Abstract

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming requires sustained expression of multiple reprogramming factors for a limited period of time (10–30 days). Conventional iPSC reprogramming was achieved using lentiviral or simple retroviral vectors. Retroviral reprogramming has flaws of insertional mutagenesis, uncontrolled silencing, residual expression and re-activation of transgenes, and immunogenicity. To overcome these issues, various technologies were explored, including adenoviral vectors, protein transduction, RNA transfection, minicircle DNA, excisable PiggyBac (PB) transposon, Cre-lox excision system, negative-sense RNA replicon, positive-sense RNA replicon, Epstein-Barr virus-based episomal plasmids, and repeated transfections of plasmids. This review provides summaries of the main vectorologies and factor delivery systems used in current reprogramming protocols.

Introduction

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming (or factor reprogramming) is a technology used to convert differentiated somatic cells back to embryonic-stem-like cells via the ectopic expression of multiple transcription factors (usually four transcription factors) [1,2]. iPSC reprogramming is a long process, taking 10–30 days to complete. Such a long process and the requirement for multiple factors pose challenges to factor delivery. The major application of iPSCs is autologous cell therapy. However, conventional iPSC reprogramming employs integrating viral vectors (lentiviral and gamma retroviral) for delivery of reprogramming factors into reprogramming cells. Transgene integration has a risk of insertional mutagenesis [3]. In addition, the integrated reprogramming factors have residual expression in the established iPSC lines, which compromises the quality of iPSCs. The integrated reprogramming factors could be activated at any stage of differentiation and/or after transplantation of the iPSC-derived cells. This can be detrimental since all of the reprogramming factors are oncogenic to some extent with MYC as the strongest oncogene. Factor reprogramming also suffers from low efficiency and slow kinetics. Uncontrolled silencing of retroviral vectors (RVs) also compromises reprogramming efficiency and quality. Ever since the establishment of iPSC technology, great efforts have been invested in developing new approaches to address the various issues mentioned previously [4–6]. To achieve these goals, many distinct technologies are employed in current reprogramming protocols. These include nonintegrating adenoviral vectors [7], excisable PiggyBac (PB) transposon [8], excision of transgenes with the Cre-Lox system upon completion of reprogramming [9,10], repeated transfection with conventional plasmids [11], minicircle DNA [12], Epstein-Barr virus-based replicating episomal plasmids [4–6], protein transduction [13], mRNA transfection [14], negative-sense RNA vectors (Sendai viral vector) [15], positive-sense RNA vector/replicons [16], and the use of polycistrons mediated by 2A peptide [9,11], and/or Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) [4]. This review summarizes information relative to vector designs and factor delivery systems used in current reprogramming protocols. It is expected to be a supporting companion to the major survey of iPSC technologies in the same issue [17].

Retroviral Vectors

The so-called RV widely used in reprogramming and gene transfer/therapy is based on the simple gamma retrovirus of murine origin, largely the Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) [1,18–20]. The gamma RV (γ-RV) played a critical role in the development of iPSC technology due to its ability to provide relatively long-term transgene expression [1]. Retrovirus has an RNA genome that can be converted into a double-stranded DNA by its own reverse transcriptase. The DNA is subsequently integrated into the host genome to generate a heritable DNA provirus. The process of heritability includes the production of RNA genomes via transcription of the provirus DNA, packaging of RNA genomes into viral particles, infection via interaction between the viral envelope proteins and viral receptors on host cells, reverse transcription, generation of a double-stranded DNA, and finally its subsequent integration back into the host genome as a provirus [21]. The simple gamma retrovirus encodes only three genes: gag, pol, and env. During virion maturation, Gag protein is cleaved into matrix (MA), p12, capsid (CA), and nucleocapsid (NC) by the viral protease (PR). The Pol moiety of Gag-Pol is also cleaved to release free PR, reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN) [21,22]. An advanced replication-incompetent RV can be constructed with only the essential cis-acting elements, including the packaging signal, primer binding sequence (PBS), polypurine tract (PPT), and long terminal repeats (LTRs), but devoid of all of the viral protein-coding genes. Transgenes are inserted in place of the deleted viral structural genes. However, the viral structural proteins have to be provided in trans for efficient encapsidation, infection/transduction, reverse transcription, and integration. The transgenes integrated into the host genome are then transcribed and translated by the cellular machinery. The infectability of viral particles depends largely on the interaction of the viral envelope protein and the viral receptor on host cells [23,24]. We can change the vector tropism by pseudotyping the same RV system with different envelope proteins, and murine virus-based RVs can be ecotropic, amphotropic, or pantropic (or polytropic) depending on the envelope proteins used. Ecotropic vehicles transduce only rodent cells due to the strict requirement for the rodent ecotropic viral receptor mCAT1 (cationic amino acid transporter), but cannot transduce human cells although human cells do express an mCAT1 homolog that is 87% identical to the mouse counterpart [23,24]. With the sodium-dependent phosphate symporter (Ram1) as a viral receptor, amphotropic vehicles transduce cells of rodent, human, chicken, dog, cat, and mink. Pantropic vectors transduce an even wider range of cells. The widely used pantropic vectors are pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G). The VSV-G-pseudotyped virus enters cells through interaction with some mysterious ubiquitous cell membrane components [25], and thus is able to infect/transduce a wide variety of cell types, including cells of insects, fish, frogs, and humans. Recently, this ubiquitous VSV-G receptor was identified as the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) [26]. VSV-G pseudotyping not only broadens the tropism, but also increases the stability of viral particles and makes it possible to concentrate viral particles by ultracentrifugation [25]. Ecotropic and amphotropic retroviral particles are usually prepared using a packaging cell line that stably expresses the viral structural proteins Gag, Pol, and Env [27], but for pantropic virus, packaging is realized by transient cotransfection of the env gene and a transfer plasmid because of the cytotoxicity of VSV-G [25,28]. Like the wild-type retrovirus, M-MuLV-based RVs transduce only dividing cells [29,30], limiting their use in delivering reprogramming factors into nondividing and slow-dividing cells. Transgenes delivered by RVs are permanently integrated into host genomes, and thus provide stable expression of transgenes. Transgenes can be silenced depending on locations of integration (position effect), cell types, promoters installed, and viral cis-acting sequences. In embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and iPSCs, TRIM28/ZFP809 complex silences RV by binding to the viral PBS site, but not the HIV1-based lentiviral vectors [31,32]. Positional vector silencing in RVs and LVs may be alleviated by the incorporation of two classes of transcriptional regulatory elements: elements with boundary function, such as insulators and scaffold/matrix attachment regions, and elements that possess a dominant chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activating capacity, such as locus control regions and ubiquitous chromatin opening elements [33]. However, addition of these sequences impedes virus production because these elements are usually long. In addition, timely silencing might be beneficial to reprogramming [34], and transgene silencing provides a useful marker for complete reprogramming [35], although premature silencing is detrimental to reprogramming. Therefore, the best vector design to facilitate complete reprogramming should provide for relative long-term expression, while also allowing for timely silencing of the reprogramming factors.

HIV1-Based Lentiviral Vector

Lentiviral vectors were utilized to establish the first human iPSC line [2]. Lentiviral vectors have been developed from various viruses, including the equine infectious anemia virus (EIVA), bovine leukemia virus, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), foamy virus, and HIV2, but the most well-developed and widely used lentiviral vectors are based on HIV1 [36–39]. Like other lentiviruses, HIV1 is a complex retrovirus because it encodes additional regulatory (Tat and Rev) and accessory proteins (Vpr, Vpu, Vif, and Nef ) in addition to the common Gag, Pol, and Env proteins shared with simple retroviruses [40]. Development of lentiviral vectors is facilitated by knowledge of simple RVs. HIV1 vectors are constructed with HIV1 cis-acting sequences, including LTR sequences, packaging signal, PBS, central PPT, and Rev response element (Fig. 1). A non-HIV1 sequence, WPRE (woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element), is usually included to increase transgene expression (Fig. 1). One major goal in LV development is to increase safety since HIV1 causes human disease, and this is achieved by the following approaches: (1) deleting all of the viral-encoding genes from the transfer vector; (2) deleting some viral regulatory sequences in transfer vector, especially the enhancer and promoter in the U3 region of the 3′ LTR to make the vector replication incompetent (self-inactivating vector or SIN vector); (3) providing the essential viral proteins in trans from separate plasmids (split-genome approach); and (4) removing the packaging signal from the packaging plasmids; and (5) include nonviral heterologous promoters in the packaging plasmids [41]. Unlike RVs, HIV1 vectors require at least one regulatory viral protein, that is, Rev, in addition to Gag, Pol, and Env. HIV1 infects only a few types of cells (T cells, macrophages, and monocytes), and therefore the HIV1-based vectors with native envelopes have a very narrow tropism. Vector tropism can be broadened by pseudotyping with envelope proteins from various viruses, such as M-MuLV ecotropic and amphotropic Env glycoproteins, but the titer is generally low with these Env [37]. VSV-G can also pseudotype HIV1-based vectors, and gives the highest titer. The HIV1-based lentiviral vectors are usually packaged by transient cotransfection of all plasmids (transfer plasmids, packaging plasmids, and envelope plasmids) due to the toxic nature of some of the HIV1 proteins and VSV-G [42]. Inducible controlled expression of the viral packaging proteins makes it possible to package lentiviral vectors with a packaging cell line, but this method is not in wide use due to low titer and leaky expression of the toxic VSV-G and Rev [37,43,44]. In contrast to simple RVs, HIV1-based vectors can transduce nondividing and slow-dividing cells [45]. This is advantageous considering that somatic stem cells are better starting cells for reprogramming [3], but are generally slow growing or in quiescent states [46].

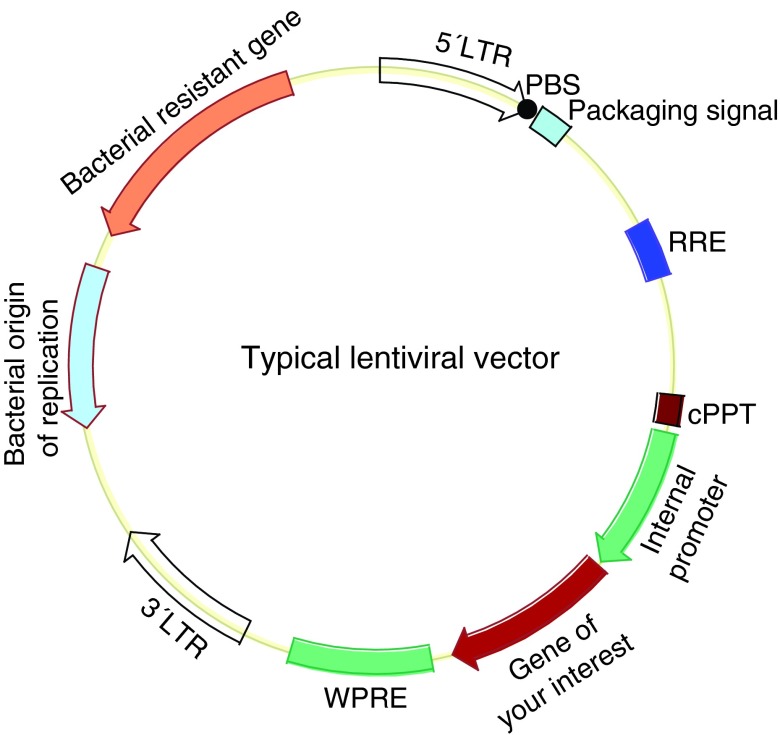

FIG. 1.

Schematic map of the transfer plasmid of lentiviral vector. cPPT, central polypurine tract (dark purple box); LTR, long terminal repeat (large open arrows); PBS, primer binding sequence (black dot); RRE, rev response element (blue box); WPRE, Woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (cyan box). Other major components are annotated in the figure. Figure is not drawn to proportion. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Minicircle DNA

Minicircle vectors were used to establish footprint-free iPSC lines because of their episomal nature and low degree of vector silencing [12]. Minicircle refers to episomal supercoiled circular DNA with only mammalian expression cassette and devoid of the bacterial backbone (Fig. 2). Bacterial DNA sequences (origin of replication, resistant gene, and others) in a mammalian expression construct are found to be largely responsible for the dramatic silencing of the delivered transgenes [47], and therefore systems have been developed to generate circular DNA (minicircle) containing the mammalian expression cassette only, and devoid of the bacterial backbone, using controlled, inducible intramolecular site-specific recombination in bacterial hosts prior to harvest of minicircles from bacterial cultures [48]. Central to these technologies is intramolecular site-specific recombination. Intramolecular recombination can be realized via different recombinases, including Streptomyces phage integrase ΦC31 [48,49], the Cre recombinase from bacteriophage P1 [50], FLP recombinase from the yeast plasmid 2 μm circle [51], and the ParA resolvase from the multimer resolution system of the broad host-range plasmid RK2 or RP4 [52]. The resulting minicircles can be purified by cesium gradient centrifugation after the selective destruction of bacterial backbone plasmids (miniplasmid) and of the residual parental plasmids by enzymatic restriction. This enzymatic removal of miniplasmids and residual parental plasmids is costly and labor intensive. Recently, a simple system was developed in which the miniplasmids and parental plasmids can be destroyed in vivo shortly after recombination by incorporating tandem repeats of the recognition sequence for yeast I-SceI outside of the recombination sites, in a genetically modified Escherichia coli strain that harbors inducible I-SceI genes and ΦC31 integrase (Fig. 2). This leaves only minicircles in the host cells, and allows for their simple purification using standard maxipreps or minipreps [49] (Fig. 2). Minicircles can also be purified using protein–DNA interaction chromatography [52]. Minicircles are generally nonreplicating, but a replicating minicircle was reported [51].

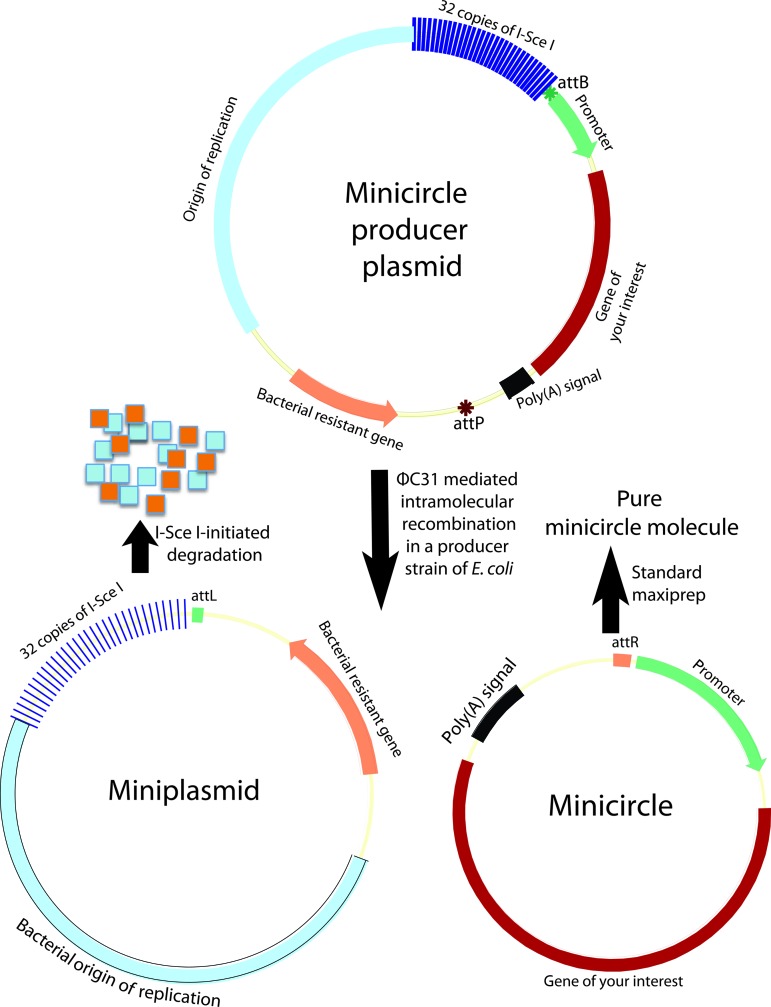

FIG. 2.

Minicircle generation system. Producer plasmid undergoes intramolecular recombination in an Escherichia coli strain that harbors the inducible ΦC31 and the rare-cut I-Sce I genes. The resulting miniplasmid of bacterial backbone is degraded by I-SceI-initiated digestion of DNA since this plasmid contains 32 copies of I-SceI recognition sequences. The second recombination product, the minicircle DNA, remains intact in the bacterial host, and can simply be purified using standard maxiprep or miniprep. attB, bacterial attachment (green star); attP, phage attachment (ochre red star). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Protein Transduction

Protein transduction is a technology to deliver exogenous proteins into cells in culture or directly into tissues of living organisms [53–57]. Owing to their apparent lack of genome integration property, these technologies were used to generate footprint-free iPSCs [13,58]. Delivery of proteins into cells encounters a great barrier, the hydrophobic cellular membrane. The most widely used method is transduction mediated by a protein transduction domain (PTD; also called cell-penetrating peptide, CPP). PTD occurs naturally in many proteins, such as the HIV1 transcriptional activator TAT [59–61], the structural protein VP22 of herpes simplex virus type 1 [62], and the Drosophila transcription factor antennapedia (AntP) [63,64]. These PTDs are fused onto proteins of interest for transduction. The mechanism of PTD-mediated transduction is poorly understood, but it might involve interaction between PTD and the cell membrane, endocytosis, and retrograde transportation into the cytoplasm and nucleus [54]. PTD is a highly basic domain containing a large portion of arginines, so the positively charged PTD can interact with the negatively charged components of the cell membrane via electrostatic interaction. Further internalization of the PTD involves different endocytotic pathways (macropinocytosis, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and caveolin-mediated endocytosis) although previous data suggested that this process is independent of endocytosis, energy, and specific receptors [65,66]. PTD-mediated protein transduction can occur in many different cell types, including hard-to-transfect cells such as neural cells [63], and it delivers large proteins into all tissues in live animals including brain indicative of an ability to cross the blood-brain barrier [67]. One drawback is the short half-life of the transduced protein in cells. It is found that poly-arginine (around eight arginines) transduced the tagged proteins more efficiently than the naturally occurring PTDs [68]. PTD-mediated transduction is fast. In contrast to other delivery systems such as virus-mediated gene delivery, PTD-mediated protein transduction is not toxic to cells [61,68]. PTD not only delivers protein, it can also deliver DNA, RNA, nanoparticles, liposomes, fluorescence probes, and drugs [57]. PTD has a large cargo capacity and can deliver protein >100 kDa [67].

PTD-mediated protein transduction is an active process. Proteins can also be delivered passively into living cells by diffusion through the cell membrane temporarily opened using mechanical approaches or membrane-permeabilizing agents. One example of mechanical approaches is scrape loading [59]. The commonly used membrane permeabilizing agent is streptolysin O, which is a cholesterol-binding, thiol-activated, calcium-sensitive bacterial exotoxin that stimulates the formation of pores in the plasma membrane of mammalian cells up to the size of 35 nm that is large enough for large proteins to traverse but too small for organelles to escape [69–71]. When permeabilizing conditions are optimized, the process is reversible under optimal re-sealing conditions, and the treated cells will remain viable and normal [70]. In one protein reprogramming experiment, the reprogramming factors in ESC extracts were delivered into the reprogramming cells temporarily permeabilized using streptolysin O [71].

Sendai Viral Vectors

Sendai virus is an enveloped, nonsegmented, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA virus of the Paramyxoviridae family [72]. The RNA viral genome is 15,384 nucleotides, which consists of six independent cistrons (NP, P/C/V, M, F, HN, and L) encoding six essential proteins—nucleoprotein (NP), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), fusion protein (F), hemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN), and large protein (L, the catalytic subunit of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase)—and two accessory proteins, C and V proteins. L is believed to possess all of the enzymatic activities necessary for viral transcription and replication. Genomic RNA, NP, P, and L form the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) that is a minimal functional unit in terms of genome replication and viral mRNA transcription after entering host cells. Unlike retroviruses, Sendai virus has no DNA phase, and therefore generally does not integrate into host genomes. This property has been employed to produce iPSC lines free of transgene footprints [15]. Replication and transcription are completed in the host cytoplasm and need no host nuclear factors. The only cis-element required for gene transcription is a short gene-start signal (UCCCNNUUUC) before each cistron, and a short gene-end signal (AUUCUUUUU) at the end of each cistron. Like their parent viruses, SeV vectors (SeVVs) in the form of RNP replicate and transcribe in the cytoplasm of host cells, without going through a DNA phase. This ability of RNP replication in the transduced cells ensures lasting expression of the reprogramming factors for complete reprogramming. The first-generation SeVV contains the entire viral genome with foreign genes inserted into seven possible locations, and is therefore an infectious vector [73,74]. The second generation of vectors deletes one of the three envelope-related genes to make the vector incompetent and less immunogenic [73]. Most advanced vectors delete all of the three envelope genes and modify the remaining genes and sequences [75,76]. The F-deficient nontransmissible vector (SeVV/ΔF) was developed by deleting the envelope fusion gene (F gene) from the RNA genome [77]. The F protein is provided in trans from a packaging cell line. Such an F-deficient vector cannot form intact infectious viral particles, yet can replicate and transcribe in the cytoplasm of host cells, so as to provide persistent transgene expression. But F-deficient vectors can generate significant amounts of virus-like particles, and such virus-like particles have residual infection activity [76]. For enhanced safety, formation of virus-like particles from the transfected host cells was significantly reduced by introducing temperature-sensitive mutations into the two remaining envelope-related genes M and HN in the context of ΔF (SeVV/MtsHNtsΔF vector) [78]. The most advanced SeVV incapable of forming any viral particles was developed by deleting all three of the structural genes (M, F, and HN) from the viral genome [75]. The efficiency of this triple-deficient vector is enhanced by incorporating missense mutations in the P and L genes, and by introduction of gene-end signal before NP gene, which enable a stable gene expression and avoid IFNβ induction (SeVV/ΔMΔFΔHN vector) [76]. SeVV/ΔMΔFΔHN virion particles are packaged in a cell line expressing M, F, and HN. Like Sendai virus, SeVV/ΔMΔFΔHN vectors transduce a wide range of cells from avian to human because SeVV recognizes ubiquitous sialic acids as its primary receptor. Three exogenous genes can be installed in place of M, F, and HN. Additional transgenes can be incorporated by the introduction of gene-start and gene-end signals. Therefore, in the SeVV/ΔMΔFΔHN vector, all of the four reprogramming factors can be installed on a single vector [76], while with the SeV/ΔF vector, four individual viruses are needed to deliver the four reprogramming factors [79]. Viral replication relies on an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and therefore siRNA against the L gene can actively clear viral replicons from transduced cells when there is no longer a need for transgene expression following the completion of reprogramming [76]. After reprogramming, viral replicons can also be cleared by a short temperature shift if ts mutations are introduced into the viral RNA polymerase gene of the vector [79]. Viral replicons become diluted over cell divisions, and some iPSCs eventually become devoid of viral replicons after sequential passaging, and so cells free of viral replicons can be passively obtained by negative selection against virus-containing iPSCs using an antibody against the spike protein HN when the HN gene is included in the vector [80].

RNA Transfection

RNA can be directly delivered into cultured cells or animals as an alternative to DNA and protein [81,82]. In contrast to DNA delivery, the destination of mRNA is the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus, and more genetic information can reach the target sites quicker due to reduced barriers during transfection because the inefficient nuclear internalization of transgenes is eliminated, and a shorter transport in cytoplasm will be needed [83]. mRNA can be translated almost instantly while DNA needs an additional transcription step. Expression of genes delivered in the form of DNA is frequently silenced by epigenetic modification while that of RNA is not. RNA does not modify the host genome while DNA frequently does, and therefore RNA-based therapy is classified as a nongene therapy approach [84]. It is this feature of nongenome modification that makes synthetic mRNA appealing in the establishment of footprint-free iPSC lines. However, mRNA transfection has two major drawbacks. First, the half-life of RNA is short and the expression of the delivered mRNA is more transient compared to that of the delivered DNA, limiting its use in a long process like reprogramming. Second, RNAs are more immunogenic than DNA, and cause strong innate immune responses through the antiviral mechanisms of the host cells, thus introducing complications in reprogramming. Modifications of synthetic mRNA can substantially reduce immune responses from transfected cells [14,81], and are essential for efficient transgene expression and reprogramming [85]. A combination of modifications to mRNAs allows for robust expression of the transfected mRNAs. Essential or beneficial modifications include inclusion of 5′- and 3′-UTRs of β-globin, addition of a poly(A) tail, capping with the antireverse cap analog, dephosphorylation of the uncapped population of the synthesized mRNAs, and incorporation of modified ribonucleoside bases such as pseudouridine [81,82]. Even with these modifications, reprogramming with synthetic mRNAs is not an easy task.

Epstein-Barr Virus Episomal Vectors

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) episomal vector used widely in reprogramming is an Epstein-Barr virus–based plasmid that can replicate and partition extrachromosomally in primate cells [86–88]. The ability to replicate in cells allows its use in a long process as reprogramming [4]. EBV vectors require only two components of viral origin, the cis-element OriP and the trans-acting factor EBNA1 [89,90]. EBNA1 encodes the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1). OriP is a 1.7-kb DNA region containing two essential cis-acting sequences for plasmid replication and retention, namely, the family of repeat (FR), and the region of dyad symmetry (DS; also named origin of bidirectional DNA replication, OBR) [91]. FR functions to maintain the plasmids, and consists of 20 tandem imperfect copies of a 30-bp repeating unit, each of which contains an EBNA1 binding site. FR is also an EBNA1-dependent transcription enhancer. DS is a plasmid replicator, and contains four EBNA1 binding sites [92]. EBNA1 binds to both FR and DS for proper plasmid replication and retention. EBV plasmids rely on host for replication and retention because EBNA1 does not have any enzyme activity except for DNA binding capacity. EBV plasmids replicate once per cell cycle in synchrony with the host chromosomes, and have a low mutation rate compared with BPV- or SV40-based plasmids. Partitioning of EBV plasmids does not seem to be random, but the retention mechanism of the EBV vector is imperfect, resulting in a slow loss of plasmids at around 5% each cell cycle if the selection pressure is removed [93]. This feature was employed to generate footprint-free iPSCs [4–6]. Unlike other episomal circular DNA viruses, EBV has a large genome of 172 kb, and therefore EBV vectors can accommodate a large DNA fragment. EBV-based vectors work mainly in primate cells, and are reported not to persist in rodent cells although one group reported that some rodent cell lines supported the long-term maintenance of EBV vectors [94].

2A Peptides and IRES for Construction of Polycistron Vectors

IRES and 2A peptides are two popular means for achieving the coexpression of multiple genes (Fig. 3) among other approaches, such as the utilization of multiple promoters and fusion proteins [95]. 2A is a short peptide (18–22 amino acids) that mediates the coexpression of two proteins from a single open reading frame (ORF) [95–97]. The upstream protein terminates at the 2A terminal glycine in a fashion independent of the traditional stop codon, and the downstream protein initiates at a proline independent of the initiation codon. The 2A-peptide-mediated coexpression of transgenes has gained popularity recently due to its small size, efficiency, stoichiometry, and availability of various functional variants. Its small size is an invaluable feature in terms of constructing reprogramming vectors due to the need to assemble four genes into a single vector. The use of 2A variants can avoid potential intramolecular homologous recombination of polycistrons, and allows for the expression of multiple genes (up to five genes). There are four widely used 2A sequences, which are derived from the foot-and-mouth disease virus (F2A), porcine teschovirus-1 (P2A), Thoseaasigna virus (T2A), and equine rhinitis A virus (E2A), with P2A as the most effective one [98]. 2A is active in all eukaryotic cells [99], but not in prokaryotes [100]. 2A sequences (54–66 bp) are short compared to IRES and internal promoters, and therefore provide an advantage in vector design because of the limited packaging capacity of the widely used lentiviral vectors and RVs. The following two points should be kept in mind when 2A peptides are used for the construction of polycistronic vectors. First, there is still an imbalance of expression between proteins upstream and downstream of 2A, with the upstream protein being translated at a higher level, although this imbalance is not as severe as with IRES; second, the resulting N-terminal protein retains a 2A peptide and the spacer GSG if included during vector construction, while the C-terminal protein retains an extra proline at its very N terminus.

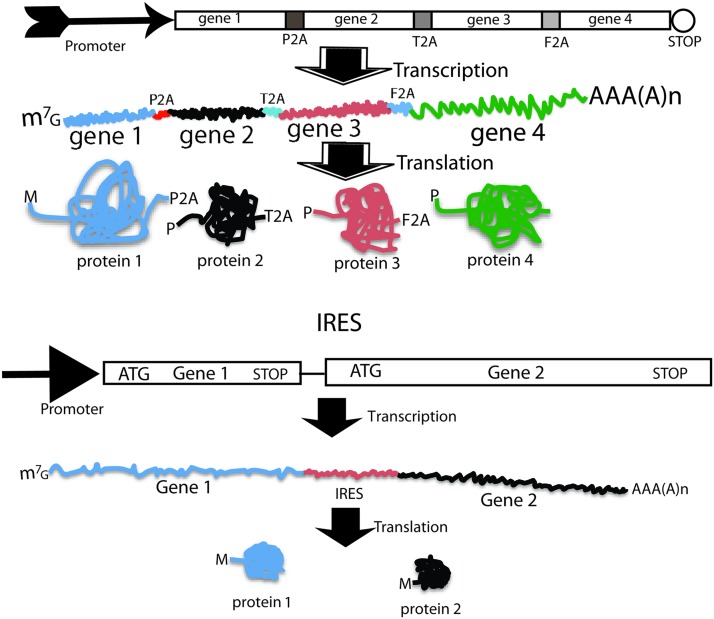

FIG. 3.

Coexpression mediated by 2A peptide and IRES. Upper panel: 2A-mediated coexpression of four genes into four individual proteins from a single ORF. Upper part is the eukaryotic expression cassette; middle is the resulting mRNA, and the bottom is the resulting four individual proteins. Lower panel: IRES-mediated coexpression of two genes into two individual proteins from two separate ORFs of the same mRNA. ORF, open reading frame. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

IRES is a stretch of highly structured RNA of about 450 nts that directs a cap-independent initiation of protein synthesis from a downstream coding RNA [101–104]. This property is employed to design dicistronic expression cassette under the control of a single promoter in which the first cistron is translated by a canonical cap-dependent initiation, but the second cistron is translated via IRES-mediated internal initiation of translation. In dicistronic vectors, the cistron downstream of IRES usually has a lower level of expression (6%–100% that of the upstream gene) [105]. Utilization of IRES and 2A for coexpression requires different vector design consideration. The stop codon of the first gene in the 2A vector should be removed and the two cistrons linked by 2A should be in-frame to form a single ORF, while the stop codon of the first cistron should be retained in the IRES vectors and IRES connects two distinct ORFs. There are two limitations to IRES-mediated coexpression: (1) IRES is long, and this is a negative attribute when vector capacity is limited as in RVs; (2) the expression of the second gene is compromised. Thus, IRES is less popular in reprogramming constructs.

PiggyBac Transposon and Vectors

PB is a nonviral 2,472-bp DNA transposon isolated from the cabbage looper moth. PB transposes in a wide range of host genomes from yeast to human [106–108]. The PB transposon consists of 3′ and 5′ terminal repeat domains (TRDs) and an ORF encoding the PB transposase, the former of which delimit the transposon cassette for integration. Both the 3′ and 5′ TRDs contain a 13-bp terminal inverted repeat and a 19-bp internal inverted repeat. The 3′ TRD has a 31-bp spacer while the 5′ TRD spacer is only 3-bp long. In the PB vector system, the PB transposase can be provided in trans, and a transgene expression cassette is sandwiched between the two TRDs in place of the native PB transposase [109–111]. A typical PB gene delivery system therefore includes a helper plasmid to express the PB transposase, and a transposon donor plasmid in which the two cis-acting TRDs enclose a transgene expression cassette. PB transposition follows a cut-and-paste mechanism, and the transgene cassette is integrated into genomes at TTAA sites. The PB transposition process initiates with nicking at the transposon 3′ end, and includes hairpin formation between the transposon 5′-end-TTAA overhang and its 3′ OH, hairpin resolution, target joining, and target repair [110]. The PB transposase is solely responsible for catalyzing all of these processes. Unlike transpositions with other DDE family recombinases, PB transposition does not require DNA synthesis, and results in the precise excision of transposon from the host DNA due to the tetranucleotide cohesive overhang (TTAA) left behind on both the flanking host DNA and the transposon ends, which can undergo a footprint-free repair through a simple process of TTAA base pairing and ligation [110]. Although TRDs are sufficient for interplasmid transposition, efficient genome transposition requires internal sequences adjacent to both the 5′ and 3′ internal inverted repeats [112]. The integrated expression cassette together with the transposon terminal elements can be precisely excised by transient expression of the reintroduced PB transposase. This excision process leaves no footprint behind. PB vectors constitute a nonviral, genome-integrating gene delivery system representing a cheaper and simpler approach than viral systems. They also have a much larger cargo capacity than retroviral systems. PB transposons have the highest transposition efficiency among DNA transposons, but still give a significantly lower rate of stable transposition (integration rate) compared to viral vectors [111]. These features allow the use of PB vectors to generate footprint-free iPSCs [8,113].

Adenoviral Vectors

Adenoviral vectors are the second most widely used vectors in clinical trials after RVs owing to their high capacity for transgene insertion, high virus yield, efficient transduction into a wide range of cells, and higher safety profile than integrating vectors [114]. Adenovirus is a nonenveloped double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid. The genome is a nonsegmented linear DNA with a viral terminal protein covalently attached to each 5′ terminus of both viral ends at the two inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). The genome encodes two groups of overlapping genes on both strands, the early (E1 to E4) and the late genes (L1 to L5), which are expressed before and after replication of the viral genome, respectively [114,115]. Each gene gives rise to multiple protein products through alternative splicing. Adenoviral vectors are mostly based on the two well-characterized human adenoviruses: Ad2 and Ad5 [115–117]. The development of adenoviral vectors has roughly three generations [118]. The first generation of vectors has E1 deleted to make virus replication incompetent, because E1 is responsible for the activation of both the early and the late viral genes, and thus for viral replication [117] (Fig. 4). The E1 function in the first-generation vector is provided in trans from a complementary packaging cell line, which is usually HEK293 transformed with the adenovirus E1 region. Some first-generation vectors are also devoid of the E3 gene to make more room for transgene insertion. The first-generation vector can accommodate up to 8.2 kb of exogenous sequence. Two issues with the first-generation vectors are the presence of some replication competent adenoviruses (RCAs), and immune responses from the transduced cells and/or tissue/animals. The second-generation vectors have part or all of their E2 and E4 genes deleted in addition to the E1 and E3 deletions (Fig. 4). These additional deletions have threefold benefits: reduced RCAs, reduced immune response, and additional room (up to 14 kb) for transgene insertion. The last generation of adenoviral vectors (also known as gutless vectors, gutted vectors, or helper-dependent Ad vectors) is devoid of all viral genes, leaving just the two ITRs and the packaging signal, so as to reduce vector toxicity and immunogenicity, and to make more room for transgene insertion [118] (Fig. 4). With most of the 36-kb sequence of the genome deleted, the gutless vector can accommodate up to 37 kb of foreign sequences without compromising viral growth and titer. A helper virus is needed for the gutless vector because it is not possible to establish a complementary cell line due to toxicity of some viral proteins and the need for a high level of viral proteins for viral packaging. Like lentiviral vectors, adenoviral vectors transduce both dividing and nondividing cells. Relevant to reprogramming is that adenoviral vectors are largely episomal because adenovirus exists as an extrachromosomal entity. A shortcoming associated with this feature is the short-term expression of transgenes compared with the integrating LVs and RVs. This transient nature of transgene expression makes the efficiency of adenoviral reprogramming extremely low [7]. Adenoviral vectors also have a high level of background integration [119], and this constitutes a concern when these vectors are employed to generate footprint-free iPSCs for clinical application. Adenoviral constructs can be difficult to clone due to their large size [117].

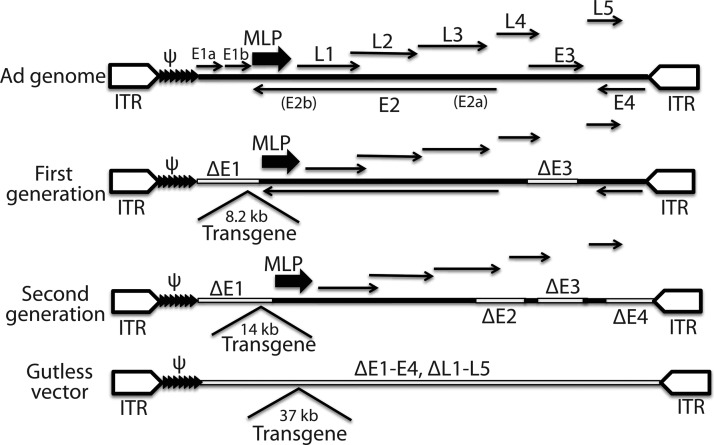

FIG. 4.

Genome structure of the adenoviral vectors of the three generations along with that of the wild-type Ad genome. ψ, packaging signal (tandem filled triangles); Δ indicates deletion of genes; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; MLP, major late promoter (large arrows); thick lines represent viral sequences; open boxes denote deletion of viral sequences; thin arrows indicate viral genes and their direction of transcription; open pentagons are ITRs. Numbers are insertion capacity of transgenes.

Alphaviral Vectors and RNA Replicon

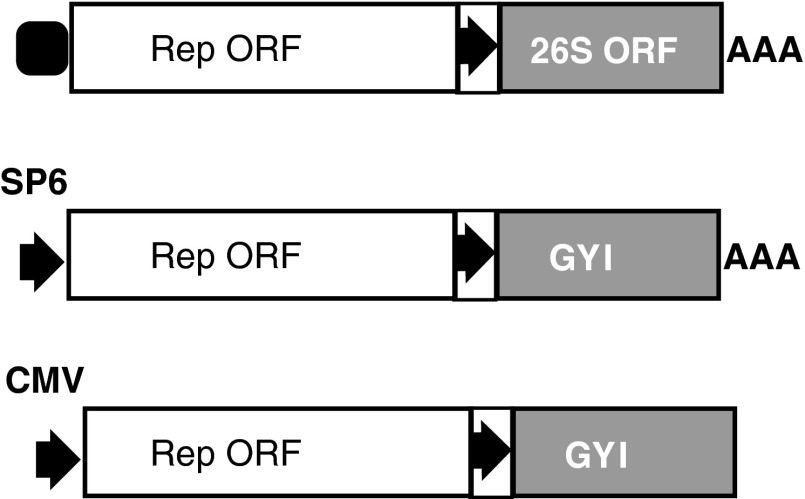

Alphavirus is an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense, capped, and polyadenylated RNA virus with a genome of about 11,700 nucleotides [120]. Well-known alphaviruses for vector design include the Sindbis virus (SIN), Semliki forest virus (SFV), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEE). The alphaviral genomes include two ORFs (nonstructural ORF and structural ORF), both of which encode polyproteins (Fig. 5). The 5′ nonstructural ORF encodes a polyprotein that generally gives rise to four nonstructural proteins (or replicase proteins, nsP1 to nsP4) and some cleavage intermediates. These proteins function mainly as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and therefore this ORF is considered an RNA replicase/transcriptase gene (Rep). The structural ORF (26S ORF) encodes structural proteins: three main structural proteins [C (capsid), E1, and E2] and two minor structural proteins (E3 and 6K). E2 and E3 are products of a precursor protein, PE2. Genomic RNA serves as the direct template for translation of the nonstructural proteins, and as the template for synthesis of the negative-strand RNAs: (−)RNA. (−)RNA is an exact complement of the genomic RNA except for the presence of an unpaired G at its 3′ end. (−)RNA serves as the template for synthesis of new genomic RNAs, and also as the template for transcription of the 26S mRNA under the direction of the subgenomic 26S promoter. The 26S mRNA is capped and polyadenylated, and serves as the template for translation of the structural proteins. Structural proteins are not required for synthesis of the (−)RNA, replication of the (+)RNA, and the cytoplasmic transcription of the 26S mRNA. Therefore, an RNA genome deleted of the structural ORF can replicate in cells (RNA replicon), but is not infectious. Alphaviral vectors can be infectious and noninfectious. Infectious vector is made by insertion of transgenes into the complete genome before or after the structural ORF with the inclusion of an additional subgenomic promoter [121]. A noninfectious vector is made possible by replacing the structural ORF with transgene-coding sequences [122]. Noninfectious vectors can be packaged into virions when the structural proteins are provided in trans. Noninfectious RNA replicons can be delivered directly into cells as RNAs synthesized in vitro using SP6 or T7 promoters (Fig. 5). Such synthetic, noninfectious RNA replicons encoding the reprogramming factors were recently used to generate footprint-free iPSCs [16]. DNA-based alphaviral vectors are reported [123–125]. In this case, RNA replicons are transcribed from conventional plasmids in the nuclei of the transfected cells using a eukaryotic promoter, such as the CMV or RSV promoters (Fig. 5). The RNA replicons are then exported from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where they can undergo translation of replicase, (−)RNA synthesis, and transgene transcription and translation. Alphaviral vectors pose no risk of integration into the host genome, a desired feature for the generation of footprint-free iPSC lines. However, alphaviral vectors are highly cytopathic, and host cells die in a few days postinfection. Point mutations in the 5′ UTR and in the nsP2 protein can alleviate the cytopathic effect of alphaviral vectors by slowing down the replication of RNA replicons [126,127].

FIG. 5.

Alphaviral vectors. Upper: structure of an alphaviral genome. Middle: alphaviral vector design for in vitro preparation of RNA replicon (noninfectious) using SP6 promoter. Lower: alphaviral plasmid design for in vivo generation of RNA replicons via a eukaryotic promoter. Open box, nonstructural ORF of the alphaviral genome; gray box, structural ORF of an alphaviral genome; arrow in a box, the alphaviral subgenomic promoter; arrows, SP6 or CMV promoters; filled rounded square, RNA cap.

Concluding Remarks

Factor reprogramming requires sustained expression of the four reprogramming factors for ∼10–30 days. After reprogramming, transgene expression and retention are detrimental or pose potential risks [128]. Lentiviral and simple RVs provide sustained expression of transgenes, and transgenes are silenced in the reprogrammed pluripotent cells. However, the silencing process can occur at undesirable points in time, either too early or too late. In addition, RVs integrate into the reprogrammed genomes, posing risks of insertional mutagenesis, and residual expression and reactivation of the transgenes. Many nonintegrating approaches (protein transduction, RNA transfection, transient transfection, minicircle, and episomal plasmids) generally cannot support sustained expression of transgenes and suffer from low efficiencies of reprogramming. Alphaviral vectors are theoretically ideal reprogramming vehicles, but their strong cytopathic effects compromise their values. Sendai viral vectors might meet the complex requirements for factor reprogramming owing to their nonintegrating nature, self-replicating property, controllable removal of viral replicons, relatively low toxicity, and the ability to accommodate multiple exogenous genes. Despite their relatively low reprogramming efficiency, EBV-based episomal plasmids are currently a feasible vehicle choice due to their simplicity, self-replicating nature, nonintegrating property, low immunogenicity, and low toxicity. There might be some stones left unturned, and a more efficient, safer, and nonintegrating reprogramming approach could be developed in the future using some novel transgene vectors or factor delivery systems.

Glossary

Transduction: a gene transfer process in which replication-incompetent viral particles “infect” cells or tissues in vivo or in vitro. This term distinguishes itself from a normal viral infection by any replication-competent virus in which viruses invade cells and/or tissues, and subsequently replicate inside the host cells and spread to neighboring cells or tissues. Transduction also refers to the process of protein delivery into cells.

Packaging signal: a region in a viral chromosome that is essential for the efficient packaging of viral genomes.

Acknowledgments

The author's research is supported by UAB new faculty development fund. The author thanks Dr. Kevin Pawlik for his critical reading. He also appreciates the critical reviews by the two anonymous reviewers. Their inputs made Table 1 and other improvements in this contribution possible.

Table 1.

Comparison of Different Vectors and Factor Delivery Systems in Reprogramming

| Vector/delivery | System components | Features | Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviral vector | Ecotropic & amphotropic | M-MuLV-based transfer plasmid, transgenic packaging cell lines | Three different tropisms, genome integrating, self-inactivating vector, transduce dividing cells only | Lasting expression, consistent and reliable reprogramming | Insertional mutagenesis, residual expression and reactivation of transgenes, premature silencing, limited tropisms, biohazard process, multiple transduction, unstable viral stocks, immunogenic | |

| Pantropic | M-MuLV-based transfer plasmid, VSV-G envelope plasmid, transgenic packaging cell lines (no envelope genes) | |||||

| Lentiviral vector | HIV1-based transfer plasmid, packaging plasmids, VSV-G envelope plasmid, general packaging cells (293T) | Genome integrating, VSV-G pseudotyped, Self-inactivating vector, transduce dividing and nondividing cells | Lasting transgene expression, reliable and consistent reprogramming, wide tropisms | Insertional mutagenesis, residual expression and reactivation of transgenes, immunogenic, biohazard process | ||

| Minicircle | Transgenic bacterial producer strain, producer plasmids | Circular DNA molecule, only mammalian expression cassette, no bacterial plasmid sequence, nongenome integrating | Low transgene silencing, no insertional mutagenesis, less immunogenic | Still transient expression, extremely low reprogramming efficiency, random integration, extra step for minicircle preparation | ||

| Protein transduction | Expression plasmids (bacterial or mammalian) | Absolute nongenome integrating | No insertional mutagenesis | Extremely low reprogramming efficiency, multiple transduction, short actions of reprogramming factors | ||

| Sendai viral vectors | Vector plasmids, packaging plasmids, packaging cell lines and virus propagating cell lines | Nongenome integrating, replicating RNA replicon, no DNA phase, cytoplasmic | No insertional mutagenesis, lasting transgene expression, high reprogramming efficiency | Extra steps for viral clearance, expensive, biohazard process, immunogenic | ||

| RNA transfection | In vitro synthesis system | Nongenome integrating | No insertional mutagenesis | Very transient, multiple transfection, very low reprogramming efficiency, highly immunogenic | ||

| Episomal vectors | EBV-based plasmid (OriP and EBNA-1 genes) | Sustained transgene expression, plasmid replicating and partitioning in primate cells | No insertional mutagenesis, single transfection, simple, inexpensive, less immunogenic, plasmid loss upon completion of reprogramming | Low reprogramming efficiency, random integrations, transgene silencing, imperfect partitioning of plasmids, do not replicate in rodent cells | ||

| Coexpression | 2A | 2A-coding sequences | 54–66 bp, one mRNA with a single ORF encoding multiple individual proteins | Efficient and balanced coexpression, mediate coexpression up to five transgenes | Imbalanced expression reported | |

| IRES | IRES sequence | Around 450 bases, one mRNA with separate ORFs | Coexpression of two genes under a single promoter | Mediate coexpression of only two genes, low expression of the second transgene | ||

| PiggyBac vectors | Transposon plasmids, transposase plasmids (helper plasmids) | Genome integrating, precise excision of the integrated transposons | Lasting expression of transgenes, low immunogenic | Low integration rate compared to viral vectors, random integration of helper plasmids, extra work on transgene excision and screening | ||

| Adenoviral vectors | Transgene constructs, packaging cell lines, helper virus | Nongenome integrating (extrachromosomal), high cloning capacity, transduce dividing and nondividing cells | No insertional mutagenesis | Low reprogramming efficiency, high background integration, transient transgene expression, high titer required, biohazard process | ||

| Alphaviral vectors and RNA replicon | Synthetic replicon RNA, or plasmid encoding RNA replicon | Nongenome integrating, cytoplasmic, no DNA phase | No insertional mutagenesis, lasting transgene expression | Highly cytopathic, high cost for in vitro preparation of RNA replicons, highly immunogenic | ||

Author Disclosure Statement

The author declares no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Takahashi K. and Yamanaka S. (2006). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318:1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu K. and Slukvin I. (2012). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from umbilical cord blood. In: Encyclopedia of Molecular Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine: Stem Cells. Meyers RA, ed. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA., pp 1–25 DOI: 10.1002/3527600906.mcb.201200006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, Tian S, Stewart R, Slukvin II. and Thomson JA. (2009). Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science 324:797–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu K, Yu J, Suknuntha K, Tian S, Montgomery K, Choi KD, Stewart R, Thomson JA. and Slukvin II. (2011). Efficient generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent stem cells from normal and neoplastic bone marrow and cord blood mononuclear cells. Blood 117:e109–e119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu K. and Slukvin I. (2013). Generation of transgene-free iPSC lines from human normal and neoplastic blood cells using episomal vectors. Methods Mol Biol 997:163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, Weir G. and Hochedlinger K. (2008). Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science 322:945–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hamalainen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu P, et al. (2009). piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 458:766–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaji K, Norrby K, Paca A, Mileikovsky M, Mohseni P. and Woltjen K. (2009). Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature 458:771–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CW, Lai YS, Pawlik KM, Liu K, Sun CW, Li C, Schoeb TR. and Townes TM. (2009). Polycistronic lentiviral vector for “Hit and Run”. reprogramming of adult skin fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 27:1042–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hong HJ, Ichisaka T. and Yamanaka S. (2008). Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science 322:949–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, Gupta DM, Huang M, Li Z, Panetta NJ, Chen ZY, Robbins RC, et al. (2010). A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods 7:197–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou HY, Wu SL, Joo JY, Zhu SY, Han DW, Lin TX, Trauger S, Bien G, Yao S, et al. (2009). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell 4:381–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, et al. (2010). Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell 7:618–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seki T, Yuasa S, Oda M, Egashira T, Yae K, Kusumoto D, Nakata H, Tohyama S, Hashimoto H, et al. (2010). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell 7:11–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka N, Gros E, Li HR, Kumar S, Deacon DC, Maron C, Muotri AR, Chi NC, Fu XD, Yu BD. and Dowdy SF. (2013). Efficient generation of human iPSCs by a synthetic self-replicative RNA. Cell Stem Cell 13:246–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu K. (2014). All roads lead to the induced pluripotent stem cells: the technologies of iPSC generation. Stem Cells Dev [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1089/scd.2013.0620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walther W. and Stein U. (2000). Viral vectors for gene transfer: a review of their use in the treatment of human diseases. Drugs 60:249–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cepko C. and Pear W. (1996). Overview of the retrovirus transduction system. In: Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., USA, pp 9.9.1–9.9.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K. and Yamanaka S. (2007). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goff SP. (2007). Retroviridea: The Retroviruses and Their Replication. In: Fields' Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Tolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, pp 1999–2069 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rein A. (2011). Murine leukemia viruses: objects and organisms. Adv Virol 2011:403419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller AD. (1996). Cell-surface receptors for retroviruses and implications for gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:11407–11413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss RA. and Tailor CS. (1995). Retrovirus receptors. Cell 82:531–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedmann T. and Yee JK. (1995). Pseudotyped retroviral vectors for studies of human gene-therapy. Nat Med 1:275–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelshtein D, Werman A, Novick D, Barak S. and Rubinstein M. (2013). LDL receptor and its family members serve as the cellular receptors for vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:7306–7311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morita S, Kojima T. and Kitamura T. (2000). Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther 7:1063–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pear W. (1996). Transient transfection methods for preparation of high-titer retroviral supernatants. In: Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., USA, pp 9.11.11–19.11.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller DG, Adam MA. and Miller AD. (1990). Gene-transfer by retrovirus vectors occurs only in cells that are actively replicating at the time of infection. Mol Cell Biol 10:4239–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roe TY, Reynolds TC, Yu G. and Brown PO. (1993). Integration of murine leukemia-virus DNA depends on mitosis. Embo J 12:2099–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf D. and Goff SP. (2007). TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of murine leukemia virus in embryonic cells. Cell 131:46–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf D. and Goff SP. (2009). Embryonic stem cells use ZFP809 to silence retroviral DNAs. Nature 458:1201–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoniou MN, Skipper KA. and Anakok O. (2013). Optimizing retroviral gene expression for effective therapies. Hum Gene Ther 24:363–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotta A. and Ellis J. (2008). Retroviral vector silencing during iPS cell induction: an epigenetic beacon that signals distinct pluripotent states. J Cell Biochem 105:940–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srinivasakumar N, Zaboikin M, Tidball AM, Aboud AA, Neely MD, Ess KC, Bowman AB. and Schuening FG. (2013). Gammaretroviral vector encoding a fluorescent marker to facilitate detection of reprogrammed human fibroblasts during iPSC generation. Peer J 1:e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Federico M. (2003). From lentiviruses to lentivirus vectors. Methods Mol Biol 229:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marino MP, Luce MJ. and Reiser J. (2003). Small- to large-scale production of lentivirus vectors. Methods Mol Biol 229:43–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lotti F. and Mavilio F. (2003). The choice of a suitable lentivirus vector: transcriptional targeting. Methods Mol Biol 229:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Follenzi A. and Naldini L. (2002). Generation of HIV-1 derived lentiviral vectors. Method Enzymol 346:454–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freed EO. and Martin MA. (2007). HIVs and their replication. In: Fields' Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 2107–2185 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schambach A, Zychlinski D, Ehrnstroem B. and Baum C. (2013). Biosafety features of lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther 24:132–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kutner RH, Zhang XY. and Reiser J. (2009). Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc 4:495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pacchia AL, Mukherjee S. and Dougherty JP. (2003). Choice and use of appropriate packaging cell types. Methods Mol Biol 229:29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Broussau S, Jabbour N, Lachapelle G, Durocher Y, Tom R, Transfiguracion J, Gilbert R. and Massie B. (2008). Inducible packaging cells for large-scale production of lentiviral vectors in serum-free suspension culture. Mol Ther 16:500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fassati A. (2006). HIV infection of non-dividing cells: a divisive problem. Retrovirology 3:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li LH. and Clevers H. (2010). Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science 327:542–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen ZY, He CY, Meuse L. and Kay MA. (2004). Silencing of episomal transgene expression by plasmid bacterial DNA elements in vivo. Gene Ther 11:856–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen ZY, He CY, Ehrhardt A. and Kay MA. (2003). Minicircle DNA vectors devoid of bacterial DNA result in persistent and high-level transgene expression in vivo. Mol Ther 8:495–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kay MA, He CY. and Chen ZY. (2010). A robust system for production of minicircle DNA vectors. Nat Biotechnol 28:1287–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bigger BW, Tolmachov O, Collombet JM, Fragkos M, Palaszewski I. and Coutelle C. (2001). An araC-controlled bacterial cre expression system to produce DNA minicircle vectors for nuclear and mitochondrial gene therapy. J Biol Chem 276:23018–23027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nehlsen K, Broll S. and Bode J. (2006). Replicating minicircles: generation of nonviral episomes for the efficient modification of dividing cells—Research article. Gene Ther Mol Biol 10B:233–243 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayrhofer P, Blaesen M, Schleef M. and Jechlinger W. (2008). Minicircle-DNA production by site specific recombination and protein-DNA interaction chromatography. J Gene Med 10:1253–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsushita M. and Matsui H. (2005). Protein transduction technology. J Mol Med (Berl) 83:324–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noguchi H, Matsushita M, Kobayashi N, Levy MF. and Matsumoto S. (2010). Recent advances in protein transduction technology. Cell Transplant 19:649–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noguchi H. and Matsumoto S. (2006). Protein transduction technology: a novel therapeutic perspective. Acta Med Okayama 60:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Sayed A, Futaki S. and Harashima H. (2009). Delivery of macromolecules using arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides: ways to overcome endosomal entrapment. Aaps J 11:13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wadia JS. and Dowdy SF. (2002). Protein transduction technology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13:52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, Chung YG, Chang MY, Han BS, Ko S, Yang E, Cha KY, Lanza R. and Kim KS. (2009). Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell 4:472–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frankel AD. and Pabo CO. (1988). Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 55:1189–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dowdy SF. (2005). Protein transduction: generation of full-length transducible proteins using the TAT system. In: Current Protocols in Cell Biology. Bonifacino JS, Dasso M, Harford JB, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Yamada KM, eds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Bethesda, MD, pp 20.22.21–20.22.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vives E, Brodin P. and Lebleu B. (1997). A truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem 272:16010–16017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elliott G. and O'Hare P. (1997). Intercellular trafficking and protein delivery by a herpesvirus structural protein. Cell 88:223–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G. and Prochiantz A. (1994). The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem 269:10444–10450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pietersz GA, Li W. and Apostolopoulos V. (2001). A 16-mer peptide (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK) from antennapedia preferentially targets the Class I pathway. Vaccine 19:1397–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV. and Lebleu B. (2003). Cell-penetrating peptides—A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. J Biol Chem 278:585–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heitz F, Morris MC. and Divita G. (2009). Twenty years of cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Br J Pharmacol 157:195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A. and Dowdy SF. (1999). In vivo protein transduction: Delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science 285:1569–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Futaki S, Suzuki T, Ohashi W, Yagami T, Tanaka S, Ueda K. and Sugiura Y. (2001). Arginine-rich peptides—An abundant source of membrane-permeable peptides having potential as carriers for intracellular protein delivery. J Biol Chem 276:5836–5840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walev I, Bhakdi SC, Hofmann F, Djonder N, Valeva A, Aktories K. and Bhakdi S. (2001). Delivery of proteins into living cells by reversible membrane permeabilization with streptolysin-O. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:3185–3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agarwal S. (2006). Cellular reprogramming. Method Enzymol 420:265–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cho HJ, Lee CS, Kwon YW, Paek JS, Lee SH, Hur J, Lee EJ, Roh TY, Chu IS, et al. (2010). Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult somatic cells by protein-based reprogramming without genetic manipulation. Blood 116:386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamb RA. and Parks GD. (2007). Paramyxoviridae: The viruses and their replcation. In: Fields Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA, pp 1449–1496 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bitzer M, Armeanu S, Lauer UM. and Neubert WJ. (2003). Sendai virus vectors as an emerging negative-strand RNA viral vector system. J Gene Med 5:543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hasan MK, Kato A, Shioda T, Sakai Y, Yu DS. and Nagai Y. (1997). Creation of an infectious recombinant Sendai virus expressing the firefly luciferase gene from the 3′ proximal first locus. J Gen Virol 78:2813–2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yoshizaki M, Hironaka T, Iwasaki H, Ban H, Tokusumi Y, Iida A, Nagai Y, Hasegawa M. and Inoue M. (2006). Naked Sendai virus vector tacking all of the envelope-related genes: reduced cytopathogenicity and immunogenicity. J Gene Med 8:1151–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nishimura K, Sano M, Ohtaka M, Furuta B, Umemura Y, Nakajima Y, Ikehara Y, Kobayashi T, Segawa H, et al. (2011). Development of defective and persistent Sendai virus vector: a unique gene delivery/expression system ideal for cell reprogramming. J Biol Chem 286:4760–4771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li HO, Zhu YF, Asakawa M, Kuma H, Hirata T, Ueda Y, Lee YS, Fukumura M, Iida A, et al. (2000). A cytoplasmic RNA vector derived from nontransmissible Sendai virus with efficient gene transfer and expression. J Virol 74:6564–6569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inoue M, Tokusumi Y, Ban H, Kanaya T, Tokusumi T, Nagai Y, Iida A. and Hasegawa M. (2003). Nontransmissible virus-like particle formation by F-deficient sendai virus is temperature sensitive and reduced by mutations in M and HN proteins. J Virol 77:3238–3246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, Tabata T, Saeki K, Shikamura M, Takada N, Inoue M, Hasegawa M, Kawamata S. and Nishikawa S. (2011). Efficient generation of transgene-free human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature-sensitive Sendai virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:14234–14239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fusaki N, Ban H, Nishiyama A, Saeki K. and Hasegawa M. (2009). Efficient induction of transgene-free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85:348–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malone RW, Felgner PL. and Verma IM. (1989). Cationic liposome-mediated RNA transfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:6077–6081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bringmann A, Held SA, Heine A. and Brossart P. (2010). RNA vaccines in cancer treatment. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010:623687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nguyen J. and Szoka FC. (2012). Nucleic acid delivery: the missing pieces of the puzzle?. Acc Chem Res 45:1153–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weide B, Garbe C, Rammensee HG. and Pascolo S. (2008). Plasmid DNA- and messenger RNA-based anti-cancer vaccination. Immunol Lett 115:33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gallie DR. (1991). The cap and poly(A) tail function synergistically to regulate mRNA translational efficiency. Genes Dev 5:2108–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sclimenti CR. and Calos MP. (1998). Epstein-Barr virus vectors for gene expression and transfer. Curr Opin Biotechnol 9:476–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Van Craenenbroeck K, Vanhoenacker P. and Haegeman G. (2000). Episomal vectors for gene expression in mammalian cells. Eur J Biochem 267:5665–5678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lindner SE. and Sugden B. (2007). The plasmid replicon of Epstein-Barr virus: mechanistic insights into efficient, licensed, extrachromosomal replication in human cells. Plasmid 58:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yates JL, Warren N. and Sugden B. (1985). Stable replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus in various mammalian cells. Nature 313:812–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yates J, Warren N, Reisman D. and Sugden B. (1984). A cis-acting element from the Epstein-Barr viral genome that permits stable replication of recombinant plasmids in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:3806–3810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reisman D, Yates J. and Sugden B. (1985). A putative origin of replication of plasmids derived from Epstein-Barr virus is composed of two cis-acting components. Mol Cell Biol 5:1822–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yates JL, Camiolo SM. and Bashaw JM. (2000). The minimal replicator of Epstein-Barr virus oriP. J Virol 74:4512–4522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kirchmaier AL. and Sugden B. (1995). Plasmid maintenance of derivatives of oriP of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 69:1280–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mizuguchi H, Hosono T. and Hayakawa T. (2000). Long-term replication of Epstein-Barr virus-derived episomal vectors in the rodent cells. FEBS Lett 472:173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Felipe P. (2004). Skipping the co-expression problem: the new 2A “CHYSEL”. technology. Genet Vaccines Ther 2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Felipe P, Luke GA, Hughes LE, Gani D, Halpin C. and Ryan MD. (2006). E unum pluribus: multiple proteins from a self-processing polyprotein. Trends Biotechnol 24:68–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali KM. and Vignali DA. (2012). Design and construction of 2A peptide-linked multicistronic vectors. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2012:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim JH, Lee SR, Li LH, Park HJ, Park JH, Lee KY, Kim MK, Shin BA. and Choi SY. (2011). High cleavage efficiency of a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 in human cell lines, zebrafish and mice. PLoS One 6:e18556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Donnelly MLL, Hughes LE, Luke G, Mendoza H, ten Dam E, Gani D. and Ryan MD. (2001). The ‘cleavage’ activities of foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A site-directed mutants and naturally occurring ‘2A-like’ sequences. J Gen Virol 82:1027–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Felipe P, Luke GA, Brown JD. and Ryan MD. (2010). Inhibition of 2A-mediated ‘cleavage’ of certain artificial polyproteins bearing N-terminal signal sequences. Biotechnol J 5:213–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Belsham GJ. (2009). Divergent picornavirus IRES elements. Virus Res 139:183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jackson RJ. and Kaminski A. (1995). Internal initiation of translation in eukaryotes: The picornavirus paradigm and beyond. RNA 1:985–1000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Houdebine LM. and Attal J. (1999). Internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs): reality and use. Transgenic Res 8:157–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pelletier J. and Sonenberg N. (1988). Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature 334:320–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mizuguchi H, Xu ZL, Ishii-Watabe A, Uchida E. and Hayakawa T. (2000). IRES-dependent second gene expression is significantly lower than cap-dependent first gene expression in a bicistronic vector. Mol Ther 1:376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ding S, Wu X, Li G, Han M, Zhuang Y. and Xu T. (2005). Efficient transposition of the piggyBac (PB) transposon in mammalian cells and mice. Cell 122:473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mitra R, Fain-Thornton J. and Craig NL. (2008). piggyBac can bypass DNA synthesis during cut and paste transposition. Embo J 27:1097–1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu SCY, Meir YJJ, Coates CJ, Handler AM, Pelczar P, Moisyadi S. and Kaminski JM. (2006). piggyBac is a flexible and highly active transposon as compared to Sleeping Beauty, Tol2 and Mos1 in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:15008–15013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Handler AM. (2002). Use of the piggyBac transposon for germ-line transformation of insects. Insect Biochem Molec 32:1211–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Feschotte C. (2006). The piggyBac transposon holds promise for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:14981–14982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim A. and Pyykko I. (2011). Size matters: versatile use of PiggyBac transposons as a genetic manipulation tool. Mol Cell Biochem 354:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li X, Harrell RA, Handler AM, Beam T, Hennessy K. and Fraser MJ, Jr., (2005). piggyBac internal sequences are necessary for efficient transformation of target genomes. Insect Mol Biol 14:17–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yusa K, Rad R, Takeda J. and Bradley A. (2009). Generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent mouse stem cells by the piggyBac transposon. Nat Methods 6:363–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.McConnell MJ. and Imperiale MJ. (2004). Biology of adenovirus and its use as a vector for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 15:1022–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Russell WC. (2000). Update on adenovirus and its vectors. J Gen Virol 81:2573–2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang WW. (1999). Development and application of adenoviral vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 6:113–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Danthinne X. and Imperiale MJ. (2000). Production of first generation adenovirus vectors: a review. Gene Ther 7:1707–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Alba R, Bosch A. and Chillon M. (2005). Gutless adenovirus: last-generation adenovirus for gene therapy. Gene Ther 12Suppl 1:S18–S27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Harui A, Suzuki S, Kochanek S. and Mitani K. (1999). Frequency and stability of chromosomal integration of adenovirus vectors. J Virol 73:6141–6146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Strauss JH. and Strauss EG. (1994). The alphaviruses: gene expression, replication, and evolution. Microbiol Rev 58:491–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hahn CS, Hahn YS, Braciale TJ. and Rice CM. (1992). Infectious Sindbis virus transient expression vectors for studying antigen processing and presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:2679–2683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Xiong C, Levis R, Shen P, Schlesinger S, Rice CM. and Huang HV. (1989). Sindbis virus: an efficient, broad host range vector for gene expression in animal cells. Science 243:1188–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Herweijer H, Latendresse JS, Williams P, Zhang GF, Danko I, Schlesinger S. and Wolff JA. (1995). A plasmid-based self-amplifying sindbis-virus vector. Hum Gene Ther 6:1161–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dubensky TW, Driver DA, Polo JM, Belli BA, Latham EM, Ibanez CE, Chada S, Brumm D, Banks TA, et al. (1996). Sindbis virus DNA-based expression vectors: Utility for in vitro and in vivo gene transfer. J Virol 70:508–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.DiCiommo DP. and Bremner R. (1998). Rapid, high level protein production using DNA-based semliki forest virus vectors. J Biol Chem 273:18060–18066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Petrakova O, Volkova E, Gorchakov R, Paessler S, Kinney RM. and Frolov I. (2005). Noncytopathic replication of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus and eastern equine encephalitis virus replicons in mammalian cells. J Virol 79:7597–7608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Agapov EV, Frolov I, Lindenbach BD, Pragai BM, Schlesinger S. and Rice CM. (1998). Noncytopathic Sindbis virus RNA vectors for heterologous gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:12989–12994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Golipour A, David L, Liu Y, Jayakumaran G, Hirsch CL, Trcka D. and Wrana JL. (2012). A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell 11:769–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]