Abstract

Objective

To outline the efficacy and risks of bisphosphonate therapy for the management of osteoporosis and describe which patients might be eligible for bisphosphonate “drug holiday.”

Quality of evidence

MEDLINE (PubMed, through December 31, 2012) was used to identify relevant publications for inclusion. Most of the evidence cited is level II evidence (non-randomized, cohort, and other comparisons trials).

Main message

The antifracture efficacy of approved first-line bisphosphonates has been proven in randomized controlled clinical trials. However, with more extensive and prolonged clinical use of bisphosphonates, associations have been reported between their administration and the occurrence of rare, but serious, adverse events. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures might be related to the use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis, but they are exceedingly rare and they often occur with other comorbidities or concomitant medication use. Drug holidays should only be considered in low-risk patients and in select patients at moderate risk of fracture after 3 to 5 years of therapy.

Conclusion

When bisphosphonates are prescribed to patients at high risk of fracture, their antifracture benefits considerably outweigh their potential for harm. For patients taking bisphosphonates for 3 to 5 years, reassess the need for ongoing therapy.

Postmenopausal osteoporosis is characterized by accelerated loss of bone mass and deterioration of bone architecture, leading to increased fracture risk.1 Osteoporotic fractures decrease personal independence,2 increase morbidity,3–5 and shorten life6,7; thus, their prevention is paramount.

Aminobisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronic acid) are first-line therapies for the prevention of fracture in high-risk individuals.8 Aminobisphosphonates might also increase survival in ways at least partially independent of their contribution to decrease in fracture incidence.9–11 While the antifracture efficacy and relative safety of the aminobisphosphonates have been well established in clinical trials,12–16 there have been concerns that prolonged use of these drugs might increase the risk of rare, but serious, adverse events.17–21

Clinical vignette

Your 71-year-old patient, Mrs Jones, saw you today to review her bone mineral density (BMD) report. She has been well and compliant with alendronate (70 mg once a week), in addition to vitamin D (1000 IU/d) and adequate dietary calcium intake, for the past 6 years. However, her friends have told her that she should discuss stopping her bisphosphonate therapy with you because she has been taking it long enough and it might cause her serious harm. She sought your opinion.

In reviewing her file, you noted that you first ordered a BMD measurement when she was 65 years old in order to assess her fracture risk. At that time, her BMD T-score was −2.8 at the lumbar spine and −2.5 at the femoral neck. She had never sustained a fragility fracture nor used glucocorticoids. She was healthy, except for hypertension, which she controlled by taking ramipril and hydrochlorothiazide. She had never smoked, only consumed alcohol occasionally, and had no family history of osteoporosis or fractures. On examination, you determined she had lost as much as 5 cm in height since she was 25 years old. Five years ago, her 10-year absolute risk of fracture was defined as moderate according to the current Osteoporosis Canada guidelines (10% to 20% probability of a major osteoporotic fracture). You decided to order a lateral spine x-ray scan to rule out vertebral fractures.22 The radiology report confirmed grade 2 (25% to 40% reduction in vertebral height) compression fractures in the thoracic vertebrae T10 and T11, moving her into the high-fracture-risk category. After discussion, you had initiated weekly alendronate along with supplemental calcium and vitamin D. Since then, she has not suffered any recurrent fractures and has been taking an appropriate dose, has tolerated the medication well, and has had no further height loss. She also started a walking program 3 times per week.

Quality of evidence

MEDLINE (PubMed) was searched using combinations of the key words alendronate, risedronic acid, zoledronic acid, etidronic acid, bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw, atrial fibrillation, esophageal neoplasms, renal insufficiency, chronic, atypical, femoral fracture, drug holiday, and discontinuation, for all dates to December 31, 2012. The search was limited to human studies published in English. Additional relevant investigations were gathered from the reference sections of reviewed articles and from surveying Canadian osteoporosis experts. Abstracts from the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research annual meetings for the years 2008 to 2012 were also searched for relevant investigations. Relevant studies addressing the primary questions were retained and reviewed for inclusion. The level of evidence was primarily level II, and to a lesser extent level I, as most publications were observational studies or case reports (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature grading scale

| LEVELS OF EVIDENCE | TRIAL DESIGNS |

|---|---|

| Level I | At least 1 properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis |

| Level II | Other comparison trials; non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies; and preferably more than 1 study |

| Level III | Expert opinion or consensus statements |

Main message

Unique characteristics of aminobisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates, potent inhibitors of osteoclast-mediated bone remodeling, bind to bone and have prolonged residence in the skeleton. Bisphosphonates can remain bound to bone for many years; those with greater binding affinities (zoledronic acid > alendronate > ibandronate > risedronate > etidronate) possess longer skeletal residency.23 Consequently, after bisphosphonate discontinuation, bound bisphosphonate provides residual pharmacologic action for many years,23,24 in contrast to other antiresorptive therapies in which activity is quickly lost after discontinuation (ie, denosumab, estrogen, raloxifene, and calcitonin).25–27

Safety of long-term bisphosphonate use

As osteoporosis is a chronic disease, antifracture therapy could conceivably continue for the rest of a patient’s life. While there are non-bisphosphonate therapies available to decrease fracture risk in high-risk individuals, many, other than denosumab, do not have evidence of efficacy comparable to that for the aminobisphosphonates at vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip sites. Unfortunately, there are few data to guide use of any osteoporosis therapy for more than 3 to 5 years.

The phase 3 trials for bisphosphonates assessed relatively small patient populations (1000 to 8000 patients) for short durations (usually 3 years) and excluded up to 80% of patients who might seek osteoporosis therapy in actual clinical practice.28 Postmarketing reports based upon millions of patient-years29 and long-term (longer than 5 years) clinical administration have suggested associations between some previously unknown, rare adverse events and bisphosphonate use—including osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures (AFF), atrial fibrillation (AF), and esophageal cancer.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is defined as the presence of exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that does not heal within 8 weeks of identification by a health care provider, in the absence of radiation therapy.30 Osteonecrosis of the jaw is not just “jaw pain” and is easily assessed with conservative measures. At the present time, evidence suggests that there is a dose-response relationship between bisphosphonate use and the development of ONJ.31 While the current consensus accepts a causal relationship between bisphosphonate exposure and ONJ, the pathologic mechanism or mechanisms have yet to be elucidated. Furthermore, in a clinical trial involving breast cancer patients treated with high-dose denosumab (120 mg monthly administered subcutaneously) over 3 years, 2.0% of patients developed ONJ, which was similar to the incidence observed in patients who received monthly high-dose intravenous zoledronic acid (1.4%).32 The development of ONJ with denosumab administration demonstrates that ONJ is not specific to bisphosphonates, but more likely a characteristic of potent antiresorptive agents.

In a recent survey of Canadian physicians, the cumulative incidence of bisphosphonate-associated ONJ was 0.4% (400 in 100 000) for cancer patients but only 0.001% (1 in 100 000) for osteoporosis patients.33 This ONJ incidence with the relatively lower-dose osteoporosis treatment is similar to that reported by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research task force, estimated to be between 1 in 10 000 and less than 1 in 100 000 patient-treatment years.30 Further, a recent Scottish survey of 900 000 patients concluded that the incidence of bisphosphonate-associated ONJ was about 4 per 100 000 patient-years.34 Therefore, bisphosphonate-associated ONJ is very rare in the context of treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nonetheless, it is suggested that patients should complete any invasive dental procedures before initiating bisphosphonates to minimize the already small risk; however, those taking bisphosphonates should not delay emergency dental procedures or dental implants. Factors associated with the development of ONJ include poor oral hygiene and administration of high-dose antiresorptive treatment in oncology patients. A recent study in a rice rat model of periodontitis (development of periodontitis promoted through the administration of a high-sucrose and casein diet) comparing vehicle, alendronate, and low- and high-dose intravenous zoledronic acid showed that only high-dose zoledronic acid induced ONJ-like lesions in the mandibles of rice rats after 18 and 24 weeks of treatment.35

Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fracture

The defining characteristics of AFF include location in the subtrochanteric region or femur shaft, minimal or no trauma, transverse or short oblique fracture line, absence of comminution, and a medial spike with complete fracture.36 These fractures can be complete or incomplete, and are often bilateral (in up to two-thirds of cases). Minor features often include prodromal thigh pain,36–38 cortical thickening, periosteal reaction in the lateral cortex, delayed healing, comorbid conditions, and concomitant drug exposures including bisphosphonates, glucocorticoids,20,21,39–46 and proton pump inhibitors.46 Presence of prodromal thigh pain should trigger x-ray scan of the full-length femurs or radioisotope bone scan to investigate for signs of AFF.36

Subtrochanteric and shaft fractures account for 4% to 10% of all femur fractures,47–50 and of these only a minority are AFFs. Little is known about the factors associated with the development of AFFs. Concern has arisen that long-term bisphosphonate use might increase the risk of these fractures through a number of putative mechanisms.31,36,51

Long-term clinical trial data (10 years for alendronate,52–54 7 years for risedronate,55 6 years for zoledronic acid56) have not demonstrated an increase in AFF incidence with prolonged bisphosphonate exposure, but such studies are too small to detect rare events. To better address this concern, Black and colleagues57 pooled several phase 3 clinical trials of aminobisphosphonates and found no increased incidence of AFF with bisphosphonate use. However, the limited population size, short duration of exposure, and lack of access to the radiographic images in these trials might have limited the ability of the review to identify these very rare fracture events.

To date, there has been no direct causal evidence linking the use of bisphosphonates to the occurrence of AFF, although the number of case reports, case series, and cohort analyses demonstrating an association between the 2 is growing.20,21,37–39,41–43,48,51,57–66 Up to half of AFFs occur in people not exposed to bisphosphonates, complicating estimates of bisphosphonate-associated incidence.39,64,67–71 Further complicating the understanding of AFF occurrence is that they might be more associated with the presence of osteoporosis than with exposure to bisphosphonates.63 Most (80% to 85%) bisphosphonate-associated AFFs occurred while taking alendronate,46 likely reflective of its earlier availability and more widespread use as opposed to other aminobisphosphonates (risedronate, pamidronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid).

Two large studies have provided radiographically adjudicated incidence estimates of bisphosphonate-associated AFFs. Schilcher et al62 assessed all hip fractures that occurred in Sweden in 2008 (12 777 hip fractures, 59 AFFs) and linked these to individual prescription data. Although the age-adjusted relative risk (RR) of AFF with use of any bisphosphonate was 47.3 (95% CI 25.6 to 87.3), the absolute difference between users and non-users was 5 cases (95% CI 4 to 7) per 10 000 patient-years (50 cases per 100 000 patient-years). The risk of AFF, which appeared in this study to be independent of comorbid conditions and medication, increased with longer duration of use (odds ratio [OR] = 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6, per 100 prescribed daily doses), with a 70% reduction in risk for every year following discontinuation (adjusted OR = 0.28, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.38). Dell et al38 identified all nontraumatic subtrochanteric and femur shaft fractures that occurred in patients in a large US population (2.6 million patients) between 2007 and 2009 (approximately 15 000 femur fractures). Bisphosphonates were taken by 97 of the 102 AFF patients for an average of 5.5 years. The risk of an AFF increased with duration of bisphosphonate use from 2 cases per 100 000 patient-years for 2 years of treatment to 78 cases per 100 000 patient-years for 8 years of treatment. While the finding of increasing risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal fracture risk with increasing duration of bisphosphonate use has been corroborated by other investigations that did not have radiographic adjudication,46,72 not all investigations have found this association.48

While AFFs appear to be associated with bisphosphonate use, this risk needs to be put into perspective. From 1996 to 2007, age-adjusted US hip fracture incidence declined by 31.6% in women (from 1020.5 to 697.4 per 100 000 women) while bisphosphonate use increased (from 3.5% in 1996 to 16.6% in 2007); however, age-adjusted rates of subtrochanteric and femur shaft fracture incidence increased by 20.4% in women (from 28.4 per 100 000 women in 1999 to 34.2 per 100 000 in 2007).73 When using age-adjusted rates, the authors of this study estimated that “for every 100 or so reduction in typical femoral neck or intertrochanteric fractures, there was an increase of 1 subtrochanteric fragility fracture.”73

For high- and moderate-risk individuals, the risk of an AFF is greatly overshadowed by the antifracture benefit gained from bisphosphonate therapy; the lifetime risk of hip fracture is 1 fracture in 8 Canadian women,74 and aminobisphosphonate therapy in high-risk individuals decreases this risk by 20% to 50% over 3 years of therapy.75 If aminobisphosphonates are provided to high-risk patients (eg, with previous vertebral fracture), approximately 1000 nonvertebral and 2300 clinical vertebral fractures would be prevented per 100 000 person-years of treatment.36 For a moderate-risk population (femoral neck BMD T-score < −2.0) there would be approximately 700 nonvertebral and 1000 clinical vertebral fractures prevented per 100 000 person-years with treatment.36 However, for the patient with a low risk of fracture, the risk-to-benefit ratio supports the recommendations of supplementing with calcium and vitamin D and lifestyle modification only.8

In their review released in December 2011, Health Canada concluded:

Although the risk is higher with bisphosphonate use, it is still extremely small. The benefits of using bisphosphonate drugs in preventing fractures associated with osteoporosis outweigh the risk of an atypical femur fracture.76

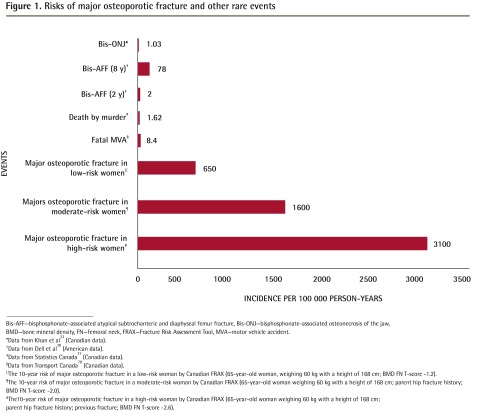

Figure 133,38,77,78 provides a comparison of the absolute risks of bisphosphonate-related ONJ or AFF compared with the risk of suffering major osteoporotic fracture in untreated postmenopausal women of low, moderate, and high fracture risk.

Figure 1.

Risks of major osteoporotic fracture and other rare events

Bis-AFF—bisphosphonate-associated atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fracture, Bis-ONJ—bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw, BMD—bone mineral density, FN—femoral neck, FRAX—Fracture Risk Assessment Tool, MVA—motor vehicle accident.

*Data from Khan et al33 (Canadian data).

†Data from Dell et al38 (American data).

‡Data from Statistics Canada77 (Canadian data).

§Data from Transport Canada78 (Canadian data).

‖The 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture in a low-risk woman by Canadian FRAX (65-year-old woman, weighing 60 kg with a height of 168 cm; BMD FN T-score −1.2).

¶The 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture in a moderate-risk woman by Canadian FRAX (65-year-old woman weighing 60 kg with a height of 168 cm; parent hip fracture history; BMD FN T-score −2.0).

#The10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture in a high-risk woman by Canadian FRAX (65-year-old woman weighing 60 kg with a height of 168 cm; parent hip fracture history; previous fracture; BMD FN T-score −2.6).

Atrial fibrillation

The first trial to suggest an association between AF and bisphosphonate use was the pivotal 3-year phase 3 trial for zoledronic acid in which there was an increased risk of AF requiring hospitalization in patients provided zoledronic acid compared with placebo recipients (1.3% vs 0.5%, P < .001).14 Following this, a small case-control study reported an 86% (95% CI 9% to 215%) increased risk of AF with alendronate use (2.67% absolute risk difference between cases and controls).18

However, recent large database analyses79–81 and a meta-analysis82 have concluded that there is no association between the use of bisphosphonates and the incidence of AF, with 1 study even suggesting a protective effect.83 Therefore, at this time, the weight of the evidence would suggest no association between bisphosphonate use and AF.84

Esophageal cancer

Exposure of the esophagus to bisphosphonates has been suggested to be a risk factor in the development of esophageal cancer.19 Green et al85 analyzed the UK General Practice Research Database cohort and reported that regular use of oral bisphosphonates over an approximately 5-year period doubled the risk of esophageal cancer in 60- to 79-year-old patients (from 1 case per 1000 patients to 2 cases per 1000 patients with 5 years of use). However, Cardwell et al86 performed an analysis of the same database and found no association between oral bisphosphonate use and esophageal cancer, with a hazard ratio of 1.07 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.49). Different study designs, observation lengths, and underlying study populations might partially explain the divergent findings of these 2 trials.87 A recent Danish register-based, open cohort study found no increase in esophageal cancer deaths or incidence between 36 606 alendronate users and 122 424 matched controls.88 At this time, there is no consistent indication of elevated risk of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use, but more data are needed.

Renal function and bisphosphonates

In patients with poor renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than 35 mL/min), bisphosphonates are contraindicated. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration updated the drug label for zoledronic acid to state that it is contraindicated in patients “with creatinine clearance less than 35 mL/min or in patients with evidence of acute renal impairment” and further recommended that physicians screen patients for such impairments before initiating treatment with zoledronic acid.89 It is important that all patients be well hydrated before initiating infusions, which should occur over a minimum of 15 minutes.

In patients with osteoporosis complicated by concomitant diseases or conditions (eg, renal failure) or their respective medications (eg, biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis), referral to a specialist should be considered.

Bisphosphonate drug holiday

With increased safety concerns surrounding the long-term use of bisphosphonates,30,36,85 questions have arisen regarding the applicability of “drug holidays” to minimize long-term bisphosphonate exposure and avoid potential adverse events while maintaining some degree of antifracture efficacy through the residual antiresorptive activity of retained bisphosphonate.

The 2010 Osteoporosis Canada guidelines state that “Individuals at high risk for fracture should continue osteoporosis therapy without a drug holiday [grade D].”8 However, since these guidelines were published, additional data have become available to further guide our decision making. The US Food and Drug Administration has recently published guidance in this regard.90

Questions about drug holidays

Are there risks associated with bisphosphonate drug holidays? An important question to pose when considering bisphosphonate drug holidays is whether such holidays are associated with unacceptable risks. There are few data to guide recommendations, but 2 randomized controlled trials with placebo comparator groups, both extensions of pivotal phase 3 trials, have provided some important insights: the FLEX (Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension)53 trial with alendronate and the HORIZON (Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic acid Once Yearly) extension trial with zoledronic acid.56 In the FLEX trial, patients who had persisted with 5 years of alendronate therapy were re-randomized to either continuing alendronate or receiving a placebo for a further 5 years, whereas in the HORIZON extension trial patients who previously had 3 years of yearly zoledronic acid infusions were then re-randomized to either continuing zoledronic acid or receiving placebo infusions for 3 more years. In both trials, the groups that continued therapy had maintenance or small increases of BMD and continued bone turnover marker suppression, whereas there were declines in hip BMD and gradual increases in markers of bone turnover in the groups that discontinued therapy (total hip BMD in the FLEX trial returned to the pretreatment Fracture Intervention Trial baseline after 5 years of discontinuation). In the FLEX study, fracture incidences were similar between the 2 groups, with the exception of clinical vertebral fractures (those that came to clinical attention), which were significantly lower after 5 years in the group that continued alendronate compared with the group that was switched to placebo (RR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.85) (Table 2).53,56,91 In the HORIZON extension trial, after 6 years, the group that continued zoledronic acid for a total of 6 years had a significantly lower incidence of radiographically adjudicated vertebral fracture (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.95) compared with the group that discontinued zoledronic acid after 3 years.56 Thus, these trials demonstrated that for some patients there was an increased risk of vertebral fracture as early as 3 years after discontinuation. In patients who received 3 years of risedronate therapy and who were then followed for a year after discontinuation, there was a mean loss of BMD back to baseline levels, although significant antifracture efficacy remained at the spine as compared with placebo (RR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.86).91 It bears noting that none of these extension studies were designed or powered to evaluate efficacy on vertebral or nonvertebral fractures; these trials were designed to evaluate safety and collected fracture events as safety parameters—thus the importance of the fracture data collected in these studies needs to be viewed in light of this.92

Table 2.

Drug holiday studies

| STUDY | COMPARATOR GROUPS | LENGTH OF TREATMENT, Y | DRUG HOLIDAY, Y | FRACTURE CHANGES DURING DRUG HOLIDAY PERIOD | SURROGATE MEASURE CHANGES DURING DRUG HOLIDAY PERIOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watts et al,91 2008 | RIS vs PBO | 3 | 1 |

|

|

| Black et al,53 2006 | ALN (10 y) vs ALN (5 y) then PBO (5 y) | 5 or 10 | 5 |

|

|

| Black et al,56 2012 | ZOL (6 y) vs ZOL (3 y) then PBO (3 y) | 3 or 6 | 3 |

|

|

ALN—alendronate, BMD—bone mineral density, BTM—bone turnover markers, FN—femoral neck, HR—hazard ratio, LS—lumbar spine, NS—not statistically significant, OR—odds ratio, PBO—placebo, RIS—risedronate, RR—relative risk, TH—total hip, ZOL—zoledronic acid.

Curtis et al93 evaluated the risk of hip fracture after discontinuation of bisphosphonates after at least 2 years of active therapy. They found that those women who continued taking bisphosphonates had a significantly lower risk of hip fracture compared with those who discontinued (4.67 vs 8.43 versus per 1000 person-years, respectively; P = .016), but that the difference in risk was diminished by either longer duration of bisphosphonate administration or by high compliance to therapy.

When and for whom should bisphosphonate holidays be considered? There are few data to suggest the optimal treatment duration or the optimal time to consider a bisphosphonate holiday. As some studies have reported that the incidence of AFFs might increase after 5 years of bisphosphonate use,38,72 it seems reasonable to suggest that consideration of a drug holiday be made after this time point in patients who are thought to be at lower risk of fragility fractures.

A post hoc analysis of the HORIZON extension trial identified an osteoporotic femoral neck BMD at discontinuation (ie, T-score ≤ −2.5), a history of fragility fracture, or prevalent vertebral fracture as being associated with increased risk of fracture after zoledronic acid discontinuation.94 Based on these findings, together with similar results from the FLEX study,95 high-risk patients with osteoporotic BMD or history of fragility fracture (including prevalent vertebral fracture) should not be candidates for bisphosphonate holiday, as was also recommended by Black et al96 in a recent position paper. Patients at low risk of fracture should usually discontinue bisphosphonate therapy,8 and many who are at moderate risk might also be candidates for drug holiday. Table 3 summarizes some empirical guidelines to help determine which patients might be considered for drug holidays from bisphosphonates.

Table 3.

Guidelines for bisphosphonate holiday decisions

| FRACTURE RISK | CLINICAL PROFILE AND TESTS | IS A BISPHOSPHONATE HOLIDAY APPROPRIATE? |

|---|---|---|

| Low (< 10% 10-y risk) |

|

|

| Moderate (10%–20% 10-y risk) |

|

|

| High (> 20% 10-y risk or previous fragility vertebral or hip fracture or > 1 fragility fracture after the age of 40 y) | NA |

|

BMD—bone mineral density, NA–not applicable.

Monitoring during the drug holiday

There are no data to suggest the most appropriate time to reinitiate therapy once a bisphosphonate holiday has been initiated. Monitoring a holiday with annual BMD or bone turnover markers might not be an adequate reflection of antifracture efficacy, as changes in these measures after discontinuation are only weakly correlated with changes in fracture risk.91 Therefore, their use to monitor a drug holiday is currently not recommended on an annual basis. Measurement of BMD could be considered 2 or 3 years following discontinuation to detect if rapid losses in BMD have occurred. Monitoring with bone turnover markers could also be contemplated in locales where such testing is currently available, but there are no specific recommendations on target values or testing intervals. Consider reevaluation of fracture risk after 2 years.

Because it is difficult to monitor a drug holiday with current measures, it might be best to provide predefined holiday durations based on each bisphosphonate’s respective bone affinity: alendronate and zoledronic acid have high affinity and longer binding durations; risedronate has lower affinity and shorter binding durations. Data from the FLEX and HORIZON extension trials would suggest that for some patients 5 years off of alendronate and 3 years’ holiday from zoledronic acid was safe, but for some it was too long and resulted in a significant increase in vertebral fracture risk.53,56 It should be noted that many women in the FLEX study were actually of low to moderate fracture risk at the outset.12,13 In another trial, after 3 years of risedronate therapy there was a loss of BMD back to baseline levels after only a year of discontinuation, although significant antifracture efficacy remained at the spine as compared with placebo (RR = 0.54; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.86).91 For etidronate, still a mandated first-line option in many provinces, there are no data available to support its long-term use or to establish guidelines for drug holiday.

Conditions that might increase fracture risk, such as initiation of glucocorticoid therapy or increased risk of falls, necessitate reevaluation of the appropriateness of the drug holiday.

Reinitiating therapy following a drug holiday

When reinitiating therapy, the best approach might be to perform a full reassessment, as if that patient were previously untreated, using the 2010 Osteoporosis Canada guidelines for estimating future 10-year fracture risk.8 Estimated fracture and fall risk, remaining life expectancy, and response and tolerance to previous therapies should be considered when deciding on the best course of action. There are no data to help determine which therapy would be best to employ after a drug holiday.

If this reassessment leads to a decision to extend the drug holiday, patients should be followed with hip BMD measurement at intervals of initially 2 to 3 years and perhaps longer.

Response to clinical vignette

If Mrs Jones discontinued her bisphosphonate, she would experience a gradual decline in pharmacologic benefit from the already-bound bisphosphonate and an increase in fracture risk. Because Mrs Jones has prevalent vertebral fractures, she is at high risk of future fractures and should not be offered a drug holiday. Mrs Jones is at a very low risk of suffering from ONJ, AFF, AF, or esophageal cancer with continued bisphosphonate therapy; thus, the beneficial fracture protection afforded by the bisphosphonate would far outweigh the potential risk of any of these rare adverse events.

Because Mrs Jones’ creatinine clearance is 45 mL/min, there are no renal concerns related to her bisphosphonate use. However, if she did have seriously compromised renal function, then the use of oral bisphosphonates might also be contraindicated and their use should be discussed with a specialist.

Conclusion

While aminobisphosphonates are first-line therapy for patients at high risk of fracture, there are some rare, but serious, adverse events that have been associated with their use, most notably ONJ and AFF. When bisphosphonates are prescribed for patients at high risk of future fragility fractures, the antifracture benefits provided by bisphosphonates far outweigh their potential for harm. For patients persisting with bisphosphonate therapy for 3 to 5 years (zoledronic acid or alendronate), it is reasonable to reassess the need for ongoing therapy. For those who remain at high risk of fracture, ongoing therapy is recommended. For those who are at moderate or low risk of fracture with therapy, a drug holiday could be considered, recognizing that the optimal duration of drug interruption is unclear and that the appropriate agent with which to reinstitute therapy is also uncertain.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported and endorsed by Osteoporosis Canada.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

The absolute risk of bisphosphonate-associated atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fracture is between 2 and 78 cases per 100 000 person-years. The absolute risk of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw is approximately 1 case per 100 000 person-years when bisphosphonates are administered for osteoporosis treatment.

Bisphosphonate drug holidays can be considered for patients who have persisted with bisphosphonate therapy for 3 to 5 years and for those at low risk of fracture.

High-risk patients with osteoporotic bone mineral density or history of fragility fracture (including prevalent vertebral fracture) are not candidates for bisphosphonate holiday.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’avril 2014 à la page e197.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the design and conduct of this review and contributed to, edited, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

Dr Brown has received research grants, consulting fees, or speakers’ bureau fees from Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Takeda, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Morin has received research grants or consultant or speaker fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Novartis. Dr Leslie has received speaker’s fees from, received research grants from, or participated on advisory boards for Amgen, Genzyme, and Novartis. Dr Papaioannou has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Cheung has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Davison has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Goltzman has been a consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Novartis. Dr Hanley has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, NPS Pharmaceuticals, Servier, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Hodsman has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Novartis Canada, Shire Pharmaceuticals Canada, and Warner Chilcott Canada. Dr Josse has been a speaker or consultant for Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Jovaisas has been a speaker and consultant for Novartis. Dr Juby has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Kaiser has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Karaplis has been a speaker and consultant for Novartis. Dr Kendler has received research grants from, been a speaker or consultant for, or participated on advisory boards for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Pfizer, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Khan has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Merck, and NPS Pharmaceuticals. Dr Olszynski has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Ste-Marie has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, and Warner Chilcott. Dr Adachi has been a speaker or consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Warner Chilcott.

References

- 1.Davison KS, Siminoski K, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, Goltzman D, Hodsman A, et al. Bone strength: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;36(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papaioannou A, Wiktorowicz ME, Adachi JD, Goeree R, Papadimitropoulos E, Bedard M. Mortality, independence in living, and re-fracture one year following hip fracture in Canadians. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2000;22(8):591–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Parkinson W, Stephenson G, Bedard M. Lengthy hospitalization associated with vertebral fractures despite control for comorbid conditions. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(10):870–4. doi: 10.1007/s001980170039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salaffi F, Cimmino MA, Malavolta N, Carotti M, Di Matteo L, Scendoni P, et al. The burden of prevalent fractures on health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: the IMOF study. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(7):1551–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pande I, Scott DL, O’Neill TW, Pritchard C, Woolf AD, Davis MJ. Quality of life, morbidity, and mortality after low trauma hip fracture in men. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(1):87–92. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM, Akhtar-Danesh N, Anastassiades T, Pickard L, et al. Relation between fractures and mortality: results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. CMAJ. 2009;181(5):265–71. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colon-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, et al. Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(6):380–90. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1864–73. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beaupre LA, Morrish DW, Hanley DA, Maksymowych WP, Bell NR, Juby AG, et al. Oral bisphosphonates are associated with reduced mortality after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(3):983–91. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook PN, Cameron ID, Chen JS, March LM, Simpson JM, Cumming RG, et al. Oral bisphosphonates are associated with reduced mortality in frail older people: a prospective five-year study. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(9):2551–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, Adachi JD, Pieper CF, Mautalen C, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799–809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348(9041):1535–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280(24):2077–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, McKeever CD, Hangartner T, Keller M, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282(14):1344–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(5):527–34. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heckbert SR, Li G, Cummings SR, Smith NL, Psaty BM. Use of alendronate and risk of incident atrial fibrillation in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(8):826–31. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.8.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wysowski DK. Reports of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:89–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0808738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak CY. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1294–301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odvina CV, Levy S, Rao S, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS. Unusual mid-shaft fractures during long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(2):161–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie WD, Berger C, Langsetmo L, Lix LM, Adachi JD, Hanley DA, et al. Construction and validation of a simplified fracture risk assessment tool for Canadian women and men: results from the CaMos and Manitoba cohorts. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(6):1873–83. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1445-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell RG, Watts NB, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ. Mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: similarities and differences and their potential influence on clinical efficacy. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(6):733–59. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cremers SC, Pillai G, Papapoulos SE. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of bisphosphonates: use for optimisation of intermittent therapy for osteoporosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(6):551–70. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenspan SL, Emkey RD, Bone HG, Weiss SR, Bell NH, Downs RW, et al. Significant differential effects of alendronate, estrogen, or combination therapy on the rate of bone loss after discontinuation of treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):875–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller PD, Bolognese MA, Lewiecki EM, McClung MR, Ding B, Austin M, et al. Effect of denosumab on bone density and turnover in postmenopausal women with low bone mass after long-term continued, discontinued, and restarting of therapy: a randomized blinded phase 2 clinical trial. Bone. 2008;43(2):222–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neele SJ, Evertz R, De Valk-De Roo G, Roos JC, Netelenbos JC. Effect of 1 year of discontinuation of raloxifene or estrogen therapy on bone mineral density after 5 years of treatment in healthy postmenopausal women. Bone. 2002;30(4):599–603. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dowd R, Recker RR, Heaney RP. Study subjects and ordinary patients. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(6):533–6. doi: 10.1007/s001980070097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siris ES, Pasquale MK, Wang Y, Watts NB. Estimating bisphosphonate use and fracture reduction among US women aged 45 years and older, 2001-2008. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(1):3–11. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, Dempster DW, Ebeling PR, Felsenberg D, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(10):1479–91. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compston J. Pathophysiology of atypical femoral fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(12):2951–61. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1804-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, Steger GG, Tonkin K, de Boer RH, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5132–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan AA, Rios LP, Sandor GK, Khan N, Peters E, Rahman MO, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw in Ontario: a survey of oral and maxillofacial surgeons. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1396–402. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malden N, Lopes V. An epidemiological study of alendronate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. A case series from the south-east of Scotland with attention given to case definition and prevalence. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30(2):171–82. doi: 10.1007/s00774-011-0299-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguirre JI, Akhter MP, Kimmel DB, Pingel JE, Williams A, Jorgensen M, et al. Oncologic doses of zoledronic acid induce osteonecrosis of the jaw-like lesions in rice rats (oryzomys palustris) with periodontitis. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2130–43. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shane E, Burr D, Ebeling PR, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(11):2267–94. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neviaser AS, Lane JM, Lenart BA, Edobor-Osula F, Lorich DG. Low-energy femoral shaft fractures associated with alendronate use. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:346–50. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318172841c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dell R, Greene D, Ott SM, Silverman S, Eisemon E, Funahashi T, et al. A retrospective analysis of all atypical femur fractures seen in a large California HMO from the years 2007 to 2009 [abstract] J Bone Miner Res. 2010:25. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Dekkers OM, Ramautar SR, Dijkstra S, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures and bisphosphonate therapy: a cohort study of patients with femoral fracture with radiographic adjudication of fracture site and features. Bone. 2011;48:966–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armamento-Villareal R, Napoli N, Diemer K, Watkins M, Civitelli R, Teitelbaum S, et al. Bone turnover in bone biopsies of patients with low-energy cortical fractures receiving bisphosphonates: a case series. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;85(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goh SK, Yang KY, Koh JS, Wong MK, Chua SY, Chua DT, et al. Subtrochanteric insufficiency fractures in patients on alendronate therapy: a caution. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(3):349–53. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ing-Lorenzini K, Desmeules J, Plachta O, Suva D, Dayer P, Peter R. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with the long-term use of bisphosphonates: a case series from a Swiss university hospital. Drug Saf. 2009;32:775–85. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwek EB, Goh SK, Koh JS, Png MA, Howe TS. An emerging pattern of subtrochanteric stress fractures: a long-term complication of alendronate therapy? Injury. 2008;39:224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visekruna M, Wilson D, McKiernan FE. Severely suppressed bone turnover and atypical skeletal fragility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2948–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edwards MH, McCrae FC, Young-Min SA. Alendronate-related femoral diaphysis fracture—what should be done to predict and prevent subsequent fracture of the contralateral side? Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:701–3. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giusti A, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. Atypical fractures of the femur and bisphosphonate therapy: a systematic review of case/case series studies. Bone. 2010;47:169–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nieves JW, Bilezikian JP, Lane JM, Einhorn TA, Wang Y, Steinbuch M, et al. Fragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristics. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(3):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0962-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures in patients treated with alendronate: a register-based national cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1095–102. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salminen S, Pihlajamaki H, Avikainen V, Kyro A, Bostman O. Specific features associated with femoral shaft fractures caused by low-energy trauma. J Trauma. 1997;43:117–22. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss RJ, Montgomery SM, Al Dabbagh Z, Jansson KA. National data of 6409 Swedish inpatients with femoral shaft fractures: stable incidence between 1998 and 2004. Injury. 2009;40(3):304–8. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1555–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bone HG, Hosking D, Devogelaer JP, Tucci JR, Emkey RD, Tonino RP, et al. Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Levis S, Quandt SA, et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ensrud KE, Barrett-Connor EL, Schwartz A, Santora AC, Bauer DC, Suryawanshi S, et al. Randomized trial of effect of alendronate continuation versus discontinuation in women with low BMD: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(8):1259–69. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mellström DD, Sorensen OH, Goemaere S, Roux C, Johnson TD, Chines AA. Seven years of treatment with risedronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75(6):462–8. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, Bucci-Rechtweg C, Cauley JA, Cosman F, et al. The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT) J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(2):243–54. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, Palermo L, Eastell R, Bucci-Rechtweg C, et al. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1761–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Compston JE. Bisphosphonates and atypical femoral fractures: a time for reflection. Maturitas. 2010;65:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abrahamsen B. Adverse effects of bisphosphonates. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;86:421–35. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shane E. Evolving data about subtrochanteric fractures and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1825–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1003064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nieves JW, Cosman F. Atypical subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures and possible association with bisphosphonates. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2010;8:34–9. doi: 10.1007/s11914-010-0007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abrahamsen B, Eiken P, Eastell R. Cumulative alendronate dose and the long-term absolute risk of subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures: a register-based national cohort analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5258–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lenart BA, Neviaser AS, Lyman S, Chang CC, Edobor-Osula F, Steele B, et al. Association of low-energy femoral fractures with prolonged bisphosphonate use: a case control study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20(8):1353–62. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0805-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Girgis CM, Seibel MJ. Guilt by association? Examining the role of bisphosphonate therapy in the development of atypical femur fractures. Bone. 2011;48:963–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Girgis CM, Seibel MJ. Atypical femur fractures: a complication of prolonged bisphosphonate therapy? Med J Aust. 2010;193:196–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumm DA, Rack C, Rutt J. Subtrochanteric stress fracture of the femur following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:580–3. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niimi R, Hasegawa M, Sudo A, Uchida A. Unilateral stress fracture of the femoral shaft combined with contralateral insufficiency fracture of the femoral shaft after bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13:572–5. doi: 10.1007/s00776-008-1262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schilcher J, Aspenberg P. Incidence of stress fractures of the femoral shaft in women treated with bisphosphonate. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:413–5. doi: 10.3109/17453670903139914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang KH, Park SY, Park SW, Lee SH, Han SB, Jung WK, et al. Insufficient bilateral femoral subtrochanteric fractures in a patient receiving imatinib mesylate. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28(6):713–8. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bunning RD, Rentfro RJ, Jelinek JS. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use in a rehabilitation setting: a case series. PM R. 2010;2(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Hawker GA, Gunraj N, Austin PC, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305(8):783–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Z, Bhattacharyya T. Trends in incidence of subtrochanteric fragility fractures and bisphosphonate use among the US elderly, 1996–2007. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:553–60. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hopkins RB, Pullenayegum E, Goeree R, Adachi JD, Papaioannou A, Leslie WD, et al. Estimation of the lifetime risk of hip fracture for women and men in Canada. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(3):921–7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1652-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(3):197–213. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-3-200802050-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Health Canada. Bisphosphonate osteoporosis drugs (Aclasta, Actonel, Didrocal, Fosamax, Fosavance): small but increased risk of unusual thigh bone fractures. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2011. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/media/advisories-avis/_2011/2011_172-eng.php. Accessed 2012 Feb 7. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Statistics Canada. Homicide offences, number and rate, by province and territory. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Transport Canada. 2007 casualty rates. Ottawa, ON: Transport Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sørensen HT, Christensen S, Mehnert F, Pedersen L, Chapurlat RD, Cummings SR, et al. Use of bisphosphonates among women and risk of atrial fibrillation and flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2008;336(7648):813–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39507.551644.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vestergaard P, Schwartz K, Pinholt EM, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Risk of atrial fibrillation associated with use of bisphosphonates and other drugs against osteoporosis: a cohort study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;86:335–42. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pazianas M, Cooper C, Wang Y, Lange JL, Russell RG. Atrial fibrillation and the use of oral bisphosphonates. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:131–44. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S17899. Epub 2011 Mar 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barrett-Connor E, Swern AS, Hustad CM, Bone HG, Liberman UA, Papapoulos S, et al. Alendronate and atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):233–45. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rhee CW, Lee J, Oh S, Choi NK, Park BJ. Use of bisphosphonate and risk of atrial fibrillation in older women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:247–54. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1608-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.US Food Drug Administration . FDA Drug Safety Communication: safety update for osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates, and atypical fractures. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2010. Available from: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm229009.htm. Accessed 2012 Feb 10. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Green J, Czanner G, Reeves G, Watson J, Wise L, Beral V. Oral bisphosphonates and risk of cancer of oesophagus, stomach, and colorectum: case-control analysis within a UK primary care cohort. BMJ. 2010;34:c4444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cardwell CR, Abnet CC, Cantwell MM, Murray LJ. Exposure to oral bisphosphonates and risk of esophageal cancer. JAMA. 2010;304:657–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dixon WG, Solomon DH. Bisphosphonates and esophageal cancer—a pathway through the confusion. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:369–72. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abrahamsen B, Pazianas M, Eiken P, Russell RG, Eastell R. Esophageal and gastric cancer incidence and mortality in alendronate users. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:679–86. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.US Food Drug Administration . FDA Drug Safety Communication: new contraindication and updated warning on kidney impairment for Reclast (zoledronic acid) Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2011. Available from: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm270199.htm. Accessed 2012 Feb 9. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis— where do we go from here? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2048–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watts NB, Chines A, Olszynski WP, McKeever CD, McClung MR, Zhou X, et al. Fracture risk remains reduced one year after discontinuation of risedronate. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(3):365–72. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seeman E. To stop or not to stop, that is the question. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:187–95. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0813-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Delzell E, Saag KG. Risk of hip fracture after bisphosphonate discontinuation: implications for a drug holiday. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1613–20. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0604-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cosman F, Cauley J, Eastell R, Boonen S, Palermo L, Reid I, et al. Who is at highest risk for new vertebral fractures after 3 years of annual zoledronic acid and who should remain on treatment?. Paper presented at: American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Annual Meeting; 2011 Sep 19. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schwartz AV, Bauer DC, Cummings SR, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Palermo L, et al. Efficacy of continued alendronate for fractures in women with and without prevalent vertebral fracture: the FLEX trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(5):976–82. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Black DM, Bauer DC, Schwartz AV, Cummings SR, Rosen CJ. Continuing bisphosphonate treatment for osteoporosis—for whom and for how long? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2051–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]