Abstract

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterized by interstitial lung infiltrates, dyspnea, and progressive respiratory failure. Reports linking telomerase mutations to familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP) suggest that telomerase activity and telomere length maintenance are important in disease pathogenesis.

Methods

To investigate the role of telomerase in lung fibrotic remodeling, intratracheal bleomycin was administered to mice deficient in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) or telomerase RNA component (TERC) and wild type controls. TERT deficient and TERC deficient mice were interbred to the F6 and F4 generation, respectively, when they developed skin manifestations and infertility. Fibrosis was scored using a semiquantitative scale and total lung collagen was measured using a hydroxyproline microplate assay. Telomere lengths were measured in peripheral blood leukocytes and isolated type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECs). Telomerase activity in type II AECs was measured using a real time PCR based system.

Results

Following bleomycin, TERT deficient and TERC deficient mice developed an equivalent inflammatory response and similar lung fibrosis (by scoring of lung sections and total lung collagen content) compared to controls, a pattern seen in both early generation (F1) and later generations (F6 TERT and F4 TERC). Telomere lengths were reduced in peripheral blood leukocytes and isolated type II AECs from F6 TERT and F4 TERC mice compared to controls.

Conclusions

Telomerase deficiency in a murine model leads to telomere shortening, but does not predispose to enhanced bleomycin induced lung fibrosis. Additional genetic or environmental factors may be necessary for development of fibrosis in the presence of telomerase deficiency.

Keywords: familial interstitial pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, lung

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic lung disease characterized by bilateral interstitial infiltrates, restriction on pulmonary function testing, and progressive dyspnea leading to respiratory failure [1]. Estimates for prevalence suggest that approximately 20 per 100,000 males and 13 per 100,000 females have IPF [2]. Unfortunately, no effective treatments are yet available and mortality from disease remains quite high. While the cause of IPF remains unknown, recent studies in familial interstitial pneumonia (FIP) have begun to shed light on potential pathogenic mechanisms [3;4]. FIP is defined when two or more individuals in a family have proven idiopathic interstitial pneumonia [4–6]. Based on available information, mutations in genes in the telomerase complex may account for up to 15% of cases of FIP.

The telomerase complex is responsible for maintaining the integrity of telomeres, the tandem repeats of TTAGGG sequences that are responsible for providing protection of the end of chromosomes. Telomeres and their specific telomere binding proteins prevent DNA repair mechanisms from recognizing chromosome ends as DNA breaks. During DNA replication, telomere shortening occurs, and with repetitive cell divisions, the resultant telomere erosion can lead to arrest of growth and cell death [7–11]. To offset the effect of telomere shortening, the telomerase complex, a specialized DNA polymerase, adds the telomeric repeat sequences to the chromosome ends. Telomerase has two essential components, the catalytic component telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), and the RNA template telomerase RNA component (TERC) [12–14].

Recently, mutations in both TERT and TERC have been linked to cases of FIP. The mutations resulted in decreased telomerase activity in in vitro evaluations, and mutation carriers had marked telomere shortening in peripheral blood leukocytes compared to age matched controls [15;16]. Since those initial evaluations, it has been hypothesized that these families developed pulmonary fibrosis because of progressive telomere shortening in the alveolar epithelium [4]. To further investigate this potential relationship, we evaluated TERT deficient and TERC deficient mice to determine if telomerase deficiency and telomere shortening predisposes to bleomycin induced lung fibrosis.

METHODS

Animal model

TERT heterozygous deficient, TERC heterozygous deficient, and wild type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine. For these studies, mice maintained in the heterozygous state are identified as generation F0. To generate mice deficient in each gene, F0 males were crossed to F0 females, with the pups identified as F1. Serial homozygous deficient matings were performed to generate subsequent generations down to F4 for TERC deficient and F6 for TERT deficient. Both males and females were used in experiments. All mice for these experiments were in a C57BL/6J background and entered experiments at greater than 8 weeks of age, with ages, body weights, and sex distribution similar among groups for individual experiments. All mouse experiments were approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bleomycin (Bedford Laboratories, Bedford, Ohio) was injected intratracheally (IT) in wild type and gene targeted mice using an intubation procedure as previously described [17;18]. Both single dose IT bleomycin injections and repetitive dose IT bleomycin injections (dose given every two weeks for 4 or 8 doses) were performed as previously described [17]. At baseline and at designated time points post bleomycin, lungs were harvested for histology and frozen tissue as previously described [17–22].

Histology and microscopy

For formalin fixed lung sections, lungs were formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxyin and eosin (H&E) or Masson’s trichrome as previously described [19;20]. Light microscopy was performed using an Olympus IX81 Inverted Research Microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Semiquantitative fibrosis scoring

Quantification of lung fibrosis on histological specimens was performed by an investigator blinded to the group using a semiquantitative score on 10 sequential, nonoverlapping fields (magnification ×300) as previously described [17–19;22].

Collagen content

Frozen lung tissue samples were hydrolyzed in 6N HCl, and hydroxyproline content quantitated using a microplate assay based on the Ehrlich’s reaction as previously described [18;22;23]. Lung collagen content was calculated from these results as hydroxyproline accounts for approximately 13.3% of collagen by weight.

Lung lavage and cell counts

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed as detailed previously [18]. After euthanasia, three 800 μl lavages of sterile saline were performed using a 20g blunt tipped needle inserted into the trachea. Samples were centrifuged at 400xg for ten minutes and the supernatant discarded. Cell counts were performed by manual counting under light microscopy using a hemocytometer. Approximately 30,000 cells from each specimen were loaded onto slides using a Cytospin 2 (Shandon Southern Products, England). These slide preparations were then stained using a modified Wright stain and reviewed under light microscopy for differential white blood cell counts.

Telomere length measurements

Blood was collected from the mice at the time of harvest, and peripheral blood leukocytes were isolated from blood as previously described [24]. DNA was isolated from the peripheral blood leukocytes using a Qiagen DNAeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per manufacturer instructions. Telomere length measurements on this DNA were performed using a real time PCR based protocol [25]. Briefly, 90ng of DNA was aliquoted for use on both the telomere and single copy gene plates with water added to bring the final volume to 90 ul. A cocktail consisting of 2.5mM DTT, 50nM ROX, 1X SYBR greener super mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was thoroughly mixed and 96 ul added to each of the DNA aliquots. Each aliquot was divided between 2 PCR plates containing either primers for telomeres or the single copy gene, each at 450nM final concentration. All samples were run in triplicate with a final volume for all wells of 30ul. Primer sequences for the telomeres were Tel1b CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTT GGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT and Tel2b GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTT ACCCTTACCCT [24]. Single copy gene primer sequences were m36B4 F ACTGGTCTAGG ACCCGAGAAG and m36b4 R TCAATGGTGCCTCTGGAGATT [26]. A five point standard curve was generated for each plate using oligonucleotides as follows: Tel-84 oligo 1E9 (kb), 3E8, 1E8, 3E7 and 1E7; m36B4-79 oligo 1E6 (equivalent to 2.5E6 diploid copies per reaction), 3E5, 1E5, 3E4, 1E4. Oligos were as follows: Tel 84-mer: ACCCCATTCTATCATCAACGGGT ACAAACGAGTCCTGGCCTTGTCTGTGGAGACGGATTACACCTTCCCACTTGCTGAA; m36B479-mer: ACTGGTCTAGGACCC GAGAAGACCTCCTTCTTCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCACC ACGAAAATCTCCAGAGGCACCATTGA. A 15ng/ul solution of pBR322 plasmid was used to dilute the oligo DNAs. Cycling parameters for the telomere plates were 5 min at 50° C, 10 min at 95° C followed by 40 cycles of 95° C for 15 seconds, 54° C for 1 min. Conditions for the single copy gene plate were 5 min at 50° C, 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95° C for 15 seconds, 60° C for 1 min. Data was generated using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System (Carlsbad, CA) with version 2.0.4 software. Telomere length is calculated as the telomere signal per sample divided by its companion single copy gene signal to give the average telomere length per diploid genome. Type II AECs were isolated from adult mice using techniques as previously described [20;21], with DNA isolated and telomere lengths analyzed as with the leukocytes above.

Telomerase activity measurements

Type II AECs were isolated from adult mice using techniques as previously described [20;21]. Telomerase activity was determined on isolated type II AECs using the TRAPEZE RT Telomerase Detection Kit (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), a PCR-based telomeric repeat amplification protocol method, per manufacturer recommendations. With this kit, Amplifluor primers are designed to emit a fluorescence signal only when they are incorporated into PCR products, with the net increase of fluorescence in the reaction vessel directly correlating to the amount of amplified DNA produced in the reaction. Briefly, type 2 cells pellets were resuspended in CHAPS lysis buffer and protein levels were evaluated using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were combined with the Trapeze RT reaction mix, which contained TS primer, RP tailed primer, Amplifluor primers and dNTP, in RNase-free PCR tubes, adding Taq polymerase. Positive and negative controls provided by the manufacturer were examined accordingly. PCR amplification was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR System (Carlsbad, CA) per manufacturer recommendations. Telomerase activity data was reported as activity relative to the kit specified negative control.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences among groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison post test. Differences between pairs were assessed using Student’s t-test. Results are presented as mean +/− standard error of the mean. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Telomerase deficient mice do not have enhanced lung fibrosis following intratracheal bleomycin

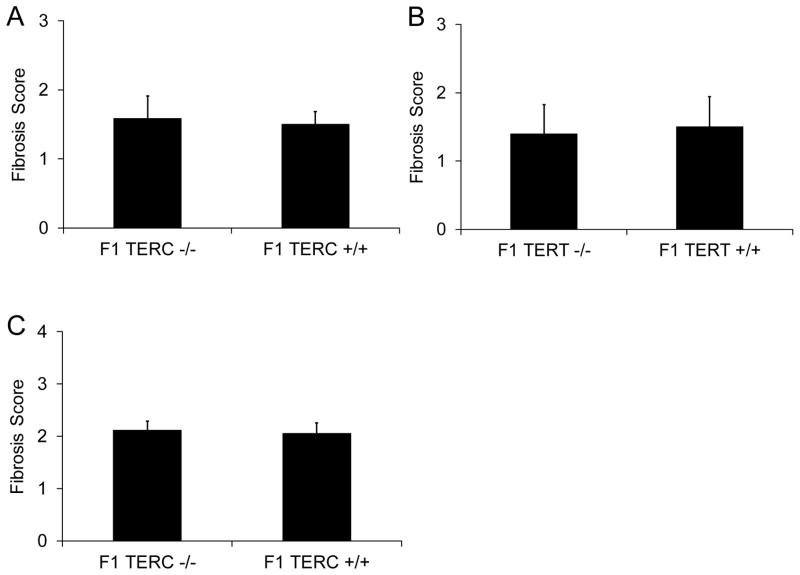

In initial experiments, 8–10 week old TERC deficient and TERT deficient mice in the F1 generation and littermate F1 wild type controls were given intratracheal bleomycin and harvested at 3 weeks post bleomycin with trichrome blue stained slides analyzed for lung fibrosis. No differences in appearance of the lung sections or semiquantitative fibrosis scoring were seen among these three groups with 0.04 units of bleomycin (Figure 1A,B), a finding in contrast to prior work by Liu et al, in which early generation TERT deficient mice were protected from bleomycin induced lung fibrosis using a similar bleomycin dose [27]. After this initial observation and given the fact that effects of telomerase deficiency might be accentuated with aging and repeated injury, we then evaluated 8–12 month old F1 TERC −/− mice and littermate controls with repetitive bleomycin 0.04 units every other week for 4 doses with lung harvest at 2 weeks after the final dose, but again no difference was noted in fibrosis between the two groups (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

F1 TERC deficient and F1 TERT deficient mice had similar levels of lung fibrosis fibrosis following intratracheal bleomycin compared to their respective littermate controls. A) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–10 week old F1 TERC deficient (F1 TERC −/−) and F1 littermate wild type controls (F1 TERC +/+) at 3 weeks following 0.04 units of intratracheal bleomycin. N = 6 for F1 TERC −/− and 6 for F1 TERC +/+. Experiment survival was 6/6 for F1 TERC −/− and 6/6 for F1 TERC +/+. B) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–10 week old F1 TERT deficient (F1 TERT −/−) and F1 littermate wild type controls (F1 TERT +/+) at 3 weeks following 0.04 units of intratracheal bleomycin. N = 5 for F1 TERT −/− and 5 for F1 TERT +/+. Experiment survival was 5/5 for F1 TERT −/− and 5/5 for F1 TERT +/+. C) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–12 month old F1 TERC −/− and F1 TERC +/+ littermate controls at 2 weeks following 4 biweekly repetitive doses of 0.04 units of intratracheal bleomycin. N = 9 for F1 TERC −/− and 10 for F1 TERC +/+. Experiment survival was 9/14 for F1 TERC −/− and 10/14 for F1 TERC +/+.

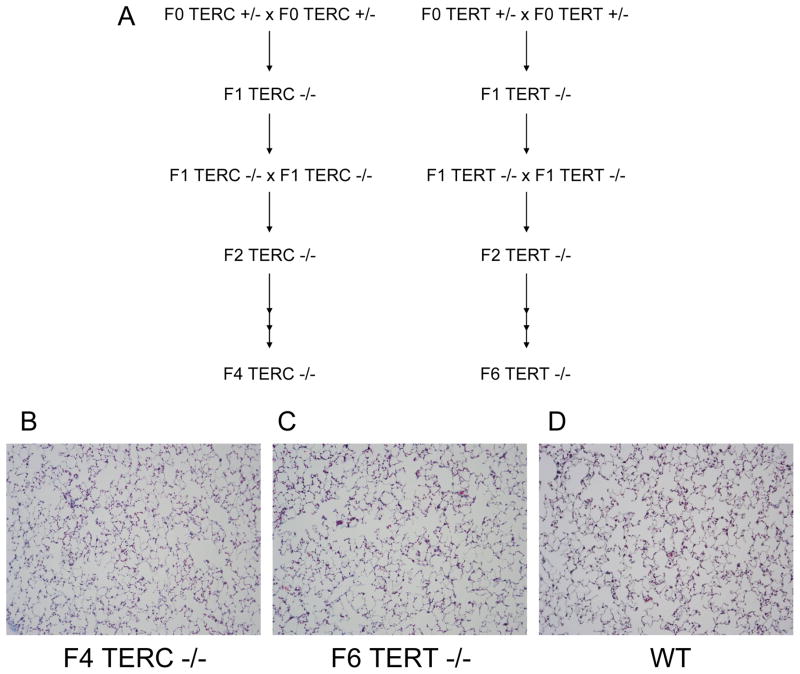

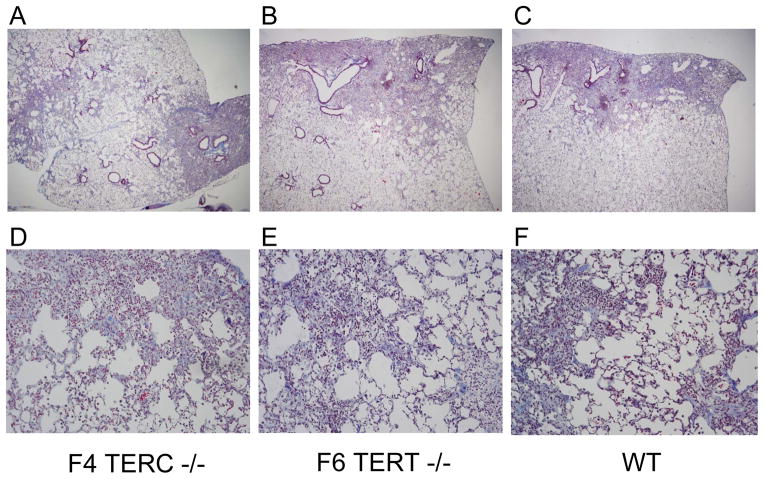

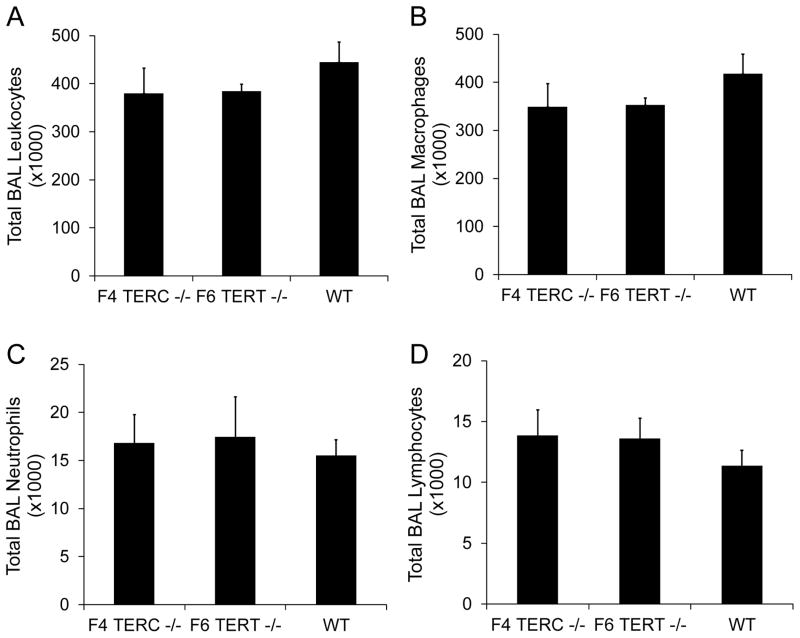

Next, TERC deficient and TERT deficient mice were crossed in successive breedings to give later generation mice (Figure 2A). TERC deficient mice could be generated down to the F4 generation and TERT deficient mice to the F6 generation. At those generations, the mice could not breed any further and also displayed the skin manifestations previously noted in prior studies with telomerase deficiency [28;29]. On histologic evaluation, lung sections from untreated TERC deficient and TERT deficient mice appeared similar to wild type controls with no evidence of lung fibrosis (Figure 2B–D). Multiple bleomycin studies were performed across different generations, and even down to the F4 TERC −/− and F6 TERT −/− mice, the degree and distribution of fibrosis was similar to control wild type mice. Representative trichrome blue stained lung sections are shown from F4 TERC −/−, F6 TERT−/−, and wild type controls at 3 weeks following bleomycin in Figure 3A–F. Furthermore, semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis in young mice (8–10 weeks) whether they received 0.04 units or 0.08 units of bleomycin was similar among the three groups (Figure 3G,H). Again, because of the possibility that aging might contribute to effects of telomerase deficiency, we evaluated older mice (8–12 months) with 0.04 units bleomycin and again noted no difference in fibrosis among the three groups as determined by both semiquantitative scoring (Figure 3I) and lung collagen content (Figure 3J) We also performed repetitive bleomycin studies in later generation TERT deficient mice and controls, where mice received IT bleomycin 0.04 units every 2 weeks for 8 doses with harvesting at 2 weeks after the last dose [17], and as shown in Figure 3K, lung fibrosis was similar between the two groups. Furthermore, other experiments were performed in intermediate generations without any difference in lung fibrosis among TERC −/−, TERT −/−, and controls. In addition to these fibrosis measurements, lung inflammation as measured by total and differential cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was similar among F4 TERC deficient, F6 TERT deficient, and wild type mice at 2 weeks following single dose bleomycin (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

F4 TERC deficient (F4 TERC −/−) and F6 TERT deficient (F6 TERT −/−) mice did not develop spontaneous lung fibrosis. A) Schematic illustrating breeding strategy to develop F4 TERC deficient and F6 TERT deficient mice. Trichrome blue stained lung sections from B) F4 TERC deficient, C) F6 TERT deficient, and D) wild type (WT) control mice. Magnification x200.

Figure 3.

F4 TERC deficient, F6 TERT deficient, and wild type control mice had similar levels of lung fibrosis following intratracheal bleomycin. A–F) Trichrome blue stained lung sections from A,D) F4 TERC deficient, B,E) F6 TERT deficient, and C,F) wild type (WT) control mice. Magnification: A–C x40; D–F x200. G) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–10 week old F4 TERC deficient (F4 TERC −/−), F6 TERT deficient (F6 TERT −/−), and wild type (WT) control mice at 3 weeks following 0.04 units of bleomycin. N=11 for F4 TERC−/−, 11 for F6 TERT −/−, and 13 for WT. Experiment survival was 11/13 for F4 TERC−/−, 11/13 for F6 TERT −/−, and 13/15 for WT. H) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–10 week old F4 TERC −/−, F6 TERT −/−, and WT control mice at 3 weeks following 0.08 units of bleomycin. N=5 for F4 TERC −/−, 9 for F6 TERT −/−, and 7 for WT. Experiment survival was 5/8 for F4 TERC −/−, 9/12 for F6 TERT −/−, and 7/10 for WT. I) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis and J) total lung collagen content as assessed by a microplate hydroxyproline assay from 8–12 month old F4 TERC −/−, F6 TERT −/−, and WT control mice at 3 weeks following 0.04 units of bleomycin (bleo) or saline. N=9 for F4 TERC −/− saline treated, F6 TERT −/− saline treated, WT saline treated, and F4 TERC −/− bleomycin treated; 12 for F6 TERT −/− bleomycin treated; and 10 for WT bleomycin treated. Experiment survival post bleomycin was 9/10 for F4 TERC −/−, 12/13 for F6 TERT −/−, and 10/10 for WT. For collagen data in J, p<0.05 between individual genotype columns for saline versus bleo. K) Semiquantitative scoring of lung fibrosis from 8–10 week old F4 TERT −/− and WT controls at 2 weeks following 8 biweekly repetitive doses of 0.04 units of intratracheal bleomycin. N = 12 for F4 TERT −/− and 9 for WT. Experiment survival was 12/14 for F4 TERT −/− and 9/11 for WT.

Figure 4.

Lung inflammation as assessed by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell counts was similar among F4 TERC deficient (F4 TERC −/−), F6 TERT deficient (F6 TERT −/−), and wild type (WT) control mice at 2 weeks following bleomycin. Graphs depict total BAL A) leukocytes, B) macrophages, C) neutrophils, and D) lymphocytes. N = 7 for F4 TERC −/−, 5 for F6 TERT −/−, and 8 for WT.

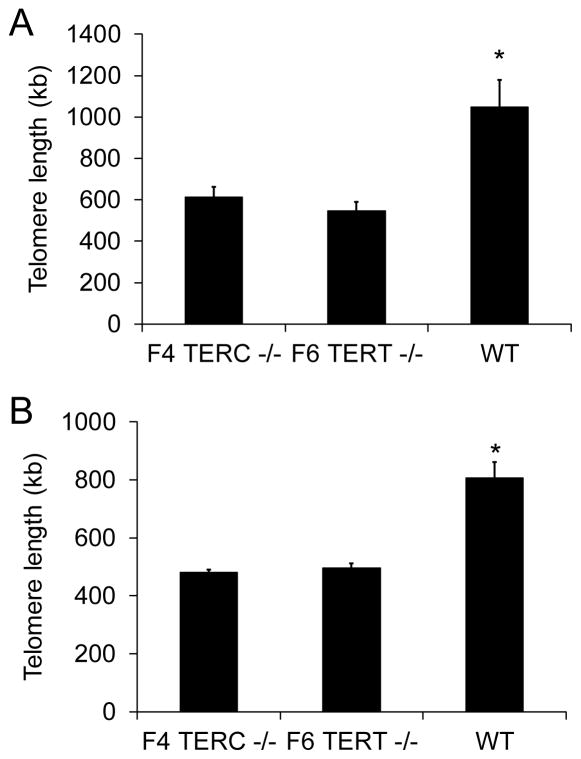

Telomerase deficient mice have absence of telomerase activity and telomere shortening

Type II AECs were isolated from F4 TERC deficient, F6 TERT deficient, and wild type controls, and telomerase activity evaluated on these cells using a real time PCR approach. AECs from both of the telomerase deficient lines did not have telomerase activity present (results were at the level of the kit specified negative control), while wild type AECs had telomerase activity that was 2.3 logs greater than the negative control. To determine if telomere lengths were different between telomerase deficient and wild type control mice, telomere lengths were measured on peripheral blood leukocytes using a real time PCR approach. Telomere lengths in both F4 TERC deficient and F6 TERT deficient mice were significantly shorter than in wild type controls (Figure 5A). Furthermore, telomere lengths from isolated type II AECs were shorter in F4 TERC deficient and F6 TERT deficient mice compared to wild type controls (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Telomere lengths were shortened in F4 TERC deficient (F4 TERC −/−) and F6 TERT deficient (F6 TERT −/−) mice compared to wild type (WT) controls. A) Real time PCR telomere lengths from peripheral blood leukocytes. N = 14 for F4 TERC −/−, 13 for F6 TERT −/−, and 9 for WT. *p<0.01 compared to other columns. B) Real time PCR telomere lengths from isolated type II AECs. N = 3 for F4 TERC −/−, 4 for F6 TERT −/−, and 4 for WT. * p<0.01 compared to other columns.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, telomerase deficiency, either through absence of the TERT or TERC component, did not result in enhanced lung fibrosis following intratracheal bleomycin. Even with interbreeding these mice until telomere shortening was prominent and the mice could not reproduce easily, these mice did not develop a spontaneous lung phenotype and there was no difference in bleomycin induced fibrosis compared to wild type controls.

The most compelling evidence that telomerase has a prominent role in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis comes from studies of human FIP cases in which mutations in either TERC or TERT are present [15;16]. With these mutations, decreased telomerase activity is noted and telomere shortening is severe with many mutation carriers having peripheral blood leukocyte telomere lengths less than 10% (and some less than 1%) of age matched controls [15;16]. In fact, subsequent studies of cases of IPF indicate that telomere shortening is prominent even in the absence of TERC or TERT mutations [30;31], suggesting the potential for a common role for telomerase dysfunction in IPF [4]. With these human findings, studies are needed to better define the mechanisms involved in telomerase mutation associated FIP. With this in mind, an attractive model to consider was to evaluate TERC and TERT deficient mice with experimentally induced lung fibrosis, and thus the rationale for the studies we have performed here.

Tissues affected most by decreased telomerase activity (due to mutations or deficiency) would be predicted to be those subject to significant proliferation, including bone marrow, areas of epithelial turnover such as the skin and gastrointestinal tract, and the germline. Similarly, murine models of telomerase deficiency result in abnormalities in tissues with high rates of proliferation [28;29;32–34]. Most research mouse strains (including C57BL/6) have long telomeres, and studies to date delineate that telomere shortening is critical to developing a disease phenotype. In fact, in early generation C57BL/6 TERC deficient mice, no phenotype is observed because telomere shortening is not at a critical level to affect cell survival. With successive generations of breeding into a maintained homozygous deficient line, TERC deficient mice have progressive telomere shortening and begin having disease manifestations by the fourth generation [28;32;33]. In later generation TERC deficient mice (generations 4–6), an increased incidence of skin lesions, alopecia, and hair graying is noted, which we also observed in these studies. Decreased survival, atrophy of villi and focal adenomas in the gastrointestinal tract, hematologic abnormalities, and aberrancies in the seminiferous tubules are found in later generation TERC deficient mice [28]. An increased incidence of genomic instability and spontaneous cancer are noted in aging TERC deficient mice [33;34]. TERT deficient mice have not been studied as extensively as TERC deficient mice, but they also have telomere shortening across generations and phenotypes similar to TERC deficient mice [29].

Until recently, studies analyzing telomerase expression in the lung were relatively limited. Rodent studies have shown that telomerase expression occurs during development, is normally quiescent during adulthood, and can be induced in type II AECs in response to injury [35–37]. A recent study evaluating telomerase activity in wild type murine AECs delineated that after a single dose of intratracheal bleomycin, telomerase activity was increased in isolated type II AECs, but telomere lengths were unchanged [38]. Prior studies by Driscoll and colleagues observed that telomerase expression could be observed in a subpopulation of type II AECs [35;36], suggesting that these cells may be an important stem cell population in the lung. Subsequently, this group has demonstrated that telomerase deficiency impacts lung growth as well as lung regenerative capacity. Lee et al. reported that when bred into the F4 generation, TERC deficient mice had alveolar simplification with alveolar wall thinning, increased alveolar size, and an absolute reduction in the number of type II AECs [39]. We did not observe any gross lung abnormalities in late generation TERC deficient or TERT deficient mice, although we did not employ the morphologic measurements those investigators used. In a partial pneumonectomy study, F3 TERC deficient mice had decreased survival (no F4 mice survived), a marked attenuation of the compensatory lung growth typically noted in this procedure, and a diminished stem/progenitor cell response [40], demonstrating an important role for telomerase in lung repair mechanisms. Furthermore, recent studies by Alder et al. revealed that mice with telomerase deficiency and telomere shortening had increased susceptibility to cigarette smoke induced emphysema [41]. Finally, in 2007, Liu et al analyzed early generation TERT deficient mice and noted a relative protection from bleomycin induced fibrosis with TERT deficiency, an outcome opposite what might have been predicted based on the FIP genetic associations, and that the effect appeared to be mediated from bone marrow progenitor cells [27]. No telomere length data were reported in that manuscript, so it is not known whether telomere length differences contributed to their observations or if the results stemmed from potential non-telomere length effects of TERT. In contrast, we did not observe any differences in lung fibrosis post bleomycin with telomerase deficiency with early or late generation TERC deficient and TERT deficient mice. The reason for this discrepancy between our results presented here and those from the Liu et al study remains unclear, even though we used similar gene targeted mice (from the TERT standpoint) and a similar dose of bleomycin.

Given the FIP data and the growth arrest data in the partial pneumonectomy model [40], it may have been expected that these TERC or TERT deficient mice, with appropriate telomere shortening, would have had greater bleomycin induced fibrosis. However, across many different experiments with these TERC −/− and TERT −/− mice, we did not find evidence that telomerase deficiency affected lung fibrosis in the bleomycin model (in either direction). The reason for this observation remains unclear, but some possibilities should be considered. Given that the effects of telomerase dysfunction or deficiency may increase with aging, we did some of our experiments in older mice (8–12 months), but it is possible that considerably greater age (18–24 months) in the mice might be necessary to unmask a profibrotic tendency. Furthermore, our single dose experiments were done with measurements at the peak point of fibrotic remodeling in the bleomycin model without an analysis at later time points, where there could possibly be an issue with resolution of fibrosis in the telomerase deficient mice. However, this possibility is tempered considerably given the fact that no differences were noted in the repetitive bleomycin model where the lungs are exposed to multiple episodes of injury and repair over a longer period of time. Another possibility is that, though quite prominent, the degree of telomere shortening in the alveolar epithelium, which was limited by the ability to continue breeding the mice in successive generations, did not reach a level that precluded normal repair responses. Additionally, it is possible that the bleomycin model is simply not the optimal model for detecting such a propensity to fibrosis with these mice.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our experiments suggest that telomerase deficiency and telomere shortening do not impact bleomycin induced lung fibrosis. Nonetheless, the findings that telomerase mutations are associated with FIP and that telomere shortening occurs in IPF are clear indications that telomerase dysfunction may play a prominent role in lung fibrosis and provide justification for an ongoing search into improved animal models to investigate this relationship.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following sources of funding: NIH NHBLI HL085406 (WEL), HL105479 (WEL), HL085317 (TSB), HL092870 (TSB), HL087738 (ALD); Vanderbilt CTSA Grant NIH NCRR UL1 RR024975; ALA Dalsemer Research Grant (WEL), Francis Families Foundation (HT), IPFNet Cowlin Career Development Award (ALD), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (WEL, TSB). HT is a Parker B. Francis Fellow in Pulmonary Research.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

All of the authors confirm that they have no competing or conflicting interests regarding the investigations and results outlined in this manuscript. All authors are employees of Vanderbilt University. In addition, Drs. Blackwell and Lawson are also supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, Lynch DA, Ryu JH, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, Ancochea J, Bouros D, Carvalho C, Costabel U, Ebina M, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kim DS, King TE, Jr, Kondoh Y, Myers J, Muller NL, Nicholson AG, Richeldi L, Selman M, Dudden RF, Griss BS, Protzko SL, Schunemann HJ. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:646–664. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.ats3-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zoz DF, Lawson WE, Blackwell TS. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disorder of epithelial cell dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:435–438. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31821a9d8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawson WE, Loyd JE, Degryse AL. Genetics in pulmonary fibrosis-familial cases provide clues to the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:439–443. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31821a9d7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele MP, Speer MC, Loyd JE, Brown KK, Herron A, Slifer SH, Burch LH, Wahidi MM, Phillips JA, III, Sporn TA, McAdams HP, Schwarz MI, Schwartz DA. Clinical and pathologic features of familial interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1146–1152. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200408-1104OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawson WE, Loyd JE. The genetic approach in pulmonary fibrosis: can it provide clues to this complex disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:345–349. doi: 10.1513/pats.200512-137TK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harley CB, Futcher AB, Greider CW. Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature. 1990;345:458–460. doi: 10.1038/345458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaziri H, Dragowska W, Allsopp RC, Thomas TE, Harley CB, Lansdorp PM. Evidence for a mitotic clock in human hematopoietic stem cells: loss of telomeric DNA with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9857–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HW, Blasco MA, Gottlieb GJ, Horner JW, Greider CW, DePinho RA. Essential role of mouse telomerase in highly proliferative organs. Nature. 1998;392:569–574. doi: 10.1038/33345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemann MT, Rudolph KL, Strong MA, DePinho RA, Chin L, Greider CW. Telomere dysfunction triggers developmentally regulated germ cell apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2023–2030. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.d’Adda dF, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, Fiegler H, Carr P, Von Zglinicki T, Saretzki G, Carter NP, Jackson SP. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, Weinrich SL, Andrews WH, Lingner J, Harley CB, Cech TR. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingner J, Hughes TR, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech TR. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armanios MY, Chen JJ, Cogan JD, Alder JK, Ingersoll RG, Markin C, Lawson WE, Xie M, Vulto I, Phillips JA, III, Lansdorp PM, Greider CW, Loyd JE. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, Xing C, Raghu G, Weissler JC, Rosenblatt RL, Shay JW, Garcia CK. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7552–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Jones BR, McMahon FB, Gleaves LA, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Repetitive intratracheal bleomycin models several features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L442–L452. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Jones BR, Boomershine CS, Ortiz C, Sherrill TP, McMahon FB, Gleaves LA, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. TGF{beta} signaling in lung epithelium regulates bleomycin-induced alveolar injury and fibroblast recruitment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L887–L897. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawson WE, Polosukhin VV, Stathopoulos GT, Zoia O, Han W, Lane KB, Li B, Donnelly EF, Holburn GE, Lewis KG, Collins RD, Hull WM, Glasser SW, Whitsett JA, Blackwell TS. Increased and prolonged pulmonary fibrosis in surfactant protein C-deficient mice following intratracheal bleomycin. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61214-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawson WE, Polosukhin VV, Zoia O, Stathopoulos GT, Han W, Plieth D, Loyd JE, Neilson EG, Blackwell TS. Characterization of fibroblast-specific protein 1 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:899–907. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1535OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Degryse AL, Li B, Han W, Sherrill TP, Plieth D, Neilson EG, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Contribution of epithelial-derived fibroblasts to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:657–665. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0322OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, Newcomb DC, Jones BR, Roldan J, Lane KB, Morrisey EE, Beers MF, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10562–10567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown S, Worsfold M, Sharp C. Microplate assay for the measurement of hydroxyproline in acid-hydrolyzed tissue samples. Biotechniques. 2001;30:38–40. 42. doi: 10.2144/01301bm06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Callaghan N, Dhillon V, Thomas P, Fenech M. A quantitative real-time PCR method for absolute telomere length. Biotechniques. 2008;44:807–809. doi: 10.2144/000112761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas P, Wang YJ, Zhong JH, Kosaraju S, O’Callaghan NJ, Zhou XF, Fenech M. Grape seed polyphenols and curcumin reduce genomic instability events in a transgenic mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Mutat Res. 2009;661:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T, Chung MJ, Ullenbruch M, Yu H, Jin H, Hu B, Choi YY, Ishikawa F, Phan SH. Telomerase activity is required for bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3800–3809. doi: 10.1172/JCI32369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hao LY, Armanios M, Strong MA, Karim B, Feldser DM, Huso D, Greider CW. Short telomeres, even in the presence of telomerase, limit tissue renewal capacity. Cell. 2005;123:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erdmann N, Liu Y, Harrington L. Distinct dosage requirements for the maintenance of long and short telomeres in mTert heterozygous mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6080–6085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401580101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alder JK, Chen JJ, Lancaster L, Danoff S, Su SC, Cogan JD, Vulto I, Xie M, Qi X, Tuder RM, Phillips JA, III, Lansdorp PM, Loyd JE, Armanios MY. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13051–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804280105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cronkhite JT, Xing C, Raghu G, Chin KM, Torres F, Rosenblatt RL, Garcia CK. Telomere shortening in familial and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:729–737. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-550OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blasco MA, Lee HW, Hande MP, Samper E, Lansdorp PM, DePinho RA, Greider CW. Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell. 1997;91:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph KL, Chang S, Lee HW, Blasco M, Gottlieb GJ, Greider C, DePinho RA. Longevity, stress response, and cancer in aging telomerase-deficient mice. Cell. 1999;96:701–712. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maser RS, DePinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Driscoll B, Buckley S, Bui KC, Anderson KD, Warburton D. Telomerase in alveolar epithelial development and repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1191–L1198. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy R, Buckley S, Doerken M, Barsky L, Weinberg K, Anderson KD, Warburton D, Driscoll B. Isolation of a putative progenitor subpopulation of alveolar epithelial type 2 cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L658–L667. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00159.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JK, Lim Y, Kim KA, Seo MS, Kim JD, Lee KH, Park CY. Activation of telomerase by silica in rat lung. Toxicol Lett. 2000;111:263–270. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fridlender ZG, Cohen PY, Golan O, Arish N, Wallach-Dayan S, Breuer R. Telomerase activity in bleomycin-induced epithelial cell apoptosis and lung fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:205–213. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00009407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Reddy R, Barsky L, Scholes J, Chen H, Shi W, Driscoll B. Lung alveolar integrity is compromised by telomere shortening in telomerase-null mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L57–L70. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90411.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson SR, Lee J, Reddy R, Williams GN, Kikuchi A, Freiberg Y, Warburton D, Driscoll B. Partial pneumonectomy of telomerase null mice carrying shortened telomeres initiates cell growth arrest resulting in a limited compensatory growth response. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L898–L909. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00409.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alder JK, Guo N, Kembou F, Parry EM, Anderson CJ, Gorgy AI, Walsh MF, Sussan T, Biswal S, Mitzner W, Tuder RM, Armanios M. Telomere Length is a Determinant of Emphysema Susceptibility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0520OC. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]