Review on gender-associated immune responses to influenza viruses, which though protective following vaccination, can cause immunopathology following exposure to pathogenic viruses.

Keywords: CCL2, estradiol, sex chromosome, sex difference, testosterone, TNF-α, vaccine

Abstract

Epidemiological evidence from influenza outbreaks and pandemics reveals that morbidity and mortality are often higher for women than men. Sex differences in the outcome of influenza are age-dependent, often being most pronounced among adults of reproductive ages (18–49 years of age) and sometimes reflecting the unique state of pregnancy in females, which is a risk factor for severe disease. Small animal models of influenza virus infection illustrate that inflammatory immune responses also differ between the sexes and impact the outcome of infection, with females generating higher proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses and experiencing greater morbidity and mortality than males. Males and females also respond differently to influenza vaccines, with women initiating higher humoral immune responses but experiencing more adverse reactions to seasonal influenza vaccines than men. Small animal models further show that elevated immunity following vaccination in females leads to greater cross-protection against novel influenza viruses in females compared with males. Sex steroid hormones, including estradiol and testosterone, as well as genetic differences between the sexes may play roles in modulating sex differences in immune responses to influenza virus infection and vaccination. Future studies must elucidate the pathways and cellular responses that differ between the sexes and determine how best to use this knowledge to inform public health policy-makers about prophylaxis and therapeutic treatments of influenza virus infections to ensure adequate protection in both males and females.

Introduction

Sex differences in the prevalence, intensity, and outcome of viral infections are well conserved across mammalian species. Males and females of species ranging from humans to horses and rodents differ in their responses to diverse viruses, including HIV, herpes simplex viruses, hantaviruses, hepatitis B virus, influenza viruses, measles virus, and West Nile virus [1]. The mechanisms that underlie differences between the sexes are complex and can involve immunological, hormonal, behavioral, and genetic factors. Females typically generate higher innate and adaptive immune responses compared with males [2–4], which can accelerate virus clearance and reduce virus load, but can be detrimental by causing immunopathology or the development of autoimmune disease. Immunological differences between the sexes are hypothesized to reflect endocrine-immune interactions. Accordingly, immunity to viruses can vary with changes in hormone concentrations caused by natural fluctuations over the menstrual or estrous cycle, contraception use, pregnancy, and menopause [5]. Receptors for sex steroids are expressed in many immune cells [6, 7]. Androgens, including dihydrotestosterone and T, generally suppress the activity of immune cells [2, 8, 9]. E2 can have divergent effects, with low concentrations enhancing proinflammatory cytokine production and Th1 responses and high or sustained concentrations reducing production of proinflammatory cytokines and augmenting Th2 responses and humoral immunity [10]. Elevated E2 also attenuates production of chemokines and recruitment of leukocytes and monocytes into several tissues, including the lungs [11–14]. The anti-inflammatory effects of high E2 are mediated by signaling through ERs, which inhibit activation of NF-κB-mediated inflammatory responses [15]. Whether immune responses to influenza viruses differ between males and females and are altered by sex steroids is just starting to be examined empirically.

2010 WHO REPORT ON SEX, GENDER, AND INFLUENZA

In 2010, the WHO published a report detailing evidence that sex and gender should be considered when evaluating exposure to and the outcome of influenza virus infection [16]. The report concluded that the outcome of pandemic influenza, as well as avian H5N1, is generally worse for young adult females [16]. In the United States, during the 1957 H2N2 pandemic, mortality was higher among females than males 1–44 years of age [17]. Worldwide, as of 2008, females were 1.6 times less likely to survive H5N1 infection than males [18]. During the first and second wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, a significant majority of patients hospitalized with severe 2009 H1N1 disease was young adult females (15–49 years of age) [16, 19–23]. Recent data from Japan highlight the complex interaction between sex and age on morbidity from influenza virus infection. Data from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, as well as from 2005, which was a particularly severe, seasonal influenza year in Japan, reveal profound sex differences in morbidity rates [24]. At younger (<20 years of age) and older (>80 years of age) ages, the morbidity rates were higher for males than females. Conversely, during the reproductive years (20–49 years of age), morbidity rates were higher for females than males. Pregnancy is an obvious female-specific risk factor that is associated with the worse outcome from seasonal, outbreak, and pandemic influenza virus infection and likely contributes to the overall higher morbidity and mortality in women compared with men [25, 26]. Although pregnancy is an important risk factor, it does not appear to explain all of the variability between the sexes [19, 20]. Many cases of severe disease also involve comorbid conditions, including chronic lung disease (e.g., asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder), which is typically more severe in females than males, independent of pregnancy [27]. Most epidemiological studies do not analyze differences between the sexes in the clinical features or outcome of influenza virus infection to accurately identify the biological and behavioral factors influencing male–female differences in responses to or the outcome of influenza virus infection.

We hypothesize that although sex differences in the incidence of influenza virus infection may reflect differences in exposure to these viruses (e.g., through behavior or occupation), differential disease severity between the sexes might involve biological differences in response to infection. The extent to which immune responses differ between males and females during influenza virus infection requires assessment, as this may contribute to differential severity of disease between the sexes. Disease associated with highly pathogenic influenza viruses and the corresponding clinical signs and symptoms, including fever, viral pneumonia, encephalitis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, are hypothesized to be mediated by the excessive proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine response (often referred to as the “cytokine storm”), initiated in response to infection [28, 29]. Humans, macaques, and mice infected with highly pathogenic strains of influenza virus, including the 1918 H1N1 or avian H5N1, produce high concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which correlate with elevated mortality [28–33]. Suppression of the global cytokine storm with an immunomodulatory drug protects against pathogenic influenza virus to a greater extent than does administration of an antiviral neuraminidase inhibitor [34]. Whether the duration and magnitude of the cytokine storm initiated during influenza virus infection differ between men and women and are altered by sex steroids has not been reported.

SEX DIFFERENCES IN INFLUENZA PATHOGENESIS IN MICE

Small animal models have been instrumental in characterizing sex differences in the outcome of influenza virus infection and in determining some of the mechanisms mediating these differences [35–37]. We have established that male mice are more resistant to influenza viruses than females. When adult male and female C57BL/6 mice are inoculated with mouse-adapted H1N1 (i.e., A/Puerto Rico/8/34) or H3N2 (i.e., A/Hong Kong/68) using 5 log10 dilutions to determine the LD50 for each sex, the LD50 for females is 11-fold lower for H1N1 and four-fold lower for H3N2 than the LD50 for males [38]. Sex differences in morbidity following infection with H1N1 or H3N2 viruses are also dose-dependent, in which females only experience greater body mass loss and hypothermia than males after infection with median doses; at sublethal doses, both sexes experience minor, transient morbidity, and at high, lethal doses, both sexes experience extreme morbidity [38]. Thus, females can experience a worse outcome following infection with H1N1 and H3N2 viruses, but this effect is dose-dependent.

When working with median doses of H1N1, females consistently show greater reductions in body mass and body temperature, as well as survival, as compared with males [35]. Titers of infectious virus in the lungs do not differ between the sexes, suggesting that changes in virus load alone are not responsible for the observed sex differences in morbidity and mortality. Highly pathogenic influenza viruses cause severe disease by initiating profound proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses [28, 29]. Consequently, within the 1st week after infection with H1N1, females show a greater induction of cytokines and chemokines, including CCL2, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6, in their lungs than males. Similarly, infection of adult BALB/c mice with a mouse-adapted H3N1 influenza virus results in greater lung hyper-responsiveness to methacholine challenge and production of CCL2, but not virus titers, in females compared with males [36]. These data suggest that host-mediated immunopathology, rather than virus replication, underlies sex differences in influenza pathogenesis (Fig. 1).

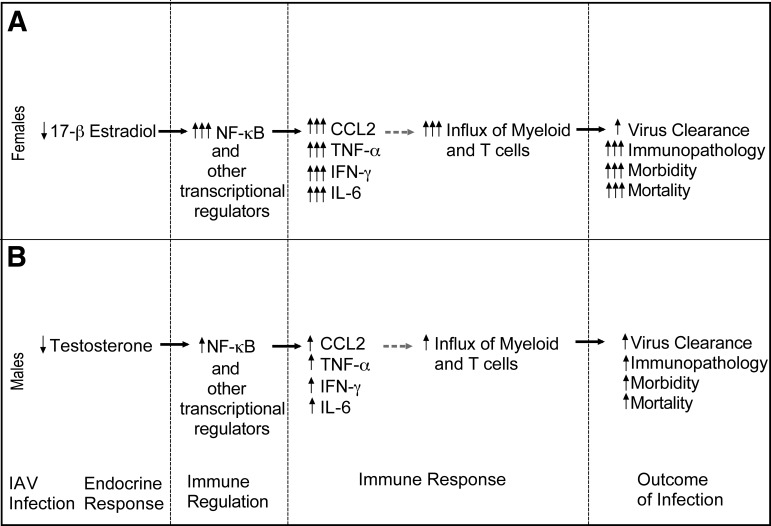

Figure 1. Hypothesized mechanisms mediating sex differences in the outcome of influenza virus infection.

In female mice, infection results in persistently low levels of E2, causing enhanced activity of NF-κB and proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine responses in the lungs. Greater induction of chemokines, in particular, might result in an excessive influx of immune cells and development of immunopathology in females (A). In male mice, although influenza virus infection suppresses T concentrations, this does not cause excessive, proinflammatory responses or development of immunopathology (B). Solid arrows indicate relationships demonstrated by our laboratory and others [15, 35]; broken arrows indicate hypothesized relationships that have not yet been demonstrated. IAV, Influenza A virus.

EFFECTS OF SEX STEROIDS ON IMMUNE RESPONSES TO INFLUENZA A VIRUS INFECTION

Viral infection can alter reproductive function [39, 40], which in mice, can result in greater suppression of reproductive activity in females than males [41]. Infection of male mice with H1N1 reduces circulating T concentrations as compared with uninfected males; our data thus far, however, illustrate that circulating androgens in adult males do not fully explain resistance to influenza virus infection [35]. We hypothesize that some androgenic effects may be organized early during sexual differentiation [42]. Future studies, in which androgens are manipulated during the critical period of sexual differentiation (i.e., during late prenatal and early neonatal development in mice), will be necessary to test this hypothesis.

In females, infection with H1N1 disrupts the estrous cycle, causing female mice to remain in diestrus (i.e., the stage of the estrous cycle when E2 and progesterone concentrations are at their nadir) for an extended period of time, resulting in persistently low E2 concentrations [35]. Administration of high doses of E2 exogenously to ovariectomized females, which results in sustained levels of E2 throughout the infection, significantly protects females by suppressing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α and CCL2, and reducing morbidity and mortality following H1N1 infection, as compared with ovariectomized females (i.e., females with no E2) or sham-intact females (i.e., females with low E2 as a result of infection) [35]. These data support the hypothesis that low concentrations of E2 in females promote excessive inflammatory responses that contribute to disease pathogenesis [10]. High E2 has potent anti-inflammatory actions, including repression of proinflammatory gene transcription and cytokine production [6, 43], which is partially mediated by inhibition of NF-κB transcriptional activity [44].

The anti-inflammatory effects of high E2 are mediated by signaling through two nuclear receptors, ERα and ERβ [45], which antagonize NF-κB activity [15]. Our data further reveal that E2 signaling through ERα, but not ERβ, is the mechanistic pathway of protection, as treatment of ovariectomized females with an ERα agonist, but not vehicle or an ERβ agonist, reduces hypothermia and increased rates of survival to levels that are similar to females treated with E2 [35]. Treatment with an ERα agonist also reduces TNF-α and CCL2 in the lungs to levels that are similar to those of females treated with E2. ERα has been identified in several immune cells, including DCs, macrophages, and T cells, whereas ERβ is expressed predominantly in B cells [6, 45]. The differential effects of ERα and ERβ agonists in vivo provide insight into the cell types that may be responsible for the exacerbated inflammatory responses observed in influenza virus-infected females with low or no E2.

EFFECTS OF SEX CHROMOSOMAL GENES ON INFLUENZA PATHOGENESIS IN MICE

Although direct effects of sex steroids may cause sex differences in physiology, an alternative hypothesis is that genes on the X chromosome, the Y chromosome, or both alter the expression of sexually dimorphic phenotypes directly in nongonadal tissues through mechanisms other than gonadal hormones [46–48]. Many genes on the X chromosome regulate immune function and play an important role in modulating sex differences in the development of immune-related diseases [49].

The Sry gene on the Y chromosome causes testes formation and T synthesis, leading to male-typic development of many phenotypes, whereas the absence of Sry results in ovaries and female-typic development [50]. The FCG mouse model has been developed to investigate the impact of sex chromosomes (XX vs. XY) and gonadal type (testes vs. ovaries) on phenotypes. In FCG mice, Sry is deleted from the Y chromosome, and a Sry transgene is inserted onto an autosome. Deletion of the Sry gene results in XY– mice, which are gonadal females (i.e., with ovaries), whereas insertion of the Sry transgene onto an autosome in XX or XY– mice (XXSry and XY–Sry) results in gonadal males (i.e., with testes). Depletion of gonadal steroids by gonadectomy of FCG mice unmasks effects of sex chromosome complement on behavior, brain function, renal function, and susceptibility to autoimmune disease [48, 51]. We examined whether sex chromosome complement affects susceptibility to influenza A virus infection and found that sex chromosome complement did not affect influenza pathogenesis [37]. Among those FCG animals that died following inoculation with H1N1 virus, the average day of death was later for gonadal male than gonadal female mice, regardless of whether their sex chromosome complement was XX or XY. These data support the hypothesis that sex differences in influenza virus pathogenesis are predominately mediated by sex steroid hormones rather than by sex chromosome complement.

SEX DIFFERENCE IN RESPONSE TO INFLUENZA VACCINES

Clinical vaccine data

In addition to influenza virus pathogenesis, males and females differ in response to influenza virus vaccines (Table 1). Rates of immunization against influenza are reportedly similar between the sexes or lower in women [63–67] and may be influenced by greater negative beliefs about the risks of vaccination [52] and lower acceptance of vaccines [53, 54] among women. Women consistently report more severe local and systemic reactions to influenza virus vaccines than men [55, 60–62], which may reflect a reporting bias or increased inflammatory responses among women rather than men [68, 69]. Antibody responses to the seasonal TIV are higher in women than men [55–58, 70]. In one study, the antibody response to a full dose of the seasonal TIV in women, 18–49 years of age, was almost twice that of men [55]. Importantly, the antibody response of women to a one-half dose of the TIV vaccine was equivalent to the antibody response of men to the full dose [55], which led to the proposal that when faced with vaccine shortages, such as during pandemics, women could be given less influenza vaccine and be as protected as men and also experience fewer side-effects [71]. The mechanisms mediating sex differences in antibody responses and adverse side-effects following vaccination have not been investigated thoroughly. It is also not clear if stronger antibody responses in women confer greater protection from influenza. Recent data, however, illustrate that among older adults, women had a higher frequency of cross-reacting antibodies against pandemic 2009 H1N1 than men [59], suggesting that rates of protection against novel strains of influenza viruses might be higher for females.

Table 1. Sex Differences in Response to Influenza Vaccines in Humans and Small Animal Models.

| Dependent measure | Sex difference | Age | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data | |||

| Acceptance | F < M | Adults | [52–54] |

| Humoral immune response | F > M | Adults | [55, 56] |

| F > M | Elderly adults | [57, 58] | |

| Cross-reacting antibodies | F > M | Elderly adults | [59] |

| Adverse reactions | F > M | Adults | [55, 60, 61] |

| F > M | Elderly adults | [57, 62] | |

| Animal studies | |||

| Humoral immune response | F > M | Adult C57BL/6 mice | [38] |

| Adverse reactions | F > M | Adult C57BL/6 mice | [38] |

| Cross-protection | F > M | Adult C57BL/6 mice | [38] |

F, Female; M, male.

Small animal vaccine models

Small animal models have been instrumental in defining vaccine-induced, protective immunity against influenza virus infection [72]. Our data support and extend available clinical data by showing that like women [55–57, 70], female mice mount higher neutralizing and total antibody responses against a sublethal primary infection/vaccination with influenza A viruses than males [38] (Table. 1). Our data further illustrate that following vaccination, females are better protected against lethal challenge with heterosubtypic (i.e., novel) strains of influenza viruses than males. Although elevated immunity afforded females greater protection than males against lethal challenge with heterosubtypic viruses, both sexes are equally protected against lethal challenge with homologous virus [38]. How higher antibody titers following vaccination in females results in greater cross-protection is not known but may involve mechanisms, such as activation of complement or T cell responses. Estradiol, at physiological concentrations, can stimulate antibody production by B cells [73–75], including antibody responses to an inactivated influenza vaccine administered in BALB/c mice [76]. Whether sex hormones affect the protective immune responses induced by vaccines and subsequent susceptibility to a lethal virus infection requires consideration.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

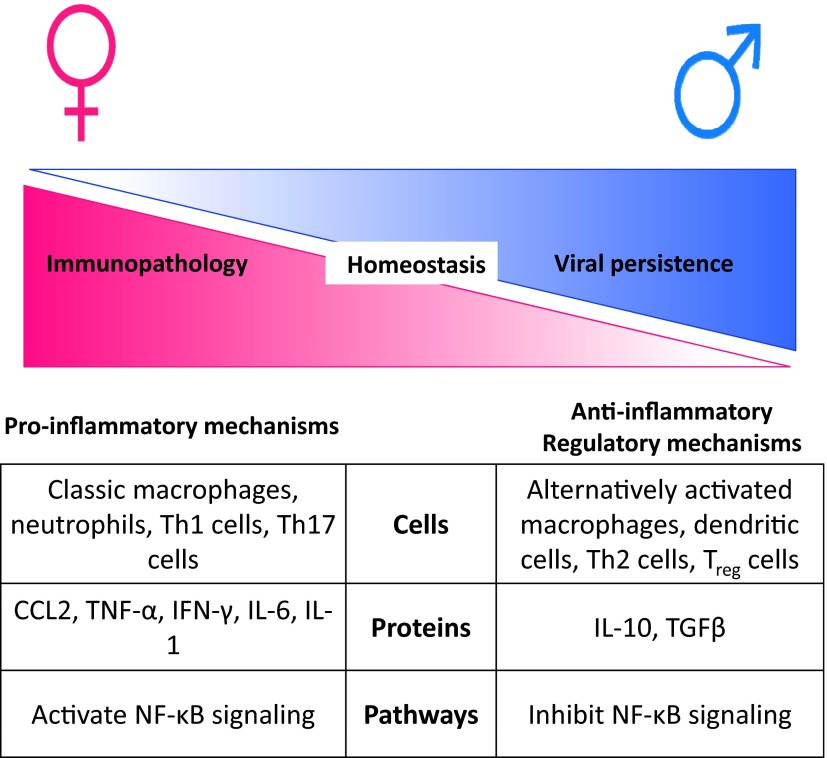

Heightened immunity in females is a double-edge sword, providing protection against viruses, including influenza viruses, but contributing to the development of immunopathology and autoimmunity. The immune system has evolved to have cells, proteins, and pathways that provide a balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, which ultimately determine the outcome of viral infection [77] (Fig. 2). In females, if dysregulation of the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms occurs, then it is more probable that the immune system will err on the side of mounting an excessive, proinflammatory response, leading to tissue damage and even death. Conversely, in males, if dysregulation of the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms occurs, then it is more likely that anti-inflammatory or regulatory responses will be elevated, leading to viral persistence [78]. Receptors for steroid hormones are present in immune cells and can regulate inflammatory responses through effects on transcriptional factors, including NF-κB [15, 44, 79], providing one mechanistic pathway by which immunological homeostasis is differentially regulated between the sexes. Other factors that might differentially regulate immunity between the sexes include small noncoding microRNAs, many of which are X-linked and can be regulated by sex steroids, including E2 [80, 81].

Figure 2. The balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms differs between the sexes and results in a differential outcome of influenza virus infection.

During influenza virus infection, females show a greater induction of proinflammatory responses, including CCL2, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-6, than males. Heightened proinflammatory responses may involve activation of inflammatory cells, proteins, and pathways that increase the risk of immunopathology in females compared with males. Conversely, in males, excessive induction of anti-inflammatory or regulatory responses may increase their risk of persistent viral infection. Treg, Regulatory T cell.

It is equally important to consider why males and females have evolved such different strategies for responding to viruses. One prevailing hypothesis is that sexual selection drives differences in immune function between males and females. In other words, biological factors associated with differential reproduction, successful competition for mates, and increased survival may affect immune function. Sex differences in the outcome of infection may reflect differential selection pressures acting on each sex to maximize reproductive output [82]. In addition to sexual selection, life history strategies may result in constraints on responses to infection. Presumably, engaging in behaviors that limit exposure to viruses or mounting immune responses to clear viruses requires metabolic resources that might otherwise be used for other biological processes, such as growth, maintenance of secondary sex characteristics, and reproduction [83, 84]. We might hypothesize that the costs and hence, trade-offs associated with heightened immunity may be different between the sexes. Consideration of why differences between males and females have evolved will improve our interpretation of these differences in response to influenza viruses.

Public health policies would benefit significantly from considering sex when making recommendations about prophylaxis and therapeutic treatments for influenza virus infection. The data reviewed illustrate that as compared with males: 1) females typically experience greater morbidity and mortality during influenza outbreaks and pandemics, 2) are less likely to accept vaccines, yet 3) develop higher immunity and greater protection following vaccination. Public health messages should be designed to increase rates of vaccination and hence, protection against infection among females. Sex also should be considered when effective vaccine and antiviral dosages are determined in an effort to maximize efficacy while limiting adverse side-effects. Our data further show that animal models of influenza pathogenesis can be used to provide insights into the role that sex, hormones, and genes play in modulating differential immune responses to influenza virus vaccination and infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for work presented from our laboratory was provided by U.S. National Institutes of Health AI089034, AI079342, and AI090344, an award from Marjorie Gilbert, and a Medtronic Society for Women's Health Research award.

Footnotes

- E2

- estradiol

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- FCG

- four core genotypes

- T

- testosterone

- TIV

- trivalent-inactivated vaccine

- WHO

- World Health Organization

AUTHORSHIP

S.L.K. presented the material at the Pathogenesis of Influenza: Virus-Host Interactions Keystone Symposium and drafted the manuscript. A.H. contributed to data collection, edited the manuscript, and drafted a figure. D.P.R. contributed to data collection, edited the manuscript, and drafted a figure.

DISCLOSURES

There are no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Klein S. L., Huber S. (2010) Sex differences in susceptibility to viral infection. In Sex Hormones and Immunity to Infection (Klein S. L., Roberts C. W., eds.), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 93–122 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roberts C. W., Walker W., Alexander J. (2001) Sex-associated hormones and immunity to protozoan parasites. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 476–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Araneo B. A., Dowell T., Diegel M., Daynes R. A. (1991) Dihydrotestosterone exerts a depressive influence on the production of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and γ-interferon, but not IL-2 by activated murine T cells. Blood 78, 688–699 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrat F., Lesourd B., Boulouis H. J., Thibault D., Vincent-Naulleau S., Gjata B., Louise A., Neway T., Pilet C. (1997) Sex and parity modulate cytokine production during murine ageing. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 109, 562–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brabin L. (2002) Interactions of the female hormonal environment, susceptibility to viral infections, and disease progression. AIDS Patient Care STDS 16, 211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilliver S. C. (2010) Sex steroids as inflammatory regulators. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 120, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kovats S., Carreras E., Agrawal H. (2010) Sex steroid receptors in immune cells. In Sex Hormones and Immunity to Infection (Klein S. L., Roberts C. W., eds.), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 53–92 [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Agostino P., Milano S., Barbera C., Di Bella G., La Rosa M., Ferlazzo V., Farruggio R., Miceli D. M., Miele M., Castagnetta L., Cillari E. (1999) Sex hormones modulate inflammatory mediators produced by macrophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 876, 426–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rettew J. A., Huet-Hudson Y. M., Marriott I. (2008) Testosterone reduces macrophage expression in the mouse of Toll-like receptor 4, a trigger for inflammation and innate immunity. Biol. Reprod. 78, 432–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Straub R. H. (2007) The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 28, 521–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giraud S. N., Caron C. M., Pham-Dinh D., Kitabgi P., Nicot A. B. (2010) Estradiol inhibits ongoing autoimmune neuroinflammation and NFκB-dependent CCL2 expression in reactive astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8416–8421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wira C. R., Fahey J. V., Ghosh M., Patel M. V., Hickey D. K., Ochiel D. O. (2010) Sex hormone regulation of innate immunity in the female reproductive tract: the role of epithelial cells in balancing reproductive potential with protection against sexually transmitted pathogens. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 544–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Speyer C. L., Rancilio N. J., McClintock S. D., Crawford J. D., Gao H., Sarma J. V., Ward P. A. (2005) Regulatory effects of estrogen on acute lung inflammation in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C881–C890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chotirmall S. H., Greene C. M., Oglesby I. K., Thomas W., O'Neill S. J., Harvey B. J., McElvaney N. G. (2010) 17β-Estradiol inhibits IL-8 in cystic fibrosis by up-regulating secretory leucoprotease inhibitor. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Biswas D. K., Singh S., Shi Q., Pardee A. B., Iglehart J. D. (2005) Crossroads of estrogen receptor and NF-κB signaling. Sci. STKE 2005, pe27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klein S. L., Pekosz A., Passaretti C., Anker M., Olukoya P. (2010) Sex, Gender and Influenza. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1–58 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Serfling R. E., Sherman I. L., Houseworth W. J. (1967) Excess pneumonia-influenza mortality by age and sex in three major influenza A2 epidemics, United States, 1957–58, 1960 and 1963. Am. J. Epidemiol. 86, 433–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. (2008) Update: WHO-confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) infection, November 2003–May 2008. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 83, 415–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kumar A., Zarychanski R., Pinto R., Cook D. J., Marshall J., Lacroix J., Stelfox T., Bagshaw S., Choong K., Lamontagne F., Turgeon A. F., Lapinsky S., Ahern S. P., Smith O., Siddiqui F., Jouvet P., Khwaja K., McIntyre L., Menon K., Hutchison J., Hornstein D., Joffe A., Lauzier F., Singh J., Karachi T., Wiebe K., Olafson K., Ramsey C., Sharma S., Dodek P., Meade M., Hall R., Fowler R. A. (2009) Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA 302, 1872–1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campbell A., Rodin R., Kropp R., Mao Y., Hong Z., Vachon J., Spika J., Pelletier L. (2010) Risk of severe outcomes among patients admitted to hospital with pandemic (H1N1) influenza. CMAJ 182, 349–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fielding J., Higgins N., Gregory J., Grant K., Catton M., Bergeri I., Lester R., Kelly H. (2009) Pandemic H1N1 influenza surveillance in Victoria, Australia, April–September, 2009. Euro. Surveill. 14, pii: 19368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oliveira W., Carmo E., Penna G., Kuchenbecker R., Santos H., Araujo W., Malaguti R., Duncan B., Schmidt M. (2009) Pandemic H1N1 influenza in Brazil: analysis of the first 34,506 notified cases of influenza-like illness with severe acute respiratory infection (SARI). Euro. Surveill. 14, pii: 19362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Denholm J. T., Gordon C. L., Johnson P. D., Hewagama S. S., Stuart R. L., Aboltins C., Jeremiah C., Knox J., Lane G. P., Tramontana A. R., Slavin M. A., Schulz T. R., Richards M., Birch C. J., Cheng A. C. (2010) Hospitalised adult patients with pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza in Melbourne, Australia. Med. J. Aust. 192, 84–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eshima N., Tokumaru O., Hara S., Bacal K., Korematsu S., Tabata M., Karukaya S., Yasui Y., Okabe N., Matsuishi T. (2011) Sex- and age-related differences in morbidity rates of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus of swine origin in Japan. PLoS ONE 6, e19409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jamieson D. J., Honein M. A., Rasmussen S. A., Williams J. L., Swerdlow D. L., Biggerstaff M. S., Lindstrom S., Louie J. K., Christ C. M., Bohm S. R., Fonseca V. P., Ritger K. A., Kuhles D. J., Eggers P., Bruce H., Davidson H. A., Lutterloh E., Harris M. L., Burke C., Cocoros N., Finelli L., MacFarlane K. F., Shu B., Olsen S. J. (2009) H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection during pregnancy in the U.S.A. Lancet 374, 451–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Louie J. K., Acosta M., Jamieson D. J., Honein M. A. (2010) Severe 2009 H1N1 influenza in pregnant and postpartum women in California. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tam A., Morrish D., Wadsworth S., Dorscheid D., Man S. P., Sin D. D. (2011) The role of female hormones on lung function in chronic lung diseases. BMC Womens Health 11, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guan Y., Poon L. L., Cheung C. Y., Ellis T. M., Lim W., Lipatov A. S., Chan K. H., Sturm-Ramirez K. M., Cheung C. L., Leung Y. H., Yuen K. Y., Webster R. G., Peiris J. S. (2004) H5N1 influenza: a protean pandemic threat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8156–8161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Jong M. D., Simmons C. P., Thanh T. T., Hien V. M., Smith G. J., Chau T. N., Hoang D. M., Chau N. V., Khanh T. H., Dong V. C., Qui P. T., Cam B. V., Ha do Q., Guan Y., Peiris J. S., Chinh N. T., Hien T. T., Farrar J. (2006) Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat. Med. 12, 1203–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cook D. N., Beck M. A., Coffman T. M., Kirby S. L., Sheridan J. F., Pragnell I. B., Smithies O. (1995) Requirement of MIP-1 α for an inflammatory response to viral infection. Science 269, 1583–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Szretter K. J., Gangappa S., Lu X., Smith C., Shieh W. J., Zaki S. R., Sambhara S., Tumpey T. M., Katz J. M. (2007) Role of host cytokine responses in the pathogenesis of avian H5N1 influenza viruses in mice. J. Virol. 81, 2736–2744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kobasa D., Jones S. M., Shinya K., Kash J. C., Copps J., Ebihara H., Hatta Y., Kim J. H., Halfmann P., Hatta M., Feldmann F., Alimonti J. B., Fernando L., Li Y., Katze M. G., Feldmann H., Kawaoka Y. (2007) Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus. Nature 445, 319–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kash J. C., Tumpey T. M., Proll S. C., Carter V., Perwitasari O., Thomas M. J., Basler C. F., Palese P., Taubenberger J. K., Garcia-Sastre A., Swayne D. E., Katze M. G. (2006) Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature 443, 578–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walsh K. B., Teijaro J. R., Wilker P. R., Jatzek A., Fremgen D. M., Das S. C., Watanabe T., Hatta M., Shinya K., Suresh M., Kawaoka Y., Rosen H., Oldstone M. B. (2011) Suppression of cytokine storm with a sphingosine analog provides protection against pathogenic influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12018–12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Robinson D. P., Lorenzo M. E., Jian W., Klein S. L. (2011) Elevated 17β-estradiol protects females from influenza A virus pathogenesis by suppressing inflammatory responses. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larcombe A. N., Foong R. E., Bozanich E. M., Berry L. J., Garratt L. W., Gualano R. C., Jones J. E., Dousha L. F., Zosky G. R., Sly P. D. (2011) Sexual dimorphism in lung function responses to acute influenza A infection. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 5, 334–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robinson D. P., Huber S. A., Moussawi M., Roberts B., Teuscher C., Watkins R., Arnold A. P., Klein S. L. (2011) Sex chromosome complement contributes to sex differences in Coxsackievirus B3 but not influenza A virus pathogenesis. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lorenzo M. E., Hodgson A., Kaplan J., Robinson D. P., Pekosz A., Klein S. L. (2011) Antibody responses and cross protection against lethal influenza A viruses differ between the sexes in C57BL/6 mice. Vaccine 29, 9246–9255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grinspoon S. (2005) Androgen deficiency and HIV infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41, 1804–1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dantzer R., O'Connor J. C., Freund G. G., Johnson R. W., Kelley K. W. (2008) From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 46–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Avitsur R., Yirmiya R. (1999) The immunobiology of sexual behavior: gender differences in the suppression of sexual activity during illness. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 64, 787–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Arnold A. P. (2009) The organizational-activational hypothesis as the foundation for a unified theory of sexual differentiation of all mammalian tissues. Horm. Behav. 55, 570–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cvoro A., Tatomer D., Tee M. K., Zogovic T., Harris H. A., Leitman D. C. (2008) Selective estrogen receptor-β agonists repress transcription of proinflammatory genes. J. Immunol. 180, 630–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chadwick C. C., Chippari S., Matelan E., Borges-Marcucci L., Eckert A. M., Keith J. C., Jr., Albert L. M., Leathurby Y., Harris H. A., Bhat R. A., Ashwell M., Trybulski E., Winneker R. C., Adelman S. J., Steffan R. J., Harnish D. C. (2005) Identification of pathway-selective estrogen receptor ligands that inhibit NF-κB transcriptional activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2543–2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Morani A., Warner M., Gustafsson J. A. (2008) Biological functions and clinical implications of estrogen receptors α and β in epithelial tissues. J. Intern. Med. 264, 128–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lenz F. (1931) Morbidic Hereditary Factors. Macmillan, New York, NY, USA [Google Scholar]

- 47. Purtilo D. T., Sullivan J. L. (1979) Immunological bases for superior survival of females. Am. J. Dis. Child. 133, 1251–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arnold A. P., Chen X. (2009) What does the “four core genotypes” mouse model tell us about sex differences in the brain and other tissues? Front. Neuroendocrinol. 30, 1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Libert C., Dejager L., Pinheiro I. (2010) The X chromosome in immune functions: when a chromosome makes the difference. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 594–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Koopman P., Gubbay J., Vivian N., Goodfellow P., Lovell-Badge R. (1991) Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature 351, 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smith-Bouvier D. L., Divekar A. A., Sasidhar M., Du S., Tiwari-Woodruff S. K., King J. K., Arnold A. P., Singh R. R., Voskuhl R. R. (2008) A role for sex chromosome complement in the female bias in autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1099–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Santibanez T. A., Mootrey G. T., Euler G. L., Janssen A. P. (2010) Behavior and beliefs about influenza vaccine among adults aged 50–64 years. Am. J. Health Behav. 34, 77–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schwarzinger M., Flicoteaux R., Cortarenoda S., Obadia Y., Moatti J. P. (2010) Low acceptability of A/H1N1 pandemic vaccination in French adult population: did public health policy fuel public dissonance? PLoS ONE 5, e10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chor J. S., Ngai K. L., Goggins W. B., Wong M. C., Wong S. Y., Lee N., Leung T. F., Rainer T. H., Griffiths S., Chan P. K. (2009) Willingness of Hong Kong healthcare workers to accept pre-pandemic influenza vaccination at different WHO alert levels: two questionnaire surveys. Br. Med. J. 339, b3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Engler R. J., Nelson M. R., Klote M. M., VanRaden M. J., Huang C. Y., Cox N. J., Klimov A., Keitel W. A., Nichol K. L., Carr W. W., Treanor J. J. (2008) Half- vs full-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (2004–2005): age, dose, and sex effects on immune responses. Arch. Intern. Med. 168, 2405–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Edwards K. M., Burns V. E., Allen L. M., McPhee J. S., Bosch J. A., Carroll D., Drayson M., Ring C. (2007) Eccentric exercise as an adjuvant to influenza vaccination in humans. Brain Behav. Immun. 21, 209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cook I. F., Barr I., Hartel G., Pond D., Hampson A. W. (2006) Reactogenicity and immunogenicity of an inactivated influenza vaccine administered by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection in elderly adults. Vaccine 24, 2395–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Couch R. B., Winokur P., Brady R., Belshe R., Chen W. H., Cate T. R., Sigurdardottir B., Hoeper A., Graham I. L., Edelman R., He F., Nino D., Capellan J., Ruben F. L. (2007) Safety and immunogenicity of a high dosage trivalent influenza vaccine among elderly subjects. Vaccine 25, 7656–7663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Booy R., Khandaker G., Heron L. G., Yin J., Doyle B., Tudo K. K., Hueston L., Gilbert G. L., Macintyre C. R., Dwyer D. E. (2011) Cross-reacting antibodies against the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus in older Australians. Med. J. Aust. 194, 19–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beyer W. E., Palache A. M., Kerstens R., Masurel N. (1996) Gender differences in local and systemic reactions to inactivated influenza vaccine, established by a meta-analysis of fourteen independent studies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15, 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nichol K. L., Margolis K. L., Lind A., Murdoch M., McFadden R., Hauge M., Magnan S., Drake M. (1996) Side effects associated with influenza vaccination in healthy working adults. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 156, 1546–1550 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Govaert T. M., Dinant G. J., Aretz K., Masurel N., Sprenger M. J., Knottnerus J. A. (1993) Adverse reactions to influenza vaccine in elderly people: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 307, 988–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Merrill R. M., Beard J. D. (2009) Influenza vaccination in the United States, 2005–2007. Med. Sci. Monit. 15, PH92–PH100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Qureshi A. M., Hughes N. J., Murphy E., Primrose W. R. (2004) Factors influencing uptake of influenza vaccination among hospital-based health care workers. Occup. Med. (Lond.) 54, 197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Opstelten W., van Essen G. A., Ballieux M. J., Goudswaard A. N. (2008) Influenza immunization of Dutch general practitioners: vaccination rate and attitudes towards vaccination. Vaccine 26, 5918–5921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jimenez-Garcia R., Hernandez-Barrera V., Carrasco-Garrido P., Lopez de Andres A., Perez N., de Miguel A. G. (2008) Influenza vaccination coverages among children, adults, health care workers and immigrants in Spain: related factors and trends, 2003–2006. J. Infect. 57, 472–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Endrich M. M., Blank P. R., Szucs T. D. (2009) Influenza vaccination uptake and socioeconomic determinants in 11 European countries. Vaccine 27, 4018–4024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pittman P. R. (2002) Aluminum-containing vaccine associated adverse events: role of route of administration and gender. Vaccine 20 (Suppl. 3), S48–S50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Klein S. L., Jedlicka A., Pekosz A. (2010) The Xs and Y of immune responses to viral vaccines. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10, 338–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cook I. F. (2008) Sexual dimorphism of humoral immunity with human vaccines. Vaccine 26, 3551–3555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Klein S. L., Greenberger P. (October 28, 2009) Do women need such big flu shots? In The New York Times, New York, NY, USA [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wu W. H., Pekosz A. (2008) Extending the cytoplasmic tail of the influenza A virus M2 protein leads to reduced virus replication in vivo but not in vitro. J. Virol. 82, 1059–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lu F. X., Abel K., Ma Z., Rourke T., Lu D., Torten J., McChesney M., Miller C. J. (2002) The strength of B cell immunity in female rhesus macaques is controlled by CD8+ T cells under the influence of ovarian steroid hormones. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 128, 10–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Franklin R. D., Kutteh W. H. (1999) Characterization of immunoglobulins and cytokines in human cervical mucus: influence of exogenous and endogenous hormones. J. Reprod. Immunol. 42, 93–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pauklin S., Sernandez I. V., Bachmann G., Ramiro A. R., Petersen-Mahrt S. K. (2009) Estrogen directly activates AID transcription and function. J. Exp. Med. 206, 99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nguyen D. C., Masseoud F., Lu X., Scinicariello F., Sambhara S., Attanasio R. (2011) 17β-Estradiol restores antibody responses to an influenza vaccine in a postmenopausal mouse model. Vaccine 29, 2515–2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rouse B. T., Sehrawat S. (2010) Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: what decides the outcome? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 514–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Easterbrook J. D., Klein S. L. (2008) Corticosteroids modulate Seoul virus infection, regulatory T-cell responses and matrix metalloprotease 9 expression in male, but not female, Norway rats. J. Gen. Virol. 89, 2723–2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. McKay L. I., Cidlowski J. A. (1999) Molecular control of immune/inflammatory responses: interactions between nuclear factor-κ B and steroid receptor-signaling pathways. Endocr. Rev. 20, 435–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pinheiro I., Dejager L., Libert C. (2011) X-chromosome-located microRNAs in immunity: might they explain male/female differences?: The X chromosome-genomic context may affect X-located miRNAs and downstream signaling, thereby contributing to the enhanced immune response of females. Bioessays 33, 791–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Dai R., Ahmed S. A. (2011) MicroRNA, a new paradigm for understanding immunoregulation, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Transl. Res. 157, 163–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zuk M., McKean K. A. (1996) Sex differences in parasite infections: patterns and processes. Int. J. Parasitol. 26, 1009–1023 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Barnard C. J., Behnke J. M. (2001) From psychoneuroimmunology to ecological immunology: life history strategies and immunity trade-offs. In Psychoneuroimmunology (Ader R., Felten D. L., Cohen N., eds.), Vol. 2, Academic, San Diego, CA, USA, 35–47 [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zuk M., Stoehr A. M. (2002) Immune defense and host life history. Am. Nat. 160, S9–S22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]