Abstract

Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa – the countries known as BRICS – represent some of the world’s fastest growing large economies and nearly 40% of the world’s population. Over the last two decades, BRICS have undertaken health-system reforms to make progress towards universal health coverage. This paper discusses three key aspects of these reforms: the role of government in financing health; the underlying motivation behind the reforms; and the value of the lessons learnt for non-BRICS countries. Although national governments have played a prominent role in the reforms, private financing constitutes a major share of health spending in BRICS. There is a reliance on direct expenditures in China and India and a substantial presence of private insurance in Brazil and South Africa. The Brazilian health reforms resulted from a political movement that made health a constitutional right, whereas those in China, India, the Russian Federation and South Africa were an attempt to improve the performance of the public system and reduce inequities in access. The move towards universal health coverage has been slow. In China and India, the reforms have not adequately addressed the issue of out-of-pocket payments. Negotiations between national and subnational entities have often been challenging but Brazil has been able to achieve good coordination between federal and state entities via a constitutional delineation of responsibility. In the Russian Federation, poor coordination has led to the fragmented pooling and inefficient use of resources. In mixed health systems it is essential to harness both public and private sector resources.

Résumé

Le Brésil, la Fédération de Russie, l'Inde, la Chine et l'Afrique du Sud – les pays connus sous le nom de BRICS – représentent quelques-unes des grandes économies ayant connu la croissance la plus rapide dans le monde et près de 40% de la population mondiale. Au cours des 2 dernières décennies, le groupe BRICS a engagé des réformes de son système de santé pour atteindre la couverture de santé universelle. Cet article aborde les 3 aspects clés de ces réformes: le rôle du gouvernement dans le financement de la santé; la motivation profonde derrière ces réformes; et la valeur des leçons tirées pour les pays non-BRICS. Bien que les gouvernements nationaux jouent un rôle majeur dans ces réformes, le financement privé constitue une part importante des dépenses de santé dans le groupe BRICS. Il existe une dépendance à l'égard des dépenses directes en Chine et en Inde et à l'égard d'une présence importante des assurances privées au Brésil et en Afrique du Sud. Les réformes de la santé du Brésil ont fait suite à un mouvement politique qui a fait de la santé un droit constitutionnel, alors que les réformes en Chine, en Inde, en Fédération de Russie et en Afrique du Sud ont représenté des tentatives visant à améliorer la performance du système public et à réduire les inégalités de l'accès aux soins. Les progrès vers la couverture de santé universelle ont été lents. En Chine et en Inde, les réformes n'ont pas abordé suffisamment le problème des paiements restants à charge. Les négociations entre les entités nationales et infranationales ont souvent été difficiles, mais le Brésil a pu parvenir à une coordination adéquate entre les entités fédérales et étatiques grâce à une délimitation constitutionnelle des responsabilités. Dans la Fédération de Russie, le manque de coordination a entraîné un regroupement fragmenté et une utilisation inefficace des ressources. Dans les systèmes de santé à financement mixte, il est essentiel de maîtriser à la fois les ressources des 2 secteurs: public et privé.

Resumen

Brasil, la Federación de Rusia, India, China y Sudáfrica, los países conocidos como BRICS, son algunas de las grandes economías que más rápidamente están creciendo y representan casi el 40% de la población mundial. A lo largo de las últimas dos décadas, los BRICS han emprendido reformas en los sistemas sanitarios para avanzar hacia una cobertura universal de salud. Este artículo analiza tres aspectos clave de estas reformas: el papel del gobierno a la hora de financiar la salud, los motivos subyacentes de las reformas y el valor de las lecciones aprendidas de otros países distintos a los BRICS. Aunque los gobiernos nacionales tienen un papel destacado en las reformas, la financiación privada constituye una parte importante de los gastos sanitarios en estos países. Hay una dependencia de los gastos directos en China e India y una presencia significativa de seguros privados en Brasil y Sudáfrica. Las reformas sanitarias brasileñas tuvieron como resultado un movimiento político que hizo de la salud un derecho constitucional, mientras que las de China, India, la Federación de Rusia y Sudáfrica fueron un intento de mejorar el rendimiento del sistema público y reducir las desigualdades del acceso a este. El avance hacia la cobertura universal de la salud ha sido lento. En China e India, las reformas no han abordado adecuadamente el problema de los pagos directos. A menudo, las negociaciones entre las entidades nacionales y subnacionales han sido difíciles, pero Brasil ha sido capaz de lograr una buena coordinación entre las entidades federales y estatales a través de una descripción constitucional de la responsabilidad. En la Federación de Rusia, una mala coordinación ha tenido como resultado una mancomunación fragmentada y el uso ineficaz de los recursos. En los sistemas sanitarios mixtos, es fundamental emplear recursos tanto del sector público como del privado.

ملخص

تمثل البرازيل والاتحاد الروسي والهند والصين وجنوب أفريقيا - البلدان المعروفة بتجمع "بريك" (BRICS) - بعض الاقتصادات الكبرى الأسرع نمواً في العالم و40 % تقريباً من سكان العالم. وعلى مدار العقدين المنصرمين، قام تجمع "بريك" (BRICS) بإجراء إصلاحات على النظم الصحية للتقدم صوب التغطية الصحية الشاملة. وتناقش هذه الورقة ثلاثة جوانب رئيسية لهذه الإصلاحات، هي: دور الحكومات في تمويل الصحة؛ والدافع الأساسي وراء الإصلاحات؛ وقيمة الدروس المستفادة للبلدان غير المنتمية إلى تجمع "بريك" (BRICS). وعلى الرغم من الدور البارز للحكومات الوطنية في الإصلاحات، يشكل التمويل الخاص حصة كبيرة في الإنفاق الصحي في تجمع "بريك" (BRICS). ويوجد اعتماد على النفقات المباشرة في الصين والهند كما أن هناك تواجداً أساسياً للتأمين الخاص في البرازيل وجنوب أفريقيا. وقد نتجت الإصلاحات الصحية في البرازيل عن حركة سياسية جعلت الصحة حقاً دستورياً، في حين كانت تلك الإصلاحات في الصين والهند والاتحاد الروسي وجنوب أفريقيا محاولة لتحسين أداء النظام العام والحد من التباينات في الإتاحة. وقد اتسم التحرك صوب التغطية الصحية الشاملة بالبطء. ولم تعالج الإصلاحات في الصين والهند مسألة المدفوعات من الجيب الخاص على نحو واف. وكانت المفاوضات بين الكيانات الوطنية ودون الوطنية صعبة في كثير من الأحيان غير أن البرازيل استطاعت تحقيق تنسيق جيد بين الكيانات الفيدرالية والكيانات على صعيد الولايات عن طريق تحديد المسؤولية بموجب الدستور. وفي الاتحاد الروسي، أدى سوء التنسيق إلى التشتت في تجميع الموارد والافتقار إلى الكفاءة في استخدامها. ومن الضروري في النظم الصحية المختلطة أن يتم تسخير موارد القطاعين العام والخاص على حد سواء..

摘要

巴西、俄罗斯联邦、印度、中国和南非被称为金砖五国(BRICS),是全球发展最快的经济体,占将近40%的世界人口。在过去二十年中,金砖国家着手卫生体系改革,迈向全民医疗覆盖。本文讨论了这些改革的三个主要方面:政府在卫生融资方面扮演的角色;改革背后的潜在动机;以及所取得的经验教训对非金砖国家的价值。尽管各国政府在改革中起到重要的作用,但是民间融资构成金砖国家医疗支出的主要份额。中国和印度存在对直接财政支出的依赖,私人保险在巴西和南非大量存在。巴西医疗改革源自一场让医疗成为宪法权利的政治运动,而中国、印度、俄联邦和南非的改革则试图提高公共系统的绩效并减少可达性的不平等。全民医疗覆盖之路推进缓慢。在中国和印度,改革尚未充分解决现金支付的问题。国家和地区实体之间的协商往往具有挑战性,但巴西通过宪法界定责任,已经能够实现联邦和州实体之间良好的协调。在俄联邦,协调性差导致资源的分散统筹和低效利用。在混合卫生体系中,充分利用公共和私营部门的资源至关重要。

Резюме

Бразилия, Российская Федерация, Индия, Китай и Южная Африка — страны, известные как БРИКС, — являются одними из самых быстрорастущих крупных экономик мира и составляют почти 40% населения земного шара. За последние два десятилетия страны БРИКС предприняли реформы систем здравоохранения для улучшения всеобщего медицинского обеспечения. В данной статье обсуждаются три ключевых аспекта этих реформ: роль государства в финансировании здравоохранения, мотивация, лежащая в основе реформ, и ценность извлеченных уроков для стран, не входящих в БРИКС. Хотя национальные правительства играют заметную роль в реформах, частное финансирование продолжает составлять основную долю расходов на здравоохранение в странах БРИКС. Расчет строится на прямых затратах на здравоохранение в Индии и Китае и на значительном присутствии частного страхования в Бразилии и Южной Африке. Бразильские реформы здравоохранения возникли в результате политического движения за охрану здоровья как конституционного права населения, в то время как в Китае, Индии, Российской Федерации и Южной Африке они представляли собой попытку улучшить эффективность государственной системы здравоохранения и уменьшить неравенство в доступе к медицинских услугам. Переход к всеобщему медицинскому обеспечению был медленным. Реформы в Китае и Индии в недостаточной степени решали вопросы оплаты услуг населением. В Бразилии зачастую было затруднительно достичь договоренности между центральными и территориальными субъектами, однако страна смогла добиться хорошей координации между федеральными и местными учреждениями путем конституционного разграничения ответственности. В Российской Федерации плохая координация программ привела к фрагментации и неэффективному использованию ресурсов. В смешанных системах здравоохранения важно использовать ресурсы как государственного, так и частного секторов.

Introduction

Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa – the countries known as BRICS – represent some of the world’s fastest growing large economies and nearly 40% of the world’s population.1 These five nations face several common health challenges: burdens from communicable and noncommunicable diseases, inequitable access to health services, growing health-care costs, substantial private spending on health care, and large private health sectors. Over the last two decades, BRICS have undertaken – or have committed to – substantial health-system reforms that have been designed to improve equity in service use, quality and financial protection, with the ultimate goal of achieving universal health coverage. These health reforms represent an important attempt to translate the growing wealth of BRICS into better health.

BRICS have adopted different paths to universal health coverage and they began travelling along those paths at different points in time. Brazil and the Russian Federation embarked on this process over two decades ago.2–5 China and India are relatively new entrants, having started their reforms in the last decade,6,7 and South Africa has only recently begun the reform process.8 In this paper, we begin by examining the current state of health-care financing in BRICS and then move on to the underlying motivation behind the reforms and the lessons that BRICS’ experience holds for other low- and middle-income countries that are embarking on the path to universal health coverage.

Reforms and health spending

The five countries represented by the BRICS acronym are diverse. They vary in their level of economic development. For example, the per capita gross domestic product of the Russian Federation is approximately sevenfold higher than that of India.1 Although the health reforms of BRICS are also diverse – especially in terms of the health-system issues that they have attempted to correct – they share a central and common aim: the strengthening of the government’s role in health and, particularly, in financing health care.

In Brazil, the Unified Health System – the Sistema Único de Saúde – is a single publicly funded system that covers the whole population and is financed through general taxation. Health services are free at the point of use. By constitutional sanction, each level of government has to earmark a minimum portion of its revenues for health.3

Reforms in the Russian Federation established a system of mandatory health insurance. In this system, payroll taxation is used as a complementary source of funding for a health sector that is predominantly financed through general taxes. Funds from payroll taxes are pooled by subnational insurance schemes and health services are purchased via insurance companies.4,5

The Indian reforms strengthened the government’s role in health by increasing the funding of the public sector – via the National Rural Health Mission, with a focus on primary care – and by establishing government-sponsored insurance for the poor.6 The government insurance schemes cover hospital care at empanelled public and private hospitals for the poor.9

By creating an important role for the government in the health sector, the health reforms in China marked a substantial departure from the old system of health care. One aim was to move away from using patients as a source of financing.7 The reforms focused on strengthening primary care services and increasing insurance coverage.10

South Africa’s National Health Insurance Fund will be funded from taxes and – through active purchasing – should ensure that health services of good quality are available to all citizens.8 The Fund’s purchasing should enable the government to draw on human resources located in both the public and private health sectors.

A predominant reliance on public financing is a necessary condition for the achievement of universal health coverage.11 Health reforms have given BRICS’ governments prominent roles in the health sector, particularly in financing health care. However, private financing of health care – through private voluntary health insurance and out-of-pocket payments – continues to represent a substantial share of health spending. In Brazil, China, India, the Russian Federation and South Africa, private financing accounts for 54%, 44%, 69%, 40% and 52% of total health spending, respectively.1

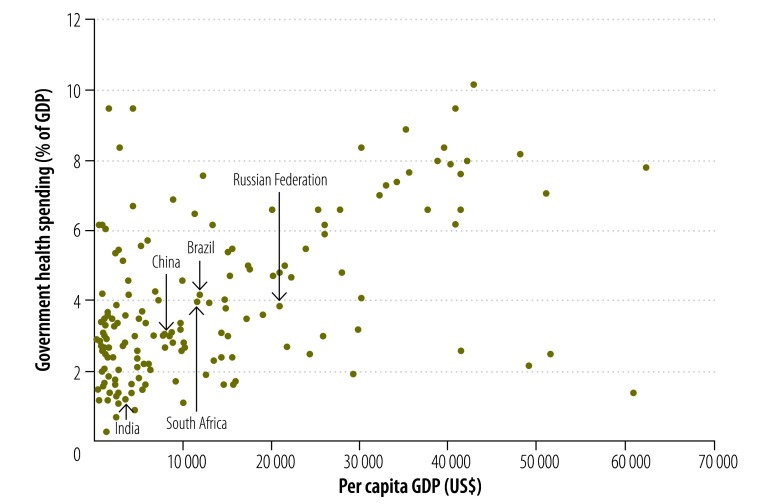

In comparison with other countries with similar income levels, government spending on health as a proportion of gross domestic product is relatively low in China (2.9%), India (1.0%) and the Russian Federation (3.7%), but it is higher in Brazil (4.3%) and South Africa (4.1%) (Fig. 1). The entire population of a country that spends at least 5–6% of its gross domestic product on health often has access to basic health services – because such a country is able to subsidize health care for the poor sufficiently.12 All BRICS countries – particularly China and India – have a distance to go in terms of achieving this spending benchmark (Fig. 1) and ensuring adequate and sustained government financing for the reform process.

Fig. 1.

Government health spending and per capita gross domestic product, in Member States of the World Health Organization, 2011

GDP: gross domestic product; US$: United States dollars.

Source: World Health Organization.1

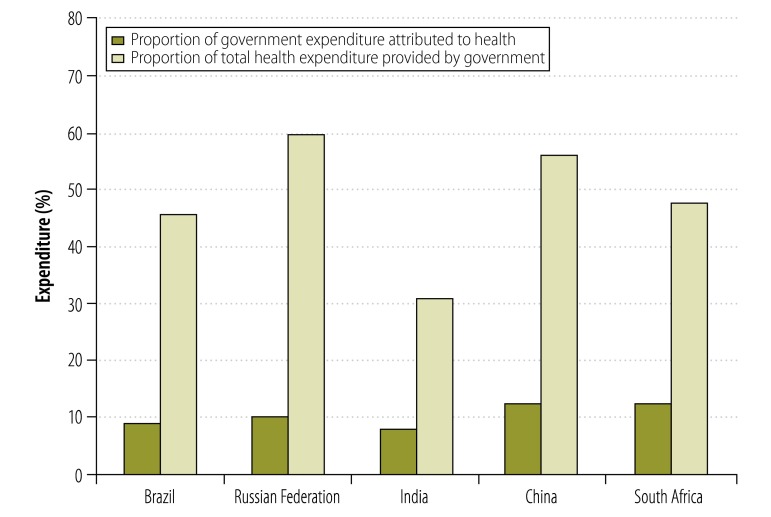

In each BRICS country, health-system reforms have been “flagship programmes” for the national government. However, such prominence has not necessarily translated into health becoming more of a priority for the governments’ policy-makers. As a proportion of total government spending, BRICS still spend markedly less on health, 8.1–12.7% (Fig. 2), than many countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.1 There remains considerable potential for expanding health’s share of the governmental budgets in all five of the BRICS countries.

Fig. 2.

Government health spending, in Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa (BRICS), 2011

Source: World Health Organization.1

In India, out-of-pocket payments still account for a very large share, 59–71% of total health spending.1,13 Most such payments are made to private providers, for outpatient visits.14 The government-sponsored insurance schemes remain focused entirely on hospital care. Despite new investments in public primary care, many outpatients have been kept away from the public sector – and its promise of low cost health care – by inadequate coverage and a common belief that the private sector offers better quality.

In China, out-of-pocket payments still represent 34% of total health spending,1 partly because coinsurance schemes – that cover only a proportion of the costs of health care – are common and partly because many workers in the informal sector have no health insurance.10 The failure of Chinese health reforms to make substantial changes to existing provider-payment methods and the behavioural legacy of the previous 30 years – including the “public-for-profit” mindset of many providers – have not only enabled out-of-pocket payments to persist but also encouraged providers to escalate their charges.15

In Brazil, the levels of out-of-pocket payments for health have fallen under the Unified Health System – to about 31% of total health spending.1 In both Brazil and the Russian Federation, rising affluence and the perceived poor quality of public services – that are often inadequately funded – have contributed to increased demand for private voluntary insurance. In Brazil, for example, private health insurance has grown to cover around 25% of the population.2 In the Russian Federation, voluntary health insurance – which now covers 5% of the population and 3.9% of total health spending – has become six times more common over the last decade.16 Such insurance may be complimentary to mandatory insurance – only covering services provided in private facilities and outpatient medication – or supplementary – with a benefits package that overlaps that of the mandatory insurance and covers various informal payments, including those for inpatient care.16 While the percentage of the South African population covered by private insurance schemes has only increased marginally over the last decade, there have been rapid increases in expenditure within such schemes – driven by spiralling provider fees.

Different origins and perceptions

The health reforms for the promotion of universal health coverage in the five BRICS countries were born of differing motivations and underlying causes. In Brazil in the mid-1980s, almost 30 years of military dictatorship gave birth to a broad-based political movement for re-democratization and improved social rights. Health-sector reform in Brazil was largely driven by civil society rather than by the government, political parties or international organizations.2 Civil society demanded a health system that was responsive to – and controlled by – the public. It also demanded that health be considered a fundamental right. These values were reflected in the constitution adopted in 1988, which paved the way for far-reaching reforms of the health system and formally established the Unified Health System – a system that was based on the principals of universality, integration and social participation.3

There was widespread political upheaval following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. There was universal health coverage in the Soviet health system – all citizens were entitled to health services and complete financial risk protection – but such coverage collapsed with the break-up of the Soviet Union.4,5 The early post-Soviet health reforms of the 1990s introduced mandatory health insurance to strengthen the existing tax-funded health system and provide universal access and comprehensive coverage.4,16,17 Universal health coverage is now guaranteed in the Russian Federation, as a constitutional right. Mandatory health insurance covers almost all outpatient and inpatient services while the government health budget covers emergency, specialized and tertiary care and medication for certain vulnerable groups and conditions.16

Recent health-system reforms in China, India and South Africa were broadly motivated by concerns over the performance of the national health systems, poor health outcomes and persistent and large health inequities. In India’s case, several factors led to the onset of reforms. The existing public sector system – which had been expected to be a vehicle for delivering low-cost health care to all Indians – had failed to deliver on its promise because it was underfunded, undersupplied and understaffed.18 Not surprisingly, out-of-pocket payments to private providers and rising medical costs had placed a large burden on poor households and become an important cause of impoverishment.19,20 In addition, the fall of the incumbent government in the 2004 election signalled – to the new government – the importance of fundamental issues such as health.21 In 2005, such concerns motivated the national government’s efforts to reform health care in the public sector, via the establishment of the National Rural Health Mission.6,21 A National Urban Health Mission has also been introduced.21 In parallel, national and several state governments have been systematically and independently building a government-sponsored health insurance system to cover the costs of secondary and tertiary hospital care for the poor.9 The state-level schemes of health insurance were born as populist measures and were closely associated with the political party that introduced them.9

Although China’s transition from a planned economy to a market economy has created great economic growth, it has also had undesirable effects on the health sector.22 In 2009 China began reforming its health sector in response to public concerns over the high cost of health care, the growing impoverishment experienced by households as a result of health spending, and the large health inequalities observed between provinces and between urban and rural areas.7,23 These problems could be attributed to the way in which health services had been financed. For example, health insurance was far from universal in China. Even by 2002, only about half of the urban population and 90% of the rural population had insurance coverage.7 Although health facilities were publicly owned, the health providers in those facilities had to raise most of their own revenue – and patients were a natural source of revenue. Moreover, collusion between providers and pharmaceutical companies helped to drive up the costs of health care.7 The reforms made in 2009 sought to give the Chinese government a major role in the health sector, inject substantial public funds to increase insurance coverage, reduce fees-for-service and strengthen primary care services.7,23

Concerns over inequity in the health sector are also driving South Africa’s efforts to reform its health system. The burden posed by human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, other communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases and injuries has disproportionately affected South Africa’s lower socioeconomic groups.24,25 Only 17% of the population is covered by private health insurance – leaving the majority of the population reliant on tax-funded health services.26 Since private health insurance accounts for almost half (43%) of total health spending, there is far greater resourcing of services – on a per capita basis – for the minority covered by such insurance than for the majority of South Africans.26 The South African constitution now requires the government to make the necessary resources available to realize the right to health and thereby address these disparities. To fulfil this constitutional obligation, the South African government has committed to introducing a tax-funded National Health Insurance Fund and moving towards universal health coverage.8

Lessons for reforms

The five BRICS countries have followed their own paths on the road to universal health coverage, with varying degrees of success. However, their experiences offer some lessons for other low- and middle-income countries that wish to pursue universal health coverage. It has been the common experience of the BRICS countries that any movement towards such coverage is slow and requires fundamental problems in national health systems to be resolved. Despite more than two decades of reforms, the “early reformers” – Brazil and the Russian Federation – still face fundamental challenges. Brazil, for instance, is yet to achieve complete coverage because it is difficult to attract qualified health workers in remote areas.27 In the Russian Federation, formal and informal out-of-pocket payments still create barriers to accessing care for certain groups of the population – even though the entire population is now covered by mandatory health insurance and the state medical benefit package. Moreover, the poor quality of some care, inequities in access to health care and the levels of prepayment for health remain challenges in BRICS. Any future health reforms need to address the root causes of these challenges. Out-of-pocket payments for health care remain too high and too common in several BRICS countries. In India’s case, payments for outpatient care have been inadequately addressed by health reforms. In China’s case, the reforms have not adequately addressed the provision of adequate salaries for health-care professionals – resulting in a continued reliance on payments from patients.

The five BRICS countries have had varying degrees of success in substantially increasing government spending on health care, even in the presence of high economic growth. While all five countries have enjoyed several decades of high economic growth, they are currently having an economic downturn that may well have a detrimental effect on government health spending. The economies of many other low- and middle-income countries have yet to experience a period of high growth. For these countries, substantial increases in government health spending seem unlikely, at least in the short-term. It is essential that such countries develop a long-term plan to raise more resources for health and use their health resources more efficiently.12 Health resources can be increased not only by giving greater priority to health – in terms of its share of government spending – but also by increasing tax revenues. Importantly, as in the case of Brazil and South Africa, a declared constitutional right to health care can ensure sustained government financing of health reforms. Finally, governance of the health sector often needs strengthening to ensure that mandatory prepayment or public funding becomes the main mechanism for financing health services.12

The administrative systems in many low- and middle-income countries – like those in Brazil, India and the Russian Federation – entail a division of power and responsibility between the central government and subnational entities such as states. Although they are made at the central level, national policies often have to be implemented by subnational entities that are largely autonomous. This often leads to multiple sources of fragmentation and much potential for the duplication of efforts and consequent inefficiencies. Brazil has been fairly successful in managing this problem. Its constitution delineates the basic structure of the Unified Health System in terms of the decentralization of the responsibility for the management of health services to the subnational levels of government. In India – where, constitutionally, health is a state responsibility – central schemes such as the National Rural Health Mission offer funding to states to induce them to follow the national reform’s vision. In China, the central government sets broad policy guidelines but leaves the implementation details to local governments. In China and India, the centre still has little administrative control over implementation and the quality of any implementation can vary considerably across subnational entities. The Russian Federation faces considerable challenges in negotiating its federal and subnational structures. The rapid decentralization of the 1990s created a complex situation in which the Ministry of Health and Social Development, its federal agencies, regional and municipal health authorities and more than a 100 private health -insurance companies share the responsibility for the planning, regulation and implementation of health reforms.4,5,16 There is also fragmented pooling of health funds, between the federal and territorial governments. This makes it difficult to implement any countrywide reforms, leading to geographical variations, inefficiencies and inequity. South Africa also has a quasi-federal system but with the responsibility for health split between national and provincial levels. It seems likely that South Africa will, in the future, adopt a similar approach to health reform as currently seen in Brazil.

The health sector of many low- and middle-income countries is characterized by mixed health systems in which both the public and private sectors provide health services. Where the private sector for health-care delivery is large, universal health coverage will depend critically on the extent to which the resources within the private sector are harnessed. In this situation, such coverage is most likely to be achieved through the strategic purchasing of services from both the public and private providers of health care. Some BRICS countries have attempted this type of purchasing. For example, government-sponsored health insurance in India enables the purchase of hospital services from both public and private hospitals. South Africa’s National Health Insurance Fund also enables the government to draw on human resources located in both the public and private health sectors. Even in countries where the public sector dominates health financing and provision, such as Brazil and the Russian Federation, growing affluence has raised the population’s general expectations of the quality of health care – leading to increased demand for private health insurance. Such changes may lead to a national health system that is split, with the rich seeking care from the private sector while the poor must rely on the public sector.

BRICS represent an unlikely group of countries, which are diverse in so many ways but united by their common experience of high economic growth and an aspiration to improve the health of their citizens. The motivations for recent health reform in each country differ and each country has set out on its own – different – path towards universal health coverage. Notably, all BRICS countries have increased government spending on health and have provided subsidies for the poor.11 However, such improvements will not guarantee universal coverage in the absence of efficiency and accountability.11 For BRICS, the biggest challenge remains the effective translation of new wealth into better health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joseph Kutzin (World Health Organization) and Winnie Yip (University of Oxford) for their valuable comments on the manuscript. KDR has a dual appointment with the Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, United States of America.

Funding:

DM is funded by the South African Research Chairs’ Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Global Health Observatory Data Repository [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main?lang=en [cited 2014 Mar 25].

- 2.Paim J, Travassos C, Almeida C, Bahia L, Macinko J. The Brazilian health system: history, advances, and challenges. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1778-97 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60054-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gragnolati M, Lindelow M, Couttolenc B. Twenty years of health system reform in Brazil: an assessment of the sistema unico de saude. Washington: World Bank; 2013. 10.1596/978-0-8213-9843-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutzin J, Jakab M, Cashin C. Lessons from health financing reform in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Health Econ Policy Law. 2010;5(2):135-47 10.1017/S1744133110000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rechel B, McKee M. Health reform in central and eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1186-95 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61334-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Rural Health Mission: framework for implementation 2005–2012. New Delhi: Government of India; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yip W, Hsiao W. China’s health care reform: a tentative assessment. China Econ Rev. 2009;20(4):613-9 10.1016/j.chieco.2009.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health Act (61/2003). Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- 9.La Forgia G, Nagpal S.Government-sponsored health insurance in India: are you covered? Washington: World Bank; 2012. 10.1596/978-0-8213-9618-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li C, Yu X, Butler JRG, Yiengprugsawan V, Yu M. Moving towards universal health insurance in China: performance, issues and lessons from Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):359-66 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kutzin J. Anything goes on the path to universal health coverage? No. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(11):867-8 10.2471/BLT.12.113654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Accounts 2004–05. New Delhi: Government of India; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahal A, Yazbeck AS, Peters DH. The poor and health service use in India. Washington: World Bank; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yip WC-M, Hsiao W, Meng Q, Chen W, Sun X. Realignment of incentives for health-care providers in China. Lancet. 2010;375(9720):1120-30 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60063-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popovich L, Potapchik E, Shishkin S, Richardson E, Vacroux A, Mathivet B. Russian Federation. Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2011;13(7):1-190, xiii-xiv [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rechel B, Roberts B, Richardson E, Shishkin S, Shkolnikov VM, Leon DA, et al. Health and health systems in the Commonwealth of Independent States. Lancet. 2013;381(9872):1145-55 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62084-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Financing and delivery of health care services in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahrawat R, Rao KD. Insured yet vulnerable: out-of-pocket payments and India’s poor. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(3):213-21 10.1093/heapol/czr029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karan AK, Selvaraj S. Deepening health insecurity in India: evidence from national sample surveys since 1980s. Econ Polit Wkly. 2009;44:55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasgupta R, Qadeer I. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM): a critical overview. Indian J Public Health. 2005;49(3):138-40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip W, Hsiao WC. The Chinese health system at a crossroads. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(2):460-8 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yip WC-M, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu S, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China’s huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833-42 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61880-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ataguba JE, Akazili J, McIntyre D. Socioeconomic-related health inequality in South Africa: evidence from General Household Surveys. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):48 10.1186/1475-9276-10-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P, Sanders D, McIntyre D. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet. 2009;374(9692):817-34 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60951-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIntyre D, Doherty J, Ataguba J. Health care financing and expenditure. In: Van Rensburg H, editor. Health and health care in South Africa. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campos FE, Machado HH, Girardi SN. A fixação de profissionais de saúde em regiões de necessidades. Divulg em Saúde para Debate. 2009;44:13–24 Portuguese. [Google Scholar]