Abstract

Migration and geographic mobility increase risk for HIV infection and may influence engagement in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Our goal is to use the migration-linked communities of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and New York City, New York, to determine the impact of geographic mobility on HIV care engagement and adherence to treatment. In-depth interviews were conducted with HIV+Dominicans receiving antiretroviral therapy, reporting travel or migration in the past 6 months and key informants (n=45). Mobility maps, visual representations of individual migration histories, including lifetime residence(s) and all trips over the past 2 years, were generated for all HIV+ Dominicans. Data from interviews and field observation were iteratively reviewed for themes. Mobility mapping revealed five distinct mobility patterns: travel for care, work-related travel, transnational travel (nuclear family at both sites), frequent long-stay travel, and vacation. Mobility patterns, including distance, duration, and complexity, varied by motivation for travel. There were two dominant barriers to care. First, a fear of HIV-related stigma at the destination led to delays seeking care and poor adherence. Second, longer trips led to treatment interruptions due to limited medication supply (30-day maximum dictated by programs or insurers). There was a notable discordance between what patients and providers perceived as mobility-induced barriers to care and the most common barriers found in the analysis. Interventions to improve HIV care for mobile populations should consider motivation for travel and address structural barriers to engagement in care and adherence.

Introduction

For those living with chronic illness, such as HIV, geographic mobility complicates engagement with care and adherence to treatment. The rise in global population mobility means that barriers to health care for mobile populations impact more people each year. One million people travel internationally each day,1 and international migrants accounted for 10% of the total population in developed regions in 2010.2 Geographic mobility, including travel, migration, and emigration, is associated with poor health outcomes,3 and highly mobile people are more at risk for acquiring and living with poorly controlled HIV/AIDS.4–11 Studies show that immigrants are less likely to be tested for HIV and more likely to present for care with advanced disease.12–14 An HIV diagnosis can contribute to greater mobility as HIV-infected (HIV+) individuals move to seek care and away from stigma.15–20 Examination of the HIV care cascade reveals that migration also adversely impacts maintenance in HIV care14,21 and researchers' ability to quantify stages in the cascade.22–24

Geographic mobility is also associated with patterns of accessing and receiving HIV care. The distance a patient travels to receive care negatively affects adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and overall engagement in HIV care.25–27 Nondisclosure of one's HIV status to others, especially while traveling, may undermine adherence, particularly when immigrants visit to their country of origin.25,28 Conversely, geographic mobility can have a positive impact. Some individuals will move toward HIV treatment sites or support networks and away from stigma.15,29,30

The impact of geographic mobility on HIV treatment outcomes receives less attention in the biomedical literature than the impact of other structural factors: poverty, gender inequality, stigma, or food insecurity, and a recent review calls for population-specific needs assessment within mobile populations.27,31–33 Little is known regarding patterns of mobility in individuals on ART, or how mobility affects engagement with HIV care and treatment adherence. A limitation of existing work is that mobility is assessed as a quantitative, often binary, variable, without accounting for distance traveled, duration of travel, circular migration, or the impact of trip motivation or planning.

To address the knowledge gap regarding the impact of geographic mobility for HIV+ individuals on antiretroviral therapy, we conducted ethnographic research in two highly mobile, linked populations: people living with HIV/AIDS receiving ART in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (DR), and Washington Heights, a Dominican-dominant neighborhood of New York City, New York. First, we seek to define patterns of geographic mobility broadly, including frequency, location, and motivation for travel. Second, we determine how mobility impacts two HIV care outcomes, including engagement in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy.

Methods

Study design

The “twin cities” approach originally endorsed by the International Organization for Migration and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/ AIDS (UNAIDS) suggests examining health outcomes at the origin and destination of migration for the study of mobile populations with HIV.34 We adapted this strategy to the communities of New York City (NYC) and Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, which are linked by permanent and circular migration. We conducted an ethnographic study, collecting data via in-depth semi-structured interviews and observation over 3 years (2010–2012) in NYC and the DR. Clinical study sites were an inner-city HIV clinic serving approximately 2000 HIV+ individuals in a Dominican-dominant neighborhood in northern Manhattan, NYC, and two nongovernmental organization-led HIV clinics serving 1500 people in Santo Domingo, DR. Observation occurred within the surrounding communities of Santo Domingo and NYC. The study included two groups: geographically mobile, HIV+ Dominican patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) and key informants working closely with mobile populations or with people living with HIV.

To select individuals with insight into geographic mobility, we included HIV+ patient participants at least 21 years of age who self-identified as Dominican. All participants had received ART continuously for ≥6 months and had ≥1 “travel event” within 6 months. A travel event was defined as spending ≥3 nights at a location ≥50 kilometers from the participant's home. Target sample size was 15–20 patient participants per site. Provider surveys identified potential participants in the clinics, and structured sampling was used to recruit equal numbers of men and women, and those with difficulties with adherence to ART and those without. Key informants were adults ≥21 years of age from either NYC or the DR with knowledge relevant to the organization of clinical services and support for migrants, including physicians, social workers, peer educators, and staff of nongovernmental organizations.

Data collection

In-depth interviews

Interviews lasted 1–3 h, and used an interview guide that was iteratively revised throughout the investigation. Patient interviews covered: the nature of the travel event(s); characteristics of the destination and activities while traveling; perceptions of how travel impacts medical care; other barriers to engagement in care that occur outside of travel events; and intervention suggestions. Topics for key informant interviews included: reasons for travel and preparations made for the trips; the impact of mobility on antiretroviral adherence and engagement in care (e.g., seeking a provider when needed or attending regularly scheduled follow-up appointments); specific examples of failures and successes in ART adherence and engagement in care; perceptions of travel frequency within their peer community; and suggestions regarding how to address perceived problems with adherence or engagement in care for travelers. Audio from each interview was recorded and later transcribed. Participants were recruited and interviewed until the investigators determined that data saturation for themes had been reached.

Mobility mapping

Patient participants developed a “mobility map” in collaboration with the interviewer. They created a diagram of the participant's place of birth and all places of residence in sequence. Participants then described in detail all trips since starting ART, or within the past 2 years, whichever was shorter, including: location, frequency, duration, motivation, whether the trip was anticipated, and changes in travel plans or duration. These trips were superimposed onto the residence diagram.

Field observation

Over the study period, investigators conducted 11 site visits to familiarize themselves with HIV care delivery models in the clinics, organizations offering services to migrants and to people living with HIV, and other community-level support networks. Notes were taken regarding each site. Data from local and national print, digital, and broadcast media on perceptions of migrants and people living with HIV were gathered.

Data analysis

Thematic review and assessment of dominant motivation for mobility

Audio recordings and transcripts of interviews and field notes were reviewed to extract descriptive information related to individual histories of illness and mobility, barriers to and promoters of antiretroviral adherence, and other factors relevant to engagement in HIV treatment. Subsequent iterative reviews of patient interviews generated descriptive categories for the dominant motivation for mobility for each patient. Quotations were extracted from the interview transcripts. Only trips ≥50 km were included for further analysis, as the review revealed that shorter trips could occur in less than 12 h at both sites and did not represent overnight stays.

Development of composite mobility map by travel motivation

Data from the interviews and mobility maps were parsed to form a mobility dataset. The origin, destination, and duration of each trip were collated from mobility maps. Travel origins/destinations within the same province in the DR were grouped. Distance for overland trips was determined by shortest driving route from origin to destination (Google Maps) and for overseas trips using great circle distance formula (http://dateandtime.info).35 The aggregated mobility dataset was then visualized as a composite mobility map using network analysis software (Cytoscape 3x). Origin and destination were rendered as nodes, and individual trips by edges (lines between nodes). Nodes were positioned by their relative geography and sized according to their degree (number of connecting edges). Each edge's width was proportional to the frequency of its respective trip. To evaluate differences in mobility patterns, categories of dominant motivation for travel were superimposed onto their respective edges by varying their color.

Assessing barriers and promoters of engagement in care and adherence

Barriers and promoters of engagement in HIV care and treatment adherence were identified from the interviews and field observations, and were named, described, and classified as mobility-associated or not, using direct quotations from the interviews. These barriers/promoters were then categorized by level of influence (individual, inter-personal/social, health-systems based, or other institutional/political), noting perceptual differences between patient and key informant interviews. The intersection between mobility pattern and barriers to care was examined.

Ethical approvals

This research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Columbia University Medical Center, the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio, the Instituto Dermatológico y Cirugía De Piel “Dr. Huberto Bogaert Díaz”, Profamilia (Asociación Dominicana Pro-Bienestar de la Familia), and the Dominican National Government (Consejo Nacional de Bioética de Salud).

Results

Patient participants included 10 women and 9 men in NYC, and 10 women and 7 men in the DR; all participants were born in the DR. One woman from NYC was excluded after transcript review because she did not meet inclusion criteria of travel while receiving ART. Key informants included: five physicians providing HIV care, one social worker, two adherence counselors, and one director of a non-governmental organization providing services for migrants (Table 1). No participants declined enrollment and all completed the interview process.

Table 1.

Description of Data Sources

| Type | Site | Number of participants | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient participants | New York City | 18a | 9 women, 9 men; 50% with known adherence issues per providers |

| Santo Domingo | 17 | 10 women, 7 men; 47% with known adherence issues per providers | |

| Key informants | New York City | 3 | 1 physician, 1 social worker, 1 adherence counselor |

| Santo Domingo | 6 | 4 physicians, 1 adherence counselor, 1 director of a non-governmental organization providing services for migrants | |

| Field observation | New York City | – | Both sites: Agencies offering services for migrants, specifically Dominicans (site visits); interactions between HIV care providers and patients (direct observation); health care establishment and community perceptions of people living with HIV and migrants (informal interviews, observation, print, audio and visual media) |

| Santo Domingo and surrounding areas, DR | – |

Initial sample was 19, but one participant was excluded after the interview took place because she did not meet inclusion criteria of travel while receiving antiretroviral therapy.

Developing a taxonomy of mobility patterns

The mobility taxonomy was generated after iterative review of the interview transcripts and revealed five categories of motivations for travel: (1) travel for care (n=7): monthly travel of ≥3 nights to receive medical attention; (2) work-related travel (n=7): travel of ≥3 nights for work by salespeople, bus drivers; (3) transnational (n=7): recurrent circular migration of individuals with homes and immediate family (spouses, children) in both locations; (4) frequent long-stay travel (n=10): travel 1–2 times yearly for ≥30 days to fulfill obligations to family or friends; and (5) vacation (n=4): sporadic, short trips of <1 month for leisure, not to visit family. Transnationality, defined as the ties and interactions that link people and their institutions across the borders of nation-states,36 incorporates the concept of circular migration, where immigrants remain tied to their home community and make frequent trips or extended stays at both sending and receiving sites.37

From 35 patient participant mobility maps, 529 trips ≥50 km on ART in the past 2 years were recorded, ranging from 1 trip per participant to 85 trips for one chauffeur in the DR. International travel all occurred by air, and travel within the DR and in the NYC area was by bus, subway, taxi, or private car.

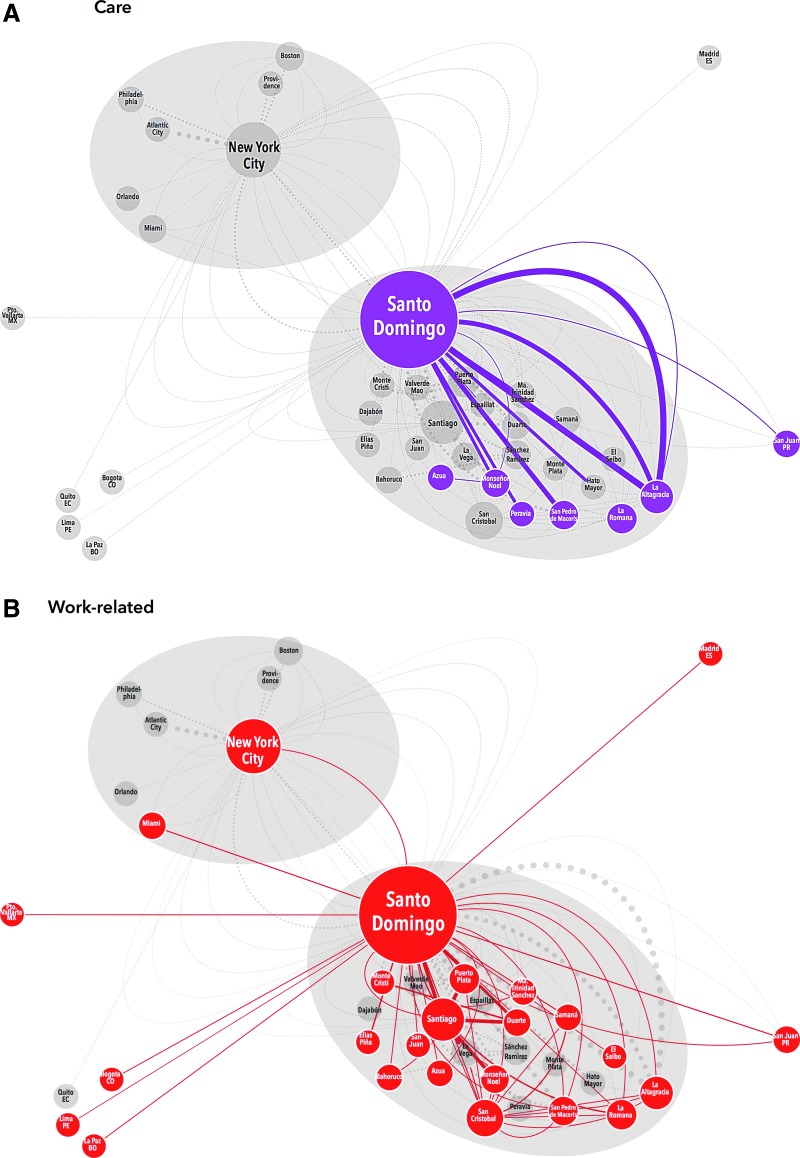

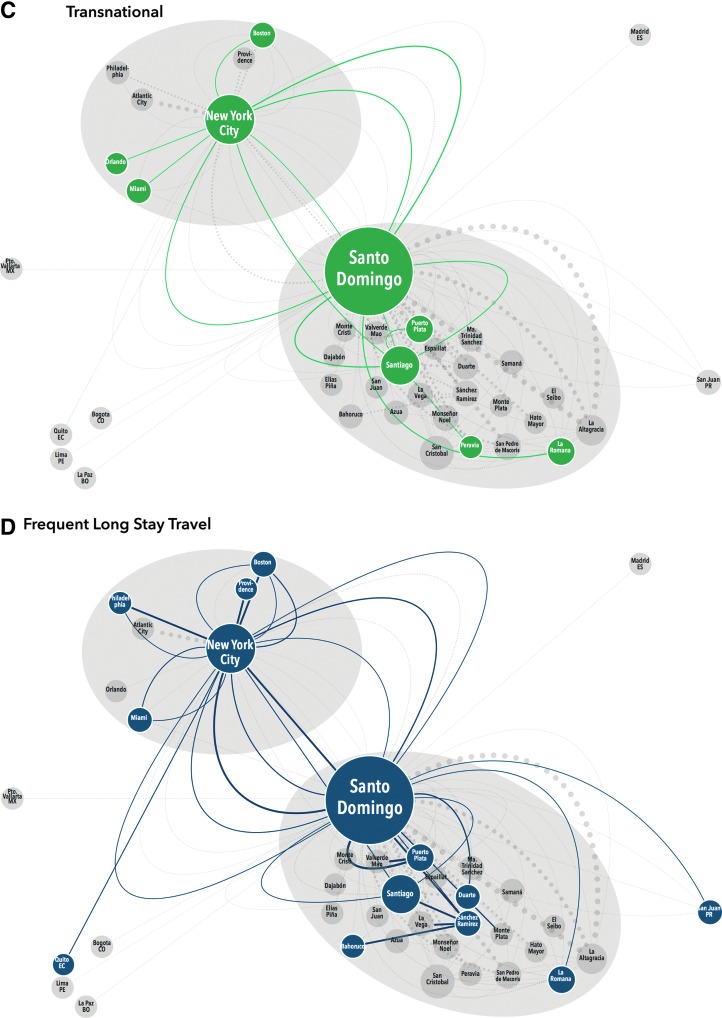

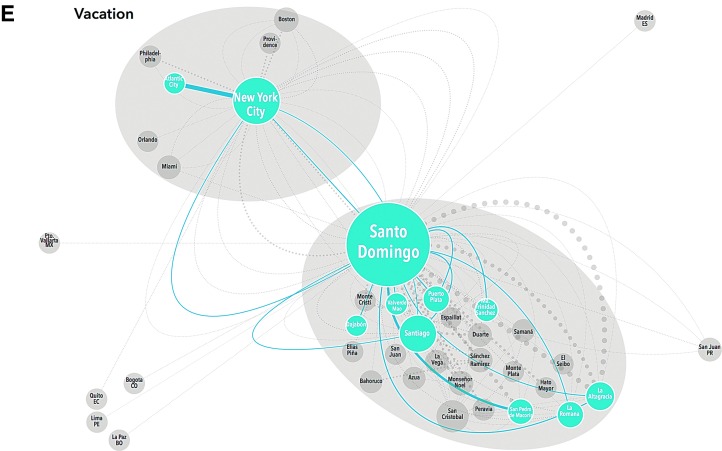

Close examination of these maps demonstrates clear variation in mobility pattern by dominant motivation for travel. Those traveling to clinic for care demonstrate relatively simple, recurrent mobility within the DR; no NYC participants reported significant travel (≥3 nights) for HIV treatment (Fig. 1A). Participants traveling for work were also all DR-based and showed a similar pattern to those traveling for care with multiple recurrent trips along a set route. However, these participants were also internationally mobile with trips to Spain and North and South America (Fig. 1B). Transnational participants all received care in NYC and had less recurrent travel, but their trips lasted longer (30–120 days). Transnationals clearly demonstrated the NYC/DR “airbridge”, with multiple trips between NYC and Santo Domingo, as well as movement around the DR and the US, but not to any other regions (Fig. 1C). Frequent long-stay travelers also demonstrated the airbridge, but had more recurrent trips, and more regional mobility within both the US and the DR than the transnationals (Fig. 1D). Some vacation travelers also followed the airbridge pattern, traveling from NYC to large cities in the DR (Santo Domingo or Santiago), but not to smaller locations. Others were DR-based and took recurrent leisure trips within the DR (Fig. 1E).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of migration taxonomy. Each participants' travel history (origin, destination, frequency, duration, and motivation) was extracted from mobility maps and interviews. This schematic representation includes 529 trips occurring within the last 2 years of ≥50 km after starting antiretroviral therapy, stratified by dominant motivation for travel. Travel origins/destinations within the same province are amalgamated. Each node (circle) represents a location that is either the origin or destination of a trip; each edge (line) represents a trip which met the inclusion criteria. The size of each node is proportional to the number of trips of which it was an origin/destination; the width of each edge is proportional to the frequency of the trip within the last 2 years while on antiretroviral therapy. Migration patterns are grouped by the participants' dominant motivation for travel and labeled by color, trips not in that travel motivation group appear on the map in light gray for contrast. Travel for care (A, purple) is only observed for DR-based participants and consists of travel between more rural areas and Santo Domingo. Work-related travel (B, red) shows a more complex pattern of movement within the DR and internationally. (Color image can be found at www.liebertonline.com/apc). Transnationals (C, green) and frequent long stay travelers (D, dark blue) demonstrate the NYC–DR air bridge, but long-stay travelers have more recurrent trips and regional mobility. (Color image can be found at www.liebertonline.com/apc). Vacation travelers (E, light blue) are based in both sites and took recurrent trips. (Color image can be found at www.liebertonline.com/apc).

Mobility-related barriers to and promoters of engagement in HIV care and adherence

Geographic mobility was rarely noted to facilitate engagement with HIV care or adherence. Some patient participants in the DR believed that travel for care was beneficial. They felt care at the destination was superior and that traveling to the capital for care enabled them to escape disclosure of their diagnosis in their smaller hometowns. More frequently, both patients and clinicians saw travel for care as a barrier to optimal engagement. Patient participants reported difficulty paying for transportation to clinics, and key informants in the DR noted that patients living in distant towns experienced treatment interruptions because they missed prescription refill pickups. Mobility-related barriers to care were classified into levels of influence: individual, societal, health systems-based, and travel-related institution based (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mobility-Linked Barriers to Adherence and Engagement in HIV Care By Level of Influence with Illustrative Quotations from Interviews

| Level of influence | Barriers | Impact of barrier | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | |||

| • Changes in daily schedule with travel [PI, KI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Forgetting medications due to travel-induced schedule changes | ||

| ➢ Lack of water/food with travel led to delayed medication doses | |||

| • View vacation travel as a vacation from medications as well [PI; NYC] | ➢ Treatment interruption for duration of trip. | “I don't travel with medicines…I'm telling you the truth…I stop them for that month and I don't take any…Because I can't take them over there. No, I don't know what happens that I can't take them over there. | |

| • Fear of experiencing medication side effects during travel [PI; NYC] | ➢ Delays in ART initiation or treatment interruption for duration of trip | ||

| Societal | |||

| • Fear of stigma and resultant lack of disclosure to those at destination [PI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Hiding medication or placing it in other pill bottles could lead to forgetting doses or medication schedule | “There I'd never do it because, you know, small town, big trouble.” (Spanish idiom: “pueblo chiquito, infierno grande.”) | |

| • Fear of stigma/discovery of diagnosis when receiving care from a treatment site close to home [PI, KI; DR] | ➢ Long distance travel to seek medical care leading to inability to walk in for illness and difficulty getting refills. | “It's that you don't know the mentality that they have in that town. It is not the same as coming here to the capital, nobody knows me here.” | |

| • Fear of inadvertent disclosure to strangers during travel [PI; DR] | ➢ Delaying medication doses until destination reached. | “I get, like, ashamed to take it on the bus, I feel embarrassed to take them out the bottle [of pills], but just like that I can lose one or two hours traveling without taking it but I take it when I get home.” | |

| Health Systems | |||

| DR-specific | • Mistrust of physicians in the DR and their prejudice against people with HIV. [PI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Failure to disclose HIV diagnosis to providers can lead to misdiagnosis of opportunistic infections or missed antiretroviral doses. | “You get sick in Santo Domingo for example and you can't say that. You can't say: look doctor, I have this and that. Do I tell you why? Because the doctor over there rejects you as a person.” |

| Both countries | • Limitations on amount of medication that can be dispensed, usually 1 month supply only [PI, KI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Treatment interruptions for people traveling >1 month or for people living at a distance from the clinic who are unable to travel monthly to pick up refills. | “Last year I went to Santo Domingo and I told the doctor to give me some extra pills because I was going to Santo Domingo and I was going to run out of them by the time I was there. Either the pharmacy or the doctor didn't sign and he didn't send them to me. I spent 10 days without taking the pill.” |

| • Travelers are unable to access medications at sites other than their treatment site. [PI, KI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Treatment interruptions if medications are lost or there are unanticipated extensions of travel. | “I don't know how I would manage to get the medicines away from here.” (Away from the clinic site.) | |

| Travel-related institutions | |||

| • Fear of customs agent discovering HIV diagnosis or confiscating medications [PI, KI; DR, NYC] | ➢ Hiding medications, transferring medications into Tylenol or vitamin bottles, not putting medications in carry ons leading to lack of access to medications or forgetting doses. | “They [customs] asked me what medications were those, I told them that they were medications for people living with HIV…they pretended but immediately dropped my things…they moved away, as if I had leprosy.” | |

| Travel-related institutions | |||

| • Rising cost of transportation to clinic for patients who live in other towns/rural areas [PI, KI; DR] | ➢ Impedes people traveling to clinic for medication pickup. | “If I don't have money and am unable to get some I have to skip that day of medicine. It has already happened to me this year. Now, for example, I had to come because I took it at 12 noon, didn't take it at night because I couldn't come.’ | |

| • Medications stolen out of luggage during travel [PI; NYC] | ➢ Missed medication doses. | “I missed it once because they stole this wallet from me…And they stole it from me because I fell asleep in the bus.” | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; DR, Santo Domingo-based interview; KI, key informant interview; NYC, NYC-based interview; PI, patient participant interview.

Individual barriers to care

Individual barriers were noted by relatively few patient participants (n=3) and included travel-related daily schedule changes and fear of side effects while traveling, both leading to delays in pill taking or forgotten doses. Several patients also mentioned that finding clean water or appropriate food to accompany pill taking was more difficult when traveling. One frequent long-stay traveler believed that vacation travel should include a medication holiday and self-discontinued ART with every trip. She acknowledged that this was discouraged by her providers and that she returned each time with virologic failure.

Societal barriers

Societal barriers were all related to fear of stigma and HIV disclosure. Both patient participants and key informants expressed views that stigma affected the patients' willingness to disclose HIV status, and many patient participants gave specific examples of rejection after diagnosis disclosure by family members, friends, work colleagues, and even members of the medical profession. To avoid being stigmatized by those around them, patient participants described hiding medications in other pill bottles while traveling so that no one would read the labels and discover their diagnosis. Others delayed medication doses until they reached their destination to avoid being observed taking pills. Patient participants described hiding their pills at their travel destination and keeping pills in locked luggage to avoid disclosure to family members or other people at their destination. As described above, those traveling for care also did so to escape stigma in their hometowns. All of these behaviors were noted to cause delays in pill taking or forgotten doses.

Health-systems based barriers

Insurers and clinics in the US and the DR typically provide a 1-month supply of pills, which is problematic for those traveling for more than 30 days. Patient participants and key informants described recurrent instances of patients being unable to procure pills while traveling after exhausting the 30-day supply. This was particularly problematic for trips that were extended unexpectedly due to family obligations or illness. The vast majority of patients interviewed took care to inform their providers prior to travel and receive refills of their prescriptions prior to departure.

Patient participants in the DR assessed providers in rural clinics as less skilled, and NYC-based participants expressed unwillingness to seek medical attention anywhere in the DR because of the perceived quality of care there. The NYC-based participants waited to return to NYC for treatment, leading to missed medication doses and worsening of medical conditions.

Transportation-related barriers

Transportation-related barriers included a fear that customs workers would search luggage and confiscate HIV medications. The fear of customs confiscating medications was expressed by many patient participants traveling internationally, but none had ever had this experience themselves. Patient participants described medications being lost when luggage was stolen on buses in the US and the DR. The rising cost of ground transportation in the DR led to delays in medication refills and delays in seeking medical attention for those traveling for care because they could not pay for transportation to the clinic. Despite these barriers, none of the patient participants wished to transfer their care to local clinics, citing stigma in their hometowns.

Relationship between mobility pattern, barriers/promoters of care, and adaptive behaviors

Many barriers to adherence and adaptive behaviors were specific to certain mobility taxonomies (Table 3). Only patient participants on vacation noted that they would also give themselves a “pill holiday” during travel, or hide their diagnosis so that they could “have a good time” with new sex partners. Those traveling for care experienced treatment interruptions because they could not afford transportation costs to pick up refills in clinic. Transnational and frequent long-stay travelers experienced treatment interruptions because they could only receive 30 days of medications and trips outlasted their pill supply. People traveling for work had more trouble with frequent changes in routine, particularly taxi drivers or those working overnight shifts.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Mobility Taxonomy and Promoters/Barriers to Engagement in HIV Care and Adherence and Compensatory Mechanisms Employed by Patients to Ensure Adherence During Travel

| Mobility taxonomy | Promoters | Barriers | Compensatory/adaptive behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacation travel | <1 month trips lead to less likelihood of lack of medication supply | Vacation seen as a time to also have a pill holiday -> treatment interruptions | |

| Hiding HIV status during travel -> forgetting medication doses because pills are hidden | |||

| Frequent long-stay travel | Difficulties in hiding diagnosis from relatives/friends at receiving site -> hiding medications, delays in dosing | Trips fall into a pattern so disruptions in schedule that lead to adherence problems can be minimized | |

| Participants usually remembered to take their pills despite them being hidden | |||

| Transnational | Increased social support through ties to family in other locations | Interruptions in medical supply secondary to limited amount that can be dispensed by pharmacies lead to adherence problems | Family members or friends ship medications internationally |

| Longer trips -> more likely to need to seek care while traveling and most participants unwilling to seek care outside of their primary clinic | Knowledge/willingness to access medical care at receiving site, including some international travelers who asked primary clinic to provide contact information for trusted HIV providers at destination | ||

| Fear of stigma/prejudice in DR leads to delaying care long enough to return to NYC rather than accessing treatment there -> treatment interruption or delays in seeking needed medical care | |||

| Travel for care | Perception that they are receiving superior medical care in the “big city” | Transportation unreliability and cost -> to disruptions in medication refills | Setting aside funds for travel to clinic throughout the month |

| Escape from potential for public disclosure of diagnosis at home | Having other family members/friends who live near the clinic pick up medications for them | ||

| Work-related travel | Change in routine, particularly overnight work, creates problems for medications that must be taken on a schedule | Setting alarms as medication reminders | |

| Adjusting pill schedule so that it coincides with work schedule |

Behaviors noted to be adaptive included those that minimized schedule disruptions or allowed for adjustment (such as changing pill dosing schedules to match overnight work schedules), and those that allowed patients to work around the difficulties procuring pills while traveling for extended trips.

Key informant perceptions of barriers to adherence and engagement in care for geographically mobile individuals

All key informants felt that geographic mobility was a barrier to engagement in care and adherence. Non-adherence when traveling was commonly perceived as the individual patient's fault. Key informants said that patients failed to prepare in advance for travel leading to treatment interruption, were forgetful when traveling, or wanted to hide their diagnosis by not taking pills on trips. A few key informants expressed the idea that NYC-based patients were taking advantage of the system by living in the tropics while receiving care through Medicaid. Others perceived that patients hid their diagnosis so that they could engage in risky sexual behavior without worrying about disclosure.

Some patients expressed this same individual-responsibility model, blaming themselves for lapses in care related to travel. When asked what type of intervention would help travelers adhere to treatment, many patient participants proposed travel planning assistance, implying that lack of preparation was the cause of adherence lapses. This perception is consistent with the perception of the key informants, but differs from the patients' reports that most of the trips were planned and, for shorter trips, they traveled with a sufficient supply of antiretroviral therapy.

The barriers to engagement in care and adherence cited by the same patient participants were mostly structural (e.g., stigma and inability to obtain more than a 30-day medication supply) and do not involve individual responsibility. This represents a stark disconnect between the perception and experience with mobility-induced barriers to engagement in care and adherence.

Discussion

The data presented here support the need for a paradigm shift in discussions of geographic mobility and its impact on HIV care. Mobility mapping demonstrates that mobility patterns are complex, and motivation for travel impacts the mobility pattern, which, in turn, determines its effect on adherence and engagement in care. Barriers were most often structural, rather than individual, and include HIV-related stigma and the inability to access care or medications at the destination site, particularly for long-stay travelers and transnationals. Mobility rarely facilitated engagement with care, with the exception of individuals traveling to urban clinics because they felt care was better and less stigmatized at an urban site further from home. We also note discordance between patient and provider emphasis on individual-level barriers to care, such as failure to plan for trips, and the dominant barriers found in the analysis, which were structural.

Our findings differ from previous studies, which used more limited definitions of mobility, such as immigration, migrant return travel to home country, or change of residence.15,19,28 The ethnographic study design allowed us to define multiple types of geographic mobility, and examine structural and individual level barriers to and promoters of care. The incorporation of transnationality, rather than permanent settlement and permanent return, provides a more detailed description of the ties that some Dominicans retain to both sides of the airbridge.37 Oversimplification of “mobility” into a quantitative measurement, such as distance traveled or even a simple binary (traveler/not traveler), obscures how motivation for travel (vacation, work, family) shapes engagement in HIV care and whether its impact is positive or negative.

Prior research has suggested that fear of unintentional disclosure of HIV status leads to non-adherence while traveling,42 but this is frequently thought of as an individual-level risk. The HIV-associated stigma that leads to this fear, however, is a structural/societal barrier, and we join many others in arguing that this is appropriately addressed at the community rather than the individual level.41,43,44 These findings add to the growing body of literature regarding the impact of HIV-related stigma on Hispanic communities.38,39 This stigma may lead to reluctance to be tested for HIV and delays in seeking care that lead to presentation with more advanced disease.12,40,41,44 In this investigation, we found that stigma affected all mobile participants' ability to adhere to medication and engage in care when away from home.

Limitations of the study include that we gathered in-depth data from a relatively small sample of mobile individuals and key informants regarding a specific demographic group, Dominicans living with HIV. Despite the small sample size, the qualitative research design enabled collection of detailed data on multiple different patterns of mobility. There are other migration-linked communities, including those on either side of the US/Mexico border, communities in sub-Saharan Africa, and the multiple immigrant populations of NYC, where these findings could be relevant.7,39,40,45–50 Only patients in care were recruited into the study; individuals who abandoned treatment entirely due to mobility were not included in the sample. Another limitation is that this study does not provide data on the extent of mobility in the overall population of Dominicans living with HIV. However, other data, including a household survey of individuals living in Washington Heights, show that Dominicans in the US are highly mobile, with 15% of respondents having traveled to the DR in the past 6 months.51–53

Our data support prior assertions that mobility may be an important part of the lives of many Dominicans in NYC and the DR,40,53 and recommending against travel is unlikely to be successful as an intervention. Such advice from providers could result in patients hiding travel-related plans from care providers, rather than seeking assistance in trip planning. Interventions should seek to counter the blaming of individuals for non-adherence expressed by patients and care providers, which could hamper communication between patient and provider. Stigma and its negative consequences are unlikely to be addressed by individual-level interventions, but could be reduced through community-based empowerment of disenfranchised groups, and other structural-level interventions.43,54,55 Health care and transportation-related barriers could be resolved by expanded access to medication refills outside of primary treatment sites, or integrated information systems that would allow providers to access travelers' medical history. Increased local access to HIV treatment in the DR is unlikely to eliminate patients' desire to travel for care, because fear of stigma and concern about HIV care quality leads patients to seek care at urban sites away from their hometowns.

Future investigations are needed to determine the extent of mobility amongst HIV-infected Dominicans and its impact on HIV treatment outcomes, such as ART failure. Geographic mobility may be an under-recognized but important determinant of engagement in care and antiretroviral adherence in some populations. As overall population mobility increases, finding novel approaches to combat mobility-induced barriers to care will be critical to the success of treatment programs for HIV and other chronic illnesses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants for lending us their time and their stories, and for the contributions of Raziel Valiño, Vixcelyn Bello, Martha Perez, Dr. Glenn Martinez, Juan Reyna, the students of the University of Texas-Pan American for interviews and transcriptions.

This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases [K23AI081538 to B. Taylor], and award number R24HD058486 to the Columbia Population Research Center from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Sutherst RW. Global change and human vulnerability to vector-borne diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:136–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2008 Revision. Geneva: UN Database, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD. Human mobility and population health. New approaches in a globalizing world. Perspect Biol Med 2001;44:390–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montealegre JR, Risser JM, Selwyn BJ, McCurdy SA, Sabin K. Prevalence of HIV risk behaviors among undocumented Central American immigrant women in Houston, Texas. AIDS Behav 2012;16:1641–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. Population Mobility and AIDS: UNAIDS Technical Update. Geneva: UNAIDS, February2001 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: A review of international research. AIDS 2000;14:S22–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and nonmigrant men and their partners. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer TH, Hasbun J, Ryan CA, et al. Migration, ethnicity and environment: HIV risk factors for women on the sugar cane plantations of the Dominican Republic. AIDS 1998;12:1879–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deren S, Kang SY, Colon HM, et al. Migration and HIV risk behaviors: Puerto Rican drug injectors in New York City and Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health 2003;93:812–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanchez MA, Lemp GF, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. The epidemiology of HIV among Mexican migrants and recent immigrants in California and Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;37:S204–S214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dennis AM, Wheeler JB, Valera E, et al. HIV risk behaviors and sociodemographic features of HIV-infected Latinos residing in a new Latino settlement area in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Care 2013;25:1298–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert PA, Rhodes SD. HIV testing among immigrant sexual and gender minority Latinos in a US region with little historical Latino presence. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:628–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poon KK, Dang BN, Davila JA, Hartman C, Giordano TP. Treatment outcomes in undocumented Hispanic immigrants with HIV infection. PLoS One 2013;8:e60022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saracino A, Tartaglia A, Trillo G, et al. Late presentation and loss to follow-up of immigrants newly diagnosed with HIV in the HAART era. J Immigr Minor Health 2013. Epub ahead of print August14, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Knodel J, VanLandingham M. Return migration in the context of parental assistance in the AIDS epidemic: The Thai experience. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:327–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berk ML, Schur CL, Dunbar JL, Bozzette S, Shapiro M. Short report: Migration among persons living with HIV. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.London AS, Wilmoth JM, Fleishman JA. Moving for care: Findings from the US HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. AIDS Care 2004;16:858–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogg RS, Schechter MT, Schilder A, et al. Access to health care and geographic mobility of HIV/AIDS patients. AIDS Patient Care 1995;9:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogg RS, Whitehead J, Ricketts M, et al. Patterns of geographic mobility of persons with AIDS in Canada from time of AIDS index diagnosis to death. Clin Invest Med 1997;20:77–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood E, Yip B, Gataric N, et al. Determinants of geographic mobility among participants in a population-based HIV/AIDS drug treatment program. Health Place 2000;6:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews JR, Wood R, Bekker LG, Middelkoop K, Walensky RP. Projecting the benefits of antiretroviral therapy for HIV prevention: The impact of population mobility and linkage to care. J Infect Dis 2012;206:543–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment–United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1618–1623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dombrowski JC, Kent JB, Buskin SE, Stekler JD, Golden MR. Population-based metrics for the timing of HIV diagnosis, engagement in HIV care, and virologic suppression. AIDS 2012;26:77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geng EH, Bangsberg DR, Musinguzi N, et al. Understanding reasons for and outcomes of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral therapy programs in Africa through a sampling-based approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:405–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasti SP, Simkhada P, Randall J, Freeman JV, van Teijlingen E. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Nepal: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e35547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiser S, Wolfe W, Bangsberg D, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence for patients living with HIV infection and AIDS in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;34:281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor BS, Garduno LS, Reyes EV, et al. HIV care for geographically mobile populations. Mt Sinai J Med 2011;78:342–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sellier P, Clevenbergh P, Ljubicic L, et al. Comparative evaluation of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan African native HIV-infected patients in France and Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:654–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark SJ, Collinson MA, Kahn K, Drullinger K, Tollman SM. Returning home to die: Circular labour migration and mortality in South Africa. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2007;69:35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima VD, Druyts E, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Regional and temporal trends in migration among people living with HIV/AIDS in British Columbia, 1993–2005. Can J Public Health 2010;101:44–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagee A, Remien RH, Berkman A, et al. Structural barriers to ART adherence in Southern Africa: Challenges and potential ways forward. Glob Public Health 2011;6:83–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: An ethnographic study. PLoS Med 2009;6:e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haour-Knipe M, de Zalduondo B, Samuels F, Molesworth K, Sehgal S. HIV and “People on the Move”: Six strategies to reduce risk and vulnerability during the migration process. Intl Migr 2013:1–17 [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNAIDS, International Organization for Migration. Migration and AIDS. Intl Migr 1998;36:445–468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siedner MJ, Lankowski A, Tsai AC, et al. GPS-measured distance to clinic, but not self-reported transportation factors, are associated with missed HIV clinic visits in rural Uganda. AIDS 2013;27:1503–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plaza D. Transnational return migration to the English-speaking Caribbean. Rev Eur Migr Intl 2008;24 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiller NG, Basch L, Blanc CS. From immigrant to transmigrant: Theorizing transnational migration. Anthropol Quart 1995;68:48–63 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shedlin MG, Decena CU, Oliver-Velez D. Initial acculturation and HIV risk among new Hispanic immigrants. J Natl Med Assoc 2005;97:32S–37S [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deren S, Shedlin M, Decena CU, Mino M. Research challenges to the study of HIV/AIDS among migrant and immigrant Hispanic populations in the United States. J Urban Health 2005;82:iii13–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shedlin MG, Shulman L. Qualitative needs assessment of HIV services among Dominican, Mexican and Central American immigrant populations living in the New York City area. AIDS Care 2004;16:434–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang BN, Giordano TP, Kim JH. Sociocultural and structural barriers to care among undocumented Latino immigrants with HIV infection. J Immigr Minor Health 2012;14:124–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coetzee B, Kagee A, Vermeulen N. Structural barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a resource-constrained setting: The perspectives of health care providers. AIDS Care 2011;23:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Golub SA, Gamarel KE. The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: Findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:621–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehta SR, Delport W, Brouwer KC, et al. The relatedness of HIV epidemics in the United States-Mexico border region. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010;26:1273–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy V, Prentiss D, Balmas G, et al. Factors in the delayed HIV presentation of immigrants in Northern California: Implications for voluntary counseling and testing programs. J Immigr Minor Health 2007;9:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carabin H, Keesee MS, Machado LJ, et al. Estimation of the prevalence of AIDS, opportunistic infections, and standard of care among patients with HIV/AIDS receiving care along the U.S.-Mexico border through the Special Projects of National Significance: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2008;22:887–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zuniga ML, Brennan J, Scolari R, Strathdee SA. Barriers to HIV care in the context of cross-border health care utilization among HIV-positive persons living in the California/Baja California US-Mexico border region. J Immigr Minor Health 2008;10:219–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coffee M, Lurie MN, Garnett GP. Modelling the impact of migration on the HIV epidemic in South Africa. AIDS. 2007;21:343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deren S, Kang SY, Colon HM, Robles RR. The Puerto Rico-New York airbridge for drug users: Description and relationship to HIV risk behaviors. J Urban Health 2007;84:243–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cushman L, Caceres Ureña F, Cairo L, Bautista-Jiménez A, Estévez G. Finding their way: A qualitative study of adolescent migration between the Dominican Republic and the United States. Santo Domingo: Asociación Dominicana Pro Bienestar de la Familia, Inc., 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Padilla MB, Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Reyes AM. HIV/AIDS and tourism in the Caribbean: An ecological systems perspective. Am J Public Health 2010;100:70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhat M, Dumortier C, Taylor BS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus ST398, New York City and Dominican Republic. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;15:285–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Low C, Pop-Eleches C, Rono W, et al. The effects of home-based HIV counseling and testing on HIV/AIDS stigma among individuals and community leaders in western Kenya: Evidence from a cluster-randomized trial(.). AIDS Care 2013;25:S97–S107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campbell C, Nhamo M, Scott K, et al. The role of community conversations in facilitating local HIV competence: Case study from rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 2013;13:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]