Abstract

Background

Shared decision-making has become the standard of care for most medical treatments. However, little is known about physician communication practices in the decision making for unstable critically ill patients with known end-stage disease.

Objective

To describe communication practices of physicians making treatment decisions for unstable critically ill patients with end-stage cancer, using the framework of shared decision-making.

Design

Analysis of audiotaped encounters between physicians and a standardized patient, in a high-fidelity simulation scenario, to identify best practice communication behaviors. The simulation depicted a 78-year-old man with metastatic gastric cancer, life-threatening hypoxia, and stable preferences to avoid intensive care unit (ICU) admission and intubation. Blinded coders assessed the encounters for verbal communication behaviors associated with handling emotions and discussion of end-of-life goals. We calculated a score for skill at handling emotions (0–6) and at discussing end of life goals (0–16).

Subjects

Twenty-seven hospital-based physicians.

Results

Independent variables included physician demographics and communication behaviors. We used treatment decisions (ICU admission and initiation of palliation) as a proxy for accurate identification of patient preferences. Eight physicians admitted the patient to the ICU, and 16 initiated palliation. Physicians varied, but on average demonstrated low skill at handling emotions (mean, 0.7) and moderate skill at discussing end-of-life goals (mean, 7.4). We found that skill at discussing end-of-life goals was associated with initiation of palliation (p = 0.04).

Conclusions

It is possible to analyze the decision making of physicians managing unstable critically ill patients with end-stage cancer using the framework of shared decision-making.

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine identifies patient-centered care as one of the foundations of high-quality health care.1 The emphasis on patient-centered care has made shared decision-making the communication paradigm for most medical treatments, ranging from colorectal cancer screening to end-of-life care.2–4 Successful shared decision making requires three key components: identifying patient preferences, clearly explaining important medical information, and developing consensus around a treatment plan.5 However, a variety of factors complicate shared decision-making regarding the use of intensive care and other life-sustaining treatments near the end of life. Reliance upon surrogate decision-makers can hinder identification of patient preferences.6 Prognostic uncertainty regarding the timing of death makes the applicability of advance directives unclear.7 Finally, provider and organizational incentives to prevent in-hospital death, including public quality measurement and reporting, influence physician responsiveness to patient preferences.8 These factors undoubtedly contribute to the observation that 1 in 5 U.S. citizens die using intensive care (ICU) services,9 despite repeated findings that many Americans report a preference not to die in the hospital.10

Although there have been several recent studies exploring the extent and quality of shared decision making in the context of family meetings in the ICU, typically related to decisions about withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments,11,12 little is known about how physicians make decisions for unstable patients with end-of-life diseases. This decision context (“decision making at a time of crisis near the end of life”13) is unique because it is time pressured and has a significant impact on the manner in which a patient and his/her family experiences death. The purpose of this pilot project is to describe communication practices of hospital-based physicians when making treatment decisions for unstable critically ill patients with end-stage cancer, using the framework of shared decision-making. We hypothesize that physicians demonstrating greater communication skill will more accurately identify patient preferences, and therefore make treatment decisions concordant with those preferences.

Methods

Simulation

We have previously described the details of the simulation case development and content.14 Briefly, using facilities at the University of Pittsburgh Peter M. Winters Institute for Simulation Education and Research (WISER), we combined Sim-Man™ technology vital signs tracings with experienced, trained standardized patients to create a scenario of a 78-year-old man with metastatic gastric cancer, and worsening respiratory distress. Before entering the room, subjects received a chart, including a discharge summary from a recent 2-month hospital stay, a report of a prior computed tomography (CT) scan showing widely metastatic gastric cancer, and a spiral CT negative for pulmonary embolism obtained upon initial presentation. Finally, the chart contained no advanced care plan. However, if probed during the course of the simulation, the patient and his wife would reveal their preference for avoiding readmission to the ICU, intubation, and to receive treatment focused on comfort. We halted the simulation when the physician articulated a plan.

Subjects

We recruited physicians from the Department of Emergency Medicine, the Division of General Internal Medicine, and the Department of Critical Care Medicine at UPMC, using a mixture of in-person presentations at faculty meetings, e-mails to department distribution lists, and calls or visits to physicians' offices. Eligible subjects included physicians with a minimum of 1 month of clinical service per year. Participants did not receive payment for participation.

Measures

Communication behaviors

The framework for our codebook development was shared decision-making. A multidisciplinary team, with expertise in speech communication, palliative care, and critical care, identified best practice behaviors from the pedagogical literature on patient–doctor communication and shared decision making, with particular attention to end-of-life contexts.15–17 We categorized the behaviors into two domains: emotion and discussion of end-of-life goals. We identified six behaviors used to handle emotions: naming an emotion; expressing understanding; showing respect; showing support; exploring the emotion, and articulating an “I wish” statement (a desire of the physician to accomplish something he/she could not control).15 We identified nine cognitive steps involved in discussions about the patient's end-of-life goals: preparing for the discussion; assessing perception; asking for an invitation to disclose information; eliciting and responding to preferences; sharing prognostic information; asking if the patient had questions; checking for agreement with the plan; affirming the patient's decision, and asking if the patient needed familial or spiritual support.16,17 As shown in Table 1, we coded 17 behaviors related to these 9 steps. To reliably identify these communication behaviors, we developed a detailed codebook containing definitions and examples for each of the 23 behaviors. We then iteratively coded each encounter to evaluate the skill of each physician at handling emotion and end-of-life goals.

Table 1.

Definition of Communication Behaviors and Associated Scores

| Domain of communication | Behavior code (Physician action) | Definition | Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors used to handle emotions (possible score 0–6) | 1. Naming emotion | Identifies an emotion | 1 |

| 2. Understanding emotion | Acknowledges understanding of the emotion | 1 | |

| 3. Showing respect | Expresses admiration or respect | 1 | |

| 4. Showing support | Expresses non-abandonment | 1 | |

| 5. Exploring the emotions | Explores the emotional state through nonjudgmental open questions | 1 | |

| 6. Using an ‘I wish’ phrase | Uses an “I wish” phrase in reference to something the physician cannot control | 1 | |

| Behaviors used to discuss of end of life goals (possible score 0–16) | 1. Communicating with the patient directly | Addresses the patient directly | 1 |

| 2. Providing the purpose of the visit | Discusses the purpose of the visit | 1 | |

| 3. Asking what the patient/surrogate know about the cancer | Elicits the patient/surrogate's understanding of the cancer | 1 | |

| 4. Asking what the patient/surrogate know about the recent deterioration | Elicits the patient/surrogate's understanding of the respiratory situation | 1 | |

| 5. Requests the patient/surrogate's permission to proceed | Asks what the patient/surrogate want to know about a given topic | 1 | |

| 6. Eliciting preferences, values, goals | Explores the patient/surrogates' preferences, goals, and values | 1 | |

| 7. Allowing the patient/surrogate time to respond to questions | Qualitative impression | 1 | |

| 8. Responding to stated preferences | Ignores preferences | 0 | |

| Offers different alternative | 0 | ||

| Mirrors, reassures or explores preference | 1 | ||

| 9. Linking treatment recommendations (if made) to stated preferences | Ties the decision directly to patient/surrogate's stated preferences | 1 | |

| 10. Disclosing that death may be imminent without life-sustaining measures | Tells the patient/surrogate that death is imminent if the patient does not get a breathing tube | 1 | |

| *11. Using the term “death” | 1 | ||

| *12. Using only euphemisms for death | 0 | ||

| 13. Asking if the patient/surrogate has questions about plan | Encourages patient/surrogate to ask questions about the plan | 1 | |

| 14. Checking for agreement with the plan | Confirms the decision | 1 | |

| 15. Explicitly telling the patient/surrogate that he/she has made a good decision | Assures the patient/surrogate's that their decision is good. | 1 | |

| 16. Asking if the patient wants family involved in further conversations | Asks if the patient/surrogate would like additional people to join in the decision making | 1 | |

| 17. Asking if the patient wants spiritual support | Asks if the patient/surrogate would like someone spiritual to visit the patient | 1 |

Behaviors only coded if physician disclosed that death may be imminent without life-sustaining measures.

To assess interrater reliability, two coders, blinded to physician attributes other than sex, evaluated a random sample of 20% of the audio files. As shown in Table 2, 5 behaviors used to handle emotions and 15 behaviors used to elicit end-of-life goals had near perfect agreement (κ 0.81–1.0). One emotion-handling behavior and two goals behavior had substantial agreement (κ 0.61–0.80).18,19 Disagreements between coders were resolved through consensus. We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding all behaviors with a κ < 0.8 from our analysis.

Table 2.

Reliability of Coding and Frequency of Occurrence of Each Behavior Code

| Domain of communication | Behavior code | κ | Example of dialogue coded positively | Frequency of occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors used to handle emotions | 1. Naming emotion | 1.0 | “You seem overwhelmed.” | 7 (26%) |

| 2. Understanding emotion | 1.0 | “It's natural to feel this way.” | 5 (19%) | |

| 3. Showing respect | 1.0 | “You've done an amazing job coping.” | 0 (0%) | |

| 4. Showing support | 0.65 | “We will do all we can to help you.” | 4 (15%) | |

| 5. Exploring the emotions | 1.0 | “I have told you a lot. How are you feeling?” | 2 (7%) | |

| 6. Using an “I wish” phrase | 1.0 | “I wish I could tell you something different.” | 1 (4%) | |

| Behaviors used to discuss end-of-life goals | 1. Communicating with the patient directly | 0.88 | “Mr. Jenkins do you understand what I am saying?” | 27 (100%) |

| 2. Providing the purpose of the visit | 0.89 | “The nurse asked me to check on your husband because he's having a hard time breathing.” | 13 (48%) | |

| 3. Asking what the patient/surrogate know about the cancer | 1.0 | “What do you know about your cancer?” | 6 (22%) | |

| 4. Asking what the patient/surrogate know about the recent deterioration | 1.0 | “Tell me what you understand about your breathing.” | 7 (26%) | |

| 5. Asking what the patient/surrogate want to know | 1.0 | “Is now an okay time to talk about your husband's condition?” | 0 (0%) | |

| 6. Eliciting preferences, values, goals | 1.0 | “Have you and your husband discussed what he would want if he got as sick as he was after his last surgery?” | 22 (81%) | |

| 7. Allowing the patient/surrogate time to respond to questions | 1.0 | Qualitative impression | 26 (96%) | |

| 8. Responding to stated preferences | 0.80 | “I know you don't want a breathing tube, but it is the best care we have.” | 1 (4%) | |

| “I'm going to see if there are other ways to make you feel better.” | 4 (15%) | |||

| “I understand you don't want a breathing tube. That seems reasonable.” | 22 (81%) | |||

| 9. Linking treatment recommendations (if made) to stated preferences | 0.64 | “Because you don't want him to be in pain, I would suggest you consider letting us give him morphine.” | 17 (63%) | |

| 10. Disclosing that death may be imminent without life-sustaining measures | 1.0 | “Since we are not going to put you on a breathing machine you may [die]* during this hospitalization.” | 8 (30%) | |

| *11. Using the term “death” | 1.0 | “Die” or “Not survive” | 6 (22%) | |

| *12. Using only euphemisms for death | 0.68 | “Pass away” | 2 (7%) | |

| 13. Asking if the patient/surrogate has questions about plan | 0.89 | “Do you have any questions you would like to ask?” | 19 (70%) | |

| 14. Checking for agreement with the plan | 1.0 | “I understand you don't want CPR. Is that right?” | 7 (26%) | |

| 15. Explicitly telling the patient/surrogate that he/she has made a good decision | 1.0 | “I want you to know you are making a good decision.” | 7 (26%) | |

| 16. Asking if the patient wants family involved in further conversations | 1.0 | “Do you want me to call anyone else in your family?” | 13 (48%) | |

| 17. Asking if the patient wants spiritual support | 1.0 | “Is there a family priest or rabbi you would like to contact?” | 2 (7%) |

CPR, cardiopulononary resuscitation.

Behaviors only coded if physician disclosed that death may be imminent without life-sustaining measures.

Communication skill score

Subjects received one point for each positive communication behavior used during the encounter. We also coded for communication behaviors that did not improve handling of emotion or the elicitation of goals (e.g., only referring to death with euphemisms). However, we did not assign negative points for these statements, using the pedagogical tradition of rewarding positive instead of penalizing negative behavior. Using these principles, we calculated a skill-score for handling emotions (0–6) and discussion of patient goals (0–16), and created a summed score for overall communication skill (0–22; Table 1).

Treatment decisions

In our scenario, the patient had stable end-of-life preferences, which he/the surrogate would disclose when asked. Treatment decisions (ICU admission and initiation of palliation) by the physician, therefore, became our marker for the accurate identification of patient preferences. We defined initiation of palliation as the treatment of dyspnea with narcotics and/or palliative care consultation. Two independent raters observed each simulation in real-time and used a checklist to record physician treatment decisions. Disagreements between raters were resolved through discussion.

Physician characteristics

Subjects provided demographic information, including age, gender, race, year of medical school graduation, specialization (emergency medicine, hospitalist, intensivist), and years at University of Pittsburgh. The variables age, years at the University of Pittsburgh, and year of medical school graduation were collinear. We therefore selected years since graduation, gender, race, and specialization as our predictor variables.

Data analysis

We used nonparametric Spearman, Mann-Whitney, and Kruskal-Wallis tests to study the association between physician covariables and communication behaviors, as appropriate. Next, we used Fisher exact and Mann-Whitney sign rank tests to analyze the association between physician covariables and treatment decisions. Finally, we used Mann-Whitney sign rank test to analyze the relationship between communication behaviors and treatment decisions. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Human subjects

We received Institutional Review Board approval to conceal the study outcome from subjects at the time of recruitment. Instead of revealing that the study focused on communication during end-of-life decision-making, we told subjects that we wanted to study treatment decisions by hospital-based physicians for critically ill patients with whom they did not have a preexisting relationship. At the conclusion of data collection, we provided subjects with full details of the study aims, and offered them the option of withdrawing their participation. None withdrew. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved the protocol; all subjects completed written informed consent.

Results

Subjects

As described previously, among 118 eligible physicians, 31 agreed to participate and 27 completed the simulation. Of the subjects, 13 were hospitalists (48.1%), 8 were intensivists (29.6%), and 6 were emergency physicians (22.2%). Their mean age was 41 years, with an average of 15 years since medical school graduation, and 10 years at the University of Pittsburgh.18

Descriptive summary of communication skill

Physicians demonstrated varying levels of communication skill scores. Skill scores for emotion-handling ranged from 0–3 (possible score 0–6, median 0, mean 0.7, standard deviation [SD] 1); skill scores for discussions about end-of-life goals ranged from 2–13 (possible score 0–16, median 8, mean 7.4, SD 2.8), and overall summed communication scores ranged from 2–13 (possible score 0–22, median 8, mean 8.4, SD 3.0).

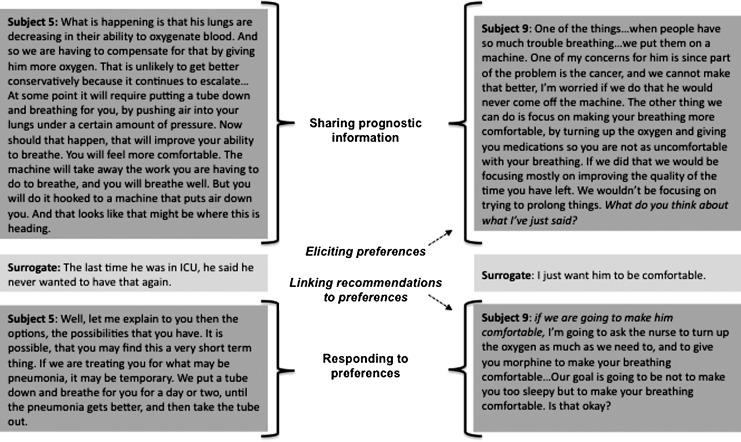

As shown in Table 2, physicians commonly used communication behaviors that would help them to decide how to respond to the patient's worsening dyspnea. Most physicians (81%) tried to elicit the patient's preferences, values, and goals. An example of this occurred when Subject 2 asked, “[Increasing the oxygen] may do the trick, and get you over whatever it is that is going on. It may not. In which case the only thing we have up our sleeve is the breathing tube. Undoubtedly this is something you have had the chance to consider. What are your feelings about that?” Many physicians also asked if the patient or surrogate had questions about the treatment plan (70%) or linked treatment recommendations to the patient's stated preferences (63%) as shown in Figure 1.

FIG. 1.

A comparison of two conversations that resulted in different treatment decisions.

In contrast, they did not commonly use communication behaviors considered best practice for giving bad news or establishing an environment for shared decision making. For example, only 7 (26%) physicians explicitly told the patient and surrogate that they had made a good decision, as Subject 16 did, “I think that given the stage of his cancer, and where things are right now, that is a very appropriate decision.” Similarly, despite the expression of anxiety and/or sorrow by the surrogate in every scenario, physicians rarely responded to the emotional cues she provided. Only 7 (26%) named the surrogate's emotion. Even fewer subjects expressed understanding of that emotion (19%), explored the surrogate's emotion (7%), expressed support (15%), or used an “I wish” phrase (4%).

Also of note, few physicians used negative communication behaviors. Although 8 physicians (30%) used euphemisms, only 2 (7%) did so without ever using the word “die” in the conversation. Additionally, only one physician ignored the patient's stated preferences. In response to the surrogate's statement that her husband did not want a breathing tube, Subject 27 asked, “Even if it is only a temporary measure? I don't know how this will pan out. I understand there is a lot of illness going on here. But this is the best thing I have to offer. I don't want to sit here and not offer you the best care possible.”

Predictors of communication skill

As shown in Table 3, we found that physician characteristics, including years since graduation from medical school, race, gender, and specialty, were not associated with either the handling of emotion or the elicitation of patient goals skill scores. However, on analyzing specific communication behaviors within each domain, we found that the “eliciting and responding to preferences” behavior (ρ −0.4, p = 0.03) and the “affirming the patient's decision” behavior (ρ −0.5, p = 0.01) were negatively associated with years since graduation from medical school.

Table 3.

Relationship between Physician Characteristics and Communication Skill

| Skill score for handling emotions | Skill score for discussions about end-of-life goals | Summed communication score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years since graduation from medical school | p = 0.32 (ρ = 0.20) | p = 0.26 (ρ = −0.22) | p = 0.40 (ρ = −0.17) |

| Race | p = 0.64 | p = 0.75 | p = 0.41 |

| Gender | p = 0.68 | p = 0.29 | p = 0.34 |

| Specialty | p = 0.23 | p = 0.82 | p = 0.99 |

Predictors of treatment decisions

As previously reported, 16 physicians (59%) initiated palliation and 8 (30%) admitted the patient to the ICU. More recently trained physicians were more likely to initiate palliation. Intensivists and emergency physicians (compared to hospitalists) were more likely to admit to the ICU.14 ICU admission did not correlate with initiation of palliation (p = 0.21). As shown in Table 4, in the current analysis, there was no association between the emotion-handling skill score and treatment decisions. However, the elicitation of patient goals skill score predicted palliation (p = 0.04). This association was principally driven a single behavior, “eliciting preferences, values, and goals” (p = 0.05). We confirmed our findings in the sensitivity analysis. In Figure 1, we have compared the conversation of two subjects to show how communication behaviors can influence treatment decisions.

Table 4.

Relationship between Communication Skill and Treatment Decisions

| Initiation of palliation | Transfer to the ICU | |

|---|---|---|

| Skill score for handling emotions | p = 0.41 | p = 0.34 |

| Skill score for discussions about end-of-life goals | p = 0.04 | p = 0.37 |

| Summed communication score | p = 0.15 | p = 0.63 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

In this pilot study of 27 hospital-based physicians from a single academic medical center, we used shared decision making as a framework to analyze their communication practices when faced with a simulated patient with end-stage cancer, dyspnea, and impending respiratory arrest. We made several key observations. First, use of communication best practices among the physicians varied substantially. Second, relatively few physicians responded to the patient and surrogate's emotional cues. Third, physicians who demonstrated more skill at discussing the patient's end-of-life goals were more likely to identify correctly the patient/family goals of treatment and to initiate palliation.

Our study is the first to analyze physician communication and decision making for unstable critically ill patients who are at the end-of-life. We chose shared decision-making as our framework because it has become the paradigm for patient-centered decisions.2 Epstein et al.20 argue that engaging in shared decision-making should help patients/surrogates construct their preferences, by framing knowledge and assisting in their emotional processing. Previous studies of end-of-life communication have focused on conversations between physicians and patients (or their surrogates) that occur either during routine office visits or during family meetings in the ICU.12,21,22 These contexts lack the pressure imposed by time; patients or their surrogates still have the opportunity to seek second opinions, to reflect, and to change their mind. Also, prior studies have typically focused on the relationship between communication behaviors and satisfaction. None have assessed the relationship between physician communication behaviors and actual treatment decisions, which independently impact satisfaction.

However, during a high-fidelity simulation, we find that only one communication behavior (“eliciting preferences”) influences physician treatment decisions in a moment of crisis. Our findings may reflect the artificial nature of the encounter: a simulated environment in which the patient has stable preferences. Moreover, such communication lacks nuance and sophistication. It fails to acknowledge the emotion of the situation, thereby affecting satisfaction,23 and with lasting consequences for the surrogates' recovery from bereavement.24 However, despite these limitations, as long as the physician asks whether the patient wants life-prolonging treatment (eliciting preferences for treatment), s/he is more likely to initiate palliation. We therefore speculate that physicians can provide preference-sensitive care without meeting the standard of shared decision making and communication best practices.

The literature suggests that our observations about physician communication practices in a simulated setting may have generalizability. The majority of physicians withdraw from the emotional reactions of their patients.25–27 Additionally, Wright et al.28 have found that conversations with a physician about end-of-life preferences decrease the intensity of care provided to oncology patients at the end-of-life. Although no information is provided about the particular content (and physician skill) of these discussions, it is tantalizing to hope therefore—in contrast to the main findings of the SUPPORT trial29 and increasing cynicism about the utility of “living wills”10—specific communication behaviors used by physicians can impact end-of-life ICU and life-sustaining treatment use for patients with end-stage cancer.

Interestingly, although skill at end-of-life discussions influences palliation, it does not affect ICU admission. The lack of association may reflect the physicians' belief that the ICU might best meet the patient's goals for care, given system and staffing constraints. Alternatively, it may suggest that physicians discount patient/family preferences to avoid ICU admission, instead believing that the salient preferences to respect are those related to intubation and resuscitation. Finally, we find that more recently trained physicians are more likely to initiate palliation and to demonstrate communication behaviors necessary to handle patient preferences. Perhaps these physicians are more willing to participate in a collaborative rather than directive model of decision making.30 It is uncertain whether the behaviors demonstrated by recently trained physicians' reflect secular trends in medical school and postgraduate curriculum or other cultural cohort effects.

We chose to differentiate between behaviors used to handle emotions and those used to discuss end-of-life goals because skill at handling emotion was unlikely to directly impact treatment decisions.26–27 The emotion-handling behaviors we coded were well described in the literature.31 However, we identified the communication behaviors associated with handling preferences de novo. Based upon the team's clinical experience and the pedagogical literature, we selected behaviors identified in cognitive road maps of tasks, like giving bad news, and those previously described as necessary to discussions about preference sensitive care. Our results may reflect the decision to focus on communication tasks specific to the decision context rather than the overall quality of the interaction. A different framework, such as the Roter Interaction Assessment System (RIAS), which emphasizes the generalized stylistic elements of communication, might produce different findings.32–33

Readers may question the validity of our findings, given that physicians volunteered to participate. Although our findings may not be externally generalizable for this reason, we note that the high prevalence of unskilled communication suggests, if anything, the phenomenon in the “real world” is even more pronounced. Other threats to generalizability include drawing subjects from one academic medical center and our decision to depict a middle-class white couple, who had previously discussed their preferences for treatment together. Additionally, although all subjects endorsed the verisimilitude of the encounter, the patient/family may not be representative of the population with end-stage cancer and acute clinical instability seen by hospital-based physicians.

We focused on verbal communication only, even though nonverbal cues, such as posture or facial expression, may also have promoted patient-centered care. However, given the pilot nature of our study, we decided to begin our development of a framework to analyze physician decisions for unstable critically ill patients with an end-stage cancer by identifying the most necessary components of communication skill. Additionally, we believed this approach would increase the feasibility of applying this coding system to other types of physician–patient interactions, where videotaping would disrupt the encounter.

Finally, for our pilot study, we intentionally designed the scenario to be simple. If the scenario had involved a potentially reversible condition, a patient/family unaware of their long-term prognosis and/or ambivalent about preferences for life-sustaining treatments, then the treatment decisions, and the relationship between the skills and decision making, may have been very different than those we observed in this pilot study.

Conclusions

It is possible to analyze how physicians make decisions for unstable critically ill patients with end-stage cancer using the framework of shared decision making. A high prevalence of eliciting preferences, values, and goals—even in this time-pressured setting—is reassuring, and in the simulated environment materially affects whether the patient receives palliation. Further study is needed to understand the external generalizability of our observations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather E. Hsu, M.P.H., and Courtney Sperlazza, M.P.H., for their research assistance and Doug Landsittel, Ph.D for his statistical consultation.

Supported by University of Pittsburgh Institute to Enhance Palliative Care, Samuel and Emma Winters Foundation, Jewish Healthcare Foundation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson JE. Powers K. Hedayat KM. Tieszen M. Kon AA. Shepard E. Spuhler V. Todres ID. Levy M. Barr J. Ghandi R. Hirsch G. Armstrong D. American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005, Society of Critical Care Medicine: Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine task force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuehn BM. States explore shared decision-making. JAMA. 2009;301:2539–2540. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butow P. Juraskova I. Chang S. Lopez AL. Brown R. Bernhard J. Shared decision making coding systems: how do they compare in the oncology context. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans LR. Boyd EA. Malvar G. Apatira L. Luce JM. Lo B. White DB. Surrogate decision-makers' perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2009;179:48–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-969OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith WR. Poses RM. McClish DK. Huber EC. Clemo FL. Alexander D. Schmitt BP. Prognostic judgments and triage decisions for patients with acute congestive heart failure. Chest. 2002;121:1610–1617. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holloway RG. Quill T. Mortality as a measure of quality: Implications for palliative and end-of-life care. JAMA. 2007;298:802–804. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angus DC. Barnato AE. Linde-Zwirble WT. Weissfeld LA. Watson RS. Rickert T. Rubenfeld GD. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-Of-Life Peer Group: Use of intensive care at the end-of-life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagerlin A. Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White DB. Braddock CH. Bereknyei S. Curtis JR. Towards shared decision-making at the end-of-life in intensive care units. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR. Engelberg RA. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–849. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman DE. Decision-making at a time of crisis. JAMA. 2004;292:1738–1743. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnato AE. Hsu HE. Bryce CL. Lave JR. Emlet LL. Angus DC. Arnold RM. Using simulation to isolate physician variation in intensive care unit admission decision making for critically ill elders with end-stage cancer: A pilot feasibility study. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3156–3163. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f40d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Back AL. Arnold RM. Fryer-Edwards KA. Alexander SC. Barley GE. Gooley TA. Tulsky JA. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White DB. Braddock CH. Bereknyei S. Curtis JR. Towards shared decision-making at the end-of-life in intensive care units. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:461–467. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Gunten CF. Ferris FD. Emanuel LL. Ensuring competency in end-of-life care. JAMA. 2000;284:3051–3057. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis JR. Koch GG. Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGinn T. Wyer PC. Newman TB. Keitz S. Leipzig R. For GG. Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working Group: Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic) CMAJ. 2004;171:1369–1373. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein RM. Peters E. Beyond information: Exploring patients' preferences. JAMA. 2009;302:195–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR. White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaefer KG. Block SD. Physician communication with families in the ICU: Evidence-based strategies for improvement. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:1–9. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fogarty LA. Curbow BA. Wingard JR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lautrette A. Darmon M. Megarbane B. Joly LM. Chevret S. Adrie C. Barnoud D. Bleichner G. Bruel C. Choukroun G. Curtis JR. Fieux F. Galliot R. Garrouste-Orgeas M. Georges H. Goldgran-Toledano D. Jourdain M. Loubert G. Reignier J. Saidi F. Souweine B. Vincent F. Barnes NK. Pochard F. Schlemmer B. Azoulay E. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Back AL. Arnold RM. Discussing prognosis: ‘How much do you want to know?’ Talking to patients who are prepared for explicit information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4209–4213. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollack KI. Arnold RM. Jeffreys AS. Alexander SC. Olsen MK. Abernethy AP. Sugg Skinner C. Rodriguez KL. Tulsky JA. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suchman AL. Markakis K. Beckman HB. Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277:678–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright AA. Zhang B. Ray A. Mack JW. Trice E. Balboni T. Mitchell SL. Jackson VA. Block SD. Maciejewski PK. Prigerson HG. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White DB. Malvar G. Karr J. Lo B. Curtis JR. Expanding the paradigm of the physician's role in surrogate decision making: An empirically-derived framework. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:743–750. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Back AL. Arnold RM. Tulsky JA. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients: Balancing Honesty with Empathy and Hope. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roter DL. Larson S. Fischer GS. Arnold RM. Tulsky JA. Experts practice what they preach. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3477–3485. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roter DL. Larson S. The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS): Utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–251. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]