study. Respir Res. 2011;12:37. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith DJ, Yerkovich ST, Towers MA, Carroll ML, Thomas R, Upham JW. Reduced soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:516–22. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00029310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calfee CS, Budev MM, Matthay MA, Church G, Brady S, Uchida T, Ishizaka A, Lara A, Ranes JL, deCamp MM, Arroliga AC. Plasma receptor for advanced glycation end-products predicts duration of ICU stay and mechanical ventilation in patients after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:675–80. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabaudon M, Futier E, Roszyk L, Chalus E, Guerin R, Petit A, Mrozek S, Perbet S, Cayot-Constantin S, Chartier C, Sapin V, Bazin JE, Constantin JM. Soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end products is a marker of acute lung injury but not of severe sepsis in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:480–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206b3ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jing R, Cui M, Wang J, Wang H. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) soluble form (sRAGE): a new biomarker for lung cancer. Neoplasma. 2010;57:55–61. doi: 10.4149/neo_2010_01_055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauri T, Masson S, Pradella A, Bellani G, Coppadoro A, Bombino M, Valentino S, Patroniti N, Mantovani A, Pesenti A, Latini R. Elevated plasma and alveolar levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts are associated with severity of lung dysfunction in ARDS patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2010;222:105–12. doi: 10.1620/tjem.222.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Chen Q, Shi S, Shi Z, Lin R, Tan L, Yu J, Shu Q, Fang X. Plasma sRAGE enables prediction of acute lung injury after cardiac surgery in children. Crit Care. 2012;16:R91. doi: 10.1186/cc11354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raposeiras-Roubin S, Rodino-Janeiro BK, Grigorian-Shamagian L, Moure-Gonzalez M, Seoane-Blanco A, Varela-Roman A, Alvarez E, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR. Soluble receptor of advanced glycation end products levels are related to ischaemic aetiology and extent of coronary disease in chronic heart failure patients, independent of advanced glycation end products levels: new roles for soluble RAGE. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:1092–100. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selejan SR, Poss J, Hewera L, Kazakov A, Bohm M, Link A. Role of receptor for advanced glycation end products in cardiogenic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1513–22. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318241e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalousova M, Hodkova M, Kazderova M, Fialova J, Tesar V, Dusilova-Sulkova S, Zima T. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in patients with decreased renal function. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:406–11. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen MJ, Carles M, Brohi K, Calfee CS, Rahn P, Call MS, Chesebro BB, West MA, Pittet JF. Early release of soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts after severe trauma in humans. J Trauma. 2010;68:1273–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181db323e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:530–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, LeGall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. Report of the American-European consensus conference on ARDS: definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes and clinical trial coordination. The Consensus Committee. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:225–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01704707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krechler T, Jachymova M, Mestek O, Zak A, Zima T, Kalousova M. Soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products (sRAGE) and polymorphisms of RAGE and glyoxalase I genes in patients with pancreas cancer. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:882–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 1978;8:283–98. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Punyadeera C, Schneider EM, Schaffer D, Hsu HY, Joos TO, Kriebel F, Weiss M, Verhaegh WF. A biomarker panel to discriminate between systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis and sepsis severity. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3:26–35. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.58666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlsson S, Heikkinen M, Pettila V, Alila S, Vaisanen S, Pulkki K, Kolho E, Ruokonen E. Predictive value of procalcitonin decrease in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R205. doi: 10.1186/cc9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent JL, Moreno R. Clinical review: scoring systems in the critically ill. Crit Care. 2010;14:207. doi: 10.1186/cc8204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho KM, Lee KY, Williams T, Finn J, Knuiman M, Webb SA. Comparison of Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score with organ failure scores to predict hospital mortality. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:466–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.04999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minne L, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E. Evaluation of SOFA-based models for predicting mortality in the ICU: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2008;12:R161. doi: 10.1186/cc7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liliensiek B, Weigand MA, Bierhaus A, Nicklas W, Kasper M, Hofer S, Plachky J, Grone HJ, Kurschus FC, Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Martin E, Schleicher E, Stern DM, Hammerling GG, Nawroth PP, Arnold B. Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) regulates sepsis but not the adaptive immune response. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1641–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI18704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raucci A, Cugusi S, Antonelli A, Barabino SM, Monti L, Bierhaus A, Reiss K, Saftig P, Bianchi ME. A soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is produced by proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-bound form by the sheddase a disintegrin and metalloprotease 10 (ADAM10) Faseb J. 2008;22:3716–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-109033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Bukulin M, Kojro E, Roth A, Metz VV, Fahrenholz F, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Postina R. Receptor for advanced glycation end products is subjected to protein ectodomain shedding by metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35507–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, Tasaka S, Shiraishi Y, Fukunaga K, Yamada W, Seki H, Ogawa Y, Miyamoto K, Nakano Y, Hasegawa N, Miyasho T, Maruyama I, Ishizaka A. Role of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products on endotoxin-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:356–62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1069OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Stern DM, Arnold B, Nawroth PP. Advanced glycation end product receptor-mediated cellular dysfunction. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1043:676–80. doi: 10.1196/annals.1333.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutterloh EC, Opal SM, Pittman DD, Keith JC, Jr, Tan XY, Clancy BM, Palmer H, Milarski K, Sun Y, Palardy JE, Parejo NA, Kessimian N. Inhibition of the RAGE products increases survival in experimental models of severe sepsis and systemic infection. Crit Care. 2007;11:R122. doi: 10.1186/cc6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su X, Looney MR, Gupta N, Matthay MA. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) is an indicator of direct lung injury in models of experimental lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L1–5. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90546.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura T, Sato E, Fujiwara N, Kawagoe Y, Maeda S, Yamagishi S. Increased levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) are associated with death in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:601–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narvaez-Rivera RM, Rendon A, Salinas-Carmona MC, Rosas-Taraco AG. Soluble RAGE as a severity marker in community acquired pneumonia associated sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakashima A, Carrero JJ, Qureshi AR, Miyamoto T, Anderstam B, Barany P, Heimburger O, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B. Effect of circulating soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) and the proinflammatory RAGE ligand (EN-RAGE, S100A12) on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2213–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03360410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raposeiras-Roubin S, Rodino-Janeiro BK, Grigorian-Shamagian L, Moure-Gonzalez M, Seoane-Blanco A, Varela-Roman A, Almenar-Bonet L, Alvarez E, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR. Relation of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products to predict mortality in patients with chronic heart failure independently of Seattle heart failure score. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:938–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.