Abstract

A new human papillomavirus (HPV) assay using high-density DNA microarrays is described. An HPV DNA fragment from the 3′ end of the E1 gene was amplified and digoxigenin labeled by PCR, and the resulting amplicons were hybridized onto type-specific oligonucleotides immobilized on high-density DNA microarrays. For detection, a simple immunohistochemical staining procedure was used with a substrate that has both colorimetric and fluorescent properties. This detection chemistry enables the rapid identification of reactive spots by regular light microscopy and semiquantification by laser scanning. Both single and multiple HPV infections are recognized by this assay, and the corresponding HPV types are easily identified. With this assay, 53 mucosal HPV types were detected and identified. A total of 45 HPV types were identified by a single type-specific probe, whereas the remaining 8 mucosal HPV types could be identified by a specific combination of probes. The simple assay format allows usage of this assay without expensive equipment, making it accessible to all diagnostic laboratories with PCR facilities.

To date, more than 80 human papillomavirus (HPV) types have been described that are involved in either cutaneous or genitomucosal lesions of the skin. Because of the strong association of certain HPV types with cervical cancers, the genital-mucosal HPV types have been divided into clusters of types with a relative high risk or a relative low risk of an HPV infection progressing into cervical cancer. The data from combined case-control studies (19) suggest that some HPV types should be regarded high-risk or carcinogenic (e.g., HPV16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59, -68, -73, and -82) and that some should be considered probably carcinogenic (HPV26, -53, and -66), whereas the relative risk associated with certain other HPV types may be only low (e.g., HPV6, -11, -40, -42, -43, -44, -54, -61, -70, -72, and -81).

Several DNA-based assays have already been developed for the simultaneous broad identification and subtyping of HPV types. The majority are PCR-based assays with a variety of PCR primers being used, such as the MY09-MY11, GP5+-GP6+, SPF, and PGMY09-PGMY11 primer combination(s) (5, 7, 15, 18). For typing purposes these assays have been combined with dot blots (10, 18, 29), microtiter enzyme immunoassays (11, 15), reverse hybridization line probe assays (4, 8, 14, 26), cycle sequencing (28), T-ladder generation (20), and pyrosequencing (6). Several non-PCR methods have been designed as well, such as the hybrid capture assay (17) and the in situ hybridization approach (25).

The large variety of techniques available for detection and subtyping of the multitude of HPV types illustrates the fact that no single technique provides the ultimate and complete solution to this effect. This is especially indicated by the observed differences between existing techniques with respect to analytical sensitivity, ability to discriminate between different HPV types, and ability to recognize multiple infections (4, 7, 12, 14, 15, 22, 26-28). Moreover, existing assays still fail to identify all of the possible HPV types involved since they were designed to detect only a subset of the mucosal HPV types. This circumstance justifies the development of new and improved HPV assays.

Here, we introduce a new broad HPV assay format based on high-density DNA microarrays. Digoxigenin-labeled HPV-derived PCR amplicons are hybridized onto type-specific biotinylated HPV probes immobilized on streptavidin-coated glass slides. Hybridized amplicons are visualized by using a simple immunohistochemical staining procedure with a substrate for alkaline phosphatase that has both colorimetric and fluorescent properties. This detection chemistry enables rapid identification of reactive spots with regular light microscopy, as well as semiquantification by laser scanning. Single and multiple HPV infections are easily recognized, and the corresponding HPV types can be identified. The simple assay format allows usage of this assay without expensive equipment, making it accessible to all diagnostic laboratories with PCR facilities. With this assay format it is possible to detect and identify 53 genital HPV types, the largest HPV panel thus far.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HPV sequences.

The following sequences from officially recognized HPV types were included in the present study (with the GenBank accession number in parentheses [latest update for HPV search, 12 February 2003]): HPV1 (U06714 and V01116), HPV2 (X55964), HPV3 (X74462), HPV4 (X70827), HPV5 (M22961, M17463, and D90252), HPV6 (AF092932, L41216, and X00203), HPV7 (X74463), HPV HPV8 (M12737), HPV9 (X74464), HPV10 (X74465), HPV11 (M14119), HPV12 (X74466), HPV13 (X62843 and S43933), HPV14 (X74467), HPV15 (X74468), HPV16 (K02718, U89348, and AF125673), HPV17 (X74469), HPV18 (X05015), HPV19 (X74470), HPV20 (U31778), HPV21 (U31779), HPV22 (U31780), HPV23 (U31781), HPV24 (U31782), HPV25 (X74471), HPV26 (X74472), HPV27 (X74473), HPV28 (U31783), HPV29 (U31784), HPV30 (X74474), HPV31 (J04353), HPV32 (X74475), HPV33 (A07020, A12360, and M12732), HPV34 (X74476), HPV35 (M74117 and X74477), HPV36 (U31785), HPV37 (U31786), HPV38 (U31787), HPV39 (M62849), HPV40 (X74478), HPV41 (X56147), HPV42 (M73236), HPV44 (U31788), HPV45 (X74479), HPV47 (M32305), HPV48 (U31789), HPV49 (X74480), HPV50 (U31790), HPV51 (M62877), HPV52 (X74481), HPV53 (X74482), HPV54 (U37488), HPV55 (U31791), HPV56 (X74483), HPV57 (U37537 and X55965), HPV58 (D90400), HPV59 (X77858), HPV60 (U31792), HPV61 (U31793), HPV63 (X70828), HPV65 (X70829), HPV66 (U31794), HPV67 (D21208), HPV69 (AB027020), HPV70 (U21941), HPV71 (AB040456), HPV72 (X94164), HPV73 (X94165), HPV74 (AF436130), HPV75 (Y15173), HPV76 (Y15174), HPV77 (Y15175), HPV80 (Y15176), HPV82 (AB027021), HPV83 (AF151983), HPV84 (AF293960), HPV85 (AF131950), HPV86 (AF349909), HPV87(AJ400628), HPV89 (AF436128), HPV90 (AY057438), HPV91 (AF419318), and HPV92 (AF531420).

Selection of a target region and design of PCR primers.

Available HPV DNA sequences (whole genome, individual genes as well as gene specific fragments) were separately and systematically analyzed for sequence homology by creating multiple DNA sequence alignments by using the CLUSTAL X program (24). A target region was selected based on the following considerations: (i) DNA sequence alignment of the target region should yield a clear separation into a minimal number of clusters containing primarily low-risk, high-risk, or cutaneous HPV types. This condition would facilitate and simplify the design of cluster- and thus risk-specific PCR amplification primers; (ii) the target region should contain sufficient DNA heterogeneity to allow design of type-specific oligonucleotide probes in order to discriminate between as many HPV types as possible; and yet (iii) should be flanked by regions with sufficient DNA sequence homology to allow formulation of (degenerate) PCR primers and (iv) the target region should not be too long, which might complicate efficient DNA amplification by PCR. According to these considerations, a suitable target region was selected at the C terminus of the HPV E1 gene. Based on the alignments, HPV sequences were subdivided into six clusters containing either low-risk mucosal HPV types (clusters LR-1 and LR-2), high-risk mucosal types (clusters HR-1, HR-2, and HR-3), or cutaneous HPV types (cluster C) (Table 1). Degenerate PCR primers were formulated for each of the genital HPV clusters to allow amplification of HPV types in a cluster-specific manner (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Subdivision of 84 HPV types (53 mucosal and 31 cutaneous) into six clustersa

| Cluster | HPV types |

|---|---|

| LR-1 | 6, 7, 11, 13, 32, 40, 42, 44, 55, 74, 91 |

| LR-2 | 2, 3, 10, 27, 28, 29, 54, 57, 61, 71, 72, 77, 83, 84, 86, 87, 89 |

| HR-1 | 16, 31, 33, 35, 52, 58, 67 |

| HR-2 | 18, 39, 45, 59, 68, 70, 85 |

| HR-3 | 26, 30, 34, 51, 53, 56, 66, 69, 73, 82 |

| C | 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 36, 37, 38, 41, 47, 48, 49, 50, 60, 63, 65, 75, 76, 80, 92 |

LR, low-risk HPV types; HR, high-risk or probably high risk HPV types; C, cutaneous HPV types. The basis for this division was a phylogenetic analysis of available HPV E1 gene sequences. No E1 sequence was found for HPV43, -46, -62, -64, -68, -78, -79, -81, and -88. HPV68 was grouped into cluster HR-2 due to the high level of similarity in the L1 region of this HPV type to HPV39 and HPV70.

TABLE 2.

Overview of primary PCR amplification primers used in this studya

| Cluster | Sequence

|

Amplicon size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | Reverse primer | ||

| LR-1 | 5′-GTGCCAGGAWCAGTTGTTAG-3′ | 5′-TCYTGYAAHGTCCAHGGYTC-3′ | 258 |

| LR-2 | 5′-GAAATSVTTYTTYMRAAGGT-3′ | 5′-TCCTGGCACRCATCTAAACG-3′ | 105-117 |

| HR-1 | 5′-CCTTTTTCTCAAGGACGTGG-3′ | 5′-GNHGGHACCACBTGGTGG-3′ | 245 |

| HR-2 | 5′-CDTGGTSCARATTAGAYTTG-3′ | Identical to HR-1 | 232 |

| HR-3 | 5′-TTTBHAAATVCATTTCCAWTWGA-3′ | 5′-TAAACGHTKRSAHAGNKTCTCCAT-3′ | 151-154 |

| β-Globin | 5′-CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC-3′ | 5′-GAAGAGCCAAGGACAGGTAC-3′ | 71 |

For labeling purposes in a second consecutive asymmetric PCR reaction, each of the HPV cluster-specific reverse primers was extended at the 5′ end with an M13 universal primer tag (5′-GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′). Degenerate primer positions are indicated according to the single-letter convention: R = A and G; Y = C and T; W = A and T; S = C and G; M = A and C; K = G and T; B = C, G, and T; D = A, G, and T; H = A, C, and T; V = A, C, and G; N = A, C, G, and T.

Design of type-specific HPV probes.

HPV type-specific oligonucleotide probes (20-mers) were formulated and checked for specificity by BLAST analysis (1) (Table 3). Each probe contained a minimum of two mismatches (around the center of the probe) to all other HPV types wherever possible. In a few cases, no discrimination between certain HPV types could be made on theoretical grounds (for instance, for the closely related HPV types 2 and 27, with which there is only one nucleotide difference between both amplicons). For these cases, either a single probe was used to detect both types or a unique combination of probes was used to establish the differentiation (Table 3). All probes were synthesized with a biotinylated tag at the 5′ end. The biotin label was introduced for immobilization of the probes onto streptavidin-coated glass slides, and the additional tag was used for quality control procedures (see Results) and for reduction of possible steric hindrance by the solid support.

TABLE 3.

Overview of type-specific HPV probes used in this studya

| HPV type(s) | Probe sequence | Position(s)b |

|---|---|---|

| 2+27 | 5′-AGAGGAGCAGGACGACAATG-3′ | 2668 (HPV2) and 2678 (HPV27) |

| 3 | 5′-TGAAGACGAGGAGGACAATG-3′ | 2710 |

| 6 | 5′-CCATTAAAGGTGTCCGAAGC-3′ | 2904 |

| 7 | 5′-AGATGTGTCAAAAGCCAAAG-3′ | 2935 |

| 10 | 5′-CGAGGAGGAGCATGGAAACC-3′ | 2767 |

| 11 | 5′-CCATTAACTGTGTCAGAGAC-3′ | 2903 |

| 13 | 5′-ATTGACAGTATCACAAGCTA-3′ | 2907 |

| 16 | 5′-CAGACCTACGTGACCATATA-3′ | 2825 |

| 18 | 5′-ACATGGCATACAGACATTAA-3′ | 2972 |

| 26+69 | 5′-ATTGACTGATGTAAATTGGA-3′ | 2656 (HPV26) and 2652 (HPV69) |

| 27 | See HPV2 | |

| 28 | 5′-GAGGAAAATGGAAACCCTAG-3′ | 2711 |

| 29+77 | 5′-GGAAAATGGAGAACCTAGCG-3′ | 2722 (HPV29) and 2725 (HPV77) |

| 30 | 5′-GATTTGAACAACGACGAAGA-3′ | 2696 |

| 31 | 5′-TAGTAAACGACTTTGTGATC-3′ | 2758 |

| 32 | 5′-AGCACTGGAAATATCCAGGG-3′ | 2899 |

| 33 | 5′-CTTTATTGTATACAGCCAAA-3′ | 2870 |

| 34 | 5′-AGTAATGGAAATCCACTATA-3′ | 2630 |

| 35 | 5′-TAGCACATGTTTGTCTGATC-3′ | 2761 |

| 39 | 5′-AGAATACTATGAACAAGACA-3′ | 2860 |

| 40 | 5′-AGATGTTTCAAAGGCTAAAG-3′ | 2938 |

| 42 | 5′-AACATTGGAAACATGTAGAG-3′ | 2881 |

| 44 | 5′-GAAATGTATACGATATGAAT-3′ | 2803 |

| 45 | 5′-ACATGGTATTACCAAACTAA-3′ | 2930 |

| 51 | 5′-AATGCTGTGTATACATTGAA-3′ | 2626 |

| 52 | 5′-TTTTGTTTTACAAAGCAAAG-3′ | 2864 |

| 53 | 5′-AATTGATGTGAATGGAAATC-3′ | 2628 |

| 54 | 5′-TTTAGCGCTGAACGACAACG-3′ | 2633 |

| 55 | 5′-TGTTATTACACAAAGCAAAG-3′ | 2826 |

| 56 | 5′-AAATGTTTCTTTACAAGGAC-3′ | 2682 |

| 57 | 5′-AGAGGATCAGGAAGACAATG-3′ | 2666 |

| 58 | 5′-CTATAATGTATACAGCCAGA-3′ | 2874 |

| 59 | 5′-AGACATTAATGAACACATAA-3′ | 2819 |

| 61 | 5′-AGAGGGATCTGATCAACAGG-3′ | 2667 |

| 66+30+53 | 5′-TTTTTTTGAAAGGACATGGT-3′ | 2767 (HPV18)*, 2725 (HPV45)*, 2668 (HPV30), 2682 (HPV53), and 2670 (HPV66) |

| 67 | 5′-CTTTGTATTATAAAGCTAAA-3′ | 2842 |

| 68 (putative) | 5′-AAATGTATACAGGACCATAT-3′ | |

| 69 | 5′-AGTTTTTTTTCCACCACTTG-3′ | 2674 |

| 70 | 5′-AGAACATTATGAACAGGACA-3′ | 2875 |

| 71+90 | 5′-GACTTACACGAGCAGGACGA-3′ | 2673 (HPV71) and 2576 (HPV90) |

| 72 | 5′-AGAGGGACCTGACGAACAGG-3′ | 2687 |

| 73 | 5′-AGTAATGGGAACCCACTATA-3′ | 2638 |

| 74 | 5′-GAAATGTGTACGGCACGAAA-3′ | 2683 |

| 77+10+28 | 5′-TTAAGACTTACCGATCCTGA-3′ | 2696 (HPV77), 2744 (HPV10)†, and 2684 (HPV28)† |

| 82 | 5′-TATATGCACTAAATGATGTA-3′ | 2659 |

| 83 | 5′-TTTAGAATTGCATCAAGAGG-3′ | 2571 |

| 84 | 5′-AGGAGGAGTCCCAAAATGGA-3′ | 2594 |

| 85 | 5′-AACATTACGAGACTGATAGT-3′ | 2851 |

| 86 | 5′-AGGCTGACAATGGATACACT-3′ | 2600 |

| 87 | 5′-AGGCGGACAATGGATGCACT-3′ | 2703 |

| 89 | 5′-GTTTAGACTTACAACCTGAG-3′ | 2582 |

| 90 | See HPV71 | |

| 91 | 5′-AAAGCTAGAAGTATCACGAG-3′ | 2990 |

For immobilization and quality control purposes, all probes are extended at the 5′ end with a biotinylated tag (see the text for details). For each probe, the position of its 5′ end in the corresponding HPV genome(s) is given.

Although the probe sequence marked with an asterisk is also present in the HPV18 and HPV45 genome, it is not present in the HPV18 and HPV45 amplicons. Therefore, this probe will not give rise to a hybridization signal with these two HPV types. The probe sequence marked with a dagger (†) contains one mismatch with respect to this HPV type. Type-specific probes for HPV10 and HPV28 are also present on the array.

Samples.

To obtain as many different HPV types as possible to validate the specificity of this novel assay, two different clinical sample collections were screened. The first collection consisted of 30 archival formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies with proven HPV presence, as determined by using the HPV PCR-enzyme immunoassay approach (11). These samples contained at least one high-risk and/or low-risk HPV type. The second sample collection contained 100 liquid-based cytology samples. These samples were routinely collected as part of cervical screening procedures.

DNA isolation.

DNA was isolated from 10- μm-thick paraffin sections by using a Puregene DNA isolation kit from Gentra Systems (Biozym B.V., Landgraaf, The Netherlands) according to the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. After centrifugation of the liquid-based cytology samples, the cell pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, DNA was isolated by using a QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the recommended protocol. Isolated DNA was quantitated by using UV absorbance measurements, taking into account an optical density conversion factor at 260 nm of 1 at ∼50 μg of DNA/ml (23). The isolated DNA was of excellent purity, as judged by the A260 /A280 value of ∼1.8.

Primary PCR amplification.

Target amplification was performed in a T1 or T gradient thermocycler (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) in five separate 50- μl reactions (one for each cluster) containing 100 ng of template DNA, 1 μM concentrations of both forward and reverse amplification primers, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 U of HotGoldStar DNA polymerase (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium), 1× reaction buffer, and 2 mM MgCl2 . Cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min of denaturation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 95°C, 30 s of annealing at 52°C, and 1 min of extension at 72°C. Before the reactions were cooled to room temperature, an additional incubation for 10 min at 72°C was performed. All temperature transitions were performed with maximal heating and cooling settings (5°C/s). In order to check for the presence of PCR inhibitors in the DNA samples, an additional PCR was performed under the same experimental conditions with primers targeting the human β-globin gene (Table 1). In order to check for positive PCR results, 5 μl of the PCR was analyzed on an agarose gel according to standard procedures (23).

Digoxigenin labeling and generation of single-stranded amplification products.

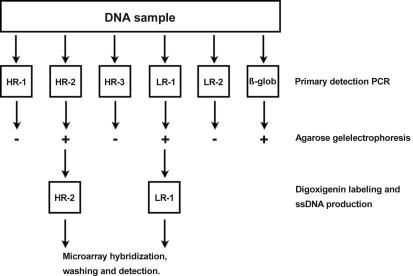

Labeling of the obtained HPV PCR amplicons was established with an asymmetrical PCR procedure similar to the conditions described above. The cluster-specific forward primer was used, and the sequence of the reverse primer was identical to the sequence of the tag added to all HPV reverse amplification primers, which was labeled at the 5′ end with digoxigenin. The concentration of the primers was 0.05 μM for the forward primer and 1.0 μM for the reverse primer, respectively. Each labeling reaction contained 1 μl of the PCR original amplification reaction that tested positive. By applying the asymmetrical PCR, all reaction products were simultaneously labeled, as well as amplified into single-stranded products that could be used in the microarray hybridization procedure without further purification or treatment. In case of multiple positive primary amplification reactions, they were further processed separately. A flowchart describing the amplification and labeling procedure is given in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Experimental flow chart showing the primary amplification and labeling procedure. Sample DNA (100 ng) is amplified in six separate primary PCRs: five for each HPV cluster and one for β-globin. The β-globin test is to ensure the presence of PCR quality DNA in the sample. To check for positive PCRs, an aliquot (5 μl) of the primary PCR is run on a standard agarose gel. One microliter of each positive primary reaction was reamplified in a second asymmetric PCR with a low concentration (0.05 μM) of the original forward PCR primer and a high concentration (1 μM) of a digoxigenin-labeled universal primer (see the text for more details). The resulting digoxigenin-labeled and single-stranded PCR products are used without further processing in microarray hybridization, washing, and detection experiments. In this example the process is shown for a sample containing both a high-risk and low-risk HPV type.

Preparation of the microarrays.

HPV type-specific probes were spotted onto streptavidin-coated glass slides (Dot Diagnostics, Beuningen, The Netherlands) at a concentration of 12 μM in spotting buffer (3× SSC [1 × SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 1.5 M betaine [pH 7.0]) by using a SDDC-2 array spotting robot (ESI, Toronto, Canada) equipped with Stealth Microspotting Pins 3 (Telechem International, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.). These pins deliver ca. 0.6 nl at each spotting site, resulting in spots of ca. 100 μm in diameter. Spots were printed in triplicate, with a dot spacing in x and y axes of 400 μ m. The relative humidity during spotting varied between 45 and 60%, whereas the temperature was kept constant at 22°C. After visual inspection of the slides after printing (see Results), the slides were stored. This could be done for a minimum of 3 months without negative effects on the results (data not shown).

For orientation purposes after completion of the entire hybridization, staining, and detection procedure, a randomized double-stranded oligomer (20 bp) was used in the spotting process. This oligomer contained on one strand a 5′ biotin label for immobilization onto the glass slides and on the other strand a 5′ digoxigenin label for visualization. A number of negative control spots were also generated by applying only spotting buffer to the slides.

Microarray hybridization.

All hybridization incubations and washing steps were performed at room temperature in disposable coverplates (Thermo-Shandon, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Standard microscope slides fit in these coverplates and are held in a vertical position during the entire procedure. A distance of 80 μm is maintained between the surface of the slides and the disposable coverplate. In this setup, the incubation mixture is being held in position by capillary forces (effective working volume of ∼80 μl). Washing the slides is performed simply by adding wash buffer to the upper reservoir (ca. 3 ml) and allowing it to pass the array by gravity. Printed arrays were first washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween for 10 min (PBS-Tween; 1 mM KH2 PO4 , 0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM Na2 HPO4 · 7H2 O [pH 7.4], 0.05% [wt/vol] Tween 20). Next, the microarrays were prehybridized in 40% formamide-3.3× SSC-1.7 mM EDTA-17 mM HEPES-0.12% Tween 20 (pH 7.3) for 5 min and subsequently hybridized in the same solution containing 20 μl of the unpurified single-stranded digoxigenin-labeled PCR product for 1 h. Five subsequent washes of 5 min each were performed with PBS-Tween, 2× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1× SSC-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1× SSC, and 0.05× SSC, respectively.

Immunodetection and visualization of the microarrays.

Detection of the digoxigenin-labeled and hybridized PCR products was performed as described before (21). In short, a 1:100 dilution of a mouse monoclonal antibody to digoxigenin was incubated (Roche Diagnostics, Almere, The Netherlands). Next, a 45-min incubation with a 1:20 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins (Dako, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was performed. Alkaline phosphatase activity was detected by using Vector Blue as a substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The reaction product of Vector Blue can be seen by using both bright-field and fluorescence microscopy. Slides analyzed by laser scanning were washed twice for 5 min in PBS-Tween, rinsed in water, washed for 3 min in ethanol, and subsequently air dried in the dark. The Vector Blue reaction product yields blue spots visible by light microscopy and red spots upon excitation at 635 nm by laser scanning.

Imaging.

Slides were scanned with a GenePix 4000A microarray laser scanner and data were analyzed with GenePix Pro 4.1 software (both from Axon Instruments, Foster City, Calif.). This scanner is equipped with a 532-nm laser and a 635-nm laser. Sixteen-bit TIFF images at 10- μm resolution were subtracted for local background intensity. Alternatively, when a low-magnification lens is used (× 2.5), the whole array can be viewed in one image without the need for special filters or adaptors (total magnification including ocular, × 25). For documentation, the result was recorded with a charge-coupled device camera (Sony DSC-S75) attached to the microscope.

DNA sequence analysis.

PCR amplicons were purified by using a High-Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Purified amplicons were sequenced with the respective amplification primers on an ABI 3700 automated DNA analysis platform (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk aan den Ijssel, The Netherlands) by using conditions recommended by the manufacturer. The identity of the obtained sequences was verified by using basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) analysis (1).

RESULTS

Quality control procedures.

In the design of this novel assay, a number of internal control procedures were included to check the various steps of the entire assay procedure (amplification, spotting, hybridization, visualization, and interpretation).

Amplification control.

Apart from the HPV cluster-specific PCRs, a β-globin PCR was included to verify the quality of the obtained DNA. This is particularly relevant when no HPV amplicon is obtained. All DNA samples used contained PCR quality DNA (not shown).

Spotting control.

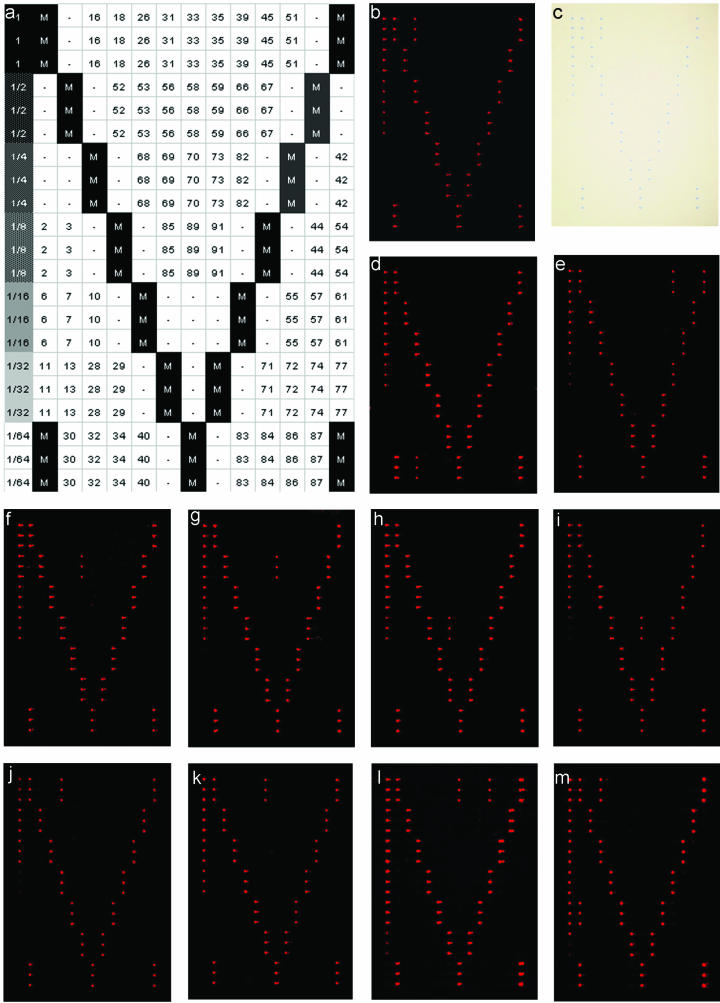

Since extremely tiny volumes are spotted onto the glass slides (on average, ∼0.6 nl), it is virtually impossible to check the spotting process at this stage. Upon removal of the slides from the spotting cabinet, these tiny amounts of buffer are vaporized in seconds, leaving nothing to see with the naked eye. However, upon addition of 1.5 M betaine to the spotting buffer, spots remain visible until the betaine is washed away (not shown). Furthermore, each probe is spotted in triplicate to compensate for incidental misprints (see examples in Fig. 2).

FIG.2.

(a) Reference chart showing an overview of the microarray layout. Diagonally placed marker spots (M) were used to indicate the rows and the columns of the array and to indicate the corners. On the left, a column with serial dilution of the marker spots was applied to monitor the sensitivity of the staining procedure and the daily variations in the staining process. Blank spots (“-”) were included to serve as negative controls. All items were spotted in triplicate. (b and c) Example of HPV16 detection by fluorescence (b) and in an absorption image (c) of the same slide. (d to m) Examples of a single HPV32 (d), HPV45 (e), HPV56 (f), HPV58 (g), HPV85 (h), HPV89 (i), HPV18 (j), and HPV31 (k). (l and m) Examples of multiple HPV infections with HPV33 and HPV45 (l) and HPV6 and HPV16 (m).

Visualization control.

Separate marker spots are created containing a digoxigenin label. These are printed on the slides in serial dilutions. By including these marker spots, not only the immunohistochemical staining procedure itself but also the relative sensitivity can be checked. Likewise, this controls serves to monitor daily variations in the staining procedure (Fig. 2).

Interpretation control.

All marker spots are printed in an easily recognized asymmetric pattern to aid in orientation of the results upon completion of the entire assay procedure compared to a reference chart (Fig. 2a). The diagonally placed marker spots serve to indicate the columns as well as the rows of the microarray.

Demonstration of the HPV microarray.

In Fig. 2, a number of typical results obtained by using this novel HPV detection and identification method are presented. The images shown for regular light microscopy and laser scanning were obtained from the same slide (Fig. 2b and c). This clearly shows that these visualization methods share the same level of sensitivity but also that a regular light microscope suffices for qualitative HPV typing. The ability to detect and identify multiple HPV infections is also demonstrated in Fig. 2. Examples are given for mixed infections containing HPV6 and -16 or HPV33 and -45. No discrepancies were found between light-microscopic examination and laser scanning of the results.

All microarray results from samples in which a positive PCR yielded a single HPV type were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis of the obtained amplicons. No discrepancies were found. Only one of the obtained amplicons did not hybridize to any of the spots in a preliminary version of this array setup. DNA sequence analysis of this amplicon yielded a sequence closely related to both HPV39 and HPV70. We assumed that this amplicon was derived from HPV68, a high-risk HPV type reported to be most closely related to exactly these two other HPV types (16). For HPV68, no E1 gene sequence has been reported yet. A probe was formulated and included on the final microarray for this HPV type as well (Table 2). At present, of the 51 spotted mucosal HPV types on the array, the following 30 HPV types were already encountered in our clinical sample collection: HPV2, -6, -11, -16, -18, -27, -31, -32, -33, -35, -39, -42, -44, -45, -52, -53, -55, -56, -57, -58, -59, -66, -67, -68, -69, -70, -74, -82, -85, and -89. Among these HPV types are the most frequently occurring HPV types, as determined by other existing assays: HPV16, -18, and -45 (19). All of these HPV types have properly been identified by using this novel HPV microarray assay procedure. These results nicely illustrate the proof of principle for the design and applicability of this novel HPV microarray assay.

DISCUSSION

We have developed a new and simple assay format for the detection and subtyping of HPV based on DNA microarrays. The assay is easy to perform and able to recognize and discriminate between the largest number of different genital HPV types thus far. In the design of the assay, special considerations were made to keep the need for expensive specialty laboratory equipment and reagents as low as possible, making it accessible, affordable, and easily implemented in any diagnostic laboratory. Basically, only a regular thermocycler and a light microscope are needed. The easy implementation is further established by the experimental design, including the disposable coverplates, and by performing hybridization and visualization steps at room temperature, eliminating the need for water baths or incubation ovens. Moreover, the detection chemistry used allows interpretation of the results by eye through a regular light microscope, without compromising either the sensitivity or the final result of the assay, thereby eliminating the need for the expensive laser-scanning devices often used in microarray experiments.

Previously reported HPV assays (14, 26) were designed to amplify multiple HPV types, including both low-risk and high-risk HPV types. With these assays, no discrimination between the two groups can be made at the amplification level. However, from a clinical perspective, there would be no need to screen for low-risk HPV types, and analyses could be restricted to high-risk types only. In the design of this novel assay, we chose to perform separate PCRs for high-risk and low-risk HPV types. This condition allows analysis of a user-defined selection for testing only high-risk HPV types, low-risk HPV types or combinations thereof based on the users' interests. Of course, this is only possible if there is no or only incidental cross-reactivity between the different groups at the DNA amplification level. Due to DNA sequence homology in the PCR primer region between high-risk HPV clusters, some level of cross-reactivity between these high-risk clusters can theoretically occur and has been observed at the DNA amplification level (data not shown). However, despite this cross-reactivity between high-risk HPV types, this has not interfered with proper identification of the HPV type(s) involved at the microarray hybridization level. A minor disadvantage of this approach is that multiple primary amplification reactions have to be performed. However, in the majority of the cases only one of these reactions will be positive, so only one labeling reaction and microarray hybridization experiment will have to be performed per sample. Only in the case of two (occasional event) or three (rare event) positive primary amplification reactions, do multiple labeling reactions and microarray hybridization experiments have to be performed. At least theoretically, these can be combined into one labeling reaction and microarray hybridization experiment. This, however, has not been examined in the present study.

The concept of HPV typing by microarray has been reported before. An et al. reported a HPV microarray assay based on a degenerate GP5+-GP6+ primer combination (2). However, the reported assay format still required a DNA chip scanner and was designed to detect a subset of only 22 HPV types. The same assay was reportedly used in other studies as well (3, 9, 13). With our novel HPV microarray assay, 53 genital HPV types could be detected and subtyped. This includes 27 HPV types, including all high-risk types, for which the classification into high-risk or low-risk types is supported by epidemiological data (19). Only two HPV types with a supported classification (HPV43 and -81 [both low risk]) could not be included due to the unavailability, in the public domain, of a DNA sequence for the corresponding region of the HPV E1 gene for these HPV types. For six more HPV types (HPV46, -62, -64, -78, -79, and -88 [all with an undetermined risk]), no corresponding genomic DNA sequences were found in the public databases. However, these HPV types were also not included in previously reported HPV assays. Our grouping in high-risk and low-risk clusters, based on DNA sequence homology, is in excellent agreement with epidemiological data (with the sole exception of HPV70). Based on DNA sequence homology, 25 HPV types with unknown risk may putatively be grouped either into the low-risk HPV clusters (HPV2, -3, -7, -10, -13, -27, -28, -29, -32, -55, -57, -74, -77, -83, -84, -86, -87, -89, -90, and HPV91) or high-risk clusters (HPV30, -34, -67, -69, and -85) (Table 1). Although this homology-based classification seems logical, it remains speculative until verified by epidemiological data. Inclusion of these HPV types in novel broad HPV assays in which all of these HPV types can be detected, like the novel microarray assay described here, may provide such epidemiological data.

In a small number of cases, no discrimination could be made between closely related HPV types with a single probe. In our experience, a minimum of a two-nucleotide mismatch in 20-mer hybridization probes was necessary for efficient discrimination between highly homologous HPV types. However, in most of these cases, discrimination between highly homologous HPV types can easily be established by using multiple probes in such a way that a specific combination of responding probes can be used to identify a specific HPV type. Although this may obscure certain specific combinations of multiple HPV infections, it seems a plausible way to deal with this. With an ever-expanding number of HPV types being reported, it seems almost inevitable, with any assay that has been developed so far, to encounter such a limitation. This may be particularly relevant for assays in which only a small amplicon is produced, as with the SPF10 assay (14). Although targeting only a small PCR amplicon may have certain advantages at the DNA amplification level, in the SPF10 assay an interprimer region of only 22 bp is available for making the discrimination between different HPV types. With this assay, multiple pairs of different HPV types differ by only 1 bp making it a challenge to reliably discriminate between these HPV types at the DNA hybridization level. In our novel assay, where the amplicon size varies between 112 and 258 bp, there is enough sequence variation to be able to discriminate between almost all HPV types.

We have limited ourselves here to the development of a novel assay for the detection and subtyping of mucosal genital HPV types. A total of 53 mucosal HPV types could be detected and identified, including 16 HPV types that are not included in many other previously reported assays (Table 4). Several of these additional HPV types were already detected in our clinical sample collection (e.g., HPV2, -27, -32, -67, and -85), giving a clear demonstration of the expanded applicability of this assay.

TABLE 4.

Overview of genital HPV types detected in several published broad HPV detection and typing assays

| HPV type | Reverse line blot with primer(s)a:

|

Microarray with primer pair GP5+-GP6+b | Dot blot with E-primersc | Novel microarrayd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP5+-GP6+e | MY09-MY11f | SPF10g | ||||

| 2 | x | |||||

| 3 | x | |||||

| 6 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 7 | x | |||||

| 10 | x | |||||

| 11 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 13 | x | |||||

| 16 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 18 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 26 | x | x | x | |||

| 27 | x | |||||

| 28 | x | |||||

| 29 | x | |||||

| 30 | x | x | ||||

| 31 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 32 | x | |||||

| 33 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 34 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 35 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 39 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 40 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 42 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 43 | x | x | x | |||

| 44 | x | x | x | x | ||

| 45 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 51 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 52 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 53 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 54 | x | x | x | x | ||

| 55 | x | x | x | |||

| 56 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 57 | x | x | x | x | ||

| 58 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| 59 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 61 | x | x | ||||

| 66 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 67 | x | |||||

| 68 | x | x | x | x | x | |

| 69 | x | x | ||||

| 70 | x | x | x | |||

| 71 | x | x | ||||

| 72 | x | x | ||||

| 73 | x | x | ||||

| 74 | x | x | ||||

| 77 | x | |||||

| 81 | x | |||||

| 82/MM4 | x | x | x | |||

| 83 | x | x | ||||

| 84 | x | x | ||||

| 85 | x | |||||

| 86 | x | |||||

| 87 | x | |||||

| 89/CP6108 | x | x | ||||

| 90 | x | |||||

| 91 | x | |||||

In conclusion, the microarray assay described here takes advantage of a straightforward approach for selection and design of PCR primers and probes to be used for detection and subtyping of HPV. The experimental setup, with a minimal request for expensive specialty equipment and the simple and affordable detection chemistry used, makes this approach accessible to all diagnostic laboratories with PCR facilities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, H. J., N. H. Cho, S. Y. Lee, I. H. Kim, C. Lee, S. J. Kim, M. S. Mun, S. H. Kim, and J. K. Jeong. 2003. Correlation of cervical carcinoma and precancerous lesions with human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes detected with the HPV DNA chip microarray method. Cancer 97:1672-1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho, N. H., H. J. An, J. K. Jeong, S. Kang, J. W. Kim, Y. T. Kim, and T. K. Park. 2003. Genotyping of 22 human papillomavirus types by DNA chip in Korean women: comparison with cytologic diagnosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutlee, F., P. Gravitt, J. Kornegay, C. Hankins, H. Richardson, N. Lapointe, H. Voyer, and E. Franco. 2002. Use of PGMY primers in L1 consensus PCR improves detection of human papillomavirus DNA in genital samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:902-907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Roda Husman, A. M., J. M. Walboomers, A. J. van den Brule, C. J. Meijer, and P. J. Snijders. 1995. The use of general primers GP5 and GP6 elongated at their 3′ ends with adjacent highly conserved sequences improves human papillomavirus detection by PCR. J. Gen. Virol. 76 (Pt. 4):1057-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gharizadeh, B., M. Kalantari, C. A. Garcia, B. Johansson, and P. Nyren. 2001. Typing of human papillomavirus by pyrosequencing. Lab. Investig. 81:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gravitt, P. E., C. L. Peyton, T. Q. Alessi, C. M. Wheeler, F. Coutlee, A. Hildesheim, M. H. Schiffman, D. R. Scott, and R. J. Apple. 2000. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:357-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravitt, P. E., C. L. Peyton, R. J. Apple, and C. M. Wheeler. 1998. Genotyping of 27 human papillomavirus types by using L1 consensus PCR products by a single-hybridization, reverse line blot detection method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3020-3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang, T. S., J. K. Jeong, M. Park, H. S. Han, H. K. Choi, and T. S. Park. 2003. Detection and typing of HPV genotypes in various cervical lesions by HPV oligonucleotide microarray. Gynecol. Oncol. 90:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs, M. V., A. M. de Roda Husman, A. J. van den Brule, P. J. Snijders, C. J. Meijer, and J. M. Walboomers. 1995. Group-specific differentiation between high- and low-risk human papillomavirus genotypes by general primer-mediated PCR and two cocktails of oligonucleotide probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:901-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs, M. V., P. J. Snijders, A. J. van den Brule, T. J. Helmerhorst, C. J. Meijer, and J. M. Walboomers. 1997. A general primer GP5+/GP6+-mediated PCR-enzyme immunoassay method for rapid detection of 14 high-risk and 6 low-risk human papillomavirus genotypes in cervical scrapings. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:791-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlsen, F., M. Kalantari, A. Jenkins, E. Pettersen, G. Kristensen, R. Holm, B. Johansson, and B. Hagmar. 1996. Use of multiple PCR primer sets for optimal detection of human papillomavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2095-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, C. J., J. K. Jeong, M. Park, T. S. Park, T. C. Park, S. E. Namkoong, and J. S. Park. 2003. HPV oligonucleotide microarray-based detection of HPV genotypes in cervical neoplastic lesions. Gynecol. Oncol. 89:210-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleter, B., L.-J. van Doorn, L. Schrauwen, A. Molijn, S. Sastrowijoto, J. ter Schegget, J. Lindeman, B. ter Harmsel, M. Burger, and W. Quint. 1999. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2508-2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleter, B., L.-J. van Doorn, J. ter Schegget, L. Schrauwen, K. van Krimpen, M. Burger, B. ter Harmsel, and W. Quint. 1998. Novel short-fragment PCR assay for highly sensitive broad-spectrum detection of anogenital human papillomaviruses. Am. J. Pathol. 153:1731-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longuet, M., S. Beaudenon, and G. Orth. 1996. Two novel genital human papillomavirus (HPV) types, HPV68 and HPV70, related to the potentially oncogenic HPV39. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:738-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorincz, A. T. 1992. Diagnosis of human papillomavirus infection by the new generation of molecular DNA assays. Clin. Immunol. Newsl. 12:123-128. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manos, M. M., T. Ting, D. K. Wright, A. J. Lewis, T. R. Broker, and S. M. Wolinsky. 1989. Use of polymerase chain reaction amplification for the detection of genital human papillomaviruses. Cancer Cells 7:209-214. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz, N., F. X. Bosch, S. de Sanjose, R. Herrero, X. Castellsague, K. V. Shah, P. J. F. Snijders, C. J. L. M. Meijer, et al. 2003. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:518-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson, J. H., G. A. Hawkins, K. Edlund, M. Evander, L. Kjellberg, G. Wadell, J. Dillner, T. Gerasimova, A. L. Coker, L. Pirisi, D. Petereit, and P. F. Lambert. 2000. A novel and rapid PCR-based method for genotyping human papillomaviruses in clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:688-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prinsen, C. F. M., C. H. W. Klaassen, and F. B. J. M. Thunnissen. 2003. Microarray as a model for quantitative visualization chemistry. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 11:168-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qu, W., G. Jiang, Y. Cruz, C. J. Chang, G. Y. Ho, R. S. Klein, and R. D. Burk. 1997. PCR detection of human papillomavirus: comparison between MY09/MY11 and GP5+/GP6+ primer systems. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1304-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unger, E. R. 2000. In situ diagnosis of human papillomaviruses. Clin. Lab. Med. 20:289-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Brule, A. J. C., R. Pol, N. Fransen-Daalmeijer, L. M. Schouls, C. J. L. M. Meijer, and P. J. F. Snijders. 2002. GP5+/6+ PCR followed by reverse line blot analysis enables rapid and high-throughput identification of human papillomavirus genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:779-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Doorn, L.-J., W. Quint, B. Kleter, A. Molijn, B. Colau, M.-T. Martin, Kravang-In, N. Torrez-Martinez, C. L. Peyton, and C. M. Wheeler. 2002. Genotyping of human papillomavirus in liquid cytology cervical specimens by the PGMY line blot assay and the SPF10 line probe assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:979-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vernon, S. D., E. R. Unger, and D. Williams. 2000. Comparison of human papillomavirus detection and typing by cycle sequencing, line blotting, and hybrid capture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:651-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ylitalo, N., T. Bergstrom, and U. Gyllensten. 1995. Detection of genital human papillomavirus by single-tube nested PCR and type-specific oligonucleotide hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1822-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]