Abstract

OBJECTIVES

There are no guidelines regarding the best practice for when Barrett's esophagus (BE) is suspected but not confirmed by histology. The aim of this study was to examine the value of endoscopic follow-up for individuals with endoscopic only BE at index endoscopy.

METHODS

We performed a longitudinal study of patients diagnosed with suspected columnar lined esophagus (CLE) (suspected BE in the absence of histological confirmation of specialized intestinal metaplasia (IM)). We examined three possible outcomes (definite BE defined as CLE plus IM in targeted biopsies, suspected CLE, or no suspected CLE) on repeat endoscopy within 2 years after the index endoscopy and their predictors (clinical, demographic as well as endoscopists' identity).

RESULTS

A total of 107 of 1,844 patients had suspected CLE (101 were <3 cm), and 80 underwent a repeat endoscopy within 2 years. Approximately, 71% (95% confidence interval (CI) 61.1–80.9%) had suspected CLE confirmed at repeat endoscopy and only 29% (95% CI 19.1–38.9%) had IM. The length of CLE on the index esophagogastroduodenoscopies was slightly longer among patients with definite BE on repeat endoscopy than those with suspected CLE and no IM or no CLE (1.6 cm (s.d. 1.3) vs. 1.5 cm (s.d. 1.4), and 1.4 cm (s.d. 1.2), respectively P>0.1). Patient demographics, body mass index, gastro-esophageal reflux disease symptoms, hiatal hernia, and endoscopists' identity were not significantly associated with the outcome on the repeat endoscopy.

CONCLUSIONS

Most (71%) patients with suspected CLE remain negative for IM in the 2 years following the index endoscopy. The findings support withholding BE diagnosis for individuals with suspected CLE.

INTRODUCTION

The diagnostic criteria for Barrett's esophagus (BE) are debated among experts. The difficulty in determining the metaplastic nature of columnar epithelium in the distal esophagus coupled with the unreliability of endoscopic determination of the distal extent of the esophagus (1,2) are the main reasons for the debate. The epithelium detected in targeted biopsies of endoscopically suspected BE may contain gastric fundic glands, gastric cardia, or intestinal-type epithelium-containing goblet cells (3). The latter type of epithelium is considered essential for the definition of BE. However, given the possibility of sampling errors, IM may be missed when present in the esophagus or alternatively may be present in the cardia of the stomach usually as a result of Helicobacter pylori infection (4).

Practice guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology recommend that BE diagnosis is made by a combination of endoscopic diagnosis with confirmation of IM on histopathology. These guidelines also suggest performing two esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) within 1 year with targeted biopsies from suspected areas for confirmation of the BE diagnosis and ruling out dysplasia (5). However, there are currently no recommendations on the need or frequency of follow-up for patients with a negative or indeterminate histopathology for BE in patients with suspected BE based on endoscopic findings.

Neither the prevalence of endoscopic BE only (in the absence of specialized intestinal metaplasia (IM)) nor the reliability of this diagnosis are clear. The Munich BE follow-up study showed that only 11% of 49 patients with an index endoscopy showing suspected columnar lined esophagus (CLE) without IM had a subsequent confirmatory diagnosis by endoscopy and histology performed at least 1.5 years following the initial examination (6). However, this study evaluated a relatively small number of such patients, and the multicenter setting of the study with several endoscopists and histopathologists may have affected the consistency of the reported findings. More studies are required to define the prevalence of the entity of suspected CLE without IM and the reliability of diagnosis on follow-up.

Given the poorly understood prevalence and short-term outcome of suspected CLE without IM, we examined patients enrolled in a prospective single-center study who were systematically and uniformly screened for BE. In patients whose index endoscopy was suspicious for BE (i.e., suspected CLE) but unconfirmed by histology (i.e., no IM), we performed a follow-up repeat endoscopy with esophageal biopsy to determine BE status.

METHODS

Study population and design

We performed a longitudinal study at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, TX among patients with endoscopic only BE.

This study was nested within a large single-center study that prospectively enrolled patients to determine prevalence and risk factors for BE. Methods are reported elsewhere (7), but briefly we recruited all eligible patients who were scheduled for an elective EGD at MEDVAMC. We also recruited eligible patients from seven selected primary care clinics at the same hospital between 1 September 2008 and 31 December 2010. The patients who were scheduled for an elective EGD were 92.4% male, 30.4% African-American, 65% White, and 4.6% other race, and the mean age was 60.5 (s.d.=8.5) years. The patients recruited from elective EGD were 91% male, 28.7% African-American, 68.6% White, and 2.8% other race, and their mean age was 59.9 (s.d. = 8.4) years.

The eligibility criteria were: (1) age between 40–80 years; (2) no previous gastro-esophageal surgery; (3) no previous cancer of the esophagus; (4) no active lung, liver, colon, breast, or stomach cancer; (5) not currently taking anticoagulants; (6) no significant liver disease indicated by platelet count >70×103/mm3, ascites, or known gastro-esophageal varices; and (7) no history of major stroke or mental condition that would limit their ability to answer questions. For the primary care group, we invited patients who were eligible for screening colonoscopy to participate in this study and undergo a study EGD at the same time as their colonoscopy. The same eligibility criteria were used with the exception of the lower age limit, which was raised to 50 years.

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the MEDVAMC and Baylor College of Medicine.

Data collection

All study participants underwent an EGD with systematic recording of suspected CLE if there was a visualized extension of possible columnar epithelium into the distal esophagus and proximal to the beginning of the gastric folds. Suspected CLE was classified using the Prague (circumferential) and M (maximal extent) classification (8). Depending on the length and configuration of the suspected CLE segments, four quadrant biopsies at intervals of 2cm from suspected CLE areas were taken using jumbo biopsy forceps. From short CLE segments, at least one biopsy had to be obtained from each tongue of suspected CLE and at least two biopsies from any circumferential suspected BE. Two expert pathologists reviewed all slides. Definitive BE was defined as the presence of IM in the histopathological examination of biopsy samples obtained from suspected CLE areas. CLE without IM only was defined by the presence of endoscopically suspected CLE in the absence of IM on histopathology.

Patients with suspected CLE on endoscopy and no IM on histopathology were invited for a follow-up EGD with biopsies within 2 years of the initial examination. The follow-up endoscopy was carried out in the same manner with review of biopsies by two expert pathologists. We also collected the identity of the endoscopist performing the index as well as follow-up endoscopy.

Data analysis

We calculated the prevalence of suspected CLE from the index study EGD among study participants. We examined the three possible outcomes (definite BE, CLE without IM, or no CLE) on the repeat EGD in patients with an index EGD showing suspected CLE with no IM on histopathological evaluation. We calculated the proportions and the accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of patients with these outcomes. We also examined the possible determinants of suspected CLE on the index EGD and three possible outcomes on repeat EGD. The potential determinants included demographic (age, sex, race), clinical (body mass index, presence of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), proton pump inhibitor intake, histamine-2 receptor antagonist intake, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use), endoscopic features (maximum length of CLE, hiatus hernia, Hill's classification of the gastro-esophageal flap valve), and the endoscopist's identity. Definitions for these variables were reported in our previous manuscripts (7,8).

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon's test for continuous variables. Logistic regression models were used for multivariable adjustment. Parameter estimates and s.es. from the model were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and their accompanying 95% CIs.

RESULTS

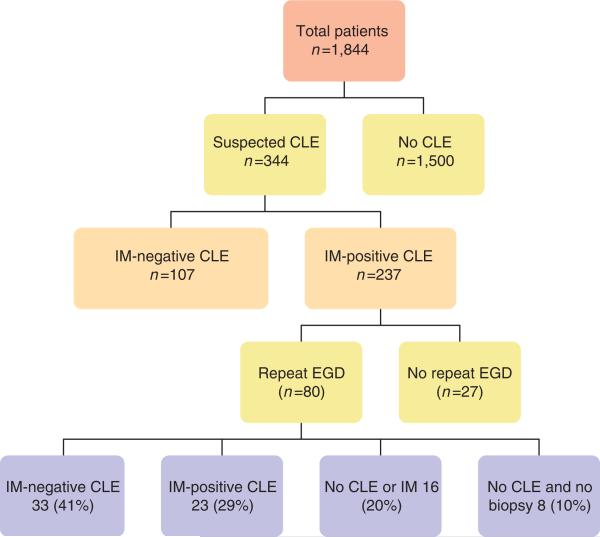

A total of 1,844 participants underwent EGD as part of the study; 1,263 (68%) were referred for elective EGD and 581 (32%) were patients recruited from primary care for EGD and colonoscopy. Suspected CLE was recorded in 344 (19%) subjects on the index endoscopy (Figure 1). Of these, 237 (13% of the total study population) were found to have definite BE on histopathology (IM) and the rest were CLE without IM. Among patients with definite BE, 146 (62%) had short segment (<3 cm) BE and 91 (38%) had long segment. At least one esophageal biopsy was obtained from all patients. Among patients with CLE without IM, most (101, 94%) had a short segment of CLE. Repeat endo scopy was performed on 80 subjects within 2 years of the index endoscopy. Mean duration between endoscopies was 523 days (1.46 years). The rest of the subjects declined or did not show up for follow-up endoscopy.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of enrollment and outcomes of patients in the study. CLE, columnar lined esophagus; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopies; IM, intestinal metaplasia.

Of the 80 subjects with CLE and no IM who underwent repeat endoscopy, 96% were male, with an age distribution of 40–49 (14%), 50–59 (26%), 60–69 (46%), and > 70 years (14%). Repeat endoscopy with esophageal biopsies showed that in 24 (30%; 95% CI 20.0–40.0%) subjects with suspected CLE and no IM was not confirmed, 33 (41%; 95% CI 30.2–51.8%) subjects had endoscopically suspected BE (i.e., with CLE) that remained negative histopathology for IM, and 23 (29%; 95% CI 19.1% to 38.9%) subjects with suspected CLE had confirmed BE on histopathology (Figure 1). Of the subjects with suspected CLE and no IM, biopsies showed squamous epithelium in 20 (61%, 95% CI 50.3% to 71.7%), columnar lined epithelium in 11 (33%, 95% CI 22.7–43.3%), and gastric oxyntic mucosa in 2 (6%, 95% CI 0.8–11.2%). There was no dysplasia seen in any of the repeat biopsies in confirmed BE. Nine of the repeat endoscopies were done by the endoscopist who performed the index procedure with an 89% concordance of diagnosing suspected CLE, whereas 71 were done by a different endoscopist with a concordance of 68%. There was no significant difference in the proportions of patients with CLE and no IM or definitive BE according to the identity of the endoscopist.

Comparisons between the subjects with CLE and no IM and those with CLE and IM showed that there was no significant differences in the two groups with respect to age, gender, race, body mass index, presence or duration of GERD, length of CLE, hiatal hernia, Hill flap valve classification, or use of anti-secretory agents (P>0.1) (Table 1). The mean length of suspected CLE on index endoscopy in patients with definite BE was slightly longer but not statistically significant (1.6 cm, s.d. 1.3) than those with suspected BE and no IM (1.5 cm, s.d. 1.4) or no CLE (1.4 cm, s.d. 1.2) on repeat EGD. The median suspected CLE length was 1 cm for both the groups. The interquartile range for the confirmed BE group was 1 cm (interquartile range 1–2 cm), and 1.5 for the no BE group (interquartile range 0.5–2 cm). Testing the medians and distributions using non-parametric tests yielded non-significant results, both for the groups as a whole (Mann–Whitney U: P=0.33) and for the smaller groups when the lengths <0.5 are excluded (P=0.51). Among patients with 0.5 cm of CLE on index exam, only 19.2% showed definitive BE on repeat EGD. There were no instances of surgical or endoscopic ablation in any of the study patients. There were no significant differences in the use of proton pump inhibitor between those with different CLE lengths. The multivariable logistic regression adjusting for source of referral (endoscopy vs. PCP) there were no significant predictor factors of definitive BE on follow-up endoscopy.

Table 1.

Association between demographic and clinical features at the time of the index endoscopy among patients with suspected CLE and the presence or absence of definitive BE (endoscopic CLE plus IM) on follow-up endoscopy

| Finding on follow-up endoscopy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline features | No CLE or IM | Definitive BE | P-value |

| N | 57 | 23 | |

| Male sex | 55 (96.5%) | 22 (95.6%) | 0.858 |

| Age, years | |||

| 40–49 | 10 (17.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.153 |

| 50–59 | 17 (29.8%) | 4 (17.4%) | |

| 60–69 | 24 (42.1%) | 13 (56.5%) | |

| 70–79 | 6 (10.5%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 39 (68.4%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.803 |

| Black | 9 (15.8%) | 3 (13.0%) | |

| Latino | 9 (15.8%) | 5 (21.7%) | |

| Patient source | |||

| Endoscopy | 47 (82.5%) | 14 (60.9%) | 0.040 |

| PCP | 10 (17.5%) | 9 (39.1%) | |

| Original CLE length ≥3 cm | 9 (15.8%) | 3 (13%) | 0.756 |

| BMI >30 kg/m2 | 25 (43.9%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.064 |

| High WHRa | 49 (87.5%) | 20 (87.0%) | 0.947 |

| NSAID use | |||

| Yes | 29 (50.8%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.530 |

| PPI use | |||

| Yes | 32 (56.1%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.455 |

| H2RA use | |||

| Yes | 6 (10.5%) | 2 (8.7%) | 0.803 |

| Hiatal hernia | |||

| Absent | 17 (29.8%) | 6 (26.1%) | 0.773 |

| <3 cm | 27 (47.3%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

| ≥3 cm | 13 (22.8%) | 7 (30.4%) | |

| Hill flap valve | |||

| Grade I | 18 (31.6%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.302 |

| Grade II | 10 (17.5%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Grade III | 9 (15.8%) | 6 (26.1%) | |

| Grade IV | 19 (33.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | |

| GERD symptoms | |||

| None | 23 (40.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.831 |

| <5 years | 5 (8.8%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| 5–10 years | 7 (12.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | |

| ≥10 years | 21 (36.8%) | 10 (43.5%) | |

BE, Barrett's esophagus; BMI, body mass index; CLE, columnar lined esophagus; GERD, gastro-esophageal reflux; H2RA, histamine-2 receptor antagonist; IM, intestinal metaplasia; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PCP, primary care physician; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

High WHR is defined as >=0.9 in males and >=0.85 in females.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we determined the utility of repeating EGD in patients with endoscopic appearance of BE on index endoscopy (i.e., suspected CLE) with no histological confirmation (i.e., no IM). We found that most patients (41%) continued to have a negative histopathology result or had no suspected CLE (30%), and only 29% of the repeat evaluations showed biopsy-proven BE. Apart from a non-significant trend toward longer length of CLE, we found no demographic or clinical predictors for the presence of definitive BE on repeat EGD. These findings support a recommendation of a second follow-up EGD after an initial diagnosis of CLE with no IM and also support a definition of BE that is based on histopathology in addition to endoscopic findings.

We recommend considering a follow-up EGD in 2–3 years following an index EGD showing suspected CLE without IM. This is based on the finding in our study that no cases of dysplasia or cancer were detected in up to 2 years follow-up. This is not currently recommended for or against by the current guidelines. Although we examined several risk factors for BE development, including old age, male sex, presence of GERD, Caucasian race, and abdominal obesity (9), none predicted the presence of definite BE on repeat endoscopy among patients with an initial diagnosis of suspected CLE without IM. This poses a challenge in recognizing and thus in performing targeted repeat EGD to determine which of the suspected CLE cases would have a higher predictability of a positive IM histopathological diagnosis on repeat endoscopy. Given the relatively low confirmation rate of BE on subsequent EGD, a strategy of repeat confirmatory EGD is likely to be considerably cost effective than one that considers all suspected CLE for BE surveillance strategies. Among patients with 0.5 cm of suspected CLE on index exam, only 19% showed IM-positive BE on repeat EGD. It is unclear whether or not endoscopy follow-up is required in these patients, especially given that the cancer risk associated with this ultra-short segment is considered very low.

CLE without IM seems to be a reproducible diagnosis in the setting of research studies. The one previous study that examined this showed that only approximately 11% of the patients with suspected CLE and no IM had repeat positive IM histology confirming the diagnosis of BE (6). Our study showed a slightly higher proportion, but both studies show that the majority of CLE without IM cases will persist as such. It is unclear whether similar results will be shown in routine clinical practice, and it is possible that an initial diagnosis of suspected CLE without IM will be more frequently converted to definitive BE than what we reported. This concern further supports a recommendation of a second follow-up endoscopy within 2–3 years of the index EGD.

Reproducibility of endoscopic biopsy findings may vary based on sampling methodology and BE segment length. The length of the suspected CLE segment seems to be the major determinant of the presence of IM. In our study, 72% of patients with suspected CLE had a Prague C (circumferential) and M (maximal extent) (8) of <3 cm compared with only 62% of patients with definitive BE. Similarly, in the follow-up phase of our study there was a non-significant trend toward longer CLE segment among those with definitive BE compared with the rest. Whether this association refers to true absence of IM or a sampling error is unclear. However, the persistent absence of IM on two successive EGDs argues against sampling error.

Defining BE based on endoscopic findings of suspected BE including short segments will greatly inflate the prevalence of BE without evidence of benefit. In our study, approximately 7 out of the 10 diagnosed with endoscopic BE only did not have IM in two successive endoscopies, and none of the repeat biopsies with IM had evidence of dysplasia. A previous study looking at the presence of goblet cells in patients with suspected CLE found that only 19% with CLE < 2 cm had goblet cells. Foregoing this requirement increased the diagnosis of BE by 147% (10).

The strengths of our study included the prospective design, the systematic recording of endoscopic landmarks and biopsy collection, the collection of information on several potential predictors, and the relatively large sample size of patients who underwent endoscopy. Biopsies from the index as well as repeat endoscopy biopsies were taken as per a pre-determined protocol and reviewed by two expert pathologists. Both procedures were done within a relatively short time interval to minimize the likelihood of new findings and thus allow the proper examination of reproducibility. Furthermore, we tracked and analyzed the effect of having diggerent endoscopists performing these procedures. However, despite this, the interobserver variability in identifying suspected BE was low.

In summary, suspected CLE with no IM is relatively common among patients presenting to elective endoscopy, and this is a reproducible finding in approximately 70% of cases. We recommend a second follow-up EGD in 2–3 years to avoid missing the approximately 30% of cases of definitive BE and unnecessary surveillance of the 70% without definitive BE.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

The best practice for follow-up is not known when Barrett's esophagus (BE) is suspected endoscopically but intestinal metaplasia (IM) not confirmed by histology.

The best practice for follow-up is not known when Barrett's esophagus (BE) is suspected endoscopically but intestinal metaplasia (IM) not confirmed by histology. Only one previous European study of 49 patients with an index endoscopy showing endoscopic BE only showed that only 11% had a subsequent confirmatory diagnosis by endoscopy and histology.

Only one previous European study of 49 patients with an index endoscopy showing endoscopic BE only showed that only 11% had a subsequent confirmatory diagnosis by endoscopy and histology. More information is needed, and therefore the aim of this longitudinal prospective study was to evaluate the value of endoscopic follow-up for individuals with suspected columnar lined esophagus (CLE) with no IM.

More information is needed, and therefore the aim of this longitudinal prospective study was to evaluate the value of endoscopic follow-up for individuals with suspected columnar lined esophagus (CLE) with no IM.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

Eighty patients consecutively diagnosed with suspected CLE and no IM underwent a repeat endoscopy within 2 years, and approximately 71% (n = 56) had suspected CLE but no IM confirmed at repeat endoscopy and only 29% (n = 23) had IM.

Eighty patients consecutively diagnosed with suspected CLE and no IM underwent a repeat endoscopy within 2 years, and approximately 71% (n = 56) had suspected CLE but no IM confirmed at repeat endoscopy and only 29% (n = 23) had IM. Patient gender, age, race, body mass index, gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms, size of hiatal hernia, nor endoscopists' identity were not significantly associated with the outcome on the repeat endoscopy.

Patient gender, age, race, body mass index, gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms, size of hiatal hernia, nor endoscopists' identity were not significantly associated with the outcome on the repeat endoscopy. The diagnosis of definitive BE should not be routinely given to patients with suspected CLE, and in patients with suspected CLE but no IM follow-up endoscopy should be considered.

The diagnosis of definitive BE should not be routinely given to patients with suspected CLE, and in patients with suspected CLE but no IM follow-up endoscopy should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Financial support : This work is funded in part by an NIH grant NCI R01 116845, the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-020), and the Texas Digestive Disease Center NIH DK58338. H.B.E.-S. is also supported by NIDDK K24-04-107.

Footnotes

Specific author contributions: Funding, conception, design, analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript writing, editing, and decision to publish: Hashem B. El-Serag; conception, data collection, interpretation results, editing manuscript, and decision to publish: Hashim E. Khandwalla; analysis, conception, editing manuscript, and decision to publish: David Y. Graham; analysis, data collection, editing manuscript, and decision to publish: Jennifer R. Kramer; data collection, editing manuscript, and decision to publish: David J. Ramsey; data collection, editing manuscript, and decision to publish: Ngoc Duong; analysis, conception, editing manuscript, decision to publish: Linda K. Green.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Hashem B El-Serag, MD, MPH.

Potential competing interests : None.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

REFERENCES

- 1.McClave SA, Boyce HW, Jr, Gottfried MR. Early diagnosis of columnar-lined esophagus: a new endoscopic criterion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:413–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(87)71676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi do W, Oh SN, Baek SJ, et al. Endoscopically observed lower esophageal capillary patterns. Korean J Intern Med. 2002;17:245–8. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paull A, Trier JS, Dalton MD, et al. The histologic spectrum of Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:476–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608262950904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spechler SJ. Intestinal metaplasia at the gastroesophageal junction. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:567–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang K, Sampliner R. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meining A, Ott R, Becker I, et al. The Munich Barrett follow up study: suspicion of Barrett's esophagus based on either endoscopy or histology-what is the clinical significance? Gut. 2004;53:1402–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.036822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer J, Fischbach LA, Richardson P, et al. Waist to hip ratio but not body mass index is associated with increased risk of Barrett's esophagus in white men. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:373–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia JM, Splenser AE, Kramer J, et al. Circulating inflammatory cytokines and adipokines are associated with Barrett's esophagus: a case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;12:01179–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett's esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong A, Fitzgerald R. Epidemiologic risk factors for Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00602-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westerhoff M, Hovan L, Lee C, et al. Effects of dropping the requirement for goblet cells from the diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1232–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]