Abstract

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) targeting eating behaviors have gained popularity in recent years. A literature review was conducted to determine the effectiveness of MBIs for treating obesity-related eating behaviors, such as binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating. A search protocol was conducted using the online databases Google Scholar, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Ovid Healthstar. Articles were required to meet the following criteria to be included in this review: (1) describe a MBI or the use of mindfulness exercises as part of an intervention, (2) include at least one obesity-related eating behavior as an outcome, (3) include quantitative outcomes, and (4) be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. A total of N=21 articles were included in this review. Interventions used a variety of approaches to implement mindfulness training, including combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapies, mindfulness-based stress reduction, acceptance-based therapies, mindful eating programs, and combinations of mindfulness exercises. Targeted eating behavior outcomes included binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, and dietary intake. Eighteen (86%) of the reviewed studies reported improvements in the targeted eating behaviors. Overall, the results of this first review on the topic support the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for changing obesity-related eating behaviors, specifically binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating.

Keywords: Mindfulness, obesity, eating behavior, literature review

Introduction

Obesity has become one of the most pressing health issues in the United States. According to the 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES), 33.8% of adults in the United States are obese.1 The prevalence of obesity has more than doubled over the past three decades,2 and recent evidence indicates that this trend could continue if weight control interventions do not become consistently successful.3 The gravity of this problem is underscored by the fact that obesity is linked with chronic diseases4–6 and decreased life expectancy.7 The growth of the obesity epidemic has been met with attempts to intervene at many levels; however, most interventions for weight loss do not have successful long-term outcomes.8 Obese individuals who lose weight typically regain approximately one-half of the weight within the first year after weight loss,9 and an estimated 80% of individuals who lose weight return to or exceed their initial weight within three to five years.9

Binge eating,10, 11 emotional eating,10, 12, 13 external eating,13–15 and eating in response to food cravings16, 17 have been linked to weight gain and weight regain after successful weight loss. Binge eating is characterized by consumption of large amounts of food and loss of control over eating. Although prevalence estimates for binge eating among obese individuals vary,11 evidence indicates that binge eating is a substantial issue among obese individuals. A recent study of binge eating in a community sample found that nearly 70% of individuals who engaged in binge eating were obese.18 Emotional eating is characterized by consumption of food in response to emotional arousal,19 and external eating is characterized by eating in response to external food-related cues (i.e., the sight, smell, and taste of food).20 Although there are no prevalence estimates for emotional and external eating behaviors, there is evidence that they are more common among obese individuals than normal-weight individuals.21 Food cravings have been shown to lead to obsessive thoughts about food and impulsive consumption of craved foods in some individuals, which increases the risk for weight gain.22 These eating behaviors are not typically addressed in weight loss interventions and may contribute to the lack of long-term intervention success.23, 24

Several hypotheses provide plausible explanations for how these eating behaviors are associated with weight gain. According to escape theory25 and affect regulation models,26, 27 individuals may use emotional eating or binge eating as maladaptive coping mechanisms in response to psychological distress and negative self-assessments.28 Obesity-related eating behaviors have been linked with depression, stress, and anxiety,29 lending support to this explanation. The dysregulation model of obesity proposes that poor recognition of physical hunger and satiety cues can give rise to the inability to self-regulate eating behavior.30, 31 The psychosomatic theory posits that overeating in response to emotions is caused by an inability to distinguish between emotional arousal and physical hunger.32 According to externality theory, individuals who engage in external eating overeat due to a heightened sensitivity to external food cues.33 A commonality between these theoretical models is that they suggest problematic eating behaviors are associated with maladaptive responses to internal and external cues and with dysregulation of eating behaviors. Such issues are not addressed in conventional dietary weight loss interventions, which typically focus on restriction of caloric intake and food types.23

In recent years, mindfulness has gained attention as an avenue through which problematic eating behaviors can be modified. Mindfulness is a quality of consciousness that is characterized by continually attending to one’s moment-by-moment experiences, thoughts, and emotions with an open, non-judgmental approach.34, 35 Although it is considered to be an inherent quality, mindfulness can be cultivated through systematic training that involves practicing various forms of mindfulness meditations and exercises.23 Interventions for health issues ranging from anxiety to substance use relapse have employed mindfulness practices.30, 36 Several formal mindfulness programs have been developed for clinical treatments, including Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) for pain management and stress-related disorders, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) for prevention of major depression relapse, and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) to treat borderline personality disorder.36 The skills that mindfulness practices cultivate enhance self-regulation by improving awareness of emotional and sensory cues,24, 30, 37, 38 which may be important for altering one’s relationship with food.

MBIs have recently become a focus for the treatment of obesity-related eating behaviors. Previous systematic reviews have focused on MBIs for: chronic pain,39, 40 depression,41, 42 anxiety disorders,43 stress reduction,44 cancer care,45–48 general psychological health,49 psychiatric disorders,50 speech pathologies,51 anorexia and bulimia,52 and substance use disorders.53 A recent integrative review provides a general overview on current trends in the field of mindfulness research for the treatment of obesity and eating disorders.54 It presents information from literature reviews on related topics, state of science reports, quantitative studies, and qualitative studies, but does not present a synthesized assessment of intervention studies. The current review provides a systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors, assessing the types of mindfulness practices that have been employed, the outcomes the MBIs have targeted, and their effectiveness. This review is a systematic assessment of MBI studies for obesity-related eating behaviors that aims to answer the following question: are mindfulness-based interventions effective for changing obesity-related eating behaviors?

Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A systematic search was conducted to identify studies that describe the use of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors. Literature searches were conducted for articles published up to July 3, 2013. Articles were identified from the databases Google Scholar, PubMed, PsycINFO, and Ovid Healthstar, as well as from references cited in reviewed articles. The search strategy was based on using combinations of the following keywords in the search databases: mindfulness, mindful, mindfulness meditation, eating, overeating, binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, weight-related eating behaviors, obese, weight, intervention, and program. Mindfulness interventions were defined as those that employed mindfulness exercises, including mindful eating, mindfulness meditation, mindful body scan, or acceptance-based practices. Obesity-related eating behaviors were defined as eating behaviors for which there is evidence of an association with weight gain or obesity (binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, eating in response to food cravings, and unhealthy dietary intake).55

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be considered for full review, articles were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) describe a MBI or the use of mindfulness exercises as part of an intervention, 2) include at least one obesity-related eating behavior as an outcome, 3) include quantitative outcomes, and 4) be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Articles that did not include eating behaviors associated with weight gain as outcomes were excluded. Articles that described MBIs for anorexia and bulimia were also excluded because these eating disorders are not typically related to obesity and weight gain. Additionally, articles that described single-participant case studies were not considered for review due to their limited generalizability.

Identification of Relevant Studies and Data Extraction

One author conducted article screenings from September 2012 to July 2013. Potential articles were first identified by screening the article title and then by screening the abstract. Articles that were considered relevant after title and abstract screenings were reviewed in full for final consideration of inclusion in the review. One author extracted study details from the reviewed articles. For studies that described statistically significant outcomes, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Included and Excluded Articles

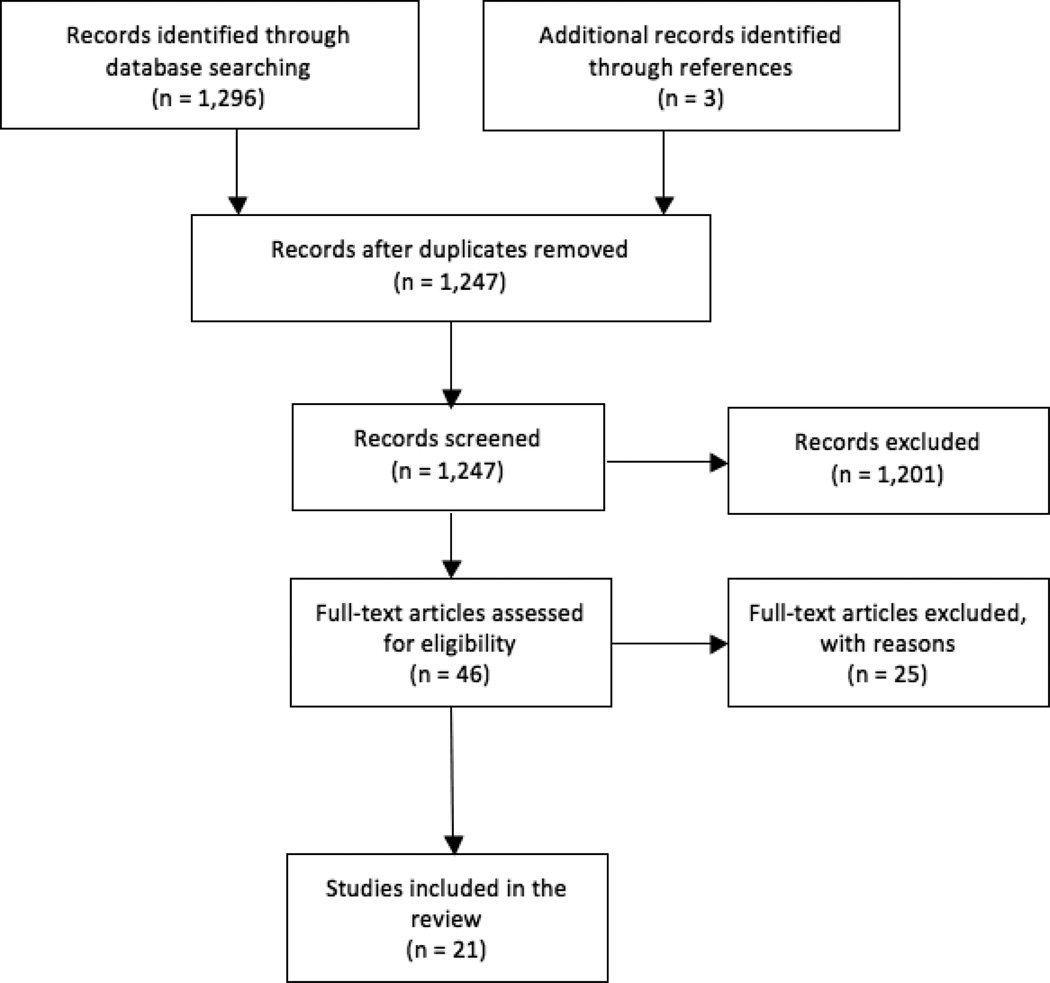

As of July 3, 2013, our search protocol yielded a total of 1,296 articles. After initial review of article titles and abstracts, 1,201 articles were considered ineligible for review because they were not relevant to the current review topic. Additionally, 52 articles were found to be duplicates. A total of 43 articles were retained from the search results for full review, and an additional 3 articles were identified for review from the reference sections of the retained articles. A total of 46 articles were reviewed in full for consideration of inclusion in this review. Of the 46 articles retained for full review, 10 articles were excluded because they were not intervention studies, 4 were excluded because they did not explicitly describe the intervention as mindfulness-based or as including mindfulness exercises, 8 were excluded because they did not include eating behaviors associated with weight gain or obesity as outcomes, 2 were excluded because they described single-participant case studies, and 1 was excluded because it was a dissertation (not published as a peer-reviewed article). A final sample of 21 articles was included in this review. Article selection is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Process of article selection

Intervention Characteristics

Study characteristics, sample characteristics, and findings are presented in Table 1. Obesity-related eating behaviors that were targeted in the interventions included emotional eating,8, 23, 37, 56–60 external eating,8, 23, 35, 37, 56, 58–62 binge eating,8, 29, 30, 37, 58, 60, 63–68 reactivity to food cravings,68, 69 restrained eating,29, 56 mindless eating,70 and unhealthy dietary intake.8, 59, 71 Several interventions (n=8) aimed to treat more than one of these eating behaviors concurrently, targeting combinations of emotional eating, external eating, and binge eating.8, 23, 29, 37, 56, 58–60 Weight-related outcomes were also measured in ten of the twenty-one studies.8, 23, 30, 37, 57–59, 67, 68, 71 Despite the fact that these interventions aimed to manipulate levels of mindfulness to change the targeted behaviors, only eleven studies measured mindfulness prior to and after the intervention.8, 23, 29, 30, 56, 60, 62, 64–66, 70

Table 1.

Study Characteristics, Sample Characteristics, and Empirical Findings

| Study | N | Sample Characteristics |

Research Design |

Theoretical Framework |

Intervention Modality/Length |

Mindfulness Components | Eating Behavior Outcome |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberts et al., 2010 | 19 |

Age: 51.9 ± 12.8 Gender: 89.5% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: 31.3 ± 4.1 |

RCT: MM (n=10) vs. control (n=9) | Not reported | Group sessions + independent work; 7 weeks | Body scan to recognize bodily hunger and satiety cues and mindfulness meditations to increase awareness of eating behavior and cravings-related thoughts. | Loss of control of eating | Intervention group reduced loss of control of eating (p=0.017, d=3.02). Intervention and control groups reduced weight (p<0.01, d=0.12; p=0.04, d=0.12). |

| Alberts et al, 2012 | 26 |

Age: Not reported Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: 32.7 ± 6.1 |

RCT: MBCT modified for eating behavior (n=12) vs. waitlist control (n=14) | Not reported | Group sessions; 8 weeks | Bodyscan, sitting and walking meditation, mindful eating skills, acceptance of oneself and one's body, and dealing with the paradox of control. | External eating, emotional eating, restrained eating | Intervention group decreased emotional eating (p=0.03, d=0.53) and external eating (p=0.03, d=0.6) |

| Baer et al., 2005 | 10 |

Age: 23–65 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: 22–40 |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MBCT | Application of Expectancy Theory and Emotion Regulation Model to problematic eating behaviors | Group sessions; 10 weeks | Body scan, mindful stretching, mindful eating, and sitting meditation. | Binge eating, eating restraint | Decreased binge eating (es =0.88) and eating restraint (es=0.42) |

| Cavanagh et al., 2013 | 96 |

Age: 19.7 ± 4.7 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: Not Reported BMI: 21.5 ± 3.1 |

RCT: Mindfulness vs. education and control | Not reported | Group sessions; 1 session | Mindful awareness of sensory experiences during eating and mindful meditation. | Excess energy intake in response to portion size (external eating) | Mindfulness condition participants ate less than participants in other conditions but trend not significant |

| Courbasson et al., 2011 | 38 |

Age: 42 ± 11 Gender: 79% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: Not reported |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MABCT | Not reported | Group sessions; 16 weeks | Developing mindfulness to adopt a non-judgmental and non-striving stance, learning emotion regulation skills, and mindful eating to prevent consuming more food than intended and eating when not physically hungry. | Binge eating | Decreased binge eating frequency (p=0.02, d=0.86) |

| Dalen et al., 2010 | 10 |

Age: 44 ± 8.7 Gender: 70% Female Ethnicity: 60% White, 20% Hispanic/Latino, 20% Native American BMI: 36.9 ± 6.2 |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MEAL | Not reported | Group sessions; 6 weeks | Walking meditations, sitting meditations, mindful eating, and yoga. | Binge eating | Decreased weight (mean weight loss p<0.01) and binge eating (p=.003, d=1.3 at 6 weeks; p=.001, d=2.2 at 12 weeks) |

| Daubenmier et al., 2011 | 47 |

Age: 40.4 ± 8 Gender: 100% F Ethnicity: 62% White, 15% Hispanic/Latino, 15% Asian/Pacific Islander, 9% Other BMI: 31.2 (SD not reported) |

RCT: MBSR + MBCT + MB-EAT (n=24) vs waitlist control (n=23) | Not reported | Group sessions; 4 months | Body scan, mindful yoga stretches, sitting and loving kindness meditations, mindful eating, and 3-minute breathing exercises. | Emotional eating, external eating | Intervention group decreased external eating (p=0.02, d=-0.7) and emotional eating (marginal p=.08, d=-0.57). Intervention stabilized weight among those who were obese, while the control group gained a mean 1.7 kg during same time period (p=0.08). |

| Jacobs et al., 2013 | 26 |

Age: 21.4 ± 4.8 Gender: 77% Female Ethnicity: 73% White, 12% Hispanic/Latino, 8% African American, 4% Asian, 4% Biracial BMI: 19.8 ± 2.3 |

Pretest-posttest, no control pilot study | Not reported | Group sessions; 1 session | Mindful breathing, sitting meditation, and mindful eating meditation. | Overconsumption of food during a standardized meal (external eating) | 86% of participants engaged in consumption of healthy amount of food during standardized meal. 14% of participants engaged in overconsumption during meal. |

| Jenkins et al., 2013 | 137 |

Age: 20.5 ± 2.4 Gender: 71.5% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: Not reported |

Pretest-posttest: cognitive defusion (n=45) vs. acceptance (n=45) vs. control (n=45) | Not reported | Independent work; 5 days | Cognitive defusion and acceptance | Reactivity to food cravings | Less consumption of study-provided chocolate (p=0.046) and other chocolate products (p=0.053) among cognitive defusion group compared to control group |

| Kearney et al., 2012 | 48 |

Age: 49 ± 10.7 Gender: 87.5% Male Ethnicity: 85.4% White, 4.2% African American, 6.3% Hispanic/Latino, 4.2% Asian BMI: Not reported |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MBSR | Theoretical model of mindfulness by Shapiro et al, 2006, for mindfulness mechanisms of action | Group sessions; 8 weeks | Body scan, sitting meditation, gentle yoga, walking meditation, and loving-kindness meditation. | Emotional eating, uncontrolled eating, dietary intake | No changes in emotional eating or uncontrolled eating. No changes in dietary intake. Increased body weight (p<0.05, d=0.07 at 4 month follow-up) and BMI (p<0.05, d=0.06 at 4 month follow-up) |

| Kidd et al., 2013 | 12 |

Age: 51.8 ± 9.1 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: 41.7% White, 58.3% African American BMI: 44.7 ± 6.9 |

Pretest-posttest, no control | Self-regulation theory | Group sessions; 8 weeks | Mindful awareness, observation, shifting out of automatic behaviors, mindful environment and being in the moment, non judgment, letting go, practicing acceptance. | Mindless eating | No changes in mindful eating after intervention. |

| Kristeller & Hallet, 1999 | 18 |

Age: 46.5 ± 10.5 Gender:100% Female Ethnicity: 90% White BMI: 40.3 (SD not reported) |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MM | Not reported | Group sessions; 6 weeks | General mindfulness meditations, mini meditations, and mindful eating. | Binge eating, hunger and satiety awareness | Decreased binge eating frequency (p<0.001). Increased hunger awareness (p<0.001) and satiety awareness (p<0.001). Increased awareness of satiety cues related to reduction in binges (r=0.53, p<0.025). |

| Kristeller et al., 2013 | 150 |

Age: 46.6 (SD note reported) Gender: 88% Female Ethnicity: 14% African American or Hispanic BMI: 40.3 (SD not reported) |

RCT: MB-EAT (n= 53) vs. PECB (n= 50) vs. waitlist control (n=47) | Not reported | Group sessions; 12 weeks | General (breath/open awareness) mindfulness meditation, guided eating meditations, and mini-meditations | Binge eating | 95% of MB-EAT, 76% of PECB. 48% of control participants no longer had BED at 4 month follow-up. Size of binges for those who reported still binging at follow-up were smallest for MB-EAT condition (60% binges by MB-EAT = small, 59% binges by PECB = medium, 85% binges by control = medium or large. In MB-EAT condition, more meditation associated with better binge eating outcomes and greater weight loss (r=−0.33, p<0.05). |

| Leahey et al., 2008 | 7 |

Age: 49–64 Gender: 85.7% Female Ethnicity: 85.7% White BMI: 35.0–52.4 |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MBCT | Not reported | Group sessions; 10 weeks | Not engaging in any other activities while eating (to facilitate ability to attend to sight, smell, texture, and taste of food) and cueing into bodily sensations while eating. | Binge eating, emotional eating | Reduced binge eating (d=1.47, significance not reported), emotional eating (d=0.90, significance not reported), Deviations in expected weight loss after bariatric surgery improved (significance not reported). |

| Miller et al., 2012 | 52 |

Age: MB-EAT 53.9 ± 8.2, DSME 54.0 ± 7.0 Gender: MB-EAT 63% Female, DSME 64% Female Ethnicity: MB-EAT 81.5% White, 18.5% African American, DSME 72% White, 24% African American, 4% Asian BMI: Not reported |

RCT: MB-EAT (n=27) vs. DSME (n=25) | Not reported | Group sessions; 3 months | Mindful meditation, mindful eating, body awareness. | Dietary intake | Reduced energy intake, glycemic index, and glycemic load in both groups from baseline to study end and baseline to 3 month follow-up (all p <0.05). Decreased weight and BMI from baseline to post-intervention and from baseline to study end in both groups (all p=0.01). |

| Niemeier et al., 2012 | 21 |

Age: 52.2 ± 7.6 Gender: 90% Female Ethnicity: 90% White, 4.8% Hispanic, 4.8% Other BMI: 32.8 ± 3.4 |

Pretest-posttest, no control: Acceptance-based behavioral program | Not reported | Group sessions; 24 weeks | Being mindful of thoughts and feelings without trying to change them, cognitive defusion, acceptance. | Internal disinhibition (emotional eating) | Decreased internal disinhibition (F(2, 26.5)=21.3, p<.0001) over time. Average weight loss of 12.0 kg (SE = 1.4) after 6 months and 12.1 kg (SE=1.9) at 3 month follow-up. Decreased weight over time (F(2, 25.1)=37.7, p<0.0001) Decreased BMI over time (F(2, 34.1)=40.0, p<.0001) |

| Smith et al., 2006 | 25 |

Age: 47.8 ± 13.1 Gender: 80% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: 27.9 ± 7.4 |

Pretest-posttest, no control: MBSR modified for eating behaviors | Not reported | Group sessions; 8 weeks | Breathing exercises, body scans, meditation, mindful eating, and gentle Hatha yoga. | Binge eating | Decreased binge eating (d=0.36, p<0.01) |

| Smith et al., 2008 | 50 |

Age: 44.9 ± 13.7 Gender: 80% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: Not reported |

Pretest-posttest, no control with 2 groups: MBSR (n= 36) vs. CBSR (n= 14) | Not reported | Group sessions; 8 weeks | Meditation, gentle yoga, body scanning exercises, and mindful eating. | Binge eating | MBSR group decreased binge eating (p<0.0001, d=0.43). CBSR group did not decrease binge eating. |

| Tapper et al., 2009 | 62 |

Age: 41 ± 13 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: 31.6 ± 6.06 |

RCT: ACT (n=31) vs. no treatment control (n=31) | Not reported | Group sessions; 4 months | Cognitive diffusion, acceptance/willingness, and self-awareness/mindfulness. | Emotional eating, external eating, binge eating | Intervention group decreased binge eating (p<.05) at follow-up. No significant differences in BMI,, emotional eating, or external eating between conditions at 6 month follow-up. When intervention participants who reported never applying workshop principles were excluded from analyses, intervention group had greater reductions in BMI than control group (p=0.031, es=0.20). |

| Timmerman & Brown, 2012 | 35 |

Age: 49.6 ± 6.8 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: 54% White, 29% Hispanic/Latino, 17% African American BMI: 31.8 ± 6.8 |

RCT: Mindful Eating (n=19) vs. waitlist control (n=16) | Health Promotion Model by Pender et al., 2006, guiding theory for behavior change | Group sessions; 6 weeks | Mindful eating that focuses on awareness of the sight, smell, and texture of the eating experience and a series of guided mindfulness meditations that focus on awareness on hunger, satiety, and eating triggers. | Emotional eating, daily caloric/fat intake, caloric/fat intake consumed at restaurants | Intervention group had lower daily caloric intake (p=0.002), and lower daily fat intake (p=0.001) than control group. Intervention group had no significant decrease in caloric or fat intake per restaurant eating episode or in emotional eating at follow-up. Intervention group had significantly less weight gain at follow-up than control group (p=0.03). |

| Woolhouse et al., 2012 | 30 |

Age: 32.2 ± 7.9 Gender: 100% Female Ethnicity: Not reported BMI: Not reported |

Pretest-posttest, no control group: Mindful Eating + CBT | Not reported | Group sessions; 10 weeks | Mindful eating, formal sitting meditation, informal mindfulness practices, body scan, loving-kindness mediation, walking meditation, and lake meditation. | Binge eating, emotional eating, external eating | Reduced binge eating (p<0.0001, pes=0.62), emotional eating (p<0.0001, pes=0.42) and external eating (p<0.0001, pes=0.38). |

ACT: Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; BED: Binge eating disorder; CBSR: Cognitive-Based Stress Therapy; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; Es: effect size calculated in standard deviation units; DSME: Diabetes Self Management Education; MABCT: Mindfulness-Action Based Cognitive Therapy; MBCT: Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy; MB-EAT: Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training; MEAL: Mindful Eating and Living; MM: Mindfulness Meditation; MBSR: Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; PECB: Psycho-educational/Cognitive-behavioral intervention; Pes: effect sizes reported using partial eta square; RCT: randomized clinical trial

Intervention designs included randomized controlled trial (38%)23, 56, 58, 61, 67, 68, 71, 72 and pretest-posttest designs (62%).8, 29, 30, 37, 57, 60, 62–66, 69, 70 Twelve studies (57%) included overweight and obese participants. The interventions used a variety of multimodal approaches to implement mindfulness training. These included combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapies,29, 37, 56, 60, 63 mindfulness-based stress reduction,8, 35, 45, 66 acceptance-based therapies,57, 58, 69 mindful eating programs,30, 35, 59, 67, 71 and combinations of mindfulness exercises.35, 61, 62, 64, 68, 70 Many of the interventions that were designed for binge eating combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy-based exercises.29, 37, 60, 63, 65 Binge eating interventions may have been designed to include cognitive behavioral therapy exercises because binge-eating treatments have traditionally been based on cognitive behavioral therapy.73

Intervention Effects

Overall, eighteen of the twenty-one studies (86%) reported positive change in eating behavior outcomes.23, 29, 30, 37, 56, 57, 59, 60, 62–69, 71, 74 Of the twelve studies that targeted binge eating, eleven reported improvements in binge eating frequency and/or severity.29, 30, 37, 58, 60, 63–68 Reported effect sizes for binge eating ranged from small (Cohen’s d=0.36)66 to large (Cohen’s d=3.02),68 with the majority of effects being large in size. Improvements in binge eating behaviors were seen in studies that employed combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapies,29, 37, 60, 63 mindful eating programs,30, 67 acceptance-based practices,58 and combinations of mindfulness exercises.64, 68 The only intervention that did not result in improved binge eating employed a general mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program that focused exclusively on stress reduction and did not include content related to eating behaviors.

Emotional eating improved across the majority of studies that targeted this eating behavior. Of the eight studies that included emotional eating as an outcome,8, 23, 37, 56–60 five reported improvements in this eating behavior.23, 37, 56, 57, 60 Reported effect sizes for emotional eating were moderate (Cohen’s d=0.53)56 to large (Cohen’s d=0.90).37 The interventions that resulted in positive emotional eating outcomes used combined cognitive and mindfulness therapies,37, 56, 60 mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT),23 and acceptance-based practices.57 Those that did not result in changes to emotional eating used MBSR (not modified to include mindful eating training),8 mindful eating practices,59 and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).58

External eating improved across the majority of studies that aimed to improve this eating behavior. Of the six studies that included external eating as an outcome,23, 56, 58, 60–62 four reported improvements in external eating.23, 56, 60, 62 Reported effect sizes for external eating ranged from moderate (Cohen’s d=0.53)56 to large (Cohen’s d=0.70).23 Similar to binge eating and emotional eating, the interventions that used combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy approaches resulted in improved external eating.56, 60 Two23, 62 of the three interventions that used combinations of mindfulness exercises23, 61, 62 reported improvements in external eating. The studies that did not result in improved external eating included an intervention that employed acceptance and commitment therapy58 and an intervention that employed a combination of mindfulness exercises.61 Of note is the fact that one of the interventions that did not result in external eating changes included only one intervention session,61 while the successful interventions included several sessions over periods of several weeks. The other intervention that was not successful in changing external eating did not include mindful eating training,58 while the successful interventions all included mindful eating components.

It is difficult to make any conclusions about the impact of MBIs on dietary intake because only three studies aimed to improve the diet of participants,8, 59, 71 and all three studies targeted different aspects of dietary intake. Of these, two resulted in positive dietary intake changes.59, 71 Both of these studies employed mindful eating programs, whereas the study that did not result in changes to diet employed a MBSR program that was not adapted to include a mindful eating component.8

Mindfulness improved across the majority of studies that measured mindfulness before and after the intervention. Of the eleven studies that measured mindfulness,8, 23, 29, 30, 56, 60, 62, 64–66, 70 ten reported improvements in mindfulness measures.8, 23, 29, 30, 56, 60, 62, 64–66 Reported effect sizes for change in mindfulness ranged from small (η2p = 0.01)62 to large (Cohen’s d = 0.80).30 Mindfulness measures used in the studies that reported improved mindfulness included the Toronto Mindfulness Scale,62 the Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale,62 the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire,8, 62 the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills,23, 29, 30 the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills Extended,56 the Mindful Awareness Attention Scale,65, 66 and the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale – Revised.60 The study that reported no improvements in mindfulness employed the Mindful Eating Questionnaire.70

Several of the interventions had positive impacts on body weight outcomes. Of the ten studies that included body weight outcomes,8, 23, 30, 37, 57–59, 67, 68, 71 nine reported positive changes in body weight (i.e., weight loss or stabilized weight) among intervention participants.23, 30, 37, 57–59, 67, 68, 71 The average reported weight loss was 4.5 kg. Reported effect sizes for changes in body weight outcomes were small (Cohen’s d=0.1268 to 0.2623). Studies reporting positive body weight results used a variety of mindfulness practices including combinations of mindfulness exercises,67, 68 acceptance-based practices,57, 58 mindful eating exercises,30, 59 and programs such as MBCT,23, 37 MBSR,23 and MB-EAT,23, 71 thus, not allowing us to make any firm conclusions about the comparative efficacy across MBIs on weight loss. No studies included follow-up periods for greater than 24 weeks, so longer-term maintenance of effects garnered from MBIs remain untested.

Discussion

This is the first review we know of that examines the use of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors. Findings synthesized by this review provide support for the use of MBIs to treat some obesity-related eating behaviors, including binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating, and to promote weight maintenance and weight loss.

Eleven out of the twelve studies that targeted binge eating (92%) reported improvements in binge eating frequency and/or severity, and the majority of reported effect sizes were large (average Cohen’s d=1.39). The importance of mitigating binge eating for the prevention and treatment of obesity is highlighted by the fact that binge eating is the most commonly reported problematic eating behavior among obese individuals.75 Research shows that those who binge eat have poor responses to obesity interventions and tend to have rapid weight regain after successful weight loss.75 The underlying cause of binge eating is explained by escape theory25 and affect regulation models,26, 27 which posit that binge eating is a maladaptive coping mechanism for psychological distress. Mindfulness training focuses on cultivating the skills necessary to be aware of and accept thoughts and emotions and to distinguish between emotional arousal and physical hunger cues. These skills target one’s ability to cope with psychological distress in adaptive ways, ultimately leading to decreased binge eating.76 The results of this review support this, as they provide strong evidence for the efficacy of MBIs for the treatment of binge eating frequency and severity.

Five out of the eight interventions that targeted emotional eating (63%) resulted in positive changes in emotional eating occurrence and/or the urge to emotionally overeat, and reported effects from the successful interventions were moderate to large in size (average Cohen’s d=0.67). The involvement of emotional eating in weight gain is substantiated by the fact that it is linked with poor diet, including greater intake of energy-dense foods such as sweet and high-fat snacks77 and lower fruit and vegetable consumption.78 There is also strong evidence that obese individuals engage in more emotional eating than non-obese individuals.79 Emotional eating is hypothesized to arise from a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy that involves indulging in immediate impulses to eat in order to suppress negative feelings.80–82 Mindfulness training affords the skills to attend to negative feelings and accept them instead of acting on the impulse to immediately suppress them by eating, ultimately leading to decreased urges to emotionally overeat. The findings synthesized by this review reflect this and provide moderate support for the use of MBIs to improve emotional eating urges and occurrence.

Four out of the six studies that targeted external eating (67%) reported improvements in external eating frequency, and the reported effects from successful interventions were moderate to large in size (average Cohen’s d=0.65). The importance of mitigating external eating for obesity treatment and prevention is highlighted by the fact that external eating is linked with poor dietary intake and overeating.20, 83, 84 Externality theory posits that individuals who engage in external eating overeat due to a heightened attentional bias to external food cues.33 Mindfulness training can mitigate external eating by teaching skills that help one to acknowledge but not act upon impulses, such as impulses to eat in reaction to the sight and smell of food. Despite the small number of reviewed studies that targeted external eating and reported improvements, this review found moderate support for the use of MBIs to improve external eating.

Nine out of the ten studies that included body weight outcomes (90%) reported weight loss or weight maintenance. Although the reported effects on body weight from successful interventions were small in size (average Cohen’s d=0.19), the findings from this review indicate that mindfulness training provides a promising approach for weight loss and weight maintenance. Mindfulness training provides individuals with skills that allow them to mitigate maladaptive eating behaviors, helping them to develop positive relationships with food. More adaptive eating styles ultimately support weight loss and weight maintenance. The findings from this review reflect this and provide moderate support for the use of MBIs for weight loss and weight maintenance in individuals who engage in obesity-related eating behaviors.

This review found a lack of support for the ability of MBIs to affect positive change in dietary intake. This is due to the fact that few of the reviewed studies aimed to change dietary intake, and the dietary outcomes varied across the studies that did aim to change diet. Two of the three studies that targeted dietary intake reported improvements in unhealthy dietary intake after the MBIs, so the potential for mindfulness training to improve dietary patterns should not be discounted. Future research should aim to further study the impact of MBIs on dietary intake in order to determine if cultivation of mindfulness skills can reliably influence dietary intake and which dietary outcomes are most modifiable by MBIs.

Similar to reviews on MBIs for other health outcomes, this review found a range of effect sizes of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors and weight outcomes. A review on the use of MBIs for the treatment of depression and the prevention of depression relapse found that effect sizes ranged from small to large.42 Similarly, a review of MBIs for substance use treatment found small to large effect sizes for substance use and relapse-related outcomes.53 One review that assessed MBIs for anorexia and bulimia did not report effect sizes but concluded that findings from the review provided evidence to support the use of MBIs for clinical eating disorders.52 Results from these reviews indicate a similar range of effectiveness of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors and weight outcomes as for a variety of other health outcomes.

Overall, this review found positive results for obesity-related eating behavior outcomes with a variety of mindfulness training implementations, including combinations of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral practices, mindful eating programs, acceptance-based programs, and programs that used combinations of mindfulness exercises. The fact that many different types of mindfulness exercises were used in the reviewed studies for a number of different outcomes indicates that the cultivation of mindfulness skills by various mindfulness-based approaches can improve obesity-related eating behaviors. This suggests that mindfulness training can be accessible in many forms and tailored to the specific needs of obese individuals who could benefit from MBIs. Providing individuals with the skills to change their eating behaviors, develop more adaptive responses to emotional distress, and improve their relationships with food through the cultivation of mindfulness skills poses a promising approach for obesity prevention and treatment.

Limitations

Despite the rigorous search criteria and study reviews conducted, there are limitations to this review that should be acknowledged. This review only included studies that were published in English in peer-reviewed journals. Thus, some relevant literature in other languages may have been excluded. As the literature on MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors is relatively small, the conclusions made in this review are preliminary. More research is needed before definitive conclusions can be derived about their efficacy.

There are also limitations to many of the studies included in this review. Many of the studies did not report comprehensive sample characteristics such as participant ethnicity.29, 56, 58, 60, 61, 63, 65, 66, 68, 69 Samples were predominantly homogenous. Nineteen of the twenty-one studies (90%) included samples that were comprised of either all female or mostly female participants.23, 29, 30, 37, 56–71 Additionally, of the eleven studies that reported participant ethnicities, ten had samples that were comprised of mostly white participants.8, 23, 30, 37, 57, 59, 62, 64, 67, 71 The fact that most of the samples were predominantly or all female may be explained by two reasons. First, the studies that included only female participants used the justification that the eating behaviors that were targeted have a higher prevalence among women than men. However, evidence shows that obesity-related eating behaviors such as binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, and poor dietary intake are prevalent among men as well as women.85 Second, women may be more likely to admit to and seek treatment for problematic eating behaviors than men.86 These limitations may compromise the generalizability of the findings from these studies to males and more diverse ethnic groups.

Few studies proposed a theoretical basis. Seventeen (81%) of the studies did not cite a theoretical framework. Among the four studies that did cite a theoretical framework,8, 29, 59, 70 one study cited theoretical frameworks for mindfulness,8 and two studies applied theories to explain the origins of problematic eating behavior (Expectancy Theory and Emotion Regulation Model29 and self-regulation theory70). Only one study cited a theoretical model of behavior change that was used to guide the intervention design, the Health Promotion Model.59, 87 No other behavioral theories to guide intervention design were described. Half of the studies did not measure changes in mindfulness, despite the fact that several measures have been created and validated for assessment of mindfulness, including the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills,88 the Mindful Awareness and Attention Scale,34 and the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire.89 These limitations make it difficult to determine whether improved mindfulness was a mechanism functioning on the observed outcomes in some of the studies.

Future Directions

This review finds that MBIs are promising for the treatment of eating behaviors related to weight gain and obesity. However, this nascent field requires future research to fill several gaps. Future studies should implement these interventions in different populations than those that have been featured in the literature, which have been predominantly white female adults. Obesity-related eating behaviors are prevalent among men as well as women, but men often do not receive treatment.86 Not only would applying these interventions to male populations be informative for clarifying their overall efficacy, it would help determine whether MBIs are an appropriate and effective approach for men. Future studies should include samples with greater ethnic diversity to establish the generalizability of these interventions across different populations, and implement MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Assessing longer-term effects of MBIs with follow-up periods of six months or greater would help clarify maintenance effects of treatment. Future studies should also routinely measure changes in mindfulness to determine whether improved mindfulness is the mechanism for improved eating behavior outcomes. Studies comparing MBIs to other treatments can illuminate the comparative efficacy of mindfulness training to other approaches for treatment of obesity-related eating behaviors.

Conclusions

MBIs are used to treat a variety of health-related issues, and have recently gained popularity for obesity-related eating behaviors. There is much to be examined in this field of research, but preliminary findings indicated in this review are promising. The outcomes from the reviewed studies provide evidence to support the use of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors, including binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating. Given the extent of the obesity epidemic, novel approaches to support weight loss are needed. MBIs are poised to complement obesity prevention and treatment efforts. This review concludes that MBIs have growing empirical support as a promising psychoeducational and behavior-based treatment for obesity-related eating behaviors.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32CA009492.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2007–2008. NCHS Health and Stats. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: systematic review. International journal of obesity. 2010;35(7):891–898. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyatt SB, Winters KP, Dubbert PM. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331(4):166–174. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):24–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearney DJ, Milton ML, Malte CA, McDermott KA, Martinez M, Simpson TL. Participation in mindfulness-based stress reduction is not associated with reductions in emotional eating or uncontrolled eating. Nutrition Research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. International journal of obesity. 2003;27(8):955–962. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Kirschenbaum DS. Obese people who seek treatment have different characteristics than those who do not seek treatment. Health Psychology. 1993;12(5):342. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. Two forms of disordered eating in obesity: binge eating and night eating. International journal of obesity. 2003;27(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenders PG, van Strien T. Emotional Eating, Rather Than Lifestyle Behavior, Drives Weight Gain in a Prospective Study in 1562 Employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2011;53(11):1287. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31823078a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11):887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton P, Smit HJ, Lightowler HJ. The influence of restrained and external eating patterns on overeating. Appetite. 2007;49(1):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou R, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Moss-Morris R, Peveler R, Roefs A. External eating, impulsivity and attentional bias to food cues. Appetite-Kidlington. 2011;56(2):424. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delahanty LM, Meigs JB, Hayden D, Williamson DA, Nathan DM. Psychological and behavioral correlates of baseline BMI in the diabetes prevention program (DPP) Diabetes Care. 2002;25(11):1992–1998. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodin J, Mancuso J, Granger J, Nelbach E. Food cravings in relation to body mass index, restraint and estradiol levels: a repeated measures study in healthy women. Appetite. 1991;17(3):177–185. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(91)90020-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grucza RA, Przybeck TR, Cloninger CR. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Strien T, Ouwens MA. Effects of distress, alexithymia and impulsivity on eating. Eat Behav. 2007;8(2):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Strien T, Herman CP, Verheijden MW. Eating style, overeating, and overweight in a representative Dutch sample. Does external eating play a role? Appetite. 2009;52(2):380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel KA, Schlundt DG. Impact of moods and social context on eating behavior. Appetite. 2001;36(2):111–118. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.May J, Andrade J, Batey H, Berry LM, Kavanagh DJ. Less food for thought. Impact of attentional instructions on intrusive thoughts about snack foods. Appetite. 2010;55(2):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daubenmier J, Kristeller J, Hecht FM, et al. Mindfulness Intervention for Stress Eating to Reduce Cortisol and Abdominal Fat among Overweight and Obese Women: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Study. J Obes. 2011;2011:651936. doi: 10.1155/2011/651936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011;19(1):49–61. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological bulletin. 1991;110(1):86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wedig MM, Nock MK. The functional assessment of maladaptive behaviors: a preliminary evaluation of binge eating and purging among women. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(3):518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spoor STP, Bekker MHJ, Van Strien T, van Heck GL. Relations between negative affect, coping, and emotional eating. Appetite. 2007;48(3):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness and acceptance in the treatment of disordered eating. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2005;23(4):281–300. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dalen J, Smith BW, Shelley BM, Sloan AL, Leahigh L, Begay D. Pilot study: Mindful Eating and Living (MEAL): weight, eating behavior, and psychological outcomes associated with a mindfulness-based intervention for people with obesity. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(6):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Craighead LW, Allen HN. Appetite awareness training: A cognitive behavioral intervention for binge eating. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1996;2(2):249–270. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruch H. Psychological Aspects of Overeating and Obesity. Psychosomatics. 1964;5:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(64)72385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schachter S, Rodin J. Obese humans and rats. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2003;84(4):822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daubenmier J, Lin J, Blackburn E, et al. Changes in stress, eating, and metabolic factors are related to changes in telomerase activity in a randomized mindfulness intervention pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(7):917–928. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical psychology: Science and practice. 2003;10(2):125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leahey TM, Crowther JH, Irwin SR. A cognitive-behavioral mindfulness group therapy intervention for the treatment of binge eating in bariatric surgery patients. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2008;15(4):364–375. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of clinical psychology. 2005;62(3):373–386. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review of the evidence. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(1):83–93. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeidan F, Grant JA, Brown CA, McHaffie JG, Coghill RC. Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain. Neurosci Lett. 2012;520(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(6):1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klainin-Yobas P, Cho MA, Creedy D. Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on depressive symptoms among people with mental disorders: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treanor M. The potential impact of mindfulness on exposure and extinction learning in anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(4):617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):593–600. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith JE, Richardson J, Hoffman C, Pilkington K. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction as supportive therapy in cancer care: systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(3):315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Musial F, Bussing A, Heusser P, Choi KE, Ostermann T. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for integrative cancer care: a summary of evidence. Forsch Komplementmed. 2011;18(4):192–202. doi: 10.1159/000330714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shennan C, Payne S, Fenlon D. What is the evidence for the use of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer care? A review. Psychooncology. 2011;20(7):681–697. doi: 10.1002/pon.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ott MJ, Norris RL, Bauer-Wu SM. Mindfulness meditation for oncology patients: a discussion and critical review. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5(2):98–108. doi: 10.1177/1534735406288083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofmann SG, Grossman P, Hinton DE. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(7):1126–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(3):441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boyle MP. Mindfulness training in stuttering therapy: a tutorial for speech-language pathologists. J Fluency Disord. 2011;36(2):122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jfludis.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanden-Berghe RG, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. The application of mindfulness to eating disorders treatment: a systematic review. Eat Disord. 2011;19(1):34–48. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, Kushner K, Koehler R, Marlatt A. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):266–294. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Godsey J. The role of mindfulness based interventions in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders: An integrative review. Complementary therapies in medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bunnell DW, Shenker IR, Nussbaum MP, Jacobson MS, Cooper P. Subclinical versus formal eating disorders: differentiating psychological features. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;9(3):357–362. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alberts HJ, Thewissen R, Raes L. Dealing with problematic eating behaviour. The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on eating behaviour, food cravings, dichotomous thinking and body image concern. Appetite. 2012;58(3):847–851. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niemeier HM, Leahey T, Palm Reed K, Brown RA, Wing RR. An acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss: a pilot study. Behavior therapy. 2012;43(2):427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tapper K, Shaw C, Ilsley J, Hill AJ, Bond FW, Moore L. Exploratory randomised controlled trial of a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention for women. Appetite. 2009;52(2):396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Timmerman GM, Brown A. The effect of a mindful restaurant eating intervention on weight management in women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(1):22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.03.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woolhouse H, Knowles A, Crafti N. Adding mindfulness to CBT programs for binge eating: a mixed-methods evaluation. Eat Disord. 2012;20(4):321–339. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.691791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cavanagh K, Vartanian LR, Herman CP, Polivy J. The Effect of Portion Size on Food Intake is Robust to Brief Education and Mindfulness Exercises. J Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1359105313478645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobs J, Cardaciotto L, Block-Lerner J, McMahon C. A pilot study of a single-session training to promote mindful eating. Adv Mind Body Med. 2013;27(2):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Courbasson CM, Nishikawa Y, Shapira LB. Mindfulness-action based cognitive behavioral therapy for concurrent binge eating disorder and substance use disorders. Eating Disorders. 2010;19(1):17–33. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kristeller JL, Hallett CB. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4(3):357–363. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith BW, Shelley BM, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Bernard J. A pilot study comparing the effects of mindfulness-based and cognitive-behavioral stress reduction. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(3):251–258. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith BW, Shelley BM, Leahigh L, Vanleit B. A preliminary study of the effects of a modified mindfulness intervention on binge eating. Complementary Health Practice Review. 2006;11(3):133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kristeller J, Wolever RQ, Sheets V. Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) for Binge Eating: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Mindfulness. 2013:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alberts HJEM, Mulkens S, Smeets M, Thewissen R. Coping with food cravings. Investigating the potential of a mindfulness-based intervention. Appetite. 2010;55(1):160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jenkins KT, Tapper K. Resisting chocolate temptation using a brief mindfulness strategy. Br J Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kidd LI, Graor CH, Murrock CJ. A Mindful Eating Group Intervention for Obese Women: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller CK, Kristeller JL, Headings A, Nagaraja H, Miser WF. Comparative effectiveness of a mindful eating intervention to a diabetes self-management intervention among adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(11):1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Timmerman GM, Acton GJ. The relationship between basic need satisfaction and emotional eating. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2001;22(7):691–701. doi: 10.1080/016128401750434482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(8):713. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lillis J, Hayes SC, Bunting K, Masuda A. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: a preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(1):58–69. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. Preventing excessive weight gain in adolescents: interpersonal psychotherapy for binge eating. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(6):1345–1355. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sojcher R, Gould Fogerite S, Perlman A. Evidence and potential mechanisms for mindfulness practices and energy psychology for obesity and binge-eating disorder. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing. 2012;8(5):271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Macht M. How emotions affect eating: a five-way model. Appetite. 2008;50(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. Dietary correlates of emotional eating in adolescence. Appetite. 2007;49(2):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Canetti L, Bachar E, Berry EM. Food and emotion. Behav Processes. 2002;60(2):157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(02)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Evers C, Marijn Stok F, de Ridder DT. Feeding your feelings: emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(6):792–804. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tice DM, Bratslavsky E, Baumeister RF. Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: if you feel bad, do it! Journal of personality and social psychology. 2001;80(1):53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiser S, Telch CF. Dialectical behavior therapy for Binge-Eating Disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55(6):755–768. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199906)55:6<755::aid-jclp8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burton P, J Smit H, J Lightowler H. The influence of restrained and external eating patterns on overeating. Appetite. 2007;49(1):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lluch A, Herbeth B, Mejean L, Siest G. Dietary intakes, eating style and overweight in the Stanislas Family Study. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2000;24(11):1493–1499. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weltzin TE, Weisensel N, Franczyk D, Burnett K, Klitz C, Bean P. Eating disorders in men: Update. The journal of men's health & gender. 2005;2(2):186–193. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baer RA, Smith GT, Allen KB. Assessment of mindfulness by self-report the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills. Assessment. 2004;11(3):191–206. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]