Abstract

Cyclin A1 belongs to the type-A cyclins and participates in cell cycle regulation. Since its discovery, cyclin A1 has been shown mostly in testis. It plays important roles in spermatogenesis. However, there were also reports on ovary expression of cyclin A1. Therefore, we intended to revisit the expression of cyclin A1 in mouse ovary. Our study showed that cyclin A1 was expressed at the mRNA level and the protein level in mouse ovary. Tissue staining revealed that cyclin A1 was expressed in maturating oocytes. With the recent data on the functions of cyclins in somatic and stem cells, we also discussed the possibilities of further studies of cyclin A1 in mouse oocytes and perhaps in the oogonial stem cells. Our findings not only add to the supportive evidence of cyclin A1 expression in oocytes, but also may promote more interest in exploring cyclin A1 functions in ovary.

Keywords: cyclin A1, ovary, oocyte, expression, testis.

Introduction

Cell cycles are regulated by various cyclins and their associated kinases. Type-A cyclins (Cyclin A) are involved in DNA replication, centrosome duplication, and mitosis 1, 2. There are two types of cyclin A: cyclin A1 and A2. Cyclin A2 is ubiquitously expressed in somatic and germ cells 3. Mice lacking cyclin A2 is embryonic lethal 4. However, cyclin A1 expression is mostly restricted to testis 5, 6. Mice lacking cyclin A1 are male infertile 7.

Cyclin A1 is encoded by Ccna1. The expression of the Ccna1 is mainly regulated at transcriptional level. Two upstream regions (-4.8 kb/-1.3 kb) of the Ccna1 transcription start site (TSS) were found to be responsible to stimulate the testis-specific and high expression of cyclin A1 8. Furthermore, Sp1 and GATA binding sites were recently discovered within positions -290/-120 bp upstream of the TSS 9. These sites are responsible for the repression of the cyclin A1 expression. Since cyclin A1 is found in late, but not early spermatocytes, the simulative and repressive regulations of the cyclin A1 transcription might explain the unique testis-specific expression patterns of cyclin A1 5, 10.

Though most of the studies support the testis-specific expression of cyclin A1 7, 11, 12, evidence of ovary/oocyte expression of cyclin A1 is also available 5, 13, 14. There are still controversies over the ovary/oocyte expression of cyclin A1. Particularly, Persson et al showed that in ovary cyclin A1 was not expressed to a significant level that could be detected at either the mRNA level or the protein level 12.

In this study, we showed that at both the mRNA level and the protein level cyclin A1 was detected in mouse ovary/oocyte. This study may provide some additional in vivo evidence that cyclin A1 is expressed in mouse ovary/oocyte and is not only restricted to male reproductive system.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice (12-week old) were purchased from the Experiment Animal Center of China Medical University, and were sacrificed immediately by euthanasia for tissue collections. Experiments and protocols were approved by the ethic committee, University Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol SCXK-2008-0005).

RT-PCR

RNAs were extracted from the tissues of the mice by RNAiso reagent (Takara) and were reversely transcribed to cDNAs using the AMV Reverse Transcriptase XL in RNA PCR kit (AMV) Version 3.0 (Takara) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR were performed with Ex Taq Hot-Start DNA Polymerase in the RNA PCR kit: 94 °C, 2 min; 94 °C, 30 sec, 54 °C, 30 sec, 72 °C 1 min for 35 cycles; 72 °C, 5min. The primers were: for cyclin A1 forward: 5'-CGCACAGAGACCCTGTACTT-3'; reverse: 5'-TTGGAACGGTCAGATCAAAT-3', PCR product size is about 250 bp; for actin forward: 5'-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3'; reverse 5'-TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG-3', PCR product size is about 390 bp.

Tissue Sections

Tissues from the mice were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight; then rinsed for 30 minutes in PBS three times, and sequentially bathed in 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose in PBS to cryoprotect until the tissues sank to the bottom. The tissues were embedded with OCT and subsequently stored at -80 °C until use. Cryostat sections (7-10μm) were cut and plated on gelatin-coated glass slides and dried overnight prior to immunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was done as described previously 9. Briefly, sections were blocked in PBS containing 5% donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 then incubated with the following primary antibody: rabbit anti-Cyclin A1 antibody (H-230) (Santa Cruz; 1:200 dilution). The secondary antibodies used were goat anti-rabbit Alexa 594 (Molecular Probes; 1:800 dilution).

Results

Expression of Cyclin A1 mRNA in Different Tissues

We first examined expression of cyclin A1 in various mouse tissues by RT-PCR (Fig. 1). Cyclin A1 was expressed in mouse testis, as expected. We were also able to detect cyclin A1 in mouse ovary. As a negative control, mouse greater omentum had no expression of cyclin A1. Please note that only the most relevant results were shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Expression of cyclin A1 in ovary at the mRNA level A. Illustration showing the cyclin A1 cDNA and the locations of the forward and reverse primers. B. The expression of cyclin A1 in testis, ovary, and negative control (greater omentum) was detected by RT-PCR. Actin was detected as loading controls. The sizes of the RT-PCR Cyclin A1 and Actin products are labeled as 250 bp and 390 bp, respectively.

Validation of the Cyclin A1 Antibody

To further verify the RT-PCR results in ovary, we took immunofluorescence as a more direct approach (regarding the tissue origin) to the cyclin A1 expression in known positive and negative tissues. Our antibodies were able to detect cyclin A1 in mouse testis specifically (Fig. 2A), similar to the results by RT-PCR. However, we didn't' detect cyclin A1 expression in known negative tissues (data not shown). In addition, immunofluorescence without the primary antibody (against cyclin A1) also confirmed the specificity of the staining (data not shown).

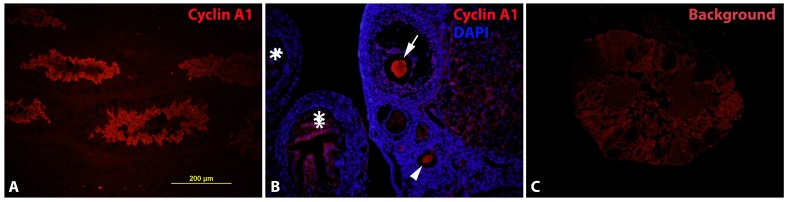

Figure 2.

Expression of cyclin A1 in maturating oocytes at the protein level A. Cyclin A1 expression in testis was examined to confirm the antibody in a cyclin A1 positive tissue. B. Cyclin A1 expression was detected in oocytes, at various maturating stages. Arrow: oocyte close to ovulation; arrow head: oocyte at an earlier maturating stage; stars: fimbriae of the fallopian tube. C. Background (or non-specific) staining of the ovary without primary cyclin A1 antibody.

Expression of Cyclin A1 Protein in Ovary

After the validation of the cyclin A1 antibody, we set up experiments to detect cyclin A1 expression in mouse ovary. The results (Fig. 2B) showed indeed that cyclin A1 was expressed in ovary. The cyclin A1 expression was not found everywhere in the ovary, but rather in developing/maturating oocytes. By a closer look at the morphologies of the follicles and the oocytes, the oocytes in Fig. 2B were at various maturating stages. The more mature oocyte in Fig. 2B was also in close proximity to the fimbriae of the fallopian tube, indicating that the oocyte was near ovulation. The expression of the cyclin A1 was so restricted that most of the other parts of the ovary didn't express it. Fig. 2C was a negative control, showing the background, but non-specific staining in mouse ovary, without the primary cyclin A1 antibody. This negative control was also to indicate the specificity of the antibody.

Discussion

We intended to revisit the topic of cyclin A1 expression in female reproductive system by assessing at the mRNA and the protein levels. Our findings concluded that cyclin A1 was expressed in oocytes. Though further studies are necessary to uncover the functional roles of such expression, at least the current study adds to the evidence that cyclin A1 is expressed in the female reproductive system. Furthermore, we also showed in vivo and confirmed the cyclin A1 expression in developing oocytes. Presumably, the maturation specific expression patterns may suggest some unique functions in these cell types.

Since the discovery of cyclin A1, there have been different opinions on its sites of expression. Most of the studies support the testis-specific expression 7, 11, 12. However, ovary expression was also found or implied 5, 13, 14. In this study, we detected cyclin A1 expression in mouse ovary at the mRNA level and the protein level. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that the cyclin A1 expression was in maturating oocytes, but not in other parts of the ovary. Compared to sperms in testis, oocytes are much fewer in quantities in ovary. This may explain the difficulties in detecting cyclin A1 expression in ovary. Another explanation may be due to the detection methods, sensitivity or specificity, which are more important in detecting low or tempo-spatial gene expressions. It is interesting and significant that cyclin A1 expression was found in maturating oocytes. Cyclin A1 is a cell cycle regulator and forms complexes with cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) and CDK2 15, 16. These complexes have been suggested playing roles in DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) repair (required in meiotic recombination) and G2-M transition in meiosis 7, 15, 16.

Mice lacking cyclin A1 can survive, but males become infertile 7. These observations indicate that cyclin A1 is not essential for survival but is unique in spermatogenesis. Female mice lacking the cyclin A1 expression was developmentally normal and reproduction was not affected, either. The expression of cyclin A1 in oocytes could also suggest its normal role in oogenesis under wild type conditions. However, it may be more challenging to confirm this, compared to cyclin A1 in spermatogenesis.

It is known that cyclins are redundant 1. The missing functions of one cyclin can be substituted by another, though not completely equivalent. For example, cyclin A1 and A2 ablated fibroblasts cells could proliferate normally but with alterations in cell cycles 17. These cells were also found to overexpress cyclin E in a wider cell cycle window. Further deletion of cyclin E shut off cell cycle completely. In this case, cyclin E and cyclin A are redundant in controlling cell cycle progression.

In the same study, it was also shown that cyclin A and cyclin E were required by hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) and embryonic stem cells (ESC), respectively 17. These two cell types are of more stem cell origin than fibroblast. Along this line, it would be interesting to know how cyclin A1 and/or A2 function in the stem cells of oocytes. Recent studies have shown that adult ovary contains stem cells that are capable of replenishing the follicle oocytes 18, 19. Further studies on how oogonia/oocytes react to alterations of cyclin A will reveal more that were not observed in previous studies. It would be also important to observe the long-term responses (such as follicle pool size), but not only cell cycle changes.

In conclusion, our finding of cyclin A1 expression in maturating oocyte may further support future studies on the role of cyclin A in female reproductive system.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30640003), General Grant (L2010617) of Education Department of Liaoning Province, and Science and Technology Design Program (2011225027) of Science and Technology Agency of Liaoning Province, China.

References

- 1.Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell. 2004;116:221–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meeran SM, Katiyar SK. Cell cycle control as a basis for cancer chemoprevention through dietary agents. Frontiers in bioscience: a journal and virtual library. 2008;13:2191–202. doi: 10.2741/2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravnik SE, Wolgemuth DJ. The developmentally restricted pattern of expression in the male germ line of a murine cyclin A, cyclin A2, suggests roles in both mitotic and meiotic cell cycles. Developmental biology. 1996;173:69–78. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0007. doi:10.1006/dbio.1996.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy M, Stinnakre MG, Senamaud-Beaufort C, Winston NJ, Sweeney C, Kubelka M. et al. Delayed early embryonic lethality following disruption of the murine cyclin A2 gene. Nature genetics. 1997;15:83–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-83. doi:10.1038/ng0197-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney C, Murphy M, Kubelka M, Ravnik SE, Hawkins CF, Wolgemuth DJ. et al. A distinct cyclin A is expressed in germ cells in the mouse. Development. 1996;122:53–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolgemuth DJ, Roberts SS. Regulating mitosis and meiosis in the male germ line: critical functions for cyclins. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 2010;365:1653–62. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0254. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D, Matzuk MM, Sung WK, Guo Q, Wang P, Wolgemuth DJ. Cyclin A1 is required for meiosis in the male mouse. Nature genetics. 1998;20:377–80. doi: 10.1038/3855. doi:10.1038/3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lele KM, Wolgemuth DJ. Distinct regions of the mouse cyclin A1 gene, Ccna1, confer male germ-cell specific expression and enhancer function. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1340–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030387. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.104.030387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panigrahi SK, Vasileva A, Wolgemuth DJ. Sp1 transcription factor and GATA1 cis-acting elements modulate testis-specific expression of mouse cyclin A1. PloS one. 2012;7:e47862.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047862. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravnik SE, Wolgemuth DJ. Regulation of meiosis during mammalian spermatogenesis: the A-type cyclins and their associated cyclin-dependent kinases are differentially expressed in the germ-cell lineage. Developmental biology. 1999;207:408–18. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9156. doi:10.1006/dbio.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang R, Morosetti R, Koeffler HP. Characterization of a Second Human Cyclin A That Is Highly Expressed in Testis and in Several Leukemic Cell Lines. Cancer Research. 1997;57:913–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persson JL, Zhang Q, Wang XY, Ravnik SE, Muhlrad S, Wolgemuth DJ. Distinct roles for the mammalian A-type cyclins during oogenesis. Reproduction. 2005;130:411–22. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00719. doi:10.1530/rep.1.00719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krug U, Yasmeen A, Beger C, Baumer N, Dugas M, Berdel WE. et al. Cyclin A1 regulates WT1 expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells. International journal of oncology. 2009;34:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchimoto D-i, Mizukoshi A, Schultz RM, Sakai S, Aoki F. Posttranscriptional Regulation of Cyclin A1 and Cyclin A2 During Mouse Oocyte Meiotic Maturation and Preimplantation Development. Biology of Reproduction. 2001;65:986–93. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.4.986. doi:10.1095/biolreprod65.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi AR, Jobanputra V, Lele KM, Wolgemuth DJ. Distinct properties of cyclin-dependent kinase complexes containing cyclin A1 and cyclin A2. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2009;378:595–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.077. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller-Tidow C, Ji P, Diederichs S, Potratz J, Baumer N, Kohler G. et al. The cyclin A1-CDK2 complex regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Molecular and cellular biology. 2004;24:8917–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8917-8928.2004. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.20.8917-8928.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalaszczynska I, Geng Y, Iino T, Mizuno S, Choi Y, Kondratiuk I. et al. Cyclin A is redundant in fibroblasts but essential in hematopoietic and embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;138:352–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.062. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–50. doi: 10.1038/nature02316. doi:10.1038/nature02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL. Oocyte formation by mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive-age women. Nature medicine. 2012;18:413–21. doi: 10.1038/nm.2669. doi:10.1038/nm.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]