In family medicine we need heart, as well as content knowledge, to work with and apply the beauty of patient-centred care.1 To recognize the beauty of patient-centred care, every clinician must keep an open mind, which includes remembering that patients and their families can learn with us or be our teachers and mentors regardless of their age, appearance, culture, or ethnicity.2–4 Thus, within our world of increasing cultural diversity, we must continue to build on the work of the CanMEDS–Family Medicine5 and the Triple C Competency-based Curriculum6 documents to develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required for patient-centred care within a cultural context. Further efforts should be focused on implementing objectives for culturally appropriate care, initiating strategies for integrating culturally appropriate care into the curriculum, and developing faculty capable of addressing culturally appropriate care at the local level.7

Defining the need

Why is there a need for patient-centred care within a cultural context? Canada is well known throughout the world for its cultural diversity and for providing an environment that supports newcomers from different cultures. These newcomers contribute to Canadian culture in many ways (eg, economically, culturally, through innovation).

Providing culturally appropriate care means that health care providers and the organizations for which they work are sensitive to cultural differences and tailor their approaches to meet the specific needs of patients and their families.8 To do this, health care providers need to better understand the many words that describe culture and the effects of culture on the people that they serve. As teachers, educators, and facilitators in family medicine, we need to ensure that undergraduates, residents, and faculty members facilitate culturally appropriate, patient-centred care1 in all situations, not just ones with which they are comfortable.

As the newcomer population in Canada continues to grow, it is increasingly important that resident education about culturally appropriate care reflects this changing demographic landscape.9 In the current context of postgraduate education and training, competencies around cultural sensitivity and the provision of culturally appropriate patient-centred care are listed under the communicator role.5 The newly developed Triple C Competency-based Curriculum6 defines and emphasizes the importance of competence specifically in developing patient-centred, trusting relationships with patients, families, and communities. As part of the communicator role,5 the assessment of cultural competence has begun to be developed within the theme of cultural and age appropriateness (ie, adapting communication to the individual patient for reasons such as culture, age, and disability)7; however, Laughlin et al have gone on to indicate that observable behaviour by colleagues has yet to be developed and might be better assessed in the context of communication with patients and families.7

Culturally appropriate care

Culture is defined as a set of similar ideas and practices shared by a group of people about appropriate behaviour and values.8 Frequently, people who share these basic cultural attributes tend to act, eat, and dress, as well as think about life, in similar ways.10 Cultural awareness refers to the recognition that not all people are from the same cultural background.10 It also refers to recognizing that people have different behaviour, values, and approaches to life.10 Cultural sensitivity “begins with recognition that there are differences between cultures. These differences are reflected in the ways that different groups communicate and relate to one another, and they carry over into interactions with health care providers.”11

Cultural competency is “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables the system or professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.”12 It is a process and not an outcome.12 The Nova Scotia Department of Health has identified 8 activities related to cultural competence in which all primary health care providers, regardless of their own cultural backgrounds, should engage (Box 1).12

Box 1. Eight activities related to cultural competence.

Nova Scotia Department of Health has identified these 8 activities that primary health care providers should engage in:

|

Data from Nova Scotia Department of Health.12

Reflective practice

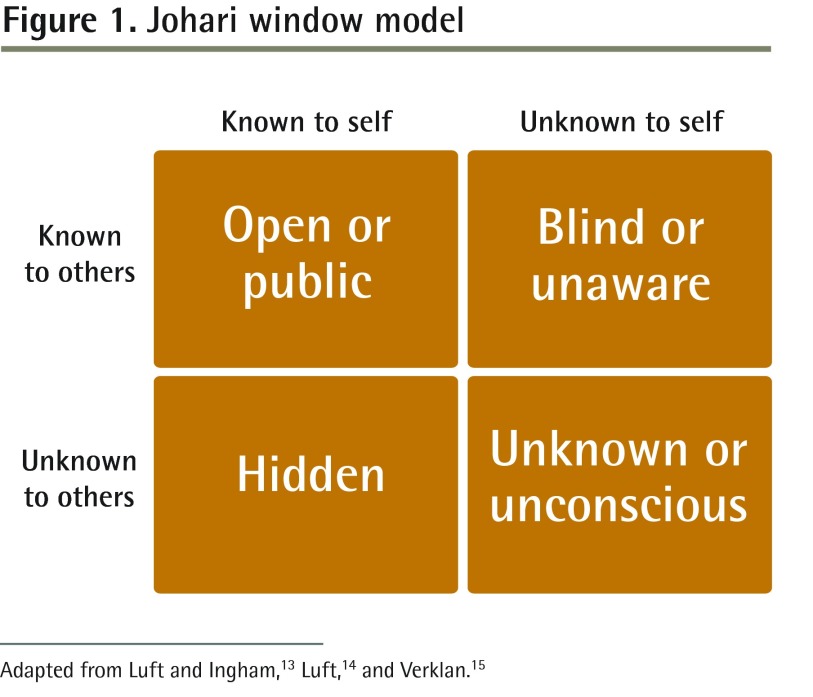

The Johari window model (Figure 1)13–15 is a tool that can help us better understand how we communicate with others. When it is applied to personal practice, it provides a framework or context from which to reflect on interactions with patients. As a tool, it can be used to clarify self-awareness and mutual understanding between individual members of a group and with members of other groups.

Figure 1.

Johari window model

When taking a closer look at the 8 activities of cultural competence of the Nova Scotia Department of Health (Box 1)12 and the Johari window model, a theme evolves: the need for reflective practice. Practice advice and general principles related to reflective practice have been developed based on the 3-stage cycle of plan, do, and review.16 The following are the general principles.16,17

Know when and where reflective practice is appropriate. If we as clinicians do not first identify areas of insufficient competence, it is not possible to take steps to improve practice.

Reflect on the situation, the actions taken, and why. This includes personal thoughts and feelings at the time; biases, values, and assumptions; patients’ perspectives; and past experiences that might have led to a specific action or inaction.

Seek out sources for feedback (eg, a literature review, consultation with colleagues).

Reflect on lessons learned.

Create an action plan to modify actions and improve outcomes.

Take action on an established plan and continue to monitor change over time.

It is important to emphasize that effective reflection goes beyond simply thinking about a particular event or circumstance to creating an action plan designed to result in the desired change. It also includes monitoring the action plan over time. Thus, a clinician who engages in reflective practice will be able to recognize areas in practice, teaching, or research that require improvement.

Here we present a case for reflective practice.

I went to visit Mr A. in hospital to see how he and his wife were doing, as they have 2 young children to care for. I always thought of Mr A. as a jolly man, but seeing him lying in a hospital bed crying in pain did not match with the person that I knew. His wife and another family member were at his side. He had been assessed by the attending physician and was told that he had a low pain tolerance and that it was probably just “muscle pain.” Mr A. had expected the attending physician to order some medication to relieve the pain, get him to stand up, and send him home as soon as possible.

Mr A.’s wife, a strong, enthusiastic, and well educated woman, sat tearfully beside her husband’s bed. On further discussion, I learned that Mr A., who continued to cry in agony from the pain, had not been invited or asked to tell his story by the attending physician, which would have allowed Mr A. to elaborate on his history and the reasons he had presented for care. The attending physician did not make eye contact with Mr A.’s wife and did not speak to her—actions that might have helped to provide a better understanding of Mr A.’s condition.

While chatting with the patient in the next bed, Mr A. and his wife learned that he and his family were very impressed with the care provided by the attending physician; how the physician had made sure that the patient and the family clearly understood the diagnosis; and how he had explained to them about what would happen next.

Mr A. and his wife were surprised at how different that same attending physician was in communicating and engaging with that patient and his family about the disease process and prognosis; how differently the same physician provided care to both patients.

The following questions arise from the case presented.

Was the physician aware that he treated these 2 patients and their families differently?

What might be some of the reasons that the physician treated these 2 patients and their families differently?

If the physician and Mr A. were from different cultures, was the physician uncomfortable treating patients and their families who were from a different culture?

Did the physician’s cultural background or ethnicity affect patient-centred care?

Conclusion

Although scenarios such as the one above should be avoided, they are not uncommon. Thus, that cultural competencies are addressed in foundational documents5,6 is promising; however, work in the areas of implementation and faculty development will be necessary to ensure that the beauty of applying patient-centred care within a cultural context is integrated into daily practice.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article se trouve aussi en français à la page 316.

Competing interests

None declared

The opinions expressed in commentaries are those of the authors. Publication does not imply endorsement by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.

References

- 1.McWhinney I. Why we need a new clinical method. In: Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR, editors. Patient-centered medicine. Transforming the clinical method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mezirow J. Fostering critical reflection in adulthood. A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mezirow J. Learning as transformation. Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith G, Hughes J, Greenhalgh T. Patients as teachers and mentors. In: Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Woodard R, editors. User involvement in health care. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.College of Family Physicians of Canada, Working Group on Curriculum Review . CanMEDS–Family Medicine. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2009. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Education/CanMeds%20FM%20Eng.pdf. Accessed 2011 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tannenbaum D, Konkin J, Parsons E, Saucier D, Shaw L, Walsh A, et al. Report of the Working Group on Postgraduate Curriculum Review—part 1. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2011. Triple C competency-based curriculum. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Education/_PDFs/WGCR_TripleC_Report_English_Final_18Mar11.pdf. Accessed 2011 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laughlin T, Wetmore S, Allen T, Brailovsky C, Crichton T, Bethune C, et al. Defining competency-based evaluation objectives in family medicine. Communication skills. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e217–24. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/58/4/e217.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2014 Feb 10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yehieli M, Grey MA. Health matters. A pocket guide for working with diverse cultures and underserved populations. Boston, MA: Intercultural Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kymlicka W. The current state of multiculturalism in Canada and research themes on Canadian multiculturalism 2008–2010. Ottawa, ON: Citizenship and Immigration Canada; 2010. Available from: www.cic.gc.ca/english/pdf/pub/multi-state.pdf. Accessed 2014 Feb 21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Canada . Reaching out: a guide to communicating with aboriginal seniors. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 1998. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H88-3-30-2001/pdfs/com/reach_e.pdf. Accessed 2014 Feb 21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krapp K, editor. Gale encyclopedia of nursing & allied health. Farmington Hill, MI: Gale Group; 2002. Cultural sensitivity; pp. 620–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nova Scotia Department of Health . A cultural competence guide for primary health care professionals in Nova Scotia. Halifax, NS: Nova Scotia Department of Health; 2005. Available from: www.healthteamnovascotia.ca/cultural_competence/Cultural_Competence_guide_for_Primary_Health_Care_Professionals.pdf. Accessed 2014 Feb 21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luft J, Ingham H. Proceedings of the Western Training Laboratory in Group Development. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles; 1955. The Johari window, a graphic model of interpersonal awareness. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luft J. Of human interaction. Palo Alto, CA: National Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verklan MT. Johari Window: a model for communicating to each other. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2007;21(2):173–4. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000270636.34982.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE guide no. 44. Med Teach. 2009;31(8):685–95. doi: 10.1080/01421590903050374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aronson L. Twelve tips for teaching reflection at all levels of medical education. Med Teach. 2011;33(3):200–5. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.507714. Epub 2010 Sep 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]