Abstract

Cytochromes c are ubiquitous heme proteins that are found in most living organisms and are essential for various energy production pathways as well as other cellular processes. Their biosynthesis relies on a complex post-translational process, called cytochrome c biogenesis, responsible for the formation of stereo-specific thioether bonds between the vinyl groups of heme b (protoporphyrin IX-Fe) and the thiol groups of apocytochromes c heme-binding site (C1XXC2H) cysteine residues. In some organisms this process involves up to nine (CcmABCDEFGHI) membrane proteins working together to achieve heme ligation, designated the Cytochrome c maturation (Ccm)-System I. Here, we review recent findings related to the Ccm-System I found in bacteria, archaea and plant mitochondria, with an emphasis on protein interactions between the Ccm components and their substrates (apocytochrome c and heme). We discuss the possibility that the Ccm proteins may form a multi subunit supercomplex (dubbed “Ccm machine”), and based on the currently available data, we present an updated version of a mechanistic model for Ccm.

Keywords: Cytochrome c maturation, membrane supercomplex, apocytochrome, chaperone, protein-protein interactions, Rhodobacter capsulatus, photosynthesis and respiration

1. Introduction

Cytochromes (cyts) are ubiquitous hemoproteins that are key components of energy transduction pathways, and essential for cellular processes spanning from chemical energy (ATP) production to programmed cell death induction (apoptosis) [1–3]. All cyts c invariably contain at least one protoporphyrin IX-Fe (heme b) cofactor, which is stereo-specifically ligated to the polypeptide by two (rarely one) thioether bonds. These bonds are formed between the vinyl-2 and vinyl-4 of heme tetrapyrrole ring and the thiol groups of Cys1 and Cys2 located at a conserved heme-binding motif (C1XXC2H) within the apocytochromes (apocyts) c [4]. The His residue of this motif together with another Met or His residue coordinate axially the heme-iron [5] (Fig. 1). Variations at the conserved C1XXC2H heme-binding motif occur in mitochondrial cyts c (AXXCH) and c1 (FXXCH) of the phylum Euglenozoa that contain a single Cys at the heme-binding site [6], and in bacterial nitrite reductase NrfA (C1XXC2K) where His is replaced with a Lys residue [7]. In addition, the number and nature of the amino acid residues between the Cys1 and Cys2 residues of the heme-binding motif may also vary, with C1(X)3C2H and C1(X)4C2H found in tetraheme cyts c3 [8, 9] and C1(X)15C2H in the octaheme MccA [10].

Figure 1. Heme b is stereo-specifically ligated to apocyts c.

Two thioether bonds are formed between the vinyl groups at positions 2 and 4 of the heme tetrapyrrole ring and Cys1 and Cys2 thiol groups at a conserved heme-binding motif (C1XXC2H) of apocyts c. The His residue of this motif together with another His or Met residues act as axial ligands of the heme-iron (Fe). Following the cyt c maturation (Ccm) process, holocyts c are folded into their native conformations and become functional. Cyts c perform key cellular functions and are very diverse in terms of their 3D structures, heme contents, redox properties, and can be grouped into different classes (e.g., I, II, III, etc.).

Cyts c exhibit different three dimensional (3D) structures, redox properties, and functions (Fig. 1), and can be grouped into four classes based on their major characteristics [11]. Class I cyts c is the largest group that includes the small, soluble cyts c with a generally globular fold. They usually contain a single amino (N-) terminal heme-binding motif and a Met residue acting as sixth ligand located at their carboxyl (C-) termini (e. g. mitochondrial cyt c or Rhodobacter capsulatus cyt c2). Class II cyts c includes the high spin cyt c' with a C-terminally located heme-binding motif and a four helical bundle fold. Class III comprises the low redox potential (Em) multi heme cyts c with bis-His coordination, and finally cyts c that contain additional non-heme cofactors (e.g., flavins) are grouped in class IV (Fig. 1).

2. Diversity of Cytochrome c Biogenesis Systems

Cytochrome c biogenesis is an intricate process present in virtually all organisms, and ensures the covalent ligation of heme to an apocyt c (Fig. 1). It relies on major cellular functions such as protein translocation followed by post-translational modification, extra-cytoplasmic protein folding and degradation, redox homeostasis, metal cofactor acquisition and insertion into target proteins. Several maturation processes (System I to IV) sharing common characteristics were identified [12–17]. First, all apocyts c are synthesized in the cytoplasm and translocated via the Sec pathway [18, 19] across a lipid bilayer into a cellular compartment where they mature and function. This compartment is always on the positive (p) side of an energy transducing membrane (e.g., bacterial periplasmic space) with the exception of the cyt b6f complex cyt ci (also called cx or cn), which is formed on the negative (n) side of the thylakoid membranes [17]. Second, biosynthesis and transport of heme and translocation of apocyts c occur via distinct and independent processes, which are coordinated spatially and temporally to minimize cytotoxic effects of heme and proteolytic degradation of apocyts c [20, 21]. Third, both the heme-iron atom and the apocyt c heme-binding motif Cys thiol groups need to be reduced for thioether bond formation [12, 22]. Fourth, dedicated chaperones and enzymes are required for ligation of heme to the apocyts c in a stereo-specific configuration. Finally, mature cyts c are assembled into their respective cyt c complexes following their biogenesis.

The most complex process, the Cytochrome c maturation (Ccm)-System I, is found in α- and γ-proteobacteria, in archaea, and in mitochondria of plants and red algae. Ccm-System I of Escherichia coli, Rhodobacter capsulatus and Arabidopsis thaliana are best studied, and involve up to nine specific membrane-bound proteins, described below. Ccm-System I is able to ligate heme b to a variety of substrates, including cyts c that are matured normally by other systems [23], polypeptides that contain multiple hemes [24], and short peptides (e.g., ten amino acid residues long) [25]. Mutagenesis studies revealed that the presence of a C1XXC2H heme-binding site is necessary for Ccm-mediated efficient heme attachment [26–28].

Cytochrome c biogenesis -System II, also designated Ccs (Cyt c synthesis), is used by the β-, δ- and ε-proteobacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, Aquificales, cyanobacteria, and also algae and plant chloroplasts [15]. Representative examples are found in Chlamydomonas reinhartii [29] and Bacillus subtilis [30] that are composed of four (sometimes only three) membrane-bound proteins, CcsA (or ResC) and CcsB (or ResB) working together with CcdA and CcsX (ResA). In some organisms, such as Wolinella succinogenes CcsB and CcsA are fused into a single polypeptide [31]. CcdA and CcsX are required for thioreduction of apocyt c thiol groups, whereas CcsAB complex transports heme b to the p side of the membrane, recognizes the apocyt c substrates and forms the thioether bonds between the apocyt c and heme b. Substrate specificity of Ccs is not yet fully established, but it may be as broad as the Ccm-System I [32, 33].

The simplest form of Cytochrome c biogenesis is confined to mitochondria of fungi, metazoans and some protozoa, and is designated System III or CCHL (Cyt c heme lyase). In fungi, there are two heme lyases specific for the cyts c1 (CC1HL) [34] and c (CCHL) [35] while in mammals only one heme lyase (HCCS, as in holocyt c synthetase) matures both these cyts [36, 37]. Additionally, in yeast a third component (Cyc2p) with NAD(P)H-dependent heme reductase activity was identified [16, 38]. CCHL is a heme containing membrane-associated protein that recognizes a consensus sequence (K/A5G6XXL/I9F10XXXC14XXC17H18) at the N-terminal portion of apocyts c substrates for heme b ligation [39–42].

Additional biogenesis processes dealing with unusual cyts c also exist, but these are less studied. System IV catalyzes the attachment via a single thioether bond of the unique heme ci (or cx) in cyt b6 of the cyt b6f complex. It acts on the n side of the thylakoid membranes, and includes at least four membrane-bound proteins of unknown roles [17]. The occurrence of an additional biogenesis process (System V) is expected in mitochondria of euglenozoans as these organisms lack any of the above described proteins, despite the fact that both of their cyts c and c1 are remarkably similar to other mitochondrial homologues, except that their heme-binding motif (A/FXXCH) contains only a single Cys residue [16].

The present review focuses on the Ccm-System I as found in α- and γ-proteobacteria and plant mitochondria, with an emphasis on R. capsulatus. We describe the recent findings related to the Ccm components that are grouped as functional modules. We also discuss an updated version of a working model for the mechanism of stereo-specific heme ligation and the possible occurrence of a multi subunit Ccm supercomplex (dubbed a “Ccm machine”).

3. Ccm-System I: Functional Organization

Ccm-System I involves up to nine membrane-bound components (CcmABCDEFGHI) in R. capsulatus that can be grouped into three modules based on their functions and interactions with their partners (Fig. 2 and Table 1). These three modules accomplish the (i) transport and relay of heme b (Module 1), (ii) preparation and chaperoning of ligation-competent apocyts c (Module 2), and (iii) ligation of heme-apocyt c (Module 3) to yield holocyts c.

Figure 2. Functional organization of Ccm.

Three membrane-integral functional modules carry out the Ccm process in a coordinated manner. Module 1 (right) transports heme b across the membrane while Module 2 (left) translocates and chaperones ligation-competent apocyts c. Module 3 (center) traps the Ccm substrates heme b and apocyt c (provided by the Module 1 and Module 2, respectively) and catalyzes stereo-specifically the thioether bonds between the appropriate vinyl groups of heme and the thiol groups of the heme-binding motifs of apocyts c.

Table 1.

Role of the different components of Ccm-System I

| Ccm protein | Structural Features | Proposed Funtion |

|---|---|---|

| CcmA | Peripheral membrane protein with ATP-binding domain Walker A (GX4GKS/T) and Walker B motifs (R/KX3GX3LX3D) | Part of the CcmABCD complex, a putative ABC-type transporter; required for ATP-dependent “release” of holoCcmE from the CcmCDE complex |

| CcmB | Six TM helices and a conserved FXXDXXDGSL motif | Part of the CcmABCD complex, a putative ABC-type transporter; required for the “release” of holoCcmE from the CcmCDE complex |

| CcmC | Six TM helices with a tryptophanrich (WGXF/Y/WWXWDXRLT) motif and two conserved His residues | Part of the CcmABCD complex, a putative ABC-type transporter; loads heme into apoCcmE and provides axial ligands to the heme-iron; acts as a CcmE-specific heme lyase |

| CcmD | Small single TM helix protein with no conserved domains | Part of the CcmABCD complex, a putative ABC-type transporter; improves CcmC activity; required for the release of holoCcmE from the CcmCDE complex |

| CcmE | Single TM helix with a periplasmic domain containing a conserved HXXXY motif | Heme chaperone binding covalently vinyl-2 of heme via a conserved His residue; delivers heme to the apocyt c substrates |

| CcmF | Eleven TM helices with a tryptophan-rich (WGGXWFWDPVEN) motif, and four conserved His residues | Part of the CcmFHI heme ligation complex; interacts with apocyts c and holoCcmE, and suggested to reduce heme in holoCcmE for its transfer to apocyts c |

| CcmG | Single TM helix with a periplasmic domain containing a thioredoxin motif (CXXC) | Binds poorly apocyts c; involved in thioreduction of apocyts c either directly, or indirectly via CcmH, or by resolving a CcmH-apocyt c mixed-disulfide |

| CcmH | Single TM helix with a periplasmic domain containing a thioredoxin-like motif (LRCXXC) | Part of the CcmFHI heme ligation complex; interacts with apocyts c and suggested to reduce its disulfide bond to enable stereo-specific heme ligation |

| CcmI | Two TM helices, linked by a cytoplasmic loop with a leucine-zipper-like motif, and a large periplasmic domain containing three TPR repeats | Part of the CcmFHI heme ligation complex; is an apocyt c chaperone binding to the C-terminal portion of the apocyt c via its periplasmic domain |

3.1 Module 1. CcmABCD and CcmE: Heme b Translocation and Relay to Module 3

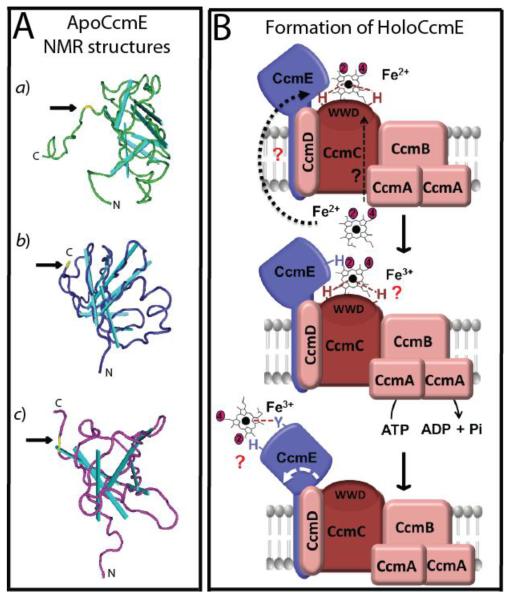

CcmABCD are homologous to the ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporters and are responsible for conveying heme b to the periplasm and loading it to the heme-chaperone CcmE. CcmA is a peripheral membrane protein with a typical ATP-binding region containing Walker A (GX4GKS/T) and B (R/KX3GX3LX3D) domains [43]. CcmB and CcmC are integral membrane proteins with six transmembrane (TM) helices each. In addition, CcmB has a conserved FX2DX2DGSL motif, and CcmC has a hydrophobic tryptophan rich (WWD) motif flanked by two conserved His residues exposed to the periplasm [44–46]. CcmC belongs to the heme handling protein (HHP) family [47] and is the only protein strictly necessary for loading heme b to apoCcmE to synthesize holoCcmE [48]. Together with CcmC, CcmB is required for membrane localization of CcmA to form a putative ABC-type transporter complex with a stoichiometry of CcmA2BC [31, 49–52]. CcmD is a small polypeptide (~60 amino acid residues) with a single TM helix and a hydrophilic C-terminal domain [53, 54] that enhances CcmC activity for holoCcmE synthesis [54, 55]. Hence, CcmC and CcmD are referred to as a CcmE-specific heme lyase [48, 56]. CcmE is a member of the oligobinding (OB) family of proteins [57], has a single TM helix, and a large periplasmic β barrel core domain ending with a flexible C-terminus [58–60] (Fig. 3A). It binds covalently and transiently one vinyl group (probably vinyl-2) of heme b via its conserved and surface-exposed His residue within the HXXXY domain [61–63]. Mutation of this His residue prevents holoCcmE formation, and blocks cyts c production [48, 64]. In species where the His residue is naturally replaced by a Cys [27] both the structure and production of holoCcmE via CcmABCD are conserved [60, 65] (Figs. 3A and B).

Figure 3. Module 1 carries out heme b translocation and holoCcmE production.

A. ApoCcmE structures. Solution NMR structures of the periplasmic C-terminal domains of apoCcmE from different organisms: a) E. coli (PDB ID: 1SR3) [59], b) Shewanella putrefaciens (PDB ID:1J6Q) [58] and c) Desulfovibrio vulgaris (PDB ID: 2KCT) [60], showing their β-barrel (cyan) OB fold and the flexible C-terminal portions. The conserved His (a, b) and Cys (c) residues that bind covalently heme b are represented in yellow, and indicated with an arrow. B. HoloCcmE formation. Specific proteins of Module 1 are depicted as forming a membrane integral complex composed of the ATP-binding CcmA and its partners CcmB, CcmC, CcmD and the heme chaperone CcmE in a putative stoichiometry of CcmA2BCDE. Heme b is transported across the membrane by an unknown mechanism and mediates the formation of a CcmCD-heme-CcmE complex. Heme b (possibly via its vinyl -2 group) becomes covalently bound to the His residue at the conserved heme binding HXXXY domain located at the surface of apoCcmE. Oxidation of heme-iron (Fe3+) and ATP-hydrolysis are postulated to promote a conformational change (indicated by a white arrow), releasing holoCcmE from the stable CcmCD-heme-CcmE, possibly by exchanging the heme-iron axial ligands provided by CcmC with the CcmE Tyr residue. This event renders holoCcmE ready to precede as a heme b donor to the apocyt c substrates. Dotted black arrow corresponds to a plausible CcmC-independent heme delivery route, and “?” point out unknown steps of the process.

Mutants lacking CcmABCD lack cyts c but still produce periplasmic cyts b (i.e., non covalent heme b containing cyts) [66], indicating that these components are specific to the Ccm process. As CcmC alone is sufficient for holoCcmE formation [48], CcmAB were proposed [56, 67] to transport an unknown molecule (e.g., a reductant) different from heme b [55, 68]. How heme b is translocated across the membrane and covalently ligated to CcmE remains unknown. CcmC binds heme b non-covalently via its two TM His residues [45, 69] only in the presence of apoCcmE [46], and lacks any obvious heme delivery pathway unlike its HHP homologues CcmF and CcsAB of the Systems I and II, respectively. Once heme b reaches the periplasm by an unknown mechanism, it is thought to interact with the WWD domain of CcmC [68] and the hydrophobic heme-binding region of apoCcmE [63, 64]. Heme is ligated covalently to the His residue of CcmE, and the two His residues of CcmC provide the heme-iron axial ligands to form a stable CcmCD-heme-CcmE complex containing oxidized heme-iron (Fe3+) [45, 46] (Fig. 3B). The catalytic mechanism behind this unusual bond between the N-δ1 of His and the β-carbon of heme b vinyl group is not yet established [62]. Imidazole radical (from the His residue) formation with reduced heme-iron (Fe2+), or Michael's addition with oxidized heme-iron (Fe3+), (in both cases involving an unknown redox component) have been proposed [13].

How heme b is delivered from holoCcmE to apocyts c also remains unclear. In the absence of CcmAB mediated ATP hydrolysis, CcmCD still forms holoCcmE but no cyts c production occurs [48, 56, 65]. Current models suggest that ATP hydrolysis by CcmAB may be required for the “release” of holoCcmE from a stable complex it forms with CcmCD [55]. The His residues of CcmC that act as the heme-iron axial ligands are then replaced by a Tyr residue and another unidentified ligand located at the heme binding domain of CcmE [70] (Fig. 3B). Heme b oxidation by an unknown compound is followed by its covalent ligation to CcmE via CcmC with the assistance of CcmD. ATP hydrolysis by CcmAB seems needed to induce a “change” in the stable CcmCD-heme-CcmE complex to render holoCcmE proficient for the next steps of Ccm. Recently, a CcmE-heme-apocyt c mimic (i.e., cyt c-b562, an artificial four helical bundle apocyt c engineered by insertion of a heme-binding site in E. coli apocyt b562) intermediate, with one of the heme b vinyl groups covalently linked to the His of CcmE and the other to a Cys residue of apocyt c derivative, was isolated in vivo [71]. Absence of the conserved His residues of CcmC, or ATP hydrolysis by CcmAB, prevents the formation of this intermediate, which is accumulated in the absence of CcmFHG [71]. Additionally, in vitro transfer of heme from holoCcmE to an apocyt c was previously reported [72], and our recent in vitro studies indicate that apoCcmE devoid of heme b also interacts with apocyt c2 provided that it has an intact heme-binding site (preferably containing a disulfide bond) [73]. Clearly, these intermediates are likely to represent step(s) of the Ccm process, but their additional Ccm components and their role(s), if any, remains undefined. Recently, we found that apoCcmE forms a ternary complex with apocyt c2 and CcmI [73], and using n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) dispersed membrane fractions, showed that both CcmI and CcmH co-purify with apoCcmE. In addition, holoCcmE was also shown to form a CcmF-heme-CcmE complex in the absence of CcmGH [74].

In A. thaliana, CcmABCE proteins are the orthologues of the bacterial CcmABCE components, but CcmD is missing. Functional complementation of an E. coli mutant lacking CcmE with its A. thaliana counterpart, and related protein interaction studies, indicated that the mitochondrial CcmE binds heme b via a conserved His residue, and that CcmABC form an ABC-type transporter with ATP hydrolysis activity [49, 75, 76].

Finally, why the species with a His to Cys variant of CcmE also lack CcmG and CcmH (see below) [77], how the reduced heme-iron (Fe2+) is conveyed to CcmC subsequent to its synthesis by ferrochelatase, and whether ATP hydrolysis by CcmAB is required to transport an unknown compound, remain elusive.

3.2 Module 2. CcmG and CcmH: Apocyt c Thioredox and Relay to Module 3

The thiol-oxidoreductase CcmG together with CcmH maintain the apocyts c ligation-competent (i. e., in their reduced state). CcmH being a subunit of the heme ligation complex, CcmFHI, it is also a component of Module 3 (see below). Apocyts c with their signal sequences are usually translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane via the general secretory (Sec) pathway prior to their maturation and assembly into their respective complexes. Once on the p-side (periplasm in bacteria) the Cys residues of the heme-binding motifs are oxidized via the DsbA-DsbB oxidative protein-folding pathway [12, 13, 78, 79]. DsbA is a strong periplasmic thiol-oxidoreductase that acts upon a wide variety of Cys containing substrates via its highly reactive thioredoxin-like (CXXC) domain [80]. Its partner DsbB is an integral membrane protein that contains two thioredoxin-like motifs, and reoxidizes DsbA by shuttling the reducing power to the membrane quinol pool, and eventually to the electron transport chain [81]. This periplasmic disulfide bond formation pathway is important for folding of extracytoplasmic proteins to provide resistance to proteolysis and to induce conformational changes required for their functions and regulations [82] (Fig. 4A). In the case of the apocyts c, any intra-molecular disulfide bond formed at their heme-binding sites needs to be reduced for covalent heme ligation to occur. This reduction is attributed to CcmG, and probably involves CcmH. CcmG receives its reducing equivalents from the cytoplasmic thioredoxin TrxA across the membrane via CcdA [83–85]. R. capsulatus CcdA is an integral membrane protein with six TM helices containing two redox-active Cys residues located at its first and fourth TM helices [83, 84, 86, 87]. E. coli DsbD, which is a homologue of CcdA, is a larger membrane protein containing three distinct domains, each with a pair of Cys [87, 88]. CcdA and DsbD are dedicated thiol-oxidoreductases [87], and besides their involvement in cyt c biogenesis, they are also involved in virulence gene expression or sporulation in some organisms [89]. CcmG is anchored to the membrane via its unprocessed N-terminal signal sequence, has a bone fide thioredoxin fold with a CXXC motif, and is implicated in direct dithiol-disulfide oxidoreduction of apocyts c disulfide bonds. Its active site is unusually acidic and has a groove which, in resemblance with its System II homologue ResA [90], might be required for its interaction with CcdA or its substrate(s) [85, 91]. Like CcdA, the Cys residues of CcmG are essential for Ccm [92–94]. Mixed disulfide bond formation in vivo was detected between CcmG and CcdA, proving their direct interactions during thioreduction [83, 85] (Fig. 4A). Addition of exogenous thiol compounds is able to alleviate the Ccm deficiency in CcmG and CcdA mutants, confirming their roles in maintaining reduced the apocyt c heme-binding site thiol groups [84, 93, 95, 96]. In the absence of DsbA-DsbB, production of cyts c is decreased but not completely abolished, and in some cases, this can be rescued by addition of oxidants [93, 96–100]. We found that absence of DsbA or DsbB suppresses Ccm deficiency of R. capsulatus CcdA-null [96, 98] or CcmG-null mutants [93], indicating that thioreduction via CcdA-CcmG is dispensable for Ccm in the absence of thio-oxidation by DsbA-DsbB [93]. Similar findings were also shown recently with E. coli [100], reinforcing the proposal that DsbA-DsbB and CcdA-CcmG form a thioredox loop (Fig. 4A). This situation seen in mutants lacking a thioredox loop resembles the plant mitochondrial case as in A. thaliana neither a DsbA-DsbB dependent oxidative pathway, nor a CcmG orthologue was identified. In addition to thioreduction, R. capsulatus CcmG also participates in chaperoning the apocyts c as its Cys-less mutant improves cyts c production in the absence of DsbA [93].

Figure 4. Thioredox reactions between the CcdA, CcmG, CcmH and apocyts c during Ccm.

A. DsbA-DsbB and CcdA-CcmG thioredox loop. Components of Module 2 are shown together with the general secretory (SEC) pathway responsible for translocation and cleavage of the signal sequences of apocyts c. DsbA and DsbB are thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases thought to oxidize the thiol groups of the heme-binding motif Cys residues (C1 and C2) of apocyts c. The disulfide bonds thus formed are then reduced by the CcdA and CcmG component of the Ccm process, forming a thioredox loop of unknown role. In the absence of the oxidative pathway (DsbA or DsbB), CcdA and CcmG are not required as the apocyts c stay reduced [93]. This possibility suggests that CcmG (recycled by CcdA) reduces directly the apocyts c disulfide bonds, as indicated by the thioredox compensation observed only between the DsbA-DsbB and CcdA-CcmG couples [93]. B. CcmG-CcmH-apocyts c thiol-disulfide cascade. The earlier proposed thioreduction pathway involves CcmG, CcmH and apocyt c, and is based on combined in vivo and in vitro studies including the Em determination of purified CcmG (Em= −300 mV), CcmH (Em= −210 mV) and an 11 amino acid residues peptide mimicking apocyt c (Em= −170 mV) [107]. This possibility suggests that CcmH (recycled by CcdA and CcmG) reduces directly the apocyt c disulfide bonds substrate. C. A mixed-disulfide between CcmH and apocyt c resolved by CcmG. This possibility suggests that CcmG reduces a mixed-disulfide formed between CcmH and apocyt c (rather than oxidized CcmH or apocyt c). It is based on the finding that CcmG is able to reduce a CcmH-TNB mixed disulfide bond, but not an oxidized CcmH [110], and requires that either apocyt c or CcmH pairs needs to be previously reduced (and the other oxidized) to form the mixed disulfide bond, but how this is accomplished and whether it involves CcmG is unclear.

CcmH has a single TM helix and an unusual three helix-bundle fold distinct from other thioredoxin-like proteins, with a redox active LRCXXCQ motif facing the periplasm [101–103]. Plant CcmH resembles its bacterial counterpart with a membrane anchor and a CXXC motif containing N-terminal domain facing the inter-membrane space. It can interact and reduce an apocyt c mimic peptide in spite of its different active site (VRCTECG) [104]. E. coli CcmH is a fusion protein with a N-terminal domain corresponding to the redox-active CcmH and a C-terminal portion homologous to CcmI (see below) as found in other organisms, such as R. capsulatus and P. aeruginosa [103, 105]. Both Cys residues of E. coli CcmH are important for Ccm but not essential under all conditions [105, 106]. No thioredox compensation occurs between R. capsulatus mutants lacking both DsbA and CcmH, suggesting that the role of CcmH is not restricted to apocyts c reduction [93].

Currently, the exact sequence of events that occur during the thioreduction of apocyts c is not clear, and different scenarios are plausible (Figs 4A, B, C). Earlier studies using mutants in vivo, and purified R. capsulatus and E. coli samples in vitro, determined the Em and pKa values of the redox active Cys residues of CcmG, CcmH and apocyts c. These studies proposed a linear dithiol-disulfide cascade, with CcmG reducing CcmH, and CcmH reducing the oxidized apocyts c substrates [92, 103–105, 107–109] (Fig. 4B). Alternative models were later proposed based on the unusual thioredoxin fold and redox properties of CcmH, and on the fact that P. aeruginosa CcmG cannot reduce in vitro the disulfide of CcmH although it does so a TNB-CcmH mixed disulfide [110]. These findings led to the suggestion that CcmH may form an inter-molecular mixed-disulfide bond with apocyts c that is resolved by CcmG, and oxidixed CcmG is subsequently reduced by CcdA (or DsbD) [101, 105, 108, 110] (Fig 4C). In the absence of in vivo and in vitro evidences showing that CcmG reduces CcmH and/or apocyts c, and/or detection of mixed-disulfides between these proteins, the order of the thio-reductive events remains unclear. Establishing the exact sequence of the thioredox reactions between the apocyts c, CcmG and CcmH is crucial for understanding the mechanism of heme ligation, especially if CcmH plays a key role in ensuring the stereo-specificity of the thiother bonds [12].

3.3 Module 3. CcmFHI: Apocyt c and Heme Ligation

Heme-apocyt c ligation per se is attributed to Module 3, which involves in R. capsulatus at least the CcmF, CcmH and CcmI components that form a membrane-integral complex (CcmFHI) [111]. The E. coli CcmFH complex is a functional homologue of R. capsulatus CcmFHI [112], whereas the plant (A. thaliana) mitochondrial CcmF is split into three proteins (CcmFN1, CcmFN2 and CcmFC). CcmFN1 and CcmFN2 interact with each other and with CcmH to form a large complex, but a CcmI orthologue seems to be absent [113, 114]. CcmI is a bipartite membrane protein that acts as a chaperone for apocyts c. Its N-terminal CcmI-1 domain has two TM helices and a cytoplasmic loop with a leucine zipper-like motif, whereas its CcmI-2 domain is a large periplasmic C-terminal extension decorated with three tetratricopeptide repeats (TPR) [115–117]. TPR are ubiquitous protein-protein interaction domains composed of arrays of 34 hydrophobic residues forming two antiparallel α-helices [118]. Early genetic studies indicated that the two domains of CcmI have different functions [115, 119–121]. In R. capsulatus, CcmI-1 is required for the production of all cyts c whereas CcmI-2 is dispensable for the C-terminally membrane-anchored cyt c1 [115]. Furthermore, overproduction of CcmF and CcmH, or CcmI-1 overcomes partially, while additional overproduction of CcmG, CcmI-2 or apocyt c2 overcomes fully, the CcmI defects. These findings led to the proposal that CcmI-1 together with CcmF and CcmH are responsible for heme ligation, whereas CcmI-2 and CcmG deliver ligation-competent apocyts c to CcmFHI for stereo-specific heme-apocyt c ligation [116, 122, 123]. CcmF is a large integral membrane protein that contains heme b [45]. It belongs to the HHP family, like CcmC, and has a periplasmic WWD motif [47]. Of its four conserved His residues, two are ligands of its heme b cofactor [124], whereas the remaining two coordinate heme b of holoCcmE to form a stable CcmF-heme-CcmE complex [45, 74] at least in the absence of CcmGH. It appears that CcmF binds holoCcmE better than apoCcmE [74], and it can be reduced by quinol (QH2) in vitro. CcmF is proposed to reduce the oxidized heme-iron (Fe3+) in holoCcmE, which is a requisite for thioether bond formation. Topological models based on amino acid similarities with other proteins known to interact with quinones identified a putative quinone-binding site in a periplasmic loop of CcmF [45, 74]. However, mutations of this quinol binding residues do not abolish cyt c production [65], leaving unknown how the oxidized heme-iron (Fe3+) of holoCcmE is reduced.

Recently, we showed that CcmI binds directly to the C-terminal helix of class I apocyt c2, but not holocyt c2. This interaction is mainly via the large periplasmic domain of CcmI (CcmI-2), in agreement with earlier genetic data, which inferred that CcmI is an apocyt c chaperone [117]. Similar observations were also reported for P. aeruginosa CcmI and apocyt c551 [125], as well as the CcmI orthologue NrfG and the pentaheme apocyt c NrfA in E. coli [126]. So far only A. thaliana CcmFN2 was reported to interact with both apocyts c and c1 in a yeast two-hybrid assay [113]. Interestingly, using DDM-dispersed R. capsulatus membranes, we found that not only CcmI [117] but also CcmH and CcmF can co-purify with apocyt c2 (Verissimo and Daldal, unpublished), in contrast with E. coli CcmF that seems unable to interact with apocyts c [112]. We observed that co-purification of CcmF with apocyt c2 is impaired in the absence of its Cys residues or C-terminal helix, and enhanced by addition of purified CcmI (Verissimo and Daldal, unpublished). These findings suggest that CcmI-apocyt c2 interactions might facilitate binding of apocyt c2 to CcmF, probably indirectly. In addition, co-purification assays done in vitro using CcmFHG-enriched solubilized membrane fractions supplemented with purified CcmI revealed that CcmG also co-purifies with CcmI. Thus, R. capsulatus CcmFHI heme ligation complex might also contain CcmG (Verissimo and Daldal, unpublished). These findings are in agreement with earlier genetic data, which inferred that CcmG and CcmI-2 are functionally related [116], possibly chaperoning apocyts c [93]. Direct interactions between CcmG and the heme ligation component CcmH are readily conceivable as these proteins work together during thioreduction of apocyts c. Overall findings therefore suggest that R. capsulatus heme ligation complex CcmFHI also contains CcmE and CcmG.

4. Do the Ccm Components Form a Membrane-integral Supercomplex?

The E. coli Ccm components form a single operon, whose products were initially thought to co-localize in the inner membrane, forming a large `maturase” complex [127]. However, in other organisms, these components are dispersed into two (e.g., ccmABCDG and ccmIEFH in Bradyrhizobium japonicum [128]) or more (e.g., ccmABCDG, ccmFH, ccmE and ccmI in R. capsulatus [84, 115, 129]) genomic loci. In A. thaliana, ccmBC, ccmFN1, ccmFN2, and ccmFC genes are present in different loci on the mitochondrial genome [130], whereas ccmA, ccmE and ccmH are nuclear-encoded [49, 76, 104]. Regardless of the genomic distributions, various complexes containing Ccm components were reported. Different genetic strategies were employed to ease the accumulation and isolation of these complexes often from DDM solubilized membrane fractions. However, the nonionic detergent DDM, which is widely used for successful purification of membrane complexes, is known to disrupt membrane supercomplexes (e.g., mitochondrial case) [131]. Large supercomplexes formed of many proteins weakly interacting with each other are difficult to isolate, and require specific lipid dispersion conditions with mild detergents (e.g, digitonine or amphipoles) to keep them intact [131]. Whether the Ccm components form altogether a highly stable membrane supercomplex (dubbed a “Ccm machine”) is unknown. Earlier observations in both bacteria and plant mitochondria suggested the occurrence of Ccm components in large membrane entities of unknown compositions. Co-localization of R. capsulatus heme ligation components CcmFHI in fractions corresponding to ~800 kDa molecular weight, separated by size exclusion chromatography was reported [111]. Large complexes containing CcmF and CcmH in A. thaliana (~500kDa) [104], and CcmF in wheat (~700 kDa) mitochondria [132] were also described. Yet, earlier experiments indicated that apoCcmE co-imunoprecipitated with CcmF [112], and CcmC co-immunoprecipitated with apoCcmE and CcmD, but not with CcmF in the presence or absence of CcmE [133]. These data precluded the possibility of a CcmCD-CcmE-CcmF complex in E. coli membranes. However, the experiments used a complete ccm-deletion background, expressing only the tested Ccm components, and the reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation assays were inconclusive. We recently found that R. capsulatus apoCcmE interacts directly with CcmI and CcmH, but not with CcmF in vitro [73]. In agreement with these findings, an E. coli CcmF-heme-CcmE complex was recently isolated from a CcmHG-null background in the presence of heme. It was also shown that, unlike holoCcmE, apoCcmE bound CcmF poorly [74]. Additional recent findings that documented specific interactions between the Ccm components of different functional modules (e.g., apoCcmE binding CcmI) led us to consider the occurrence in R. capsulatus of a CcmABCD-CcmE-CcmFHI-CcmG supercomplex (a Ccm machine) that may catalyze the entire Ccm process. If such a machine exists, then the role of CcmE as a key heme-shuttle between the heme handling (CcmABCD) and the heme ligation (CcmFHI) complexes, is particularly attractive as this would render unnecessary the earlier postulated diffusional movement of CcmE between the Ccm complexes. The presence of CcmD, a single transmembrane domain (STMD) topology subunit, known to be important for heme ligation, may mediate tight associations between CcmABCDE and CcmFHI. STMD topology subunits seem usually involved in the assembly, stabilization and regulation of large membrane supercomplexes [134]. The occurrence of a large Ccm machine may facilitate concerted availability of the heme and apocyt c substrates to enhance the efficiency of maturation of c-type cyts. This issue might become even more important in the case of multiheme cyts, where several hemes have to be ligated properly. In this scenario, CcmI may keep the apocyts trapped in the Ccm machine while the remaining components act sequentially to ensure stereo-specific heme ligation and correct axial coordination of the heme iron.

Earlier we developed a hypothetical mechanistic model describing the Ccm process [12]. Here, we updated and further refined this working model in the light of the recent developments discussed above, and the salient aspects of this hypothetical Ccm machine are depicted in Fig. 5. Accordingly, in the absence of heme, apoCcmE is postulated to be associated more closely with CcmI-CcmH than CcmCD (step 1). Upon the availability of an apocyt c, CcmI (which is together with CcmFH) binds its C-terminus and apoCcmE recognizes its heme-binding site. Once apocyt c is trapped by CcmI(FH), a mixed disulfide bond is formed between its heme-binding Cys1 and oxidized CcmH (step 2). The identity of the Cys residue that reacts with CcmH (i.e., the availability of a free heme-binding Cys2) is critical for stereo-specific heme ligation. Once heme b is available, a stable non-covalent apoCcmE-heme-CcmCD complex is formed, with CcmC providing a heme platform via its WWD domain and the heme-iron axial His ligands (step 3, white arrow) (see also Fig. 3B). Oxidation of heme-iron (Fe3+) occurs together with covalent ligation of (probably) vinyl-2 of heme to the conserved His residue of apoCcmE to produce holoCcmE. Following the CcmAB mediated ATP hydrolysis, a conformational change occurs and CcmC releases holoCcmE (coordinating heme b via a Tyr residue at this stage, not shown) for interaction with the heme ligation components (step 4). Next, similar to CcmC, CcmF provides a heme scaffold via its WWD domain and conserved His residues, interacting via heme with holoCcmE (step 5, white arrow). Upon reduction of the heme-iron (Fe2+), (probably via the heme cofactor of CcmF) the heme b vinyl-4 that is available interacts with the reduced Cys2 thiol of apocyt c to form the first thioether bond (step 6). Next, the CcdA-reduced CcmG (or possibly the free Cys of CcmH) resolves the mixed disulfide between CcmH and apocyt c Cys1, rendering it ready to interact with heme b (step 7). Upon cleavage of the covalently attached heme from the His of CcmE by an unknown mechanism, the second thioether bond between vinyl-2 and apocyt Cys1 is formed (step 8). Clearly, many of these steps and their chronological orders are hypothetical, and many alternative possibilities are plausible at present. Yet, we note that the recent in vivo trapped CcmCD-heme-CcmE [45], CcmE-heme-apocyt c [71] and CcmF-heme-CcmE [74] intermediates, as well as the in vitro observed CcmI-apocyt c2– apoCcmE [73], CcmHI-apoCcmE [73] complexes are consistent with this working model. It is hoped that elucidation of the nature and sequence of the thioredox events involving CcmG, CcmH and apocyts c will further define the mechanism of function of the “Ccm machine”.

Figure 5. A possible mechanism for stereo-specific thioether bond formation by the Ccm machine.

This hypothetical model depicts all of the Ccm components as a multi subunit supercomplex, facilitating substrate accessibility (heme b and apocyt c) to the heme ligation site (1). Upon formation of the mixed disulfide bond between apocyt c Cys1 and CcmH (one of them reduced previously by CcmG) (2), the thiol of Cys2 is free to react with heme b to form the first thioether bond (3). Following heme b transfer across membrane, holoCcmE produced by CcmCD carries heme b via a unique covalent bond between a His residue and heme vinyl-2 (4). HoloCcmE conveys heme b to CcmF upon ATP hydrolysis by CcmAB, and the free vinyl-4 of heme b ligates covalently to Cys2 thiol of the heme-binding (C1XXC2H) motif of apocyt c site (5). CcmF coordinates axially heme b of holoCcmE (not shown), and probably reduces heme-iron via QH2 oxidation, to free its vinyl-2 group (6). Upon resolution of the mixed disulfide bond between apocyt c and CcmH by CcmG (7), the free vinyl-2 of heme b reacts with apocyt c Cys1 to form the second thioether bond (8) and completes the cycle. Heme b thus incorporated into the apocyts c then drives its folding into a mature and active holocyt c (not shown). See the text for a detailed description of this hypothetical model.

In summary, this review describes the components and the known intermediates of Ccm-System I, and explores the occurrence of a structural multi subunit supercomplex (Ccm machine) formed of functional modules. The mechanism behind the unusual covalent bond formed between heme b and CcmE-His residue, the interactions between various Ccm components, their structures, the chronological sequence of the different intermediates and their interactions with the apocyts c and heme substrates, remain unclear. Again, the order of events that occur during the thioredox reactions leading to the universally conserved stereo-specific heme ligation, and the occurrence and composition of a Ccm supercomplex are among the many issues of critical importance that awaiting answers in future studies for a complete understanding of a biologically significant process, like Ccm.

HIGHLIGHTS

Cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) is the covalent ligation of heme b to an apocyt c

Ccm is a intricate post-translational protein modification process

Ccm-System I involves ten membrane-bound proteins working together

The Ccm proteins are proposed to form a large multi subunit supercomplex

A mechanistic view of stereo-specific thioether bond formation is presented

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by grants from the NIH GM 38237 and Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of DOE DE-FG02-91ER20052.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Moore GR, Pettigrew GW. Cytochromes c Evolutionary, Structural and Physicochemical Aspects. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bertini I, Cavallaro G, Rosato A. Cytochrome c: occurrence and functions. Chem Rev. 2006;106:90–115. doi: 10.1021/cr050241v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome c mediated apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bowman SE, Bren KL. The chemistry and biochemistry of heme c: functional bases for covalent attachment. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:1118–1130. doi: 10.1039/b717196j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Allen JW, Leach N, Ferguson SJ. The histidine of the c-type cytochrome CXXCH haem-binding motif is essential for haem attachment by the Escherichia coli cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) apparatus. Biochem J. 2005;389:587–592. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Allen JW, Ginger ML, Ferguson SJ. Maturation of the unusual single-cysteine (XXXCH) mitochondrial c-type cytochromes found in trypanosomatids must occur through a novel biogenesis pathway. Biochem J. 2004;383:537–542. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Einsle O, Messerschmidt A, Stach P, Bourenkov GP, Bartunik HD, Huber R, Kroneck PM. Structure of cytochrome c nitrite reductase. Nature. 1999;400:476–480. doi: 10.1038/22802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Herbaud ML, Aubert C, Durand MC, Guerlesquin F, Thony-Meyer L, Dolla A. Escherichia coli is able to produce heterologous tetraheme cytochrome c3 when the ccm genes are co-expressed. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1481:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Aragao D, Frazao C, Sieker L, Sheldrick GM, LeGall J, Carrondo MA. Structure of dimeric cytochrome c3 from Desulfovibrio gigas at 1.2 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:644–653. doi: 10.1107/s090744490300194x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hartshorne RS, Kern M, Meyer B, Clarke TA, Karas M, Richardson DJ, Simon J. A dedicated haem lyase is required for the maturation of a novel bacterial cytochrome c with unconventional covalent haem binding. Molecular microbiology. 2007;64:1049–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ambler RP. Sequence variability in bacterial cytochromes c. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1058:42–47. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sanders C, Turkarslan S, Lee DW, Daldal F. Cytochrome c biogenesis: the Ccm system. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kranz RG, Richard-Fogal C, Taylor JS, Frawley ER. Cytochrome c biogenesis: mechanisms for covalent modifications and trafficking of heme and for heme-iron redox control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:510–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00001-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stevens JM, Mavridou DA, Hamer R, Kritsiligkou P, Goddard AD, Ferguson SJ. Cytochrome c biogenesis System I. FEBS J. 2011;278:4170–4178. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Simon J, Hederstedt L. Composition and function of cytochrome c biogenesis System II. FEBS J. 2011;278:4179–4188. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Allen JW. Cytochrome c biogenesis in mitochondria--Systems III and V. FEBS J. 2011;278:4198–4216. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].de Vitry C. Cytochrome c maturation system on the negative side of bioenergetic membranes: CCB or System IV. FEBS J. 2011;278:4189–4197. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Facey SJ, Kuhn A. Biogenesis of bacterial inner-membrane proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2343–2362. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Natale P, Bruser T, Driessen AJ. Sec- and Tat-mediated protein secretion across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane--distinct translocases and mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1735–1756. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moore CM, Helmann JD. Metal ion homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Goldman BS, Gabbert KK, Kranz RG. Use of heme reporters for studies of cytochrome biosynthesis and heme transport. Journal of bacteriology. 1996;178:6338–6347. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6338-6347.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kranz R, Lill R, Goldman B, Bonnard G, Merchant S. Molecular mechanisms of cytochrome c biogenesis: three distinct systems. Molecular microbiology. 1998;29:383–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sanders C, Lill H. Expression of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cytochromes c in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pitts KE, Dobbin PS, Reyes-Ramirez F, Thomson AJ, Richardson DJ, Seward HE. Characterization of the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 decaheme cytochrome MtrA: expression in Escherichia coli confers the ability to reduce soluble Fe(III) chelates. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27758–27765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Braun M, Rubio IG, Thony-Meyer L. A heme tag for in vivo synthesis of artificial cytochromes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:234–239. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Allen JW, Tomlinson EJ, Hong L, Ferguson SJ. The Escherichia coli cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) system does not detectably attach heme to single cysteine variants of an apocytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33559–33563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Allen JW, Harvat EM, Stevens JM, Ferguson SJ. A variant System I for cytochrome c biogenesis in archaea and some bacteria has a novel CcmE and no CcmH. FEBS letters. 2006;580:4827–4834. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Allen JW, Sawyer EB, Ginger ML, Barker PD, Ferguson SJ. Variant c-type cytochromes as probes of the substrate specificity of the E. coli cytochrome c maturation (Ccm) apparatus. Biochem J. 2009;419:177–184. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081999. 172 p following 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Howe G, Merchant S. The biosynthesis of membrane and soluble plastidic c-type cytochromes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is dependent on multiple common gene products. EMBO J. 1992;11:2789–2801. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05346.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Le Brun NE, Bengtsson J, Hederstedt L. Genes required for cytochrome c synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular microbiology. 2000;36:638–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Feissner RE, Richard-Fogal CL, Frawley ER, Loughman JA, Earley KW, Kranz RG. Recombinant cytochromes c biogenesis systems I and II and analysis of haem delivery pathways in Escherichia coli. Molecular microbiology. 2006;60:563–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goddard AD, Stevens JM, Rondelet A, Nomerotskaia E, Allen JW, Ferguson SJ. Comparing the substrate specificities of cytochrome c biogenesis Systems I and II: bioenergetics. FEBS J. 2010;277:726–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Richard-Fogal CL, San Francisco B, Frawley ER, Kranz RG. Thiol redox requirements and substrate specificities of recombinant cytochrome c assembly systems II and III. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:911–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zollner A, Rodel G, Haid A. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CYT2 gene encoding cytochrome c1 heme lyase. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:1093–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Dumont ME, Ernst JF, Hampsey DM, Sherman F. Identification and sequence of the gene encoding cytochrome c heme lyase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1987;6:235–241. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bernard DG, Gabilly ST, Dujardin G, Merchant S, Hamel PP. Overlapping specificities of the mitochondrial cytochrome c and c1 heme lyases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49732–49742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schwarz QP, Cox TC. Complementation of a yeast CYC3 deficiency identifies an X-linked mammalian activator of apocytochrome c. Genomics. 2002;79:51–57. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Corvest V, Murrey DA, Hirasawa M, Knaff DB, Guiard B, Hamel PP. The flavoprotein Cyc2p, a mitochondrial cytochrome c assembly factor, is a NAD(P)H-dependent haem reductase. Molecular microbiology. 2012;83:968–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.07981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Verissimo AF, Sanders J, Daldal F, Sanders C. Engineering a prokaryotic apocytochrome c as an efficient substrate for Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome c heme lyase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stevens JM, Zhang Y, Muthuvel G, Sam KA, Allen JW, Ferguson SJ. The mitochondrial cytochrome c N-terminal region is critical for maturation by holocytochrome c synthase. FEBS letters. 2011;585:1891–1896. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].San Francisco B, Bretsnyder EC, Kranz RG. Human mitochondrial holocytochrome c synthase's heme binding, maturation determinants, and complex formation with cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E788–797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213897109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Asher WB, Bren KL. Cytochrome c heme lyase can mature a fusion peptide composed of the amino-terminal residues of horse cytochrome c. Chem Commun (Camb) 2012;48:8344–8346. doi: 10.1039/c2cc31112g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Walker JE, Saraste M, Runswick MJ, Gay NJ. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Goldman BS, Beck DL, Monika EM, Kranz RG. Transmembrane heme delivery systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Richard-Fogal CL, Frawley ER, Bonner ER, Zhu H, San Francisco B, Kranz RG. A conserved haem redox and trafficking pathway for cofactor attachment. EMBO J. 2009;28:2349–2359. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Richard-Fogal C, Kranz RG. The CcmC:heme:CcmE complex in heme trafficking and cytochrome c biosynthesis. J Mol Biol. 2010;401:350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lee JH, Harvat EM, Stevens JM, Ferguson SJ, Saier MH., Jr. Evolutionary origins of members of a superfamily of integral membrane cytochrome c biogenesis proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:2164–2181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schulz H, Fabianek RA, Pellicioli EC, Hennecke H, Thony-Meyer L. Heme transfer to the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation requires the CcmC protein, which may function independently of the ABC-transporter CcmAB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6462–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rayapuram N, Hagenmuller J, Grienenberger JM, Giege P, Bonnard G. AtCCMA interacts with AtCcmB to form a novel mitochondrial ABC transporter involved in cytochrome c maturation in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Goldman BS, Beckman DL, Bali A, Monika EM, Gabbert KK, Kranz RG. Molecular and immunological analysis of an ABC transporter complex required for cytochrome c biogenesis. J Mol Biol. 1997;268:724–738. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Goldman BS, Kranz RG. ABC transporters associated with cytochrome c biogenesis. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Page MD, Pearce DA, Norris HA, Ferguson SJ. The Paracoccus denitrificans ccmA, B and C genes: cloning and sequencing, and analysis of the potential of their products to form a haem or apo- c-type cytochrome transporter. Microbiology. 1997;143(Pt 2):563–576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ahuja U, Thony-Meyer L. CcmD is involved in complex formation between CcmC and the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:236–243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Richard-Fogal CL, Frawley ER, Kranz RG. Topology and function of CcmD in cytochrome c maturation. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:3489–3493. doi: 10.1128/JB.00146-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Feissner RE, Richard-Fogal CL, Frawley ER, Kranz RG. ABC transporter-mediated release of a haem chaperone allows cytochrome c biogenesis. Molecular microbiology. 2006;61:219–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Christensen O, Harvat EM, Thony-Meyer L, Ferguson SJ, Stevens JM. Loss of ATP hydrolysis activity by CcmAB results in loss of c-type cytochrome synthesis and incomplete processing of CcmE. FEBS J. 2007;274:2322–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Arcus V. OB-fold domains: a snapshot of the evolution of sequence, structure and function. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:794–801. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Arnesano F, Banci L, Barker PD, Bertini I, Rosato A, Su XC, Viezzoli MS. Solution structure and characterization of the heme chaperone CcmE. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13587–13594. doi: 10.1021/bi026362w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Enggist E, Thony-Meyer L, Guntert P, Pervushin K. NMR structure of the heme chaperone CcmE reveals a novel functional motif. Structure. 2002;10:1551–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Aramini JM, Hamilton K, Rossi P, Ertekin A, Lee HW, Lemak A, Wang H, Xiao R, Acton TB, Everett JK, Montelione GT. Solution NMR structure, backbone dynamics, and heme-binding properties of a novel cytochrome c maturation protein CcmE from Desulfovibrio vulgaris. Biochemistry. 2012;51:3705–3707. doi: 10.1021/bi300457b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Schulz H, Hennecke H, Thony-Meyer L. Prototype of a heme chaperone essential for cytochrome c maturation. Science. 1998;281:1197–1200. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5380.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Lee D, Pervushin K, Bischof D, Braun M, Thony-Meyer L. Unusual heme-histidine bond in the active site of a chaperone. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3716–3717. doi: 10.1021/ja044658e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Harvat EM, Redfield C, Stevens JM, Ferguson SJ. Probing the Heme-Binding Site of the Cytochrome c Maturation Protein CcmE Biochemistry. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Enggist E, Schneider MJ, Schulz H, Thony-Meyer L. Biochemical and mutational characterization of the heme chaperone CcmE reveals a heme binding site. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:175–183. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.175-183.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Mavridou DA, Clark MN, Choulat C, Ferguson SJ, Stevens JM. Probing heme delivery processes in cytochrome c biogenesis system I. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7262–7270. doi: 10.1021/bi400398t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Throne-Holst M, Thony-Meyer L, Hederstedt L. Escherichia coli ccm in-frame deletion mutants can produce periplasmic cytochrome b but not cytochrome c. FEBS letters. 1997;410:351–355. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Ferguson SJ, Stevens JM, Allen JW, Robertson IB. Cytochrome c assembly: a tale of ever increasing variation and mystery? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:980–984. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Ren Q, Thony-Meyer L. Physical interaction of CcmC with heme and the heme chaperone CcmE during cytochrome c maturation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32591–32596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Frawley ER, Kranz RG. CcsBA is a cytochrome c synthetase that also functions in heme transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10201–10206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903132106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Uchida T, Stevens JM, Daltrop O, Harvat EM, Hong L, Ferguson SJ, Kitagawa T. The interaction of covalently bound heme with the cytochrome c maturation protein CcmE. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51981–51988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Mavridou DA, Stevens JM, Monkemeyer L, Daltrop O, di Gleria K, Kessler BM, Ferguson SJ, Allen JW. A pivotal heme-transfer reaction intermediate in cytochrome c biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2342–2352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Daltrop O, Stevens JM, Higham CW, Ferguson SJ. The CcmE protein of the c-type cytochrome biogenesis system: unusual in vitro heme incorporation into apo-CcmE and transfer from holo-CcmE to apocytochrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9703–9708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152120699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Verissimo AF, Mohtar MA, Daldal F. The heme chaperone ApoCcmE forms a ternary complex with CcmI and apocytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6272–6283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.440024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].San Francisco B, Kranz RG. Interaction of HoloccmE with CcmF in heme Trafficking and Cytochrome c Biosynthesis. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:570–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Faivre-Nitschke SE, Nazoa P, Gualberto JM, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G. Wheat mitochondria ccmB encodes the membrane domain of a putative ABC transporter involved in cytochrome c biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1519:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Spielewoy N, Schulz H, Grienenberger JM, Thony-Meyer L, Bonnard G. CCME, a nuclear-encoded heme-binding protein involved in cytochrome c maturation in plant mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5491–5497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Goddard AD, Stevens JM, Rao F, Mavridou DA, Chan W, Richardson DJ, Allen JW, Ferguson SJ. c-Type cytochrome biogenesis can occur via a natural Ccm system lacking CcmH, CcmG, and the heme-binding histidine of CcmE. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22882–22889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Bonnard G, Corvest V, Meyer EH, Hamel PP. Redox processes controlling the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1385–1401. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Hamel P, Corvest V, Giege P, Bonnard G. Biochemical requirements for the maturation of mitochondrial c-type cytochromes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Shouldice SR, Heras B, Walden PM, Totsika M, Schembri MA, Martin JL. Structure and function of DsbA, a key bacterial oxidative folding catalyst. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1729–1760. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Inaba K, Ito K. Structure and mechanisms of the DsbB-DsbA disulfide bond generation machine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:520–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Depuydt M, Messens J, Collet JF. How proteins form disulfide bonds. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:49–66. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Katzen F, Deshmukh M, Daldal F, Beckwith J. Evolutionary domain fusion expanded the substrate specificity of the transmembrane electron transporter DsbD. EMBO J. 2002;21:3960–3969. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Deshmukh M, Brasseur G, Daldal F. Novel Rhodobacter capsulatus genes required for the biogenesis of various c-type cytochromes. Molecular microbiology. 2000;35:123–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Stirnimann CU, Rozhkova A, Grauschopf U, Grutter MG, Glockshuber R, Capitani G. Structural basis and kinetics of DsbD-dependent cytochrome c maturation. Structure. 2005;13:985–993. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Fabianek RA, Hennecke H, Thony-Meyer L. Periplasmic protein thiol:disulfide oxidoreductases of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Stirnimann CU, Grutter MG, Glockshuber R, Capitani G. nDsbD: a redox interaction hub in the Escherichia coli periplasm. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1642–1648. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6055-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Stewart EJ, Katzen F, Beckwith J. Six conserved cysteines of the membrane protein DsbD are required for the transfer of electrons from the cytoplasm to the periplasm of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1999;18:5963–5971. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Han H, Wilson AC. The two CcdA proteins of Bacillus anthracis differentially affect virulence gene expression and sporulation. Journal of bacteriology. 2013;195:5242–5249. doi: 10.1128/JB.00917-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Crow A, Acheson RM, Le Brun NE, Oubrie A. Structural basis of Redox-coupled protein substrate selection by the cytochrome c biosynthesis protein ResA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23654–23660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Edeling MA, Guddat LW, Fabianek RA, Thony-Meyer L, Martin JL. Structure of CcmG/DsbE at 1.14 A resolution: high-fidelity reducing activity in an indiscriminately oxidizing environment. Structure. 2002;10:973–979. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Monika EM, Goldman BS, Beckman DL, Kranz RG. A thioreduction pathway tethered to the membrane for periplasmic cytochromes c biogenesis; in vitro and in vivo studies. J Mol Biol. 1997;271:679–692. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Turkarslan S, Sanders C, Ekici S, Daldal F. Compensatory thio-redox interactions between DsbA, CcdA and CcmG unveil the apocytochrome c holdase role of CcmG during cytochrome c maturation. Molecular microbiology. 2008;70:652–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Fabianek RA, Hennecke H, Thony-Meyer L. The active-site cysteines of the periplasmic thioredoxin-like protein CcmG of Escherichia coli are important but not essential for cytochrome c maturation in vivo. Journal of bacteriology. 1998;180:1947–1950. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1947-1950.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Bardischewsky F, Friedrich CG. Identification of ccdA in Paracoccus pantotrophus GB17: disruption of ccdA causes complete deficiency in c-type cytochromes. Journal of bacteriology. 2001;183:257–263. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.257-263.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Erlendsson LS, Hederstedt L. Mutations in the thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases BdbC and BdbD can suppress cytochrome c deficiency of CcdA-defective Bacillus subtilis cells. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:1423–1429. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1423-1429.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Sambongi Y, Ferguson SJ. Mutants of Escherichia coli lacking disulphide oxidoreductases DsbA and DsbB cannot synthesise an exogenous monohaem c-type cytochrome except in the presence of disulphide compounds. FEBS letters. 1996;398:265–268. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Deshmukh M, Turkarslan S, Astor D, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. The dithiol:disulfide oxidoreductases DsbA and DsbB of Rhodobacter capsulatus are not directly involved in cytochrome c biogenesis, but their inactivation restores the cytochrome c biogenesis defect of CcdA-null mutants. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185:3361–3372. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3361-3372.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Metheringham R, Griffiths L, Crooke H, Forsythe S, Cole J. An essential role for DsbA in cytochrome c synthesis and formate-dependent nitrite reduction by Escherichia coli K-12. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02529965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Mavridou DA, Ferguson SJ, Stevens JM. The interplay between the disulfide bond formation pathway and cytochrome c maturation in Escherichia coli. FEBS letters. 2012;586:1702–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Di Matteo A, Gianni S, Schinina ME, Giorgi A, Altieri F, Calosci N, Brunori M, Travaglini-Allocatelli C. A strategic protein in cytochrome c maturation: three-dimensional structure of CcmH and binding to apocytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27012–27019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Ahuja U, Rozhkova A, Glockshuber R, Thony-Meyer L, Einsle O. Helix swapping leads to dimerization of the N-terminal domain of the c-type cytochrome maturation protein CcmH from Escherichia coli. FEBS letters. 2008;582:2779–2786. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Zheng XM, Hong J, Li HY, Lin DH, Hu HY. Biochemical properties and catalytic domain structure of the CcmH protein from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:1394–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Meyer EH, Giege P, Gelhaye E, Rayapuram N, Ahuja U, Thony-Meyer L, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G. AtCCMH, an essential component of the c-type cytochrome maturation pathway in Arabidopsis mitochondria, interacts with apocytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16113–16118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503473102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Fabianek RA, Hofer T, Thony-Meyer L. Characterization of the Escherichia coli CcmH protein reveals new insights into the redox pathway required for cytochrome c maturation. Arch Microbiol. 1999;171:92–100. doi: 10.1007/s002030050683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Robertson IB, Stevens JM, Ferguson SJ. Dispensable residues in the active site of the cytochrome c biogenesis protein CcmH. FEBS letters. 2008;582:3067–3072. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Setterdahl AT, Goldman BS, Hirasawa M, Jacquot P, Smith AJ, Kranz RG, Knaff DB. Oxidation-reduction properties of disulfide-containing proteins of the Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome c biogenesis system. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10172–10176. doi: 10.1021/bi000663t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Reid E, Cole J, Eaves DJ. The Escherichia coli CcmG protein fulfils a specific role in cytochrome c assembly. Biochem J. 2001;355:51–58. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Schoepp-Cothenet B, Schutz M, Baymann F, Brugna M, Nitschke W, Myllykallio H, Schmidt C. The membrane-extrinsic domain of cytochrome b(558/566) from the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius performs pivoting movements with respect to the membrane surface. FEBS letters. 2001;487:372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Di Matteo A, Calosci N, Gianni S, Jemth P, Brunori M, Travaglini-Allocatelli C. Structural and functional characterization of CcmG from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key component of the bacterial cytochrome c maturation apparatus. Proteins. 2010;78:2213–2221. doi: 10.1002/prot.22733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Sanders C, Turkarslan S, Lee DW, Onder O, Kranz RG, Daldal F. The cytochrome c maturation components CcmF, CcmH, and CcmI form a membrane-integral multisubunit heme ligation complex. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29715–29722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805413200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Ren Q, Ahuja U, Thony-Meyer L. A bacterial cytochrome c heme lyase. CcmF forms a complex with the heme chaperone CcmE and CcmH but not with apocytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7657–7663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Rayapuram N, Hagenmuller J, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G, Giege P. The three mitochondrial encoded CcmF proteins form a complex that interacts with CCMH and c-type apocytochromes in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25200–25208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Giege P, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G. Cytochrome c biogenesis in mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2008;8:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Lang SE, Jenney FE, Jr., Daldal F. Rhodobacter capsulatus CycH: a bipartite gene product with pleiotropic effects on the biogenesis of structurally different c-type cytochromes. Journal of bacteriology. 1996;178:5279–5290. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5279-5290.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Sanders C, Boulay C, Daldal F. Membrane-spanning and periplasmic segments of CcmI have distinct functions during cytochrome c biogenesis in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189:789–800. doi: 10.1128/JB.01441-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Verissimo AF, Yang H, Wu X, Sanders C, Daldal F. CcmI subunit of CcmFHI heme ligation complex functions as an apocytochrome c chaperone during c-type cytochrome maturation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40452–40463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].D'Andrea LD, Regan L. TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Delgado MJ, Yeoman KH, Wu G, Vargas C, Davies AE, Poole RK, Johnston AW, Downie JA. Characterization of the cycHJKL genes involved in cytochrome c biogenesis and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Journal of bacteriology. 1995;177:4927–4934. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4927-4934.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Ritz D, Bott M, Hennecke H. Formation of several bacterial c-type cytochromes requires a novel membrane-anchored protein that faces the periplasm. Molecular microbiology. 1993;9:729–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Cinege G, Kereszt A, Kertesz S, Balogh G, Dusha I. The roles of different regions of the CycH protein in c-type cytochrome biogenesis in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;271:171–179. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Sanders C, Deshmukh M, Astor D, Kranz RG, Daldal F. Overproduction of CcmG and CcmFH(Rc) fully suppresses the c-type cytochrome biogenesis defect of Rhodobacter capsulatus CcmI-null mutants. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187:4245–4256. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.12.4245-4256.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Deshmukh M, May M, Zhang Y, Gabbert KK, Karberg KA, Kranz RG, Daldal F. Overexpression of ccl1-2 can bypass the need for the putative apocytochrome chaperone CycH during the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes. Molecular microbiology. 2002;46:1069–1080. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].San Francisco B, Bretsnyder EC, Rodgers KR, Kranz RG. Heme ligand identification and redox properties of the cytochrome c synthetase, CcmF. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10974–10985. doi: 10.1021/bi201508t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Di Silvio E, Di Matteo A, Malatesta F, Travaglini-Allocatelli C. Recognition and binding of apocytochrome c to P. aeruginosa CcmI, a component of cytochrome c maturation machinery. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Han D, Kim K, Oh J, Park J, Kim Y. TPR domain of NrfG mediates complex formation between heme lyase and formate-dependent nitrite reductase in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Proteins. 2008;70:900–914. doi: 10.1002/prot.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Thony-Meyer L. Biogenesis of respiratory cytochromes in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:337–376. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.337-376.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Ramseier TM, Winteler HV, Hennecke H. Discovery and sequence analysis of bacterial genes involved in the biogenesis of c-type cytochromes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7793–7803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Beckman DL, Trawick DR, Kranz RG. Bacterial cytochromes c biogenesis. Genes Dev. 1992;6:268–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Unseld M, Marienfeld JR, Brandt P, Brennicke A. The mitochondrial genome of Arabidopsis thaliana contains 57 genes in 366,924 nucleotides. Nat Genet. 1997;15:57–61. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Krause F. Detection and analysis of protein-protein interactions in organellar and prokaryotic proteomes by native gel electrophoresis: (Membrane) protein complexes and supercomplexes. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2759–2781. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Giege P, Rayapuram N, Meyer EH, Grienenberger JM, Bonnard G. CcmF(C) involved in cytochrome c maturation is present in a large sized complex in wheat mitochondria. FEBS letters. 2004;563:165–169. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Ahuja U, Thony-Meyer L. Dynamic features of a heme delivery system for cytochrome c maturation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52061–52070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Zickermann V, Angerer H, Ding MG, Nubel E, Brandt U. Small single transmembrane domain (STMD) proteins organize the hydrophobic subunits of large membrane protein complexes. FEBS letters. 2010;584:2516–2525. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]