Abstract

Retinoids are a family of signaling molecules derived from Vitamin A with well established roles in cellular differentiation. Physiologically active retinoids mediate transcriptional effects on cells through interactions with retinoic acid (RARs) and retinoid-X (RXR) receptors. Chromosomal translocations involving the RARα gene, which lead to impaired retinoid signaling, are implicated in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). All-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), alone and in combination with arsenic trioxide (ATO), restores differentiation in APL cells and promotes degradation of the abnormal oncogenic fusion protein through several proteolytic mechanisms. RARα fusion-protein elimination is emerging as critical to obtaining sustained remission and long-term cure in APL. Autophagy is a degradative cellular pathway involved in protein turnover. Both ATRA and ATO also induce autophagy in APL cells. Enhancing autophagy may therefore be of therapeutic benefit in resistant APL and could broaden the application of differentiation therapy to other cancers. Here we discuss retinoid signaling in hematopoiesis, leukemogenesis, and APL treatment. We highlight autophagy as a potential important regulator in anti-leukemic strategies.

Keywords: AML, APL, Arsenic Trioxide, ATRA, Autophagy, Differentiation, Hematopoiesis, PML-RARα, Retinoid

Introduction

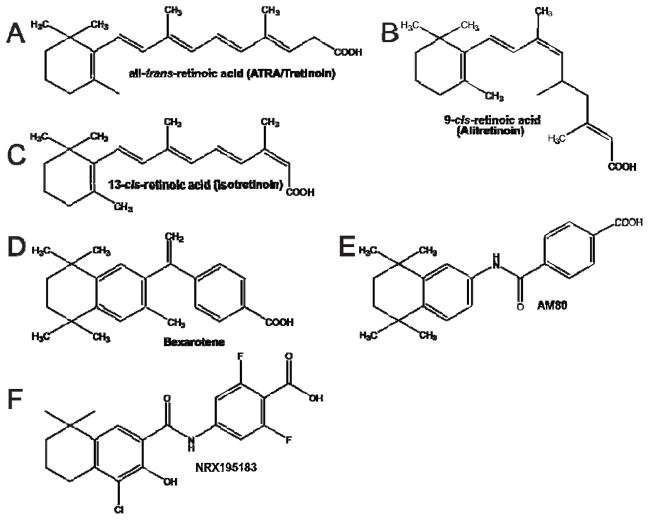

Retinoids are an important class of signaling molecules related to Vitamin A (retinol). Mammals lack the biosynthetic machinery to synthesize retinoids, therefore the primary sources of vitamin A are plant-derived carotenoids and animal food sources in the form of retinyl esters. Over the last two decades the molecular basis of the diverse roles of retinoids in the regulation of cellular differentiation and metabolism has emerged 1. Furthermore, retinoids remain the backbone of therapy for acute promyelocytic leumekia (APL) and hold promise for the prevention and treatment of some solid malignancies 2–4 (Figure 1). In this review we will summarize recent advances in understanding retinoid signaling pathways and how defects in retinoid signaling are implicated in leukemogenesis. We will highlight mechanistic links between retinoid signaling and the cellular process of autophagy and explore how these links may be exploited in future therapies for APL.

Figure 1. Physiological and clinically relevant retinoids.

Chemical structures for retinoids are provided for comparison. (A) all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA/Tretinoin), B. 9-cis-retinoic acid (Alitretinoin), C. 13-cis-retinoic acid (Isotretinoin), D. bexarotene (Targretin™), E. AM80 (Tamibarotene) and F. NRX195183.

Retinoid uptake, metabolism and transcriptional roles

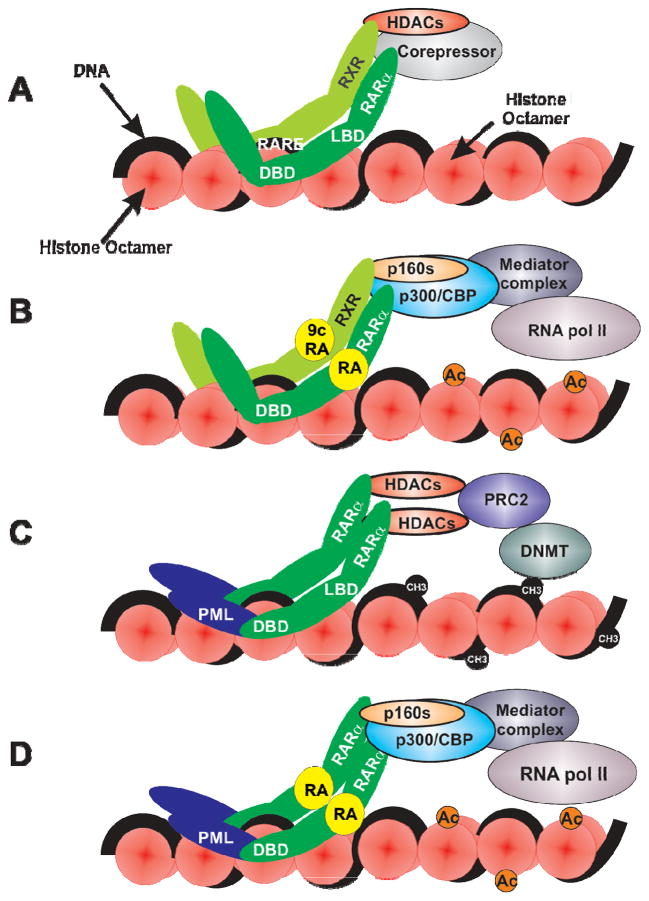

The intestinal absorption and metabolism of food-derived retinoids has been reviewed in detail recently 5. Briefly, dietary retinoids in the form of unesterified retinol derived from β-carotene or retinyl esters from animal sources are transported in the blood by the serum retinol binding protein (RBP4). Interestingly, RBP4 has emerged as a potential regulator of insulin sensitivity, providing a direct mechanistic link between dietary retinoids and metabolic regulation 5,6,7. In the eye, RBP4-bound retinol is delivered to target cells via the cell membrane-associated ‘stimulated by retinoic acid 6’ (STRA6) protein. However STRA6 is not required for vitamin A homeostasis in all tissues, but plays complex signaling roles in diverse tissue types8,9,10. Retinol can be esterified by lecithin-retinol acyl transferase (LRAT) for storage 11,12. Retinyl esters are mobilized from storage by hydrolases to yield retinol, which is converted via retinaldehyde to the active physiological form, all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), by retinaldehyde dehyrogenases. The transcriptional actions of retinoids are mediated by the retinoic acid (RARs) and rexinoid (RXRs) receptors. There are three isoforms of the RAR and RXR subtypes, each encoded by a unique gene: RARα(NR1B1), RARβ(NR1B2), RARγ(NR1B3) and RXRα(NR2B1), RXRβ(NR2B2), RXRγ (NR2B3). The RARs and RXRs are members of the nuclear receptor family of ligand dependent transcription factors 13,14 which preferentially interact with specific retinoic acid response elements, RAREs, in the promoter and/or enhancer regions of retinoid regulated genes 15. Whereas ATRA is the predominant physiological agonist for RARs 16–18, there is evidence that 9-cis-RA is an RXR agonist 19,20 (Figure 1). While there is evidence that both RARs and RXRs can form multimeric complexes with diverse nuclear receptor partners 21,22, the major transcriptional effects of retinoids are mediated by RXR-RAR heterodimers 23. In the absence of agonist, the RXR-RAR heterodimer functions to repress transcription by recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) complexes via the NCoR (NCoR1) and SMRT (NCoR2) corepressors 24–28. Conversely, in the presence of agonist, the RXR-RAR complex recruits multiple, enzymatically diverse transcriptional coregulators 29, including histone lysine acetyl transferases 30 and the mediator complex 31, which cooperate in the transcriptional activation of retinoid target genes (Figure 3). In the last decade, agonist induced repressors of RAR function have been identified. For example, PRAME (Preferentially Expressed Antigen in Melanoma) is recruited to ATRA activated RARs and prevents the recruitment of the transcriptional activation complex 32. Recruitment of RIP140-HDAC and polycomb complexes to RARs attenuates ATRA induced transcription 33–35. Thus in normal cells, retinoid receptor complexes transition through cycles of transcriptional activation and repression.

Figure 3.

A. RXR-RAR heterodimers bind to retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) via their DNA binding domains (DBD). In the absence of all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), RXR-RARs are believed to recruit corepressors (SMRT/NCoR) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) which function to temporarily repress transcription. B. In the presence of ATRA and 9-cis-retinoic acid, HDAC-corepressor complexes dissociate and enabling the recruitment of the p160, p300/CBP and mediator coactivators which increase histone acetylation (Ac) which in turn facilitate the transcriptional actions of RNA polymerase II. C. The PML-RARα fusion protein forms homodimers resulting in a stochiometric increase in HDAC-corepressor recruitment to RAREs which can facilitate the association of DNA methyltransferases resulting in the epigenetic silencing of retinoid response genes. D. Therapeutic ATRA concentrations are believed to promote differentiation in part via the restoration of retinoid target genes transcription.

Retinoid Signaling in Hematopoiesis

The importance of retinoid signaling in the regulation of embryonic development and stem cell differentiation is well established 36–39. A role for retinoids in the regulation of hematopoiesis has also emerged. Hematopoiesis is dependent upon rare multipotent cells termed hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), which reside within a specialized bone marrow stem cell niche. HSCs possess the ability to both self-renew and, through a series of hierarchical events, produce terminally differentiated progeny 40,41. Early epidemiologic observations that vitamin A deficient (VAD) human populations suffered impaired blood cell production prompted further investigation into the role of retinoid signaling in this process 42. More recent mechanistic insights have revealed important roles for retinoids in HSC homeostasis 43,44 and in myeloid 45, and lymphoid 46, 47 lineage development.

As hematopoiesis is required throughout life, the retention and maintenance of optimal HSC function is essential. HSCs express high levels of the retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1a1) enzyme, indicating a potentially important role for retinoid signaling in these cells 48. Interestingly, the nuclear receptors RARα and RARγ appear to have opposing effects on HSC fate, as observed in knockout and over-expression studies by Purton and colleagues 43,44. RARγ signaling enhances self-renewal, whereas RARα signaling promotes HSC proliferation and differentiation, with a decreased repopulation capacity 43,44.

Exogenous retinoid treatment of myeloid cells in culture leads to changes in the gene expression of known myeloid associated transcription factors, some of which harbor RAREs in their promoter regions, such as CCAAT enhancer binding protein ε (CEBPε), and others which likely represent secondary response genes, such as PU.1 49,50. However, mice with specific homozygous knockouts of either the RARα or RARγ nuclear receptors fail to show a robust hematopoietic defect. While a combined RARα−/− RARγ−/− genotype is embryonically lethal, extracted fetal liver cells contain a predominant granulocyte population similar to that of wild type mice 51,52. This suggests that the granulopoietic effects of retinoid signaling are likely to be more complex than those predicted from a linear ligand-receptor model. Possible receptor co-operation/compensation and extra-nuclear retinoid-mediated events remain to be fully elucidated. Animals subjected to a vitamin A deficient (VAD) diet from conception display impaired embryonic erythropoiesis with reduced GATA binding protein 2 (GATA-2) transcript levels 45. Mature cellular retinol-binding protein type I (CRBP1)-deficient mice have low endogenous vitamin A stores and when further subjected to a VAD diet, develop severe vitamin A (retinol) deficiency. This is associated with an abnormal expansion of neutrophils in the blood and extra-medullary tissues, with a high proportion of immature granulocytes, indicating a role for endogenous retinoids in terminal myeloid differentiation 51. As we will discuss further, this finding is definitively supported by the myeloid differentiation block observed in RARα-fusion leukemias.

Retinoids and leukemia

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a type of cancer characterized by the malignant proliferation of immature white blood cell precursors in the bone marrow and peripheral blood 53. The discovery of cytogenetic, molecular and epigenetic aberrations in AML patients has underscored the complex heterogeneity of this disease and has generated classification systems now used for prognostication 54,55. A common phenotypic abnormality in all cases of AML is a differentiation block in which malignant hematopoietic precursors are unable to differentiate into functional granulocytes. Overcoming this differentiation block pharmacologically is the basis of differentiation therapy 56.

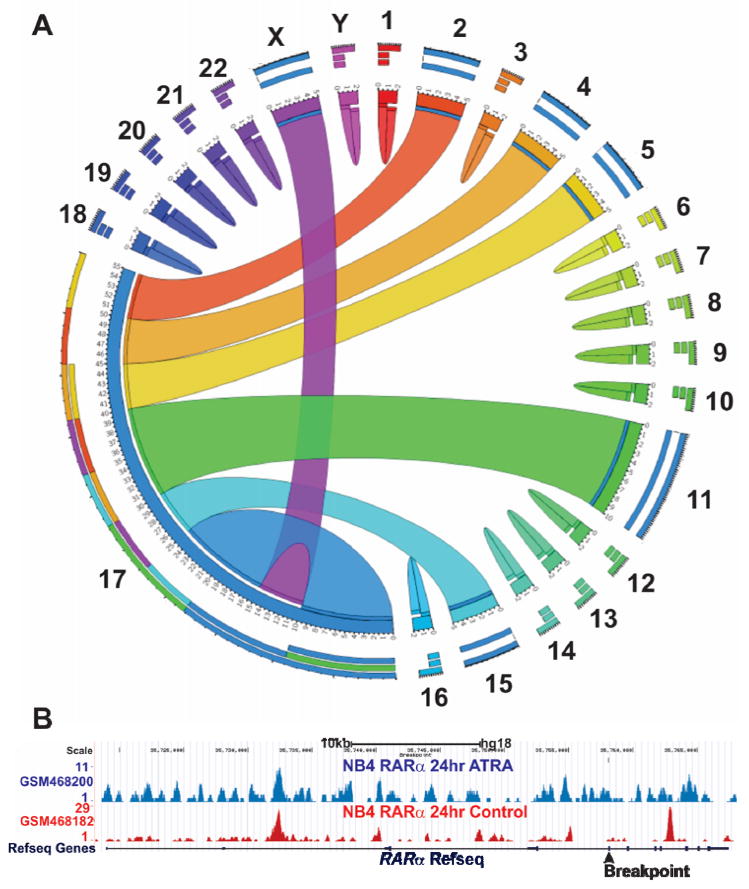

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) represents approximately 10% of all cases of AML. It is distinguished by a potentially lethal coagulation defect at presentation, characteristic cellular morphology, and chromosomal translocations that lead to oncogenic fusions of the RARα locus on chromosome 17q21 57–59. Since APL associated translocations were first identified in 1990, nine unique translocations have been identified, each involving the same genomic location within the second intron of the RARα gene (Figure 2) 57,58,60–67. Thus, all APL associated gene fusions contain the DNA and ligand binding domains (LBD) of the RARα protein.

Figure 2. RARα fusion proteins associated with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).

A. Circos (www.circos.ca) diagram depicting chromosomal origins of loci implicated in APL associated gene translocations. The RARα locus (chromosom me 17) is implicated in translocations involving the PML(Chr15), PLZF/ZBTB16(Chr11), NuMA(Chr11), NPM(Chr5), STAT5b(Chr17), PRKAR1A(Chr17), FIP1L1(Chr4), BCOR(ChrX) and OBFC2A/NABP1(Chr2). B. Chromatin immuno-precipitation coupled with next generation sequencing (ChIPseq) has been conducted to analyze the genomewide distribution of RARα in the absence (GSM468182) and presence of ATRA (GSM468200) in NB4 APL cells 72. Peaks indicate genomic regions where chromatin is associated with RARα binding. ATRA increases RARα association with the RARα locus (blue peaks). The chromosomal location of the common breakpoint present in all RARα fusion genes is indicated (

).

).

Current understanding of the mechanisms underlying gene translocations in leukemogenesis remains incomplete. However, gene fusions have also been identified in solid tumors, most notably associated with prostate cancer 68. Interestingly, the induction of Tmprss2 fusions in prostate cancer is dependent on androgen receptor (AR) induced intra- and inter-chromosomal interactions and inaccurate double strand DNA break repair 69–71. The AR is a nuclear receptor structurally and functionally related to the RARs and RXRs. Therefore, the insights obtained in prostate cancer may have some relevance to the induction of gene translocations involving the RARα locus in APL. In this context it is interesting to note that genomewide chromatin immunoprecipitation assay data 72 indicates RARα protein recruitment proximal to the common breakpoint within the RARα locus that is characteristic of APL (Figure 2B). Future studies should address a potential role for retinoid induced transcriptional events in the formation of chromosomal abnormalities involving the RARα locus.

RARα-fusion genes all share some functional characteristics, including the ability to homodimerize and antagonize retinoid signaling in a dominant-negative manner through associating with transcriptional repressor complexes 73,74. The most common RARα fusion partner, involved in over 95% of cases, is the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene 75. The resultant PML-RARα fusion protein binds to RAREs on DNA with high affinity and recruits repressive complexes that block the transcription of RARα target genes necessary for myeloid differentiation 76. PML-RARα binding at target promoters also recruits histone-deacetylases (HDACs), histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs), and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) that together result in repressive conformational chromatin changes, further blocking gene transcription 77,78 (Figure 3).

Retinoids in Treatment of Leukemia

Following pre-clinical observations in the early 1980s that ATRA promoted the granulocytic differentiation of promyelocytic leukemia cells in vitro, the first clinical trial of ATRA in the treatment of APL was conducted 79,80. Twenty-four patients (16 newly-diagnosed and 8 treatment-refractory) received treatment with single-agent ATRA, 23 of whom achieved a complete hematologic remission (CR) 81. Subsequent trials confirmed the efficacy of ATRA in remission induction and maintenance when compared with standard AML chemotherapy regimens. ATRA has been used in combination with optimized chemotherapy for APL treatment since 1990, transforming the prognosis of this aggressive condition, with CR rates of up to 95%, good second remission rates and 5 year disease-free survival (DFS) rates of up to 74% 82,83. However, the use of ATRA in non-APL AML has shown conflicting therapeutic benefit 84–87 and further clinical trials of retinoid combination therapies are underway (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1.

ATRA combination therapies reported in ClinicalTrials.gov (January 2014).

| Grants.gov ID | AML Subtype | Drug Combination | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00136461 | AML, MDS | ATRA and Bryostatin 1 | II |

| NCT00892190 | Refractory AML | Dasatinib, ATRA | I |

| NCT00867672 | AML | Decitabine, VPA, ATRA | II |

| NCT01575691 | AML, MDS | 5-aza-cytidine, VPA, ATRA | 1 |

| NCT00151255 | AML |

ATRA, Cytarabine, Idarubicin Mitoxantrone, Etoposide |

III |

| NCT00151242 | AML | Cytarabine, Idarubicin, Etoposide, ATRA, Pegfilgrastim | II/III |

| NCT00326170 | AML | 5-Azacytidine, VPA, ATRA | II |

| NCT01237808 | AML (NPM1 mutation) | Cytarabine, ATRA, Etoposide | III |

| NCT00143975 | Refractory AML | Cytarabine, Mitoxantrone, Gemtuzumab-Ozogamicin, ATRA | II |

| NCT00175812 | AML | Theophyllin, ATRA, VPA | I/II |

| NCT00339196 | AML, MDS | ATRA, VPA | II |

| NCT00049582 | AML, CML, MDS | Decitabine | I |

| NCT01161550 | Refractory AML | G-CSF, Cladribine, Cytarabine, ATRA, Midostaurin | I |

| NCT00995332 | AML | Cytarabine, ATRA, VPA | I |

| NCT00146120 | AML | Idarubicin, Cytosin-Arabinosid, Etoposide, ATRA | III |

| NCT00893399 | AML (with NPM1 mutation) |

ATRA, Standard chemotherapy Gemtuzumab-Ozogamicin |

III |

| NCT01369368 | AML relapse after allo- transplantation | ATRA, 5-azacitidine, VPA, hydroxurea and eventually donor leukocyte infusions. | I/II |

| NCT00615784 | AML | Bexarotene | II |

| NCT01020539 | AML, MDS, Juvenile myelomoncytic leukemia | Fludarabine, Busulfan, Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) Prophylaxis, Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin, Anti-Thymocyte Globulin, Isotretinoin | I |

| NCT00003405 | AML | Interferon α, Amifostine trihydrate, bromodeoxyuridine, cytarabine, idarubicin, idoxuridine, isotretinoin, mitoxantrone hydrochloride | II |

| NCT00482833 | AML | As2O3, Idarubicin, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, ATRA | III |

| NCT00217412 | Refractory cancers | SAHA, ATRA | I |

| NCT00003619 | AML, MDS, ALL, | Topotecan, fludarabine, cytarabine, and filgrastim followed by peripheral stem cell transplantation or Isotretinoin | I/II |

| NCT00006239 | AML, MDS | Sodium phenylbutyrate, Tretinoin | I |

| NCT00866073 | AML | Decitabine | II |

| NCT01987297 | AML | ATRA+ As2O3, ATRA+chemo | IV |

| NCT00413166 | APL | ATRA, As2O3, Idarubicin | II |

| NCT01409161 | APL | ATRA, As2O3, Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, Methylprednisolone | I |

| NCT00903422 | AML, MDS | Eltrombopag olamine, platelet transfusions, mild chemo, cytokines, VPA, ATRA, ESAs or G-CSF | I |

| NCT00528450 | APL | As2O3, Idarubicin, Tretinoin | II |

| NCT00002701 | APL | Busulfan, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, etoposide, idarubicin, mercaptopurine, methotrexate, mitoxantrone hydrochloride, thioguanine, tretinoin, allogeneic/ autologous bone marrow transplantation, radiation therapy | III |

| NCT00465933 | APL | ATRA, Idarubicin | IV |

| NCT00675870 | APL | NRX 195183 synthetic retinoid | II |

| NCT00180128 | APL | ATRA, idarubicin, mitoxantrone, daunorubicin, cytarabine | IV |

| NCT01404949 | APL | Tretinoin, As2O3, | II |

| NCT01226303 | APL | ATRA, Idarubicin | III |

| NCT00520208 | APL (relapsed/refractory) | Tamibarotene (AM80) | II |

| NCT00985530 | APL | Tamibarotene, As2O3 | I |

| NCT00504764 | APL (relapsed) | As2O3, ATRA, Autologous/Allogenic transplantation, As2O3 | IV |

| NCT00196768 | APL (relapsed) | IV |

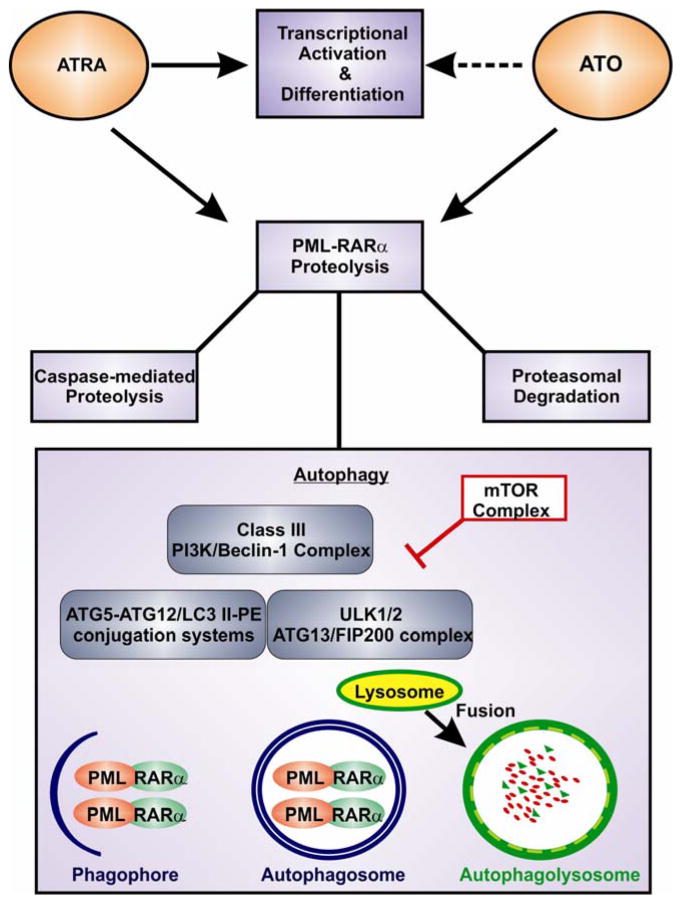

The specificity of ATRA for APL lies in its effect on the RARα-fusion oncoprotein. Pharmacologic doses of ATRA induce a conformational change in PML-RARα, resulting in the dissociation of HDACs and DNMTs 73. This allows the recruitment of co-activator complexes and restoration of retinoid target gene transcription, including the transcription of those genes involved in granulocytic differentiation 88 (Figure 3). ATRA also induces the degradation of the PML-RARα oncoprotein itself through several non-overlapping, co-operating proteolytic mechanisms (Figure 4). Upon ATRA treatment, caspase-3 targets a cleavage site within the α-helix of PML, leaving an intact RARα moiety of the PML-RARα protein 89. ATRA activates the ubiquitin/proteasome system (UPS) through the phosphorylation of serine-873 on PML-RARα 90 and also via the binding of SUG-1 to the RARα transactivation domain 91. Both caspase inhibitors and proteasomal inhibitors interfere with PML-RARα degradation 92. Most recently, the cellular process of autophagy has been proposed as another important pathway in the catabolism of the PML-RARα oncoprotein. Ablain and colleagues have reported that synthetic retinoids capable of re-activating transcription in PML-RARα positive leukemic cells but with no effects on PML-RAR protein levels, successfully induce differentiation but fail to eliminate the leukemia-initiating activity of transplanted clones in vivo 93. This establishes two distinct mechanisms of therapeutic action exerted by ATRA (Figure 4) and emphasizes the importance of oncoprotein proteolysis in achieving long-term cure. This is the subject of a recent comprehensive review by Dos Santos and colleagues 94.

Figure 4. Therapeutic mechanisms of ATRA and Arsenic Trioxide (ATO) in PML-RARα positive acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).

Therapeutic concentrations of ATRA de-repress transcription and lead to the myeloid differentiation of APL cells with a transient hematologic remission of the disease. ATO also encourages partial differentiation. Both agents have a distinct action of promoting PML-RARα proteolysis through co-operating mechanisms, caspase-mediated degradation, proteasomal degradation and autophagy. Autophagy is a catabolic process capable of digesting large proteins aggregates, using the lysosomal machinery. Upon autophagy activation, the ULK1/2 kinase complex recruits the Class III PI3K/Beclin-1 complex and series of conjugation reactions involving the complex’s ATG5, ATG7, ATG10, ATG12 and ATG8/LC3 ensue. This initiates formation of a double membrane known as the ‘phagophore’. As this expands it becomes an enclosed double membraned vesicle known as an ‘autophagosome’. This sequesters aggregated proteins for degradation – such as PML-RARα. Lysosomal fusion with autophagosomes results in the proteolysis of their contents. mTOR is a negative regulator of autophagy as it phosphorylates and suppresses the ULK1/2 kinase complex. AMPK (not shown) is an activator of the ULK kinase complex.

The majority of patients receiving ATRA monotherapy will eventually relapse. This may result from incomplete clearance of leukemia initiating cells (LICs) residing in the bone marrow or from the proliferation of ligand binding domain (LBD)-mutated leukemic clones naturally selected during ATRA induction therapy 88,94. A proportion of PML-RARα fusion APL patients are clinically resistant even to initial ATRA therapy. This may result from genetic mutations in the LBD of the RARα moiety that induce conformational changes in the protein, interfering with co-repressor release and reducing the affinity of ATRA binding 95. Increased intracellular catabolism of ATRA, leading to decreased nuclear bioavailabilty, is another possible mechanism of acquired resistance of particular concern in patients treated with ATRA over a long duration 96. Despite retaining functional RARα LBDs, certain X-RARα APL subtypes - particularly PLZF-RARα and STAT5b-RARα fusions, also display a clinical ATRA resistance 88. One proposed explanation for this is that the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex interacts with very high affinity such that even pharmacologic doses of ATRA cannot induce transcriptional de-repression 97.

Arsenic Trioxide (ATO) was first reported to have an anti-leukemic effect on APL cells in 1996 98. It has since proved to be a valuable first line therapy for the condition, attaining single-agent cure rates of 70% and >90% when administered in combination with ATRA 99,100. A recently published clinical trial reported non-inferior outcomes with an ATRA/ATO regimen compared to the now conventional ATRA/anthracycline-based regimen in low and intermediate risk disease, facilitating the potential unprecedented treatment of an acute leukemia without toxic chemotherapy 101. Improved outcomes have also been observed with the inclusion of ATO in the treatment of relapsed or resistant disease, and ATO now forms the backbone of salvage regimens 83. Phenotypically ATO induces partial differentiation of APL cells at low doses and apoptotic cell death at higher concentrations 102. ATO promotes degradation of the PML-RARα fusion oncoprotein with the effect of depleting LICs, resulting in long-term disease remission 90 (Figure 4). Interestingly, ATO potently induces autophagy in cultured leukemic cells and both pharmacological and genetic autophagy inhibition reverses the anti-leukemic effect of ATO 103.

Autophagy

Autophagy is a ubiquitous cellular pathway involved in protein turnover 104. Cytoplasmic material tagged for autophagic degradation is sequestered within double-membrane vesicles known as ‘autophagosomes’. These vesicles then traffic to and fuse with lysosomes, where their contents are degraded by resident hydrolases to yield reusable monomers 105 (Figure 4). Initial studies in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae identified a family of ‘AuTophaGy-related’ (ATG) proteins that form the core molecular machinery of autophagy 106. These proteins are hierarchically recruited to regulate each step in the autophagic process: autophagosome initiation, elongation, maturation, docking, fusion and degradation. The mechanisms underpinning autophagy have been reviewed excellently elsewhere 107,108.

The serine/threonine kinase mammalian target of rapmaycin (mTOR) serves as a cytoplasmic master negative regulator of autophagy, phosphorylating and inactivating proteins of the ULK1-ULK2-ATG13-FIP200 complex, an essential component in autophagy induction 107,109. mTOR integrates signals from multiple cellular signaling and nutrient-sensing pathways and activates autophagy in times of cellular stress or growth factor deprivation. Several mTOR inhibitors have been developed and are in clinical use, with the proven effect of autophagy induction (e.g. rapamycin, everolimus, temsirolimus) 107,110. Autophagy can also be induced in an mTOR-independent manner via (i) the direct activation of ULK1 by adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and (ii) the lowering of cytosolic myo-inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) levels – as is observed with pharmacologic lithium treatment 111. The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) leucine zipper transcription factor EB (TFEB) has recently been identified as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy, entering the nucleus upon autophagy initiation to activate the transcription of at least 17 autophagy-related genes 112. Other transcription factors known to activate autophagy gene expression include NF-κB, E2F1, HIF-1α, and FOXO3 107,113,114.

Mammalian cell differentiation often involves structural remodeling and requires tight control of protein turnover. Autophagy is observed in murine oocytes within 4 hours of fertilization, with deletion of the essential autophagy gene ATG5 resulting in embryonic lethality prior to implantation115. Autophagy has also been observed in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) induced to differentiate in culture 116. As recently reviewed by Guan and colleagues, autophagy is important in maintaining hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) quiescence and is highly active during hematoopoietic cell differentiation 41. GATA-1, a master regulator of hematopoiesis, directly activates the transcription of the ATG8 gene family 117. The elimination of mitochondria in developing reticulocytes is mediated by mitophagy, with severe functional red cell defects resulting due to loss of the autophagy genes ULK1, ATG7 or BNIPL3 118. Specific roles for autophagy have also been identified in lymphocyte, monocyte-macrophage, and plasma cell differentiation 119,120.

Defective autophagy has been linked to tumour development in several cancer models. Beclin1 is often mono-allelically deleted in solid tumour malignancies 121. Tumours with constitutive activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway display decreased autophagy 122. FIP200, a member of the ULK1-ULK2-ATG13-FIP200 autophagy initiation complex (Figure 4), is required for the maintenance of fetal HSCs, with conditional knockout in murine study leading to severe anemia and perinatal lethality 123. Further in vivo study has shown that the conditional knockdown of ATG7 in murine HSCs results in a severe myeloproliferative syndrome with dysplastic features and early death 124. Autophagy interacts at multiple levels with apoptotic signaling pathways and may itself contribute to programmed cell death in cancer cells 125. Thus, promoting autophagy represents a novel avenue of cancer therapeutics for both solid and hematologic malignancies.

Autophagy in APL cell differentiation

Human myeloid leukemic cell lines and human primary monocytes treated with ATRA in culture display increased levels of autophagy 126–128. Studies on the NB4 human PML-RARα positive APL cell line have shown that this ATRA-induced autophagy is necessary for the successful granulocytic differentiation of malignant cells 127–129. Autophagy has specifically been linked to the breakdown of the PML-RARα oncoprotein 127,128. The molecular mechanisms through which ATRA induces autophagy are poorly understood and will hopefully be explored in future studies. Isakson and colleagues proposed that the activation of autophagy is mTOR-dependent and showed that mTOR inhibition with rapamycin increases autophagy and promotes PML-RARα degradation 128. As a transcriptional regulator, ATRA may also promote autophagy at a nuclear level through the activation of transcription factors known to up-regulate the autophagic process 130. ATRA may also have a biologic role in autophagosome maturation through the redistribution of a cation-dependent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (CIMPR) to the developing autophagosome, leading to vesicle acidification. This effect is thought to be independent of nuclear hormone receptors and instead to be mediated by direct binding of ATRA to CIMPR 131. A recent study indicates that ATO induces autophagy via the induction of MEK/ERK signaling independently of the mTOR autophagy-signaling axis 103. A similar role for autophagy in oncoprotein elimination has been shown in BCR-ABL fusion chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), where imatinib has the dual effects of inhibiting the tyrosine kinase activity of BCR-ABL and inducing its autophagic degradation 132. It is worth noting that autophagy was not shown to have a role in the turnover of the AML1-ETO fusion oncoprotein, instead enhancing the survival of malignant cells in culture 133. Thus it is possible that autophagy is involved in the breakdown of large, aggregate forming oncogenic fusion proteins such as PML-RARα and BCR-ABL. Further research will clarify this point.

Conclusions

Chromosomal translocations in hematopoietic cells involving the RARα gene lead to impaired retinoid signaling and a differentiation block, causing APL. In nine documented RARα fusion variants, the translocation within the RARα gene occurs at the same genomic location, proximal to RARα binding in NB4 cells (Figure 2). While the potential role for retinoid nuclear receptors in the initiation of chromosomal translocations involving the RARα gene remains to be confirmed, such a mechanistic link has been identified between AR signaling and chromosomal translocations in prostate cancer 69–71.

While pharmacologic doses of ATRA can restore retinoid-induced transcription and myeloid differentiation in APL, the elimination of RARα oncogenic fusion proteins is critical for sustained remissions and long-term cure 93. This proteolysis is likely to be one of the integral mechanisms through which ATRA and ATO exert their clinically proven anti-leukemic efficacy in APL 101 (Figure 4). Autophagy is the predominant cellular pathway utilized in the disposal of large aggregate-prone proteins and is likely to be critical for RARα fusion protein degradation. Both ATRA and ATO induce autophagy through mechanisms which have not been fully elucidated. Pharmacologic induction or enhancement of autophagy in combination with established therapies ATRA and ATO may provide a means of overcoming treatment resistance in APL, either through improved oncoprotein elimination or through driving the cellular remodeling necessary for cellular differentiation. This may also hold promise to broaden the application of differentiation therapy to non-APL fusion leukemias.

Highlights.

Normal and aberrant retinoid signaling in hematopoiesis and leukemia is reviewed

We suggest a novel role for RARα in the development of X-RARα gene fusions in APL

ATRA therapy in APL activates transcription and promotes onco-protein degradation

Autophagy may be involved in both onco-protein degradation and differentiation

Pharmacologic autophagy induction may potentiate ATRA’s therapeutic effects

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Gudas Laboratory, Weill Cornell Medical College, NY and Cork Cancer Research Centre, University College Cork, Ireland for critical discussion. We are grateful to Dr. Michelle Nyhan for help in editing. Dr. Nina Orfali is funded by the Haematology Education and Research Trust (H.E.R.O), Cork, Ireland with unrestricted educational supporting bursaries from Pfizer, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis and Amgen. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the University of Nottingham, Weill Cornell, and NIHRO1CA43796 to LJG.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No competing financial interests exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tang XH, Gudas LJ. Retinoids, retinoic acid receptors, and cancer. Annual review of pathology. 2011;6:345–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.David KA, Mongan NP, Smith C, Gudas LJ, Nanus DM. Phase I trial of ATRA-IV and depakote in patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies. Cancer biology & therapy. 2010;9:678–684. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.9.11436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boorjian SA, et al. Phase 1/2 clinical trial of interferon alpha2b and weekly liposome-encapsulated all-trans retinoic acid in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother (1997) 2007;30:655–662. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31805449a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mongan NP, Gudas LJ. Diverse actions of retinoid receptors in cancer prevention and treatment. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2007;75:853–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2007.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Byrne SM, Blaner WS. Retinol and retinyl esters: biochemistry and physiology: Thematic Review Series: Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Vitamin A. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54:1731–1743. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R037648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Q, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry DC, Jin H, Majumdar A, Noy N. Signaling by vitamin A and retinol-binding protein regulates gene expression to inhibit insulin responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:4340–4345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011115108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marwarha G, Berry DC, Croniger CM, Noy N. The retinol esterifying enzyme LRAT supports cell signaling by retinol-binding protein and its receptor STRA6. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014;28:26–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-234310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muenzner M, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and its membrane receptor STRA6 control adipogenesis by regulating cellular retinoid homeostasis and retinoic acid receptor alpha activity. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33:4068–4082. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00221-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry DC, et al. The STRA6 receptor is essential for retinol-binding protein-induced insulin resistance but not for maintaining vitamin A homeostasis in tissues other than the eye. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:24528–24539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawaguchi R, et al. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amengual J, Golczak M, Palczewski K, von Lintig J. Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase is critical for cellular uptake of vitamin A from serum retinol-binding protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:24216–24227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germain P, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXIII. Retinoid X receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2006;58:760–772. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germain P, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LX. Retinoic acid receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2006;58:712–725. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie R, Gudas L. RAR isotype specificity in F9 teratocarcinoma stem cells results from the differential recruitment of coregulators to retinoic acid response elements. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:33421–33434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704845200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giguere V, Ong ES, Segui P, Evans RM. Identification of a receptor for the morphogen retinoic acid. Nature. 1987;330:624–629. doi: 10.1038/330624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brand N, et al. Identification of a second human retinoic acid receptor. Nature. 1988;332:850–853. doi: 10.1038/332850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krust A, Kastner P, Petkovich M, Zelent A, Chambon P. A third human retinoic acid receptor, hRAR-gamma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:5310–5314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin AA, et al. 9-cis retinoic acid stereoisomer binds and activates the nuclear receptor RXR alpha. Nature. 1992;355:359–361. doi: 10.1038/355359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heyman RA, et al. 9-cis retinoic acid is a high affinity ligand for the retinoid X receptor. Cell. 1992;68:397–406. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90479-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Privalsky ML. Heterodimers of retinoic acid receptors and thyroid hormone receptors display unique combinatorial regulatory properties. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:863–878. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michalik L, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2006;58:726–741. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Germain P, Iyer J, Zechel C, Gronemeyer H. Co-regulator recruitment and the mechanism of retinoic acid receptor synergy. Nature. 2002;415:187–192. doi: 10.1038/415187a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn YC, et al. Dynamic inhibition of nuclear receptor activation by corepressor binding. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:366–372. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perissi V, et al. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes & development. 1999;13:3198–3208. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377:454–457. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westin S, et al. Interactions controlling the assembly of nuclear-receptor heterodimers and co-activators. Nature. 1998;395:199–202. doi: 10.1038/26040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy L, et al. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rochel N, et al. Common architecture of nuclear receptor heterodimers on DNA direct repeat elements with different spacings. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;18:564–570. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yao TP, Ku G, Zhou N, Scully R, Livingston DM. The nuclear hormone receptor coactivator SRC-1 is a specific target of p300. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shao W, et al. Ligand-inducible interaction of the DRIP/TRAP coactivator complex with retinoid receptors in retinoic acid-sensitive and -resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2000;96:2233–2239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epping MT, et al. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White KA, et al. Negative feedback at the level of nuclear receptor coregulation. Self-limitation of retinoid signaling by RIP140. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:43889–43892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei LN, Farooqui M, Hu X. Ligand-dependent formation of retinoid receptors, receptor-interacting protein 140 (RIP140), and histone deacetylase complex is mediated by a novel receptor-interacting motif of RIP140. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:16107–16112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010185200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laursen KB, et al. Polycomb recruitment attenuates retinoic acid-induced transcription of the bivalent NR2F1 gene. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:6430–6443. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudas LJ. Retinoids and vertebrate development. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:15399–15402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laursen KB, Wong PM, Gudas LJ. Epigenetic regulation by RARalpha maintains ligand-independent transcriptional activity. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:102–115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kashyap V, Gudas LJ. Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms distinguish retinoic acid-mediated transcriptional responses in stem cells and fibroblasts. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:14534–14548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kashyap V, et al. Epigenomic reorganization of the clustered Hox genes in embryonic stem cells induced by retinoic acid. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:3250–3260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Systems biology and medicine. 2010;2:640–653. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guan JL, et al. Autophagy in stem cells. Autophagy. 2013;9:830–849. doi: 10.4161/auto.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oren T, Sher JA, Evans T. Hematopoiesis and retinoids: development and disease. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2003;44:1881–1891. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000116661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purton LE, Bernstein ID, Collins SJ. All-trans retinoic acid enhances the long-term repopulating activity of cultured hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2000;95:470–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purton LE, et al. RARgamma is critical for maintaining a balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1283–1293. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghatpande S, Ghatpande A, Sher J, Zile MH, Evans T. Retinoid signaling regulates primitive (yolk sac) hematopoiesis. Blood. 2002;99:2379–2386. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross AC. Vitamin A and retinoic acid in T cell-related immunity. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;96:1166S–1172S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.034637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones RJ, et al. Characterization of mouse lymphohematopoietic stem cells lacking spleen colony-forming activity. Blood. 1996;88:487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park DJ, et al. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein epsilon is a potential retinoid target gene in acute promyelocytic leukemia treatment. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1999;103:1399–1408. doi: 10.1172/JCI2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mueller BU, et al. ATRA resolves the differentiation block in t(15;17) acute myeloid leukemia by restoring PU.1 expression. Blood. 2006;107:3330–3338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kastner P, et al. Positive and negative regulation of granulopoiesis by endogenous RARalpha. Blood. 2001;97:1314–1320. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collins SJ. The role of retinoids and retinoic acid receptors in normal hematopoiesis. Leukemia. 2002;16:1896–1905. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasserjian RP. Acute myeloid leukemia: advances in diagnosis and classification. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2013;35:358–366. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuhnl A, Grimwade D. Molecular markers in acute myeloid leukaemia. International journal of hematology. 2012;96:153–163. doi: 10.1007/s12185-012-1123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Estey EH. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2013 update on risk-stratification and management. American journal of hematology. 2013;88:318–327. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nowak D, Stewart D, Koeffler HP. Differentiation therapy of leukemia: 3 decades of development. Blood. 2009;113:3655–3665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-198911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de The H, Chomienne C, Lanotte M, Degos L, Dejean A. The t(15;17) translocation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia fuses the retinoic acid receptor alpha gene to a novel transcribed locus. Nature. 1990;347:558–561. doi: 10.1038/347558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borrow J, Goddard AD, Sheer D, Solomon E. Molecular analysis of acute promyelocytic leukemia breakpoint cluster region on chromosome 17. Science. 1990;249:1577–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.2218500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choudhry A, DeLoughery TG. Bleeding and thrombosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia. American journal of hematology. 2012;87:596–603. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamamoto Y, et al. BCOR as a novel fusion partner of retinoic acid receptor alpha in a t(X;17)(p11; q12) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:4274–4283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Won D, et al. OBFC2A/RARA: a novel fusion gene in variant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:1432–1435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Z, et al. Fusion between a novel Kruppel-like zinc finger gene and the retinoic acid receptor-alpha locus due to a variant t(11;17) translocation associated with acute promyelocytic leukaemia. The EMBO journal. 1993;12:1161–1167. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05757.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Redner RL, Rush EA, Faas S, Rudert WA, Corey SJ. The t(5;17) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia expresses a nucleophosmin-retinoic acid receptor fusion. Blood. 1996;87:882–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wells RA, Catzavelos C, Kamel-Reid S. Fusion of retinoic acid receptor alpha to NuMA, the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein, by a variant translocation in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature genetics. 1997;17:109–113. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arnould C, et al. The signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT5b gene is a new partner of retinoic acid receptor alpha in acute promyelocytic-like leukaemia. Human molecular genetics. 1999;8:1741–1749. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.9.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Catalano A, et al. The PRKAR1A gene is fused to RARA in a new variant acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:4073–4076. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kondo T, et al. The seventh pathogenic fusion gene FIP1L1-RARA was isolated from a t(4;17)-positive acute promyelocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2008;93:1414–1416. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tomlins SA, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bastus NC, et al. Androgen-induced TMPRSS2:ERG fusion in nonmalignant prostate epithelial cells. Cancer research. 2010;70:9544–9548. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mani RS, et al. Induced chromosomal proximity and gene fusions in prostate cancer. Science. 2009;326:1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1178124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin C, et al. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell. 2009;139:1069–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martens JH, et al. PML-RARalpha/RXR Alters the Epigenetic Landscape in Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. Cancer cell. 2010;17:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Croce L, et al. Methyltransferase recruitment and DNA hypermethylation of target promoters by an oncogenic transcription factor. Science. 2002;295:1079–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.1065173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou J, et al. Dimerization-induced corepressor binding and relaxed DNA-binding specificity are critical for PML/RARA-induced immortalization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9238–9243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603324103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lengfelder E, Hofmann WK, Nolte F. Management of elderly patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: progress and problems. Annals of hematology. 2013;92:1181–1188. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1788-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grignani F, et al. Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-alpha recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1998;391:815–818. doi: 10.1038/35901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Collins SJ. Retinoic acid receptors, hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Current opinion in hematology. 2008;15:346–351. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283007edf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Arrowsmith CH, Bountra C, Fish PV, Lee K, Schapira M. Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2012;11:384–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Breitman TR, Selonick SE, Collins SJ. Induction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1980;77:2936–2940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Breitman TR, Collins SJ, Keene BR. Terminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemic cells in primary culture in response to retinoic acid. Blood. 1981;57:1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang ME, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1988;72:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tallman MS, et al. All-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia: long-term outcome and prognostic factor analysis from the North American Intergroup protocol. Blood. 2002;100:4298–4302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang ZY, Chen Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 2008;111:2505–2515. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schlenk RF, et al. Gene mutations and response to treatment with all-trans retinoic acid in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Results from the AMLSG Trial AML HD98B. Haematologica. 2009;94:54–60. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Estey EH, et al. Randomized phase II study of fludarabine + cytosine arabinoside + idarubicin +/− all-trans retinoic acid +/− granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in poor prognosis newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 1999;93:2478–2484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nazha A, et al. The Addition of All-Trans Retinoic Acid to Chemotherapy May Not Improve the Outcome of Patient with NPM1 Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:218. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burnett AK, et al. The impact on outcome of the addition of all-trans retinoic acid to intensive chemotherapy in younger patients with nonacute promyelocytic acute myeloid leukemia: overall results and results in genotypic subgroups defined by mutations in NPM1, FLT3, and CEBPA. Blood. 2010;115:948–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tomita A, Kiyoi H, Naoe T. Mechanisms of action and resistance to all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide (As2O 3) in acute promyelocytic leukemia. International journal of hematology. 2013;97:717–725. doi: 10.1007/s12185-013-1354-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nervi C, et al. Caspases mediate retinoic acid-induced degradation of the acute promyelocytic leukemia PML/RARalpha fusion protein. Blood. 1998;92:2244–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nasr R, et al. Eradication of acute promyelocytic leukemia-initiating cells through PML-RARA degradation. Nature medicine. 2008;14:1333–1342. doi: 10.1038/nm.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.vom Baur E, et al. Differential ligand-dependent interactions between the AF-2 activating domain of nuclear receptors and the putative transcriptional intermediary factors mSUG1 and TIF1. The EMBO journal. 1996;15:110–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshida H, et al. Accelerated degradation of PML-retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML-RARA) oncoprotein by all-trans-retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia: possible role of the proteasome pathway. Cancer research. 1996;56:2945–2948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ablain J, et al. Uncoupling RARA transcriptional activation and degradation clarifies the bases for APL response to therapies. J Exp Med. 2013;210:647–653. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dos Santos GA, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. Synergy against PML-RARa: targeting transcription, proteolysis, differentiation, and self-renewal in acute promyelocytic leukemia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:2793–2802. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fung TK, So EC. Overcoming treatment resistance in acute promyelocytic leukemia and beyond. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1128–1129. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muindi J, et al. Continuous treatment with all-trans retinoic acid causes a progressive reduction in plasma drug concentrations: implications for relapse and retinoid “resistance” in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 1992;79:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.He LZ, et al. Distinct interactions of PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha with co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nature genetics. 1998;18:126–135. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen GQ, et al. In vitro studies on cellular and molecular mechanisms of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: As2O3 induces NB4 cell apoptosis with downregulation of Bcl-2 expression and modulation of PML-RAR alpha/PML proteins. Blood. 1996;88:1052–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ghavamzadeh A, et al. Phase II study of single-agent arsenic trioxide for the front-line therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2753–2757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Estey E, et al. Use of all-trans retinoic acid plus arsenic trioxide as an alternative to chemotherapy in untreated acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:3469–3473. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lo-Coco F, et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369:111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen GQ, et al. Use of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): I. As2O3 exerts dose-dependent dual effects on APL cells. Blood. 1997;89:3345–3353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goussetis DJ, et al. Autophagy is a critical mechanism for the induction of the antileukemic effects of arsenic trioxide. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:29989–29997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen Y, Klionsky DJ. The regulation of autophagy - unanswered questions. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:161–170. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:1845–1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1303158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2009;10:458–467. doi: 10.1038/nrm2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annual review of genetics. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Current opinion in cell biology. 2010;22:124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Molecular cell. 2010;40:280–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nature chemical biology. 2011;7:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Palmieri M, et al. Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways. Human molecular genetics. 2011;20:3852–3866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhang H, et al. Mitochondrial autophagy is an HIF-1-dependent adaptive metabolic response to hypoxia. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:10892–10903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800102200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 114.Polager S, Ofir M, Ginsberg D. E2F1 regulates autophagy and the transcription of autophagy genes. Oncogene. 2008;27:4860–4864. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tsukamoto S, et al. Autophagy is essential for preimplantation development of mouse embryos. Science. 2008;321:117–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1154822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tra T, et al. Autophagy in human embryonic stem cells. PloS one. 2011;6:e27485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kang YA, et al. Autophagy driven by a master regulator of hematopoiesis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2012;32:226–239. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06166-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yousefi S, Simon HU. Autophagy in cells of the blood. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1793:1461–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Conway KL, et al. ATG5 regulates plasma cell differentiation. Autophagy. 2013;9 doi: 10.4161/auto.23484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang Y, Morgan MJ, Chen K, Choksi S, Liu ZG. Induction of autophagy is essential for monocyte-macrophage differentiation. Blood. 2012;119:2895–2905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:15077–15082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2436255100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liu F, et al. FIP200 is required for the cell-autonomous maintenance of fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116:4806–4814. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mortensen M, et al. The autophagy protein Atg7 is essential for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:455–467. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Su M, Mei Y, Sinha S. Role of the Crosstalk between Autophagy and Apoptosis in Cancer. Journal of oncology. 2013;2013:102735. doi: 10.1155/2013/102735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Trocoli A, et al. ATRA-induced upregulation of Beclin 1 prolongs the life span of differentiated acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Autophagy. 2011;7:1108–1114. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang Z, et al. Autophagy regulates myeloid cell differentiation by p62/SQSTM1-mediated degradation of PML-RARalpha oncoprotein. Autophagy. 2011;7:401–411. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.4.14397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Isakson P, Bjoras M, Boe SO, Simonsen A. Autophagy contributes to therapy-induced degradation of the PML/RARA oncoprotein. Blood. 2010;116:2324–2331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-261040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Brigger D, Torbett BE, Chen J, Fey MF, Tschan MP. Inhibition of GATE-16 attenuates ATRA-induced neutrophil differentiation of APL cells and interferes with autophagosome formation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;438:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Fullgrabe J, Klionsky DJ, Joseph B. The return of the nucleus: transcriptional and epigenetic control of autophagy. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2014;15:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rajawat Y, Hilioti Z, Bossis I. Retinoic acid induces autophagosome maturation through redistribution of the cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;14:2165–2177. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Elzinga BM, et al. Induction of autophagy by Imatinib sequesters Bcr-Abl in autophagosomes and down-regulates Bcr-Abl protein. American journal of hematology. 2013;88:455–462. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Torgersen ML, Engedal N, Boe SO, Hokland P, Simonsen A. Targeting autophagy potentiates the apoptotic effect of histone deacetylase inhibitors in t(8;21) AML cells. Blood. 2013;122:2467–2476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]