Introduction

Insulin-induced hypoglycemia is a life-threatening iatrogenic phenomenon that activates multiple neural and humoral corrective systems. When blood glucose levels begin to fall below 80 mg/dL, a sequential series of events occurs. Insulin secretion ceases; secretion of glucagon, epinephrine (E), corticosterone, and growth hormone is initiated, and neurogenic systems trigger food intake. All of these responses are recruited when glucose decreases to approximately 60 mg/dL. Together, these corrective responses (counter-regulatory responses or CRR) rapidly restore euglycemia. Unfortunately, however, the magnitude of the CRR decreases with recurring hypoglycemic episodes, leading to a syndrome known as hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure (HAAF). During HAAF, glucose levels can fall dangerously low without eliciting the behavioral signs that usually accompany hypoglycemia. HAAF is the major limiting factor of the intensive insulin therapy needed to control the deleterious effects of diabetic hyperglycemia (1, 2). In order to understand and develop therapies for HAAF, it is critical to understand the mechanisms underlying hypoglycemia detection and initiation of the CRR.

For many decades, it has been clear that there are glucose sensors located throughout the body and the central nervous system (CNS) (3–8). The goal of this chapter is to describe glucose sensing by central and peripheral glucose sensors and evidence that supports their roles in hypoglycemia detection and HAAF. The authors will focus on 3 glucose-sensing systems that contribute importantly to glucose counterregulation: the ventrome-dial hypothalamic nucleus (VMN) (9, 10), the hindbrain catecholamine neurons (11), and the portal-mesenteric vein (PMV) (12).

Cellular Mechanisms of Glucose Sensing

The idea that discrete glucose sensors detect changes in extracellular glucose and use this information to regulate glucose and/or energy homeostasis is not new. In 1955, John Mayer stated in his glucostatic theory, that “somewhere, possibly in the hypothalamic centers shown to be implicated in the regulation of food intake, perhaps peripherally as well, there are glucoreceptors sensitive to blood glucose in the measure that they can utilize it” (13). Less than a decade later, the laboratories of Oomura and Anand independently discovered hypothalamic neurons whose firing rate was directly regulated by glucose (5, 14). Using single unit recordings, Oomura demonstrated that neurons in what were then thought to be the satiety and feeding centers within the hypothalamus showed reciprocal responses to changes in extracellular glucose (5). Since that time, glucose sensors have been found throughout the hypothalamus and numerous other central sites, including, but not limited to, the amygdala, hippo-campus, hindbrain, and recently the subfornical organ (3, 15–18). As Mayer predicted, they are also found peripherally. In addition to the pancreatic beta cell, peripheral glucose sensors are located in the PMV of the liver, carotid body, oral cavity, and the gut (19–21). The VMN, hindbrain, and PMV glucose sensors appear to be particularly important for the CRR.

There are 2 broad categories of glucose sensing neurons. Glucose-excited (GE) neurons increase, while glucose-inhibited (GI) neurons decrease their action potential frequency as glucose increases (22). Both GE and GI neurons are often found together in brain regions containing glucose-sensing neurons. Glucose sensors can be further divided into those that respond to changes in glucose metabolism (metabolism-dependent) and those that respond to the glucose molecule per se (metabolism-independent). The latter include taste receptors such as those found in the oral cavity and gut as well as the lateral hypothalamus (LH) orexin neurons. In contrast, most glucose sensors within the medial hypothalamus and some within the hindbrain, respond to changes in the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)/adenosine diphosphate (ADP) (or adenosine monophosphate [AMP]) ratio, which are secondary to glucose metabolism (23, 24). The mechanisms underlying glucose sensing are surprisingly diverse, comprising several different metabolic enzymes and a number of ion channels. These mechanisms will be described for GE and GI neurons.

It is important to consider that although very high glucose concentrations analogous to those seen in the periphery during severe uncompensated diabetes were originally used to define glucose sensing neurons, brain glucose levels are now known to be ~30% of that in blood. In vivo microdialysis studies report hypothalamic glucose levels of 1 to 2.5 mM during peripheral euglycemia, ranging from ~5 mM during hyperglycemia (blood glucose 20 mM) to 0.2 mM during severe hypoglycemia (blood glucose 2 to 3 mM) (25, 26). Similar glucose concentrations during euglycemia have been noted in other brain regions (27). Thus, emphasis will be placed on studies of GE and GI neurons that used physiological glucose concentrations within this range.

GE neurons

GE neurons were first identified in the ventromedial region of the hypothalamus (VMH), a region that contains the VMN and the arcuate (ARC) nucleus. Thus, there are more data regarding these GE neurons compared to GE neurons in other locations. In 1990, Ashford et al used the pancreatic beta cell as inspiration for the mechanism by which VMH GE neurons sense glucose (28). These investigators showed that, like the pancreatic beta cell, glucose directly depolarizes VMH GE neurons by closing inhibitory ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels (28). Although these early studies used supraphysiological glucose levels, KATP channel-dependent glucose sensing by VMH GE neurons has stood the test of time (22). However, it is important to note that most neurons, glucose-sensing or not, possess KATP channels or other ion channels that are regulated by ATP (29). Thus, the presence of such channels is not sufficient to define a neuron as glucose-sensing.

More recent studies point out further similarities with the pancreatic beta cell in that both the beta cell and most (but not all) VMH GE neurons require the low-affinity hexokinase IV isoform glucokinase (GK), which catalyzes the committed step in glycolysis, to sense glucose (30). The pancreatic beta cell also uses the low-affinity glucose transporter isoform 2 (GLUT2) to transport glucose into the cell. However, ~30% of all VMH neurons express GLUT2 without regard to glucose sensing capability.

Instead, the insulin-sensitive GLUT4 may play a role, since twice as many glucose sensing versus nonglucose-sensing neurons express both the GLUT4 and the insulin receptor (31). The neuronal GLUT3 is expressed in all VMH neurons (31). Like VMH GE neurons, GE neurons in the amygdala and dorsal vagal complex (DVC) are GK-dependent. The DVC GE neurons use the KATP channel to sense glucose, but this has not yet been demonstrated for amygdalar GE neurons (32, 33). Glucose also closes an inhibitory ion channel (eg, potassium or chloride) to activate LH melanocortin-concentrating hormone (MCH) GE neurons. However, the identity of this inhibitory channel is not known (34).

The cellular fuel sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) may mediate glucose sensing in some GE neurons. A decreased ATP:AMP ratio activates AMPK. AMPK is present in most cells and plays a role in activating cellular processes that restore intracellular ATP levels. Over the past decade, much data have emerged regarding a prime role for hypothalamic AMPK in the regulation of whole-body energy homeostasis (35). AMPK has also been linked to glucose sensing in several populations of GE neurons. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons in the anterior hypothalamus are AMPK-dependent GE neurons (36), as are the GnRH-derived immortalized GT1-7 cell line (37). Interestingly, glucose opens a nonselective cation channel to activate GnRH neurons rather than closing an inhibitory channel such as the KATP channel (36). GT1-7 cells possess the KATP channel (37). However, whether the KATP channel contributes to glucose sensing in these cells is not known. Like GnRH neurons, GE neurons found in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and subfornical organ also use a cation channel rather than the KATP channel to sense glucose (18, 38). Whether glucose sensing in PVN or subfornical organ GE neurons uses GK or AMPK is not known, although GK is expressed in the PVN (39).

The ARC pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons may also be AMPK-dependent GE neurons, although this is still controversial. Several studies using rats as well as wild-type mice and mice whose POMC neurons express green fluorescent protein (GFP) suggest that POMC neurons do not directly sense glucose (40–42). On the other hand, other studies using distinct POMC-GFP and other transgenic mice as well as a POMC-derived cell line suggest that glucose may directly excite POMC neurons via AMPK-linked KATP channels. However, several of these studies used supraphysiological glucose concentrations (43–45). In these POMC neurons, AMPK regulation of the hypoxia-sensitive nuclear transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha may play a role in glucose sensing (46). In contrast to ARC POMC neurons, glucose sensing by VMN GE neurons is unaffected by AMPK modulators (40).

GE neurons most likely respond to changes in glucose metabolism (vs the glucose molecule per se), since glycolytic flux through GK, AMPK, and the KATP channel all depend on intracellular metabolism. Moreover, inhibition of glucose metabolism also inhibits GE neurons (28). However, it is also possible that metabolism-independent GE neurons exist. This mechanism may explain glucose sensing in those GE neurons that lack GK (31).

For example, the sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) 1 is also expressed in about 25% of VMH GE neurons. The SGLT1 couples glucose transport to an inward (excitatory) sodium current, which could contribute to glucose-induced depolarization (31).

Finally, of the GE neurons described, the ARC POMC and LH MCH neurons play a clear role in whole body energy homeostasis (47), while the GnRH GE neurons are likely to coordinate reproductive status with energy availability (36). On the other hand, VMN GE neurons appear to play a role in hypoglycemia detection and the development of HAAF (48). Moreover, VMN GE neurons have been shown to be exquisitely sensitive to decreases in glucose below 2 mM (Km = ~0.5mM), which would be associated with peripheral hypoglycemia (49). Because the focus of this chapter is hypoglycemia detection, only VMN GE neurons will be discussed.

GI neurons

As mentioned previously, GI neurons are found in many locations that also contain GE neurons, including the VMN, ARC, PVN, LH, subfornical organ (SFO), DVC, and amygdala (18, 24, 32, 33, 38). However, GI neurons have not been found in the anterior hypothalamus where GnRH neurons are located. Since these experiments focused only on the GnRH neurons, it is possible that GI neurons may be found in other cell populations in this region (36). GI neurons exist in both the ARC and the VMN regions of the VMH (22, 41). In the ARC, about half of the orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons are GI neurons (41). Because most NPY neurons coexpress γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), it is possible that the NPY-GI neurons release GABA (47). On the other hand, VMN GI neurons may be glutamatergic. Tong et al showed that when the vesicular gluta-mate transporter, vGlut, was deleted in steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1; marker for the VMN) neurons, release of adrenal E and glucagon in response to hypoglycemia was impaired (50). As will be discussed, the atypical neurotransmitter nitric oxide (NO) may also be released from VMH GI neurons when glucose decreases. Finally, LH GI neurons express the peptide orexin (51). Thus, in terms of transmitter release, GI neurons are phenotypically diverse.

As discussed previously for GE neurons, GK is also necessary for glucose sensing in the majority of VMH GI neurons (30). Moreover, like GE neurons, about twice as many VMH GI neurons as nonglucose-sensing neurons express both the insulin receptor and GLUT4 (31). Reduced expression of the neuronal insulin receptor is associated with a blunted response of VMH GI neurons to decreased glucose and impaired glucose counter-regulation (52). However, while many VMH GE neurons do not appear to use AMPK to sense glucose, this enzyme is critical for glucose sensing in VMH GI neurons (53). Moreover, a feed-forward relationship between AMPK and NO is essential for VMN (but possibly not ARC-NPY) GI neurons to sense decreased glucose (53, 54). Decreased glucose activates AMPK, which phosphorylates the neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) leading to NO production. NO then binds to its receptor, soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and raises cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels. Increased cGMP causes a further activation of AMPK, which is necessary for closure of a chloride channel, possibly the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR). The reduction in chloride conductance depolarizes GI neurons, leading to increased action potential frequency (53). The mechanism by which cGMP enhances AMPK activity is not known. However, it may be via activation of an upstream AMPK kinase as has been shown for endothelial cells (55). What is clear is that the AMPK-NO pathway is essential. Blocking nNOS or sGC prevents decreased glucose or AMPK activators from depolarizing GI neurons. Conversely, AMPK inhibition prevents cGMP-induced activation of GI neurons (53). Thus, in VMN GI neurons full AMPK activation requires both a glucose decrease and AMPK-dependent NO production in order to close the chloride channel. Whether NO in VMN GI neurons is only needed for depolarization in response to decreased glucose or whether NO might diffuse to adjacent cells and alter their activity is not known.

Similar mechanisms may confer glucose sensitivity to the hindbrain catecholamine neurons, which increase cfos expression during hypoglycemia or glucoprivation (56). Blockade of AMPK phosphorylation and administration of the GK inhibitor, glucosamine, in the hindbrain both reduce glucoprivic feeding (57). In addition, the glucose analog 2 deoxyglucose (2DG), which cannot be metabolized, mimics the effects of low glucose in a subgroup of hindbrain catecholamine neurons, indicating their responsiveness to glucose deficit and suggesting a GI phenotype (56). However, strong support of this supposition will require electrophysiological evidence demonstrating their intrinsic responsiveness to glucose, which is not available at this time. Therefore, to be conservative, the authors will refer to these neurons simply as hindbrain catecholamine (or norepinephrine [NE] and E) neurons.

In addition to the VMH GI neurons, GK is expressed in GI neurons in the amygdala and DVC; however glucose-sensing mechanisms have not been fully explored in these regions (32, 33). Interestingly, glucose appears to open a KATP channel and inhibit SFO GI neurons (18). While VMH GI neurons use KATP channels to respond to changes in extracellular lactate, this KATP channel does not play a role in glucose sensing (49). In contrast to the metabolically dependent GI neurons, 2DG inhibits LH orexin neurons (58). This suggests that LH orexin neurons respond to the glucose molecule per se. While the identity of this glucose receptor is unknown, as mentioned previously, the sweet taste receptor and the SGLT are interesting candidates. Various ion channels have been proposed; however, the exact mechanism has not been established (59, 60).

Nonneuronal Glucose Sensors

In addition to neuronal glucose sensors, glial cells also may play a role in glucose sensing and hypoglycemia detection. Specialized ependymal cells known as tanycytes, which line the ventral portion of the third ventricle, are interesting candidates. These cells are in direct contact with the cerebrospinal fluid on 1 side and extend processes deeply into the VMN and arcuate nuclei. While they do not appear to communicate via action potentials, they are electrically coupled and propagate calcium signals. Glucose and glucose analogues pulsed onto tanycytes increase intracellular calcium levels (61). Tanycytes also express GLUT2 and KATP channels (61, 62). The toxin alloxan, which destroys GK-expressing cells, kills tanycytes and impairs the CRR. Interestingly, during HAAF, the tanycytic processes projecting into the VMH retract. However, 2 weeks after the last hypoglycemic episode when the CRR is restored, tanycytic projections are once again found within the VMH (62). Astrocytes also possess GLUT2 and may play a role in glucose sensing. Inhibition of carbohydrate metabolism, specifically in astrocytes, blunts insulin secretion in response to intracarotid glucose injection (63). Glucagon secretion and brainstem c-fos activation in response to peripheral or central 2DG are blunted in mice lacking GLUT2. Restoring GLUT2 expression in astrocytes but not neurons normalizes both the glucagon response and brainstem c-Fos activation (64). These data suggest that interaction between glial cells and neurons is necessary for normal hypoglycemia counter-regulation.

Brain Glucose Sensors and Glucose Counter-regulation

As mentioned previously, glucose-sensing cells of various types are distributed widely in the brain and peripheral tissues. The specific functions of neuronal glucose-sensing cells depend not only upon their glucose-sensing characteristics, but also upon their neural connections. While it is reasonable to expect that most glucose-sensing neurons contribute to metabolic homeostasis at some level (cellular, local or systemic), assigning specific roles to the majority of these neurons is limited by incomplete anatomical and physiological information. Historically speaking, the hypothalamus and the hindbrain have received the greatest attention with respect to their glucose-sensing potential, due to their demonstrated roles in control of food intake and metabolism. Glucose sensors within both hypothalamic and hindbrain sites contribute importantly to glucose homeostasis, but their roles in this complex process appear to differ, as will be discussed. In the hypothalamus, the most complete information regarding hypoglycemia detection and counter-regulation is available for VMN GE/GI neurons. Prominent among glucoregulatory neurons in the hindbrain are NE and E neurons. Therefore, the functional characteristics of the VMN and hindbrain glucose sensors will be covered.

Hypothalamic Glucose Sensing and Counter-regulation

Before proceeding, it is necessary to distinguish between the VMN and the VMH as referred to in studies highlighted. It is very difficult for in vivo injection or microdialysis studies to distinguish between the VMN and ARC due to the close proximity of these nuclei. For accuracy, therefore, these types of studies will simply refer to the VMH, as will in vitro studies that dissect the entire VMH. However, it is quite likely that VMN glucose-sensing neurons are responsible for observed VMH effects, since the ARC NPY-GI neurons do not appear to play a clear role in hypoglycemia detection (65), and glucose sensing by ARC POMC neurons is controversial (41). On the other hand, genetic deletion studies using the VMN marker, SF-1, and electrophysiology studies, which visually identify the VMN, will refer to the VMN directly.

In the late 1980s, counter-regulatory hormone secretion during moderate or deep hypoglycemia was reported to be independent of hypothalamic glucose sensors (66). In contrast, others showed that brain glucose sensors were important, especially with regard to glucagon secretion (67). Since this time, several studies have suggested an important in vivo role for VMH glucose sensors in the adrenomedullary, as well as glucagon, response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia both under control conditions and during HAAF. Specific VMH lesions with ibotenic acid suppressed adrenal E and NE and glucagon responses to hypoglycemia by 50-80% each, depending on the degree of hypoglycemia (68). VMH glucoprivation with 2DG caused hyperglycemia and profoundly augmented these hormonal responses (eg, increasing adrenal E levels 30-fold) (69). Moreover, VMH glucose perfusion during peripheral hypoglycemia reduced adrenal E and NE and glucagon release by up to 85% (9). Interestingly, this augmentation of the CRR by VMH glucoprivation was potently reduced following recurrent hypoglycemia (70). Moreover, antecedent hypothalamic glucoprivation with 2DG reduced adrenal E and glucagon responses to hypoglycemia by 50% (71). On the other hand, corticosterone secretion and feeding appear to be unaffected by recurrent hypoglycemia, antecedent glucoprivation, or manipulation of the VMH (71–74). These data suggest that the VMH plays an important role in 2 of the major aspects of the CRR: adrenomedullary activation and glucagon secretion. On the other hand, the VMH may not influence corticosterone secretion and glucoprivic feeding. Together, these data provide a strong link between impaired VMH glucose sensing and impaired adrenomedullary hormone and glucagon secretion during HAAF. The role of specific VMN glucose-sensing neurons will be described.

VMN GE Neurons and Glucose Counter-regulation

A role for KATP-dependent GE neurons in hypoglycemia detection is supported both by in vitro electrophysiological and in vivo studies. During HAAF, blood glucose levels must fall further before the CRR is initiated. Similarly, extracellular glucose levels must fall further before VMN GE neurons are inhibited following recurrent hypoglycemia (10). GE neurons are absent, and hypoglycemia-induced glucagon release is reduced in mice lacking the pore-forming unit of the KATP channel, Kir6.2 (75). VMH injection of the KATP channel opener, diazoxide, amplifies adrenal E and glucagon release and decreases the glucose infusion rate needed to maintain hypoglycemia during a hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamp while blockade of VMH KATP channels with glibenclamide does the converse (76, 77). Coinjection of the GABA A agonist, muscimol, with diazoxide, or of the GABA A antagonist, bicucculline, with glibenclamide, blocked the effects of the KATP channel modulators. Conversely, VMH glibenclamide increases, while diazoxide decreases local GABA release (78). VMH GABA levels are reduced by diabetic hypoglycemia, and GABA tone is elevated during HAAF (57, 79). Reducing VMH GABA tone during HAAF restores both adrenomedullary E and glucagon responses to hypoglycemia (79). More importantly, reducing VMH GABA tone restores the glucagon response to hypoglycemia in diabetic rats in which glucagon secretion is absent under basal conditions (57). Together, these data suggest that KATP-dependent GE neurons may belong to a population of GABA interneurons within the VMH. This is consistent with single-cell reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) studies showing that approximately half of VMH GE neurons express the GABA synthetic enzyme, GAD (31). Thus during hypoglycemia, reduced glucose would inactivate GE neurons and reduce VMH GABA release. Decreased inhibitory GABA signaling may then play a role in stimulating adrenal E and glucagon secretion.

VMN GI Neurons and Glucose Counter-regulation

A stronger body of evidence suggests that VMN GI neurons play a role in the response to hypoglycemia. The glucose sensitivity of VMN GI neurons parallels the ability of the brain to sense and respond to hypoglyce mia under a number of conditions (10). As with VMN GE neurons, larger declines in extracellular glucose are required for the same degree of activation of VMN GI neurons following recurrent hypoglycemia (80). VMH injection of lactate or the corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor 2 agonist, urocortin, impairs adrenal E and glucagon release during acute hypoglycemia by over 55% (74, 81). Similarly, including lactate or urocortin in the bathing media blunts the response of VMN GI neurons to decreased glucose (49, 74). In contrast, VMH AMPK activation in vivo more than doubled adrenal E and glucagon secretion after recurrent hypoglycemia (82). Incubating brain slices with an AMPK activator also restores normal glucose sensitivity to VMN GI neurons following recurrent hypoglycemia (Figure 2-1), while AMPK inhibition blunts their response to glucose decreases (53, 83). Moreover, altering VMH NO signaling either in vitro or in vivo results in parallel changes in the glucose sensitivity of VMN GI neurons or the CRR, respectively (10). These data strongly suggest that VMN GI neurons play an important role in the CRR, at least in terms of glucagon and adrenal E release. However, other glucose sensors are also involved. In support of this, while the CRR was significantly blunted, it was not abolished in nNOS knockout mice, which completely lack VMN GI neurons (10).

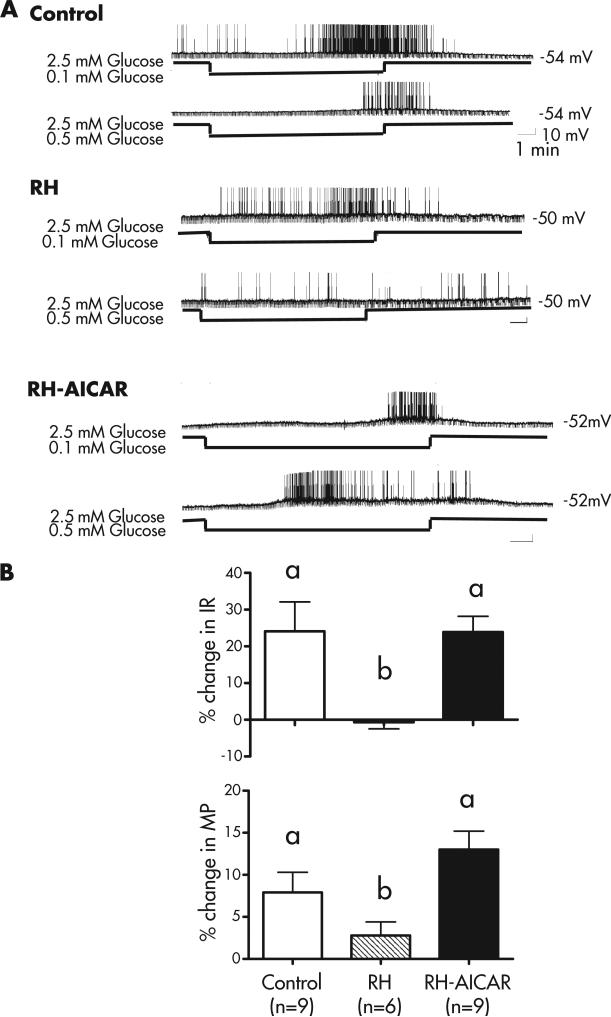

FIG 2-1.

(A) Representative current-clamp recordings of VMN GI neurons in brain slices from 2- to 3-week old male Sprague-Dawley rats. Control and recurrently hypoglycemic (RH) rats were injected once daily for 3 consecutive days with either saline (control) or insulin (4 U/kg; RH). On day 4, all rats were sacrificed, their brains sliced into 300 μm sections, and patch-clamp recording performed as described previously (80). Brain slices from control and 1 subset of RH rats were studied in the absence of further treatment. Brain slices from another subset of RH rats were treated with the AMPK activator, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-b-4-ribofuranoside (AICAR, 0.5 mM) in the bathing medium for 15 minutes (RH-AICAR group). AICAR was then washed out, and glucose sensitivity was evaluated from 1 to 5 hours after treatment. The top trace in each group represents the neuronal response to a glucose decrease from 2.5 to 0.1 mM and the bottom trace a glucose decrease from 2.5 to 0.5 mM. Resting membrane potential is given to the right of each trace. The downward deflections represent the membrane response to a constant hyperpolarizing pulse of −20 pA given for 500 milliseconds every 3 seconds. VMN GI neurons from control rats were reversibly activated by glucose decreases to both 0.5 and 0.1 mM, whereas GI neurons from RH rats were only activated by the maximal glucose decrease to 0.1 mM. AMPK activation (RH-AICAR) completely restored the response to 0.5 mM glucose. (B) The data in (A) were quantified as the percent change in input resistance (IR) and membrane potential (MP) in 0.5 mM glucose compared to that in 2.5 mM for each group. In GI neurons from controls, decreasing glucose to 0.5 mM increased IR and MP by ~25% and 8%, respectively. However, in GI neurons from RH rats, the increase in IR and MP was significantly reduced or abolished. Treating the brain slices with AICAR completely restored the response to 0.5 mM glucose. The data were analyzed by 1 way ANOVA followed by post hoc test. Different letters represent statistically different groups (P <0.05). (Panel A: Control and RH traces and B: IR values for control and RH reproduced with permission from Song Z, Routh VH. Recurrent hypoglycemia reduces the glucose sensitivity of glucose-inhibited neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus nucleus (VMN). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291(5):R1283.).

Connections of the VMN that May Mediate Counter-regulatory Responses

While VMN glucose sensors are clearly important in hypoglycemia detection and the CRR, efforts to delineate their exact function have been hampered, because their peptide phenotype is unknown. The VMN contains neurons expressing peptides relevant to energy and/or glucose homeostasis, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating peptide (PACAP). GABA and glutamate neurons are also found in the VMN, as are those expressing nNOS (84). As mentioned previously, a role for VMN amino acid transmitters GABA and glutamate has been suggested in hypoglycemia detection. For example, deleting vGlut in SF-1 neurons that are specific for the VMN impairs adrenal E and glucagon secretion (50). Moreover, there is considerable overlap between GI neurons and nNOS/NO signaling (85), and adrenal E release in response to insulin-hypoglycemia is impaired in nNOS knockout mice that lack VMN GI neurons (10). The afferent and efferent connections of the VMN are complex and will only be covered briefly in this chapter. For a complete discourse on the topic, the reader is referred to an excellent review by Bruce King (84). This review supports an integrative role for the VMN based on its juxtaposition between autonomic regulatory and higher limbic sites, especially with regard to stress circuitry. The VMN receives extensive reciprocal input from limbic regions such as the amygdala and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the latter a relay within the hypothalamic-pituiitary-adrenal axis. The VMN receives input from other hypothalamic areas including the LH and the suprachiasmatic nucleus. VMN axons as well as dendrites project widely throughout the hypothalamus including to the PVN, dorsomedial nucleus, and LH. The VMN also projects to the midbrain reticular formation (84). It is this latter connection that enables the VMN to provide input to the sympathetic preganglionic neurons within the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord. Thus, while the exact phenotype and neurocircuitry influenced by VMN glucose sensing neurons is not known, the potential for impacting those neural circuits involved in hypoglycemia detection and the CRR is clear.

Future Directions: VMN Glucose Sensing

The previous discussion clearly points to an important role for VMN glucose-sensing neurons in hypoglycemia detection and the CRR. However, it is also clear that there are many unanswered questions that must be addressed in future studies. Foremost among these is the neurotransmitter phenotype of both VMN GE and GI neurons. Once this is known, studies with transgenic animals, in particular conditional gene deletion of these transmitters within VMN neurons, will provide information regarding the relative importance of these neurons to the CRR. In addition, identification of transmitter phenotype will enable similar tract tracing studies, as those described for the brainstem, which define the neuroanatomical pathways by which VMN glucose-sensing neurons impact the CRR. Finally, the most important unanswered question involves the way that information provided by the various central and peripheral glucose sensors interacts to coordinate the CRR under normal and pathological conditions.

Hindbrain Glucose Sensing: NE and E Neurons and Their Roles in Counter-regulation

Mapping studies using nanoliter injections of 5-thioglucose (5TG) (86), an antiglycolytic agent similar to 2DG, have revealed hindbrain sites from which feeding, the adrenal medullary hyperglycemic, glucagon, and corticosterone responses can be elicited by localized glucose deficit (87, 88). Sites positive for 1 response were nearly always positive for all 4 responses. At tissue sites, there is an approximately fourfold greater sensitivity to 5TG than at ventricular sites, indicating that the responses are elicited by mechanisms existing at the injected sites and not by diffusion through the ventricular system to distant sites. Localized injections of 5TG into hypothalamic tissue sites, including those in VMH nuclei, were not effective in eliciting any of the counter-regulatory responses, even when higher doses were administered. These data suggest that hindbrain glucose detection sites are the elicitation sites for the feeding, adrenal medullary secretion, and corticosterone responses to systemic glucoprivation. These findings are consistent with previous results showing that localized 2DG injections into hypothalamus and other forebrain sites are ineffective in eliciting feeding (89, 90), and data showing that feeding and hyperglycemia elicited by lateral ventricular 5TG injection are blocked by occlusion of the cerebral aqueduct, which prevents the 5TG from perfusing the hindbrain (91). The distribution of hindbrain sites where these responses can be elicited by localized gluco-privation is similar to the known distribution of NE and E cell groups in which systemic glucoprivation increases expression of c-Fos (11), a marker of neuronal activation, and induces the genes for dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (DBH) (92) and co-expressed NPY (93). Lesion studies, discussed below, also provide critical data. Selective lesion of hindbrain NE and E neurons eliminates the feeding, adrenal medullary and corticosterone responses to systemic glucoprivation, indicating that these neurons are required for glucose CRR.

Early work demonstrated that NE and E are potent orexigenic agents (94, 95) that exert control of corticosterone-releasing hormone (CRH) and thus, of corticosterone secretion (96). Glucoprivation is a potent activator of NE and E neurons, and increases NE and E release and turnover in the hypothalamus, where they form dense terminal networks (8, 97–100). Pharmacological blockade of NE and E neurotransmission reduces glucoprivic feeding (101). In accord with these findings, a recent report has shown that stimulation of the β2 adrenergic receptor by local agonist injections targeting the VMN enhances glucagon and adrenal E release induced by hypoglycemia (102). Another potentially important role of NE during glucoprivic conditions is that it stimulates a glycogenolytic response in astrocytes and stimulates astrocyte glucose uptake, utilization, and glycogen turnover (103, 104), which may provide an immediate neuroprotective action. Together, these findings strongly indicate that NE and E neurons are activated by glycemic challenge and participate in glucose counter-regulation.

Chemical microdissection using the retrogradely transported immunotoxin, anti-DBH saporin (DSAP), which selectively targets DBH-expressing (ie, NE and E) neurons (105), has been a useful tool for studying the role of these neurons in glucose counter-regulation (56, 106). Injection of DSAP into the PVN, which selectively and retrogradely destroys DBH neurons innervating the medial hypothalamus, impairs or abolishes feeding (107), corticosterone (108), and adrenal medullary responses (107) to both insulin-induced hypoglycemia and 2DG-induced blockade of glycolysis; it also abolishes the suppression of estrous cycles that are normally induced by chronic glucoprivation (109, 110). DSAP does not impair daily feeding or feeding stimulated by short-term (overnight) food deprivation and does not impair feeding in response to mercaptoacetate (107), a drug that inhibits fatty acid oxidation (111). The feeding deficit caused by the lesion of hypothalamically projecting catecholamine neurons appears to be selective for glucoprivic (or counter-regulatory) feeding. The characteristics of glucoprivic responses at the behavioral level provide strong support for the nonintegrative nature of this control. That is, the hind-brain glucose-sensing neurons, unlike some hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurons (42, 49, 112), may not be sensitive to availability of other metabolic substrates. Glucoprivation stimulates feeding and other CRRs even in the presence of elevated body adiposity (113), in satiated animals and during chronic leptin administration (114). Feeding in response to 2DG is blocked by glucose, but not by coadministration of intravenous fatty acids (115).

Of the functionally and phenotypically heterogeneous population of ascending catecholamine neurons, those required for glucoprivic feeding appear to be those that coexpress NPY. Global deletion of the NPY gene (Npy) impairs glucoprivic feeding (65, 116), whereas localized lesion of arcuate neurons coexpressing NPY and agouti gene-related peptide (AgRP) neurons does not (65, 113). Results using small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology show that simultaneous (but not separate) silencing of Npy and Dbh, localized to the area of A1/C1 overlap in the ventrolateral medulla, reduced the glucoprivic feeding response to only 39% of the intake of controls injected with nontargeted RNAs and did so without impairing the feeding response to another metabolic stimulus, mercaptoacetate-induced blockade of fatty acid oxidation (117). These data, combined with the fact that the largest numbers of DBH-NPY coexpressing neurons are located in the A1 and C1 cell groups in the ventrolateral medulla, suggest that the latter NE and/or E neurons, rather than those in the A2/C2 cell group in the dorsomedial medulla (ie, dorsal vagal complex) are the primary mediators of counter-regulatory feeding. Other data supporting this localization include the finding that phosphorylation of AMPK, an energy-sensing mechanism, is increased in response to glucoprivation in A1/C1, but not significantly in the A2 area (23). Phosphorylation of AMPK is not increased in the A1/C1 area of the hindbrain in rats in which the catecholamine neurons have been eliminated by PVH injection of DSAP. In addition, nearly all NE and E neurons in A1 and C1 area express c-Fos in response to 2DG or hypoglycemia, whereas only a very few A2 neurons in the dorsal hindbrain express c-Fos in response to a glucoprivic stimulus (23). Other work has demonstrated that A2 neurons may participate in the satiety actions of gut peptides (118–120), suggesting a role for these neurons that differs from the catecholamine neurons in the ventrolateral medulla. Nevertheless, several feeding deficits are produced by lesion of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and area postrema, and these include impairment of glucoprivic feeding (121–123).

Although it is possible, and even likely, that catecholamine neurons involved in glucose counter-regulation are distributed across several catecholamine cell groups and include both dorsal and ventral sites, the distribution of NE and E neurons that are directly glucose-sensing is not known. Responsiveness of A1/C1 neurons to glucose and other energy-related signals has not been examined in electrophysiological experiments. Furthermore, in the NTS, where about 10% of the total population of neurons are estimated to be GI and 10% GE (33), it is not known whether any of these glucose-sensing neurons are catecholaminergic. On the other hand, results from a laser capture microdissection experiment suggest that some NE neurons in the NTS may express GK (33), which is thought to be present only in glucose-sensing neurons. Electro-physiological characterization of hindbrain catecholamine neuron responsiveness to glucose is an area in need of investigation.

Stimulation of Corticosterone Secretion by Glucose Deficit

Retrograde destruction of hindbrain NE and E neurons by PVN injection of DSAP eliminated 70% of the corticosterone response to both hypoglycemia and 2DG seen in SAP controls (108). The transcriptional response of CRH neurons to glucose deficit was also reduced. It is noteworthy that in DSAP-lesioned rats, the corticosterone response to swim stress and the circadian rhythm of corticosterone secretion did not differ from controls, and in situ hybridization revealed that the CRH cell population was intact, indicating that the deficient response to glycemic challenge was not due to CRH neuron damage. Additional studies have shown that local NE injections into the PVN also produce transcriptional and secretory responses, and furthermore, that mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling cascades transduce the effects of NE on CRH cellular activation and secretion (124, 125). Sensitivity of CRH neurons to glucoprivic activation is subject to circadian influences mediated by other inputs to the PVN neurons (126). Thus, while corticosterone secretion is elicited by many different stimuli and by multiple pathways, catecholamine neurons appear to elicit the CRH/corticosterone CRR to glucose deficit.

Stimulation of Adrenal Medullary Secretion by Glucose Deficit

Adrenal medullary secretion of E is a crucial response to glucose deficit, because circulating E rapidly and robustly mobilizes stored glucose and preserves it for use by the brain by mobilizing and promoting uptake of lipids as an alternative fuel for glucose in peripheral tissues. It additionally suppresses insulin secretion, which reduces peripheral glucose uptake. Adrenal medullary secretion is entirely dependent on neural activation by sympathetic preganglionic neurons with cell bodies concentrated in the intermediolateral column (IML) of the spinal cord between spinal levels T7 and T10. These preganglionic neurons in turn are controlled by spinally projecting neurons from the brain. Evidence has been accumulating to suggest that preganglionic neurons innervating the adrenal medulla are directly controlled by and require hindbrain catecholamine neurons that respond to glucoprivation. In rats, glucoprivation elicits intense activation of the adrenal medulla in the absence of generalized sympathetic arousal. Sympathetic preganglionic neurons between T7 and T10, retrogradely labeled from the adrenal medulla for clear identification, as well as adrenal medullary cells themselves, heavily express c-Fos in response to 2DG (127). In contrast, preganglionic neurons in other cord levels retrogradely labeled from celiac or superior cervical ganglia express very little c-Fos in response to 2DG.

Glucoprivic activation of adrenal medullary preganglionic neurons even appears to be selective for those neurons that innervate adrenal medullary E-secreting, as opposed to NE-secreting, chromaffin cells, as demonstrated recently by in vivo intra-adrenomedullary dialysis of NE and E in freely moving, unanesthetized rats (128, 129). Differential control of presumed NE- and E-secreting cells in the adrenal medulla itself by presympathetic motor neurons with distinct functional and electrophysiological characteristics has also been demonstrated (130). Those controlling E secretion are strongly activated by glucoprivation but are insensitive to baroreceptor reflex activation, while those presumed to control NE secretion are strongly stimulated by baroreflex activation, but unaffected by glucoprivation. The 2 types of supraspinal presympathetic neurons in this study were also shown to have different latencies to respond to electrical stimulation of the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Those responding to baroreceptor reflex activation responded with short latency, while those responding to glucoprivation had long latency responses and were largely unmyelinated. More recent work by has shown that separate populations of neurons respond to systemic glucoprivation and to baroreceptive stimulation and that each population can be manipulated to produce specific glucose or blood pressure responses (131). Thus, it appears that the physiological responses of the adrenal medulla are narrowly tuned and tightly controlled by anatomically and physiologically discrete central neurons driven by distinct sensory signals.

Hindbrain E neurons with cell bodies in C1-C3 and spinal projections to sympathetic preganglionic neurons of the IML control the adrenal medullary response to glucoprivation. Selective retrograde destruction of these bulbospinal E neurons by intraspinal injection of the targeted toxin, DSAP, abolishes the elevation of plasma E, as well as the hyperglycemic and adrenal medullary c-Fos responses to glucoprivation (106, 107). In addition, Madden et al (132) reported that injection of DSAP directly into the C1 cell group severely impaired the adrenal medullary response to systemic glucoprivation, further suggesting that the effects of intraspinal DSAP injection were not due to nonspecific spinal damage (as indicated also by the normal response of the controls injected with unconjugated saporin). Together, these findings indicate that bulbospinal E neurons are required for the adrenal medullary response to glucoprivation and that the C1 cell group is of particular importance for that response.

It is important to recall that the hindbrain neurons responsible for glucoprivic stimulation of the adrenal medulla do not require forebrain input for activation by this stimulus, as indicated by experiments in decerebrate rats (133). Nevertheless, forebrain neurons may contribute to the function of these hindbrain neurons in the intact animal. For example, these neurons may be a final common path for adrenal medullary control that can also be activated by other inputs, such as the VMN.

Afferent and Efferent Connections of Hindbrain Catecholamine Neurons

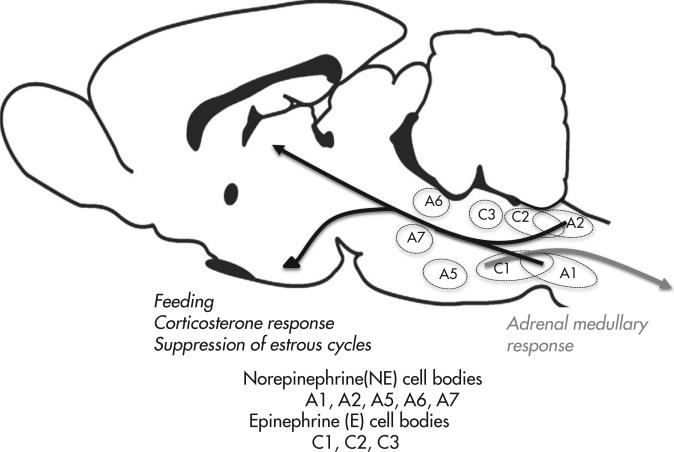

A large body of work has provided information regarding the projections of distinct groups of hindbrain catecholamine neurons (Figure 2-2). Less is known regarding the afferent input to these neurons. The different clusters of neurons are named A1, A2, A5, A6, A7 (NE groups) and C1, C2 and C3 (E groups). Importantly, neurons comprising each distinct grouping do not necessarily innervate the same targets or participate in the same physiological processes. For example, A1 and A2 project only rostrally, A7 only caudally; C1-3, A5, and the A6 complex contain subgroups of neurons, some of which project rostrally and some caudally. As mentioned, neurons making up each group do not necessarily share the same function. For example, the most rostral portion of cell group C1 contains neurons that mediate cardiovascular responses to baroreceptor stimulation (131), whereas the central and caudal sections of C1 contain neurons that participate in adrenal medullary and feeding responses to glucoprivation. These features underline the necessity for detailed phenotyping and tracing of anatomical projections of catecholamine neurons for correct assessment of their individual functions.

FIG 2-2.

Diagrammatic view of a sagittal section through rat brain showing the approximate locations of the hindbrain catecholamine cell groups and the trajectories of the groups discussed in this review. Cell groups A1, A2, and C2 project rostrally. Cell group A7 projects spinally. Groups A5, A6, C1, and C3 project both rostrally and spinally. The spinal projection from C1 arises from cell bodies concentrated in the most rostral portion of the cell group, while the forebrain-projecting cells are located in the middle and caudal portions of C1. Cell groups also project locally and innervate sites within the hindbrain and midbrain. Catecholamine neurons are highly collateralized in their projection and innervation patterns (134, 135). Black arrows show cell groups damaged by injection of the retrograde immunotoxin, antidopamine-beta-hydroxylase saporin (DSAP), into the medial hypothalamus. These include catecholamine neurons that stimulate feeding and secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone and suppression of estrous cycles in response to glucoprivation (107, 108, 110). The gray arrow indicates neurons in rostral C1 that innervate sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral column of the thoracolumbar spinal cord and give rise to the adrenal medullary response to central glucoprivation. Cells in this location (and other spinally projecting catecholamine cell groups) are damaged by intraspinal injection of DSAP (107).

One common feature of most NE and E neurons is that they are highly collateralized and distribute their terminals widely throughout the brain or spinal cord. This makes them well suited for the rapid and highly orchestrated control of diverse autonomic, behavioral, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses necessary for survival of glucose deficit. In addition, catecholamine neurons both innervate orexin cell bodies and coinnervate many of the same terminal sites as orexin neurons (136). Although the functional significance of this innervation pattern for glucose counter-regulation is uncertain, this pattern is consistent with emerging evidence suggesting that orexin neurons link homeostatic requirements to appropriate arousal and activity levels (60). Similarly, there is direct interaction between NPY/AgRP neurons and NE and E neurons, which heavily inner-vate them. It is accepted that NPY/AgRP neurons play a pivotal role in integration of metabolic signals and control of daily feeding and energy homeostasis (137), functions that serve to avert metabolic crisis. Activation of catecholamine neurons by glucoprivation induces expression of Agrp and Npy (138, 139), an effect one would expect to enhance feeding and other features of these neurons that would be supportive of glucorestoration. The induction of Agrp and Npy by glucoprivation requires input to AgRP and NPY neurons from hindbrain catecholamine neurons and does not occur in animals in which the catecholamine innervation has been destroyed by DSAP injection. Thus, while NPY/AgRP neurons are not required for glucoprivic feeding, hyperglycemic or corticosterone responses, activation of their circuitry by hindbrain catecholamine neurons may serve to potentiate feeding or other responses of importance during acute glucoprivation. In addition, in the PVN DSAP-injected rat, the expression of both Npy and Agrp appears to be chronically enhanced under basal conditions (139), possibly indicating a role for these neurons in adaptation to or compensation for the partial loss (ie, loss of the ascending component) of the catecholamine counter-regulatory system. This adaptation may confer increased survival potential. These interconnecting circuits linking NE/E neurons with orexin and NPY/AgRP neurons provide potential avenues for linking daily feeding and arousal mechanisms with the circuitry required for hypoglycemia counter-regulation.

Future Directions: Hindbrain Glucose Sensing

Hindbrain catecholamine neurons are required for key glucoregulatory responses, including glucoprivic feeding, corticosterone secretion, adrenal medullary secretion, and the adaptive physiological response of suppression of estrous cycles. Future work is required to determine which particular cell bodies are required for each glucoregulatory response. When this is accomplished, work can then proceed to determine whether these catecholamine neurons themselves are glucoreceptive or whether they are activated indirectly by other hindbrain cell types (eg, astrocytes, epenymocytes, or other neurons) that detect and signal glucose availability. In addition, the cellular mechanisms utilized for glucose detection and the connections and circuitry of these neurons can then be established, including those that may enable interaction with VMH and PMV systems discussed in this review. Given the essential nature of these catecholamine neurons for glucose counter-regulation and homeostasis, it is clear that a more complete understanding of their mechanisms of glucose sensing and circuitry is crucial for understanding HAAF and its pathogenesis and prevention.

Unresolved Issues in Brain Glucose Sensing and Glucose Counter-regulation

Several pieces of data discussed so far in this review appear to be contradictory. First, the data from cannula mapping studies indicate that feeding, adrenal medullary, corticosterone, and glucagon responses can be elicited from the hindbrain by unilateral injections of nanoliter volumes and doses of 5TG that are completely ineffective throughout the hypothalamus. In contrast, the authors have also discussed the fact that the VMH has been studied extensively as an effective site for glucoprivic activation of glucagon and adrenal medullary secretion and has been shown to contain glucose-sensing neurons. These discrepant data encapsulate an important, but unresolved issue for which only speculative explanations can be offered. For example, previous work has shown that restriction of ventricular fluid to the forebrain ventricles severely impairs or blocks the hyperglycemic and feeding responses to lateral ventricle 5TG. Therefore, perhaps the larger doses and volumes of the antiglycolytic agent administered into the VMH, compared to those used for hindbrain injections, allow ventricular diffusion of the glucoprivic agent to hindbrain glucoreceptive sites. Or, perhaps hindbrain and hypothalamic sites controlling these responses possess glucose-sensing mechanisms that differ in their sensitivity to the magnitude or temporal development of the glucoprivic challenge, as appears to be the case with the PMV system. Specifically with respect to adrenal medullary secretion, a lesion of descending catecholaminergic projections to the sympathetic preganglionic neurons abolishes the response to systemic glucoprivation. This suggests that VMH activation of this response may be mediated by projections to hindbrain catecholamine neurons. However, it is important to note that decerebration studies have shown that the forebrain is not required for the adrenal medullary response to hypoglycemia. Specifically with respect to glucagon secretion, the authors have not found that DSAP injections reduce systemic 2DG-induced glucagon secretion (S Ritter, 2012, unpublished data). Although the direct effects on glucagon secretion of glucose and insulin within the pancreas itself may obscure a diminished central effect in an experiment of this type, these data also may indicate that the VMH plays a predominant role in central control of glucagon secretion. Finally, perhaps hindbrain and hypothalamic sites are differentially recruited for the adrenal E response based on the overall energy needs of the body. For example, the satiety hormones, leptin and insulin, mask the ability of VMH GI and GE neurons, respectively, to respond to glucose deficit, whereas fasting enhances activation of GI neurons by decreased glucose, in part due to decreased leptin levels (40, 140). Thus one might speculate that under normal energy balance, hindbrain catecholamine neurons are dominant with regard to the adrenal E response. However, during energy deficit, the VMH glucose sensors may be recruited to amplify the response, potentially via projections to hindbrain catecholamine neurons. This hierarchical activation for distinct central and peripheral glucose sensors will be considered in more detail in the conclusion section of this review. It will be important in future work to confront these apparent discrepancies and to design incisive experiments to resolve them.

Portal-Mesenteric Vein Glucose Sensors

As with the CNS, peripheral glucose sensors are widely distributed throughout the body. These include the oral cavity (141), intestines (142), PMV (143), and carotid body (144). Most of these are found along the alimentary canal and its associated vasculature, and they are generally associated with sensing elevations in glucose due to ingestion. However, 2 peripheral loci, the PMV and carotid body, have been implicated in hypoglycemic detection. The carotid body, a polymodal sensor, has been shown in vitro to respond to glucose, as well as pO2, pCO2, and pH. Its role in vivo is less clear, with conflicting reports as to the importance of the carotid body in detecting insulin-induced hypoglycemia (145, 146). In contrast, the role of the PMV in detecting hypoglycemia is established and will be the focus of this discussion.

The concept that the periphery retains glucose sensors capable of providing the CNS with information regarding the systemic glycemic status dates back to Mayer's proposed glucostatic theory (13). Russek (147) subsequently proposed the existence of hepatic glucoreceptors based on the anorexic effect of glucose administered intraperitoneal (IP) and its temporal relationship to portal glucose levels. Shortly thereafter, Niijima (148) identified afferents in the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve that were sensitive to portal vein glucose infusion. Additional evidence for portahepatic glucose sensing would accrue over the next 2 decades, which, along with the well known glucoregulatory efferent outputs from the CNS, led to several proposals for the existence of various hepatichypothalamic axes controlling hepatic, pancreatic, and adrenal outputs (147, 149, 150).

Portal-Mesenteric Glucose Sensors in Hypoglycemic Detection

Initially believed to be primarily involved in sensing the entry of ingested glucose, evidence has since emerged for a significant role of PMV glucose sensors in hypoglycemic detection. This was initially demonstrated using the local irrigation technique in which portahepatic glycemia was selectively normalized via portal glucose infusion during systemic hypoglycemia achieved with a hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamp. The premise of this approach is that normalizing glucose across a select region will blind any critical glucose sensors to the prevailing systemic hypoglycemia leading to suppression of the CRR. Utilizing this approach, it was shown that normalizing portahepatic glucose during moderate systemic hypoglycemia (3.25 mM) resulted in a 42% suppression in the adrenal E response to hypoglycemia (151). At deep hypoglycemia (2.5 mM), the effect of normalizing portal vein glucose concentration was even greater, with a 50% to 73% suppression in E and 42% to 67% suppression in NE (7, 152). Lamarche et al (153) confirmed the existence of portahepatic glucose sensors capable of detecting hypoglycemia, using a cross-perfusion technique that allowed them to establish hypoglycemia across the portahepatis during systemic euglycemia. Despite anesthetic conditions known to blunt the sympathoadrenal response, they demonstrated 2.5- and 3.5-fold increases in adrenal E and NE output, respectively, from the adrenal gland during selective portahepatic hypoglycemia. In addition, denervating just the portal vein results in a suppressed CRR to insulin-induced hypoglycemia, quantitatively comparable to the local irrigation technique described (154, 155).

PMV glucose sensors are particularly important in detecting slow-onset hypoglycemia (ie, ≤ 1 mg/dL • min−1) (12). When hypoglycemia develops slowly, the absence of PMV glucose sensory input results in severely diminished sympathoad-renal responses, achieving only 5% to 10% of normal. The compromised CRR during slow-onset hypoglycemia in PMV-denervated animals is accompanied by a substantial decrease in hindbrain neuronal activation (156). In contrast, the brain appears fully capable of responding to very rapid decrements in blood glucose (ie, ≥ 2 mg/dL • min−1), in the absence of portal-mesenteric vein glucose sensors (156). These findings are consistent with earlier studies that demonstrated a greater suppression of the catecholamine response to hypoglycemia when portahepatic glucose was normalized during a slow-stepped clamp (7) as opposed to a more rapid induction of hypoglycemia (152). The brain's inability to detect slow-onset hypoglycemia is further supported by studies of cognitive function demonstrating significantly greater impairment when hypoglycemia develops rapidly versus slowly (157). From a clinical standpoint, these observations are critical given the prevalence of slow-onset hypoglycemia. Physicians have long been aware that hypoglycemia generally develops over hours in the clinic as opposed to the very rapid inductions seen in the research setting. While quantitative data to support these observations have been scarce, a recent report employing chronically implanted sensors indicated that over 70% of all hypoglycemic episodes developed at rates ≤ 1 mg/dl • min−1 [158], ie, rates where PMV glucose sensors are critical for any significant CRR. Episodes that developed at rates for which the brain appears independent of PMV glucose sensory input (ie, ≥ 2 mg/dL • min−1) accounted for less than 10% of all hypoglycemic events.

Identifying the PMV Glucose-Sensing Locus

The precise locus for glucose sensors located in the portahepatic region was long thought to be the liver itself (159). This is despite the fact that it has been known for some time that the liver parenchyma of most species, including the rat and dog, is poorly innervated by comparison with the surrounding vasculature (160). That the locus for the portahepatic glucose sensors responsible for detecting hypoglycemia was actually in the portal vein was first reported by Hevener et al (20). By advancing the tip of the portal cannula adjacent to the liver, they were able to selectively elevate liver glycemia while maintaining the portal vein hypoglycemic. When this occurred, there was no effect on the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia. Only when both the portal vein and liver were normalized, did they observe suppression of the sympathoadrenal response, as reported earlier. This observation was confirmed when they demonstrated that normalizing liver glycemia via the hepatic artery during systemic hypoglycemia had no impact on the CRR (161). Consistent with a portal vein locus for hypoglycemic detection, several studies have demonstrated that selective denervation of the portal vein results in a suppressed response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia (12, 154, 155). The findings of Saberi et al (12) extended the locus to include the superior mesenteric vein. While denervating the portal vein alone was shown to suppress the adrenal E response by 61%, extending the denervation to include both the portal and superior mesenteric vein led to 91% suppression. For adrenal NE, portal-mesenteric denervation not only led to significantly greater suppression when compared to portal vein denervation alone, it effectively eliminated the slow-onset response to hypoglycemia. That the hypoglycemic sensing locus includes both the portal and superior mesenteric vein is not surprising given that they are only distinguished by a single tributary (ie, the gastrosplenic vein) and demonstrate similar rich innervation by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) reactive nerve fibers (12).

The PMV-CNS Neural Axis

The neural axis by which hypoglycemic sensory information from the PMV ascends to the brain has been the source of some confusion. Based on the early and extensive work by Niijima (148, 162, 163), it has generally been assumed that this information is communicated by hepatic vagal glucose sensitive afferents. This belief has been reinforced by the general perception that vagal afferents communicate specific chemosensory information, while spinal afferents transmit mechanosensory and noicioceptive inputs. Thus, the concept that all glucose sensory information from the viscera is mediated by vagal afferents remains firmly entrenched (164). However, to date there is no evidence to support the role of vagal afferents in the detection of hypoglycemia in vivo. Jackson et al (165, 166) were the first to address this by examining the effect of acute vagal blockade upon the CRR. By cooling the vagus nerve to 2°C, they effectively eliminated vagal transmission below the neck, but doing so had no effect upon the CRR. Fugita et al (167) would subsequently show that sectioning the hepatic vagus nerve, the purported axis by which portal vein glucose sensory information reaches the CNS, had no impact on the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia. Even when all vagal transmission below the diaphragm was eliminated via bilateral subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia remained fully intact (167). That the glucose sensitive vagal afferents are not involved in hypoglycemic detection is perhaps not surprising given their linear response over a wide range of portal vein glucose values (ie, 0 to 28 mM). Increasing portal glucose values from 0 to 28 mM led to a maximal suppression in hepatic vagal afferent firing rates of 23% to 87% (148, 162). Extrapolating these findings to glucose concentrations that define the transition from low euglycemia to deep hypoglycemia (ie, 4.0 to 2.5 mM), the projected increase in firing rate is only 2% to 6% across the entire range. This modest change in firing rate is inconsistent with the abrupt and substantial activation of sympathoadrenal output over the same range of glucose values, leading to a 30-fold increase in plasma E.

While most investigators have focused on vagal glucose sensitive afferents, an earlier report by Schmitt (168) proposed the existence of spinal glucose-sensitive afferents innervating the portahepatis. Based on the observed firing rates for LH neurons responding to portal glucose infusion, Schmitt demonstrated that both spinal transection at T5 and sectioning of the splanchnic nerve were effective in eliminating the response to portal glucose infusion, while sectioning both branches of the vagus failed to do so. The portal vein is richly innervated by spinal afferents as denoted by CGRP and substance P immunoreactivity (155, 160, 169), which are largely eliminated by sectioning the celiac-superior mesenteric ganglion (CSMG) or dorsal root rhizotomy at T8 to T13 (169, 170). Vagotomy, by contrast, was ineffective in decreasing the content of either CGRP or substance P (SP) in the portal vein (169, 170). Sectioning the CSMG has also been shown to induce marked blunting of the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia, indicative of a spinal origin for the portal vein glucose sensors detecting hypoglycemia (167). Although some vagal afferents originating from the celiac branch pass through the CSMG, this branching occurs caudal to the subdiaphragmatic sectioning of the vagus nerve, which was shown to have no effect on the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia. Topical application of capsaicin has been shown to substantially reduce CGRP reactivity in the portal vein and with it the ability for hypoglycemic detection at the portal vein (12, 155). Capsaicin acts through the transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1) receptor, which in the abdomen appears to be primarily associated with spinal afferents, with little expression in vagal afferents (171). Thus, hypoglycemic detection at the PMV appears to be mediated by spinal afferents, which likely originate at the thoracic level of the spinal column (ie, T8 to T13).

Evidence has accrued for functional connections between select areas of the CNS and the portal glucose sensors. Shimizu et al (6) reported that the majority of identifiable glucose-sensitive neurons in the LH also demonstrated inhibition with portal glucose infusion. Adachi et al (172) reported similar observations for glucose-sensitive neurons of the NTS, but constrained their observations to afferents arising from the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve. Alternatively, Schmitt (173) reported the existence of LH neurons that respond to portal glucose infusion, but appeared to be spinal in origin. While she did not characterize the innate glucose sensitivity of those neurons, she did note the existence of neurons demonstrating both excited and inhibited responses to portal glucose infusion. In all cases, these observations derive from very high concentrations of glucose infusates (ie, 280 to 1700 mM) and thus may not be relevant to hypoglycemic detection. However, more recently it has been shown that hypoglycemia-induced Fos activation in the hindbrain (NTS and AP) is largely eliminated by topical capsaicin treatment of the PMV (156). Suppression of the sympathoadrenal response to hypoglycemia was also reported, consistent with that observed with sectioning of the CSMG and distinct from that observed with total subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (167). While these data indicate a spinal axis for portal mesenteric glucose sensory input to the CNS under hypoglycemic conditions, very little is known regarding the anatomy of these neural connections. Presumably the critical portal-mesenteric afferents traverse the CSMG with their cell bodies located in the dorsal root ganglia at T8 to T13 (168). Berthoud (160) has suggested that the relevant dorsal horn projections may ascend via the spinosolitary and/or spinomesencephalic tracts to reach the NTS and parabrachial nucleus.

Peripheral Glucose-Sensing Mechanism

In contrast to central glucose sensing neurons, there is little evidence that peripheral nerves directly sense glucose. While it has recently been shown that vagal neurons isolated from the nodose ganglia can respond to changes in glucose concentration (170), all known peripheral glucose sensory mechanisms involve transduction of the glucose signal by a primary sensory cell. The most extensively studied of these is the taste receptor cell, which translates an oral glucose load into an increased firing rate of specific glossopharyngeal afferents. The mechanism involves glucose binding to the G-protein coupled sweet taste receptor, T1R2+T1R3, to initiate an intracellular cascade that leads to the intracellular release of Ca++, membrane depolarization, and release of ATP (141). ATP in turn activates purinergic receptors located on the afferent nerve terminals that project to the rostral portion of the NTS, where they synapse with neurons projecting to higher levels of the CNS, as well as preautonomic neurons projecting to the pancreas. Within the gut, select enteroendocrine cells employ several glucose-sensory mechanisms to detect changes in the luminal glucose concentration leading to the release of various neurotransmitters acting on local vagal afferents (175). The carotid body, the only other peripheral glucose-sensing loci known to detect hypoglycemia, also utilizes a primary sensory cell (ie, the type 1 cell, a poly-modal sensor that detects pO2, pCO2, and pH in addition to glucose concentration). In the presence of low glucose concentrations, the type 1 cell releases ATP as its primary neurotransmitter that binds with purinergic receptors located on adjacent afferents. While no such primary sensory cell has been identified for the portal-mesenteric glucose sensors, the patterns of innervation for the portal vein demonstrate similarities to the peripheral sensory loci described. That is, innervation of the portal vein appears restricted largely to the adventitia surrounding the vein, with some limited projections to the bilayer of smooth muscle below (160, 169). There are no reports of any afferents projecting into the lumen of the portal vein and thus positioned to directly detect portal glucose concentrations.

While the specific mechanism for hypoglycemic detection at the portal vein has yet to be elucidated, it is known that it is likely to involve the catabolism of glucose. Matveyenko et al (176) demonstrated that selectively elevating portal vein lactate or pyruvate levels during insulin-induced hypoglycemia led to a suppression in the sympathoadrenal response comparable to that observed when normalizing glucose across the portal vein. In contrast, portal infusion of the ketone β-hydroxybutyrate failed to impact upon the sympathoadrenal response under the same conditions. In support of the glucose selectivity of this sensor, GLUT2 knockout mice lack the ability to detect changes in portal vein glucose levels (177). Even when GLUT2 levels are restored to normal in the liver, GLUT2–/– mice fail to respond to portal glucose infusions, confirming both the glucose specificity and portal locus of the glucose sensor. Burcelin (178) further reported that an intact glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP 1) receptor was required for portal glucose sensing. The significance of this for the hypoglycemic condition where GLP-1 levels would be expected to be low remains to be clarified.

Translational Studies

The existence of portal-mesenteric glucose sensors has been confirmed in several species (ie, rat, mouse, guinea pig, and dog), but attempts to confirm their existence in people have proven elusive. As with studies of the brain, investigators are limited by ethical considerations in directly accessing the portal-mesenteric vein of people. Several investigators have attempted to circumvent this limitation by providing an oral glucose load during a hyperinsulinemic-hypoglycemic clamp. Presumably, the oral glucose load would work as a portal glucose infusion analogous to the local irrigation approach. However, this oral glucose approach has yielded inconsistent findings with reports of suppressed, elevated, and unaffected CRR (179–182). In the absence of portal vein glucose measurements, explaining these differences remains largely speculative. What is clear is that that most studies using this approach have demonstrated a sensory response to the portal glucose load (180–182). Further support for portal-mesenteric glucose sensing in people derives from the work of Perseghin et al (183), who reported that the CRR is diminished in people with denervated livers (ie, following liver transplantation). While much remains to be done, the preponderance of evidence suggests that people, like all other mammalian species studied to date, retain portal-mesenteric glucose sensors critical for hypoglycemic detection.

Future Directions: PMV Glucose Sensors

As the reader will undoubtedly have surmised, there is considerably less known about the portal-mesenteric glucose sensors when compared with those of the CNS. Further, much of what is known relates to the vagal portal glucose sensors, which do not appear to be involved in hypoglycemic detection. Among the areas for future investigation, perhaps the most obvious is the underlying mechanism for hypoglycemic detection at the portal-mesenteric vein. If it mimics other peripheral glucose sensors, what is the primary sensory cell? How is the glucose signal transduced? And what is the neurotransmitter involved? Alternatively, if these spinal afferents detect glucose directly, is the mechanism similar to those proposed for either the GE or GI neurons of the CNS? The specific spinal afferents involved remain to be phenotyped, both chemically and functionally. Tracing studies are required to ascertain the anatomical path by which glucose sensory information from the portal-mesenteric vein ascends to the hindbrain and beyond. Finally, the putative role of portal-mesenteric glucose sensing in HAAF remains to be fully elucidated.

Conclusion

In this review, the authors have presented what is known and some of what is not known about the 3 primary glucose-sensing areas that contribute to glucose counter-regulation. In doing so, the authors are confronted with the fact that present data cannot fully explain how these distinct glucose-sensing regions are activated, how they interact, or how their functions are integrated to achieve and preserve glucose homeostasis. However, a very significant conclusion one can draw from analysis of the specific CRRs discussed in this review is that there are multiple glucose sensors that operate under different physiological conditions. For example, both adrenal E and glucagon responses to glucoprivation are influenced by all 3 glucose-sensing regions discussed in this review, but it is apparent that these multiple sites of control are not equivalent. Rather, different sensors appear to be activated to varying degrees as the threat posed by hypoglycemia to the brain changes. When glucose levels decline slowly, the PMV is the dominant system, with the brain playing a modulatory role. On the other hand, as the rate of glucose decline increases, so may the relative contribution of the brain, such that, as shown by Saberi et al (12), at very rapid rates of decline, it is the brain that claims the dominant role.

During rapid hypoglycemia, the hindbrain catecholamine neurons may play a greater role than the VMN in adrenal E secretion, since ablating these neurons abolishes the adrenal E response to hypoglycemia. In contrast, most studies indicate that while manipulations of the VMH reduce or enhance adrenal E secretion by ~50% or more, it is never completely abolished. On the other hand, the VMN may be more important than the hindbrain in the regulation of glucagon secretion. For example, preventing increased GABA tone during HAAF may restore glucagon release during hypoglycemia in diabetic rats in which the glucagon response was previously considered to be irreversibly impaired even in the absence of HAAF (57).

These and other data point to a hierarchical organization of glucose-sensing sites. The potential for hierarchical recruitment of different glucose-sensing areas would be energy-conserving, as glucose reserves would be allocated judiciously as needed, rather than being wasted by premature mobilization. Evidence has been reviewed that the PMV glucose sensors are recruited during slow or modest declines in blood glucose. The fact that the sensitivity of VMN receptors to glucose deficit appears to be dependent on prior metabolic state is also consistent with a hierarchical organization. Contribution of the VMN to hypoglycemia-induced adrenal medullary secretion appears to be enhanced when overall body energy stores are low. The evidence for this is that the satiety hormones, insulin and leptin, profoundly reduce the ability of VMN GE and GI neurons, respectively, to sense decreased glucose in vitro, whereas fasting significantly enhances the response of VMN GI neurons to decreased glucose (40, 140). This hierarchical recruitment of glucose sensors could potentially enhance both glucagon and sympathoadrenal responses as hypoglycemia becomes a greater threat to the brain. This hypothesis has not been examined thoroughly. However, it would be reasonable to assume that a system with a higher threshold for activation by glucose deficit than hypothalamic or peripheral systems, perhaps with selective sensitivity to glucose availability, and with the ability to elicit a multisystem CRR, such as that provided by hindbrain catecholamine neurons, would be required to avert or respond to rapidly developing and profound glucoprivation.

Finally, HAAF may be caused by impaired glucose sensing or by impaired CRR effector mechanisms. There is strong evidence showing that VMN glucose sensors become impaired during HAAF (48, 80). Manipulations that enhance glucose-sensitive signaling pathways in the VMH are associated with enhanced sympathoadrenal and glucagon responses to hypoglycemia, both in the control situations and during HAAF (10, 74, 82, 184). Antecedent hindbrain glucoprivation also impairs adrenal E and glucagon secretion (S Ritter, 2012, unpublished data). Similarly, antecedent hypoglycemia localized to the PMV impairs the CRR to slow-onset hypoglycemia (185). Thus, impaired glucose sensing by any of these 3 key glucose-sensing systems is implicated in the development of HAAF. This strongly suggests that as the circuitry and neuronal phenotypes of VMN, hindbrain catecholamine, and PMV glucose sensors are more fully revealed, they will become important therapeutic targets for prevention of HAAF during intensive insulin therapy.

The glucose sensitivity of VMN GI neurons parallels the ability of the brain to sense and respond to hypoglycemia under a number of conditions.

Selective lesion of hindbrain NE and E neurons eliminates the feeding, adrenal medullary and corticosterone responses to systemic glucoprivation, indicating that these neurons are required for glucose CRR.

PMV glucose sensors are particularly important in detecting slow-onset hypoglycemia (ie, ≤ 1 mg/dL • min−1).

A very significant conclusion one can draw from analysis of the specific CRRs discussed in this review is that there are multiple glucose sensors that operate under different physiological conditions.

Acknowledgements