Abstract

Context

The passage of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) and the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) incorporated parity for substance use disorder (SUD) into federal legislation. Yet prior research provides us with scant evidence as to whether federal parity legislation will hold the potential for improving access to SUD treatment.

Objective

This study examined the effect of state-level SUD parity laws on state-aggregate SUD treatment rates from 2000 to 2008, to shed light on the impact of the recent federal-level SUD parity legislation.

Design

A quasi-experimental study design using a two-way (state and year) fixed-effect method

Setting and Participants

All known specialty SUD treatment facilities in the United States

Interventions

State-level SUD parity laws between 2000 and 2008

Main Outcome Measures

State-aggregate SUD treatment rates in: (1) all specialty SUD treatment facilities, and (2) specialty SUD treatment facilities accepting private insurance

Results

The implementation of any SUD parity law increased the treatment rate by 9 percent (p<0.01) in all specialty SUD treatment facilities and by 15 percent (p<0.05) in facilities accepting private insurance. Full parity and parity-if-offered (i.e., parity only if SUD coverage is offered) increased SUD treatment rate by 13 percent (p<0.05) and 8 percent (p<0.05) in all facilities, and by 21 percent (p<0.05) and 10 percent (p<0.05) in those accepting private insurance.

Conclusions

We found a positive effect of the implementation of state SUD parity legislation on access to specialty SUD treatment. Furthermore, the positive association was more pronounced in states with more comprehensive parity laws. Our findings suggest that federal parity legislation holds the potential to improve access to SUD treatment.

An estimated 23 million Americans suffered from a substance use disorder (SUD) in 2010, including abuse or dependence on alcohol and/or illicit drugs.(1) A growing body of literature has demonstrated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of treatment for SUD. Specialty SUD treatment services such as outpatient psychosocial therapy and opioid maintenance therapy (OPT) have proved to be effective in improving health,(2–8) reducing crime,(4–6, 9–11) increasing employment,(8, 9, 12–14) and producing a wide range of social benefits(5, 6, 9, 12–14). Nonetheless, only 17% of those who needed SUD treatment received any treatment for their condition, and 11% (2.6 million) received treatment in a specialty setting.(1)

Financial barriers, in general, and limited insurance coverage for SUD, in particular, pose a major barrier to access to specialty SUD treatment among those perceiving a need for treatment.(1, 15) Ever since the inception of third-party payment for SUD treatment, coverage for SUD treatment has been more restrictive than that for medical/surgical treatment in terms of cost sharing and treatment limitations.(16–18) To address these discriminatory restrictions, more than one-half of states in the U.S. have enacted SUD parity laws during the past two decades requiring employment-related group health plans to provide coverage for SUD treatment equal to that for comparable medical/surgical treatment.(19)

More recently, the passage of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) incorporated SUD parity into federal legislation for the first time.(20) Yet the MHPAEA mandates parity only for employment-related and self-funded group health plans and only for existing SUD coverage offered by those plans (i.e., “parity-if-offered”). Subsequently, provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended SUD parity to Medicaid managed care plans, Medicaid benchmark/benchmark-equivalent plans, and state health insurance exchange plans.(21) Furthermore, the ACA requires that coverage for SUD treatment, as one of the “essential health benefits,” must be offered and must be offered on a par with that for comparable medical/surgical treatment (i.e., “full parity”).

Nonetheless, prior research provides us with scant evidence about the likely impact of federal parity legislation on access to SUD treatment. Two studies examined SUD parity laws in the private insurance market of a particular state (i.e., Vermont and Oregon),(22, 23) and a third study evaluated SUD parity implementation in the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program(24); none of these studies found a significant improvement in access to SUD treatment attributable to the implementation of SUD parity. There are reasons to believe, however, that findings from these studies may have limited generalizability to the anticipated effect of the recent federal SUD parity legislation. Firstly, the study examining Vermont’s 1998 parity law did not include a comparison group to control for the downward secular trend in access to SUD treatment nationwide. Additionally, the study examining Oregon’s 2007 parity law captured only a policy change from partial parity (implemented in 2000) to full parity, and might be confounded by Oregon’s simultaneous reform of methamphetamine regulation (effective in July, 2006) that dramatically curbed the underlying prevalence rate.(25) Finally, the study evaluating FEHB’s parity focused on a study population with a unique risk profile (e.g., less likely to use and abuse/depend on substance) and financial capacity (e.g., less likely to have financial barriers to treatment) that may limit the generalizability of the results to broader privately insured populations.(26)

This study advances the existing literature by analyzing all state-level SUD parity laws in the private insurance market implemented between 2000 and 2008, and applying a rigorous quasi-experimental design to the variations among those state parity laws in the timing of the implementation and the comprehensiveness of the mandate. We hypothesized that: (a) the implementation of SUD parity legislation increased the SUD treatment rate at the state level, (b) the increase in treatment rate was more pronounced in states with more comprehensive SUD parity laws, and (c) the increase in the SUD treatment rate associated with the implementation of SUD parity laws was concentrated in facilities accepting private insurance.

METHODS

Data Sources

The main source of data is the National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) 2000–2008,1 which provides facility-level information on specialty SUD treatment. The N-SSATS facility universe covers all known specialty SUD treatment facilities, allowing for a nearly complete enumeration of specialty SUD treatment services in the United States. Specialty SUD treatment facility, according to N-SSATS, is defined as a hospital, a residential SUD facility, an outpatient SUD treatment facility, a mental health facility with SUD treatment program, or other facility with an SUD treatment program providing the following treatment services: (a) Outpatient, inpatient, or residential/rehabilitation SUD treatment; (b) Detoxification treatment; (c) Opioid treatment programs (OPT) such as methadone and L-α-acetyl-methadol (LAAM) maintenance; and (d) Halfway house services that include SUD treatment. Throughout the study period, response rates ranged from 92 percent to 95 percent.(28)

N-SSATS data were merged with select state-level measures from nationally representative datasets to provide supplementary information on important state socioeconomic characteristics and policy environment (See Table 2 for detailed data sources of study variables).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for states implementing or extending substance use disorder (SUD) parity laws between 2000 and 2008, versus the states with no change in SUD parity status.

| Any Change in Parity | No Change in Parity | Mean- Difference† | Data Sources‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always Parity | No Parity | No Change Total | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Mean (Sd.) | Mean (Sd.) | Mean (Sd.) | Mean (Sd.) | p-value | ||

| # States-Year Observations | 80=10×8 | 128=16×8 | 184=23×8 | 312=39×8 | -- | |

|

| ||||||

| Dependent Variable | ||||||

| % SUD Treatment Rate in All Facilities | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.03 | N-SSATS |

|

% SUD Treatment Rate in Facilities Accepting Private Insurance |

1.3 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.5) | <0.001 | N-SSATS |

|

| ||||||

| % Facilities Accepting Private Insurance | 80.3 (9.5) | 70.8 (7.7) | 64.2 (6.8) | 66.2 (7.2) | <0.001 | N-SSATS |

|

| ||||||

| Covariates | ||||||

| % African/Black | 6.1 (6.2) | 10.4 (9.2) | 11.7 (10.6) | 11.2 (10.0) | <0.001 | CPS |

| % Hispanic/Latino | 4.1 (3.2) | 9.1 (9.8) | 10.5 (10.3) | 9.9 (10.1) | <0.001 | CPS |

| % Poverty | 11.9 (3.0) | 11.9 (3.2) | 12.4 (2.9) | 12.2 (3.0) | 0.43 | CPS-ASEC |

| % SUD Prevalence | 9.6 (1.2) | 9.4 (0.9) | 9.3 (1.1) | 9.3 (1.0) | 0.03 | NSDUH |

| % Medicaid-Eligible | 13.4 (3.7) | 12.6 (3.5) | 12.9 (3.4) | 12.8 (3.4) | 0.12 | CPS-ASEC |

| $ SAPTBG Funding (per capita) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.5 (1.1) | 5.4 (0.8) | 5.4 (0.9) | 0.24 | TIE |

| % Employer-Sponsored Private-Insured | 62.2 (6.0) | 60.7 (6.2) | 59.8 (5.6) | 60.1 (5.8) | 0.005 | CPS-ASEC |

| % Individual-Purchased Private-Insured | 9.5 (2.8) | 10.1 (2.9) | 9.8 (2.9) | 9.9 (2.9) | 0.25 | CPS-ASEC |

| % Workforce in 500+ Employers | 44.6 (6.4) | 48.0 (5.5) | 47.8 (5.5) | 47.9 (5.5) | <0.001 | SUSB |

| % Workforce in 20− Employers | 21.2 (4.3) | 18.7 (2.8) | 19.8 (3.4) | 19.3 (3.2) | <0.001 | SUSB |

|

| ||||||

| # Population (1,000,000) | 3.0 (2.8) | 5.4 (5.2) | 7.2 (7.8) | 6.5 (6.9) | <0.001 | PEP |

Note:

p-value for mean-difference is calculated based on two sample t-test between 10 states with change in parity (Column 1) and 39 states with no change (Column 4);

N-SSATS: National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, SAMHSA; CPS: Current Population Survey, Census Bureau; -ASEC: -Annual Social and Economic Supplement; NSDUH: National Survey of Drug Use and Health, SAMHSA; TIE: Treatment Improvement Exchange, SAMHSA; SUSB: Statistics of United States Businesses, Census Bureau; PEP: Population Estimates Program, Census Bureau.

Analytic Sample

We combined the N-SSATS 2000–2008 datasets, and converted the facility-level data to the state-level, to create an analytic panel of 392 state-year observations across the 49 states and eight years. Virginia was excluded from the analysis because it was the only state that moved away from parity when full parity was repealed and regressed to partial parity in 2004.

Variable Measurement

Dependent Variable

All surveyed facilities were requested to report the total SUD treatment counts in the most recent 12 months prior to the survey. N-SSATS specified that the treatment count should only include the initial entry of a client into treatment; subsequent visits to the same service or transfer to a different service within a single continuous course of treatment were excluded. The missing-item rate for treatment count was approximately 7 percent during the study period.

The treatment counts in all specialty facilities were aggregated to each state s in each year t to determine the state-aggregate annual number of SUD treatment entries. We also aggregate the treatment counts only for facilities that accept private insurance. Both measures of the state-aggregate annual treatment entries are then weighted by the state population size to generate the two dependent variables assessing: (1) treatment rate among all facilities (Treatment Ratest): number of SUD treatment entries into all specialty SUD treatment facilities per 100 state residents in each state s in each year t and (2) treatment rate for facilities accepting private insurance (Treatment Rate-PIst): number of SUD treatment entries into specialty SUD treatment facilities that accept private insurance per 100 state residents in each state s in each year t.

Primary Independent Variables

In a broad sense, SUD parity refers to a policy mandating insurance coverage for SUD treatment to be “no more restrictive” than for comparable medical/surgical treatment, with respect to cost sharing (e.g., deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket expenses), or treatment limitations (e.g., annual or lifetime limits on number of visits or hospital days), or both.(29)

The first independent variable of interest is a dichotomous indicator for the implementation of any parity law in a given state s during a given year t (Parityst). The implementation indicator was assigned a value of 1 for each full year subsequent to the time when a state first implemented its SUD parity law, and a value of 0 for the pre-implementation periods and for states without any SUD parity law.

We also created a categorical measure to distinguish between the following different levels of comprehensiveness in the implementation of parity:

Full parityst: full parity requires SUD coverage to be offered and offered on par with the comparable medical/surgical coverage in all aspects of cost sharing and treatment limitations;

Partial parityst: partial parity, though requiring that SUD coverage to be offered, allows for discrepancies between SUD coverage and comparable medical/surgical coverage in some aspects of cost sharing and treatment limitation;

Parity-if-offeredst: parity-if-offered does not require SUD coverage to be offered, but if offered, it should be on par with the comparable medical/surgical coverage in all aspects of cost sharing and treatment limitations.

To assess the implementation and the comprehensiveness of the state SUD parity laws, we reviewed the relevant information provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)(19), the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), and other advocacy organizations. We also referred to the original state statutes to detect the subtlety in statutory language, and to reconcile the inconsistencies among various sources. Table 1 presents detailed information on state SUD parity laws during the study period.

Table 1.

Summary of the state-level parity laws for substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, 2000–2008

| Parity status between 2000 and 2008 | State (Effective year of parity) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Change | States first implementing or improving parity laws during 2000–2008 | ||||||||

| No Parity → Parity-If-Offered | KY (2001) | WI (2004) | |||||||

| No Parity → Partial Parity | MI (2001) | MT (2002) | NH (2003) | ||||||

| No Parity → Full Parity | DE (2001) | WV (2004) | |||||||

| Partial Parity → Full Parity | RI (2002) | ME (2003) | OR (2007) | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| No Change | States with parity laws existing before 2000 with no further changes (always parity) | ||||||||

| Parity-If-Offered | AR | LA | MN | MO | TN | ||||

| Partial Parity | AK | HI | KS | NV | ND | PA | TX | WA | |

| Full Parity | CT | MD | VT | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| States with no mandate or weak laws (no parity) | |||||||||

| Parity-Like Mandate+ | IN | MA | |||||||

| Weak Mandate† | FL | GA | NC‡ | NY | SC‡ | UT | |||

| Weak† & Alcohol Only | AL | CA | CO | IL | MS | NE | NM | SD | |

| No Mandate | AZ | ID | IA | NJ‡ | OH‡ | OK | WY | ||

Note:

- MA (2001): Full parity for SUD treatment only if co-occurring with a mental illness;

- IN (2003): Parity-if-offered for SUD treatment only if required in the treatment of a mental illness.

Weak mandate (“partial-parity-if-offered”) doesn’t require SUD coverage to be offered, and only requires the offered coverage to be on a par with the comparable medical/surgical coverage in limited aspects of cost sharing or treatment limitations, which is not considered to be parity.

Parity ONLY for state employee plans: OH (1990/1995), NC (1997), NJ (2000), SC (2002).

Covariates

To account for the state-year heterogeneity, we included key time-varying sociodemographic characteristics and policy environment factors that have been extensively documented to influence access to SUD treatment.(15, 30, 31) Our covariates comprised the percentage of state population who are (a) Black/African Americans, (b) Hispanic/Latino Americans, (c) living in poverty (≤ 100% FPL), (d) classified with SUD,2 and (e) eligible for Medicaid. We also included the per capita amount of the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant (SAPTBG) allocated to the state as a proxy for system capacity.3 (32)

In addition to the sociodemographic and policy covariates, we adjusted for the target population and exemption conditions that are commonly included in state SUD parity legislation. Note that most parity laws apply only to employment-related group health plans, leaving the individual (non-employment based) health insurance market unregulated. Moreover, the federal pre-emption by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA 1974) does not allow state legislatures to impose health insurance regulations on self-insured business (usually large-size employers). Some states also exempt small employers with an employee size under 50 or 20, further limiting the reach of SUD parity.(33) Considering the availability of the consistent data across the studies states and years, we controlled for the percentage of the state population (a) covered by employer-sponsored health insurance, (b) covered by individual-purchased health insurance, (c) employed by large employers (i.e., more than 500 employees), and (d) employed by small employers (i.e., less than 20 employees).

Data Analysis

We analyzed the effect of state SUD parity laws on state-aggregate SUD treatment rates, using two-way (state and year) fixed-effect modeling to account for unobserved or unmeasured factors in the treatment rates that are systematically correlated with the parity laws.

The two-way fixed-effect approach can be viewed as an extension of the difference-indifference framework to fit multi-unit and multi-time models that go beyond the traditional two groups (intervention vs. comparison) and two periods (pre and post).(34) By distinguishing the ‘real’ impact of parity legislation from the confounding factors of the state heterogeneity(35) and the national secular trend, we are able to obtain unbiased estimates of the effect of state SUD parity laws.

We estimated four models. The first model estimated the SUD treatment rate among all specialty SUD treatment facilities at state s in year t (Treatment Ratest) as a function of the dichotomous indicator of SUD parity implementation (Parityst), the state fixed effect (υs), the year fixed effect (τt), the state sociodemographic and policy covariates (Covariate Vectorst), and an idiosyncratic error term (εst). A second model was estimated in which the dichotomous indicator of any SUD parity implementation (Parityst) was replaced with the categorical variable of the comprehensiveness in parity mandate (Full Parityst, Partial Parityst, and Parity-If-Offeredst). Note that the dependent variable of the first and the second models, the SUD treatment rate among all specialty SUD treatment facilities (Treatment Ratest), was measured based on the entire population instead of those targeted by state parity. The estimated effect of parity legislation, in this sense, would be diluted over a mixture of target (i.e., those with private insurance plans affected by parity) and non-target groups (i.e., those uninsured, with public insurance, or with private insurance plans not affected by parity). To refine our crude estimates, we also limited the treatment rate measure to facilities accepting private insurance (Treatment Rate-PIst), and re-estimated the two models described above.

All estimated standard errors were clustered at the state level to correct for the serial correlation that otherwise leads to false rejections of the null hypothesis.(36) Analysis was performed using STATA® version 12.0. (STATACorporation, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

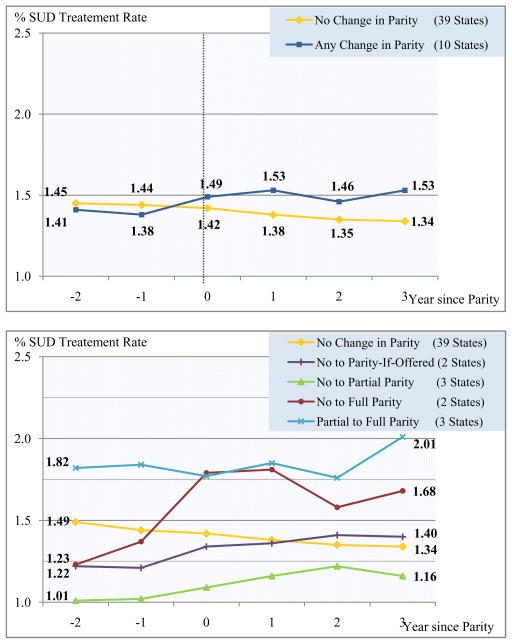

Figure 1 shows an upward trend in the SUD treatment rate in parallel with the implementation of SUD parity legislation. Among the ten states that first implemented SUD parity or extended their parity laws to a higher level of comprehensiveness between 2000 and 2008, the average SUD treatment rate rose from 1.38 percent points (per 100 population) during the year immediately before the parity implementation to 1.53 percent points in the year immediately after implementation. The pre- and post-parity change in the SUD treatment rate was equivalent to an 11 percent increase (i.e., 11% = (1.53–1.38) ÷ [(1.53+1.38) ÷ 2]). Among states that did not change their SUD parity status the average SUD treatment rate fell from 1.44 percent points to 1.38 percent points over the same time period, which corresponds to an decrease of 4 percent (i.e., −4% = (1.38–1.44) ÷ [(1.38+1.44) ÷ 2]). This observational trend-comparison demonstrated a positive association between SUD parity and treatment rate.

Figure 1.

Trend in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment rate by SUD parity status.

Note: Figure 1 presents state-aggregate SUD treatment rate during the pre- and post-parity period. We centered the year each parity state started to implement the law at Time 0. The vertical line represents the year during which each parity state started to implement or extend the law, and it corresponds to the period covered in: N-SSATS 2002 (April, 2001 to March, 2002) for DE and MI, N-SSATS 2003 (April, 2002 to March, 2003) for MT and RI, N-SSATS 2004 (April, 2003 to March, 2004) for ME and NH, N-SSATS 2005 (April, 2004 to March, 2005) for WI and WV, and N-SSATS 2007 (April, 2006 to March, 2007) 2007 for OR. Note that KY implemented parity during the gap year between N-SSATS 2000 and N-SSATS 2002, so Time 0 consisted of nine data points instead of ten. For the other “no change in parity” states, the treatment rates during 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2007 were weighted by 2/9, 2/9, 2/9, 2/9, and 1/9 to match the proportions of the states that implemented parity in a given year. Following the same procedure we determined Time −2, −1, 1, 2, and 3 for parity states, and then transferred “no change in parity” states to the corresponding time in accord with the parity states. Note that only 7 parity states were included for Time −1 (No data for KY, DE and MI), time 2 (No data for OR), and time 3 (No data for OR).

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics for three groups of states: (1) the ten parity states that first implemented parity laws or extended their laws between 2000 and 2008; (2) the 23 states that do not have SUD parity; and (3) the other 16 states that first implement parity laws before 2000 and do not change their laws over the study period. We combined (2) and (3) as the control group representing the states without changes in parity laws during the study period. The two-sample t-tests of mean-differences between the ten parity states with changes in their parity laws and the remaining states without changes indicated that the parity states had a significantly higher rate of SUD treatment in all specialty SUD treatment facilities (p<0.05) and in facilities accepting private insurance (p<0.001).

Table 3 reports the regression results for the estimated effect of SUD parity implementation on the SUD treatment rate. The implementation of any SUD parity law significantly increased the treatment rate in all specialty SUD treatment facilities (Model 1.1: Marginal effect [ME]=0.13 percent point; 95% Confident Interval [CI]: 0.04,0.23), and in facilities accepting private insurance (Model 2.1: ME=0.16 percent point; 95% CI: 0.03,0.30). To place the magnitude of effect into context, we translate the estimated marginal effect (i.e., percentage point change on the basis of per 100 state residents) into the percentage change in SUD treatment rate. Given that the average SUD treatment rate is 1.40 percent point in all specialty SUD treatment facilities, and 1.10 percent point in facilities accepting private insurance, a 0.13 percent point change and a 0.16 percent point change, respectively, can be translated into a 9 percent increase in the overall SUD treatment rate (i.e., 9% = 0.13 ÷ 1.40), and a 15 percent increase in the SUD treatment rate for facilities accepting private insurance (i.e., 15% = 0.16 ÷ 1.10).

Table 3.

Regression results for the estimated effect of substance use disorder (SUD) parity implementation and other covariates on the SUD treatment rate.

| % SUD Treatment Rate | All Facilities | Facilities Accepting Private Insurance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1.1 | Model 1.2 | Model 2.1 | Model 2.2 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| ∂y/∂x (95% CI) | ∂y/∂x (95% CI) | ∂y/∂x (95% CI) | ∂y/∂x (95% CI) | |||||

| Primary Independent Variables | ||||||||

| Parity | 0.13** | (0.04, 0.23) | 0.16* | (0.03, 0.30) | ||||

| Full Parity | 0.18* | (0.03, 0.33) | 0.23* | (0.03, 0.43) | ||||

| Partial Parity | 0.08 | (−0.02, 0.19) | 0.10 | (−0.02, 0.21) | ||||

| Parity-If-Offered | 0.12* | (0.00, 0.23) | 0.11* | (0.00, 0.22) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Covariates | ||||||||

| % African/Black | −0.06 | (−0.16, 0.03) | −0.07 | (−0.16, 0.03) | −0.04 | (−0.15, 0.06) | −0.04 | (−0.15, 0.06) |

| % Hispanic/Latino | −0.10* | (−0.18, −0.02) | −0.10* | (−0.18, −0.02) | −0.07* | (−0.14, −0.00) | −0.07* | (−0.14, 0.00) |

| % Poverty | −0.03 | (−0.08, 0.02) | −0.03 | (−0.09, 0.02) | −0.05* | (−0.09, −0.00) | −0.05* | (−0.09, −0.00) |

| % SUD Prevalence | 0.02 | (−0.05, 0.08) | 0.01 | (−0.05, 0.08) | −0.01 | (−0.07, 0.05) | −0.01 | (−0.07, 0.04) |

| % Medicaid-Eligible | 0.02* | (0.00, 0.04) | 0.02* | (0.00, 0.04) | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.03) |

| $ SAPTBG Funding per capita | −0.13 | (−0.43, 0.17) | −0.13 | (−0.43, 0.17) | −0.10 | (−0.35, 0.15) | −0.10 | (−0.35, 0.15) |

| % Employer-Sponsored Private-Insured | −0.01 | (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.01 | (−0.03, 0.01) | −0.01 | (−0.02, 0.01) | −0.01 | (−0.02, 0.01) |

| % Individual-Purchased Private-Insured | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.03) | −0.001 | (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.001 | (−0.02, 0.02) |

| % Workforce in 500+ Employers | −0.01 | (−0.08, 0.07) | −0.01 | (−0.08, 0.07) | 0.01 | (−0.07, 0.08) | 0.01 | (−0.07, 0.08) |

| % Workforce in 20− Employers | −0.06 | (−0.19, 0.07) | −0.06 | (−0.20, 0.07) | −0.04 | (−0.17, 0.09) | −0.04 | (−0.17, 0.09) |

|

| ||||||||

| R2 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.89 | ||||

Note:

95% CI is calculated based on cluster-adjusted S.E. (state-level clustering).

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

When considering the comprehensiveness of the parity legislation (Table 3), full parity and parity-if-offered increased the SUD treatment rate by 13 percent (Model 1.2: ME=0.18 percent point; 95% CI: 0.03,0.33) and 8 percent (Model 1.2: ME=0.12 percent point; 95% CI: 0.00,0.23) in all facilities, and increased the SUD treatment rate by 21 percent (Model 2.2: ME=0.23 percent point; 95% CI: 0.03,0.43) and 10 percent (Model 2.2: ME=0.11 percent point, 95% CI: 0.00,0.22) in those accepting private insurance. The influence of partial parity on the treatment rate was not statistically significant across models.

COMMENT

Our findings indicate that the implementation of state SUD parity legislation results in a significant improvement in access to specialty SUD treatment. The implementation of any SUD parity law increased the treatment rate by 9 percent in all specialty SUD treatment facilities, and by 15 percent in facilities accepting private insurance. Our study contributes to the existing literature by using state-level panel data on a nearly complete enumeration of all treatment counts in specialty SUD treatment facilities, harnessing all legislative changes in state-level SUD parity laws during the study period, and tailoring a rigorous quasi-experimental design to this series of state experiments.

Our study also advances the literature by documenting the extent to which the comprehensiveness of SUD parity matters. The implementation of full parity laws led to the largest increases in SUD treatment rate (a 13 percent increase), followed by parity-if-offered laws (an 8 percent increase). The effect of partial parity, on the other hand, was not statistically significant.

When considering the implications of our findings for the anticipated impact of recent federal SUD parity legislation, the MHPAEA (i.e., parity-if-offered) can be expected to have a modest effect on access to SUD treatment. It is worth noting that that not only does the MHPAEA regulate quantitative limits (e.g. annual or lifetime limits on number of visits or hospital days) addressed by previous state-level parity laws, but it also mandates parity for a wider range of non-quantitative restrictions such as medical necessity, prior authorization, or utilization review.(23, 37–39) Given the dominance of these managed care mechanisms in private health plans’ SUD service arrangements, the inclusion of the non-quantitative managed care restrictions into the MHPAEA may enable this legislation to yield larger effects on the SUD treatment rate than we estimated for the state-level “parity-if-offered” laws.

Under the ACA, the full parity provision, coupled with insurance expansion, is likely to further improve the access to SUD treatment, beyond the impact of state-level full parity laws. The ACA will expand health insurance to an approximately 50 million uninsured persons; SUD coverage gained by the newly-insured persons through Medicaid benchmark/benchmark-equivalent plans or state health insurance exchange plans will be subject to full parity.(21) In our analysis of the state parity regulations on employment-related group insurance market, the increase associated with full SUD parity were found to be confined within facilities accepting private insurance. By expanding the scope of parity to public insurance programs, the ACA will reach a much larger population and may lead to an unparalleled growth of SUD treatment rate in both the public and private sectors.

The estimated growth in SUD treatment rate will only be possible if the capacity of SUD treatment system suffice to absorb new entrants into the system. Currently the vast majority of SUD treatment is provided in the specialty treatment sector, and researchers have already raised concerns that SUD specialty treatment programs may face challenges in meeting potential needs.(32) The Prevention and Public Health Fund created under the ACA offers grant support to develop more comprehensive SUD screening, brief intervention, referral and treatment programs, which will enhance primary care sites’ capacity to provide SUD care. Enhanced funding for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and the Medicaid “health home” initiatives may also help fill the capacity gap. Nonetheless, as the MHPAEA and the ACA unfold, it will be critical to track the impact of the two laws on SUD treatment to ensure that they are able to fulfill their promise in improving access to SUD treatment.

The conclusions of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, we are not able to identify individuals’ insurance coverage and their employment status in the facility-level N-SSATS data, nor are we able to find more detailed facility-level information on the percentage of treatment entries/clients that were covered by the health insurance plans subject to parity. Thus, the dependent variable, the state-aggregate SUD treatment rate, was measured based on the entire population instead of the population targeted by state parity laws. We refined our analysis by restricting the measurement of treatment rate to facilities accepting private insurance, which yielded a larger point estimate of the parity effect; we also conducted sensitivity analyses for facilities not accepting private insurance (Appendix Tables) and found no difference in SUD treatment rate attributable to parity. Considered together, these additional analyses suggest that the impact of SUD parity on treatment rate is primarily driven by the increased treatment rate among the target population. Second, N-SSATS did not ask facilities to report treatment counts for alcohol and illicit drug separately, thus we were only able to assess the impact of parity on combined SUD treatment rates in spite of their distinct legal status, patterns of treatment, and consequently individuals’ policy sensitivity and price elasticity. Third, as with any observational study, it is not possible to definitively establish causality between the implementation of SUD parity laws and access to SUD treatment. However, the rigorous methods and robust results strongly suggest that parity improved access.

Despite these limitations, our study provides useful insight into the potential effect of the implementation and the comprehensiveness of SUD parity on access to SUD treatment, and in broad terms, the potential of financial incentives and policy leverage to influence treatment-seeking behavior. We found that the implementation of state SUD parity laws significantly increased SUD treatment rate, and that the increase was more pronounced in states implementing more comprehensive laws. These findings suggest that the MHPAEA of 2008 and the ACA of 2010 hold the potential to improve access to SUD treatment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

In 2002, the reference date for the annual survey was changed from September to March in order to enhance the response rate, leaving a gap period from September 2000 to March 2001 with no data collected.

An individual is classified with SUD if he/she meets the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse/dependence and/or illicit drug abuse/dependence.

SAPTBG represents a significant Federal contribution to the states’ substance abuse prevention and treatment system budgets, and accounts for approximately 40 percent of public funds expended by states for SUD treatment. In 2001, sixteen states reported that more than half of their total funding for SUD treatment programs came from the block grant.

Previous Presentation: None

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.United States. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behaviorial Health Statistics and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winklbaur B, Jagsch R, Ebner N, Thau K, Fischer G. Quality of life in patients receiving opioid maintenance therapy. European addiction research. 2008;14(2):99–105. doi: 10.1159/000113724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-Martin I, Ravaux I, et al. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1828–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mojtabai R, Graff Zivin J. Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Four Treatment Modalities for Substance Disorders: A Propensity Score Analysis. Health Services Research. 2003;38(1p1):233–59. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2007;86(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Botsko M, Egan JE, Altice FL, Bazerman LB, et al. Drug Treatment Outcomes Among HIV-Infected Opioid-Dependent Patients Receiving Buprenorphine/Naloxone. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;56:S33. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dismuke CE, French MT, Salomé HJ, Foss MA, Scott CK, Dennis ML. Out of touch or on the money: Do the clinical objectives of addiction treatment coincide with economic evaluation results? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(3):253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sindelar JL, Jofre-Bonet M, French MT, McLellan AT. Cost-effectiveness analysis of addiction treatment: paradoxes of multiple outcomes. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2004;73(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarkin GA, Bray JW, Aldridge A, Mills M, Cisler RA, Couper D, et al. The Impact of Alcohol Treatment on Social Costs of Alcohol Dependence: Results from the COMBINE Study. Medical care. 2010;48(5):396. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d68859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCollister KE, French MT. The relative contribution of outcome domains in the total economic benefit of addiction interventions: a review of first findings. Addiction. 2003;98(12):1647–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard RL, Craddock SG, Anderson J. Overview of 5-year followup outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Studies (DATOS) Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment; Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003 doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parran T, Adelman C, Merkin B, Pagano M, Defranco R, Ionescu R, et al. Long-term outcomes of office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance therapy. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2010;106(1):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French MT, Salome HJ, Sindelar JL, Thomas McLellan A. Benefit-Cost Analysis of Addiction Treatment: Methodological Guidelines and Empirical Application Using the DATCAP and ASI. Health Services Research. 2009;37(2):433–55. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Dilonardo J, Vandivort-Warren R. Type of health insurance and the substance abuse treatment gap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horgan CM, Merrick EL. Financing of substance abuse treatment services. Alcoholism. 2001:229–52. doi: 10.1007/978-0-306-47193-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amaro H. An expensive policy: the impact of inadequate funding for substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(5):657–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sturm R, Sherbourne CD. Are barriers to mental health and substance abuse care still rising? The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2001;28(1):81–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02287236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson GCJ, Whitter M, Magaña C. State Mandates for Treatment for Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busch SH. Implications of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):1–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11101543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity--mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbach ML United States. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration., Center for Mental Health Services (U.S.), Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (U.S.), Mathematica Policy Research inc. Effects of the Vermont mental health and substance abuse parity law. Rockville, Md: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Mental Health Services Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McConnell KJ, Ridgely MS, McCarty D. What Oregon’s parity law can tell us about the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and spending on substance abuse treatment services. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azzone V, Frank RG, Normand SL, Burnam MA. Effect of insurance parity on substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):129–34. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobkin C, Nicosia N. The war on drugs: methamphetamine, public health, and crime. The American economic review. 2009;99(1):324. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.1.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buck JA, Teich JL, Umland B, Stein M. Behavioral health benefits in employer-sponsored health plans, 1997. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18(2):67–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McConnell KJ, Ridgely MS, McCarty D. What Oregon’s parity law can tell us about the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act and spending on substance abuse treatment services. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) 2009. Ann Arbor, Mich: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research distributor; 2010. [United States] Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR28781. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hennessy KD, Goldman HH. Full parity: steps toward treatment equity for mental and addictive disorders. Health Affairs. 2001;20(4):58–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LêCook B, Alegría M. Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: the role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(11):1273–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cummings JR, Wen H, Druss BG. Racial/ethnic differences in treatment for substance use disorders among US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs. 2011;30(8):1402–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchmueller TC, Cooper PF, Jacobson M, Zuvekas SH. Parity for whom? Exemptions and the extent of state mental health parity legislation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(4):w483–7. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.w483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacula RL, Sturm R. State mental health parity laws: cause or consequence of differences in use? Health Affairs. 1999;18(5):182–92. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? National Bureau of Economic Research. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConnell KJ, Gast SHN, Ridgely MS, Wallace N, Jacuzzi N, Rieckmann T, et al. Behavioral health insurance parity: does Oregon’s experience presage the national experience with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):31–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R. Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs. 1998;17(2):40–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma CA, McGuire TG. Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs. 1998;17(2):53–69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.2.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.