Abstract

vav1 has been shown to play a key role in lymphocyte development and activation, but its potential importance in macrophage activation has received little attention. We have previously reported that exposure of macrophages to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) leads to increased activity of hck and other src-related tyrosine kinases and to the prompt phosphorylation of vav1 on tyrosine. In this study, we tested the role of vav1 in macrophage responses to LPS, focusing on the upregulation of nuclear factor for interleukin-6 expression (NF-IL-6) activity and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) protein accumulation in RAW-TT10 murine macrophages. We established a series of stable cell lines expressing three mutant forms of vav1 in a tetracycline-regulatable fashion: (i) a form producing a truncated protein, vavC; (ii) a form containing a point mutation in the regulatory tyrosine residue, vavYF174; and (iii) a form with an in-frame deletion of 6 amino acids required for the guanidine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity of vav1 for rac family GTPases, vavGEFmt. Expression of the truncated mutant (but not the other two mutants) has been reported to interfere with T-cell activation. In contrast, we now demonstrate that expression of any of the three mutant forms of vav1 in RAW-TT10 cells consistently inhibited LPS-mediated increases in iNOS protein accumulation and NF-IL-6 activity. These data provide direct evidence for a role for vav1 in LPS-mediated macrophage activation and iNOS production and suggest that vav1 functions in part via activation of NF-IL-6. Furthermore, these findings indicate that the GEF activity of vav1 is required for its ability to mediate macrophage activation by LPS.

vav1, first identified as a proto-oncogene expressed in hematopoietic cells (34), encodes a 95-kDa protein containing structural motifs common to several different classes of signaling proteins (15). vav1 contains a src homology 2 (SH2) domain, two SH3 domains, a pleckstrin homology domain (39), a cysteine-rich domain similar to the zinc fingers of c-Raf and atypical members of the protein kinase C family (16), and a dbl homology domain found in proteins which serve as guanine exchange factors (GEFs) for small GTPases (2, 17). vav1 was initially reported to exhibit GEF activity for ras, but subsequent studies revealed that vav1 instead serves as a GEF for rac1 and possibly also for other rho family GTPases (1, 11, 14, 30, 31). The GEF activity of vav1 is required for many (15) but not all (35) of the functions of this protein in lymphocytes.

vav1 must be phosphorylated on tyrosine 174 in order to function as a GEF for rac1 (17), and the structural basis for this effect (relief of autoinhibition of the dbl homology domain of vav1) has recently been elucidated (4). vav1 becomes rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated in response to a variety of stimuli in hematopoietic cells, including stimulation of the T-cell receptor (13, 37), the B-cell immunoglobulin M (IgM) antigen receptor (12), and the mast cell IgE high-affinity FcɛRI (37). vav1 is also phosphorylated on tyrosine residues upon stimulation of hematopoietic cells with interleukin-2 (IL-2) (22), IL-3 (20), alpha interferon (IFN-α) (42), IFN-γ (21), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (21, 24).

vav1 has been shown to play a critical role in the development and activation of T and B lymphocytes (23, 50, 57, 58), but relatively little attention has focused on a potential role(s) for vav1 in macrophage activation. Our investigators (21) and others (24) have previously reported that vav1 undergoes rapid tyrosine phosphorylation in response to macrophage activation by LPS. In addition, our group observed that vav1 was physically associated with the src-related tyrosine kinase hck (21) in macrophages, that both broadly active and src family selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors blocked LPS-stimulated hck activation and vav1 tyrosine phosphorylation at concentrations that also inhibited macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (41), and that antisense oligonucleotides specific for murine hck blocked the LPS-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of vav1 (21). Recently, our investigators have also provided evidence that vav1 plays an important role in macrophage responses to bacterial DNA (CpG DNA) (48).

In the present study, we directly examined the role of vav1 in macrophage activation by establishing stable subclones of RAW-TT10 murine macrophages which expressed one of three mutant forms of vav1 in a tetracycline-regulatable fashion. We report that expression of all three mutant forms of vav1 (a form producing a truncated protein, vavC; a point mutant, vavYF174; and a form with a deletion in the GEF domain, vavGEFmt) consistently inhibited the accumulation of iNOS protein in response to challenge with LPS (in the presence of low concentrations of recombinant IFN-γ [rIFN-γ]). Furthermore, the tetracycline-regulatable expression of all three dominant interfering forms of vav1 blocked LPS-mediated increases in the activity of the transcription factor nuclear factor for IL-6 expression (NF-IL-6), previously implicated in the regulation of iNOS gene expression. Taken together, these data provide the first direct evidence for a role for vav1 in the mediation of macrophage activation and iNOS production in response to LPS and indicate that the effects of vav1 are due at least in part to upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was obtained from Mediatech Inc. (Herndon, Va.). l-Glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from GIBCO (Grand Island, N.Y.). Fetal bovine serum containing less than 0.06 endotoxin units/ml by Limulus amebocyte assay was obtained from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, Utah). LPS purified from Escherichia coli strain O111:B4 and rIFN-γ were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Zeocin and tetracycline were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, Calif.).

vav1 constructs.

We obtained constructs encoding (i) a truncated, c-myc epitope-tagged form of vav1, comprising amino acids 538 to 845, including the C-terminal SH2 and SH3 domains; (ii) a YF point mutant at position 174; and (iii) a mutant containing an in-frame deletion of 6 amino acids in the GEF domain, all as generous gifts from A. Weiss (University of California, San Francisco) (Fig. 1). The vav1 constructs were subcloned into the expression vector pTet/Zeo, a tetracycline operator (tetO) expression plasmid which also encodes resistance to the antibiotic Zeocin (gift of D. Underhill, University of Washington).

FIG. 1.

Wild-type and mutant forms of vav1.

Creation of stably transfected cell lines.

RAW-TT10 cells were transfected as described by Underhill et al. (52). The subcloned expression vectors were introduced by electroporation into RAW-TT10 cells (gift of D. Underhill and A. Aderem, University of Washington), which are RAW 264.7 murine macrophages (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) that have been engineered to express the tetracycline-controlled transactivator (tTA) (8, 28, 29, 46, 47) from a tetracycline-regulated promoter (53). In this tetracycline-regulatable, Tet-Off system, the promoter is quiescent in the presence of low doses of tetracycline (53); in the absence of tetracycline, there is a more than 100-fold increase in expression of genes directed by the tetracycline operator (tetO)-promoter sequence (53, 54). Cells with the appropriate pTet/Zeo vector stably integrated were selected for in the presence of Zeocin (1 mg/ml for 1 week, then 500 μg/ml). All stable cell lines were stored in liquid nitrogen. Cells were cultured for less than 3 weeks prior to the experimental conditions.

Cells and cell culture.

Routine medium for RAW 264.7 and RAW-TT10 cells consisted of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U of penicillin G/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml. RAW-TT10/vavC, RAW-TT10/vavYF174, and RAW-TT10/vavGEFmt cells were selected and maintained in medium containing both Zeocin (300 to 1,000 μg/ml) and tetracycline (1 to 5 μg/ml). Under the experimental conditions, RAW-TT10 subclones expressing the mutant forms of vav1 were grown in no tetracycline or in a range of concentrations of tetracycline (from 500 pg/ml to 5 μg/ml) for 48 to 72 h prior to stimulation with LPS (with or without rIFN-γ). Experiments were performed in six-well (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, N.J.) or 100-mm (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) tissue culture dishes. Cells were grown to 60 to 70% confluence prior to stimulation. Cells were stimulated with either rIFN-γ alone or in combination with a range of concentrations of LPS (1 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml). Following stimulation, cells were incubated for approximately 18 h before cell lysates were prepared. For the transient-transfection assays, cells were incubated for 24 h after stimulation before lysates were prepared to assess luciferase activity.

Immunoblotting.

Cells were lysed in extraction buffer (20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 50 μg of NaF/ml, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of aprotinin/ml, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml). For immunoblotting, protein concentrations were first determined for each sample using a standard Bio-Rad Bradford protein assay. Lysate samples containing 100 μg of protein were electrophoresed on sodium dodecyl sulfate-7.5% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and reacted with either a murine monoclonal antibody specific for macrophage iNOS (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Ky.), a murine monoclonal antibody directed at the c-myc epitope tag (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.), or a murine monoclonal antibody specific for vav1 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.). Blots were then reacted with a species-appropriate IgG peroxidase-linked conjugate secondary antibody (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.), and proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham ECL).

Plasmid preparation.

The NF-IL-6-like sequence (1× = TTG TTG TGA AAT CAG) was multimerized previously (25). This cassette (BamHI-KpnI digest) was placed in sense orientation in front of a minimal simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter (pGL3Luc; Promega, Madison, Wis.). The previously described trimerized mutant NF-IL-6 sequence (25) was also placed in the sense orientation (BamHI-KpnI digest) in front of the same minimal SV40 promoter.

Cell transient transfection.

Transient transfection of the individual cell lines was performed by electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (Hercules, Calif.). Twenty micrograms of test plasmid DNA in conjunction with the cytomegalovirus-Renilla luciferase plasmid (CMV-RL; Promega) was mixed with 5 × 106 cells in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma) and transferred to a 0.4-cm electrode gap cuvette. Following a single 250-V, 975-μF pulse, cells were pelleted and then transferred into a well of a six-well plate.

Luciferase assay.

Cell lysates were prepared as described in the Promega DLR luciferase assay kit. The luciferase activity was measured using a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, Calif.). All results reported are representative of at least four experiments.

RESULTS

The mutant forms of vav1 were expressed in RAW-TT10/vavC, RAW-TT10/vavYF174, and RAW-TT10/vavGEFmt cells in a tetracycline-regulatable manner.

We adapted the Tet-Off expression system developed by Underhill and colleagues (53) in order to establish stable cell lines from the RAW-TT10 parental line with tetracycline-regulatable expression of each of the three vav1 constructs. Cell lines were established in the presence of tetracycline (1 to 5 μg/ml) in order to prevent construct expression prior to the time of the experimental conditions.

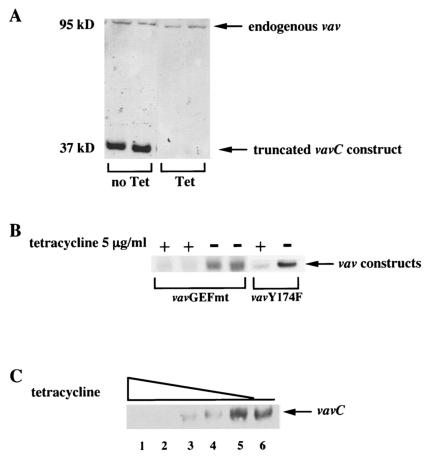

Robust expression of all three mutant forms of vav1 was detected from cells grown in medium without tetracycline for 48 to 72 h (but not in the lysates from cells maintained in the presence of 1 to 5 μg of tetracycline/ml) by immunoblotting of cell lysates with either a murine monoclonal antibody specific for vav1 (Fig. 2A and C) or one specific for the c-myc epitope tag (Fig. 2B). The truncated form of vav1 (vavC) was most easily detected as a protein of approximately 37 kDa by using a murine monoclonal antibody specific for vav1 (Fig. 2A and C), while the two full-length forms of vav1 (vavYF174 and vavGEFmt) were most easily detected by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody specific for the c-myc epitope tag (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Tetracycline-regulatable expression of vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt in RAW-TT10 macrophages. (A) vavC expression was tetracycline regulatable. RAW-TT10/vavC cells were incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline (1 μg/ml). Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) followed by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody specific for vav1. The vavC construct was detected as a protein of approximately 37 kDa in the absence, but not the presence, of tetracycline. Expression of the endogenous vav protein (95 kDa) was not affected by the presence or absence of tetracycline. (B) vavGEFmt and vavYF174 expression was tetracycline regulatable. RAW-TT10/vavGEFmt and RAW-TT10/vavYF174 cells were incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline (5 μg/ml). Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to PAGE followed by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody which recognizes the c-myc epitope tag. (C) Regulation of vavC expression: tetracycline dose response. RAW-TT10/vavC cells were incubated for 72 h in a range of concentrations of tetracycline: 1 μg/ml (lane 1), 100 ng/ml (lane 2), 10 ng/ml (lane 3), 1 ng/ml (lane 4), or 10 pg/ml (lane 5) or in no tetracycline (lane 6). Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to PAGE followed by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody specific for vav1. The truncated vavC construct was detected as a protein of approximately 37 kDa. Expression of the endogenous vav1 protein (95 kDa) was not affected by the presence or absence of tetracycline (not shown).

Expression of the vav1 constructs was both time and tetracycline concentration dependent. In preliminary experiments, we found that expression of each of the vav1 constructs could be detected within 24 h after removal of the cells from tetracycline and that expression was maximal by 48 to 72 h (data not shown). In the representative experiment depicted in Fig. 2C, RAW-TT10/vavC cells were cultured in decreasing concentrations of tetracycline (from 1 μg/ml in lane 1 to 10 pg/ml in lane 5) or in no tetracycline (lane 6) for 72 h prior to analysis. Expression of the truncated vavC construct was detectable in cells cultured in concentrations of tetracycline of 10 ng/ml or less and was maximal in cells exposed to tetracycline concentrations of 10 pg/ml or less. Furthermore, expression of the each of the three vav1 constructs was reversible—addition of tetracycline to cells maintained out of the antibiotic for 72 h led to dramatic declines in construct expression within 24 h, and construct expression was undetectable by 48 to 72 h after reexposure to tetracycline (data not shown).

Tetracycline-regulatable expression of the three mutant forms of vav1 in macrophages inhibited LPS-mediated upregulation of iNOS protein accumulation.

Tetracycline at the range of concentrations tested (10 pg/ml to 5 μg/ml) had no effect on iNOS protein accumulation in response to LPS with or without rIFN-γ in either RAW 264.7 macrophages or RAW-TT10 cells (data not shown). One of the vav1 constructs that we used (vavC) had been shown previously to act as a dominant interfering mutant for vav1 function in T lymphocytes, interfering with NF-AT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) activation after T-cell receptor engagement in Jurkat cells (57). Surprisingly, expression of the two other mutant forms of the protein (vavYF174 and vavGEFmt, both lacking GEF activity) not only failed to inhibit NF-AT activation in Jurkat cells but also actually augmented NF-AT activation in a manner comparable to that of wild-type vav1 (35), indicating that the role of vav1 in T-cell activation did not require its GEF activity.

In contrast, we found that RAW-TT10 macrophages expressing each of the three mutant forms of vav1 consistently accumulated less iNOS protein when cultured in the absence of tetracycline for 48 to 72 h prior to stimulation with LPS and rIFN-γ (Fig. 3A, representative experiments with RAW-TT10/vavYF174 cells [n = 6] and RAW-TT10/vavGEFmt cells (n = 6); B, RAW-TT10/vavC cells [n = 8]). In addition, culture of RAW-TT10/vavC cells in tetracycline concentrations of 10 ng/ml or less for 48 to 72 h prior to stimulation consistently led to both increases in vavC construct expression and diminished accumulation of iNOS protein (Fig. 3B, representative experiment depicted is same as that shown in part in 2C; n = 8). Thus, tetracycline-regulated increases in the expression of three different dominant interfering mutant forms of vav1 consistently inhibited the upregulation of iNOS production in RAW-TT10 macrophages stimulated with LPS and rIFN-γ.

FIG. 3.

Expression of three dominant interfering vav1 constructs (vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt) in RAW-TT10 macrophages inhibited iNOS protein accumulation in response to challenge with LPS and rIFN-γ. (A) RAWTT10/vavYF174 and RAWTT10/vavGEFmt cells were incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline (5 μg/ml) and then stimulated for 18 h with LPS (10 ng/ml) and rIFN-γ (10 U/ml). Cell lysates were prepared, subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and analyzed by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody specific for iNOS. (B) RAW-TT10/vavC cells were incubated for 72 h in a range of concentrations of tetracycline or no tetracycline (same experiment as depicted in Fig. 2C); tetracycline concentrations were 1 μg/ml (lane 1), 100 ng/ml (lane 2), 10 ng/ml (lane 3), 1 ng/ml (lane 4), 10 pg/ml (lane 5), and none (lane 6). Cells were then stimulated for 18 h with LPS (10 ng/ml) and rIFN-γ (10 U/ml). Cell lysates were prepared, subjected to PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting with a murine monoclonal antibody specific for iNOS.

Tetracycline-regulatable expression of the three mutant forms of vav1 in macrophages blocked LPS-mediated upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity.

We compared the upregulation of activity of an NF-IL-6 reporter construct in RAW-TT10/vavC, RAW-TT10/vavYF174, and RAW-TT10/vavGEFmt cells maintained in either the presence or absence of 1 to 5 μg of tetracycline/ml for 48 to 72 h prior to LPS stimulation. Under the experimental conditions, a reporter construct containing trimerized NF-IL-6 recognition sequences upstream of an SV40 minimal promoter and expressing firefly luciferase was used. This construct was introduced into RAW-TT10 cells expressing mutant forms of vav1 by transient transfection. After stimulation with medium or a range of concentrations of LPS with or without rIFN-γ, NF-IL-6 activity was determined by measuring luciferase activity in cell lysates using a standard dual luciferase assay. The increased expression of all three mutant forms of vav1 (vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt) resulted in dramatic inhibition of LPS-mediated increases of NF-IL-6 activity (Fig. 4, n = 6 for vavYF174 and vavGEFmt and n = 4 for vavC). The mean percent inhibition of luciferase activity of the NF-IL-6 plasmid with expression of vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt was 86, 82, and 79%, respectively. Expression of each of the three dominant interfering vav1 constructs also led to diminished basal NF-IL-6 activity in unstimulated cells.

FIG. 4.

Expression of three dominant interfering vav1 constructs (vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt) in RAW-TT10 macrophages blocked LPS-mediated upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity. (A) RAW-TT10/vavC cells were incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline (5 μg/ml) prior to transient transfection by electroporation with the NF-IL-6 luciferase reporter construct, mock transfection (no DNA), or transfection with the CMV-RL control plasmid, as indicated. After transfection, cells were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h prior to preparation of cell lysates and analysis of firefly luciferase activity (see Materials and Methods). This is a representative experiment (n = 4). (B) RAWTT10/vavYF174 and RAWTT10/vavGEFmt cells were incubated for 72 h in the presence or absence of tetracycline (5 μg/ml) prior to transient transfection by electroporation with the NF-IL-6 luciferase reporter construct, mock transfection (no DNA), or transfection with the CMV-RL control plasmid, as indicated. After transfection, cells were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h prior to preparation of cell lysates and analysis of firefly luciferase activity. This is a representative experiment (n = 6 for both cell lines).

DISCUSSION

Tyrosine phosphorylation pathways play important roles in macrophage responses to bacterial LPS (40, 56), but little is known about the substrates of the tyrosine kinases activated in response to stimulation by LPS and other bacterial products. Our investigators have previously reported that the 95-kDa proto-oncogene vav1 is rapidly phosphorylated on tyrosine in murine macrophages stimulated with LPS (21). vav1 functions in part as a GEF for small GTPases of the rho family, including rac1, rhoA, and cdc42. The tyrosine phosphorylation of vav1 at position 174 is required for its GEF activity. Interestingly, the GEF activity of vav1 is reportedly required for some (15) but not all (35) of its biological activities in lymphocytes.

vav1 has been reported to play a key role in the T-cell activation via the upregulation of NF-AT activity in these cells. Expression of a truncated mutant form of vav1 interfered with NF-AT activation in Jurkat cells, while expression of wild-type vav1 augmented NF-AT activation (57). However, the effect of vav1 on NF-AT activation in Jurkat cells does not appear to require its GEF activity, as the expression of two vav1 constructs lacking GEF activity (a YF point mutant at position 174 and a mutant containing a deletion within the GEF domain) actually potentiated NF-AT activation in a manner comparable to that of wild-type protein (35).

In contrast to the studies in Jurkat cells, we found that expression of all three mutant forms of vav1 (vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt) in RAW-TT10 macrophages led to diminished accumulation of iNOS protein in response to stimulation with LPS and rIFN-γ. Furthermore, expression of each of the constructs encoding mutant forms of vav1 led to reduced NF-IL-6 activity in response to LPS challenge. Together, these data suggest that the proto-oncogene vav1 plays a critical role in LPS-mediated macrophage activation and iNOS upregulation and that the GEF activity of vav1 is required for its role in macrophage (but not T-cell) activation. Our group has also recently observed that expression of each of these three vav1 mutants inhibited TNF secretion and iNOS protein accumulation in RAW-TT10 macrophages stimulated with bacterial (CpG) DNA (48).

Several groups have shown that NF-IL-6 (a heterodimer of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ) plays an important role in the regulation of transcription of iNOS (18, 27), IL-6 (6, 7), and IL-1β (25, 26). As expected, we found that LPS potently upregulated NF-IL-6 activity in RAW 264.7 cells (data not shown), RAW-TT10 cells (data not shown), and all three RAW-TT10/vav1 cell lines (Fig. 4). In each of the three cell lines expressing mutant forms of vav1 (vavC, vavYF174, and vavGEFmt) in the absence of tetracycline, construct expression resulted in dramatic inhibition of LPS-mediated increases of NF-IL-6 activity (Fig. 4). LPS inducibility of NF-IL-6 activity was not completely eliminated by the expression of the vav1 dominant interfering mutants, suggesting that vav1-independent pathways may also play a role in the upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity in response to LPS. Taken together, these findings suggest that vav1 upregulates iNOS transcription in macrophages at least in part via an increase in NF-IL-6 activity.

The mechanism(s) by which vav1 leads to NF-IL-6 activation in macrophages is not known. In T cells, vav1 serves as a GEF for rac1 (1, 10, 51), and this function is necessary for some but not all activities of vav1 in these cells. vav1 has been reported to mediate T-cell activation by several different mechanisms that result in the activation of the transcription factors NF-AT (32, 33, 35, 50) and AP-1 (33). Activation of NF-AT does not require the GEF activity of vav1 (35), while activation of AP-1 appears to require this activity in a rac1/jnk/c-jun pathway (33). vav1 also activates phospholipase C-γ1 via both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent and -independent pathways in T cells (45). In addition to these effects, vav1 also may directly affect gene transcription by serving as a component of transcriptionally active complexes (NF-AT and NF-κB-like complexes) in T cells (32).

Our data suggest that the upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity and iNOS production by vav1 in macrophages is at least partly due to its GEF activity. We and others have implicated erk, p38, and jnk mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in macrophage activation by LPS (5, 36, 40, 49, 55) and other bacterial products (38), and the activation of rac1 by vav1 leads to the activation of jnk and/or p38 kinases in T cells and other hematopoietic cells (15). Baldassare et al. (9) reported that pharmacologic inhibition of the p38 pathway markedly inhibited the LPS-mediated upregulation of NF-IL-6 activation and resultant IL-1β (but not TNF) gene transcription in RAW 264.7 macrophages. These authors speculated that differences in phosphorylation of either C/EBPβ or C/EBPδ could be responsible for this effect. However, we have examined mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in RAW-TT10 cell lines expressing the three vav1 mutants and have not detected significant inhibition of either jnk or p38 (or erk) activation in response to LPS stimulation (data not shown), suggesting that the dominant interfering activity of the vav1 mutants is not mediated primarily by inhibition of p38 or jnk activation.

Our data provide the first direct evidence for a role for vav1 in macrophage activation and iNOS upregulation in response to LPS. Recent work has clearly demonstrated that toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways are key sensors for bacterial products such as LPS, and macrophage responses to LPS require TLR4 (3, 19, 43, 44). Further studies are needed to delineate the mechanism(s) by which vav1 leads to the upregulation of NF-IL-6 activity and iNOS transcription in macrophages stimulated with LPS. In addition, the relationship between the vav1 pathway and other macrophage signaling pathways, including those mediated by TLRs and those triggered by phagocytic receptors, needs to be further defined. The RAW-TT10 macrophage tetracycline-regulatable gene expression system should provide a powerful tool for these studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Children's Foundation Research Center at Le Bonheur Children's Medical Center (B.K.E.) and by Le Bonheur Children's Medical Center (S.A.G., K.M.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, K., K. L. Rossman, B. Liu, K. D. Ritola, D. Chiang, S. L. Campbell, K. Burridge, and C. J. Der. 2000. Vav2 is an activator of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10141-10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, J. M., H. Houston, J. Allen, T. Lints, and R. Harvey. 1992. The hematopoietically expressed vav proto-oncogene shares homology with the dbl GDP-GTP exchange factor, the bcr gene and a yeast gene (CDC24) involved in cytoskeletal organization. Oncogene 7:611-618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aderem, A., and R. J. Ulevitch. 2000. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature 406:782-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghazadeh, B., W. E. Lowry, X. Y. Huang, and M. K. Rosen. 2000. Structural basis for relief of autoinhibition of the Dbl homology domain of proto-oncogene Vav by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell 102:625-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajizian, S. J., B. K. English, and E. A. Meals. 1999. Specific inhibitors of p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways block inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor accumulation in murine macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ. J. Infect. Dis. 179:939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akira, S., H. Isshiki, T. Sugita, O. Tanabe, S. Kinoshita, Y. Nishio, T. Nakajima, T. Hirano, and T. Kishimoto. 1990. A nuclear factor for IL-6 expression (NF-IL6) is a member of the C/EBP family. EMBO J. 9:1897-1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akira, S., and T. Kishimoto. 1992. IL-6 and NFIL-6 in acute-phase response and viral infection. Immunol. Rev. 127:25-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.A-Mohammadi, S., L. Alvarez-Vallina, L. J. Ashworth, and R. E. Hawkins. 1997. Delay in resumption of the activity of tetracycline-regulatable promoter following removal of tetracycline analogues. Gene Ther. 4:993-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldassare, J., Y. Bi, and C. J. Bellone. 1999. The role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in IL-1b transcription. J. Immunol. 162:5367-5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billadeau, D. D., K. M. Brumbaugh, C. J. Dick, R. A. Schoon, X. R. Bustelo, and P. J. Leibson. 1998. The Vav-Rac1 pathway in cytotoxic lymphocytes regulates the generation of cell-mediated killing. J. Exp. Med. 188:549-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boguski, M. S., A. Bairoch, T. K. Attwood, and G. S. Michaels. 1992. Proto-vav and gene expression. Nature 358:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bustelo, X. R., J. A. Ledbetter, and M. Barbacid. 1992. Product of vav proto-oncogene defines a new class of tyrosine protein kinase substrates. Nature 356:68-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustelo, X. R., and M. Barbacid. 1992. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product in activated B cells. Science 256:1196-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bustelo, X. R., K. L. Suen, K. Leftheris, C. A. Meyers, and M. Barbacid. 1994. Vav cooperates with Ras to transform rodent fibroblasts but is not a Ras GDP/GTP exchange factor. Oncogene 9:2405-2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bustelo, X. E. 2000. Regulatory and signaling properties of the Vav family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:1461-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coppola, J., S. Bryant, T. Koda, D. Conway, and M. Barbacid. 1991. Mechanism of activation of the vav protooncogene. Cell. Growth Differ. 2:95-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo, P., K. E. Schuebel, A. A. Ostorm, J. S. Gutkind, and X. R. Bustelo. 1997. Phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of Rac-1 GDP/GTP exchange by the vav proto-oncogene product. Nature 385:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dlaska, M., and G. Weiss. 1999. Central role of transcription factor NF-IL6 for cytokine and iron-mediated regulation of murine inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. J. Immunol. 162:6171-6177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobrovolskaia, M. A., and S. N. Vogel. 2002. Toll receptors, CD14, and macrophage activation and deactivation by LPS. Microbes Infect. 4:903-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dosil, M., S. Wang, and I. R. Lemischka. 1993. Mitogenic signalling and substrate specificity of the Flk2/Flt3 receptor tyrosine kinase in fibroblasts and interleukin 3-dependent hematopoietic cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6572-6585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.English, B. K., S. L. Orlicek, Z. Mei, and E. A. Meals. 1997. Bacterial LPS and IFN-γ trigger the tyrosine phosphorylation of vav in macrophages: evidence for involvement of the hck tyrosine kinase. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62:859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans, G. A., O. M. Howard, R. Erwin, and W. L. Farrar. 1993. Interleukin-2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product in human T cells: lack of requirement for the tyrosine kinase lck. Biochem. J. 294:339-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer, K. D., A. Zmuldzinas, S. Gardner, M. Barbacid, A. Bernstein, and C. Guidos. 1995. Defective T-cell receptor signalling and positive selection of Vav-deficient CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes. Nature 374:474-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geng, Y., E. Gulbins, A. Altman, and M. Lotz. 1994. Monocyte deactivation by interleukin-10 via inhibition of tyrosine kinase activity and the Ras signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:8602-8606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godambe, S. A., D. D. Chaplin, T. Takova, and C. J. Bellone. 1994. Upstream NFIL-6-like site located within a DNase I hypersensitivity region mediates LPS-induced transcription of the murine interleukin-1 beta gene. J. Immunol. 153:143-152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godambe, S. A., D. D. Chaplin, T. Takvoa, and C. J. Bellone. 1994. An NFIL-6 sequence near the transcriptional initiation site is necessary for the lipopolysaccharide induction of murine interleukin-1 beta. DNA Cell Biol. 13:561-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldring, C. E., C. S. Reveneau, M. Algarte, and J. F. Jeannin. 1996. In vivo footprinting of the mouse inducible nitric oxide synthase gene: inducible protein occupation of numerous sites including Oct and NF-IL6. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1682-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gossen, M., and H. Bujard. 1992. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5547-5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gossen, M., S. Freundlieb, G. Bender, G. Muller, W. Hillen, and H. Bujard. 1995. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science 268:1766-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulbins, E., K. M. Coggeshall, G. Baier, S. Katzav, P. Burn, and A. Altman. 1993. Tyrosine kinase-stimulated guanine nucleotide exchange activity of Vav in T cell activation. Science 260:822-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han, J., K. Luby-Phelps, B. Das, X. Shu, Y. Xia, R. D. Mosteller, U. M. Krishna, J. R. Falck, M. A. White, and D. Borek. 1998. Role of substrates and products of PI-3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science 279:558-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houlard, M., R. Arudchandran, F. Regnier-Ricard, A. Germani, S. Gisselbrecht, U. Blank, J. Rivera, and N. Varin-Blank. 2002. Vav1 is a component of transcriptionally active complexes. J. Exp. Med. 195:1115-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaminuma, O., M. Deckert, C. Elly, Y. C. Liu, and A. Altman. 2001. Vav-Rac1-mediated activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase/c-Jun/AP-1 pathway plays a major role in stimulation of the distal NFAT site in the interleukin-2 gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3126-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzav, S., D. Martin-Zanca, and M. Barbacid. 1997. Vav, a novel human oncogene derived from a locus ubiquitously expressed in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 8:2283-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhne, M. R., G. Ku, and A. Weiss. 2000. A guanine nucleotide exchange factor-independent function of Vav1 in transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2185-2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, J., and P. Young. 1996. Role of CSBP/p38/RK stress response kinase in LPS and cytokine signaling mechanisms. J. Leukoc. Biol. 59:152-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolis, B., P. Hu, S. Katzav, W. Li, J. M. Oliver, A. Ullrich, A. Weiss, and J. Schlessinger. 1992. Tyrosine phosphorylation of vav proto-oncogene product containing SH2 domain and transcription factor motifs. Nature 356:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monier, R. M., K. L. Orman, E. A. Meals, and B. K. English. 2002. Differential effects of p38- and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors on inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor production in murine macrophages stimulated with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 185:921-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Musacchio, A., T. Gibson, P. Rice, J. Thompson, and M. Saraste. 1993. The PH domain: a common piece in the structural patchwork of signalling proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 18:343-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlicek, S. L., E. Meals, and B. K. English. 1996. Differential effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on tumor necrosis factor and nitric oxide production by murine macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 174:638-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orlicek, S. L., J. H. Hanke, and B. K. English. 1999. The src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP1 blocks LPS and IFN-γ-mediated TNF and iNOS production in murine macrophages. Shock 12:350-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Platanias, L. C., and M. E. Sweet. 1994. Interferon alpha induces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product in hematopoietic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:3143-3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poltorak, A., X. He, I. Smirnova, M. Y. Liu, C. V. Huffel, X. Du, D. Birdwell, D. Alejos, M. Silva, C. Galanos, M. Freudenberg, P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, and B. Beutler. 1998. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science 282:2085-2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poltorak, A., P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, C. Citterio, and B. Beutler. 2000. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2163-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds, L. F., L. A. Smyth, T. Norton, N. Freshney, J. Downward, D. Kioussis, and V. L. Tybulewicz. 2002. Vav1 transduces T cell receptor signals to the activation of phospholipase C-g1 via phospohoinositide-3-kinase-dependent and -independent pathways. J. Exp. Med. 195:1103-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shockett, P., M. Difilippantonio, N. Hellman, and D. Schatz. 1995. A modified tetracycline-regulated system provides autoregulatory, inducible gene expression in cultured cells and transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6522-6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shockett, P. E., and D. G. Schatz. 1996. Diverse strategies for tetracycline-regulated inducible gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:5173-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stovall, S. H., A.-K. Yi, E. A. Meals, A. J. Talati, S. A. Godambe, and B. K. English. 2004.. Role of vav1 and src-related tyrosine kinases in macrophage activation by CpG DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279:13809-13816. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Swantek, J. L., M. H. Cobb, and T. D. Geppert. 1997. Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) is required for lipopolysaccharide stimulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) translation: glucocorticoids inhibit TNF-α translation by blocking JNK/SAPK. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6274-6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarakhovsky, A., M. Turner, S. Schaal, P. J. Mee, L. P. Duddy, K. Rajwesky, and V. L. Tybulewicz. 1995. Defective antigen receptor-mediated proliferation of B and T cells in the absence of Vav. Nature 374:467-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teramoto, H., P. Salem, K. C. Robbins, X. R. Bustelo, and J. S. Gutkind. 1997. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product links FcɛR1 to the Rac1-JNK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10751-10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Underhill, D. M., J. Chen, L. A. Allen, and A. Aderem. 1998. MacMARCKS is not essential for phagocytosis in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33619-33623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Underhill, D. M., A. Ozinsky, A. M. Hajjar, A. Stevens, C. B. Wilson, M. Bassetti, and A. Aderem. 1999. The Toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature 401:811-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Underhill, D. M., A. Ozinsky, K. D. Smith, and A. Aderem. 1999. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates mycobacteria-induced proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14459-14463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weinstein, S. L., J. S. Sanghera, K. Lemke, A. L. DeFranco, and S. L. Pelech. 1992. Lipopolysaccharide induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14955-14962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weinstein, S. L., M. R. Gold, and A. L. DeFranco. 1991. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide stimulates protein tyrosine phosphorylation in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4148-4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu, J., S. Katzav, and A. Weiss. 1995. A functional T-cell receptor signaling pathway is required for p95vav activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4337-4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, R., F. W. Alt, L. Davidson, S. H. Orkin, and W. Swat. 1995. Defective signalling through the T- and B-cell antigen receptors in lymphoid cells lacking the vav proto-oncogene. Nature 374:470-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]