Background: Because its N terminus adopts an APK motif, DDB2 might be α-N-methylated.

Results: We examined the nature of DDB2 α-N-methylation, the enzyme involved in this methylation and its function in DNA repair.

Conclusion: DDB2 could be α-N-methylated by NRMT, and this methylation facilitated the recruitment of DDB2 to DNA damage foci.

Significance: This work expands the function of protein α-N-methylation to DNA repair.

Keywords: DNA-binding Protein, DNA Damage, DNA Repair, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Posttranslational Modification (PTM)

Abstract

DDB2 exhibits a high affinity toward UV-damaged DNA, and it is involved in the initial steps of global genome nucleotide excision repair. Mutations in the DDB2 gene cause the genetic complementation group E of xeroderma pigmentosum, an autosomal recessive disease manifested clinically by hypersensitivity to sunlight exposure and an increased predisposition to skin cancer. Here we found that, in human cells, the initiating methionine residue in DDB2 was removed and that the N-terminal alanine could be methylated on its α-amino group in human cells, with trimethylation being the major form. We also demonstrated that the α-N-methylation of DDB2 is catalyzed by the N-terminal RCC1 methyltransferase. In addition, a methylation-defective mutant of DDB2 displayed diminished nuclear localization and was recruited at a reduced efficiency to UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer foci. Moreover, loss of this methylation conferred compromised ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) activation, decreased efficiency in cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer repair, and elevated sensitivity of cells toward UV light exposure. Our study provides new knowledge about the posttranslational regulation of DDB2 and expands the biological functions of protein α-N-methylation to DNA repair.

Introduction

Nucleotide excision repair (NER),2 a versatile DNA repair pathway that eliminates a wide variety of helix-distorting DNA lesions, including UV light-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) and pyrimidine(6-4)pyrimidone photoproducts, as well as bulky DNA adducts induced by numerous environmental carcinogens (1). There are two subpathways of NER, i.e. global genome NER and transcription-coupled NER, which operates throughout the entire genome and removes lesions from transcribed strands of active genes, respectively (1, 2). DDB2 is normally present as a heterodimer, known as UV-DDB, that comprises DDB1 (p127) and DDB2 (p48) (3). UV-DDB serves as a global genome NER factor for the detection of UV-induced DNA damage in chromatin, where the binding of DDB2 to damaged DNA precedes the recruitment of xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C (XPC) to chromatin (4). Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells lacking UV-DDB exhibit a defect in the repair of CPDs but not pyrimidine(6–4)pyrimidone photoproducts (4, 5), and overexpression of DDB2 in Chinese hamster ovary cells can increase UV resistance (6). Furthermore, DDB2 regulates ATM/ATR (ATM and Rad-3 related) activation and decides cell fate by coordinating with XPC (7) and stimulating the proteasomal degradation of p21 (8), respectively.

Protein α-N-methylation is a type of posttranslational modification that is conserved from Escherichia coli to man (9), and a number of proteins were found to be α-N-methylated in eukaryotic cells. In this context, α-N-methylation of histone H2B has been observed in several organisms (10–15). Other eukaryotic proteins known to be α-N-methylated include human regulator of chromosome condensation 1 (RCC1), retinoblastoma protein (Rb), etc. (16–27). Recently, the long-sought α-N-methyltransferase in human and yeast has been discovered (17, 20). The human α-N-methyltransferase NRMT recognizes a common N-terminal sequence motif of XPK (X represents Ser, Pro, or Ala) (17). Lately, the recognition motif of NRMT has been expanded further on the basis of an in vitro peptide methylation assay (18). Considering that DDB2 harbors an N-terminal APK motif, we reason that DDB2 might constitute an NRMT substrate and be α-N-methylated in cells.

Here we report our identification and characterization of α-N-methylation of DDB2. We demonstrated that NRMT could catalyze the α-N-methylation of DDB2 in vitro and in human cells and that this methylation promoted the nuclear localization of DDB2, facilitated the recruitment of DDB2 to CPD foci, augmented CPD repair efficiency, enabled ATM activation, and conferred resistance of human cells toward UV damage. Furthermore, results from our study expand the function of protein α-N-methylation to DNA repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture Conditions

HEK293T human embryonic kidney epithelial cells were purchased from the ATCC. AA8 and GM01389 cells were provided by Dr. Michael M. Seidman (National Institute of Aging). HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (ATCC), and AA8 and GM01389 cells were cultured in α minimal essential medium (ATCC). The media contained 10% (v/v, HEK293T and AA8 cells) or 15% (v/v, GM01389 cells) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Constructs

The expression plasmid for NRMT-His6 was provided by Dr. Ian Macara (17). The human DDB2 open reading frame was amplified to introduce a 5′ XbaI restriction site and a 3′ BamHI site and subcloned into a modified mammalian expression vector, pRK7, in which three tandem repeats of the FLAG epitope tag (DYKDDDK) were inserted between the BamHI and EcoRI sites to give pRK7-DDB2–3×FLAG. The DDB2-K4Q mutant was amplified from the pRK7-DDB2–3×FLAG plasmid using site-directed mutagenesis. DDB2-His6 was generated by subcloning the DDB2 coding sequence with 5′ SacI, the N-terminal X-factor cleavage site (IEGR), and 3′NotI into E. coli expression vector pET28a.

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins

NRMT-His6 and DDB2-His6 were expressed in the Rosetta (DE3) pLysS E. coli strain after growth at 37 °C in Luria broth supplemented with 2% (v/v) ethanol to an A600 nm of ∼0.8, followed by induction with 0.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at room temperature overnight for NRMT-His6 and at 37 °C for 4 h for DDB2-His6. The proteins were then purified by using Talon affinity resin (Clontech) following the recommendations of the manufacturer. pRK7-DDB2–3×FLAG was transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and the resulting C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 was purified by using Anti-FLAG M2 affinity beads (Sigma).

siRNA Knockdown

Control and human NRMT SMARTpool siRNAs were obtained from Thermo Scientific. The sequences of NRMT SMARTpool siRNA were GCGAGGUGAUAGAAGACGA, AGGUGGAUAUGGUCGACAU, UGAGGGAAGGCCCGAACAA, and GGACUGUGGAGCUGGCAUU. HEK293T cells were cultured in 6-well plates in antibiotic-free medium at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well for 24 h and transfected with 100 pmol siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested 48 h later for RT-PCR analysis.

Real-time Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Total RNA Kit I (Omega). cDNA was generated by using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega) and an oligo(dT)16 primer. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR for evaluating the extent of siRNA knockdown was performed by using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix kit (Bio-Rad) and gene-specific primers for NRMT or the control gene GAPDH. The primers were 5′-GCCCTCCCTTCCTCTTCC-3′ and 5′-CCAACCACGGCTCTACTCA-3′ for NRMT and 5′-TTTGTCAAGCTCATTTCCTGGTATG-3′ and 5′-TCTCTTCCTCTTGTGCTCTTGCTG-3′ for GAPDH.

In Vitro Methylation Assay

Purified NRMT-His6 (0.3 μg) was incubated with 1 μg of X-factor-cleaved DDB2-His6 or synthetic N-terminal peptide of DDB2 (Genemed Synthesis, Inc.) with 100 μm S-adenosyl-l-methionine as the methyl donor and brought to 50 μl with methyltransferase buffer (50 mm Tris and 50 mm potassium acetate (pH 8.0)). Reactions were continued at 30 °C for 2 h.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

The FLAG-tagged DDB2 was isolated using affinity purification with anti-FLAG M2 beads. The sample was subsequently reduced, alkylated, and digested with Glu-C at an enzyme:protein ratio of 1:20 (w/w) at room temperature overnight. Peptide mixtures were subjected to online LC-MS/MS analysis with an EASY-nLC II that was coupled with an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Thermo, San Jose, CA), following similar procedures as described previously (28). The separation was conducted by using a homemade trapping column (150 μm × 50 mm) and a separation column (75 μm ×120 mm), packed with ReproSil-Pur C18-AQ resin (3 μm in particle size, Dr. Maisch HPLC GmbH, Germany). Peptide samples were initially loaded onto the trapping column with a solvent mixture of 0.1% formic acid in CH3CN/H2O (2:98, v/v) at a flow rate of 4.0 μl/min. The peptides were then separated with a 90-min linear gradient of 2–40% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid and at a flow rate of 220 nl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated in positive ion mode, and the spray voltage was 1.8 kV. Data were acquired in a data-dependent scan mode, where one full-scan MS was followed with 20 MS/MS scans. To obtain high-quality MS/MS scans, data were also collected in selected ion monitoring mode, where the fragmentations of the protonated ions of the unmodified and mono-, di-, or trimethylated forms of the N-terminal peptide of DDB2 were monitored. All MS/MS data were analyzed manually.

Fluorescence Microscopy

AA8 and GM01389 cells transiently expressing the wild type or the K4Q mutant of DDB2 were grown on glass coverslips and irradiated with UV-C light (254 nm) at 40 J/m2 through a 5-μm isopore polycarbonate filter (Millipore). After irradiation, the membrane was removed, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were subsequently fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde, permeated using 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS, washed with PBS, and then the DNA was denatured by incubation in 2 m HCl for 5 min. Cells were then incubated in a solution containing 20% (v/v) goat serum, 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 5% (w/v) BSA to block nonspecific binding. Primary anti-FLAG (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-CPD (Kamiya Biomedical Co.) antibodies and secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were subsequently added and incubated at 4 °C overnight and then at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation, the coverslips were washed with PBS and mounted onto microscope slides in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Images were captured with a Leica TCS SP2/UV confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems).

Colonogenic Survival Assay

For the survival assay, GM01389 cells, at 24 h following transfection with pRK7-DDB2–3×FLAG, pRK7-DDB2-K4Q-3×FLAG, or empty control, were plated in 6-well plates in triplicate at densities of 200–2000 cells/well. The cells were subsequently exposed to various doses of UV-C light, and the cells were attached to the plates immediately afterwards. Cell colonies grown for 10–14 days (29) were then fixed using 6% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet. Colonies containing at least 50 cells were counted under a microscope.

Nuclear Fractionation and Western Blot Analysis

HEK293T cells transiently expressing wild-type DDB2 or DDB2-K4Q were collected immediately or at 30 min after irradiation with 40 J/m2 UV-C light. The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained using a NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Thermo Scientific), following the recommendations of the manufacturer. Antibodies that specifically recognize histone H3 and the FLAG epitope tag were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and used at 1:10,000 dilution. Antibody that specifically recognizes human actin (Abcam) was used at 1:5000 dilution. For ATM activation, antibodies that specifically recognize human ATM or phospho-ATM (Ser-1981) and human CHK1 or phospho-CHK1 (Ser-345) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology and used at 1:1000 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam) was used at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Flow Cytometry-based DNA Repair Assay

The CPD repair assay was performed following similar procedures as described previously (30). GM01389 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells/well. After 16 h, plasmids overexpressing wild-type DDB2 or the DDB2-K4Q mutant and the empty control were transfected individually into the plated GM01389 cells. 28 h after transfection, DMEM was replaced with 1× PBS buffer, and the cells were irradiated with UV-C light at 10 J/m2. After irradiation, the PBS buffer was removed, and fresh medium with 200 ng/ml nocodazole was added to the cells. At various time intervals following UV irradiation, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in 125 μl of PBS, and fixed by adding 375 μl of prechilled 100% ethanol at −20 °C for at least 1 h. The cells were subsequently permeated and denatured with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 in 2 N HCl in doubly-distilled H2O at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS with 100 μg/ml RNase at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, cells were blocked in blocking buffer containing 5% (v/v) bovine serum albumin and 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were then resuspended in blocking buffer containing mouse anti-CPD antibody (Kamiya Biomedical Co., 1:1000 dilution) at room temperature for 45 min and then at 4 °C overnight. Cell pellets were subsequently washed three times with washing buffer containing 0.3% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS and then resuspended in Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-mouse antibody (1:200 dilution, Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h. Pellets were again washed three times with washing buffer and then resuspended in sorting buffer (1× PBS, 1 mm EDTA, 25 mm HEPES, 1% FBS, v/v (pH 7.0)) for flow cytometry analysis (BD Biosciences FACSAria I).

RESULTS

Human DDB2 Is Mono-, Di-, and Trimethylated on the α-Amino Group of Its N-terminal Alanine Residue

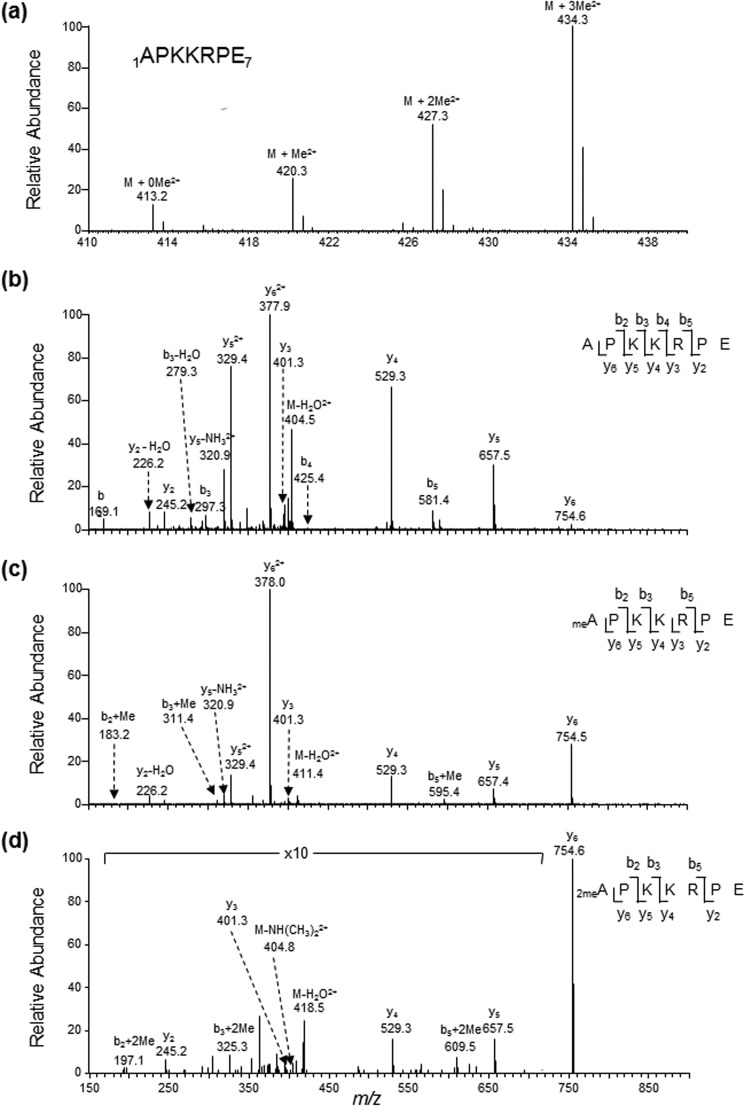

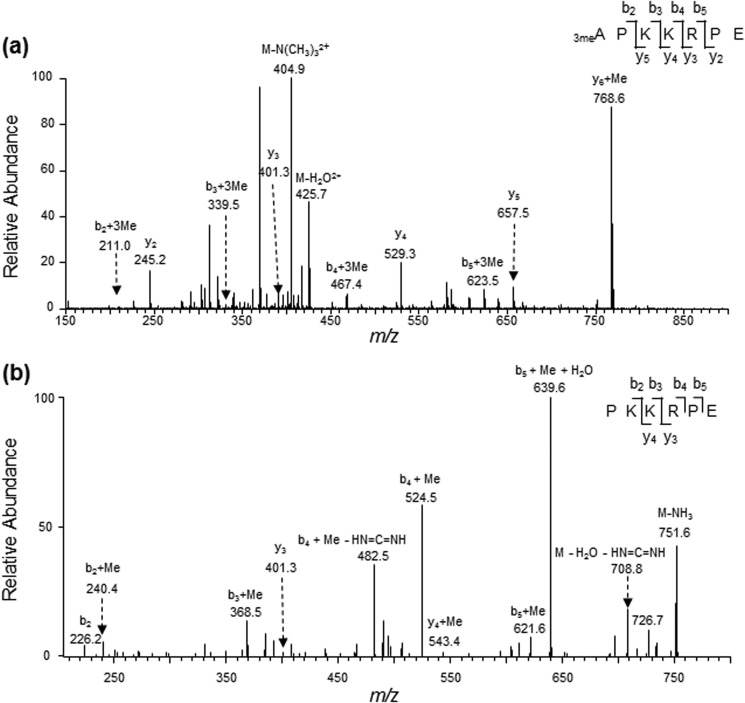

We first assessed whether DDB2 can be α-N-methylated. To this end, we expressed the C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 in HEK293T cells and purified the protein from the cell lysate using anti-FLAG M2 beads (Fig. 1a). Glu-C digestion of the resulting protein yields the N-terminal peptide of APKKRPE. From our MS result, we were able to identify doubly charged ions of the unmodified as well as the mono-, di-, and trimethylated forms of the peptide 1APKKRPE7 at m/z values of 413.2481, 420.2558, 427.2634, and 434.2742, respectively (Fig. 2a). As depicted in Figs. 2, b–d, and 3a, we observed the y2-y6 ions for the mono- and dimethylated peptide and the y2, y3-y5 ions for trimethylated peptide. These ions displayed the same m/z values as those for the corresponding unmodified peptide. In addition, we observed the b2+Me, b3+Me, and b5+Me ions in the MS/MS of the monomethylated peptide as well as the b2+2Me, b3+2Me, and b5+2Me ions and neutral loss of an NH(CH3)2 in the MS/MS for the dimethylated peptide (Fig. 2, c and d). On the other hand, the MS/MS for the corresponding trimethylated peptide displays the b2+3Me, b3+3Me, b4+3Me, and b5+3Me ions and a fragment ion arising from the elimination of an N(CH3)3 (Fig. 3a). The observation of the y6+Me ion for the trimethylated peptide (Fig. 3a) can perhaps be attributed to the methyl group migration prior to amide bond cleavage during collisional activation, as observed previously (31). To further confirm this, we acquired the MS/MS/MS arising from the further fragmentation of the y6+Me ion found in the MS/MS of the trimethylated peptide (Fig. 3b). The observation of the b2, b2+Me, b3+Me, b4+Me, and b5+Me+H2O ions, but not the b3, b4, or b5+H2O ion, demonstrated that the methyl group is migrated to the third lysine or one of the two residues on the N-terminal portion (proline or lysine). In this regard, the ion of m/z 639.6 seen in Fig. 3b may potentially be attributed to the y5-H2O ion. The observation of the b5+H2O, but not the y5-H2O, ion in the MS/MS/MS for the y6 ion of the dimethylated peptide (supplemental Fig. S1) suggests that the ion of m/z 639.6 can only be assigned to the b5+Me+H2O ion. Together, the above results provide solid evidence for supporting the mono-, di-, and trimethylation of the N terminus of DDB2.

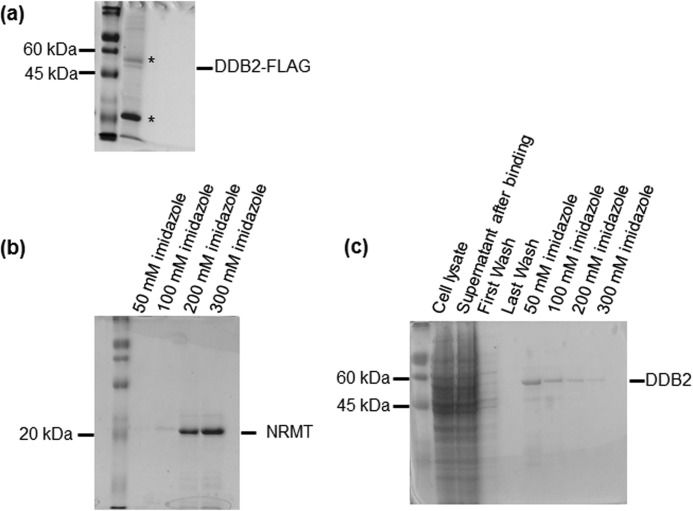

FIGURE 1.

SDS-PAGE characterizations of recombinant DDB2 and NRMT. Shown are the SDS-PAGE gels for the C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells (a), NRMT-His6 (b), and DDB2-His6 (c) purified from E. coli Rosetta (DE3) pLysS cells. The asterisks indicate antibody heavy and light chains.

FIGURE 2.

Electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS and MS/MS characterizations of α-N-methylation of DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells. a, ESI-MS showing the presence of unmodified as well as mono-, di-, and tri-α-N-methylated forms of the peptide 1APKKRPE7 of C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells. b–d, ESI-MS/MS of the unmodified (b) as well as the mono- (c) and dimethylated (d) forms of the peptide 1APKKRPE7. A region of the spectrum in d was amplified to better visualize the peaks of some fragment ions of low abundance.

FIGURE 3.

MS/MS and MS/MS/MS characterizations of the α-N-trimethylated peptide of DDB2. a, ESI-MS/MS of the trimethylated form of the peptide 1APKKRPE7 arising from the Glu-C digestion of C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells. b, MS/MS/MS of the y6+Me ion found in the MS/MS scan of the trimethylated form of the peptide 1APKKRPE7.

NRMT Can Catalyze the α-N-Methylation of DDB2 in Human Cells and in Vitro

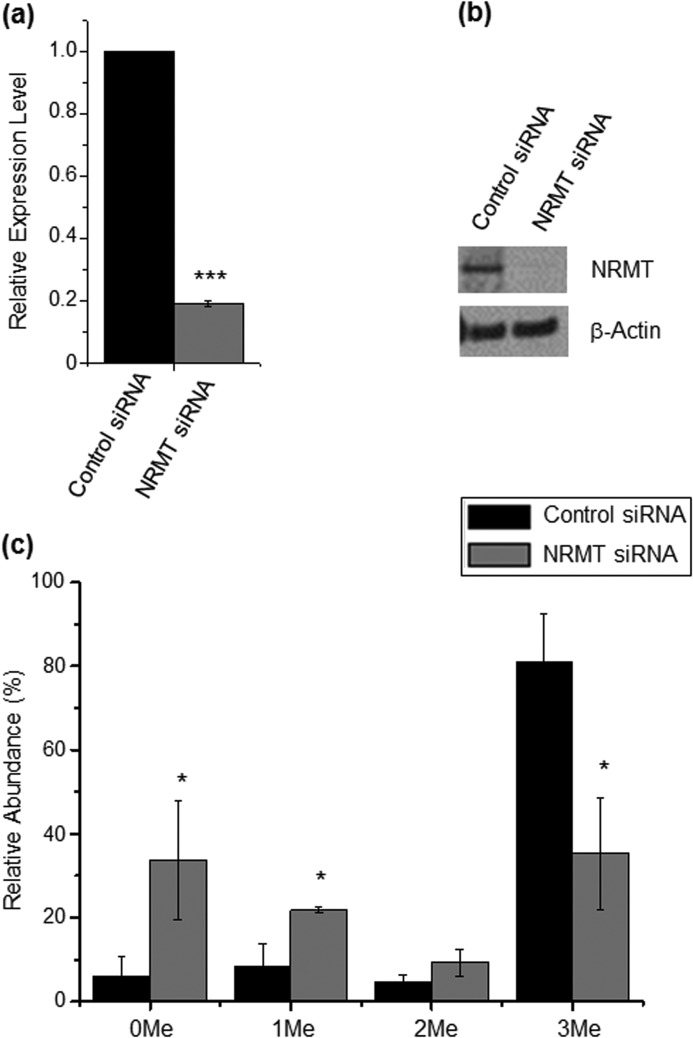

Considering that NRMT can catalyze the α-N-methylation of RCC1 and several other human proteins carrying the conserved N-terminal XPK motif, we asked whether this enzyme can also induce the α-N-methylation of DDB2, which harbors an N-terminal APK motif. To this end, we knocked down the expression of NRMT in HEK293T cells by using siRNA and cotransfected the cells with NRMT siRNA together with the plasmid for expressing the C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2. Quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analysis results showed that the NRMT knockdown efficiency was greater than 80% (Fig. 4, a and b). We then estimated the extent of N-terminal methylation on the basis of the relative abundances of precursor ions for the methylated and unmodified peptides of the C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells. Following NRMT knockdown, there is a significant reduction in the level of α-N-methylation in DDB2 relative to that observed for DDB2 isolated from cells treated with control, non-targeting siRNA (Fig. 4c). In this regard, it is worth noting that methylation may alter the ionization efficiency of the N-terminal peptide. Thus, the absolute methylation levels may differ from those estimated from the relative ion abundances. Nevertheless, the method still offers a valid comparison of the relative levels of methylation of DDB2 isolated from cells with or without NRMT knockdown.

FIGURE 4.

NRMT can catalyze the α-N-methylation of DDB2 in cells. a, relative mRNA level of NRMT by real-time PCR using GAPDH as a control. b, relative level of NRMT protein by Western analysis using β-actin as a control. c, relative abundances of different methylation forms of the N-terminal peptide APKKRPE of DDB2 isolated from HEK293T cells treated with control and NRMT siRNA, as determined by semiquantitative MS analysis. The results represent the mean ± S.E. of results obtained from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, ***, p < 0.001. The p values were calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test.

We next examined whether NRMT could catalyze the α-N-methylation of DDB2 in vitro. To this end, we generated the recombinant His6-tagged NRMT and DDB2 (Fig. 1, b–c). To remove the initial methionine, we generated the recombinant DDB2 protein that is fused with a His6 tag and factor X (a protease) recognition sequence on the N terminus. Cleavage with factor X exposes the second residue of DDB2 (i.e. alanine) for α-N-methylation. LC-MS/MS analysis of the Glu-C digestion mixture of the in vitro methylated DDB2 revealed the presence of mono-, di-, and trimethylated N-terminal peptide (supplemental Fig. S2, b and c) and the absence of methylated N-terminal peptide in samples without the addition of NRMT (supplemental Fig. S2a).

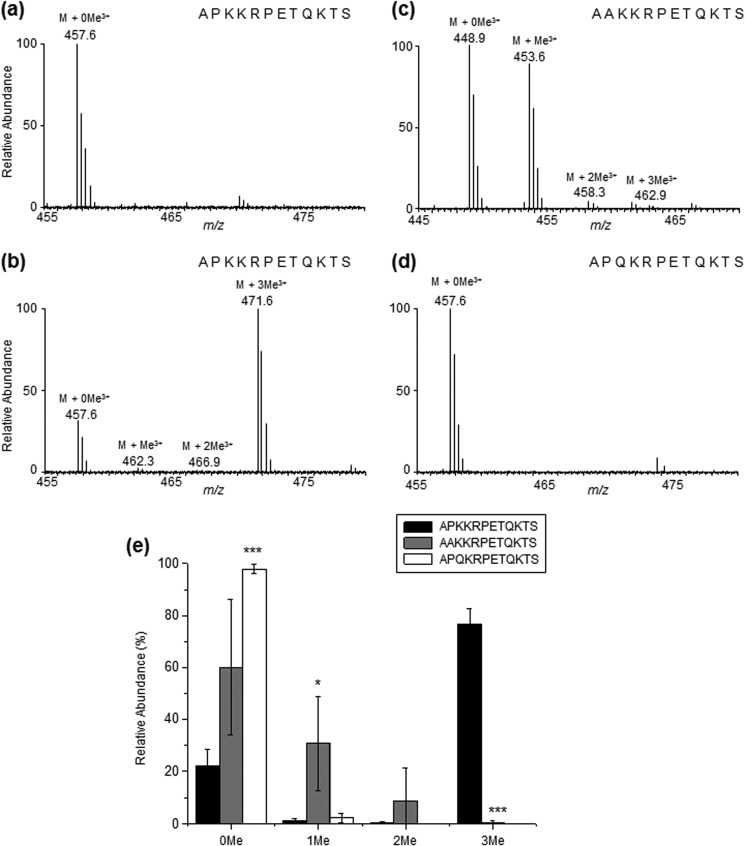

To assess whether the folding of DDB2 is required for α-N-methylation, we also incubated the peptide containing the N-terminal 12 amino acids of DDB2 (without the initial methionine) with NRMT together with S-adenosyl-l-methionine in vitro. Our MS and MS/MS results revealed unequivocally the mono-, di-, and trimethylation of the N terminus of the peptide 1APKKRPETQKTS12 (Fig. 5b and supplemental Fig. S3). As expected, we only observed the unmodified form of the peptide when NRMT was not included in the reaction (Fig. 5a). We conclude that NRMT can catalyze the α-N-methylation of DDB2.

FIGURE 5.

NRMT can catalyze the α-N-methylation of DDB2 in vitro. a, ESI-MS of unmodified forms of the peptide 1APKKRPETQKTS12 without addition of NRMT. b, ESI-MS of the unmodified, mono-, di-, and tri-α-N-methylated forms of the peptide 1APKKRPETQKTS12 with addition of NRMT. c, ESI-MS of the unmodified, mono-, di-, and tri-α-N-methylated forms of the peptide DDB2-P3A (i.e. 1AAKKRPETQKTS12, with the addition of NRMT). d, ESI-MS of unmodified, mono-, di-, and tri-α-N-methylated forms of the peptide DDB2-K4Q (i.e. 1APQKRPETQKTS12, with the addition of NRMT). e, relative abundances of different methylation forms of the N-terminal 12 amino acids of DDB2, DDB2-P3A, and DDB2-K4Q as determined by semiquantitative MS analysis. The results represent the mean ± S.E. of results obtained from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. The p values were calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test.

The Proline and Lysine in the APK Motif Are Important for the α-N-Methylation of DDB2

In light of the importance of the XPK motif in α-N-methylation, we also performed an in vitro methylation assay with the 12-amino acid peptide variants 1AAKKRPETQKTS12 and 1APQKRPETQKTS12, where the Pro and Lys in the XPK motif were mutated to Ala and Gln, respectively. As displayed in Fig. 5, c–e, relative to the wild-type sequence, the methylation level for 1AAKKRPETQKTS12 is decreased profoundly, whereas 1APQKRPETQKTS12 was predominantly unmethylated. (The MS/MS results are shown in supplemental Figs. S4 and S5.) Hence, we constructed a plasmid allowing for the expression of the C-terminally FLAG-tagged DDB2-K4Q mutant and examined whether the mutant protein can be methylated in cells. In keeping with the in vitro result, LC-MS/MS analysis showed that the unmodified peptide APQKRPE could be readily detected in the Glu-C digestion mixture of the DDB2-K4Q mutant isolated from HEK293T cells. However, the corresponding methylated peptides were below the detection limit (supplemental Fig. S6). In this vein, it has been observed previously that the K4Q mutant of RCC1 or centromere protein B (CENP-B) could not be methylated on the N termini by NRMT (16, 26).

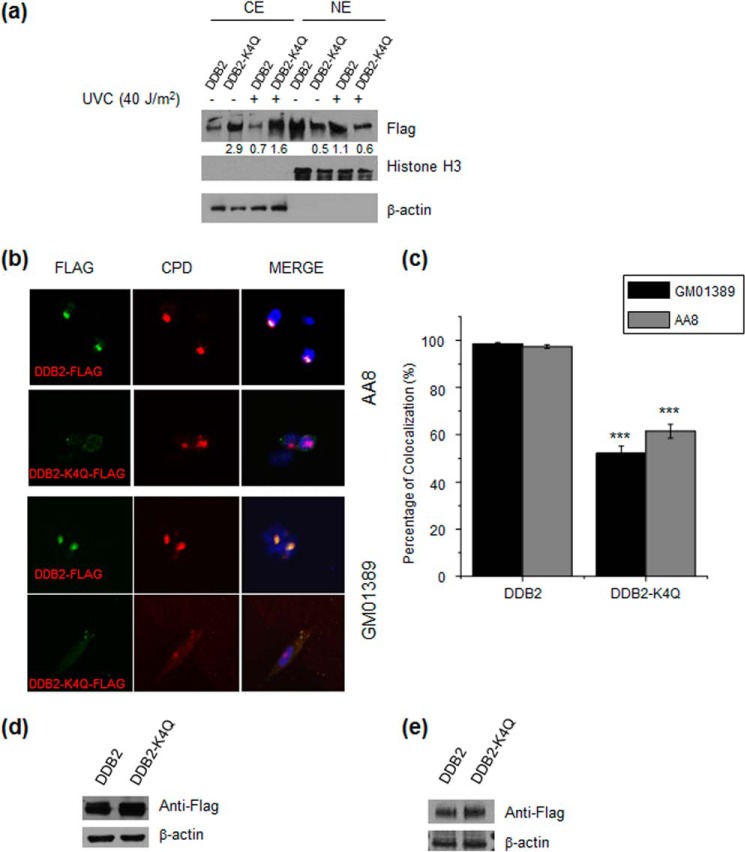

α-N-Methylation Affects the Nuclear Localization of DDB2 and Its Recruitment to CPD Foci

Previous studies showed that DDB2 is recruited rapidly to CPD foci in cells following exposure to UV irradiation (32). We reason that the α-N-trimethylation of DDB2 may affect its intracellular localization and its binding to damaged DNA. In this regard, the α-N-methylation of DDB2 may promote its nuclear localization by facilitating its interaction with other nuclear proteins that can recognize this methylation mark, and there are many cellular protein readers that can recognize the side chains of methylated lysine and arginine (33). To test this, we transfected HEK293T cells with FLAG-tagged DDB2 and DDB2-K4Q expression vectors and examined the distribution of the wild-type and mutant DDB2 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions before and after treatment with UV-C light. Our results demonstrated that, with or without UV-C light exposure, the methylation-defective mutant displayed a reduced presence in the nuclear fraction, unlike wild-type DDB2 (Fig. 6a).

FIGURE 6.

α-N-methylation is important for the nuclear localization and recruitment of DDB2 to DNA damage foci. a, Western blot analysis revealed less nuclear localization and more cytoplasmic localization of DDB2-K4Q than wild-type DDB2 in HEK293T cells with or without exposure to UV-C light. β-actin was used as a loading control for the cytoplasmic extract (CE), and histone H3 was used as a loading control for the nuclear extract (NE). b, representative images for monitoring the colocalization of transfected wild-type DDB2 and DDB2-K4Q to CPD foci in AA8 and GM01389 cells. c, percentage of CPD foci that are colocalized with DDB2 foci. In cells transfected with the wild-type DDB2 construct, almost all CPD foci colocalization with DDB2 foci, whereas only a portion of CPD foci colocalized with DDB2 foci in cells transfected with the DDB2-K4Q plasmid. The results represent the mean ± S.E. of results obtained from three biological replicates, and ∼100 cells were counted in each replicate. ***, p < 0.001. The p values were calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test. d and e, Western blot analysis of wild-type DDB2 and DDB2-K4Q in whole-cell extracts of AA8 (d) and GM01389 (e) cells transfected with the corresponding DDB2 constructs. β-actin was used as a loading control.

We next examined whether deficient α-N-methylation affects the recruitment of DDB2 to CPD foci. To this end, we transfected FLAG-tagged DDB2 and DDB2-K4Q expression vectors into AA8 CHO cells that do not express endogenous UV-DDB (32). As shown in Fig. 6, b–c, immunofluorescence analyses using anti-FLAG and anti-CPD antibodies revealed that 97.4% of CPD foci colocalized with DDB2 foci in cells transfected with the wild-type DDB2 construct, whereas only 61.5% of the CPD foci colocalized with DDB2 foci in AA8 cells transfected with the plasmid for DDB2-K4Q. To further strengthen this finding, we conducted similar experiments using human xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group E cells (GM01389) that do not carry a functional DDB2. Fig. 6, b and c, shows that 98.5% of CPD foci colocalized with DDB2 foci in GM01389 cells transfected with the wild-type DDB2 construct, whereas only 52.2% of the CPD foci colocalized with DDB2 foci in cells transfected with the plasmid for DDB2-K4Q. In this vein, it is worth noting that wild-type DDB2 and the DDB2-K4Q mutant were expressed at similar levels in GM01389 and AA8 cells, as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6, d and e). Thus, the above results demonstrate that α-N-methylation plays a significant role in the recruitment of DDB2 to CPD foci.

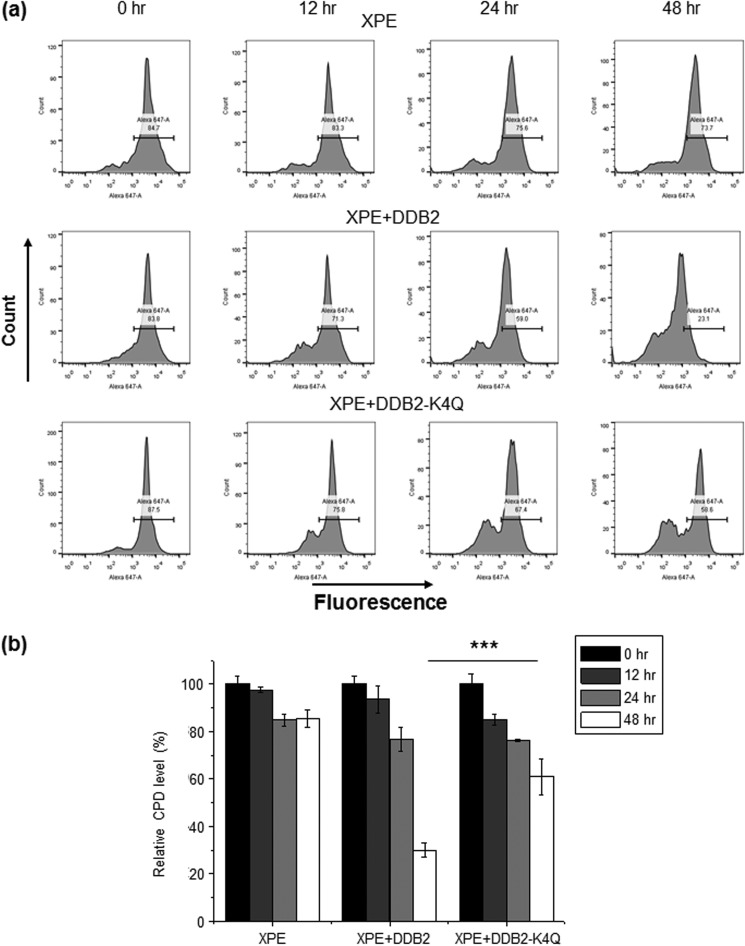

α-N-Methylation of DDB2 Facilitates CPD Repair in GM01389 Cells

Seeing that the methylation-defective mutant of DDB2 exhibited diminished nuclear localization and reduced recruitment to CPD foci, we next examined whether the α-N-methylation of DDB2 plays a role in CPD repair using a flow cytometry-based method (30). Our results showed that ∼70% of CPD was removed in GM01389 cells transfected with the wild-type DDB2 construct, whereas only about 39% of the CPD was repaired in cells transfected with the DDB2-K4Q plasmid 48 h following UV-C exposure (Fig. 7). Thus, α-N-methylation enhances CPD repair in human cells.

FIGURE 7.

α-N-methylation of DDB2 stimulates CPD repair in human cells. a, flow cytometry results showing the level of CPD in GM01389 with empty control, wild-type DDB2, and DDB2-K4Q at various time intervals (0, 12, 24, and 48 h) after irradiation with 10 J/m2 UV-C light. b, quantitative results showing that CPD was repaired more efficiently in GM01389 cells with transient expression of wild-type DDB2 than in those with DDB2-K4Q. The results represent the mean ± S.E. of data obtained from three biological replicates. ***, p < 0.001. The p values were calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test.

α-N-Methylation of DDB2 Promotes ATM Activation in GM01389 Cells

DDB2, as an early UV damage recognition factor, has been shown previously to be crucial for ATM recruitment to DNA damage sites and for its activation (7). On the grounds that diminished α-N-trimethylation resulted in reduced recruitment of DDB2 to DNA damage sites, we reason that defective α-N-trimethylation may also compromise the recruitment and activation of downstream DNA damage response factors, including ATM. Hence, we assessed ATM activation by monitoring the phosphorylation levels of ATM-Ser-1981 and CHK1-Ser-345 using Western blot analysis. It turned out that the overexpression of wild-type DDB2, but not its K4Q mutant, can significantly enhance the phosphorylation levels of ATM-Ser-1981 and CHK1-Ser-345 after UV-C damage (Fig. 8a).

FIGURE 8.

α-N-methylation of DDB2 is important for ATM activation and for cellular resistance toward UV irradiation. a, 30 min after irradiation with 25 J/m2 UV-C light, ATM autophosphorylation (ATM-S1981p) and CHK1 phosphorylation (CHK1-S345p) were increased in GM01389 cells complemented with wild-type DDB2 but not the α-N-methylation-defective DDB2-K4Q mutant. b, after siRNA-induced knockdown of NRMT, ATM autophosphorylation and CHK1 phosphorylation were reduced relative to control siRNA knockdown in HEK293T cells 30 min after irradiation with 25 J/m2 UV-C light. c, α-N-methylation is important for cellular resistance toward UV-induced cytotoxicity. Shown is the cellular sensitivity toward UV-C light as measured by clonogenic survival assay. The results represent the mean ± S.E. of results obtained from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. The p values were calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test.

We also knocked down the expression of NRMT in HEK293T cells using siRNA and monitored how ATM activation is affected by the resulting reduced α-N-trimethylation of DDB2. Our results showed that NRMT knockdown indeed led to diminished phosphorylation of ATM-Ser-1981 and CHK1-Ser-345 (Fig. 8b). In this context, it is worth noting that the reduced ATM activation may also be attributed to the diminished methylation of other NRMT substrates that may also play an important role in ATM activation. Taken together, our results support that α-N-methylation of DDB2 is important for ATM activation.

α-N-Methylation Is Crucial for Cellular Resistance toward UV Light

Reduced recruitment of DDB2 to CPD sites and diminished ATM activation could result in compromised repair of CPD lesions, which may convey elevated sensitivity of cells to UV light. To test this, we assessed the viability of GM01389 cells by employing clonogenic survival assays. Our results showed that the proliferating ability of GM01389 cells is enhanced substantially in cells complemented with wild-type DDB2 but not the DDB2-K4Q mutant (Fig. 8c). These results support that α-N-methylation of DDB2 can protect cells from the cytotoxic effects conferred by UV damage.

DISCUSSION

We found that DDB2 can be α-N-methylated by NRMT in human cells and in vitro. In addition, an in vitro methylation assay demonstrated that changing the proline in the XPK motif to an alanine markedly reduces the α-N-methylation of the protein, whereas mutating the lysine in the motif to a glutamine abolishes the methylation. The availability of the DDB2-K4Q mutant defective in α-N-methylation allows us to examine the biological function of α-N-methylation. Our results illustrate that the α-N-methylation of DDB2 facilitates the localization of DDB2 to the DNA damage site, perhaps by enhancing the binding activity of DDB2 to DNA and/or by promoting its nuclear localization. In addition, the α-N-methylation of DDB2 plays an important role in ATM activation, and it confers resistance of human cells to UV damage.

The functions of phosphorylation and ubiquitination of DDB2 have been studied extensively. UV-DDB associates tightly with the CUL4-ROC1 complex, which exhibits ubiquitin ligase activity (34). Following UV irradiation, the UV-DDB complex localizes to the UV damage-enriched mononucleosome fraction, and DDB2 is subsequently polyubiquitinated (35). Polyubiquitination of DDB2 reduces its binding affinity to DNA damage sites and is speculated to facilitate the handover of the lesion to XPC (36). In addition, DDB2 can be phosphorylated by c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase, and this phosphorylation suppresses the binding of DDB2 to UV-damaged DNA (37). On the other hand, p38 MAPK, a serine/threonine protein kinase, can facilitate the recruitment of the NER factors XPC and transcription factor II H (TFIIH) to UV-induced DNA damage sites by phosphorylating DDB2 (38).

Unlike methylation on the side chains of arginine and lysine residues, which has attracted great attention because these modifications on the N-terminal tails of core histones play a crucial role in chromatin structure and function (39), the biological functions of α-N-methylation for most eukaryotic proteins, except for RCC1 (16), centromere protein A (CENP-A) (27), and CENP-B (26), remain undefined. In this vein, the α-N-methylation of RCC1 has been shown to be important for spindle pole assembly, and the RCC1 mutants deficient in N-terminal α-methylation bind much more weakly to chromatin during mitosis, which induces a spindle pole defect (16). The α-N-trimethylation of CENP-B can enhance its binding to the CENP-B box on human α-satellite DNA and mouse centromeric minor satellite DNA (26). On the grounds that trimethylation introduces a quaternary ammonium ion, a permanent cation (9), to the N terminus of the protein, α-N-trimethylation may enhance the binding of the protein to DNA through electrostatic interaction between the protein N terminus and phosphate groups in DNA. Therefore, a similar principle may account for the observations made in our study. In addition, α-N-methylation may also affect the function of DDB2 by modulating its interaction with other cellular proteins and by altering its intracellular localization. Further investigations are required to exploit the mechanism underlying the observed biological functions of DDB2 introduced by α-N-methylation.

In conclusion, we uncovered a novel type of posttranslational modification for DDB2, identified the enzyme involved in this methylation, and revealed the role of this methylation in repair of UV-induced CPD lesions. Our results also expanded the function of protein α-N-methylation to DNA repair.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 ES019873.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- NER

- nucleotide excision repair

- CPD

- cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer

- NRMT

- N-terminal RCC1 methyltransferase

- XPC

- xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

- ATM and Rad 3-related

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- CENP-B

- centromere protein B.

REFERENCES

- 1. de Laat W. L., Jaspers N. G., Hoeijmakers J. H. (1999) Molecular mechanism of nucleotide excision repair. Genes Dev. 13, 768–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanawalt P. C. (2002) Subpathways of nucleotide excision repair and their regulation. Oncogene 21, 8949–8956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keeney S., Chang G. J., Linn S. (1993) Characterization of a human DNA damage binding protein implicated in xeroderma pigmentosum E. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 21293–21300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moser J., Volker M., Kool H., Alekseev S., Vrieling H., Yasui A., van Zeeland A. A., Mullenders L. H. (2005) The UV-damaged DNA binding protein mediates efficient targeting of the nucleotide excision repair complex to UV-induced photo lesions. DNA Repair 4, 571–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang J. Y., Hwang B. J., Ford J. M., Hanawalt P. C., Chu G. (2000) Xeroderma pigmentosum p48 gene enhances global genomic repair and suppresses UV-induced mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 5, 737–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sun N. K., Lu H. P., Chao C. C. (2002) Overexpression of damaged-DNA-binding protein 2 (DDB2) potentiates UV resistance in hamster V79 cells. Chang Gung Med. J. 25, 723–733 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ray A., Milum K., Battu A., Wani G., Wani A. A. (2013) NER initiation factors, DDB2 and XPC, regulate UV radiation response by recruiting ATR and ATM kinases to DNA damage sites. DNA Repair 12, 273–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stoyanova T., Roy N., Kopanja D., Bagchi S., Raychaudhuri P. (2009) DDB2 decides cell fate following DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10690–10695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stock A., Clarke S., Clarke C., Stock J. (1987) N-terminal methylation of proteins: structure, function and specificity. FEBS Lett. 220, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xiong L., Adhvaryu K. K., Selker E. U., Wang Y. (2010) Mapping of lysine methylation and acetylation in core histones of Neurospora crassa. Biochemistry 49, 5236–5243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Medzihradszky K. F., Zhang X., Chalkley R. J., Guan S., McFarland M. A., Chalmers M. J., Marshall A. G., Diaz R. L., Allis C. D., Burlingame A. L. (2004) Characterization of Tetrahymena histone H2B variants and posttranslational populations by electron capture dissociation (ECD) Fourier transform ion cyclotron mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 872–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nomoto M., Kyogoku Y., Iwai K. (1982) N-trimethylalanine, a novel blocked N-terminal residue of Tetrahymena histone H2B. J. Biochem. 92, 1675–1678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonenfant D., Coulot M., Towbin H., Schindler P., van Oostrum J. (2006) Characterization of histone H2A and H2B variants and their post-translational modifications by mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Desrosiers R., Tanguay R. M. (1988) Methylation of Drosophila histones at proline, lysine, and arginine residues during heat-shock. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 4686–4692 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinage A., Briand G., Van Dorsselaer A., Turner C. H., Sautiere P. (1985) Primary structure of histone H2b from gonads of the starfish Asterias-rubens: Identification of an N-dimethylproline residue at the amino-terminal. Eur. J. Biochem. 147, 351–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen T., Muratore T. L., Schaner-Tooley C. E., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Macara I. G. (2007) N-terminal a-methylation of RCC1 is necessary for stable chromatin association and normal mitosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 596–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tooley C. E., Petkowski J. J., Muratore-Schroeder T. L., Balsbaugh J. L., Shabanowitz J., Sabat M., Minor W., Hunt D. F., Macara I. G. (2010) NRMT is an a-N-methyltransferase that methylates RCC1 and retinoblastoma protein. Nature 466, 1125–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petkowski J. J., Schaner Tooley C. E., Anderson L. C., Shumilin I. A., Balsbaugh J. L., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Minor W., Macara I. G. (2012) Substrate specificity of mammalian N-terminal a-amino methyltransferase NRMT. Biochemistry 51, 5942–5950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henry G. D., Dalgarno D. C., Marcus G., Scott M., Levine B. A., Trayer I. P. (1982) The occurrence of α-N-trimethylalanine as the N-terminal amino-acid of some myosin light-chains. FEBS Lett. 144, 11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Webb K. J., Lipson R. S., Al-Hadid Q., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. G. (2010) Identification of protein N-terminal methyltransferases in yeast and humans. Biochemistry 49, 5225–5235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Porras-Yakushi T. R., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. (2006) A novel SET domain methyltransferase in yeast: Rkm2-dependent trimethylation of ribosomal protein L12ab at lysine 10. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35835–35845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sadaie M., Shinmyozu K., Nakayama J. (2008) A conserved SET domain methyltransferase, Set11, modifies ribosomal protein Rpl12 in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7185–7195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carroll A. J., Heazlewood J. L., Ito J., Millar A. H. (2008) Analysis of the Arabidopsis cytosolic ribosome proteome provides detailed insights into its components and their post-translational modification. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 347–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith G. M., Pettigrew G. W. (1980) Identification of N,N-dimethylproline as the N-terminal blocking group of Crithidia-oncopelti cytochrome-C557. Eur. J. Biochem. 110, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meng F., Du Y., Miller L. M., Patrie S. M., Robinson D. E., Kelleher N. L. (2004) Molecular-level description of proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae using quadrupole FT hybrid mass spectrometry for top down proteomics. Anal. Chem. 76, 2852–2858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dai X., Otake K., You C., Cai Q., Wang Z., Masumoto H., Wang Y. (2013) Identification of novel α-N-methylation of CENP-B that regulates its binding to the centromeric DNA. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4167–4175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bailey A. O., Panchenko T., Sathyan K. M., Petkowski J. J., Pai P. J., Bai D. L., Russell D. H., Macara I. G., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Black B. E., Foltz D. R. (2013) Posttranslational modification of CENP-A influences the conformation of centromeric chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11827–11832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang F., Dai X., Wang Y. (2012) 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine induced growth inhibition of leukemia cells through modulating endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, M111.016915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ziv Y., Bielopolski D., Galanty Y., Lukas C., Taya Y., Schultz D. C., Lukas J., Bekker-Jensen S., Bartek J., Shiloh Y. (2006) Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 870–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rouget R., Auclair Y., Loignon M., Affar el B., Drobetsky E. A. (2008) A sensitive flow cytometry-based nucleotide excision repair assay unexpectedly reveals that mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling does not regulate the removal of UV-induced DNA damage in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5533–5541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xiong L., Ping L., Yuan B., Wang Y. (2009) Methyl group migration during the fragmentation of singly charged ions of trimethyllysine-containing peptides: precaution of using MS/MS of singly charged ions for interrogating peptide methylation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 20, 1172–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hwang B. J., Toering S., Francke U., Chu G. (1998) p48 Activates a UV-damaged-DNA binding factor and is defective in xeroderma pigmentosum group E cells that lack binding activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4391–4399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel D. J., Wang Z. (2013) Readout of epigenetic modifications. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 81–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Groisman R., Polanowska J., Kuraoka I., Sawada J., Saijo M., Drapkin R., Kisselev A. F., Tanaka K., Nakatani Y. (2003) The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell 113, 357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matsuda N., Azuma K., Saijo M., Iemura S., Hioki Y., Natsume T., Chiba T., Tanaka K. (2005) DDB2, the xeroderma pigmentosum group E gene product, is directly ubiquitylated by Cullin 4A-based ubiquitin ligase complex. DNA Repair 4, 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sugasawa K., Okuda Y., Saijo M., Nishi R., Matsuda N., Chu G., Mori T., Iwai S., Tanaka K., Tanaka K., Hanaoka F. (2005) UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex. Cell 121, 387–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cong F., Tang J., Hwang B. J., Vuong B. Q., Chu G., Goff S. P. (2002) Interaction between UV-damaged DNA binding activity proteins and the c-Abl tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34870–34878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao Q., Barakat B. M., Qin S., Ray A., El-Mahdy M. A., Wani G., Arafa el-S., Mir S. N., Wang Q. E., Wani A. A. (2008) The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase augments nucleotide excision repair by mediating DDB2 degradation and chromatin relaxation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32553–32561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jenuwein T., Allis C. D. (2001) Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.