Summary

Blimp-1 is the master regulator of plasma cell development, controlling genes such as J-chain and secretory Ig heavy chain. However, some mammalian plasma cells do not express J-chain, and mammalian B1 cells secrete “natural” IgM antibodies without upregulating Blimp-1. While these results have been controversial in mammalian systems, here we describe subsets of normally occurring Blimp-1- antibody secreting cells in nurse sharks, found in lymphoid tissues at all ontogenic stages. Sharks naturally produce large amounts of both pentameric (classically ‘19S’) and monomeric (classically ‘7S’) IgM, the latter an indicator of adaptive immunity. Consistent with the mammalian paradigm, shark Blimp-1 is expressed in splenic 7S IgM-secreting cells, though rarely detected in the J-chain+ cells producing 19S IgM. Although IgM transcript levels are lower in J-chain+ cells, these cells nevertheless secrete 19S IgM in the absence of Blimp-1, as demonstrated by ELISPOT and metabolic labeling. Additionally, cells in the shark bone marrow equivalent (epigonal) are Blimp-1-. Our data suggest that, in sharks, 19S-secreting cells and other secreting memory B cells in the epigonal can be maintained for long periods without Blimp-1, but like in mammals, Blimp-1 is required for terminating the B cell program following an adaptive immune response in the spleen.

Keywords: Transcription factors, B cells, Immunoglobulins, Evolution, Lymphoid organs

Introduction

In jawed vertebrates, or gnathostomes, transmembrane (TM) IgM is the antigen receptor on naïve B cells, and plasma cells secrete multimeric (tetramer, pentamer, or hexamer) IgM. Secretory IgM is produced predominantly by B1 cells in mammals, comprising the majority of “natural,” polyreactive antibody that is present in both normal mice and animals raised in germfree conditions [1-7]. Conversely, “immune” secretory IgM is secreted by the relatively short-lived plasma cells of the B2 lineage [8]. In mice, approximately half of all secreted IgM is “natural” IgM, which is produced predominantly by bone marrow B1 cells, while the rest is B2-cell derived IgM [3, 9]. For B2 cells that form germinal centers, activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) expression induces somatic hypermutation (SHM) and class-switch recombination (CSR), resulting in class-switched cells that secrete high-affinity, non-IgM isotypes (IgG/A/E) possessing different effector functions [10, 11].

Cartilaginous fish, including sharks, skates, rays, and ratfish are the oldest living animals with an adaptive immune system featuring an Ig-based BCR, along with TCR and MHC. Despite 450 million years of divergence from mammals, cartilaginous fish have both TM and secretory forms of IgM H chains [12, 13]. Besides the pentameric form of secreted IgM classically called ‘19S,’ shark B cells also secrete a monomeric form, classically ‘7S’ [14-18]. 7S IgM is thought to be a mammalian IgG equivalent, both with respect to its ability to penetrate extravascular spaces and its enhanced binding strength late in adaptive immune responses, whereas previous work also suggested that 19S IgM does not participate in antigen-specific responses [19, 20].

In addition to IgM, there are three other Ig H chain isotypes expressed in nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum): IgM1gj, an H chain encoded by an invariant “germline-joined” variable (V) gene and lacking the second constant domain (C2) found in conventional IgM [21]; IgW, related to mammalian IgD but having an unknown function in sharks [22-24]; and IgNAR, an H-chain-only isotype unique to cartilaginous fish [25]. In newborn nurse sharks, almost all of the serum Ig is composed of IgM1gj, and some 19S IgM. Low levels of serum 7S IgM appear around 8 days after birth and rise throughout development [26]. By adulthood there is very little serum IgM1gj, and 19S and 7S IgM are present in roughly equal proportions.

Whether or not shark plasma cells secrete 19S or 7S IgM seems to be dependent upon the expression of the joining chain (J-chain) [27]. J-chain is involved in Ig mulitimerization in mammals, but unlike sharks, mammalian IgM is secreted as disordered oligomers rather than monomers in J-chain knockout mice [28-32]. Mammalian IgA, however, is secreted either as a dimer with J-chain (in mucosae) or as a monomer is the absence of J-chain (in serum) [33, 34]. In addition to multimerization, J-chain is required for Ig transport across the mucosal epithelium in tetrapods: the C-terminal domain of mammalian J-chain is necessary for association with the secretory component (SC), a portion of the poly-Ig receptor (pIgR) that remains associated with IgA and IgM after transcytosis across the mucosal epithelium [35]. The homologous region of shark J-chain, however, is divergent in sequence and lacks amino acid residues that play a role in binding to SC [27]. When combined with the absence of reported shark SC and the lack of J-chain expression in plasma cells in the shark intestinal lamina propria (unpublished), the major role of shark J-chain is likely for IgM mulitimerization rather than Ig transport.

In mammals J-chain is upregulated in all Ig-secreting cells as part of the plasma cell transcriptional program, but in sharks it should only be expressed by 19S-secreting cells. To gain insight into the regulation of J-chain expression in these cells, we have examined expression of canonical B cell/plasma cell transcription factors in nurse sharks, especially B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1 (Blimp-1), the master regulator of plasma cell development in mammals [36]. Blimp-1, encoded by the gene prdm1, is one of the two founding members of the multi-gene prdm family (along with prdm2/RIZ1) [37]. These two homologs are the only members present in invertebrates. The family was greatly expanded in vertebrates, and there is a primate-specific prdm member. All prdm family members contain similar domain structures including a PR domain and zinc (Zn)-finger domains. The N-terminal PR domain is 20-30% similar to a SET domain, and also like a SET domain, can function as a methyltransferase in some members [37-40]. The multiple C-terminal Zn-finger domains aid in protein-protein interactions, and are present in all but one of the prdm genes [37].

The working model of Blimp-1 function in plasma cells involves a combination of cessation of the cell cycle and repression of the “master regulator” of B cell development, Pax5, a transcription factor that suppresses expression of non-B cell genes [43-46]. Downregulation of Pax5 results in de-repression of genes required for Ig secretion and the plasma cell phenotype, including XBP1, J-chain, and the upregulation of IgH/L transcription [46-54]. Blimp-1, while most frequently associated with plasma cells, also functions in the differentiation of many other cell types including primordial germ cells [55, 56], dendritic cells [57], osteocytes [58, 59], myeloid cells [60], T cells [61-66] and NK cells [67]. For example, Blimp-1 is expressed in CD8+ effector T cells, and involved in survival and terminal differentiation [66]. Pax5 and Blimp-1have also been studied in another non-mammalian model, the teleost fish, where they have been shown to play similar roles to their mammalian counterparts [68]. Unfortunately, teleost fish have lost J-chain and thus its regulation cannot be examined in this taxon.

In support of the model that Blimp-1 is obligatory for plasma cell function; mice lacking Blimp-1 in the B cell lineage have low (but detectable) levels of serum Ig [36, 51]. The canonical view is that Blimp-1-negative cells have increased levels of Pax5 and decreased Ig secretion, and that for B1 as well as B2 cells, Blimp-1 is required for the plasma cell program [69-71]. However, the role of Blimp-1 in antibody secretion from B1 cells is controversial, and as mentioned, there are still detectible levels of secreted IgM in Blimp-1 knockout mice [36, 51]. Additionally, others have shown that there is no augmentation of Blimp-1 expression in antibody-secreting B1 cells, and that, even in the absence of Blimp-1, Pax5 expression is downregulated [72]. Finally, it has been shown that Pax5 is also downregulated in early B2 plasmablasts, and that even in the absence of Blimp-1, antibody secretion is initiated in these cells [70].

In this paper, we first embark on determining whether the forms of shark serum IgM would correlate with the types of plasma cells found in shark lymphoid tissues, primarily the spleen (the only shark secondary lymphoid tissue) and epigonal (the shark bone marrow equivalent). Based on the ontogenic appearance of 19S and 7S IgM in plasma, we predicted that all secretory cells in neonates would express the J chain, followed by distinct subsets of J-chain+ and J chain- cells in adulthood. We also initiated studies of classical B cell transcription factors in sharks, predicting that Blimp-1 would be expressed in all secretory cells, whether or not they expressed the J-chain. Our results conformed well to the first prediction of the types of neonatal and adult plasma cells, but not in the predicted expression of Blimp-1. We discuss our data in sharks within the greater context of Blimp-1 expression in B cells subsets in all vertebrates.

Results

Changes in IgM and J-chain expression in nurse shark spleen throughout development

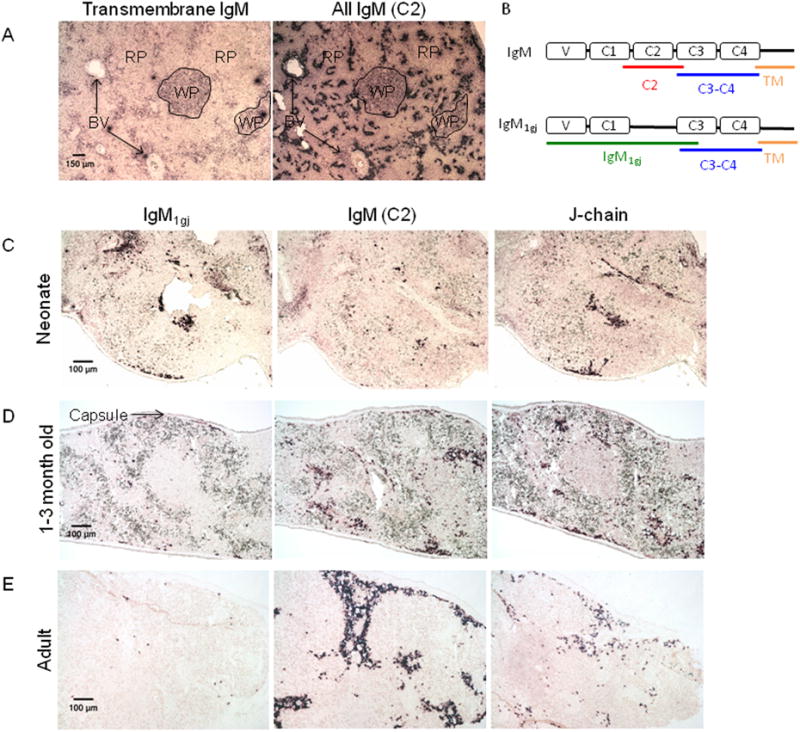

As described, neonatal shark serum contains predominantly 19S IgM, along with IgM1gj, an IgM isotype that has a pre-rearranged (“germline-joined”) V domain [21]. 7S IgM is absent from sera during early development, but 7S IgM levels increase steadily as the animals age, so that by adulthood serum IgM is comprised of roughly equal levels of 19S and 7S IgM and negligible IgM1gj [26]. To examine how IgM expression at the cellular level matches the IgM composition in serum, we performed in situ hybridization using spleen tissue at different developmental points. The spleen is the only fish secondary lymphoid tissue, and in nurse sharks it contains both red pulp and white pulp (illustrated in figure 1A), the latter composed of T and B cell zones [74]. In contrast to the low IgM signal observed in white pulp B cell zones, we have classified IgM+ cells localized near red pulp blood vessels or along the splenic capsule as antibody-secreting cells based on their intense IgM signal. This difference in staining intensity is clear when riboprobes specific for either the TM or constant domains (C2 or C3/C4) of IgM are used. TM probes only stain B cell zones with low intensity, whereas C-specific probes intensely label cells near blood vessels and stain the white pulps weakly (figure 1A). Using riboprobes specific for IgM1gj, ‘conventional’ 7S and 19S IgM (exon encoding the C2 domain, lacking in IgM1gj: figure 1B), or J-chain, which presumably discriminates between the 19S- and 7S-secreting cells, we have examined these secretory B cell populations throughout development (figure 1).

Figure 1. Expression of immunoglobulin genes in nurse shark spleen tissue throughout development.

(A) In situ hybridization of 8μm (non consecutive) sections of spleen tissue from an adult shark (shark W), stained with riboprobes specific for IgM-TM (left) or the C2 domain of IgM (right). Regions of white pulp B cell zones (WP), red pulp (RP) and blood vessels (BV) are marked. Each photo was taken at 4× magnification, and shown with 150 μm scale bar. (B) Schematic mockup of domain structure of IgM and IgM1gj with approximate probe position marked. A red line indicates the position of conventional IgM-specific C2-domain-specific probe, blue line is a C3-C4 domain-specific probe that detects both IgM and IgM1gj, the green line is an IgMigj specific probe and the orange line indicates the location of a TM probe. (C-E) In situ hybridization of 8μm (non consecutive) sections of spleen tissue from three sharks ages: 5 days (shark TH) (C), 1-2 months (shark LA) (D), and adult (shark LJ) (E). Probes are specific for: IgM1gj (left), C2-domain of conventional IgM (middle), and J-chain (right). All photos were taken at 10× magnification and one image from each tissue shown with 100 μm scale bar. Each shark is representative of at least one other shark of that age (data not shown). Positive staining is purple. Negative controls with sense probes showed no staining (not shown).

In young animals (5 days post-partum and one-three months old) the number and location of cells expressing J-chain correlate well with the number of IgM- plus IgM1gj-secreting cells (figure 1C, D); thus, all IgM+ cells in these young animals are J-chain+ and IgM1gj was the predominant species expressed in a 5 day-old animal. At this stage, the few cells expressing canonical IgM H chains were not associated with the capsule or blood vessels where the IgM1gj+ cells were found. By one-three months of age, more canonical IgM-expressing cells were detected, localized near blood vessels and the capsule with the existing IgM1gj-expressing cells (figure 1D). By the time sharks reached 1 year of age, very few splenic IgM1gj –producing cells were observed. Since the total number of IgM+ cells greatly exceeded the number of J-chain+ cells at this stage, only a portion of all adult IgM+ cells must co-express J-chain (figure 1E).

Our in situ hybridization results concur with previously reported serum levels of IgM1gj, 19S IgM, and 7S IgM: neonatal/young shark plasma cells express either IgM1gj or 19S IgM (both J-chain+); by one year of age splenic IgM1gj expression is extinguished and only ∼half of IgM-secreting cells are J-chain+ (19S-producers) and the rest J-chain- (presumed 7S-producers). To study the control of splenic J-chain expression, we began by examining expression of the “master regulator” of plasma cell development, Blimp-1, by in situ hybridization.

Cloning of shark Blimp-1

The full-length sequence of nurse shark Blimp-1 gene, prdm1, was amplified from spleen RNA using primers to the Zn-finger rich region from Xenopus laevis prdm1 (green highlighted region, supplemental figure 1), and used to probe a nurse shark cDNA library [75, 76] to obtain the full-length sequence (supplemental figure 1). The nurse shark sequence contains all major domains found in mammalian Blimp-1, including the PR domain and four zinc-finger domains (supplemental figure 1). The conserved domain structure within nurse shark Blimp-1 is also apparent when aligned to Blimp-1 from several other vertebrates (supplemental figure 2). A Blastp search matched nurse shark Blimp-1 to that of other vertebrate species with >60% aa similarity (E-values 0 in full-length), with highest conservation (nearly identical) in the Zn-finger domains (supplemental figure 2). To confirm its orthology, we performed phylogenetic tree analysis. We selected 3 prdm genes (PRDM4, 10, and 15) that are closely related to Blimp-1/prdm1 [37] and used PRDM2 as the outgroup. The nurse shark sequence clusters with those of Blimp-1 from other species rather than with other members of the prdm gene family (supplemental figure 3) and the nurse shark gene is the Blimp-1/prdm1 ortholog.

Blimp-1 is not expressed in a population of neonatal and adult IgM secreting cells

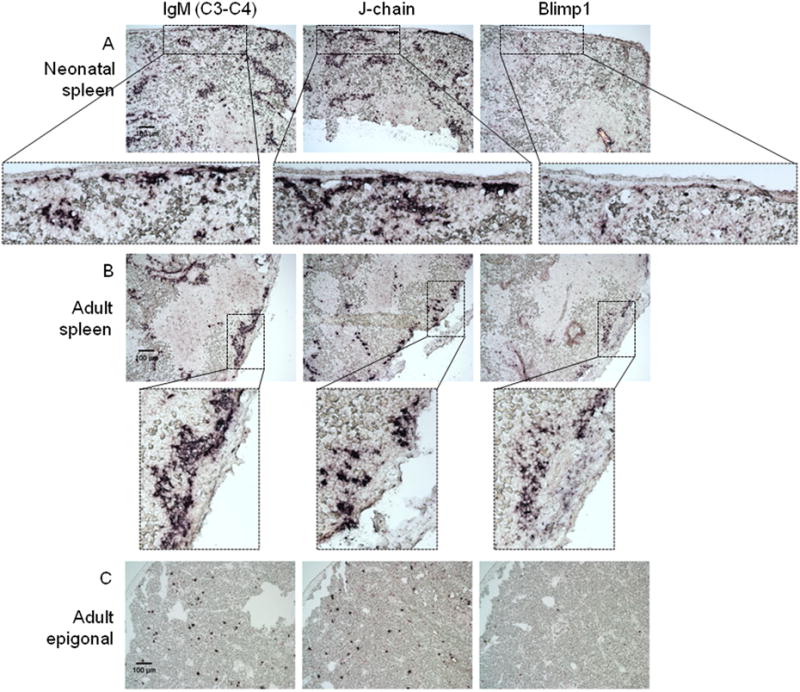

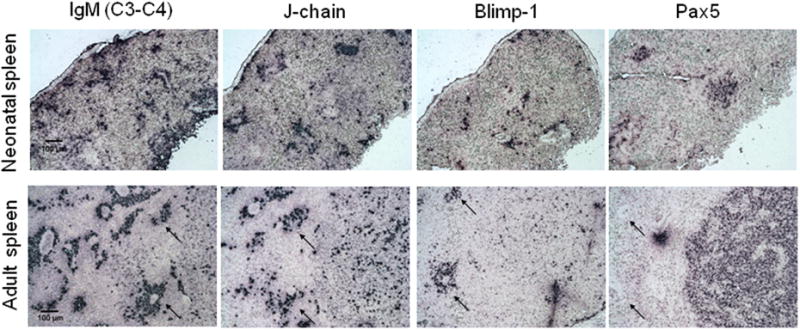

In mammals, Blimp-1 is thought to be absolutely required for plasma cell development and function; it indirectly induces J-chain expression by repressing Pax5, a negative regulator of the J-chain promoter [48]. Thus, we were surprised to find that the majority of J-chain+/IgM+ and J-chain+/IgM1gj+cells in neonatal spleen were Blimp-1- by in situ hybridization (figure 2A, table 1); note specifically the absence of Blimp-1 staining in the neonatal splenic capsule (dashed box inset) where many IgM1gj and 19S-secreting cells were found (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2. Expression of IgM, J-chain and Blimp-1 in adult nurse shark spleen and epigonal tissue.

In situ hybridization of 8μm (non consecutive) sections from spleen (A and B) or epigonal (C) tissue from neonatal (shark LA) (A) or adult (shark EL) (B and C) nurse sharks. Probes are specific for: IgM C3-C4 (left), which recognizes both IgM1gj and rearranging IgM, J-chain (middle) or Blimp-1 (right). Images taken at 10× magnification with 100 μm scale bar indicated in C3-C4 stain. Dotted boxes represent insets of 3× digital zoom from each 10× image. Positive staining is purple. Negative controls with sense probes showed no staining (not shown). Data are representative of at least 2 experiments for each stain set and age.

Table 1. Summary of J-chain and Blimp-1 expression in Ig-secreting cells.

The table summarizes in situ hybridization data from figures 3-5 and 7, encompassing expression in the neonatal spleen along with adult spleen and epigonal tissue. (+) indicates presence of transcript by in situ hybridization, (-) indicates no expression was detected by in situ and (N/A) indicates that the cell type in question is not present in said tissue.

| J-chain | Blimp-1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Neonatal spleen | 19S IgM | + | - |

| IgM1gj | + | - | |

| 7S IgM | n/a | n/a | |

| IgW | n/a | n/a | |

|

| |||

| Adult spleen | 19S IgM | + | - |

| IgM1gj | n/a | n/a | |

| 7S IgM | - | + | |

| IgW | +/- | ? | |

|

| |||

| Epigonal | 19S IgM | n/a | n/a |

| IgM1gj | + | - | |

| 7S IgM | - | - | |

| IgW | + | - | |

Unlike neonatal sharks, Blimp-1 was expressed in adult spleen, but the number of Blimp-1+ cells was lower than the IgM-secreting cells (figure 3B). As mentioned, J-chain transcripts were also expressed in only about half as many adult cells as IgM (figure 1E and 2B). By inference from the young sharks, we predicted that there would be a J-chain+/Blimp-1- 19S-secreting cell population in adults (Table 1). In this scenario, Blimp-1+ cells would therefore be the J-chain-, 7S IgM-secretors, like conventional mammalian plasma cells. However, since splenic IgM-secreting cells formed large clusters under the splenic capsule and near blood vessels, it was difficult to determine whether, as predicted, Blimp-1- cells were truly J-chain+ and vice versa.

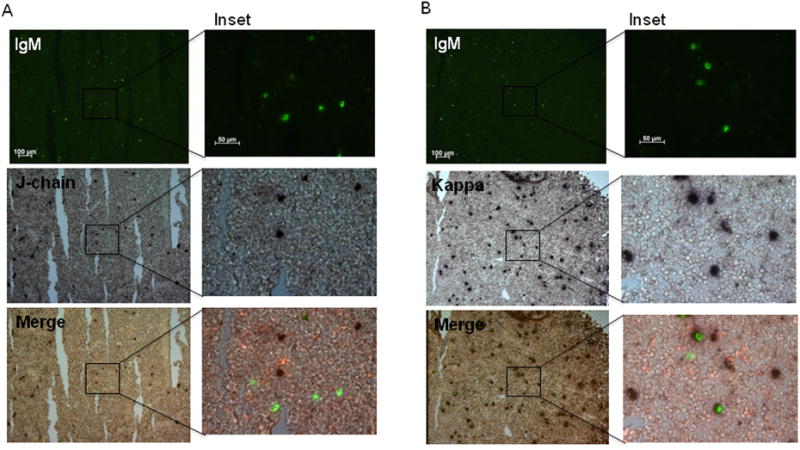

Figure 3. Co-expression of IgM with either J-chain or IgLκ in epigonal tissue.

In situ hybridization of 8μm sections of epigonal tissue from an adult shark (shark W), double-stained with either IgM-DIG and J-chain-FLU (A) or IgM-DIG and Kappa light chain-FLU probes (B).IgM-positive cells (top) are green, and positive staining for J-chain (A) or IgLκ (B) staining (middle) is purple. Images are merged at bottom. Images on the left were taken at 10× magnification with 100 μm scale bar shown in IgM stain, and insets on the right are at 40× magnification with 50 μm scale bars. Black boxes denote the regions of magnified insets. Negative controls with sense probes showed no staining (not shown). Data are representative of at least 2 experiments for each stain set and age.

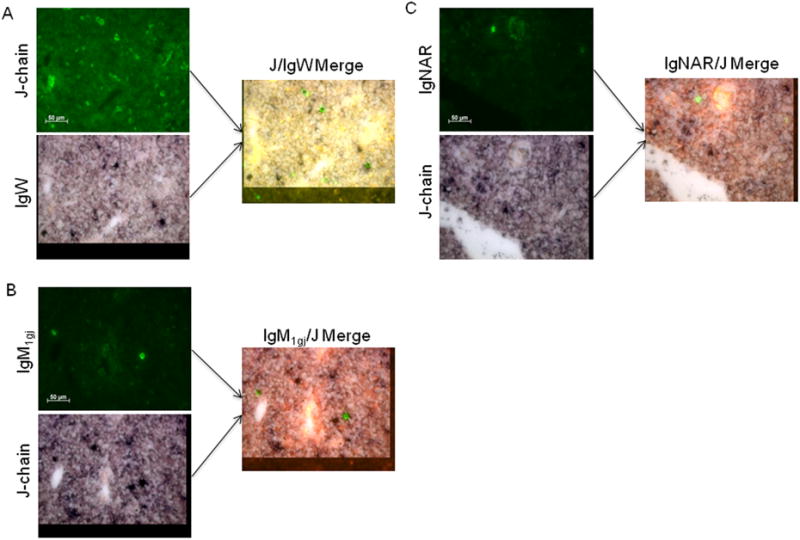

Due to this dense clustering of splenic plasma cells, we decided to study Blimp-1 and J-chain expression in another lymphoid organ. The epigonal organ is a primary lymphoid tissue, the shark bone marrow equivalent. Since plasma cells are evenly dispersed throughout this tissue, this tissue seemed ideal for examining Blimp-1 expression in individual secreting cells. However, none of the epigonal IgM+ or J-chain+ cells expressed Blimp-1 (figure 2C, table 1). Approximately equal numbers of epigonal IgM+ and J-chain+ cells were present, suggesting that all plasma cells in this tissue were IgM+/J-chain+/Blimp-1-. However, upon closer examination of consecutive sections and with in situ hybridization double staining, most of the epigonal IgM+ cells were J-chain- (figure 3A). Thus, surprisingly, all of the IgM+ cells were J-chain- in this tissue, and none of them expressed Blimp-1 (figure 2C, table 1). In addition to IgM and IgM1gj, nurse sharks also express two other Ig isotypes, IgW and IgNAR. Since there were about twice as many IgLκ+ plasma cells in the epigonal tissue as there were IgM+ secreting cells (figure 3B), it was likely that the IgM-/J-chain+ cells expressed another H chain isotype. As IgNAR does not associate with L chains, it was predicted that the J-chain+ cells expressed IgW. Indeed, the majority of epigonal J-chain+ cells did co-express IgW (figure 4A). Some J-chain+/IgM1gj+ cells were also found in the adult epigonal, but the IgNAR cells were all J-chain- (figure 4B and C). Therefore, although the composition of plasma cells in the epigonal and spleen is quite different, Blimp-1- secreting cells are found in both lymphoid tissues. Specifically, J-chain+ plasma cells in both organs lack Blimp-1, but these cells co-express predominantly IgW in the epigonal and IgM in the spleen. Also, the epigonal contains Blimp-1-/IgM+/J-chain- cells whereas these cells are predicted to be Blimp-1+ in the spleen (see Discussion and table 1). Regardless of this major difference in Blimp-1 expression between IgM+/J-chain- cells in adult spleen and epigonal, we emphasize that similar to young animals, adult secretory cells can be Blimp-1- and J-chain expression is not regulated by Blimp-1.

Figure 4. Co-expression of J-chain and non-IgM isotypes in epigonal tissue.

In situ hybridization of 8 μm sections of epigonal tissue from an adult shark (shark W), double stained with J-chain-DIG and IgW-FLU (A), IgNAR-DIG and J-chain-FLU (B), or IgM1gj-DIG and J-chain-FLU (C) probes. Cells positive for DIG-labeled probes (left) stain green. Cells positive for FLU-labeled probes (middle) stain purple. Images are merged at right. All photographs were taken at 40× magnification with 50 μm scale bar marked. Negative controls with sense probes showed no staining (not shown).

Secretion of IgM protein

Although shark plasma cells express high levels of IgM RNA and lack TM IgM mRNA (figure 1A), studies so far have focused solely on mRNA expression. Therefore, we wanted to determine whether Blimp-1- cells truly secrete 19S IgM and IgM1gj. In order to examine protein secretion together with Blimp-1 and/or J-chain expression in the adult, we would need to isolate live 19S and 7S secreting cells. Unfortunately, mAbs that would unambiguously identify these populations or the secreted product are not available, and thus we focused on IgM1gj-secreting cells from young animals, which are also Blimip-1-/J chain+ (figure 2A).

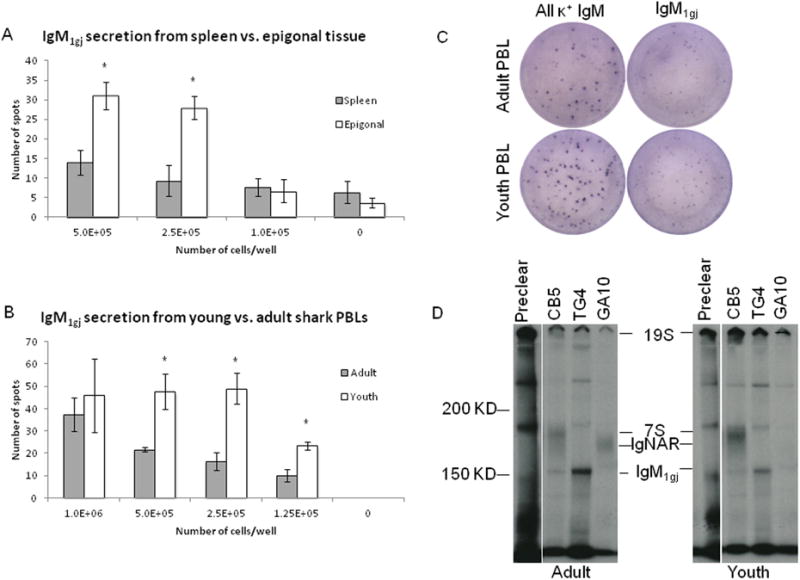

ELISPOTs were performed using plasma cell-enriched percoll fractions from spleen or epigonal tissue of a shark that was approximately 1 year old. In this assay secreted Ig was captured with the IgM1gj–specific mAb, TG4, and detected with biotinylated mAb GA16, which also binds to IgM1gj [21]. Significantly more IgM1gj-secreting cells were detected from epigonal than from spleen when at least 2.5×105 cells/well were plated. Average positive spots +/- SEM at this dilution of spleen cells was 9.3 +/- 3.9, whereas epigonal cells yielded 28 +/- 3 spots per well (p value= 0.01) (figure 5A). Presence of IgM1gj-secreting cells in the epigonal, but not spleen, of adult sharks is consistent with a previous study of Ig expression in the epigonal organ [21] and in situ hybridization data from another shark of this age (figure 1E). We were also able to detect conventional IgM secreted from epigonal cells via ELISPOT (data not shown); since all epigonal secretory B cells are Blimp-1- (figure 2C), and previous work demonstrated that Ig is secreted from epigonal cells [21], these cells clearly secrete Ig in the absence of Blimp-1 expression.

Figure 5. IgM1gj protein secretion.

Number of positive ELSPOTS using cells from spleen (grey bars) or epigonal (white bars) tissue from a 1 year old shark (shark EN), where secreted Ig was captured with anti-IgM1gj mAb, TG4 and detected with biotinylated mAb, GA16 (A). IgM1gj secretion from PBLs was also measured by ELISPOT using blood from an adult (shark B, grey bars) or young (shark R, white bars) shark, LK14 capture, and biotinylated TG4 detection (B). Each data point represents triplicate cell platings for that condition and (*) indicates p-value of less than 0.05 (T-test). Error bars signify SEM. Representative ELISPOT wells of secreted IgM1gjfrom (B) or from CB5-coated, LK14-biotin detected Ig are shown in (C). Immunoprecipitations were performed on radiolabeled supernatants from the same cells used in (B) and (C). Samples from protein G preclears or immunoprecipitations with CB5 (anti-IgM), TG4 (anti-IgM1gj) or GA10 (anti-NAR) were run non-reduced on 5% gels and film was exposed for 1 week (D) [21].

IgM1gj-secreting cells were also detected in the blood of both a young (∼6 month old) and adult (9 year old) shark, although significantly more IgM1gj-secreting cells were found in the blood of the young animal than the adult (p values = 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 for 1.25×105 cells/well, 2.5×105 cells/well, 5×105 cells/well respectively) (figure 5B). There was less of this secreted IgM1gj, (captured with anti-light chain mAb, LK14 and detected with IgM1gj-specific, biotinylated TG4) than total conventional IgM (CB5 capture, LK14-biotin detection) in both of these sharks, and the size of the IgM1gj spots was smaller (figure 5C), which could indicate that these Blimp-1-, IgM1gj-secreting cells are producing less protein than conventional IgM-secretors. Since there are no IgM1gj-secreting cells in the spleen of adult sharks (figure 1E) [21], it was surprising to find a substantial amount in the blood of an adult shark. However, immunoprecipitation with TG4 of radiolabeled PBL cell supernatants from the same 6 month and 9 year old sharks confirmed this IgM1gj secretion (figure 5D). In addition to IgM1gj, 19S and 7S IgM were seen in both sharks after immunoprecipitation with mAb CB5, and a large amount of 19S IgM was also depleted during preclear with protein G beads, which is expected due to the “stickiness” of high avidity 19S [20]. There was little IgNAR secreted from cells in the young animal (GA10 IP), which is consistent with its age. Since, there is negligible IgM1gj in the spleen of adult sharks it is possible that these secreting cells may be trafficking through the blood from the epigonal organ.

Pax5 is not expressed in any secretory cells

As mentioned, Blimp-1 represses Pax5 in mammalian plasma cells resulting in a plethora of effects [77], including up-regulation of J-chain expression; however, since many shark Ig-secreting cells do not express Blimp-1, we wondered whether Pax5 might not be extinguished in these cells, similar to what has been reported for some mammalian secretory cells [72]. Pax5 was expressed in the splenic B cell zones of both neonatal and adult nurse sharks, but no staining was detected areas where plasma cells congregate (i.e. around blood vessels, black arrows, figure 6B), whether or not they expressed Blimp-1or J-chain, as expected based on the mammalian model (figure 6). Therefore, Pax5 expression is extinguished in all shark Ig-secreting cells, and some other factor besides Blimp-1 must repress Pax5 expression in a subset of nurse shark Ig-secreting cells.

Figure 6. Pax5 expression in young and adult spleen tissue.

In situ hybridization staining of 8μm (non consecutive) sections of spleen tissue from a 1 month old (shark H) (A) or adult shark (shark W) (B). From left to right probes are specific for: IgM spanning C3-C4, J-chain, Blimp- or Pax5. Black arrows indicate regions near blood vessels where plasma cells congregate. All photographs taken at 10× magnification with 100 μm scale bar shown. Positive staining is purple. Negative controls with sense probes showed no staining (not shown).

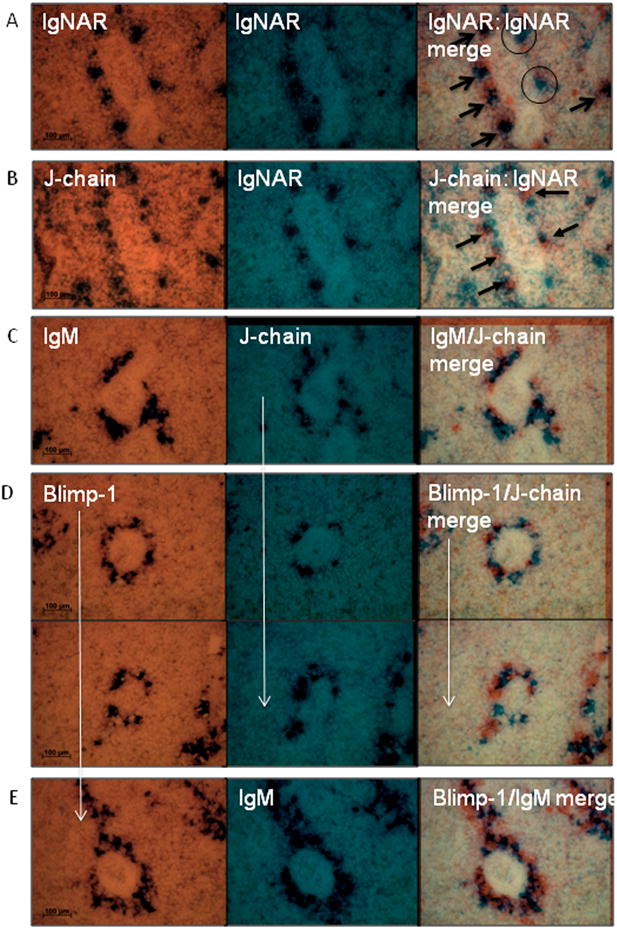

J-chain and Blimp-1 are non-coordinately expressed in adult spleen

While it was clear from the results in neonatal spleen and adult epigonal that J-chain+ Ig-secreting cells were Blimp-1- (figure 2A, 5; Table 1), staining of adult spleen was problematic because of the great number of clustered plasma cells. We attempted double-stain, in situ hybridization experiments with Blimp-1 and J-chain probes in spleen, but this also proved difficult due to the vastly different expression levels between the transcription factor and Ig/J-chain. We therefore performed single stains on consecutive, 6 μm spleen sections and “field-stitched” images from consecutive slices together to examine co-expression of IgM with J-chain, IgM with Blimp-1, and, most importantly, Blimp-1 with J-chain.

Since most plasma cells are approximately 10 μm in diameter they are large enough, in many cases, that one cell will be visible in consecutive 6 μm sections, however some cells will obviously not carry over to the next slide. In order to determine how often one cell could be detected in consecutive sections, we performed control stains using the same probe on successive slices. For these controls, we used probes specific for the previously mentioned IgNAR isotype that is expressed in ∼90% fewer splenic plasma cells than IgM, allowing detection of non-clustered IgNAR+ cells.

Because both consecutive sections were photographed in bright field, they were pseudocolored; one image in orange and the other in blue, which allowed us to distinguish the images once they were overlaid. Because the pseudocolor affected only the white space in the photos, any cell that was positive in image 1 (orange) but negative in image 2 (blue) appeared blue in the overlay. Conversely, any cell that was negative in image 1 and positive in image 2 appeared orange. Tissue sections with no positive cells were neutral-colored in the merge and, most importantly, cells that were positive in both remained black. When the IgNAR-specific probes were used on consecutive sections, five cells were found in a representative field of view that were IgNAR+ in both sections and appeared black in the merged image (figure 7A, black arrows), whereas only two cells were found in the first but not second image, and appear blue in the merge (figure 7A, black circles). Therefore the majority (5 out of 7) of IgNAR+ cells detected in one tissue section was also found in the following section, giving us confidence in the ability to use this procedure with other probes.

Figure 7. In situ hybridization for co-expression using consecutive spleen tissue sections.

In situ hybridization of consecutive 6 μm sections of sections of adult spleen tissue (shark W). Consecutive sections were stained with the probes indicated and the two images pseudocolored and field stitched together (right column). Probe pairs were IgNAR:IgNAR (A), J-chain:IgNAR (B), IgM:J-chain (C), Blimp-1:J-chain (D) and Blimp-1:IgM (E).Vertical white arrows indicate same probe used as photo above. Presence of black stain in the merge (far right) column indicates coexpression. Arrows in (A) indicate cells expressing IgNAR in both fields. Circles in (A) indicate IgNAR+ cells only seen in one of the two fields. Arrows in (B) indicate IgNAR+/J-chain- cells (orange in merge). All images were taken at 40× magnification and 100 μm scale bar is indicated in left-hand column. Each region is representative of multiple stains.

Since IgNAR is a monomer in serum, and since no J-chain+/IgNAR+ double staining cells were found in the epigonal tissue (figure 4), we did not expect co-expression of J-chain in IgNAR plasma cells in the spleen. Furthermore, like7S IgM, IgNAR makes up an enhanced-affinity, antigen-specific response [20], so we predicted that the J-chain expression state of IgNAR+ plasma cells would be similar to the Blimp-1-7S secretors (also see Discussion). Therefore, as an additional control we examined IgNAR and J-chain expression in these consecutive sections and indeed, the majority of IgNAR-secreting cells in the spleen were J-chain-. Black arrows highlight IgNAR single-positive cells, which appear orange in the merge; whereas all blue cells in the merged image are J-chain+/IgNAR- (figure 7B).

As expected based on raw numbers of positive cells (figures 1 and 2), approximately half of the IgM-secreting cells in the spleen were J-chain+ (figure 7C) and, similarly, half of the IgM+ cells co-expressed Blimp-1 (figure 7E). However, very few cells co-expressed J-chain and Blimp-1 together, as evidenced by the lower number of black cells in the Blimp-1/J-chain merge when compared to IgM/J-chain (figure 7C) or IgM/Blimp-1 (figure 7E). Therefore, the J-chain and Blimp-1 expression patterns in the adult spleen are consistent with our observations in the neonatal shark: J-chain+ cells are predominantly Blimp-1- and vice versa (table 1).

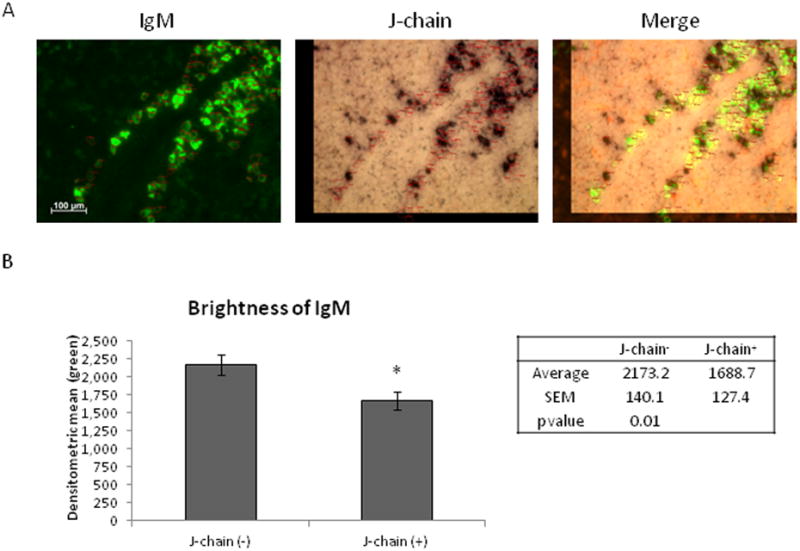

J-chain+, Blimp-1- cells express lower levels of IgM

Since Blimp-1 is traditionally believed to regulate high levels of IgM secretion, and since the J-chain+ cells were found to be Blimp-1-, it is possible that, without Blimp-1, these cells may secrete lower amounts of IgM than the Blimp-1+ cells; similar to what has been suggested for mammalian B1 cells [71, 78]. Additionally, the ELISPOT spot size of Blimp-1- IgM1gj secreting cells was noticeably smaller, than other cell types, suggesting that they may be secreting low levels of protein. If true, the J-chain+/Blimp-1- 19S cells may also have fewer IgM transcripts than the Blimp-1+ 7S cells.

When the IgM mRNA signal in plasma cells was visualized with a fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody instead of our standard chromogenic in situ hybridization method (figures 1, 2, 6 and 7), we found variability, almost a dichotomy, in the IgM signal intensity in secreting cells (figure 8A). To determine whether the J-chain+ cells were, in fact, staining less intensely for IgM, we performed in situ hybridization double-stains using a DIG-labeled IgM probe, detected fluorescently, and followed by chromogenic detection of a FLU-labeled J-chain probe. We found that the J-chain+ cells did indeed have a lower IgM signal than many J-chain- cells (figure 8A). However it should be noted that the level of IgM transcript in these IgMlow secreting cells is still much higher than that seen in non-secreting B cells found in the white pulp (figure 1).

Figure 8. Variable strength of IgM signal in J-chain positive and negative spleen cells.

In situ hybridization double stain of 6 μm sections spleen tissue from an adult shark (shark W). (A) Slides were double stained with IgM-C3-C4-DIG (left) and J-chain-FLU (middle) riboprobes. Images merged at right. Photographs taken at 40× magnification and marked with a 100 μm scale bar. (B) Data from 50 cells each of J-chain+ and J-chain- cells (from multiple fields of view) were pooled to get an average mean fluorescent intensity of the IgM stain (green). (*) indicates p-value of less than 0.05 (T-test). Error bars signify SEM.

In order to quantify the level of IgM signal in the splenic secretory cells, the mean brightness of IgM stain was analyzed in J-chain+ and J-chain- cells. All J-chain+ cells and any brightly staining IgM cells that were J-chain- were included in this analysis. J-chain-/IgMlow cells were excluded from this analysis since we could not be certain whether they were staining dimly because they actually expressed lower amounts of IgM mRNA, or because during sectioning the cell was sliced at its edge, resulting in a deceptively low signal. The average brightness of J-chain+ and J-chain- cells was measured using the densitometric mean of the green (IgM) signal for each selected cell. Based on this analysis, the majority of the brightest IgM+ cells were J-chain-, while none of the very bright cells co-expressed J-chain; conversely, J-chain+ cells were almost universally IgM-dim (figure 8B). J-chain- cells had an average densitometric mean of 2173.2 +/- 140.1, whereas J-chain+ cells were dimmer, at 1688.7 +/- 127.4 (p value = 0.01). In summary, the J-chain+/Blimp-1- 19S-secreting cells express lower levels of secreted IgM transcript than the J-chain-/Blimp-1+ 7S-secretors.

Discussion

We have found a population of Ig-secreting, J-chain+ cells present in both adult and young nurse sharks that do not express Blimp-1.Therefore, unlike conventional mammalian plasma cells, neither the antibody secretion functions nor the expression of J-chain are under the control of this master transcription factor in sharks. Thus, in sharks Blimp-1 seems to be more important for terminal differentiation and cell cycle arrest than for Ig secretion and J-chain expression. However, Blimp-1-/J-chain+ cells do express lower amounts of IgM transcript than Blimp-1+/J-chain- cells, and ELISPOTs from IgM1gj-secreting cells are smaller than those of conventional Ig, suggesting that the 19S- and gM1gj-secreting cells produce somewhat lower levels of secreted IgM protein than 7S-secretors, consistent with some recent models in mammals [9, 71, 78].

The secreted high-avidity, 19S IgM is known to be cross-reactive and it may be beneficial for the shark to have a large proportion of cells that can be easily induced to secrete such “innate-like” Ig, even if it is not produced at the same high levels as “adaptive” Ig. This may be especially important for the nurse shark, since the 7S and IgNAR responses, while comprising the typical antigen-specific response, take some time to reach peak levels [20]. Therefore, having cells that can be easily triggered to secrete natural antibodies might be of added importance as a first line of defense in an animal with such slow adaptive kinetics. These 19S-secreting cells could either self-renew like mammalian B1 cells, or be continually derived from precursors after stimulation with commensal bacteria or other common signals.

Based on the differences in gene expression between 19S- and 7S-secreting cells, we hypothesize that the transcriptional expression profile of these cells may be related to how the cells arise during B cell development and that one of two models may be true: either 19S and 7S producers develop from separate lineages, like B1 and B2 cells in mammals (model 1 below), or plasma cells go through a 19S-secreting plasmablast state before “switching” to become 7S producers by shutting down J-chain expression (model 2 below). Of course, the actual situation may be more complicated than either of these models and could even be a mixture of the two.

Model 1: 19S secreting cells as a B1-like lineage

In adult spleen, J-chain+, 19S IgM-secreting cells do not express Blimp-1, whereas J-chain-, 7S-secreting cells express high levels of Blimp-1. The 7S, Blimp-1+ cells may encompass a population of conventional, B2-like cells, which, after undergoing traditional antigen-specific expansion and hypermutation, would require Blimp-1 to extinguish these processes. The 19S-secreting cells, however, may come from a B1-like lineage. Certainly, the presence of 19S IgM-secreting cells early in development is similar to the early appearance of B1 cells in mammals. Additionally, as mentioned above, there are reports that mammalian B1 cells do not require Blimp-1 for antibody secretion [72]. Indeed, if 19S secreting cells continually divide throughout life, it may be a requirement that these cells do not express Blimp-1, since terminally differentiated Blimp-1+ cells would be unable to self renew. In this model, the 19S-secreting cells, like IgM1gj-secreting cells, may persist long term in the adult epigonal organ (table 1 and discussed further below).

Model 2: 19S secreting cells as a developmental stage

Alternatively, the 19S-secretors may constitute a plasmablast-like developmental stage, as has also been suggested in mammalian B1 cell models [9, 71]. It has been shown that Blimp-1 is not expressed in mouse pre-plasmablasts, even-though Pax5 is already down-regulated at this stage [70]. Nurse shark 19S-secreting cells could therefore represent a similar transitional state between B cells and the end-stage 7S-secreting plasma cells. In this model, during an antigen-driven immune response, J-chain expression would eventually be extinguished, allowing 19S-secreting cells to “functionally class switch” to a 7S-IgM secreting cell type, coinciding with high levels of Blimp-1 and IgM expression, characteristic of true plasma cells. If model 2 is correct, this transitional stage appears to be more pronounced and longer-lasting in the nurse shark than in mammals, since 19S-secreting J-chain+ cells make up a major proportion of adult spleen cells regardless of immunization status.

Regardless of whether J-chain+/Blimp-1- 19S cells represent a separate lineage or developmental state, additional transcription factors must be required to play a role in controlling Pax5, Blimp-1, and J-chain expression. Although it is currently unclear what these factor(s) could be, identification of such elements will be important for clarifying whether these cells truly come from distinct lineages or if 19S cells somehow ‘mature’ into 7S secretors (as in model 2). If model 1 is true, we hypothesize that shark B cells are clonally marked from their earliest stages for J-chain expression, and perhaps committed to separate lineages early, as suggested for mouse B cells by Leanderson [30].

Long-term survival in the primary lymphoid organ

We have also found a population of Ig-secreting cells in the epigonal organ that is J-chain- and Blimp-1- (figure 3), thus differing in Blimp-1 expression status from the J-chain- cells in the spleen (table 1). This apparent contradiction may be explained by the proposed nature of cells in the epigonal; like mammalian bone marrow, the epigonal organ likely contains a subset of long-lived plasma cells that persist throughout life. For example, the IgM1gj-secreting cells that develop early in life do not express Blimp-1, and persist only in the epigonal tissue of adult sharks ([21] and table 1). Perhaps, not just IgM1gj but all epigonal-resident plasma cells continue to slowly divide throughout the life of the animal. In this scenario IgW+/J-chain+ cells would make up one lineage (with unknown function), while IgM+/J-chain- cells may be a second long-lived, antigen-specific lineage that continue to persist in the epigonal after B cell activation in the spleen. In either case, the epigonal appears to be an organ in which Blimp-1- plasma cells of various types survive and are capable of long-term self-renewal.

Future studies in shark

The ability to separate 19S- from 7S-secreting cells would greatly aid future characterization of these cell types, and identification of the factors controlling J-chain expression. Additionally, by separating 19S and 7S cells we would be able to analyze the IgM repertoires, including CDR3 length and N-region additions. If the two forms do originate from different cell lineages, we would predict observation of signature differences between the two, with the 19S IgM repertoire perhaps being less diverse, as has been described for natural antibodies in mammals [79]. Shark 7S, but not 19S IgM shows augmented affinity to antigen after immunization [20], so it would also be interesting to follow mutations in the IgM-secreting cells throughout the course of an immune response. We would predict that only 7S-secretors would contain mutations, but by following an antigen-specific response it may be possible to identify antigen-specific 19S cells found early in a response, and to compare these to 7S secreting cells arising later. If IgM secreting cells switch as per model 2, we would likely find unmutated and mutated sequences from the same antigen-specific BCR within the 19S and 7S populations, respectively.

Relevance of shark Blimp-1 and J-chain expression to mammalian and other vertebrate systems

We predict that this dichotomy of J-chain and Blimp-1 expression is not a shark-specific phenomenon. Unlike monomeric Ig H chain classes in mammals, such as IgG, where the expression of J-chain has no effect on the structure of the secreted isotypes, in sharks, regulation of J-chain expression is important because 7S IgM is secreted only in the absence of J-chain. Even in mammalian systems, it is known that J-chain is only expressed in a subset of plasma cells. For example, some IgA-secreting cells in the mouse are J-chain- and secrete IgA monomers. Therefore, transcriptional control of J-chain is likely to be as important in at least a subset of mammalian plasma cells as it is in sharks, and in many mammalian systems the importance of J-chain may have simply fallen under the radar since it does not associate with IgG.

It has been documented that J-chain+ IgA-secreting cells of the mammalian lamina propria are derived from B1 cells, whereas B2 cells secrete J-chain- IgA [80]. We therefore predict, based on our results in nurse shark, that the J-chain+ (B1-derived, IgA+) cells may be Blimp-1 negative, whereas the J-chain- (B2-derived, IgA+) plasma cells would express Blimp-1. From a broader evolutionary perspective, similar predictions can also be made for other non-mammalian vertebrate models. Both teleosts and Xenopus have dedicated mucosal Ig classes (IgT and IgX respectively) [81-83], and these mucosal Ig-secreting cells may contain B1-derrived secreting cells, similar to mammalian J-chain+, IgA secretors. Although it is important to note that while the teleosts genome has lost J-chain, mucosal Ig secreting cells may lack Blimp-1, similar to shark 19S secretors, and in Xenopus, mucosal IgX+ cells may be J-chain+/Blimp-1-.

Conclusions

While results with Blimp-1 expression in plasma cells have been controversial in mammalian systems, here we describe naturally occurring antibody secreting cells, found in multiple lymphoid tissues in both young and adult nurse sharks, which do not express Blimp-1. Additionally, we found that J-chain+, 19S IgM-secreting cells are Blimp-1-, while Blimp-1 is expressed normally in 7S secretors. Although IgM transcripts are expressed at lower levels in the J-chain+ cells, these cells nevertheless secrete detectable 19S IgM in the absence of Blimp-1. Our observation, that Blimp-1 is not expressed in all antibody-secreting shark cells, supports the non-canonical model of Blimp-1 expression in the Ig secretion program of mammalian B1 cells. Thus, our results not only make inroads to the age-old problem of the production of 19S and 7S IgM in secretory B cells in sharks, but also have implications for the role of Blimp-1 in Ig secretion in B cell lineages in all vertebrates.

Methods

Animals, tissue collection and cell preparations

Nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) were captured off the coast of the Florida Keys and maintained in artificial seawater at approximately 28°C in large indoor tanks at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology, in Baltimore, MD. As per animal protocol (IACUC 1012003) animals were euthanized and bled out after an overdose of MS222. Spleen and epigonal tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in SBP. Tissue was then washed in sucrose gradient solutions over 24 hours before mounting in OCT and freezing in a methyl butane bath cooled with liquid nitrogen. Once frozen, tissue was cut into either 6 or 8 μm sections using a Leica Cryostat and mounted on slides. Cut tissue was kept at -80°C until ready to use for in situ hybridization. Frozen, fixed tissue used came from 6 sharks of various ages. Shark TH and H were approximately 1 week old. Shark LA was 1-3 months old, and LJ, EL, and W were all adults over 1 year of age.

For immunoprecipitation and ELISPOT studies, shark cells were collected from dissociated spleen or epigonal tissue or from blood and washed in “shark PBS plus” (PBS supplemented with 0.35 M urea, 0.14 M extra NaCl, 10% FCS and DNase). Plasma cells were enriched by fractionating over a 1.054 density percoll gradient, and washed again in shark PBS plus before either radiolabeling or resuspending in RPMI with 10% FCS, 0.35M urea, and 0.14 M extra NaCl, for overnight culture at 27 C. Cells came from 3 sharks of various ages: shark R is 6 months in age, EN was approximately 1 year old, and B is an adult shark of at least 9 years.

In situ hybridization

Digoxigenin (DIG) - or Fluorescein (FLU)-labeled Riboprobes were made with the following primers: IgM1gj, IgM C2, IgM C3-C4, J-chain, IgL Kappa, Blimp-1 or Pax5. For regular in situ hybridization, DIG-labeled probes were detected with anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase (AP) and nitro-blue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyphosphate (NBT/BCIP) substrate. Experiments including transcription factors were developed using Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Plus Biotin or DNP System (Perkin Elmer) with either Streptavidin-AP or anti-DNP-AP and NBT/BCIP substrate. For in situ hybridization staining of consecutive 6 μm sections, probes were detected with TSA Plus Biotin System (Perkin Elmer) with Streptavidin-AP and NBT/BCIP substrate. The slides were photographed and the images field-stitched together using Zeiss's AxioVision software, version 4.8.2.0.For double stains, DIG- and FLU-labeled probes were hybridized together, and the fluorescent signal (DIG-labeled probe) was detected first using anti-Digoxigenin rabbit olioglonal (Invitrogen) primary antibody and AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary. The slides were photographed before completing chromogenic detection of the FLU-labeled probe using PerkinElmer's TSA Plus Biotin System with Streptavidin-AP and NBT/BCIP substrate. Slides were then re-photographed and images aligned using the previously mentioned software.

Blimp-1 Cloning

Primers were designed to amplify the zinc finger-rich region of Xenopus laevis Blimp-1 (Genbank accession AF182280, xBlimpF1: 5′-CTGGTTATAAGACTCTCC-3′, xBlimpR1: 5′-GCACAGGATGTAGCTC-3′) from X. laevis spleen RNA. The 428 bp product was labeled and used to probe a nurse shark cDNA library, as previously described [75, 76, 84].Two identical Blimp-1 clones were sequenced that were both truncated at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The full-length sequence was obtained using Clontech's SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit(Clontech) using gene specific primer (GSP):5′ RACE used GcBlimpRR1 (5′-CTTCGAGGCAGGTCAATGCACTTTAGC-3′) for first round PCR with the kit-supplied universal primer, followed by the second PCR with the nested GSP GcBlimpRR2 (5′-CTGCAAACTCGCTGCTGTACCAGAC-3′) with the kit-supplied universal primer.3′ RACE was performed by using GcBlimpRF1 (5′-CAACCTAAACCTACCTCAGCTGGCTTG-3′) for first round PCRs with the kit-supplied universal primer and GcBlimpRF2 (5′-CAAGGTCCATTTGAGAGTCCATAGTGGG-3′) for nested second round PCR with the kit-supplied universal primer. In order to complete the sequence 3′ RACE was repeated using the primers GcBlimpRF5 (5′-CCTCAAAGGAAACTGCCCCGTCGCC-3′) for first round PCR and GcBlimpRF6 (5′-GACCTGAACCGCCTGAACGAGG-3′) for nested second round PCR (with kit-supplied primers as above).The full-length sequence was confirmed using the primers GcBlimpFullF1 (5′- GTGGATGAAAATGGACATGACCC-3′) and GcBlimpFullR1 (5′-AGGTCAGAGACACGTTGCATCTC-3′).

Blimp-1 tree

The V domains of the deduced amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX, and neighbor-joining bootstrapping trees (500 trials) [85] were made and viewed in the TreeView 1.6.6. program [86].

ELISPOTs

96 well plates (Millipore MultiScreen HA plates #MAHAS4510) were coated with 100 μl/well mAbs (CB5, TG4 or LK14) at 10 μg/ml, and incubated overnight at 4 C to coat. The following day the plates were washed 5× with 100 ul/well sterile PBS then blocked with 200 μl/well DMEM with 10% serum for 2-3 hours at 37 C. Plates were washed again 5× with 100 μl/well sterile PBS before plating cells in shark RPMI and incubating overnight at 27 C in humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The following day cells were washed away with 3× PBS washes followed by 3× PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween) of 200 ul/well, with 1-minute incubations between washes. 100 μl/well of biotinylated detection antibodies (LK14-biotin, GA16-biotin or TG4-biotin) were added at 5 μg/ml in PBST with 1% FCS and plates were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. 3× PBS and 3× PBST washes were repeated and plates were incubated with 100 μl/well streptavidin- alkaline phosphatase (AP) secondary at 1:2000 in PBST with 1% FCS for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were washed again 5× with PBS and AP signal was detected with 100 μl/well NBT/BCIP diluted in 0.1 M Tris pH 9.5, 0.1 M NaCl buffer. Plates were washed in water to stop development reaction and left to dry before reading and analyzing spots using CTL Immunospot capture software v 6.3.5 and analysis software v 5.0. Significance was determined using an independent two-tailed student's t-test.

Immunoprecipitations

Nurse shark cells were incubated in RPMI minus MET for 30 min at 27 C followed by addition of 1 μCi S35 to cells and incubation at 27 C overnight. Supernatant was collected the following day. Supernatants were precleared with protein G sepharose beads (Amersham #17-0618-01) (100 μl beads/500 μl supernatant) for 1 hour at room temperature, before incubating with mAbs (2 μl purified CB5, TG4 or GA10) overnight at 4 C, while rotating [21]. The following day supernatants were incubated with 30 μl of protein G beads each for 1 hour at 4 C with rotation. Beads were washed 2× with NET-NON and 1× with NET-N, before boiling in 30 μl Laemmli Sample Buffer (LSB) and loading (non-reduced) on a 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-acylamide gel. After running gels were fixed for 1 hour and incubated 2× with Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at room temperature for 30 min while shaking. Gels were then washed with DMSO-PPO (2,5 dipheynl oxazole) overnight followed by washing with water and dehydration before 1-week film exposure and development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Rezwanul Wahid and Harold Neely for their generous help with ELISPOTs and antibody purifications. This work was funded by NIH RR006603.Caitlin Castro was a trainee under the Institutional Training Grant T32AI007540 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Institutional Training Grant in Cardiac and Vascular Cell Biology #5 T32 HL072751 from the NIH/NHLBI while this work was completed.

Abbreviations

- TM

Transmembrane

- C2

Ig heavy chain constant domain 2

- Blimp-1

B-lymphocyte-induced maturation protein 1

- 19S

pentameric IgM

- 7S

monomeric IgM

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:812–818. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alugupalli KR, Leong JM, Woodland RT, Muramatsu M, Honjo T, Gerstein RM. B1b lymphocytes confer T cell-independent long-lasting immunity. Immunity. 2004;21:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurnheer MC, Zuercher AW, Cebra JJ, Bos NA. B1 cells contribute to serum IgM, but not to intestinal IgA, production in gnotobiotic ig allotype chimeric mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:4564–4571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgarth N, Tung JW, Herzenberg LA. Inherent specificities in natural antibodies: A key to immune defense against pathogen invasion. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;26:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy RR. B-1 B cell development. J Immunol. 2006;177:2749–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton AM, Lehuen A, Kearney JF. Immunofluorescence analysis of B-1 cell ontogeny in the mouse. Int Immunol. 1994;6:355–361. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgarth N. The double life of a B-1 cell: Self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:34–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2901. 10.1038/nri2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgarth N, Herman OC, Jager GC, Brown L, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Innate and acquired humoral immunities to influenza virus are mediated by distinct arms of the immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2250–2255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi YS, Dieter JA, Rothaeusler K, Luo Z, Baumgarth N. B-1 cells in the bone marrow are a significant source of natural IgM. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:120–129. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141890. 10.1002/eji.201141890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berek C, Berger A, Apel M. Maturation of the immune response in germinal centers. Cell. 1991;67:1121–1129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90289-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacob J, Kelsoe G, Rajewsky K, Weiss U. Intraclonal generation of antibody mutants in germinal centres. Nature. 1991;354:389–392. doi: 10.1038/354389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flajnik MF. Comparative analyses of immunoglobulin genes: Surprises and portents. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokubu F, Litman R, Shamblott MJ, Hinds K, Litman GW. Diverse organization of immunoglobulin VH gene loci in a primitive vertebrate. EMBO J. 1988;7:3413–3422. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clem IW, De Boutaud F, Sigel MM. Phylogeny of immunoglobulin structure and function. II. immunoglobulins of the nurse shark. J Immunol. 1967;99:1226–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clem LW, Small PA., Jr Phylogeny of immunoglobulin structure and function. V. valences and association constants of teleost antibodies to a haptenic determinant. J Exp Med. 1970;132:385–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frommel D, Litman GW, Finstad J, Good RA. The evolution of the immune response. XI. the immunoglobulins of the horned shark, heterodontus francisci: Purification, characterization and structural requirement for antibody activity. J Immunol. 1971;106:1234–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchalonis J, Edelman GM. Phylogenetic origins of antibody structure. I. multichain structure of immunoglobulins in the smooth dogfish (mustelus canis) J Exp Med. 1965;122:601–618. doi: 10.1084/jem.122.3.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchalonis J, Edelman GM. Polypeptide chains of immunoglobulins from the smooth dogfish (mustelus canis) Science. 1966;154:1567–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3756.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voss EW, Jr, Rudikoff S, Sigel MM. Comparative ligand-binding by purified nurse shark natural antibodies and anti-2,4-dinitrophenyl antibodies from other species. J Immunol. 1971;107:12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dooley H, Flajnik MF. Shark immunity bites back: Affinity maturation and memory response in the nurse shark, ginglymostoma cirratum. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:936–945. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rumfelt LL, Avila D, Diaz M, Bartl S, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. A shark antibody heavy chain encoded by a nonsomatically rearranged VDJ is preferentially expressed in early development and is convergent with mammalian IgG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1775–1780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenberg AS, Hughes AL, Guo J, Avila D, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. A novel “chimeric” antibody class in cartilaginous fish: IgM may not be the primordial immunoglobulin. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1123–1129. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berstein RM, Schluter SF, Shen S, Marchalonis JJ. A new high molecular weight immunoglobulin class from the carcharhine shark: Implications for the properties of the primordial immunoglobulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3289–3293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ota T, Rast JP, Litman GW, Amemiya CT. Lineage-restricted retention of a primitive immunoglobulin heavy chain isotype within the dipnoi reveals an evolutionary paradox. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2501–2506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538029100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg AS, Avila D, Hughes M, Hughes A, McKinney EC, Flajnik MF. A new antigen receptor gene family that undergoes rearrangement and extensive somatic diversification in sharks. Nature. 1995;374:168–173. doi: 10.1038/374168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fidler JE, Clem LW, Small PA., Jr Immunoglobulin synthesis in neonatal nurse sharks (ginglymostoma cirratum) Comp Biochem Physiol. 1969;31:365–371. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(69)91660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohman VS, Stewart SE, Rumfelt LL, Greenberg AS, Avila DW, Flajnik MF, Steiner LA. J chain in the nurse shark: Implications for function in a lower vertebrate. J Immunol. 2003;170:6016–6023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mestecky J, Zikan J, Butler WT. Immunoglobulin M and secretory immunoglobulin A: Presence of a common polypeptide chain different from light chains. Science. 1971;171:1163–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3976.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erlandsson L, Andersson K, Sigvardsson M, Lycke N, Leanderson T. Mice with an inactivated joining chain locus have perturbed IgM secretion. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2355–2365. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2355::AID-IMMU2355>3.0.CO;2-L. 2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erlandsson L, Akerblad P, Vingsbo-Lundberg C, Kallberg E, Lycke N, Leanderson T. Joining chain-expressing and -nonexpressing B cell populations in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2001;194:557–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansen FE, Braathen R, Brandtzaeg P. Role of J chain in secretory immunoglobulin formation. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:240–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klimovich VB, Samoilovich MP, Klimovich BV. Problem of J-chain of immunoglobulins. Zh Evol Biokhim Fiziol. 2008;44:131–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansen FE, Natvig Norderhaug I, Roe M, Sandlie I, Brandtzaeg P. Recombinant expression of polymeric IgA: Incorporation of J chain and secretory component of human origin. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1701–1708. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199905)29:05<1701::AID-IMMU1701>3.0.CO;2-Z. 2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerutti A, Rescigno M. The biology of intestinal immunoglobulin A responses. Immunity. 2008;28:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandtzaeg P, Prydz H. Direct evidence for an integrated function of J chain and secretory component in epithelial transport of immunoglobulins. Nature. 1984;311:71–73. doi: 10.1038/311071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner CA, Jr, Mack DH, Davis MM. Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell. 1994;77:297–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fumasoni I, Meani N, Rambaldi D, Scafetta G, Alcalay M, Ciccarelli FD. Family expansion and gene rearrangements contributed to the functional specialization of PRDM genes in vertebrates. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenuwein T. Re-SET-ting heterochromatin by histone methyltransferases. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:266–273. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim KC, Geng L, Huang S. Inactivation of a histone methyltransferase by mutations in human cancers. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7619–7623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayashi K, Yoshida K, Matsui Y. A histone H3 methyltransferase controls epigenetic events required for meiotic prophase. Nature. 2005;438:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nature04112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ancelin K, Lange UC, Hajkova P, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T, Surani MA. Blimp1 associates with Prmt5 and directs histone arginine methylation in mouse germ cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:623–630. doi: 10.1038/ncb1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su ST, Ying HY, Chiu YK, Lin FR, Chen MY, Lin KI. Involvement of histone demethylase LSD1 in blimp-1-mediated gene repression during plasma cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1421–1431. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01158-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin KI, Angelin-Duclos C, Kuo TC, Calame K. Blimp-1-dependent repression of pax-5 is required for differentiation of B cells to immunoglobulin M-secreting plasma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4771–4780. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4771-4780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shaffer AL, Lin KI, Kuo TC, Yu X, Hurt EM, Rosenwald A, Giltnane JM, Yang L, Zhao H, Calame K, Staudt LM. Blimp-1 orchestrates plasma cell differentiation by extinguishing the mature B cell gene expression program. Immunity. 2002;17:51–62. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin Y, Wong K, Calame K. Repression of c-myc transcription by blimp-1, an inducer of terminal B cell differentiation. Science. 1997;276:596–599. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angelin-Duclos C, Cattoretti G, Lin KI, Calame K. Commitment of B lymphocytes to a plasma cell fate is associated with blimp-1 expression in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:5462–5471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh M, Birshtein BK. NF-HB (BSAP) is a repressor of the murine immunoglobulin heavy-chain 3′ alpha enhancer at early stages of B-cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3611–3622. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rinkenberger JL, Wallin JJ, Johnson KW, Koshland ME. An interleukin-2 signal relieves BSAP (Pax5)-mediated repression of the immunoglobulin J chain gene. Immunity. 1996;5:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaffer AL, Peng A, Schlissel MS. In vivo occupancy of the kappa light chain enhancers in primary pro- and pre-B cells: A model for kappa locus activation. Immunity. 1997;6:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shapiro-Shelef M, Calame K. Regulation of plasma-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:230–242. doi: 10.1038/nri1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shapiro-Shelef M, Lin KI, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Liao J, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Calame K. Blimp-1 is required for the formation of immunoglobulin secreting plasma cells and pre-plasma memory B cells. Immunity. 2003;19:607–620. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida T, Mei H, Dorner T, Hiepe F, Radbruch A, Fillatreau S, Hoyer BF. Memory B and memory plasma cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:117–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cobaleda C, Schebesta A, Delogu A, Busslinger M. Pax5: The guardian of B cell identity and function. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:463–470. doi: 10.1038/ni1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reimold AM, Ponath PD, Li YS, Hardy RR, David CS, Strominger JL, Glimcher LH. Transcription factor B cell lineage-specific activator protein regulates the gene for human X-box binding protein 1. J Exp Med. 1996;183:393–401. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vincent SD, Dunn NR, Sciammas R, Shapiro-Shalef M, Davis MM, Calame K, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ. The zinc finger transcriptional repressor Blimp1/Prdm1 is dispensable for early axis formation but is required for specification of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Development. 2005;132:1315–1325. doi: 10.1242/dev.01711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ohinata Y, Payer B, O'Carroll D, Ancelin K, Ono Y, Sano M, Barton SC, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A, et al. Blimp1 is a critical determinant of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nature. 2005;436:207–213. doi: 10.1038/nature03813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chan YH, Chiang MF, Tsai YC, Su ST, Chen MH, Hou MS, Lin KI. Absence of the transcriptional repressor blimp-1 in hematopoietic lineages reveals its role in dendritic cell homeostatic development and function. J Immunol. 2009;183:7039–7046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Hayashi M, Fukunaga T, Kato S, Kodama T, Takahashi S, Calame K, Takayanagi H. Blimp1-mediated repression of negative regulators is required for osteoclast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3117–3122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912779107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyauchi Y, Ninomiya K, Miyamoto H, Sakamoto A, Iwasaki R, Hoshi H, Miyamoto K, Hao W, Yoshida S, Morioka H, et al. The Blimp1-Bcl6 axis is critical to regulate osteoclast differentiation and bone homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:751–762. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang DH, Angelin-Duclos C, Calame K. BLIMP-1: Trigger for differentiation of myeloid lineage. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:169–176. doi: 10.1038/77861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martins GA, Cimmino L, Shapiro-Shelef M, Szabolcs M, Herron A, Magnusdottir E, Calame K. Transcriptional repressor blimp-1 regulates T cell homeostasis and function. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:457–465. doi: 10.1038/ni1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kallies A, Hawkins ED, Belz GT, Metcalf D, Hommel M, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Nutt SL. Transcriptional repressor blimp-1 is essential for T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:466–474. doi: 10.1038/ni1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Intlekofer AM, Kao C, Angelosanto JM, Reiner SL, Wherry EJ. A role for the transcriptional repressor blimp-1 in CD8(+) T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2009;31:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rutishauser RL, Martins GA, Kalachikov S, Chandele A, Parish IA, Meffre E, Jacob J, Calame K, Kaech SM. Transcriptional repressor blimp-1 promotes CD8(+) T cell terminal differentiation and represses the acquisition of central memory T cell properties. Immunity. 2009;31:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kallies A, Xin A, Belz GT, Nutt SL. Blimp-1 transcription factor is required for the differentiation of effector CD8(+) T cells and memory responses. Immunity. 2009;31:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xin A, Nutt SL, Belz GT, Kallies A. Blimp1: Driving terminal differentiation to a T. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;780:85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5632-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kallies A, Carotta S, Huntington ND, Bernard NJ, Tarlinton DM, Smyth MJ, Nutt SL. A role for Blimp1 in the transcriptional network controlling natural killer cell maturation. Blood. 2011;117:1869–1879. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zwollo P. Dissecting teleost B cell differentiation using transcription factors. Dev Comp Immunol. 2011;35:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.01.009. 10.1016/j.dci.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Savitsky D, Calame K. B-1 B lymphocytes require blimp-1 for immunoglobulin secretion. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2305–2314. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kallies A, Hasbold J, Fairfax K, Pridans C, Emslie D, McKenzie BS, Lew AM, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM, Nutt SL. Initiation of plasma-cell differentiation is independent of the transcription factor blimp-1. Immunity. 2007;26:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fairfax KA, Corcoran LM, Pridans C, Huntington ND, Kallies A, Nutt SL, Tarlinton DM. Different kinetics of blimp-1 induction in B cell subsets revealed by reporter gene. J Immunol. 2007;178:4104–4111. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tumang JR, Frances R, Yeo SG, Rothstein TL. Spontaneously ig-secreting B-1 cells violate the accepted paradigm for expression of differentiation-associated transcription factors. J Immunol. 2005;174:3173–3177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rumfelt LL. Studies of immunoglobulin expression and lymphoid tissue development during ontogeny in the nurse shark. Ginglymostoma cirratum. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rumfelt LL, McKinney EC, Taylor E, Flajnik MF. The development of primary and secondary lymphoid tissues in the nurse shark ginglymostoma cirratum: B-cell zones precede dendritic cell immigration and T-cell zone formation during ontogeny of the spleen. Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:130–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Criscitiello MF, Saltis M, Flajnik MF. An evolutionarily mobile antigen receptor variable region gene: Doubly rearranging NAR-TcR genes in sharks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5036–5041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507074103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Criscitiello MF. Shark class II invariant chain reveals ancient conserved relationships with cathepsins and MHC class II. Developmental Comparative Immunology. 2012;36:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nutt SL, Eberhard D, Horcher M, Rolink AG, Busslinger M. Pax5 determines the identity of B cells from the beginning to the end of B-lymphopoiesis. Int Rev Immunol. 2001;20:65–82. doi: 10.3109/08830180109056723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McIntyre TM, Holmes KL, Steinberg AD, Kastner DL. CD5+ peritoneal B cells express high levels of membrane, but not secretory, C mu mRNA. J Immunol. 1991;146:3639–3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carlsson L, Holmberg D. Genetic basis of the neonatal antibody repertoire: Germline V-gene expression and limited N-region diversity. Int Immunol. 1990;2:639–643. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.7.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosado MM, Aranburu A, Capolunghi F, Giorda E, Cascioli S, Cenci F, Petrini S, Miller E, Leanderson T, Bottazzo GF, et al. From the fetal liver to spleen and gut: The highway to natural antibody. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:351–361. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mussmann R, Du Pasquier L, Hsu E. Is xenopus IgX an analog of IgA? Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2823–2830. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang YA, Salinas I, Li J, Parra D, Bjork S, Xu Z, LaPatra SE, Bartholomew J, Sunyer JO. IgT, a primitive immunoglobulin class specialized in mucosal immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:827–835. doi: 10.1038/ni.1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Flajnik MF. All GOD's creatures got dedicated mucosal immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:777–779. doi: 10.1038/ni0910-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bartl S, Miracle AL, Rumfelt LL, Kepler TB, Mochon E, Litman GW, Flajnik MF. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferases from elasmobranchs reveal structural conservation within vertebrates. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:594–604. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0608-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Page RD. TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.