Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched a multimodal strategy and campaign in 2009 to improve hand hygiene practices worldwide. Our objective was to evaluate the implementation of the strategy in United States health care facilities.

Methods

From July through December 2011, US facilities participating in the WHO global campaign were invited to complete the Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework online, a validated tool based on the WHO multimodal strategy.

Results

Of 2,238 invited facilities, 168 participated in the survey (7.5%). A detailed analysis of 129, mainly nonteaching public facilities (80.6%), showed that most had an advanced or intermediate level of hand hygiene implementation progress (48.9% and 45.0%, respectively). The total Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework score was 36 points higher for facilities with staffing levels of infection preventionists > 0.75/100 beds than for those with lower ratios (P = .01) and 41 points higher for facilities participating in hand hygiene campaigns (P = .002).

Conclusion

Despite the low response rate, the survey results are unique and allow interesting reflections. Whereas the level of progress of most participating facilities was encouraging, this may reflect reporting bias, ie, better hospitals more likely to report. However, even in respondents, further improvement can be achieved, in particular by embedding hand hygiene in a stronger institutional safety climate and optimizing staffing levels dedicated to infection prevention. These results should encourage the launch of a coordinated national campaign and higher participation in the WHO global campaign.

Keywords: WHO multimodal strategy, Health care-associated infection, Infection control, US hospitals, WHO Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework

Hand hygiene is critical to the prevention of health care-associated infection (HAI), which leads to substantial morbidity, mortality, and health care costs in the United States and around the world.1,2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) published guidelines with recommendations for appropriate hand hygiene practices in health care settings in 2002 and 2009, respectively.3,4 However, compliance with recommended hand hygiene practices by health care workers (HCW) is unacceptably low. Even in high-income countries with more resources available for supplies, training, and promotion programs, average compliance reported in 2010 was approximately 40%.5 Challenges to improving hand hygiene practices include lack of guidance for field implementation of successful programs and standardized tools to assess hand hygiene practices and to monitor continually the adequacy of improvement programs.

In response to these challenges, WHO released a Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy (MHHIS) accompanied by an Implementation Toolkit to help the translation into practice of guideline recommendations.6 The MHHIS includes 5 key components: (1) system change, (2) HCWs' training and education, (3) evaluation and feedback, (4) reminders in the workplace, and (5) promotion of an institutional safety climate.7 The Implementation Toolkit includes a Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework (HHSAF) (Appendix), a validated tool for the evaluation of the level of implementation of the MHHIS 5 components in health care facilities.8,9 In 2009, a global campaign, “SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands,” was launched by WHO to promote uptake of the MHHIS.10 To date, more than 15,700 facilities worldwide have joined the movement.11

In the United States, there is currently no understanding of which components of the MMHIS have been implemented in health care facilities. A clear picture of existing hand hygiene improvement programs in a variety of US facilities could elucidate local needs and help define achievable benchmarks for facilities at all levels of implementation of hand hygiene improvement programs.12 The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate the degree of implementation of the MHHIS by US health care facilities; (2) examine differences in the degree of implementation by facility size, type, geographic region, and infection prevention infrastructure; and (3) suggest achievable benchmarks for implementation of hand hygiene improvement programs across a range of health care facilities.

Methods

Study sample

From July through December 2011, US health care facilities registered for the WHO “SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands” global initiative (N = 2,238) were invited by e-mail to participate in a WHO global survey13 by completing the WHO HHSAF (Appendix) and submitting their results confidentially through a dedicated Web site. Participation in the survey was also promoted on the CDC Hand Hygiene in Health care Settings Web site and through the electronic newsletter of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Three e-mail reminders were sent at bimonthly intervals. Facilities were asked to have the HHSAF completed by infection preventionists or senior managers fully informed about hand hygiene activities within the institution. Approval for the research was granted by the WHO, CDC, and Columbia University Medical Center institutional review boards.

Survey

The HHSAF is a questionnaire comprising 27 items grouped into 5 sections that reflect the MHHIS components (Appendix). Each component is scored out of 100 points (total maximum score: 500). According to their overall score, health care facilities are assigned to 1 of 4 levels of hand hygiene implementation progress: inadequate, basic, intermediate, or advanced. Facilities that have reached an advanced level are asked to complete 20 additional questions in a “leadership” section that is separately scored out of 20 points; a minimum of 12 points must be reached to qualify for leadership status. In previous testing, the HHSAF took less than 2 hours to complete; inter-rater reliability for total score and component scores ranged from κ 0.54 to 0.86.9 Participants were also asked to provide information about facility demographic characteristics (public or private sector, general or teaching status, type of care), number of inpatient beds, number of full-time equivalent infection preventionists and hospital physician epidemiologists, and participation or not in hand hygiene campaigns.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including frequencies and percentages were used to summarize facility characteristics. Mean total HHSAF score and median component scores were calculated in aggregate, as well as stratified and statistically compared by facility characteristics. The number of inpatient beds was positively skewed and therefore dichotomized at 200 beds by convention. Facility type was categorized as acute care only, long-term care with or without acute care, or ambulatory care only. Facilities were categorized into 1 of 4 US census regions, based on zip code. Staffing levels for infection preventionists and hospital physician epidemiologists were calculated per 100 inpatient beds. The modal response to individual HHSAF items was computed.

Student t tests were used to examine associations between facility characteristics and total HHSAF scores. Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to examine associations between facility characteristics and component scores because they were not normally distributed. Variables that demonstrated association at the P < .10 level were entered into a linear regression model to predict total HHSAF scores or into a multivariable logistic regression model to predict component scores higher versus lower than median. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for factors associated with high or low component scores. All tests were 2-tailed, and the significance level was set at α ≤ .05. Data analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

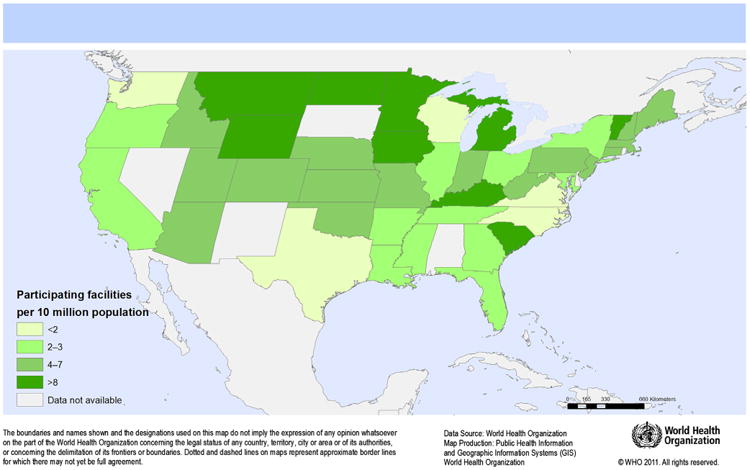

Of 2,238 invited facilities, 168 participated in the survey (response rate, 7.5%). Thirty- nine responses were excluded from the analysis because the HHSAF was incomplete. Characteristics of the 129 participating facilities from 42 states and Puerto Rico (Fig 1) are shown in Table 1. Facilities ranged in size from 5 to 671 inpatient beds. Most were nonteaching (80.6%), acute care (65.9%) facilities belonging to the public sector (56.6%). Median infection preventionist staffing was 0.76 per 100 beds (interquartile range [IQR], 0.6), and most facilities (60.5%) had no hospital epidemiologist. Almost half of all facilities reported that they participated in a national or subnational hand hygiene campaign (45.7%).

Fig 1.

Number of participating US facilities per 10,000,000 population by state.

Table 1. Characteristics of US facilities participating in the World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework survey 2011: n = 129.

| Facility characteristics | No. (%) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of inpatient beds | 125 (200) | |

| Sector | ||

| Private | 56 (43.4) | |

| Public | 73 (56.6) | |

| Teaching | 25 (19.4) | |

| Type | ||

| Acute care only | 81 (65.9) | |

| Ambulatory care only | 17 (13.8) | |

| Long-term care ± acute care | 25 (20.3) | |

| Region | ||

| Midwest | 45 (35.1) | |

| Northeast | 27 (21.1) | |

| South | 35 (27.3) | |

| West | 21 (16.4) | |

| Infection control nurses per 100 beds | 0.76 (0.6) | |

| Infection control physicians per 100 beds | 0 (0.4) | |

| Registered for SAVE LIVES campaign | 113 (87.6) | |

| Participant in a national or subnational hand hygiene campaign | 59 (45.7) |

IQR, interquartile range.

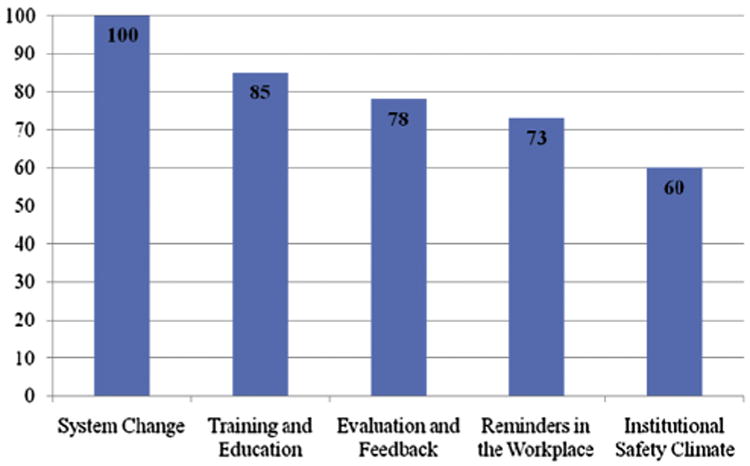

According to the HHSAF score, the level of hand hygiene implementation progress was advanced or intermediate in most facilities (Table 2). The mean total HHSAF score was 373.2 ± 70.8 (range, 178-500), which reflects an intermediate level of progress. Median component scores ranged from 100.0 (IQR, 5.0) for the system change component to 60.0 (IQR, 35.0) for the institutional safety climate component (Fig 2). All 63 facilities that reached an advanced level completed the leadership section. Median leadership score was 15.0 (IQR, 4.0). Fifty-nine facilities had ≥12 points and thus achieved leadership status.

Table 2. Level of progressin hand hygiene implementation in US facilities participating in the World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework survey 2011: n = 129.

| Level of progress (HHSAF score) | Definition | No. of facilities (%) | Range of total scores in US facilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced (>375) | Hand hygiene promotion and optimal hand hygiene practices have been sustained and/or improved, helping to embed a culture of safety in the health care setting. | 63 (48.9) | 376-500 |

| Intermediate (251-375) | An appropriate hand hygiene promotion strategy is in place, and hand hygiene practices have improved. It is now crucial to develop long-term plans to ensure that improvement is sustained and progresses. | 58 (45.0) | 251-375 |

| Basic (126-250) | Some measures are in place but not to a satisfactory standard. Further improvement is required. | 8 (6.2) | 178-250 |

| Inadequate (≤125) | Hand hygiene practices and promotion are deficient. Significant improvement is required. | 0 | 0 |

HHSAF, Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework.

Fig 2.

Median component scores for US facilities participating in the World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework survey 2011 (n = 129).

Overall, 77.5% of facilities reported that alcohol-based handrub is continuously available facility wide at each point of care. In 83.7% of facilities, annual mandatory training regarding hand hygiene is required of all HCWs, but only 53.5% reported having a dedicated budget for hand hygiene training. Hand hygiene compliance is evaluated by direct observation at least every 3 months at 76.1% of facilities. Less commonly, hand hygiene practices are indirectly monitored by surrogate markers, ie, alcohol-based handrub (39.8%) or soap consumption (34.1%). Immediate feedback is given to HCWs at the end of each hand hygiene observation session in 64% of facilities. The great majority of facilities displays posters explaining hand hygiene indications and correct techniques for hand rubbing and handwashing (89.9%, 80.6%, and 85.3%, respectively). However, a minority displays the posters in all wards/treatment areas (45.7%, 34.9%, and 37.2%, respectively). Other workplace reminders, such as screen savers, are used in 78.3% of facilities.

Most facilities reported that executive leaders such as the chief executive officer, medical director, and director of nursing have made a clear commitment to support hand hygiene improvement (80.5%, 70.5%, and 86.1%, respectively). More than half (58.1%) have established a dedicated hand hygiene team, and 37.2% have a system in place for designating hand hygiene champions. Patients are informed about the importance of hand hygiene at 85.9% of facilities, but a formalized program of patient engagement has been implemented at only 45.3%. Initiatives to support local continuous improvement in hand hygiene have not been widely implemented. For example, only 51.2% of facilities reported sharing local innovations in hand hygiene. Finally, less than half of all facilities (48.8%) have established a clear plan for participation in the WHO “SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands” initiative held annually on and around May 5.

Modal responses (ie, the most frequently chosen responses) to the leadership criteria of the HHSAF are listed in Table 3. All 63 facilities that completed the leadership section reported monitoring specific HAIs, and almost all (98.4%) reported performing a facility-wide prevalence survey of HAIs at least annually. Most of these advanced facilities present HAI rates to their facility leaders and HCWs in conjunction with hand hygiene compliance rates (96.8%). In addition, most evaluate also local obstacles to optimal hand hygiene compliance and causes of HAI and report these to their facility leaders (88.9%). Most (90.5%) advanced facilities reported that hand hygiene principles have been incorporated into local medical and nursing educational curricula; only 45.2% provide support for hand hygiene training to other facilities. Innovative types of hand hygiene reminders have been developed and tested at 58.7% of advanced facilities. Many (72.6%) reported having achieved their target for hand hygiene compliance improvement in the last year. However, few of the advanced facilities reported participating in scientific publications or conference presentations (41.3%) or developing a research agenda to address issues identified by the WHO guidelines (23.8%).

Table 3. Modal responses for leadership criteria in the World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework: n = 63.

| bottomic | Question | Modal response | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| System change | Has a cost-benefit analysis of infrastructure changes required for the performance of optimal hand hygiene at the point of care been performed? | No | 62.9 |

| Does alcohol-based hand rubbing account for at least 80% of hand hygiene actions performed in your facility? | Yes | 93.7 | |

| Training and education | Has the hand hygiene team undertaken training of representatives from other facilities in the area of hand hygiene promotion? | No | 54.8 |

| Have hand hygiene principles been incorporated into local medical and nursing educational curricula? | Yes | 90.5 | |

| Evaluation and feedback | Are specific HAIs monitored? (eg, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia, gram-negative bacteremia, device-related infections) | Yes | 100.0 |

| Is a system in place for monitoring of HAI in high-risk settings? (eg, intensive care and neonatal units) | Yes | 88.9 | |

| Is a facility-wide prevalence survey of HAI performed (at least) annually? | Yes | 98.4 | |

| Are HAI rates presented to facility leadership and health care workers in conjunction with hand hygiene compliance rates? | Yes | 96.8 | |

| Is a structured evaluation undertaken to understand the obstacles to optimal hand hygiene compliance and the causes of HAI at local level with results reported to the facility leadership? | Yes | 88.9 | |

| Reminders in the workplace | Is a system in place for the creation of new posters designed by local health care workers? | Yes | 60.3 |

| Are posters created in your facility used in other facilities? | No | 71.4 | |

| Have innovative types of hand hygiene reminders been developed and tested at the facility? | Yes | 58.7 | |

| Institutional safety climate | Has a local hand hygiene research agenda addressing issues identified by the WHO guidelines as requiring further investigation been developed? | No | 76.2 |

| Has your facility participated actively in publications or conference presentations (oral or poster) in the area of hand hygiene? | No | 58.7 | |

| Are patients invited to remind health care workers to perform hand hygiene? | Yes | 91.9 | |

| Are patients and visitors educated to correctly perform hand hygiene? | Yes | 85.7 | |

| Does your facility contribute to and support the national hand hygiene campaign (if existing)? | Yes | 79.4 | |

| Is impact evaluation of the hand hygiene campaign incorporated into forward planning of the infection control program? | Yes | 95.2 | |

| Does your facility set an annual target for improvement of hand hygiene compliance facility wide? | Yes | 93.7 | |

| If the facility has such a target, was it achieved last year? | Yes | 72.6 |

HAI, health care-associated infection.

In bivariate analysis, HHSAF total score and/or component scores were significantly associated with the following facility characteristics: teaching status, number of inpatient beds, infection preventionist staffing, and participation in subnational hand hygiene campaigns. In multivariable regression models (Table 4), taking facility size and teaching status into account, the average total HHSAF score was 36 points higher for facilities with infection preventionist staffing > 0.75 per 100 beds than for those with lower ratios (P = .01) and 41 points higher for facilities that participate in hand hygiene campaigns (P = .002). In addition, facilities with infection preventionist staffing > 0.75 per 100 beds had more than 3 times the odds of having high education/training scores and high institutional safety climate scores than those with lower infection preventionist staffing. Similarly, facilities that participate in hand hygiene campaigns were more likely to have high scores for education/training and institutional safety climate components.

Table 4. Factors independently associated with high total and component World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework scores.

| Total Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework score* | β Coefficient | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Small facility size < 200 beds | .51 | −30.55 to 31.56 |

| Teaching facility | −7.02 | −40.16 to 26.11 |

| Infection preventionist staffing > 0.75 per 100 beds | 36.34 | 8.29-64.38 |

| Registered for other campaign | 41.32 | 15.23-67.41 |

|

| ||

| Component scores† | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|

| ||

| Education and training component | ||

| Small facility size < 200 beds | 0.66 | 0.25-1.76 |

| Teaching facility | 0.66 | 0.2-1.87 |

| Infection preventionist staffing > 0.75 per 100 beds | 3.35 | 1.36-8.26 |

| Registered for other campaign | 2.48 | 1.09-5.66 |

| Institutional safety climate component | ||

| Small facility size < 200 beds | 0.46 | 0.17-1.24 |

| Teaching facility | 1.23 | 0.44-3.44 |

| Infection preventionist staffing > 0.75 per 100 beds | 3.05 | 1.22-7.60 |

| Registered for other campaign | 2.59 | 1.13-5.94 |

CI, confidence interval.

Note.

Linear regression model and

multivariable logistic regression model including variables demonstrating associations between facility characteristics and component scores at the P < .10 level in bivariate analysis.

Discussion

The United States has been a pioneer in hand hygiene best practices promotion since the issue of the CDC evidence-based recommendations in 2002, which formed the basis for global guidelines subsequently developed by the WHO. However, a study conducted in the following years showed that there was no evidence of either multidisciplinary programs to improve hand hygiene compliance or any impact of hand hygiene promotion on HAI rates in many US hospitals.14 In addition, lack of staff time and implementation tools were identified as major barriers to effective HCW education aimed at hand hygiene improvement.15 Following the launch of the WHO draft guidelines in 2006 and the availability of a multimodal strategy and tools for implementation, many US health care settings either initiated or refreshed their hand hygiene campaigns. More recently, progress in terms of hand hygiene infrastructure and practices, including HCW knowledge improvement, has been reported by single institutions16-20 and in 2 multicenter studies.21,22

For the first time, our survey presents a snapshot of the current level of implementation of hand hygiene improvement programs in US facilities from 42 states quite evenly distributed throughout 4 regions (Fig 1). Based on the HHSAF, the resulting picture allows an evaluation of achievements, as well as gaps and perspectives for improvement, with the caveat that respondents may have represented the “best” or most motivated settings. On average, the score indicating the level of progress was at the upper limits of “intermediate,” thus very close to the “advanced” level. This means that an appropriate hand hygiene promotion strategy is in place and that practices have improved, while sustainability efforts are in progress.

Specific component scores were high (median scores, 77.5-100.0) for system change, staff education, and hand hygiene monitoring and feedback. In particular, system change leading to the preferred use of alcohol-based hand rubbing for hand hygiene has been widely achieved as shown by the finding that these products are continuously available facility wide at each point of care in the vast majority of participating facilities. Even more impressive results relate to education on hand hygiene, which is mandatory for all professional categories at commencement of employment and then repeated at least annually, with a process in place to confirm that all HCWs complete this training. Finally, another very encouraging finding was that 76.1% of facilities measure hand hygiene compliance quarterly or more frequently. More than half of these facilities reported that measured hand hygiene compliance was higher than 80%, although this might not be based on validated data and standardized measurement methods. All these elements represent a great portion of a successful multimodal strategy for hand hygiene improvement.

Less encouraging results were found regarding the use of reminders in the workplace and the creation of an institutional safety climate supporting hand hygiene program implementation. Less than half of participating facilities have posters displayed with recommended indications for hand hygiene and performance techniques at the point of care in all wards. Other types of reminders, such as hand hygiene campaign screen savers, badges, or stickers, seem to be more popular. Although posters might be considered “old fashioned” tools, they are important reminders when placed at the point of care, especially if developed while taking social marketing concepts into account as demonstrated by Forrester et al in Canada23 and in very successful national campaigns in Europe and Australia.24-26

The creation of a strong institutional safety climate was identified as the weakest element of hand hygiene multimodal strategies, as shown by a median HHSAF component score of 60. Indeed, although most facilities reported that their leaders made a clear commitment to support hand hygiene improvement, 41.9% still lack a team formally dedicated to hand hygiene activities, and champions are not considered an important resource for hand hygiene promotion. The role of champions has been identified as a key component to support infection control.27-29 Engaged and enthusiastic champions can significantly contribute to a positive organizational culture and institutional safety climate by working around or through organizational and behavioral barriers to change the work environment. Another element with the potential to make a significant contribution to the creation of a safety climate is patient involvement.30 According to our survey, this is limited in most cases to informing patients about the importance of hand hygiene, although programs enabling actual patient empowerment are in place in a small number of facilities. However, consumer surveys conducted in the United States showed that both HCWs and patients would be in favor of active patient involvement in hand hygiene promotion programs.31,32 Based on promising results of studies involving patients,30 innovative approaches could be taken in this direction using the WHO tools to support patient participation.33,34

Importantly, an advanced level of hand hygiene program implementation is associated with the level of infection control staffing, in particular to achieve good progress in HCW education and for the creation of an institutional safety climate. This is consistent with evidence from different sources, including our study, that strongly supports the need for adequate proportions of infection preventionists based on the number of inpatient beds. The ratio of 1 infection preventionist per 250 hospital beds calculated more than 30 years ago remains a commonly cited reference.35 However, as suggested by a Delphi study conducted in 200136 and supported by our findings, a ratio of 0.8 to 1 infection preventionist per 100 hospital beds may be needed to effectively drive improvement. In addition, participating in a national or subnational campaign is another factor associated with high HHSAF scores. Since 2005, the WHO has strongly promoted and supported the establishment of national and subnational campaigns worldwide to enable local implementation, adaptation, and sustainability of hand hygiene improvement efforts.37,38 National campaigns are now present in more than 50 countries around the globe39 and have tremendously contributed to hand hygiene advocacy and improvement worldwide. To our knowledge, in addition to the hand hygiene promotion efforts coordinated by the CDC, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, statewide hand hygiene campaigns exist in Maryland, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. We hope that our findings will stimulate the launch of coordinated campaigns in other states.

Our study has important limitations. First, we had a very low response rate among invited health care facilities. This could be a result of the overwhelming demands placed on infection preventionists to meet mandatory reporting requirements and to address competing priorities set by state health departments or tied to ongoing quality improvement initiatives at their facilities. The fact that the survey could take more than 1 hour to complete may have played also a role in the willingness of infection preventionists to participate. In addition, whereas the WHO 5 Moments are considered the gold standard for hand hygiene practice40 and are clearly promoted by the CDC, many US facilities monitor hand hygiene at room entry and exit as a feasible and valid proxy measure of hand hygiene compliance. This narrowed measurement focus and the availability of other hand hygiene improvement campaigns in the United States may have slowed the uptake of the WHO MHHIS overall, particularly the HHSAF.

Second, the received responses might not reflect the actual status of hand hygiene activities in the United States because the sample was extracted only from those facilities participating in the WHO “SAVE LIVES: Clean Your Hands” global initiative. However, taking into consideration the intent of the survey, ie, to evaluate the level of implementation of the WHO MHHIS, this does minimize concern about the representativeness of the sample.

Third, reporting bias may be present in these survey results because the tool used relies on self-assessment. Still, we consider that the confidentiality and anonymity emphasized by the investigators and guaranteed through the data submission system have probably mitigated this risk. In addition, US institutions are accustomed to completing self-assessments such as the annual infection control risk assessment and hand hygiene adherence assessment required by the Joint Commission.

In conclusion, although our results concern a relatively small sample of US health care facilities, the study shows that the level of progress is intermediate or advanced in terms of implementation of hand hygiene promotion and activities according to strategies and principles recommended by both the WHO and the CDC. Ensuring appropriate infection preventionist staffing levels and participating in hand hygiene campaigns are highlighted as important assets to achieve a higher level of progress. Embedding hand hygiene efforts in a stronger institutional safety climate is clearly an area for improvement. A wider use of posters or other reminders detailing hand hygiene indications and performance techniques could certainly facilitate best practices at the point of care. These results should encourage the launch of a widespread and coordinated national campaign in the United States and the participation of more facilities in the WHO global initiative.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participating facilities for their collaboration, in particular, Katherine Ellingson, PhD, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, for her important participative role in study design, promotion of the survey dissemination, and contribution to the manuscript; Liliana Pievaroli, WHO, and Janet Pasricha, The Jenner Institute, Oxford University, Oxford, UK, for their technical support to the survey; and Rosemary Sudan, University of Geneva Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland, for her significant editing contribution.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

Supplementary Data: Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.11.015.

References

- 1.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in US hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:160–6. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:228–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce JM, Pittet D Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Association for Professionals in Infection Control. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in healthcare. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2009 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf.

- 5.Erasmus V, Daha TJ, Brug H, Richardus JH, Behrendt MD, Vos MC, et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:283–94. doi: 10.1086/650451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Guide to implementation: a guide to the implementation of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2009 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Guide_to_Implementation.pdf.

- 7.World Health Organization. How to improve hand hygiene: 5 critical components. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/background/how/en/index.html.

- 8.World Health Organization. Hand hygiene self-assessment framework 2010. [Accessed August 27, 2013]; Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/hhsa_framework_October_2010.pdf.

- 9.Stewardson AJ, Allegranzi B, Perneger TV, Attar H, Pittet D. Testing the WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework for usability and reliability. J Hosp Infect. 2013;83:30–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. SAVE LIVES Clean Your Hands: WHO's global annual campaign. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2009 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/en/

- 11.World Health Organization. Clean Care is Safer Care: registration update. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/registration_update/en/index.html.

- 12.Weissman NW, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Farmer RM, Weaver MT, Williams OD, et al. Achievable benchmarks of care: the ABCs of benchmarking. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5:269–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework global survey: summary report. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2012 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/summary_report_HHSAF_global_survey_May12.pdf.

- 14.Larson EL, Quiros D, Lin SX. Dissemination of the CDC's hand hygiene guideline and impact on infection rates. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:666–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton RM, Turon T, Cochran RL, Cardo D. Prepackaged hand hygiene educational tools facilitate implementation. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:152–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aboumatar H, Ristaino P, Davis RO, Thompson CB, Maragakis L, Cosgrove S, et al. Infection prevention promotion program based on the PRECEDE model: improving hand hygiene behaviors among healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:144–51. doi: 10.1086/663707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellingson K, Muder RR, Jain R, Kleinbaum D, Feng PJ, Cunningham C, et al. Sustained reduction in the clinical incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization or infection associated with a multifaceted infection control intervention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:1–8. doi: 10.1086/657665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer J, Mooney B, Gundlapalli A, Harbarth S, Stoddard GJ, Rubin MA, et al. Dissemination and sustainability of a hospital-wide hand hygiene program emphasizing positive reinforcement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:59–66. doi: 10.1086/657666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel JH, Korniewicz DM. Keeping patients safe: an interventional hand hygiene study at an oncology center. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:643–6. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.643-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wisniewski MF, Kim S, Trick WE, Welbel SF, Weinstein RA Chicago Antimicrobial Resistance Project. Effect of education on hand hygiene beliefs and practices: a 5-year program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:88–91. doi: 10.1086/510792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trick WE, Vernon MO, Welbel SF, Demarais P, Hayden MK, Weinstein R, et al. Multicenter intervention program to increase adherence to hand hygiene recommendations and glove use and to reduce the incidence of antimicrobial resistance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:42–9. doi: 10.1086/510809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashraf MS, Hussain SW, Agarwal N, Ashraf S, El-Kass G, Hussain R, et al. Hand hygiene in long-term care facilities: a multicenter study of knowledge, attitudes, practices, and barriers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:758–62. doi: 10.1086/653821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrester LA, Bryce EA, Mediaa AK. Clean Hands for Life: results of a large, multicentre, multifaceted, social marketing hand-hygiene campaign. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittet D, Hugonnet S, Harbarth S, Mourouga P, Sauvan V, Touveneau S, et al. Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Lancet. 2000;356:1307–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02814-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magiorakos AP, Leens E, Drouvot V, May-Michelangeli L, Reichardt C, Gastmeier P, et al. Pathways to clean hands: highlights of successful hand hygiene implementation strategies in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magiorakos AP, Suetens C, Boyd L, Costa C, Cunney R, Drouvot V, et al. National hand hygiene campaigns in Europe, 2000-2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14:30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damschroder LJ, Banaszak-Holl J, Kowalski CP, Forman J, Saint S, Krein SL. The role of the champion in infection prevention: results from a multisite qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:434–40. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.034199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saint S, Conti A, Bartoloni A, Virgili G, Mannelli F, Fumagalli S, et al. Improving healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence before patient contact: a before-and-after five-unit multimodal intervention in Tuscany. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:429–33. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White CM, Statile AM, Conway PH, Schoettker PJ, Solan LG, Unaka NI, et al. Utilizing improvement science methods to improve physician compliance with proper hand hygiene. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1042–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGuckin M, Storr J, Longtin Y, Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Patient empowerment and multimodal hand hygiene promotion: a win-win strategy. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:10–7. doi: 10.1177/1062860610373138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuckin M, Waterman R, Shubin A. Consumer attitudes about health care-acquired infections and hand hygiene. Am J Med Qual. 2006;21:342–6. doi: 10.1177/1062860606291328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waterman AD, Gallagher TH, Garbutt J, Waterman BM, Fraser V, Burroughs TE. Brief report: hospitalized patients' attitudes about and participation in error prevention. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:367–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Tips for implementing a successful patient participation programme. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Tips-for-patient-participation.pdf.

- 34.World Health Organization. Tips for patients to participate in hand hygiene improvement. [Accessed August 27, 2013];2013 Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/tips-forpatients.pdf.

- 35.Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Morgan WM, Emori TG, Munn VP, et al. The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:182–205. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Boyle C, Jackson M, Henly SJ. Staffing requirements for infection control programs in US health care facilities: Delphi project. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30:321–33. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.127930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathai E, Allegranzi B, Kilpatrick C, Bagheri Nejad S, Graafmans W, Pittet D. Promoting hand hygiene in healthcare through national/subnational campaigns. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pittet D, Donaldson L. Clean Care is Safer Care: a worldwide priority. Lancet. 2005;366:1246–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67506-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. WHO Clean Hands Net, a network of campaigning countries 2012. [Accessed August 27, 2013]; Available from: http://www.who.int/gpsc/national_campaigns/en/

- 40.Sax H, Allegranzi B, Uckay I, Larson E, Boyce J, Pittet D. “My five moments for hand hygiene”: a user-centred design approach to understand, train, monitor and report hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.