Abstract

The uncharacterized protein Rsp3690 from Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily of enzymes. In this investigation the gene for Rsp3690 was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity, and the three-dimensional structure was determined to a resolution of 1.8 Å. The protein folds as a distorted (β/α)8-barrel, and the subunits associate as a homotetramer. The active site is localized to the C-terminal end of the β-barrel and is highlighted by the formation of a binuclear metal center with two manganese ions that are bridged by Glu-175 and hydroxide. The remaining ligands to the metal center include His-32, His-34, His-207, His-236, and Asp-302. Rsp3690 was shown to catalyze the hydrolysis of a wide variety of carboxylate esters, in addition to organophosphate and organophosphonate esters. The best carboxylate ester substrates identified for Rsp3690 included 2-naphthyl acetate (kcat/Km = 1.0 × 105 M–1 s–1), 2-naphthyl propionate (kcat/Km = 1.5 × 105 M–1 s–1), 1-naphthyl acetate (kcat/Km = 7.5 × 103 M–1 s–1), 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate (kcat/Km = 2.7 × 103 M–1 s–1), 4-nitrophenyl acetate (kcat/Km = 2.3 × 105 M–1 s–1), and 4-nitrophenyl butyrate (kcat/Km = 8.8 × 105 M–1 s–1). The best organophosphonate ester substrates included ethyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate (kcat/Km = 3.8 × 105 M–1 s–1) and isobutyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate (kcat/Km = 1.1 × 104 M–1 s–1). The (SP)-enantiomer of isobutyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate was hydrolyzed 10 times faster than the less toxic (RP)-enantiomer. The high inherent catalytic activity of Rsp3690 for the hydrolysis of the toxic enantiomer of methylphosphonate esters make this enzyme an attractive target for directed evolution investigations.

The amidohydrolase superfamily (AHS) was first identified by Holm and Sander on the basis of the three-dimensional structural similarity of phosphotriesterase, adenosine deaminase, and urease.1 Since its discovery in 1997, more than 23,000 proteins have been identified as members of this superfamily. Proteins in the AHS fold as a distorted (β/α)8-barrel and, in most cases, contain a metal center embedded at the C-terminal end of the β-barrel with conserved metal binding and catalytic residues originating from the ends of β-strands 1, 4, 5, 6, and 8.2 The AHS is an ensemble of evolutionarily related enzymes capable of catalyzing a diverse set of chemical reactions, including the hydrolysis of amide or ester bonds, deamination of nucleic acids, decarboxylation, isomerization, and hydration reactions.2

The NCBI has classified proteins from completely sequenced bacterial genomes that perform the same or similar functions into Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG). Within the AHS, there are 24 identifiable COGs. For this investigation we have focused on the identification of unknown proteins contained within cog1735. Sequence similarity networks (SSNs) for cog1735 at BLAST E-value cutoffs of 10–70 and 10–40 are presented in Figure 1 for approximately 450 proteins.3 In this figure the groups of proteins have been arbitrarily numbered and color-coded. Enzymes from this COG have previously been found to catalyze the hydrolysis of organophosphate triesters,4,5 homoserine lactones,6−8 γ- and δ-lactones,9 phosphorylated sugar lactones,10 and carboxylate esters.11

Figure 1.

Cytoscape sequence similarity network representation (http://www.cytoscape.org) of cog1735 from the amidohydrolase superfamily obtained at E-value cutoffs of 10–70 (left) and 10–40 (right). Each node in the network represents a single sequence, and each edge (depicted as a line) represents the pairwise connection between two sequences at the given BLAST E-value. Lengths of edges are not significant except that sequences in tightly clustered groups are more similar to each other than sequences with fewer connections. The triangular nodes represent proteins that have been functionally and/or structurally characterized. Additional information is presented in the text.

Two bacterial phosphotriesterases (PTE) from Pseudomonas diminuta and Agrobacterium radiobacter have been characterized from Group 8. These enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of organophosphates, including the insecticide paraoxon and the chemical warfare agents GB, GD, and VX.4,5 Sso2522 from the hyperthermophlic Sulfolobus solfataricus belongs to Group 9, and this enzyme has a very weak phosphotriesterase activity but hydrolyzes lactones at significantly faster rates.12 Three proteins from Group 3, Mt0240 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rer55000 from Rhodococcus erythropolis, and MAP3668c from Mycobacterium avium, catalyze the hydrolysis of N-acyl homeserine lactones.6−8 A thermostable lactonase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus (gi|258588268) from Group 7 (PDB id: 3F4D) exhibits both phosphotriesterase and lactonase activities.13 The three-dimensional structure and substrate profile of Dr0930 from Deinococcus radiodurans from Group 7 have been determined (PDB id: 3FDK and 3HTW). This protein has very low phosphotriesterase activity but efficiently hydrolyzes alkyl-substituted δ- and γ-lactones.9,14 Recently, two proteins, Lmo2620 from Listeria monocytogenes (PDB id: 3PNZ) and Bh0225 from Bacillus halodurans, from Group 5 were shown to catalyze the hydrolysis of d-lyxono-1,4-lactone-5-phosphate and l-ribono-1,4-lactone-5-phosphate.10

Thus, far, enzymes from Groups 1, 2, 4, and 6 have not been fully functionally characterized, although the three-dimensional structures for some proteins have been determined. For example, the PTE homology protein (PHP, b3379) from Escherichia coli K12 (PDB id: 1BF6) of Group 1 and Pmi1525 (PDB id: 3RHG) from Proteus mirabilis of Group 2 have been structurally characterized, but the catalytic functions of these two proteins remain undetermined.15 In addition, the structure of Ms0025 from Mycoplasma synoviae (PDB id: 3OVG) of Group 6 has been determined, but the substrate profile has not. Here we report the three-dimensional structure of Rsp3690 from Rhodobacter sphaeroides from Group 4 and demonstrate that it efficiently catalyzes the hydrolysis of carboxylate and organophosphonate esters.

Materials and Methods

Materials

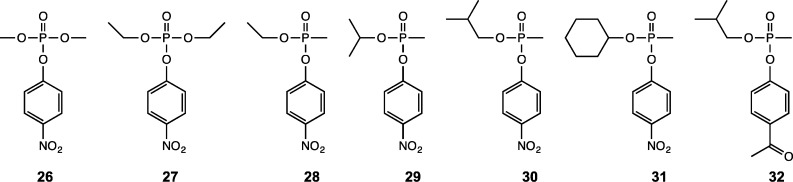

LB broth was purchased from Tpi Research Products International Corp. The HisTrap and gel filtration columns were purchased from GE Healthcare. E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells were obtained from Stratagene. Standards for ICP-MS were purchased from Inorganic Ventures Inc. All other buffers, purification reagents, and chemicals used in this work were purchased from Sigma/Aldrich, unless otherwise stated. Compounds 26–31 were synthesized as racemic mixtures as previously described.16 The (RP)- and (SP)-enantiomers of compound 32 were isolated according to published procedures.16

Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis

The plasmid containing the gene for Rsp3690 from Rhodobacter sphaeroides (gi|77465698) was obtained from NYSGXRC (New York SGX Research Consortium). The mutant E175K was constructed using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis method from Agilent. The primer pair used in the PCR amplification of the E175K mutant was 5′-cgggtgatcggcaagatcggcgtttcctc-3′ and 5′-gaggaaacgccgatcttgccgatcagcccg-3′.

Purification of Rsp3690

The plasmid encoding the gene for Rsp3690 was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells. A 5 mL culture of LB was inoculated with a single colony from this transformation, incubated overnight, and then used to inoculate 1 L of LB in the presence of 50 μg mL–1 kanamycin. The culture was grown with agitation at 30 °C to an OD600 of 0.1–0.2. At this point 100 μM of 2,2′-bipyridyl was added to reduce the incorporation of iron in the expressed protein,17 and the culture was then allowed to grow to an OD600 of 0.6. At this point, the culture was supplemented with 1.0 mM Zn(OAc)2 (or MnCl2) and 0.5 mM isopropyl thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) and then allowed to grow at room temperature for 16 h. The cell pellet was harvested by centrifugation and then stored at −70 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole). The suspension was lysed by sonication at 0 °C for 30 min, and then the insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation. The clarified cell extract was filtered with a 0.2 μm syringe filter (VWR) and loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap HP column, which was connected to an ÄKTA purifier (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) previously calibrated with binding buffer. The column was washed thoroughly with binding buffer, and then the target protein was eluted with a linear gradient of elution buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 0.25 M NaCl, and 0.5 M imidazole). The protein was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a GE Healthcare Hiload 16/60 Superdex 200 prep grade column that was precalibrated with 50 mM Hepes, pH 8.0. The mutant E175K was expressed in the presence of 1.0 mM MnCl2 or CdCl2 and purified to homogeneity using the same procedure as for the wild-type enzyme.

Metal Analysis

The protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm in a 1 cm quartz cuvette using a SPECTRAmax-340 UV–vis spectrophotometer. The extinction coefficient at 280 nm used for determining the concentration of Rsp3690 was calculated to be 28,795 M–1 cm–1 (http://ca.expasy.org/tools/protparam.html). The metal content of the purified protein was determined using inductively coupled plasma emission mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Before ICP-MS measurements, the protein samples were digested with concentrated nitric acid by refluxing for ∼30 min and then diluted with distilled H2O until the final concentration of the nitric acid was 1% (v/v) and the protein concentration was ∼1.0 μM.

Kinetic Measurements and Data Analysis

Activity screening and kinetic measurements were performed using a SPECTRAmax-340 plate reader. The hydrolysis of most carboxylate esters was monitored using a pH-sensitive colorimetric assay. Protons released from the hydrolysis reaction were measured using the pH indicator cresol purple.9,18 The reactions were performed in 2.5 mM Bicine buffer, pH 8.3, containing 0.2 M NaCl, various concentrations of substrate, 0.1 mM cresol purple, and enzyme. The final concentration of DMSO in the reaction was 2% or 5%, depending on the solubility of the substrate. The change in absorbance was monitored at 577 nm.9 The effective extinction coefficient (ΔOD/M of H+) was obtained from a titration with acetic acid at pH 8.3, 30 °C (ε = 1.76 × 103 M–1 cm–1, 2% DMSO; ε = 1.68 × 103 M–1 cm–1, 5% DMSO).

The as-purified Rsp3690 was buffer-exchanged to contain 10 mM Bicine, pH 8.3, using a PD-10 desalting column. The carboxylate ester substrates were dissolved in DMSO (100 mM) and then diluted into the reaction mixture. In the absence of substrate, a background rate was observed due to the acidification by atmospheric CO2. The background rate was independent of the substrate concentration and subtracted from the initial rates of the enzymatic reactions.9 For substrates with 4-nitrophenol as the leaving group, activity screening and kinetic measurements were monitored at 400 nm (ε = 1.7 × 104 M–1 cm–1), while for substrates with 4-acetylphenol as the leaving group, the reactions were monitored at 294 nm (ε = 7710 M–1 cm–1).16 For the compounds 4′-chloroacetanilide and 3-acetoxypyridine, the acetic acid assay kit from Megazyme was used and the reaction was monitored at 340 nm (ε340 = 6,220 M–1 cm–1). When indoxyl acetate was used as a substrate, the hydrolysis product was monitored at 678 nm in 50 mM Hepes buffer, pH 8.3, 1% ethanol (ε = 7.0 × 103 M–1 cm–1).

Kinetic parameters were determined by fitting the initial rates to eq 1 using the nonlinear least-squares fitting program in SigmaPlot 9.0, where ν is the initial velocity of the reaction, Et is the enzyme concentration, kcat is the turnover number, [A] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis constant:

| 1 |

Crystallization and X-ray Data Collection

The selenomethionine (SeMet) derivative of Rsp3690 with a 6x-His tag was crystallized at room temperature by the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Diffraction quality crystals were grown by mixing 1 μL of protein with 1 μL of reservoir solution and equilibrating the protein sample against the corresponding reservoir solution. The protein sample was in a buffer of 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM methionine, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM DTT at a concentration of 10 mg mL–1. The reservoir solution contained 25% PEG 3350, 0.2 M MgCl2, and 0.1 M Tris, pH 8.5. Crystals appeared after 2 days and were flash-cooled by direct immersion in liquid nitrogen using the mother liquor supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol. A complete SAD data set from a single SeMet crystal was collected at the selenium absorption edge (λ = 0.979 Å) under standard cryogenic conditions on beamline X29A at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), Brookhaven National Laboratory. Crystals diffracted to 1.8 Å and belong to the C centered monoclinic space group C2 with 4 molecules in the asymmetric unit. Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the program HKL2000.19 Crystal parameters, data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Data Collection and Refinement Statistics.

| cell dimensions | a = 179.7 Å, b = 47.4 Å, c = 188.9 Å |

| α = 90°, β = 108.3°, γ = 90° | |

| space group | C2 |

| data collection statisticsa | |

| resolution limit (Å) | 50–1.8 (1.86–1.8) |

| unique reflections | 127592 (7765) |

| completeness (%) | 90.7 (55.7) |

| Rmergeb (%) | 9.7 (30.0) |

| ⟨I/(σI)⟩ | 19.1 (2.0) |

| phasing statistics | |

| correlation coefficient (CC)c | 73.9 |

| FOMd after density modification | 0.68 |

| refinement statistics | |

| no. of protein atoms | 11 070 |

| no. of ligand atoms | 41 |

| no. of solvent atoms | 872 |

| R factore (%) | 20.4 |

| Rfree (%) | 22.5 |

| mean B-factors (Å2) | 21.9 |

| root mean square deviations | |

| bond distance (Å) | 0.006 |

| bond angles (deg) | 1.4 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |

| residues in core regions | 88.7 |

| residues in additionally allowed regions | 10.9 |

Values for the highest resolution shell are given within parentheses.

Rmerge = ∑hkl∑j|Ij(hkl) – ⟨I(hkl)⟩|/∑hkl∑jIj(hkl), where <I(hkl)> is the average intensity over symmetry equivalents.

Correlation Coefficient and as defined in SHELXE.

FOM (figure of merit) as defined in SHELXE.

R factor = ∑hkl||Fobs| – |Fcalc||/∑hkl|Fobs|.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The selenium substructure was determined using SHELXD.20 The phase refinement and density modifications were carried out using SHELXE.21 Model building was done using ARP/wARP.22 Further model building and refinement of the structure was carried out in iterative cycles using the program O and CNS 1.1.23,24 Well-defined residual electron density was observed in all four molecules and could be modeled as DTT, which was added previously in the sample buffer. In addition, two metal ions were located per molecule and included in the later stages of refinement. On the basis of the electron density (peak height) and coordination geometry, these two metal ions were modeled as zinc. The quality of the final structure was verified with a composite omit map, and stereochemistry was checked with the program PROCHECK.25 The atomic coordinates and structure factors for Rsp3690 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 3k2g.

Results

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Rsp3690

The gene for Rsp3690 was cloned and expressed as a C-terminal His-tagged protein. Rsp3690 expressed well in E. coli after induction with IPTG in the presence of added divalent metal ions (Zn(Ac)2 or MnCl2). The His-tagged protein was purified using a combination of gel filtration and HisTrapHP column chromatography. The purity of the isolated protein was estimated to be >95% as judged by SDS gel electrophoresis. The enzyme, expressed in the presence of Zn(OAc)2 in the growth medium, contained 1.5 equiv of zinc and 0.4 equiv of iron per subunit. The concentrated protein was purple in color and has an absorbance maximum at 530 nm. The protein expressed in the presence of MnCl2 and 100 μM 2.2′-bipyridal contained 1.0 equiv of manganese, 0.1 equiv of zinc, and 0.3 equiv of iron and was also purple at high protein concentrations. The purified E175K mutant expressed in the presence of MnCl2 contained 0.5 equiv of zinc, 0.1 equiv of iron, and 0.1 equiv of manganese.

Three-Dimensional Structure of Rsp3690

The three-dimensional structure of Rsp3690 was determined to a resolution of 1.8 Å with a homotetramer in the asymmetric unit (Figure 2). The protein folds as a distorted (β/α)8-barrel with N-terminal and C-terminal extensions from both sides of the barrel. The following chain segments are included in the eight β-strands of the barrel: β-1 (residues 29–34), β-2 (residues 100–103), β-3 (residues 126–129), β-4 (residues 173–176), β-5 (residues 204–206), β-6 (residues 232–234), β-7 (residues 256–259), and β-8 (residues 297–299). There are two long helical segments between strands β-1 and β-2 and between β-3 and β-4 of the barrel. The long segment between strands β-1and β-2 protrudes out from one side of the active site and covers part of the substrate entrance to the active site. The ribbon representation of a single subunit is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Ribbon representation of the Rsp3690 tetramer, with distinct protomers shown in green, yellow, cyan, and magenta. This figure was prepared with PYMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

Figure 3.

Ribbon representation of subunit A of Rsp3690. The eight β-strands of the β-barrel are colored blue. The two metal atoms in the active site are colored green. The long helical segment between β-1 and β-2 (colored red) protrudes out from one side of the protein and covers part of the entrance to the active site. The loop between β-7 and α-8 (colored purple) extends away from the protein and also covers part of the entrance to the active site. The helical segment between β-3 and β-4 is colored orange.

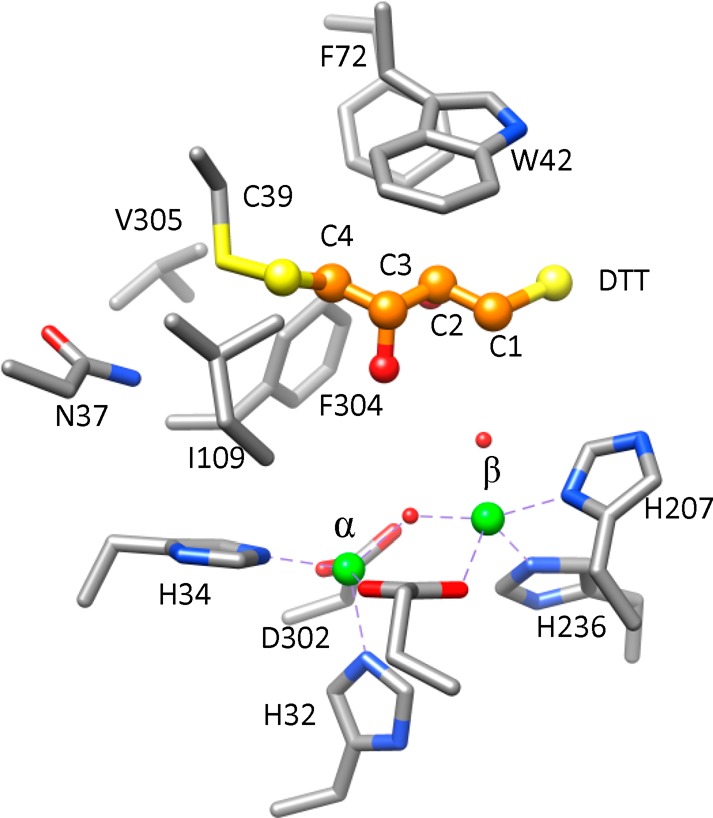

The active site is located at the C-terminal end of the β-barrel and is open to bulk solvent. Two metal ions are bound in the active site, and the coordination geometry is illustrated in Figure 4. The most deeply buried and most solvent-exposed metal ions are denoted as α and β, respectively. The α-metal ion is coordinated by His-32 and His-34 from strand β-1, Asp-302 from strand β-8, and Glu-175 from strand β-4. The β-metal ion is coordinated by His-207 from strand β-5, His-236 from strand β-6, the bridging carboxylate from Glu-175, and a water molecule. A second water molecule (or hydroxide) serves as an additional bridging ligand between the two metal ions. The interatomic distance between the two metal ions is 3.6 Å, and the distance to the bridging water/hydroxide is 2.0–2.1 Å. The phenolic oxygen of Tyr-134 is 2.7 Å from the β-zinc. This interaction is assumed to be responsible for the absorbance at 530 nm from the formation of a change transfer complex.

Figure 4.

Coordination geometry of the metal center in the active site of Rsp3690. The α-metal ion and the β-metal ion are shown as green spheres, and the bridging water molecule and the water coordinated to the β-metal ion are shown as red spheres.

Interestingly, the structure of Rsp3690 was found with a molecule of DTT bound in the active site. The DTT molecule was presumably captured from the purification buffer or the crystallization solution and formed a disulfide bond with Cys-39 as illustrated in Figure 5. The six residues found within 6 Å of DTT included Asn-37, Trp-42, Phe-72, Ile-109, Phe-304, and Val-305.

Figure 5.

Positioning of DTT in the active site of Rsp3690. DTT is depicted in a ball and stick format where the carbon atoms are orange, sulfur atoms are yellow, and the oxygen atoms are red.

Function Determination of Rsp3690

Rsp3690 from R. sphaeroides belongs to Group 4 of cog1735 in the amidohydrolase superfamily, and very little functional information is available for close relatives of this enzyme. In the databases maintained by NCBI, it is listed as a resiniferatoxin-binding protein. To determine the substrate profile of Rsp3690, this protein was tested with organophosphate esters, lactones, carboxylate esters, and peptide libraries. None of the lactones or peptides tested was found to be a substrate for this enzyme, but Rsp3690 did catalyze the hydrolysis of paraoxon (27) and 4-nitrophenyl acetate (5). The Mn-containing Rsp3690 exhibited significantly higher activity relative to that of the Zn-containing protein. When ZnCl2 was added to the reaction mixture of the Zn-containing enzyme, the reaction rate decreased as the Zn concentration increased. The enzyme lost all catalytic activity when the Zn concentration was increased to 0.5 mM. When MnCl2 was added to the reaction mixture of the Zn- or Mn-containing proteins, the reaction rate increased significantly up to a maximum at ∼400 μM MnCl2. Higher concentrations of MnCl2 did not further increase the reaction rate. The Mn-containing enzyme was used throughout the substrate screening assays, and kinetic measurements were supplemented with 400 μM MnCl2.

Since the phosphotriesterase from Pseudomonas diminuta has very low but detectable activity with 2-naphthyl acetate (8), Rsp3690 was assayed with this compound and found to hydrolyze this substrate with a kcat/Km of ∼105 M–1 s–1. On the basis of this result, Rsp3690 was further screened with a variety of carboxylate esters. The kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of organophosphate and carboxylate esters are presented in Table 2. The structures of these compounds are presented in Schemes 1 and 2.

Table 2. Kinetic Parameters for Rsp3690a,b.

| substrate | compound | kcat (s–1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (M–1 s–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | phenyl acetate | 30 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 104 |

| 2 | 4-methylbenzyl acetate | 47 ± 2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | (3.8 ± 0.3) × 104 |

| 3 | 4-hydroxylphenyl acetate | (4.1 ± 0.1) × 102 | ||

| 4 | 1,4-diacetoxybenzene | 108 ± 4 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 105 |

| 5 | 4-nitrophenyl acetate | 120 ± 3 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | (2.3 ± 0.2) × 105 |

| 6 | benzyl acetate | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | (1.6 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 7 | 2-phenethyl acetate | (2.5 ± 0.1) × 102 | ||

| 8 | 2-naphthyl acetate | 40 ± 2 | 0.40 ± 0.04 | (1.0 ± 0.1) × 105 |

| 9 | 1-naphthyl acetate | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | (7.5 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 10 | 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | (2.7 ± 0.2) × 103 |

| 11 | 3-acetoxypyridine | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | (2.4 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| 12 | indoxyl acetate | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 13 | 4′-chloroacetanilide | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | (6.3 ± 0.7) × 101 |

| 14 | 4-nitroacetanilide | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | (5.5 ± 0.6) × 102 |

| 15 | β-thionaphthyl acetate | (4.7 ± 0.2) × 102 | ||

| 16 | 2-naphthyl propionate | 83 ± 2 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | (1.5 ± 0.1) × 105 |

| 17 | 4-nitrophenyl butyrate | 50 ± 1 | 0.056 ± 0.003 | (8.8 ± 0.4) × 105 |

| 18 | 1-naphthyl butyrate | 9 ± 1 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | (5.0 ± 0.6) × 104 |

| 19 | 4-methylumbelliferyl butyrate | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | (3.1 ± 0.4) × 104 |

| 20 | ethyl 4-nitrophenyl acetate | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | (4.3 ± 0.4) × 103 |

| 21 | 4-nitrophenyl hexanoate | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 0.048 ± 0.005 | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 105 |

| 22 | 4-methylumbelliferyl heptanoate | 0.063 ± 0.001 | 0.024 ± 0.003 | (2.6 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| 23 | 4-nitrophenyl octanoate | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.033 ± 0.004 | (1.5 ± 0.2) × 104 |

| 24 | ethyl 2-naphthyl acetate | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.62 ± 0.06 | (2.8 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| 25 | ethyl buryrylacetate | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | (2.4 ± 0.1) × 103 |

| 26 | methyl paraoxon | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | (5.0 ± 0.5) × 103 |

| 27 | paraoxon | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | (1.2 ± 0.1) × 104 |

| 28 | ethyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate | 84 ± 3 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | (3.8 ± 0.4) × 105 |

| 29 | isopropyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | (2.6 ± 0.3) × 103 |

| 30 | isobutyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 0.70 ± 0.09 | (1.1 ± 0.1) × 104 |

| 31 | cyclohexyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate | (2.1 ± 0.1) × 102 |

Assays were conducted at pH 8.3 and 30 °C.

Compounds 28–31 were used as racemic mixtures.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

Rsp3690 is a promiscuous enzyme that is able to catalyze the hydrolysis of a variety of substrates. Of the carboxylate esters, Rsp3690 catalyzes the hydrolysis of 2-naphthyl propionate (16) and 4-nitrophenyl butyrate (17) with kcat/Km values of 1.5 × 105 and 8.8 × 105 M–1 s–1, respectively. Among the organophosphate compounds, Rsp3690 hydrolyzes ethyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate (28) with a value of kcat/km of 3.8 × 105 M–1 s–1. This enzyme has substantially less activity with paraoxon (27) and methyl paraoxon (26) with values of kcat/Km of 1.2 × 104 and 5 × 103 M–1 s–1, respectively. In addition to the hydrolysis of carboxylate and organophosphate esters, Rsp3690 can also catalyze the cleavage of the C–N bond and C–S bond of 4-nitroacetanilide (14) and β-thionaphthylacetate (15) but at a much lower rate. The kcat/Km values for these two compunds are 554 and 470 M–1 s–1, respectively.

The mutant E175K was purified and found to be completely inactive toward the hydrolysis of 4-nitrophenyl butyrate and ethyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate. This mutant protein was also unable to hydrolyze the organophosphate diester bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate.

Stereoselectivity of Rsp3690

The stereoselectivity of Rsp3690 for chiral organophosphonate substrates was addressed using racemic isobutyl 4-nitrophenyl methylphosphonate (30). The time courses for the hydrolysis of racemic 30 by wild-type PTE and Rsp3690 are presented in Figure 6. The addition of wild-type PTE results in the hydrolysis of approximately 50% of the total substrate. The addition of Rsp3690 after ∼27 min resulted in the hydrolysis of the remaining material (Figure 6A). A similar time course was observed when the order of enzyme addition was reversed (data not shown). From the time courses for the hydrolysis of racemic 30 by PTE alone (Figure 6B) and Rsp3690 (Figure 6C) it can be concluded that Rsp3690 and PTE preferentially hydrolyze the opposite enantiomers from one another. Since PTE has been shown previously to hydrolyze the (RP)-enantiomer of isobutyl 4-acetylphenyl methylphosphonate (32) 25 times faster than the (SP)-enantiomer,16 it can be concluded that Rsp3690 prefers to hydrolyze the (SP)-enantiomer of this substrate. For PTE, the (RP)-enantiomer of compound 30 is hydrolyzed 75 times faster than the (SP)-enantiomer based on a fit of the data in Figure 6B to the sum of two exponentials.16 For Rsp3690, the (SP)-enantiomer of compound 30 is hydrolyzed 10 times faster than the (RP)-enantiomer. For the hydrolysis of the isolated enantiomers of (SP)-32 and (RP)-32, the values of kcat/Km using Rsp3690 were determined to be 1200 ± 100 and 88 ± 2 M–1 s–1, respectively.

Figure 6.

Time courses for the hydrolysis of 90 μM racemic 30 using wild-type PTE and Rsp3690. (A) The hydrolysis of 90 μM racemic 30 was initiated with 0.5 nM wild-type PTE. After 27 min, 50 nM Rsp3690 was added to hydrolyze the remaining material. (B) Hydrolysis of 90 μM racemic 30 using 1.0 nM wild-type PTE. (C) Hydrolysis of 90 μM racemic 30 using 100 nM Rsp3690.

Discussion

Substrate Profile for Rsp3690

Rsp3690 was shown to catalyze the hydrolysis of a variety of carboxylate esters. The best substrate was p-nitrophenyl butyrate (17) with a value of kcat/Km of ∼106 M–1 s–1. When the carboxylate group is shortened to acetate (5) or increased to hexanoate (21), the value of kcat/Km is reduced by a factor of ∼4–7 and further reduced by a factor of 60 with octanoate (23). The nitro-substituent of the phenolic leaving group contributes a factor of ∼20 to the value of kcat/Km (5 vs 1). Simpler alcohols such as benzyl, ethyl, and phenethyl (6, 7, 20, 24, and 25) are limited to kcat/Km values of ∼103 M–1 s–1. Amide bonds can also be hydrolyzed, but the rate of hydrolysis is reduced by a factor of about 1,000 (14 vs 5). The hydrolysis of substrates with 2-naphthol as the leaving group is nearly as proficient as the hydrolysis of substrates with p-nitrophenol (8 and 16). We were unable to identify any lactones as a substrate for this enzyme, and thus this is the first enzyme from cog1735 that has not been shown to hydrolyze lactones.

We were able to identify a series of organophosphates and organophosphonates as quite good substrates for Rsp3690. In this regard, ethyl 4-nitrophenyl methyl phosphonates (28) is the best substrate with a value of kcat/Km of ∼4 × 105 M–1 s–1. To the best of our knowledge, this enzyme represents the first esterase from cog1735 where the ability to hydrolyze organophosphonates is nearly as good as the hydrolysis of carboxylate esters. For example, the closely related enzyme from Group 7, Dr0930 from Deinococcus radiodurans, hydrolyzes γ-lactones with values of kcat/Km that exceed 106 M–1 s–1, but the catalytic efficiency for the hydrolysis of racemic 29 is less than 10 M–1 s–1.9 PTE from Pseudomonas diminuta hydrolyzes racemic 29 with a kcat/Km of 107 M–1 s–1 but hydrolyzes δ-nonanoic lactone with a catalytic efficiency of less than 102 M–1 s–1.26,27 Rsp3690 also exhibits stereoselectivity for the hydrolysis of chiral organophosphonates. The (SP)-enantiomer of compound 30 is hydrolyzed ∼10 times faster than the less toxic (RP)-enantiomer. The wild type PTE prefers to hydrolyze the less toxic (RP)-enantiomer.16,28 The high turnover numbers for the hydrolysis of methyl phosphonate esters and the preference for the hydrolysis of the more toxic (SP)-enantiomers make enzymes from Group 4 very attractive targets for directed evolution for enhanced CW agent hydrolysis.

Structural Features of Rsp3690

Crystal structures have been determined for carboxylate esterases from human,29,30 plant,31 and microbial sources.32,33 Many of these carboxylate esterases belong to the α/β-hydrolase superfamily and a catalytic triad of Ser, His, and Asp/Glu.29−33 Carboxylate esterase activities have been identified within the amidohydolase superfamily, but no crystal structures of these enzymes have been solved.11 The active site of Rsp3690 is hydrophobic, which helps to explain the observed substrate specificity. The active site is open to solvent, and the eight loops that immediately follow the eight β-strands from the central β-barrel form a fence-like hydrophobic wall around the binuclear metal center. The α-metal site is shielded by Loops 1, 2, 7, and 8. Trp-42 from the long Loop 1 covers part of the active site from above.

A protein sequence alignment of Rsp3690 and representative proteins from the major groups of cog1735 is shown in Figure 7. All of the metal-binding residues are absolutely conserved except for the residue that bridges the two metal ions. In Rsp3690, Pmi1525, and the PTE homology protein from E. coli, the bridging residue is glutamate. In Lmo2620, Dr0930, and PTE this residue is a carboxylated lysine. A structural overlay of three proteins (Rsp3690, Dr0930, and PTE) is presented in Figure 8. From this comparison it is obvious that the two metals, the central β-barrel, and the interconnecting α-helices superimpose quite nicely and that the major structural differences among these proteins are due predominately to the conformation and length of the eight loops that interconnect the β-strands and the corresponding α-helices.

Figure 7.

Amino acid sequence alignment of representative proteins from the major groups of cog1735: Rsp3690 (Group 4), Pmi1525 (Group 2), PTE homology protein b3379 from E. coli (Group 1), Lmo2620 (Group 5), Dr0930 (Group 7), and PTE (Group 9). The metal binding ligands are highlighted in red. The residues implicated in substrate binding are highlighted in blue. The residues highlighted in olive correspond to the eight loops identified in the three-dimensional crystal structure of Rsp3690.

Figure 8.

Structural comparison of the backbone conformations for Rsp3690, Dr0930, and PTE. The eight β/α loops from Rsp3690, Dr0930, and PTE are depicted in sienna, green, and gold, respectively. The central β-barrel, the surrounding α-helices, and the two metal atoms for the three proteins are depicted in gray. The RMSD between Rsp3690/Dr0930, Rsp390/PTE, and Dr0930/PTE for those parts of the three proteins depicted in gray are 1.0, 1.1, and 0.9 Å, respectively.

The differences in the substrate specificity exhibited by the major groups of proteins contained within cog1735 must be dictated by the composition and conformation of the eight loops that extend outward from the central β-barrel. For example, Afriat-Jurnou et al. have remodeled Loop 7 of PTE to create a variant of the enzyme that led to the emergence of homoserine lactonase activity that is undetectable in wild-type PTE.34 Meier et al. modified the loops contained within the active site of Dr0930 and enhanced the rate of organophosphate ester hydrolysis by up to 5 orders of magnitude.26 Recently, Mll7664 from Mesorhizobium loti was identified as a phosphotriesterase-like metal-carboxylate esterase.11 This protein was apparently transformed into a phosphodiesterase by the single mutation of the bridging glutamate residue of this enzyme to a lysine (E183K). However, we were unable to transform Rs3690 into a phosphodiesterase with the same mutation.

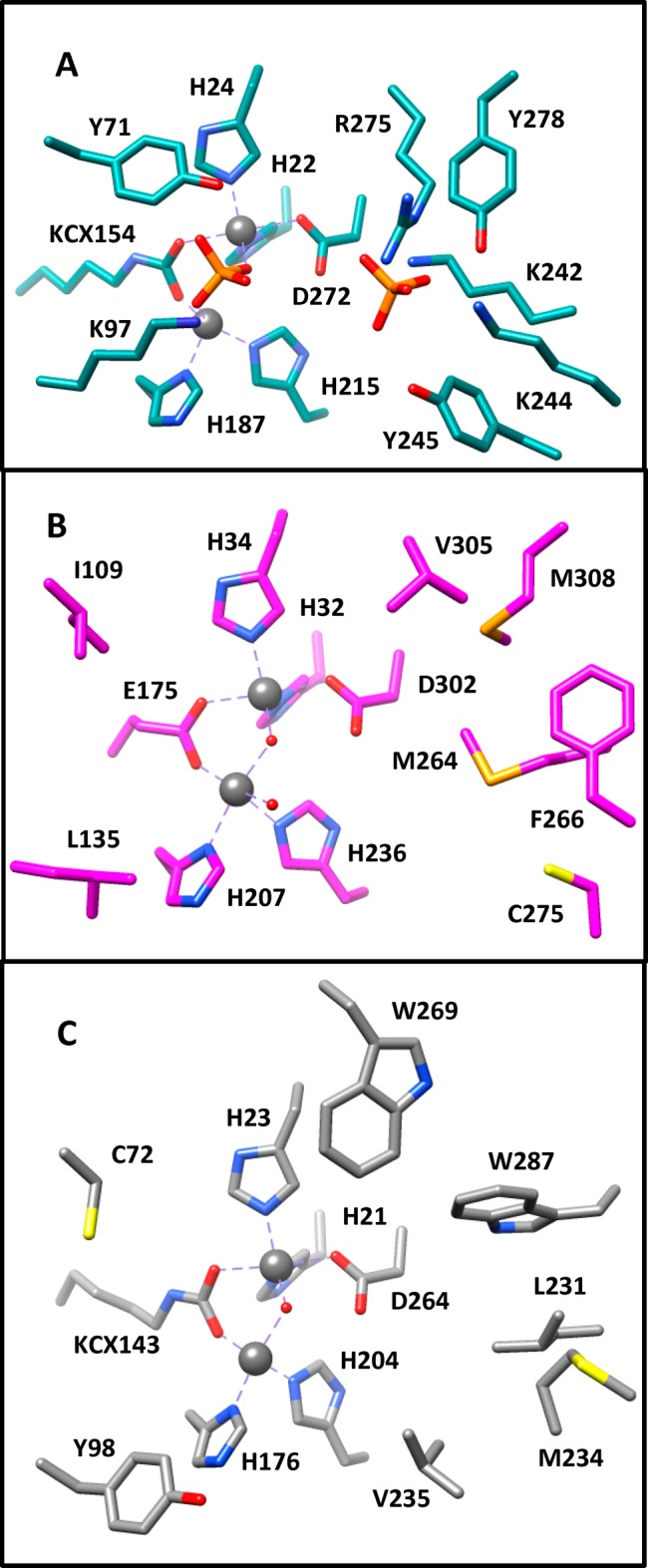

Structural Comparison of Lmo2620, Dr0930, and Rsp3690

Lmo2620 from L. monocytogenes was recently shown to efficiently hydrolyze d-lyxono-1,4-lactone-5-phosphate,10 while Dr0930 efficiently hydrolyzes δ- and γ-lactones.9 Those residues that constitute the active sites of these enzymes and Rsp3690 are presented in Figure 9. In the structure of Lmo2620 (Figure 9A) two orthophosphate molecules are bound within the active site. The proximal phosphate bridges the two divalent cations and displaces the hydroxide that usually coordinates the two metal ions. The distal phosphate is ∼7.1 Å from the proximal phosphate and forms polar interactions with Lys-242, Lys-244, Arg-275, and Tyr-278. A computational model for the binding of the substrate to the active site of Lmo2620 is consistent with the phosphate moiety of the substrate binding to the site occupied by the distal phosphate.10 The hydroxyl groups attached to C-2 and C-3 likely interact with Lys-97 and Tyr-71. In the active site of Dr0930 the long hydrophobic tail of the best γ-lactones will interact with those residues that are positionally equivalent to those that interact with the distal phosphate in Lmo2620 (Figure 9C). These residues include the hydrophobic side chains of Leu-231, Met-234, Trp-269, and Trp-287. The best substrates for these three enzymes are shown in Scheme 3.

Figure 9.

Active site structure for Lmo2620 (A), Rsp3690 (B), and Dr0930 (C).

Scheme 3.

Predictions of Function for Unannotated Members of cog1735

The active site of Rsp3690 is presented in Figure 9B. The four residues that interact with the distal phosphate in Lmo2620 are replaced by the hydrophobic residues Met-264, Phe-266, Val-305 and Met-308. These residues create a hydrophobic environment within the active site of Rsp3690 and this may help to explain why Rsp3690 efficiently catalyzes the hydrolysis of 2-naphthyl acetate and a variety of other substrates with a hydrophobic structural scaffold. The residues that help to dictate substrate specificity in selected groups of cog1735 are highlighted in blue in Figure 7. From these comparisons we can predict that Pmi1525 will likely catalyze the hydrolysis of hydrophobic carboxylate esters similar to the substrate specificities of Dr0930 and Rsp3690. However, the substrate specificity of the PTE homology protein (b3379) will likely include compounds that contain either phosphate or carboxylate functional groups (similar to Lmo2620) since this enzyme contains a conserved arginine residue (R246) that aligns with R275 of Lmo2620 and a conserved lysine residue (K213) that aligns with K242 of Lmo2620. This information is being used to experimentally characterize the catalytic properties of the PTE homology protein (PHP) and those enzymes most closely related to Pmi1525.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- COG

cluster of orthologous groups

- AHS

amidohydrolase superfamily

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-galactoside

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- PTE

phosphotriesterase

- ICPMS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

This work was supported in part by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-840) and the National Institutes of Health (GM 71790).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Holm L.; Sander C. (1997) An evolutionary treasure: unification of a broad set of amidohydolase related to urease. Proteins 28, 72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert C. M.; Raushel F. M. (2005) Structural and catalytic diversity within the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 44, 6383–6391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson H. J.; Morris J. H.; Ferrin T. E.; Babbitt P. C. (2009) Using sequence similarity network for visualization of relationships across diverse protein superfamilies. PLoS One 4, e4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem E.; Raushel F. M. (2005) Detoxification of organophosphate nerve agents by bacterial phosphotriesterase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 207, 459–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely F.; Pedroso M. M.; Gahan L.; Ollis R.; Guddat D. L.; L W.; Schenk G. (2012) Phosphate-bound structure of an organophosphate-degrading enzyme from Agrobacterium radiobacter. J. Inorg. Biochem. 106, 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afriat L.; Roodveldt C.; Manco G.; Tawfik D. S. (2006) The latent promiscuity of newly identified microbial lactonases is linked to a recently diverged phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 45, 13677–13686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uroz S.; Oger P. M.; Chapelle E.; Adeline M.-T.; Faure D.; Dessaux Y. (2008) A Rhodococcus qsdA-encoded enzyme defines a novel class of large-spectrum quorum-quenching lactonases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1357–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow J. Y.; Wu L.; Yew W. S. (2009) Directed evolution of a quorum-quenching lactonase from Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis K-10 in the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 48, 4344–4553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang D. F.; Kolb P.; Fedorov A. A.; Meier M. M.; Fedorov I. V.; Nguyen T. T.; Sterner R.; Almo S. C.; Shoichet B. K.; Raushel F. M. (2009) Funtional annotation and three-dimensional structure of Dr0930 from Deinococcus radiodurans, a close relative of phosphotriesterase in the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry 48, 2237–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang D. F.; Kolb P.; Fedorov A. A.; Xu C.; Fedorov E. V.; narindoshivili T.; Williams H. J.; Shoichet B. K.; Almo S. C.; Raushel F. M. (2012) Structure-based function discovery of an enzyme for the hydrolysis of phosphorylated sugar lactones. Biochemistry 51, 1762–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrich L.; Manco G. (2009) Evolution in the amidohydrolase auperfamily: substrate-assisted gain of gunction in the E183K mutant of a phosphotriesterase-like metal-carboxylesterase. Biochemistry 48, 5602–5612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merone L.; Mandrich L.; Rossi M.; Manco G. (2005) A thermostable phosphotriesterase from the archeon Sulfolous solfataricus: cloning, overexpression and properties. Extremophiles 9, 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawwa R.; Aikens J.; Turner R. J.; Santarsiero B. D.; Mesecar A. D. (2009) Structural basis for thermostability revealed through the identification and characterization of a highly thermostable phosohotriestserase-like lactonase from Geobacillus stearothermophilus. Arch. Biochem. Biophy. 488, 109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawwa R.; Larsen S. D.; Ratia K.; Mesecar A. D. (2009) Structure-based and random mutagenesis approaches increase the organophosphate-degrading activity of a phosphotriesterase homologue from Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Mol. Biol. 393, 36–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder J. L.; Stephenson R. C.; Dresser M. J.; Pitera J. W.; Scanlan T. S.; Fletterick R. J. (1998) Biochemical characterization and crystallographic structure of an Escherichia coli protein from the phosphotriestease gene family. Biochemistry 37, 5096–5106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai P. C.; Bigley A. N.; Li Y.; Ghanem E.; Cadieux C. L.; Kasten S. A.; Reeves T. E.; Cerasoli D. M.; Raushel F. M. (2010) Stereoselective hydrolysis of organophosphate nerve agents by the bacterial phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 49, 7978–7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat S. S.; Bagaria A.; Kumaran D.; Holmes-Hampton G. P.; Fan H.; Sali A.; Sauder J. M.; Burley S. K.; Lindahl P. A.; Swaminathan S.; Raushel F. M. (2011) Catalytic mechanism and three-dimensional structure of adenine deaminase. Biochemistry 50, 1917–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E.; Wong C. H. (2002) A pH sensitive colorimetric assay for the high-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors and substrates: a case study using kinases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z.; Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T. R.; Sheldrick G. M. (2002) Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. (2002) Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Z. Kristallogr. 217, 644–650. [Google Scholar]

- Perrakis A.; Morris R.; Lamzin V. S. (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. A.; Zou J.-Y.; Cowan S. W.; Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Improved methods in building protein models in electron density map and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger A. T.; Adams P. D.; Clore G. M.; Delano W. L.; Gros P.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; MacArthur M. W.; Moss D. S.; Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality for assessing the accuracy of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Meier M. M.; Rajendran C.; Malisi C.; Fox N. G.; Xu C.; Schlee S.; Barondeau D. P.; HÖcker B.; Sterner R.; Raushel F. M. (2013) Molecular engineering of organophosphate hydrolysis activity from a weak promiscuous lactonase template. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 135, 11670–11677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afriat L.; Roodveldt C.; Manco G.; Tawfik D. S. (2006) The latent promiscuity of newly identified microbial lactonases is linked to a recently diverged phosphotriesterase. Biochemistry 45, 13677–13681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigley A. N.; Xu C.; Henderson T. J.; Harvey S. P.; Raushel F. M. (2013) Enzymatic neutralization of the chemical warfare agent VX: evolution of phosphotriesterase for phosphorothiolate hydrolysis. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 135, 10426–10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Li Y., Song G., Zhang D., Shaw N., Liu Z. J.. (209) Crystal structure of human esterase D: a potential genetic marker of retinoblastoma. FASEB J. 23, 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C. D.; Bencharit S.; Edwards C. C.; Hyatt J. L.; Tsurkan L.; Bai F.; Fraga C.; Morton C. L.; Howard-Williams E. L.; Potter P. M.; Redinbo M. R. (2005) Structural insight into drug processing by human carboxylesterase 1: tamoxifen, mevastatin, and inhibition by benzil. J. Mol. Biol. 352, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilepenruma N. R.; Marshall S. D. G.; Squire C. J.; Baker H. M.; Oakeshott J. G.; Russell R. J.; Plummer K. M.; Newcomb R. D.; Baker E. N. (2007) High-resolution crystal structure of plant carboxylesterase AeCXE1, from Actinidia eriantha, and its complex with a high-affinity inhibitor paraoxon. Biochemistry 46, 1851–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Ewis H. E.; Tai P. C.; Lu C. D.; Weber I. T. (2007) Crystal structure of the Geobacillus stearothermophilus carboxylesterase Est55 and its activation of prodrug CPT-11. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 212–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone G. D.; Menchise V.; Manco G.; Mandrich L.; Sorrentino N.; Lang D.; Rossel M.; Pedone C. (2001) The crystal structure of a hyper-thermophilic carboxylesterase from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afriat-Jurnou L.; Jackson C. J.; Tawfik D. S. (2012) Reconstructing a missing link in the evolution of a recently diverged phosphotriesterase by active-site loop remolding. Biochemistry 51, 6047–6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]