Abstract

Andropause or late-onset hypogonadism is a common disorder which increases in prevalence with advancing age. Diagnosis of late-onset of hypogonadism is based on presence of symptoms suggestive of testosterone deficiency - prominent among them are sexual symptoms like loss of libido, morning penile erection and erectile dysfunction; and demonstration of low testosterone levels. Adequate therapeutic modalities are currently available, but disparate results of clinical trial suggest further evaluation of complex interaction between androgen deficiency and ageing. Before initiating therapy benefits and risk should be discussed with patients and in case of poor response, alternative cause should be investigated.

Keywords: Androgen deficiency in ageing male, late onset hypogonadism, testosterone therapy in ageing male

INTRODUCTION

“Andras” in Greek means human male and “pause” in Greek a cessation; so literally “andropause” is defined as a syndrome associated with a decrease in sexual satisfaction or a decline in a feeling of general well-being with low levels of testosterone in older man. In 1946, Werner published a landmark paper in JAMA entitled, “The male climacteric” characterized by nervousness, reduced potency, decreased libido, irritability, fatigue, depression, memory problems, sleep disturbances, and hot flushes. Hypogonadism is broad scientific term and it refers to a clinical syndrome caused by androgen deficiency, which may adversely affect multiple organ functions and quality of life.

In contrast to menopause which is universal, well-characterized timed process associated with absolute gonadal failure, andropause is characterized by insidious onset and slow progression. Many names were given to this process like male menopause, male climacteric, androclise, androgen decline in ageing male (ADAM), ageing male syndrome, and of late, and late onset hypogonadism (LOH). True andropause exists only in those men who have lost testicular function, due to diseases or accidents, or in those with advanced prostate cancer subjected to surgical or medical castration.

Testosterone levels decline with aging at the rate of 1% per year and this decline is more pronounced in free testosterone levels because of alterations in sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG).[1] The rate of decline in testosterone levels varies in different individuals and is affected by chronic disease, such as obesity, illness, serious emotional stress, and medications; and this decline can be decelerated by management of health and lifestyle factors.[2] Amongst obesity parameters, waist circumference is one of potentially modifiable risk factor for low testosterone and symptomatic androgen deficiency.

Testosterone threshold at which symptoms become manifest show subject-to-subject variation and many men are not symptomatic, although having low levels of testosterone. Declining testosterone and other anabolic hormones in men from the mid-30s onward may influence the aging-related deteriorations in body function (e.g., frailty, obesity, osteopenia, cognitive decline, and erectile failure) and testosterone insufficiency in older men is found to be associated with increased risk of death over the following 20 years independent of multiple risk factors and several preexisting health problems. But this association could not be confirmed in the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) or the New Mexico Aging Study.

For years, there has been major disagreement on how to define the syndrome for clinical and epidemiologic research purposes. Investigators have generally taken two approaches; one is purely statistical (lower 2.5th percentile of testosterone adult value), whereas the other is clinical (symptom questionnaire like Androgen Deficiency in the Aging Male. But problem is compounded by the fact that men with low testosterone levels may not exhibit clinically significant symptomatology[3,4] and many of the symptoms are nonspecific.

LOH, a clinical and biochemical syndrome is a common disorder associated with advancing age and characterized by symptoms and a deficiency in serum testosterone levels (below the young healthy adult male reference range), but is often underdiagnosed and often untreated. Reported prevalence of hypogonadism was 3.1–7.0% in men aged 30–69 years, and 18.4% in men older than 70 years and prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men 30–79 years of age is 5.6% and it increases substantially with age.[5] European Male Aging Study (EMAS) data reported prevalence of 2.1% as assessed by low testosterone and presence of three sexual symptoms.[6] Furthermore, it has been estimated that only 5–35% of hypogonadal males actually receive treatment for their condition.

DIAGNOSIS OF LOH

At present diagnosis of LOH requires the presence of symptoms and signs suggestive of testosterone deficiency. The symptom most associated with hypogonadism is low libido. Other manifestations of hypogonadism include: erectile dysfunction, decreased muscle mass and strength, increased body fat, decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, and decreased vitality and depressed mood. None of these symptoms are specific to the low androgen state, but may raise suspicion of testosterone deficiency. One or more of these symptoms must be corroborated with a low serum testosterone level.

Depression, hypothyroidism, chronic alcoholism, and use of medications such as corticosteroids, cimetidine, spironolactone, digoxin, opioid analgesics, antidepressants, and antifungal agents should be excluded before making a diagnosis of LOH. Similarly, diagnosis of LOH should not be made during acute illness which decreases testosterone levels temporarily.[7]

Results from EMAS proposed, that the presence of three sexual symptoms (decreased libido, morning erections, and erectile dysfunction) combined with a total testosterone level of less than 11 nmol/l and a free testosterone level of less than 220 pmol/l, can be considered the minimum criteria for the diagnosis of LOH in aging men.[6]

Questionnaires such as Aging Male Symptom (AMS) Score and ADAM are not recommended for the diagnosis of hypogonadism because of low specificity (30 and 39%, respectively).[8] Risk factors for LOH may include chronic illnesses including diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive lung disease, inflammatory arthritic disease, renal disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and hemochromatosis.[8]

Laboratory diagnosis

Serum testosterone levels vary significantly as a result of circadian and circannual rhythms, episodic secretion, and measurement variations. In the presence of symptoms a serum sample for total testosterone determination should be obtained between 0700 and 1100 h.[9]

Serum total testosterone concentration represents the sum of unbound and protein-bound testosterone in circulation. Most of the circulating testosterone is bound to SHBG and to albumin; only 0.5–3% of circulating testosterone is unbound or “free.” The term “bioavailable testosterone” refers to unbound testosterone plus testosterone bound loosely to albumin; this term reflects the hypothesis that in addition to the unbound testosterone, albumin-bound testosterone is readily dissociable and thus bioavailable.

Total testosterone concentrations are also influenced by alterations in SHBG concentrations so it is important to confirm low testosterone concentrations in men with an initial testosterone level in the mildly hypogonadal range, because 30% of such men may have a normal testosterone level on repeat measurement; also, 15% of healthy young men may have a testosterone level below the normal range in a 24-h period.

Free or bioavailable testosterone concentrations should be measured when total testosterone concentrations are close to the lower limit of the normal range and when altered SHBG levels are suspected, for example, decreased SHBG in moderate obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic illness, use of glucocorticoids, hypothyroidism or increased SHBG in aging, hepatic cirrhosis, hepatitis, hyperthyroidism, use of estrogens, and HIV disease.

The clinicians should use the lower limit of normal range for healthy young men established in their laboratory. For most symptoms, the average testosterone threshold corresponded to the lower limit of the normal range for young men, that is, ~300 ng/dl (10.4 nmol/l) with a greater likelihood of having symptoms below this threshold than above it.[10]

There is general agreement amongst various professional bodies that the total testosterone level above 12 nmol/l (350 ng/dl) does not require substitution. Similarly, based on the data of younger men, there is consensus that patients with serum total testosterone levels below 8 nmol/l (230 ng/dl) will usually benefit from testosterone treatment. If the serum total testosterone level is between 8 and 12 nmol/l (230 and 350 ng/dl), repeating the measurement of total testosterone with SHBG to calculate free testosterone or bioavailable testosterone will benefit the patient.[7]

Current immunometric methods for the measurement of testosterone can distinguish between hypogonadism and normal adult men. Equilibrium dialysis and sulfate precipitation are the gold standard for free testosterone and bioavailable testosterone measurement. Both gold standards techniques are not available routinely so calculated values are preferred. Calculated free testosterone correlates well with free testosterone by equilibrium dialysis. Threshold values for bioavailable testosterone depend on the method used and are not generally available.[11] Salivary testosterone has also been shown to be a reliable substitute for free testosterone measurements, but cannot be recommended for general use at this time, since the methodology has not been standardized and adult male ranges are not available in most hospital or reference laboratories.[12]

Next step is to determine whether a patient has primary or secondary hypogonadism by measuring serum LH and FSH. Elevated LH and FSH suggest primary hypogonadism, whereas low or lower-than-normal LH and FSH levels suggest secondary hypogonadism. Normal LH and FSH in the face of low testosterone suggest primary defect in the hypothalamus and/or the pituitary. Unless fertility is an issue, estimation of LH alone is sufficient. If the total testosterone concentration is less than 150 ng/dl, pituitary imaging, and prolactin levels are recommended to evaluate for structural lesions in the hypothalamus-pituitary region.[13,14]

Alterations in other endocrine systems occur in association with aging (i.e., estradiol, growth hormone (GH), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)), but the significance of these changes is not well-understood. Determinations of estradiol, thyroid hormones, cortisol, DHEA, DHEA sulfate (DHEA-S), melatonin, GH, and insulin-like growth factor-1 are not indicated unless other endocrine disorders are suspected based on the clinical signs and symptoms of the patient.

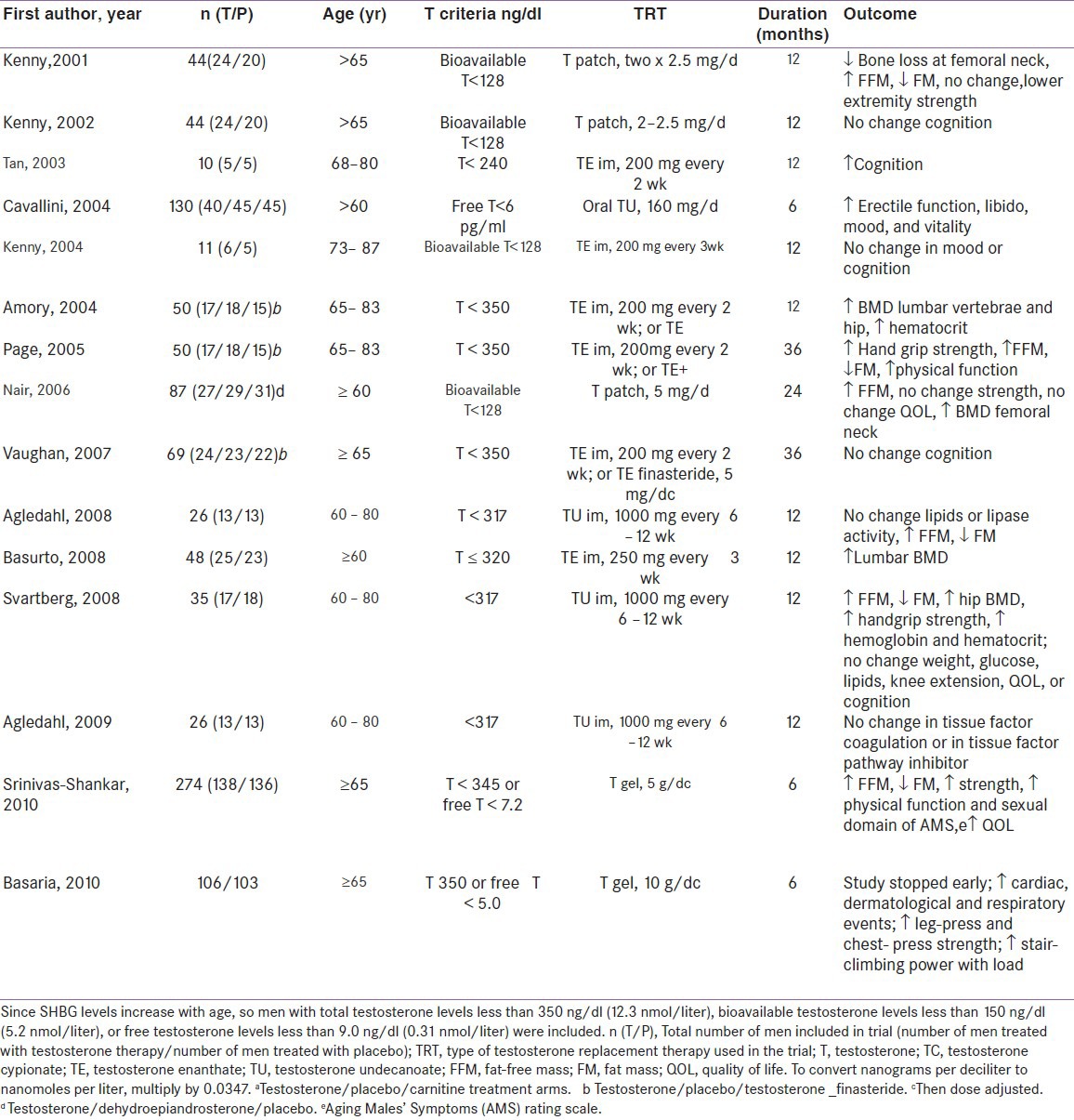

POTENTIAL EFFECTS/BENEFITS OF TESTOSTERONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY Table 1[15]

Table 1.

Testosterone replacement RPCTs in men age 60 yrs or older

Improved body composition and muscle mass and strength

A meta-analysis concluded that testosterone therapy decreased fat mass and increased lean body mass with no overall change in body weight. These changes were observed both in men with baseline testosterone levels that averaged less than 300 ng/dl, and in a larger number of studies in which the average baseline was considerably greater than 300 ng/dl. The effects of testosterone on muscle strength were heterogeneous, showing a tendency toward improvement only with leg/knee extension and handgrip of the dominant arm.[16] Effects on physical functions also have been inconsistent, and few trials have included men with functional limitations. Secondary benefits of these changes of body composition on strength, muscle function, and metabolic and cardiovascular dysfunction are suggested by available data but require confirmation by large-scale studies.[17]

Bone density and fracture rate

Osteopenia, osteoporosis, and fracture prevalence rates are greater in hypogonadal younger and older men.[18] Osteoporosis is twice more common in hypogonadal men as compared to eugonadal men (6 vs 2.8%). Bone density in hypogonadal men of all age increases under testosterone substitution.[19] Testosterone produces this effect by increasing osteoblastic activity and through aromatization into estrogen reducing osteoclastic activity. The pooled data from a meta-analysis suggest a beneficial effect on lumber spine density and equivocal findings on femoral neck BMD.[20] Fracture data are not yet available and thus the long-term benefit of testosterone requires further investigation. Trials of intramuscular testosterone reported significantly larger effects on lumber bone density than trials of transdermal testosterone, particularly among patients receiving long-term glucocorticoids. Assessment of bone density at 2-year intervals is advisable in hypogonadal men and serum testosterone measurements should be obtained in all men with osteopenia.

Testosterone and sexual function

Serum free testosterone has been found to be significantly correlated with libido,[21] erectile, and orgasmic function domains on International Index of Erectile Function questionnaire.

Men with erectile dysfunction and/or diminished libido and documented testosterone deficiency are candidates for testosterone therapy. An inadequate response to testosterone treatment requires reassessment of the causal mechanisms responsible for the erectile dysfunction. In the presence of a clinical picture of testosterone deficiency and borderline serum testosterone levels, a short (e.g., 3 months) therapeutic trial may be justified. An absence of response calls for discontinuation of testosterone administration. A satisfactory response might be placebo generated, so that continued assessment is advisable before long-term treatment is recommended. There is evidence suggesting therapeutic synergism with combined use of testosterone and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in hypogonadal or borderline eugonadal men. These observations are still preliminary and require additional study. However, the combination treatment should be considered in hypogonadal patients with erectile dysfunction failing to respond to either treatment alone. It is unclear whether men with hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction should be treated initially with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE-5-I), testosterone, or the combination of the two.[22]

Several randomized, placebo-controlled trials have suggested that testosterone treatment moderately improved the number of nocturnal erections, sexual thoughts and motivation, number of successful intercourses, scores of erection function, and overall sexual satisfaction. But consistent effect has been noted on libido than on erection function.

TESTOSTERONE AND OBESITY, METABOLIC SYNDROME, AND TYPE 2 DIABETES

Testosterone has a positive effect on reducing the risk factors for metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Low endogenous testosterone concentration is related to mortality due to cardiovascular disease and all causes. Many of the components of the metabolic syndrome (obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired glucose regulation, and insulin resistance) are also present in hypogonadal men. Numerous epidemiological studies have established a close relationship between obesity and low serum testosterone levels in healthy men. Twenty to 64% of obese men have a low serum total or free testosterone levels and 33–50% type 2 diabetes mellitus patients have low plasma testosterone in association with low gonadotropins (borderline and overt hypogonadism).[23,24] There is no relationship between level of glycemia and serum testosterone concentration. In view of high prevalence in diabetics, serum testosterone should be measured in diabetic men with symptoms suggestive of testosterone deficiency.

Low total testosterone and SHBG along with androgen deficiency are associated with increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome over time particularly in non-overweight, middle-aged men (body mass index (BMI) < 25). These results suggest that low SHBG and/or androgen deficiency may provide early warning signs for cardiovascular risk and an opportunity for early intervention in nonobese men.[25]

The effects of testosterone administration on glycemic control in diabetes mellitus as assessed by HbA1c and homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) assessment of insulin resistance, are much less certain.[26,27] It is premature to recommend testosterone treatment for the metabolic syndrome or diabetes mellitus in the absence of laboratory and other clinical evidence of hypogonadism.

The effect of androgen replacement in elderly men on low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) is controversial. In a meta-analysis of intramuscular testosterone esters and plasma lipids in hypogonadal men, a small, dose-dependent decrease was seen in total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol levels. Mechanism for this action was proposed to be the action of androgens on abdominal adiposity. But supraphysiological testosterone levels induce an increase in LDL-C and decrease of HDL-C levels and may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Testosterone treatment in elderly individuals with chronic heart failure might improve insulin sensitivity and various cardiorespiratory and muscular outcomes.[28] But no consistent relationship between coronary atherosclerosis and level of testosterone total or free has been observed in patients undergoing coronary angiography.

Improving anemia

Androgens stimulate erythropoiesis and increase reticulocyte count, hemoglobin, and bone marrow erythropoietic activity.[29] Testosterone deficiency causes 10–20% decrease in hemoglobin concentration. Testosterone increases renal production of erythropoietin and directly stimulates erythropoietic stem cells.

Cognitive function

Decrease in testosterone concentration may be associated with a decline in verbal and visual memory and visuospatial performance.[30] Till date trials in men to study this aspect (cognitive function and memory) are relatively small, were of short duration, and have shown mixed results. Lower free testosterone levels seems to be associated with poorer outcomes on measures of cognitive function, particularly in older men, and testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men may have some benefit for cognitive performance.

Mood, energy, and quality of life

Effects on mood have been described with testosterone therapy in replacement and supraphysiological doses. In a meta-analysis testosterone therapy was found to have beneficial effect on mood, especially in patients with hypogonadism and HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). However, the studies were of limited size and duration and discrepancy in results on mood may be explained by the genetic polymorphism in the androgen receptor, which defines a vulnerable group in whom depression is expressed when testosterone levels decrease below a particular threshold.

PROSTATE CANCER AND BENIGN PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA (BPH)

Presently there is no conclusive evidence that testosterone treatment increases the risk of prostate cancer or BPH. There is also no evidence that testosterone treatment will convert subclinical prostate cancer to clinically detectable prostate cancer. However, there is unequivocal evidence that testosterone can stimulate growth and aggravate symptoms in men with locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer.[31,32] Currently, adequately powered and optimally designed long-term prostate disease data are not available to determine whether there is any additional risk from testosterone replacement. Hypogonadal older men should be counseled on the potential risks and benefits of testosterone replacement before treatment and carefully monitored for prostate safety during treatment.

Prior to therapy with testosterone, a man's risk of prostate cancer must be assessed using, as a minimum, digital rectal examination (DRE) and determination of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA). However, the pretreatment assessment can be improved by incorporating other risk predictors such as age, family history, and ethnicity/race. Several tools have been developed to assist the clinician in assessing prostate cancer risk (e.g., online prostate cancer risk calculator).[33] These tools have not been validated for patients with LOH. If the patient and physician feel that the risk is sufficiently high, further assessment may be desirable. However, pretreatment prostate ultrasound examinations or biopsies are not recommended as routine requirements. After initiation of testosterone treatment, patients should be monitored for prostate disease at 3–6 months, 12 months, and at least annually thereafter. Should the patient's prostate cancer risk be sufficiently high (suspicious finding on DRE; increased PSA, or as calculated using a combination of risk factors as noted above) transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsies of the prostate are indicated.[34]

Men successfully treated for prostate cancer and suffering from confirmed symptomatic hypogonadism are potential candidates for testosterone substitution after a prudent interval, if there is no clinical or laboratory evidence of residual cancer. As long-term outcome data are not available, clinicians must exercise good clinical judgment together with adequate knowledge of advantages and drawbacks of testosterone therapy in this situation. The risk and benefits must be clearly discussed with and understood by the patient and the follow-up must be particularly careful.[35]

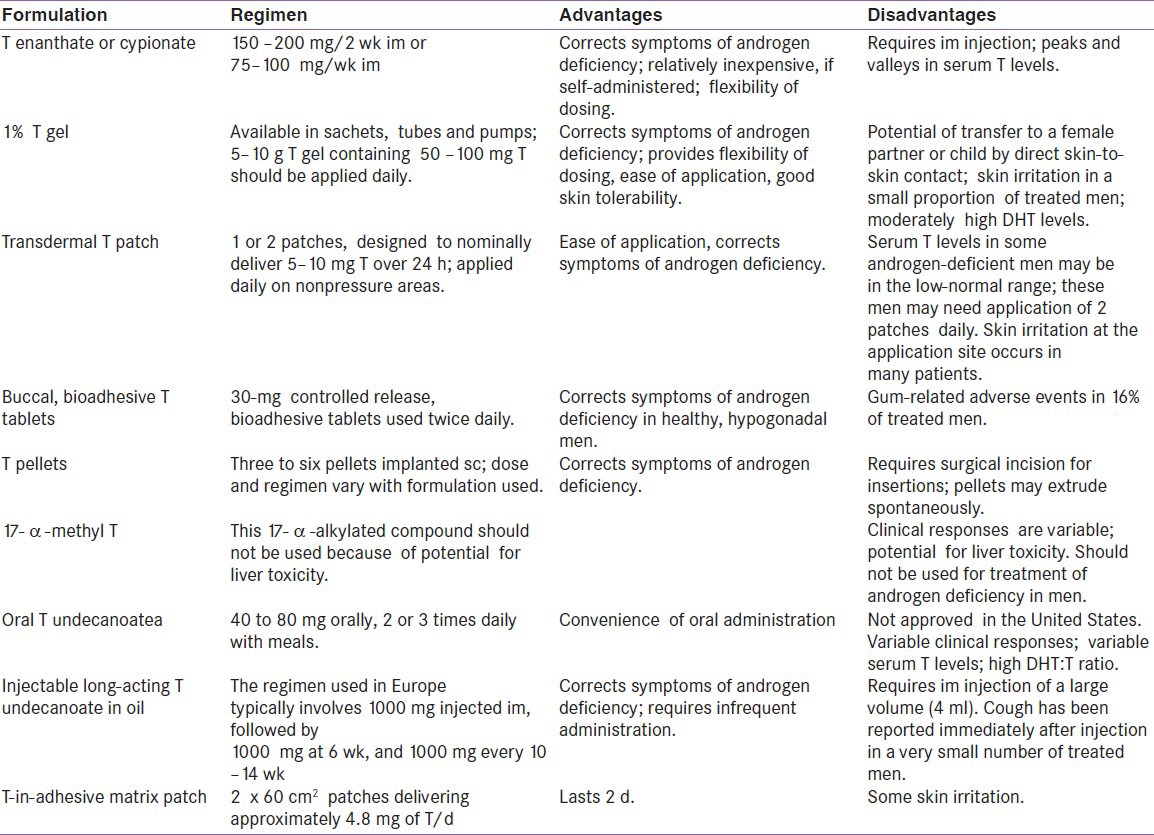

TREATMENT AND DELIVERY SYSTEMS [Table 2]

Table 2.

Advantage and disadvantages of testosterone formulations

Endocrine Society Clinical Guidelines 2010 recommend against a general policy of offering testosterone therapy to all older men with low testosterone levels. Guidelines suggest that clinicians consider offering testosterone therapy on an individualized basis to older men with low testosterone levels on more than one occasion and clinically significant symptoms of androgen deficiency, after explicit discussion of the uncertainty about the risks and benefits of testosterone therapy.

Life style modifications essentialy based on increasing physical activity and weight loss are strongly recommended in hypogonadal subjects with obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Weight loss, however it is obtained results in significant reversal of obesity associated hypogonadism.

Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline panelists disagreed on serum testosterone levels below which testosterone therapy should be offered to older men with symptoms. Depending on the severity of clinical manifestations, some panelists favored treating symptomatic older men with a testosterone level below the lower limit of normal for healthy young men (280–300 ng/dl (9.7–10.4 nmol/l)); others favored a level below 200 ng/dl (6.9 nmol/l). The panelists who favored treating men who had values <300 ng/dl were more influenced by the observation that men who have values below that level often have symptoms that might be attributable to low testosterone. The panelists who favored not treating unless the serum testosterone was as low as 200 ng/dl were more influenced by the lack of testosterone treatment effects in randomized clinical trials when subjects had pretreatment values of 300 ng/dl, but suggestions of beneficial effects when the pretreatment values were closer to 200 ng/dl. The lack of definitive studies precludes an unequivocal recommendation and emphasizes the need for additional research testosterone therapy in LOH.

Preparations of natural testosterone should be used for substitution therapy. Currently available intramuscular, transdermal, oral, and buccal preparations of testosterone are safe and effective. The treating physician should have sufficient knowledge and adequate understanding of the pharmacokinetics as well as of the advantages and drawbacks of each preparation. The selection of the preparation should be a joint decision of an informed patient and physician.

Since the possible development of an adverse event during treatment (especially elevated hematocrit or prostate carcinoma) requires rapid discontinuation of testosterone substitution, so short-acting preparations may be preferred over long-acting depot preparations in the initial treatment of patients with LOH.

Inadequate data are available to determine the optimal serum testosterone level for efficacy and safety. For the present time, mid to lower young adult male serum testosterone levels seem appropriate as the therapeutic goal. Sustained supraphysiological levels should be avoided. No evidence exists for or against the need to maintain the physiological circadian rhythm of serum testosterone levels. Obese men are more likely to develop adverse effects.

17a-alkylated androgen preparations such as 17a-methyl testosterone are obsolete because of their potential liver toxicity and should no longer be prescribed. Oral testosterone undecanoate however bypasses first pass metabolism through its preferential absorption into the lymphatic system, so free from liver toxicity. Transdermal gels are colorless hydroalcohoolic gels of 1–2% testosterone and they are applied daily to deliver 5 to 10 mg of testosterone per day. Buccal cyclodextrin complexed testosterone preparation are out of favor because of the difficulty of maintaining the buccal treatment. Subdermal implants have the risk of extrusion and local site infection. Intranasal testosterone more closely proximate the normal circadian variation of testosterone, but it requires further long-term studies to determine the effects.

There is not enough evidence to recommend substitution of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in aging men; other non-testosterone androgen precursor preparations such as DHEA, DHEA-S, androstenediol, or androstenedione are not recommended. Selective androgen receptor modulators are under development, but not yet clinically available. Many of these compounds are non-aromatizable and the risks of long-term use are unclear.

ASSESSMENT OF TREATMENT OUTCOME AND DECISIONS ON CONTINUED THERAPY

There are different time frames for improvement in signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency. Failure to benefit clinical manifestations within a reasonable time interval (3–6 months is adequate for libido, sexual function, muscle function, and improved body fat; improvement in bone mineral density requires a longer interval) should result in discontinuation of treatment. Further investigations for other causes of symptoms should be sought.

Contraindications

Testosterone treatment is contraindicated in men with prostate or breast cancer. It is unclear whether localized low-grade (Gleason score < 7) prostate cancer represents a relative or absolute contraindication for treatment. Guidelines from Endocrine Society recommend against starting testosterone therapy in patients with prostate cancer, a palpable prostate nodule or induration, prostate-specific antigen greater than 4 ng/ml or greater than 3 ng/ml in men at high risk for prostate cancer such as African Americans or men with first-degree relatives with prostate cancer without further urological evaluation, severe lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) with International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) > 19.

Recommendations from International Society of Andrology (ISA), International Society for the Study of Aging Male (ISSAM), European Association of Urology (EAU), European Academy of Andrology (EAA), and American Society of Andrology (ASA); label severe symptoms of LUTS evident by a high (21) IPSS due to benign prostate hyperplasia a relative contraindication (although there are no compelling data to suggest that testosterone treatment causes exacerbation of LUTS or promotes acute urinary retention). After appropriate and successful treatment of lower urinary tract obstruction, this contraindication is no longer applicable.[5]

Men with significant erythrocytosis with hematocrit > 50%, untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and uncontrolled or poorly controlled congestive heart failure should not be started on treatment with testosterone without prior resolution of the comorbid condition. In men with OSA, reassessment of testosterone levels is suggested after treatment of sleep apnea.

The adverse effects of testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men without preexisting contraindication include an increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit and a small decrease in HDL-C. These findings are of unknown clinical significance. Current evidence about the safety of testosterone treatment in men in terms of patient-important outcomes is of low quality and is hampered by the brief study follow-up.[36]

MONITORING PATIENT ON ANDROGEN THERAPY

When testosterone therapy is instituted, one should aim and achieve testosterone levels in the mid-normal range with any of the approved formulations, chosen on the basis of the patient's preference, consideration of pharmacokinetics, treatment burden, and cost. Testosterone level should be checked 3–6 months after initiation of treatment.

Hematocrit determination should be done at baseline, at 3–6 months, and then annually. If the hematocrit rises > 54%, then therapy has to be stopped until it decreases to safe level and therapy can be reinitiated at a reduced dose.

BMD should be evaluated after 1–2 years of testosterone therapy in men with osteoporosis or low trauma fracture.

Endocrine society guideline recommends evaluating PSA before initiating treatment, at 3–6 months and then with evidence-based guidelines for prostate cancer screening. Urology consultation is recommended if PSA rises > 1.4 ng/ml within 12-month period, PSA velocity > 0.4 ng/ml/year using PSA level after 6 months of testosterone therapy as reference (PSA velocity should be used if there is longitudinal PSA data for more than 2 years), and IPSS > 19.

Patients should be evaluated for symptoms and signs of formulation-specific adverse events at each visit; enquire about fluctuation in mood or libido, cough or local pain, and fever. Look at signs of skin reaction in case of patch or alteration in taste in case of buccal testosterone tablets.

CONCLUSION

LOH is a prevalent condition whose association with myriad age-related diseases responsible for significant morbidity and mortality among elderly men render it a disorder of immense importance to individual and for public health. Given the association between androgen deficiency and hazards of osteoporosis, cognitive decline, metabolic dysfunction, and sexual life; treatment with testosterone becomes intuitive and promising. However, disparate results of clinical trials suggest an incomplete picture of complex interaction between aging and androgen deficiency.

Hence the diagnosis of late-onset testosterone deficiency is based on the presence of symptoms or signs and persistent low serum testosterone levels. There are certain indications for which benefits are well-documented. The benefits and risks of testosterone therapy must be clearly discussed with the patient and assessment of prostate and other risk factors considered before commencing testosterone treatment Response to testosterone treatment should be assessed and if there is no improvement of symptoms and signs, treatment should be withdrawn and the patient investigated for other possible causes of the clinical presentations which is of great importance in elderly male. And lastly, age is not a contraindication to initiate testosterone treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Matsumoto AM. Andropause: Clinical implications of the decline in serum testosterone level with aging in men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57:M76–99. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.2.m76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travison TG, Araujo AB, Kupelian V, O’Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. Relative contribution of aging, health, and life-style factors to serum testosterone decline in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:549–55. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morales A, Spevack M, Emerson L, Kuzmarov I, Casey R, Black A, et al. Adding to the controversy: Pitfalls in the diagnosis of testosterone deficiency syndromes with questionnaires and biochemistry. Aging Male. 2007;10:57–65. doi: 10.1080/13685530701342686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley JE, Charlton E, Patrick P, Kaiser FE, Cadeau P, McCready D, et al. Validation of a screening questionnaire for androgen deficiency in aging males. Metabolism. 2000;49:1239–42. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.8625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, O’Donnell AB, Travison TG, Williams RE, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4241–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tajar A, Huhtaniemi IT, O’Neill TW, Finn JD, Pye SR, Lee DM, et al. EMAS Group. Characteristics of androgen deficiency in late onset hypogonadism: Results from European Male Aging Study (EMAS) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1508–16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, Hellstrom WJ, Gooren LJ, et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA recommendations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:507–14. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bassil N. Late onset hypogonadism. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:507–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diver MJ, Imtiaz KE, Ahmad AM, Vora JP, Fraser WD. Diurnal rhythms of serum total, free and bioavailable testosterone and of SHBG in middle-aged men compared with those in young men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58:710–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, et al. Task Force, Endocrine Society. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice guidelines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536–59. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: An Endocrine Society Position Statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:405–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Plymate S, Nieschlag E, Paulsen CA. Salivary testosterone in men: Further evidence of a direct correlation with free serum testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;53:1021–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem-53-5-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunch TJ, Abraham D, Wang S, Meikle AW. Pituitary radiographic abnormalities and clinical correlates of hypogonadism in elderly males presenting with erectile dysfunction. Aging Male. 2002;5:38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buvat J, Lemaire A. Endocrine screening in 1,022 men with erectile dysfunction: Clinical significance and cost-effective strategy. J Urol. 1997;158:1764–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunningham GR, Toma SM. Clinical review: Why is androgen replacement in males controversial? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:38–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allan CA, Strauss BJ, Burger HG, Forbes EA, McLachlan RI. Testosterone therapy prevents gain in visceral adipose tissue and loss of skeletal muscle in nonobese aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:139–46. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, Berlin JA, Loh L, Lenrow DA, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2647–53. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freitas SS, Barrett-Connor E, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, Bauer DC, Cawthon PM, et al. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Research Group. Rate and circumstances of clinical vertebral fractures in older men. Osteoporos Int. 2007;19:615–23. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0510-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, Gianfrilli D, Bonifacio V, Isidori A, et al. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: A meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63:280–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tracz MJ, Sideras K, Bolon ER, Haddad RM, Kennedy CC, Uraga MV, et al. Testosterone use in men and its effects on bone health. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomsed placebo controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2011–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Travison TG, Morley JE, Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. The relationship between libido and testosterone levels in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2509–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenstein A, Mabjeesh NJ, Sofer M, Kaver I, Matzkin H, Chen J. Does sildenafil combined with testosterone gel improve erectile dysfunction in hypogonadal men in whom testosterone supplement therapy alone failed? J Urol. 2005;173:530–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000149870.36577.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhindsa S, Prabhakar S, Sethi M, Bandyopadhyay A, Chaudhuri A, Dandona P. Frequent occurrence of hypo-gonadotropic hypogonadism in Type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5462–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapoor D, Aldred H, Clark S, Channer KS, Jones TH. Clinical and biochemical assessment of hypogonadism in men with type 2 diabetes: Correlations with bioavailable testosterone and visceral adiposity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:911–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupelian V, Page ST, Araujo AB, Travison TG, Bremner WJ, McKinlay JB. Low sex hormone-binding globulin, total testosterone, and symptomatic androgen deficiency are associated with development of the metabolic syndrome in nonobese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:843–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapoor D, Goodwin E, Channer KS, Jones TH. Testosterone replacement therapy improves insulin resistance, glycaemic control, visceral adiposity and hypercholesterolaemia in hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:899–906. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basu R, Dalla MC, Campioni M, Basu A, Nair KS, Jensen MD, et al. Effect of 2 years of testosterone replacement on insulin secretion, insulin action, glucose effectiveness, hepatic insulin clearance, and postprandial glucose turnover in elderly men. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1972–8. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, West JN, van Beek EJ, Jones TH, Channer KS. Testosterone therapy in men with moderate severity heart failure: A double-blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:57–64. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claustres M, Sultan C. Androgen and erythropoiesis: Evidence for an androgen receptor in erythroblast from human bone marrow cultures. Horm Res. 1988;29:17–22. doi: 10.1159/000180959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thilers PP, Macdonald SW, Heriletz A. The association between endogenous free testosterone and cognitive performance: A population based study in 3590 year old men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:565–76. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, Key TJ. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: A collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:170–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter WR, Robinson WR, Godley PA. Gettingovertestosterone: Postulating a fresh start for etiologic studies of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:158–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: Results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhasin S, Singh AB, Mac RP, Carter B, Lee MI, Cunningham GR. Managing the risks of prostate disease during testosterone replacement therapy in older men: Recommendations for a standardized monitoring plan. J Androl. 2003;24:299–311. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman JM, Graydon RJ. Androgen replacement after curative radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer in hypogonadal men. J Urol. 2004;172:920–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000136269.10161.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calof OM, Singh AB, Lee ML, Kenny AM, Urban RJ, Tenover JL, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older men: A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1451–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]