Abstract

Diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction are more likely to die than nondiabetic patients. In the present study we examined the effect of insulin resistance on myocardial ischemia tolerance. Hearts of rats, rendered insulin resistant by high-sucrose feeding, were subjected to ischemia/reperfusion ex vivo. Cardiac power of control hearts from chow-fed rats recovered to 93%, while insulin-resistant hearts recovered only to 80% (P<0.001 vs. control). Unexpectedly, impaired contractile recovery did not result from an impairment of glucose oxidation (576±36 vs. 593±42 nmol/min/g dry weight; not significant), but from a failure to increase and to sustain oxidation of the long-chain fatty acid oleate on reperfusion (1878±56 vs. 2070±67 nmol/min/g dry weight; P<0.05). This phenomenon was due to a reduced ability to transport oleate into mitochondria and associated with a 38–58% decrease in the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) levels. Contractile function was rescued by replacing oleate with a medium-chain fatty acid or by restoring UCP3 levels with 24 h of food withdrawal. Lastly, the knockdown of UCP3 in rat L6 myocytes also decreased oleate oxidation by 13–18% following ischemia. Together the results expose UCP3 as a critical regulator of long-chain fatty acid oxidation in the stressed heart postischemia and identify octanoate as an intervention by which myocardial metabolism can be manipulated to improve function of the insulin-resistant heart.—Harmancey, R., Vasquez, H. G., Guthrie, P. H., Taegtmeyer, H. Decreased long-chain fatty acid oxidation impairs postischemic recovery of the insulin-resistant rat heart.

Keywords: high-sucrose diet, myocardial metabolism, type 2 diabetes, cardiac function, uncoupling proteins

Type 2 diabetes mellitus increases both the incidence of myocardial infarction and death rates 2- to 3-fold, independent from other known risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (1). Following an episode of acute ischemia and revascularization intervention, the recovery of contractile function is decreased in diabetic individuals (2). Increased mortality in this subcategory of patients has been linked to a greater impairment of myocardial reperfusion, a larger infarct size, and higher rates of new onset severe congestive heart failure (3, 4). These poor outcomes suggest that diabetes mellitus may perturb myocardial energy substrate metabolism during the peri-infarctional period in ways that directly affect ischemia tolerance (5).

Myocardial metabolism of energy providing substrates in diabetes is characterized by an increase in fatty acid uptake and oxidation accompanied by a simultaneous decrease in glucose and lactate utilization (6, 7). An ensuing decrease in myocardial efficiency may render the heart more vulnerable to an ischemic insult on reperfusion (6). The impairment of insulin-mediated glucose uptake in the heart of patients with type 2 diabetes has been proposed to contribute to this shift toward greater fatty acid oxidation, as it would reduce both glycolytic flux and glucose oxidation. However, the presence of confounding systemic factors makes it difficult to evaluate in vivo the consequences of myocardial insulin resistance. The generation of mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of the insulin receptor (CIRKO) has demonstrated that impaired myocardial insulin signaling accelerates left ventricular dysfunction postinfarction (8). But here, again, the complete suppression of insulin signaling fails to reproduce the phenotype of patients with type 2 diabetes, who show increased basal myocardial Akt activity despite the impairment of insulin-mediated glucose uptake (9).

We previously reported on the isolated working heart perfusion of rats fed a high-sucrose diet (HSD) as a model to investigate the effects of myocardial insulin resistance in the heart (10). The feeding procedure impairs both systemic and myocardial glucose uptake in response to insulin, and induces compensatory hyperinsulinemia with a subsequent increase in basal Akt activity in the heart, all of which are consistent with the pathophysiology of myocardial insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes (9). Our previous study showed that insulin resistance improved contractile function in hearts subjected to metabolic and hemodynamic stress (10). In the present study, we employed this model to investigate the consequences of myocardial insulin resistance on cardiac metabolism and function following an episode of total global ischemia. Our results demonstrate that myocardial insulin resistance induces metabolic derangements that negatively impact contractile recovery on reperfusion. Surprisingly, these metabolic derangements could be traced to a decreased capacity for mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain fatty acids, rather than a change in glucose oxidation. Gene knockdown experiments performed in vitro with rat L6 myocytes support a role of the mitochondrial uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) in sustaining long-chain fatty oxidation postischemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200 to 224 g) were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and housed in the University of Texas–Houston Medical School Animal Care Center. Animals were fed an HSD (D11725; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or maintained on a standard laboratory chow (LabDiet 5001; PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO, USA). All experiments were performed after 8 to 10 wk on the feeding protocol and approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Plasma parameters

Systemic insulin sensitivity was assessed after 18 h of food withdrawal. Plasma insulin levels were measured by the Mouse Metabolism Core at the Diabetes Research Center, Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX, USA). For the insulin tolerance test, rats were injected subcutaneously in the subscapular region with a single dose of 0.5 U insulin/kg body weight (Humulin R; Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA). A glucose tolerance test was performed by gavaging rats with a 50% (w/v) glucose solution at 1 g glucose/kg body weight. Blood glucose levels were measured from the tail vein using a OneTouch reader (LifeScan, Milpitas, CA, USA).

Working heart preparation

Hearts were perfused as working hearts (11) at 37°C with nonrecirculating Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing glucose (25 mM), sodium oleate, or sodium octanoate (0.8 mM) bound to bovine serum albumin, fatty acid-free (Probumin; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and insulin (5 ng/ml) and equilibrated with 95% O2-5%CO2. The perfusate [Ca2+] was 2.5 mM. All perfusions were carried out on spontaneously beating hearts with a preload of 15 cmH2O and an afterload of 100 cmH2O. Aortic flow, coronary flow, and metabolic rates were measured every 5 min, except during the first 5 min of reperfusion, when the measurements were performed every minute. Heart rate was measured continuously with a 3 French catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) connected to a PowerLab 8/30 recording system (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA).

Perfusion protocol

Hearts were perfused for 20 min under baseline conditions. Total, global, normothermic ischemia was then induced by clamping both the aortic and the atrial line of the perfusion system. After 15 min, hearts were reperfused for 30 min by unclamping both lines. At the end of the protocol, hearts were freeze-clamped with aluminum tongs cooled in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. In separate experiments, hearts were freeze-clamped at 20 min (baseline) or at the end of ischemia. Another set of hearts was quickly rinsed in ice-cold saline on removal from the animals and immediately freeze-clamped (nonperfused controls).

Assessment of contractile performance

Cardiac performance was expressed as cardiac power (W), and calculated as the product of cardiac output (coronary plus aortic flow, m3/s) times the afterload (Pa). For all parameters, the average value measured during the preischemic period was taken as the reference value (baseline). Unless indicated otherwise, postischemic cardiac parameters were determined by averaging the values obtained during the last 15 min of reperfusion.

Assessment of myocardial oxygen consumption and metabolic rates

Values were determined as described previously (10, 12). Briefly, myocardial oxygen consumption (MVo2; μmol/min) was measured with a YSI 5300A biological oxygen monitor (YSI Life Sciences, Yellow Springs, OH, USA), using 1.06 mM for the concentration of dissolved O2 at 100% saturation. Rates of glucose uptake and oxidation were determined by quantitative collection of [3H]2O and [14C]O2 released in the coronary effluent using [2-3H]glucose (0.05 μCi/ml) and [U-14C]glucose (0.1 μCi/ml) as a tracer, respectively. Rates of fatty acid oxidation were determined in a separate set of perfusions by quantitative recovery of [3H]2O from [9,3-3H]oleate (0.1 μCi/ml) or n-[8-3H]octanoate (0.08 μCi/ml) in the coronary effluent.

Real-time PCR measurements

Total RNA was extracted from L6 cells using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA), and transcript levels were determined using Taqman quantification. Primers and probes used for the quantification of the UCP3 and cyclophilin A have been described elsewhere (10). Total RNA was extracted from rat hearts with an RNeasy fibrous tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The spliced form of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA was quantified according to the method developed by Hirota et al. (13), using GGATGAATGCCCTGGTTACTGAAG for the forward primer, AGAGGCAACAGCGTCAGAATCCA for the reverse primer, and AGGTGCAGGCCCAGTTGTCACCTCC for the probe.

Biochemical analyses

The tissue extraction and quantification of glycogen and total triglycerides was performed as reported previously (14). Caspase 3 activity was determined by cleavage of the labeled substrate DEVD-pNA (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA). Cardiac protein carbonyl content was quantified by ELISA (Amsbio, Lake Forest, CA, USA). Lactate dehydrogenase release in the coronary effluent was measured with a LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Cell culture and transfections

L6 rat myoblasts were cultured in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml glucose, l-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were differentiated into myocytes by replacing the fetal bovine serum by 2% horse serum. Gene knockdown was performed with Silencer Select predesigned siRNA targeting UCP3 (s130536 and s130537) and the nontargeting negative control no. 1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Myocytes were trypsinized and reverse transfected with 25 nM siRNA using lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Life Technologies). Myocytes were used for experiments 24 h post-transfection.

Rates of cellular oleate oxidation

L6 cells were serum deprived for 5 h in DMEM supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin. Ischemia was then simulated by layering mineral oil over a thin film of PBS (15). Next, the cells were washed 5× with Krebs Henseleit buffer to remove the mineral oil and “reperfused” in the assay medium consisting of Krebs Henseleit buffer supplemented with sodium oleate (0.4 mM) bound to bovine serum albumin, l-carnitine (1 mM), glucose (1 mM), and [9,3-3H]oleate (0.2 μCi/ml) as the tracer.

Immunoblot analyses

Total cell lysates and tissue homogenates were prepared in presence of phosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and protease (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) inhibitors. Levels of total and/or phosphorylated proteins were detected by immunoblotting using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα; Thr172), total AMPKα, phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC; Ser79), and total ACC antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody was from Fitzgerald Industries International (Acton, MA, USA). Carnitine palmitoyl-transferase 1B (CPT1B) antibody was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The commercial source for other antibodies was reported previously (10). Signals were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were performed by Student's t test or ANOVA with the Newman-Keuls post hoc correction. The relationship between cardiac power and rates of glucose or oleate oxidation was assessed with Spearman's correlation coefficient. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Basal insulin signaling through Akt is increased in the heart of HSD-fed, insulin-resistant rats

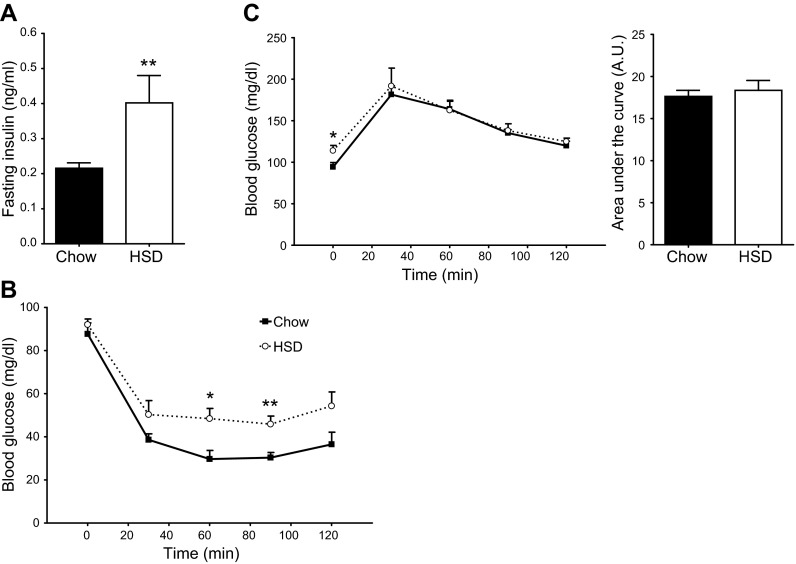

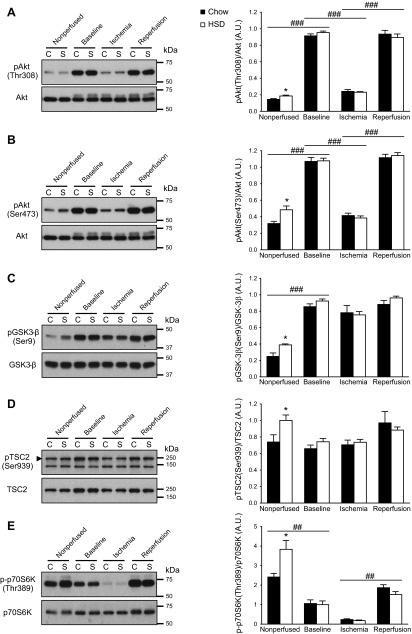

Fasting plasma insulin levels almost doubled for rats fed an HSD when compared to rats fed the regular chow diet (Fig. 1A). Systemic insulin sensitivity was also significantly impaired (Fig. 1B). Although fasting blood glucose levels increased by 21%, the animals' tolerance to glucose by single-bolus ingestion was maintained (Fig. 1C). As reported in our previous study (10), basal myocardial Akt phosphorylation at both Thr308 and Ser473 was increased (Fig. 2A, B). The increased activity of Akt in nonperfused hearts was confirmed by the increased phosphorylation of the kinase's direct downstream targets glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK3-β) at Ser9 and tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) at Ser939 (Fig. 2C, D). The 59% increase in p70 ribosomal S6 kinase phosphorylation at Thr389 is consistent with reduced RAG activity of TSC2 and increased mTOR complex 1 signaling (Fig. 2E). Taken together, the data indicate that, even though systemic insulin sensitivity is reduced, basal insulin signaling through Akt is actually enhanced in the heart of HSD-fed rats, which is probably due to the hyperinsulinemic state of these animals.

Figure 1.

Impaired insulin sensitivity but normal glucose tolerance in rats fed a high-sucrose diet. Measurements of fasting plasma insulin levels (A) and of blood glucose levels following injection of insulin (B) or a glucose load (C) were performed in chow-fed (solid squares with solid trace) and HSD-fed (open circles with dotted trace) rats. Data represent means ± se from 6–7 animals/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. chow.

Figure 2.

Increased basal Akt activity in insulin-resistant hearts is normalized during ex vivo perfusion. Immunoblot analyses of the phosphorylation level of Akt at Thr308 (A) and at Ser473 (B), GSK-3β at Ser9 (C), TSC2 at Ser939 (D), and p70S6K at Thr389 (E) were performed in nonperfused hearts of chow-fed (C; solid bars) and HSD-fed (S; open bars) rats and in isolated working hearts after 20 min perfusion (baseline), 15 min of ischemia, and 30 min of reperfusion. A representative sample for each condition is shown on the immunoblots. Data are means ± se of 5–6 animals/group. *P < 0.05 vs. chow; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

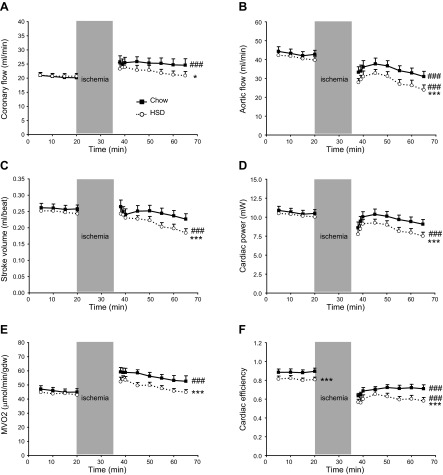

Postischemic contractile recovery of the insulin-resistant heart is impaired

All baseline fluid dynamic parameters and myocardial oxygen consumption were identical in both groups (Fig. 3A–E), with the exception of cardiac efficiency, which was slightly reduced for HSD-fed rats (Fig. 3F). On reperfusion, the time necessary for the return of contractile function was not significantly different between chow-fed (141±36 s; n=13) and HSD-fed (168±53 s; n=12) rats (P=0.15). While coronary flow increased in both groups, most likely in order to restore myocardial oxygen tension to a normal operating level, the increase was less important in the heart of HSD-fed animals (Fig. 3A). Aortic flow decreased, but was more severely depressed for HSD-fed rats (Fig. 3B). Consequently, cardiac output was lower for the reperfused, insulin-resistant hearts. Because there was no change in heart rate (data not shown), there was a significant decrease in stroke volume in this group (Fig. 3C). Compared to baseline, cardiac power decreased nonsignificantly for chow-fed rats during reperfusion (Fig. 3D). The decrease in cardiac power was much more pronounced for HSD-fed rats and reached 20% (P<0.001). As expected, MVO2 increased, while cardiac efficiency concomitantly decreased on reperfusion (Fig. 3E, F). Interestingly, although MVO2 increased less for HSD-fed rats, these hearts remained less efficient when compared to the control hearts.

Figure 3.

Impaired postischemic recovery of contractile function in the insulin-resistant heart. Fluidynamic parameters consisting of coronary flow (A), aortic flow (B), stroke volume (C), and cardiac power (D), as well as myocardial oxygen consumption (E) and cardiac efficiency (F), were measured in the isolated working hearts of chow-fed (solid squares with solid trace) and HSD-fed rats (open circles with dotted trace). Data represent means ± se of 20–24 animals/group at baseline and of 11–13 animals/group at reperfusion. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. chow; ###P < 0.001 vs. baseline.

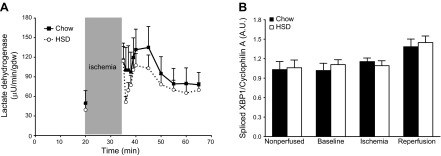

The release of lactate dehydrogenase in coronary effluent increased on reperfusion but did not differ between hearts of chow-fed and HSD-fed rats (Fig. 4A). There was also no difference in caspase 3 activity and protein carbonyl levels as measured from heart tissue extracts prepared post-reperfusion (data not shown). Last, the splicing of XBP1 mRNA was similar in both groups (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Changes in cellular toxicity and endoplasmic reticulum stress activity during the perfusion protocol. A) Lactate dehydrogenase activity was measured in the coronary effluent from chow-fed (solid squares with solid trace; n=7) and HSD-fed (open circles with dotted trace; n=8) rat hearts. B) The spliced isoform of XBP1 mRNA was quantified in nonperfused hearts from chow-fed (solid bars) and HSD-fed (open bars) rats (n=5–6) and in hearts perfused ex vivo for 20 min (baseline; n=5), subjected to 15 min of ischemia (n=5–6) and to 30 min of reperfusion (n=10). Data represent means ± se.

To summarize, in our model, contractile function recovers to preischemic levels in hearts from chow-fed rats, whereas contractile function is significantly decreased in hearts of HSD-fed rats. The decrease in cardiac work is not related to increased programmed cell death or necrosis, higher levels of oxidative stress, or increased cellular stress at the level of the endoplasmic reticulum. Lower rates of MVo2 suggest impairment in oxidative phosphorylation because they did not correlate with better cardiac efficiency.

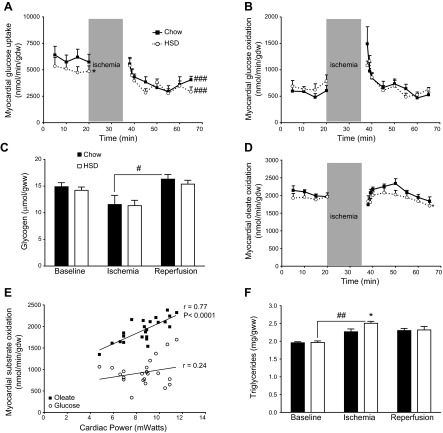

Myocardial glucose metabolism is indistinguishable between chow-fed and HSD-fed rats during reperfusion

In the perfused hearts, rates of glucose uptake at baseline were decreased by 17% for HSD-fed rats (Fig. 5A). The decrease in glucose uptake was independent from Akt activity, whose phosphorylation status at Thr308 and Ser473 evolved identically to chow-fed rats at each step of the protocol (Fig. 2A, B). During reperfusion, rates of glucose uptake decreased to similar lower levels for the hearts of chow-fed and HSD-fed rats (Fig. 5A). Rates of glucose oxidation were higher during the first minutes of reperfusion and then rapidly returned to preischemic levels, with no noticeable difference between the two groups (Fig. 5B). Myocardial glycogen content also followed the same pattern in the two groups, decreasing during ischemia and returning to preischemic levels during reperfusion (Fig. 5C). Thus, myocardial glucose metabolism in the reperfused hearts is not different between the chow-fed and the insulin-resistant rats.

Figure 5.

Normal glucose utilization but impaired oleate oxidation in the heart of rats fed a high-sucrose diet. A–B) Rates of glucose uptake (A; n=6–7) and rates of glucose oxidation (B; n=7–8) were measured in the isolated working hearts of chow-fed (solid squares with solid trace) and HSD-fed rats (open circles with dotted trace). Data represent means ± se. *P < 0.05 vs. chow, ###P < 0.001 vs. baseline. C) Glycogen levels were quantified in hearts of chow-fed (solid bars) and HSD-fed rats (open bars) perfused ex vivo for 20 min (baseline; n=5), after 15 min of ischemia (n=5) and after 30 min of reperfusion (n=12–13). Data represent means ± se. #P < 0.05. D) Rates of oleate oxidation were measured in isolated working hearts of chow-fed (solid squares with solid trace; n=5) and HSD-fed (open circles with dotted trace; n=5) rats. Data represent mean ± se. *P < 0.05 vs. chow. E) Rates of oleate oxidation (solid squares) and rates of glucose oxidation (open circles) measured during the early reperfusion of hearts from chow-fed and HSD-fed rats are plotted against their respective values of cardiac power. Values (n=23) include the measurements obtained between 35 and 40 min during the protocol for both groups. F) Triglyceride levels were quantified in chow-fed (solid bars) and in HSD-fed (open bars) rat hearts perfused ex vivo for 20 min (baseline; n=5), after 15 min of ischemia (n=5–6), and after 30 min of reperfusion (n=11–13). Data represent means ± se. *P < 0.05 vs. chow; ##P < 0.01.

Myocardial long-chain fatty acid oxidation is reduced for HSD-fed rats during reperfusion

Myocardial rates of oleate oxidation were not different at baseline (Fig. 5D). Between 35 and 40 min in the perfusion protocol (first 5 min of reperfusion), rates of oleate oxidation rapidly regained normal levels for both groups and, unlike glucose, were positively correlated to the recovery of cardiac power (Fig. 5E). Between 40 and 50 min in the perfusion protocol, myocardial rates of oleate oxidation kept increasing for chow-fed rats, reaching even higher levels than their average preischemic value (P<0.02). Interestingly, the hearts of chow-fed rats also accumulated less amounts of triglycerides than the hearts of HSD-fed animals during ischemia (Fig. 5F). Rates of oleate oxidation decreased steadily during the last 15 min of reperfusion, although they remained higher in the hearts of chow-fed rats (Fig. 5D).

At the molecular level, the phosphorylation of the AMPK at Thr172 was reduced in nonperfused hearts of HSD-fed rats (Fig. 6A). AMPK activity also trended lower during reperfusion, which was accompanied by a dramatic 35% reduction in the phosphorylation of its target ACC at Ser79 (Fig. 6B). In consistence with our previous study (10), the protein levels of UCP3, a mitochondrial anion carrier protein that has been proposed to increase the fatty acid oxidation capacity of myocytes (16, 17), were strikingly reduced in the hearts of HSD-fed rats (Fig. 6C). Protein levels of CPT1B were not altered, however, before or after the perfusion protocol (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Down-regulation in the activity or quantity of proteins critical for long-chain fatty acid oxidation in the insulin-resistant rat heart. Immunoblot analyses of AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172 (A), ACC phosphorylation at Ser79 (B), and UCP3 levels (C) were performed in nonperfused hearts of chow-fed (C; solid bars) and HSD-fed (S; open bars) rats and in isolated working hearts after 20 min perfusion (baseline), 15 min of ischemia, and 30 min of reperfusion. A representative sample for each condition is shown on the immunoblots. Data are means ± se of 5–6 animals/group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. chow; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001.

In summary, myocardial rates of oleate oxidation are impaired in the insulin-resistant heart on reperfusion. This reduced capacity to oxidize oleate may be specifically caused by the reduced mitochondrial uptake of long-chain fatty acids, either because of increased ACC-mediated inhibition of CPT1 activity and/or because of the down-regulation of UCP3.

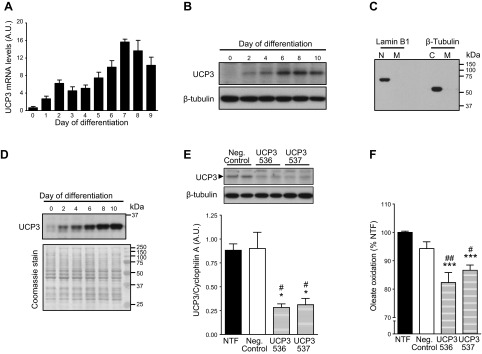

UCP3 knockdown impairs the restoration of oleate oxidation in L6 myocytes postischemia

Next, we used L6 rat myocytes to further investigate in vitro the potential role of UCP3 in the regulation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation following ischemia/reperfusion. Although not expressed in proliferating myoblasts, UCP3 levels increase gradually during myocyte differentiation (Fig. 7A, B). Cells were used after 8 d of differentiation, since at that time the expression of the protein reaches maximal levels in mitochondria (Fig. 7C, D). The siRNA-mediated knockdown of UCP3 led to a 60% reduction of protein levels in myocytes, which is comparable to the decrease observed in the heart of HSD-fed rats (Fig. 7E). Compared to nontransfected cells, oleate oxidation was decreased by 18 and 13% after myocytes with reduced UCP3 levels were subjected to 15 min of ischemia (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7.

Impaired oleate oxidation in postischemic myocytes following UCP3 knockdown. A) UCP3 transcript levels were quantified in differentiating L6 myoblasts. Data are means ± se of 4 experiments. B) UCP3 protein levels from whole-cell lysates were determined for differentiating L6 myoblasts. C) Mitochondrial fractions (M) prepared from L6 cells by differential centrifugation were free from nuclear (N) or cytosolic (C) proteins. D) UCP3 content increased in the mitochondrial fraction until d 8 of differentiation. Coomassie stain of the membrane is shown as a loading control. E) UCP3 transcript and protein levels were quantified in d 8 differentiated, nontransfected (NTF) myocytes (solid bar), and in myocytes transfected with a nontargeting siRNA sequence (neg. control; open bar) or 1 of 2 distinct siRNA sequences targeting UCP3 (536 and 537; hatched bars). Data are means ± se of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. NTF, #P < 0.05 vs. neg. control. F) Nontransfected (NTF) and transfected myocytes were subjected to 15 min ischemia, and oleate oxidation was then determined over 1 h of reperfusion. Data are means ± se of 4 experiments. ***P < 0.001 vs. NTF; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. neg. control.

Food withdrawal in vivo or octanoate ex vivo increases rates of fatty acid oxidation and improves contractile function in insulin-resistant postischemic hearts

We then subjected the hearts of HSD-fed rats to different perfusion conditions in order to further investigate whether the impaired capacity to oxidize the long-chain fatty acid oleate may result from lower UCP3 levels and whether this may cause the decreased recovery in contractile function. Our first strategy consisted in replacing oleate in the perfusate by a medium-chain fatty acid in order to bypass the need for the mitochondrial l-carnitine shuttle pathway (18, 19). In another experiment, HSD-fed rats were denied access to food for 24 h prior to ex vivo perfusion of the hearts with oleate in order to induce UCP3 expression levels (20).

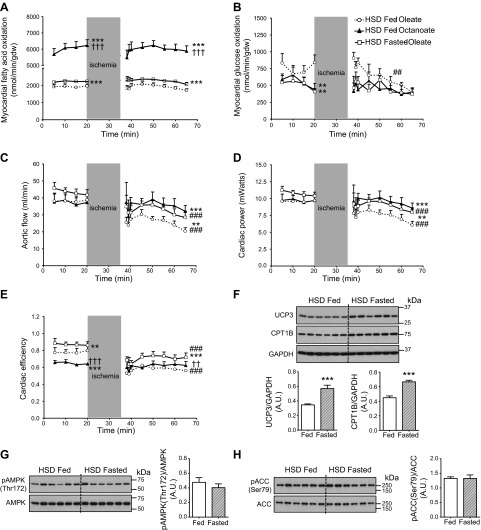

Perfused hearts of HSD-fed rats readily oxidized the medium-chain fatty acid octanoate, and food withdrawal succeeded in enhancing myocardial rates of oleate oxidation before and after ischemia (Fig. 8A). Both strategies also resulted in a stronger suppression of glucose oxidation (Fig. 8B). This switch in myocardial metabolism was accompanied by an increase in aortic flow and improved recovery of cardiac power on reperfusion (Fig. 8C, D). Interestingly, unfed-state animals also displayed better cardiac efficiency (Fig. 8E). An immunoblot analysis of cardiac tissue extracted at the end of reperfusion confirmed that 24 h of food withdrawal increased UCP3 protein levels by 67%, and CPT1B levels increased similarly by 51% (Fig. 8F). Most notably, the increased capacity to oxidize oleate after a period of food withdrawal was independent from any change in AMPK and ACC phosphorylation status (Fig. 8G, H).

Figure 8.

Improved contractile recovery of the insulin-resistant rat heart is linked to increased fatty acid oxidation. A–E) Rates of glucose oxidation (A) and fatty acid oxidation (B), aortic flow (C), cardiac power (D), and cardiac efficiency (E) were determined for the isolated working hearts of HSD-fed rats perfused with 25 mM glucose, 5 ng/ml insulin, and 0.8 mM oleate (open circles with dotted trace) or octanoate (solid triangles with solid trace) as the fatty acid. Perfusions with oleate as the fatty acid were also performed on hearts from HSD-fed rats that were denied access to food (“fasted ”) 24 h before the beginning of the experiment (open squares with solid trace). Data represent means ± se of 5–6 animals/group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. hearts of fed rats perfused with oleate; ††P < 0.01, †††P < 0.001 vs. hearts of “fasted” rats perfused with oleate; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. baseline. F–H) At the end of reperfusion, immunoblot analyses of UCP3 and CPT1B levels (F), AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172 (G), and ACC phosphorylation at Ser79 (H) were performed for the hearts of HSD fed (open bars) and HSD “fasted ” rats (hatched bars) perfused with oleate. Data are means ± se of 6 animals/group. ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that myocardial insulin resistance is associated with impaired recovery of contractile function following total global ischemia. In our model, impaired cardiac function is due to an energetic deficit linked to a failure to increase and to sustain long-chain fatty acid utilization on reperfusion. Rescue strategies applied to hearts perfused ex vivo suggest that the limited capacity for long-chain fatty acid oxidation is caused specifically by the decreased transport of this substrate into the mitochondria. Last, the siRNA-mediated knockdown of UCP3 in L6 myocytes supports a preponderant role for the mitochondrial protein in the reestablishment of long-chain fatty acid utilization following ischemia.

The impairment of insulin-mediated myocardial glucose uptake is a hallmark of patients with type 2 diabetes and a proposed prognostic factor for cardiac maladaptation to environmental stress (21, 22). Interestingly, the decrease in insulin-mediated glucose uptake is associated with increased basal signaling to Akt and to its downstream targets (9, 23). The hearts of rats fed HSD display the same features and therefore constitute a valuable model to study the effects of myocardial insulin resistance in a physiological setting. We previously reported that the insulin-resistant heart adapts better to acute metabolic and hemodynamic stress when compared to the heart of chow-fed animals (10). In contrast, the present data reveal severe maladaptation to a brief period of total global ischemia when hearts are perfused in the same metabolic milieu. How can this discrepancy be explained?

While the hemodynamically stressed heart faces increased energy needs by increasing the proportion of glucose oxidized, it is well known that fatty acid oxidation provides most of the heart's energy requirements after a transient period of global ischemia (24). Accordingly, the rapid down-regulation of glucose uptake in both normal and insulin-resistant hearts at reperfusion likely results from an increase in intracellular fatty acid intermediates (25). Rates of glucose oxidation were nonetheless maintained at the preischemic level, which may be explained by the high concentrations of glucose and insulin used in the perfusion buffer. The impairment of contractile recovery through failure to increase oleate oxidation is supported by two key observations. First, the recovery of function that followed myocardial stunning was highly correlated to the rates of oleate oxidation. Second, the aortic flow and cardiac power were greatly improved by food withdrawal or ex vivo perfusion with octanoate, 2 strategies which increased fatty acid oxidation but further inhibited glucose oxidation. In addition, the utilization of octanoate instead of oleate as the fatty acid confirmed that the reduction in cardiac recovery stems from a deficit in energy provision and can be corrected when bypassing the CPT shuttle.

We identified two potential mechanisms for the impairment of oleate entry into the mitochondria: a decrease in AMPK activity and a reduction in UCP3 protein levels. In nonperfused hearts, increased basal Akt activity may be responsible for the decrease in AMPK phosphorylation at Thr172 (26). It is less clear why AMPK activity would be reduced after reperfusion, since Akt and its direct downstream targets were normally phosphorylated during the perfusion protocol. Nonetheless, the dramatic decrease in AMPK-mediated phosphorylation of ACC suggests that CPT1 activity is likely to be reduced through increased intracellular malonyl-CoA levels. The decrease of UCP3 protein levels in the heart of HSD-fed rats is consistent with our previous report (10). While the physiological function of UCP3 is still debated, it has become apparent that the mitochondrial protein can regulate fatty acid oxidation (27). Interestingly, the expression of UCP3 in rat cardiomyocytes is specifically activated by long-chain fatty acids, and particularly by oleate (28).

A stimulatory effect of UCP3 on fatty acid oxidation was demonstrated when MacLellan et al. (17) overexpressed the protein in L6 myocytes; the 2.5-fold increase in UCP3 levels resulted in a 68% increase in palmitate oxidation when the cells were incubated with physiological concentrations of glucose. However, additional studies suggest that UCP3 is not a necessary component of the fatty acid oxidation machinery per se but rather promotes fatty acid oxidation as an adaptation to a perturbed cellular energy balance (29, 30). This may explain why the loss of the UCP3 gene is associated with impaired palmitate oxidation in the heart of obese diabetic ob/ob mice, but has not such an effect in wild-type high-fat-fed mice (31). Himms-Hagen and Harper (32) proposed that UCP3 may work as a fatty acid anion carrier to provide an overflow pathway in order to avoid the accumulation of fatty acids in the matrix, and thereby sustain higher rates of fatty acid oxidation by maintaining the pool of free CoASH necessary for subsequent metabolic reactions. In our experiment, the intramitochondrial accumulation of fatty acids may have been promoted by ischemia. The food withdrawal experiment revealed that the recovery of contractile function is in fact mostly independent from AMPK activity. We cannot exclude with food withdrawal the involvement of molecular mechanisms other than the up-regulation of UCP3 levels, since CPT1B expression was also induced. However, the knockdown of UCP3 in myocytes demonstrates that decreasing mitochondrial UCP3 content is sufficient to impair oleate oxidation following ischemia. In accordance with our findings, a very recent study reported that UCP3−/− mice present lower myocardial ATP content following ischemia and reduced functional recovery during reperfusion (33).

Last, it is noteworthy that cardiac efficiency was reduced despite lower UCP3 levels, and that food withdrawal improved efficiency despite the dramatic increase in UCP3 expression. It is indeed believed that the decrease in cardiac efficiency that accompanies diabetes is linked to increased UCP3 expression. This hypothesis has been supported by reports of increased cardiac UCP3 transcript and protein levels in diabetic rodents (34–38). However, most of these reports focused on animal models of type 1 diabetes and therefore overlooked the effect of hyperinsulinemia on the heart. Moreover, UCP3 transcript levels are often inconsistent with the protein data (10, 39). In support of our observation, Schrauwen et al. (39) reported a 50% lower UCP3 protein content in skeletal muscle from patients with type 2 diabetes. Further experiments are clearly necessary to determine the effect of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes on myocardial UCP3 content.

In summary, we propose that the metabolic flexibility of the insulin-resistant heart of HSD-fed rats is altered in a way that enhances its capacity to increase glucose oxidation with increased hemodynamic stress, but impairs its ability to promote long-chain fatty acid oxidation following ischemia. We postulate that this selective adaptability to various stress conditions is linked to the down-regulation of UCP3. This hypothesis is supported by our previous finding that an acute increase in workload in vivo decreases UCP3 expression in rat heart (20). Taken together, our results have identified a novel target by which myocardial metabolism may be manipulated to improve function of the insulin-resistant heart.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Roxy Tate for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01-HL-061483 to H.T. The Mouse Metabolism Core at the Baylor College of Medicine Diabetes Research Center (Houston, TX, USA) is supported by NIH grant P30 DK-079638.

Footnotes

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- CPT1

- carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1

- GSK3-β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3 β

- HSD

- high sucrose diet

- MVo2

- myocardial oxygen consumption

- TSC2

- tuberous sclerosis complex 2

- UCP3

- uncoupling protein 3

- XBP1

- X-box binding protein 1

REFERENCES

- 1. Almdal T., Scharling H., Jensen J. S., Vestergaard H. (2004) The independent effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on ischemic heart disease, stroke, and death: a population-based study of 13,000 men and women with 20 years of follow-up. Arch. Intern. Med. 164, 1422–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adel W., Nammas W. (2010) Predictors of contractile recovery after revascularization in patients with anterior myocardial infarction who received thrombolysis. Int. J. Angiol. 19, e78–e82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harjai K. J., Stone G. W., Boura J., Mattos L., Chandra H., Cox D., Grines L., O'Neill W., Grines C. (2003) Comparison of outcomes of diabetic and nondiabetic patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 91, 1041–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marso S. P., Miller T., Rutherford B. D., Gibbons R. J., Qureshi M., Kalynych A., Turco M., Schultheiss H. P., Mehran R., Krucoff M. W., Lansky A. J., Stone G. W. (2007) Comparison of myocardial reperfusion in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction with versus without diabetes mellitus (from the EMERALD Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 100, 206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mak K. H., Topol E. J. (2000) Emerging concepts in the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 35, 563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boudina S., Abel E. D. (2007) Diabetic cardiomyopathy revisited. Circulation 115, 3213–3223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stanley W. C., Lopaschuk G. D., McCormack J. G. (1997) Regulation of energy substrate metabolism in the diabetic heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 34, 25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sena S., Hu P., Zhang D., Wang X., Wayment B., Olsen C., Avelar E., Abel E. D., Litwin S. E. (2009) Impaired insulin signaling accelerates cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction after myocardial infarction. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 910–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cook S. A., Varela-Carver A., Mongillo M., Kleinert C., Khan M. T., Leccisotti L., Strickland N., Matsui T., Das S., Rosenzweig A., Punjabi P., Camici P. G. (2010) Abnormal myocardial insulin signalling in type 2 diabetes and left-ventricular dysfunction. Eur. Heart J. 31, 100–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harmancey R., Lam T. N., Lubrano G. M., Guthrie P. H., Vela D., Taegtmeyer H. (2012) Insulin resistance improves metabolic and contractile efficiency in stressed rat heart. FASEB J. 26, 3118–3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taegtmeyer H., Hems R., Krebs H. A. (1980) Utilization of energy-providing substrates in the isolated working rat heart. Biochem. J. 186, 701–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goodwin G. W., Ahmad F., Doenst T., Taegtmeyer H. (1998) Energy provision from glycogen, glucose, and fatty acids on adrenergic stimulation of isolated working rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 274, H1239–H1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hirota M., Kitagaki M., Itagaki H., Aiba S. (2006) Quantitative measurement of spliced XBP1 mRNA as an indicator of endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Toxicol. Sci. 31, 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harmancey R., Wilson C. R., Wright N. R., Taegtmeyer H. (2010) Western diet changes cardiac acyl-CoA composition in obese rats: a potential role for hepatic lipogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 51, 1380–1393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meldrum K. K., Meldrum D. R., Hile K. L., Burnett A. L., Harken A. H. (2001) A novel model of ischemia in renal tubular cells which closely parallels in vivo injury. J. Surg. Res. 99, 288–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bezaire V., Spriet L. L., Campbell S., Sabet N., Gerrits M., Bonen A., Harper M. E. (2005) Constitutive UCP3 overexpression at physiological levels increases mouse skeletal muscle capacity for fatty acid transport and oxidation. FASEB J. 19, 977–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. MacLellan J. D., Gerrits M. F., Gowing A., Smith P. J., Wheeler M. B., Harper M. E. (2005) Physiological increases in uncoupling protein 3 augment fatty acid oxidation and decrease reactive oxygen species production without uncoupling respiration in muscle cells. Diabetes 54, 2343–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Longnus S. L., Wambolt R. B., Barr R. L., Lopaschuk G. D., Allard M. F. (2001) Regulation of myocardial fatty acid oxidation by substrate supply. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 281, H1561–H1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrow R. J., Neely M. L., Paradise R. R. (1973) Functional utilization of palmitate, octanoate, and glucose by the isolated rat heart. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 142, 223–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Young M. E., Patil S., Ying J., Depre C., Ahuja H. S., Shipley G. L., Stepkowski S. M., Davies P. J., Taegtmeyer H. (2001) Uncoupling protein 3 transcription is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (alpha) in the adult rodent heart. FASEB J. 15, 833–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Iozzo P., Chareonthaitawee P., Dutka D., Betteridge D. J., Ferrannini E., Camici P. G. (2002) Independent association of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease with myocardial insulin resistance. Diabetes 51, 3020–3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Witteles R. M., Fowler M. B. (2008) Insulin-resistant cardiomyopathy clinical evidence, mechanisms, and treatment options. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhu Y., Pereira R. O., O'Neill B. T., Riehle C., Ilkun O., Wende A. R., Rawlings T. A., Zhang Y. C., Zhang Q., Klip A., Shiojima I., Walsh K., Abel E. D. (2013) Cardiac PI3K-Akt impairs insulin-stimulated glucose uptake independent of mTORC1 and GLUT4 translocation. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 172–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saddik M., Lopaschuk G. D. (1992) Myocardial triglyceride turnover during reperfusion of isolated rat hearts subjected to a transient period of global ischemia. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3825–3831 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hue L., Taegtmeyer H. (2009) The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297, E578–E591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hahn-Windgassen A., Nogueira V., Chen C. C., Skeen J. E., Sonenberg N., Hay N. (2005) Akt activates the mammalian target of rapamycin by regulating cellular ATP level and AMPK activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32081–32089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bezaire V., Seifert E. L., Harper M. E. (2007) Uncoupling protein-3: clues in an ongoing mitochondrial mystery. FASEB J. 21, 312–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lockridge J. B., Sailors M. L., Durgan D. J., Egbejimi O., Jeong W. J., Bray M. S., Stanley W. C., Young M. E. (2008) Bioinformatic profiling of the transcriptional response of adult rat cardiomyocytes to distinct fatty acids. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1395–1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samec S., Seydoux J., Dulloo A. G. (1998) Role of UCP homologues in skeletal muscles and brown adipose tissue: mediators of thermogenesis or regulators of lipids as fuel substrate? FASEB J. 12, 715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seifert E. L., Bezaire V., Estey C., Harper M. E. (2008) Essential role for uncoupling protein-3 in mitochondrial adaptation to fasting but not in fatty acid oxidation or fatty acid anion export. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25124–25131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boudina S., Han Y. H., Pei S., Tidwell T. J., Henrie B., Tuinei J., Olsen C., Sena S., Abel E. D. (2012) UCP3 regulates cardiac efficiency and mitochondrial coupling in high fat-fed mice but not in leptin-deficient mice. Diabetes 61, 3260–3269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Himms-Hagen J., Harper M. E. (2001) Physiological role of UCP3 may be export of fatty acids from mitochondria when fatty acid oxidation predominates: an hypothesis. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 226, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ozcan C., Palmeri M., Horvath T. L., Russell K. S., Russell R. R., 3rd (2013) Role of uncoupling protein 3 in ischemia-reperfusion injury, arrhythmias, and preconditioning. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304, H1192–H1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arikawa E., Ma R. C., Isshiki K., Luptak I., He Z., Yasuda Y., Maeno Y., Patti M. E., Weir G. C., Harris R. A., Zammit V. A., Tian R., King G. L. (2007) Effects of insulin replacements, inhibitors of angiotensin, and PKCbeta's actions to normalize cardiac gene expression and fuel metabolism in diabetic rats. Diabetes 56, 1410–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bugger H., Boudina S., Hu X. X., Tuinei J., Zaha V. G., Theobald H. A., Yun U. J., McQueen A. P., Wayment B., Litwin S. E., Abel E. D. (2008) Type 1 diabetic akita mouse hearts are insulin sensitive but manifest structurally abnormal mitochondria that remain coupled despite increased uncoupling protein 3. Diabetes 57, 2924–2932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerber L. K., Aronow B. J., Matlib M. A. (2006) Activation of a novel long-chain free fatty acid generation and export system in mitochondria of diabetic rat hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C1198–C1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hidaka S., Kakuma T., Yoshimatsu H., Sakino H., Fukuchi S., Sakata T. (1999) Streptozotocin treatment upregulates uncoupling protein 3 expression in the rat heart. Diabetes 48, 430–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murray A. J., Panagia M., Hauton D., Gibbons G. F., Clarke K. (2005) Plasma free fatty acids and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in the control of myocardial uncoupling protein levels. Diabetes 54, 3496–3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schrauwen P., Hesselink M. K., Blaak E. E., Borghouts L. B., Schaart G., Saris W. H., Keizer H. A. (2001) Uncoupling protein 3 content is decreased in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 50, 2870–2873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]