Abstract

Objective

To determine the impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on smoking prevalence in Australian adults.

Methods

Data for calculating the average monthly prevalence of smoking between January 2001 and June 2011 were obtained via structured interviews of randomly sampled adults aged 18 years or older from Australia’s five largest capital cities (monthly mean number of adults interviewed: 2375). The influence on smoking prevalence was estimated for increased tobacco taxes; strengthened smoke-free laws; increased monthly population exposure to televised tobacco control mass media campaigns and pharmaceutical company advertising for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), using gross ratings points; monthly sales of NRT, bupropion and varenicline; and introduction of graphic health warnings on cigarette packs. Autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models were used to examine the influence of these interventions on smoking prevalence.

Findings

The mean smoking prevalence for the study period was 19.9% (standard deviation: 2.0%), with a drop from 23.6% (in January 2001) to 17.3% (in June 2011). The best-fitting model showed that stronger smoke-free laws, tobacco price increases and greater exposure to mass media campaigns independently explained 76% of the decrease in smoking prevalence from February 2002 to June 2011.

Conclusion

Increased tobacco taxation, more comprehensive smoke-free laws and increased investment in mass media campaigns played a substantial role in reducing smoking prevalence among Australian adults between 2001 and 2011.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer l'impact des politiques de lutte contre le tabagisme et des campagnes médiatiques sur la prévalence du tabagisme chez les adultes en Australie.

Méthodes

Les données de calcul de la prévalence mensuelle moyenne du tabagisme entre janvier 2001 et juin 2011 ont été obtenues par le biais d'entretiens structurés avec des adultes âgés de 18 ans ou plus et sélectionnés au hasard dans les cinq plus grandes métropoles d'Australie (nombre moyen mensuel d'adultes interrogés: 2375). L'influence sur la prévalence du tabagisme a été estimée pour l'augmentation des taxes sur le tabac; le renforcement des lois antitabac; l'augmentation de l'exposition mensuelle de la population aux campagnes télévisuelles de lutte contre le tabagisme et aux publicités des sociétés pharmaceutiques pour la thérapie de substitution de la nicotine (TSN), en utilisant des indicateurs de pression des médias; les ventes mensuelles de TSN, de bupropion et de varénicline; et l'ajout de textes et d'images de mise en garde sur les paquets de cigarettes. Des modèles autorégressifs de moyennes mobiles (Autoregressive integrated moving average, ARIMA) ont été utilisés pour étudier l'influence de ces interventions sur la prévalence du tabagisme.

Résultats

La prévalence moyenne du tabagisme pour la période étudiée était de 19,9% (écart-type: 2,0%), avec une baisse de 23,6% (en janvier 2001) à 17,3% (en juin 2011). Le modèle le mieux adapté a montré que le renforcement des lois antitabac, la hausse du prix du tabac et une plus forte exposition aux campagnes médiatiques expliquaient à eux seuls 76% de la diminution de la prévalence du tabagisme de février 2002 à juin 2011.

Conclusion

L'augmentation des taxes sur le tabac, des lois antitabac plus globales et la hausse des investissements dans les campagnes médiatiques ont joué un rôle important dans la réduction de la prévalence du tabagisme chez les adultes en Australie entre 2001 et 2011.

Resumen

Objetivo

Determinar el impacto de las estrategias de control del tabaco y de las campañas en los medios de comunicación sobre la prevalencia del tabaquismo en los adultos australianos.

Métodos

Entre enero de 2001 y junio de 2011 se recopilaron datos para calcular la prevalencia mensual media del tabaquismo a través de entrevistas estructuradas a sujetos adultos de 18 o más años de edad de las cinco ciudades más grandes de Australia seleccionados aleatoriamente (promedio de personas entrevistadas mensualmente: 2375). La influencia en la prevalencia del tabaquismo se calculó en base a un aumento de los impuestos del tabaco, el fortalecimiento de las leyes antitabaco, una exposición mensual mayor de la población a campañas televisadas dirigidas a controlar el tabaco en los medios de comunicación y la publicidad de una compañía farmacéutica de una terapia de sustitución de nicotina (TSN) por medio de puntos de audiencia bruta, ventas mensuales de TSN, bupropión y vareniclina, así como la introducción de advertencias gráficas sobre la salud en los paquetes de cigarrillos. Se emplearon modelos autorregresivos integrados de media móvil (ARIMA) para examinar la influencia de dichas intervenciones en la prevalencia del tabaquismo.

Resultados

La prevalencia media del tabaquismo en el periodo de estudio fue del 19,9 % (desviación estándar: 2,0 %), con una caída del 23,6 % (en enero de 2001) al 17,3 % (en junio de 2011). El modelo mejor ajustado mostró que las leyes antitabaco más estrictas, el aumento del precio del tabaco y una mayor exposición a las campañas en los medios de comunicación explicaron de forma independiente el 76 % de la disminución de la prevalencia del tabaquismo entre febrero de 2002 y junio de 2011.

Conclusión

El aumento de los impuestos sobre el tabaco, leyes antitabaco más amplias y una mayor inversión en campañas en los medios de comunicación desempeñaron un papel fundamental en la reducción de la prevalencia del tabaquismo entre las personas adultas de Australia entre 2001 y 2011.

ملخص

الغرض

تحديد أثر سياسات مكافحة التبغ وحملات وسائل الإعلام على معدل انتشار التدخين لدى البالغين في أستراليا.

الطريقة

تم الحصول على البيانات لحساب متوسط معدل الانتشار الشهري للتدخين في الفترة من كانون الثاني/ يناير 2001 وحزيران/ يونيو 2011 عن طريق إجراء مقابلات منظمة لعينات عشوائية من البالغين في سن 18 عاماً فأكثر من أكبر خمس عواصم في أستراليا (متوسط عدد البالغين الشهري الذين تم مقابلتهم: 2375 شخصاً). وتم تقدير التأثير على معدل انتشار التدخين بالنسبة لزيادة الضرائب على التبغ؛ وتعزيز قوانين منع التدخين؛ وزيادة تعرض السكان الشهري لحملات وسائل الإعلام المتلفزة الخاصة بمكافحة التبغ والشركة الصيدلانية التي تعلن عن العلاج ببدائل النيكوتين (NRT)، باستخدام نقاط التقييم الإجمالية؛ ومبيعات العلاج ببدائل النيكوتين الشهرية والبوبروبيون والفارينيكلين؛ ووضع رسوم التحذيرات الصحية على عبوات السجائر. وتم استخدام نماذج للمتوسطات المتحركة المتكاملة للارتداد التلقائي (ARIMA) لدراسة تأثير هذه التدخلات على معدل انتشار التدخين.

النتائج

بلغ متوسط معدل انتشار التدخين في فترة الدراسة 19.9 % (الانحراف المعياري: 2.0 %) بالانخفاض من 23.6 % (في كانون الثاني/ يناير 2001) إلى 17.3 % (في حزيران/ يونيو 2011). وأظهر أنسب نموذج أن 76 % من الانخفاض في معدل انتشار التدخين في الفترة من شباط/ فبراير 2002 إلى حزيران/ يونيو 2011 يرجع بشكل مستقل إلى قوانين منع التدخين القوية والزيادات في أسعار التبغ وزيادة التعرض إلى حملات وسائل الإعلام.

الاستنتاج

لعبت زيادة الضرائب على التبغ وقوانين مكافحة التدخين الأكثر شمولية وزيادة الاستثمار في حملات وسائل الإعلام دوراً كبيراً في تقليل معدل انتشار التدخين بين البالغين في أستراليا في الفترة من 2001 إلى 2011.

摘要

目的

确定烟草控制政策和大众媒体宣传运动对澳大利亚成年人吸烟率的影响。

方法

通过澳大利亚最大的五个首府城市18岁及以上随机采样成年人结构化面访获取数据,用来计算2001年1月至2011年6月平均每月吸烟率(每月面访的平均成年人数:2375)。针对增加烟草税、加强禁烟立法、扩大每月电视烟草控制大众媒体宣传运动以及尼古丁替代疗法(NRT)制药公司广告受众范围(使用总收视率计算)、每月NRT、安非他酮和伐伦克林销量以及在烟盒上印制图形健康警语等方面评估对吸烟率的影响。使用自回归求积移动平均(ARIMA)模型考查这些吸烟率干预措施的影响。

结果

研究期间平均吸烟率为19.9%(标准偏差:2.0%),从23.6%(2001年1月)降低至17.3%(2011年6月)。最优拟合模型显示,更强的禁烟立法、烟草价格上涨和扩大大众媒体宣传运动覆盖面单独解释了2002年2月至2011年6月吸烟率减少幅度的76%。

结论

更高的烟草税收、更全面的禁烟立法和大众传媒活动方面的更大投入在2001年至2011年间减少澳大利亚成年人吸烟率方面发挥了重要作用。

Резюме

Цель

Определить влияние стратегий по борьбе против табака и кампаний в средствах массовой информации на распространенность курения среди взрослого населения Австралии.

Методы

Данные для расчета среднемесячных уровней распространенности курения в период с января 2001 года по июнь 2011 года были получены с помощью структурированных интервью, проведенных по принципу случайной выборки среди взрослого населения в возрасте 18 лет и старше, проживающего в 5 крупнейших городах Австралии (среднемесячная численность опрошенного взрослого населения: 2375). Влияние на распространенность курения оценивалось по увеличению налогов на табачные изделия, усилению законов о запрете курения, повышеной интенсивности ежемесячных трансляций по телевидению кампаний в СМИ по борьбе против табака и рекламы фармацевтической компании, предлагающей никотинзаместительную терапию (НЗТ), с использованием общего рейтинга просмотра телепередач, ежемесячным продажам услуг НЗТ, бупропиона и варениклина, а также по обязательному размещению на пачках сигарет графических предупреждений о вреде курения. Для изучения влияния этих мер на распространенность курения использовались авторегрессионные интегрированныемоделискользящей средней(ARIMA).

Результаты

Средняя распространенность курения на период исследования составила 19,9% (стандартное отклонение: 2,0%), снизившись с 23,6% (в январе 2001 г.) до 17,3% (в июне 2011 г.). Уточненная модель показала, что более строгие законы о запрете курения, повышение цен на табак и более активное проведение кампаний в СМИ независимо привели к снижению распространенности курения на 76% с февраля 2002 года по июнь 2011 года.

Вывод

Повышение налогов на табачные изделия, всеобъемлющее антитабачное законодательство и увеличение инвестиций в кампании в средствах массовой информации сыграли существенную роль в снижении распространенности курения среди взрослого населения Австралии в период с 2001 по 2011 годы.

Introduction

If current trends continue, tobacco use will cause about 1 billion premature deaths during the 21st century,1 80% of them in low- and middle-income countries. Reducing the prevalence of smoking among adults is imperative both to reduce mortality in the short to medium term2 and to change the normative environment in which young people aspire to smoke.3

Much of the evidence supporting strategies articulated in the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control4 comes from high-income countries that have had the resources to study the influence of such policies on population-level tobacco use. Australia, with a population of approximately 23 million in 2001, is a country with a track record as an early adopter of tobacco control policies and a steady decline in smoking prevalence.1,5,6 The experience of countries such as Australia provides important lessons for other countries that are assessing potential tobacco control policies and mass media campaign interventions in which to invest.7,8

The current study is based on a data series that allowed quantification of changes in monthly smoking prevalence over 11 years, adjustment for seasonality of measurement and assessment of the effects of a comprehensive set of tobacco control policies and media campaign exposures. In this study we consider the influence of policies that are intended to increase in strength over time (i.e. those involving graduated smoke-free policies and bans on tobacco advertising) and of policies that can change dynamically over time (i.e. those influencing the amount of exposure to mass media campaigns, the real price of tobacco and the sale of pharmaceutical products for smoking cessation). We build on and update methods established in an earlier time series analysis by our group9 that suggested that increased tobacco price and greater exposure to mass media campaigns accounted for almost half the decrease in the observed prevalence of smoking in Australia during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Methods

Population survey data

Using methods published elsewhere, we estimated the prevalence of smoking from January 2001 to June 2011 from data collected in a weekly omnibus survey of a random sample of Australians residing in the five largest capital cities: Sydney, Melbourne, Perth, Adelaide and Brisbane. In each city, federal electorates were used as strata for sampling, since enrolment on the electoral roll is compulsory in Australia among individuals aged 18 years or older. Each electoral area was divided into four sampling sections of roughly equal population size and data were obtained from one section per week on a rotating basis, with starting addresses selected at random from the electoral roll. One person per household was interviewed; interviewers were instructed to initially ask to speak to the youngest male aged 14 years or older and, if unavailable, to then speak to the youngest female aged 14 years or older. Up to three call-back visits were made to each selected household. The mean response rate, measured as completed interviews out of all effective contacts, was 31%. Survey data were weighted by capital city, age, sex and household size to the Australian urban population aged 14 years or older, using Australian Bureau of Statistics census data. For the current study we only retained and analysed data for individuals who were at least 18 years of age to allow for the matching of media monitoring company estimates of adult exposure (≥ 18 years) to mass media campaigns.

Weekly survey data from Australia’s five largest capital cities, where 61% of the country’s adult population resides,10 were cumulated to yield monthly estimates of the smoking prevalence among individuals aged 18 years or older. Overall, 299 287 interviews were performed; a mean of 2375 participants (range: 2053‒2725) completed the structured interview each month.

Smokers were defined as those who responded “yes” to one of the following questions: “Do you now smoke factory-made cigarettes?” and “In the last month, have you smoked any roll-your-own cigarettes (of tobacco)?”

Exposure to mass media campaigns

Tobacco control mass media campaigns funded by the Australian government have generally targeted adult smokers and most have emphasized the serious health harms from smoking through the use of graphic images, personal emotive stories or simulated demonstrations of health effects. Most advertising is tagged with a Quitline number and/or website address where smokers can access help with smoking cessation. Advertising from pharmaceutical companies was for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) only: direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription medicines, such as bupropion and varenicline, is not permitted in Australia.

Occurrences of all televised tobacco control and NRT advertisements for each capital city media market were acquired from a media monitoring company. Data on exposure to such advertising are based on individual television programme ratings obtained by monitoring household audiences across media markets.11 Ratings provide an estimate of the percentage of households with individuals who watch a television programme in a media market over a specified interval. The advertising exposure measure is based on gross ratings points (GRPs) per month for the population aged 18 years or older, with 100 GRPs being equal to a mean of one potential advertisement exposure per month for all adults within a media market. GRPs represent mean potential exposure: actual exposure for any given individual would vary on the basis of the frequency of actual television viewing and attention to the advertisements.

To enable analysis at the national level, we re-scaled the GRPs according to the percentage of the population living in each state in each year (e.g. since 26% of the population lived in the state of Victoria in 2011, monthly GRPs in Victoria for this year were multiplied by 0.26).

Tobacco control policies

Tobacco prices

An indicator of cigarette costliness was calculated as the percentage of mean weekly income that a packet of cigarettes cost. Using the bimonthly trade publication The Australian retail tobacconist, we calculated the mean of the recommended retail price of the two top-selling Australian brands in the most popular pack sizes (Peter Jackson 30s and Winfield 25s) for each state over the period. A comprehensive study of tobacco prices indicated that recommended prices were lower than actual prices, but by a consistent margin over the course of the study.12,13 We obtained quarterly estimates of employee gross mean weekly earnings in each state, projected to the total population.14 Both tobacco price and income data were matched at the state level and then national estimates were calculated.

Smoke-free policies

The degree of implementation of smoke-free policies in restaurants, venues licensed to sell alcohol (hotels, clubs and bars), workplaces, shopping centres and gambling venues (excluding so-called high roller rooms) was assessed using a score of 0 for absent, 0.5 for partially implemented and 1 for fully implemented.15 Scores for each smoke-free policy were calculated as mean values for each state. State scores were then weighted according to the percentage of the population living in each state in each year and summed to obtain a national score.

Point-of-sale advertising and display bans

The degree of implementation of bans on the advertising and display of cigarettes at the point of sale15 was assessed using a score of 0 for no ban, 0.5 for a partial ban and 1 for a total ban. A mean score for these two policies was created for each state. State scores were then weighted according to the percentage of the population living in each state in each year and summed to form a national score.

Graphic health warnings

Beginning in March 2006, the Australian government implemented legislation requiring all tobacco products to feature one of 14 pictorial warnings about the harms of tobacco use. The warning had to cover 30% of the front and 90% of the back of the pack.16,17 By July 2006, 50% of cigarette packs featured graphic health warnings.18 The introduction of graphic health warnings was coded as a binary variable (0 for before implementation of the legislation and 1 for after implementation). We examined March 2006 and July 2006 separately as implementation dates.

Pharmaceutical products for smoking cessation

Over-the-counter NRT was available throughout the study period. NRT was available for sale in supermarkets and convenience stores beginning in June 2006. From February 2011 onward, subsidized prescription of a 12-week supply of NRT patches was extended from war service veterans and indigenous Australians only, to include all adult Australian smokers.

Bupropion became available on prescription in November 2000, with the consumer cost subsidized by the government from February 2001 onward. In January 2008, varenicline became available on prescription, with consumer cost subsidized by the government for a 12-week course. This was extended to 24 weeks in February 2011. Monthly data for numbers of NRT, bupropion and varenicline units sold were obtained from IMS Health Australia. These data represent sales to pharmacies through wholesale channels and are estimated to cover more than 98% of the market.

Statistical analysis

Time series autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) analysis19,20 was used to estimate the effect of these tobacco control interventions on monthly smoking prevalence. We used the standard modelling strategy for time series analyses.19 Because monthly smoking prevalence exhibited a downward trend, first order differencing was used to transform the variable into a stationary series. Univariable ARIMA models were used, with one moving average term, to identify best-fitting transfer functions for each explanatory variable (i.e. to identify the manner in which past values of each explanatory variable [specified as a lag] are used to forecast future values of smoking prevalence). Multivariable ARIMA modelling was then used to jointly examine the influence of the explanatory variables on smoking prevalence, with least significant explanatory variables removed one at a time. We used parameter P-values and the Akaike information criterion to determine the final model.21 Models were assessed for stationarity and invertibility. All analyses were undertaken using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, United States of America).

Results

Sample characteristics

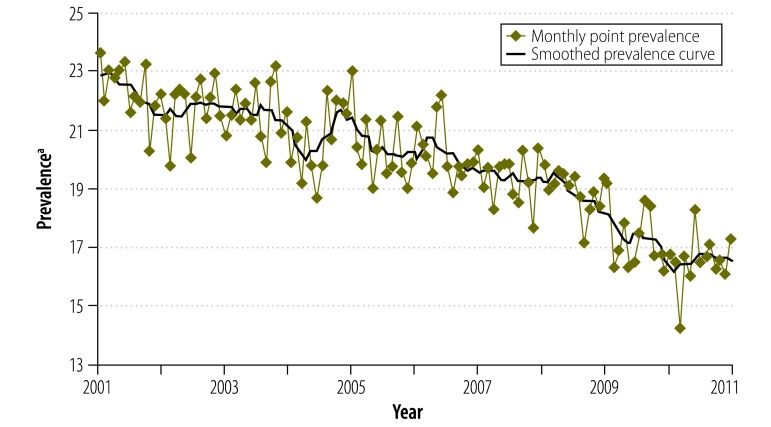

The mean smoking prevalence for the study period was 19.9% (standard deviation, SD: 2.0%), with a drop from 23.6% (in January 2001) to 17.3% (in June 2011; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Monthly smoking prevalence among Australian adults, January 2001 to June 2011

a Smokers per 100 respondents.

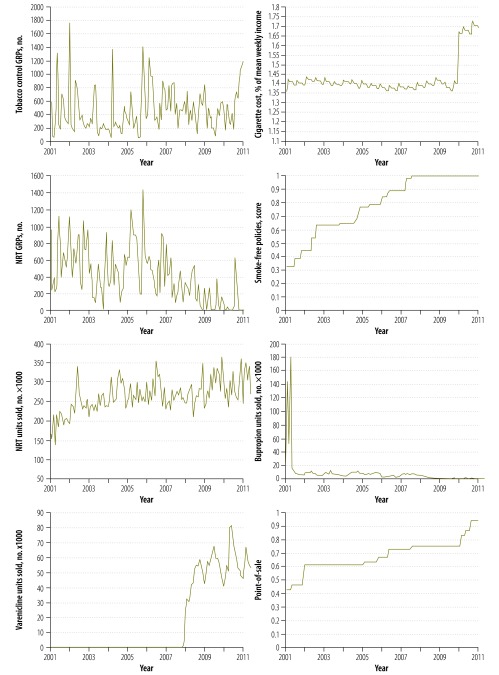

Table 1 and Fig. 2 show a median of 386 GRPs per month for tobacco control advertising and a median of 319 GRPs per month for NRT advertising. In January 2001, a pack of cigarettes cost 1.36% of employee gross mean weekly earnings. Cigarettes became more expensive over the study period, although the increase was not as dramatic as in the period covered by our earlier study.9 Price increased sharply following a 25% increase in tobacco excise tax in April 2010. In June 2011, the price of a cigarette pack represented 1.69% of gross mean weekly earnings.

Table 1. Measurements for tobacco control policies, mass media campaigns and pharmaceutical units sold, Australia, January 2001 to June 2011.

| Parameter | Median (IQR) | Minimum (time) | Maximum (time) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | |||

| Smoke-free policies, scorea-c | 0.84 (0.63–1.00) | 0.32 (up to Jun 2001) | 1.00 (Nov 2007 and after) |

| POS bans, scored-f | 0.67 (0.61–0.75) | 0.42 (up to Apr 2001) | 0.94 (Jul 2011 and after) |

| Cigarette priceg | 1.40 (1.38–1.41) | 1.36 (Jun 2006) | 1.72 (Feb 2011) |

| Mass media exposure | |||

| Tobacco control GRPs, no.h | 386.69 (218.20–598.17) | 42.54 (Oct 2005) | 1759.74 (Jan 2002) |

| NRT GRPs, no.h | 318.73 (147.34–612.64) | 0i | 1433.81 (Jan 2006) |

| Pharmaceutical units | |||

| Bupropion units sold, no. × 1000 | 6.20 (2.19–8.30) | 1.41 (Jan 2009) | 181.80 (Apr 2001) |

| NRT units sold, no. × 1000 | 257.60 (236.80–285.80) | 135.80 (Apr 2001) | 363.92 (Dec 2009) |

| Varenicline units sold, no. × 1000 | 0 (0–46.73) | 0 (up to Nov 2007) | 81.10 (Jun 2010) |

GRP: gross ratings point; IQR: interquartile range; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; POS: point of sale.

a Scores were defined as follows: 0 for absent, 0.5 for partially implemented and 1 for fully implemented.

b Data are population-weighted national sum scores; unweighted median, 4.2 (IQR: 3–5; range: 1.6–5).

c Complete restaurant smoking bans were implemented in South Australia (SA) from January 1999, in Western Australia (WA) from April 1999, in New South Wales (NSW) from September 2000, in Victoria (VIC) from July 2001 and in Queensland (QLD) from June 2002. Complete licensed venue smoking bans were implemented in QLD from July 2006, in WA from August 2006, in VIC and NSW from July 2007 and in SA from November 2007. Complete gambling venue bans were implemented in VIC from September 2002, in WA from December 2003, in QLD from July 2006, in NSW from July 2007 and in SA from November 2007. Complete enclosed workplace bans were implemented in WA from April 1999, in NSW from September 2000, in QLD from June 2002, in SA from December 2004 and in VIC from March 2006. Complete shopping centre smoking bans were implemented in WA from April 1999, in NSW from September 2000, in VIC from November 2001, in QLD from June 2002 and in SA from December 2004.

d Scores were defined as follows: 0 for no ban, 0.5 for partial ban and 1 for full ban.

e Data are population-weighted national sum scores; unweighted median, 3 (IQR: 2.5–3.75; range: 1.75–4.5).

f Exterior bans on POS advertising began before the study period, from January 1989, in VIC. WA was the final state to ban POS advertising, from August 2006. Complete bans on POS displays were implemented in WA from September 2010, in NSW from July 2010 and in VIC from January 2011. Partial bans were implemented in QLD from January 2006 and in SA from November 2007 (these were only complete after the study period).

g Data are cost of one cigarette pack, expressed as a percentage of mean weekly income.

h Data are total no. of GRPs per month. GRPs measure advertising exposure, where 100 GRPs are equal to a mean of one potential advertisement exposure per month for all adults within the media market.

i Nov 2003; Mar, Apr, Jun, Sep–Dec 2009; Mar, Jun–Jul, Sep–Nov 2010; Mar–Jun 2011.

Fig. 2.

Monthly values of tobacco control policies and media campaign exposures, Australia, January 2001 to June 2011

GRP: gross ratings point; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy.

Note: GRPs measure advertising exposure; 100 GRPs are equal to a mean of one potential advertisement exposure per month for all adults within the media market.

Smoke-free policies increased steadily; by November 2007, complete bans were in force in indoor public places across all states in Australia. Similarly, point-of-sale bans increased progressively over the study period. Median monthly sales of NRT and bupropion were 257 599 and 6200 units, respectively, although bupropion sales peaked sharply following its release, in 2001. The median monthly sale of varenicline after its introduction, in January 2008, was 54 100 units (interquartile range: 46 285–58 976).

Relation between policies and smoking prevalence

We found that the strength of point-of-sale bans was multicollinear with the strength of smoke-free policies. We elected to remove point-of-sale bans from further analysis because they did not predict smoking prevalence at the univariable level. Transfer functions for all variables (except the binary graphic health warning variable) were tested and the best-fitting transfer functions were selected for multivariable ARIMA modelling (Table 2). Of all possible influences of the graphic health warnings tested, a temporary influence, followed by gradual decay, provided the best fit in the univariable model with monthly smoking prevalence. There were no statistically significant differences in the results for graphic health warnings when March 2006 and July 2006 were used as the date of policy implementation; therefore, the ARIMA models use March 2006 as the date of introduction of graphic health warnings.

Table 2. Estimated percentage point changes in Australian adult smoking prevalence from January 2001 to June 2011, based on conditional least squares autoregressive integrated moving average models.

| Parameter (transfer function) | Estimated percentage point changes (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Smoke-free policies (4-month lag) | −4.00 (−7.49 to −0.52) | −4.22 (−7.65 to −0.79) | −4.34 (−7.81 to −0.87) | −4.18 (−7.28 to −1.08) | −4.65 (−8.51 to −0.80) | −5.34 (−9.56 to −1.12) | −5.31 (−9.53 to −1.10) |

| Cigarette price (immediate effect) | −3.77 (−7.62 to 0.08) | −3.78 (−7.65 to 0.08) | −3.71 (−7.59 to 0.17) | −3.86 (−7.61 to −0.11) | −3.35 (−7.38 to 0.67) | −3.83 (−7.85 to 0.20) | −4.02 (−8.04 to 0.01) |

| Tobacco control GRPsa (2-month lag) | −0.03 (−0.09 to 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.02) | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.01) | −0.05 (−0.11 to 0.004) | −0.05 (−0.11 to 0.003) | – |

| Varenicline units sold (1-month lag) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.01) | – | – |

| NRT units sold (1-month lag) | −0.003 (−0.01 to 0.002) | −0.004 (−0.01 to 0.001) | −0.004 (−0.01 to 0.002) | −0.004 (−0.01 to 0.002) | – | – | – |

| NRT GRPsa (2-month lag) | −0.03 (−0.11 to 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.04) | −0.04 (−0.11 to 0.03) | – | – | – | – |

| GHWs | |||||||

| Temporary impact | −0.32 (−1.13 to 0.49) | −0.32 (−1.12 to 0.48) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gradual decay | −0.96 (−1.12 to −0.79) | −0.96 (−1.12 to −0.79) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bupropion units sold (1-month lag) | 0.002 (−0.005 to 0.01) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Moving average (1-month lag [θ1])b | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.97) | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.97) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.97) | 0.88 (0.79 to 0.98) | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.94) | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.71 to 0.92) |

CI: confidence interval; GHW: graphic health warning; GRP: gross ratings point; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy.

a GRPs measure advertising exposure, where 100 GRPs are equal to a mean of one potential advertisement exposure per month for all adults within the media market. Tobacco control GRPs and NRT GRPs were re-scaled so that the estimates from the time series autoregressive integrated moving average modelling represent the change in monthly smoking prevalence associated with a change of 100 GRP units.

b This parameter accounts for the effects of time.

Note: The best-fitting model was determined to be model 6, on the basis of P-values and Akaike information criterion values.

Multivariable ARIMA models (i.e. models 1–5) were conducted using the identified transfer functions. During this analytic process, we progressively removed bupropion units sold, graphic health warnings, NRT GRPs, NRT units sold and varenicline units sold because of non-significance in these models. Although tobacco control GRPs and cigarette price had P-values of > 0.05 in model 6, the Akaike information criterion indicated that this model had a better fit than model 7 (353.68 versus 355.21), in which tobacco control GRPs were removed. Further, both cigarette price and tobacco control GRPs had a considerable influence on reducing monthly smoking prevalence, based on the magnitude of their estimates from model 6 (Table 2).

The best-fitting model (model 6) showed an effect for smoke-free policies four months after exposure, an effect for tobacco control GRPs two months after exposure and an effect for cigarette price immediately after a change occurred. Using the best-fitting model to forecast smoking prevalence from February 2002, we estimated that these three variables accounted for a drop of approximately 4.6 percentage points in prevalence, or about 76% of the decrease in smoking prevalence, to June 2011. February 2002 was selected as the start date to allow sufficient data (12 months of data) from which to determine forecast estimates (i.e. January 2001 to January 2002 values used to forecast smoking prevalence for February 2002, and so on). The chosen time frame used to generate the forecast is consistent with our previous analysis.9 Alternatively, these findings can be expressed as the required increase in policy intensity necessary for a given change in smoking prevalence. For a 0.30 percentage point decrease in prevalence, the score assigned to smoke-free policies would need to have increased by a value of 0.06 four months earlier. Such an increase in score could be achieved by extending a restaurant-only ban to pubs and bars in one highly populated state. An immediate 0.30 percentage point decrease in prevalence would be expected from a pack of cigarettes increasing in price by 0.08% of mean weekly income. In June 2011, this meant an increase from 17.35 to 18.16 Australian dollars in the mean cost of a pack of cigarettes (from 1.69% to 1.76% of mean weekly income). A 555-point increase in monthly GRPs two months earlier – equivalent to each person viewing five to six extra advertisements per month – would be required to achieve a 0.30 percentage point decrease in smoking prevalence. There were no interactions between cigarette price, tobacco control GRPs or smoke-free policies, which shows that the effects of these policies were additive and independent of each other.

In sensitivity analyses, we ran a forward selection modelling procedure in which model 1 included tobacco control GRPs and price, as per our previous article,9 with significant univariable predictors being added one at a time. This approach showed that the best-fitting model was identical to model 6 from the backward selection process. In addition, we tested binary coded versions of bupropion (during or before April 2001 coded as 1 and after April 2001 coded as 0) and varenicline units sold (coded as 1 from January 2008). The best model was again identical to model 6.

Discussion

We found that stronger smoke-free laws, tobacco price increases and greater exposure to televised mass media campaigns were independently associated with reduced smoking prevalence. Together these interventions accounted for three quarters of the prevalence decrease between 2002 and 2011.

Our findings are broadly consistent with those of other studies that have assessed the influence of smoke-free laws,22–24 although studies from some countries have revealed no change,24,25 perhaps because of data limitations or a differing rate of incremental policy change. Smoke-free policies result in fewer opportunities to smoke and send a clear message about the declining social acceptability of smoking.26 Such policies were found to be directly related to the decline in smoking prevalence among young people in Australia.15 Smoke-free laws became notably stronger over the period of study but there is limited scope for further restrictions in future years. By comparison, governments could increase the price of tobacco products and implement continuous mass media campaigns to reduce smoking prevalence.

Consistent with findings from the published literature,27–29 tobacco price was again a strong contributor to the observed reduction in smoking prevalence. Our finding concurs with the results of two recent studies in which the 25% tax increase in April 2010 was found to be associated with increased quitting activity among smokers in New South Wales, Australia.30,31

Greater exposure to televised mass media campaigns directly contributed to reduced prevalence. The magnitude and form of this relationship were consistent with the findings of prior analyses9 in that effects were produced relatively quickly (within two months) but dissipated when the advertisements went off the air. This suggests that campaigns need to be aired repeatedly to generate lasting effects. However, airing mass media campaigns is costly and funds for this are scarce. Hence, studies assessing the effects of different levels of exposure to mass media campaigns are needed to inform public health organizations about the optimum level of advertising. Our results suggest that Australia’s investment in mass media campaigns is still contributing substantially to reduced prevalence, as might be expected from the broader literature on the importance of mass media campaigns for reducing smoking among adults.32–34

Several tobacco control policies were unrelated to smoking prevalence. We recognize that some policies are likely to exert effects that increase the likelihood of wholesale behavioural change only at a later date. For example, the introduction of graphic health warnings has been associated in cohort studies with an increase in quitting cognitions and in the foregoing of cigarettes,35 both of which have been shown to predict quitting and relapse activity.36–38 It is possible that as long as graphic health warnings on cigarette packs appear with powerful branding, brand identity and consumer loyalty might revive at the expense of enduring effects of graphic health warnings on current smokers.39,40

We found that increased availability of smoking cessation medications was not statistically associated with smoking prevalence. However, smoking cessation products are part of a clinical strategy designed to increase the likelihood of successful cessation among the subset of smokers who are already motivated to make a quitting attempt, but they are not the primary motivator for making the attempt.9,41 We therefore acknowledge that the influence of such a clinical strategy, if present, would be difficult to detect at the population level.

We found no statistically significant effect of point-of-sale bans on smoking prevalence, although complete point-of-sale display bans in all states were achieved only after the end of the study period. Our measures of the strength of point-of-sale bans were based on the assumption that a higher score would represent less exposure, but in practise the tobacco industry has ensured continued, widespread population exposure to marketing messages by using other, compensatory media,42 with 40% of Australian smokers reporting having noticed tobacco advertising in at least one of five channels as late as 2006.43 For example, once point-of-sale advertising was restricted by legislation, it was replaced with larger and more colourful cigarette pack displays;44 bans on cigarette displays were then followed by more varied, colourful and appealing cigarette packaging designs.45 Attractive packaging disappeared and marketing messages on packs were more tightly restricted with implementation of Australia’s plain packaging legislation on 1 December 2012.46

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Response rates were relatively low, but it has been shown that low response rates do not unduly bias estimates of smoking prevalence.47 Questions were embedded within an omnibus survey, which reduced the likelihood of underreporting of smoking status. A further strength was the frequent monthly measurements of prevalence over a long period using consistent methods, which provided the opportunity to estimate the extent and duration of relatively immediate policy effects. However, time series analysis tends to detect the more immediate and direct effects of interventions and is less able to detect longer-term priming effects or indirect effects of policies or mass media campaigns, such as the extent to which media campaigns can influence the broader social acceptability of smoking and public readiness for the eventual implementation of various tobacco policies. It also fails to provide a test of the combined overall strength of policy action in tobacco control on smoking prevalence. Instead, it seeks to identify the extent to which separate policies contribute independently to a decrease in prevalence.

Governments that have ratified the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control but have yet to make progress towards policy change should recognize that achieving population-wide change in adult smoking prevalence requires significant and sustained commitment to the implementation of tobacco control policies. Our findings suggest that increased tobacco taxation, implementation of comprehensive smoke-free laws and broad reach mass media campaigns provide large and particularly rapid returns on investment. Tobacco tax increases can be used to fund key elements of comprehensive tobacco control programmes48 and the cost of mass media campaigns can be minimized by adapting effective campaigns that have been used in other countries.49,50

Acknowledgements

We thank the Roy Morgan Research Co. for providing access to survey data on monthly smoking prevalence; and Kate Purcell and Vicki White for collating and scoring state tobacco policies.

Funding:

This study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (project grant 396402; Principal Research Fellowship 1003567 to Melanie A Wakefield) and by Cancer Council Victoria.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. The tobacco atlas. 4th ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill D. Why we should tackle adult smoking first. Tob Control. 1999;8:333-5 10.1136/tc.8.3.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/index.html [cited 2014 Feb 19]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman S. Falling prevalence of smoking: how low can we go? Tob Control. 2007;16:145-7 10.1136/tc.2007.021220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman S. Introduction. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, editors. Tobacco in Australia: facts and Issues. 3rd ed. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2008. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/introduction [cited 2014 Feb 28]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2013: enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/index.html [cited 2013 Dec 17].

- 8.Scollo M. Trends in tobacco consumption. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, editors. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. 4th ed. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2012. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-2-consumption [cited 2014 Feb 28]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakefield MA, Durkin S, Spittal MJ, Siahpush M, Scollo M, Simpson JA, et al. Impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on monthly adult smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1443-50 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regional population growth, Australia, 2010–11 [Catalogue no. 3218.0]. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Commonwealth of Australia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczypka G, Emery S, Wakefield MA, Chaloupka FJ. The adaption and use of Nielsen Media Research commercial ratings data to measure potential exposure to televised smoking-related advertisements. Chicago: University of Illinois; 2003. Available from: http://www.impacteen.org/ab_RPNo29_2003.htm [cited 2013 Dec 17].

- 12.Scollo M, Owen T, Boulter J. Price discounting of cigarettes during the National Tobacco Campaign. In: Hassard K, editor. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report volume two. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2000. p. 155-200. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scollo M, Freeman J, Icasiano F, Wakefield M. Early evidence of the impact of recent reforms to tobacco taxes on tobacco prices and tobacco use in Australia. In: Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report volume three. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia; 2004. p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Average weekly earnings, Australia [Catalogue no. 6302.0]. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Commonwealth of Australia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.White VM, Warne CD, Spittal MJ, Durkin S, Purcell K, Wakefield MA. What impact have tobacco control policies, cigarette price and tobacco control programme funding had on Australian adolescents’ smoking? Findings over a 15-year period. Addiction. 2011;106:1493-502 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trade practices (consumer product information standards) (tobacco) regulations 2004 (F2007C00131). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2007. Available from: http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2007C00131 [cited 2013 Dec 17].

- 17.Graphic health warnings on tobacco product packaging. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Commonwealth of Australia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG, Hiller JE. Response of mass media, tobacco industry and smokers to the introduction of graphic cigarette pack warnings in Australia. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:644-9 10.1093/eurpub/ckp089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Box GEP, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC. Time series analysis: forecasting and control. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pankratz A. Forecasting with dynamic regression models. New York: Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burnham K, Anderson D. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Federico B, Mackenbach JP, Eikemo TA, Kunst AE. Impact of the 2005 smoke-free policy in Italy on prevalence, cessation and intensity of smoking in the overall population and by educational group. Addiction. 2012;107:1677-86 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackay DF, Haw S, Pell JP. Impact of Scottish smoke-free legislation on smoking quit attempts and prevalence. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26188 10.1371/journal.pone.0026188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bajoga U, Lewis S, McNeill A, Szatkowski L. Does the introduction of comprehensive smoke-free legislation lead to a decrease in population smoking prevalence? Addiction. 2011;106:1346-54 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JT, Glantz SA, Millett C. Effect of smoke-free legislation on adult smoking behaviour in England in the 18 months following implementation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20933 10.1371/journal.pone.0020933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alamar B, Glantz SA. Effect of increased social unacceptability of cigarette smoking on reduction in cigarette consumption. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1359-63 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siahpush M, Wakefield MA, Spittal MJ, Durkin SJ, Scollo MM. Taxation reduces social disparities in adult smoking prevalence. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:285-91 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME; Working Group, International Agency for Research on Cancer. Effectiveness of tax and rice policies in tobacco control. Tob Control. 2011;20:235-8 10.1136/tc.2010.039982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curbing the epidemic: governments and the economics of tobacco control. Washington: World Bank; 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunlop SM, Cotter TF, Perez DA. Impact of the 2010 tobacco tax increase in Australia on short-term smoking cessation: a continuous tracking survey. Med J Aust. 2011;195:469-72 10.5694/mja11.10074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Australian smokers’ and recent quitters’ responses to the increasing price of cigarettes in the context of a tobacco tax increase. Addiction. 2011;106:1687-95 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durkin S, Brennan E, Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control. 2012;21:127-38 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376:1261-71 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emery S, Kim Y, Choi YK, Szczypka G, Wakefield M, Chaloupka FJ. The effects of smoking-related television advertising on smoking and intentions to quit among adults in the United States: 1999–2007. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:751-7 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, Hammond D, Cummings KM, Yong HHet al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control. 2009;18:358-64 10.1136/tc.2008.028043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, Cameron R, Brown KS. Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control. 2003;12:391-5 10.1136/tc.12.4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, Fong GT, Hammond D, Cummings KMet al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction. 2009;104:669-75 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Partos TR, Borland R, Yong HH, Thrasher J, Hammond D. Cigarette packet warning labels can prevent relapse: findings from the International Tobacco Control 4-Country policy evaluation cohort study. Tob Control. 2013;22e1;e43-50 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327-37 10.1136/tc.2010.037630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wakefield M, Germain D, Durkin S, Hammond D, Goldberg M, Borland R. Do larger pictorial health warnings diminish the need for plain packaging of cigarettes? Addiction. 2012;107:1159-67 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu S-H, Lee M, Zhuang Y-L, Gamst A, Wolfson T. Interventions to increase smoking cessation at the population level: how much progress has been made in the last two decades? Tob Control. 2012;21:110-8 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use (Tobacco control monograph no. 19). Bethesda: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. Available from: http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/Brp/tcrb/monographs/19/index.html [cited 2014 Jan 28].

- 43.Li L, Yong HH, Borland R, Fong GT, Thompson ME, Jiang Yet al. Reported awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China compared to Thailand, Australia and the USA. Tob Control. 2009;18:222-7 10.1136/tc.2008.027037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carter SM. New frontier, new power: the retail environment in Australia’s dark market. Tob Control. 2003;12Suppl 3;iii95-101 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_3.iii95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scollo M, Freeman B. Section 11.10, packaging as promotion. In: Scollo M, Winstanley M, editors. Tobacco in Australia: facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2012. Available from: http://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-11-advertising/11-10-tobacco-display-as-advertising1 [cited 2014 Feb 28]. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Australian Government ComLaw [Internet]. Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011, No. 148. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2014. Available from: http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2011A00148 [cited 2014 Feb 28].

- 47.Biener L, Garrett CA, Gilpin EA, Roman AM, Currivan DB. Consequences of declining survey response rates for smoking prevalence estimates. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:254-7 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO technical manual on tax administration. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakefield M, Bayly M, Durkin S, Cotter T, Mullin S, Warne C; International Anti-Tobacco Advertisement Rating Study Team. Smokers’ responses to television advertisements about the serious harms of tobacco use: pre-testing results from 10 low- to middle-income countries. Tob Control. 2013;22:24-31 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Durkin S, Bayly M, Cotter T, Mullin S, Wakefield M. Potential effectiveness of anti-smoking advertisement types in ten low and middle income countries: Do demographics, smoking characteristics and cultural differences matter? Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:204-13 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]