Abstract

Whether and how gestational protein restriction (PR) affects placental development and function remain unknown. To test the hypothesis that PR can affect trophoblast differentiation in mid-and late pregnancy, rats were fed a 20% or an isocaloric 6% protein diet from Day 1 to 14 or 18 of pregnancy and effects of PR on trophoblast differentiation were determined by changes in expressions of marker gene(s) for trophoblast lineages. At Day 18 of pregnancy, PR increased expressions of Esrrb, Id1 and Id2 (trophoblast stem cell markers), decreased expressions of Ascl2 (spongiotrophblast cell marker) and Prl2c1 (trophoblast giant cell marker), but did not alter expressions of Gjb3 and Pcdh12 (glycogen cell markers) in the junctional zone (JZ). In the labyrinth zone (LZ), PR did not change expressions of Prl2b1 (trophoblast giant cell marker), Gcm1 and Syna (syncytiotrophoblast cell markers), but decrease expression of Ctsq (sinusoidal trophoblast giant cell marker). These results indicate that PR impairs the differentiation of trophoblast stem cell into spongiotrophoblast and trophoblast giant cells in JZ, and formation of sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells in LZ.

Keywords: Protein Restriction, Trophoblast, Trophoblast Differentiation, Gene Expression, Placenta, Junctional Zone, Labyrinth Zone

2. INTRODUCTION

Accumulating evidence that intrauterine growth restriction is associated with the adulthood health problems in the progeny (1–6). Malnutrition during pregnancy is one of the causes of IUGR (intrauterine growth restriction) (7,8). Dietary protein insufficiency occurs in large population due to the poverty especially in developing countries and certain ethnic groups due to varied social-economic limitations in developed countries (9,10). It has been established that offspring from dams with maternal protein restriction during gestation develop hypertension and cardiovascular diseases in adulthood in a gender- and time-dependent manner, with an earlier onset and more severe hypertension in males compared to females (11–17). Among the potential multiple factors responsible for the fetal programming on adulthood hypertension and cardiovascular disease, placenta may contribute largely to the process of programming, apparently because of its critical roles in hormone production and nutrient transport (8,18–21).

The two main functions of placenta are executed in two distinct placental zones in rodents, junctional zone (JZ) and labyrinth zone (LZ). The junctional zone in mature placenta mainly consists of trophoblast giant cells (TGC), spongiotrophoblast cells (STC) and glycogen cells. TGC play a versatile function as pregnancy advances, with secretion of variant agents including steroid hormones and prolactin related peptides at different stages (22). In the early pregnancy, TGC and their agents mediate blastocyst implantation, invasion and may regulate uterine decidulization. In the late pregnancy, a family of prolactins and steroid hormones secreted by TGC regulates vasculature remodeling and maternal adaptation to enhance the fetal growth (23,24). In addition to TGC, STC are endocrine cells synthesizing and releasing steroid and peptide hormones (25). Glycogen trophoblast cells are thought to be energy resources due to the accumulation of glycogen, but very little is known about their formation and function (26). The labyrinth zone, the zone near the chorionic plate, represents the main area of the placenta for maternal-fetal hemotrophic exchange (27). The labyrinth zone mainly contains trophoblast cells and fetal mesenchyme and vasculature. According to their fixed locations and distinct functions, labyrinth trophoblast subtypes include TGC, cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast cells (28). Labyrinth TGC include maternal blood canal and sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells which may regulate maternal vasculature remodeling and hormone and growth factor activity before they enter fetal/maternal circulation (23). Syncytiotrophoblast cells carry out the bidirectional hemotrophic exchange between maternal and fetal sides. Syncytiotrophoblast cells are formed by cytotrophoblast cell fusion, however, the process is unclear so far (28), but it is known that GCM1 initiates the formation of syncytiotrophoblast cell (29) and SYNA mediates the cell fusion (30). In general, the formation of these trophoblast lineages as well as the differentiation of trophoblast stem cells is complicated, as multiple genes get involved in this process, determined by knock-out, knock-down and transgenic techniques (23,28,31).

The variety of differentiated trophoblast lineages are originally derived from the same progenitor-trophoblast stem cell (TSC). To date, the differentiation of trophoblast stem cells into TGCs and other differentiated trophoblast lineages has been intensively studied in the trophoblast biology, with the application of mouse or rat trophoblast stem cell lines (32–34). Marker genes for trophoblast lineages have been widely used to represent the differentiation status of the trophoblast stem cells in vivo, ex vivo or in vitro (22,26,29,35,36). The frequently used marker genes and the references are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Marker genes for trophoblast stem cells and differentiated trophoblast lineages

| Gene | Trophoblast lineage | Placental zone | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esrrb, Id1, Id2 | Trophoblast stem cell | Junctional | (33,34,54,66,67) |

| Prl2c1 | Trophoblast giant cell | Junctional | (22,35,68–70) |

| Ascl2, Prl5a1 | Spongiotrophoblast cell | Junctional | (35,66,67) |

| Gjb3, Pcdh12 | Glycogen trophoblast cell | Junctional | (26,66) |

| Gcm1, Syna | Syncytiotrophoblast cell | Labyrinth | (33,34,36,66) |

| Prl2b1 | Trophoblast giant cell | Labyrinth | (24,53) |

| Ctsq | Sinusoidal trophoblast giant cell | Labyrinth | (22,36) |

Placental development is susceptible to external stimuli including nutritional disruptions. A microarray analysis with limited probe sets demonstrated that gestational protein restriction has deleterious effects on placental development, with altered expression of genes related to cell growth and metabolism, apoptosis and epigenetic control (37). Pregnant rats subjected to low protein diet has been widely used in the study of metabolic programming and associated offspring hypertension (38). Interestingly, the metabolic syndrome caused by maternal protein restriction can be related to the gender of offspring (38–40). Most studies have focused on the changes in nutrition transport in the labyrinth zone, in contrast, the effects of nutritional manipulation on the junctional zone has been largely ignored. It is known that low protein diet alters endocrine status in pregnant rats including elevated plasma levels of testosterone and estradiol (41) and reduced plasma levels of progesterone (42,43). The altered profiles of steroid hormones in response to gestational protein restriction may support the hypothesis that maternal protein restriction impairs the trophoblast differentiation in both juntional and labyrinth zones. As a pilot work in a series of studies to test this hypothesis, this study investigated the expression of marker genes for main cell types of trophoblasts in both JZ and LZ at mid- and late pregnant rats fed with or without protein restriction.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Animals

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch and were in accordance with those guidelines published by the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Virgin female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Houston, TX, USA) weighing between 175 and 225 g were mated with male Sprague-Dawley rats; conception was confirmed by observation of a vaginal copulation plug or the presence of sperm in the vaginal flush. This day was determined to be Day 1 of pregnancy. Pregnant rats were randomly divided into 2 dietary groups, housed individually, and fed a control (CT, 20% protein) or low protein (PR, 6% protein) diet until sacrificed on days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (n=10/diet/day of pregnancy). The isocaloric low-protein and normal-protein diets were obtained from Harlan Teklad (Cat. TD.90016 and TD.91352, respectively; Madison, WI, USA). The animals were housed in a room with a controlled temperature and a 12-hour light-dark cycle. During 8–10 am on days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, rats were anaesthetized with carbon dioxide. Maternal blood was collected by cardiac puncture into a BD vacuum tube containing K2-EDTA. Whole blood was centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant plasma was aliquoted, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Placentas and fetuses were isolated, blotted to remove fluids and blood, and weighed immediately. The labyrinth zone(LZ) and junctional zone (JZ) were dissected as described by Ain et al. (44). LZ and JZ were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

3.2. DNA extraction from fetal extraembryonic membrane and sex determination

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen fetal membranes and tails of adult male and female rats with Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Cat. 69504; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), and all procedures were performed according to the instruction manual. Sex determination was described previously (45). Males were determined by the presence of the Sry gene in genomic DNA with 1 microgram DNA template added in polymerase chain reactions (PCR) and females by no Sry gene amplification. The sequence of forward primers for the Sry gene was 5′-cacaagttggctcaacagaatc-3′ and reverse primer 5′-agctctactccagtcttgtccg-3′. One microgram genomic DNA from adult males and females was included as either a positive or negative control for the PCR procedure. PCR conditions were as follows: 1) 94°C for 5 min; 2) 94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 2.5 min, and 72°C for 1 min for 36 cycles; and 3) 72°C for 7 min.

3.3. RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNAs from frozen JZ and LZ tissues (n=6/diet/gender/day of pregnancy) were extracted using Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Cat. 74104; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The total RNAs were digested with RNA free DNase I (Cat. 79254; Qiagen), followed by a clean-up procedure. All procedures were performed according to the instruction manual. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 microgram of total RNA by RT in a total volume of 20 microliter using MyCycler Thermal Cycler (Cat. 170-9703; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with the following conditions: 1 cycle at 28°C for 15 min, 42°C for 50 min, and 95°C for 5 min.

3.4. Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time PCR detection was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Cat. 184-5096; Bio-Rad). The primers were designed using Primer 3 Version 4 or prepared according to the references and are shown in Table 2. Syber Green Supermix (Cat. 170-8882; Bio-Rad) was used for amplification of Esrrb, Id1, Id2, Ascl2, Prl5a1, Prl2c1, Gjb3, Pcdh12, Gcm1, Syna, Prl2b1 and Ctsq. The mixture of reaction reagents was incubated at 95°C for 10 min and cycled according to the following parameters: 95°C for 30 seconds and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. Negative control without cDNA was performed to test primer specificity.

Table 2.

Quantitative real-time PCR primers

| Gene | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) | GenBank accession No. | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esrrb* | TGCCTGAAGGGGATATCAAG | ACTCTGCACAGGCTCATCT | NM_001008516 | 140 |

| Id1* | CTGAACGGCGAGATCAGTG | GGAGTCCATCTGGTTCCTCA | NM_012797 | 105 |

| Id2 | CTCCAAGCTCAAGGAACTGG | GTGCTGCAGGATTTCCATCT | NM_013060 | 73 |

| Ascl2* | GATGGGGCAGATGTTTGACT | GCAAGAAACGCAGGTAGGTC | NM_031503 | 109 |

| Prl5a1* | TCCACACCAGACATTCCAGA | TTTCCAGGAAGCCAACATTC | NM_138527 | 143 |

| Prl2c1 | GCCAAGCACACACATTATGG | CATTCAGAGGGCTTTTCCAG | NM_001044271 | 76 |

| Gjb3* | TGTGAACCAGTACTCCACCGCATT | GCTGCCTGGTGTTACAGTCAAAGT | NM_019240 | 137 |

| Pcdh12 | CCTAAGGGACTCTGCTCACG | CAGTACAGCCAGGCAGATCA | NM_053944 | 75 |

| Gcm1 | CCCCAACAGGTTCCACTAGA | AGGGGAGTGGTACGTGACAG | NM_017186 | 122 |

| Syna | TCATGGGTGTCTCTGTCCAA | AGAATTTCCAGCCATTGACG | NM_001014771 | 111 |

| Prl2b1 | TGTCATCCTTGCAGTCAAGC | GGCAGCGAATCAGGGTATAA | NM_138861 | 66 |

| Ctsq | AACAGCTGGGGTAAACGATG | TGCACAGTGGTTGTTCCTGT | NM_139262 | 72 |

primers from reference (66)

Gapdh served as an endogenous control to standardize the amount of sample RNA added to a reaction. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for rat Gapdh (Rn01775763_g1) and supermix reagents were from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). The mixture of reaction reagents was incubated at 50°C for 2 min, heated to 95°C for 10 min, and cycled according to the following parameters: 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. The relative expression of target genes was calculated by use of the threshold cycle (CT) Gapdh /CT target gene.

3.5. Statistical analysis

All quantitative data were subjected to least-squares analysis of variance using the general linear models procedures of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data on placental weight and gene expression were analyzed for effects of day of pregnancy, diet, gender of placenta, and their interaction. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant, whereas a P value greater than 0.05 but less than 0.10 was considered a trend toward significance. Data in tissue weights are presented as means with standard errors, while data in gene expression is presented as least-squares means (LSM) with overall standard errors (SE).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Weights of junctional and labyrinth zones

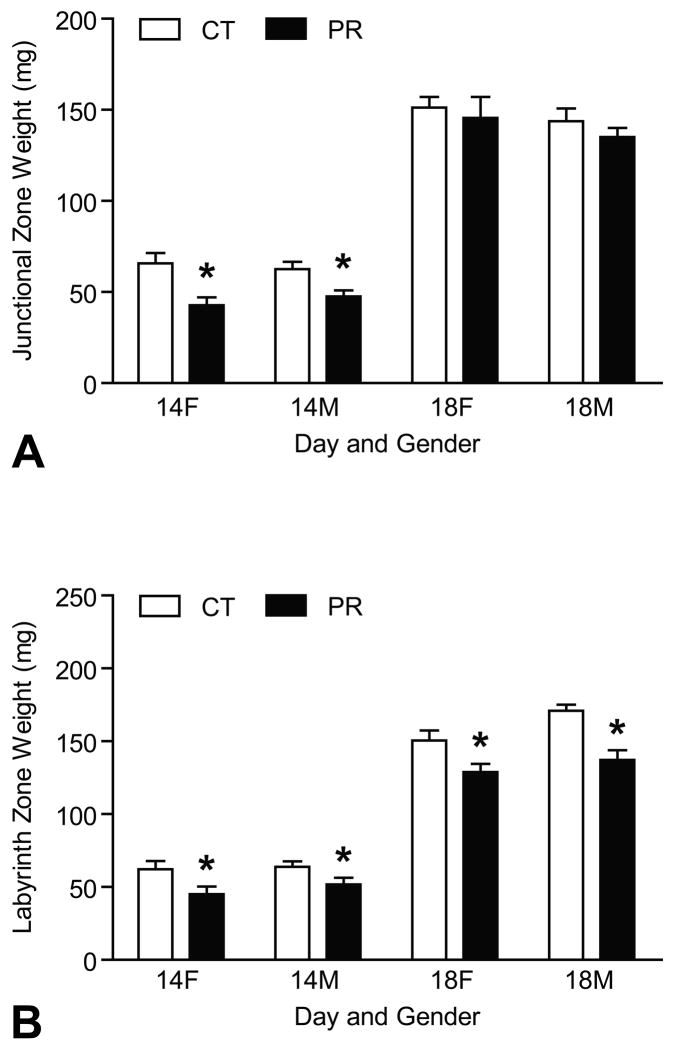

The weights of JZs of placentas for female and male fetuses (called female JZ, or male JZ in the context) were reduced by protein restriction at Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). Similarly, the weights of LZs of placentas for female and male fetuses (called female LZ, or male LZ in the context) were reduced by PR at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (P < 0.05) (Figure 1B). The details in the placental weights was published previously (45).

Figure 1.

Weights of junctional zones and labyrinth zones in rats with (PR) or without (CT) protein restriction at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy. A) Female and male JZ weights were reduced by protein restriction at Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.05). B) Female and male LZ weights were reduced by PR at both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (P < 0.05).

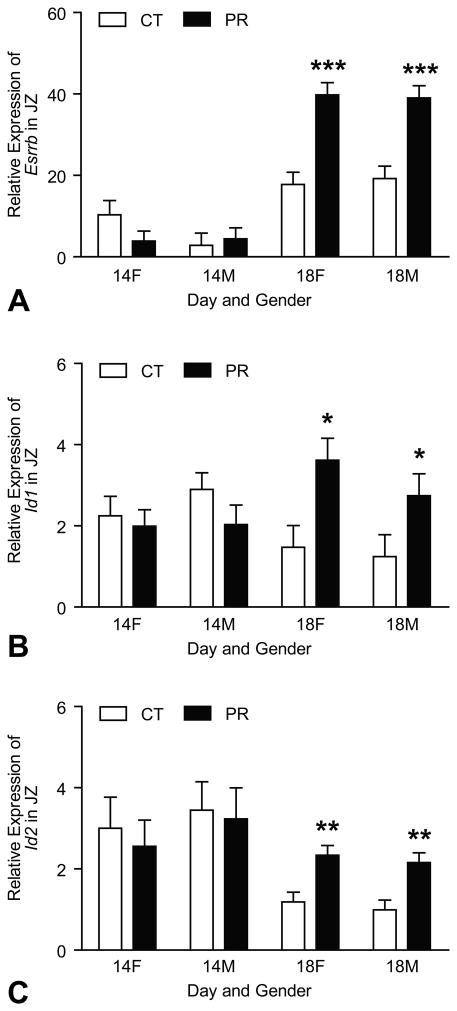

4.2. Expressions of marker genes for trophoblast stem cells in JZ were increased by protein restriction

At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Esrrb in JZ were not affected by both gender and diet. At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Esrrb were increased by 2.2- and 2.0-fold (P < 0.001) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively(Figure 2A). Similarly, the expressions of other TS markers, Id1 and Id2, were not affected by both gender and diet in JZ. At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Id1 were increased by 2.5- and 2.2-fold (P < 0.05) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively (Figure 2B); the mRNA levels of Id2 were increased by 2.0- and 2.2-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Expressions of Esrrb, Id1 and Id2 in the rat junctional zone (JZ). A) At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Esrrb were increased by 2.2- and 2.0-fold (P < 0.001) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively. B) At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Id1 were increased by 2.5- and 2.2-fold (P < 0.05) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively. C) At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Id2 were increased by 2.0- and 2.2-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs compared to those in controls, respectively.*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

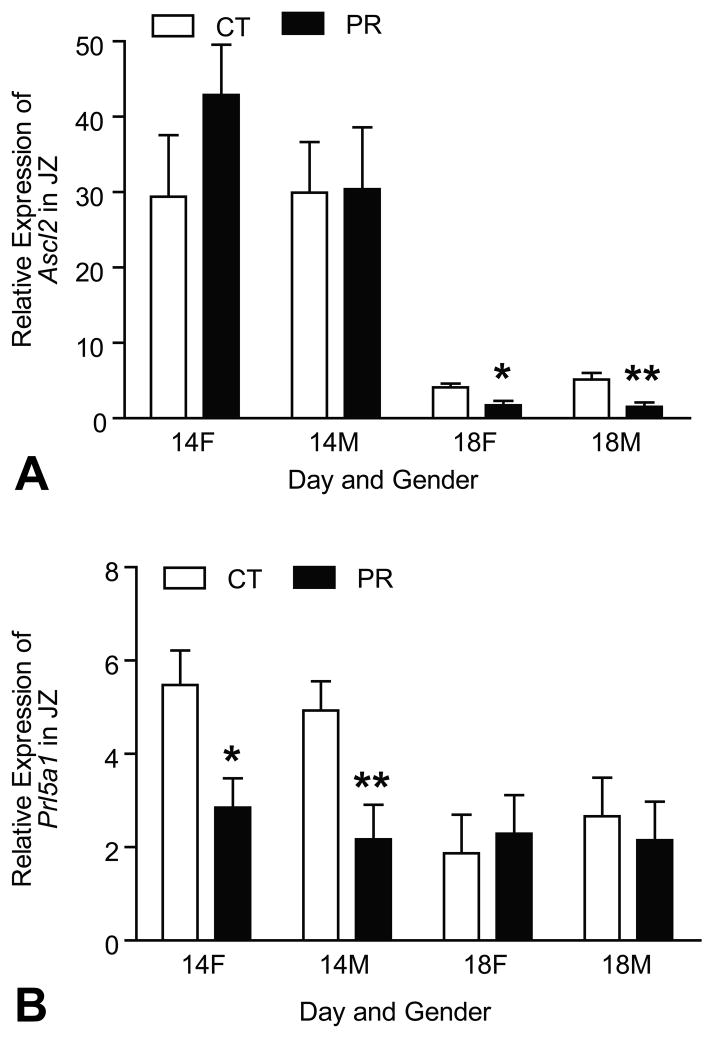

4.3. Expressions of marker genes for spongiotrophoblast cells in JZ was decreased by protein restriction

The mRNA levels of Ascl2 and Prl5a1 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the decreased levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.001)(Figure 3A, 3B). At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ascl2 were not affected by gender and diet; at Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ascl2 were decreased by 2.4- and 3.4-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively, compared to those in controls (Figure 3A). In contrast, at Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl5a1 was decreased by 1.9- and 2.3-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively, compared to those in controls, but at Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl5a1 in JZs were not affected by gender and diet (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Expressions of Ascl2 and Prl5a1 in the rat junctional zone (JZ). A) At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ascl2 were not affected by gender and diet; at Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ascl2 was decreased by 2.4- and 3.4-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively, compared to those in controls. B) At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl5a1 was decreased by 1.9- and 2.3-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively, compared to those in controls, but not affected at Day 18 of pregnancy. **P < 0.01

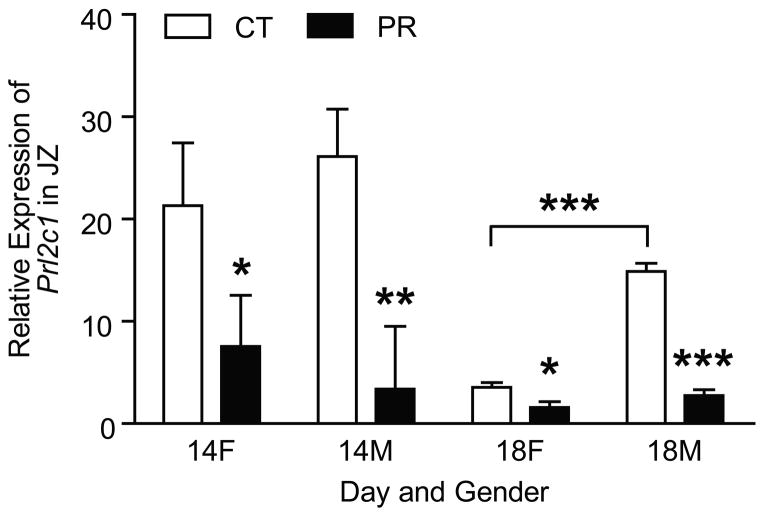

4.4. Expression of marker gene for trophoblast giant cells in JZ was decreased by protein restriction

At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 were decreased by 2.8-fold (P < 0.05) and 7.7-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively (Figure 4). At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 were decreased by 2.2-fold (P < 0.05) and 5.4-fold (P < 0.001); within control group, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 in male JZs were 4.2-fold higher (P < 0.001) than those in female JZs; within PR group, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 in male JZs tended to be higher than those in female JZs (P = 0.06) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of Prl2c1 in the rat junctional zone (JZ). At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 were decreased by 2.8-fold (P < 0.05) and 7.7-fold (P < 0.01) in PR female and male JZs, respectively. At Day 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 were decreased by 2.2-fold (P < 0.05) and 5.4-fold (P < 0.001); within control group, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 in male JZs were 4.2-fold higher (P < 0.001) than those in female JZs; within PR group, the mRNA levels of Prl2c1 in male JZs tended to be higher than those in female JZs (P = 0.06). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

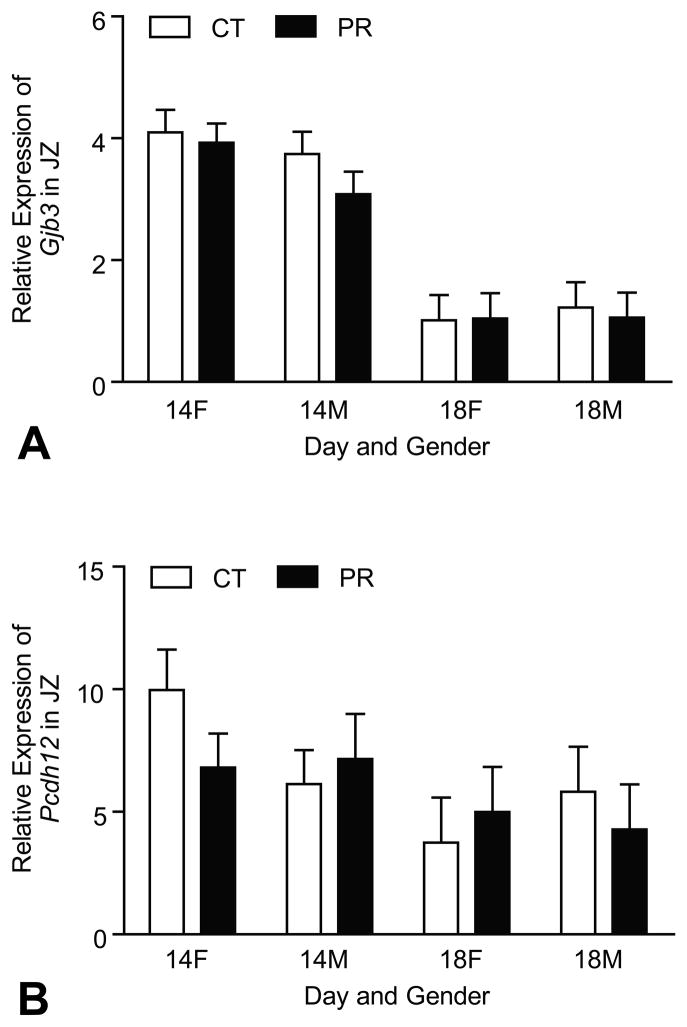

4.5. Expressions of marker genes for glycogen trophoblast cells in JZ were not affected by protein restriction

The mRNA levels of Gjb3 and Pcdh12 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the decreased levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001, P < 0.05). However, the expressions of these two genes in JZ were not affected by gender and diet (Figure 5A, 5B).

Figure 5.

Expressions of Gjb3 and Pcdh12 in the rat junctional zone (JZ). A) The mRNA levels of Gjb3 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the decreased levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001). The expressions of these two genes in JZ were not affected by gender and diet. B) The mRNA levels of Pcdh12 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the decreased levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.05). However, the expressions of these two genes in JZ were not affected by gender and diet.

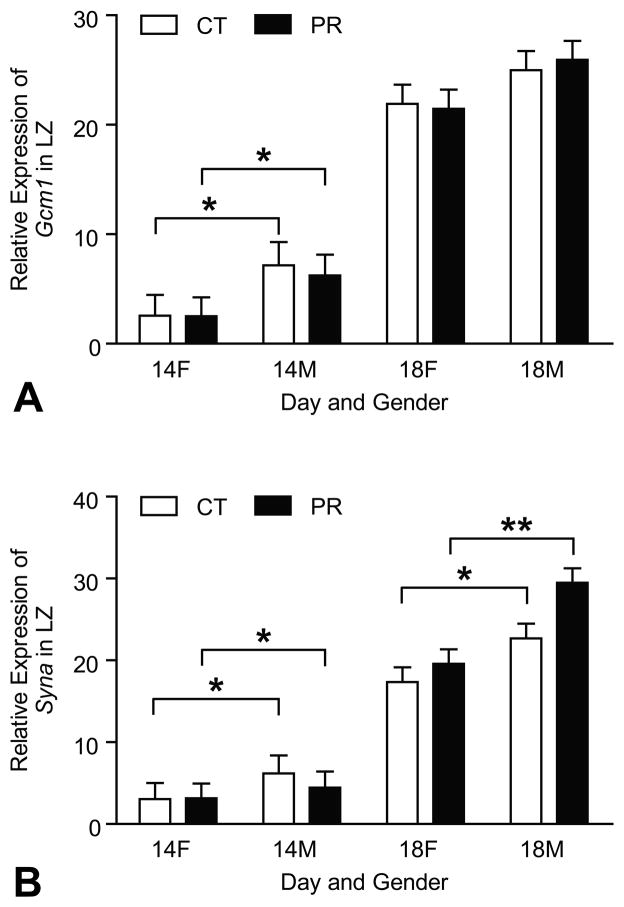

4.6. Expressions of marker genes for syncytiotrophoblast cells in LZ were not changed by protein restriction

The mRNA levels of Gcm1 and Syna were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001) (Figure 6A, 6B). At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Gcm1 in male LZs were higher (P < 0.05) than those in female LZs in both PR and control groups (Figure 6A). At Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Syna in male LZs were higher (P < 0.05) than those in female LZs in both PR and control groups (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Expressions of Gcm1 and Syna in the rat junctional zone (LZ). A) The mRNA levels of Gcm1 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001). At Day 14 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Gcm1 in male LZs were higher (P < 0.05) than those in female LZs in both PR and control groups. B) The mRNA levels of Gcm1 and Syna were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001). At Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Syna in male LZs were higher (P < 0.05) than those in female LZs in both PR and control groups. *P < 0.05

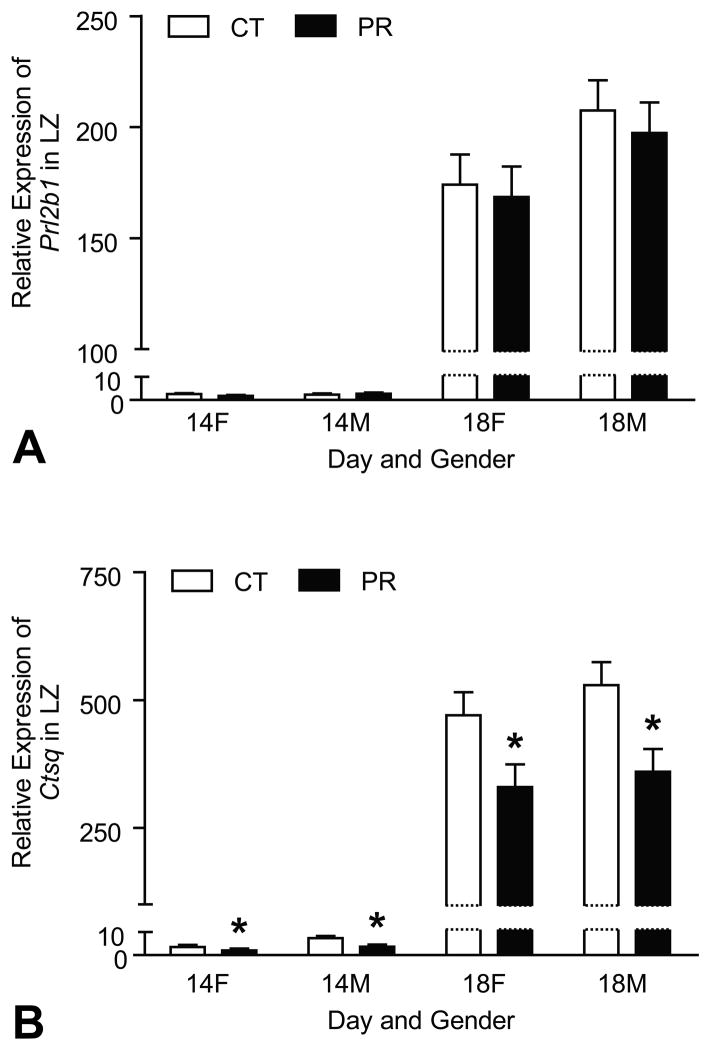

4.7. Expression of marker gene for sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells in LZ was reduced by protein restriction

The mRNA levels of Prl2b1 (marker for overall trophoblast giant cells in LZ) and Ctsq (marker for sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells) were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001) (Figure 7A, 7B). At both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Prl2b1 were not affected by gender and diet (Figure 7A). At Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ctsq in both male and female LZs were reduced (P < 0.05) by PR compared to their control LZs, respectively (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Expressions of Prl2b1 and Ctsq in the rat junctional zone (LZ). A) The mRNA levels of Prl2b1 were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001), but they were not affected by gender and diet. B) The mRNA levels of Ctsq were affected by Day of pregnancy with the remarkably elevated levels at Day 18 of pregnancy compared to Day 14 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001). At Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, the mRNA levels of Ctsq in both male and female LZs were reduced (P < 0.05) by PR compared to their control LZs, respectively. *P < 0.05

5. DISCUSSION

This study, to our knowledge, reports for the first time that gestational protein restriction may affect the differentiation of trophoblast stem cells in junctional zone and that the differentiation into trophoblast giant cells may be more susceptible for dietary protein restriction during pregnancy. These novel findings may explain the altered hormonal profiles by gestational protein restriction (40,42,43), and also open a new window for exploring the mechanisms responsible for the placental programming on adulthood hypertension and other health problems.

The results of our study indicated that gestational protein restriction may not impede the proliferation of trophoblast stem cells. Three marker genes for the trophoblast stem cells, Esrrb, Id1 and Id2 were assessed in this study, and all the three genes shared the same pattern of changes with the advancement of pregnancy (Figure 2). Their expressions were uniformly increased in the rats fed with low protein diet at Day 18 of pregnancy when the placenta and fetus undergo rapid growth (23,46), whereas the expressions of Id1 and Id2 were declined from Day 14 to 18 of pregnancy (Figure 2B, 2C). In normal pregnancy, these gene expressions are decreased with the development of placenta (28,36). However, the weights of the junctional zones are comparable in PR and control groups at Day 18 of pregnancy (Figure 1A). Therefore, these elevated expressions of TSC marker gene indicate the proportion of trophoblast stem cells in the junctional zones was increased while the differentiated trophoblast cells account for a less proportion in junctional zone compared to that in controls. As a result, the proliferation of trophoblast stem cells was increased by PR while the differentiation of trophoblast stem cells was impaired by PR.

In the development of the junctional zone, gestational protein restriction may impair the differentiation of trophoblast stem cell into trophoblast giant cells and spongiotrophoblast cells. The expression of Prl2c1 in JZ was reduced by PR at both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (Figure 4). Similarly, expressions of Ascl2 and Prl5a1 were decreased by PR at Day 18 and 14 of pregnancy, respectively (Figure 3A, 3B). Trophoblast giant cells and spongiotrophoblast cells are the main cell types in junctional zone, and are critical for placental function as an endocrine organ during pregnancy (25). In the early blastocyst stage, the earliest cell differentiation event is the formation of trophectoderm, while the TGC is the first trophoblast lineage derived from the stem cells in the trophectoderm and form the chrionvitelline placenta (47). Anatomically the junctional zone lies between the maternal deciduas and the labyrinth zone, and thus, TGC as well as spongiotrophoblast cells are exposed to maternal blood born factors. Therefore, it is possible that the formation of TGC be more susceptible to the maternal disruptions. With gestational protein restriction, the reduced number of TGC and spongiotrophoblast cells altered the steroid hormone production in the junctional zone, and consequently, the maternal hormonal profile was changed (40,42,43). In contrast to TGC and spongiotrophoblast cells, the differentiation of TSC into glycogen cells was apparently not affected by gestational protein restriction, because the mRNA levels of Gjb3 and Pdch12, the exclusive marker gene for the glycogen cells (26), did not change in PR group (Figure 5A, 5B). In rats, the formation of the glycogen cells occurs around Day 12 of pregnancy, and the number of glycogen cells is dynamic with the advancement of the pregnancy, accounting for 50% of JZ volume at Days 12–16, 25% at Days 17–18 and a little at Days 19–21 of pregnancy (48). As the loss of glycogen cells is a natural process in rodent placenta (26,48) and it was not accelerated in the PR JZs in this study, it is possible that the abnormal apoptosis and necrosis does not occur in PR JZs, and thus, the reduced numbers of TGC and SPT in PR JZs are due to the impaired differentiation rather than the loss of these cells.

Unlike the altered trophoblast cell differentiation in junctional zone, syncytiotrophobast cells, the main trophoblast lineage in LZ were not affected by protein restriction, demonstrated by the comparable mRNA levels of Gcm1 and Syna in PR and control groups (Figure 6A, 6B). Gcm1 regulates the initiation of formation of syncytiotrophoblast from cytotrophoblast (49), and the genetic deletion of Gcm1 caused embryonic lethality due to the failure in formation of syncytiotrophoblast and LZ (29). Syna promotes the fusion of cytotrophoblast cells and formation of syncytiotrophoblast cells (30,50). However, in PR group, the velocity of LZ growth from Day 14 to Day 18 of pregnancy is comparable to that in control group, while the LZ weights were reduced by PR at both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (Figure 1B). This may indicate that the rate of formation of syncytiotrophoblast is not affected by PR, but the absolute number of syncytiotrophoblast cells was reduced by PR. Together with the reduced expression of amino acid transporters in LZ by PR (51,52), the reduced absolute number of syncytiotrophoblast cells may be responsible for the IUGR. In contrast, the sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells were impaired by PR, as the expression of specific marker Ctsq was decreased by PR at both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (Figure 7B). Interestingly, the expression of Prl2b1, the marker for labyrinth TGCs (24,53), were not affected by PR (Figure 7A). These may indicate that other type of labyrinth TGCs, maternal blood canal TGCs, are not reduced by PR. During mid-and late gestation, there is an extremely rapid formation of sinusoidal giant trophoblast cells as well as other TGCs in the LZ as demonstrated by remarkably increased expression of Ctsq and Prl2b1, respectively from Day 14 to 18 of pregnancy (Figure 7A, 7B). In the PR group, the sinusoidal giant trophoblast cells were decreased during this period of time, perhaps due to the fact that these cells are immersed in the maternal blood circulation (22,28), and thus, the formation of sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells may be susceptible to the maternal stimuli. The function of sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells was thought to modulate the activities of hormones and growth factors before they enter fetal/maternal blood circulation(23). Therefore, the impaired sinusoidal TGCs in labyrinth zone may contribute to the formation of IUGR.

At present, it is poorly understood how the protein restriction affect the differentiation of trophoblast cells. Our previous study demonstrated that gestational protein restriction changed the plasma levels of amino acids in dams, with decreased essential amino acids and increased non-essential amino acids (45). Among these essential amino acids during pregnancy, the decreased levels of arginine and leucine may be responsible for the impaired differentiation of trophoblast cells. Recently, it has been reported that phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) pathway plays a critical role in the trophoblast cell differentiation (54). In mice (55,56), sheep (57,58)and pigs (59), arginine and/or leucine can stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of trophectoderm cells via mTOR signaling pathway. Moreover, mTOR signaling pathway and PI3K pathway converge in multiple components including protein kinase B (AKT) in trophoblast cells. Therefore, the altered amino acid profile in response to gestational protein restriction may impair the trophoblast cell differentiation. In addition, the altered IGF2 system (IGF2 and its receptors and binding proteins) in rat placenta in response to protein restriction (45) and possibly reduced maternal plasma insulin (51) may affect trophoblast differentiation possibly via mTOR signaling pathway (57); protein restriction altered the maternal steroid hormone profile including increased testosterone and estradiol (40), decreased progesterone (60,61), may affect trophoblast differentiation; protein restriction altered the availability of amino acids, substrates for the one-carbon groups in DNA methylation, with reduced methionine and threonine and increased glycine and serine (45), may regulate the expression of genes related to trophoblast differentiation via DNA methylation (7,23,37,49). In light of the foregoing, we propose that mulitiple maternal interruptions during the pregnancy may cause the placental programming partly, if not all by interfering the trophoblast differentiation.

Pregnant rats subjected to low protein diet have been widely used in the study of fetal programming on hypertension and metabolic diseases, albeit the percentage of protein in low protein diets is in a wide range of 4 to 10 percent (11–17). Most of these studies stated that the isocaloric diets (identical calories per gram in low protein and control diet) were provided ad libitum to the dams and the amount of diet consumed by rats was comparable between low protein diet group and control group. In the current study, we also assumed that the amount of diet consumed in these two groups is similar and thus, the main factor involved in the study was only protein restriction. The constructive comments from nutritionists suggest that the amount of diet consumed in the two groups may not be identical, and correspondingly the amount of other components in diet including vitamins and minerals may not be identical in the two groups, which may also contribute the trophoblast differentiation, because it has been reported that vitamins (62,63) and folic acid (64,65) are able to regulate trophoblast differentiation and proliferation. A more thorough study on the dietary intake in pregnant rats in response to protein restriction may provide useful data to validate this widely-used animal model and elucidate the predominance of protein restriction over other nutrients in the process of fetal programming.

In this study, we took advantage of the marker genes for trophoblast cell type to explore the differentiation of trophoblast stem cells in response to protein restriction. These marker genes have been widely used in the studies on trophoblast differentiation in vivo, ex vivo or in vitro (22,26,29,35,36). The specificity of the marker genes for different trophoblast lineages have been tested in other studies mainly by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry (22,23,26,28,35,36,54,66,67). Utilizing quantitative real-time PCR, we were able to study the developmental status of trophoblast stem cells and the effects of gestational protein restriction within short period of time.

In summary, this study demonstrated that gestational protein restriction affects the trophoblast cell differentiation, with a decrease in trophoblast giant cells and spongiotrophoblast cells in the junctional zone and sinusoidal giant trophoblast cells in the labyrinth zone in rat placenta. This study indicates the fetal growth retardation in protein restricted mothers may be related to the placental programming involving altered trophoblast cell differentiation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Michael J Soares University of Kansas Medical Center for comments and discussion and Ms. Elizabeth A. Powell for editorial work on this manuscript and administrative support. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL102866 and R01HL58144.

Abbreviations

- IUGR

intrauterine growth restriction

- PR

protein restriction

- TGC

trophoblast giant cells

- STC

spongiotrophoblast cells

- JZ

junctional zone

- LZ

labyrinth zone

- TSC

trophoblast stem cells

- Esrrb

estrogen-related receptor beta

- Id1

inhibitor of DNA binding 1

- Id2

inhibitor of DNA binding 2

- Prl2c1

Prolactin family 2, subfamily c, member 1

- Ascl2

achaete-scute complex homolog 2

- prl5a1

prolactin family 5, subfamily a, member 1

- Gjb3

gap junction protein, beta 3, 31kD

- Pcdh12

protocadherin 12

- Gcm1

glial cells missing homolog 1

- Syna

syncytin a

- Prl2b1

prolactin family 2, subfamily b, member 1

- Ctsq

cathepsin Q

References

- 1.Barker DJ. The fetal origins of adult hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1992;10(7):S39–S44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ. The fetal origins of diseases of old age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46(Suppl 3):S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ. Fetal growth and adult disease. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(4):275–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb13719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ. The intrauterine origins of cardiovascular disease. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1993;82(Suppl 391):93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker DJ. In utero programming of cardiovascular disease. Theriogenology. 2000;53(2):555–574. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker DJ. Adult consequences of fetal growth restriction. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(2):270–283. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200606000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu G, Bazer FW, Cudd TA, Meininger CJ, Spencer TE. Maternal nutrition and fetal development. J Nutr. 2004;134(9):2169–2172. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu G, Bazer FW, Wallace JM, Spencer TE. Board-invited review: intrauterine growth retardation: implications for the animal sciences. J Anim Sci. 2006;84(9):2316–2337. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller O, Krawinkel M. Malnutrition and health in developing countries. CMAJ. 2005;173(3):279–286. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad AS. Zinc deficiency in women, infants and children. J Am Coll Nutr. 1996;15(2):113–120. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1996.10718575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gangula PR, Reed L, Yallampalli C. Antihypertensive effects of flutamide in rats that are exposed to a low-protein diet in utero. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development. 2000;127(19):4195–4202. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.19.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Maternal protein restriction influences the programming of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Nutr. 1996;126(6):1578–1585. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.6.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci. 1999;64(11):965–974. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Maternal low-protein diet in rat pregnancy programs blood pressure through sex-specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288(1):R85–R90. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00435.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Sex-specific effects of prenatal low-protein and carbenoxolone exposure on renal angiotensin receptor expression in rats. Hypertension. 2005;46(6):1374–1380. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188702.96256.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins AJ, Wilkins A, Cunningham C, Perry VH, Seet MJ, Osmond C, Eckert JJ, Torrens C, Cagampang FR, Cleal J, Gray WP, Hanson MA, Fleming TP. Low protein diet fed exclusively during mouse oocyte maturation leads to behavioural and cardiovascular abnormalities in offspring. J Physiol. 2008;586(8):2231–2244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godfrey K, Robinson S. Maternal nutrition, placental growth and fetal programming. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57(1):105–111. doi: 10.1079/pns19980016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godfrey KM. The role of the placenta in fetal programming-a review. Placenta. 2002;23(Suppl A):S20–S27. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones HN, Powell TL, Jansson T. Regulation of placental nutrient transport--a review. Placenta. 2007;28(8–9):763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myatt L. Placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. J Physiol. 2006;572(Pt 1):25–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.104968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons DG, Fortier AL, Cross JC. Diverse subtypes and developmental origins of trophoblast giant cells in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2007;304(2):567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu D, Cross JC. Development and function of trophoblast giant cells in the rodent placenta. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54(2–3):341–354. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082768dh. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soares MJ, Konno T, Alam SM. The prolactin family: effectors of pregnancy-dependent adaptations. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18(3):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares MJ, Chapman BM, Rasmussen CA, Dai G, Kamei T, Orwig KE. Differentiation of trophoblast endocrine cells. Placenta. 1996;17(5–6):277–289. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coan PM, Conroy N, Burton GJ, Ferguson-Smith AC. Origin and characteristics of glycogen cells in the developing murine placenta. Dev Dyn. 2006;235(12):3280–3294. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georgiades P, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ. Comparative developmental anatomy of the murine and human definitive placentae. Placenta. 2002;23(1):3–19. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmons DG, Cross JC. Determinants of trophoblast lineage and cell subtype specification in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2005;284(1):12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anson-Cartwright L, Dawson K, Holmyard D, Fisher SJ, Lazzarini RA, Cross JC. The glial cells missing-1 protein is essential for branching morphogenesis in the chorioallantoic placenta. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):311–314. doi: 10.1038/77076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mi S, Lee X, Li X, Veldman GM, Finnerty H, Racie L, LaVallie E, Tang XY, Edouard P, Howes S, Keith JC, Jr, McCoy JM. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 2000;403(6771):785–789. doi: 10.1038/35001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Renaud SJ, Karim Rumi MA, Soares MJ. Review: Genetic manipulation of the rodent placenta. Placenta. 2011;32(Suppl 2):S130–S135. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sahgal N, Canham LN, Canham B, Soares MJ. Rcho-1 trophoblast stem cells: a model system for studying trophoblast cell differentiation. Methods Mol Med. 2006;121:159–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selesniemi K, Reedy M, Gultice A, Guilbert LJ, Brown TL. Transforming growth factor-beta induces differentiation of the labyrinthine trophoblast stem cell line SM10. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(6):697–711. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selesniemi KL, Reedy MA, Gultice AD, Brown TL. Identification of committed placental stem cell lines for studies of differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14(5):535–547. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons DG, Rawn S, Davies A, Hughes M, Cross JC. Spatial and temporal expression of the 23 murine Prolactin/Placental Lactogen-related genes is not associated with their position in the locus. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:352. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons DG, Natale DR, Begay V, Hughes M, Leutz A, Cross JC. Early patterning of the chorion leads to the trilaminar trophoblast cell structure in the placental labyrinth. Development. 2008;135(12):2083–2091. doi: 10.1242/dev.020099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gheorghe CP, Goyal R, Holweger JD, Longo LD. Placental gene expression responses to maternal protein restriction in the mouse. Placenta. 2009;30(5):411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kautzky-Willer A, Handisurya A. Metabolic diseases and associated complications: sex and gender matter! Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39(8):631–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zambrano E, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Bautista CJ, Deas M, Guillen L, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. Sex differences in transgenerational alterations of growth and metabolism in progeny (F2) of female offspring (F1) of rats fed a low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation. J Physiol. 2005;566(Pt 1):225–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zambrano E, Bautista CJ, Deas M, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Gonzalez-Zamorano M, Ledesma H, Morales J, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. A low maternal protein diet during pregnancy and lactation has sex- and window of exposure-specific effects on offspring growth and food intake, glucose metabolism and serum leptin in the rat 69. J Physiol. 2006;571(Pt 1):221–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zambrano E, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Garcia-Becerra R, Boeck L, Diaz L, Menjivar M, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. A maternal low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation in the rat impairs male reproductive development. J Physiol. 2005;563(Pt 1):275–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henricks DM, Bailey LB. Effect of dietary protein restriction on hormone status and embryo survival in the pregnant rat. Biol Reprod. 1976;14(2):143–150. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod14.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulay S, Varma DR, Solomon S. Influence of protein deficiency in rats on hormonal status and cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors in maternal and fetal tissues. J Endocrinol. 1982;95(1):49–58. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0950049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ain R, Konno T, Canham LN, Soares MJ. Phenotypic analysis of the rat placenta. In: Soares MJ, Hunt JS, editors. Methods in Molecular Medicine, Vol.121: Placenta and Thophoblast: Methods and Protocols. Vol. 1. Humana Press; NJ: 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao H, Sathishkumar KR, Yallampalli U, Balakrishnan M, Li X, Wu G, Yallampalli C. Maternal protein restriction regulates IGF2 system in placental labyrinth. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2012;4:1434–1450. doi: 10.2741/472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sikov MR, Thomas JM. Prenatal growth of the rat. Growth. 1970;34(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gardner RL, Papaioannou VE, Barton SC. Origin of the ectoplacental cone and secondary giant cells in mouse blastocysts reconstituted from isolated trophoblast and inner cell mass. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1973;30(3):561–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Rijk EP, van EE, Flik G. Pregnancy dating in the rat: placental morphology and maternal blood parameters. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30(2):271–282. doi: 10.1080/019262302753559614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hughes M, Dobric N, Scott IC, Su L, Starovic M, St-Pierre B, Egan SE, Kingdom JC, Cross JC. The Hand1, Stra13 and Gcm1 transcription factors override FGF signaling to promote terminal differentiation of trophoblast stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;271(1):26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dupressoir A, Marceau G, Vernochet C, Benit L, Kanellopoulos C, Sapin V, Heidmann T. Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in Muridae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(3):725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406509102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansson N, Pettersson J, Haafiz A, Ericsson A, Palmberg I, Tranberg M, Ganapathy V, Powell TL, Jansson T. Down-regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction in rats fed a low protein diet. J Physiol. 2006;576(Pt 3):935–946. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malandro MS, Beveridge MJ, Kilberg MS, Novak DA. Effect of low-protein diet-induced intrauterine growth retardation on rat placental amino acid transport. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(1 Pt 1):C295–C303. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dai G, Wang D, Liu B, Kasik JW, Muller H, White RA, Hummel GS, Soares MJ. Three novel paralogs of the rodent prolactin gene family. J Endocrinol. 2000;166(1):63–75. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kent LN, Konno T, Soares MJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase modulation of trophoblast cell differentiation. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez IM, Martin PM, Burdsal C, Sloan JL, Mager S, Harris T, Sutherland AE. Leucine and arginine regulate trophoblast motility through mTOR-dependent and independent pathways in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin PM, Sutherland AE. Exogenous amino acids regulate trophectoderm differentiation in the mouse blastocyst through an mTOR-dependent pathway. Dev Biol. 2001;240(1):182–193. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bazer FW, Song G, Kim J, Erikson DW, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Gao H, Carey SM, Spencer TE, Wu G. Mechanistic mammalian target of rapamycin (MTOR) cell signaling: Effects of select nutrients and secreted phosphoprotein 1 on development of mammalian conceptuses. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim JY, Burghardt RC, Wu G, Johnson GA, Spencer TE, Bazer FW. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. VII. Effects of arginine, leucine, glutamine, and glucose on trophectoderm cell signaling, proliferation, and migration. Biol Reprod. 2011;84(1):62–69. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kong X, Tan B, Yin Y, Gao H, Li X, Jaeger LA, Bazer FW, Wu G. l-Arginine stimulates the mTOR signaling pathway and protein synthesis in porcine trophectoderm cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henricks DM, Bailey LB. Effect of dietary protein restriction on hormone status and embryo survival in the pregnant rat. Biol Reprod. 1976;14(2):143–150. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod14.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mulay S, Varma DR, Solomon S. Influence of protein deficiency in rats on hormonal status and cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors in maternal and fetal tissues. J Endocrinol. 1982;95(1):49–58. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0950049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pospechova K, Rozehnal V, Stejskalova L, Vrzal R, Pospisilova N, Jamborova G, May K, Siegmund W, Dvorak Z, Nachtigal P, Semecky V, Pavek P. Expression and activity of vitamin D receptor in the human placenta and in choriocarcinoma BeWo and JEG-3 cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;299(2):178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tarrade A, Rochette-Egly C, Guibourdenche J, Evain-Brion D. The expression of nuclear retinoid receptors in human implantation. Placenta. 2000;21(7):703–710. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeLoia JA, Stewart-Akers AM, Creinin MD. Effects of methotrexate on trophoblast proliferation and local immune responses. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(4):1063–1069. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kulkarni A, Dangat K, Kale A, Sable P, Chavan-Gautam P, Joshi S. Effects of altered maternal folic acid, vitamin B12 and docosahexaenoic acid on placental global DNA methylation patterns in Wistar rats. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asanoma K, Rumi MA, Kent LN, Chakraborty D, Renaud SJ, Wake N, Lee DS, Kubota K, Soares MJ. FGF4-dependent stem cells derived from rat blastocysts differentiate along the trophoblast lineage. Dev Biol. 2011;351(1):110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nadra K, Anghel SI, Joye E, Tan NS, Basu-Modak S, Trono D, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Differentiation of trophoblast giant cells and their metabolic functions are dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(8):3266–3281. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3266-3281.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alam SM, Ain R, Konno T, Ho-Chen JK, Soares MJ. The rat prolactin gene family locus: species-specific gene family expansion. Mamm Genome. 2006;17(8):858–877. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adamson SL, Lu Y, Whiteley KJ, Holmyard D, Hemberger M, Pfarrer C, Cross JC. Interactions between trophoblast cells and the maternal and fetal circulation in the mouse placenta. Dev Biol. 2002;250(2):358–373. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)90773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee SJ, Talamantes F, Wilder E, Linzer DI, Nathans D. Trophoblastic giant cells of the mouse placenta as the site of proliferin synthesis. Endocrinology. 1988;122(5):1761–1768. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-5-1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]