Abstract

As a result of the increasing resistance of Helicobacter pylori against first-line antibiotics, other drugs, such as quinolones, will be needed for eradication therapy in the future. We developed a real-time PCR to detect mutations in the gyrA gene associated with ciprofloxacin resistance of H. pylori, thereby contributing to the selection of patients who could be treated by ciprofloxacin-based therapy.

The recommended first-line eradication therapy against Helicobacter pylori infection consists of a triple therapy, including proton pump inhibitors, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or metronidazole (5). Increasing resistance against clarithromycin and metronidazole is compromising the eradication of H. pylori and causing failures in therapy (3), so other antibacterial drugs, such as quinolones, will be needed for H. pylori therapy in the future (1, 2, 12, 14). The resistance of H. pylori against quinolones, which exert their antimicrobial effects by affecting the A-subunit of the DNA gyrase of H. pylori, is caused by point mutations in the so-called quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the gyrA gene (8, 10, 11, 13), mainly involving amino acid substitutions at amino acid 87 (aa87) (Asn to Lys) and amino acid 91 (aa91) (Asp to Gly, Asp to Asn, and Asp to Tyr) (6, 7, 10).

The susceptibility of H. pylori against antibiotics is normally examined by Etest, which is accepted to be the reference method (4). Indeed, antimicrobial sensitivity testing of these fastidious bacteria may not be possible because of contamination and inappropriate transport conditions. Due to an increase of ciprofloxacin resistance (between 5 and 10% [unpublished data]) in Germany, we propose a molecular genetic method to quickly detect ciprofloxacin-resistant (Cipr) H. pylori organisms in patients who could be treated by a quinolone-based therapy. We selected 65 ciprofloxacin-sensitive (Cips) and 35 Cipr H. pylori isolates and used the Etest method (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) to determine the MIC of ciprofloxacin (4). Strains were classified as resistant to ciprofloxacin when the ciprofloxacin MIC for the strain was >1 mg/liter. The ciprofloxacin MICs for all sensitive strains were ≤0.19 mg/liter.

(Part of this work was presented as a poster at the XVIth International Workshop on Gastrointestinal Pathology and Helicobacter 2003, Stockholm, Sweden.)

Bacterial DNA was extracted from these strains using the QIAmp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the QRDR of the gyrA gene (GenBank accession no. AE000583) was amplified as described previously (7). After the purified amplicons were sequenced, we screened the QRDRs of our selected strains for known gyrA mutations and polymorphisms. At base triplet 87, we found two wild-type variants, an AAC triplet (39 isolates) and an AAT triplet (26 strains) (both code for Asn). Sixteen Cipr mutants harbored the AAA triplet, and eight mutants exhibited the AAG triplet (both code for Lys). At base triplet 91, the wild-type GAT triplet (coding for Asp) was detected in all Cips strains. Three Cipr mutants had the GGT triplet (coding for Gly) in combination with the wild-type AAT triplet at aa87 (aa87 AAT-WT). The three isolates harboring the TAT mutant triplet (coding for Tyr) also had the wild-type AAC triplet at aa87 (aa87 AAC-WT). Three Cipr mutants had the AAT triplet (coding for Asn), two in combination with aa87 AAT-WT and one combined with aa87 AAC-WT (Table 1). We did not see any significant association between the type of gyrA mutation and the ciprofloxacin MIC.

TABLE 1.

Results of sequencing the QRDRs of 100 H. pylori isolates (65 Cips and 35 Cipr) and melting temperatures for each pair of hybridization probes (mutation probe 87 and mutation probe 91) depending on the genotype and phenotype

| No. of strains | Triplet 87 | Triplet 91 | Phenotype (by Etest) | Genotype (by real-time PCR) |

Tma (°C) with mutation probe:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 87 | 91 | |||||

| 39 | AAC (Asn) | GAT (Asp) | Cips | Wild-type Cips | 57.0 ± 0.2 | 47.4 ± 0.2 |

| 26 | AAT (Asn) | GAT (Asp) | Cips | Wild-type Cips | 50.4 ± 0.2 | 54.7 ± 0.2 |

| 16 | AAA (Lys) | GAT (Asp) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 48.7 ± 0.2 | 49.2 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | AAG (Lys) | GAT (Asp) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 50.8 ± 0.2 | 51.5 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | AAT (Asn) | GGT (Gly) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 50.4 ± 0.2 | 58.5 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | AAC (Asn) | TAT (Tyr) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 57.0 ± 0.2 | 44.6 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | AAT (Asn) | AAT (Asn) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 50.4 ± 0.2 | 52.0 ± 0.2 |

| 1 | AAC (Asn) | AAT (Asn) | Cipr | Mutant Cipr | 57.0 ± 0.2 | 44.6 ± 0.2 |

| 2 mixed infectionsb | AAC (Asn) | GAT (Asp) | Cipr | Wild-type Cips | 57.0 ± 0.2 | 47.4 ± 0.2 |

| AAA (Lys) | GAT (Asp) | Mutant Cipr | 48.7 ± 0.2 | 49.2 ± 0.2 | ||

Tm, melting temperature. Melting temperatures can vary slightly between different runs, so the temperatures given are means ± standard deviations for more than 30 runs.

By real-time PCR, two mixed isolates with Cips and Cipr isolates were detected.

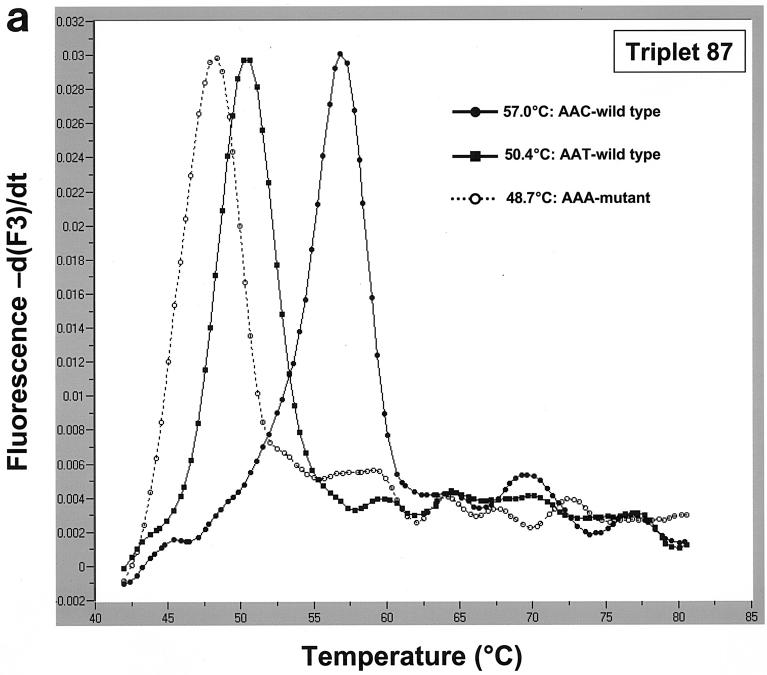

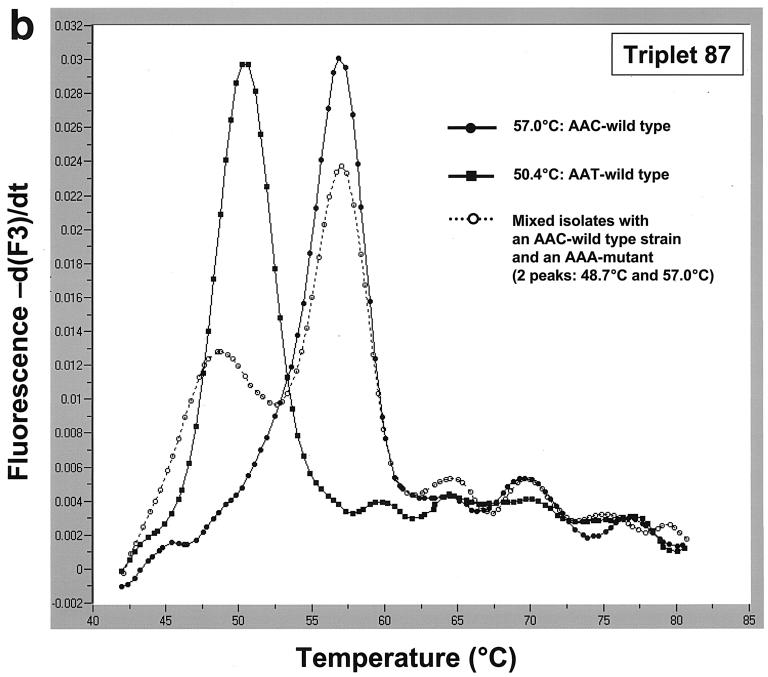

Based on the results of this analysis, two pairs of hybridization probes were designed to detect aa87 and aa91 mutations. To detect aa87 mutations, we used anchor probe 87 (5′-AAAAATCTTGCGCCATTCTCACTAGCGC-3′; 3′ end labeled with fluorescein) and mutation probe 87 (5′-ATAAACGGCGTTATCGCCA-3′; 5′ end labeled with LightCycler red 705 and 3′ end phosphorylated). aa91 mutations were detected using anchor probe 91 (5′-AAAAATCTTGCGCCATTCTCACTAGCG-3′; 3′ end labeled with fluorescein) and mutation probe 91 (5′-ACCATAAACGGCATTATCGCCA-3′; 5′ end labeled with LightCycler red 640 and 3′ end phosphorylated). Real-time PCR and subsequent melting curve analysis were performed in 20-μl capillary tubes using a LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Using the triplet 87 hybridization probes, we were able to identify the two wild-type triplets (AAC and AAT) and the Cipr AAA mutants at triplet 87 by analyzing their melting temperatures. The aa87 AAC-WT, whose sequence matched that of mutation probe 87 perfectly, showed the highest melting temperature (57°C); the melting temperatures of the aa87 AAT-WT (50.4°C) and the aa87 AAA mutant (48.7°C) were decreased than that of the aa87 AAC-WT (Fig. 1a). We also detected two mixed isolates with a Cips strain and a Cipr strain exhibiting the AAA mutation (Fig. 1b).

FIG. 1.

(a) Melting curve analysis and detection of strains with two aa87 wild-type triplets and aa87 AAA Cipr mutant triplets in the QRDRs of the gyrA gene using mutation probe 87 (and anchor probe 87). Mutation probe 87 matches the aa87 AAC-WT (melting temperature, 57°C). Compared to DNA from the strain with the wild-type AAC triplet, DNA from the strains with wild-type AAT and the AAA mutant triplets had different binding properties to the hybridization probes, resulting in decreased melting temperatures of 50.4°C (AAT-WT) and 48.7°C (AAA mutant). (b) Detection of mixed isolates with a Cips strain and a Cipr strain. While the melting curves of strains with the two wild-type aa87 triplets showed one peak only (57 and 50.4°C), a curve exhibiting two peaks indicated an infection with at least two strains, in our example, an infection with a resistant strain (aa87 AAA mutant) and a susceptible strain (aa87 AAC-WT) with melting temperatures of 57 and 48.7°C, respectively.

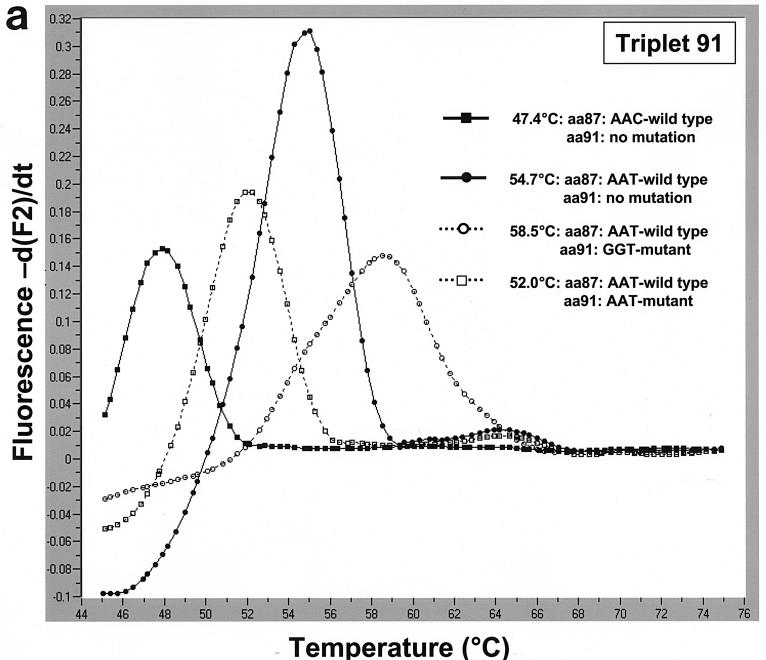

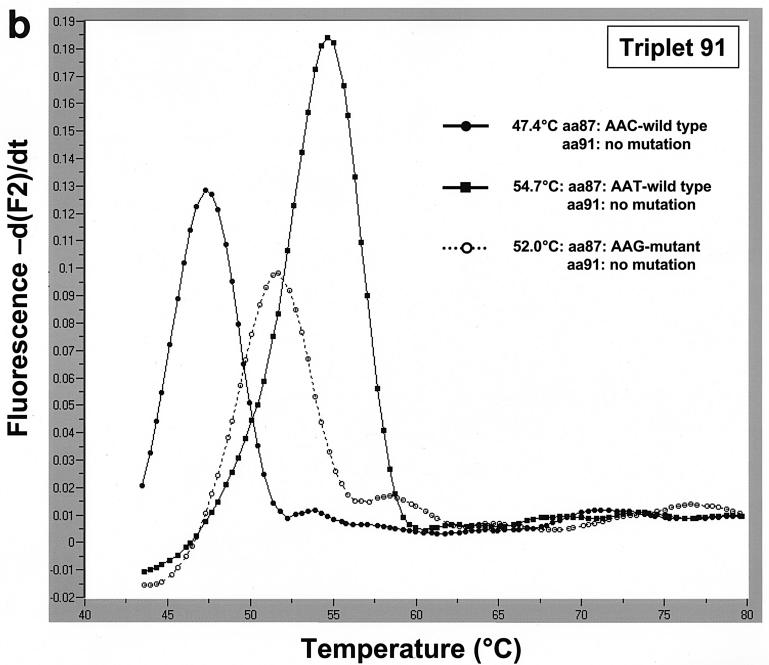

The triplet 91 hybridization probes were designed to detect aa91 mutants. Mutation probe 91 matched aa91 GGT mutants and the aa87 AAT-WT exactly. Strains with aa87 AAT-WT had the highest melting temperature (58.5°C), followed by strains with aa91 AAT mutant triplet combined with the aa87 AAT-WT triplet (52.0°C). We were also able to discriminate between the mutants and the two wild-type aa87 variants (Fig. 2a). Three isolates with an aa91 TAT mutation and the single isolate with an aa91 AAT mutation all also had aa87 AAC-WT and, not surprisingly, had a much lower melting temperature than the strain with aa87 AAC-WT did (data not shown). The aa87 AAG mutants were easily detected with the triplet 91 hybridization probes, revealing a melting temperature of 51.5°C (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

(a) Using mutation probe 91, strains with aa87 AAT-WT and an aa91 GGT mutation in the QRDR of the gyrA gene had the highest melting temperature at 58.5°C. Strains with aa87 AAT-WT and an aa91 AAT mutation had a decreased melting temperature of 52.0°C. The ciprofloxacin-sensitive wild-type strains had melting temperatures of 54.7°C (aa87 AAT-WT) and 47.4°C (aa87 AAC-WT). (b) Accurate discrimination between the aa87 AAT-WT and the aa87 AAG mutant is possible using mutation probe 91 (and anchor 91). By using this pair of probes, both wild-type triplets at aa87 (AAC-WT, 47.4°C; AAT-WT, 54.7°C) and the aa87 AAG mutant (51.5°C) can be discriminated.

In order to select the patients who could be treated with a quinolone-based eradication treatment, susceptibility testing of H. pylori is desirable, particularly in patients already treated unsuccessfully. Contamination or growth failure of the fastidious H. pylori can impair conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing. To overcome such problems, we established this real-time PCR assay based on a combination of two pairs of hybridization probes in order to detect gyrA mutations and to predict possible ciprofloxacin resistance. Our assay recognized mutations in the QRDR and was able to distinguish all 35 Cipr and Cips strains. The differentiation between aa91 TAT and AAT mutants (combined with an aa87 AAC-WT) was complicated because of their similar melting temperatures. In our opinion, this fact is of reduced clinical impact, because both mutations are associated with the ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype. These two mutants could be discriminated by using an additional mutation probe matched to one of these mutants. Double mutations affecting aa91 and aa97 have also been reported (7) but were not found in our strain collection. Geographical variation of ciprofloxacin resistance mechanisms and the possible existence of alternative resistance mechanisms in H. pylori that are different from gyrA mutations cannot be excluded but have not been reported thus far.

In conclusion, we developed a reliable fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based real-time PCR to detect ciprofloxacin-resistant H. pylori strains with a view to select patients who could be treated with a quinolone-based eradication regimen. The method was developed on DNA extracts from H. pylori isolates from German patients, but it might also be performed directly on gastric specimens. Because of the known genetic heterogeneity of H. pylori (9), the assay may fail with strains isolated outside Germany, but the test could be altered to adapt to the genetic gyrA variants found in different geographical regions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant to M. Kist (1369-239) from the Robert-Koch-Institut of the German Federal Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cammarota, G., R. Cianci, O. Cannizzaro, L. Cuoco, G. Pirozzi, A. Gasbarrini, A. Armuzzi, M. A. Zocco, L. Santarelli, F. Arancio, and G. Gasbarrini. 2000. Efficacy of two one-week rabeprazol/levofloxacin-based triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14:1339-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Caro, S., M. Assunta Zocco, F. Cremonini, M. Candelli, E. C. Nista, F. Bartoluzzi, A. Armuzzi, G. Cammarota, I. Santarelli, and A. Gasbarrini. 2002. Levofloxacin based regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14:1309-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glupczynski, Y., F. Mégraud, M. Lopez-Brea, and L. P. Andersen. 2001. European multicentre survey of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:820-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heep, M., M. Kist, S. Strobel, D. Beck, and N. Lehn. 2000. Secondary resistance among 554 isolates of Helicobacter pylori after failure of therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:538-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfertheiner, P., F. Mégraud, C. O'Morain, A. P. S. Hungin, R. Jones, A. Axon, D. Y. Graham, G. Tytgat, and The European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group (EHPSG). 2002. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht 2-2000 Consensus Report. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 16:167-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mégraud, F. 1998. Epidemiology and mechanism of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 115:1278-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore, R. A., B. Beckthold, S. Wong, A. Kureishi, and L. E. Bryan. 1995. Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene and characterization of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:107-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reece, R. J., and A. Maxwell. 1991. DNA gyrase: structure and function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 26:335-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suerbaum, S. 2000. Genetic variability in Helicobacter pylori infection. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, G., T. J. Wilson, Q. Jiang, and D. E. Taylor. 2001. Spontaneous mutations that confer antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:727-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, Y., W. M. Huang, and D. E. Taylor. 1993. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Campylobacter jejuni gyrA gene and characterization of quinolone resistance mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:457-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia, H. H., B. C. Yu Wong, N. J. Talley, and S. K. Lam. 2002. Alternative and rescue treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 3:1301-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1271-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zullo, A., C. Hassan, V. De Francesco, R. Lorenzetti, M. Marignani, S. Angeletti, E. Ierardi, and S. Morini. 2002. A third-line levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig. Liver Dis. 35:232-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]