Abstract

Flight behavior of insecticide-resistant and susceptible malaria mosquitoes approaching deltamethrin-treated nets was examined using a wind tunnel. Behavior was linked to resulting health status (dead or alive) using comparisons between outcomes from free-flight assays and standard World Health Organization (WHO) bioassays. There was no difference in response time, latency time to reach the net, or spatial distribution in the wind tunnel between treatments. Unaffected resistant mosquitoes spent less time close to (< 30 cm) treated nets. Nettings that caused high knockdown or mortality in standard WHO assays evoked significantly less mortality in the wind tunnel; there was no excitorepellent effect in mosquitoes making contact with the nettings in free flight. This study shows a new approach to understanding mosquito behavior near insecticidal nets. The methodology links free-flight behavior to mosquito health status on exposure to nets. The results suggest that behavioral assays can provide important insights for evaluation of insecticidal effects on disease vectors.

Background

Insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) have been the recommended strategy for the prevention of malaria since 2005, and widespread use of ITNs, coupled with accurate case management, has led to a significant reduction in malaria morbidity and mortality.1,2 Synthetic pyrethroids are the only insecticide class currently approved for use on bed nets, mainly because of their relatively low mammalian toxicity, low costs, high residual efficacy, applicability to long-lasting technology, and fast killing effect on mosquitoes. Numerous studies have shown their strong protective effect against bites of infectious malaria mosquitoes.3–6 Pyrethroids, especially permethrin and deltamethrin (two of the most widely used insecticides on bed nets), are also reported to have a repellent effect.7–11 However, these (excito-) repellent properties of ITNs are often assumed based on experimental hut studies, and quantified data on mosquito flight behavior are lacking.12–17

There can be different interpretations of the term excitorepellency or contact irritancy18–21; for this paper, we follow the description of an excitorepellent by White,21 which is in line with that of a contact irritant: the power of a chemical, especially though by brief tarsal exposure, to irritate the insect sufficiently that it moves away before knockdown, even from sublethal exposure.18–21 Some studies report mosquito avoidance behavior to pyrethroid-treated bed nets but with no clear observation of a repellent effect.22,23 However, others report repellent effects of deltamethrin after the application as an indoor residual spray (IRS).24 Experimental hut studies suggest a repellent effect of pyrethroid-treated bed nets to Anolpheles gambiae based on reduced hut entries or forced exit. Current designs of experimental huts do not provide the possibility to study close-range behavior in detail.13,25

World Health Organization (WHO) tunnel tests measure whether mosquitoes will pass a treated net, but they do not measure flight behavior during their approach to the net.26 WHO guidelines propose to use a guinea pig as bait for An. gambiae mosquitoes, but for studying host-seeking responses in relation to treated nets, it seems more applicable to use human bait for studying the anthropophilic mosquito An. gambiae.27

The present study was undertaken to assess the close-range behavior of the malaria mosquito An. gambiae when exposed to insecticide-treated netting in a wind tunnel. The host-seeking behavior of insecticide-susceptible and -resistant mosquitoes was recorded by video cameras while the mosquitoes flew upwind to human odorants shielded from the mosquitoes by insecticide-treated netting. Recorded flight behaviors were linked to individual mosquito health status (i.e., dead or alive) after exposure to the nets. The bioefficacy of the nets was validated by comparing the wind tunnel data of free-flying mosquitoes with that of standard WHO bioassays for insecticide-treated materials.

Material and Methods

Mosquitoes.

The Wageningen laboratory strain of An. gambiae Giles sensu stricto var. Suakoko was used as well as a resistant strain of An. gambiae (VKPR) that originated from Burkina Faso. The Suakoko mosquito strain is 100% susceptible to pyrethroids, and the VKPR strain (insecticide susceptibility profile is available from the authors) is pyrethroid-resistant and homozygous for the kdr mutation L1014F. Both strains were kept in 30 × 30 × 30-cm cages at 27°C ± 1°C at a relative humidity of 70% ± 5% with a 12:12-hour light regimen. Adults were provided with a 6% glucose solution ad libitum, and females were bloodfed using a membrane feeding system by Hemotek (Discovery Workshop, Accrington, United Kingdom). Human blood was obtained from the Sanquin blood bank, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, where it had been donated by volunteers. Larvae were reared in 1.5-L trays filled with tap water and fed Tetramin (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany) fish food.

Wind tunnel and automated tracking.

Conditioned air (27°C ± 1°C and relative humidity of 70% ± 5%) was blown into a wind tunnel (160 × 60 × 60 cm) with a flow rate of 10 cm/second. The side walls and floor of the arena were constructed of black recycled polycarbonate, and the ceiling was made of transparent Lexan polycarbonate (WSV Kunststoffen, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The wind tunnel was illuminated from the downwind side using Four Tracksys (Nottingham, United Kingdom) infrared light units. Each unit contained an array of 90 infrared light-emitting diodes (LEDs) emitting light with peak output at 880 nm. To optimize the contrast of the illuminated mosquito wings against the background, another four infrared lights containing 168 LEDs (> 920 nm) each (Reinaert Electronics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were added in the same line as the Tracksys infrared lights. The experimental room was illuminated using a 15-Watt light bulb facing away from the test arena to provide visual feedback during flight. Mosquitoes approaching within 60 cm of the netting were recorded using a Cohu 4722-2000/0000 monochrome CCD camera (Cohu, San Diego, CA) equipped with a Fuji Non-TV f1.4 9-mm lens. An Ikegami camera (IR49E B/W) with a wide-angle lens (LM3NCM Mp KOWA 3, 5/f2.4 C-Mount) was used to obtain a view over the entire flight arena (Figure 1). The position of a mosquito in the arena was tracked offline using Ethovision XT 7 (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the wind tunnel. Air inlet (AI), lamination screen (LS), glass funnel containing heat element (F), mesh screen (S), framed net (FN), release cup (RC), cameras (C1 and C2), and infrared lights types 1 (IR1) and 2 (IR2) are shown.

Tested nets.

Coded netting samples were received from Vestergaard Frandsen SA (Lausanne, Switzerland) and tested in a double-blind fashion. For tracking optimization, black nets were used. The samples were kept strictly separate in aluminum bags (Lifesystems, United Kingdom). The netting codes were revealed at the end of the experimental phase. The nets consisted of black untreated polyester, black polyester coated with deltamethrin (1.8 g/kg; deltamethrin netting), and black polyethylene incorporated with deltamethrin at 4 g/kg and piperonyl butoxide (PBO) at 25 g/kg (deltamethrin + PBO netting). Netting samples were mounted on a square frame of black polycarbonate that fit tightly in the 60 × 60-cm wind tunnel; in this way, 50 × 50 cm of fabric could be exposed to the mosquitoes. A strip of door brush fixed the netting to the frame and prevented scratches to the walls. To ensure that the wind tunnel could not be accidentally contaminated with residues of insecticides, the netting was placed 10 cm from the upwind end of the tunnel and did not touch the walls of the arena. The odor source to which mosquitoes were exposed consisted of a nylon stocking (worn for 24 hours), which was supplemented by carbon dioxide released at 250 mL/minute.28,29 The nylon stocking was placed over a 34°C heat source to enhance odorant release and simulate the odor of human skin. The odor source and heating system were placed behind the center of the upwind screen out of reach of the mosquito.

Experimental procedures.

Individual female mosquitoes, aged 5–7 days, were placed in a plastic release container (diameter = 5 cm, height = 3 cm) with a piece of wet cotton 13 to 16 hours before the start of the experiment. Wind tunnel tests were performed during the last 4 hours of the scotophase. The nettings were tested using a Latin square design and switched after four to six replicates per testing day. Surgical gloves were worn and replaced with each treatment. In between experiments, the framed nets were stored in aluminum bags. The release container was placed at the downwind end of the arena and remained closed for 1 minute. The mosquito release system was operated from an adjacent room to avoid the effects of other human odors during the experiment. After release, 3 minutes were allowed for upwind flight response. The response time was recorded and defined as the time in seconds between release and the first appearance within the arena. If mosquitoes entered the flight arena, their flights were recorded for 5 minutes. Directly thereafter, mosquitoes were removed from the wind tunnel using a manual aspirator and transferred to labeled 50-mL cylindrical tubes covered with netting and damp cotton wool with a 6% sugar solution. Knockdown status was measured after 60 minutes, and survival status was measured at 22–24 hours after the experiment. The wind tunnel was cleaned weekly using cotton wool and a 10% alcohol solution.

WHO cone and tube tests.

Standard 3-minute WHO cone and tube assays were performed with unfed An. gambiae s.s. (both susceptible and resistant strains) in the same age group used for the wind tunnel test (5–7 days old).26,30 Two groups of five female mosquitoes were tested in each tube or cone, with a minimum of seven replicates per treatment. After exposure to the netting inside the cone or tube, both groups of mosquitoes were placed in a single 1-L cup and provided with 6% glucose solution ad libitum. Their knockdown status was measured 60 minutes post-exposure, and mortality was recorded at 24 hours. These data were used for comparison with survival and mortality in the wind tunnel bioassay.

Data analyses.

Data were analyzed using Ethovision XT 7 (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands; http://www.noldus.com). Five different zones were allocated to the flight arena (Table 1), and a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to examine differences in the mean time spent per zone between treatments. Post-hoc analyses (multiple comparison, Scheffe) were done to reveal significant differences between nets. A threshold for mobile or immobile mosquitoes was set at > 19 and < 17 mm/second, respectively. Parameters studied were (1) response (the percentage of responding mosquitoes and the time until response as well as the latency time until first contact with the net) and (2) proportion of time (immobile) on the netting or in different zones of the flight arena. Parameters were analyzed in relation to net type, mosquito strain, and mosquito health status. The health status of mosquitoes tested in the wind tunnel assay was compared with the outcomes from the WHO cone and tube assays and registered as unaffected, knocked down, or dead.

Table 1.

Zone definitions used for spatial analyses at a range of 0–60 cm from the netting samples

| Zone | Zone description |

|---|---|

| 60–150 cm | Mosquito was more than 60 cm from the net |

| 30–60 cm | Mosquito was in a zone from 30 to 60 cm from the net |

| 0–30 cm | Mosquito was within 30 cm of the net |

| Net | Mosquito touched net at upwind side of the wind tunnel |

| On source | Mosquito reached (5 cm ø) host odor source at the net |

Zone widths were measured from the center of the arena at a height of 30 cm using images from camera 1. To optimize tracking, the angle of this camera was not 100% in (vertical) line with the arena, and therefore, the zones slightly overlap.

Binary logistics (generalized linear model [GLM]) were used to analyze differences in responses between net types and mosquito strain; time-related variables, such as response time and latency to touch the net, were analyzed using Cox's regression.

Results

WHO bioassays.

There was no knockdown or mortality in any of the controls. In the tube bioassay with susceptible mosquitoes, 100% knockdown and 100% mortality with deltamethrin netting and deltamethrin + PBO netting were observed. In the cone bioassay, 82% knockdown and 80% mortality were observed with deltamethrin netting, and 100% knockdown and 100% mortality with deltamethrin + PBO netting were observed (Figure 2). With the resistant mosquitoes in the tube assay, 70% knockdown and 53% mortality were observed for deltamethrin nets, and 80% knockdown and 71% mortality were observed for deltamethrin + PBO netting. In the cone bioassay, 44% knockdown and 40% mortality were recorded with deltamethrin netting, whereas 87% knockdown and 81% mortality were recorded with deltamethrin + PBO netting.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Percentage of mosquitoes that was recorded knocked down after 1 hour after testing in the wind tunnel or after 3 minutes of exposure in a cylinder tube or WHO cone. C and D show the death rate in percentage after 24 hours. Numbers above bars represent numbers of individuals recaptured in the wind tunnel and total numbers tested (in groups of five) for the other bioassays.

Behavioral assays.

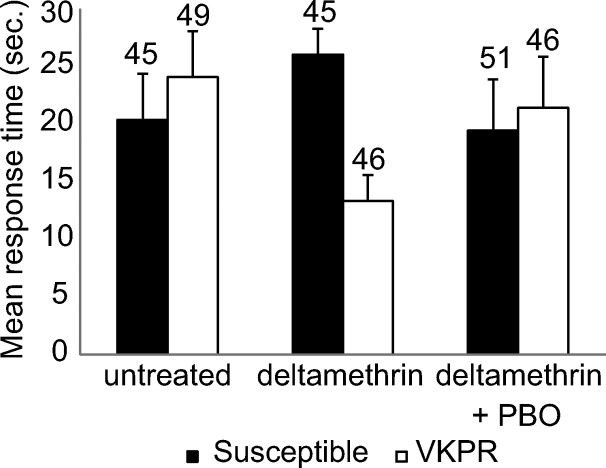

Mosquitoes took off for upwind flight in 92.5% (86.5–98.1%) of the cases, and there was no effect of mosquito strain and net type on the number of mosquitoes responding (leaving the release cage; GLM: P = 0.407 and P = 0.315, respectively) (Table 2). The mean response time varied between 13.3 and 26.0 seconds (Figure 3 ). There were no significant differences in response time between the netting samples and mosquito strains (Cox's regression: Wald = 1.40, degrees of freedom [df] = 2, P = 0.497 and Wald = 0.18, df = 1, P = 0.672, respectively).

Table 2.

Overview of mosquito responses in the wind tunnel and their health status after recapture

| Netting/strain | Released, N | Responding (ns), N | Touched net > 0 times, N (%) | Latency to touch net (seconds), mean (SEM) | On source Ø 5 cm on net (ns), N (%) | Recaptured, N | Knockdown, N (%) | 24-Hour mortality, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | ||||||||

| Susceptible | 52 | 45 | 23 (51.1) | 79.0 (14.4) | 7 (15.6) | 35 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| VKPR | 50 | 49 | 25 (51.0) | 138.3 (16.2)* | 13 (26.5) | 40 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Deltamethrin | ||||||||

| Susceptible | 51 | 45 | 29 (64.4)* | 93.8 (17.3) | 11 (24.4) | 36 | 6 (16.7)a | 6 (16.7)a |

| VKPR | 50 | 46 | 19 (41.3) | 140.7 (14.8)* | 7 (15.2) | 41 | 4 (9.8)a | 4 (9.8)a |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | ||||||||

| Susceptible | 52 | 51 | 35 (68.6) | 89.8 (14.6) | 16 (31.4) | 34 | 15 (44.1)b | 15 (44.1)b |

| VKPR | 50 | 46 | 24 (52.2) | 116.7 (14.9)* | 15 (32.6) | 37 | 16 (43.2)b | 15 (40.5)b |

Different letters within columns 8 and 9 indicate significant differences between the bed net types (GLM: P < 0.001). ns = no significant difference found between treatment and mosquito strain (GLM: P > 0.05).

Indicates a significant difference in number of susceptible mosquitoes that touched the deltamethrin-treated net compared with the resistant VKPR strain (GLM: Wald = 4.924, P = 0.026) and the latency to touch the net (Cox's regression: Wald = 5.95, df = 1, P = 0.015).

Figure 3.

Mean (±SEM) response time in seconds for each treatment in which mosquitoes took off for upwind flight within 3 minutes after being released at the downwind side of the wind tunnel.

For mosquitoes that took off for upwind flight, the amount of time spent in the different upwind zones of the wind tunnel (on netting; within 0–30 cm of the section, within 30–60 cm of the section, or farther away than 60 cm) was not different between the three netting types for each mosquito strain (Table 3) (Kruskal–Wallis, P > 0.05). The spatial distribution of mosquitoes across the wind tunnel was also examined separately for those mosquitoes that were not affected by the insecticides and those mosquitoes that were knocked down (Table 3). The mosquitoes affected by the treatment spent much longer sitting on the net compared with those mosquitoes that were unaffected (Figure 4 ) and less time in the sections farther than 30 cm from it (data per section in Table 3). VKPR mosquitoes that were unaffected by the deltamethrin + PBO netting spent significantly less time close to the net and relatively more time at the downwind side of the wind tunnel (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean (±SEM) duration of time (seconds) spent in different zones for each mosquito strain exposed to different netting samples

| Strain/netting | N | Mean time spent per zone (seconds) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 150–60 cm | 60–30 cm | 30–0 cm | Net | ||||||

| Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM | ||

| All mosquitoes | |||||||||

| Susceptible | |||||||||

| Untreated | 45 | 196.9 | 14.4 | 43.7 | 7.9 | 71.1 | 12.9 | 20.1 | 6.9 |

| Deltamethrin | 44 | 203.0 | 12.2 | 44.0 | 6.3 | 60.0 | 10.9 | 15.5 | 4.7 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 51 | 181.3 | 12.9 | 52.8 | 7.2 | 76.8 | 10.9 | 28.3 | 5.8 |

| VKPR | |||||||||

| Untreated | 49 | 203.0 | 11.9 | 53.8 | 7.9 | 51.2 | 8.5 | 14.1 | 3.6 |

| Deltamethrin | 45 | 209.4 | 12.9 | 45.5 | 7.6 | 52.3 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 4.5 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 45 | 213.1 | 13.0 | 38.9 | 5.8 | 54.3 | 10.6 | 26.9 | 7.6 |

| Recaptured → not knocked down | |||||||||

| Susceptible | |||||||||

| Untreated | 35 | 190.3 | 16.2 | 38.8 | 6.4 | 77.2 | 14.8 | 25.4 | 8.7 |

| Deltamethrin | 29 | 211.6 | 14.1 | 48.3 | 8.7 | 47.3 | 11.5 | 5.6 | 2.3 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 19 | 215.4 | 20.4 | 39.5 | 13.8 | 60.3 | 18.3 | 7.8 | 5.4 |

| VKPR | |||||||||

| Untreated | 40 | 210.2* | 12.2 | 48.0 | 7.1 | 50.8a | 7.9 | 15.1a | 4.0 |

| Deltamethrin | 36 | 213.1 | 13.9 | 46.8 | 9.2 | 47.3a | 10.2 | 4.9b | 1.8 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 21 | 258.7 | 12.4 | 32.8 | 9.5 | 12.5b | 4.6 | 1.2b | 0.7 |

| Recaptured → knocked down | |||||||||

| Susceptible | |||||||||

| Untreated | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Deltamethrin | 6 | 107.9 | 24.7 | 36.4 | 7.4 | 164.0 | 28.9 | 70.1 | 21.7 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 15 | 109.3 | 12.3 | 83.9 | 10.4 | 117.7 | 12.2 | 69.4 | 11.8 |

| VKPR | |||||||||

| Untreated | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Deltamethrin | 4 | 107.7 | 37.4 | 62.9 | 13.5 | 141.1 | 44.3 | 80.5 | 34.3 |

| Deltamethrin + PBO | 15 | 119.2 | 13.1 | 60.8 | 7.5 | 131.8 | 16.4 | 75.6 | 16.9 |

All mosquitoes includes data of all flying mosquitoes tracked in the wind tunnel. Recaptured → not knocked down includes recaptured individuals that were not knocked down 1 hour after testing. Recaptured → knocked down represents the data for recaptured mosquitoes that were knocked down after 1 hour. For each strain, a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to examine the differences between nets. Where P < 0.05, post-hoc analysis (multiple comparison, Scheffe) revealed the differences per bed net type. Different letters within a column show these differences if present. Because of low N values for untreated net and deltamethrin only, no statistics were performed here.

Kruskal–Wallis, P = 0.051.

Figure 4.

One-hour health status of both mosquito strains in relation to the duration spent on the net (x axis) and immobile on the net (y axis) in seconds.

Figure 5 shows examples of tracking results for each of the three netting types (control, deltamethrin, and deltamethrin + PBO). Fragments of animated flight tracks are shown in Supplemental Videos 1–3. These tracks were selected on the condition that the mosquito reached the upwind end of the arena, where the odor and heat source was placed behind the netting sample. The percentage of mosquitoes that made contact with the upwind net varied from 41.3% to 68.6%. The percentage of mosquitoes that reached the net at the site where host cues were released (5 cm diameter) ranged from 15.2% to 32.6% (Table 2). There was no interaction between netting type and mosquito strain in terms of reaching the odor source (GLM: P = 0.241) and no difference in response (exiting release container within 3 minutes) between the treatments and the mosquito strains (GLM: P = 0.108 and P = 0.863, respectively). Fifty-one percent of mosquitoes of either strain made contact with the upwind untreated net within 5 minutes (Table 2). There was no effect of treatment on the percentage of mosquitoes touching the net, and more susceptible than resistant mosquitoes touched the deltamethrin netting (GLM: Wald = 4.924, P = 0.026). Susceptible mosquitoes arrived sooner at the upwind end of the wind tunnel than the resistant strain (Table 2) (Cox's regression: Wald = 5.95, df = 1, P = 0.015). However, there was no significant difference between the netting types in latency to touch the net (Cox's regression: Wald = 0.71, df = 2, P = 0.701).

Figure 5.

Example of tracking results for individual mosquitoes of the susceptible strain approaching three different netting samples. The odor source is located on the upwind side, just behind the netting. The mosquito that contacted the untreated netting was unaffected. The other two mosquitoes showed a 1-hour knockdown response and died within 24 hours after recapture.

Of responding mosquitoes, 66.7–89.1% were recaptured and examined for 60-minute knockdown and 24-hour survival. None of the mosquitoes exposed to an untreated net in the wind tunnel were knocked down or died within 24 hours after exposure. Of the susceptible mosquitoes exposed to deltamethrin netting, 16.7% were knocked down and died within 24 hours, whereas 44.1% of those mosquitoes exposed to deltamethrin + PBO netting were knocked down and died. Of the resistant mosquitoes exposed to deltamethrin netting, 9.8% of mosquitoes were knocked down and died, whereas 43.2% of mosquitoes were knocked down and 40.5% of mosquitoes died after exposure to the deltamethrin + PBO netting (Figure 2 and Table 2). There was a clear effect of the time actually spent on the net on knockdown and mortality (Figure 4). As previously mentioned, all mosquitoes survived contact with the control netting; however, the variation in contact time with the control net did not differ from the nets that were treated with insecticides (Table 3). Because of the high correlation between knockdown and the eventual survival, the figures for contact time and 24-hour survival look similar (Supplemental Figure 4). With deltamethrin only, the minimum contact time needed to cause knockdown was 0.4 seconds for a susceptible mosquito and 49.2 seconds for a VKPR mosquito; these mosquitoes died within 24 hours after exposure. For the deltamethrin + PBO netting, the minimum contact time causing knockdown and mortality was 0.12 seconds for a susceptible mosquito and 0.04 seconds for a VKPR mosquito. There was a positive correlation between the time resting on the net and knockdown rate (Figure 4). The contact time causing knockdown was generally shorter for deltamethrin + PBO than deltamethrin only. The maximum time that a susceptible mosquito was found unaffected after 1 hour (and 24 hours) was 40.3 seconds of contact with deltamethrin only and 64.7 seconds with deltamethrin + PBO. For the VKPR strain, these times were 16.2 and 0.4 seconds, respectively.

Discussion

The results revealed a great discrepancy between the WHO bioassays and wind tunnel bioassays, especially in terms of the eventual killing effect of ITNs. The insecticide-treated nettings in the WHO tube and cone bioassays all caused high knockdown and mortality in susceptible mosquitoes, showing the high degree of toxicity of these compounds for An. gambiae. Numerous studies have reported a repellent effect as well as a toxic effect of these compounds, and indeed, these effects are considered additional attributes for the protective effect of pyrethroids.14,20 However, when these mosquitoes were exposed to both insecticidal treatments in the present study, in free flight, no repellent effect was observed. This result is evident by comparing the response and flight distribution patterns as well as the average time spent on the nettings. Only mosquitoes of the VKPR strain that survived the exposure to deltamethrin + PBO-treated nets expressed a mild repellent behavior by spending more time at the downwind end of the wind tunnel. It seems, therefore, that (non-resistant) mosquitoes did not perceive deltamethrin and/or PBO within the range of 1.5 m, the length of the wind tunnel.

Most studies on the effect of synthetic pyrethroids on mosquitoes have been conducted in experimental huts, where the effect of the insecticides on the mosquitoes is indirectly measured by recording the proportion of mosquitoes that enter and/or exit the hut or the proportion of mosquitoes that are found dead.12,15,31–36 Mosquitoes that hover on and around a net acquire sufficient quantities of insecticide to be killed; however, experimental hut studies were not designed to observe flight and/or landing behaviors of mosquitoes on nets, and the behavioral effects of the nets on the mosquitoes are recorded by counting the fractions of mosquitoes that are left in the hut at the end of the exposure time, which are termed excitorepellent effects. A possible explanation for the widely reported excitorepellent effect with deltamethrin-treated nets is that mosquitoes that enter a bedroom, attracted to human odors,37 are prevented from bloodfeeding, because the host is protected by a bed net; hence, they remain hungry, which drives them out of the house. An increase in exiting behavior in the presence of ITNs has been reported, where a proportion of the mosquito population succeeded to bloodfeed through manmade holes in the bed net.38,39 However, parameters used in experimental hut studies that are expressed as excitorepellency as described in the work by Koudou and others,14 a study in which treated nets were intact, could be linked to the behavioral effects resulting from hunger.

The work by Lindsay and others,13 which did not find a repellent effect of the synthetic pyrethroid permethrin, suggests that the reported deterrent effect of synthetic pyrethroids is produced by the components of the emulsifiable concentrate used for impregnating the nets and not the insecticide itself. Similarly, Magesa and others40 did not report an excitorepellent effect of pyrethroids. Because most compounds used for long-lasting manufacture of impregnated nets are inert, it is unlikely that such components cause excitorepellency. Kongmee and others7 recently reported contact irritancy caused by deltamethrin in An. minimus Theobald and An. harrisoni Harbach and Manguin, but the irritant effect was less clear in the presence of host odors. Similar to our study, there was no spatial effect of deltamethrin on the behavior of the mosquitoes. Additional analysis is required to determine whether host emanations can suppress irritant effects caused by the insecticide. In addition, it should be stressed that these findings were from experiments with unwashed new nets, and washed nets may give different results.

Our data are in line with the data reported in the work by Cooperband and Allan,18 which compared the excitorepellent effect of the synthetic pyrethroids bifenthrin, deltamethrin, and λ-cyhalothrin in a laboratory behavioral setting using the mosquito species Aedes aegypti (L.), An. quadrimaculatus Say, and Culex quinquefasciatus Say. The effect of the insecticides was observed from landing and resting behavior on contact with insecticide-treated filter paper. No difference was observed between untreated and treated paper, suggesting that these three pyrethroids did not cause an excitorepellent effect. Cx. quinquefasciatus, however, tended to avoid all three treated papers. Based on the heightened activity of some of the mosquitoes, it was suggested that the pyrethroids might affect locomotion behavior, which was previously suggested by Schreck and Kline.41 We have no information that this suggestion might be the case for An. gambiae.

The data from the WHO tube and cone bioassays indicated that the Wageningen An. gambiae strain (var. Suakoko) was susceptible to deltamethrin and that the VKPR strain was pyrethroid-resistant; mortalities with both formulations were < 80%. In the wind tunnel, the only behavioral difference observed between mosquito strains was in latency time reaching the net. Additional studies are suggested to focus on the possible differences in physiological state between affected and surviving individuals. The unaffected group may have also spent less time in odor plumes containing host odors and deltamethrin than the mosquitoes that showed a knockdown response, which would be in line with the previously discussed results by Kongmee and others.7

The effect on knockdown and survival caused by deltamethrin netting was significantly less than that of deltamethrin + PBO netting, which could be a result of the higher dose of deltamethrin in the netting with PBO; however, it should be noted that, as the deltamethrin is incorporated into the polyethylene, less than 10% of the total dose (4 g/kg) would be expected on the surface of the net and hence, available to the mosquito. In a coated net (such as the deltamethrin netting), much of the insecticide is on or near the surface. The presence of PBO may also affect the degree of knockdown and survival. Penetration, metabolic degradation, and interaction of insecticides with the site of action are known to influence knockdown.42 It has been suggested that synergists like PBO (which prevent detoxification of pyrethroids) have little effect on the knockdown phase of pyrethroid detoxification, while suppressing the recovery phase, which was shown in studies with Musca domestica and Triatoma infestans.43,44 The increased efficacy of a deltamethrin + PBO-treated netting compared with a deltamethrin only-treated netting was shown by N'Guessan and others33 using the WHO tunnel test assay with the VKPR strain. PBO is known to work by inhibiting metabolic enzymes (namely P450s and esterases) and enhance cuticular penetration of the insecticide into the insect.45–48 This effect on penetration occurs, because PBO also acts as a solvent to dissolve the insecticide and a surfactant on the waxy cuticle to increase the speed that the insecticide arrives at the target site, increasing efficacy of the insecticide, even with the presence of kdr.49 It is not known whether the effect observed in this study is caused by faster penetration of the insecticide through the cuticle because of the presence of PBO or the unknown presence of metabolic resistance in the VKPR strain, the different surface concentration, or the availability of deltamethrin in the deltamethrin + PBO netting.

The WHO tube and cone tests force mosquitoes into contact with the netting, and therefore, they pick up sufficient quantities of insecticide to cause knockdown and/or mortality within the specified exposure period. It is, therefore, an approved method to assess the bioefficacy of insecticide-impregnated materials. In the wind tunnel, by contrast, mosquitoes make a free flight and contact the netting without force when stimulated by the odor source present immediately behind the netting.10,26 A large percentage of mosquitoes (86.5–98.1%) took off for upwind flight within 3 minutes after exposure to the nettings. If a spatial or contact repellent effect would have been present, it would have been expressed clearly by reduced contact of mosquitoes with the treated nets compared with the untreated net. Such effects were not seen, apart from the resistant mosquitoes that remained relatively unaffected by the treated nets. It would be interesting to investigate if this behavior was related to the resistance mechanisms present in this mosquito strain. We conclude, therefore, that the treated nettings did not cause an excitorepellent effect in contrast to other studies using different methodologies.8,14,24

A lower efficacy of treated nettings was observed in the wind tunnel assay than the forced contact assays, because the mosquitoes made less contact with the netting than in the WHO assays because of the free flight, which more closely resembles the natural situation than the WHO assays, where mosquitoes are in forced contact with the insecticides. Exposure to deltamethrin + PBO netting caused a significantly higher knockdown and mortality effect in the wind tunnel compared with deltamethrin alone, although we do not know whether this result was because of the different concentration of deltamethrin or the additional effect of PBO. It should be noted that, under real-life conditions, a mosquito would have much longer than the 5-minute exposure time in this assay to make contact with the net; however, it is not known for how long a mosquito searches for a bloodmeal before abandoning this behavior. To link the behavioral data with the WHO tests and the consequential health status of the tested mosquitoes, we kept the exposure time in the wind tunnel close to 3 minutes, adding 2 minutes for getting to the net and moving away from it.

The use of camera systems and automated tracking has made it possible to study differences in behavior of various mosquito strains and species in both the laboratory and (semi) field settings.50 The wind tunnel assay is more sensitive to reveal behavioral effects than the current WHO assays and could be considered as an additional method useful for investigating spatial repellent effects of current and new insecticidal compounds.51 In the wind tunnel setup, in the presence of human host cues, it was found that both susceptible and resistant An. gambiae s.s. mosquitoes never spent as much as 3 minutes (cumulatively) on the test netting material in the absence of a bloodmeal. Although the 3-minute cone test remains a suitable method for investigating lethal and knockdown effects of pyrethroids, it does not provide any information regarding other potential behavioral responses that may be induced by exposure. Newly developed (non-pyrethroid) compounds may require longer contact times before a lethal dose will be picked up. Observational studies, such as the study presented here, can be used, for example, to validate appropriate exposure times for cone tests with new insecticides by investigating behavioral impacts of candidate compounds. The wind tunnel and video tracking assay could also be used to investigate how mosquitoes approach holes of different sizes in netting fabric as well as the optimum hole to insecticide content ratio or the optimum mesh size required for a netting fabric to physically prevent mosquito passage.

Conclusion

Free-flight exposure of mosquitoes to deltamethrin-impregnated nets did not reveal any (excito-) repellent effects in susceptible and resistant mosquitoes caused by deltamethrin when using a video-recorded assay. Close-range behavioral assays can reveal important information concerning the way mosquitoes approach and contact insecticide-treated netting, which is particularly important when considering the design of non-pyrethroid insecticide-treated fabrics and their evaluation in the field.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Frans van Aggelen, André Gidding, and Léon Westerd for rearing of the mosquitoes and Julie-Anne Tangena for assistance with the World Health Organization assays. We are grateful to all blood donors for their donation.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study received financial support from Vestergaard Frandsen SA and Wageningen University and Research Centre.

Authors' addresses: Jeroen Spitzen, Camille Ponzio, Constantianus J. M. Koenraadt, and Willem Takken, Laboratory of Entomology, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, E-mails: jeroen.spitzen@wur.nl, camillie.ponzio@wur.nl, sander.koenraadt@wur.nl, and willem.takken@wur.nl. Helen V. Pates Jamet, Vestergaard Frandsen SA, Lausanne, Switzerland, E-mail: hpj@vestergaard.com.

References

- 1.Steketee RW, Campbell CC. Impact of national malaria control scale-up programmes in Africa: magnitude and attribution of effects. Malar J. 2010;9:299. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SS, Fullman N, Stokes A, Ravishankar N, Masiye F, Murray CJL, Gakidou E. Net benefits: a multicountry analysis of observational data examining associations between insecticide-treated mosquito nets and health outcomes. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000363. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000363.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated nets for malaria control: real gains. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips-Howard PA, ter Kuile FO, Nahlen BL, Alaii JA, Gimnig JE, Kolczak MS, Terlouw DJ, Kariuki SK, Shi YP, Kachur SP, Hightower AW, Vulule JM, Hawley WA. The efficacy of permethrin-treated bed nets on child mortality and morbidity in western Kenya. II. Study design and methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binka FN, Kubale A, Adjuik M, Williams LA, Lengeler C, Maude GH, Armah GE, Kajihara B, Adiamah JH, Smith PG. Impact of permethrin impregnated bednets on child mortality in Kassena-Nankana district, Ghana: a randomized controlled trial. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kongmee M, Boonyuan W, Achee NL, Prabaripai A, Lerdthusnee K, Chareonviriyaphap T. Irritant and repellent responses of Anopheles harrisoni and Anopheles minimus upon exposure to bifenthrin or deltamethrin using an excito-repellency system and a live host. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2012;28:20–29. doi: 10.2987/11-6197.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh K, Rahman SJ, Joshi GC. Village scale trial of deltamethrin against mosquitoes. J Commun Dis. 1989;21:339–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabate A, Baldet T, Chandre F, Akoobeto M, Guiguemde TR, Darriet F, Brengues C, Guillet P, Hemingway J, Small GJ, Hougard JM. The role of agricultural use of insecticides in resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles gambiae s.l. in Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:617–622. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis CF. Control of Disease Vectors in the Community. London, UK: Wolfe Publishing Ltd.; 1991. p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosha FW, Lyimo IN, Oxborough RM, Matowo J, Malima R, Feston E, Mndeme R, Tenu F, Kulkarni M, Maxwell CA, Magesa SM, Rowland MW. Comparative efficacies of permethrin-, deltamethrin- and alpha-cypermethrin-treated nets, against Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus in northern Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:367–376. doi: 10.1179/136485908X278829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darriet F, Robert V, Tho Vien N, Carnevale P. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Permethrin-Impregnated Intact and Perforated Mosquito Nets against Vectors of Malaria. WHO Bulletin WHO/VBC 84. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsay SW, Adiamah JH, Miller JE, Armstrong JR. Pyrethroid-treated bednet effects on mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae complex in The Gambia. Med Vet Entomol. 1991;5:477–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1991.tb00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koudou BG, Koffi AA, Malone D, Hemingway J. Efficacy of PermaNet® 2.0 and PermaNet® 3.0 against insecticide-resistant Anopheles gambiae in experimental huts in Côte d'Ivoire. Malar J 10. 2011:172. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller JE, Lindsay SW, Armstrong JR. Experimental hut trials of bednets impregnated with synthetic pyrethroid or organophosphate insecticide for mosquito control in The Gambia. Med Vet Entomol. 1991;5:465–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1991.tb00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathenge EM, Gimnig JE, Kolczak M, Ombok M, Irungu LW, Hawley WA. Effect of permethrin-impregnated nets on exiting behavior, blood feeding success, and time of feeding of malaria mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:531–536. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Killeen GF, Smith TA. Exploring the contributions of bed nets, cattle, insecticides, and excitorepellency to malaria control: a deterministic model of mosquito host-seeking behaviour and mortality. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:867–880. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooperband MF, Allan SA. Effects of different pyrethroids on landing behavior of female Aedes aegypti, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2009;46:292–306. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts DR, Alecrim WD, Hshieh P, Grieco JP, Bangs M, Andre RG, Chareonviriphap T. A probability model of vector behavior: effects of DDT repellency, irritancy, and toxicity in malaria control. J Vector Ecol. 2000;25:48–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achee NL, Sardelis MR, Dusfour I, Chauhan KR, Grieco JP. Characterization of spatial repellent, contact irritant, and toxicant chemical actions of standard vector control compounds. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2009;25:156–167. doi: 10.2987/08-5831.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White GB. Terminology of insect repellents. In: Debboun MF, Strickman D, editors. Insect Repellents: Principles, Methods and Uses. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh T, Shinjo G, Kurihara T. Studies on wide mesh netting impregnated with insecticides against Culex mosquitos. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1986;2:503–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogh C, Pedersen EM, Mukoko DA, Ouma JH. Permethrin-impregnated bednet effects on resting and feeding behaviour of lymphatic filariasis vector mosquitoes in Kenya. Med Vet Entomol. 1998;12:52–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1998.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grieco JP, Achee NL, Andre RG, Roberts DR. A comparison study of house entering and exiting behavior of Anopheles vestitipennis (Diptera: Culicidae) using experimental huts sprayed with DDT or Deltamethrin in the Southern District of Toledo, Belize, C. A. J Vector Ecol. 2000;25:62–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okumu FO, Moore J, Mbeyela E, Sherlock M, Sangusangu R, Ligamba G, Russell T, Moore SJ. A modified experimental hut design for studying responses of disease-transmitting mosquitoes to indoor interventions: the Ifakara experimental huts. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO . Guidelines for Laboratory and Field Testing of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Mosquito Nets. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mboera LEG, Takken W. Odour-mediated host preference of Culex quinquefasciatus in Tanzania. Entomol Exp Appl. 1999;92:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smallegange RC, Knols BGJ, Takken W. Effectiveness of synthetic versus natural human volatiles as attractants for Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) sensu stricto. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:338–344. doi: 10.1603/me09015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzen JS, Smallegange CR, Takken W. Effect of human odours and positioning of CO2 release point on trap catches of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae s.s. in an olfactometer. Physiol Entomol. 2008;33:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . Guidelines for Testing Mosquito Adulticides for Indoor Residual Spraying and Treatment of Mosquito Nets. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carnevale P, Bitsindou P, Diomande L, Robert V. Insecticide impregnation can restore the efficiency of torn bed nets and reduce man-vector contact in malaria endemic areas. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:362–364. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darriet F, Chandre F. Combining piperonyl butoxide and dinotefuran restores the efficacy of deltamethrin mosquito nets against resistant Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2011;48:952–955. doi: 10.1603/me11022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.N'Guessan R, Asidi A, Boko P, Odjo A, Akogbeto M, Pigeon O, Rowland M. An experimental hut evaluation of PermaNet® 3.0, a deltamethrin-piperonyl butoxide combination net, against pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes in southern Benin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hougard JM, Corbel V, N'Guessan R, Darriet F, Chandre F, Akogbeto M, Baldet T, Guillet P, Carnevale P, Traore-Lamizana M. Efficacy of mosquito nets treated with insecticide mixtures or mosaics against insecticide resistant Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Cote d'Ivoire. Bull Entomol Res. 2003;93:491–498. doi: 10.1079/ber2003261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lines JD, Myamba J, Curtis CF. Experimental hut trials of permethrin-impregnated mosquito nets and eave curtains against malaria vectors in Tanzania. Med Vet Entomol. 1987;1:37–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1987.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malima RC, Oxborough RM, Tungu PK, Maxwell C, Lyimo I, Mwingira V, Mosha FW, Matowo J, Magesa SM, Rowland MW. Behavioural and insecticidal effects of organophosphate-, carbamate- and pyrethroid-treated mosquito nets against African malaria vectors. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takken W, Knols BGJ. Odor-mediated behavior of afrotropical malaria mosquitoes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1999;44:131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corbel V, Chabi J, Dabire RK, Etang J, Nwane P, Pigeon O, Akogbeto M, Hougard JM. Field efficacy of a new mosaic long-lasting mosquito net (PermaNet (R) 3.0) against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors: a multi centre study in Western and Central Africa. Malar J. 2010;9:113. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fane M, Cisse O, Traore CSF, Sabatier P. Anopheles gambiae resistance to pyrethroid-treated nets in cotton versus rice areas in Mali. Acta Trop. 2012;122:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magesa SM, Wilkes TJ, Mnzava AE, Njunwa KJ, Myamba J, Kivuyo MD, Hill N, Lines JD, Curtis CF. Trial of pyrethroid impregnated bednets in an area of Tanzania holoendemic for malaria. Part 2. Effects on the malaria vector population. Acta Trop. 1991;49:97–108. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(91)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schreck CE, Kline DL. Area protection by use of repellent-treated netting against culicoides biting midges. Mosq News. 1983;43:338–342. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruigt GSF. Pyrethroids. In: Kerkut GA, Gilbert LI, editors. Comprehensive Insect Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 12. Oxford, UK: Pergamon; 1985. pp. 183–262. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawicki R. Insecticidal activity of pyrethrum extract and its four insecticidal constituents against house flies. III. Knock-down and recovery of flies treated with pyrethrum extract with and without piperonyl butoxide. J Sci Food Agric. 1962;13:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alzogaray RA, Zerba EN. Incoordination, paralysis and recovery after pyrethroid treatment on nymphs III of Triatoma infestans (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:431–435. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernard CB, Philogene BJR. Insecticide synergists: role, importance, and perspectives. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1993;38:199–223. doi: 10.1080/15287399309531712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moores G, Bingham G, Gunning R. Use of 'temporal synergism' to overcome insecticide resistance. Outlook Pest Manag. 2005;16:7–9. doi: 10.1002/ps.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ahmad M, Denholm I, Bromilow RH. Delayed cuticular penetration and enhanced metabolism of deltamethrin in pyrethroid-resistant strains of Helicoverpa armigera from China and Pakistan. Pest Manag Sci. 2006;62:805–810. doi: 10.1002/ps.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young SJ, Gunning RV, Moores GD. Effect of pretreatment with piperonyl butoxide on pyrethroid efficacy against insecticide-resistant Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Bemisia tabaci (Sternorrhyncha: Aleyrodidae) Pest Manag Sci. 2006;62:114–119. doi: 10.1002/ps.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bingham G, Strode C, Tran L, Khoa PT, Jamet HP. Can piperonyl butoxide enhance the efficacy of pyrethroids against pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti? Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spitzen J, Spoor CW, Grieco F, ter Braak C, Beeuwkes J, van Brugge SP, Kranenbarg S, Noldus LP, van Leeuwen JL, Takken W. A 3D analysis of flight behavior of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto malaria mosquitoes in response to human odor and heat. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Achee NL, Bangs MJ, Farlow R, Killeen GF, Lindsay S, Logan JG, Moore SJ, Rowland M, Sweeney K, Torr SJ, Zwiebel L, Grieco JP. Spatial repellents: from discovery and development to evidence-based validation. Malar J. 2012;11:164. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.