Abstract

High levels of inspired oxygen, hyperoxia, are frequently used in patients with acute respiratory failure. Hyperoxia can exacerbate acute respiratory failure, which has high mortality and no specific therapies. We identified a novel roles for PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1), a mitochondrial protein, and the cytosolic innate immune protein, NLRP3, in the lung and endothelium. We generated double knockouts (PINK1−/−/NLRP3−/−) as well as cell-targeted PINK1 silencing and lung-targeted overexpression constructs to specifically show that PINK1 mediates cytoprotection in wild type (WT) and NLRP3−/− mice. The ability to resist hyperoxia is proportional to PINK1 expression – PINK1−/− mice were the most susceptible, WT mice, which induced PINK1 after hyperoxia, had intermediate susceptibility and NLRP3−/− mice, which had high basal and hyperoxia-induced PINK1, were the least susceptible. Genetic deletion of PINK1 or PINK1 silencing in the lung endothelium increased susceptibility to hyperoxia via alterations in autophagy/mitophagy, proteasome activation, apoptosis and oxidant generation.

Introduction

High levels of oxygen are often administered as a necessary and life-saving intervention in critically ill patients. Yet, prolonged oxygen therapy at high concentrations (hyperoxia) has been shown to promote respiratory failure and increase mortality, for which specific therapies do not exists (1). Identifying the molecular pathways involved in promoting and resisting hyperoxia-induced lung injury and mortality are essential for the design of effective therapies against oxidant lung injury.

Targeting the inflammasome subunit, NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (Nalp3/Nlrp3/cryopyrin), has therapeutic effects in a variety of inflammatory diseases. Recently, Fukumoto et al. reported that NLRP3-deficient mice were protected from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury but the precise mechanism remained unclear and survival was not presented (2). We show significant survival differences in NLRP3, Asc and Caspase 1/11 knockout mice as well as identify PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) to be a novel mechanism whereby NLRP3 deficiency protects against lethal lung injury.

PINK1 helped to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis by inducing autophagy of damaged mitochondria, a process called mitophagy (3). We identified for the first time a critical cytoprotective role for lung endothelial PINK1 during lethal hyperoxia. Furthermore, we show that PINK1 mediates the protective effects of NLRP3 deficiency by regulating proteasome activity, apoptosis and oxidant production in lung endothelial cells and tissues during hyperoxia. These results offer new insights into PINK1 and inflammasome biology as well as establish previously unrecognized links with autophagy/mitophagy and proteasome activation.

Materials and Methods

Mice

NLRP3−/−, Asc−/− and Caspase 1/11−/− mice were provided by Dr. Richard Flavell, Yale University (4, 5). PINK1−/− mice were provided by Dr. Jack Elias, Brown University, and Dr. Jie Shen, Harvard University (6). All the mice were backcrossed for >10 generations onto a C57BL/6J background. NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice were generated by crossing NLRP3−/− mice with PINK1−/− mice for >10 generations. Mice bred and exposure to hyperoxic as described previously (7). All protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University.

Isolation of primary MLEC and hyperoxia exposures

Isolation of murine lung endothelial cells (MLEC) from mouse lungs have been described previously (8).

Construction of lentiviral vectors and administration

Lentivirus miRNA vectors with VE-Cad promoter has been described previously (9). PINK1 miRNA (lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA) was designed using target site 1283–1303 (GenBank accession AB053476.1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), 5′-GTGCGGTAATTGACTACAGCA-3′. Lentiviral PINK1 overexpression (lenti-PINK1 with CMV promoter), pReceiver-Lv158, was purchased (GeneCopoeia). Lentivirus production, titer measurement and intranasal administration were previously described (9).

Measurement of lung injury markers

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and protein quantification have been described previously (9).

Amplex red assay

Amplex® Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (Invitrogen) was used to check H2O2 released from mouse lung in BAL.

IL-1β ELISA

Mice bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was assessed for IL1β by ELISA (BD biosciences).

Western blot analysis

Lung or MLEC protein analyses were performed as previously described (7) using LC3B, p62, Caspase3, autophagocytosis-associated protein 3 (ATG3), ATG7, Beclin-1 (Cell Signaling Technology), PINK1 (Millipore, clone N4/15), LAMP2A, mitofusin-1 (MFN1), MFN2, optic atrophy type 1 (OPA1), dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) (Abcam), Proteasome 20S α6 subunit (Enzo Life Sci), PARIS (Millipore, clone N196/16), Caspase 1, IL-1β, Parkin, PGC-1α and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies.

Apoptosis Assays

The fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) was used to detect annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate labeling (BD Biosciences) on MLEC and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay (Roche Diagnostics) was used on mouse lung sections as described previously (10).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated gradually with graded alcohol solutions, and then washed with deionized water. After heat-induced antigen retrieval with target retrieval solution (pH 6.0; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) in a microwave pressure cooker, sections were blocked with serum-free protein block buffer (Dako) for 1 h. Sections were incubated with a 1:200 dilution of anti-PINK1 PINK1 (Millipore, clone N4/15) and anti-CD31 (Santa Cruz) antibody at 4°C overnight. After PBS washes, sections were incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG or Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG; 1:300 dilution; Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were washed 3 times by immersing in PBS for 5 min and then mounted with Prolong gold mounting medium with DAPI (Invitrogen). Sections were observed under dark field in independent fluorescence channels using an automated Olympus BX-61 microscope (x20, objective lens, NA 0.50; Olympus Imaging America, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with a cooled CCD camera (Q-Color 5; Olympus) and QCapture Pro 6.0 software (QImaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). After surveying the entire lung fields of 6–8 mice in each experimental condition, we selected representative sections that showed airway, vessel, and alveolus. As described previously (9), at least 15–20 nonoverlapping and nonatelectatic images were captured at x200 prior to selection. Images were cropped and prepared by Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) for the visualization.

Oxidant assays

CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen) was used to determine levels of ROS in endothelial cells as described previously (9).

Preparation of siRNA and transfection of siRNA duplexes

PINK1 siRNA was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Nonspecific siRNA scrambled duplex probes and transfection with Lipofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen) were used in MLECs as described previously (9, 11).

Proteasome Activity

Protein was extracted from lungs or MLEC and 10 μg processed for 20S Proteasome activity (Millipore). The free AMC fluorescence was quantified at 380/460 nM in a fluorometer (SpectraMaxGeminiXS, Molecular Devices). MLEC were pretreated with proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10 μM, EMD Millipore Chemicals), for 30 min prior to hyperoxia.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by Mann-Whitney Test or Student’s t test. Significant difference was accepted at p<0.05. Survival studies were evaluated using 2 tests and significant difference was accepted at p<0.05.

Results

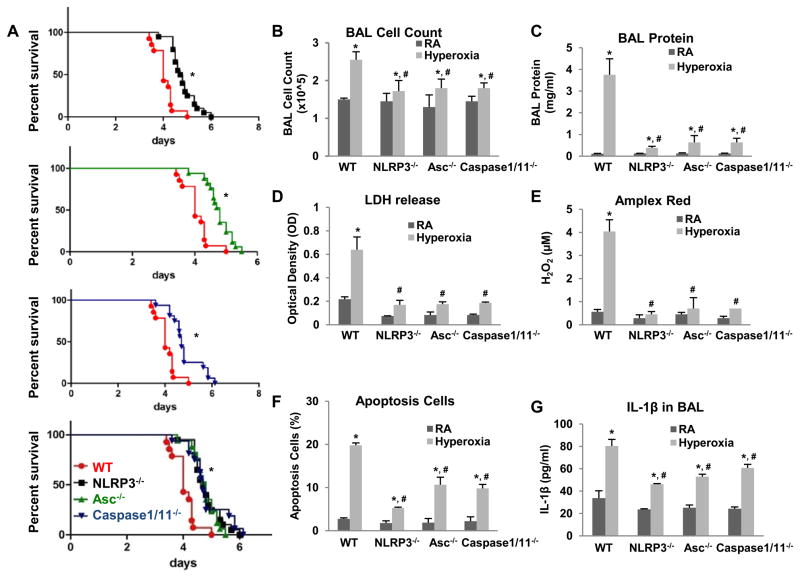

Inflammasome knockout mice are more resistant to lethal hyperoxia

We subjected NLRP3, Asc and Caspase 1 and 11 knockout mice to continuous hyperoxia. Knockout mice had significantly improved survival during hyperoxia compared to wild type (WT) mice (Fig. 1A). We previously reported 72 h of continuous hyperoxia as a time point of maximal lung injury, which we used as a representative time point (7). NLRP3−/−, Asc−/− and Caspase 1/11−/− mice exhibited significantly decreased lung injury (as assessed by bronchoalveolar lavage cell counts, protein and LDH), decreased reactive oxygen species generation (H2O2 release detected by Amplex red assay), decreased lung cell death (assessed by TUNEL) and decreased IL1β secretion compared to WT mice (Fig. 1B–G). Given that NLRP3 is a major component of the inflammasome complex and our recent findings that lung endothelial responses can determine survival in hyperoxia (9), we focused subsequent studies on NLRP3−/− mice and lung endothelial cells. Consistent with the survival data, we found that primary mouse lung endothelial cells (MLEC) from NLRP3−/− mice also exhibited a significantly protected phenotype compared to WT MLEC (data not shown). In summary, we show that deletion of specific components of the inflammasome results in decreased lung injury, oxidant production and, ultimately, increased survival.

Figure 1. NLRP3−/−, Asc−/− and Caspase 1/11−/− mice are more resistant to hyperoxia.

WT, NLRP3−/−, Asc−/− and Caspase 1/11−/− mice were exposed to continuous hyperoxia (A) or 72h of hyperoxia (B–G). RA, room air control. Survival proportions were compared among each set or four groups (A). *p <0.05 vs WT mice (n=15~18 for each group). B) Lung inflammation was detected by BAL cell counts. C) Lung permeability was assessed by BAL protein content. D) LDH activity assay from BAL fluid. E) Oxidant generation was detected by Amplex red from BAL fluid. F) TUNEL staining was performed on lung sections and the number of TUNEL-positive cells were quantitated and expressed as a percentage of the total number of lung cells counted on each section. G) IL1β was detected by ELISA in BAL. The values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p <0.05 vs RA WT mice; #p<0.05 vs hyperoxia WT mice (n=5 for each group).

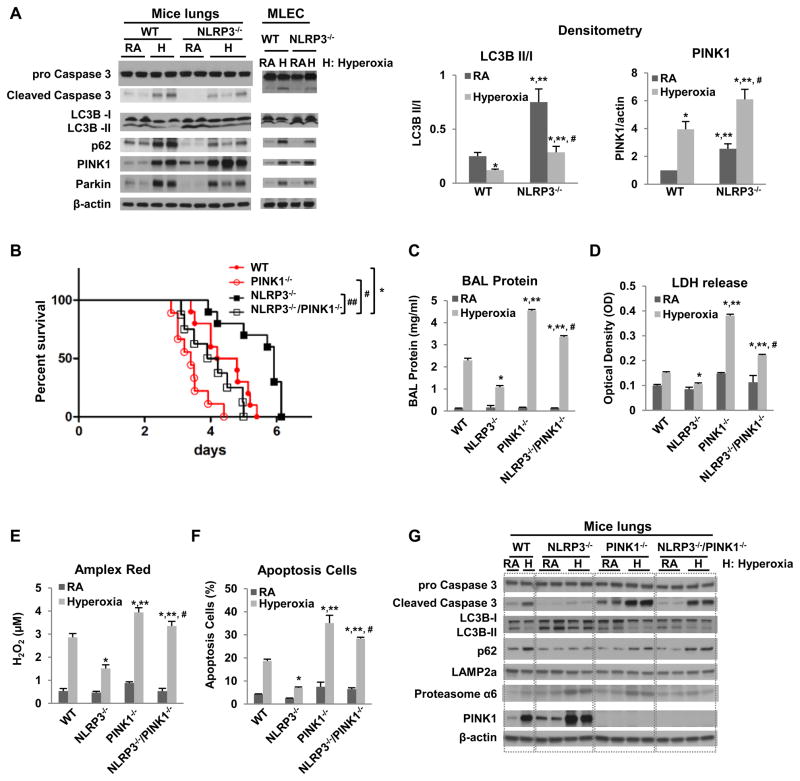

NLRP3−/− mice and MLEC have less Caspase 3 activation, increased autophagy and increased PINK1 expression

NLRP3−/− mouse lungs and MLEC had less basal as well as hyperoxia-induced Caspase 3 activation (Fig. 2A). Autophagy, a process of lysosomal turnover of organelles and proteins, has been implicated in oxidative stress and linked to Caspase-mediated cell death (12, 13). We found that NLRP3−/− lungs and MLEC had higher LC3B ratios at baseline and during hyperoxia than WT, which indicated that NLRP3 deficiency resulted in activated autophagy (Fig. 2A). The LC3B results were consistent with p62 (SQSTM1/sequestosome 1) expression, a selective substrate of autophagy. NLRP3−/− lungs and MLEC had higher LC3B ratios and lower p62 expression at baseline and during hyperoxia compared to WT, indicating that autophagy is activated in the setting of NLRP3 deficiency (Fig. 2A). Next, we measured PINK1, an initiator mitophagy. We found that NLRP3−/− lungs and MLEC had higher baseline and hyperoxia-induced PINK1 levels compared to WT, indicating that mitophagy is induced in the setting of NLRP3 deficiency (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. PINK1 is protective in WT and NLRP3−/− mice.

A) Mice or MLEC were exposed to RA or 72h hyperoxia. Lysates from mouse lungs or MLEC were isolated and immunoblotted against antibodies as listed. β-actin was used as protein loading control. RA, room air control; H, hyperoxia exposure. The left panel shows a representative Western blot, and the right panel shows the quantification based on densitometry for LC3B II/I and PINK to β-actin (experiments were performed in triplicate). B) Survival was compared amongst WT, NLRP3−/−, PINK1−/− and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice. *p <0.05 vs WT mice; #p <0.05 vs PINK1−/− mice, ##p <0.05 vs NLRP3−/− mice (n=10 for each group). C~F) WT, NLRP3−/−, PINK1−/− and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice were exposed to 72h of hyperoxia. C) Lung permeability. D) LDH activity. E) Oxidant generation. F) TUNEL-positive cells percentage. The values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05 vs WT mice; **p< 0.05 vs NLRP3−/− mice; #p<0.05 vs PINK1−/− mice (n=5 in each group). G) Lysates from mouse lungs were isolated and immunoblotted against antibodies as listed. One representative western blot out of three experiments is shown.

PINK1 deletion reversed the phenotype of NLRP3−/− mice

In order to determine whether PINK1 mediated the protective effects of NLRP3 deficiency in vivo we generated double knockout mice (NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/−). As expected, NLRP3−/− mice had increased survival during hyperoxia compared to WT mice but this was reversed in the absence of PINK1 (i.e. NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice). Of note, survival of the double knockouts was even worse than that of WT mice (Fig. 2B). Lung injury parameters (BAL protein content, LDH, oxidant production and apoptosis), were consistent with the survival data. PINK1−/− mice had the worst lung injury, the NLRP3−/− the least injury and the double knockouts had intermediate levels of lung injury after 72h hyperoxia (Fig. 2C–F). We reproduced the injury and survival data in MLEC using PINK1 siRNA and/or NLRP3 siRNA (data not shown). Collectively, these data show that PINK1 mediates anti-inflammatory, anti-injury and pro-survival effects in WT as well as in NLRP3−/− mice. NLRP3 deficiency resulted in higher basal as well as hyperoxia-induced PINK1 in lungs and cells but in absence of PINK1 the benefits of NLRP3 deficiency were lost.

We investigated specific molecules involved in cell survival, death and organelle turnover. NLRP3−/− lungs also had significantly decreased activated Caspase-3 expression in their lungs during hyperoxia, which was reversed in the setting of PINK1 deletion (Fig. 2G). The induction of autophagy and mitophagy in the setting of NLRP3 deficiency suggested that there may be increased efficiency in removing damaged organelles.

Lysosome and proteasome degradation are major mechanisms whereby dysfunctional mitochondria and misfolded proteins are removed. We first checked for LAMP2a (lysosome-associated membrane protein 2, subunit A), a receptor in the lysosomal membrane for chaperone-mediated autophagy (14). LAMP2a expression did not appear significantly different between the groups (Fig. 2G). However, 20S Proteasome α6, an α-type subunit in the 20S proteasome core particle, was induced in NLRP3−/− lungs and moderately induced in the NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice; this induction was partially reversed in the absence of PINK1. We explored the functional significance of proteasome activation in hyperoxia and in NLRP3−/− mice in subsequent studies.

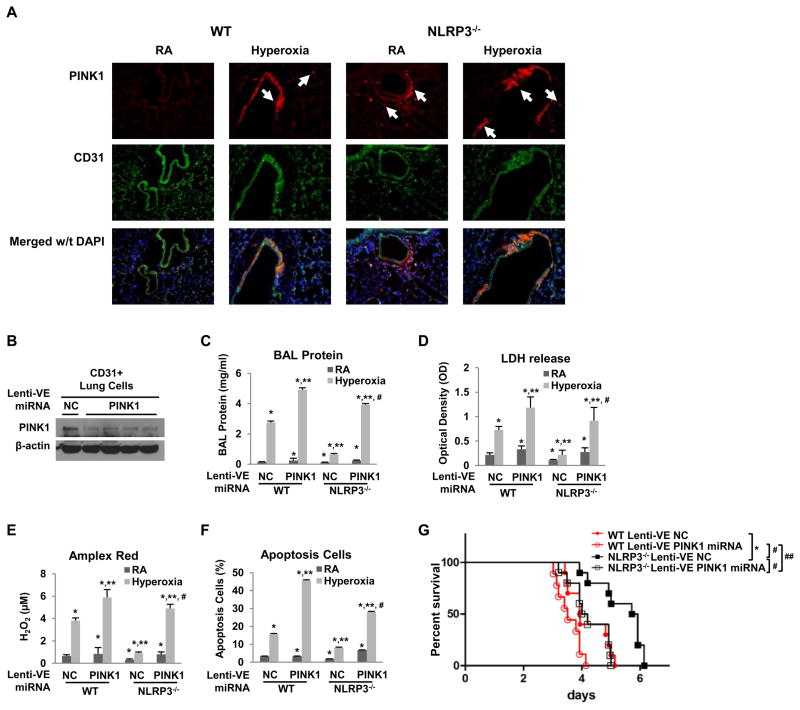

Lung endothelial PINK1 is protective in hyperoxia

We sought to determine the relevant cell type involved in mediating PINK1 effects. Our MLEC data pointed to an important role for endothelial cells. We evaluated lung sections of WT and NLRP3−/− mice after hyperoxia exposure or in room air control using PINK1 and endothelial-specific antibody, CD31. PINK1-immunoreactive cells (red conjugate) were detected specifically in the blood vessels after hyperoxia in WT and NLPR3−/− lungs but NLPR3−/− mice had greater PINK1 induction compared to WT mice. PINK1-positive cells were also detected outside of the blood vessels (e.g. macrophages) in room air control (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Lung endothelial-targeted PINK1 knockdown increased susceptibility to hyperoxia in vivo.

A) Co-localization of PINK1 and endothelium in lung sections using immunofluorescence. Mice were exposed to RA or 72h hyperoxia. Lung sections were immunostained for PINK1 (red) and CD31 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Upper panels show single immunostained images; lower panels show merged images. Original view of all photomicrographs × 200. Arrows indicate the PINK1 positive cells. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. WT and NLRP3−/− mice were treated with intranasal lentivirus (lenti-VE NC or lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA) and exposed to RA or 72h hyperoxia. B) Cell lysates of lung endothelium immunoselected by α-CD31 antibody from NLRP3−/− lungs were immunoblotted against PINK1 antibody. β-actin was used as protein loading control. One representative western blot out of three experiments is shown. C) Lung permeability. D) LDH activity. E) Oxidant generation. F) TUNEL-positive cells percentage. The values are expressed as mean ± SD.*p<0.05 vs RA lenti-VE NC WT mice; **p< 0.05 vs hyperoxia lenti-VE NC WT mice; #p<0.05 vs hyperoxia lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA WT mice (n=5 in each group). G) WT and NLRP3−/− mice were administered intranasal lentivirus for two weeks and exposed to continuous hyperoxia. Survival was compared amongst four groups. *p <0.05 vs WT lenti-VE NC mice; #p <0.05 vs NLRP3−/− lenti-VE NC mice; ##p<0.05 vs NLRP3−/− lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA mice (n=10 for each group).

In order to determine the function of endothelial PINK1 we delivered intranasal endothelial-specific lentiviral PINK1 silencing RNA (lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA) construct to mice, an approach we recently reported to be endothelial-specific (9). We isolated lung endothelium using α-CD31 antibody. The level of PINK1 expression in mouse lung endothelium was significantly decreased with lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA treatment but not by control lenti-VE NC (Fig. 3B). Mice given lenti-VE PINK1 miRNA had significantly increased lung permeability (BAL protein content, LDH, oxidants and apoptosis) compared to lenti-VE control-treated mice (Fig. 3C–F). Importantly, endothelial PINK1 knockdown reversed the survival advantage of NLRP3−/− mice (Fig. 3G). Even WT mice with endothelial PINK1 knockdown were much more sensitive to lethal hyperoxia. Taken together, the results indicated that in vivo endothelial PINK1 confers critical protective effects in WT and NLRP3−/− mice during hyperoxia.

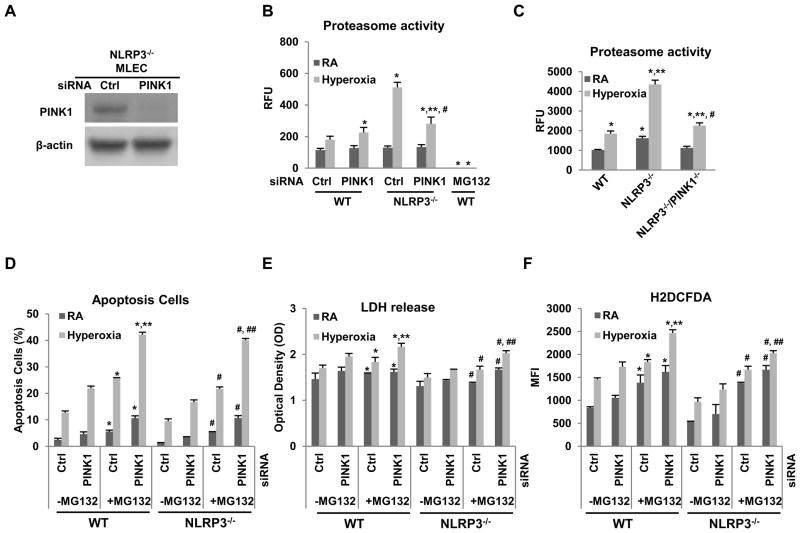

PINK1 and proteasome activity have synergistic protective effects against hyperoxia

To determine the relationship between PINK1 and proteasome activity during hyperoxia-induced cell injury and ROS generation, we silenced PINK1 in WT and NLRP3−/− MLEC. The knockdown efficiency of PINK1 siRNA is shown in Fig. 4A. PINK1 knockdown had cytotoxic effects but interestingly, blocking proteasome activity, with specific inhibitor MG-132, augmented the deleterious effects of PINK1 silencing in WT and NLRP3−/− MLEC (Fig. 4B–F). We also determined levels of proteasome activity in MLEC and lung tissues during hyperoxia. Hyperoxia induced proteasome activation in WT MLEC and lungs but in the setting of NLRP3 deficiency, proteasome activity is even higher (Fig. 4B–C). The silencing or loss of PINK1 significantly decreased proteasome activity in NLRP3−/− MLEC and mice, suggesting that PINK1-mediated protective effects are partially mediated by proteasome activation. aken together, these results demonstrated that PINK1 induction and proteasome activity are anti-injury mechanisms during hyperoxia. These studies are the first to demonstrate that NLRP3, via endothelial PINK1, regulates proteasome activity and that proteasome activation is necessary to prevent hyperoxia-induced injury and death.

Figure 4. NLRP3−/− had higher proteasome activity.

A) Lysates from NLRP3−/− MLECs transfected with PINK1 siRNA or Ctrl siRNA and immunoblotted against PINK1 antibody. β-actin was used as protein loading control. One representative western blot out of three experiments is shown. Proteasome activity was measured in MLEC transfected with PINK1 siRNA (B) or in lungs of WT, NLRP3−/− and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice (C) exposed to 72h of hyperoxia. MLEC treated with proteasome inhibitors, MG-132 at 10 μM, was used as a negative control. The values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p<0.05 vs corresponding WT Ctrl siRNA; **p<0.05 vs corresponding WT PINK1 siRNA; #p<0.05 vs corresponding NLRP3−/− in (B); *p<0.05 vs WT RA; **p<0.05 vs WT hyperoxia; #p<0.05 vs NLRP3−/− hyperoxia (n=5 for each group) in (C). WT and NLRP3−/− MLEC were transfected with PINK1 siRNA and treated with proteasome inhibitor MG-132 at 10μM (D~F), and then exposed to RA or 72h hyperoxia. D) Graphical quantitation of flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis. E) LDH activity assay from MLEC supernatant. F) H2O2 generation by CM-H2DCFDA staining. The values are expressed as mean ± SD. *p <0.05 vs corresponding group in no-MG132 WT MLEC; **p <0.05 vs corresponding Ctrl siRNA in WT; #p<0.05 vs corresponding group in no-MG132 NLRP3−/− MLEC; ##p<0.05 vs corresponding Ctrl siRNA in NLRP3−/− (experiments were performed in triplicates).

Overexpression PINK1 is protective in hyperoxia in vivo

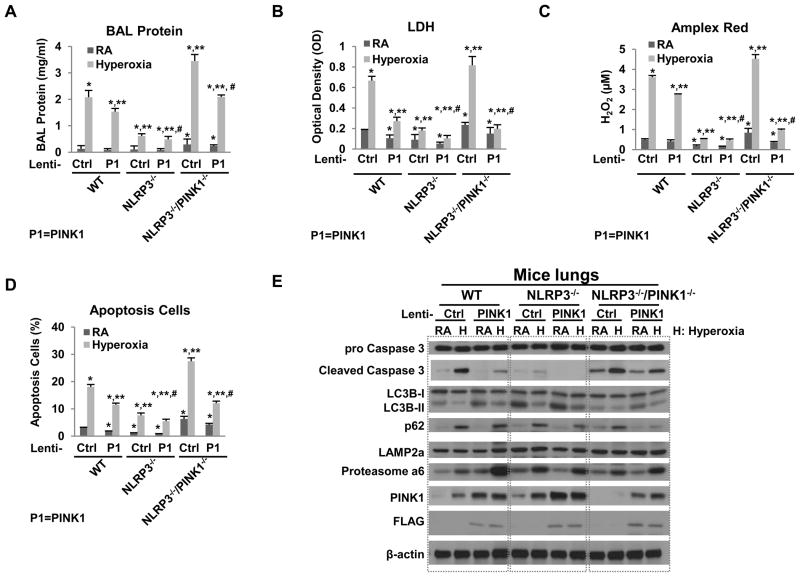

To demonstrate the impact of PINK1 overexpression in vivo, we treated WT, NLRP3−/− and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice with intranasal, thus lung-targeted, PINK1 overexpression lentivirus prior to 72h hyperoxia. We have previously demonstrated the efficacy of intranasal gene delivery (9). As expected, the FLAG-tag acted as overexpression of PINK1 was detected in total lung lyses (Fig. 5E). Lenti-PINK1 treatment improved lung inflammation and injury indices in all groups but the improvement was the most dramatic in the WT and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice (Fig. 5A–D). NLRP3−/− lungs already have high levels of PINK1 induction so additional overexpression may not offer significant advantages. Overexpression of PINK1 inhibited hyperoxia-induced Caspase-3 activation and activated autophagy, based on LC3B ratios and p62 expression level. LAMP2a was not significantly affected by PINK1 overexpression but 20S Proteasome α6 was increased, at least in WT lungs. These results confirmed that PINK1 regulates Caspase 3, autophagy and components of the UPS. As expected, PINK1 overexpression had the greatest rescue effect in NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice, which lack PINK1, and the least impact on NLRP3−/−, which already have high PINK1 expression at baseline and after hyperoxia.

Figure 5. Lung-targeted PINK1 overexpression decreased susceptibility to hyperoxia in vivo.

WT, NLRP3−/− and NLRP3−/−/PINK1−/− mice were administered intranasal lentivirus (lenti-Ctrl or lenti-PINK1) and exposed to RA or 72h hyperoxia. A) Lung permeability. B) LDH activity. C) Oxidant generation. D) TUNEL-positive cells percentage. The values are expressed as mean ± SD.*p<0.05 vs RA lenti-Ctrl WT mice; **p< 0.05 vs hyperoxia lenti-Ctrl WT mice; #p<0.05 vs hyperoxia lenti- PINK1 WT mice (n=5 in each group). E) Lysates from mouse lungs were isolated and immunoblotted against antibodies as listed. One representative western blot out of three experiments is shown.

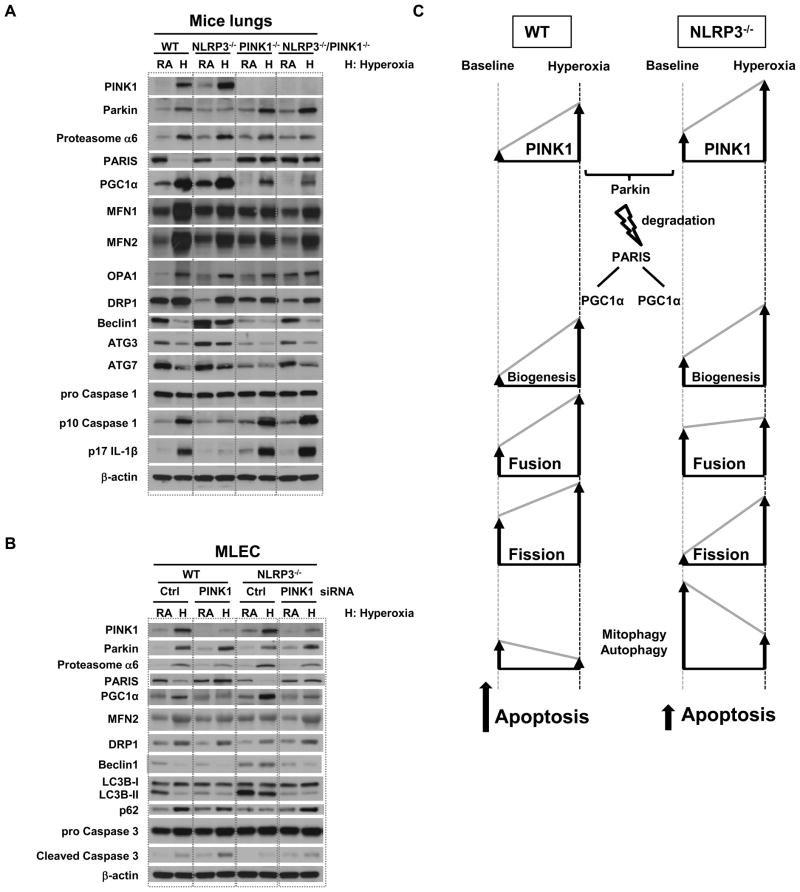

Effects of NLRP3 deficiency on mitochondrial maintenance and autophagy activation

In normal physiological conditions, PINK1 recruits Parkin to the mitochondria, and eliminates abnormal mitochondria through mitophagy. Recently, a novel Parkin interacting substrate, PARIS, was identified (15). PARIS is ubiquitinated by Parkin and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPS). Because PARIS represses the expression of PGC-1α, a key stimulator of mitochondrial biogenesis microtubule protein expression, degradation of PARIS by Parkin induces PGC-1α-dependent gene expression and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis. As shown in Fig. 2A & 6A, NLRP3 deficiency resulted in higher baseline and hyperoxia-induced PINK1 levels compared to WT lungs and MLEC. NLRP3 deficiency was also associated with higher baseline and hyperoxia-mediated PGC-1α expression. In PINK1 deficiency, PARIS expression is increased at baseline and after hyperoxia, which leads to greater PGC-1α repression and, ultimately, decreased mitochondrial biogenesis.

Figure 6. NLRP3 deficiency promotes mitochondrial maintenance and autophagy.

A) Lysates from mouse lungs were immunoblotted against antibodies as listed. B) WT and NLRP3−/− MLEC were transfected with PINK1 siRNA. Lysates from MLEC were immunoblotted against antibodies as listed. β-actin was used as protein loading control. RA, room air control; H, hyperoxia exposure. One representative western blot out of three experiments is shown. C) Proposed schematic. Mitochondria proliferate from preexisting mitochondria and generate new mitochondria (biogenesis). PINK1 recruits Parkin to the mitochondria and eliminates damaged mitochondria through autophagy/mitophagy. Parkin ubiquitinates and degrades PARIS through ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (USP). In NLRP3 deficiency, PINK1-Parkin is induced, PARIS is degraded and mitochondrial biogenesis is activated via PGC-1α. NLPR3 deficiency or PINK1 induction leads to reduced apoptosis. The arrows indicate the direction of change for each of the cellular processes; the height of the arrows indicates relative degree of change.

In addition to biogenesis, mitochondrial fate is determined by fission and fusion, which are mediated by four dynamin-related GTPase family proteins. Fusion/fission balance plays an important role in determining the fate of depolarized mitochondria (16, 17) and if altered, can produce dysfunctional or damaged mitochondria that are subsequently degraded by autophagy. Our data shows that NLRP3−/− lungs had exaggerated induction of mitochondrial fusion proteins MFN1, MFN2 and OPA1 during hyperoxia compared to WT lungs, which was blunted in the absence of PINK1 (Fig. 6A). Fission protein DRP1 expression was not significantly different in the groups during hyperoxia but basal levels appeared lower in NLRP3−/− and PINK1−/− lungs. These data suggest that NLRP3 and PINK1 regulate mitochondrial fusion and fission protein expression at baseline or during hyperoxia.

Based on our earlier observation that NLRP3−/− lungs had increased autophagy marker LC3B (Fig. 2A), we measured other autophagy-associated proteins, such as Beclin-1, which is required for the initiation of autophagosome formation (18) and ATG7 and ATG3, which control the conversion of LC3I into LC3II (19). Beclin-1, ATG7, and ATG3 were decreased by hyperoxia in WT lung and MLEC (Fig. 6A). NLRP3−/− lungs and MLEC showed greater baseline and hyperoxia-induced Beclin-1, ATG7, and ATG3 compared to WT, confirming our findings of increased autophagy in NLRP3 deficiency. As expected, NLRP3−/− tissues had decreased expression of its downstream proteins, mature Caspase 1 and IL-1β, compared to WT tissues but interestingly, both effector proteins were restored when PINK1 was deleted (Fig. 6A).

In order to confirm the functional role of PINK1 in NLRP3-mediated effects, we silenced PINK1 in WT and NLRP3−/− MLECs. PINK1 siRNA prevented PARIS degradation and inhibited mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 6B). PINK1 knockdown also disrupted the balance between mitochondrial fusion and fission. NLRP3−/− lungs and MLECs had lower baseline expression of fission protein DRP1, which was restored with PINK-deletion or siRNA (Fig. 6A, B). PINK1-deficient lungs also appeared to have less hyperoxia-induced MFN1 and MFN2 induction, which likely reflects decreased mitophagy in the absence of PINK1 compared to WT (Fig. 6A). PINK1 siRNA treatment led to decreased LC3B, increased p62 and decreased Beclin-1 indicating decreased autophagy. PINK1 siRNA was also associated with increased Caspase 3 activation (Fig. 6B). These data suggested that PINK1 silencing worsened the inhibition of autophagy during hyperoxia with a net effect of increased apoptosis.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our studies are the first to demonstrate a cytoprotective role of PINK1 in lungs and endothelium, identify previously unrecognized functional links between NLRP3 and PINK1 and show that NLRP3, via PINK1, regulates autophagy/mitophagy as well as proteasome activity. Previous studies showed PINK1 is expressed primarily in the central nervous system with some expression in epithelium (20). Our studies point to an important functional role for PINK1 in lung endothelium. NLRP3 deficiency has higher basal as well as hyperoxia-induced PINK1, and has less Caspase 3-mediated apoptosis and autophagy suppression during hyperoxia. We show that NLRP3 deficiency prevented Caspase 3-mediated apoptosis by upregulating autophagy, specifically mitophagy, via PINK1 expression, in lungs and MLEC during hyperoxia. PINK1 mediated the protective effects of NLPR3-deficiency by optimizing Parkin-PARIS-PGC-1α interactions, mitochondrial biogenesis and proteasome/disposal of dysfunctional mitochondria.

Hyperoxia leads to an accumulation of mitochondrial dysfunction, increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cell death. IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine that critically mediates diverse sterile inflammatory responses and also found in acute lung injury patients. NLRP3 inflammasome is implicated in sensing stress caused by ROS. Our studies define previously unrecognized ROS- and NLRP3-regulated mechanisms in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Mitochondrial ROS generation can reflect mitochondrial dysfunction or health. Macroautophagy (autophagy) is a lysosomal-dependent cellular pathway for the turnover of organelles and proteins. Autophagy involves the formation of double membrane vesicles (autophagosomes or autophagic vacuoles) that target and engulf cytosolic material, which may include damaged organelles or denatured proteins (21). We recently reported that hyperoxia induced mitochondrial oxidant generation and inhibition of autophagy in lungs and MLEC (22). We extended our studies to identify a pivotal role for NLPR3 in autophagy. NLRP4 and NLRP3 have been found to bind the extra-cellular domain of Beclin-1, a marker of autophagy, through the NACHT domain of NLR proteins (23, 24). The ASC component of NLRP3 may be polyubiquitinated and bound by p62 protein, thus targeting the inflammasome complex for degradation via LC3-mediated autophagy. Others have shown that knock-down of NLRP4 enhanced autophagy and that NLRP4 could inhibit the maturation of autophagosomes (23). We now show that NLRP3 deficiency or silencing activates autophagy at baseline and during stress conditions, pointing to the presence of crosstalk between autophagy and inflammasomes.

PINK1 and its downstream protein Parkin can mediate autophagy of damaged mitochondria in a processed called mitophagy. Mitophagy is the selective engulfment of mitochondria by autophagosomes and their subsequent catabolism by lysosomes. We found PINK1 expression was increased by hyperoxia and NLRP3 deficiency has higher basal as well as hyperoxia-induced PINK1 in lungs and cells. PINK1 prevents ROS generation both at baseline and during oxidant injury). The PINK1/Parkin pathway promotes mitochondrial fission and/or inhibits mitochondrial fusion (25, 26). In the current study, we found that PINK1-mediated Parkin ubiquitination plays a key role in the overall mitochondrial dynamics of the cell via mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis. The molecular mechanisms of PINK1 are through its effects on PARIS and PGC-1α, PARIS is a newly-identified Parkin interacting substrate, PARIS (ZNF746), whose levels are regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome system by binding to and ubiquitination by Parkin. PARIS represses the expression of PGC-1α and thereby inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis (15). We found that NLRP3 deficiency promotes PINK1/Parkin-induced degradation of PARIS, which causes de-repression of PGC-1α and increased mitochondrial biogenesis. In the absence of PINK1, these adaptive effects of NLRP3-deficiency are lost.

We summarized our proposed schemata in Fig 6C. Mitochondria proliferate from preexisting mitochondria and generate new mitochondria (biogenesis). At baseline conditions, PINK1 recruits Parkin to the mitochondria and eliminates abnormal mitochondria through mitophagy. Parkin ubiquitinates and degrades PARIS through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPS). At baseline, PARIS represses the expression of PGC-1α but once PARIS is degraded by Parkin, PGC-1α-dependent gene expression is activated and mitochondrial biogenesis ensues. Mitochondria then undergo either fission or fusion to enter it dynamic life cycle. Unhealthy mitochondria are sequestered in autophagosomes. Beclin-1 is the initiator of autophagosome formation; ATG7 and ATG3 regulate LC3-I into LC3-II conversion. Mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation serve to decrease the pool of dysfunctional mitochondria and increase functional mitochondria. We postulate that NLRP3 is involved in autophagy by binding and repressing Beclin-1. In NLRP3 deficiency, Beclin-1 is de-repressed and autophagy is activated. During acute stress, such as hyperoxia, the net effect of NLRP3 deficiency is a reduction of dysfunctional mitochondria, mitochondrial oxidant production, apoptosis and tissue injury/death. Loss of PINK1 leads to the deleterious accumulation of unhealthy mitochondria due to inadequate mitophagy. In addition, PARIS accumulates and represses PGC-1α, preventing mitochondrial biogenesis from increasing the pool of healthy mitochondria.

At this juncture, the precise relationship between NLRP3 and PINK1 is unclear but our studies show that a NLRP3-PINK1 axis is a critical determinant of susceptibility to hyperoxia-induced cell and tissue death. PINK1 silencing also exaggerated hyperoxia-induced mitochondrial oxidant generation and inhibition of autophagy, which ultimately increased hyperoxia-induced apoptosis. In the absence of PINK1, the endothelial cell cannot maintain adequate levels of autophagy or optimal protein disposal by the UPS, leading to Caspase 3-mediated cell death. To the best of our knowledge, these studies are the first to demonstrate that PINK1 and proteasome activity are important protective mechanisms during oxidant-induced endothelial and lung injury. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of NLRP3-mediated resistance to hyperoxia may lead to new therapeutic strategies in oxygen toxicity and deepen our understanding of the basic biology of oxidative injury.

References

- 1.Fisher AB. Oxygen therapy. Side effects and toxicity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122:61–69. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.5P2.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukumoto J, Fukumoto I, Parthasarathy PT, Cox R, Huynh B, Ramanathan GK, Venugopal RB, Allen-Gipson DS, Lockey RF, Kolliputi N. NLRP3 deletion protects from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;30:C182–189. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00086.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda S, Kitagishi Y, Kobayashi M. Function and characteristics of PINK1 in mitochondria. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:601587. doi: 10.1155/2013/601587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Galan JE, Askenase PW, Flavell RA. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuida K, Lippke JA, Ku G, Harding MW, Livingston DJ, Su MS, Flavell RA. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitada T, Pisani A, Porter DR, Yamaguchi H, Tscherter A, Martella G, Bonsi P, Zhang C, Pothos EN, Shen J. Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of PINK1-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11441–11446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702717104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Shan P, Hunt CR, Pandita TK, Lee PJ. A Protective Hsp70-TLR4 Pathway in Lethal Oxidant Lung Injury. J Immunol. 2013;191:1393–1403. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Shan P, Qureshi S, Homer R, Medzhitov R, Noble PW, Lee PJ. Cutting edge: TLR4 deficiency confers susceptibility to lethal oxidant lung injury. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:4834–4838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Jiang G, Sauler M, Lee PJ. Lung endothelial HO-1 targeting in vivo using lentiviral miRNA regulates apoptosis and autophagy during oxidant injury. FASEB J. 2013;27:4041–4058. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-231225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Shan P, Jiang D, Noble PW, Abraham NG, Kappas A, Lee PJ. Small interfering RNA targeting heme oxygenase-1 enhances ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung apoptosis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:10677–10684. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Shan P, Jiang G, Cohn L, Lee PJ. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency causes pulmonary emphysema. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:3050–3059. doi: 10.1172/JCI28139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin Y, Tanaka A, Choi AM, Ryter SW. Autophagic proteins: new facets of the oxygen paradox. Autophagy. 2012;8:426–428. doi: 10.4161/auto.19258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HP, Wang X, Chen ZH, Lee SJ, Huang MH, Wang Y, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagic proteins regulate cigarette smoke-induced apoptosis: protective role of heme oxygenase-1. Autophagy. 2008;4:887–895. doi: 10.4161/auto.6767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: a unique way to enter the lysosome world. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee YI, Pletinkova O, Troconso JC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. PARIS (ZNF746) repression of PGC-1alpha contributes to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2011;144:689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun M, Shen W, Zhong M, Wu P, Chen H, Lu A. Nandrolone attenuates aortic adaptation to exercise in rats. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;97:686–695. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak I. Mitophagy: a complex mechanism of mitochondrial removal. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:794–802. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordy C, He YW. The crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: where does this lead? Protein Cell. 2012;3:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1127-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Giordano S, Zhang J. Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem J. 2011;441:523–540. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann RF, Zarrintan S, Brandenburg SM, Kol A, de Bruin GH, Jafari S, Dijk F, Kalicharan D, Kelders M, Gosker HR, Ten Hacken NH, van der Want JJ, van Oosterhout AJ, Heijink IH. Prolonged cigarette smoke exposure alters mitochondrial structure and function in airway epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2013;14:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constantin M, Choi AJ, Cloonan SM, Ryter SW. Therapeutic potential of heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide in lung disease. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:859235. doi: 10.1155/2012/859235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Jiang G, Sauler M, Lee PJ. Lung endothelial HO-1 targeting in vivo using lentiviral miRNA regulates apoptosis and autophagy during oxidant injury. FASEB J. 2013 doi: 10.1096/fj.13-231225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jounai N, Kobiyama K, Shiina M, Ogata K, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F. NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic processes through an association with beclin1. J Immunol. 2011;186:1646–1655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A, Ojala J, Haapasalo A, Soininen H, Hiltunen M. Impaired autophagy and APP processing in Alzheimer’s disease: The potential role of Beclin 1 interactome. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;106–107:33–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitworth AJ, Pallanck LJ. The PINK1/Parkin pathway: a mitochondrial quality control system? J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:499–503. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang P, Galloway CA, Yoon Y. Control of mitochondrial morphology through differential interactions of mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]