Abstract

Background

Cough is the most common complaint for which patients visit their primary care physician, being present in about 8% of consultations. A profusion of new evidence has made it necessary to produce a comprehensively updated version of the guideline on cough of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, DEGAM), which was last issued in 2008.

Methods

The interdisciplinary evidence and consensus based S3 guideline on cough of the DEGAM was updated on the basis of a systematic review of the relevant literature published from 2003 to July 2012 (MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science). Evidence levels were assessed and consensus procedures were followed as prescribed by AWMF standards, with the participation of 7 medical societies.

Results

182 publications were used to update the guideline, including 45 systematic reviews (26 of which included a meta-analysis) and 17 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). 11 recommendations for acute cough were approved by consensus in a nominal group process. The history and physical examination are the basis of diagnostic evaluation. When the clinical diagnosis is that of an acute, uncomplicated bronchitis, no laboratory tests, sputum evaluation, or chest x-rays should be performed, and antibiotics should not be given. There is inadequate evidence for the efficacy of antitussive or expectorant drugs against acute cough. The state of the evidence for phytotherapeutic agents is heterogeneous. Persons with community-acquired pneumonia should receive empirical antibiotic treatment for 5 to 7 days; specific risk factors can influence the choice of drug to be used. It is recommended that laboratory tests should not be performed and neuraminidase inhibitors should not be given in the routine management of influenza.

Conclusion

A specifically intended effect of these recommendations is to reduce the use of antibiotics to treat colds and acute bronchitis, for which they are not indicated. Further clinical trials of treatments for cough should be performed in order to extend the evidence base, which is now fragmentary.

Cough is the most frequent reason for visits to primary care physicians, accounting for around 8% of all consultations (1). The annual prevalence of cough in the general population is reported as circa 10–33% (2). By far the most common causes of acute cough are infections of the upper respiratory tract and acute bronchitis, which together account for more than 60% of diagnosed cases (1). The economic consequences are huge: respiratory tract infections are responsible for around 20% of cases of unfitness for work and circa 10% of the days off work due to illness (3).

This article summarizes the principal content and recommendations of the recently updated guideline on acute cough (cough of less than 8 weeks’ duration). The aim of the guideline is to depict the differential diagnoses of the symptom “cough” in adults and to guide the physician in identifying the cause and providing evidence-based treatment, with emphasis on relevance for primary care in practice. In line with the realities of primary care, the guidelines of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) are often not “diagnosis oriented.” This guideline also proceeds from the reason for consultation or from the symptom. The underlying diseases are discussed only in relation to the cough, not in detail.

Method

Revision of the guideline

Fifteen years ago the DEGAM adopted a wide-reaching concept for the development, dissemination, implementation, and evaluation of guidelines (4). These guidelines are supplemented by practice-oriented short versions and patient information sheets. The original version of the cough guideline was published in 2008. In 2013 the guideline was comprehensively updated according to the standards for S3 guidelines under the moderation of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF). The revision was necessitated by extensive new evidence regarding diagnosis and treatment.

Guideline group

Representatives of seven German medical societies were involved in revision of the guideline (Box 1). The members of the guideline group disclosed any potential conflicts of interest, and this process is documented in detail in the guideline report.

Box 1. Organizations and persons involved in the revision of the S3 guideline.

-

Institute for General Practice,

Charité Universitätsmedizin, Berlin

Dr. Sabine Beck*1

Prof. Vittoria Braun

Dr. Lorena Dini MScIH*1

Dr. Christoph Heintze MPH*1

Dr. Felix Holzinger MPH*1

Christiane Stöter MPH

Dr. Susanne Pruskil MScPH

Mehtap Hanenberg

Max Hartog

-

Representatives of medical societies

-

Prof. Stefan Andreas,

German Respiratory Society (DGP), German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM)*1

-

Patrick Heldmann MSc,

Federal Association of Self-employed

Physiotherapists (IFK)*1

-

Dr. Susanne Herold PhD,

German Society for Infectious Diseases (DGI)*1

Dr. Peter Kardos, German Respiratory League

-

Dorothea Pfeiffer-Kascha,

German Association for Physiotherapy (ZVK)*1

-

Dr. Guido Schmiemann MPH,

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM)*1

-

Prof. Heinrich Worth,

German Respiratory Society (DGP),

German Respiratory League*1

-

-

Guideline patrons (DEGAM)

Prof. Annette Becker

Dr. Günther Egidi

Dr. Detmar Jobst

Dr. Guido Schmiemann MPH

Dr. Hannelore Wächtler

-

The authors also thank

Prof. Jost Langhorst

Dr. Petra Klose

-

Dr. Cathleen Muche-Borowski MPH

(DEGAM, AWMF)

Dr. Monika Nothacker MPH (AWMF)*2

Dr. Anja Wollny MSc (DEGAM)

*1Participants of consensus conference

*2Moderator of consensus conference

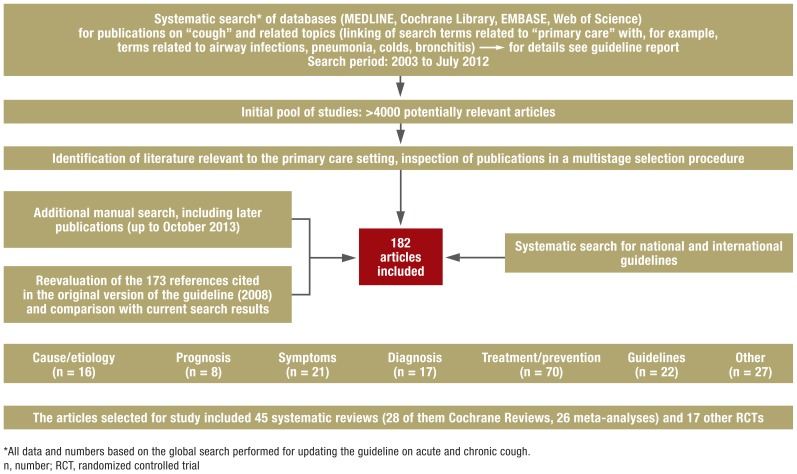

Literature review

The search strategy of the original version of the guideline was extended to July 2012. The MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, EMBASE and Web of Science databases were searched. This was followed by a search for national and international guidelines and a manual search that included sources with a publication date later than the end of the systematic database review period.

The identified sources were inspected (titles, abstracts, full-text versions). Relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and reviews (preferably systematic) were included, together with high-quality guidelines. Altogether, 182 publications were taken into account in updating the guideline (Box 2, Figure).

Box 2. Examples of search terms.

-

Search terms related to acute cough (selection)

(acute) cough*

common cold*

respiratory tract infections*

bronchitis

sputum

pneumonia

-

Search terms related to primary care (selection)

general practice

family practice*

family medicine

primary (health) care*

*Additional search in PubMed via corresponding MeSH terms; MeSH, medical subject headings

Figure.

Overview of the literature search

Consensus process

On 17 June 2013 the draft guideline was presented to a consensus conference moderated by the AWMF. The recommendations based on analysis of the available evidence were all adopted unanimously in a nominal group process, with the exception of one recommendation where one participant abstained owing to a self-perceived conflict of interest.

Strength of recommendation

The strength of recommendation depends on the strength of the evidence (study type, adequacy of study design, internal validity, likelihood of bias) and on the criteria of the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group, e.g., uncertainty regarding the extent of benefit conferred by a given diagnostic/therapeutic procedure, observance of patient preferences, and cost efficiency (5). Three grades of recommendation are distinguished: A, B, and C (Table 1).

Table 1. Recommendations and evidence.

| Recommendation strength A | Evidence level |

| Clinical diagnosis of acute uncomplicated bronchitis renders laboratory testing, sputum evaluation, and chest radiographs unnecessary. | TIa, PII ↔ |

| Uncomplicated acute bronchitis should not be treated with antibiotics. | TIa ↔ |

| The patient should be informed about the spontaneous course of acute (cold-related) cough. | TIb, SIII ↔ |

| Recommendation strength B | Evidence level |

| Technical investigations should be dispensed with in acute cough with no danger signs. | SIV ↑ |

| Acute cough in the context of infection should not be treated with expectorants (secretolytics, mucolytics). | TIa ↓ |

| Acute cough in the context of infection should only exceptionally be treated with antitussives. | TIIa ↔ |

| Sputum evaluation should not be routine in community-acquired pneumonia. | DII, CII ↔ |

| In the absence of risk factors, community-acquired pneumonia should be treated with an empirical oral antibiotic (an aminopenicillin, or alternatively a tetracycline or a macrolide) for 5 to 7 days. | TIa ↓ |

| In the presence of risk factors, community-acquired pneumonia should be treated with an empirical oral antibiotic (an aminopenicillin with a betalactamase inhibitor, or alternatively with a cephalosporin) for 5 to 7 days. | TIa ↓ |

| Laboratory testing (serology, direct demonstration of virus) should not be routine in suspicion of an influenza ‧infection. | TIa, DI ↓ |

| Neuraminidase inhibitors should be used only exceptionally for treatment of seasonal influenza. | TIa ↓ |

Evidence level depending on the respective research question: T, treatment-related; D, diagnosis-related; S, symptom-related; C, cause-related; P, prognosis-related

Level I–IV: strength of underlying evidence, e.g., for treatment-related questions: Ia, systematic reviews/meta-analyses; Ib, randomized controlled trials (RCT); IIa, controlled cohort studies; IIb, case–control studies; III, noncontrolled studies; IV, expert opinion/Good Clinical Practice, according to DEGAM guideline development concept (4)

Result of consensus process/application of GRADE criteria (5): ↔ Recommendation strength corresponds to evidence level, ↑ Upgrading, ↓ Downgrading GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

Guideline contents and recommendations

History and clinical examination

In a large proportion of patients with acute cough in the primary care setting, the diagnosis can be established from the medical history and the findings of a symptom-oriented physical examination. More technical diagnostic investigations are of little value in these cases (6).

The basic elements of history taking and physical examination are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. History, physical examination, and danger signs in acute cough.

| History and accompanying symptoms | ||

|

|

|

| Physical examination | ||

| ||

| Dangers | Symptoms/warning signs | |

| Pulmonary embolism | Dyspnea, tachypnea, thoracic pain, tachycardia | |

| Pulmonary edema | Tachypnea, dyspnea, rales | |

| Status asthmaticus | Expiratory rhonchi, prolonged expiration, wheezing; beware: "silent chest" | |

| Pneumothorax | Stabbing thoracic pain, asymmetric thoracic motion, unilateral attenuation of breath sounds, hypersonoric percussion sound | |

| Foreign body aspiration | Dyspnea, inspiratory stridor, elevated risk of aspiration in children and the elderly | |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Danger signs

The aim of history taking and physical examination is differentiation of harmless infections from serious diseases and early detection of potentially endangered patients. In occasional cases a life-threatening illness may be present or imminent (Table 2). The major warning signs (“red flags”) are dyspnea, tachypnea, thoracic pain, hemoptysis, a severely worsened general state, and changes in vital signs (high fever, tachycardia, arterial hypotension), together with the presence of any complicating underlying disease (e.g., malignancy, immune deficiency).

In urgent cases immediate action is required. Usually this means rapid transport to hospital accompanied by a (emergency) physician.

Frequent diseases, diagnosis, and treatment options

The principal differential diagnoses are listed in Table 3. The most frequent causes of acute cough are discussed in the following.

Table 3. Frequent causes of acute cough.

| Manifestation | Clinical presentation |

|---|---|

| Acute cough |

|

| Acute and chronic cough |

|

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection

Colds and acute bronchitis

Clinical presentation—Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI; “common cold”) are the most common cause of acute cough. Other typical symptoms are sore throat, runny nose, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, and sometimes a high temperature. Viral infections are usually to blame (adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, influenza- and parainfluenzaviruses, coronaviruses, respiratory syncytial virus [RSV], coxsackieviruses). The cough in acute bronchitis is first dry, then productive. There is no clear cut-off between a cold and acute bronchitis (involvement of the lower respiratory tract). In two thirds of cases a cold is self-limiting and lasts no longer than 2 weeks, while in bronchitis the cough can persist for several weeks (7). Acute sinusitis in the context of a cold may also stimulate cough receptors.

Diagnosis—If the history and clinical findings are compatible with cold or bronchitis, neither a chest radiograph nor clinical chemistry is necessary, provided there are no danger signs (Table 2). It is not necessary to distinguish between viral and bacterial bronchitis by determination of leukocytes or C-reactive protein (CRP), because the findings have no consequences for treatment (8). The color of the sputum has no predictive value for the diagnosis of bacterial bronchitis or the differentiation between pneumonia and bronchitis (9, 10). Sputum examination in an otherwise healthy bronchitis patient is pointless, because antibiotics are not required (11). Spirometry is indicated in the presence of signs of bronchial obstruction, because acute bronchitis can cause temporary airway constriction (9). A patient whose cough persists should be investigated in more detail after no more than 8 weeks.

Treatment—There is scant evidence on the efficacy of nonmedicinal treatments. From the physiological viewpoint it is sensible to maintain an adequate fluid intake, but drinking excessive amounts may bear the risk of hyponatremia (12). Abstention from smoking is recommended, because active and passive smokers take longer to recover from a cold (13). The results of RCTs are inconsistent with regard to the efficacy of nasal rinses/sprays with saline solution or steam inhalation (14, 15). To prevent transmission, it is better to cough into the elbow rather than the hand. Frequent hand washing at times of year when colds are prevalent is a sensible prophylactic measure (16).

Cough accompanying a cold or acute bronchitis/sinusitis usually resolves without any specific medicinal treatment. The patient should be told that the illness is self-limiting and harmless, and that therefore no drugs need to be given. Medications to relieve the symptoms can be prescribed, however, if the patient so wishes.

Analgesics such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen are recommended for symptomatic treatment of headache and muscle aches. RCTs have shown no advantage of antitussives (e.g., codeine) over placebo in reducing the urge to cough in the common cold. Nevertheless, they may improve sleep at night (17, 18). Expectorants are often prescribed to patients with productive cough, despite the lack of evidence for their efficacy against acute cough — there are no high-quality observational studies or RCTs for this indication (19). It is uncertain whether the findings of studies on chronic bronchitis are applicable to acute bronchitis or colds. Decongestant nose drops or nasal sprays ameliorate the symptoms in the short term, but their use for more than 7 days yields no persisting relief and may lead to atrophic rhinitis (20).

The evidence in respect of phytotherapeutics is difficult to interpret owing to the methodological heterogeneity of the available studies and the variable composition of plant-based preparations. A few RCTs found favorable effects of myrtol standardized with regard to severity of symptoms and time to recovery (21, 22). In one study the daytime coughing frequency was reduced by 62.1% on day 7 with myrtol, compared with 49.8% in patients who received placebo (22). The adverse effects are predominantly restricted to mild gastrointestinal symptoms. One RCT showed slightly improved symptom relief for a preparation of thyme and ivy leaf (77.6% reduction of cough attacks on day 9, compared with 55.9% for placebo). Comparable effects were found for a combination of thyme and primrose root. For these preparations too, there are no reports of severe side effects (23, 24). A small number of studies have shown slight dose-dependent acceleration of recovery from bronchitis for Pelargonium sidoides (25, 26). In placebo-controlled studies, the rate of gastrointestinal adverse effects was higher than for placebo. It should be noted that no firm conclusions can yet be drawn with regard to the benefit-to-harm ratio of Pelargonium sidoides owing to reports of possible severe hepatotoxicity. A Cochrane Review described the possible therapeutic efficacy of early administration of the above-ground parts of Echinacea (27). With oral intake the risk of adverse effects such as allergies is low. The contraindications (e.g., tuberculosis, AIDS, and autoimmune diseases) must be observed. No preventive or therapeutic effect could be found for the components of Echinacea root.

Regular intake of vitamin C has no effect on the frequency of colds in the average population. Only in those exposed to extreme physical demands (e.g., marathon runners) is the risk of a cold reduced (28). No therapeutic effect has been demonstrated for the use of vitamin C at the outset of a cold. A meta-analysis (29) showed that regular intake of zinc reduced the occurrence of cold symptoms; however, the adverse effects included nausea and an unpleasant taste in the mouth. Zinc cannot presently be recommended generally because the required dosage and duration of intake have not been established.

No antibiotic treatment is necessary in uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Antibiotics relieve the symptoms only marginally and shorten the recovery times by less than a day, while their disadvantages include potential adverse effects and development of resistance (11). The prescription frequency of antibiotics can be reduced by specific education of patients (9, 30). Administration of antibiotics can be considered in individual patients with serious chronic diseases or immune deficiencies, because in such cases it is often difficult to rule out pneumonia (9). Even in these patients antibiotics should not be prescribed routinely, however, because—as in general—the bronchitis is usually viral in origin.

Pneumonia

Clinical presentation—Coughing accompanied by tachypnea, tachycardia, high fever, typical auscultation findings, and pain on respiration indicates pneumonia. The manifestation of pneumonia may be atypical, e.g., without fever, in older or immune-suppressed patients or in those with chronic lung disease (31).

Diagnosis—Chest radiography in two projections is desirable particularly in the case of diagnostic uncertainty, severe illness, or comorbidities (31). Determination of neither leukocytes nor CRP absolutely confirms the diagnosis of pneumonia (32). CRP measurement may be helpful in monitoring the disease course, but routine determination is not advised in patients being treated out of the hospital setting. Studies have shown that measurement of procalcitonin may shorten or even avoid treatment with antibiotics, but routine procalcitonin determination cannot currently be recommended on grounds of cost (33, 34). In patients with community-acquired pneumonia who are being treated out of hospital, sputum tests have low sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, since targeted antibiotic treatment is not superior to empirical treatment (31, 34), sputum testing cannot be advised in a patient with community-acquired pneumonia.

Treatment—Clinically stable patients with community-acquired pneumonia can be treated by their primary care physician. Calculated antibiotic treatment depends on whether risk factors are present, meaning that an extended spectrum of pathogens must be taken into account (31). Clinical verification of treatment success is required after 48 to 72 hours. Continuation of treatment beyond 7 days does not increase the success rate (35). Fluoroquinolones should be used only exceptionally in the out-of-hospital setting owing to the severe adverse effects and development of resistance (Table 4).

Table 4. Antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia*.

| Patients without risk factors | ||

| Substances | Dosage | Duration |

|

Penicillin (oral): Amoxicillin |

<70 kg: 3 x 750 mg ≥ 70 kg: 3 x 1000 mg |

5–7 days |

|

Tetracycline (oral): Doxycycline |

<70 kg: first day 200 mg, then 100 mg ≥ 70 kg: 200 mg |

|

|

Macrolide (oral): Roxithromycin Clarithromycin |

1 x 300 mg 2 × 500 mg |

|

| Azithromycin | 1 × 500 mg | 3 days |

| Patients with risk factors (antibiotic treatment in previous 3 months, severe comorbidity, care home resident) | ||

| Substances | Dosage | Duration |

|

Aminopenicillin + betalactamase inhibitor: e.g., sultamicillin (oral) |

2 x 750 mg | 5–7 days |

|

Alternative: cephalosporins: e.g., cefuroxime axetil (oral) |

2 x 500 mg | |

*Modified from (31)

Influenza

Clinical presentation—The onset of symptoms is usually fulminant with high fever, pronounced malaise, and muscle pains.

Diagnosis—Influenza is usually diagnosed by clinical examination. Antibody determination or direct demonstration of virus on swabs should be carried out only in cases of doubt and when required to decide on the appropriate treatment (see below).

Treatment—Treatment with neuraminidase inhibitors is possible within the first 48 hours. The evidence on efficacy is not conclusive, however, so due to the poor cost–benefit ratio these substances can be recommended only in individual patients (e.g., in some cases of severe immune suppression) (36). Given the sometimes severe course of influenza, admission to hospital should be considered especially for multimorbid and elderly patients and those with complications.

Vaccination of the over-60s is recommended by the German Standing Committee on Vaccination Recommendations (STIKO). However, a new meta-analysis with strict inclusion criteria found that the efficacy of vaccination was sometimes inadequate. Moreover, there are no RCTs for the age group over 65 (37).

Pertussis

Clinical presentation—Increasingly, adults too are being affected by pertussis. Adult patients often present an atypical mild disease course with nonspecific dry cough. Vaccination secures immunity for no more than a few years. In the initial catarrhal stage differentiation of pertussis from a cold is difficult. The paroxysmal whooping cough sets in after 1 to 2 weeks (second peak) and can persist for 4 weeks (or longer).

Diagnosis—Identification of the pathogen by culture of nasopharyngeal secretions is reliable only within 2 weeks (38). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is more sensitive and may demonstrate the infection up to 4 weeks after onset, but is considerably more costly. In the late phase of disease only serology can confirm the diagnosis; the results should be interpreted in the context of the clinical presentation and after discussion with the laboratory.

Treatment—In the catarrhal stage recovery can be accelerated by treatment with azithromycin or clarithromycin. Antibiotic treatment is also useful later in the disease course, as it shortens the period of contagiousness (39). Antibiotic prophylaxis is advised for contact persons who share a household with a child under the age of 6 months. Vaccination according to the STIKO recommendations is urged. The vaccine against pertussis is available only as a combined vaccine.

Asthma and infection-exacerbated COPD

Chronic diseases of the respiratory tract may present acute crises, or may first manifest themselves with cough symptoms. The National Disease Management Guidelines should be consulted for advice on the diagnosis and treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Implementation and outlook

With regard to uncomplicated colds and acute bronchitis, the central recommendation of the guideline is diagnostic and therapeutic restraint. It is crucial to inform patients with these benign, self-limiting diseases that technical investigations and medicinal treatment are usually unnecessary. The guideline—and the corresponding patient information sheet—provides evidence-based arguments to assist the primary care physician confronted with insecurity and questions about treatment options. Even in the case of bronchitis with yellow–green sputum or mild fever, the patients can be reassured that the infection is most likely viral, so antibiotic treatment is unnecessary. In practice, patients with URTI or bronchitis are often prescribed antibiotics, promoting development of resistance (10, 40). If the patient insists on treatment, general symptom-relieving agents can be recommended (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestant nose drops). Another option could be phytotherapeutic substances, some of which have been shown to abbreviate or relieve the symptoms to some modest extent. However, the patients have to bear the costs and adverse effects—albeit mostly harmless—may occur. The physician and patient have to discuss whether use of such preparations is desirable (shared decision making). Furthermore, in the face of the widespread use of cough treatments for which there is no adequate evidence of benefit, methodologically sound, publicly financed studies are required in which these substance groups can be systematically investigated with regard to the indication “acute cough.”

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Laux G, Rosemann T, Körner T, et al. Detaillierte Erfassung von Inanspruchnahme, Morbidität, Erkrankungsverläufen und Ergebnissen durch episodenbezogene Dokumentation in der Hausarztpraxis innerhalb des Projekts CONTENT. Gesundheitswesen. 2007;69:284–291. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-976517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–1374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DAK-Gesundheit 2014. DAK Gesundheitsreport. www.dak.de/dak/gesundheit/DAK-Gesundheitsreport-1147504.html. 2014. (last accessed on 28 February 2014)

- 4.Gerlach FM, Abholz H, Berndt M, et al. Hannover, Düsseldorf: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM); 1999. Konzept zur Entwicklung, Verbreitung, Implementierung und Evaluation von Leitlinien für die hausärztliche Praxis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14 going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morice AH, McGarvey L, Pavord I. Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006;61(Suppl 1):i1–24. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.065144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebell MH, Lundgren J, Youngpairoj S. How long does a cough last? Comparing patients’ expectations with data from a systematic review of the literature. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:5–13. doi: 10.1370/afm.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rausch S, Flammang M, Haas N, et al. C-reactive protein to initiate or withhold antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections in adults, in primary care: review. Bull Soc Sci Med Grand Duche Luxemb. 2009:79–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzales R, Sande MA. Uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:981–991. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-12-200012190-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altiner A, Wilm S, Daubener W, et al. Sputum colour for diagnosis of a bacterial infection in patients with acute cough. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27:70–73. doi: 10.1080/02813430902759663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith S, Fahey T, Smucny J, Becker L. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000245.pub2. CD000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guppy MP, Mickan SM, Del Mar CB, Thorning S, Rack A. Advising patients to increase fluid intake for treating acute respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004419.pub3. CD004419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bensenor IM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. Active and passive smoking and risk of colds in women. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassel JC, King D, Spurling GK. Saline nasal irrigation for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006821.pub2. CD006821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh M. Heated, humidified air for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001728.pub5. CD001728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006207.pub4. CD006207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kardos P, Berck H, Fuchs KH, et al. Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin zur Diagnostik und Therapie von erwachsenen Patienten mit akutem und chronischem Husten. Pneumologie. 2010;64:336–373. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eccles R. The powerful placebo in cough studies? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:303–308. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2002.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub4. CD001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taverner D, Latte J. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub3. CD001953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthys H, de Mey C, Carls C, Rys A, Geib A, Wittig T. Efficacy and tolerability of myrtol standardized in acute bronchitis. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group clinical trial vs. cefuroxime and ambroxol. Arzneimittelforschung. 2000;50:700–711. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillissen A, Wittig T, Ehmen M, Krezdorn HG, de Mey C. A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial on the efficacy and tolerability of GeloMyrtol® forte in acute bronchitis. Drug Res. 2013;63:19–27. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holzinger F, Chenot JF. Systematic review of clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of ivy leaf (hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/382789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemmerich B. Evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of dry extracts of thyme herb and primrose root in adults suffering from acute bronchitis with productive cough. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre clinical trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2007;57:607–615. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1296656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agbabiaka TB, Guo R, Ernst E. Pelargonium sidoides for acute bronchitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthys H, Lizogub VG, Malek FA, Kieser M. Efficacy and tolerability of EPs 7630 tablets in patients with acute bronchitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-finding study with a herbal drug preparation from Pelargonium sidoides. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1413–1422. doi: 10.1185/03007991003798463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linde K, Barrett B, Wolkart K, Bauer R, Melchart D. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000530.pub2. CD000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemila H, Chalker E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4. CD000980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh M, Das RR. Zinc for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001364.pub4. CD001364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altiner A, Brockmann S, Sielk M, Wilm S, Wegscheider K, Abholz HH. Reducing antibiotic prescriptions for acute cough by motivating GPs to change their attitudes to communication and empowering patients: a cluster-randomized intervention study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:638–644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Höffken G, Lorenz J, Kern W, et al. Epidemiologie, Diagnostik, antimikrobielle Therapie und Management von erwachsenen Patienten mit ambulant erworbenen unteren Atemwegsinfektionen sowie ambulant erworbener Pneumonie - Update 2009. S3-Leitlinie der Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie, der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin, der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Infektiologie und vom Kompetenznetzwerk CAPNETZ. Pneumologie. 2009;63:e1–e68. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almirall J, Bolibar I, Toran P, et al. Contribution of C-reactive protein to the diagnosis and assessment of severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2004;125:1335–1342. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuetz P, Muller B, Christ-Crain M, et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007498.pub2. CD007498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy ML, Le Jeune I, Woodhead MA, Macfarlaned JT, Lim WS. Primary care summary of the British Thoracic Society Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: 2009 update. Endorsed by the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Primary Care Respiratory Society UK. Prim Care Respir J. 2010;19:21–27. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Athanassa Z, Falagas ME. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia : a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68:1841–1854. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Del Mar C. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornia PB, Hersh AL, Lipsky BA, Newman TB, Gonzales R. Does this coughing adolescent or adult patient have pertussis? JAMA. 2010;304:890–896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altunaiji Sultan M, Kukuruzovic Renata H, Curtis Nigel C, Massie J. Antibiotics for whooping cough (pertussis) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004404.pub3. CD004404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler CC, Kelly MJ, Hood K, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for discoloured sputum in acute cough/lower respiratory tract infection. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:119–125. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00133910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]