Abstract

The mechanisms regulating the bilateral coordination of gait in humans are largely unknown. Our objective was to study how bilateral coordination changes as a result of gait speed modifications during over ground walking. 15 young adults wore force sensitive insoles that measured vertical forces used to determine the timing of the gait cycle events under three walking conditions (i.e., usual-walking, fast and slow). Ground reaction force impact (GRFI) associated with heel-strikes was also quantified, representing the potential contribution of sensory feedback to the regulation of gait. Gait asymmetry (GA) was quantified based on the differences between right and left swing times and the bilateral coordination of gait was assessed using the phase coordination index (PCI), a metric that quantifies the consistency and accuracy of the anti-phase stepping pattern. GA was preserved in the three different gait speeds. PCI was higher (reduced coordination) in the slow gait condition, compared to usual-walking (3.51% vs. 2.47%, respectively, p=0.002), but was not significantly affected in the fast condition. GRFI values were lower in the slow walking as compared to usual-walking and higher in the fast walking condition (p<0.001). Stepwise regression revealed that slowed gait related changes in PCI were not associated with the slowed gait related changes in GRFI. The present findings suggest that left-right anti-phase stepping is similar in normal and fast walking, but altered during slowed walking. This behavior might reflect a relative increase in attention resources required to regulate a slow gait speed, consistent with the possibility that cortical function and supraspinal input influences the bilateral coordination of gait.

Keywords: Bilateral coordination of gait, Gait asymmetry, Gait speed, Central pattern generator

Introduction

Healthy human gait is characterized by an anti-phased left-right stepping pattern. In mammals, reciprocal activation of central pattern generators (CPGs) on both sides of the spinal cord, reciprocally activated, are thought to maintain this pattern [1]. Along a straight path, the gait pattern is symmetric with respect to spatio-temporal parameters and muscle activation [2].

The effect of gait speed on the bilateral coordination of gait has primarily been studied using treadmill paradigms, focusing on the transition from walking to running (e.g., [3–6]. However, the effects of gait speed on left-right coordination were seldom explicitly addressed within the walking speed range [4] and only a few studies examined coordination during over ground walking [7]. Treadmill walking is more constrained and differs from over ground walking in several ways [8] and can therefore provide only limited understanding of functional walking. For example, the effect of conscious control over gait speed can not be evaluated during treadmill walking.

Therefore, we study here the effects of self-dictated fast and slow gait during over ground walking. Specifically, we apply the Phase Coordination Index (PCI) [9] to study the effects of gait speed on the coordination of the left-right stepping pattern. Since running improves intra and inter leg coordination, as compared to walking, we hypothesized that similar effects will be apparent at higher walking speeds during over ground walking. Surprisingly, we found no evidence to changes in bilateral function in higher walking speeds during over ground walking, however, bilateral coordination of gait was compromised during slow walking. We discuss several potential explanations for this finding including the potential role of supra spinal input, as well the potential role of afferent input [10].

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Fifteen young adults (8 women and 7 men) participated in the study. Mean values (± SD) of age, height and weight of the subjects were 26.3 ± 1.9 yrs, 1.70 ± 0.10 m and 66.7 ± 9.2 kg, respectively. Subjects were included if they reported that they were healthy and free of any clinically significant co-morbidities likely to affect gait, e.g., acute illness, diabetes mellitus, rheumatic or orthopedic diseases, dementia, depression, history of stroke, significant head trauma or brain surgery in the past. The experimental protocol was approved by the Human Studies Committee of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center. All the subjects provided informed written consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki prior to entering the study.

Gait protocol

The subjects wore force-sensitive insoles (Pedar-X, Novel, Germany) that use an array of capacitive sensors (99 in each insole) to measure the ground reaction forces under each foot at a sampling rate of 100Hz. Data were collected by a portable recording unit and then transferred to a computer for offline analysis. Prior to the experiment, the subjects were given an explanation of the protocol and were introduced to the walking area which consisted of a level 25 meter long and 2 meter wide corridor (the subjects walked back and forth along the corridor so that the total distance was larger; see below).

Each subject was instructed to start walking at her/his own preferred comfortable pace (usual-walking, baseline condition, BL1) for a distance of about 50 – 60 m. Then, while still walking, without a pause, the experimenter instructed the subject to “walk quickly” without any further specific instructions. After walking at a self-determined fast pace (fast walking) for about 50 – 60 m, the subject was instructed to return to regular walking (i.e., usual-walking-BL2) for about 50 – 60 m. Next, while still walking, the instruction was to “walk slowly” (slow walking, ~50 – 60 m), without any further specific instructions and then to resume baseline, usual-walking again, BL3 (~50 – 60 m).

The experiments were documented with video recordings that were synchronized with the gait analysis system. The instructions to move from one walking condition to another could clearly be heard and were used to determine the transitions between the various walking conditions.

Off line analysis of gait

For each leg, the time series of the force profile were analyzed by an algorithm that automatically detects the times of the ‘heel-strike’ and the ‘toe-off’ in each gait cycle, as previously described [11, 12]. In order to focus on the assessment of undisturbed continuous walking, the collected data were pre-processed and strides belonging to the 180° turns at the end of the corridor and the three strides in the transition period between walking conditions were excluded from the analysis. (These strides were identified from video recordings). After preprocessing, the following temporal gait parameters were determined:

Stride time

The time between two consecutive heel-strikes of the same leg. For each walking condition, the mean stride time was calculated for the left and right leg (L_str and R_str, respectively).

Swing time

The time lapse between toe-off and a consecutive heel-strike of the same leg. For each walking condition, the mean swing time was calculated for the left and right leg (L_SW and R_SW, respectively).

Gait speed

Average gait speed was determined using a stopwatch by measuring the average time the subject walked the middle fifteen meters of the walking path.

Ground reaction force impact (GRFI)

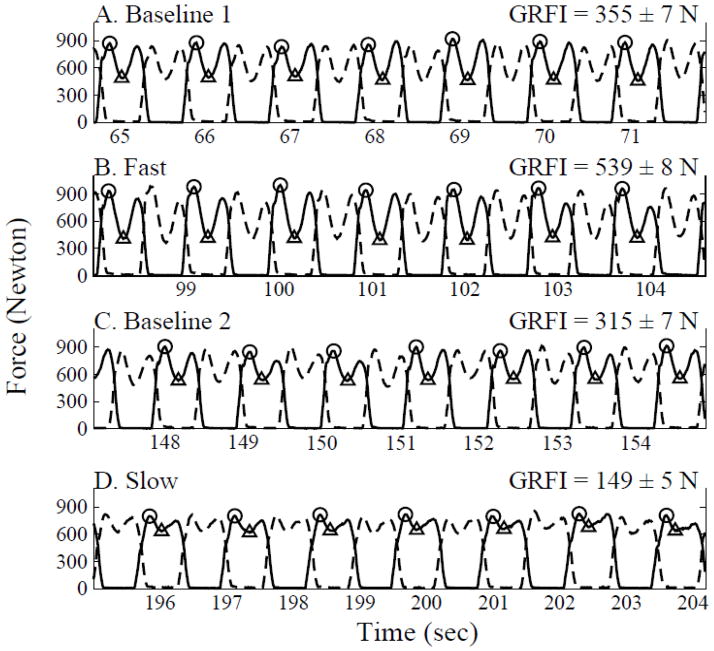

The impact sensed by the lower part of the feet whenever the heel strikes the floor was assessed from the ground reaction force profile as measured by the forces sensitive insoles (Figure 1). Peak pressure under the heel is sensitive to walking speed (e.g., [13–15]). We assume that GRFI can serve as an indication for the intensity of afferent sensorial feedback to the spinal cord from the legs while walking (see rationale in the Discussion).

Figure 1. Gait force profiles during different walking conditions.

Ground reaction force as measured by the force sensitive insoles is plotted against time for each leg (left- solid trace; right- dashed trace) from one subject in different walking conditions (Baseline 1 – BL1; fast walking- FW, baseline 2- BL2; slow walking- SW). Peak values related to heel-strike impact (circles) and mid stance force values (triangle) are indicated for each gait cycle (only 7 gait cycles were included for graphical clarity). GRFI values (see METHODS) are indicated to the right for these gait cycles.

An algorithm (MATLAB © software) which detects the local maxima (denoted by circles in Figure 1) and minima (denoted by triangles) within the force profile during the stance period (SP; duration when force>0) was used for each leg. For each step (i=1- n), the maximum –minimum difference (Δi) reflects the momentum torque (“impact”) related to heel-strike (i.e., as the minimum point occurs simultaneously with the swing period of the other leg, thus this leg bears the whole body weight). For each leg, the series of Δi are averaged (ΔL, ΔR), and single compound measure for each subject for each walking condition, GRFI, is calculated: GRFI= (ΔL + ΔR)/2.

We termed this measure the GRFI since it represents a change in force in a relatively short time period (between early stance and mid-stance) and therefore can be regarded as analogous to the definition of impact in classical bio-mechanics.

The following measures assessed bilateral function of gait:

1) Gait Asymmetry (GA)

Calculation of GA is performed according to the relationship:

This measure has been described in healthy subjects and in patients with PD [16, 17]. The natural logarithm was applied to take into account the skewed nature of the data GA values ≤ 20, are approximately equal to the percentile differences between R_SW and L_SW, and therefore were assigned precentile units.

2) Phase Coordination Index (PCI)

The coordination of left-right stepping was assessed using a recently described measure, i.e., PCI. A full description and derivation of the PCI metric is detailed elsewhere [15]. Briefly, PCI is a metric that combines the accuracy and consistency of stepping phases generation with respect to the value of 180°, which represents the ideal anti-phased left-right stepping. Lower PCI values reflect a more consistent and more accurate phase generation and related to different health conditions, while higher values indicate a more impaired bilateral coordination of gait [9, 18, 19].

Data handling and Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). A p-value of less than or equal to 0.05 (two sided) was considered statistically significant.

Preliminary analysis: homogeneity of the baseline-walking conditions

Before and after each walking condition, a usual-walking segment was evaluated and the pre- and post conditions were compared to the studied condition. To evaluate the consistency in the subjects preferred walking speed (i.e., between usual-walking conditions), we performed a repeated measures ANOVA (SPSS software) to determine if epoch had an effect on baseline speed values (i.e., the model had three within subject levels: BL1, BL2, BL3). The findings of these analyses suggest that gait speed during the three usual-walking conditions were not statistically significantly different (F2,13 = 0.221, p= 0.805) and were not influenced by the order of the usual-walking gait segments.

Relative changes in parameters

Relative changes in parameters during fast walking and slow walking with respect to usual-walking were calculated as the difference between the parameter value in the tested condition and its value in the preceding usual-walking condition (B1 for fast walking, and B2 for slow walking), divided by the parameter value in the usual-walking condition. The relative change was presented as a percentage.

Statistical analysis: the effect of walking conditions on gait parameters

General linear models (GLM) with repeated measures were applied for PCI and GA (separately) to test the effect of the two studied walking conditions (i.e., Fast, Slow). The model used to study the effect of fast walking had three conditions: BL1, fast walking and BL2. The model used to study the effect of slow walking had three conditions: BL2, slow walking and BL3. In one GLM, GA served as the dependent variable, and in the second GLM, PCI was the dependent variable. If significant effects were observed, post-hoc analyses were performed to contrast between the three conditions (within subject paired t test; Bonferroni corrected, k=2). We verified that the instructions to change gait speed were indeed followed using secondary analysis, utilizing the same GLM model to address the effect of the different walking conditions on gait speed. Correlation analyses that were used include Spearman and Pearson correlation analyses, and stepwise regression., as indicated. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

Results

Mean values of the PCI, GA, GRFI and gait speed in the different walking conditions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Group mean values (SE) of bilateral gait coordination parameters

| Parameter | Usual Walking* | Fast walking | Slow walking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gait Asymmetry | 1.26 (0.20) | 1.19 (0.14) | 1.90 (0.40) |

| Phase coordination index (%) | 2.52 (0.14) | 2.39 (0.14) | 3.51† (0.27) |

| Ground reaction force impact - GRFI (Newton) | 207† (19) | 389 (20) | 98† (13) |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.37† (0.03) | 1.70 (0.04) | 0.96† (0.04) |

Mean values across all three baseline walking conditions: BL1, BL2 and BL3.

Statistically significant effect of walking condition (p≤0.002) – see text for details on post hoc two way comparisons. Ranges of gait speeds can be seen in Figure 3

Effect of gait speed on bilateral function of gait

In comparison to the pre- and post- baseline walking condition, in the fast walking condition, gait speed was significantly increased (F2,28 =86.53; p<0.001, c.f., Table 1). In contrast, both GA (F2,28 =1.47; p=0.246) and PCI (F2,28 =2.17; p=0.807) values were not different between baseline conditions and fast walking.

In the slow walking condition, gait speed decreased significantly (F2,28 =93.66; p<0.001). GA did not change significantly compared to baseline walking, (F2,28 =1.66; p=0.208). Conversely, PCI values increased significantly (F2,28 =7.99; p=0.002; slow vs. baseline walking: p<0.019).

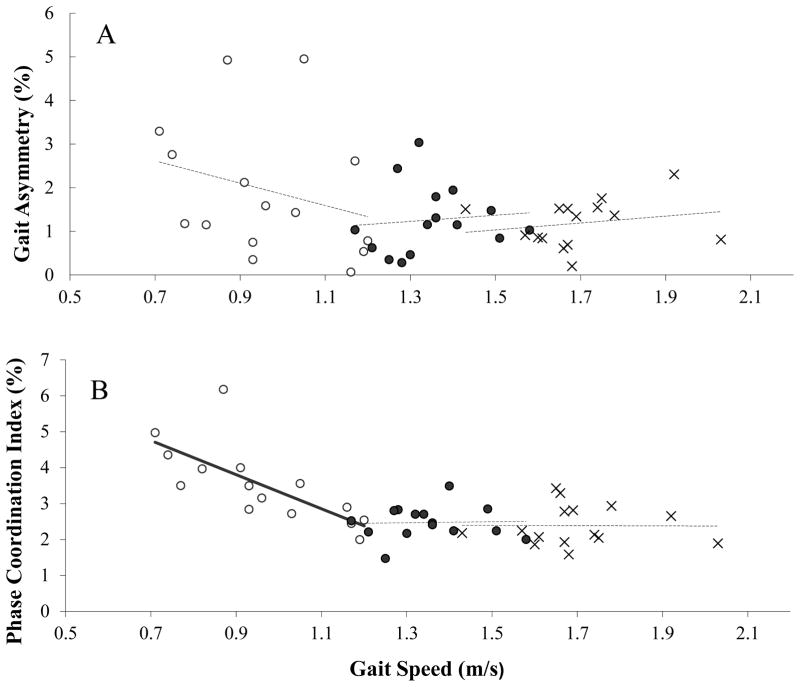

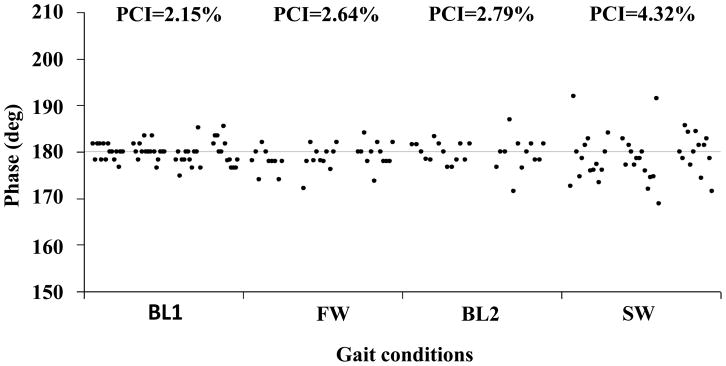

The effect of gait speed on PCI is illustrated in Figure 2. Left-right stepping phase (ϕ) values from one subject (same subject whose data are shown in Figure 1) from consecutive baseline walking (BL1), fast walking, baseline walking (BL2), and slow walking segments are plotted. It can be seen that ϕ values show the largest scattering in the slow walking condition.

Figure 2. Effect of gait speed on bilateral coordination of gait.

ϕ values taken from a subject during 4 consecutive walking conditions (BL1, FW- fast walking, BL2, SW- slow walking) are plotted. The abscissa represents the time that each walking condition lasted. The actual time each condition lasted was re-scaled for illustrative purposes. PCI values are indicated in the top row. A dashed horizontal line marks the value of 180°.

In all conditions, GA was not statistically correlated with gait speed (Spearman’s ρ < 0.379; p>0.164; Figure 3A). For PCI, there was a significant correlation with gait speed only in the slow walking condition (Spearman’s ρ = −0.838; p<0.001). A strong inverse linear relation was found in the slow walking condition between PCI and gait speed (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. The relation between gait asymmetry, PCI and gait speed.

A. Gait Asymmetry: For each subject, gait asymmetry values are plotted against gait speed as measured in the slow (○), usual (●) and fast (×) conditions. Regression analyses suggest that in none of these conditions there is a statistically significantly correlation between GA and gait speed (dashed regression lines, R2 ≤0.09, p ≥ 0.288; Pearson’s correlation analysis). B. For each subject, PCI values are plotted against gait speed as measured in the slow (symbols are same as in panel A). Regression analysis suggests that there is a statistically significant linear relationship between PCI and gait speed only for the slow walking condition (R2 = 0.53, p=0.002; Pearson’s correlation analysis). Curve fitting procedure identifies the following relationship between PCI and gait speed: PCI=A*Gait Speed +B, where A=−4.74 ± 1.23 and B=8.08 ± 1.20 (solid regression line). For the other two conditions, the linear relationships between PCI and Gait Speed (dashed lines) were not statistically significant (R2 < 0.003, p>0.892).

Changes in levels of ground reaction force impacts due to changes in gait speed

Walking speed was strongly associated with ground reaction force impact (GRFI) measured in the first stage of the stance period (recall Figure 1). GLM analysis with GRFI as the dependent variable (BL1, fast walking and BL2 conditions) showed that GRFI changed between conditions (F2,28 =131.57; p<0.001), with significant 2 way differences between fast walking vs. BL1 and fast walking vs. BL2 (p<0.001), but not for BL1 vs. BL2 (p=0.729).

For slow walking, GRFI changed significantly between conditions (i.e., BL2, slow walking and BL3; F2,28 =43.39; p<0.001), with significant 2 way differences between slow walking vs. BL2 and slow walking vs. BL3 (p<0.001), but not for BL2 vs. BL3 (p=0.647).

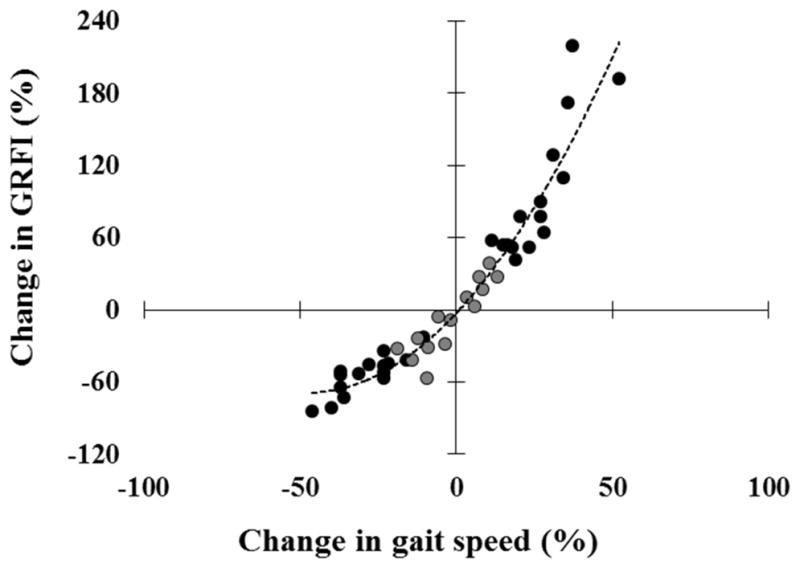

The data shown in Figure 4 illustrate the strong relationship between the levels of increase or the levels of decrease in the GRFI and the levels of the changes in gait speed.

Figure 4. The relation between the relative change in ground reaction force impact (GRFI) and the relative change in gait speed.

The relative increase in GRFI as function of the relative increase in gait speed during the fast walking condition with respect the BL1 (black circles in the upper right quadrate), and the relative decrease in GRFI as function of the relative decrease in gait speed during the slow walking condition with respect the BL2 (black circles in lower left quadrate), are plotted for each subject. In order to fill in near zero values data representing relative small changes in gait speed and relative small changes in GRFI were added (grey circles close to the origin – calculated from velocity and GRFI values in the different baseline conditions). Monotonously increasing relation is maintained throughout the spectrum (Spearman’s ρ = 0.946, p<0.001), and the trend line (dashed curve), suggests that the influence on GRFI is attenuated when the subjects intentionally reduce their gait speed in comparison to increasing gait speed. Across subjects, the relative increase of gait speed in the fast walking condition (+ 26.5 ± 10.6%) is similar to the relative decrease seen in the slow walking condition (−28.7 ± 9.9%; p=0.37, paired t-test).

Factors involved in reduced bilateral coordination during slow walking

Univariate analyses revealed that PCI was inversely correlated with GRFI in the slow walking condition, i.e., lower values of GRFI were associated with higher values of PCI (Spearman’s ρ =−0.586, p=0.022), and that relative changes in PCI were significantly correlated with the relative reduction in gait speed, the relative reduction in GRFI and the relative increase in GA (Spearman’s ρ ≥0.579, p≤ 0.024).

A stepwise regression was used to determine the independent predictors of the relative change in PCI during the slow walking condition. The stepwise regression with relative changes in GA, gait speed and GRFI variables included as possible predictors revealed that the relative change in PCI during the slow walking condition was dependent only on the relative reduction in gait speed (F1,12 = 5.20, p=0.042), which explained 30.2% of the variation in the relative increase in PCI (one data point was omitted because of extreme value of relative change in PCI, i.e., > 200%).

Discussion

We report here that due to an intentional increase or decrease of gait speed, gait asymmetry does not change, while the PCI does change. The results suggest that slow walking interferes with the left-right anti-phase stepping pattern but fast walking does not.

Effects of intentional increase or decrease in gait speed during over ground walking

From treadmill studies, it can be inferred that between walking and running gait patterns are switched by changing the sequence of activation of primary locomotor programs [20], but less so within the range of walking speeds (e.g., [5]). This is in agreement with our study’s result of lack of change in PCI values for fast over ground walking (recall Figure 3).

The higher values of PCI seen in the slow walking condition of the present study are in agreement with the increased inter lower limb phasing variability observed in treadmill walking [12]. GA did not change in the present study in response to changes in gait speed. Similar results have been observed previously (e.g., [3].

Theoretically, interlimb coordination and symmetric motor activation of the legs, as reflected by PCI and GA, respectively, are distinct from each other [21]. Empirically, in earlier studies GA was moderately associated with PCI [9]. The present results strengthen this distinction as we observed changes in PCI, but not in GA in the slow walking condition (recall Figure 3).

What does influence the change in left- right stepping coordination during slow walking?

Potential afferent involvement

It was suggested that sensory feedback from the legs while walking contributes to the coordination between CPGs on both sides of the spinal cord [10, 22–23]. Since we did not measure direct afferent responses, we consider GRFI as a proxy measure of afferent sensorial feedback because: (1) The tibial nerve is the one that innervates heel and mid-foot which are in contact with the ground until mid-stance; (2) The activity of the tibial nerve and tibialis anterior muscle reach a maximum shortly after heel strike, and shows a similar profile as the ground reaction force during stance [25], and speed effect with activity increasing as speed increased [15, 26], similar to the speed related changes observed in the gait force profile (ref #14 and Figure 1).

Despite the strong relationship between the changes in gait speed and the changes in GRFI (recall Figure 4), we suggest that the reduced GRFI values are not responsible for the high values of PCI in the slow walking condition.

First, the opposite effect is not seen, i.e., during the elevation of gait speed, no improvement in PCI was observed even though GRFI increased (recall Figure 4C). Further, the stepwise regression analysis preformed to underscore the factors that influence the changes in PCI identified the changes in gait speed as the sole contributor. Thus, it appears that when increasing locomotion speed, coordination pattern will become altered only when the locomotion mode changes from walking to running, perhaps due to benefits in mechanical stress and in energy consumption [27].

Potential supra- spinal involvement

In the present study, we did not measure attention or cognitive capabilities, a fact which limits our ability to directly assess the role of cognition in the results presented here. Implicitly, certain evidence supports the speculation that cognitive interference is related with the increased PCI during the slow walking condition. Unlike fast walking, slowing gait for several minutes consciously is less frequent during daily living. While hurrying to a meeting or train is common experience, no intentional sustained slowed walking readily comes to mind, as opposed to transient slowing [28]. PCI is a very sensitive parameter, influenced by cognitive load [29], disease [30], and walking conditions.

Thus, we raise the possibility that intentional slow walking demands the attention of the subject, either due to lack of daily experience in sustained slow walking, or since intrinsically, slow walking requires more attention. In dual tasking (DT) paradigms in which subjects are required to split their attention while walking, we reported on reduction in bilateral coordination of gait capabilities as expressed by PCI changes in healthy subjects [29], and in patients with Parkinson’s disease [30]. In addition, within the slow walking range, higher variability in the stance phase may also contribute to reduced bilateral coordination.

In conclusion, this study explicitly shows that gait asymmetry is stable in self selected usual, slow and fast walking. In contrast, bilateral coordination of left- right stepping is stable in the usual and in the fast ranges, but deteriorates when humans intentionally walk slowly. The speculation that this result is due to the attention demanding process involved when the subjects were focused on maintaining slowed gait requires further and more explicit probing.

Research highlights.

We study bilateral coordination during over ground walking in relation to gait speed

Young adults walked in self-selected pace and also intentially fast and slow.

Bilateral coordination of gait was affected in slow, but not in fast, walking

This might be due to increased attention required for intentional slowed walking.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their time and effort. We also thank Ms. Michal Leshem for her help with data collection and management. This study was funded in part by the Inheritance Fund of the Israeli Ministry of Health, NIH grants AG-14100, by the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (PDF), New York and the National Parkinson Foundation (NPF), Miami USA, by the European Union Sixth Framework Program, FET contract n° 018474-2. Dynamic Analysis of Physiological Networks (DAPHNet) and by the Israeli Ministry of Veteran Affairs Fund. RPB acknowledges financial support from the German Exchange Service (DAAD).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

No conflicts of interest are involved for any of the co-authors regarding this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kjaerulff O, Kiehn O. Distribution of networks generating and coordinating locomotor activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: a lesion study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5777–5794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadeghi H, Allard P, Prince F, Labelle H. Symmetry and limb dominance in able-bodied gait: a review. Gait and Posture. 2000;12:34–45. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagenaar RC, van Emmerik REA. Resonant frequencies of arms and legs identify different walking patterns. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33:853– 861. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bejek Z, Paroczai R, Illyes A, Kiss RM. The influence of walking speed on gait parameters in healthy people and in patients with osteoarthritis. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2006;14:612–622. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seay JF, Haddad JM, van Emmerik RE, Hamill J. Coordination variability around the walk to run transition during human locomotion. Motor Control. 2006;10:178–196. doi: 10.1123/mcj.10.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivanenko YP, Cappellini G, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F. Spatiotemporal organization of alpha-motoneuron activity in the human spinal cord during different gaits and gait transitions. European Journal of Neuroscience 2008. 2008;27:3351–3368. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shemmell J, Johansson J, Portra V, Gottlieb GL, Thomas JS, Corcos DM. Control of interjoint coordination during the swing phase of normal gait at different speeds. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation. 2007;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. New England of Medicine 2002. 2002;347:1761–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plotnik M, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. A New Measure for Quantifying the Bilateral Coordination of Human Gait: Effects of Aging and Parkinson’s Disease. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;181:561–570. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baev KV, Esipenko VB, Shimansky YP. Afferent control of central pattern generators: experimental analysis of scratching in the decerebrate cat. Neuroscience. 1991;40:239–256. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90187-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausdorff JM, Cudkowicz ME, Firtion R, Wei JY, Goldberger AL. Gait variability and basal ganglia disorders: stride-to-stride variations of gait cycle timing in Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Movement Disorders. 1998;13:428–437. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hausdorff JM, Schaafsma JD, Balash Y, Bartels AL, Gurevich T, Giladi N. Impaired regulation of stride variability in Parkinson’s disease subjects with freezing of gait. Experimental Brain Research. 2003;149:187–194. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1354-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller ST, Weisberger AM, Ray JL, Hasan SS, Shiavi RG, Spengler DM. Relationship between vertical ground reaction force and speed during walking, slow jogging, and running. Clinical Biomechanics. 1996;11:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(95)00068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masani K, Kouzaki M, Fukunaga T. Variability of ground reaction forces during treadmill walking. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92:1885–1890. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00969.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan K, Challis JH, Newell KM. Walking speed influences on gait cycle variability. Gait and Posture. 2007;26:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plotnik M, Giladi N, Balash Y, Peretz C, Hausdorff JM. Is freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease related to asymmetric motor function? Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:656–663. doi: 10.1002/ana.20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yogev G, Plotnik M, Peretz C, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Gait asymmetry in patients with Parkinson’s disease and elderly fallers: when does the bilateral coordination of gait require attention? Experimental Brain Research. 2007;177:336–346. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0676-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plotnik M, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Bilateral Coordination of Walking and Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;27:1999–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meijer R, Plotnik M, Zwaaftink EG, van Lummel RC, Ainsworth E, Martina JD, Hausdorff JM. Markedly impaired bilateral coordination of gait in post-stroke patients: Is this deficit distinct from asymmetry? A cohort study. Journal of Neuroengineering and Rehabilitation. 2011;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1743-0003-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cappellini G, Ivanenko YP, Poppele RE, Lacquaniti F. Motor patterns in human walking and running. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;95:3426–3437. doi: 10.1152/jn.00081.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plotnik M, Hausdorff JM. The role of gait rhythmicity and bilateral coordination of stepping in the pathophysiology of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2008;23:S444–S450. doi: 10.1002/mds.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duysens J, Van de Crommert HW. Neural control of locomotion; The central pattern generator from cats to humans. Gait and Posture. 1998;7:131–41. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(97)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poppele RE, Rankin A, Eian J. Dorsal spinocerebellar tract neurons respond to contralateral limb stepping. Experimental Brain Research 2003. 2003;149:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Crommert HW, Mulder T, Duysens J. Neural control of locomotion: sensory control of the central pattern generator and its relation to treadmill training. Gait and Posture. 1998;7:251–263. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(98)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter DA, Yack HJ. EMG profiles during normal human walking: stride-to-stride and inter-subject variability. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology. 1987;67:402–411. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmitz A, Silder A, Heiderscheit B, Mahoney J, Thelen DG. Differences in lower-extremity muscular activation during walking between healthy older and young adults. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2009;19:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minetti AE, Ardigo LP, Saibene F. The transition between walking and running in humans: metabolic and mechanical aspects at different gradients. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1994;150:315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1994.tb09692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.da Silva JJ, Barbieri FA, Gobbi LT. Adaptive locomotion for crossing a moving obstacle. Motor Control 2011. 2011;15:419–433. doi: 10.1123/mcj.15.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plotnik M, Jacobs A, Shaviv E, Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Age- associated changes in the effects of mental loading on the bilateral coordination of gait. (Abstract). Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress on Gait and Mental Function; February 26–28, 2010; Washington D.C., USA. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plotnik M, Dagan Y, Gurevich T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Effects of cognitive function on gait and dual tasking abilities in patients with Parkinson’s disease suffering from motor response fluctuations. Experimental Brain Research. 2011;208:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2469-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]