Abstract

Background

Alcohol abuse is associated with cellular and biochemical disturbances that impact upon protein and nucleic acid synthesis, brain development, function and behavioral responses. To further characterize the genetic influences in alcoholism and the effects of alcohol consumption on gene expression, we used a highly sensitive exon microarray to examine mRNA expression in human frontal cortex of alcoholics and control males.

Methods

Messenger RNA was isolated from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC, Brodmann area 9) of 7 adult Alcoholic (6 males, 1 female, mean age 48 years) and 7 matched controls. Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array was performed according to standard procedures and the results analyzed at the gene level. Microarray findings were validated using qRT-PCR, and the ontology of disturbed genes characterized using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA).

Results

Decreased mRNA expression was observed for genes involved in cellular adhesion (e.g., CTNNA3, ITGA2), transport (e.g., TF, ABCA8), nervous system development (e.g., LRP2, UGT8, GLDN) and signaling (e.g., RASGRP, LGR5) with influence over lipid and myelin synthesis (e.g., ASPA, ENPP2, KLK6). IPA identified disturbances in network functions associated with neurological disease, and development including cellular assembly and organization impacting on psychological disorders.

Conclusions

Our data in alcoholism support a reduction in expression of dlPFC mRNA for genes involved with neuronal growth, differentiation and signaling that targets white matter of the brain.

Keywords: Affymetrix, Exon Microarray, Alcoholism, Frontal Cortex, Myelin

Introduction

Alcoholism is a chronic, severe relapsing disorder with global impact on individuals and society contributing to significant illness, injury and death worldwide each year (World Health Organization, 2010; Schuckit, 2009a). The compulsive use of alcohol and other substances arises from genetic, neurobiological and developmental, environmental and psychosocial influences that direct both the likelihood (and level) of alcohol exposure as well as biologic response (Knop et al., 2003; Manzardo et al., 2005; 2006; 2011; Spanagel, 2009; Schuckit, 2009b; Yan et al., 2013). Genetic factors are particularly important and contribute an estimated 40% to 60% of the risk of developing alcoholism (Goodwin et al., 1974; Prescott and Kendler, 1999; Schuckit, 2009b; Yan et al., 2013). Additionally, prolonged alcohol exposure can cause significant damage and measurable distortions in brain structure with associated cognitive dysfunction observed in the clinical setting (Harper, 2009; Harper and Matsumoto, 2008; Mukherjee, 2013; Müller-Oehring et al., 2013; Pfefferbaum et al., 2009). Alcohol-related genetic and molecular changes precipitate the development of tolerance, physiological dependence, craving, psychiatric, and other behavioral changes that may propagate abuse behavior (Contet, 2012; Hashimoto et al., 2011; Mukherjee, 2013; Müller-Oehring et al., 2013). The identification of genes and proteins associated with predisposition, development and maintenance of alcoholism is an important area of intense research to facilitate effective treatments including pharmacotherapy and small molecule discovery.

Brain regions of primary interest in the etiology of addictions encompass components and projections of the mesolimbic dopamine circuitry including the ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, amygdala and prefrontal cortex (PFC) which mediate brain reward responses to endogenously and exogenously derived substrates (Mayfield et al., 2002; 2008; Mukherjee, 2013; Müller-Oehring et al., 2013; Ross and Peselow, 2009). Disturbances in the mesolimbic dopamine circuitry in response to exposure to addictive substances are widely reported in human and animal literature (Koob, 2003; Koob and Le Moal, 2001; Müller-Oehring et al., 2013; Ross and Peselow, 2009). The PFC is believed to play a part in the development and expression of alcoholism through its role in guiding executive functions impacting judgment and decision-making. Neuronal loss of PFC grey and white matter in addition to region selective disturbances in gene, non-coding RNA and protein expression has been reported in post mortem brain samples taken from alcoholics (Alexander-Kaufman et al., 2007; Contet, 2012; Mayfield, 2002). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) which includes Brodmann Area 9 has reciprocal connections to many cortical regions and is known to play a role in the regulation of motivated behaviors. It has been identified as a brain region particularly susceptible to the effects of long-term alcohol abuse associated with significant volume loss in alcoholics - particularly of white matter tissue (Alexander-Kaufman et al., 2007). Structural abnormalities and dlPFC dysfunction is associated with impulse deregulation and cognitive dysfunction, substance abuse including alcoholism and may contribute to pathology.

High throughput microarray technology has been used to examine gene expression in human brain of alcoholics relative to controls (Flatscher-Bader et al., 2005; 2006; 2010; Lewohl et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2004; 2006; Mayfield et al., 2002; Sokolov et al., 2003). These studies show remarkable concordance in alcohol responsive gene disturbances in the PFC which impact upon cellular functioning including myelination, cellular signaling and energy production with an overrepresentation of down-regulated vs up-regulated genes exhibited at the mRNA level (Lewohl et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2004, 2006; Mayfield et al., 2002; Sokolov et al., 2003). Comparative studies of gene expression in the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area have reported disturbances in genes associated with vesicle formation and regulation of cellular architecture, including pathways regulating the actin cytoskeleton, possibly impacting upon neuroplasticity and influenced by tobacco use (Flatscher-Bader et al., 2005; 2006; 2010). Liu et al. (2006) found significant down-regulation of astrocyte specific genes in the superior frontal cortex as well as genes associated with cellular adhesion and protein trafficking (Liu et al., 2006). These differences were exaggerated among alcoholics complicated with cirrhotic liver disease (Liu et al., 2007).

Microarray technology and computational capabilities have continued to increase in the years following these early studies. High resolution mapping using >2 million probe sets is now possible at the whole genome mRNA and exon level. Additionally, advancements in computational programs with genes linked by accession numbers (e.g., Ingenuity Pathway Analysis) have elevated the capabilities and sophistication of mapping of disturbed gene networks. We present an examination of dlPFC gene expression patterns and functional analysis of human alcoholics and controls using a highly sensitive exon microarray platform.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Messenger RNA (exon) expression profiles were obtained from total RNA isolated using the Qiagen (Qiagen Inc, Maryland) kit from post-mortem human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC, Brodmann area 9) of 7 Alcoholics [6 males, 1 female; mean (±SD) age = 49.0 (±6.7) yrs, range 41–57 yrs] and 7 age-matched control subjects [5 males, 2 female; mean (±SD) age = 49.4 (±7.1) yrs, range 37–56 yrs] characterized in Table 1. The average RNA integrity number (RIN) was 6 for the alcoholics and 5 for the controls and considered adequate for microarray analysis. The gender composition of the sample reflects the sex ratio distribution found in the general population of alcoholics. Whole genome DNA methylation and miRNA expression for these samples have been previously reported (Manzardo et al., 2012, 2013). Samples were procured from the New South Wales Brain Bank (NSWBB, Sydney, Australia) and collected according to a standardized protocol (Sheedy et al., 2008) in compliance with ethical guidelines established by the Sydney South West Area Health Service Human Ethics Committee (X03-0074). Informed written consent was obtained from the nearest living relative. The mean (±SD) post-mortem interval (PMI) for our subjects shown in Table 1 was 27.5 (±10.3) hours with a range of 13 to 43 hours. The mean (±SD) sample pH was 6.6 (±0.22). All samples tested were negative for viral hepatitis and for the human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Alcoholic and Control Subjects

| ID | Age (yrs) | Sex | Group | Abuse (yrs) | Smoking Status | Liver Pathology | Cause of Death | PMI | pH | RIN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| 201 | 46 | Male | Dependent | >10 | Unknown | Cirrhosis | Alcohol Toxicity | 24 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| 259 | 56 | Male | Abuse | 20 | Unknown | Steatosis | Ischaemic Heart Disease; Emphysema | 15 | 6.7 | 5.0 |

| 430 | 43 | Male | Abuse | 20 | Ex smoker | Steatosis | Sepsis | 29 | 6.3 | 6.6 |

| 466 | 57 | Male | Dependent | 10 | Current | Cirrhosis | Ischaemic Heart Disease | 43 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| 586 | 55 | Male | Dependent | 30 | Non smoker | Steatosis | Asphyxia | 17 | 6.8 | 4.4 |

| 628 | 41 | Male | Abuse | 20 | Current | Steatosis | Alcohol/Methadone Toxicity | 38 | 6.5 | 6.7 |

| 596 | 45 | Female | Dependent | 10 | Current | Cirrhosis | Coronary Atherosclerosis | 41 | 6.8 | 6.4 |

| 225 | 56 | Male | Control | 0 | Current | Steatosis | Coronary Artery Atheroma | 24 | 6.5 | 6.4 |

| 236 | 43 | Male | Control | 0 | Current | Normal | Thrombotic Coronary Artery Occlusion | 13 | 6.4 | 6.5 |

| 239 | 37 | Male | Control | 0 | Unknown | Steatosis | Electrocution | 24 | 6.4 | 6.3 |

| 339 | 56 | Male | Control | 0 | Current | Normal | Cardiomegaly | 37 | 6.8 | 4.0 |

| 636 | 54 | Male | Control | 0 | Ex smoker | Normal | Coronary Artery Disease | 28 | 6.4 | 4.0 |

| 460 | 49 | Female | Control | 0 | Non smoker | Normal | Arrhytmogenic Right Venticular Dysplasia | 15 | 6.9 | 4.0 |

| 551 | 51 | Female | Control | 0 | Non smoker | Steatosis | Myocardial Infarction | 37 | 6.9 | 5.8 |

ID= subject identifier from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre; PMI=post mortem interval; RIN=RNA integrity number

All subjects were of European descent and alcoholic subjects met the criteria described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition and National Health and Medical Research Council/World Health Organization criteria. Control subjects were social drinkers (non-abstainers for alcohol use) and did not meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence. The average estimated duration of alcohol dependence for case subjects was 19.5 (±8.1) years (range 10–30 years). All Alcoholic subjects were diagnosed with hepatic complications of steatosis or cirrhosis while controls showed normal liver function to moderate steatosis. The individual causes of death varied across participants with the most common causes due to cardiovascular and respiratory problems or infection. Direct alcohol toxicity or overdose was indicated in two deaths of alcoholic subjects. Family history of alcohol problems was either negative or unknown for all subjects. Previous reports examining gene expression profiles in the frontal cortex reported by Liu et al. in 2004, 2006 and Flatscher-Bader et al. in 2005 with brain tissue procured from the NSWBB utilized a different collection of alcoholic and non-alcoholic individuals which is evident by comparison of age, sex and PMI data.

Microarray

The Human Exon 1.0 ST (sense target) Array (Affymetrix, Inc.; Santa Clara, CA) was used to examine dlPFC mRNA expression differences between alcoholics and control subjects. Array specifications include: Array Type- Human Exon 1.0 ST; Source - cDNA-based content including the more established human RefSeq mRNAs, GenBank® mRNAs, and ESTs from dbEST. Additional annotations were created by mapping syntenic cDNAs to the human, mouse, and rat genomes using genome synteny maps from the UCSC Genome Bioinformatics group. Predicted gene structure sequences from GENSCAN; Ensembl; Vega; geneid and sgp; TWINSCAN; Exoniphy; microRNA Registry; MITOMAP; and structural RNA predictions; Build- all probe locations used the human genome reference GRCh36/hg19 assembly (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway?db=hg19). Probe Length- 25mer or greater. The Human Exon 1.0 ST Array uses 1.4 million probe sets to interrogate exons at 28,869 well-annotated genes.

qRT-PCR Methodology

Three representative genes (UGT8, TF, LRP2) identified by Exon microarray as differentially expressed in alcoholism were evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qPCR). First strand cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng of total mRNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). Primers for the genes of interest including the reference gene, GAPDH were purchased from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany). Primers spanning exon-exon junctions were selected to avoid potential genomic DNA contamination. SYBR green PCR assays were performed in 48-well white plates on a MJ Mini Personal Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA). The reaction cycling parameters for each of the PCR reaction were 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 1 min. Expression levels of UGT8, TF, and LRP2 were normalized to GAPDH. Fold induction values were calculated using ΔΔCt method according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Data Analysis

Exon Array Analysis

Gene expression profiling was carried out using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Exon 1.0 ST Array consisting of 1.4 million probe-sets, of which around 300,000 are core exon probe-sets supported by putative full-length mRNA (RefSeq and full-length GenBank annotated alignments). These core probe-sets map to approximately 18,000 genes with high confidence. Gene expression level was determined by averaging the intensity signals of multiple probes to the individual exons per gene. The exon-arrays are RMA-background corrected, quantile-normalized and gene-level summarized using the Median Polish algorithm (Irizarry et al., 2003). The resulting log (base 2) transformed signal intensities (expression values) were used to ascertain differentially expressed genes. Fold change statistics for individual genes were calculated by taking the linear contrast between the least square means of the (log) alcoholic and (log) control groups and back transforming the result to a linear scale (this is the ratio of the geometric mean of the treatment samples to the geometric mean of the control samples). Corresponding significance scores (p-values) were assigned based on the t-statistic of the linear contrast. A statistical model including eight potential confounding factors (age, gender, alcoholism diagnosis, duration of alcohol abuse, hepatic illness, PMI, tissue pH and sample RIN) was carried out for genes with ≥3 fold change difference in alcoholics. No significant factors were identified and thus the factors were excluded from the final model.

Our analysis was conducted on brain tissues obtained from biological replicates of seven alcoholic and seven control samples and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was performed on genes showing a fold change of ±1.5, p-value ≤ 0.05 and false discovery rate of ≤ 0.2. Messenger RNAs from genes showing a fold change of ±2.0, p-value ≤ 0.05 and false discovery rate of ≤ 0.2 were hierarchically clustered and visualized in a heat map (Figure 1). Direct and indirect relationships were examined including endogenous chemicals.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of mRNAs clustered and based upon significant disturbances in the frontal cortex of alcoholics and control subjects (red or dark gray represents increased expression and green or light gray represents decreased expression).

Results

Exon (Gene) Expression

Exon and gene expression analysis of mRNAs taken from brain specimens of alcohol dependent and control subjects showed less than or equal to −1.5 fold down-regulation of 280 exons corresponding with 248 genes recognized by IPA and greater than or equal to 1.5 fold up-regulation of 70 exons from 56 IPA recognized genes. Consistent with previous reports of gene disturbances in the frontal cortex in alcoholism, significant down-regulation (>1.5 fold) in gene expression was observed for CLDN11, ENPP2, PMP22, MOG, MAG, MBP, NPY, TF, and UGT8 (Lui et al., 2004, 2006; Mayfield et al., 2002). Table 2 provides a list of selected genes with ≥ 3 fold down-regulation in alcoholism relative to control subjects (p-value< 0.05, FDR < 0.2) which held the greatest confidence and will be the focus of this report. Down-regulated genes had functional roles in cellular adhesion (e.g., CTNNA3, ITGA2), signaling (e.g., RASGRP, LGR5) and nervous system development (e.g., LRP2, UGT8, GLDN). Expression of genes associated with cellular and transmembrane transport of ions and minerals (e.g., TF, SLC5A11, ABCA8) were also reduced. Genes associated with lipid metabolism and myelin synthesis (e.g., LRP2, ASPA, ENPP2, KLK6) appeared to be specifically effected.

Table 2.

Expression of Genes Down-regulated in Alcoholism

| Gene | Fold Change | Biological Function | Chromosome Band |

|---|---|---|---|

| LRP2 | −4.0 | Lipid/vitamin/steroid metabolism, cellular proliferation, and forebrain development | 2q24-q31 |

| FAM38B* | −3.9 | Membrane protein with unknown function | 18p11.22 |

| ASPA | −3.9 | Aspartate catabolism contributing acetyl groups for the synthesis of lipids and myelin. | 17p13.3 |

| TF ‡ * | −3.9 | Iron transport/homeostasis, required for cell division | 3q22.1 |

| EVI2A | −3.7 | Transmembrane receptor | 17q11.2 |

| UGT8 ‡ | −3.7 | Hexosyl transfer, central and peripheral nervous system development | 4q26 |

| ST18 | −3.6 | Regulation of DNA-dependent transcription, inhibition of RNA polymerase II promoter | 8q11.23 |

| ANLN | −3.5 | Cytokinesis, mitosis | 7p15-p14 |

| SLC5A11 | −3.4 | Transmembrane ion transport: sodium, carbohydrate | 16pter-p11 |

| ENPP2 ‡ | −3.4 | Lipid catabolism, chemotaxis, regulation of cellular migration | 8q24.1 |

| CTNNA3 | −3.3 | Cell-cell adhesion | 10q22.2 |

| ABCA8 | −3.3 | Transmembrane transport | 17q24 |

| GLDN | −3.2 | Cell differentiation, nervous system development | 15q21.2 |

| C21orf91 | −3.1 | Unknown | 21q21.1 |

| RASGRP | −3.1 | Intracellular signaling, MAPKKK cascade, Ras protein signal transduction | 2p25.1-p24.1 |

| ITGA2 | −3.1 | Cellular adhesion and migration, integrin-mediated signaling, cellular response mechanism | 5q11.2 |

| KLK6 | −3.1 | Cellular response, regulation of cellular differentiation in CNS development, myelination, protein processing (e.g., amyloid precursor protein) | 19q13.3 |

| TMEM63A | −3.0 | Membrane protein with nucleotide binding and unknown function | 1q42.12 |

| SPP1 | −3.0 | Tissue development, osteoblast differentiation, cellular response to vitamin, hormone or injury, TGF-β signaling | 4q22.1 |

| LGR5 | −3.0 | G-protein receptor coupled signaling | 12q22-q23 |

Exon-arrays were RMA-background corrected, quantile-normalized and gene-level summarized using the Median Polish algorithm followed by linear regression. Results are presented for genes with exons down-regulated ≥ 3 fold, p-value < 0.01; FDR cutoff < 0.2.

Two exons for the indicated genes were down-regulated ≥ 3 fold.

previously reported to be down-regulated in the frontal cortex by Mayfield et al., 2002; or Liu et al., 2004 or 2006.

We observed fewer up-regulated than down-regulated genes which were disturbed to a lesser degree (Figure 1). In agreement with previous reports of gene expression disturbances in the frontal cortex in alcoholism, a significant up-regulation (>1.5 fold) in gene expression was observed for GABRG1, MT1L, SLC1A3 and TGFβ1 (Flatscher-Bader et al., 2005; 2008; Mayfield et al., 2002). Table 3 provides a list of selected genes with ≥ 3 fold up-regulation in alcoholism relative to control subjects (p-value< 0.05, FDR < 0.2) which held the greatest confidence and will be the focus of this report. A significantly up-regulated gene in our study with a previously unreported association with alcoholism includes an important lipid-binding protein, WIF1, which binds to and inhibits WNT signaling, a controlling pathway in embryonic development (Hsieh et al., 1999). Other up-regulated and novel genes had functional roles in intracellular transport, metabolism and detoxification (RANBP3L, MT1G, GJB6, AGX2L1).

Table 3.

Expression of Genes Up-regulated in Alcoholism

| Gene | Fold Change | Biological/Molecular Function | Chromosome Band |

|---|---|---|---|

| WIF1 | 2.5 | Lipid protein that binds and inhibits WNT signaling | 12q14.3 |

| RANBP3L | 2.3 | Intracellular transport | 5p13.2 |

| MT1G | 2.2 | Metal ion binding, storage, transport and detoxification | 16q13 |

| GJB6 | 2.0 | Proliferation, cellular signaling and apoptosis | 13q11-q12.1 |

| AGX2L1 | 2.0 | Pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent metabolism of phosphoethanolamineto ammonia, inorganic phosphate and acetaldehyde | 4q25 |

Exon-arrays were RMA-background corrected, quantile-normalized and gene-level summarized using the Median Polish algorithm followed by linear regression. Results presented for fold changes ≥ 2.0 with a p-value < 0.01 and FDR step-up < 0.15

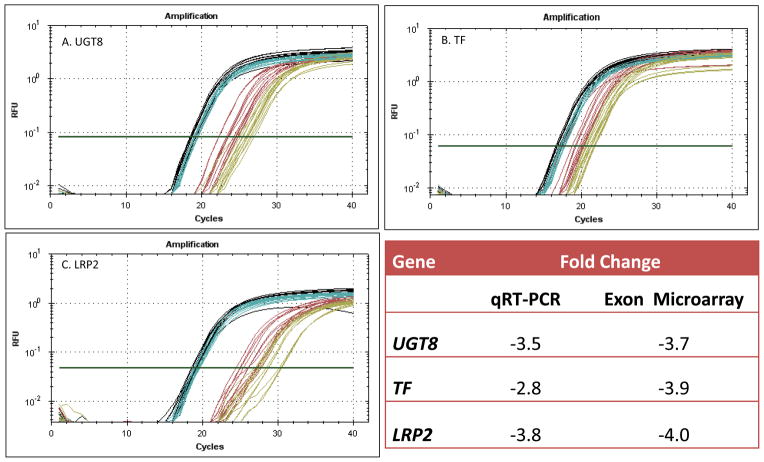

The Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST Array possesses a high level of resolution and internal validity; for example, expression level analysis of the LRP2 gene was based upon the average intensity reading of 87 separate probes of LRP2 exons. The number obviously varies by gene (e.g., WIF1 contained 12 probes), but remains much more robust than earlier microarrays with one probe per gene requiring external validation (i.e., qRT-PCR). However, three representative genes down-regulated in our study: UGT, TF and LRP2 were also selected for further confirmation using qRT-PCR (Figure 2). The results showed a 3 to 4 fold down regulation of all three genes in alcoholism relative to GAPDH (a housekeeping gene) which was not disturbed in our exon microarray analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

qRT-PCR amplification of brain mRNA of selected disturbed genes in alcoholism relative to control gene (GAPDH) expression for A. UDP glycosyltransferase 8 (UGT8) B. Transferrin (TF) and C. Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2 (LRP2).

GAPDH: Black= control subjects (N=7), Blue= alcohol dependent subjects (N=7);

Selected disturbed genes: Red= control subjects (N=7), Yellow= alcohol dependent subjects (N=7)

Ingenuity Pathway Anaylsis

The functional ontology of impacted genes characterized using IPA identified the top Biological Function Disturbances as those pertaining to Neurological Disease and Nervous System Development and Function networks (Table 4a). Annotated functions assigned to these networks impact upon myelination and glial integrity and have been associated with Schizophrenia. Correlational analysis considering activation state of disturbed genes identified a significant suppression of biological functions related to cellular morphology, function, maintenance, organization and assembly impacting upon neuronal outgrowth and cytoskeletal integrity (Table 4b). Top Canonical Pathways identified by IPA showed a significant disturbance in several Rho signaling pathways which also impact upon cytoskeletal integrity (Table 4c). Consistent with previous reports in liver, a significant up-regulation of actin mRNA was observed in alcoholism (Boujedidi et al., 2012); however, the precise molecular composition of actin (e.g., globular, filament, polymer) cannot be determined based upon an exon array. Thus, the nature of the disturbance and its impact upon cytoskeletal integrity and dendritic spine formation is unclear from these data. In addition to these changes, IPA also identified an underlying structure for toxology function disturbances pertaining to cardiac, renal and hepatic systems and nutritional deficiencies commonly associated with severe alcoholism but not the focus of this manuscript.

Table 4.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis Summary

| a. Top Biological Function Disturbances (independent of gene expression direction p-values ≤ 1.0 E −04)

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | Functions Annotation | p-value |

| Nervous System Development and Function | Morphology of neuroglia | 6.1 E -05 |

| Myelination of cells | 1.2 E -04 | |

| Morphology of the nervous system | 2.3 E -04 | |

|

| ||

| Neurological Disease | Demyelination of nervous tissue | 1.0 E -05 |

| Schizophrenia | 2.3 E -04 | |

| b. Top Biological Function Disturbances with Correlated Activation States (z-scores ≤ −3.0)

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Functions Annotation | p-value | Activation z-score |

| Cellular Morphology | Formation of cellular protrusions | 0.014 | −3.5 |

|

| |||

| Cellular Function and Maintenance; Cellular Organization and Assembly (overlapping pathways) | Formation of cellular protrusions | 0.014 | −3.5 |

| Microtubule dynamics | 0.019 | −3.5 | |

| Organization of cytoskeleton | 0.0024 | −3.0 | |

| Organization of cytoplasm | 0.0075 | −3.0 | |

| c. Top Canonical Pathway Disturbances

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | p-value | Ratio (disturbed/total) |

| Signaling by Rho Family GTPases | 4.4 E -07 | 18/254 |

| Rho A Signaling | 1.3 E -05 | 11/120 |

| Rho GSI Signaling | 5.3 E -04 | 11/199 |

Discussion

Our results are consistent with previous reports citing disturbances in mRNA expression in the PFC emphasizing the down-regulation of neurodevelopmental mediators in alcoholism. Messenger RNAs from the medial frontal cortex of alcoholics showing significant down-regulation relative to age and gender-matched non-alcoholic controls had functional roles in cellular adhesion (e.g., CTNNA3, ITGA2), transport (e.g., TF, ABCA8), nervous system development (e.g., LRP2, UGT8, GLDN) and signaling (e.g., RASGRP, LGR5) with targeted effects on lipid and myelin synthesis (e.g., ASPA, ENPP2, KLK6). Gene expression disturbances for several of these genes [e.g., TF, ENPP2, UGT8) have been reported in previous studies of frontal cortex in alcoholism (Liu et al, 2004; 2006; Mayfield et al., 2002). IPA analysis identified disturbances in biological functions impacting upon neurological disease, nervous system development and function through the down-regulation of genes associated with neuronal architecture and outgrowth. Functionally disturbed genes did not overlap with any specific susceptibility genes linked to the development of alcoholism or related phenotypes but several paralogs derived from similar functional classes (e.g., cadheren, thrombospondin, semaphorin and solute carrier proteins) were identified (Rietschel and Treutlein, 2013). Many disturbed genes were drawn from gene networks (e.g., cation transport, synaptic transmission and transmission of nerve impulses) believe to impart risk for alcohol dependence (Hans et al., 2013). Some of the gene disturbances that we present are likely to reflect the pathologic processes of chronic alcohol use and multi-organ involvement (e.g., inflammation, hematopoiesis and hepatic dysfunction and metabolism) impacting brain function and architecture (e.g., oligodendrocyte production, cell number, adhesion and differentiation, myelination and actin formation). The specific impact of these disturbances on the propagation of abuse behavior itself remains to be elucidated.

The number of down-regulated exons (genes) identified in our sample surpassed the number up-regulated and appear to differentially impact upon brain white matter development. IPA identified a functional impairment in biological markers associated with nervous system development and function which is reflected in the down-regulation of several important developmental mediators (ANLN, ENPP2, ITGA2, TF)(Baumann and Pham-Dihn, 2001; Dugas et al., 2006). ENPP2 is a phosphodiesterase and phospholipase involved in the production of the growth enhancer, lysophosphatidic acid, which stimulates cellular proliferation and chemotaxis (Tokumura et al., 2002). ITGA2 plays a role in cell attachment and neurite outgrowth (Inoue et al., 2003). TF, required for iron homeostatis and commonly disturbed in alcoholism, is also known to impact cellular division (Baumann and Pham-Dihn, 2001; Dugas et al., 2006). Lipid biochemistry and myelin formation are specifically impacted by UGT8 which is involved in the biosynthesis of galactocerebrosides, abundant sphingolipids of the myelin membrane of the central and peripheral nervous systems, and GLDN important for formation of the nodes of Ranvier in myelinating cells (Eshed et al., 2005; Mackenzie et al., 2005). These data are consistent with previous studies of frontal cortex gene expression in alcoholism which have reported disturbances in developmental mediators (e.g., UGT8, ENPP2, CLDN) and myelination (e.g., MOG, MAG, MBP and PMP22) (Flatscher-Bader et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2004, 2006; Mayfield et al., 2002). Flatscher-Bader and Wilce (2006) also used real-time polymerase chain reaction and microarray analysis to identify disturbances in selected genes EAAT-1, MDK, TIMP3 and WASF1 in the prefrontal cortex in alcoholism which were not found to be disturbed in our study.

Biological functions related to neurological disease were also identified as disturbed by IPA. The most significant disturbance that was novel to our study and confirmed by qRT-PCR is the suppression of LRP2 (megalin) a member of the low density lipoprotein receptor family of importance in brain development that mediates the endocytotic uptake of vitamin D and steroids (Nykjer et al., 1999). Genetic deletion of megalin is associated with Donnai-Barrow syndrome which is characterized by corpus callosum abnormalities, myopia, and sensorineural deafness (Kantarci et al., 2009). The observed suppression of ASPA function is also novel and notable for its influence over lipid synthesis in myelinization as well as the association between ASPA gene deletion and white matter degeneration in Canavan disease (Kumar et al., 2006).

The suppression of white matter formation coincides with disturbances in signaling pathways influencing cytoskeletal integrity and neuronal outgrowth including actin formation and is associated with an accumulation of actin mRNA in alcoholism. Disruption of neuronal architecture of multiple brain regions are widely reported in alcoholism and is consistent with the present findings in the dlPFC. Further, Flatscher-Bader et al. (2010) have previously reported gene disturbances in FN1, RHOA, RHOB SPARC, and ITGAV of the Rho-mediated signaling cascade in the nucleus accumbens impacting upon regulation of actin cytoskeleton associated with alcohol and tobacco co-abuse. A high frequency of tobacco use was also noted in our samples and the Rho-mediated signaling cascade was disturbed. However, our findings in the frontal cortex did not consistently overlap at the gene level with findings reported for the nucleus accumbens. Gene mutations impacting actin polymerization are associated with several heritable disorders with associated intellectual impairment (e.g., Williams, fragile X, fetal alcohol, and Patau syndromes) and characterized by reduced dendritic arborization and underdeveloped spine structure similar to that observed in alcoholism.

The findings in the present investigation are impacted by the complexity and co-morbidities in the study samples including co-morbid tobacco use. Hepatic diseases including cirrhosis identified in alcohol dependent subjects are known to influence gene expression (Etheridge et al., 2011; Matsumoto, 2009; Liu et al., 2007). Metabolic activities of hepatic enzymes have been shown to protect against alcohol mediated brain damage and compromised hepatic function may have significantly enhanced brain injury (Matsumoto, 2009; Liu et al., 2007). The expression of housekeeping genes such as GAPDH and actin are influenced by hepatic disease which can interfere with qRT-PCR validation (Boujedidi et al., 2012). Examination of both exon microarray and qRT-PCR results showed no evidence of a disturbance in GAPDH expression but as reported actin mRNA was significantly elevated. Although tissues samples for several prior studies were obtained from the same brain bank, the individual alcoholics and control subjects were different and provide additional support for replicative findings.

The present study results are consistent with previous reports of disturbances in mRNA expression in the PFC emphasizing the down-regulation of neurodevelopmental mediators in alcoholism (e.g., TF, ENPP2, and UGT8). Biological functions impacting upon neurological disease, nervous system development and function were disturbed and genes associated with neuronal architecture and outgrowth were down-regulated. Several novel gene disturbances were found including decreased expression for LRP2, CTNNA3, GLDN and ITGA2 as well as increased expression for WIF1 and MT1G in alcoholism which may influence neurological development, functioning and behavior. The results of the present study further characterize alcoholism-related functional abnormalities influencing dlPFC activity and will aide in the development of targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

Tissues were received from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre at the University of Sydney which is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Schizophrenia Research Institute and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIH (NIAAA) R24AA012725]. This investigation was supported by a grant from the Hubert & Richard Hanlon Trust and NICHD HD 02528. The authors of this study have no competing financial interests pertaining to this work.

References

- Alexander-Kaufman K, Cordwell S, Harper C, Matsumoto I. A proteome analysis of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in human alcoholic patients. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1(1):62–72. doi: 10.1002/prca.200600417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann N, Pham-Dinh D. Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):871–927. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujedidi H, Bouchet-Delbos L, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Njiké-Nakseu M, Maitre S, Prévot S, Dagher I, Agostini H, Voican CS, Emilie D, Perlemuter G, Naveau S. Housekeeping gene variability in the liver of alcoholic patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(2):258–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contet C. Gene expression under the influence: transcriptional profiling of ethanol in the brain. Curr Psychopharmacol. 2012;1(4):301–314. doi: 10.2174/2211556011201040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas JC, Tai YC, Speed TP, Ngai J, Barres BA. Functional genomic analysis of oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(43):10967–10983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2572-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y, Feinberg K, Poliak S, Sabanay H, Sarig-Nadir O, Spiegel I, Bermingham JR, Jr, Peles E. Gliomedin mediates Schwann cell-axon interaction and the molecular assembly of the nodes of Ranvier. Neuron. 2005;47(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge N, Mayfield RD, Harris RA, Dodd PR. Identifying changes in the synaptic proteome of cirrhotic alcoholic superior frontal gyrus. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(1):122–128. doi: 10.2174/157015911795017164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatscher-Bader T, van der Brug M, Hwang JW, Gochee PA, Matsumoto I, Niwa S, Wilce PA. Alcohol-responsive genes in the frontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of human alcoholics. J Neurochem. 2005;93:359–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatscher-Bader T, van der Brug MP, Landis N, Hwang JW, Harrison E, Wilce PA. Comparative gene expression in brain regions of human alcoholics. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5(Suppl 1):78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatscher-Bader T, Wilce PA. Chronic smoking and alcoholism changes expression of selective genes in the human prefrontal cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(5):908–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatscher-Bader T, Zuvela N, Landis N, Wilce PA. Smoking and alcoholism target genes associated with plasticity and glutamate transmission in the human ventral tegmental area. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(1):38–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatscher-Bader T, Harrison E, Matsumoto I, Wilce PA. Genes associated with alcohol abuse and tobacco smoking in the human nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(7):1291–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin DW, Schulsinger F, Moller N, Hermansen L, Winokur G, Guze SB. Drinking problems in adopted and nonadopted sons of alcoholics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;31:164–169. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760140022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Yang BZ, Kranzler HR, Liu X, Zhao H, Farrer LA, Boerwinkle E, Potash JB, Gelernter J. Integrating GWAS and human protein interaction networks identifies a gene subnetwork underlying alcohol dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(6):1027–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C. The neuropathology of alcohol-related brain damage. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(2):136–140. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C, Matsumoto I. Ethanol and brain damage. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto JG, Forquer MR, Tanchuck MA, Finn DA, Wiren KM. Importance of genetic background for risk of relapse shown in altered prefrontal cortex gene expression during abstinence following chronic alcohol intoxication. Neuroscience. 2011;173:57–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC, Kodjabachian L, Rebbert ML, Rattner A, Smallwood PM, Samos CH, Nusse R, Dawid IB, Nathans J. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 1999;398(6726):431–436. doi: 10.1038/18899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue O, Suzuki-Inoue K, Dean WL, Frampton J, Watson SP. Integrin alpha2 beta1 mediates outside-in regulation of platelet spreading on collagen through activation of Src kinases and PLCgamma2. J Cell Biol. 2003;160(5):769–780. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS, Donnai D, Black GC, Bieth E, Chassaing N, Lacombe D, Devriendt K, Teebi A, Loscertales M, Robson C, Liu T, MacLaughlin DT, Noonan KM, Russell MK, Walsh CA, Donahoe PK, Pober BR. Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):957–959. doi: 10.1038/ng2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop J, Penick EC, Jensen P, Nickel EJ, Gabrielli WF, Mednick SA, Schulsinger F. Risk factors that predicted problem drinking in Danish men at age thirty. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(6):745–755. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neuroadaptive mechanisms of addiction: studies on the extended amygdale. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Mattan NS, de Vellis J. Canavan disease: a white matter disorder. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2006;12(2):157–165. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewohl JM, Wang L, Miles MF, Zhang L, Dodd PR, Harris RA. Gene expression in human alcoholism: microarray analysis of frontal cortex. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1873–1882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lewohl JM, Dodd PR, Randall PK, Harris RA, Mayfield RD. Gene expression profiling of individual cases reveals consistent transcriptional changes in alcoholic human brain. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1050–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lewohl JM, Harris RA, Iyer VR, Dodd PR, Randall PK, Mayfield RD. Patterns of gene expression in the frontal cortex discriminate alcoholic from nonalcoholic individuals. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31:1574–1582. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lewohl JM, Harris RA, Dodd PR, Mayfield RD. Altered gene expression profiles in the frontal cortex of cirrhotic alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1460–1466. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie PI, Bock KW, Burchell B, Guillemette C, Ikushiro S, Iyanagi T, Miners JO, Owens IS, Nebert DW. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(10):677–685. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173483.13689.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzardo AM, Penick EC, Knop J, Nickel EJ, Hall S, Jensen P, Gabrielli WF., Jr Developmental differences in childhood motor coordination predict adult alcohol dependence: proposed role for the cerebellum in alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(3):353–357. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156126.22194.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzardo AM, Penick EC. A theoretical argument for inherited thiamine insensitivity as one possible biological cause of familial alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30(9):1545–1550. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzardo AM, Madarasz WV, Penick EC, Knop J, Mortensen EL, Sorensen HJ, Mahnken JD, Becker U, Nickel EJ, Gabrielli WF. Effects of premature birth on the risk for alcoholism appear to be greater in males than females. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72(3):390–398. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzardo AM, Henkhaus RS, Butler MG. Global DNA promoter methylation in frontal cortex of alcoholics and controls. Gene. 2012;498:5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto I. Proteomics approach in the study of the pathophysiology of alcohol-related brain damage. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(2):171–176. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield RD, Lewohl JM, Dodd PR, Herlihy A, Liu J, Harris RA. Patterns of gene expression are altered in the frontal and motor cortices of human alcoholics. J Neurochem. 2002;81(4):802–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield RD, Harris RA, Schuckit MA. Genetic factors influencing alcohol dependence. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):275–87. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. Alcoholism and its effects on the central nervous system. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013;10(3):256–262. doi: 10.2174/15672026113109990004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Oehring EM, Jung YC, Sullivan EV, Hawkes WC, Pfefferbaum A, Schulte T. Midbrain-driven emotion and reward processing in alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;38(10):1844–1853. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health. NIAAA Research Monograph No 34. Bethesda, MD: 2000. Review of NIAAA’s Neuroscience and Behavioral Research Portfolio; pp. 437–508. [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A, Dragun D, Walther D, Vorum H, Jacobsen C, Herz J, Melsen F, Christensen EI, Willnow TE. An endocytic pathway essential for renal uptake and activation of the steroid 25-(OH) vitamin D3. Cell. 1999;96(4):507–515. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom M, Rohlfing T, Sullivan EV. Degradation of association and projection white matter systems in alcoholism detected with quantitative fiber tracking. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(8):680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol abuse and dependence in a population based sample of male twins. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:34–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietschel M, Treutlein J. The genetics of alcohol dependence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1282:39–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Peselow E. The neurobiology of addictive disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):269–276. doi: 10.1097/wnf.0b013e3181a9163c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H, Bortolin ML, Seitz H, Cavaille J. Small non-coding RNAs and genomic imprinting. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113(1–4):99–108. doi: 10.1159/000090820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009a;373(9662):492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. An overview of genetic influences in alcoholism. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009b;36(1):S5–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheedy D, Garrick T, Dedova I, Hunt C, Miller R, Sundqvist N, Harper C. An Australian Brain Bank: a critical investment with a high return! Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9(3):205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov BP, Jiang L, Trivedi NS, Aston C. Transcription profiling reveals mitochondrial, ubiquitin and signaling systems abnormalities in postmortem brains from subjects with a history of alcohol abuse or dependence. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72(6):756–767. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. Alcoholism: a systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(2):649–705. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Aliev F, Webb BT, Kendler KS, Williamson VS, Edenberg HJ, Agrawal A, Kos MZ, Almasy L, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Schuckit MA, Kramer JR, Rice JP, Kuperman S, Goate AM, Tischfield JA, Porjesz B, Dick DM. Using genetic information from candidate gene and genome-wide association studies in risk prediction for alcohol dependence. Addict Biol. 2013 Jan 30; doi: 10.1111/adb.12035. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]