Abstract

It is commonly recognized that diabetic complications involve increased oxidative stress directly triggered by hyperglycemia. The most important cellular protective systems against such oxidative stress have yet remained unclear. Here we show that the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1), encoded by the Txnrd1 gene, is an essential enzyme for such protection. Individually grown Txnrd1 knockout (Txnrd1−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) underwent massive cell death directly linked to glucose-induced H2O2 production. This death and excessive H2O2 levels could be reverted by reconstituted expression of selenocysteine (Sec)-containing TrxR1, but not by expression of Sec-devoid variants of the enzyme. Our results show that Sec-containing TrxR1 is absolutely required for self-sufficient growth of MEFs under high-glucose conditions, owing to an essential importance of this enzyme for elimination of glucose-derived H2O2. To our knowledge, this is the first time a strict Sec-dependent function of TrxR1 has been identified as being essential for mammalian cells.

Keywords: glucose, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), reactive oxygen species (ROS), selenocysteine, thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated as by-products of cellular metabolism,1 and thus increase in hyperglycemia.2 At physiological concentrations, ROS are regulators of transcription factor activities and serve as secondary messengers in intracellular signal transduction.3 However, excessive quantities of ROS, such as under hyperglycemic conditions, cause oxidative stress and cellular damage.2 Several antioxidant enzyme systems may however serve to protect cells and organisms from the toxic effects of excessive ROS. Among these, the thioredoxin (Trx)- and glutathione (GSH)-dependent systems together with specialized enzymes such as superoxide dismutases and catalase may act in concert.4, 5 Based upon the results of the present study, we suggest that the Trx system is absolutely required for protection against glucose-derived ROS, as shown using immortalized Txnrd1 (gene encoding thioredoxin reductase 1) knockout (Txnrd1−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) as our model system.

Mammalian thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1, encoded in mice by the Txnrd1 gene) is a cytosolic selenoprotein with a selenocysteine (Sec, U) residue in a conserved C-terminal GCUG motif that is essential for its Trx-reducing activity.6 Using reducing equivalents from NADPH, TrxR1 supports a range of Trx-dependent antioxidant enzymes, such as peroxiredoxins (Prxs) and methionine sulfoxide reductases (Msrs). Prxs are important protective enzymes and also components of signaling cascades by modulating H2O2 levels,7 and Msrs repair oxidative damage on methionine residues of proteins.8 TrxR1 may also have other significant antioxidant functions through the reduction of a number of low-molecular-weight compounds as alternative substrates to Trx.9

Deletion of Txnrd1 in mice yields early embryonic lethality.10, 11 Furthermore, conditional TrxR1 depletion in specific tissues of mice or its knockdown in cells can result in massive cerebellar hypoplasia,12 loss of self-sufficient growth under serum starvation,13 or abrogation of tumor formation in a xenograft model.14 However, there are also several observations showing that TrxR1 is not an essential enzyme in all types of cells and tissues,11, 15, 16 likely because of the fact that either chemical inhibition or genetic deletion of TrxR1 typically leads to Nrf2-activated upregulation of complementary GSH-dependent pathways.17, 18 Such findings also showed that TrxR1 is not absolutely required for support of DNA precursor synthesis through ribonuecleotide reductase (RNR), as long as GSH-dependent RNR support is maintained.19 In addition, many organisms have a closely related cysteine (Cys)-dependent non-selenoprotein TrxR, such as D. melanogaster, thereby illustrating that TrxR1 must not necessarily have a Sec residue for biological function.20 Mammalian TrxR1 is furthermore synthesized as a Cys-containing non-selenoprotein under selenium starvation conditions.21, 22, 23 These observations pose the question of whether there are any unique cellular functions of TrxR1 that can explain the lethality of its lack in mouse embryos, and whether there is any necessity of Sec versus Cys in TrxR1 in a cellular context.

Based upon the results of the present study, we conclude that Sec-dependent TrxR1 is absolutely required for protection of individually grown MEFs against glucose-generated H2O2. Interestingly, this protection against hyperglycemia-triggered oxidative stress could neither be sustained by increased levels of GSH and GSH-dependent enzymes in these cells nor by overexpression of a Sec-to-Cys-substituted variant of TrxR1.

Results

Verification of Txnrd1 status in MEF subclones

The MEF cell lines studied here include a parental MEF line that is functionally wild type with regard to TrxR1 status, having exon 15 of the Txnrd1 gene flanked by flox sites (Txnrd1fl/fl), and the full knockout cell line that was clonally derived from Txnrd1fl/fl cells after Cre treatment in vitro (hereafter referred to as Txnrd1−/−), as described previously.16, 24 The latter was used for subsequent transgenic expression of different N-terminally strep-FLAG tagged TrxR1 variants (SF-TrxR1), including overexpression of Sec-containing TrxR1 (Txnrd1498Sec), a Sec-to-Cys-substituted variant (Txnrd1U498C), Sec-to-Ser-substituted enzyme (Txnrd1U498S) and one variant truncated at the position of the Sec residue (Txnrd1498UAA).

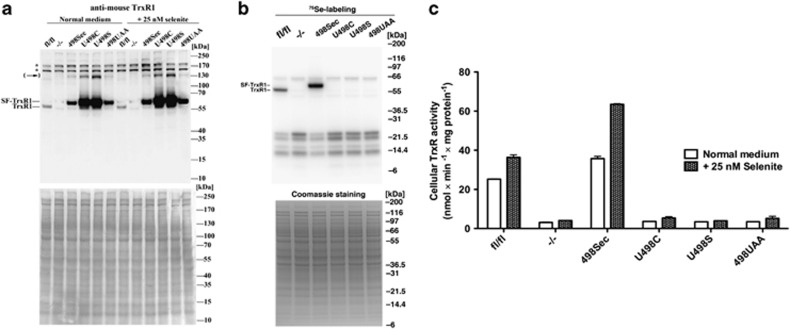

The Txnrd1−/− cells and the expression of reconstituted TrxR1 variants were first confirmed as such by immunoblotting with antibodies against mouse TrxR1. This gave the expected results and furthermore showed that the reconstituted TrxR1 variants were overexpressed with regard to the endogenous TrxR1 level in the parental Txnrd1fl/fl cells (Figure 1a). Autoradiography upon 75Se labeling of all cellular selenoproteins confirmed that Sec incorporation into the TrxR1 variants only occurred in the Txnrd1fl/fl and Txnrd1498Sec MEFs (Figure 1b). Quantification of total TrxR activity in the corresponding cell lysates revealed that only the Txnrd1fl/fl and Txnrd1498Sec MEFs expressed high enzymatic activity that was also responsive to selenium supplementation and ∼1.3- to 1.5-fold higher in the Txnrd1498Sec cell line than in Txnrd1fl/fl (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Characterization of expression levels, Sec incorporation and total cellular enzyme activity of TrxR in MEFs with depleted or reconstituted Txnrd1 variants status. (a) Protein expression levels of TrxR1 incubated with or without 25 nM selenite supplementation in the medium for 24 h were analyzed by immunoblotting using reducing SDS-PAGE (top panel). Unspecific bands are indicated by asterisks (*) and TrxR1 dimeric bands are indicated by an arrow in parentheses. Endogenous (‘TrxR1') and reconstituted (‘SF-TrxR1') variants are indicated between the 55 and 70 kDa weight markers. Ponceau S staining was used as loading control (bottom panel). (b) Sec incorporation was determined using autoradiography of 75Se-labeled selenoproteins. The total proteins of lysed cells were analyzed on a reducing SDS-PAGE gel and exposed to a phosphor screen (top panel). Coomassie staining was used as loading control (bottom panel). (c) Total cellular TrxR activity was determined using a specific Trx-linked insulin disulfide reduction assay, with proteins of the same cell lysates as shown in (a) (n=2)

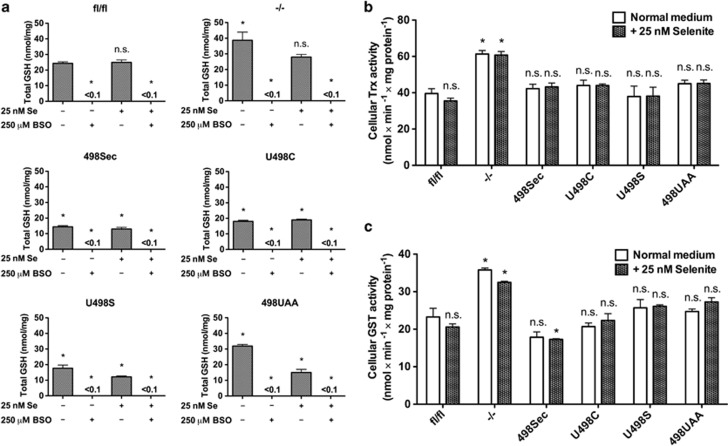

Compensatory upregulation of GSH systems in Txnrd1 knockout cells and their high dependence on GSH for viability

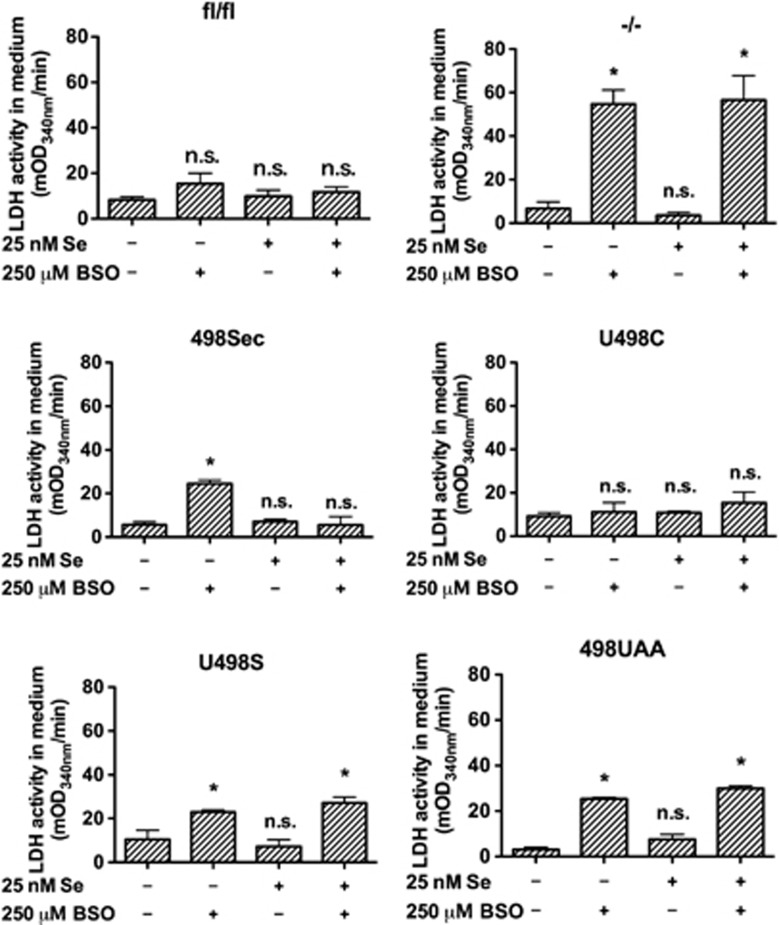

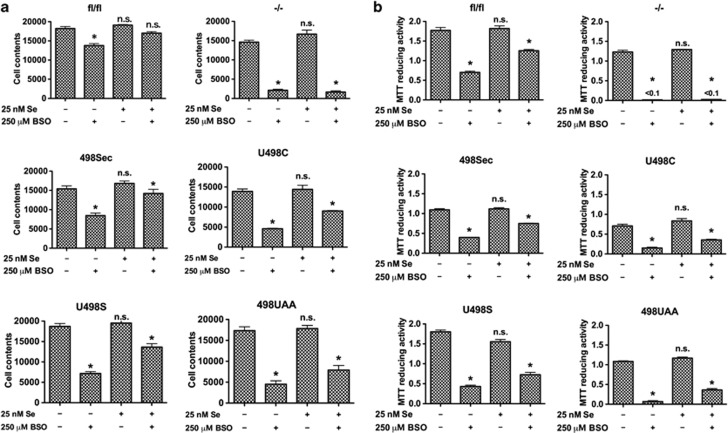

Impairment of TrxR1 typically results in Nrf2 activation and upregulation of GSH-dependent enzymes.10, 16, 25 Here we found that only Txnrd1−/−, but not the other MEF lines, showed a significant elevation of Trx and glutathione transferase (GST) activities as well as total GSH (GSH plus GSSG) content compared with Txnrd1fl/fl cells (Figure 2). In agreement with earlier findings,16, 19, 24 Txnrd1−/− cells were found to be highly sensitive to GSH depletion by L-buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) treatment, as here illustrated by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage to medium, whereas no cytotoxicity with BSO was observed with the parental Txnrd1fl/fl MEFs (Figure 3). Reconstituted expression of Sec-containing TrxR1 expression (Txnrd1498Sec) as well as the Sec-to-Cys mutant (Txnrd1U498C) rescued the cells from BSO-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 3) and restored cell growth (Figure 4). Intriguingly, reconstituted expression of the U498S or 498UAA variants in the knockout cells somewhat reverted the effects of TrxR1 deletion (Figures 3 and 4), without restoration of TrxR activity (Figure 1c), suggesting that expression of these proteins had some protective effects beyond that related to Trx reduction. Self-sufficient growth was, however, impaired in these cells (see next).

Figure 2.

Compensatory changes in Txnrd1−/− and reconstituted TrxR1 variant MEFs. (a) Total GSH contents of the MEF cell lines incubated with or without 250 μM BSO and/or 25 nM selenite for 48 h are shown. (b) Total cellular Trx activities with or without 25 nM selenite supplementation were determined using cell lysates (n=3–4, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between untreated Txnrd1fl/fl without additional selenite and the other samples are indicated (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant, P>0.05). (c) Total cellular GST activities were determined using the same cell lysates in (b) (n=3–4, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between untreated Txnrd1fl/fl without additional selenite and the other samples are indicated (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant, P>0.05)

Figure 3.

Txnrd1 knockout cells are more sensitive to GSH depletion. The extent of cell lysis as indicator of cell death was estimated after 48 h of incubation with or without 25 nM selenite and/or 250 μM BSO, by determining total LDH activity released to the extracellular medium (n=3, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between the untreated cells without addition of selenite and the other samples within each cell line are indicated (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant, P>0.05)

Figure 4.

Growth of Txnrd1-impaired cells is diminished by GSH depletion. (a) Cell proliferation was determined by measuring total contents of cellular nucleic acids after 48 h of incubation, with or without 250 μM BSO and/or 25 nM selenite (n=3, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between the untreated cells without addition of selenite and the other samples within each cell line are indicated (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant, P>0.05). (b) Cell viability was also assessed through reduction of MTT (n=3, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between the untreated cells without addition of selenite and the other samples within each cell line are indicated (*P<0.05; n.s., not significant, P>0.05)

Sec-containing TrxR1 is essential for self-sufficient growth of MEFs

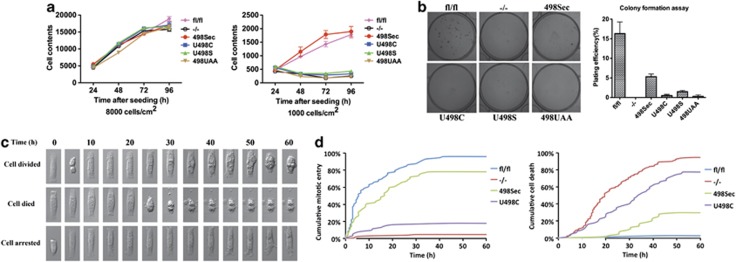

We found that an altered Txnrd1 status had negligible effects on cell growth rates of MEFs when seeded in cultures at a higher density of 8000 cells/cm2. However, when seeded at the lower density of 1000 cells/cm2, only Txnrd1fl/fl and Txnrd1498Sec cells were able to proliferate, whereas the other cells completely failed to grow under such conditions (Figure 5a). These results suggested that self-sufficiency of the cells was affected. Indeed, colony formation assays showed that only Txnrd1fl/fl and Txnrd1498Sec cells survived at appreciable rates, suggesting that Sec-containing TrxR1 is necessary for growth of MEFs as single cells (Figure 5b). We therefore next used time-lapse microscopy to follow individual cells maintained on fibronectin-coated micropatterns, where the cells are devoid of cell–cell contacts but have similar cell–matrix contacts (Figure 5c and Supplementary Movies S1–S4). Almost all Txnrd1fl/fl cells survived and entered mitosis at least once within 60 h after seeding, whereas only a few Txnrd1−/− cells divided once and all of them died within this time frame (Figure 5d). Reconstitution with Sec-containing TrxR1, but not with the Sec-to-Cys mutant, provided significant rescue effects (Figure 5d). These findings suggested that Sec-containing TrxR1 has an essential role for self-sufficient growth of MEFs. Our further studies were therefore next focused on the molecular mechanisms that could explain the survival of Txnrd1−/− cells in high-density cultures.

Figure 5.

Sec-containing TrxR1 is essential for self-sufficient growth of MEFs. (a) Cells were seeded at densities of either 8000 cells/cm2 (left panel) or 1000 cells/cm2 (right panel) and cell proliferation was followed for 96 h by determination of total cellular nucleic acids in the culture wells (n=4, ±S.E.M.). (b) A total of 200 cells were seeded onto six-well plates and incubated for 7 days, whereafter colony formation capacity was assessed. A colony was defined as consisting of at least 20 cells. A representative plate is shown in the left panel, with a graph summarizing total plating efficiency in the right panel. Plating efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the number of colonies to the number of cells seeded (n=3, ±S.E.M.). (c) Single-cell cultures were maintained on fibronectin-coated micropatterns on glass cover slips and followed by time-lapse microscopy for 60 h. Examples of time-lapse montages for cells that proliferated (top), died (middle) or were arrested in growth (bottom) are illustrated. For full movies, see Supplementary Movies S1–S4. (d) The cumulative percentages of single cells that entered mitosis (left panel) or died (right panel) are plotted, as assessed from the single-cell cultures using time-lapse microscopy. Only very few cells displayed growth arrest (1%, 2%, 2% and 13% for Txnrd1fl/fl, Txnrd1−/−, Txnrd1498Sec and Txnrd1U498C, respectively). At least 60 single cells were analyzed for each cell line

Hydrogen peroxide removal rescues Txnrd1 −/− MEFs

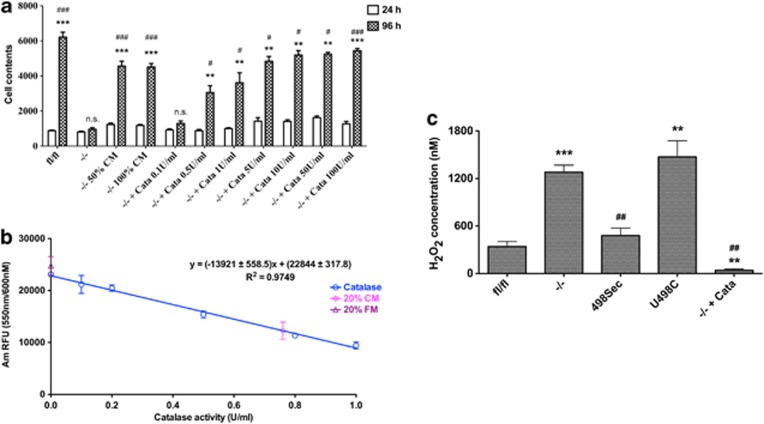

To investigate whether any secreted factor in conditioned medium (CM) of Txnrd1−/− MEFs when cultured at high density (3.2 × 104 cells/cm2, incubated for 24 h) could protect the cells, we collected such medium for use with Txnrd1−/− MEFs seeded at a low density (1000 cells/cm2). Indeed, with either 50 or 100% CM, the Txnrd1−/− MEFs could be rescued (Figure 6a). As catalase has previously been identified as a secreted survival factor for cells,26, 27, 28 we next supplemented fresh medium with pure catalase. As shown in Figure 7a, catalase supplementation to the medium was sufficient to rescue Txnrd1−/− MEFs cultured at low density in a dose-dependent manner. We further assessed whether CM contained catalase activity and showed that 20% CM had 0.76±0.12 units/ml catalase activity, resulting in ∼4 units/ml catalase activity in full CM. Importantly, no catalase-like activity was found in fresh medium (Figure 6b). These findings collectively suggested that removal of H2O2 might be a key feature of the Sec-containing TrxR1 dependency in self-sufficient growth of MEFs.

Figure 6.

Removal of H2O2 rescues Txnrd1−/− MEFs grown in sparse cell cultures. (a) Cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells/cm2 with supplementation of the indicated amounts of conditioned medium (CM) from high-density cultures, or with catalase, and were cultured for either 24 or 96 h as indicated. Cell proliferation was then estimated by determination of total cellular nucleic acids (n=4–9, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between the 96 h of Txnrd1−/− and the other 96 h samples are indicated (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; n.s., not significant, P>0.05), and significant differences between the 24 h and 96 h of each treatment are also indicated (#P<0.05; ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001; n.s., not significant, P>0.05). (b) A standard curve with pure catalase was incubated with 10 μM H2O2 (37 °C, 10 min), and the fluorescence signal indicating the remaining amount of H2O2 was determined using Amplex Red. The equation of the standard curve with R2 value is also shown. The corresponding catalase activities of 20% fresh medium (FM) or conditioned medium (CM) are also plotted onto the curve, as shown. According to this titration, 20% CM contained 0.76±0.12 units/ml catalase activity and 20% FM had no catalase activity (n=3–9, ±S.E.M.). (c) A total of 1.5 × 104 Txnrd1−/− cells, with or without supplementation with catalase (100 units/ml), or Txnrd1fl/fl, Txnrd1498Sec and Txnrd1U498C cells as indicated were seeded onto 96-well microtiter plates in HBSS buffer for 18 h, whereupon extracellular H2O2 was measured using Amplex Red (n=4–8, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences are indicated (*compared with Txnrd1fl/fl MEFs, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; #compared with Txnrd1−/− MEFs, ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001)

Figure 7.

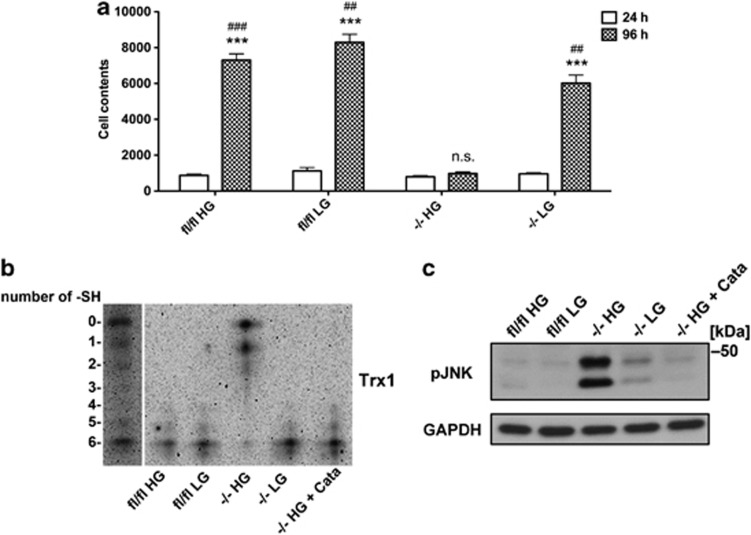

Low-glucose medium prevents cell death, Trx1 oxidation and JNK phosphorylation with Txnrd1−/− MEFs grown in sparse cell cultures. (a) Cells were seeded at a low density of 1000 cells/cm2 in either high-glucose (25 mM glucose, HG) or low-glucose (5.5 mM, LG) medium, whereupon they were cultured for either 24 or 96 h. Cell proliferation was then estimated by determination of total cellular nucleic acids (n=6–9, ±S.E.M.). Significant differences between the 96 h of Txnrd1−/− and the other 96 h samples are indicated (**P<0.01; ***P<0.001), and significant differences between the 24 and 96 h of each treatment are also indicated (#P<0.05; ##P<0.01; ###P<0.001; n.s., not significant, P>0.05). (b) Txnrd1fl/fl or Txnrd1−/− MEFs, with or without supplementation with catalase (100 units/ml), were cultured at 1000 cells/cm2 for 20 h in either HG (25 mM) or LG (5.5 mM) medium. The redox state of Trx1 was then analyzed by redox immunoblotting.30 The migration of Trx1 in a standard curve of MEF protein lysate treated so that Trx1 variants in all forms from 0 to 6 free Cys thiol groups being present30 is shown in the first lane. (c) The same set up as in (b) was used but phosphorylated JNK was determined by immunoblotting, using GAPDH as loading control

We subsequently analyzed extracellular H2O2 levels in media of 200 μl cell culture volumes upon 18 h of incubation. With this setup, we found that 1.5 × 104 Txnrd1fl/fl MEFs had generated an extracellular concentration of 340±64 nM H2O2. Notably, the medium from Txnrd1−/− MEFs displayed an extracellular level of 1280±89 nM H2O2 that thus was increased fourfold compared with the parental MEFs. However, the levels were reverted by either reconstituted expression of Sec-containing TrxR1 (480±94 nM H2O2) or by addition of catalase (41±16 nM H2O2), but not by reconstitution of the Cys variant of the enzyme (1473±204 nM H2O2, Figure 6c), thereby correlating well with the protective effects of Sec-containing TrxR1 reconstitution or catalase supplementation (Figures 5d and 6a). These observations strongly supported the notion of an essential role of Sec-containing TrxR1 in cellular H2O2 elimination that could be compensated for by the presence of extracellular catalase activity.

High glucose triggers oxidative stress-induced cell death of Txnrd1 −/− MEFs grown in sparse cell cultures

All experiments above were performed in conventional MEF cell culture DMEM medium containing 4.5 g/l glucose (25 mM).29 To investigate whether the high glucose in this medium induced the oxidative stress-triggered cell death in Txnrd1−/− MEFs, we next analyzed growth of the cells cultured at low density in DMEM medium using a lower glucose content (1 g/l glucose, 5.5 mM). Indeed, in sharp contrast to what was observed in the high-glucose medium, Txnrd1−/− MEFs survived and proliferated in low-glucose medium (Figure 7a). As Txnrd1 is depleted in Txnrd1−/− cells and the redox status of its main substrate Trx1 is a marker of oxidative stress in the cytosol, we used a recently developed redox immunoblotting method30 to detect the number of free thiols in Trx1 of the MEFs cultured at low density in either high- or low-glucose medium. This revealed that only in Txnrd1−/− MEFs cultured in high glucose, Trx1 was found mostly in its oxidized state, whereas this Trx1 oxidation was totally reversed by either growth in low glucose or by extracellular supplementation with catalase (Figure 7b). In parallel, we also determined the JNK phosphorylation state as a well-characterized marker for oxidative stress-related cell death.31 Indeed, a strong phosphorylation of JNK was observed in the Txnrd1−/− MEFs grown in high-glucose medium, but not in the parental Txnrd1fl/fl cells, in low-glucose cultures or upon catalase supplementation (Figure 7c).

Taken together, these findings demonstrated that the cell death observed in Txnrd1−/− MEFs when grown at low density was induced by high glucose, high H2O2 and involved Trx1 oxidation and increased JNK phosphorylation. All these events could be totally prevented by either lowering the glucose content of the medium or by the presence of extracellular catalase activity, although neither of these events were seen upon growth in high glucose if the cells expressed Sec-containing TrxR1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study identifying a defined molecular function of Sec-containing TrxR1 that is essential for mammalian cells. With this function being protection against glucose-derived H2O2, several reflections can be made regarding the roles of selenium and parallel antioxidant systems in cells.

The massive cell death observed in Txnrd1-depleted MEFs when grown in sparse cell cultures, which could only be rescued by reconstituted expression of Sec-containing TrxR1, but not by expression of Sec-devoid variants of the enzyme including its Sec-to-Cys mutant, suggests that the GSH-dependent systems (upregulated in these cells) are not always redundant with the TrxR1-dependent antioxidant enzyme systems. Based upon our findings, it seems clear that the essential role of TrxR1 in these cells was indeed support of antioxidant protection, and not other roles such as support of DNA replication through RNR. The observation that extensive cell death was also prevented by CM from high-density cultures further supports that notion. In this case, catalase seemed to be an autocrine survival factor, and this is similar to previous findings with lymphocytes.26, 27, 28 An earlier study also found catalase secretion in MEF cultures.32 The findings also demonstrate that high H2O2 levels produced during oxidative stress may rapidly equilibrate between the intra- and extracellular space, which probably occurs through aquaporin-3,33 and explains how catalase present in the growth medium can protect cells from intracellularly produced H2O2.

It is worth noting that we found no evidence for increased Trx1 oxidation in the Txnrd1−/− cells grown in low glucose or in high glucose upon addition of catalase. This shows that some additional cellular pathway, apart from TrxR1, can keep Trx1 in its reduced form. Recently, it was indeed shown that GSH and Grx1 can constitute such a backup system34 that may be further facilitated in Txnrd1−/− cells because of their compensatory upregulation of GSH-dependent enzyme systems. Importantly, such alternative Trx1 reduction was evidently not sufficient in the Txnrd1−/− MEFs for survival under increased oxidative stress as triggered by high glucose. It is here likely that TrxR1 is required, together with Trx, for sufficient support of Prxs to eliminate H2O2,35 but additional TrxR1-dependent antioxidant functions can also not be disregarded. It is important to note that Sec-containing TrxR1, but not the Sec-to-Cys version formed under selenium deficiency,21, 22, 23 could abolish the excessive amount of H2O2 release from Txnrd1−/− cells and save them at low density in high glucose. This is indeed, to our knowledge, the first identification of a distinct molecular pathway where Sec-containing TrxR1 provides a unique and essential function in mammalian cells.

High glucose-induced production of ROS occurs mainly through two pathways:36 One is glucose oxidation in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle that yields superoxide and H2O2 through the mitochondrial electron transport chain;36 the other is the activation of protein kinase-C (PKC) that in turn activates NADPH oxidases.36, 37 Further studies are required to determine whether mainly one or both of these pathways are predominant sources of H2O2 in the Txnrd1−/− cells.

The severe Trx1 oxidation and robust activation of JNK phosphorylation in the Txnrd1−/− MEFs, with protection by catalase, support the notion that cell death can be directly triggered by H2O2, resulting in Trx1 oxidation, with subsequent activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), JNK phosphorylation and finally cell death.31, 38 Recent results employing the same MEF cell lines as used in this study showed that Txnrd1 depletion gave increased oxidation of PTP1B (protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B),39 that may also trigger signaling pathways with JNK phosphorylation. In addition to a direct signaling of apoptosis, necrosis can also contribute to oxidative stress-triggered cell death, because extensive ROS levels promote the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) that can cause mitochondrial depolarization, ATP depletion and necrosis.40

Our findings may also explain why attempts to establish MEF cultures from homozygous Txnrd1 knockout embryos at E8.5 invariably failed,11 whereas they could be established in vitro through treatment of Txnrd1fl/fl MEFs with Tat-Cre recombinant protein.16 We thus speculate that cultured Txnrd1fl/fl MEFs were able to reach a high density before depletion was performed, thereby yielding enough autocrine catalase activity to protect knockout cells from cell death. In contrast, isolation of Txnrd1−/− MEFs directly from embryos results in low-density cultures that fail to survive. It is here worth emphasizing that clonal derivation of Txnrd1−/− cells after Tat-Cre treatment was done in pyruvate-containing medium under low (5%) oxygen concentration11, 15, 16, 24 that may also yield lower oxidative stress because of direct scavenging of H2O2 by pyruvate,41 and less H2O2 formation in hypoxia.

In conclusion, here we found that elevated GSH-dependent enzyme systems were not sufficient to prevent oxidative stress-triggered cell death, and thus support of self-sufficient growth of Txnrd1−/− MEFs, when grown in high-glucose MEF culture conditions. Sec-containing TrxR1, but not its Sec-to-Cys variant, was here exclusively required for cell survival and growth because of its critical role for H2O2 elimination.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Recombinant human wild-type Trx1 was generously provided by Arne Holmgren (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden). Recombinant rat TrxR1 (28.5 units/mg) was produced as described previously.42 Rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse TrxR1 antibody serum was a kind gift from Dr. Gary Merrill (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA). All other chemicals or reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless stated otherwise.

Isolation of mouse Txnrd1−/− embryonic fibroblasts and reconstitution with variant forms of TrxR1

The establishment of Txnrd1−/− MEFs has been described elsewhere.16, 24 In brief, cells with two loxP-flanked Txnrd1 alleles were isolated from conditional Txnrd1 knockout embryos,11 immortalized by cultivating them for at least 20 passages at low (5%) oxygen in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g/l glucose content (25 mM glucose), 1 mM pyruvate and supplemented with 1% glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (yielding∼15–20 nM selenium in final; PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany).43 Tat-Cre fusion protein was applied to achieve Txnrd1 depletion. Briefly, 5000/cm2 cells were incubated with 1 μg Tat-Cre protein for 16 h in CD CHO medium (Invitrogen), and then the medium was exchanged for the DMEM medium mentioned above. After 24 h, the cells were washed, trypsinized and plated in limited dilution in 96-well plate. Cells were maintained at low (5%) oxygen with regular change of medium every third day. Outgrown clones were expanded and screened for deletion of Txnrd1 by PCR and western blot,24 thus generating Txnrd1−/− cell lines. To reconstitute TrxR1 expression in Txnrd1−/− MEFs, a lentivirus-based approach was used to stably express murine wild-type TrxR1 and various mutants derived thereof in principle as described for glutathione peroxidase 4.44 Various mutant forms of TrxR1 were generated by site-directed mutagenesis against the Sec (Sec498) that was mutated to cysteine (Txnrd1U498C), serine (Txnrd1U498S) or truncated (Txnrd1498UAA), respectively, using the following sets of primers (mutated base pairs are in bold letter): Txnrd1_U498C_for: 5′-CTCCAGTCTGGCTGCTGCGGTTAAGCCCCAGT-3′, Txnrd1_U498C_rev: 5′-ACTGGGGCTTAACCGCAGCAGCCAGACTGGAG-3′, Txnrd1_U498S_for: 5′-CTCCAGTCTGGCTGCTCCGGTTAAGCCCCAGT-3′, Txnrd1_U498S_rev: 5′-ACTGGGGCTTAACCGGAGCAGCCAGACTGGAG-3′, Txnrd1_498UAA_for: 5′-TCCAGTCTGGCTGCTAAGGTTAAGC-3′, Txnrd1_498UAA_rev: 5′-GCTTAACCTTAGCAGCCAGACTGGA-3′. The reconstituted TrxR1 was furnished at the N-terminus with a tandem affinity purification enhanced tag (TAPe-tag) consisting of FLAG-2xStrep, and expressed with the natural Txnrd1-derived selenocysteine insertion sequence (SECIS) element in the 3′ UTR. Txnrd1 knockout cells were transduced with lentiviruses encoding either wild-type or various mutants. 5 × 104 cells were transduced with 10–15 μl of virus supernatant. At 36 h post transduction, transduced cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of puromycin for stable expression in batch cultures.

Cell cultures

The established MEF variants were, unless indicated, cultured in DMEM with 4.5 g/l glucose content (25 mM glucose), no pyruvate and supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (BioWhittaker, Lonza, NJ, USA) and 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (yielding ∼15–20 nM selenium in final; PAA Laboratories). DMEM with neither glucose nor pyruvate (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 g/l glucose (5.5 mM) and the other reagents listed above was used for the low-glucose cultures. Cells were grown in humidified air containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C for all experiments.

Preparation of cell lysates

All cell lines were seeded with or without 25 nM selenite supplementation 24 h before they were harvested and lysed in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 0.5% Triton-X). The clarified supernatants after centrifugation (13 300 r.p.m., 15 min) were used to analyze either enzymatic activities or immunoblots. Total protein concentrations were determined with a Bradford reagent kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunoblot detection of TrxR1 isoforms

Total proteins were separated on a reducing SDS-PAGE gel and Ponceau S staining was used as loading control. A rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse TrxR1 primary antibody serum was used with the SuperSignal West Pico kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the signals were detected utilizing a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS scanner and the Quantity One 4.6.7 software.

Enzyme activity assays

Cellular TrxR and Trx activities were determined using the previously described end-point insulin reduction assay.45 Cellular GST activity was determined based on enzyme-dependent conjugation of reduced glutathione with CDNB according to Habig et al.,46 as modified for a 96-well plate. Briefly, the assay consists of 2 mM GSH and 0.5 mM CDNB in phosphate buffer, and then the cell lysates were added and the reactions were monitored at 340 nm. Controls without proteins were treated as background.

75Se-radioisotope labeling

Cells were seeded and incubated with 75Se-labeled selenite (Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA) in a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml for 48 h before they were collected and lysed. The clarified supernatants were fractionated on a reducing SDS-PAGE (Buffers, gel and equipment from Invitrogen). The gel was stained with Coomassie Blue to visualize total protein. After drying, it was then exposed on a phosphor screen and autoradiography was visualized with a Typhoon FLA 7000 (GE Healthcare Lifesciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Cell viability assays

For analyses of viable cells, they were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) at 37 °C for 4 h and thereupon dissolved in DMSO. Absorbance was measured at 550 nm, with cell-free samples as background.

Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays

Cells were seeded for the indicated time points onto 96-well microtiter plates and subsequently treated as described. Cell proliferation was estimated based upon determination of total cellular nucleic acids, using the CyQUANT Cell Proliferation Assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. LDH efflux assays were used to assess cytotoxicity and were performed as described previously.23

Quantification of total intracellular GSH and GSSG

Total intracellular GSH and GSSG concentrations were determined by the previously described glutathione reductase-DTNB recycling assay.45

Colony formation assays

Cells was seeded into six-well plates, with subsequent growth for 7 days. On the day of analysis, colonies were fixed and stained with 6% glutaraldehyde containing 0.5% crystal violet, and then counted using an optical microscope. A colony was defined as consisting of at least 20 cells.

Micropattern-based single-cell cultures and time-lapse imaging

In order to record single-cell growth, cells were plated on fibronectin-coated 80 × 15 μm micropatterns on glass cover slips custom-produced by Cytoo (Grenoble, France). At 30 min after seeding, cover slips were washed to remove unattached cells, whereupon the slips were kept in a humidified atmosphere with the same high-glucose DMEM as in the other experiments covering the cells. Cells were imaged using differential interference contrast (DIC) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 on a Leica (Solms, Germany) DMI6000 imaging system, using a 20 × NA 0.4 objective. Images were acquired every 30 min for 60 h. The cumulative percentage of single cells that entered mitosis or died were plotted against incubation time, as described in the main text.

Hydrogen peroxide assays

Levels of H2O2 were measured using Amplex Red as described previously.47 Briefly, 1.5 × 104 cells were seeded into 96-well plates in 200 μl of HBSS (Hank's Balanced Salt Solution, 1 g/l glucose) containing 20 μM Amplex Red and 0.1 U/ml HRP, and were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. Thereafter, fluorescence readings were recorded with excitation and emission wavelengths of 550 and 600 nm, respectively. Different concentrations of H2O2 (0–5 μM) were used to generate a standard curve.

Catalase activity assays

Indicated amounts of catalase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; catalog no. C1345) or medium samples were incubated with 10 μM H2O2 at 37 °C for 10 min in HBSS in total volumes of 100 μl in 96-well microtiter plates. For subsequent analyses of H2O2 levels, 100 μl HBSS buffer containing 40 μM Amplex Red and 0.2 U/ml HRPs was added to each well in 96-well microtiter plates and fluorescence readings were recorded immediately with excitation and emission wavelengths of 550 and 600 nm, respectively.

Redox immunoblotting of Trx1

Redox immunoblotting of Trx1 was performed as described elsewhere.30

Immunoblot detection of phosphorylated JNK

Immunoblot detection of the phosphorylated JNK was performed as described elsewhere.48

Statistics

Values are presented as means±S.E.M. Statistical evaluation was performed with the Mann–Whitney test using the GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Asterisks or pounds signs denote statistically significant differences between the indicated groups of data (* or #P<0.05; ** or ##P<0.01; *** or ###P<0.001).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding to ESJA from the Swedish Cancer Society (Grant Numbers 2009/739 and 2012/341), the Swedish Research Council (Grant Numbers 2008-2654 and 2011-2631), Karolinska Institutet and a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant (CO 291/2-3) to MC.

Glossary

- Sec

selenocysteine

- TrxR1

thioredoxin reductase 1

- Txnrd1

gene encodes thioredoxin reductase 1

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Trx

thioredoxin

- GSH

glutathione

- Prx

peroxiredoxins

- Msr

methionine sulfoxide reductases

- RNR

ribonuecleotide reductase

- Cys

cysteine

- GST

glutathione transferase

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- BSO

L-buthionine sulfoximine

- CM

conditioned medium

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- PKC

protein kinase-C

- ASK1

signal-regulating kinase 1

- PTP1B

protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B

- MPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- CDNB

dinitrochlorobenzene

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by G Raschellà

Supplementary Material

References

- Ray PD, Huang BW, Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2012;24:981–990. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414:813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:7–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels C, Raes M, Toussaint O, Remacle J. Importance of Se-glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and Cu/Zn-SOD for cell survival against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg J, Arnér ES. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1287–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Holmgren A. Essential role of selenium in the catalytic activities of mammalian thioredoxin reductase revealed by characterization of recombinant enzymes with selenocysteine mutations. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18121–18128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: a historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Methionine sulfoxide reductases: selenoprotein forms and roles in antioxidant protein repair in mammals. Biochem J. 2007;407:321–329. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner ES. Focus on mammalian thioredoxin reductases—important selenoproteins with versatile functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:495–526. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondareva AA, Capecchi MR, Iverson SV, Li Y, Lopez NI, Lucas O, et al. Effects of thioredoxin reductase-1 deletion on embryogenesis and transcriptome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:911–923. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupoglu C, Przemeck GK, Schneider M, Moreno SG, Mayr N, Hatzopoulos AK, et al. Cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase is essential for embryogenesis but dispensable for cardiac development. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1980–1988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1980-1988.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soerensen J, Jakupoglu C, Beck H, Forster H, Schmidt J, Schmahl W, et al. The role of thioredoxin reductases in brain development. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Patterson AD, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Targeting thioredoxin reductase 1 reduction in cancer cells inhibits self-sufficient growth and DNA replication. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1112. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Thioredoxin reductase 1 deficiency reverses tumor phenotype and tumorigenicity of lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13005–13008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins MF, van der Heide DM, Weisend CM, Kundert JA, Comstock KM, Suvorova ES, et al. Hepatocytes lacking thioredoxin reductase 1 have normal replicative potential during development and regeneration. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2402–2412. doi: 10.1242/jcs.068106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal PK, Schneider M, Kolle P, Kuhlencordt P, Forster H, Beck H, et al. Loss of thioredoxin reductase 1 renders tumors highly susceptible to pharmacologic glutathione deprivation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9505–9514. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvorova ES, Lucas O, Weisend CM, Rollins MF, Merrill GF, Capecchi MR, et al. Cytoprotective Nrf2 pathway is induced in chronically txnrd 1-deficient hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locy ML, Rogers LK, Prigge JR, Schmidt EE, Arner ES, Tipple TE. Thioredoxin reductase inhibition elicits Nrf2-mediated responses in Clara cells: implications for oxidant-induced lung injury. Antioxid Redox Sign. 2012;17:1407–1416. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigge JR, Eriksson S, Iverson SV, Meade TA, Capecchi MR, Arner ES, et al. Hepatocyte DNA replication in growing liver requires either glutathione or a single allele of txnrd1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromer S, Johansson L, Bauer H, Arscott LD, Rauch S, Ballou DP, et al. Active sites of thioredoxin reductases: why selenoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12618–12623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134510100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Zhong L, Lonn ME, Burk RF, Hill KE, Holmgren A. Penultimate selenocysteine residue replaced by cysteine in thioredoxin reductase from selenium-deficient rat liver. FASEB J. 2009;23:2394–2402. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XM, Turanov AA, Carlson BA, Yoo MH, Everley RA, Nandakumar R, et al. Targeted insertion of cysteine by decoding UGA codons with mammalian selenocysteine machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:21430–21434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009947107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Xu J, Arner ES. Thiophosphate and selenite conversely modulate cell death induced by glutathione depletion or cisplatin: effects related to activity and Sec contents of thioredoxin reductase. Biochem J. 2012;447:167–174. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal PK, Seiler A, Perisic T, Kolle P, Banjac Canak A, Forster H, et al. System x(c)- and thioredoxin reductase 1 cooperatively rescue glutathione deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22244–22253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson AD, Carlson BA, Li F, Bonzo JA, Yoo MH, Krausz KW, et al. Disruption of thioredoxin reductase 1 protects mice from acute acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity through enhanced NRF2 activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:1088–1096. doi: 10.1021/tx4001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom PA, Buttke TM. Autocrine production of extracellular catalase prevents apoptosis of the human CEM T-cell line in serum-free medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4708–4712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran EC, Kamiguti AS, Cawley JC, Pettitt AR. Cytoprotective antioxidant activity of serum albumin and autocrine catalase in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:316–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Wang Y, Lo AS, Gomes EM, Junghans RP. Cell density plays a critical role in ex vivo expansion of T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:386545. doi: 10.1155/2010/386545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from fibroblast cultures. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:3081–3089. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zheng Y, Fried LE, Du Y, Montano SJ, Sohn A, et al. Disruption of the mitochondrial thioredoxin system as a cell death mechanism of cationic triphenylmethanes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Liu ZG. JNK signaling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:928–939. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prowse AB, McQuade LR, Bryant KJ, Marcal H, Gray PP. Identification of potential pluripotency determinants for human embryonic stem cells following proteomic analysis of human and mouse fibroblast conditioned media. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:3796–3807. doi: 10.1021/pr0702262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EW, Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Aquaporin-3 mediates hydrogen peroxide uptake to regulate downstream intracellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15681–15686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005776107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Zhang H, Lu J, Holmgren A. Glutathione and glutaredoxin act as a backup of human thioredoxin reductase 1 to reduce thioredoxin 1 preventing cell death by aurothioglucose. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38210–38219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC. The biological chemistry of hydrogen peroxide. Methods Enzymol. 2013;528:3–25. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405881-1.00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A, Xia L, Goldberg H, Lee KW, Quaggin SE, Fantus IG. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates high glucose-induced reactive oxygen species generation by mitochondria and the NADPH Oxidase, Nox4, in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6835–6848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, et al. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagnell M, Frijhoff J, Pader I, Augsten M, Boivin B, Xu J, et al. Selective activation of oxidized PTP1B by the thioredoxin system modulates PDGF-beta receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13398–13403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302891110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, He L, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition: a common pathway to necrosis and apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:463–470. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giandomenico AR, Cerniglia GE, Biaglow JE, Stevens CW, Koch CJ. The importance of sodium pyruvate in assessing damage produced by hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:426–434. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Arner ES. Pyrroloquinoline quinone modulates the kinetic parameters of the mammalian selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1 and is an inhibitor of glutathione reductase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:815–820. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello S, Samper E, Krtolica A, Goldstein J, Melov S, Campisi J. Oxygen sensitivity severely limits the replicative lifespan of murine fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:741–747. doi: 10.1038/ncb1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannes AM, Seiler A, Bosello V, Maiorino M, Conrad M. Cysteine mutant of mammalian GPx4 rescues cell death induced by disruption of the wild-type selenoenzyme. FASEB J. 2011;25:2135–2144. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-177147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson SE, Prast-Nielsen S, Flaberg E, Szekely L, Arner ES. High levels of thioredoxin reductase 1 modulate drug-specific cytotoxic efficacy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1661–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habig WH, Pabst MJ, Fleischner G, Gatmaitan Z, Arias IM, Jakoby WB. The identity of glutathione S-transferase B with ligandin, a major binding protein of liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3879–3882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, et al. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J. 2007;406:105–114. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panieri E, Gogvadze V, Norberg E, Venkatesh R, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Reactive oxygen species generated in different compartments induce cell death, survival, or senescence. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;57:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.