Abstract

Despite antiretroviral therapy, pneumonias from pathogens such as pneumococcus continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected individuals. Respiratory infections occur despite high CD4 counts and low viral loads; therefore, better understanding of lung immunity and infection predictors is necessary. We tested whether metabolomics, an integrated biosystems approach to molecular fingerprinting, could differentiate such individual characteristics. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALf ) was collected from otherwise healthy HIV-1-infected individuals and healthy controls. A liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry method was used to detect metabolites in BALf. Statistical and bioinformatic analyses used false discovery rate (FDR) and orthogonally corrected partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify groupwise discriminatory factors as the top 5% of metabolites contributing to 95% separation of HIV-1 and control. We enrolled 24 subjects with HIV-1 (median CD4=432) and 24 controls. A total of 115 accurate mass m/z features from C18 and AE analysis were significantly different between HIV-1 subjects and controls (FDR=0.05). Hierarchical cluster analysis revealed clusters of metabolites, which discriminated the samples according to HIV-1 status (FDR=0.05). Several of these did not match any metabolites in metabolomics databases; mass-to-charge 325.065 ([M+H]+) was significantly higher (FDR=0.05) in the BAL of HIV-1-infected subjects and matched pyochelin, a siderophore-produced Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Metabolic profiles in BALf differentiated healthy HIV-1-infected subjects and controls. The lack of association with known human metabolites and inclusion of a match to a bacterial metabolite suggest that the differences could reflect the host's lung microbiome and/or be related to subclinical infection in HIV-1-infected patients.

Introduction

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has decreased opportunistic infections associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection; however, pneumonias from routine pathogens such as pneumococcus and influenza continue to cause significant morbidity and mortality.1–5 A recent study in the Veterans Administration (VA) HIV-1 Cohort found that bacterial pneumonia was the most common pulmonary disease, with an incidence of 28.0 [95% confidence interval (CI), 27.2–28.8] compared with 5.8 (95% CI, 5.6–6.0) per 1,000 person years among HIV-1-uninfected individuals (p=0.001).6 HIV-1 infection causes premature immune senescence predisposing individuals to serious lung infections. However, lung infections continue to occur despite high CD4 counts and low viral loads; to understand the underlying mechanisms, new methods are needed for identifying predictors of lung immune health in individuals living with HIV-1.

Metabolomics is part of an integrated biosystems approach to providing a molecular fingerprint that mirrors an individual's phenotype. An integrated biosystems approach uses information from population and molecular studies as a basis for the design of systems models that improve disease classification and predict behavior.7 Computational models based upon these designs can then be used to evaluate the effects of multiple elements within the model to predict outcomes for an individual with a unique set of characteristics.8 Metabolomic analyses have been performed previously in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid in both preclinical animal models and clinically in patients with cystic fibrosis9 and preterm infants complicated by respiratory distress syndrome10 using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Additionally, metabolomics have been used to understand metabolic changes that occur during long-term bacterial infection11 and even to improve diagnostic capabilities of community-acquired pneumonia.12–14 There is a limited amount of data regarding metabolomic approaches in HIV-1-infected patients. Small studies have been done to characterize the profile of oral wash metabolites,15 to identify differentially regulated metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid of SIV-infected monkeys16 and humans17 with central nervous system disease, and to investigate drug interactions and side effects.18–20 These studies suggest that metabolomics is not only a tool for diagnosis, but is an instrument to better understand microbial–host interactions, monitor health, and assist in drug development.

New high-throughput technologies enable metabolome-wide association studies (MWAS) where the association of metabolites with a given disease can be studied. MWAS techniques may identify metabolic pathways and biomarkers, which could provide a foundation for metabolomics, along with genomics and epigenomics, to support integrated models for personalized medicine. We have developed a high-resolution mass spectrometry method that allows the detection of 3,300–7,000 metabolite features in biological samples.8,21 We conducted a study to investigate the global metabolic pathways in the BAL fluid of otherwise healthy HIV-1-infected subjects to determine if specific metabolites could differentiate these HIV-1-infected individuals from healthy controls. Further research in this area may lead directly to individualized models that can be used for personalized health prediction, risk evaluation, and treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This project was conducted at Grady Memorial Hospital, an affiliate of Emory University, from July 2010 through August 2011. HIV-1-infected patients with and without ART were screened and enrolled from the Infectious Disease Program at the Ponce de Leon Center, Grady Medicine and Pulmonary Clinics, and the Grady community. Subjects were given a brief overview of the purpose of the study by an informed healthcare provider to identify possible participants. Subjects who were less than 25 years of age, pregnant, malnourished [defined as a body mass index (BMI) less than 17], current smokers (defined as tobacco use less than 10 years prior), current substance abuse by self-report, with diabetes, active liver disease (defined as cirrhosis or a total bilirubin greater than 2.0 mg/dl), heart disease [defined as having an ejection fraction less than 50%, history of acute myocardial infarction, or New York Heart Association (NYHA) II–IV], renal disease (defined as being dialysis dependent or having a creatinine greater than 2.0 mg/dl), or lung disease [defined as a history of lung disease with a forced vital capacity (FVC) or forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) less than 80% of predicted] were excluded. In addition, subjects with a history of prior pneumonias were also excluded. A comparison group of HIV-1-uninfected subjects (hereafter referred to as control subjects) with the same exclusion criteria was recruited from the Grady community. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment into the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University (Atlanta, GA) and the research oversight committee of Grady Memorial Hospital. Detailed information about participants in this study is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-1-Infected Subjects (n=24) and Healthy Controls (n=24) Enrolled in the Study

| Variables | Healthy control | HIV-1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (N) | 24 | 24 | |

| Age (years)a | 43.5 (31.3–47.8) | 48 (39.3–51.8) | 0.03 |

| Gender (% male) | 54.2 | 37.5 | 0.25 |

| Race n (%) | 0.10 | ||

| White | 6 (25) | 2 (8.3) | |

| Black | 15 (62.5) | 22 (91.7) | |

| Other | 3 (12.5) | 0 | |

| BMIa | 30 (26.5–36.3) | 33 (29–38) | 0.11 |

| SMASTa | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–3) | 0.26 |

| AUDITa | 1 (0–2.8) | 1 (0–2) | 0.99 |

| CD4 counta | 432 (271–586) | ||

| Viral load (log copies/ml)a | 4.1 (3.2–4.2) |

Results are represented as medians with interquartile range.

BMI, body mass index; SMAST, Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

Study procedures

After informed consent was obtained, all subjects completed a preenrollment evaluation (visit 1) that included (1) complete history and physical examination, (2) routine blood chemistries (basic chemistry, liver function tests, complete blood count, coagulation parameters), unless already performed as part of routine clinical care within the last 4 weeks, (3) CD4 and viral load, unless already performed as part of routine clinical care within the past 3 months, (4) urine pregnancy test (qualitative β-HCG), (5) urine dipstick for cotinine, (6) spirometry (FEV1, FVC), (7) Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (SMAST) and Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) alcohol use questionnaires, and (8) BMI. An AUDIT score greater than or equal to 6 or a SMAST score greater than or equal to 3 were classified as having a positive history of chronic alcohol abuse, as previously validated.22,23 Demographic data were collected when subjects underwent initial screening for the study.

Subjects with exclusions identified at the time of the preenrollment evaluation were excluded from further participation. After completing the preenrollment evaluation to confirm eligibility, subjects were admitted to the Grady Clinical Interaction Network site after an overnight fast to undergo flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy with standardized BAL technique. Isotonic saline, 180 ml, was injected in a subsegment of the right middle lobe or lingula using standard conscious sedation techniques. Of all BAL samples 92% were collected by Dr. Cribbs (PI), while 8% were collected by other pulmonary physicians using a standardized protocol. Subjects were contacted by phone 24 h after completing the study to ensure patient safety.

Metabolomics

Samples were extracted and analyzed by liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-FTMS) as previously described.21,24 Briefly, 100-μl aliquots of BAL fluid were treated with acetonitrile (2:1, v/v), containing internal standard mix, and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 5 min at 4°C to remove protein25 and maintained at 4°C until injection. Data were collected by a Thermo LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Diego, CA) from m/z 85 to 850 over 10 min with each sample analyzed in triplicate. Peak extraction and quantification of ion intensities were performed by an adaptive processing software package (apLCMS) designed for use with LC-FTMS data,26 which provided tables containing m/z values, retention time, and integrated ion intensity for each m/z feature. The data were log-transformed, median centered, scaled to have unit variance, and quantile normalized27,28 prior to statistical and bioinformatic analyses.

Biostatistics and bioinformatics

Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed to compare continuous demographic characteristics between HIV-1 and control subjects. Pearson chi-square tests were used to compare categorical characteristics. Statistical analyses were conducted in NCSS statistical software except as indicated below. All reported p-values were two-sided and p-values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant. High-resolution mass spectral data were filtered to include only m/z features where at least one group (HIV-1 or control) had values for 70% of samples. LIMMA package in R (Linear Models for Microarray Data) in Bioconductor was used to identify differentially expressed features at a significance threshold of 0.05 after false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment. Two-way hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) was performed to identify clusters of individuals associated with discriminating clusters of metabolites using the heatmap.2 function in the R package gplots.29 Hierarchical clustering was performed using the built-in hclust() function in R that uses the complete-linkage method for clustering. Pearson correlation was used as the dissimilarity measure. Orthogonal signal correction (OSC) partial least squares discriminatory analysis (OPLS-DA) was done using Matlab. The discriminatory features were selected as the top 5% accounting for 95% separation of healthy HIV-1 from controls. More stringent requirements were used, as indicated, for the statistical tests compared to the OPLS-DA, which resulted in a different number of features. Cross-validation was performed using both a 10-fold method and a leave-one-out method (LOO).

Results

Demographics of HIV-1-infected subjects and healthy controls

Twenty-four subjects with HIV-1 and 24 healthy controls were enrolled (Table 1). Subjects were similar except that HIV-1 subjects were older compared to the control subjects (48 vs. 43.5 years, p=0.03). Additionally, the HIV-1 group had a greater percentage of male subjects, although this result was not statistically significant (54.2% vs. 37.5%, p=0.25). Subjects in both groups were mostly African American and did not abuse alcohol, as defined by SMAST and AUDIT questionnaires. The median CD4 count of the HIV-1-infected subjects was 432 (IQR 271–586) with a medial viral load of 4.1 log copies/ml (IQR 3.2–4.2).

Hierarchical clustering of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among all subjects

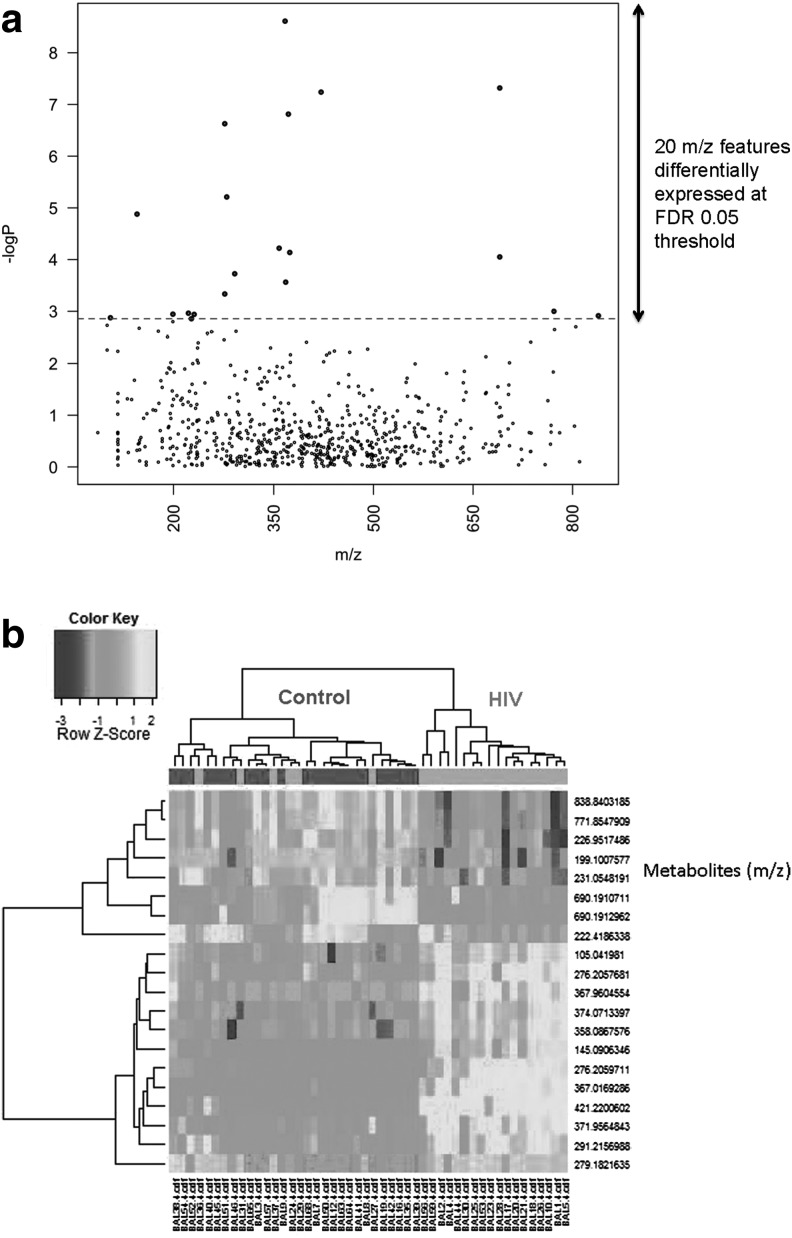

C18 chromatography resulted in a total of 2,446 m/z features; 673 features remained after removal of m/z features present in <70% of replicates. Twenty features were significantly different between healthy HIV-1 and controls at FDR=0.05 (see Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid). These are illustrated in a Manhattan plot of the negative log p as a function of the individual m/z features (Fig. 1a). Two-way HCA of these features showed that most of the healthy HIV-1-infected individuals were clustered together and separated from most of the controls (Fig. 1b). The 20 features grouped into three clusters (see Supplementary Table S1). Database searches showed that cluster one included features that matched to tripeptides, while cluster two showed some environmental metabolites and other drug-related metabolites. Cluster 3 was an individual feature that did not match any metabolite, and Clusters 1 and 2 also contained features without database matches.

FIG. 1.

(a) Manhattan plot of the negative log p as a function of the 20 individual m/z features identified using C18 chromatography. (b) Hierarchical clustering analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among all subjects using C18 chromatography.

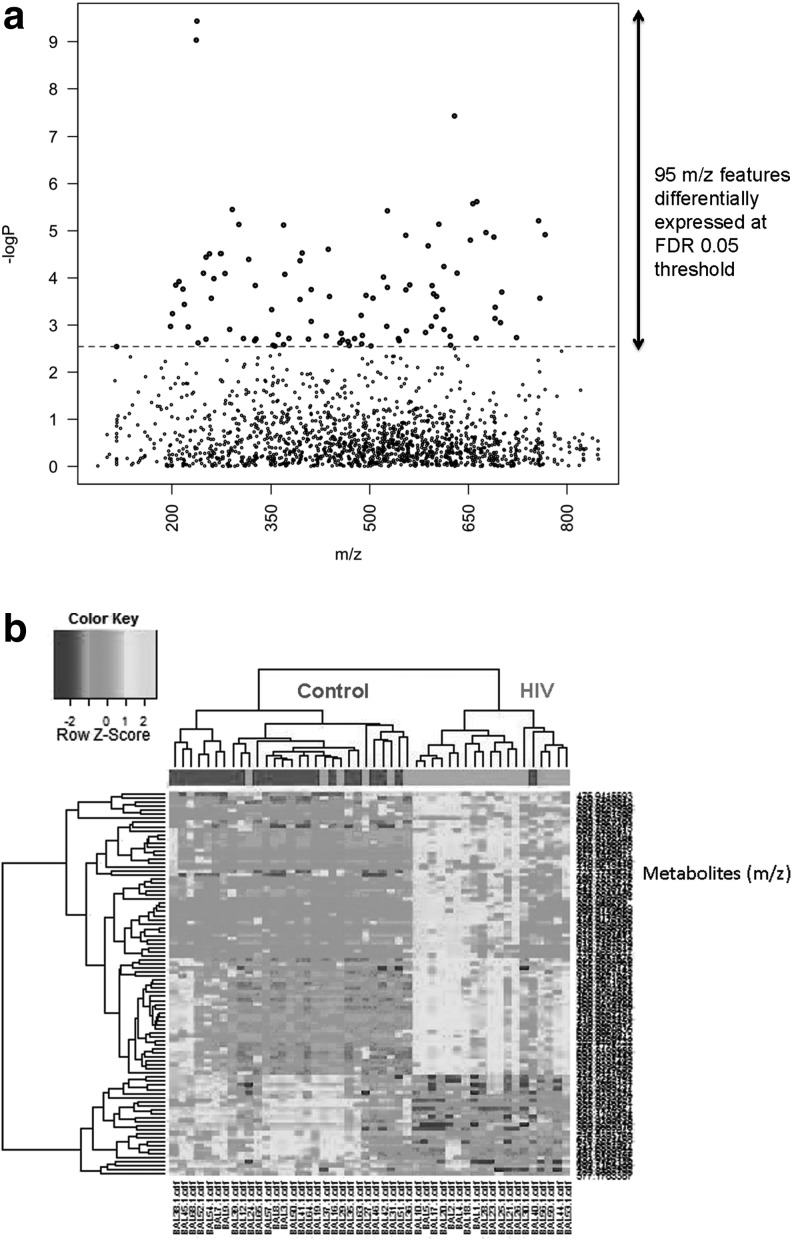

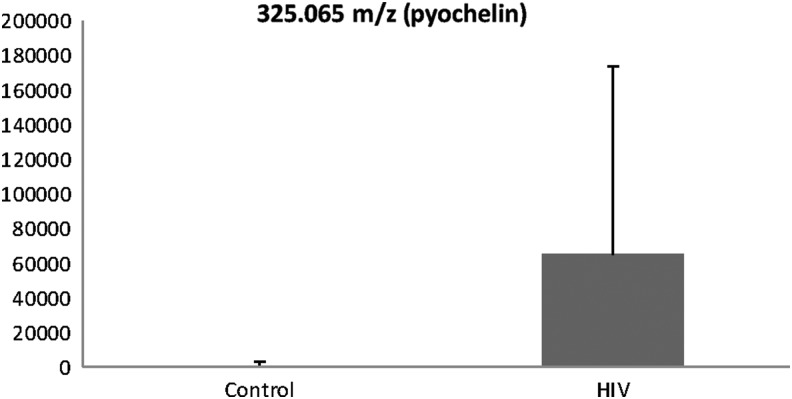

Anion exchange (AE) analysis resulted in a total of 2,756 m/z features; 1,583 features remained after removal of m/z features present in <70% of the replicates. Ninety-five features were significantly different between healthy HIV-1 and controls at FDR=0.05 (see Supplementary Table S1). These are illustrated in a Manhattan plot of the negative log p as a function of the individual m/z features (Fig. 2a). Two-way HCA of these features showed that most of the healthy HIV-1-infected individuals were clustered together and separated from most of the controls (Fig. 2b). These metabolites grouped into five clusters (see Supplementary Table S1). Cluster one showed a large number of environmental and food metabolites, in addition to several tripeptides and metabolites likely related to ART. Cluster two also showed a large number of naturally occurring metabolites including environmental toxins (i.e., pesticides), fungal metabolites, and food by-products. In addition, cluster two also revealed a metabolite known as pyochelin, a siderophore of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Further metabolite analysis showed that there was a significantly higher level of pyochelin in the HIV-1-infected subjects compared to the healthy controls (FDR 0.05) (Fig. 3). Cluster three did not produce any matches while cluster four metabolites contained tripeptides as well as food derivatives and steroidal derivatives. Cluster five metabolites were all related to phospholipids.

FIG. 2.

(a) Manhattan plot of the negative log p as a function of the 95 individual m/z features identified using anion exchange analysis. (b) Hierarchical clustering analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among all subjects using anion exchange analysis.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of metabolite pyochelin in the HIV-1-infected subjects compared to healthy controls.

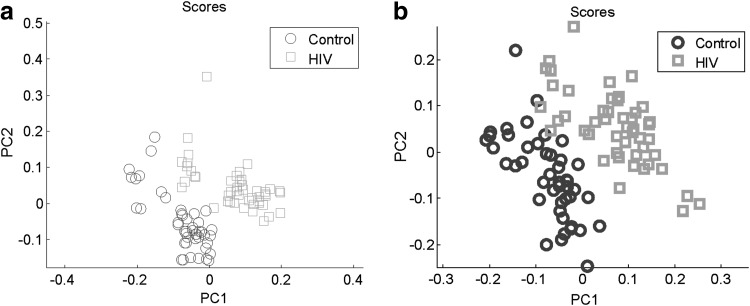

Orthogonal signal correction partial least square-discriminant analysis

OPLS-DA was used to select the top 5% of features accounting for 95% separation between the groups. Figure 4a and b shows score plots from C18 and AE analysis, respectively, depicting the ability to separate metabolites related to HIV-1-infected subjects from those related to control subjects. A total of 132 features were identified using C18 chromatography and 148 features were identified using AE analysis. The 132 features identified using C18 were compared to 20 significant features by FDR; eight features overlapped. These eight features included tripeptides and a number of environmental organic compounds. The 148 identified features using AE were compared to the 95 significant features by FDR; 10 features overlapped. These 10 features included metabolites related mostly to environmental compounds, although there was a metabolite related to silicone liquid and one related to a local anesthetic drug. Cross-validation using both 10-fold and LOO methods was performed. For the C18 column, 10-fold cross-validation was 98% and LOO cross-validation was 97.91%. For the AE column, 10-fold cross-validation was 90% and LOO cross-validation was 89.58%.

FIG. 4.

(a) Orthogonal signal correction partial least squares discriminatory analysis (OPLS-DA) of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among all subjects using C18 chromatography. (b) OPLS-DA of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid among all subjects using anion exchange analysis.

Discussion

The results from this study showed that overall metabolic profiles in BAL fluid were different between otherwise healthy subjects with HIV-1 compared to controls, using an LC-FTMS method with C18 chromatography and AE. These features could reflect the host's lung microbiome or may be related to bacterial pathways in HIV-1-infected patients compared to healthy controls; therefore, a specific metabolomic profile in HIV-1 patients may be identified as a diagnostic and prognostic marker of lung immune function and subsequent lung health. However, there were several significant features that discriminated HIV-1-infected subjects and controls that remained unidentified. Further verification and identification of the metabolome in HIV-1-infected subjects are critical to understanding lung immune dysfunction in this vulnerable population.

Ghannoum et al. characterized the profile of oral metabolites in HIV-1-infected patients using metabolomics and found 27 metabolites were differentially present in subjects with HIV-1 compared to controls.15 Others have evaluated metabolomic profiles in BAL fluid9,10,30,31; however, this is the first study that we know of that has been done to evaluate metabolomics profiles in BAL fluid of HIV-1-infected subjects and compared them to healthy controls utilizing the LC-FTMS method. Identification and verification of the high-resolution metabolome will be important to gain mechanistic insights into how HIV-1 affects lung immunity.

Currently CD4 counts and viral loads are used as prognostic markers in HIV-1-infected individuals; however, lung infections continue to occur in patients with high CD4 counts and low viral loads, specifically bacterial pneumonia.1–3 Therefore, new methods are needed to identify predictors of lung immune health in individuals living with HIV-1. Metabolomic analyses will allow us to investigate various pathways previously unrecognized to be perturbed by chronic HIV-1 infection. For example, it is possible to detect metabolites that are by-products of various bacterial processes through metabolomics. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium responsible for opportunistic infections, produces two major siderophores to efficiently assimilate iron for proliferation, pyochelin and pyoverdine. These metabolites are synthesized and excreted by bacteria in iron-depleted conditions, and potentially may play a role in other biologically relevant metal-depleted environments.32 Martin et al. have shown that pyoverdine was present in 93/143 sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients and there was a strong association between the amount of pyoverdine and the number of P. aeruginosa present.33 Additionally, pyochelin may result in increased airway oxidative stress.34 Our data showed that pyochelin levels were significantly elevated in the HIV-1-infected subjects compared to control subjects, suggesting that P. aeruginosa may have been present in the lower airways of our otherwise healthy HIV-1-infected subjects (see Fig. 3). Given that our subjects were healthy with no prior history of pneumonia, it is possible that P. aeruginosa was just a colonizer in the lower airways; however, this colonization could increase oxidative stress and the risk for infection. The ability to detect specific metabolites such as pyochelin early on in the course of disease may allow for prognostic biomarkers of lung immune health that extend far beyond just CD4 counts and viral loads.

Extracellular redox potential in the lung can be quantified by an invasive BAL procedure or noninvasively via exhaled breath condensate (EBC). Collection of EBC has several advantages over traditional BAL sampling of the lower airways. It is easy to perform, is noninvasive, does not introduce foreign substances into the lung, and has been standardized.35 Furthermore, it can be performed repeatedly on sick patients. Metabolomics have been previously performed in EBC,36,37 but many of these studies have used NMR spectroscopy. Furthermore, no study has compared metabolomics in EBC to BAL previously. Some important points about EBC are that it samples a greater proportion of the respiratory tract compared to BAL and the relative contribution of each part is unknown. Additionally, EBC is collected via the mouth, so the sample may be affected by oral components.

This study has a number of limitations. This is an observational cross-sectional study and so is subject to bias; specifically, differences in the two groups (HIV-1 and control) could have occurred from unmeasured confounders, which could have affected metabolic profiling. However, confounding was minimized by restricting the population to a select group of individuals who were otherwise healthy and without any major medical problems. Additionally, HIV-1-infected subjects on average were older by 4.5 years. Although this was a statistically significant difference, the clinical relevance with respect to lung metabolome is unclear at this time. Third, bias could have been introduced due to measurement error. For example, we did not check HIV status on the control subjects; therefore, it is possible that control subjects could have recently been infected with the virus and be unaware of their status. However, medical charts were reviewed on all subjects to minimize any misclassification. Also, misclassification in this regard would have biased the results toward the null and given that significant differences were found between the two groups, it likely that misclassification did not occur.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in this study that metabolomic profiles in BAL fluid differentiated otherwise healthy HIV-1-infected subjects from control subjects. Although several significant features that discriminated HIV-1-infected subjects and controls remained unidentified, inclusion of a match to a bacterial metabolite suggests that the differences could reflect the host's lung microbiome and/or be related to subclinical infection in HIV-1-infected patients. Studies are being done currently evaluating the respiratory microbiome in HIV-1-infected patients.38 It is possible that even HIV-1 patients with elevated CD4 counts and undetectable viral loads may have bacterial colonization, which could lead to an increase in airway oxidative stress and impaired lung immunity, putting patients at increased risk for further infection. The results from this study will increase our understanding of lung immunity in individuals living with HIV-1 infection, and potentially enable us to change clinical practice paradigms, for it is possible that we will be able to identify new biomarkers to predict those HIV-1-infected individuals who are at a higher risk for lung infection. Further studies utilizing metabolomics in subgroups of HIV-1-infected individuals need to be done to further evaluate this possibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Joel Andrews, RN, BSN for all his help with recruitment and enrollment of study subjects and IRB regulations. Sources of support: KL2 TR000454, UL1 TR000454, and HL113451.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Hirschtick RE, Glassroth J, Jordan MC, et al. : Bacterial pneumonia in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Pulmonary Complications of HIV Infection Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995;333(13):845–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin JC. and Nichol KL: Excess mortality due to pneumonia or influenza during influenza seasons among persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(3):441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordano Q, Falco V, Almirante B, et al. : Invasive pneumococcal disease in patients infected with HIV: Still a threat in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38(11):1623–1628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordin FM, Roediger MP, Girard PM, et al. : Pneumonia in HIV-infected persons: Increased risk with cigarette smoking and treatment interruption. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178(6):630–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, et al. : CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med 2006;355(22):2283–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crothers K, Huang L, Goulet JL, et al. : HIV infection and risk for incident pulmonary diseases in the combination antiretroviral therapy era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183(3):388–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voit E. and Brigham K: The role of systems biology in predictive health and personalized medicine. Open Pathol J 2008;2:68–70 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DP, Park Y, and Ziegler T: Nutritional metabolomics: Progress in addressing complexity in diet and health. Annu Rev Nutr 2012;32:183–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolak JE, Esther CR, Jr, and O'Connell TM: Metabolomic analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from cystic fibrosis patients. Biomarkers 2009;14(1):55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabiano A, Gazzolo D, Zimmermann LJ, et al. : Metabolomic analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in preterm infants complicated by respiratory distress syndrome: Preliminary results. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24(Suppl 2):55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behrends V, Ryall B, Zlosnik JE, et al. : Metabolic adaptations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during cystic fibrosis chronic lung infections. Environ Microbiol 2012;15:398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laiakis EC, Morris GA, Fornace AJ, and Howie SR: Metabolomic analysis in severe childhood pneumonia in the Gambia, West Africa: Findings from a pilot study. PLoS One 2010;5(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slupsky CM, Rankin KN, Fu H, et al. : Pneumococcal pneumonia: Potential for diagnosis through a urinary metabolic profile. J Proteome Res 2009;8(12):5550–5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slupsky CM, Cheypesh A, Chao DV, et al. : Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia induce distinct metabolic responses. J Proteome Res 2009;8(6):3029–3036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghannoum MA, Mukherjee PK, Jurevic RJ, et al. : Metabolomics Reveals Differential Levels of Oral Metabolites in HIV-Infected Patients: Toward Novel Diagnostic Targets. OMICS 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wikoff WR, Pendyala G, Siuzdak G, and Fox HS: Metabolomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid reveals changes in phospholipase expression in the CNS of SIV-infected macaques. J Clin Invest 2008;118(7):2661–2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher AD, Cysique LA, Brew BJ, and Rae CD: Statistical integration of 1H NMR and MRS data from different biofluids and tissues enhances recovery of biological information from individuals with HIV-1 infection. J Proteome Res 2011;10(4):1737–1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Wang L, Guo GL, and Ma X: Metabolism-mediated drug interactions associated with ritonavir-boosted tipranavir in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 2010;38(5):871–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DH, Jarvis RM, Xu Y, et al. : Combining metabolic fingerprinting and footprinting to understand the phenotypic response of HPV16 E6 expressing cervical carcinoma cells exposed to the HIV anti-viral drug lopinavir. Analyst 2010;135(6):1235–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F, Lu J, Wang L, and Ma X: CYP3A-mediated generation of aldehyde and hydrazine in atazanavir metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos 2011;39(3):394–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JM, Strobel FH, Reed M, Pohl J, and Jones DP: A rapid LC-FTMS method for the analysis of cysteine, cystine and cysteine/cystine steady-state redox potential in human plasma. Clin Chim Acta 2008;396(1–2):43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, Gurney JG, et al. : The effect of acute alcohol intoxication and chronic alcohol abuse on outcome from trauma. JAMA 1993;270(1):51–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selzer ML, Vinokur A, and van RL: A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). J Stud Alcohol 1975;36(1):117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soltow Q, Strobel F, Mansfield K, et al. : High-performance metabolic profiling with dual chromatography-Fourier-transform mass spectrometry (DC-FTMS) for study of the exposome. Metabolomics 2011;9:132–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Want EJ, O'Maille G, Smith CA, et al. : Solvent-dependent metabolite distribution, clustering, and protein extraction for serum profiling with mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 2006;78(3):743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu T, Park Y, Johnson JM, and Jones DP: apLCMS—adaptive processing of high-resolution LC/MS data. Bioinformatics 2009;25(15):1930–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohl SM, Klein MS, Hochrein J, et al. : State-of-the art data normalization methods improve NMR-based metabolomic analysis. Metabolomics 2012;8(Suppl 1):146–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Park J, Lim MS, et al. : Quantile normalization approach for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomic data from healthy human volunteers. Anal Sci 2012;28(8):801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolker B, Bonebakker L, Gentleman R, Huber W, Liaw A, Lumley T, et al. : Gplots: Various R programming tools for plotting data. 2010. R package version 2.8.0.

- 30.Hu JZ, Rommereim DN, Minard KR, et al. : Metabolomics in lung inflammation: A high-resolution (1)h NMR study of mice exposed to silica dust. Toxicol Mech Methods 2008;18(5):385–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izquierdo-Garcia JL, Nin N, Ruiz-Cabello J, et al.: A metabolomic approach for diagnosis of experimental sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:2013–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandel J, Humbert N, Elhabiri M, et al. : Pyochelin, a siderophore of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Physicochemical characterization of the iron(III), copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes. Dalton Trans 2012;41(9):2820–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin LW, Reid DW, Sharples KJ, and Lamont IL: Pseudomonas siderophores in the sputum of patients with cystic fibrosis. Biometals 2011;24(6):1059–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Britigan BE, Rasmussen GT, and Cox CD: Augmentation of oxidant injury to human pulmonary epithelial cells by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyochelin. Infect Immun 1997;65(3):1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silkoff PE, Erzurum SC, Lundberg JO, et al. : ATS workshop proceedings: Exhaled nitric oxide and nitric oxide oxidative metabolism in exhaled breath condensate. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3(2):131–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carraro S, Giordano G, Reniero F, et al. : Asthma severity in childhood and metabolomic profiling of breath condensate. Allergy 2013;68(1):110–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de LG, Paris D, Melck D, et al.: Separating smoking-related diseases using NMR-based metabolomics of exhaled breath condensate. J Proteome Res 2013;12(3):1502–1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwai S, Fei M, Huang D, et al. : Oral and airway microbiota in HIV-infected pneumonia patients. J Clin Microbiol 2012;50(9):2995–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.