Abstract

PTL-1 is the sole homolog of the MAP2/MAP4/tau family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Accumulation of tau is a pathological hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease. Therefore, reducing tau levels has been suggested as a therapeutic strategy. We previously showed that PTL-1 maintains age-related structural integrity in neurons, implying that excessive reduction in the levels of a tau-like protein is detrimental. Here, we demonstrate that the regulation of neuronal ageing by PTL-1 occurs via a cell-autonomous mechanism. We re-expressed PTL-1 in a null mutant background using a pan-neuronal promoter to show that PTL-1 functions in neurons to maintain structural integrity. We next expressed PTL-1 only in touch neurons and showed rescue of the neuronal ageing phenotype of ptl-1 mutant animals in these neurons but not in another neuronal subset, the ventral nerve cord GABAergic neurons. Knockdown of PTL-1 in touch neurons also resulted in premature neuronal ageing in these neurons but not in GABAergic neurons. Additionally, expression of PTL-1 in touch neurons alone was unable to rescue the shortened lifespan observed in ptl-1 mutants, but pan-neuronal re-expression restored wild-type longevity, indicating that, at least for a specific group of mechanosensory neurons, premature neuronal ageing and organismal ageing can be decoupled.

The Caenorhabditis elegans model system has been the focus of many investigations into the processes that contribute towards ageing and longevity (reviewed in1). Surprisingly, initial studies did not detect major age-related changes in neuronal viability or gross axon integrity in the nervous system of C. elegans2, but close examination of neuronal morphology has revealed ageing phenotypes such as abnormal branching and blebbing along neuron processes3,4,5. In addition to structural changes, it was recently shown using patch-clamp recordings that C. elegans motor neurons demonstrate age-associated declines in activity6. Using the nematode model, we can dissect the relationship between neuronal and whole organism ageing, for example by examining whether accelerated neuronal ageing negatively affects the entire organism.

It was recently demonstrated that C. elegans undergoes progressive, age-dependent changes in the structural integrity of neurons3,4,5,7. Several factors that contribute to the maintenance of neuronal structural integrity have been identified, including HSF-15 and JNK-13, which have been demonstrated to act in a cell-autonomous manner. DAF-16, the FOXO transcription factor involved in insulin-like signalling8, also plays a role in neuronal aging. In the case of DAF-16, some data suggest that it functions cell autonomously3, while other evidence suggests a non-cell autonomous4 role in this ageing process. We have previously shown that the neuronal microtubule-associated protein (MAP) protein with tau-like repeats (PTL-1) is involved in the regulation of both organismal and nervous system ageing in C. elegans7. PTL-1 is the sole C. elegans homolog of members of the mammalian MAPT(tau)/MAP2/MAP4 family9,10. Mutations in the MAPT locus cause neuronal disorders including Frontotemporal dementia (reviewed in11). Furthermore, tau is the main component of neurofibrillary tangles found in the brains of individuals suffering from Alzheimer's disease or several other neurodegenerative conditions collectively known as tauopathies12,13,14,15. Due to this association with age-associated neurodegenerative disease in humans, it was striking to find that PTL-1 is involved in the maintenance of structural integrity in the C. elegans nervous system.

Our previous data indicated that the neurons of ptl-1(ok621) null mutants prematurely develop markers of neuronal ageing in touch receptor neurons (TRNs) and ventral nerve cord GABAergic neurons7. In our current investigation, we re-expressed PTL-1 in the ptl-1(ok621) null mutant specifically in all neurons to generate a pan-neuronal transgenic line, or in TRNs alone to generate a TRN-specific transgenic line. The TRNs consist of six mechanosensory neurons with specialised microtubule structures important for the response to gentle touch16,17, and incidentally are also the neurons in which PTL-1 is most highly expressed10,18. We examined both lifespan and neuronal ageing in these transgenic lines and found that (i) PTL-1 functions through neurons to regulate ageing, (ii) PTL-1 regulates neuronal ageing in a cell-autonomous manner, (iii) knockdown of ptl-1 by RNAi specifically in the TRNs affected TRN ageing but not ageing of another neuronal subset, and (iv) the processes that regulate organismal ageing and tissue-specific ageing are separable.

Results

The short-lived phenotype of ptl-1 null mutants is rescued by re-expression in all neurons but not in touch neurons alone

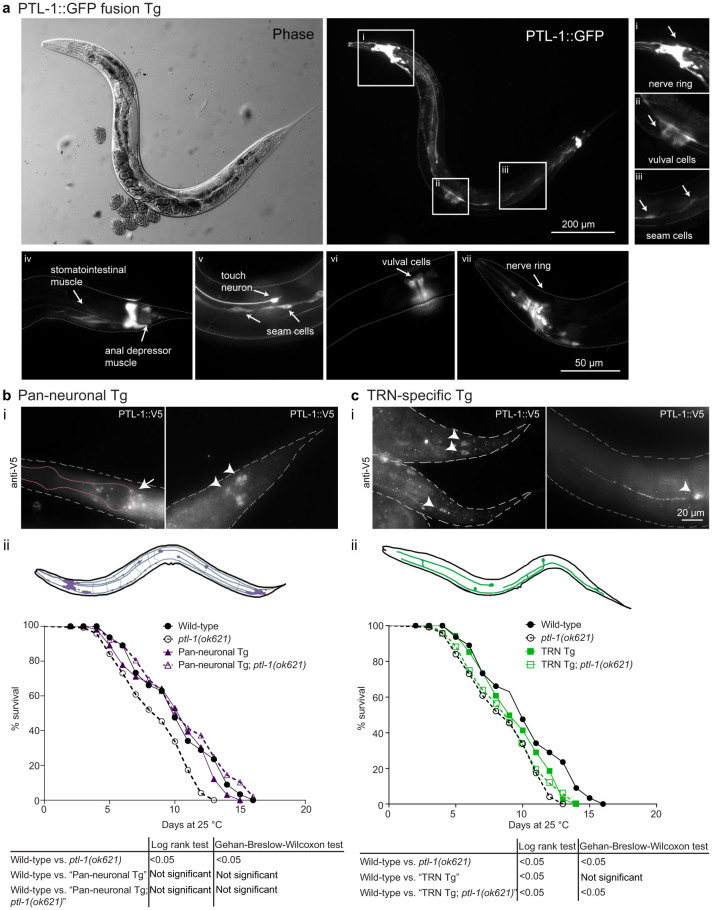

Previously, we demonstrated that re-expressing PTL-1 under the regulation of its endogenous promoter is sufficient to rescue both neuronal ageing and lifespan phenotypes observed in ptl-1 mutant animals7. PTL-1 expression is not restricted to neurons10,18; it is also expressed in non-neuronal tissues including vulval cells and stomatointestinal muscle18. By using a transgenic line expressing a PTL-1::GFP translational fusion protein, we confirmed this expression pattern (Figure 1a). Because we had already shown that PTL-1 expressed under the control of the ptl-1 promoter can rescue both neuronal and whole organism ageing, we aimed to test if re-expression specifically in neurons, or in the subset of TRNs (where PTL-1 is most highly expressed) would also rescue these phenotypes.

Figure 1. Pan-neuronal but not TRN-specific re-expression of PTL-1 rescues the short-lived phenotype of the ptl-1(ok621) null mutant.

The presence of the ptl-1(ok621) mutation in the genetic background of each transgenic line is indicated by the addition of “ptl-1(ok621)” in the strain name. (a) PTL-1 expression as shown by a translational GFP fusion is enriched in neurons and is also present in non-neuronal tissues. i–iii) Micrographs from a single transgenic animal indicating particular anatomical features where PTL-1::GFP is expressed including the nerve ring in the head, cells in the vulva and seam cells. iv–vii) Micrographs from other transgenic animals indicating PTL-1::GFP expression in muscle, seam cells, vulval cells and neurons. Anatomical features are highlighted by white arrows. (b) i. Staining for PTL-1::V5 in pan-neuronal re-expression line. The left panel shows the head, with the white arrow indicating neurons of the nerve ring and the pink outline indicates the approximate position of the pharynx. The right panel shows the tail, with the white arrowheads indicating tail neurons. ii. Lifespan assay conducted for pan-neuronal transgenic worms. (c) i. Staining for PTL-1::V5 in TRN-specific re-expression lines. The left panel indicates the tail, with PLM neurons indicated by white arrowheads. The right panel indicates the mid-body of the worm, showing an ALM neuron. The white arrowhead here indicates the cell body. ii. Lifespan assay for TRN-specific transgenic worms. Survival curves for control wild-type and ptl-1(ok621) animals in both graphs were obtained in the same experiment. n = 120 at day 0. Results of statistical analysis are indicated by p-values underneath each graph. Details of p-values are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Lifespan experiments were conducted twice independently, and the representative data shown are from one experiment. Survival curves obtained from the second independent lifespan experiment are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

We generated transgenic lines expressing ptl-1::V5 cDNA under the regulation of either the aex-3 pan-neuronal promoter or the mec-7 TRN-specific promoter. For clarity, we describe transgenic lines as either “Pan-neuronal Tg” or “TRN Tg” depending on the transgene, followed by “ptl-1(ok621)” if it is in the ptl-1 null mutant background. We immunostained for the V5 epitope tag present at the C-terminus of PTL-1 and confirmed that PTL-1 displayed broad neuronal expression (Figure 1bi) or expression in TRNs only (Figure 1ci) in these transgenic lines, respectively. We then performed lifespan assays to determine if either of these transgenes would rescue the shortened lifespan of ptl-1(ok621) null mutants7. We found that expressing PTL-1 in all neurons in “Pan-neuronal Tg” and “Pan-neuronal Tg; ptl-1(ok621)” populations resulted in a wild-type lifespan (Figure 1bii; Supplementary Figure S1a). In contrast, expressing PTL-1 in TRNs alone in the “TRN Tg; ptl-1(ok621)” strain did not rescue the lifespan phenotype of the ptl-1(ok621) null mutant, as the survival curve of this transgenic line was not significantly different from that of the ptl-1(ok621) control (log-rank test p-value = 0.25) (Figure 1cii; Supplementary Figure S1b). We also observed a small detrimental effect when PTL-1 was over-expressed in TRNs because the “TRN Tg” line without the ptl-1(ok621) mutation had a significantly shorter lifespan compared with wild-type controls according to the log-rank statistical test (p-value = 0.01) (Figure 1cii). This difference was not significant using the Wilcoxon test (p-value = 0.15), which places more weight on earlier deaths when comparing survival curves (GraphPad Prism 6).

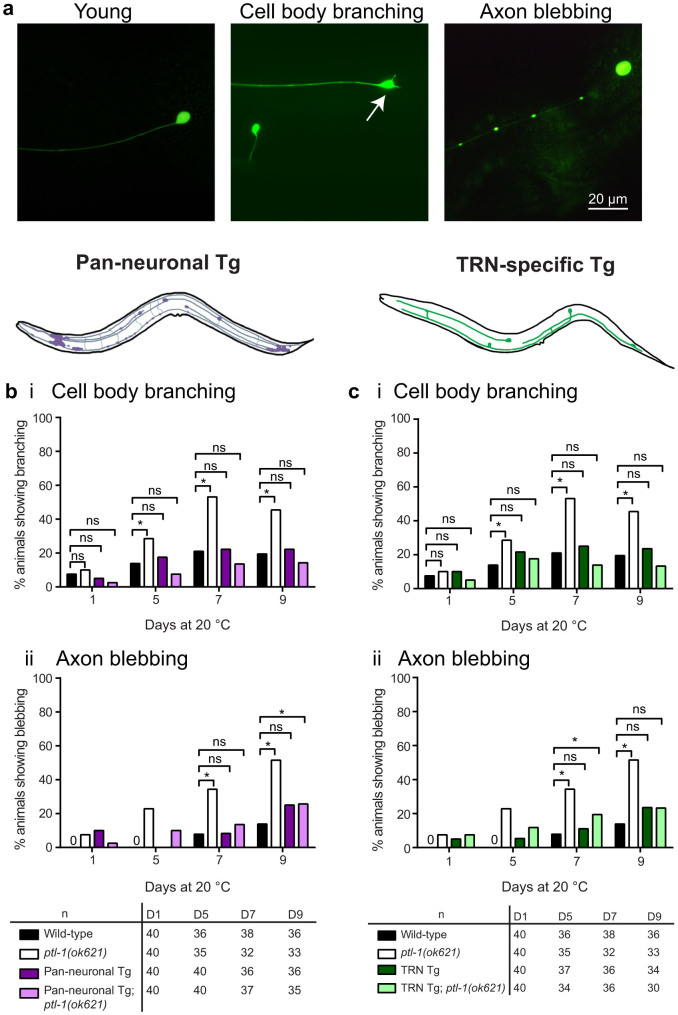

Premature ageing of touch neurons in ptl-1(ok621) mutants can be rescued by pan-neuronal and touch neuron-specific re-expression of PTL-1

We visualised cell body branching and axon blebbing in anterior TRNs on days 1, 5, 7 and 9 of adulthood using the Pmec-4::gfp(zdIs5) reporter. As previously described3,4,5,7, young TRNs have straight axons and a round, unbranched cell body, whilst older neurons display cell body branching and axon blebbing (Figure 2a). Re-expression of PTL-1 in all neurons in the ptl-1 null mutant background (“Pan-neuronal Tg; ptl-1(ok621)”) was able to fully rescue the premature incidence of neuronal branching and blebbing seen in ptl-1(ok621) animals (Figure 2b). Specifically, 14% of wild-type worms at day 5 of adulthood displayed cell body branching in the anterior TRNs compared with 29% of ptl-1(ok621) animals and 8% of “Pan-neuronal Tg; ptl-1(ok621)” animals (Figure 2bi). Rescue of the premature neuronal ageing phenotypes in ptl-1 mutants was also observed in the strain in which PTL-1 is expressed only in TRNs (“TRN Tg;ptl-1(ok621)”) (Figure 2c). For example, at day 7 of adulthood, 8% of wild-type animals displayed axon blebbing, compared with 35% in ptl-1(ok621) mutants and 20% in “TRN Tg;ptl-1(ok621)” animals (Figure 2cii). There was no observable detrimental effect of over-expressing PTL-1 in the TRNs in this experiment; at the same time point, 11% of TRN Tg animals displayed axon blebbing, which is not significantly different from wild-type (p-value = 0.44). In addition, we observed the same trends when the experiment was repeated at 25°C instead of at 20°C (Supplementary Figure S2ai,ii; bi,ii). These results indicate that PTL-1 acts within the neurons to regulate neuronal ageing, and that this regulation occurs in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 2. Pan-neuronal and TRN-specific re-expression of PTL-1 rescues the neuronal ageing phenotype in TRNs that is observed in the ptl-1(ok621) null mutant.

The TRNs were visualised using the Pmec-4::gfp (zdIs5) reporter. The presence of the ptl-1(ok621) mutation in the genetic background of each transgenic line is indicated by the addition of “ptl-1(ok621)” in the strain name. (a) Representative images of a young TRN, and TRNs showing cell body branching (arrow) or axon blebbing. (b) Neuron imaging assay conducted for pan-neuronal transgenic worms (“Pan-neuronal Tg”) showing (i) cell body branching and (ii) axon blebbing. (c) Neuron imaging assay conducted for TRN-specific transgenic worms (“TRN Tg”). Data for wild-type and ptl-1(ok621) animals in both graphs were obtained in the same experiment. n for each time-point is indicated under the graphs. The chi-squared statistical test was used to determine statistical significance. P-value is indicated by ns = not significant, *<0.05. Details of p-values are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Experiments were conducted twice independently, and the representative data shown are from one experiment.

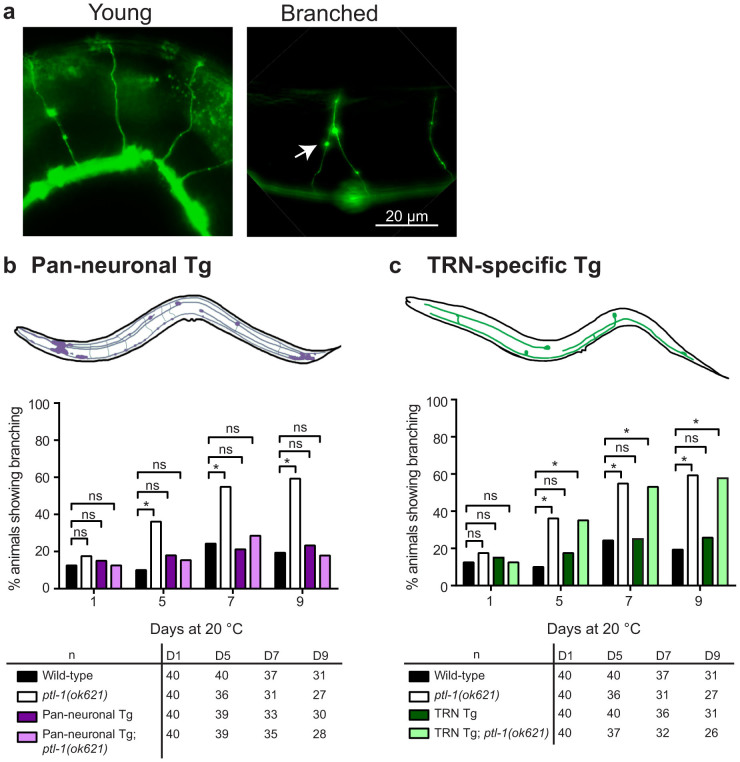

Premature ageing of GABAergic neurons in ptl-1(ok621) mutants can be rescued by pan-neuronal but not touch neuron-specific re-expression of PTL-1

To complement the above experiment, we investigated if PTL-1 expression specifically in one neuronal subset, the TRNs, is able to regulate neuronal ageing in other neurons, such as the GABAergic neurons. We visualised GABAergic neuron branching on days 1, 5, 7 and 9 of adulthood using the Punc-47::gfp(oxIs12) reporter. As noted previously3,4,5,7, GABAergic neurons in young animals do not show branching in the dorsally-projecting commissures, which are often branched in older adults (Figure 3a). We found that re-expressing PTL-1 in all neurons in the ptl-1 null mutant background completely rescued premature neuronal ageing observed in ptl-1(ok621) mutant animals (Figure 3b). For example, at day 5 of adulthood, 10% of wild-type animals displayed branching along the commissures of GABAergic neurons, compared with 36% of ptl-1(ok621) animals and 15% of “Pan-neuronal Tg; ptl-1(ok621)” animals (Figure 3b). In contrast, we did not observe a substantial difference in the incidence of abnormal structures between “TRN Tg; ptl-1(ok621)” animals (53%) at day 7 of adulthood compared with ptl-1(ok621) mutants at the same time point (55%), which are both significantly higher than wild-type (24%) (p-value = 0.0003 or 0.0002) (Figure 3c). This demonstrates that regulation of neuronal ageing by PTL-1 occurs cell-autonomously within the neuron. Additionally, over-expression of PTL-1 in TRNs alone does not negatively affect ageing in the GABAergic neurons, as the incidence of branching in “TRN Tg” animals at this time point was 25%, and therefore not significantly different from wild-type (p-value = 0.85). As for the neuronal ageing experiments in TRNs, we observed the same phenotypes at 25°C as at 20°C (Supplementary Figure S2aiii; biii).

Figure 3. Pan-neuronal but not TRN-specific re-expression of PTL-1, rescues the neuronal ageing phenotype in GABAergic neurons that is observed in the ptl-1(ok621) null mutant.

The GABAergic neurons were visualised using the Punc-47::gfp (oxIs12) reporter. The presence of the ptl-1(ok621) mutation in the genetic background of each transgenic line is indicated by the addition of “ptl-1(ok621)” in the strain name. (a) Representative images of young or branched GABAergic neurons. (b) Neuron imaging assay conducted for “Pan-neuronal Tg” worms. (c) Neuron imaging assay conducted for “TRN Tg” worms. Data for wild-type and ptl-1(ok621) animals in both graphs were obtained in the same experiment. n for each time-point is indicated under the graphs. The chi-squared statistical test was used to determine statistical significance. P-value is indicated by ns = not significant, *<0.05. Details of p-values are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Experiments were conducted twice independently, and the representative data shown are from one experiment.

Knockdown of PTL-1 in touch neurons only has a cell autonomous effect on neuronal ageing

In C. elegans, SID-1 is a transmembrane protein that allows the passive uptake of dsRNA and is required for systemic RNAi knockdown. Wild-type neurons are refractory to RNAi as they do not express SID-119,20; however, Calixto et al. showed that neuronal re-expression of SID-1 in a sid-1 null mutant, such as in TRNs, allowed RNAi knockdown to occur in these neurons21. The authors demonstrated that feeding mec-4 RNAi bacteria to these animals resulted in an expected loss of touch sensitivity, indicating that SID-1 expression in TRNs efficiently sensitized these neurons to knockdown by RNAi treatment21. We therefore complemented the assays involving tissue-specific re-expression of PTL-1 by reducing PTL-1 levels in one set of neurons. We investigated the effect of PTL-1 knockdown in the neuronal subset of TRNs on the age-associated loss of structural integrity. To this end, we first tested whether PTL-1 in TRNs could be effectively knocked down using this system. We fed empty vector (EV) and ptl-1 RNAi bacteria to animals that express both SID-1 only in the TRNs and a PTL-1::GFP fusion protein. These animals showed a loss of GFP signal in the TRNs in the ptl-1 RNAi treated cohort but not in those fed EV control RNAi bacteria (Supplementary Figure S3), demonstrating the effectiveness of the ptl-1 RNAi treatment.

We next crossed animals carrying a TRN GFP reporter with those that express SID-1 only in the TRNs. These animals that are henceforth referred to as the “TRN SID-1” strain carry a sid-1(qt2) mutation and a TRN-specific SID-1 rescue transgene (parent strain TU340321). TRN SID-1 animals were fed empty vector (EV) and ptl-1 RNAi feeding clones for two generations and were imaged on days 1, 3, 5 and 7 of adulthood to observe neuronal ageing. As an additional control, we carried out an experiment using animals containing only the TRN GFP reporter that are wild-type at the sid-1 locus and do not have the TRN SID-1 transgene. Here, we would expect that no RNAi knockdown would occur within neurons in these animals as the neurons do not express SID-1. As expected, these animals did not show a substantial difference in the incidence of abnormal neuronal structures between RNAi treatments (Figures 4a, 4b). In contrast, when observing the anterior TRNs in TRN SID-1 transgenic animals, we saw that worms fed with ptl-1 RNAi bacteria had a higher incidence of cell body branching and axon blebbing compared with those fed EV bacteria. Specifically, 70% of TRN SID-1 animals fed ptl-1 RNAi bacteria displayed cell body branching at day 7 compared with 47% in the EV RNAi control, and 53% of ptl-1 RNAi-fed animals displayed axon blebbing compared with 30% of the control population (Figure 4ai). In addition, we observed that TRN SID-1 animals displayed a relatively high frequency of axon branching (Figure 4aii), which is normally only present in late stage (day 10) adult animals5,7. TRN SID-1 animals fed with both control and ptl-1 RNAi treatments showed considerably higher levels of axon branching in the anterior TRNs compared with wild-type controls, although transgenic animals fed ptl-1 bacteria displayed a higher incidence of this phenotype compared with EV treatments (Figure 4ai). This could be due to the expression of multiple TRN-specific transgenes (both Pmec-18::sid-1 and Pmec-4::gfp) that may alter the development or ageing process of the neuron.

Figure 4. Knockdown of PTL-1 in touch neurons has a cell autonomous effect on neuronal ageing.

Strains labelled as zdIs5 or oxIs12 indicate the allele name of the gfp reporter, are wild-type at the SID-1 locus and do not contain a SID-1 transgene. SID-1 transgenic worms are labelled as “sid-1(qt2);TRN SID-1” to indicate the presence of the sid-1 mutation and Pmec-18::sid-1 transgene. The RNAi treatment is either empty vector (EV) or ptl-1 and is indicated after the strain name. (a) i. TRN imaging assay for animals carrying the zdIs5 reporter, indicating data for cell body branching, axon blebbing and axon branching. (a) ii. Micrograph shows an example of the axon branching phenotype. (b) GABAergic imaging assay for animals carrying the oxIs12 reporter. n for each sample is indicated in the table. Statistical analysis: chi-squared test, p-value is indicated by ns = not significant, *<0.05. Details of p-values are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Experiments were conducted twice independently, and the representative data shown are from one experiment.

We then further tested the effect of the loss of PTL-1 in TRNs by examining neuronal ageing in a different set of neurons. For this, we generated a strain expressing a GABAergic neuron GFP reporter in a TRN SID-1 background. As SID-1 is only expressed in the TRNs, we would not expect PTL-1 levels in the GABAergic neurons to be affected by feeding RNAi bacteria in this strain. Therefore, although PTL-1 levels in the TRNs of TRN SID-1 animals should decrease with ptl-1 feeding RNAi, PTL-1 expression in the GABAergic neurons of these animals should remain at endogenous levels. As above, we also performed a control RNAi experiment using animals containing only the GABAergic neuron GFP reporter and not the TRN SID-1 transgene. When GABAergic neuron ageing in TRN SID-1 transgenic worms was monitored, we observed no difference between ptl-1 RNAi treatment and EV treatment (Figure 4b). This demonstrates that loss of PTL-1 in the TRNs appears not to affect neuronal ageing in the GABAergic neurons.

Taken together, these data from tissue-specific re-expression and RNAi knockdown experiments indicate that the effect of ptl-1 on neuronal ageing is cell autonomous.

Discussion

Given the clinical relevance of tau pathology in neurodegenerative disease, we aimed to investigate the function of the tau-like protein PTL-1 in the context of neuronal ageing. The key findings of our study in C. elegans are: (i) the tau/MAP2/MAP4 homologue PTL-1 functions through neurons to regulate organismal ageing, (ii) PTL-1 regulates neuronal ageing in a cell-autonomous manner, and (iii) the processes that regulate organismal ageing and tissue-specific ageing can be separable.

Previous research has highlighted the importance of neurons, and sensory neurons in particular, in the regulation of lifespan. Examples include the role of olfactory neurons and ciliated sensory neurons in inhibiting longevity22,23, and that of thermosensory neurons in regulating lifespan at high temperatures24. Our data indicate that PTL-1 functions through neurons to regulate whole organismal lifespan. We also demonstrate that expression of PTL-1 in the mechanosensory TRNs alone, the neuronal subset in which PTL-1 is most highly expressed10,18, is not sufficient to maintain a wild-type lifespan. It is likely that PTL-1 regulates organismal ageing through a combination of other neuronal subsets. We also acknowledge the possibility that there may be a requirement for a threshold number of neurons to be affected in order to negatively affect longevity, such that defects in 6 (TRNs only) of 302 total neurons may be insufficient to result in a premature lifespan. However, our observation that over-expression of PTL-1 in TRNs on a wild-type background has a small negative impact on lifespan suggests that the status of TRNs is particularly significant compared with other neuronal populations.

Using a combination of tissue-specific transgene expression and RNAi knockdown, we also showed that PTL-1 regulates neuronal structural integrity in a cell autonomous manner. Re-expression or knockdown of PTL-1 in TRNs alone contributed to the structural stability in those neurons but failed to affect ageing in another neuronal subset, the GABAergic neurons. PTL-1 binds to and stabilizes microtubules9,10,25, and this function may contribute to cell autonomous regulation of structural integrity. Consistent with this, we have previously shown that a microtubule-binding domain-deficient mutant of PTL-1 (tm543 allele) also displays the same neuronal ageing phenotype as ptl-1 null mutants7.

Our previous work has demonstrated that ptl-1(ok621) null mutants display both premature organismal ageing and premature neuronal ageing7. We have now shown that animals that express PTL-1 in TRNs alone have a shortened lifespan compared with wild-type as have ptl-1(ok621) null mutants, but that their TRNs age at the same rate as wild-type animals (Figure 1Bii, 2c). This demonstrates that PTL-1-mediated processes that influence lifespan or neuronal ageing can be decoupled from each other. A similar segregation has been observed for components of the insulin-like/IGF-1 signalling pathway. Long-lived daf-2/insulin receptor mutants show less neuronal branching in early adulthood compared with wild-type, and this effect is ameliorated in daf-2;daf-16/FOXO transcription factor double mutants, which have a wild-type lifespan3,8. However, RNAi-mediated knockdown of daf-16 in non-neuronal tissues in a daf-2 mutant results in an animal with wild-type lifespan, but has no effect on the daf-2-mediated delay of neuronal ageing3. Therefore, although neuronal cell body branching and axon blebbing increase with temporal age, tissue-specific ageing and whole organism ageing appear to be separable. This suggests that the mechanisms that define these ageing processes contain both distinct and overlapping processes. It is of considerable interest in the fields of ageing and neurodegeneration to identify the genetic players involved in these processes.

We have shown that PTL-1 in C. elegans functions in neurons to regulate both whole organism ageing and neuronal ageing. Although several lines of evidence indicate that PTL-1 is expressed mainly in the nervous system10,18, until now it remained to be determined whether PTL-1 was indeed acting through neurons to mediate these processes. We have proven this by demonstrating that a transgenic line expressing PTL-1 only in neurons is able to rescue both premature lifespan and neuronal ageing in a ptl-1 mutant. We have now also shown that the regulation of neuronal ageing by PTL-1 is cell autonomous. The role of PTL-1 in regulating these ageing processes as a neuronal MAP is particularly striking due to its homology with mammalian tau, which plays a critical role in neurodegenerative disease14. Understanding the physiological roles of a tau-like protein in C. elegans may provide important information on human neurodegeneration and ageing.

Methods

Strain information

C. elegans strains were cultured on nematode growth media26 (NGM) agar plates seeded with the Escherichia coli strain OP50. Hermaphrodite animals were used for all experiments. The wild-type strain used for all experiments is N2 (Bristol). Strains N2, RB809 ptl-1(ok621), TU3403 ccIs4251 [Pmyo-3::gfp(NLS)::lacZ(pSAK2) + Pmyo-3::gfp(pSAK4) + dpy-20(+)];uIs71 [pCFJ90(Pmyo-2::mCherry) + Pmec-18::sid-1];sid-1(qt2), CZ10175 zdIs5[Pmec-4::gfp + lin-15(+)] I and EG1285 oxIs12[Punc-47::gfp + lin-15(+)] X were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Centre (CGC), and FX00543 ptl-1(tm543) was obtained from the National Bioresource Project, Japan (Dr S. Mitani). ptl-1 mutant lines RB809 and FX00543 were both outcrossed six times to wild-type and renamed APD004 and APD015, respectively. For neuron imaging assays, strains involved were crossed with CZ10175 to visualise TRNs and EG1285 to visualise GABAergic motor neurons. For tissue-specific RNAi strains, sid-1(qt2) mutants were selected by screening for insensitivity (lack of paralysis) to knockdown of unc-22 and the missense mutation confirmed by sequencing.

List of strains generated

APD050: zdIs5; sid-1(qt2); uIs71. APD066: oxIs12; sid-1(qt2); uIs71. APD070: apdIs9[Pmec-7p:PTL1-V5:PTL-1 3′UTR; Pmyo-2:mCherry; Prpl-28::PuroR::rpl-16_outron::NeoR::let-858_3′UTR], outcrossed six times to wild-type. APD074: apdIs9; oxIs12; ptl-1(ok621). APD075: apdIs9; zdIs5; ptl-1(ok621). APD076: apdIs9; ptl-1(ok621). APD081: apdIs9; oxIs12. APD082: apdIs9; zdIs5. APD096: apdIs10[Paex-3:PTL1-V5:PTL-1 3′UTR; Pmyo-2:mCherry; Prpl-28::PuroR::rpl-16_outron::NeoR::let-858_3′UTR], outcrossed six times to wild-type. APD097: apdIs10; zdIs5. APD098: apdIs10; zdIs5I; ptl-1(ok621). APD099: apdIs10; oxIs12. APD100: apdIs10; oxIs12; ptl-1(ok621). APD105: apdIs10; ptl-1(ok621). APD130 apdEx10[ptl-1p:PTL-1-GFP:unc-54 3′ UTR; rpl-28p::PuroR::rpl-16_outron::NeoR::let-858_39UTR]; sid-1(qt2);uIs71.

Generation of transgenic lines

The ptl-1 promoter, PTL-1 cDNA tagged at the C-terminus with V5, and the PTL-1 3′UTR was amplified as previously described7. aex-3 and mec-7 promoters were amplified from genomic DNA using primers GGGGCAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGGCTTCCACAAAAACTGCCGC and GGGGCTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGTTTTTATTAGGATAGGTACATTGG (containing attB4 and attB1r sites respectively), or primers GGGGCAACTTTGTATAGAAAAGTTGTAGTAATCTAGAAATGTAAACC and GGGGCTGCTTTTTTGTACAAACTTGGTTGCTTGAAATTTGGACCC, then cloned using the Gateway (Life Technologies) protocol into pDONRP4P1R to generate pSB011 and pY006. The multisite Gateway method was then used to combine the pENTR clones pSB011 (aex-3 promoter), pY002 (PTL-1::V5) and pY003 (PTL-1 3′UTR) or pY006 (mec-7 promoter), pY002 and pY003 into dual antibiotic selection destination vector pBCN40 (J Semple and B Lehner) containing visual marker Pmyo-2::mCherry to generate pY011 and pY010. Transgenic worms were generated by biolistic transformation using the PDS-1000/He™ particle delivery system (BioRad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Wild-type worms were bombarded with 7 μg of linearised plasmid DNA using previously established methods27. Selection post-bombardment was undertaken using the dual antibiotic selection protocol28, as previously described7. Integrated lines were obtained and outcrossed six times to wild-type.

Neuronal imaging experiments

Age-matched animals synchronised by egg-laying were cultured on plates at 20°C or 25°C. At the start of the experiment, animals were one day-old adults in all cases. To separate adult worms from their progeny, adult worms were moved to new NGM plates every second day until the assay was completed. Assays were conducted blind to the genotype of the worms. To score the incidence of aberrant neuronal structures in TRNs, worms were scored as positive if the ALM neurons displayed branching or blebbing at the cell body or axon. For scoring in GABAergic neurons, worms were scored as positive if at least one of the observed commissures displayed branching. The proportion of animals scored as positive was expressed then as a percentage of the sample size observed at that time point.

Lifespan assays

Age-matched animals synchronised by egg-laying were cultured on plates at 25°C and the number of surviving animals recorded every day until death. Two independent lifespan experiments were conducted, each with 120 one day-old adults per strain plated at the start of each assay. Animals that were lost or displayed internal hatching or bursting were censored. Pan-neuronal and TRN-specific Tg lines were assayed together with the same cohort of wild-type and ptl-1(ok621) control strains in each independent lifespan assay. To separate adult worms from their progeny, adult worms were moved to new NGM plates every second day until the assay was completed. Assays were conducted blind to the genotype of the worms. Survival curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 6.

RNA interference experiments

Experiments were conducted at 20°C. sid-1(qt2) animals expressing SID-1 in TRNs only (APD050 and APD066) were synchronised by hypochlorite bleaching and larval stage 1 worms plated onto carbenicillin plates seeded with RNAi bacteria (HT115 E. coli) that either contained the pL4440 empty vector (EV), or pL4440 containing cloned ptl-1 or unc-22 DNA generated by the Ahringer laboratory29. Strains that are wild-type at the sid-1 locus were used as negative controls. unc-22 knockdown was used as a control for the experiment; knockdown of unc-22 in muscle results in paralysis, so animals that have the sid-1(qt2) mutation are no longer susceptible to RNAi knockdown in muscle and will not be paralysed, whereas animals that are wild-type for sid-1 will be paralysed. Bacterial cultures were induced to express dsRNA using 3 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After two generations fed on RNAi bacteria, animals were imaged at day 1, 3, 5 and 7 of adulthood to visualise TRNs or GABAergic neurons. To maintain knockdown, animals were transferred to new RNAi plates on days 2, 4 and 6 of the experiment. Scoring was conducted in the same manner as for other neuronal imaging assays. Imaging was conducted blind to the identity of the RNAi clones. To test knockdown of ptl-1 in TRNs by feeding RNAi, PTL-1::GFP animals were treated as described above by feeding either EV or ptl-1 RNAi bacteria and imaged after two generations of RNAi treatment.

Immunofluorescence

One day-old adults synchronised by egg-laying and cultured at 23°C were used for all experiments. Animals were permeabilised using a freeze-crack protocol as previously described30. Samples were immediately fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for >12 hours. The primary antibody used was mouse monoclonal anti-V5 (R960-25, Life Technologies) [1:200]. The secondary antibody used was goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor-568 (Sigma) [1:500]. All antibody dilutions were made in 30% (v/v) normal goat serum (Life Technologies). Samples were mounted onto microscope slides using VectaShield mounting medium (Vector Labs). Samples were imaged using a BX51 Microscope (Olympus). Micrographs were captured using AnalySIS software (Olympus).

Statistical analysis

The α-level is 0.05 for all analyses. Survival curves were analysed in GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc.) to provide two-tailed p-values. Tests used were the log-rank test, which gives equal weight to deaths at all time points, and the Wilcoxon test, which gives more weight to deaths at early time points31. The log-rank test is commonly used for C. elegans lifespan data3,23,32 but we also report p-values from the Wilcoxon test to accommodate the possibility that hazard ratios were not consistent through the assay. For neuron imaging experiments, we grouped data into categories of “displays branching/blebbing” or “does not display branching/blebbing” and used Pearson's chi-squared test in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft) to determine if the incidence of branching/blebbing in a mutant population at a single time point is different from the ‘expected value' of the wild-type strain at the same time point. This analysis provides one-tailed p-values that were used to determine if the incidence of abnormal neuronal structures in a mutant strain at a time point was different from the wild-type strain.

Author Contributions

Y.L.C., X.F., J.G. and H.R.N. designed experiments. Y.L.C. and X.F. performed experiments. Y.L.C., X.F., J.G. and H.R.N. analysed data. Y.L.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. Y.L.C., X.F., J.G. and H.R.N. reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

J.G. is funded by the Estate of Dr Clem Jones AO, and grants from the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr M. Hilliard for providing reagents, and Drs J. Semple and B. Lehner for dual antibiotic selection vectors. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). The authors thank members of the Nicholas lab and Götz lab for helpful discussions.

References

- Lapierre L. R. & Hansen M. Lessons from C. elegans: signaling pathways for longevity. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 23, 637–644 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon L. A. et al. Stochastic and genetic factors influence tissue-specific decline in ageing C. elegans. Nature 419, 808–14 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank E. M., Rodgers K. E. & Kenyon C. Spontaneous age-related neurite branching in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 31, 9279–88 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C. L., Peng C. Y., Chen C. H. & McIntire S. Genetic analysis of age-dependent defects of the Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 9274–9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M. L. et al. Neurite Sprouting and Synapse Deterioration in the Aging Caenorhabditis elegans Nervous System. J Neurosci 32, 8778–8790 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J. et al. Functional aging in the nervous system contributes to age-dependent motor activity decline in C. elegans. Cell Metab 18, 392–402 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew Y. L., Fan X., Gotz J. & Nicholas H. R. PTL-1 regulates neuronal integrity and lifespan in C. elegans. J Cell Sci 126, 2079–91 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C., Chang J., Gensch E., Rudner A. & Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366, 461–4 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott J. B., Aamodt S. & Aamodt E. ptl-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans gene whose products are homologous to the tau microtubule-associated proteins. Biochemistry 35, 9415–23 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. et al. PTL-1, a microtubule-associated protein with tau-like repeats from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Sci 109 (Pt 11), 2661–72 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade-Martins R. Genetics: The MAPT locus-a genetic paradigm in disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Neurol 8, 477–8 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. & Leugers C. J. Tau and tauopathies. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 107, 263–93 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C. X. & Grundke-Iqbal I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 7, 656–64 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittner L. M. & Gotz J. Amyloid-beta and tau--a toxic pas de deux in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 65–72 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J., Xia D., Leinenga G., Chew Y. L. & Nicholas H. What Renders TAU Toxic. Front Neurol 4, 72 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M. & Sulston J. Developmental genetics of the mechanosensory neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 82, 358–70 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M. et al. The neural circuit for touch sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci 5, 956–64 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon P. et al. The invertebrate microtubule-associated protein PTL-1 functions in mechanosensation and development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Genes Evol 218, 541–51 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg E. H. & Hunter C. P. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 301, 1545–7 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston W. M., Molodowitch C. & Hunter C. P. Systemic RNAi in C. elegans requires the putative transmembrane protein SID-1. Science 295, 2456–9 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto A., Chelur D., Topalidou I., Chen X. & Chalfie M. Enhanced neuronal RNAi in C. elegans using SID-1. Nat Methods 7, 554–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcedo J. & Kenyon C. Regulation of C. elegans longevity by specific gustatory and olfactory neurons. Neuron 41, 45–55 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J. & Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 402, 804–9 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J. & Kenyon C. Regulation of the longevity response to temperature by thermosensory neurons in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 19, 715–22 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien N. W., Wu G. H., Hsu C. C., Chang C. Y. & Wagner O. I. Tau/PTL-1 associates with kinesin-3 KIF1A/UNC-104 and affects the motor's motility characteristics in C. elegans neurons. Neurobiol Dis 43, 495–506 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V., Casey E., Collar D. & Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 157, 1217–26 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple J. I., Biondini L. & Lehner B. Generating transgenic nematodes by bombardment and antibiotic selection. Nat Methods 9, 118–9 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser A. G. et al. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408, 325–30 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden S. L. & Kimble J. Confocal methods for Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods Mol Biol 122, 141–51 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin D., Cheung Y. & Parmar M. Survival Analysis: A Practical Approach (Wiley, NJ, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Xiong C. & Kornfeld K. Measurements of age-related changes of physiological processes that predict lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 8084–9 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material