Abstract

The outer membrane (OM) of almost all Gram-negative bacteria is composed of phospholipids, lipopolysaccharide, proteins and capsular or loosely adherent polysaccharides that together mediate cellular interactions with diverse environments. Most OM components are synthesized intracellularly or at the inner membrane (IM) and thus require an export mechanism. This mini-review focuses on recent progress in understanding how synthesis of one kind of capsular polysaccharide (group 2) is coupled to the export apparatus located in the IM and spanning the periplasmic space, thus providing a transport channel to the cell surface. Although the model system for these investigations is the medically important extraintestinal pathogen Escherichia coli K1 and its polysialic acid capsule, the conclusions are general for other group 2 and group 2-like polysaccharides synthesized by many different bacterial species.

Introduction

Bacterial extracellular or exo-polysaccharides (EPSs) may be homopolysaccharides composed of a single sugar residue or heteropolysaccharides with two or more monosaccharides that may or may not include branching of the main chain. The evolution of these polysaccharides has produced thousands of different somatic or O antigens as part of Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and hundreds of K (‘kapsel’) or capsular polysaccharides in diverse species. Although most investigators prefer to distinguish polysaccharides by their O antigen, capsular, EPS or enterobacterial common antigen designations, we think that EPS is a suitable term for lumping all bacterial polysaccharides whose location is external to the inner membrane (IM). [See Jann & Jann (1987) and Ørskov et al. (1977) for the historical background of Escherichia coli polysaccharides, including the development of the serological evidence originally used to identify different types of EPSs.] Despite immense structural variation there are just two or three mechanisms for exporting EPSs from their site of synthesis inside the cell to the cell surface in Enterobacteriaceae and others: (i) the group 1/4 or LPS model involves assembly of monosaccharides (building blocks) on a lipid carrier, usually undecaprenol, that is ‘flipped’ or transported across the inner or cytoplasmic membrane and either polymerized at the IM–periplasm junction or exported directly to the outer membrane (OM) if already polymerized in the cytoplasm; and (ii) the group 2/3 capsule model, in which polysaccharides are synthesized inside the cell prior to or during export to the OM without apparent periplasmic intermediates or commingling with components of the LPS pathway. The first model, which is widely variable, and includes the colanic acid or M antigen common to most strains of E. coli and diverse O antigens (Bos et al., 2007), will not be discussed here. [See recent reviews for details of this mechanism, including its ramifications for groups 1 and 4 capsules (Whitfield & Paiment, 2003; Whitfield, 2006).] Both groups 1/4 and group 2 export mechanisms require ATP-binding cassette-like (ABC) transporters to energize polysaccharide export as well as a lipid A flippase for LPS biosynthesis; in at least one case the direct binding of EPS to a specialized domain of the ATPase component of an ABC transporter has been demonstrated (Cuthbertson et al., 2007). By contrast, some polysaccharides, such as cellulose and poly-β-1,6-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, which are common biofilm matrix molecules in E. coli and other bacteria, do not seem to require ABC transporters, suggesting that the polymerases themselves might direct nascent polysaccharides across the cytoplasmic membrane, representing what may be a distinct translocation mechanism. The reader is directed to a short review by Weigel & DeAngelis (2007) for a discussion of the theoretical problems associated with polysaccharide export in the absence of a mechanism for energizing translocation.

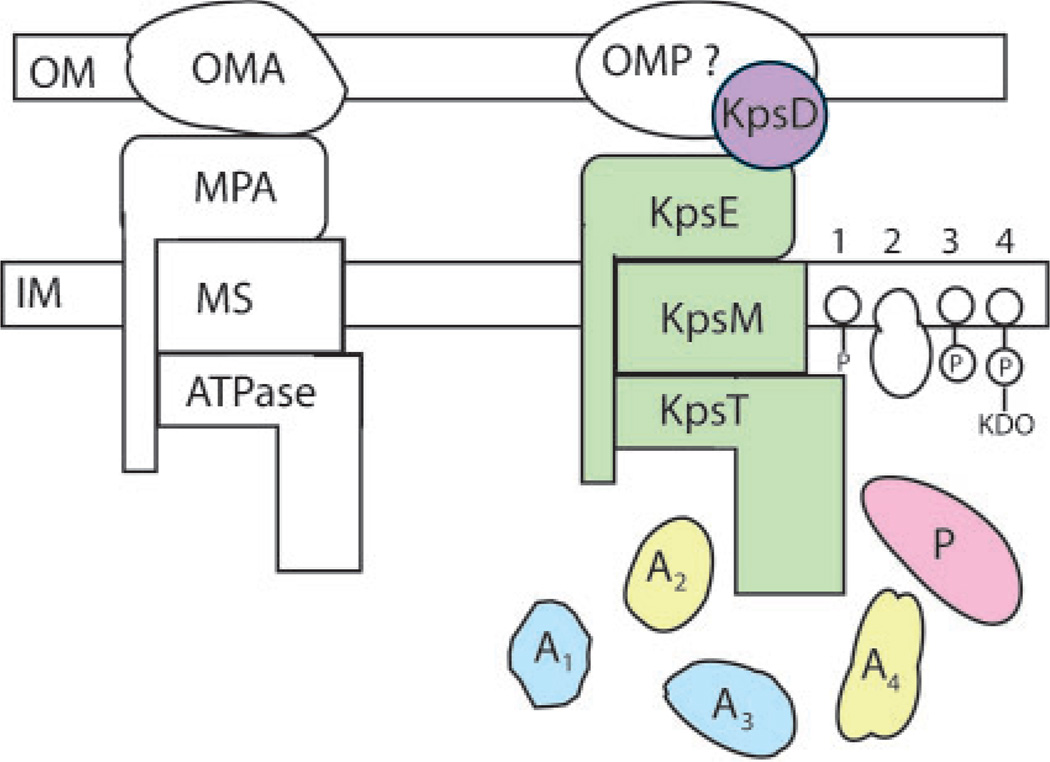

The focus of this mini-review is on the early molecular-recognition events involving heterotypic protein–protein interactions that direct group 2 and probably group 3 capsular polysaccharides to the evolutionarily conserved export apparatus composed of an ABC transporter, periplasmic connector and OM pore, shown on the right in Fig. 1. Whitfield (2006) has summarized the distinctions between groups 1–4 capsules and the reader is directed to that review for further information about capsule classification. The translocation apparatus for groups 2 and 3 capsular polysaccharides is formally analogous to the translocators for certain drugs and polypeptides that use the type I protein secretion system shown on the left in Fig. 1 (Thanabalu et al., 1998); these include substrate-specific IM ABC transporters, periplasmic connectors, and an OM exit pore provided by interactions with TolC (Silver et al., 2001). However, unlike type I secretion systems, group 2 capsule exporters invariably require additional, or accessory proteins for polysaccharide translocation (Fig. 1). For example, a simple blastp analysis of the groups 2 and 3 accessory polypeptide, KpsC, yielded 87/100 non-E. coli ‘hits’ with alignment values <1 × 10−88 in 44 different bacterial species of diverse phylogenetic origins. This result indicates that capsule biosynthesis is likely to be a property of many more bacterial species than currently studied, supporting the overall importance of capsules for mediating interactions with host or environmental surfaces. Understanding the mechanism of group 2 capsule export is thus central to how we think about microbes in diseases resulting from animal and plant infections as well as bacterial social interactions such as biofilm organization. In addition to accessory proteins, it is believed that group 2 polysaccharide synthesis requires a membrane-bound initiator upon which the polysaccharide chain is elongated, and/or a terminator (Fig. 1), which has been variably described, sometimes by the same research group, as phospholipid, phospholipid-linked 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonate (KDO) (Bronner et al., 1993; Finke et al., 1991), ‘endogenous acceptor’ protein, and undecaprenyl phosphate (Troy et al., 1975; Weisgerber & Troy, 1990). The exact nature of the endogenous acceptor and termination event remain outstanding questions for future research.

Fig. 1.

Type I protein and drug efflux exporters (left) compared to group 2 and group 2-like capsular polysaccharide exporters (right). A1–4 indicate accessory proteins and the numbers 1–4 at the far right refer to undecaprenyl phosphate, protein, phospholipid and phospholipid-KDO endogenous acceptors (initiators) or terminators, respectively. Other abbreviations not listed in the text are: OMA, OM auxiliary protein; MPA, membrane–periplasm auxiliary protein; MS and ATPase are the IM-spanning and ATPase modules of the ABC transporter, respectively; OMP?, hypothetical OM protein working in concert with KpsD; P, polymerase. The figure is adapted from Silver et al. (2001). Refer to Fig. 3 legend for colour-coding.

Building blocks – monosaccharide synthesis, activation and polymerization or transfer to acceptors

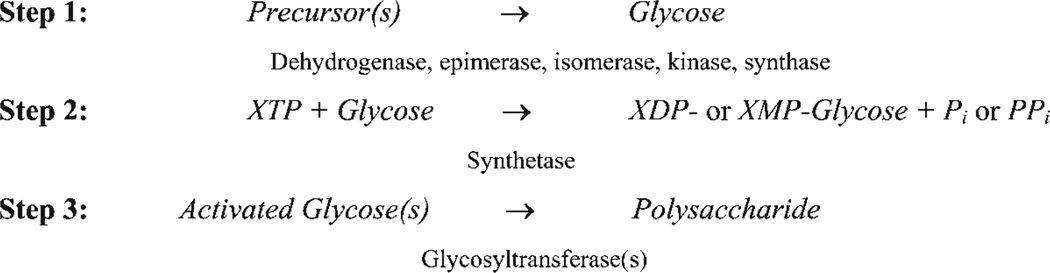

Monosaccharides are EPS building blocks synthesized from simpler precursors by sequentially acting enzymes including at least some of and sometimes more than the catalysts listed in Step 1 of Fig. 2. However, in one prominent case the building block designated sialic acid is acquired directly from the host environment, thereby obviating the need for de novo glycose synthesis (Severi, et al., 2007; Vimr et al., 2004). Once the glycose units have been synthesized or obtained from the environment, activation to mono- or diphosphonucleotide sugars (Step 2), where XTP, XDP and XMP indicate nucleotide (adenosine, cytosine, thymine or uridine) tri-, di- and monophosphonucleotides respectively, primes them for the polymerization step. Synthesis of these ‘high-energy’ nucleotide intermediates is necessary for polymerization catalysed by the glycosyltransferases that transfer glycose units to appropriate acceptors (Step 3). In most cases, polysaccharides are synthesized as part of a glycoconjugate that includes a lipid or protein moiety. These conjugates of polysaccharides with lipids or proteins are the molecular forms finally expressed at the cell surface. Any of the steps involved in synthesis or acquisition of the building blocks or of activation and polymerization of these units are potential targets for inhibiting the expression of capsular polysaccharides. Targeting these steps for therapeutic or vaccine development offers the potential to interfere with or block diverse microbial interactions involved in colonization and disease progression as well as adherence to environmental surfaces (Vimr & Steenbergen, 2006).

Fig. 2.

Summary of the steps involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. See text for details.

Phenotypes of group 2 capsular polysaccharide-export-deficient mutants as they relate to different export models

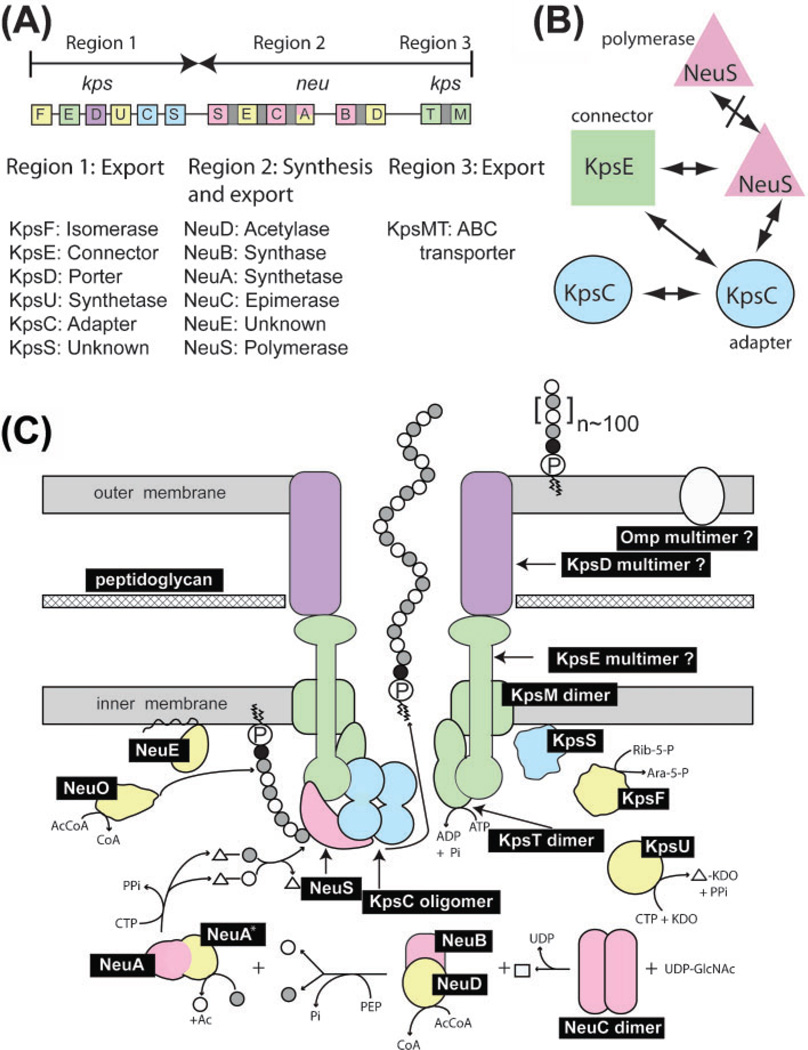

The genes for group 2 and 3 polysaccharide synthesis are organized into functional modules, where region 2 for synthesis is flanked by export genes (regions 1 and 3 comprising the multigenic cluster for biosynthesis of the E. coli K1 capsular polysialic acid) (Fig. 3A). Arrows in Fig. 3(A) indicate modular transcription directions and shaded areas regional gene translational coupling, which presumably ensures synthesis of the precise amounts of each polypeptide required for efficient capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis. The modular organization of E. coli groups 2 and 3 capsules is observed in other encapsulated bacteria such as Campylobacter, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Pasteurella and Actinobacillus spp. (Silver et al., 2001), suggesting a common origin for the biosynthetic gene clusters in these and probably other species that synthesize group 2 or group 2-like capsules. Indeed, Silver and his colleagues indicated that homologues of the E. coli K1 ABC transporter (kpsMT), periplasmic connector (kpsE) and OM pore genes from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis complemented the export defect of an E. coli kpsMTDE quadruple mutant, supporting the conclusion that carbohydrate structure has no major effect on recognition of polysaccharides by the respective translocation machineries (Silver et al., 2001). This observation begs the question: how are group 2 and group 2-like polysaccharides recognized by the exporters?

Fig. 3.

Group 2 capsular polysialic acid biosynthesis in E. coli K1. (A) Genetic and functional organization of the kps–neu gene cluster for polysialic acid biosynthesis adapted from Steenbergen & Vimr (2008); see text for details. (B) Protein–protein interactions between export and synthetic gene products detected by two-hybrid analysis. (C) Model of group 2 capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis. Gene products indicated by black boxes are defined in panel (A) and the text. Open and shaded small circles indicate unacetylated and acetylated sialic acids respectively. The small black circles indicate KDO or unknown moiety while the squiggle-circled P is phosphatidic acid. Triangles indicate CMP; the square is N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc); Ac, acetyl groups; AcCoA and CoA, acetyl coenzyme A and coenzyme A respectively; Rib-5-P, ribulose 5-phosphate; Ara-5-P, d-arabinose 5-phosphate. Other small molecules have their usual abbreviations. Colours indicate essential or non-essential functions as follows: pink, essential synthetic functions; yellow, non-essential synthetic functions in the K1 system; green, essential exporter functions; blue, essential accessory proteins; purple, atypical OM protein found in some but not all group 2 or group 2-like systems. Specific interactions detected by two-hybrid analysis between NeuS, KpsE, and KpsC are indicated by the overlapping shapes. The specific steps in polysialic acid biosynthesis include the following. Step 1, the first committed step, involves the releasing epimerase, NeuC, producing ManNAc. Step 2: ManNAc interacting with the NeuB–NeuD complex is condensed with phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) by NeuB while NeuD transfers an acetyl group to most of the nascent sialic acids. Step 3: the N-terminal domain of the synthetase NeuA activates sialic acid for polymerization by coupling it to CMP donated by CTP. Concomitantly with activation the C-terminal synthetase domain (NeuA*) acts as an O-acetyl esterase to remove the acetyl group from most sialic acid substrates. The functional significance of the cyclical acetylation and deacetylation reactions is not presently understood. Step 4: sialic acid residues are polymerized by NeuS while NeuO in most K1 strains reacetylates the growing chain. Step 5: NeuS, NeuC and NeuE interact such that during or shortly after polymerization the completed polysialic acid is exported through the transmembrane channel to the outer membrane where the phospholipid anchors it to the outer leaflet of the OM.

It is useful to think about group 2-polysaccharide export by focusing on three different potential mechanisms. For example, synthesis could be obligatorily coupled to export such that no polymer is made if the translocator is inactive. Whitfield & Paiment (2003) have reviewed export systems for the LPS-like group 1 capsules, where this feedback mechanism appears to apply. By contrast, defects in group 2 and probably group 3 capsule export result in the intracellular accumulation of polysaccharides that are visualized as electron-transparent lacunae in transmission electron micrographs (Cieslewicz & Vimr, 1996, 1997). The intracellular accumulation of these unexported group 2 polysaccharide pools, observed in regions 1 and 3 and neuE mutants, means that EPS translocation is not obligatory for synthesis, suggesting two additional biosynthetic options. (Note that for the purposes of this mini-review we define biosynthesis as the combined processes of polysaccharide synthesis and export.) First, polysaccharides could be synthesized with a common molecular tag directing them to the export apparatus, a mechanism that would be analogous to the C-terminal secretion signals in polypeptide substrates of type I secretion systems (Thanabalu et al., 1998). Similarly, the polymannans made by E. coli O8 and O9a are synthesized with terminal methyl groups at their non-reducing ends which are recognized by specialized domains of the ATPase components of the ABC transporters, signalling subsequent export (Cuthbertson et al., 2007). The ATPase from each system does not cross-complement, indicating specificity for any particular polysaccharide modification. By contrast, all group 2 and probably group 3 capsules bear a terminal reducing phosphatidic acid moiety that anchors them to the OM and could function as a recognition tag for export because of its commonality and the promiscuous nature of group 2-like exporters already noted above. Recognition of an export signal by promiscuous exporters implies a two-step process where synthesis precedes translocation. In principle, polysaccharides synthesized with export tags could be produced remotely from the translocase. By contrast, another biosynthetic option is that the ABC transporters could be bystanders to polysaccharide export if the glycosyltransferases for polymerization are directed to the exporter by affinity for accessory proteins that in turn interact with the translocator, defining a series of heterotypic polypeptide interactions that would essentially couple synthesis, though not obligatorily, to polysaccharide export. We refer to this last model as directed coupling to distinguish it from the post-synthetic coupling potentially conferred by the phospholipid modification described above (Steenbergen & Vimr, 2008).

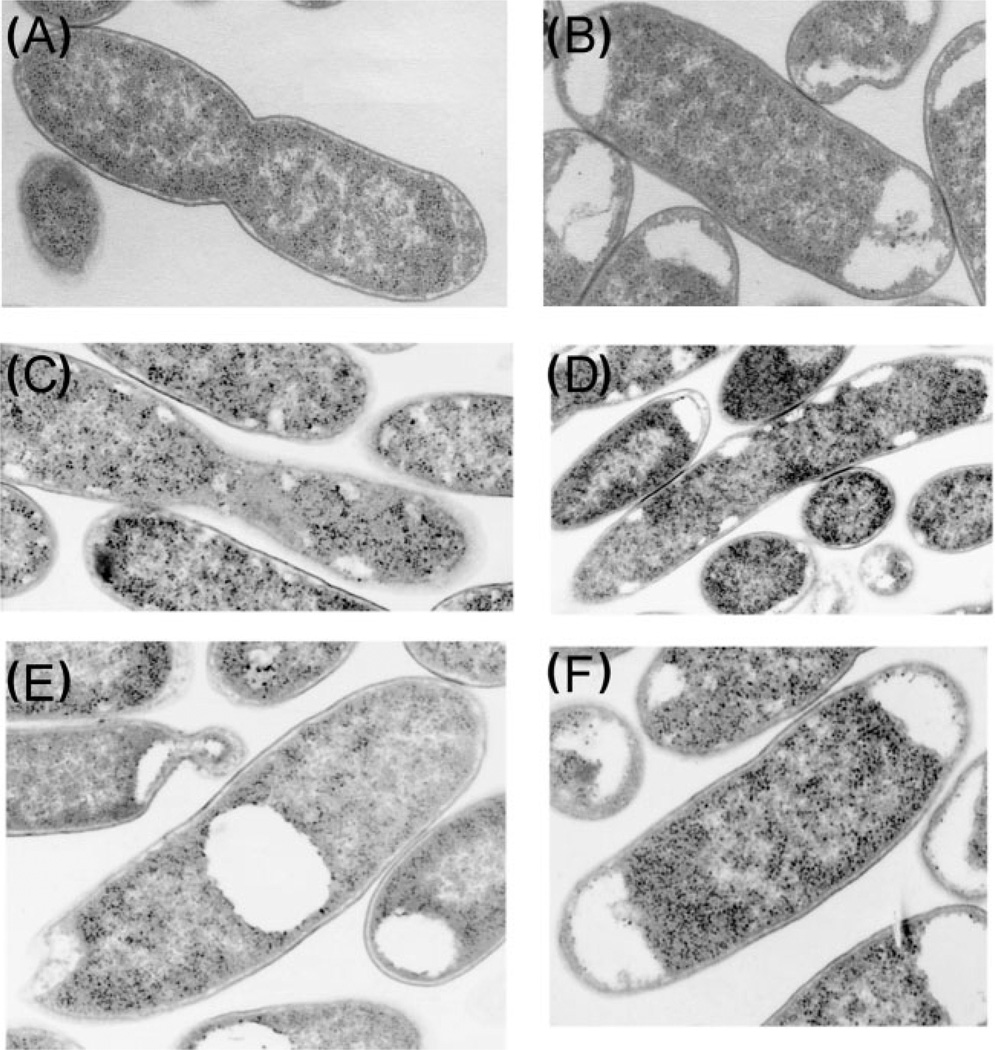

Given the two export models – post-synthetic or directed coupling – a central question in capsule biology is how to distinguish between the two models. One clue came from electron microscopic examination of export-deficient mutants. For example, the phenotype of kpsT and kpsS mutants shown in Fig. 4(C) and (D), respectively, reveals lacunae more or less randomly distributed along the cytoplasmic–IM boundary. No lacunae are observed in the wild-type (Fig. 4A). By contrast, other export-defective mutants, such as those with kpsF, kpsC or kpsE defects (Fig. 4B, E, and F, respectively), accumulate relatively large pools of unexported polysaccharides located centrally or at the poles. Although not all export-defective mutants have been investigated, all of them analysed so far by electron microscopy fall into one or the other phenotypic class of lacunae distribution and size. The simplest interpretation of the dramatic morphological differences is that some export gene products function directly in translocation (as in mutants with peripherally distributed lacunae) while others direct the coupling between synthesis and export (as in mutants with large intracellular pools). On the basis of this interpretation, we hypothesized that KpsC interacts directly with the polymerase (NeuS in the K1 system) and guides it to the periplasmic connector, KpsE, defining a series of molecular-recognition events that might effectively couple synthesis to export by positioning the polymerase near the export channel. By contrast, other components of the system, such as KpsT and KpsS, would function passively in the export process. For example, the ATPase component of the ABC transporter, KpsT, might function mainly to open the KpsE channel to the OM. In other words, while the polymer presumably passes through the IM component, KpsM, of the exporter, it might not necessarily have to pass through the KpsT ATPase component. Despite evidence that KpsS can be chemically cross-linked to most other components of the E. coli K5 biosynthetic system (McNulty et al., 2006), the function of this accessory protein appears to be as a bystander rather than a coupler on the basis of the kpsS mutant phenotype (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Phenotypes of export-deficient acapsular mutants. Thin sections of representative bacteria with the indicated defects in export gene were examined by transmission electron microscopy as previously described by Cieslewicz & Vimr (1996, 1997). Phenotypes and their interpretations are described in the text. (A) Wild-type, where the capsule is not visible due to the fixation procedure, (B) kpsF mutant, (C) kpsT mutant, (D) kpsS mutant, (E) kpsC mutant, and (F) kpsE mutant.

Evidence for directed coupling of group 2 capsular polysaccharide synthesis to the translocation apparatus

Previous studies of group 2 polysaccharide biosynthesis have used immunological, chemical cross-linking and radiation target analysis methods to confirm that accessory proteins and the kpsMTED exporter channel were likely to interact heterotypically with synthetic components such as the polymerases (Andreischeva & Vann, 2006; McNulty et al., 2006; Vionnet et al., 2006). However, these studies provided no coherent model for thinking about the early biosynthetic events coupling polysaccharide synthesis to the exporter, or even if there was coupling between the processes. In an attempt to distinguish between the post-synthetic and directed coupling models discussed above, we used expression of recombinant polysialic acid depolymerase to determine whether cytoplasmic synthesis of the polysaccharide was protected from degradation. In essence, this in vivo protection assay assessed the relative intimacy of the relation between synthesis and export. The depolymerase, which functions by an endo-hydrolytic mechanism, would clip nascent chains prior to export, thus reducing or eliminating surface capsule expression. However, if the molecular associations involved in synthesis and export are intimate, the polysaccharide would be protected and the capsule expressed regardless of depolymerase. The results indicated that capsular polysialic acid synthesis was protected during polymerization and export, supporting the directed coupling model. This conclusion was supported by a series of control experiments showing that any cytoplasmic intermediates would have been susceptible to the depolymerase in vivo, establishing the in vivo protection assay as a novel method for investigating group 2 capsule biosynthesis (Steenbergen & Vimr, 2008).

Two-hybrid analysis of homo- and heterotypic interactions in group 2 capsule biosynthesis

Most two-hybrid systems for detecting protein or peptide interactions rely on activation of various transcriptional regulators to provide the reporter activity. By contrast, reconstituting the N- and C-terminal domains of the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase (Cya) through interacting homo- or heterotypic fusions results in cyclic AMP synthesis and activation of E. coli catabolite-activator-protein-dependent genes such as those for maltose and β-galactosidase utilization (Karimova et al., 1998). Thus, as long as the reporter strain lacks its own cya, activation is solely dependent on reconstituting the B. pertussis fragments through proximity mediated by the interacting fusion partners. The salient feature of this system for analysing bacterial multi-protein membrane assemblies is that the signalling cascade is spatially separated from the transcriptional reporter. For example, Landant and colleagues have provided evidence that the E. coli cell division apparatus involves multiple low-affinity interactions analogous to formation of the eukaryotic synapse (Karimova et al., 2005). Using this two-hybrid system, we analysed a variety of protein–protein interactions using plasmids expressing combinations of kps–kps, kps–neu and neu–neu fusions (Steenbergen & Vimr, 2008). The conclusions shown in Fig. 3(B) indicate that the polymerase functions as a monomer, consistent with radiation target analysis (Vionnet et al., 2006), but has affinity for both the IM–OM KpsE connector and the KpsC adaptor, which also interacts with itself. Note that the adaptor function of KpsC is used in the sense that it alters (adapts) the polymerase in some as yet unknown way so that polymerization is coupled to the exporter. In the absence of the adaptor, any group 2 polymer synthesized cannot be exported. If these interactions are interpreted correctly, they imply that positioning of group 2 polysaccharide synthetic functions relative to the export channel occurs through heterotypic interactions, possibly explaining the promiscuous nature of group 2-like polysaccharide export systems (Silver et al., 2001). This hypothesis implies that the polymerases in different group 2 systems include conserved regions mediating the various interactions. It may be possible to identify these regions with the current two-hybrid system through mutation or by making peptide fusions, but ultimately crystal structures may be necessary if the interacting domains are strictly dependent on tertiary folding.

Model of group 2 capsular polysialic acid biosynthesis in E. coli K1 and summary of outstanding questions concerning the dynamics of capsule export

Although the details of building block assembly in the K1 system have been worked out for some time (Vimr et al., 2004), since 2004 a series of previously unidentified acetyl transferases and O-acetyl esterases have been discovered that modify the polysialic acid chain or its precursors before or during export (Steenbergen et al., 2006). However, acetylation modifies structure without affecting export. These modifications of the polysaccharide or its precursors suggest that the synthetic components of group 2 capsule biosynthesis may themselves be associated with the IM, and indeed the bifunctional NeuD protein has been shown to interact physically with NeuB and to exist in an IM-bound configuration (Annunziato et al., 1995; Daines & Silver, 2000). Thus, all of the synthetic and export functions required for capsule biosynthesis might be interacting in a super-complex that we have designated the sialisome (Steenbergen & Vimr, 2008). It remains to be determined if the spatial organization of any synthetic proteins operating prior to the polymerase, NeuS, has a direct impact on export. Fig. 3(C) shows the synthetic steps involved in building-block synthesis, assembly and modification of the K1 capsule, and the homo- and heterotypic interactions between NeuS, KpsC and KpsE described above connecting synthesis to the export channel.

Are there any other gene products besides those shown in Fig. 3(C) that affect group 2 capsular polysaccharide export? McNulty et al. (2006) and Silver et al. (2001) provided evidence that RhsA and TolC, respectively, affected capsule synthesis or export. In particular, RhsA was suggested to be a carbohydrate-binding protein that could be chemically cross-linked to other components of the export channel and might connect capsule synthesis to export. However, it is difficult to rule out pleiotropic effects on membrane architecture as the explanation for RhsA or TolC phenotypes, especially since polypeptides such as GlgB and SucA involved in entirely separate pathways were also found cross-linked to the E. coli K5 export apparatus (McNulty et al., 2006). Despite these outstanding questions and experimental ambiguities it would be useful to probe the export channel by cross-linking nascent capsular polysaccharide to protein components of the channel. It might be possible to approach this question by using a synchronized biosynthetic system making radiolabelled polysaccharide followed by cross-linking the carboxyl groups of nascent polysialic acid to adjacent amino groups in the channel. Such a synchronized system has been developed (Vimr, 1992) and already used to determine the extracellular structure of polysialic acid by NMR (Azurmendi et al., 2007). Unfortunately, even if three-dimensional structures of group 2 export components were to become available, as in the group 1 system (Whitfield & Naismith, 2008), it is unlikely that static images of the components would tell us much new about the outstanding questions raised above regarding the dynamics of polysaccharide biosynthesis. We think that the two-hybrid system described above, and continued genetic manipulation of capsule genes coupled with simple biochemical and cell physiological approaches, will allow researchers to accurately infer the dynamics of group 2 capsule export.

While a complete in vitro reconstitution of the export process appears impossible at this time, our current understanding of the minimum set of components required for translocation suggests that progress might be made in the near future. In conclusion, there have been three fundamental questions in group 2 capsule biosynthesis. First, how is polysaccharide synthesis initiated/terminated? Second, is the coupling of synthesis to export directed or does it involve a potential cytoplasmic intermediate? Third, how is polysaccharide recognized by the export apparatus? While an answer to the first question remains mysterious, the second clearly involves directed coupling mediated by heterotypic protein–protein interactions (Steenbergen & Vimr, 2008). Finally, given the immense structural polysaccharide diversity, export seems to require a signal that would presumably reside in the linkage to the terminal phospholipid moiety or that is the only common feature in different systems. However, our results provide an alternative explanation: the juxtapositioning of the polymerase through heterotypic protein–protein interactions might be sufficient to couple synthesis to export without the need for a specific export signal.

Acknowledgements

Research from the authors’ laboratory was supported by NIH grant AI042015. The authors are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for expert comments and suggestions.

References

- Andreischeva EN, Vann WF. Gene products required for de novo synthesis of polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:1786–1797. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1786-1797.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato PW, Wright LF, Vann WF, Silver RP. Nucleotide sequence and genetic analysis of the neuD and neuB genes in region 2 of the polysialic acid gene cluster of Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:312–319. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.312-319.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azurmendi HF, Vionnet J, Wrightson L, Trinh LB, Shiloach J, Freedberg DI. Extracellular structure of polysialic acid explored by on cell solution NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11557–11561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704404104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos MP, Robert V, Tommassen J. Biogenesis of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner D, Sieberth V, Pazzanik C, Roberts IS, Boulnois G, Jann B, Jann K. Expression of the capsular K5 polysaccharide of Escherichia coli: biochemical and electron microscopic analyses of mutants with defects in region 1 of the K5 gene cluster. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5984–5992. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5984-5992.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslewicz M, Vimr E. Thermoregulation of kpsF, the first region 1 gene in the kps locus for polysialic acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3212–3220. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3212-3220.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslewicz M, Vimr E. Reduced polysialic acid capsule expression in Escherichia coli K1 mutants with chromosomal defects in kpsF. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:237–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5651942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson L, Kimber MS, Whitfield C. Substrate binding by a bacterial ABC transporter involved in polysaccharide export. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19529–19534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705709104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daines DA, Silver RP. Evidence for multimerization of Neu proteins involved in polysialic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli K1 using improved LexA-based vectors. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5267–5270. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.18.5267-5270.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke A, Bronner D, Nikolaev AV, Jann B, Jann K. Biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli K5 polysaccharide, a representative of group II capsular polysaccharides: polymerization in vitro and characterization of the product. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4088–4094. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4088-4094.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jann K, Jann B. Polysaccharide antigens of Escherichia coli. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:S517–S526. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.supplement_5.s517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5752–5756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G, Dautin N, Ladant D. Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2233–2243. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2233-2243.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty C, Thompson J, Barrett B, Lord L, Anderson C, Roberts IA. The cell surface expression of group 2 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli: the role of KpsD, RhsA and a multi-protein complex at the pole of the cell. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:907–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørskov I, Ørskov F, Jann B, Jann K. Serology, chemistry, and genetics of O and K antigens of Escherichia coli. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:667–710. doi: 10.1128/br.41.3.667-710.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severi E, Hood DW, Thomas GH. Sialic acid utilization by bacterial pathogens. Microbiology. 2007;153:2817–2822. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RP, Prior K, Nsahlai C, Wright LF. ABC transporters and the export of capsular polysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen SM, Vimr ER. Biosynthesis of the Escherichia coli K1 group 2 polysialic acid capsule occurs within a protected cytoplasmic compartment. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:1252–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen SM, Lee YC, Vann WF, Vionnet J, Wright LF, Vimr ER. Separate pathways for O acetylation of polymeric and monomeric sialic acids and identification of sialyl O-acetyl esterase in Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6195–6206. doi: 10.1128/JB.00466-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanabalu T, Koronakis E, Hughes C, Koronakis V. Substrate-induced assembly of a contiguous channel for protein export from E. coli: reversible bridging of an inner-membrane translocase to an outer membrane exit pore. EMBO J. 1998;17:6487–6496. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy FA, Vijay IK, Tesche N. Role of undecaprenyl phosphate in synthesis of polymers containing sialic acid in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vimr ER. Selective synthesis and labeling of the polysialic acid capsule in Escherichia coli K1 strains with mutations in nanA and neuB. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6191–6197. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.19.6191-6197.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vimr ER, Steenbergen SM. Targeting microbial sialic acid metabolism for new drug development. In: Bewley CA, editor. Protein–Carbohydrate Interactions in Infectious Disease. London, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2006. pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Vimr ER, Kalivoda KA, Deszo EL, Steenbergen SM. Diversity of microbial sialic acid metabolism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:132–153. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.132-153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vionnet J, Kempner ES, Vann WF. Functional molecular mass of Escherichia coli K92 polysialyltransferase as determined by radiation target analysis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13511–13516. doi: 10.1021/bi061486k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH, DeAngelis PL. Hyaluronan synthases: a decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36777–36781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisgerber C, Troy FA. Biosynthesis of the polysialic acid capsule in Escherichia coli K1. The endogenous acceptor of polysialic acid is a membrane protein of 20 kDa. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1578–1587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:39–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C, Naismith JH. Periplasmic export machines for outer membrane assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield C, Paiment A. Biosynthesis and assembly of group 1 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli and related extracellular polysaccharides in other bacteria. Carbohydr Res. 2003;338:2491–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]