Abstract

Background and objectives

CKD–mineral and bone disorders (CKD-MBD) measures contribute to cardiovascular morbidity in patients with CKD. Among these, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 and its coreceptor Klotho may exert direct effects on vascular and myocardial tissues. Klotho exists in a membrane-bound and a soluble form (sKlotho). Recent experimental evidence suggests sKlotho has vasculoprotective functions.

Design, settings, participants, & measurements

Traditional and novel CKD-MBD variables were measured among 444 patients with CKD stages 2–4 recruited between September 2008 and November 2012 into the ongoing CARE FOR HOMe study. Across tertiles of baseline sKlotho and FGF-23, the incidence of two distinct combined end points was analyzed: (1) the first occurrence of an atherosclerotic event or death from any cause and (2) the time until hospital admission for decompensated heart failure or death from any cause.

Results

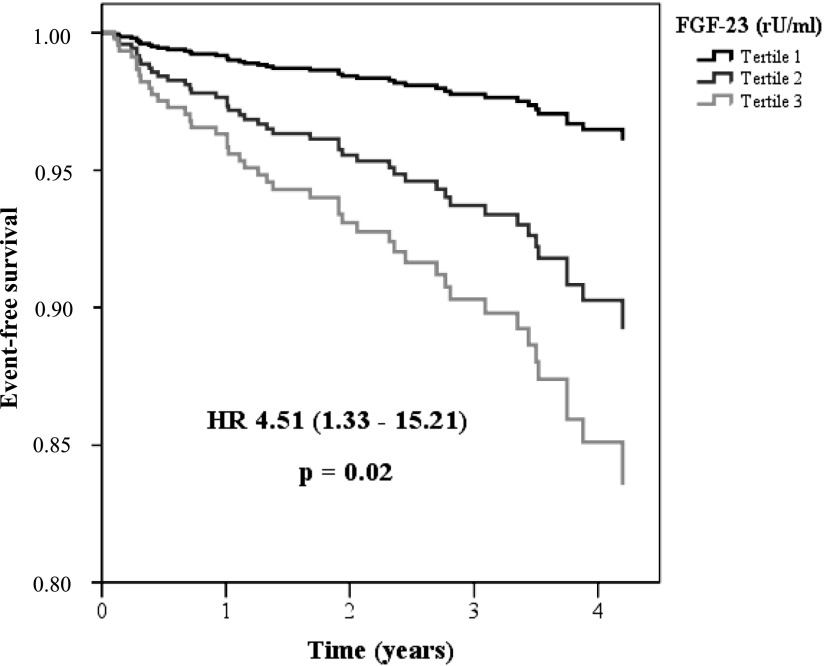

Patients were followed for 2.6 (interquartile range, 1.4–3.6) years. sKlotho tertiles predicted neither atherosclerotic events/death (fully adjusted Cox regression analysis: hazard ratio [HR] for third versus first sKlotho tertile, 0.75 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 0.43–1.30]; P=0.30) nor the occurrence of decompensated heart failure/death (HR for third versus first sKlotho tertile, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.39–1.66]; P=0.56). In contrast, patients in the highest FGF-23 tertile had higher risk for both end points in univariate analysis. Adjustment for kidney function attenuated the association between FGF-23 and atherosclerotic events/death (HR for third versus first FGF-23 tertile, 1.23 [95% CI, 0.58–2.61]; P=0.59), whereas the association between FGF-23 and decompensated heart failure/death remained significant after adjustment for confounders (HR for third versus first FGF-23 tertile, 4.51 [95% CI, 1.33–15.21]; P=0.02).

Conclusions

In this prospective observational study of limited sample size, sKlotho was not significantly related to cardiovascular outcomes. FGF-23 was significantly associated with future decompensated heart failure but not incident atherosclerotic events.

Keywords: chronic renal disease, calcium, fibroblast, arteriosclerosis

Introduction

Patients with CKD experience a tremendous burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which broadly comprises accelerated atherosclerosis, vascular stiffening, and left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (1). CKD–mineral and bone disorders (CKD-MBD) may substantially contribute to this high cardiovascular morbidity. Thus, clinical interest traditionally focused on identification (2–4) and treatment (5–7) of hyperphosphatemia, hyperparathyroidism, and hypovitaminosis D. Nonetheless, several interventional trials targeting these traditional CKD-MBD components failed to provide consistent evidence for a beneficial cardiovascular effect (8–12).

The recent identification of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23–Klotho axis improved our understanding of CKD-MBD. Studies showed that plasma levels of FGF-23, which are altered even in very early CKD stages (13), predicted adverse renal and cardiovascular outcome in patients with CKD. Thus, FGF-23 became the emerging biomarker in nephrology (14–16).

In contrast, epidemiologic research focused less on Klotho because of the assumption that Klotho was an exclusively membrane-bound protein not amenable to large-scale analysis in cohort studies. Although Klotho mainly acts as a membrane-bound FGF-23 coreceptor on renal tubular cells and on parathyroid cells (17), a soluble form of Klotho (sKlotho) also exists. The latter is derived from either cleavage of Klotho from the cell membrane or alternative splicing. Several renoprotective (18–20) and vasculoprotective (21,22) effects have been ascribed to sKlotho. With the recent establishment of an ELISA (23), sKlotho may become another CKD-MBD biomarker. However, before its widespread application as a diagnostic test, its utility must be elucidated in clinical studies.

In our ongoing CARE FOR HOMe (Cardiovascular And REnal outcome in CKD stage 2–4 patients—The FOuRth HOMburg evaluation) study, we measured sKlotho, FGF-23, and established CKD-MBD markers among 444 patients in CKD stages 2–4. We previously reported renal outcome data from a subcohort of 321 study participants, in whom sKlotho failed to predict CKD progression and death (24). Given the potential implications of sKlotho in vasculoprotection, we now set out to analyze cardiovascular outcome among the CARE FOR HOMe cohort.

Materials and Methods

Our ongoing CARE FOR HOMe study recruits patients with CKD from our outpatient clinic. Details of CARE FOR HOMe have been published recently (24).

In brief, patients with CKD stages 2–4 (eGFR, 15–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2 estimated by Modification of Diet in Renal Disease 4 equation; patients with CKD stage 2 had to show one or more markers of kidney damage, including albuminuria and/or plasma creatinine/cystatin C above references values) are included.

Systolic LV function was echocardiographically assessed in 405 patients at study inclusion. In addition, 20 patients had information on LV function from prior echocardiography (recorded at a median of 1.0 year before study initiation).

The local ethics committee approved the study, and all patients provided written informed consent. The authors adhered to the declaration of Helsinki.

Patients are invited annually for follow-up visits to our outpatient clinic. Patients unable or unwilling to follow this invitation are contacted for a telephone interview. We obtained medical records from the treating physicians to verify all reported events by study participants or their next of kin. Two nephrologists blinded to FGF-23 and sKlotho data adjudicated all events. In the case of disagreement, a third investigator was involved to make a final decision.

We predefined two cardiovascular end points: (1) atherosclerotic events/death, which comprises acute myocardial infarction (defined as a rise in troponin T above the 99th percentile of the reference limit accompanied by symptoms of ischemia and/or electrocardiographic changes indicating new ischemia) (25), surgical or interventional coronary/cerebrovascular/peripheral arterial revascularization, stroke (defined as rapidly developing clinical symptoms or signs of focal [or at times global] disturbance of cerebral function lasting >24 hours [unless interrupted by surgery] or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin) (26), amputation above the ankle and death of any cause; and (2) decompensated heart failure/death, which comprises hospital admission for decompensated heart failure (defined as admission for a clinical syndrome involving symptoms [progressive dyspnea] in conjunction with clinical [peripheral edema, pulmonary rales] or radiologic [cardiomegaly, pulmonary edema, pleural effusions] signs of heart failure) and death of any cause.

Additionally, the end points atherosclerotic events (censoring patients dying of noncardiac/noncardiovascular causes at time of death), decompensated heart failure (censoring patients dying without prior admission for decompensated heart failure at time of death) and all-cause mortality were analyzed a posteriori as explanatory end points.

The present study includes all CARE FOR HOMe participants recruited between September 2008 and November 2012 (n=444), who were followed until June 30, 2013. We previously reported the association between sKlotho and CKD progression in a subgroup of 321 patients recruited before February 2011 (24).

No patient was lost to follow-up. Patients not reaching an end point were censored at the time of the last annual follow-up visit (for patients who were contacted via phone, at the time of the last examination by their treating physician).

Laboratory Tests

Baseline blood samples were drawn under standardized conditions and processed as described previously (24). Plasma C-terminal FGF-23 levels and sKlotho were measured by ELISA (FGF-23: Immutopics, San Clemente, CA: low cutoff, 1.5 rU/ml; high cutoff, 1500 rU/ml; samples with FGF-23 levels >1500 rU/ml were measured after dilution; sKlotho: Immuno-Biologic Laboratories, Fujioka-shi, Gunma, Japan). The validity and reliability of the soluble α-Klotho ELISA were tested previously (24).

Intact parathyroid hormone (PTH) was measured by a second-generation electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay (Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Other blood variables were measured by standard laboratory methods.

In 422 patients, urinary fractional phosphate excretion (FePi) was calculated from a spot urine sample according to the following formula:

|

Albuminuria was defined as urinary albumin–to–urinary creatinine ratio.

Statistical Analyses

Data management and statistical analysis were performed with PASW Statistics 18. Categorical variables are presented as percentage of patients and were compared by Fisher exact test or chi-squared test, as appropriate. Continuous data are expressed as mean±SD and were compared using one-way ANOVA test (partitioning the between-groups sums of squares into trend components) or Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate. Albuminuria, sKlotho, FGF-23, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are presented as median (interquartile range) because of skewed distribution.

After stratifying patients into tertiles by their plasma sKlotho and plasma FGF-23 levels, we performed Kaplan–Meier analysis with consecutive log-rank testing for event-free survival. Additionally, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses with adjustment for potential confounders were conducted.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the study participants stratified by GFR categories are given in Table 1. As expected, patients in more advanced GFR categories were older, had higher CRP, FGF-23, phosphate, and PTH levels. Additionally, they had higher albuminuria and higher urinary fractional phosphate excretion and higher intake of vitamin D preparation. Finally, patients in more advanced GFR categories had slightly (albeit significantly) lower plasma sKlotho levels. Characteristics of patients stratified by tertiles of sKlotho or FGF-23 plasma levels, respectively, are presented in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants after stratification by CKD stages

| Characteristic | Total (n=444) | Stage 2 (n=89) | Stage 3a (n=128) | Stage 3b (n=145) | Stage 4 (n=82) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65±12 | 58±12 | 65±13 | 68±11 | 68±12 | <0.001 |

| Women, n (%) | 179 (40) | 28 (31) | 64 (50) | 52 (36) | 35 (43) | 0.36 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 44 (10) | 14 (16) | 13 (10) | 11 (8) | 6 (7) | 0.18 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 168 (38) | 28 (31) | 57 (45) | 47 (32) | 36 (44) | 0.64 |

| Prevalent CVD, n (%) | 135 (30) | 11 (12) | 45 (35) | 51 (35) | 28 (34) | <0.001 |

| Impaired systolic LV function | 62 (15) | 9 (11) | 12 (9) | 28 (23) | 13 (16) | 0.01 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.7 (1.2–5.3) | 2.4 (1.5–4.8) | 2.6 (1.0–5.2) | 2.9 (1.2–6.0) | 3.5 (1.1–5.6) | 0.003 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 193±42 | 199±37 | 191±40 | 191±45 | 193±47 | 0.47 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 52±17 | 52±16 | 53±18 | 51±17 | 49±17 | 0.18 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 116±36 | 122±32 | 113±35 | 114±36 | 117±39 | 0.41 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30±6 | 30±6 | 31±6 | 30±6 | 29±5 | 0.20 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.4±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.3±0.2 | 0.19 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.4±0.7 | 3.0±0.5 | 3.3±0.5 | 3.4±0.8 | 3.9±0.7 | <0.001 |

| FGF-23 (rU/ml) | 102 (64–164) | 62 (46–90) | 74 (54–105) | 128 (92–195) | 179 (140–291) | <0.001 |

| sKlotho (pg/ml) | 397 (326–485) | 433 (369–581) | 412 (344–493) | 374 (299–454) | 382 (303–459) | 0.02 |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 53 (37–84) | 41 (32–54) | 44 (32–57) | 62 (42–96) | 111 (67–162) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 45±16 | 68±6 | 52±4 | 38±4 | 22±4 | <0.001 |

| UAE (mg/g creatinine) | 37 (8–193) | 26 (7–108) | 19 (6–70) | 46 (11–164) | 129 (37–689) | <0.001 |

| FePi (%) | 26±13 | 17±8 | 20±9 | 28±11 | 40±13 | <0.001 |

| β-Blocker use, n (%) | 301 (68) | 45 (51) | 97 (76) | 96 (66) | 63 (77) | 0.001 |

| ACE-I use, n (%) | 165 (37) | 26 (29) | 60 (47) | 43 (30) | 36 (44) | 0.29 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 216 (49) | 29 (33) | 73 (57) | 70 (48) | 44 (54) | 0.01 |

| Unhydroxylated vitamin D3 intake, n (%) | 189 (43) | 38 (43) | 51 (40) | 51 (35) | 49 (60) | 0.01 |

| Active vitamin D3 intake, n (%) | 33 (7) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 14 (10) | 17 (21) | <0.001 |

Echocardiographic data were available in 425 patients. Variables are presented as numbers of patients (percentage), as mean±SD, or as median (interquartile range), as appropriate. CVD, cardiovascular disease; LV, left ventricular; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; BMI, body mass index; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor-23; sKlotho, soluble Klotho; PTH, parathyroid hormone; UAE, urinary albumin excretion; FePi, urinary fractional phosphate excretion; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

Participants were followed for a median of 2.6 years (interquartile range, 1.4–3.6 years). The combined end point of atherosclerotic events/death occurred in 81 patients (18%); 70 patients sustained an atherosclerotic event, and 11 patients died of noncardiac/noncardiovascular causes. The combined end point of decompensated heart failure/death occurred in 47 patients (11%), of whom 23 were admitted for decompensated heart failure and 24 died without prior admission for decompensated heart failure.

Nonfatal atherosclerotic events, admission for decompensated heart failure, and death occurred more frequently in patients with older age, prevalent CVD, impaired systolic LV function, higher CRP, and more advanced CKD (reflected by lower eGFR, higher PTH, and higher urinary fractional phosphate excretion) (Table 2). Moreover, patients with subsequent atherosclerotic events were more likely to have prevalent diabetes mellitus and to have lower total cholesterol as well as lower HDL and LDL cholesterol levels than patients with event-free survival.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants stratified by event status

| Characteristic | Atherosclerotic Events | Decompensated Heart Failure | Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=70) | No (n=374) | P Value | Yes (n=23) | No (n=421) | P Value | Yes (n=30) | No (n=414) | P Value | |

| Age (yr) | 71±8 | 64±13 | <0.001 | 73±7 | 65±13 | 0.002 | 73±8 | 65±13 | <0.001 |

| Women, n (%) | 21 (30) | 158 (42) | 0.06 | 7 (30) | 172 (41) | 0.39 | 8 (27) | 171 (41) | 0.13 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 8 (11) | 36 (10) | 0.66 | 1 (4) | 43 (10) | 0.72 | 3 (10) | 41 (10) | >0.99 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 39 (56) | 129 (34) | 0.001 | 11 (48) | 157 (37) | 0.39 | 14 (47) | 154 (37) | 0.33 |

| Prevalent CVD, n (%) | 49 (70) | 86 (23) | <0.001 | 14 (61) | 121 (29) | 0.002 | 18 (60) | 117 (28) | 0.001 |

| Impaired systolic LV function, n (%) | 16 (23) | 46 (12) | 0.03 | 16 (70) | 46 (11) | <0.001 | 12 (40) | 50 (12) | 0.001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 4.0 (1.7–8.6) | 2.6 (1.1–5.1) | 0.01 | 3.9 (2.4–9.8) | 2.7 (1.1–5.1) | 0.05 | 4.2 (2.4–9.6) | 2.6 (1.1–4.9) | 0.01 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 177±44 | 196±41 | <0.001 | 177±36 | 194±42 | 0.05 | 180±40 | 194±42 | 0.12 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 46±18 | 52±17 | 0.002 | 50±14 | 52±17 | 0.71 | 50±21 | 52±17 | 0.35 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 104±33 | 118±35 | 0.001 | 105±30 | 117±36 | 0.12 | 110±33 | 116±36 | 0.41 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30±5 | 30±6 | 0.57 | 32±5 | 30±5 | 0.09 | 29±5 | 30±5 | 0.29 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.3±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 0.35 | 2.4±0.2 | 2.4±0.1 | 0.91 | 2.4±0.1 | 2.4±0.1 | 0.54 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 3.6±0.9 | 3.3±0.7 | 0.01 | 3.9±0.5 | 3.4±0.7 | <0.001 | 3.6±0.6 | 3.4±0.7 | 0.12 |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 63 (41–110) | 52 (37–77) | 0.01 | 101 (62–126) | 52 (37–78) | <0.001 | 91 (62–117) | 51 (36–74) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 36±13 | 47±16 | <0.001 | 33±10 | 46±16 | <0.001 | 36±15 | 46±16 | 0.001 |

| UAE (mg/g creatinine) | 85 (24–399) | 30 (7–155) | 0.001 | 87 (24–179) | 32 (7–195) | 0.07 | 88 (26–31) | 31 (7–185) | 0.01 |

| FePi (%) | 33±13 | 24±13 | <0.001 | 35±10 | 25±13 | <0.001 | 34±12 | 25±13 | <0.001 |

| β-blocker use, n (%) | 56 (89) | 245 (66) | 0.02 | 21 (91) | 280 (67) | 0.01 | 25 (83) | 276 (67) | 0.07 |

| ACE-I use, n (%) | 31 (44) | 134 (36) | 0.18 | 3 (13) | 162 (38) | 0.01 | 11 (37) | 154 (37) | >0.99 |

| Statin intake, n (%) | 45 (64) | 171 (46) | 0.01 | 15 (65) | 201 (48) | 0.13 | 17 (57) | 199 (48) | 0.45 |

| Unhydroxylated vitamin D3 intake, n (%) | 36 (51) | 153 (41) | 0.12 | 11 (48) | 178 (42) | 0.67 | 15 (50) | 174 (42) | 0.45 |

| Active vitamin D3 intake, n (%) | 9 (13) | 24 (6) | 0.08 | 4 (17) | 29 (7) | 0.08 | 4 (13) | 29 (7) | 0.27 |

Echocardiographic data were available in 425 patients. Variables are presented as numbers of patients (percentage), as mean±SD, or as median (interquartile range), as appropriate. CVD, cardiovascular disease; LV, left ventricular; CRP, C-reactive protein; HDL-C, HDL cholesterol; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; BMI, body mass index; PTH, parathyroid hormone; UAE, urinary albumin excretion; FePi, urinary fractional phosphate excretion; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

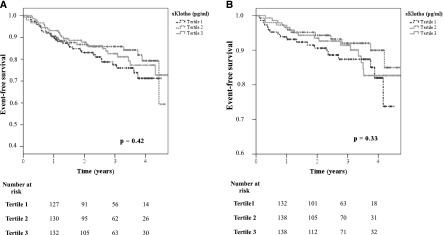

Upon stratifying patients by plasma sKlotho into tertiles for Kaplan–Meier analyses, the occurrence of neither atherosclerotic events/death (log-rank test: P=0.42) (Figure 1A) nor decompensated heart failure/death (log-rank test: P=0.33) (Figure 1B) was associated with sKlotho. Next, we analyzed sKlotho as a continuous rather than a categorical variable in a Cox regression analysis. Even at univariate analysis, sKlotho failed to predict atherosclerotic events/death and decompensated heart failure/death (Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 1.

Secreted Klotho (sKlotho) is not predictive for (A) atheroslcerotic events/death and (B) decompensated heart failure/death in univariate analysis. Patients were stratified into tertiles by their plasma sKlotho levels (Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test).

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis: atherosclerotic events/death

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Adjustment for eGFR and ln Albuminuria | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, and Sex | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, Sex, Diabetes Mellitus, and CVD | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, Sex, Diabetes Mellitus, CVD, and CKD-MBDa Measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| ln sKlotho | 0.80 (0.40–1.58) | 0.52 | 0.89 (0.45–1.77) | 0.75 | 0.84 (0.44–1.62) | 0.61 | 0.67 (0.34–1.34) | 0.26 | 0.66 (0.33–1.31) | 0.24 |

| PTH | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.006 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.94 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.90 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.90 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.95 |

| FePi | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.26 | 1.01 (0.98–1.03) | 0.66 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.93 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.86 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 1.31 (1.03–1.67) | 0.03 | 1.03 (0.77–1.37) | 0.84 | 1.04 (0.77–1.40) | 0.80 | 1.13 (0.83–1.55) | 0.44 | 1.12 (0.79–1.58) | 0.53 |

| ln FGF-23 (rU/ml) | 1.50 (1.22–1.85) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.90–1.56) | 0.24 | 1.14 (0.87–1.50) | 0.33 | 1.11 (0.86–1.44) | 0.41 | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) | 0.46 |

sKlotho (in pg/ml), albuminuria (in mg/g), and FGF-23 (in rU/ml) were ln-transferred because of skewed distribution. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD-MBD, CKD–mineral and bone disorders; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone; FePi, urinary fractional phosphate excretion.

ln sKlotho, PTH, FePi, phosphate and/or ln FGF-23, as appropriate

Table 4.

Cox regression analysis: decompensated heart failure/death

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Adjustment for eGFR and ln Albuminuria | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, and Sex | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, Sex, Diabetes Mellitus, and CVD | Adjustment for eGFR, ln Albuminuria, Age, Sex, Diabetes Mellitus, CVD, and CKD-MBDa Variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (915% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| ln sKlotho (pg/ml) | 1.12 (0.45–2.73) | 0.82 | 1.31 (0.53–3.21) | 0.56 | 1.20 (0.52–2.78) | 0.67 | 1.11 (0.46–2.67) | 0.82 | 1.01 (0.41–2.51) | 0.99 |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.16 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.11 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.05 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.17 |

| FePi (%) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.26 | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.42 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.50 | 1.01 (0.97–1.04) | 0.64 |

| Phosphate (mg/dl) | 1.40 (1.06–1.84) | 0.02 | 1.09 (0.76–1.55) | 0.65 | 1.08 (0.73–1.59) | 0.72 | 1.14 (0.76–1.70) | 0.53 | 1.05 (0.64–1.72) | 0.84 |

| ln FGF-23 (rU/ml) | 2.13 (1.66–2.72) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.37–2.54) | <0.001 | 1.71 (1.27–2.29) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.24–2.24) | 0.001 | 1.60 (1.17–2.18) | 0.003 |

sKlotho (in pg/ml), albuminuria (in mg/g), and FGF-23 (in rU/ml) were ln-transferred because of skewed distribution. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD-MBD, CKD–mineral and bone disorders; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; sKlotho, PTH, parathyroid hormone; FePi, urinary fractional phosphate excretion.

Ln sKlotho, PTH, FePi, phosphate and/ or Ln FGF-23, as appropriate.

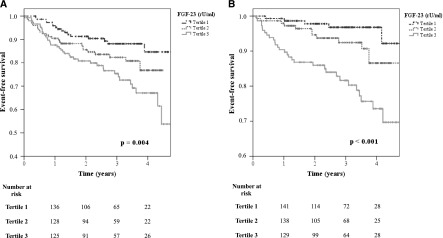

In contrast, highest tertiles of plasma FGF-23 were associated with both atherosclerotic events/death (P=0.004) (Figure 2A) and decompensated heart failure/death (P<0.001) (Figure 2B) in Kaplan–Meier analysis. Interestingly, adjustment for eGFR and ln albuminuria in a multivariate regression analysis eliminated the association of FGF-23 with atherosclerotic events/death (Table 3). In contrast, FGF-23 remained associated with decompensated heart failure/death after adjustment for eGFR and ln albuminuria; after additional adjustment for age and sex, prevalent diabetes mellitus, and CVD; and finally after further adjustment for other CKD-MBD components (Table 4). Study results did not substantially change upon inclusion of FGF-23 as a categorical (FGF-23 tertile) variable into Cox regression analyses (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). In the fully adjusted model, risk for subsequent hospital admission for decompensated heart failure/death was more than 4-fold higher among patients in the third FGF-23 tertile than in patients in the first tertile (P=0.02) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23 is predictive for (A) atherosclerotic events/death and (B) decompensated heart failure/death in univariate analysis. Patients were stratified into tertiles by their plasma FGF-23 levels (Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test).

Figure 3.

FGF-23 is an independent predictor for decompensated heart failure/death in multivariate analysis. Patients were stratified into tertiles by their plasma FGF-23 levels (multivariate Cox regression analysis). HR, hazard ratio.

To further exclude an interaction between sKlotho and FGF-23 in outcome analyses, we performed separate Kaplan–Meier analyses for FGF-23 tertiles within each tertile of sKlotho. Within each sKlotho tertile, patients with highest plasma FGF-23 had a significantly higher risk for decompensated heart failure/death (Supplemental Figure 1, A–C), but not for atherosclerotic events/death (data not shown).

More traditional components of CKD-MBD—namely PTH, urinary fractional excretion of phosphate, and plasma phosphate—predicted atherosclerotic events/death and decompensated heart failure/death only at univariate analysis. All three variables lost their predictive value after adjustment for eGFR (Tables 3 and 4).

To rule out that results are selectively driven by an association of FGF-23 with death rather than with cardiovascular events, we recalculated Cox regression analyses with decompensated heart failure, atherosclerotic events, and total mortality, respectively, as a single end point. In the fully adjusted model, ln FGF-23 was independently associated with decompensated heart failure (hazard ratio [HR], 1.62 [95% confidence interval (95% CI), 1.08–2.43]; P=0.02; Supplemental Table 5) and total mortality (HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.17–2.18]; P=0.003; Supplemental Table 6), but not with atherosclerotic events (HR, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.77–1.40]; P=0.80; Supplemental Table 7).

Discussion

In our ongoing CARE FOR HOMe study, we investigated the association of FGF-23, sKlotho, and established CKD-MBD markers with incident cardiovascular events. We could confirm a strong relationship between FGF-23 and the occurrence of adverse events, whereas plasma sKlotho was not related to emerging atherosclerotic events/death or decompensated heart failure/death.

CKD-MBD is postulated to contribute to the tremendous CVD burden of patients with CKD. Earlier experimental and epidemiologic studies suggested hyperphosphatemia, hyperparathyroidism, and hypovitaminosis D as emerging cardiovascular risk factors (14–16). Surprisingly, in interventional trials, intake of phosphate binders, cinacalcet, or active vitamin D did not exert a consistently beneficial effect on surrogate markers of CVD (8–11) or reduce cardiovascular event rates (12).

The recent identification of the FGF-23–Klotho axis as a novel central regulator of calcium-phosphate metabolism has once again spurred interest in CKD-MBD in the context of CVD. Importantly, Klotho and/or FGF-23 knockout animals experience systemic vascular calcification and early death (27,28), suggesting that the FGF-23–Klotho axis may be a potential novel target in cardiorenal medicine.

Of note, CKD-MBD measures are closely intertwined, and FGF-23 and Klotho are central regulators of urinary phosphate excretion and of calcitriol synthesis. Along this line, Klotho and/or FGF-23 knockout animals had elevated phosphate and vitamin D levels, the normalization of which protected these animals against vascular calcification and early death (29).

More direct evidence for a beneficial cardiovascular role of sKlotho derives from rodent CKD models, in which sKlotho lowered active phosphate uptake by vascular smooth muscle cells and thus protected animals against vascular calcification (21). Similarly, in human aortic smooth muscle cells, uremic serum downregulated Klotho gene expression and induced calcifying pathways, whereas restoration of Klotho activity protected against extracellular calcium deposition (22).

In contradiction to these data, recent experimental studies provided no evidence for a relevant Klotho expression in rodent vascular smooth muscle cells (30) or for any beneficial Klotho effect in endothelial dysfunction or vascular calcification (30). Finally, the idea of a protective role of sKlotho against active uptake of calcium or phosphate by vascular smooth muscle cells was refuted (31).

Given the controversial experimental data on Klotho expression in the vasculature, future laboratory studies should aim to reconcile these discrepant findings.

Unlike sKlotho, FGF-23 was associated with both cardiovascular end points in univariate analysis in CARE FOR HOMe. Interestingly, the prediction of atherosclerotic events/death was lost after adjustment for eGFR. Thus, elevated FGF-23 might be considered a reflector of more advanced CKD rather than a direct contributor to atherosclerotic events. This stands in partial contrast to analyses from the large Homocysteine in Kidney and End Stage Renal Disease (HOST) study, in which acute myocardial infarctions and peripheral arterial events were predicted by highest baseline FGF-23 levels (whereas strokes were not) (32). Of note, most HOST participants had GFR category G4, with a mean eGFR of 18 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Thus, in HOST the average FGF-23 levels were much higher, and interindividual variability of baseline eGFR were considerably lower, than in CARE FOR HOMe; consequently, adjustment for eGFR in HOST had a smaller effect on the association between FGF-23 and atherosclerotic events.

In CARE FOR HOMe, FGF-23 remained a strong predictor of decompensated heart failure and death even after full adjustment for kidney function, age, sex, comorbid conditions, and other CKB-MBD measures; no data on decompensated heart failure have been reported in HOST.

Our findings are underscored by prospective studies in patients with mostly intact kidney function, in whom FGF-23 predicted decompensated heart failure and death, but not acute myocardial infarction, in multivariate analyses (33,34). In keeping with these findings, FGF-23 was associated with impaired LV function and prevalent atrial fibrillation, but not with presence and degree of coronary artery disease (35), among 1309 patients admitted for elective coronary angiography in the HOM SWEET HOMe (Heterogenity of Monocytes in Subjects Who Undergo Elective Coronary Angiography—The Homburg Evaluation) study (15).

Experimental studies support a cardiotoxic rather than vascular FGF-23 effect: In mice, FGF-23 injection induced LV hypertrophy by Klotho-independent activation of the calcineurin–nuclear factor of activated T cells pathway; development of LV hypertrophy was inhibited by a pan-FGF receptor blocker (36). Of note, in a different experimental setup, antibody-mediated FGF-23 blockade did not prevent LV hypertrophy (37). Moreover, the causality between FGF-23 exposure and future development of LV failure—a potential long-term consequence of LV hypertrophy—remains unproven. Thus, the interaction between FGF-23 and cardiomyocytes appears to be complex, and further studies are needed to delineate the involved mechanisms.

Like FGF-23, plasma phosphate predicted atherosclerotic events/death only in univariate analysis in the present study. These findings seemingly contrast with the active role of phosphate in vascular calcification (38). Nonetheless, there is general agreement that plasma phosphate levels poorly indicate total phosphate burden (16), and most CARE FOR HOMe patients actually were normophosphatemic.

Given the epidemiologic nature of this study, we cannot provide data on tissue expression of Klotho, which would have required biopsy samples at study initiation. It remains unknown how far circulating sKlotho levels reflect tissue Klotho expression. In the context of controversial data on Klotho expression in vascular cells (21,22,30), we cannot rule out that Klotho tissue expression—unlike plasma sKlotho—may be associated with cardiovascular outcome. Nonetheless, following most recent animal data, which argue against Klotho expression in vascular cells (30), most experts believe that Klotho tissue expression is largely confined to kidney and parathyroidal cells. Thus, most extrarenal effects are expected to be mediated by circulating sKlotho. In contrast, tissue Klotho expression is presumably more relevant than sKlotho in renal calcium-phosphate handling. This may explain why we did not observe a correlation between sKlotho and traditional CKD-MBD measures, despite the central role of Klotho in renal phosphate excretion.

As a further potential limitation, a rather short follow-up period resulted in a relatively small number of events. The CIs for the HRs are therefore rather wide, and we cannot fully exclude that sKlotho might have some prognostic role that our present analysis failed to detect.

The present study complements our earlier analysis of CKD progression in CARE FOR HOMe, in which sKlotho did not predict adverse renal outcome among 321 patients with CKD followed for 2.2±0.8 years (24). The present analysis, which reports for the first time cardiovascular outcome among CARE FOR HOMe participants, has a prolonged follow-up period, and comprises 123 additional patients. Of note, given the larger database of the present analysis, we now observe a small (albeit significant) decline of sKlotho across CKD GFR categories, which, was not seen in our first analysis.

With the findings taken together, sKlotho was not significantly related to incident atherosclerotic events, decompensated heart failure, or death among 444 patients with CKD with a median follow-up of 2.6 years. FGF-23 was significantly associated with future decompensated heart failure but not with incident atherosclerotic events.

Disclosures

S.S. and K.S.R. received speaker fees from Sanofi. D.F. is a board member and has received speaker fees from Abbott, Amgen, Roche, Genzyme, and FMC. G.H.H. received speaker fees from Shire.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Marie-Theres Blinn and Martina Wagner for their excellent technical assistance; Annette Offenhäußer for collecting follow-up information; and Esther Herath, Anja Weihrauch, and Franziska Flügge for patient recruitment.

This work was supported by a grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07870713/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Herzog CA, Asinger RW, Berger AK, Charytan DM, Díez J, Hart RG, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, McCullough PA, Passman RS, DeLoach SS, Pun PH, Ritz E: Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease. A clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 80: 572–586, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL: Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int 71: 31–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tentori F, Blayney MJ, Albert JM, Gillespie BW, Kerr PG, Bommer J, Young EW, Akizawa T, Akiba T, Pisoni RL, Robinson BM, Port FK: Mortality risk for dialysis patients with different levels of serum calcium, phosphorus, and PTH: The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis 52: 519–530, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald R, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Cheung AK, Levey AS, Eknoyan G, Miskulin DC: Disordered mineral metabolism in hemodialysis patients: An analysis of cumulative effects in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 531–540, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoben AB, Rudser KD, de Boer IH, Young B, Kestenbaum B: Association of oral calcitriol with improved survival in nondialyzed CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1613–1619, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teng M, Wolf M, Ofsthun MN, Lazarus JM, Hernán MA, Camargo CA, Jr, Thadhani R: Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: A historical cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1115–1125, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Chang Y, Shah A, Tamez H, Smith K, Thadhani R, Wolf M: Phosphorus binders and survival on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 388–396, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Block GA, Wheeler DC, Persky MS, Kestenbaum B, Ketteler M, Spiegel DM, Allison MA, Asplin J, Smits G, Hoofnagle AN, Kooienga L, Thadhani R, Mannstadt M, Wolf M, Chertow GM: Effects of phosphate binders in moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1407–1415, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raggi P, Chertow GM, Torres PU, Csiky B, Naso A, Nossuli K, Moustafa M, Goodman WG, Lopez N, Downey G, Dehmel B, Floege J, ADVANCE Study Group : The ADVANCE study: A randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1327–1339, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chue CD, Townend JN, Moody WE, Zehnder D, Wall NA, Harper L, Edwards NC, Steeds RP, Ferro CJ: Cardiovascular effects of sevelamer in stage 3 CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 842–852, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thadhani R, Appelbaum E, Pritchett Y, Chang Y, Wenger J, Tamez H, Bhan I, Agarwal R, Zoccali C, Wanner C, Lloyd-Jones D, Cannata J, Thompson BT, Andress D, Zhang W, Packham D, Singh B, Zehnder D, Shah A, Pachika A, Manning WJ, Solomon SD: Vitamin D therapy and cardiac structure and function in patients with chronic kidney disease: The PRIMO randomized controlled trial. JAMA 307: 674–684, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R, Drüeke TB, Floege J, Goodman WG, Herzog CA, Kubo Y, London GM, Mahaffey KW, Mix TC, Moe SM, Trotman ML, Wheeler DC, Parfrey PS, EVOLVE Trial Investigators : Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 367: 2482–2494, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1370–1378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf M: Update on fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 82: 737–747, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heine GH, Seiler S, Fliser D: FGF-23: the rise of a novel cardiovascular risk marker in CKD. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3072–3081, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heine GH, Nangaku M, Fliser D: Calcium and phosphate impact cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 34: 1112–1121, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tohyama O, Imura A, Iwano A, Freund JN, Henrissat B, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y: Klotho is a novel beta-glucuronidase capable of hydrolyzing steroid beta-glucuronides. J Biol Chem 279: 9777–9784, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu MC, Moe OW: Klotho as a potential biomarker and therapy for acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 423–429, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quiñones H, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho deficiency is an early biomarker of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and its replacement is protective. Kidney Int 78: 1240–1251, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doi S, Zou Y, Togao O, Pastor JV, John GB, Wang L, Shiizaki K, Gotschall R, Schiavi S, Yorioka N, Takahashi M, Boothman DA, Kuro-o M: Klotho inhibits transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) signaling and suppresses renal fibrosis and cancer metastasis in mice. J Biol Chem 286: 8655–8665, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quiñones H, Griffith C, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 124–136, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim K, Lu TS, Molostvov G, Lee C, Lam FT, Zehnder D, Hsiao LL: Vascular Klotho deficiency potentiates the development of human artery calcification and mediates resistance to fibroblast growth factor 23. Circulation 125: 2243–2255, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazaki Y, Imura A, Urakawa I, Shimada T, Murakami J, Aono Y, Hasegawa H, Yamashita T, Nakatani K, Saito Y, Okamoto N, Kurumatani N, Namba N, Kitaoka T, Ozono K, Sakai T, Hataya H, Ichikawa S, Imel EA, Econs MJ, Nabeshima Y: Establishment of sandwich ELISA for soluble alpha-Klotho measurement: Age-dependent change of soluble alpha-Klotho levels in healthy subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398: 513–518, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seiler S, Wen M, Roth HJ, Fehrenz M, Flügge F, Herath E, Weihrauch A, Fliser D, Heine GH: Plasma Klotho is not related to kidney function and does not predict adverse outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 121–128, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Jaffe AS, Katus HA, Apple FS, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Chaitman BR, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow JJ, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasche P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Simoons ML, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Morais J, Aguiar C, Almahmeed W, Arnar DO, Barili F, Bloch KD, Bolger AF, Botker HE, Bozkurt B, Bugiardini R, Cannon C, de Lemos J, Eberli FR, Escobar E, Hlatky M, James S, Kern KB, Moliterno DJ, Mueller C, Neskovic AN, Pieske BM, Schulman SP, Storey RF, Taubert KA, Vranckx P, Wagner DR, Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Authors/Task Force Members Chairpersons. Biomarker Subcommittee. ECG Subcommittee. Imaging Subcommittee. Classification Subcommittee. Intervention Subcommittee. Trials & Registries Subcommittee. Trials & Registries Subcommittee. Trials & Registries Subcommittee. Trials & Registries Subcommittee. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) Document Reviewers : Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 1581–1598, 2012. 22958960 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatano S: Experience from a multicentre stroke register: A preliminary report. Bull World Health Organ 54: 541–553, 1976 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima YI: Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390: 45–51, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Tomizuka K, Yamashita T: Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest 113: 561–568, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stubbs JR, Liu S, Tang W, Zhou J, Wang Y, Yao X, Quarles LD: Role of hyperphosphatemia and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in vascular calcification and mortality in fibroblastic growth factor 23 null mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2116–2124, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindberg K, Olauson H, Amin R, Ponnusamy A, Goetz R, Taylor RF, Mohammadi M, Canfield A, Kublickiene K, Larsson TE: Arterial Klotho expression and FGF23 effects on vascular calcification and function. PLoS One 8: e60658, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scialla JJ, Lau WL, Reilly MP, Isakova T, Yang HY, Crouthamel MH, Chavkin NW, Rahman M, Wahl P, Amaral AP, Hamano T, Master SR, Nessel L, Chai B, Xie D, Kallem RR, Chen J, Lash JP, Kusek JW, Budoff MJ, Giachelli CM, Wolf M, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators : Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney Int 83: 1159–1168, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendrick J, Cheung AK, Kaufman JS, Greene T, Roberts WL, Smits G, Chonchol M, HOST Investigators : FGF-23 associates with death, cardiovascular events, and initiation of chronic dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1913–1922, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker BD, Schurgers LJ, Brandenburg VM, Christenson RH, Vermeer C, Ketteler M, Shlipak MG, Whooley MA, Ix JH: The associations of fibroblast growth factor 23 and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein with mortality in coronary artery disease: The Heart and Soul Study. Ann Intern Med 152: 640–648, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ix JH, Katz R, Kestenbaum BR, de Boer IH, Chonchol M, Mukamal KJ, Rifkin D, Siscovick DS, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG: Fibroblast growth factor-23 and death, heart failure, and cardiovascular events in community-living individuals: CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 60: 200–207, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seiler S, Cremers B, Rebling NM, Hornof F, Jeken J, Kersting S, Steimle C, Ege P, Fehrenz M, Rogacev KS, Scheller B, Böhm M, Fliser D, Heine GH: The phosphatonin fibroblast growth factor 23 links calcium-phosphate metabolism with left-ventricular dysfunction and atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 32: 2688–2696, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faul C, Amaral AP, Oskouei B, Hu MC, Sloan A, Isakova T, Gutiérrez OM, Aguillon-Prada R, Lincoln J, Hare JM, Mundel P, Morales A, Scialla J, Fischer M, Soliman EZ, Chen J, Go AS, Rosas SE, Nessel L, Townsend RR, Feldman HI, St John Sutton M, Ojo A, Gadegbeku C, Di Marco GS, Reuter S, Kentrup D, Tiemann K, Brand M, Hill JA, Moe OW, Kuro-O M, Kusek JW, Keane MG, Wolf M: FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 121: 4393–4408, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shalhoub V, Shatzen EM, Ward SC, Davis J, Stevens J, Bi V, Renshaw L, Hawkins N, Wang W, Chen C, Tsai MM, Cattley RC, Wronski TJ, Xia X, Li X, Henley C, Eschenberg M, Richards WG: FGF23 neutralization improves chronic kidney disease-associated hyperparathyroidism yet increases mortality. J Clin Invest 122: 2543–2553, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shroff R, Long DA, Shanahan C: Mechanistic insights into vascular calcification in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 179–189, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.