Abstract

The mucoadhesive polymer, poly(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (pDMAEMA) was synthesised by living radical polymerisation and subsequently conjugated by esterification to the anti-inflammatory corticosteroid, dexamethasone, to separately yield two concentrations of conjugates with ratios of 10:1 and 20:1 active:polymer. The hypothesis was to test whether the active agent maintained in vitro bioactivity when exposed to the apical side of human intestinal epithelial monolayers, Caco-2 and mucous-covered HT29-MTX-E12 (E12). HPLC analysis showed that 80% of the dexamethasone in both conjugates was attached to pDMAEMA. Similar to pDMAEMA, fluorescently-labelled dexamethasone-pDMAEMA conjugates were bioadhesive to Caco-2 and mucoadhesive to E12. Apical addition of conjugates suppressed mRNA expression of the inflammatory markers, NURR1 and ICAM-1 in E12 following stimulation by PGE2 and TNF-α, respectively. Conjugates also suppressed TNF-α stimulated cytokine secretion to the basolateral side of Caco-2 monolayers. pDMAEMA was inactive in these assays. Measurement of dexamethasone permeability from conjugates across monolayers suggested that conjugation reduced permeability compared to free dexamethasone. LDH assay indicated that conjugates were not cytotoxic to monolayers at high concentrations. Anti-inflammatory agents can therefore be successfully conjugated to polymers and they retain adhesion and bioactivity to enable formulation for topical administration.

1. Introduction

The use of bioadhesive polymers is a popular approach used to develop oral drug delivery technology by either increasing bioadhesion and/or enhancing epithelial permeation [1–3]. Mucoadhesives including polycarbophil and chitosan have also been shown to open epithelial tight junctions and they appear to enhance intestinal permeability in part by chelating calcium [4, 5]. Previous research suggests however, that the mucoadhesive polymer, pDMAEMA (poly (dimethylamino) ethyl methacrylate) does not open tight junctions and that its mechanism of interaction with cell monolayers and isolated intestinal tissue relies on muco-integration allied to bioadhesion [6]. Increasing permeability might not always be a desirable trait for mucoadhesive polymers. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) for example, there is damaging cross-talk between the immune system, the epithelium and the lumen and this is characterised by a permeability defect which may enable pathogen uptake, (reviewed in [7]). In such conditions, selected polymers may reduce pathogen access to the epithelium [8, 9], and in addition, mucoadhesive ones may also be used to deliver co-administered restorative drugs to the damaged epithelial surface [10]. In previous work, we showed that pDMAEMA retained the first set of beneficial properties by impeding adherence and uptake of bacterial toxins by the human intestinal mucus-covered monolayers, HT29-MTX-E12 (E12) [11]. Futhermore, pDMAEMA is directly anti-bacterial as it inhibits Salmonella adherence to monolayers and is bacteriocidal against a range of Gram-positive and negative organisms [11]. pDMAEMA also has useful properties in that it is readily synthesised by living radical polymerisation, and it is soluble, adhesive and non-cytotoxic [6]. In relation to the second beneficial property of co-administering restorative drugs to damaged epithelium of the lower intestine, the presence of multiple amine groups makes pDMAEMA a good candidate for drug conjugation.

Corticosteroids bind to cytosolic cortisol receptors to instigate a cascade of anti-inflammatory effects following translocation to nuclear DNA to initiate gene transcription. The synthetic anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive glucocorticoid, dexamethasone (392 Da), is an important first-line drug in the treatment of moderate and severe active Crohn’s disease, but systemic side effects commonly associated with chronic administration is a perennial problem [12]. One method of overcoming this problem is by topical drug delivery to the epithelium, thereby localising the glucocorticoid to the inflamed lower bowel. In a rat colitis model for example, orally-administered glucoside-based prodrugs of dexamethasone significantly reduced the adrenal suppression that is normally seen as a systemic side-effect of oral dexamethasone [13]. Another advantage of conjugated drug targeting to the lower bowel for IBD is that doses may be lowered as the active agent can potentially be localised using encapsulated formats [14]. Although the bacterial enzyme-sensitive prodrugs of dexamethasone did not end up being developed for man, the principle of enzymatic breakdown of prodrugs in the colon is an important one, long established for the front-line colitis therapies, sulphasalazine and mesalazine [15]. Together with enteric coated chronotropic particle release systems for colonic delivery [16], prodrug approaches for colonic delivery remain a subject of intense research.

The aims of this study were to synthesise and assess novel adhesive conjugates of dexamethasone attached to pDMAEMA (DEX-pDMAEMA) in human intestinal monolayers. Mucoadhesion of DEX-pDMAEMA was assessed by measuring fluorescence of the stably-incorporated hostasol molecule [17] in the presence and absence of mucus gel overlying intestinal monolayers. The transport of dexamethasone from conjugates across E12 monolayers was measured and compared to that of unconjugated dexamethasone. The in vitro anti-inflammatory bioactivity of conjugated dexamethasone was measured in both Caco-2 and E12 intestinal epithelial monolayers through its ability to suppress a selection of transcriptional and translational biomarkers of inflammation. We show that DEX-pDMAEMA conjugates can be successfully synthesised and that they retain adhesive and anti-inflammatory properties in vitro, while at the same time they retard the transepithelial flux of the active agent.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Materials

All tissue culture reagents were from Gibco (Biosciences, Ireland). Tissue culture membranes, plates and Transwells® were from Corning Costar (Fannin Healthcare, Ireland). ELISA multi-spot cytokine kits were obtained from Meso Scale Discovery, San Diego, CA. The BioX Diagnostics ELISA for dexamethasone was from Serosep, Ireland. The lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) kit, n-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and all other reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich, UK.

2.2. Polymerisation of DMAEMA using a hostasol-derived initiator

Cu(I)Br (426 mg) and hostasol (thioxantheno[2, 1,9-dej]isochromene-1,3-dione) initiator (1.6 g) were weighed out into a Schlenk tube and sealed with a subaseal. Hostasol was made using a slight modification of a procedure described using 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide in place of methacryloyl chloride [18]. DMAEMA, 40 mL, was filtered through alumina and degassed and toluene (80 mL) was added. The mixture was frozen in liquid nitrogen and degassed via four freeze-pump-thaw cycles. The reaction mixture, under an atmosphere of nitrogen, was placed in an oil bath at 90 °C and stirred for 5 minutes. N-(n-propyl)-2-pyridylmethanimine (propyl ligand) (0.93 mL) was used as the polymerization initiator. The polymerisation mixture was heated to 90 °C under an atmosphere of nitrogen. Reaction aliquots (0.4 mL) were removed at times, 30, 60, 90, 300 and 360 minutes. Polymerisation was followed by 1H-NMR. After 360 minutes, the reaction mixture was removed from the oil bath, diluted with 50 mL toluene and filtered through a column of basic alumina to remove the copper catalyst. The column was washed with two column volumes of toluene and toluene/ethyl acetate (1:1, v/v), and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure. The polymer was dissolved in 120 mL chloroform and added drop-wise to a beaker of light petroleum with vigorous stirring to precipitate the polymer. The solvent was decanted off and the polymer reconstituted in chloroform and evaporated under reduced pressure to give fluorescent hostasol-pDMAEMA (30 g, Mw 1.5 kDa) as a brown crystalline solid (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of conjugated materials. (a) Hostasol-pDMAEMA. (b) MeI- quaternised hostasol-pDMAEMA. (c) HCL-quaternised hostasol-MeI-pDMAEMA. (d) Dexamethasone bromoacetate. (e) Dexamethasone bromoacetate conjugated to hostasol-pDMAEMA.

2.3. Quaternisation of hostasol-pDMAEMA with methyl iodide and HCl

Hostasol-pDMAEMA was reacted with methyl iodide to give quaternised polymers (Fig. 1b). Hostasol-pDMAEMA (100 mg) was dissolved in anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) (7 mL) at ambient temperature under an atmosphere of nitrogen. Methyl iodide (MeI, 0.2 mM; 0.4 mM; 0.6 mM) was added to give quaternisation levels of 33 %, 66 % and 100 % respectively and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 7 hours. Precipitation of the polymer occurred after ~20–30 minutes. The reaction mixture was diluted with hexane and the quaternised polymer was filtered. Hostasol-pDMAEMA was dissolved in 100 mL of 1M HCL (aq.) with stirring. The orange solution was frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried to give quaternised hostasol-pDMAEMA-HCL (11.4 g) as an orange powder (Fig. 1c).

2.4. Affinity labelling of dexamethasone for conjugation

Dexamethasone was subjected to electrophilic affinity labelling with bromoacetate [19] in order to conjugate it to pDMAEMA amine groups through ester linkage. Anhydrous dichloromethane (20 mL) was added to a flask containing dexamethasone (100 mg, 0.255 mmol), dimethylaminopyridine (37 mg, 0.306 mmol) and bromoacetic anhydride (79 mg, 0.306 mmol) at ambient temperature under an atmosphere of nitrogen. The mixture was stirred at room temperature and the reaction was followed by TLC (petroleum ether-ethyl acetate, 1:1 (v/v), Rf 0.37). After 90 minutes, the solution was washed successively with saturated aqueous sodium hydrogen carbonate (20 mL), 0.1M HCl (aq.) (20 mL), brine (20mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure to give the title compound (Figure 1D) (118 mg, 90 %) as a white solid. High Resolution Microwave Survey (HRMS) calculated for C24H30BrFO6+: 513.41 Da, in practice found: 513.56 Da. Attachment of bromoacetate does not result in loss of dexamethasone efficacy [19, 20] and there was no difference between dexamethasone and dexamethasone bromoacetate in suppressing RNA expression of the anti-inflammatory biomarker, NURR1 (data not shown).

2.5. Conjugation of hostasol-pDMAEMA to dexamethasone bromoacetate

Hostasol-pDMAEMA (100 mg) and dexamethasone bromoacetate (31 mg and 62 mg respectively, to achieve 10 % ands 20 % quaternisation levels,) were dissolved in anhydrous THF (7 mL) at ambient temperature under an atmosphere of nitrogen. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 24 hours. The precipitates were filtered, washed with light petroleum ether and dried to yield conjugates 123 mg (10 % conjugate) and 148 mg (20 % conjugate) as pale orange coloured solids (Fig. 1e). The resulting complexes had dexamethasone bromoacetate molecules conjugated at a ratio of either 9 molecules of dexamethasone bromoacetate (representing conjugation to 10% of available amine groups, designation: P10) or 18 molecules of dexamethasone bromoacetate (representing conjugation to 20% of available amine groups, designation: P20) for each molecule of pDMAEMA. pDMAEMA was therefore conjugated via ester linkage to the affinity-labelled dexamethasone. As the molecular weights of dexamethasone bromoacetate (512 Da), pDMAEMA (1.5 kDa) and conjugates (P10:19.6 kDa; P20: 24 kDa) were known, the relative dexamethasone concentration for each could be mathematically calculated. This allowed direct comparison of concentrations of dexamethasone from each DEX-pDMAEMA conjugate used in assays. In order to confirm conjugation and purity of the polymer and dexamethasone, samples were analysed by SEC-HPLC using a BioSep-SEC-S-2000 column (300 × 7.8 mm) (Phenomenex, UK). Samples were eluted with 50 mM PO4 pH 6.8 at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, and monitored at a UV absorbance of 280 nm. The molecular weight of DEX-pDMAEMA was estimated using a calibration curve of the logarithmic molecular weight of polymer standards versus retention time.

2.6. Adhesion and cytotoxicity assays using cultured human intestinal monolayers

Caco-2 and E12 cells were cultured as monolayers on 24 well plates and on filters as previously described [21, 22]. In some cases, the mucus gel layer was removed from E12 monolayers through incubation with a mucolytic, n-acetyl cysteine (NAC, 10mM, 15 minutes [6]). For adhesion, drug flux and cytokine assays, cells were grown as monolayers on polycarbonate Transwell® permeable supports (Corning Costar ®, 0.4 µm pore size, area 5.5 or 1 cm2). For the adhesion assay, E12 monolayers were rinsed with HEPES-buffered-DMEM and equilibrated at 37°C for 60 minutes before being rinsed gently with medium. 0.5 mL of hostasol-conjugate was added to the apical side at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. Monolayers were incubated at 37°C in a Titramax® 1000 shaking incubator for 60 minutes at 100 rpm. Fluorescent polymer concentrations were measured in 50µL samples taken from both sides of the monolayers at 0 and 60 minutes. Following aspiration of the polymer-loaded donor side, the monolayers were then washed three times in incubation buffer, homogenized, and lysed in 2% SDS and EDTA (50 mM) at pH 8.0. All samples were assayed on an LS 50B Luminescence Fluorimeter at optimum hostasol detection wavelengths of 495nm for excitation and 525nm for emission and data was expressed as µg polymer / cm2 [6]. Negligible amounts of signal were detected in the washes. Muco- and bioadhesion were defined as the proportion of material bound to monolayers in the presence and absence of mucus. Cytotoxicity of polymeric conjugates was assessed by release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from E12 monolayers following incubation for 60 minutes [23].

2.7. Transepithelial flux of dexamethasone across E12 monolayers

21-day old E12 monolayers were incubated for 120 minutes in 10mM HEPES-buffered DMEM medium with apical concentrations of DEX-pDMAEMA (P10, P20), equivalent to 10nM dexamethasone. 100µL samples were taken from the basolateral side at 20-minute intervals and the medium replaced. Fluxes of free dexamethasone and dexamethasone bromoacetate were also assessed. Basolateral samples were assayed for dexamethasone by a competitive ELISA kit (BioX Diagnostics, Cat. # BIO-K-099). The apparent permeability (Papp) for dexamethasone across monolayers was calculated from cumulative concentration vs. time profiles using the following equation [24]:

Papp (cm/sec) = (dQ/dt) / (1/ (A*Co))

dQ/dt (µg/s) is the cumulative concentration increase in the basolateral receiver side with respect to time, A (cm2) is the surface area of the monolayer and Co (µg) is the initial concentration in the donor apical compartment.

2.8. In vitro bioactivity of DEX-pDMAEMA conjugates in intestinal epithelial monolayers

Dexamethasone-induced suppression of NURR1 RNA was assessed in PGE2-stimulated E12 monolayers. 21-day old filter-grown monolayers were incubated with 1µM PGE2 in culture medium for 120 minutes. The medium was aspirated and replaced with 10mM HEPES-buffered RPMI medium for 120 minutes with P10 and P20 in concentrations ranging from 0.1 nM to 10 nM dexamethasone bromoacetate. Unconjugated dexamethasone bromoacetate and dexamethasone-free controls were also included. Total RNA was isolated and NURR1 was amplified by RT-PCR [25]. The primer sequences for NURR1 were: Forward; CGACATTTCTGCCTTCTCC; Reverse GGTAAAGTGTCCAGGAAAAG; the product size was 277 base pairs. RT-PCR was performed using the Invitrogen Superscript™ One-Step RT-PCR System (Cat.#12574-026) using β-actin as housekeeping gene. Using electrophoresis, PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide and visualised under UV light. Results were determined by image analysis of band intensity from PCR product gels using ImageJ software [26].

RT-PCR was also carried out on mRNA from Caco-2 monolayers to measure levels of ICAM-1 RNA induced by TNF-α [27] and to see if they could be suppressed by the conjugate pre-incubation. Briefly, Caco-2 cells were grown on plastic 6-well plates and allowed to reach confluence. Cells were pre-treated with dexamethasone, P10, P20 or vehicle at selected concentrations for 60 minutes. Cells were then treated with either 1 or 10 ng/ml TNF-α and incubated for 12 hours. The mRNA was harvested and cDNA was generated using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit, Bio-Rad Corp, Hercules, CA, USA). RT-PCR was performed as described above. The primer sequences for ICAM-1 were: Forward, CACAGTCACCTATGGCAA; Reverse, TTCTTGATCTTCCGCTGGC.

Secreted cytokine and chemokine protein levels were examined in Caco-2 by multi-spot ELISA [28, 29]. Caco-2 monolayers were grown for 21 days on Transwells® (pore size 0.4µm, area, 5.5 cm2). Cells were pre-treated with 10 nM pDMAEMA, dexamethasone, P10, P20, or vehicle for 60 minutes. Cells were then treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours. Basolateral samples were sampled and assayed for IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8 using TH1/TH2 10-spot human cytokine ELISA plates (Meso Scale Discovery, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data is given as a mean ± standard error of the mean of a minimum of 3 independent replicates. Unless stated, 2-way unpaired Student’s t-tests were used to assess differences with the level of significance set at P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Conjugation of dexamethasone bromoacetate to pDMAEMA

In order to confirm conjugation, the conjugates were analysed by SEC-HPLC. Quantification was carried out by peak area analysis and approximately 80% of the original dexamethasone was accounted for in conjugate material (Fig. 2). DEX-pDMAEMA sample was of high purity (as indicated by the typical chromatogram of a P20 sample). The sample run time was 40 minutes in total, in which no other major peaks were detected. Importantly, no free dexamethasone was detected in the conjugate. When free dexamethasone was run on the HPLC, the retention time of the free dexamethasone peak could not be detected in the DEX-pDMAEMA chromatogram. The calculated molecular weight for DEX-pDMAEMA was 9.78 kDa.

Fig. 2.

HPLC analysis of DEX-pDMAEMA (P20). The calculated molecular weight for DEX-pDMAEMA was 9.78 kDa. The DEX-pDMAEMA samples were of high purity, as indicated by the major peak.

3.2. Adhesion and cytotoxicity of DEX-pDMAEMA in E12 monolayers

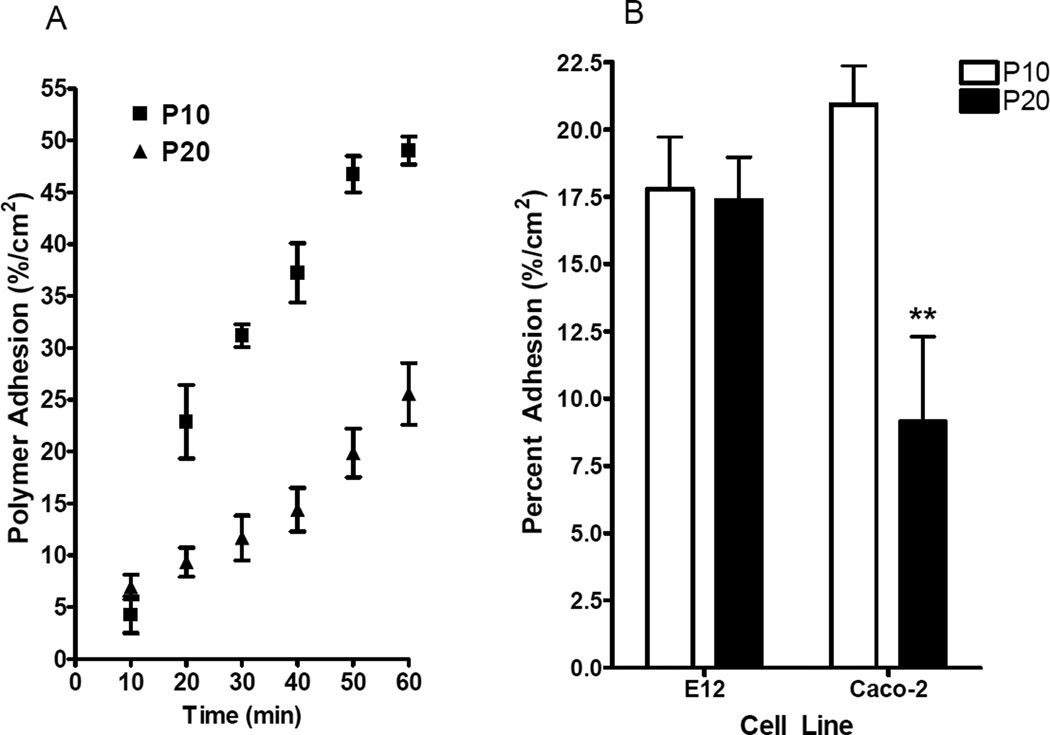

P10 and P20 were bioadhesive (Fig. 3a) with 50% of P10 associated with Caco-2 monolayers after 60 minutes and 25% of P20 associated with Caco-2 monolayers after 60 minutes. The rate of adherence for P20 was significantly higher than for P10 (P<0.001, two-way ANOVA). The initial concentration of polymer on the donor apical side was 0.1 mg/mL. Both P10 and P20 polymers adhered to Caco-2 in a time-dependent manner. P10 was found to be equally mucoadhesive and bioadhesive, and it bound to mucus-covered E12 monolayers and to Caco-2 monolayers at similar levels (Fig. 3b). P20 adherence to Caco-2 monolayers was significantly lower than to E12 (Fig. 3b) and this suggested that it was less bioadhesive than P10. Despite this difference, both conjugates showed high levels of mucoadhesion, of the same order as unconjugated pDMAEMA [6].

Fig. 3.

(a) Time-course adhesion of P10 and P20 to Caco-2 monolayers over 60 minutes. The adherence for P20 was significantly higher than for P10 (P<0.001, two-way ANOVA) (b) Adhesion of P10 and P20 to Caco-2 and E12 monolayers. In (a) and (b), donor-side concentrations were 0.1 mg / ml. N = 6 in each group. ** P<0.01 for P20 adherence to Caco-2 vs. P20 adherence to E12.

P10 and P20 induced low cytotoxicity to E12 monolayers at the three concentrations tested over 60 minutes as measured by LDH release, compared to maximal release induced by 0.1% Triton-X-100 detergent. While cytotoxicity of the conjugates was slightly higher on E12 monolayers that had the mucus gel removed by pre-incubation with the mucolytic, NAC, the same low trend was observed in mucus-covered and mucus-stripped E12 cells (Table 1). In mucus-covered E12, concentrations of up to 1mg / ml P10 and P20 killed less than 10% cells following exposure for 60 minutes. This data was of the same order as previously reported for pDMAEMA in the same cells [6]. In non-mucus covered HT29 monolayers, pDMAEMA killed a maximum of 5.4% cells following exposure to 1 mg / ml for 120 minutes [6].

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of dexamethasone conjugates in E12 monolayers by LDH assay

| E12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration | 0.01 mg/ml | 0.1 mg/ml | 1 mg/ml |

| P10 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 2.5 |

| P20 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 9.0 ± 0.3 |

| pDMAEMA | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.8 |

| NAC-treated E12 | |||

| P10 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 2.0 |

| P20 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 8.0 ± 3.0 | 15.0 ± 3.5 |

NAC-E12: E12 monolayers exposed n-acetyl cysteine (10mM, 15 minutes). P10: 10% DEX-pDMAEMA; P10: 20% DEX-pDMAEMA N= 12 in each group. Values are given as the percentage dead cells compared to the positive control, 0.1% Triton-X-100. pDMAEMA values are from ref [6].

3.3 Fluxes of dexamethasone across intestinal monolayers

Apical-to-basolateral side fluxes of dexamethasone were carried out on E12 and NAC-treated E12 to examine the role of the mucus gel layer on the apparent permeability of dexamethasone and the conjugates (Fig. 4). There was no difference between the ELISA-derived Papp of dexamethasone and dexamethasone bromoacetate (results not shown). Removal of the mucus gel layer with NAC was found to significantly increase dexamethasone flux across E12 monolayers compared to mucus-covered monolayers (P<0.001). These data suggests that mucus gel is a significant barrier to the unconjugated lipophilic dexamethasone molecule. Importantly, the Papp values of free dexamethasone was significantly higher than that of P10 and P20 across E12 (P=0.002; P=0.024, respectively). Similarly, in NAC-exposed E12 monolayers, the Papp of free dexamethasone was significantly higher than the Papp from P10 and P20. (P<0.0001 in each case). Therefore the data suggest that dexamethasone permeability across monolayers is reduced in the conjugate format compared to dexamethasone and, moreover, that dexamethasone permeability from conjugates is not affected by the presence or absence of mucous.

Fig. 4.

Papp of dexamethasone bromoacetate across E12 monolayers. Dexamethasone donor-side concentrations were 10 nM. NAC-E12: E12 monolayers exposed to NAC (10mM, 15 minutes). *P<0.05 vs. free dexamethasone in E12; **P<0.001 vs. free dexamethasone in NAC-E12. † P<0.001 vs. free dexamethasone in E12. N=6 in each group.

3.4. In vitro bioactivity of DEX-pDMAEMA

First, we examined the capacity of dexamethasone formulations to suppress expression of an inflammatory marker, NURR1 mRNA, in E12 monolayers. The pro-inflammatory hormone, PGE2, (1 µM) increased NURR1 mRNA expression two-fold. Basal levels of NURR1 mRNA were suppressed by 10 nM dexamethasone, but not by free pDMAEMA (Fig. 5a, b). Dexamethasone, P10 and P20 all significantly reduced PGE2-induced NURR1 expression in E12 monolayers (P=0.0003, P=0.0042 and P=0.0016 respectively), (Fig. 5a,c). The reductions in expression induced by the dexamethasone conjugates and free dexamethasone was similar at 10 nM concentrations. The negative control, pDMAEMA had no effect on PGE2-induced NURR1 expression in E12 (Fig. 5a, c).

Fig. 5.

RT-PCR of PGE2-induced NURR1 mRNA in E12 monolayers. (a) Lanes: 1.Basal; 2.PGE2 (1µM); 3. Dex (10 nM); 4. pDMAEMA (10µg/ml); 5. PGE2 / Dex (10 nM); 6. PGE2 / P10 (10 nM); 7. PGE2 / P20 (10 nM); 8. PGE2 / pDMAEMA (10µg/ml). Lanes 5-8 were pre-treated with PGE2 (1µM) for 120 minutes before challenge with test or control for 120 minutes. (b) Densitometer analysis comparing to basal expression of NURR1 with test groups (c) Densitometer analysis comparing to PGE2-induced NURR1 with test groups. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05; N=3 for each group.

Next, we examined RT-PCR analysis of ICAM-1 mRNA induction in Caco-2 monolayers. ICAM-1 expression was induced by 1 and 10 ng / ml TNF-α in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6a). Induction by both concentrations of TNF-α was significantly reduced by pre-treatment with free dexamethasone, P10 and P20 in concentration-dependent fashion ranging from a threshold of 1 pM up to 10 nM (Fig. 6a, b). Dexamethasone and P20 also statistically reduced basal levels of ICAM-1 mRNA, even in the absence of stimulation by TNF-α (Fig. 6a). The negative control, pDMAEMA, had no effect on ICAM-1 expression in Caco-2 (Fig. 6 a,b).

Fig. 6.

Induction of ICAM-1 mRNA expression in Caco-2 by TNF-α and suppression by dexamethasone conjugates, P10 and P20. (a) Concentration of dexamethasone was 10nM; **P<0.01 vs. pDMAEMA. (b) Concentration of TNF-α was 1 ng / ml; **P<0.01 vs. pDMAEMA. N=3 for each group.

Finally, we examined suppression of basolateral-side secretion of inflammatory cytokine protein markers by the dexamethasone formulations in Caco-2 monolayers challenged with TNF-α. Secretion of IL-6, (Fig. 7a), IL-8 (Fig. 7b) and IL-1β(Fig. 7c) were measured. All three cytokines were secreted in significant quantities in response to TNF-α exposure (10 ng/ml) and this secretion was statistically reduced by dexamethasone, P10 and P20 (each at 10 nM). pDMAEMA had no effect on cytokine secretion per se.

Fig. 7.

Suppression of TNF-α-induced secretion in Caco-2 by dexamethasone P10 and P20. (a) IL-1B; (b) IL-6; (c) IL-8. Dexamethasone concentrations were 10nM in each case. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01 vs. TNF-α /pDMAEMA group; ### P<0.001 vs. TNF-α/ Null group. N=3 for each group.

4. Discussion

There is considerable interest in developing topical drug delivery systems using polymeric materials [30, 31]. Examples of potential benefits include improved solubility and permeation enhancement conferred by the co-administered polymer for corneal delivery [32], mucoadhesive organogels for retention in the oral cavity [33], and polymeric drug conjugates for regional localised delivery to the large intestine [13]. A conjugated format for IBD is especially attractive since it allows an opportunity for targeted delivery, dependent on enzymatic cleavage at the site of action leading to delivery of anti-inflammatory agents with reduced systemic bioavailability. In this study, we conjugated a well-known mucoadhesive and bioadhesive hydrophilic polymer, pDMAEMA, to a potent anti-inflammatory steroid, dexamethasone. The rationale was that pDMAEMA has inherent adhesiveness; it can integrate into mucus and is non-cytotoxic. Importantly, unlike chitosan and polycarbophil, it can reduce flux of paracellular probes [6]. Allied to its recently discovered anti-microbial actions [11], pDMAEMA may have therefore have potential as a drug delivery polymer that can attach to inflamed epithelia and release cargoes conjugated to its amine groups without compromising the tissue further.

Oral corticosteroids can cause a wide range of systemic side-effects in IBD [34]. To illustrate the point, in contrast to well-absorbed dexamethasone, recent clinical trials with a glucocorticoid with lower oral bioavailability (budesonide) demonstrated remission in Crohn’s disease in the absence of adrenosuppression [35]. Previous work with dexamethasone-beta-D-glucuronide prodrugs, showed in addition that conjugated dexamethasone could be delivered at lower doses than free dexamethasone leading to similar outcomes in a rat colitis model [13]. Moreover the conjugate maintained serum corticosterone and plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone levels near control levels, whereas free dexamethasone reduced serum corticosterone levels to sub-normal levels. This suggests that conjugated systems may effectively deliver corticosteroids to the intestine while limiting steroid-related side-effects. Recent studies also suggest that dexamethasone can prevent TNF-α-induced permeability increases in Caco-2 by binding to the myosin light chain kinase promoter region that controls tight junction openings [36]. Since pDMAEMA also reduces paracellular fluxes [6], further reductions in intestinal permeability could be envisaged by the two agents used in combination for IBD.

Dexamethasone bromoacetate was conjugated to pDMAEMA via an ester linkage to pDMAEMA amine groups. Ester groups are readily hydrolysed by intestinal enzymes in the mucus gel layer and mucoadherent conjugates may therefore release the dexamethasone directly into the mucus gel [37]. Additionally, dexamethasone may by cleaved from the polymer by epithelial cell-derived esterases [38], while other intestinal enzymes such as trypsin, chymotrypsin or elastase may also work to degrade the polymer linker [39–41]. Other candidate enzymes for cleavage of the dexamethasone linker include cellular esterases [42]. These enzymes, or an as yet unidentified enzyme, may act to cleave the dexamethasone molecule from pDMAEMA. Degradation studies with esterases using HPLC will allow examination of the kinetics of the cleavage event. Although no direct assay of disassociation was shown in the current study, the in vitro bioactivity of dexamethasone in the conjugate and the detection of dexamethasone on the basolateral side of monolayers exposed apically to the conjugate strongly infers that dexamethasone must be cleaved from pDMAEMA since the polymer is far too large to both penetrate the plasma membrane and to cross the epithelial monolayer. As the dexamethasone receptor is cytosolic [43], any observed bioactivity of dexamethasone must therefore be due to unconjugated drug. That the effects might be produced by an artifact of unbound dexamethasone is highly unlikely as suggested by the very clear peak of the conjugate on the HPLC chromatogram as well as the established high efficiency of the living radical polymerisation process. Even in the unlikely event that there was a degree of contamination with free steroid, the concentrations would not be high enough to account for the biological effects seen with the conjugate.

pDMAEMA polymers did not lose mucoadhesiveness when conjugated to dexamethasone. Two dexamethasone-pDMAEMA conjugates were generated, one with 10% conjugated dexamethasone (P10) and the other with 20% conjugated dexamethasone (P20). Conjugates were found to be equally mucoadhesive and, while P10 was found to be equally mucoadhesive and bioadhesive, P20 was found to be significantly less bioadhesive than mucoadhesive. This may be due to the increased number of dexamethasone molecules on the polymer, which may prevent mucoadhesion occurring through a charge interaction between the amine groups of the pDMAEMA and the mucin glycoproteins. Another possibility is that the hydrophobicity of dexamethasone molecules causes a conformational change in the conjugate polymer structure, forming a micelle-like configuration due to interactions with the aqueous environment. In either case, conjugation to dexamethasone did not confer any cytotoxic properties on pDMAEMA above its normal low level on these cells [6].

The nuclear orphan receptor, NURR1, was shown to regulate pro-inflammatory mediators [44] and ICAM-1 is a previously described marker of inflammation in Caco-2 cells [45]. Although NURR1 has been previously identified in intestinal carcinoma cells in vivo [46], NURR1 expression has not been previously shown in intestinal cell lines. Dexamethasone bromoacetate, P10 and P20 suppressed PGE2 induced NURR1 expression in E12 monolayers to similar low levels. NURR1 is a transcription factor upstream of the main inflammatory mediators and it may be useful as a potential screening target for anti-inflammatory agents. The capacity of the dexamethasone conjugates to reduce TNF-α stimulation of ICAM-1 expression in Caco-2 monolayers was consistent with the NURR-1 studies. These effects on ICAM-1 expression were robust and concentration-dependent against two levels of TNF-α. The final readout in Caco-2 monolayers was at the more important protein level of three inflammatory cytokines, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β: polarised secretion to the basolateral bath in response to TNF-α was significantly reduced at low concentrations of dexamethasone in the conjugates. Importantly, unconjugated pDMAEMA did not affect marker expression (NURR1 and ICAM-1) or protein production of any of the three inflammatory cytokines.

Although the molecular weight of dexamethasone bromoacetate is approximately 200 Da more than dexamethasone, no significant difference in Papp was found between the two when tested on E12 monolayers (data not shown). Importantly, the Papp of dexamethasone bromoacetate across E12 exposed to NAC (2.0×10−5cm/s) was also similar to that of dexamethasone reported in Caco-2, (0.9×10−5cm/s) [47], values indicative of passive transcellular transport. As dexamethasone is a moderately hydrophobic molecule with a log D of 1.95, the mucus gel should present a flux barrier to it, and this has already been demonstrated in E12 for barbiturates and testosterone [22]. The flux of free dexamethasone bromoacetate across E12 and NAC-treated E12 was therefore investigated and the mucus gel was confirmed to be a significant barrier since there was a 4-fold increase in flux in the presence of the mucolytic to yield the ‘non-mucus’ Caco-2-like Papp value.

pDMAEMA has been shown to localise within the mucus gel layer when adhering to E12 monolayers and dexamethasone will therefore be released in that milieu. Both free dexamethasone and dexamethasone from P20 had a significantly higher Papp than dexamethasone from P10. This would be expected, as although the levels of mucoadhesion for both conjugate polymers are similar, the P20 conjugate has twice as many dexamethasone molecules attached. There was no difference between the Papp of free dexamethasone and dexamethasone in P20 across E12. This is important when considering the percentage of conjugate that bound to the mucus gel. It may suggest that a lower concentration of dexamethasone in conjugate format could give the same level of absorption as free dexamethasone. In NAC-treated E12 monolayers, free dexamethasone Papp was significantly higher than the Papp of dexamethasone released from either conjugate. The Papp of dexamethasone from P10 was significantly higher than from P20 across NAC-treated E12. Again, this may be explained by the higher level of bioadhesion seen with 10% dexamethasone-pDMAEMA conjugates than P20. In conditions of inflammation, epithelial mucus may be absent or compromised [48–50], so an ideal topical delivery system would show both mucoadhesive and bioadhesive properties. The conjugates offer the potential to transport dexamethasone across mucus-covered epithelial monolayers more efficiently than free dexamethasone. Combinations of both P10 and P20 may be a strategy for targeting epithelial surfaces with compromised mucus gels.

In summary, dexamethasone-conjugated methacrylate polymers were shown to offer advantages in mucosal delivery over free dexemethasone. Dexamethasone-conjugated pDMAEMA was shown to be bioactive and mucoadhesive. Dexamethasone was shown indirectly to be cleaved from the polymer, as suggested by pharmacodynamic read-outs and fluxes across mucus-covered epithelial monolayers. This suggests that pDMAEMA conjugation may be a useful tool for the localised delivery of hydrophobic compounds across epithelia.

References

- 1.Luessen HL, de Leeuw BJ, Langemeyer MW, de Boer AB, Verhoef JC, Junginger HE. Mucoadhesive polymers in peroral peptide drug delivery, VI. rbomer and chitosan improve the intestinal absorption of the peptide drug buserelin in vivo. Pharm. Res. 1996;13:1668–1672. doi: 10.1023/a:1016488623022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeuchi H, Yamamoto H, Kawashima Y. Mucoadhesive nanoparticulate systems for peptide drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;47:39–54. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawashima Y, Yamamoto H, Takeuchi H, Kuno Y. Mucoadhesive DL-lactide/glycolide copolymer nanospheres coated with chitosan to improve oral delivery of elcatonin. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2000;5:77–85. doi: 10.1081/pdt-100100522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehr CM, Bouwstra JA, Kok W, De Boer AG, Tukker JJ, Verhoef JC, Breimer DD, Junginger HE. Effects of the mucoadhesive polymer polycarbophil on the intestinal absorption of a peptide drug in the rat. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992;44:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb03633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehr CM, Bouwstra JA, Schacht EH, Junginger HE. In vitro evaluation of mucoadhesive properties of chitosan and some other natural polymers. Int. J. Pharm. 1992;78:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keely S, Rullay A, Wilson C, Carmichael A, Carrington S, Corfield A, Haddleton DM, Brayden DJ. In vitro and ex vivo intestinal tissue models to measure mucoadhesion of poly (methacrylate) and N-trimethylated chitosan polymers. Pharm. Res. 2005;22:38–49. doi: 10.1007/s11095-004-9007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:514–521. doi: 10.1172/JCI30587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braunlin W, Xu Q, Hook P, Fitzpatrick R, Klinger JD, Burrier R, Kurtz CB. Toxin binding of tolevamer, a polyanionic drug that protects against antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Biophys J. 2004;87:534–539. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu L, Zaborina O, Zaborin A, Chang EB, Musch M, Holbrook C, Shapiro J, Turner JR, Wu G, Lee KY, Alverdy JC. High-molecular-weight polyethylene glycol prevents lethal sepsis due to intestinal Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:488–498. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batchelor HK, Tang M, Dettmar PW, Hampson FC, Jolliffe IG, Craig DQ. Feasibility of a bioadhesive drug delivery system targeted to oesophageal tissue. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004;57:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keely S, Rawlinson LA, Haddleton DM, Brayden DJ. A tertiary amino-containing polymethacrylate polymer protects mucus-covered intestinal epithelial monolayers against pathogenic challenge. Pharm. Res. 2008;25:1193–1201. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friend DR. New oral delivery systems for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57:247–265. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedorak RN, Haeberlin B, Empey LR, Cui N, Nolen H, 3rd, Jewell LD, Friend DR. Colonic delivery of dexamethasone from a prodrug accelerates healing of colitis in rats without adrenal suppression. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1688–1699. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friend DR, Phillips S, McLeod A, Tozer TN. Relative anti-inflammatory effect of oral dexamethasone-beta-D-glucoside and dexamethasone in experimental inflammatory bowel disease in guinea-pigs. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1991;43:353–355. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb06703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielson OH, Munck LK. Drug insight: aminosalicylates for the treatment of IBD. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;4:160–170. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazzaniga A, Maroni A, Sangalli ME, Zema L. Time-controlled oral delivery systems for colonic targeting. Ex. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006;3:583–597. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limer AJ, Rullay AK, Miguel VS, Peinado C, Keely S, Fitzpatrick E, Carrington SD, Brayden D, Haddleton DM. Fluorescently-tagged star polymers by living radical polymerisation for mucoadhesion and bioadhesion. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2006;66:51–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haddleton DM, Crossman MC, Duncalf BHDJ, Heming AM, Kukulj D, Shooter A. Atom transfer polymerization of methyl methacrylate mediated by alkylpyridylmethanimine type ligands, copper(I) bromide, and alkyl halides in hydrocarbon solution. Macromolecules. 1999;32:2110–2119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisz A, Buzard RL, Horn D, Li MP, Dunkerton LV, Markland FS., Jr Steroid derivatives for electrophilic affinity labelling of glucocorticoid binding sites: interaction with the glucocorticoid receptor and biological activity. J. Steroid Biochem. 1983;18:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(83)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkerton LV, Markland FS, Li MP. Affinity-labelling corticoids. I. Synthesis of 21-chloroprogesterone, deoxycorticosterone 21-(1-imidazole) carboxylate 1-deoxy-1-chloro dexamethasone, and dexamethasone 21-mesylate-1-bromoacetate, and 21-iodoacetate. Steroids. 1982;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(82)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Artursson P. Epithelial transport of drugs in cell culture. I: A model for studying the passive diffusion of drugs over intestinal absorptive (Caco-2) cells. J. Pharm Sci. 1990;79:476–482. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600790604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behrens I, Stenberg P, Artursson P, Kissel T. Transport of lipophilic drug molecules in a new mucus-secreting cell culture model based on HT29-MTX cells. Pharm. Res. 2001;18:1138–1145. doi: 10.1023/a:1010974909998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korzeniewski C, Callewaert DM. An enzyme-release assay for natural cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;64:313–320. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubatsch I, Ragnarsson EG, Artursson P. Determination of drug permeability and prediction of drug absorption in Caco- monolayers. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2111–2119. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralph JA, McEvoy AN, Kane D, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O, Murphy EP. Modulation of orphan nuclear receptor NURR1 expression by methotrexate in human inflammatory joint disease involves adenosine A2A receptor-mediated responses. J. Immunol. 2005;175:555–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ImageJ Software. Bethesda, Maryland, USA: U S National Institutes of Health; [Accessed July, 2008]. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dippold W, Wittig B, Schwaeble W, Mayet W, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1, CD54) in colonic epithelial cells. Gut. 1993;34:1593–1597. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marion-Letellier R, Butler M, Dechelotte P, Playford RJ, Ghosh S. Comparison of cytokine modulation by natural peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands with synthetic ligands in intestinal-like Caco-2 cells and human dendritic cells-potential for dietary modulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in intestinal inflammation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87:939–948. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Street ME, Miraki-Moud F, Sanderson IR, Savage MO, Giovannelli G, Bernasconi S, Camacho-Hubner C. Interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and IL-6 modulate insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP) secretion in colon cancer epithelial (Caco-2) cells. J. Endocrinol. 2003;79:405–415. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1790405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smart JD. Recent developments in the use of bioadhesive systems for delivery of drugs to the oral cavity. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2004;21:319–344. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v21.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smart JD. The basics and underlying mechanisms of mucoadhesion. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57:1556–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaur IP, Kapil M, Smitha R, Aggarwal D. Development of topically effective formulations of acetazolamide using HP-beta-CD-polymer co-complexes. Curr Drug Deliv. 2004;1:65–72. doi: 10.2174/1567201043480054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones DS, Muldoon BC, Woolfson AD, Sanderson FD. An examination of the rheological and mucoadhesive properties of poly(acrylic acid) organogels designed as platforms for local drug delivery to the oral cavity. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2632–2646. doi: 10.1002/jps.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baumgart D, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seow CH, Benchimol EI, Griffiths AM, Otley AR, Steinhart AH. Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD000296. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000296.pub3. PMID: 18646064 [PubMed - in process] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boivin MA, Ye D, Kennedy JC, Al-Sadi R, Shepela C, Ma TY. Mechanism of glucose regulation of the intestinal tight junction barrier. Am. J. Physiol. 2007;292:G590–G598. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00252.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corfield AP, Wagner SA, O'Donnell LJ, Durdey P, Mountford RA, Clamp JR. The roles of enteric bacterial sialidase, sialate O-acetyl esterase and glycosulfatase in the degradation of human colonic mucin. Glycoconj J. 1993;10:72–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00731190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fluge G, Andersen KJ, Aksnes L, Thunold K. Brush border and lysosomal marker enzyme profiles in duodenal mucosa from coeliac patients before and after organ culture. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1982;17:465–472. doi: 10.3109/00365528209182233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krauland AH, Guggi D, Bernkop-Schnurch A. Oral insulin delivery: the potential of thiolated chitosan-insulin tablets on non-diabetic rats. J. Control. Release. 2004;95:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai JP, Chang LL, Guo H. Effects of polyacrylic polymers on the degradation of insulin and peptide drugs by chymotrypsin and trypsin. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1996;48:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb05869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guggi D, Bernkop-Schnurch A. In vitro evaluation of polymeric excipients protecting calcitonin against degradation by intestinal serine proteases. Int. J. Pharm. 2003;252:187–196. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00631-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laurent A, Debart F, Lamb N, Rayner B. Esterase-triggered fluorescence of fluorogenic oligonucleotides. Bioconjug Chem. 1997;8:856–861. doi: 10.1021/bc970168i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider W, Shyamala G. Glucocorticoid receptors in primary cultures of mouse mammary epithelial cells: characterization and modulation by prolactin and cortisol. Endocrinology. 1985;116:2656–2662. doi: 10.1210/endo-116-6-2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies MR, Harding CJ, Raines S, Tolley K, Parker AE, Downey-Jones M, Needham MR. Nurr1-dependent regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators in immortalised synovial fibroblasts. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 2005;2:15–22. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dippold W, Wittig B, Schwaeble W, Mayet W, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1, CD54) in colonic epithelial cells. Gut. 1993;34:1593–1597. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holla VR, Mann JR, Shi Q, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 regulates the nuclear receptor NR4A2 in colorectal cancer. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2676–2682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507752200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leonard M, Creed E, Brayden D, Baird AW. Evaluation of the Caco-2 monolayer as a model epithelium for iontophoretic transport. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1181–1188. doi: 10.1023/a:1026454427621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Owen DA, Reid PE. Histochemical alterations of mucin in normal colon, inflammatory bowel disease and colonic adenocarcinoma. Histochem. J. 1995;27:882–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagel E, Schattenfroh S, Buhner S, Bartels M, Guthy E, Pichlmayr R. Experimental damage of the epithelial layer of the ileum by dietary fats: transmission electron microscopy findings and their comparison with cell pathology in Crohn disease. Z. Gastroenterol. 1992;30:403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trabucchi E, Mukenge S, Baratti C, Colombo R, Fregoni F, Montorsi W. Differential diagnosis of Crohn's disease of the colon from ulcerative colitis: ultrastructure study with the scanning electron microscope. Int. J. Tissue React. 1986;8:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]