Background: Preproinsulin signal peptide mutations have been linked to human diabetes.

Results: Preproinsulin mutants fail to be fully translocated across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, accumulate in the cytosol, and lead to β cell death.

Conclusion: Cytosolic preproinsulin accumulation contributes to β cell failure.

Significance: This reveals a novel pathogenesis of diabetes associated with inefficient preproinsulin translocation and cytosolic accumulation.

Keywords: β Cell, Diabetes, Insulin Synthesis, Mutant, Protein Translocation, Cytosolic Protein Accumulation, Preproinsulin, Proinsulin

Abstract

Among the defects in the early events of insulin biosynthesis, proinsulin misfolding and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress have drawn increasing attention as causes of β cell failure. However, no studies have yet addressed potential defects at the cytosolic entry point of preproinsulin into the secretory pathway. Here, we provide the first evidence that inefficient translocation of preproinsulin (caused by loss of a positive charge in the n region of its signal sequence) contributes to β cell failure and diabetes. Specifically, we find that, after targeting to the ER membrane, preproinsulin signal peptide (SP) mutants associated with autosomal dominant late-onset diabetes fail to be fully translocated across the ER membrane. The newly synthesized, untranslocated preproinsulin remains strongly associated with the ER membrane, exposing its proinsulin moiety to the cytosol. Rather than accumulating in the ER and inducing ER stress, untranslocated preproinsulin accumulates in a juxtanuclear compartment distinct from the Golgi complex, induces the expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), and promotes β cell death. Restoring an N-terminal positive charge to the mutant preproinsulin SP significantly improves the translocation defect. These findings not only reveal a novel molecular pathogenesis of β cell failure and diabetes but also provide the first evidence of the physiological and pathological significance of the SP n region positive charge of secretory proteins.

Introduction

In pancreatic β cells, insulin biosynthesis begins within the cytosol, where insulin mRNA is translated into the precursor preproinsulin. Preproinsulin comprises, sequentially, signal peptide (SP),6 insulin B chain, C peptide, and A chain (1, 2). To enter the secretory pathway, nascent preproinsulin is delivered by the signal recognition particle (SRP) to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, where preproinsulin is translocated to the luminal side of the ER and cleaved by signal peptidase, forming proinsulin (3, 4). Within the oxidizing environment of the ER lumen, proinsulin undergoes rapid oxidative folding, forming three evolutionarily conserved disulfide bonds (5–8). Among these early events, proinsulin misfolding in the ER lumen and the consequent ER stress have been shown to play an important role in the autosomal dominant syndrome of mutant insulin (INS) gene-induced diabetes of youth (MIDY) (9–13). However, no studies have addressed earlier defects at the point of entry of preproinsulin into the ER. Recently, two preproinsulin SP mutants, preproinsulin R6C and R6H (here simply called R6C or R6H) have been linked to autosomal dominant late-onset diabetes in humans (14–16). The molecular mechanism by which these mutants bring about diabetes has been speculated to involve ER stress (14), but the actual defect has remained unknown.

Like other secretory proteins targeted to the ER lumen, preproinsulin SP has three distinct regions: a positively charged “n region,” a central hydrophobic “h region,” and a “c region” containing the signal peptidase cleavage site. Mutations R6C and R6H eliminate the highly conserved n region positive charge, which forms the basis for the “positive-inside” rule that is thought to facilitate SP orientation at the ER membrane during membrane protein translocation (17–19). Nevertheless, to date, no human disease has been shown to be caused by a loss of the n region positive charge. Indeed, a recent study reported that neither R6C nor R6H results in defective insulin granule targeting of a preproinsulin-GFP chimera, thus leaving the diabetes linked to these mutations largely unexplained (14).

Here we demonstrate that, upon targeting to the ER membrane, preproinsulin R6C and R6H fail to be fully translocated across the ER membrane. The newly synthesized untranslocated preproinsulin remains strongly associated with the ER membrane, exposing its proinsulin moiety to the cytosol. Untranslocated preproinsulin accumulates in a juxtanuclear cytoplasmic compartment distinct from the Golgi complex, induces the expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), and leads to β cell death. Restoring the N-terminal positive charge of mutant preproinsulin SP significantly improves the translocation defect. This study reveals a novel mechanism leading to β cell failure and diabetes and highlights the pathological consequences of loss of the SP n region positive charge of secretory proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Guinea pig anti-porcine insulin antibody and the human insulin-specific RIA kit (catalog no. HI-14 K) was from Millipore. Rabbit anti-Myc and anti-GFP antibodies were from Immunology Consultant Laboratories. Anti-GM130 antibody was from BD Biosciences. Anti-calnexin antibody was from Enzo Life Sciences. Zysorbin was from Zymed Laboratories Inc.. 35S-amino acid mixture (Met + Cys) and pure [35S]Met were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. DTT, protein A-agarose, digitonin, N-ethylmaleimide, brefeldin A, and MG132 were from Sigma-Aldrich. Peptide-N-glycosidase F (PNGaseF) was from New England Biolabs. 4–12% NuPage gel, Met/Cys-deficient DMEM, and all other tissue culture reagents were from Invitrogen. The INS1 r9 cells were from Dr. Claes B. Wollhein (University of Geneva, Switzerland).

Human Islet Study

Institutional review board approval for research use of isolated human islets was obtained from the University of Michigan. Human islets were isolated from previously healthy, nondiabetic organ donors by the University of Chicago Transplant Center. Three independent human islet batches from two male donors aged 20 and 58 and one female donor aged 48 were used in this study. The islets were divided into two groups incubated in CMRL medium (Invitrogen) containing either 5.5 or 25.5 mm glucose for 20 h before metabolic radiolabeling with either [35S]Met/Cys mixtures or pure [35S]Met, as indicated, for 10 min. Normalized by DNA, the islet lysates were immunoprecipitated using anti-insulin and analyzed as indicated in the figure legends.

Mutagenesis, Cell Culture, Transfection, Metabolic Labeling, and Immunoprecipitation

Human and mouse preproinsulin mutants were generated using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent). INS1 rat β cells, Min6 mouse β cells, or 293T human embryonic kidney cells were plated onto 12-well plates 1 day before transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) using 1–2 μg of plasmid DNA. 48 h after transfection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]Met/Cys or pure [35S]Met with or without chase as indicated. Cells used for analysis of (pre)proinsulin oxidative folding were preincubated with 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide in PBS on ice for 10 min before lysis. Immunoprecipitation and non-reducing or reducing Tris-Tricine urea SDS-PAGE analyses were performed as described previously (5, 13). For Western blotting, 20 μg of total protein lysates was boiled in SDS sample buffer with or without 100 mm DTT, resolved by 4–12% NuPage, electrotransferred to nitrocellulose, and blotted with appropriate first antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP, with development by enhanced chemiluminescence. The BiP promoter-driven firefly luciferase assay for Min6 cells was performed as described previously (9).

In Vitro Targeting and Translocation Study

The cotranslational protein targeting and translocation assay has been described previously in detail (20, 21). Briefly, wheat germ translation extract, free of endogenous SRP and SRP receptor, was used to synthesize WT and mutant preproinsulin in the presence of [35S]Met (for the in vitro assay, methionine residues were added to the C terminus of preproinsulin). To best mimic a single round of cotranslational protein targeting, a cap analog, 7-methyl-GTP, was added 1–2 min after translation initiation to inhibit additional rounds of synthesis. Purified SRP, SRP receptor, and ER microsomal membranes in which the endogenous SRP and SRP receptor had been removed by high-salt wash and partial trypsin digestion were then added within 1 min. Translation was continued for 20–30 min at 26 °C to allow completion of preproinsulin synthesis, at which point the reactions were stopped and analyzed. The targeting and translocation efficiency was assessed by two approaches (cleavage of the signal sequence and protection of proinsulin from proteinase K digestion) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The localization of preproinsulin and proinsulin was assessed using a sedimentation assay. The targeting and translocation reactions were carried out as described in the previous paragraph. A 30-μl reaction mixture was layered onto a 50-μl cushion of 0.5 m sucrose and ultracentrifuged at 55,000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min (TLA100, Beckman Coulter). The supernatant was TCA-precipitated. This and the microsomal pellet were dissolved and analyzed on SDS-PAGE.

Selective Plasma Membrane Permeabilization by Digitonin, Proteinase K Digestion, and Sodium Carbonate Extraction

For the ER targeting experiments, after labeling with [35S]Cys/Met, the plasma membranes of 293T cells transfected with preproinsulin WT or mutants were partially permeabilized with 0.01% digitonin as described previously (13). For proteinase K (PK) digestion, 2 days after transfection, 293T cells expressing Myc-tagged R6C or A24D were incubated on ice with either PBS only, PBS plus 0.01% digitonin and 10 μg/ml PK, or PBS plus 1% Triton X-100 and 10 μg/ml PK for 30 min. 2 μm PMSF and SDS sample buffer were added, boiled, and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Myc antibody. For sodium carbonate extraction, after pulse-labeling with [35S]Met/Cys, transfected cells were suspended in 0.1 m sodium carbonate (pH 12), homogenized, and incubated on ice for 1 h, followed by sedimentation at 50,000 rpm at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatants and pellets were collected and immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc, anti-calnexin, and anti-PDI antibodies.

Generation of Inducible β Cell Lines Expressing Mouse Ins2 Wild-type, R6C, and A24D; Cell Proliferation; and Cell Death Assay

The INS-r9 cells carrying the reverse tetracycline/doxycycline-dependent transactivator (22) were cotransfected with a puromycin resistance plasmid and pTRE plasmids encoding Myc-tagged mouse Ins2 WT, R6C, or A24D. Puromycin-resistant clones were isolated and tested for the expression of Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT or R6C by both pulse labeling and Western blotting after induction with 2 μg/ml doxycycline (Dox). For determining cell proliferation, 3000 cells of inducible clones were seeded into 96-well plates and incubated with or without 2 μg/ml Dox for 4 days. BrdU incorporation was measured using a BrdU cell proliferation kit (Millipore). For examining cell death, the cells of inducible clones were seeded into 8-well chamber slides (LabTek) and incubated with or without 2 μg/ml Dox for 4 days. Cell apoptosis was measured by labeling DNA strand breaks (TUNEL) using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche) with DAPI counterstaining to identify the nuclei. A total of more than 4500 cells expressing the wild type or R6C were counted from three independent experiments.

Confocal Imaging

INS1-inducible cell lines expressing mouse preproinsulin WT, R6C, and A24D were induced with 2 μg/ml Dox for 4 days. The cells were preincubated with 5 μg/ml cycloheximide for 1 h, followed by either permeabilization with 0.01% digitonin on ice for 3 min (selectively permeabilizing the plasma membrane) or with 0.5% Triton X-100 (fully permeabilizing all membranes), as indicated. The cells were then fixed with formaldehyde, blocked, and stained with anti-Myc, anti-PDI (an ER marker), and anti-GM130 (a Golgi marker), followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores, and imaged by epifluorescence in an Olympus FV500 confocal microscope with a ×60 oil objective. For disrupting the Golgi structure (23), the cells were pretreated with 5 μm brefeldin A for 30 min before permeabilization with 0.01% digitonin for 3 min.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out by analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism 6. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

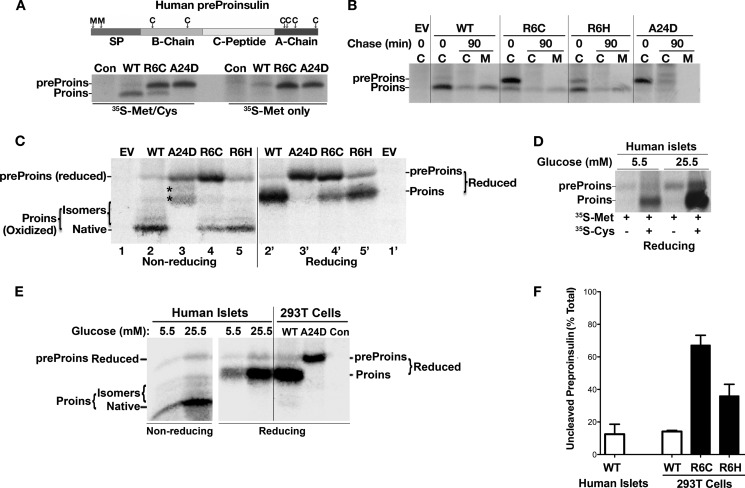

R6C/R6H Causes Early Defects in Preproinsulin to Proinsulin Conversion

We developed a method that could specifically distinguish processed and unprocessed human preproinsulin (13). Because human preproinsulin has two methionines in the SP and six cysteines in the proinsulin moiety (Fig. 1A, top panel), pure [35S]Met labels exclusively unprocessed preproinsulin, whereas a [35S]Met/Cys mixture labels both preproinsulin and proinsulin. Using this method, we first examined the processing of preproinsulin to proinsulin of newly synthesized preproinsulin WT and mutants in transfected 293T cells. Compared with the WT, R6C exhibited significantly more unprocessed preproinsulin labeled by [35S]Met (Fig. 1A, bottom panel; preproinsulin-A24D, which is defective in SP cleavage, serves as a positive control of uncleaved preproinsulin (13)). After a 90-min chase, although the modest fraction of proinsulin derived from R6C was secreted with normal efficiency, unprocessed preproinsulin R6C largely disappeared without conversion to proinsulin (Fig. 1B). The defect of R6H was similar to that of R6C but less severe.

FIGURE 1.

The early events of insulin biosynthesis and defects in processing of preproinsulin to proinsulin caused by R6C or R6H. A, human preproinsulin has two methionines in its SP and six cysteines in its proinsulin moiety (top panel). 293T cells transfected with plasmids encoding preproinsulin WT or mutants were labeled with either [35S]Met/Cys or [35S]Met for 10 min. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin and analyzed using NuPage under reducing conditions. Pure [35S]Met labels only unprocessed human preproinsulin (preProins), whereas [35S]Met/Cys labels both human preproinsulin and proinsulin (Proins). Con, control. B, 293T cells transfected with empty vector (EV) or plasmids encoding preproinsulin WT or mutants were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 10 min followed by 0- or 90-min chase. Cell lysates (C) and chase media (M) were analyzed as in A. C, the newly synthesized preproinsulin WT and mutants from transfected 293T cells were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 10 min, immunoprecipitated, and analyzed using Tris-Tricine urea SDS-PAGE under non-reducing and reducing conditions. The asterisk denotes oxidized uncleaved A24D. D, human islets preincubated with 5.5 or 25.5 mm glucose for 20 h were labeled with either [35S]Met/Cys or [35S]Met for 10 min. The islet lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin and analyzed as in A. E, parallel groups of human islets of D were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 10 min, lysed, immunoprecipitated, and analyzed as C. Newly synthesized A24D from transfected 293T cells were used as a molecular weight control of uncleaved preproinsulin. F, quantification data of uncleaved preproinsulin in human islets and transfected 293T cells from at least three independent experiments shown in A–E.

To examine whether unprocessed R6C and R6H were exposed to the ER lumen, we analyzed newly synthesized preproinsulin using Tris-Tricine urea SDS-PAGE under both non-reducing and reducing conditions. Unlike proinsulin and uncleaved A24D, which underwent oxidative folding in the ER lumen (13), unprocessed R6C and R6H remained as fully reduced forms (Fig. 1C), suggesting that their proinsulin moiety is not exposed to the oxidizing environment of the ER lumen.

Because a small fraction of unprocessed preproinsulin WT was observed in transfected 293T cells (Fig. 1, A–C and F), we decided to evaluate the translocation/processing efficiency of wild-type preproinsulin in primary β cells. After 10 min of labeling of isolated human pancreatic islets, ∼10% of the specific immunoprecipitable product remained as unprocessed preproinsulin, as demonstrated by specific labeling of this band with pure [35S]Met (Fig. 1D), by comigration of this band on SDS-PAGE with SP cleavage-defective A24D (Fig. 1E), and by its enhanced intensity upon stimulation with high glucose (Fig. 1, D–E). Unprocessed preproinsulin WT was reduced fully (Fig. 1E), suggesting that, in normal human islets, some fully translated preproinsulin molecules are present in the cytosol prior to entry into the oxidizing environment of the ER lumen.

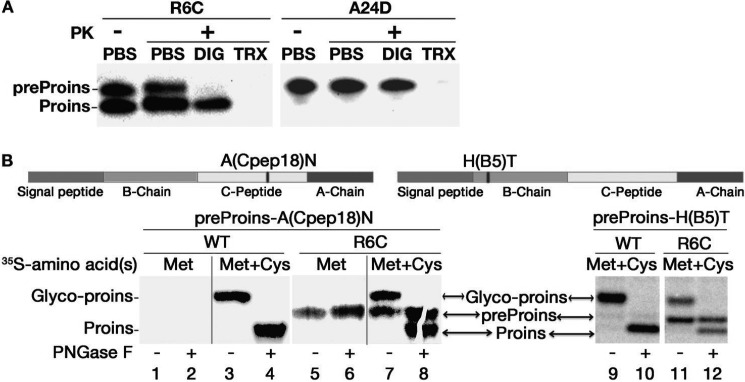

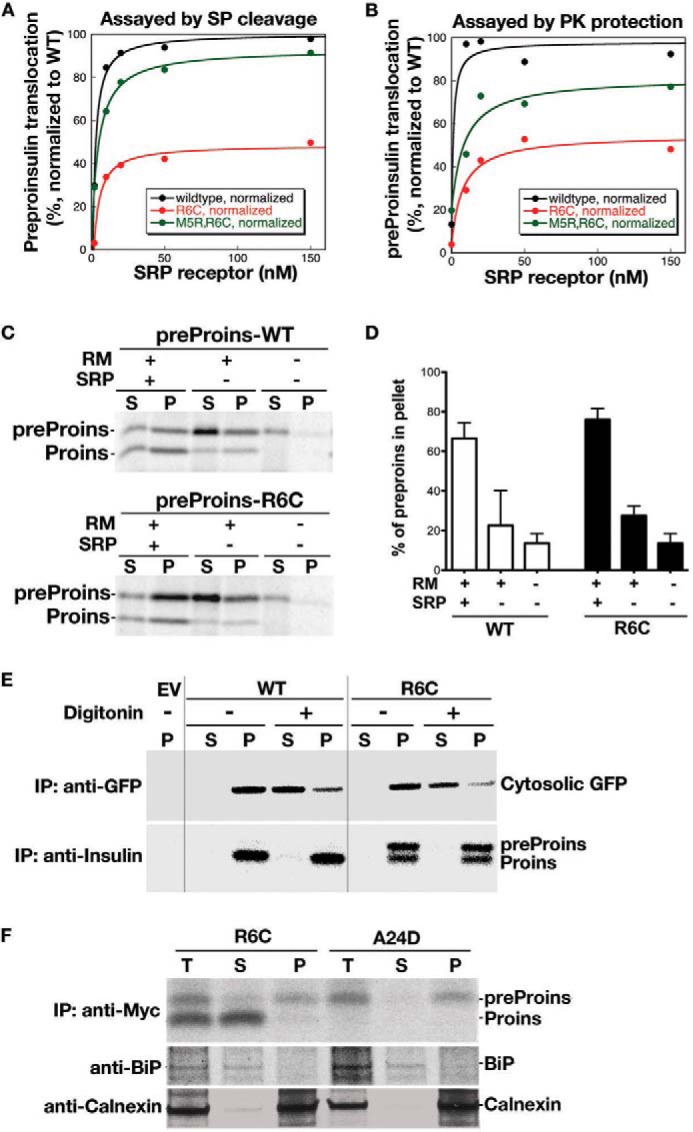

R6C Is Targeted to and Strongly Associated with the ER Membrane but Exhibits Impaired Polypeptide Translocation

Mutations of Arg-6 eliminate a highly conserved n region positive charge, which is generally thought to be important for the targeting and translocation of secretory and membrane proteins (18, 24–27). To determine whether R6C affects these early steps during insulin biosynthesis, we first tested the SRP-dependent targeting and translocation of WT and mutant preproinsulins into ER microsomal membranes in a reconstituted in vitro assay (20). Analysis of the reaction on the basis of both SP cleavage (Fig. 2A) and sensitivity to PK digestion (Fig. 2B) demonstrated that R6C mutation caused a 2-fold reduction in the efficiency of targeting and translocation of preproinsulin.

FIGURE 2.

Preproinsulin R6C and R6H are targeted to and strongly associated with the ER membrane but exhibit impaired translocation. A and B, effect of R6C on SRP-dependent protein targeting and translocation in vitro. Preproinsulin WT and mutants were synthesized by in vitro translation in the presence of [35S]Met. The ability of exogenously added SRP and SRP receptor to target preproinsulins to salt-washed and trypsin-digested ER microsomes (TKRM) was assayed by cleavage of the SP upon successful translocation (A) and by protection of the translocated protein from PK digestion (B), as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The translocation efficiency of the mutant proteins was normalized to that of preproinsulin WT, whose translocation at saturating SRP receptor concentration was set to be 100%. C, preproinsulin (preProins) R6C is targeted to the microsomes in an SRP-dependent manner. In vitro synthesis, targeting, and translocation of preproinsulin WT and R6C were carried out as in A and B in the presence and absence of exogenously added SRP and rough microsomes (RM). The reactions were loaded on a 0.5 m sucrose cushion, and microsomal membranes were sedimented by ultracentrifugation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” S, supernatant; P, pellet; Proins, proinsulin. D, quantification of data from two independent experiments shown in C. E, 293T cells coexpressing preproinsulin WT or mutants with a separate CMV promoter-driven GFP expressed in the cytosol were labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 15 min and then incubated with or without 0.01% digitonin in PBS for 10 min to selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane. The cells transfected with empty vector (EV) served as controls. The membrane-bound and luminal proteins were sedimented at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. In digitonin-treated cells, although the majority of cytosolic GFP was liberated into supernatant, both cleaved and uncleaved preproinsulin remained in the pellet. IP, immunoprecipitation. F, 293T cells expressing preproinsulin R6C and A24D were labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 20 min and subjected to the carbonate extraction as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Although proinsulin derived from R6C was mostly recovered in the supernatant (S) along with BiP, the majority of uncleaved preproinsulin R6C and A24D remained in the membrane pellet (P) along with calnexin, suggesting that uncleaved preproinsulin mutants are strongly associated with the ER membrane. T, total lysate.

To uncouple the effects of targeting from translocation across the ER, we performed a sedimentation analysis to examine the localization of preproinsulin and proinsulin after the targeting/translocation reaction was completed. As expected, in the absence of SRP, only a small fraction of preproinsulin was associated with the microsomal membrane, and the presence of SRP significantly increased the amount of proinsulin molecules, which were primarily associated with the microsome. Unexpectedly, in the presence of SRP, the majority of preproinsulin R6C also became microsome-bound (Fig. 2, C and D). This suggests that R6C was targeted to the ER and that the mutation affected its translocation across the ER membrane.

To test this notion, we examined the localization of R6C in living cells. We coexpressed preproinsulin WT or R6C with a separate CMV promoter-driven GFP expressed in the cytosol of transfected 293T cells. The plasma membrane was selectively permeabilized with 0.01% digitonin, and cytosolic proteins were separated from organelle-bound proteins by centrifugation (13). Although most cytosolic GFP shifted to the supernatant in digitonin-treated cells, both uncleaved and cleaved R6C remained exclusively in the pellet (Fig. 2E), consistent with the results from in vitro assays (Fig. 2C). To examine the extent of membrane engagement of R6C, we employed a sodium carbonate wash, which separates luminal and peripheral membrane proteins from integral membrane proteins (28). As shown in Fig. 2F, processed proinsulin derived from R6C was fully extracted along with the ER luminal component BiP, whereas the majority of uncleaved preproinsulin R6C (or A24D) remained in the membrane fraction along with the ER membrane protein calnexin. These results provide strong evidence that the newly synthesized R6C was targeted to the ER membrane and became organelle-bound.

To examine the topology of R6C on the ER membrane, we performed PK digestion after permeabilization of the plasma membrane with digitonin (13). In digitonin-permeabilized cells (Fig. 3A, DIG), preproinsulin A24D (a mutant known to be translocated efficiently translocated (13)) was demonstrably resistant to PK digestion (Fig. 3A, right panel). By contrast, although proinsulin derived from R6C also resisted PK digestion in digitonin-permeabilized cells, unprocessed R6C was fully digested (Fig. 3A, left panel), indicating that unprocessed R6C was exposed on the cytosolic side of the ER membrane. Both R6C and A24D were fully digested when the ER membrane was permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 (Fig. 3A, TRX).

FIGURE 3.

The proinsulin moiety of preproinsulin R6C is exposed to the cytosol. A, 293T cells expressing Myc-tagged preproinsulin (preProins) R6C and A24D were subjected to PK digestion in the presence or absence of digitonin (DIG) or Triton X-100 (TRX), followed by anti-Myc Western blotting as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Unprocessed R6C was sensitive to PK digestion in partially permeabilized cells, indicating that its proinsulin (Proins) moiety was exposed to the cytosol. B, two engineered human preproinsulins with N-linked glycosylation sites were created, as indicated in the top panel. The newly synthesized preproinsulin WT and R6C labeled with either [35S]Met or [35S]Cys/Met were treated with or without PNGaseF before SDS-PAGE. Although proinsulin derived from WT or R6C was glycosylated (glyco-proins, lanes 3, 7, 9, and 11), unprocessed R6C labeled by pure [35S]Met (lanes 5 and 6) failed to acquire an N-linked glycan, indicating that unprocessed R6C was not delivered to the ER lumen.

To independently monitor the translocation of preproinsulin into the ER lumen, we engineered two preproinsulins with potential N-linked glycosylation sites located either at residue 18 of the C peptide (Fig. 3B, top panel, A(Cpep18)N) or at residue 5 of the insulin B chain (Fig. 3B, top panel, H(B5)T). Exploiting the fact that pure [35S]Met labels preproinsulin but not proinsulin (Fig. 1A), we found that proinsulin derived from R6C became glycosylated (confirmed by deglycosylation with peptide-N-glycosidase F), whereas preproinsulin R6C did not acquire an N-linked glycan at either site (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6). Thus, translocation of uncleaved R6C was not even delivered to the ER lumen 3–5 residues beyond the end of the SP.

Together, these data establish that, although preproinsulin-R6C is targeted to the ER, it exhibits impaired polypeptide translocation across the ER membrane. Untranslocated R6C remains strongly associated with the ER membranes with its proinsulin moiety exposed to the cytosol. This is distinct from the previously characterized preproinsulin-A24D mutant, which is translocated into the ER lumen and induced ER stress (12, 13).

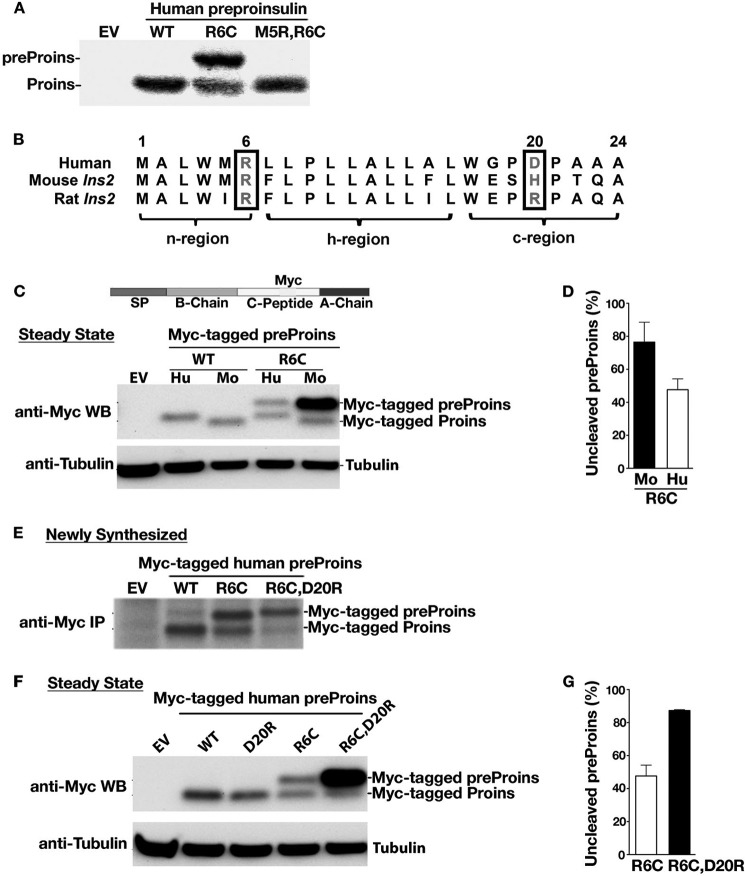

The Positive Charge in the N Region and Charge Gradient Flanking the H Region of the SP Play a Critical Role in Efficient Targeting and Translocation of Preproinsulin

Mutations R6C and R6H remove the highly conserved n region positive charge. To determine the importance of basic residues in the SP n region for mediating targeting and translocation of preproinsulin, we introduced Arg at position 5 to create a M5R/R6C double mutant, thereby restoring a positive charge to the n region. This significantly improved translocation efficiency of R6C, both in transfected 293T cells (Fig. 4A) and in the reconstituted in vitro targeting and translocation assay (Figs. 2, A and B).

FIGURE 4.

The positive charge in the n region and the charge gradient flanking the h region of the SP play a critical role in the efficient targeting and translocation of preproinsulin. A, 293T cells transfected with empty vector (EV), human preproinsulin (preProins) WT, R6C, or M5R/R6C were labeled with [35S]Cys/Met for 15 min and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Proins, proinsulin. B, the homology of human and rodent insulin gene 2 (Ins2) preproinsulin signal sequences. C, INS1 cells expressing Myc-tagged human (Hu) preproinsulin WT or R6C or mouse (Mo) Ins2 WT or R6C were examined by anti-Myc Western blotting (WB). Mouse Ins2 R6C shows a more severe translocation defect than human R6C. D, quantification data of uncleaved preproinsulin from at least three independent experiments shown in C. E, INS1 cells expressing Myc-tagged human preproinsulin WT or mutants were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 10 min. The newly synthesized preproinsulin was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Myc, followed by SDS-PAGE. F, Myc-tagged human preproinsulin WT or mutants in transfected INS1 cells were examined by anti-Myc Western blotting. R6C/D20R significantly exacerbated the defect of R6C. G, quantification data of uncleaved preproinsulin from at least three independent experiments shown in F.

In general, a positive charge in the SP n region helps to orient the signal sequence during translocation, with the n region on the cytosolic side of the ER membrane and the c region of SP toward the lumen (positive-inside rule) (27, 29). Although the preproinsulin residue Arg-6 is highly conserved, we noted that a negative charge in the c region of human preproinsulin (residue 20) is not conserved in rodents (Fig. 4B). Indeed, although human and mouse wild-type preproinsulin were fully cleaved at a steady state (Fig. 4C), the R6C mutation in mouse preproinsulin exerted an even more deleterious effect on the processing of preproinsulin in INS1 cells (Fig. 4, C and D; the Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT and R6C (Fig. 4C, top panel) allowed us to examine translocation defects of R6C in β cells). Reciprocally, we created a double mutant, R6C/D20R, in which the charge gradient flanking the h region of the human preproinsulin signal sequence was reversed. R6C/D20R exhibited dramatically reduced translocation by both pulse labeling (Fig. 4E) and steady-state measurements (Fig. 4, F and G). Together, these data indicate that the charge gradient flanking the h region of the signal sequence plays a critical role in the translocation of preproinsulin.

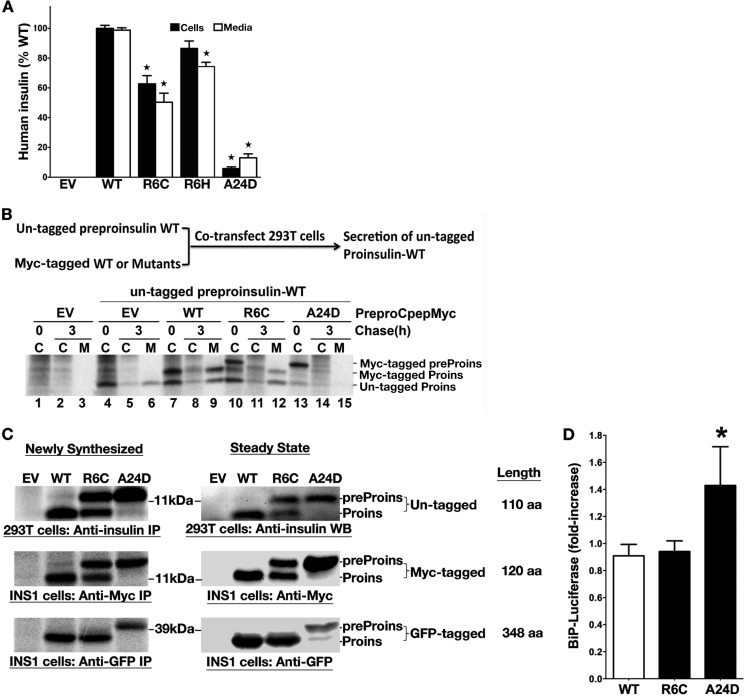

R6C Does Not Affect Coexpressed Preproinsulin WT nor Induce ER Stress

We examined insulin production derived from these mutants in INS1 (rat) β cells using a human-specific insulin radioimmunoassay (13, 30). INS1 cells transfected with human preproinsulin R6C produced and secreted about half as much human insulin as the WT (Fig. 5A), consistent with the results above (Figs. 1–4) showing that ∼50% of R6C molecules are translocated into the ER. However, this partial defect alone is insufficient to account for insulin-deficient diabetes (31). Given that R6C and R6H are associated with autosomal dominant diabetes (14–16), it was important to know whether these mutants behave like those causing the syndrome of MIDY, which exert dominant-negative effects on the folding/stability and trafficking of coexpressed proinsulin WT (9, 13, 30). To test this, we coexpressed untagged preproinsulin WT with either Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT, R6C, or A24D. We found that, unlike Myc-tagged A24D (which blocks the secretion of coexpressed proinsulin WT, Fig. 5B, lanes 13–15), Myc-tagged R6C did not inhibit the expression, translocation, or processing of coexpressed untagged preproinsulin WT (Fig. 5B, lanes 10–12). Thus, Arg-6 mutants behave very differently from MIDY mutants described previously (9, 10).

FIGURE 5.

R6C and R6H fail to produce a normal amount of insulin but do not affect coexpressed preproinsulin WT nor induce ER stress. A, INS1 cells were transfected with empty vector (EV), human preproinsulin WT or mutants. At 48 h post-transfection, the human insulin in the lysates (black bars) and media (white bars) were measured using human insulin-specific RIA normalized to human insulin mRNA. Results shown are mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with preproinsulin WT. B, 293T cells were cotransfected with untagged preproinsulin (preProins) WT, with empty vector (EV), or Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT, or mutants. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were labeled for 15 min, followed by a 0- or 3-h chase. Cell lysates (C) and chase media (M) were immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin and analyzed under reducing conditions. Unlike A24D, which blocked the secretion of coexpressed WT, R6C did not affect the expression, translocation, and secretion of coexpressed WT. Proins, proinsulin. C, the plasmids encoding human preproinsulin WT, R6C, or A24D with or without a Myc or GFP tag was transfected into 293T or INS1 cells as indicated. The cells transfected with empty vector (EV) served as controls. After 48 h post-transfection, the expression and SP cleavage of untagged or tagged preproinsulin were examined and compared by pulse labeling (newly synthesized) and Western blotting (steady state) using anti-insulin, anti-Myc, or anti-GFP antibodies, as indicated. Unlike untagged and Myc-tagged preproinsulin R6C, there was no detectable defect in GFP-tagged R6C. IP, immunoprecipitation; aa, amino acids. D, BiP promoter activities in transfected pancreatic β cells were evaluated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cells expressing preproinsulin WT were served as a control. Results were expressed as mean ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with preproinsulin WT.

Using GFP-tagged preproinsulin constructs, a recent study reported no defect of R6C/R6H in the targeting of preproinsulin to insulin granules but suggested that ER stress might contribute to β cell death and diabetes in patients carrying these mutations (14). Importantly, fusion with GFP (238 amino acids) triples the length of preproinsulin (110 amino acids) that may alter (increase) translocation efficiency (32–34). Therefore, we compared the translocation efficiency of R6C with either a GFP tag or a Myc tag in the C peptide. In both pulse labeling and Western blotting experiments, although Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT, A24D, and R6C all appeared identical to their untagged counterparts (Fig. 5C, top and center panels), GFP-tagged R6C showed no detectable translocation defect (Fig. 5C, bottom panel, with A24D serving as a positive control for the mobility of the uncleaved precursor). Next, we examined the ER stress response in INS1 cells expressing Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT, R6C, or A24D using a BiP promoter-driven luciferase reporter (9). We found that, unlike A24D, R6C did not induce an activation of the BiP promoter (Fig. 5D). Together, these data suggest that larger secretory polypeptides may be insensitive to the effects of the R6C mutation. Thus, GFP-tagging may confound studies of the translocation of small secretory proteins.

Untranslocated Preproinsulin Accumulates in a Juxtanuclear Compartment, Induces HSP70 Expression, and Promotes β Cell Death

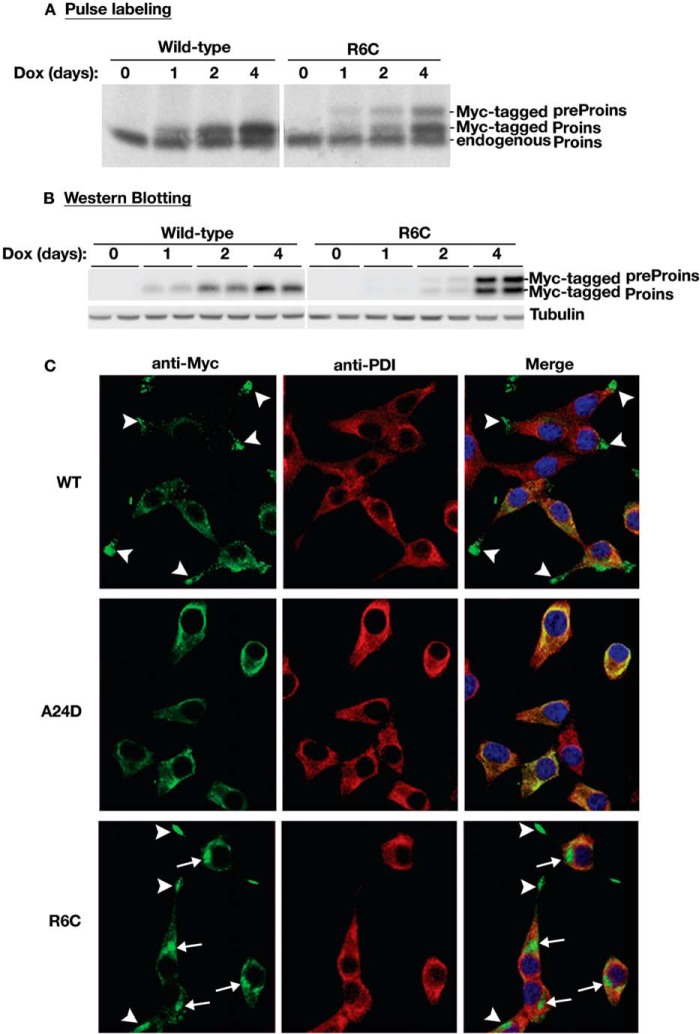

To understand the pathological consequences of the translocation defects of R6C, using INS-r9 cells carrying the reverse doxycycline-dependent transactivator (22), we established β cell lines in which expression of Myc-tagged mouse preproinsulin WT, R6C, or A24D was induced in the presence of doxycycline. The Myc epitope tag in the C peptide allowed for unequivocal distinction of these constructs from endogenous preproinsulin and proinsulin (13). Pulse labeling and Western blotting experiments showed that these cell lines exhibited comparable levels of induced expression of WT and R6C (Fig. 6, A and B). We then examined the localization of Myc-tagged mouse preproinsulin WT and mutants in these cell lines by immunofluorescence. Cells were pretreated with cycloheximide to minimize the contribution of newly synthesized molecules. Expression of preproinsulin WT led to an insulin granule-like pattern that was mostly concentrated in the distal tips of cellular processes (arrowheads), distinct from the ER marker PDI (Fig. 6C, top row). By contrast, expression of A24D led to a localization pattern that largely overlapped with PDI (Fig. 6C, center row). Interestingly, in addition to weak ER staining, two major intracellular pools accumulated for R6C: one concentrated normally in granules at the distal tips of cellular processes (Fig. 6C, arrowheads), whereas another concentrated abnormally as punctate structures at a juxtanuclear location (Fig. 6C, arrows). Neither structure overlapped with PDI (Fig. 6C, bottom row).

FIGURE 6.

Untranslocated R6C accumulates in a juxtanuclear region in pancreatic β cells. A, INS1 cells inducibly expressing Myc-tagged mouse preproinsulin (preProins) WT or mutants were established as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After Dox induction for the indicated days, the newly synthesized endogenous proinsulin (Proins), Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT, and R6C of inducible cell lines were labeled with [35S]Met/Cys for 15 min, immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin, and analyzed under reducing conditions. B, the steady state of Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT and R6C from the same sets of cells as in A was detected by anti-Myc Western blotting. C, after 4 days of Dox induction, INS1-inducible cell lines expressing Myc-tagged mouse preproinsulin WT, R6C, or A24D were pretreated with cycloheximide for 1 h before being fully permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 and immunostained with anti-Myc (green) and anti-PDI (an ER marker, red) antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. In most cells expressing Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT (top row), anti-Myc immunoreactable molecules presented as a punctate, insulin granule-like pattern (arrowheads) that was distinct from PDI. For R6C (bottom row), two major intracellular pools were observed. One did indeed concentrate in distal tips (arrowheads), whereas another accumulated in a juxtanuclear region (arrows), and neither pool overlapped with PDI. A24D lost the granule pattern and largely overlapped with PDI.

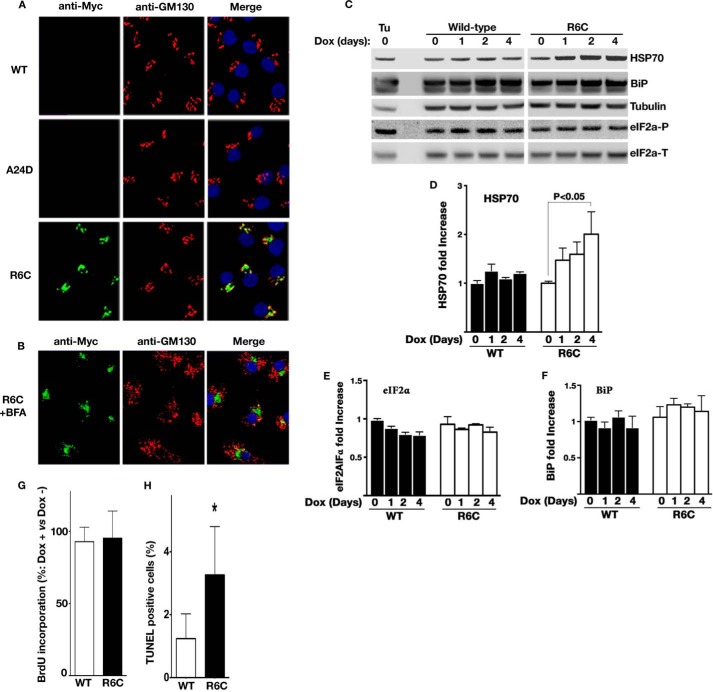

To further explore the juxtanuclear accumulation, parallel wells of the inducible cells used in Fig. 6C were partially permeabilized with 0.01% digitonin, fixed, and processed for anti-GM130 (a Golgi marker) and anti-Myc immunofluorescence (Fig. 7A). In partially permeabilized cells, anti-Myc immunofluorescence was detected only for R6C in a region near the Golgi complex (Fig. 7A, bottom row), suggesting that the proinsulin moiety of untranslocated R6C was exposed in the cytosol. To examine whether R6C accumulates in the Golgi, we disrupted the Golgi structure using brefeldin A. The juxtanuclear accumulation persisted even after the Golgi architecture was disrupted (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that a large subpopulation of incompletely translocated R6C molecules relocates from the ER and accumulates in a novel cytoplasmic compartment, with its proinsulin moiety exposed to the cytosol.

FIGURE 7.

Intracellular accumulation of untranslocated R6C induces cytosolic stress and promotes β cell death. A, the plasma membranes of similar sets of INA1-inducible cell lines as in Fig. 6C were selectively permeabilized by 0.01% digitonin and immunoblotted with anti-Myc (green) and anti-GM130 (a Golgi marker, red) antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Unlike in Fig. 6C, anti-Myc immunoreactable molecules were detected only in the cells expressing Myc-tagged R6C, indicating that the proinsulin moiety of untranslocated R6C was exposed to the cytosol. Such molecules appeared to accumulate in a juxtanuclear region close to the Golgi marker GM130. B, parallel wells of the cells expressing Myc-tagged R6C as in A were pretreated with 5 μm brefeldin A (BFA) for 30 min to disrupt the Golgi structure before being partially permeabilized and immunoblotted as in A. The juxtanuclear accumulation persisted even after the Golgi architecture was disrupted by brefeldin A. C, the expression of HSP70, BiP, total eIF2a (eIF2a-T), and phosphorylated eIF2α (eIF2α-P) in INS1 inducible cell lines were examined by Western blotting after Dox induction the indicated days. The INS1 cells treated with 10 μm tunicamycin for 6 h served as controls. D–F, quantification data of HSP70, eIF2α-P, and BiP from two to four independent experiments shown C. G, BrdU incorporation of INS1-inducible cell lines after 4 days of Dox induction of Myc-tagged WT or R6C expression was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” H, cell death of the same sets of cells as in G was detected using TUNEL as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A total of ∼4500 cells expressing WT or R6C were counted from three independent experiments. The cells in parallel wells treated without Dox were used as controls. Results are shown as means + S.D. from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 compared with Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT.

Accumulation of juxtanuclear puncta has been observed upon induction of proteostasis stress in the cytosol (35, 36). Therefore, we asked whether accumulation of R6C analogously induces cellular responses and, if so, in which subcellular compartment. Consistent with Fig. 5D, markers of the ER-associated unfolded protein response, including BiP and eIF2α phosphorylation, were comparable between cells expressing preproinsulin WT and R6C (Fig. 7, C, E, and F). In contrast, expression of R6C induced enhanced expression of HSP70 (Fig. 7, C and D), indicating activation of a cytosolic response.

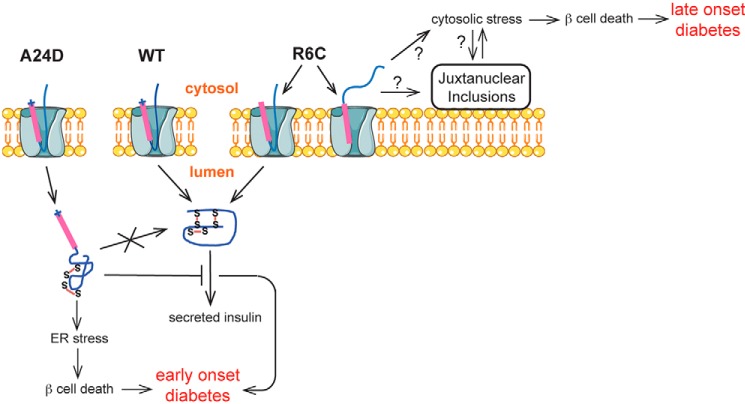

Because juxtanuclear accumulation of misfolded protein has been linked to cell death in neurodegenerative diseases (37, 38), we asked whether accumulation of preproinsulin R6C affects cell viability and proliferation. No appreciable change of BrdU incorporation was observed between cells expressing Myc-tagged preproinsulin WT and R6C (Fig. 7G), suggesting that R6C did not affect β cell proliferation. However, after a 4-day induction of preproinsulin expression, there was a significant increase of cell death in β cells expressing R6C (Fig. 7H). Together, the data indicate that incompletely translocated R6C accumulates in a juxtanuclear compartment, induces a cytosolic response, and promotes β cell death through mechanisms distinct from those reported previously for A24D and other MIDY mutants (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

A proposed model of β cell failure and diabetes caused by the defects in the earliest events of insulin biosynthesis. Two distinct underlying mechanisms associated with the defects occurring at the ER membrane can lead to β cell failure and diabetes. For preproinsulin A24D, impaired SP cleavage causes preproinsulin misfolding in the ER. Misfolded A24D not only induces ER stress but also blocks coexpressed proinsulin WT exit from the ER, causing a decrease of insulin production from proinsulin WT, leading to early-onset diabetes. For R6C, loss of the positive charge in the preproinsulin SP n region results in a misorientation of about 50% newly synthesized R6C molecules when their signal sequences interact with the Sec61 translocon. The misoriented R6C fails to be translocated into the ER lumen, accumulates in the cytosol and juxtanuclear compartment, induces cytosolic stress, and leads to β cell death and late-onset diabetes.

DISCUSSION

In pancreatic β cells, a multistep process lasting 30–150 min is needed to synthesize mature insulin (1, 39), yet the earliest events at the point of entry of preproinsulin into the ER remain understudied. Here we demonstrate that the SP n region positive charge plays an important role in ensuring efficient translocation of preproinsulin across the ER membrane and that inefficient preproinsulin translocation contributes to β cell failure and diabetes.

Unlike most MIDY patients developing early-onset diabetes, patients carrying the R6C and R6H SP mutations develop non-obese autosomal dominant diabetes between 15–65 years of age (14–16), suggesting that these mutants may cause diabetes via a distinct mechanism. In this report, we examined the biological behaviors of these two preproinsulin mutants. The evidence presented here strongly suggests that inefficient preproinsulin translocation is responsible for β cell failure in patients carrying these mutations. Although R6C and R6H mutations do not appear to affect SRP-dependent targeting to the ER (Fig. 2C), only a subpopulation of R6C molecules is translocated successfully into the ER lumen, as judged by processing to proinsulin (Figs. 1–3) or insulin (Fig. 5A), whereas the other major subpopulation remains as uncleaved preproinsulin. Uncleaved R6C does not access the oxidizing environment of the ER lumen (Fig. 1C), is sensitive to PK digestion in partially permeabilized cells (Fig. 3A), cannot deliver an acceptor sequence for luminal N-glycosylation (Fig. 3B), and can be detected by antibodies in the cytosol (Fig. 7, A and B). Thus, by multiple independent measures, we demonstrate that a major subpopulation of R6C is not translocated into the ER.

Upon arrival at the ER membrane, the SP interacts with the Sec61 translocon through which the SP (or signal anchor of membrane proteins) becomes properly oriented and processed in the membrane (40–42) according to the positive-inside rule (43, 44). We hypothesize that loss of the Arg-6 positive charge impairs the ability of the n region to orient the preproinsulin SP within the Sec61 translocon, resulting in misorientation of 50% of the molecules during translocation (Fig. 8). In support of this idea, restoring a positive charge to the SP n region significantly alleviates the translocation defect of R6C (Figs. 2, A and B, and 4A), whereas adding positive charge to the c region of R6C exacerbates the translocation defect (Fig. 4, C–G). In addition, under physiological pH, histidine is partially protonated, which may explain the difference in severity of the translocation defect of R6C and R6H (Fig. 1, B, C, and F). Together, these data strongly suggest that the charge gradient flanking the SP h region helps to guide the orientation of the preproinsulin signal sequence, thereby regulating the efficiency of preproinsulin translocation and insulin production.

Intriguingly, the importance of the n region positive charge in properly orienting the SP and mediating translocation appears to be dependent on the length of the substrate proteins. By comparing untagged and small Myc-tagged preproinsulin with GFP-tagged preproinsulin, we found that the defect caused by loss of the SP n region positive charge occurred only in Myc-tagged and untagged preproinsulin (Fig. 5C). Recently, several studies show that small secretory proteins constitute a great fraction of the proteome than previously estimated, and they may depend more on posttranslational mechanisms for efficient translocation (32–34, 45–47). Preproinsulin is a small secretory protein, so preproinsulin fused with GFP significantly increases the length of the polypeptide and may alter the translocation efficiency/pathway preproinsulin takes in cells. Therefore, GFP tagging is likely unsuitable for studying the translocation of preproinsulin. The dependence of other small secretory proteins on the SP n region positive charge for their efficient translocation remains to be determined.

It has been shown that insulin gene mutations causing low gene expression are recessive, rather than dominant, causes of diabetes (31). Therefore, for R6C or R6H, a 50% reduction in insulin production alone (Fig. 5A) cannot explain dominant diabetes in heterozygous patients. In the autosomal dominant syndrome of MIDY, mutant (pre)proinsulins such as preproinsulin A24D cause β cell failure and diabetes by abnormally interacting with coexpressed wild-type proinsulin in the ER, impairing folding and ER export of wild-type proinsulin, leading to insulin deficiency (9, 12, 13, 30), and triggering ER stress and early-onset diabetes (13, 48, 49). However, R6C and R6H cause late-onset diabetes, suggesting that they do not follow the MIDY model described previously. Indeed, our data indicate that, although newly synthesized uncleaved A24D and R6C are both targeted to and strongly associated with the ER membrane (Fig. 2), the proinsulin moiety for these two mutants is exposed on opposite sides of the ER membrane (Fig. 3A). Moreover, R6C does not affect the expression, translocation, or intracellular trafficking of coexpressed (pre)proinsulin WT (Fig. 5B).

Because defective R6C molecules do not enter the ER lumen (Figs. 1–3, 6C, and 7A), R6C does not induce appreciable ER stress (Figs. 5D and 7C). Instead, untranslocated R6C accumulates in a juxtanuclear compartment that is distinct from the Golgi complex in β cells (Figs. 6C and 7, A and B). Accumulation of juxtanuclear puncta has been observed upon expression of misfolding- and aggregation-prone proteins in the cytosol that induces cytoplasmic proteostasis stress (35, 36). Importantly, cytosolic/juxtanuclear accumulation of misfolded and/or mislocalized proteins has been linked to cell death that contributes to the development and progression of multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Huntington, Parkinson, Alzheimer, and prion disease (35, 37, 38, 50–55). Analogously, here we find that expression of R6C and its cytoplasmic/juxtanuclear accumulation strongly correlates with a cytosolic response and β cell death (Figs. 6 and 7). Thus, our findings establish a novel molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic β cell failure and diabetes distinct from mechanisms described previously (Fig. 8).

Integrating these findings, we speculate that inefficient translocation of preproinsulin might have implications for diabetes even in the absence of INS gene mutations. Certainly in neurons, inefficient translocation of the wild-type prion protein precursor can trigger neurodegeneration (52, 56–58). With this in mind, it is important to note that insulin biosynthesis alone accounts for more than 10% of total protein synthesis under basal condition in β cells. This percentage can further increase to 30–50% upon high glucose stimulation (59, 60), and up-regulated preproinsulin production can occur in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (61, 62). Given the fact that a small fraction of fully translated newly synthesized preproinsulin is present in the cytosol in normal human islets (Fig. 1, D–F) and that R6H with a less severe translocation defect can cause diabetes, there is the possibility that untranslocated preproinsulin WT can become a dangerous byproduct under certain pathological conditions. Studies are now needed to examine the efficiency of preproinsulin translocation in β cells in “garden variety” type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill and Dee Brehm for helping to establish the Brehm Center for Diabetes Research at the University of Michigan and Drs. Donald F. Steiner, Michael A. Weiss, Graeme Bell, and Yanzhuang Wang for encouragement and discussions. We also thank Dr. Martin Jendrisak and the entire team of the Gift of Hope Organ and Tissue Donor Network in Chicago for the human pancreas tissues used in this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-DK088856 (to M. L.), RO1-DK-48280 (to P. A.), RO1 GM078024 (to S. S.), and P60-DK-20572 (to the Molecular Biology and DNA Sequencing Core of the Diabetes Research and Training Center). This work was also supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Research Grant 81070629 (to M. L.), by a research grant from the March of Dimes Foundation (to M. L.), and by the Protein Folding Disease Initiatives of the University of Michigan. Human pancreatic islet processing was supported by Illinois Department of Public Health Grant “Pancreatic Islets Transplantation.”

- SP

- signal peptide

- SRP

- signal recognition particle

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- PK

- proteinase K

- BiP

- immunoglobulin-binding protein

- PDI

- protein disulfide isomerase

- Dox

- doxycycline

- MIDY

- mutant insulin (INS) gene-induced diabetes of youth.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dodson G, Steiner D. (1998) The role of assembly in insulin's biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patzelt C., Labrecque A. D., Duguid J. R., Carroll R. J., Keim P. S., Heinrikson R. L., Steiner D. F. (1978) Detection and kinetic behavior of preproinsulin in pancreatic islets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 1260–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolin S. L., Walter P. (1993) Discrete nascent chain lengths are required for the insertion of presecretory proteins into microsomal membranes. J. Cell Biol. 121, 1211–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Okun M. M., Shields D. (1992) Translocation of preproinsulin across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. The relationship between nascent polypeptide size and extent of signal recognition particle-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 11476–11482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu M., Li Y., Cavener D, Arvan P. (2005) Proinsulin disulfide maturation and misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13209–13212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang B. Y., Liu M., Arvan P. (2003) Behavior in the eukaryotic secretory pathway of insulin-containing fusion proteins and single-chain insulins bearing various B-chain mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3687–3693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu M., Ramos-Castañeda J., Arvan P. (2003) Role of the connecting peptide in insulin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14798–14805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang X. F., Arvan P. (1995) Intracellular transport of proinsulin in pancreatic β-cells. Structural maturation probed by disulfide accessibility. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20417–20423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu M., Haataja L., Wright J., Wickramasinghe N. P., Hua Q. X., Phillips N. F., Barbetti F., Weiss M. A., Arvan P. (2010) Mutant INS-gene induced diabetes of youth: proinsulin cysteine residues impose dominant-negative inhibition on wild-type proinsulin transport. PLoS ONE 5, e13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu M., Hodish I., Haataja L., Lara-Lemus R., Rajpal G., Wright J., Arvan P. (2010) Proinsulin misfolding and diabetes: mutant INS gene-induced diabetes of youth. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21, 652–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weiss M. A. (2013) Diabetes mellitus due to the toxic misfolding of proinsulin variants. FEBS Lett. 587, 1942–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park S.-Y., Ye H., Steiner D. F., Bell G. I. (2010) Mutant proinsulin proteins associated with neonatal diabetes are retained in the endoplasmic reticulum and not efficiently secreted. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1449–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu M., Lara-Lemus R., Shan S.-O., Wright J., Haataja L., Barbetti F., Guo H., Larkin D., Arvan P. (2012) Impaired cleavage of preproinsulin signal peptide linked to autosomal-dominant diabetes. Diabetes 61, 828–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meur G., Simon A., Harun N., Virally M., Dechaume A., Bonnefond A., Fetita S., Tarasov A. I., Guillausseau P. J., Boesgaard T. W., Pedersen O., Hansen T., Polak M., Gautier J. F., Froguel P., Rutter G. A., Vaxillaire M. (2010) Insulin gene mutations resulting in early-onset diabetes: marked differences in clinical presentation, metabolic status, and pathogenic effect through endoplasmic reticulum retention. Diabetes 59, 653–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boesgaard T. W., Pruhova S., Andersson E. A., Cinek O., Obermannova B., Lauenborg J., Damm P., Bergholdt R., Pociot F., Pisinger C., Barbetti F., Lebl J., Pedersen O., Hansen T. (2010) Further evidence that mutations in INS can be a rare cause of maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY). BMC Medical Genetics 11, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edghill E. L., Flanagan S. E., Patch A.-M., Boustred C., Parrish A., Shields B., Shepherd M. H., Hussain K., Kapoor R. R., Malecki M., MacDonald M. J., Støy J., Steiner D. F., Philipson L. H., Bell G. I., Neonatal Diabetes International Collaborative Group, Hattersley A. T., Ellard S. (2008) Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes. Diabetes 57, 1034–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peterson J. H., Woolhead C. A., Bernstein H. D. (2003) Basic amino acids in a distinct subset of signal peptides promote interaction with the signal recognition particle. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46155–46162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sasaki S., Matsuyama S., Mizushima S. (1990) In vitro kinetic analysis of the role of the positive charge at the amino-terminal region of signal peptides in translocation of secretory protein across the cytoplasmic membrane in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 4358–4363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iino T., Takahashi M., Sako T. (1987) Role of amino-terminal positive charge on signal peptide in staphylokinase export across the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 7412–7417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Powers T., Walter P. (1997) Co-translational protein targeting catalyzed by the Escherichia coli signal recognition particle and its receptor. EMBO J. 16, 4880–4886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shan S.-O., Chandrasekar S., Walter P. (2007) Conformational changes in the GTPase modules of the signal reception particle and its receptor drive initiation of protein translocation. J. Cell Biol. 178, 611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang H., Kouri G., Wollheim C. B. (2005) ER stress and SREBP-1 activation are implicated in β-cell glucolipotoxicity. J. Cell Sci. 118, 3905–3915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feng Y., Jadhav A. P., Rodighiero C., Fujinaga Y., Kirchhausen T., Lencer W. I. (2004) Retrograde transport of cholera toxin from the plasma membrane to the endoplasmic reticulum requires the trans-Golgi network but not the Golgi apparatus in Exo2-treated cells. EMBO Rep. 5, 596–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fujita H., Kida Y., Hagiwara M., Morimoto F., Sakaguchi M. (2010) Positive charges of translocating polypeptide chain retrieve an upstream marginal hydrophobic segment from the endoplasmic reticulum lumen to the translocon. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 2045–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parks G. D., Lamb R. A. (1991) Topology of eukaryotic type II membrane proteins: importance of N-terminal positively charged residues flanking the hydrophobic domain. Cell 64, 777–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goder V., Spiess M. (2001) Topogenesis of membrane proteins: determinants and dynamics. FEBS Lett. 504, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakaguchi M., Tomiyoshi R., Kuroiwa T., Mihara K., Omura T. (1992) Functions of signal and signal-anchor sequences are determined by the balance between the hydrophobic segment and the N-terminal charge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 16–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujiki Y., Hubbard A. L., Fowler S., Lazarow P. B. (1982) Isolation of intracellular membranes by means of sodium carbonate treatment: application to endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 93, 97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. von Heijne G. (1986) Net N-C charge imbalance may be important for signal sequence function in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 192, 287–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu M., Hodish I., Rhodes C. J., Arvan P. (2007) Proinsulin maturation, misfolding, and proteotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15841–15846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garin I., Edghill E. L., Akerman I., Rubio-Cabezas O., Rica I., Locke J. M., Maestro M. A., Alshaikh A., Bundak R., del Castillo G., Deeb A., Deiss D., Fernandez J. M., Godbole K., Hussain K., O'Connell M., Klupa T., Kolouskova S., Mohsin F., Perlman K., Sumnik Z., Rial J. M., Ugarte E., Vasanthi T., Neonatal Diabetes International Group, Johnstone K., Flanagan S. E., Martínez R., Castaño C., Patch A. M., Fernández-Rebollo E., Raile K., Morgan N., Harries L. W., Castaño L., Ellard S., Ferrer J., Perez de Nanclares G., Hattersley AT. (2010) Recessive mutations in the INS gene result in neonatal diabetes through reduced insulin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3105–3110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lakkaraju A. K., Thankappan R., Mary C., Garrison J. L., Taunton J., Strub K. (2012) Efficient secretion of small proteins in mammalian cells relies on Sec62-dependent posttranslational translocation. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 2712–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson N., Vilardi F., Lang S., Leznicki P., Zimmermann R., High S. (2012) TRC40 can deliver short secretory proteins to the Sec61 translocon. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3612–3620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shao S., Hegde R. S. (2011) A calmodulin-dependent translocation pathway for small secretory proteins. Cell 147, 1576–1588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaganovich D., Kopito R., Frydman J. (2008) Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature 454, 1088–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kocik L., Junne T., Spiess M. (2012) Orientation of internal signal-anchor sequences at the Sec61 translocon. J. Mol. Biol. 424, 368–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Debure L., Vayssiere J.-L., Rincheval V., Loison F., Le Drean Y., Michel D. (2003) Intracellular clusterin causes juxtanuclear aggregate formation and mitochondrial alteration. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3109–3121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viswanathan J., Haapasalo A., Böttcher C., Miettinen R., Kurkinen K. M., Lu A., Thomas A., Maynard C. J., Romano D., Hyman B. T., Berezovska O., Bertram L., Soininen H., Dantuma N. P., Tanzi R. E., Hiltunen M. (2011) Alzheimer's disease-associated ubiquilin-1 regulates presenilin-1 accumulation and aggresome formation. Traffic 12, 330–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alarcón C., Leahy J. L., Schuppin G. T., Rhodes C. J. (1995) Increased secretory demand rather than a defect in the proinsulin conversion mechanism causes hyperproinsulinemia in a glucose-infusion rat model of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Invest. 95, 1032–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pilon M., Römisch K., Quach D., Schekman R. (1998) Sec61p serves multiple roles in secretory precursor binding and translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3455–3473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plath K., Mothes W., Wilkinson B. M., Stirling C. J., Rapoport T. A. (1998) Signal sequence recognition in posttranslational protein transport across the yeast ER membrane. Cell 94, 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goder V., Junne T., Spiess M. (2004) Sec61p contributes to signal sequence orientation according to the positive-inside rule. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1470–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. von Heijne G., Gavel Y. (1988) Topogenic signals in integral membrane proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 174, 671–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Andersson H., von Heijne G. (1994) Membrane protein topology: effects of δ μ H+ on the translocation of charged residues explain the “positive inside” rule. EMBO J. 13, 2267–2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bionda T., Tillmann B., Simm S., Beilstein K., Ruprecht M., Schleiff E. (2010) Chloroplast import signals: the length requirement for translocation in vitro and in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 402, 510–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frith M. C., Forrest A. R., Nourbakhsh E., Pang K. C., Kai C., Kawai J., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Bailey T. L., Grimmond S. M. (2006) The abundance of short proteins in the mammalian proteome. PLoS Genet. 2, e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Johnson N., Powis K., High S. (2013) Post-translational translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2403–2409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Izumi T., Yokota-Hashimoto H., Zhao S., Wang J., Halban P. A., Takeuchi T. (2003) Dominant negative pathogenesis by mutant proinsulin in the Akita diabetic mouse. Diabetes 52, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oyadomari S., Koizumi A., Takeda K., Gotoh T., Akira S., Araki E., Mori M. (2002) Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 525–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schaffar G., Breuer P., Boteva R., Behrends C., Tzvetkov N., Strippel N., Sakahira H., Siegers K., Hayer-Hartl M., Hartl F. U. (2004) Cellular toxicity of polyglutamine expansion proteins: mechanism of transcription factor deactivation. Mol. Cell 15, 95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rubinsztein D. C. (2006) The roles of intracellular protein-degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature 443, 780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rane N. S., Chakrabarti O., Feigenbaum L., Hegde R. S. (2010) Signal sequence insufficiency contributes to neurodegeneration caused by transmembrane prion protein. J. Cell Biol. 188, 515–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miesbauer M., Rambold A. S., Winklhofer K. F., Tatzelt J. (2010) Targeting of the prion protein to the cytosol: mechanisms and consequences. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 12, 109–118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Strom A., Wang G.-S., Reimer R., Finegood D. T., Scott F. W. (2007) Pronounced cytosolic aggregation of cellular prion protein in pancreatic β-cells in response to hyperglycemia. Lab. Invest. 87, 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reiner T., Thurber G., Gaglia J., Vinegoni C., Liew C. W., Upadhyay R., Kohler R. H., Li L., Kulkarni R. N., Benoist C., Mathis D., Weissleder R. (2011) Accurate measurement of pancreatic islet β-cell mass using a second-generation fluorescent exendin-4 analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12815–12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rane N. S., Kang S.-W., Chakrabarti O., Feigenbaum L., Hegde R. S. (2008) Reduced translocation of nascent prion protein during ER stress contributes to neurodegeneration. Dev. Cell 15, 359–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hegde R. S., Ploegh H. L. (2010) Quality and quantity control at the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 437–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hegde R. S., Kang S.-W. (2008) The concept of translocational regulation. J. Cell Biol. 182, 225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schuit F. C., In't Veld P. A., Pipeleers D. G. (1988) Glucose stimulates proinsulin biosynthesis by a dose-dependent recruitment of pancreatic β cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3865–3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Scheuner D., Kaufman R. J. (2008) The unfolded protein response: a pathway that links insulin demand with β-cell failure and diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 29, 317–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tersey S. A., Nishiki Y., Templin A. T., Cabrera S. M., Stull N. D., Colvin S. C., Evans-Molina C., Rickus J. L., Maier B., Mirmira R. G. (2012) Islet B-cell endoplasmic reticulum stress precedes the onset of type 1 diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse model. Diabetes 61, 818–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kaufman R. J. (2011) β-Cell failure, stress, and type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1931–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]