Abstract

While inhibition of class I/IIb histone deacetylases (HDACs) protects the mammalian heart from ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury, class selective effects remain unexamined. We hypothesized that selective inhibition of class I HDACs would preserve left ventricular contractile function following IR in isolated hearts. Male Sprague Dawley rats (n=6 per group) were injected with vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide, 0.63 mg/kg), the class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (1 mg/kg), the class I HDAC inhibitor entinostat (MS-275, 10 mg/kg), or the HDAC6 (class IIb) inhibitor tubastatin A (10 mg/kg). After 24 h, hearts were isolated and perfused in Langendorff mode for 30 min (Sham) or subjected to 30 min global ischemia and 120 min global reperfusion (IR). A saline filled balloon attached to a pressure transducer was placed in the LV to monitor contractile function. After perfusion, LV tissue was collected for measurements of antioxidant protein levels and infarct area. At the conclusion of IR, MS-275 pretreatment was associated with significant preservation of developed pressure, rate of pressure generation, rate of pressure relaxation and rate pressure product, as compared to vehicle treated hearts. There was significant reduction of infarct area with MS-275 pretreatment. Contractile function was not significantly restored in hearts treated with trichostatin A or tubastatin A. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and catalase protein and mRNA in hearts from animals pretreated with MS-275 were increased following IR, as compared to Sham. This was associated with a dramatic enrichment of nuclear FOXO3a transcription factor, which mediates the expression of SOD2 and catalase. Tubastatin A treatment was associated with significantly decreased catalase levels after IR. Class I HDAC inhibition elicits protection of contractile function following IR, which is associated with increased expression of endogenous antioxidant enzymes. Class I/IIb HDAC inhibition with trichostatin A or selective inhibition of HDAC6 with tubastatin A was not protective. This study highlights the need for the development of new strategies that target specific HDAC isoforms in cardiac ischemia reperfusion.

Keywords: histone deacetylase, ischemia reperfusion, catalase, superoxide dismutase, isolated heart, FOXO

1. Introduction

The ischemic heart is poorly perfused, hypoxic, and unable to generate adequate blood flow. To achieve whole organ survival, restoration of normal perfusion is mandatory. Paradoxically, reperfusion itself contributes to lethal injury at the cellular level [1]. The degree of ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury is dependent upon the severity and duration of the preceding ischemic event, and is well characterized in animal models and man [2, 3]. Oxidative stress is a predominant feature of myocardial ischemia reperfusion, and is derived partly from ischemic hypoxia and from the release of reactive oxygen species that overwhelm endogenous antioxidant systems during reperfusion [4, 5]. Strategies seeking to target the oxidative stress component of IR injury have not translated successfully to patients, and more sophisticated strategies remain under investigation [6].

One novel target for cardioprotection from oxidative stress is acetylation, which is one element of the complex language of posttranslational modification (PTM) of proteins. Lysine acetylation combines with a number of other PTMs to regulate protein function under diverse local subcellular environments [7]. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) and histone acetyltransferases control the posttranslational acetylation state of lysine residues on histones and a continually expanding record of nonhistone proteins [8]. In recognition of this latter function, HDACs are also referred to as lysine deacetylases (KDACs). HDACs are divided into classes based upon their homology to yeast transcriptional repressors and, due to differences in structure and function, can be pharmacologically inhibited in a class selective manner [9]. Class I comprises HDACs 1, 2, 3 and 8; Class IIa comprises HDACs 4, 5, 7 and 9; Class IIb comprises HDACs 6 and 10.

Importantly, global HDAC activity is increased following cardiac IR [10]. Members of class III HDACs, called sirtuins, are known to protect the heart from oxidative stress induced by IR [11]. Conversely, members of classes I and II have been linked to IR injury [8, 9]. Researchers have very recently utilized small molecule inhibitors to show that class I/II HDACs are also important regulators of cellular signaling in cardiac IR and myocardial infarction (MI). The laboratory of Zhao and Zhang et al. recently reported that isolated hearts are protected from IR injury when harvested from animals previously treated with the class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) [12, 13, 14, 15]. The same group demonstrated attenuation of remodeling in MI mice with post-ligation administration of TSA [16]. Granger et al. showed infarct reduction when TSA was administered 45 minutes after reperfusion in an in vivo model of IR in the mouse [10]. Lee et al. demonstrated attenuation of ventricular remodeling following MI in vivo when valproic acid or tributyrin were administered to rats 24 hours after ligation of the left anterior descending artery [17]. However, these short chain fatty acids are known to weakly inhibit HDAC activity with a number of off target effects [8, 9].

Though widely available, class selective HDAC inhibitors have not been applied to the IR heart. Importantly, class I HDACs are selectively inhibited by entinostat (MS-275) [9]. Inhibition of class I HDACs suppressed prohypertrophic signaling in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes [18]. In kidney cells, the endogenous HDAC inhibitor βhydroxybutyrate (βOHB) enriched the FOXO3a transcription factor by inhibiting HDAC1 catalytic activity at the Foxo3a promoter [19]. This was associated with increased expression of SOD2 and catalase, enzymes which are targets of FOXO3a and which are widely known to buffer cellular oxidative stress [20]. Notably, βOHB did not inhibit HDAC6. HDAC6 is selectively inhibited by tubastatin A (TubA), and is the only member of the HDAC family to possess two deacetylase domains [9]. In spite of being the best characterized of the class IIb HDACs, the effects of HDAC6 inhibition on the IR heart are not known.

The following report is focused on identifying the effects of selectively inhibiting class I HDACs and/or HDAC6, the class IIb HDAC, on the IR heart. Our overall hypothesis is that class I HDAC inhibition is responsible for the protection conferred to the IR heart. We also test the idea that, similar to results in the kidney, treatment with a class I HDAC inhibitor results in an upregulation of antioxidant enzymes. This study is the first to examine the effects of targeting HDAC classes individually for protection from cardiac injury. Our hope is that this work will lead to a fuller understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for the protection conferred by HDAC inhibitors to the heart subjected to ischemia reperfusion.

2. Methods

2.1. Isolated heart preparation

Male Sprague Dawley rats (250 to 300 g) purchased from Harlan (Frederick, MD) were cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Medical University of South Carolina. Intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (85/15 mg/kg) was used for anesthetic. Tracheotomy was performed with a 16 g catheter attached to a rodent ventilator set to deliver 8 mL/kg per stroke of room air at 70 strokes/min. A single intrajugular injection of heparin (1,000 mg/kg) was delivered and allowed to circulate for one minute before midsternal thoracotomy was performed to expose the beating heart. In situ cannulation of the aorta proximal to the ascending arch was followed by rapid excision and transfer of the heart to a non recirculating Langendorff perfusion apparatus. Hearts were perfused with oxygenated (95% O2 + 5% CO2) modified Krebs Henseleit buffer (in mM: 112 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1 K2HPO4, 1.25 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 11 D glucose, 0.2 octanoic acid, pH = 7.4) and maintained at 75 mm Hg perfusion pressure and 37.4 °C through use of custom crafted water jacketed glassware.

2.2. Left ventricular contractile function

A left ventricular balloon attached to a pressure transducer was inserted into the left ventricle, and set to a minimum diastolic pressure of 10 mm Hg. The pressure transducer was attached to a PowerLab 8/30 analog to digital converter and associated LabChart software (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO, USA) for measurement of heart rate, maximum (systolic) and minimum (diastolic) ventricular pressures, and rate of pressure generation (dP/dtmax) and pressure relaxation (dP/dtmin). Developed pressure was calculated as the difference between maximum and minimum pressure in a single contractile cycle, and rate pressure product was calculated as developed pressure times heart rate. Coronary flow was continuously monitored by the use of an inline small animal flow meter (Model TS410, Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA).

2.3. Application of class selective histone deacetylase inhibitors in ischemia reperfusion

Rats were injected intraperitoneally 24 h and again 1 h before heart excision, with vehicle (0.63 mg/kg) or one of the following HDAC inhibitors: a) trichostatin A (TSA, 1.0 mg/kg), a class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor, b) entinostat (MS-275, 10 mg/kg), a class I inhibitor with a binding preference for HDACs 1, 2 and 3, or c) tubastatin A (TubA, 10 mg/kg), the HDAC6 selective inhibitor [8, 9]. Hearts were perfused with buffer for 15 min before induction of global ischemia through complete cessation of perfusion for 30 min. Reperfusion was then induced for 120 min through restoration of normal perfusion with oxygenated buffer at 75 mm Hg perfusion pressure.

2.4. Infarct Size

Following IR, hearts were stained and infarct size was quantified using the method of Ferrera et al. [21]. Briefly, hearts were frozen at minus 80 °C, sliced axially in 2 mm sections and incubated in 1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) at 37 °C for 10 min per side to allow for mitochondrial uptake of TTC. Infarct size was measured using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). Infarct size was reported as a percent of the total left ventricular area.

2.5. Real Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Sham and IR samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 degrees Celsius. RNA was isolated from ventricular tissue using an RNeasy Mini Fibrous Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was converted to cDNA using a Bio-Rad iScript cDNA synthesis kit. RT-qPCR was performed using the Bio-Rad SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix and primers for FOXO3a, SOD2, Catalase, and GAPDH (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Reactions were carried out using a BioRad CFX96 Real Time Detection System. Results were quantitated using the Comparative C(t) Method normalized to GAPDH.

2.6. Nuclear-to-Cytosolic Fractionation of Cardiac Lysate

Separation of nuclear and cytoplasmic components from cardiac lysate was adapted from instructions for the Thermo Scientific NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Product No. 78835; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL).

2.7. SDS PAGE and Western Blotting

SDS PAGE (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and gel transfer to membranes (Pharmacia Biotech, San Francisco, CA, USA) was performed at 4 °C. Antibodies for Catalase (Cat. No. 8841), FOXO3a (Cat. No. 2497), phosphorylated FOXO3a (Ser318/321) (Cat. No. 9465), histone H3 (Cat. No. 9715) and acetylated histone H3 (K9) (Cat. No. 9649) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). The antibody for α-tubulin was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Cat. No. T5168, St. Louis, MO). The antibodies for acetylated α-tubulin (Cat. No. 23950) and mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) (Cat. No. 30080) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). GAPDH antibody (Cat. No. 10RG109a) was purchased from Fitzgerald International, Inc. (Acton, MA, USA). Densitometry was performed with Image J 1.46r software (National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.8. Statistics

Data were analyzed with one way ANOVA and Tukey’s post test where appropriate. Significance was assigned at p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. HDAC inhibition was class selective

Class selective inhibition of histone deacetylase activity was confirmed through increased acetylation of HDAC substrates. Following IR, histone H3 acetylation was increased in hearts treated with MS-275 and TSA, but not in hearts treated with TubA, the selective inhibitor of HDAC6, which also functions as a tubulin deacetylase (Figure 1A). As predicted, tubulin acetylation was increased following treatment with TubA and with TSA, the pan inhibitor, but was unchanged with class I inhibition with MS-275. (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Class selective inhibition of HDAC enzymes causes increased acetylation of HDAC substrates.

Acetylation of histone H3 (A) and acetylation of αTubulin (B) were analyzed following IR. Western blots with one representative sample per group are shown. Protein content is graphed in densitometry units in ratio to vehicle and normalized to constitutive protein. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=3–5 per group. Significance with asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; n.s. = no significance

3.2. Inhibition of class I HDACs preserves LV function and reduces infarct size

There were no differences in any parameter of preischemic left ventricular contractile function between hearts from animals treated with vehicle, TSA, MS-275 or TubA (Figure 2, A to D).

Figure 2. Recovery of contractile function following IR in isolated rat hearts pretreated with class selective HDAC inhibitors.

At the end of 120 min of reperfusion, a one minute average measurement of ventricular contractile function was taken from each heart. A) dP/dtmax; B) dP/dtmin; C) Developed Pressure; Developed pressure was taken as the difference in maximum systolic and minimum diastolic pressure. D) Rate Pressure Product. Rate pressure product was calculated as the product of developed pressure and heart rate. In these graphs, Sham animals received vehicle pretreatment and are included for reference. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=6 per group. Significance as indicated by asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; n.s. = no significance

IR caused a significant reduction in every measured parameter of LV contractile function within each group, with the exception of heart rate. However, this reduction was partially attenuated with MS-275 pretreatment. Hearts from animals pretreated with the class I HDAC inhibitor MS-275 displayed a significant recovery of dP/dtmax (Figure 2A), dP/dtmin (Figure 2B), developed pressure (Figure 2C) and rate pressure product (Figure 2D) following 30 min of ischemia and 120 min of reperfusion, as compared to IR hearts treated with vehicle. Notably, there was no significant recovery in any parameter of LV contractile function from animals with hearts treated with TSA, the class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor, or tubastatin A, the HDAC6 selective inhibitor, as compared to vehicle. There were no significant differences in recovery of heart rate, minimum diastolic pressure, maximum systolic pressure or coronary flow between groups (data not shown).

In animals treated with MS-275, infarct area was markedly reduced following ischemia and reperfusion, as compared to animals treated with vehicle. There was no reduction in infarct area in hearts treated with either TSA or TubA (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Infarct area following IR in isolated rat hearts, with representative heart cross sections.

Transverse heart sections 2 mm thick were stained in triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) and photographed following IR. White areas indicate infarction, while pink areas indicate viable tissue. Infarct area was measured using ImageJ and was taken as percent of total left ventricle (LV) area minus the area of LV cavity. One representative slice from each group is shown. On the graph, mean ± S.E. is shown. N=4 per group. Significance as indicated by asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. ***p<0.001

3.3. SOD2 and catalase protein and mRNA levels are increased with MS-275 treatment

Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and catalase (CAT) are endogenous enzymes that scavenge superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, respectively, and thus protect against the free radical derived oxidation of DNA, proteins and lipids that occurs with an elevation of reactive oxygen species upon reperfusion [22]. In this way, SOD2 and CAT contribute to the cellular defenses against the pathophysiology of ischemia reperfusion injury in the heart.

Following IR, there were significant increases in mRNA levels of SOD2 (Figure 4A) and Cat (Figure 4B) with MS-275 treatment as compared to vehicle.

Figure 4. Ventricular mitochondrial superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and catalase (Cat) mRNA content following IR.

SOD2 (A) and Cat (B) content in left ventricles was analyzed following IR in vehicle and MS-275 pretreated rat hearts. Content was analyzed with real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction using the Comparitive C(t) Method, and normalized to GAPDH. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=5–6 per group. Significance with asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. *p<0.05

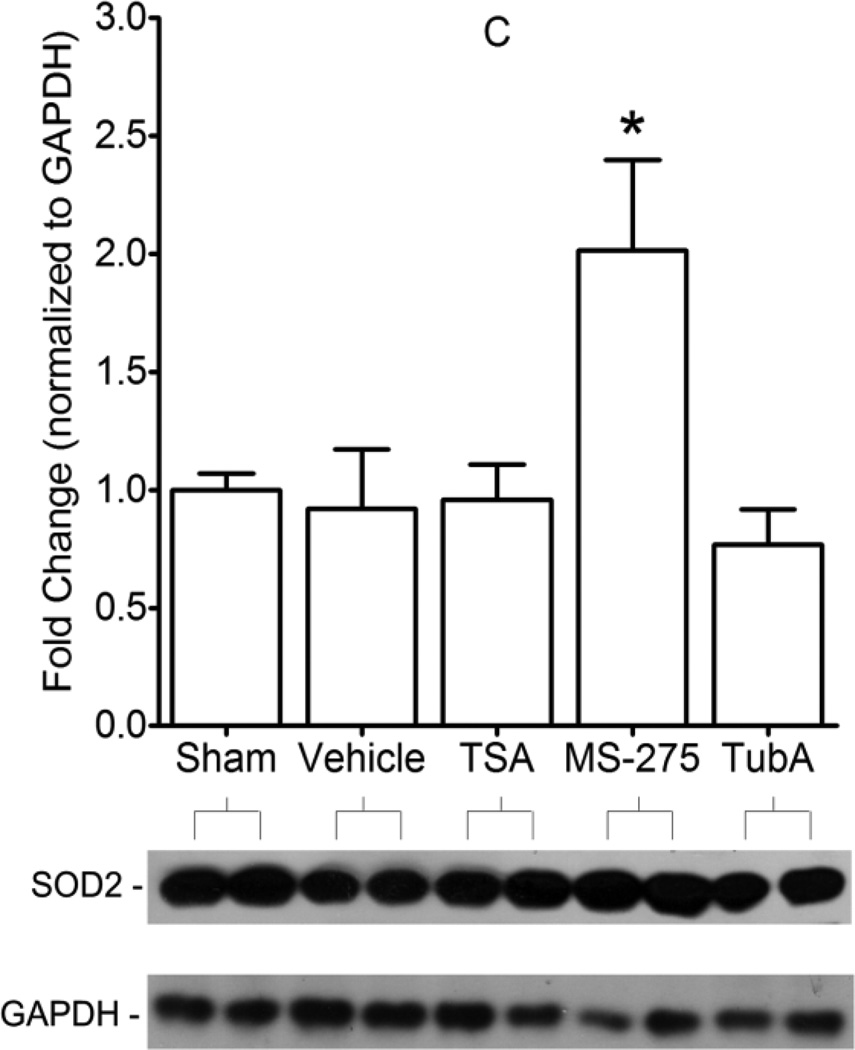

In Sham hearts, MS-275 treatment was associated with significant increases in myocardial SOD2 (Figure 5A) and CAT (Figure 5B) protein levels. These increases persisted with MS-275 treatment in hearts subjected to IR (Figure 5C-SOD2 and Figure 5D-CAT). Following IR, SOD2 and CAT content in hearts treated with vehicle and TSA were not different than Sham. Interestingly, in hearts subjected to IR, CAT content was significantly decreased with TubA as compared to vehicle.

Figure 5. Left ventricular protein content in Sham or IR hearts treated with vehicle or HDAC inhibitors.

In Sham animals that were pretreated with vehicle or MS-275, SOD2 (A) and CAT (B) protein content was analyzed by densitometry, and significance is in comparison to vehicle. In IR animals, SOD2 (C) and CAT (D) protein content was analyzed by densitometry in all treatment groups, and significance is in comparison to vehicle; Sham (vehicle treated rats that did not receive IR) is also shown on graphs C and D for normalization. Protein content is graphed in densitometry units in ratio to Sham and normalized to αtubulin or GAPDH. Western blots with one representative sample per group are shown in A and B, and two representative samples per group are shown in C and D. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=3–4 per group. Significance with asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

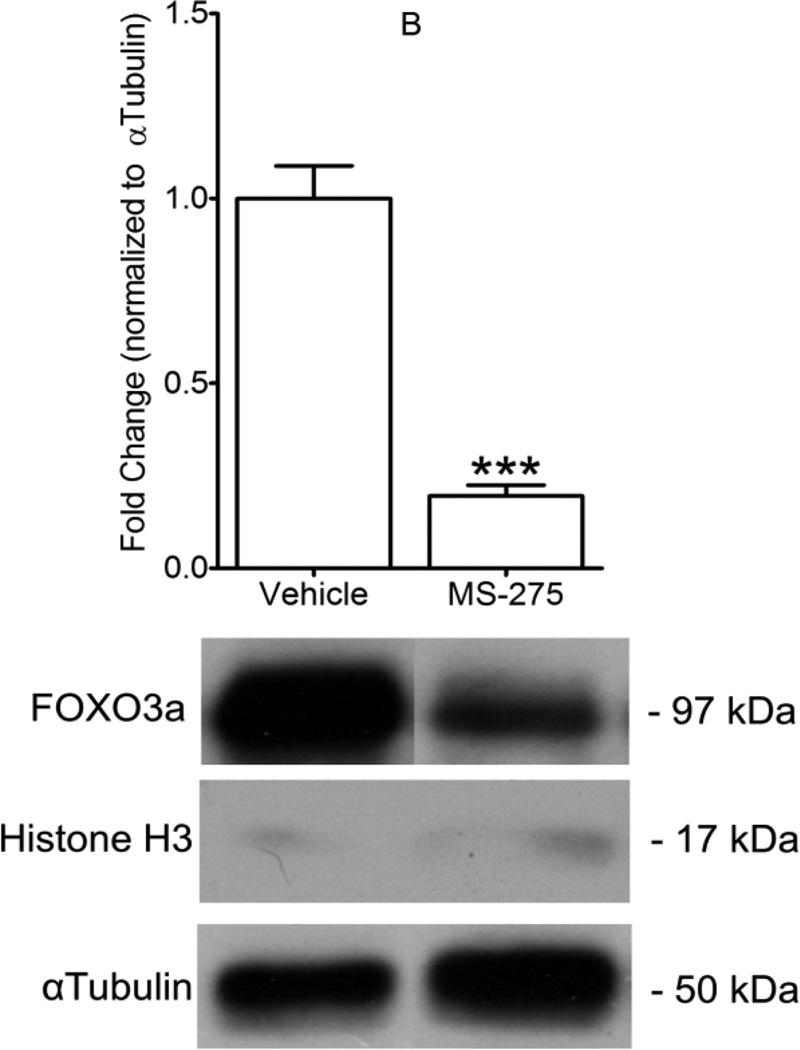

3.4. Nuclear FOXO3a protein is enriched with MS-275 treatment

SOD2 and CAT expression is known to be regulated by the FOXO3a transcription factor [19, 20]. Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fractionation was performed on ventricular tissue following IR. MS-275 pretreatment was associated with cytoplasmic exclusion and nuclear enrichment of FOXO3a. FOXO3a protein content was increased nearly 30 fold in the nuclear fraction of cardiac lysate with MS-275 treatment, compared to vehicle treated hearts (Figure 6A), whereas FOXO3a protein levels in the cytoplasmic fraction were nearly 4 fold less with MS-275 treatment (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Class I HDAC inhibition causes nuclear enrichment of FOXO3a.

Following IR, nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fractionation was performed on cardiac lysates in hearts from animals that received vehicle or MS-275 pretreatment. FOXO3a content in nuclear fractions (A), and cytoplasmic fractions (B), was analyzed by Western blot and one representative sample per group is shown. Protein content is graphed in densitometric units and normalized to total histone H3 in nuclear fractions, and to αTubulin in cytoplasmic fractions. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=5 per group. Significance with asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. ***p<0.001

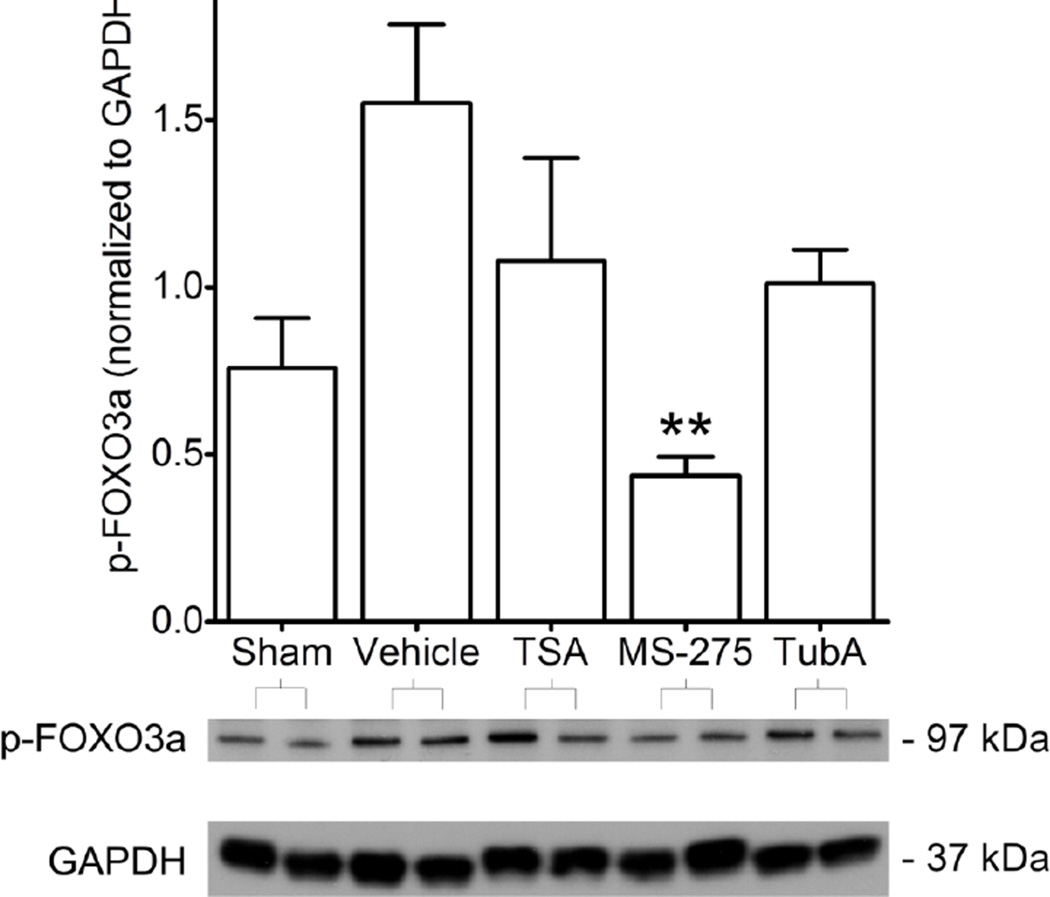

Phosphorylation of FOXO3a at serines 318/321 is required for its exclusion from the nucleus and downregulation of FOXO3a mediated transcription [23]. Following IR, there were significant increases in p-(S318/321)-FOXO3a in hearts treated with vehicle, as compared to Sham hearts (Figure 7). This increase from Sham was not observed in hearts taken from animals pretreated with HDAC inhibitors. However, within the IR groups, only MS-275 treatment was associated with significantly less p-(S318/321)-FOXO3a content, as compared to vehicle.

Figure 7. Phosphorylation of FOXO3a at Ser318/321.

Phosphorylation of FOXO3a at Serines 318/321, essential nuclear exclusion sites of FOXO3a, were analyzed by Western blot in animals that received vehicle without IR (Sham) and animals that received IR with vehicle or HDAC inhibitor pretreatment. Western blots with two representative samples per group are shown. Protein content is graphed in densitometric units and normalized to GAPDH. Mean + S.E. is shown. N=3–4 per group. Significance with asterisks is in comparison to vehicle. **p<0.01

4. Discussion

This study examined the idea that activation of pharmacologic protection in the heart by small molecule inhibition of histone deacetylases is class selective. In confirmation of our hypothesis, selective inhibition of class I HDACs, but not the class IIb HDAC6, prompted protective effects against ischemia reperfusion injury in the isolated heart. Selectively inhibiting HDAC6 alone resulted in no benefit to contractile function, and may even be detrimental to levels of cardioprotective endogenous antioxidants, specifically catalase. In addition to possessing two deacetylase domains, HDAC6 also has a ubiquitin binding domain, which is central to its role as a master regulator of lysosome formation, autophagosome maturation and autophagy [24]. Because autophagosome clearance is crucial to the survival of cardiomyocytes following IR injury, HDAC6 inhibition may be detrimental to the cellular response to IR in the heart [25]. Therefore, class I/IIb HDAC inhibition may reduce the beneficial enzymatic activity of certain isoforms, specifically HDAC6. In support of this idea, the class I/IIb HDAC inhibitor TSA was slightly protective, but was not beneficial in significantly restoring function to the levels seen in hearts treated with MS-275. Another possibility is that TSA inhibited class IIa HDACs in our study, although TSA is a very weak inhibitor of class IIa HDACs in the micromolar range [9]. At least in liver, class IIa HDACs recruit HDAC3, which in turn activates certain FOXO family transcription factors [26]. Therefore, inhibition of class I and IIa HDACs with TSA may oppose the beneficial effects of enriched nuclear FOXO3a observed with MS-275. Taken together, our results indicate that isoform selective HDAC inhibitors may provide more efficacy than the so called “pan” inhibitors in cardiac IR.

Our results using class I/IIb inhibition of HDACs by TSA are in contrast with those of Zhao and Zhang et al. They demonstrated reduction in infarct size and preservation of end diastolic pressure and rate pressure product with pharmacologic preconditioning by TSA in isolated mouse hearts subjected to IR [12], whereas we did not with rat hearts. The size of groups used to demonstrate infarct size reduction with class I HDAC inhibition was rather small in our study. However, this observation is supported by the recognized association between SOD2 levels and infarct size reduction, and bolstered by the observation of improved contractile function after 2 hours of reperfusion [27].

Our study differed with Zhao and Zhang et al. in key areas. Though the duration of ischemia was 30 minutes in our study and in each of theirs, they reperfused for only 30 minutes, whereas our reperfusion period was set at 2 hours. Ferrera et al. showed that one hour of reperfusion is required for measurements of infarction, but it is not clear if 30 minutes of reperfusion is sufficient for infarct development [21]. However, we did not observe improvements in contractile function with TSA after 30 min of reperfusion (data not shown). Second, hydroxamate based HDAC inhibitors such as TSA exhibit fast on/fast off binding characteristics, whereas benzamide based inhibitors such as MS-275 exhibit slow tight binding of HDACs, which may account for the potency of class I HDAC inhibition [28]. In an attempt to partially compensate for this possibility, we chose to administer a second dose of each HDAC inhibitor one hour prior to heart isolation. Third, our dose of TSA (1.0 mg/kg) was an order of magnitude larger than the dose used in the studies by Zhao and Zhang et al. (0.1 mg/kg) [12, 13, 14, 15]. However, in the study by Granger et al., administration of TSA at 1.0 mg/kg reduced infarct area, though this work was performed in an in vivo model of regional IR in mice [10]. TSA may have inhibited HDAC6 activity more efficiently in our study, an effect which may reduce the protection afforded by its concurrent inhibition of class I HDACs. To further explain these differences, we examined one mechanism by which class I HDAC inhibition may protect the heart from IR, namely by increasing antioxidant enzyme content.

SOD2 and catalase represent a defense system against the free radical damage to cardiomyocytes that occurs upon reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium [22]. No change in SOD2 and catalase levels were observed following IR in our model. In contrast to this observation, Sengupta et al. demonstrated that catalase and SOD2 expression are increased following prolonged hypoxia in cardiomyocytes [29]. However, within the same study, Sengupta et al. showed relative constant levels of SOD2 and catalase in a whole animal mouse model of acute cardiac IR. Rat hearts exhibit improved contractile recovery from ischemia with combined SOD2 and catalase supplementation upon reperfusion [30]. Adenovirus mediated overexpression of SOD2 and catalase protects recovery of LV contractile function in isolated, perfused neonatal mouse hearts [31].

Catalase and Sod2 are recognized targets of FOXO3a [19, 20]. FOXO transcription factors regulate cellular adaptation to stressors and activate prosurvival or proapoptotic gene programs, depending on context [32]. With MS-275 treatment in our study, FOXO3a was enriched and retained in the nucleus where, ostensibly, transcription of the genes encoding catalase and SOD2 could proceed without interruption. In support of the idea that FOXO3a activity is enhanced by nuclear localization, mRNA and protein of SOD2 and CAT in IR hearts treated with MS-275 were higher than in hearts treated with vehicle.

FOXO3a activity is directly controlled by combinations of posttranslational modification [32]. In our study, MS-275 treatment was associated with a decrease in a key FOXO3a nuclear exclusion signal, suggesting that inhibition of class I deacetylase activity may attenuate the oxidative stress component of IR injury by modifying posttranslational crosstalk between acetylation and phosphorylation [7]. These results are similar to Cavasin et al., in which another class I HDAC inhibitor, MGCD0103, was associated with reduction in FOXO3a phosphorylation at an important inactivation site [33]. The precise mechanisms by which this crosstalk occurs are under investigation. For instance, it is known that the NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 deacetylates and represses the activity of FOXO3a [34]. Conversely, increased SIRT3 levels under oxidative stress cause reduced FOXO3a acetylation and increased transcriptional activity [35]. Furthermore, acetylation of FOXO3a may enable efficient phosphorylation by Akt, which in turn may enable FOXO3a association with 14-3-3 proteins and nuclear exclusion [36]. It is unknown if SOD2 and catalase are directly regulated by zinc dependent HDAC activity, though SOD2 is known to be regulated through acetylation by SIRT3 [37]. Future studies should test the possibility that a class I HDAC associates with and deacetylates FOXO3a.

Our study provides one possible mechanism by which class I HDAC inhibition may protect the heart from IR. Clearly, other possibilities exist that may contribute to the protective effect of class I HDAC inhibition. There is evidence that the Foxo3a gene is a direct target of class I HDACs. In the report by Shimazu et al., inhibition of HDAC1/2 catalytic activity with the endogenous HDAC inhibitor βhydroxybutyrate caused an increase in histone acetylation at the Foxo3a promoter in HEK293 cells [19]. This was correlated with increases in FOXO3a and its targets Catalase and Sod2 in kidney tissue, and with decreases in markers of paraquat induced oxidative stress. Other transcription factors may target Sod2, and these effects may be cell specific. For instance, Maehara et al. demonstrated that HDAC1 in complex with the Sp1 transcription factor inhibits transcription of the gene encoding SOD2 in murine myoblasts, an effect which was partially antagonized by TSA [38]. Alternatively, HDAC3 reversibly deacetylates both α and β myosin heavy chain, reducing their affinity for actin, and thus decreasing myosin motor activity [39]. It is reasonable to posit from this that pharmaceutical inhibition of HDAC3 activity might enhance myosin acetylation and increase contractility. Furthermore, microRNA activation may be involved. MiR126 is activated by the combination of TSA and hypoxia, leading to activation of prosurvival kinases ERK1/2 and Akt, suggesting a protective role for miR activation by HDAC inhibitors in ischemia [40]. In fact, when Akt1 is deleted, HDAC inhibition with TSA is no longer effective at reducing infarct size and preserving LV contractile function in IR mouse hearts [15].

4.1. Conclusions

Selective inhibition of class I HDACs is associated with a cardioprotective phenotype in Langendorff perfused rat hearts subjected to IR. This cardioprotection is associated with nuclear localization of FOXO3a and increased expression of its transcription products SOD2 and catalase. This protection is not present when HDAC6 is selectively inhibited. This study provides the first evidence that class I HDAC inhibition confers protective benefits to the ischemic reperfused heart, and that inhibition of HDAC6, the class IIb HDAC, provides no benefit and may even be detrimental. In addition to describing the ability to protect the ischemic heart by pharmacologically increasing antioxidant proteins, this study emphasizes the need for the development of new strategies that target specific HDAC isoforms in cardiac ischemia reperfusion.

Highlights.

Class I HDAC inhibitors protected isolated hearts from reperfusion injury.

Class I HDAC inhibition correlated with increased SOD2 and Catalase.

A common class I/IIb inhibitor and an HDAC6 inhibitor did not protect hearts.

Nonselective HDAC inhibitors may reduce beneficial effects of HDAC6.

This is the first report of class selective HDAC inhibition in cardiac IR injury.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Mona Li, M.D., University of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, for excellent editorial assistance. This work was supported, in part, by NIH Grant Number R01HL066223 to DRM. SEA was supported by NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant Number T32HL07260. DJH was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina, NIH/NCATS Grant Number TL1 TR000061.

Abbreviations

- Akt

protein kinase B

- dP/dt

rate of pressure change

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- FOXO

forkhead box protein family, subclass O

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IR

ischemia reperfusion

- HEK293

human endothelial kidney cells, line 293

- LV

left ventricle

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MiR

microribonucleic acid

- MS-275

entinostat

- PTM

post translational modification

- SOD2

superoxide dismutase variant 2, mitochondrial

- TSA

trichostatin A

- TTC

triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- TubA

tubastatin A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure. None.

References

- 1.Turer AT, Hill JA. Pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(3):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. New Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zweier JL, Flaherty JT, Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of oxygen radical generation following reperfusion of the ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(5):1404–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raedschelders C, Ansley DM, Chen DDY. The cellular and molecular origins of reactive oxygen species generation during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133(2):230–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolli R, Becker L, Gross G, Mentzer R, Jr, Balshaw D, Lathrop DA NHLBI Working Group on the Translation of Therapies for Protecting the Heart from Ischemia. Myocardial protection at a crossroads: the need for translation into clinical therapy. Circ Res. 2004;95:125–134. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137171.97172.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Seto E. Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications. Mol Cell. 2008;31(4):449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinsey TA. Therapeutic potential for HDAC inhibitors in the heart. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:303–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKinsey TA. Isoform-selective HDAC inhibitors: Closing in on translational medicine for the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granger A, Abdullah A, Huebner F, Stout A, Wang T, Huebner T, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury in mice. FASEB J. 2008;22:3549–3560. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Duan W, Lin Y, Yi W, Liang Z, Yan J, et al. SIRT1 activation by curcumin pretreatment attenuates mitochondrial oxidative damage induced by myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65C:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao TC, Cheng G, Zhang LX, Tseng YT, Padbury JF. Inhibition of histone deacetylases triggers pharmacologic preconditioning effects against myocardial ischemic injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76(3):473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang LX, Zhao Y, Cheng G, Guo TL, Chin YE, Liu PY, et al. Targeted deletion of NF-kB p50 diminished cardioprotection of histone deacetylase inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H2154–H2163. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao TC, Zhang LX, Cheng G, Liu JT. gp-91 mediates histone deacetylase inhibition-induced cardioprotection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao TC, Du J, Zhuang S, Liu P, Zhang LX. HDAC inhibition elicits myocardial protective effect through modulation of MKK3/Akt-1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Qin X, Zhao Y, Fast L, Zhuang S, Liu P. Inhibition of histone deacetylase preserves myocardial performance and prevents cardiac remodeling through stimulation of endogenous angiomyogenesis. JPET. 2012;341:285–293. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee TM, Lin MS, Chang NC. Inhibition of histone deacetylase on ventricular remodeling in infarcted rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H968–H977. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00891.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferguson BS, Harrison BC, Jeong MY, Reid BG, Wempe MF, Wagner FF, et al. Signal-dependent repression of DUSP5 by class I HDACs controls nuclear ERK activity and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(24):9806–9811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301509110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W, Shirakawa K, Le Moan N. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339(6116):211–214. doi: 10.1126/science.1227166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kops GJ, Dansen TB, Poldermann PE, Saaloos I, Wirtz KW, Coffer PJ, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature. 2002;419(6904):316–321. doi: 10.1038/nature01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrera R, Benhabbouche S, Bopassa JC, Li B, Ovize M. One hour reperfusion is enough to assess function and infarct size with TTC staining in Langendorff rat model. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2009;23(4):327–331. doi: 10.1007/s10557-009-6176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolli R. Oxygen-derived free radicals and postischemic myocardial dysfunction (“stunned myocardium”) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12(1):239–249. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furukawa-Hibi Y, Kobayashi Y, Chen C, Motoyama N. FOXO transcription factors in cell-cycle regulation and the response to oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:752–760. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Shin D, Kwon S-H. Histone deacetylase 6 plays a role as a distinct regulator of diverse cellular processes. FEBS J. 2013;280:775–793. doi: 10.1111/febs.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Liu H, Foyil SR, Godar RJ, Weinheimer CJ, Hill JA, et al. Impaired autophagosome clearance contributes to cardiomyocyte death in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2012;125:3170–3181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.041814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mihaylova MM, Vasquez DS, Ravnskjaer K, Denechaud PD, Yu RT, Alvarez JG, et al. Class IIa histone deacetylases are hormone-activated regulators of FOXO and mammalian glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2011;145(4):607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Bolli R, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Guo Y, French B. Gene therapy with extracellular superoxide dismutase protects conscious rabbits against myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103(14):1893–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou CJ, Herman D, Gottesfeld JM. Pimelic diphenylamide 106 is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of class I histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(51):35402–35409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807045200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sengupta A, Molkentin JD, Paik JH, DePinho RA, Yutzey KE. FoxO Transcription Factors Promote Cardiomyocyte Survival upon Induction of Oxidative Stress. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7468–7478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.179242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ytrehus K, Gunnes S, Myklebust R, Mjos OD. Protection by superoxide dismutase and catalase in isolated rat heart reperfusion after prolonged cardioplegia: a combined study of metabolic, functional, and morphometric ultrastructural variables. Cardiovasc Res. 1987;21(7):492–499. doi: 10.1093/cvr/21.7.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo YJ, Zhang JC, Vijayvasarathy C, Zwacka RM, Englehardt JF, Gardner TJ, et al. Recombinant adenovirus-mediated cardiac gene transfer of superoxide dismutase and catalase attenuates post-ischemic contractile dysfunction. Circulation. 1998;98(19 Suppl):II255–II260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calnan DR and Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cavasin MA, Demos-Davies K, Horn TR, Walker LA, Lemon DD, Birdsey N, et al. Selective class I histone deacetylase inhibition suppresses hypoxia-induced cardiopulmonary remodeling through an antiproliferative mechanism. Circ Res. 2012;110:739–748. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, Bultsma Y, McBurney M, Guarente L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116(4):551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sundaresan NR, Gupta M, Kim G, Rajamohan SB, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(9):2758–2771. doi: 10.1172/JCI39162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daitoku H, Sakamaki J, Fukamizu A. Regulation of FoxO transcription factors by acetylation and protein-protein interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(11):1954–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu Y, Park SH, Ozden O, Kim HS, Jiang H, Vassilopoulos A, et al. Exploring the electrostatic repulsion model in the role of Sirt3 in directing MnSOD acetylation status and enzymatic activity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maehara K, Uekawa N, Isobe K. Effects of histone acetylation on transcriptional regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;295(1):187–192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samant SA, Courson DS, Sundaresan NR, Pillai VB, Tan M, Zhao Y, et al. HDAC3-dependent reversible lysine acetylation of cardiac myosin heavy chain isoforms modulates their enzymatic and motor activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(7):5567–5577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Shi H, Chen L, Wang H, Zhu S, Dong C, Webster KA, et al. Synergistic Induction of miR-126 by Hypoxia and HDAC Inhibitors in Cardiac Myocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430(2):827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]