Abstract

β-Lapachone activates multiple cell death mechanisms including apoptosis, autophagy and necrotic cell death in cancer cells. In this study, we investigated β-lapachone-induced cell death and the underlying mechanisms in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells. β-Lapachone markedly induced cell death without caspase activation. β-Lapachone increased PI uptake and HMGB-1 release to extracellular space, which are markers of necrotic cell death. Necrostatin-1 (a RIP1 kinase inhibitor) markedly inhibited β-lapachone-induced cell death and HMGB-1 release. In addition, β-lapachone activated poly (ADP-ribosyl) polymerase-1(PARP-1) and promoted AIF release, and DPQ (a PARP-1 specific inhibitor) or AIF siRNA blocked β-lapachone-induced cell death. Furthermore, necrostatin-1 blocked PARP-1 activation and cytosolic AIF translocation. We also found that β-lapachone-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production has an important role in the activation of the RIP1-PARP1-AIF pathway. Finally, β-lapachone-induced cell death was inhibited by dicoumarol (a NQO-1 inhibitor), and NQO1 expression was correlated with sensitivity to β-lapachone. Taken together, our results demonstrate that β-lapachone induces programmed necrosis through the NQO1-dependent ROS-mediated RIP1-PARP1-AIF pathway.

Keywords: β-Lapachone, NQO1, ROS, RIP1, PARP1, AIF

β-Lapachone is a natural compound that is obtained from bark of the lapacho tree, and it has been reported to be a natural product that activates apoptotic cell death in several cancer cell lines, including prostate cancer, breast cancer, and leukemia.1, 2, 3 β-Lapachone is also considered to be a good sensitizer of radiotherapy in colon and prostate cancer cells.4, 5 The cancer cell-specific death-inducing effects of β-lapachone are known to be directly correlated with the enzymatic activity of NAD(P)H: quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1).6, 7 NQO1 normally reduces quinones to stable hydro-quinones and is then excreted when it is conjugated with glucuronide or sulfate. However, NQO1 metabolizes β-lapachone to a highly reactive unstable hydroquinone, and this unstable hydroquinone is then oxidized back to semiquinone or quinone. Semiquinones, free radical generators, initiate the redox cycle, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are then generated.7, 8, 9 β-Lapachone is an ortho naphthoquinone that has the ability to induce the formation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide.10 NQO1 is highly expressed in most human solid tumors, including tumors from the colon, breast, pancreas, liver and lung.8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Therefore, β-lapachone may selectively kill cancer cells that target NQO1.

Recently, programmed necrosis is found in cancer cell death by anticancer agents.16, 17 When caspase is inactivated, receptor interacting protein-1 (RIP1) is phosphorylated by TNF-α, and it then interacts with RIP3 via RIP homotypic interaction motif domains, leading to programmed necrosis, referred as necroptosis.18 This necroptosis is defined as RIP1/RIP3-dependent cell death, and it is inhibited by an RIP1 kinase inhibitor, a necrostatin-1.19, 20, 21 In addition to RIP1/RIP3, AIF has also been known to be a mediator of necroptosis. Under stress conditions, the DNA repair enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) results in the massive synthesis of poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), and, in consequence, intracellular NAD+ and ATP are rapidly depleted. Subsequently, AIF translocates from the mitochondria to the cytosol and nucleus, and AIF binds with DNA and RNA to induce caspase-independent chromatinolysis in the nucleus.22, 23, 24 The DNA damaging drug, N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG)-induced necroptosis, requires PARP-1 hyperactivation and RIP1 activation.25, 26 However, the relationship between RIP1 and PARP-1-AIF remains to be further investigated.

In this study, we investigated the mechanism of β-lapachone-induced cell death, and we identified the importance of the interaction between RIP1 and PARP1-AIF signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells.

Results

β-Lapachone induces caspase-independent cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells

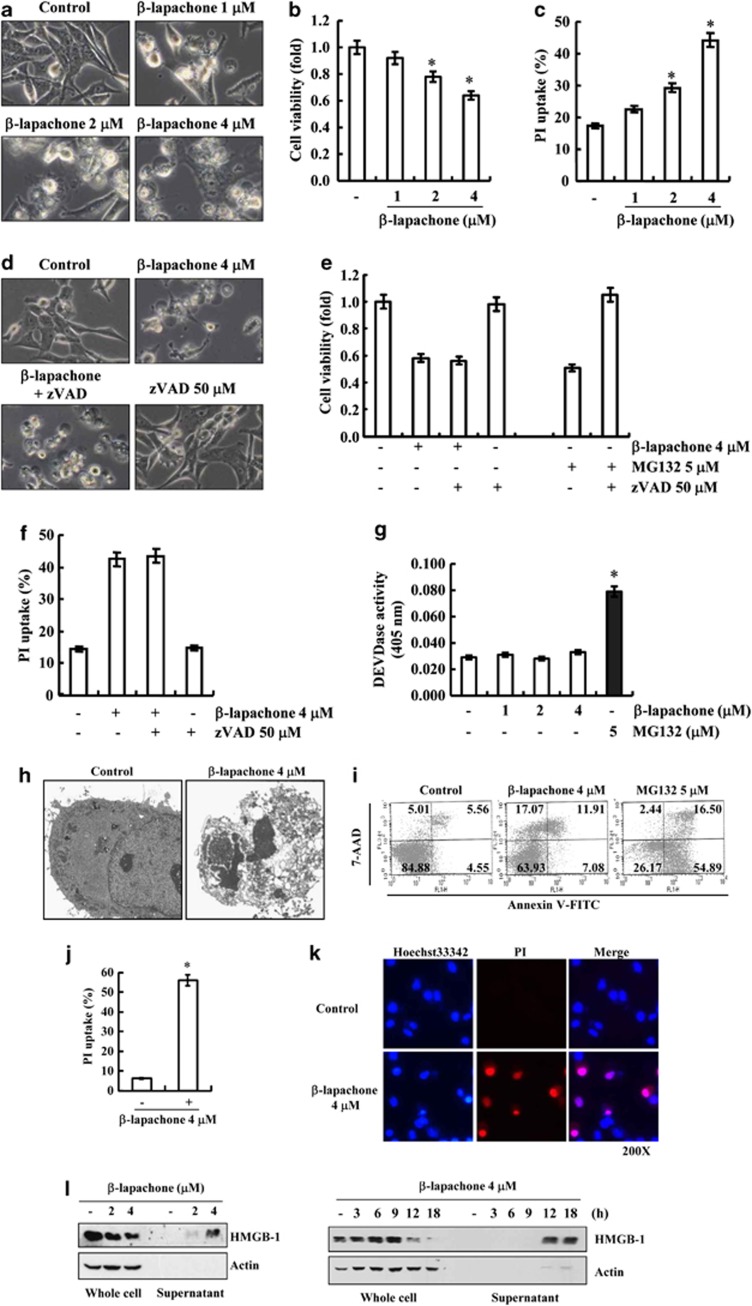

To investigate the effects of β-lapachone on cell death of human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells, light microscope analysis, XTT assay and PI uptake were used. As shown in Figure 1a, β-lapachone increased the morphological appearance of dying cells in a dose-dependent manner, and cell viability was decreased in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figure 1b). Furthermore, β-lapachone also increased PI uptake (loss of plasma membrane integrity) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1c). Next, we investigated whether caspase activation was involved in β-lapachone-induced cell death. The proteasomal inhibitor (MG132) induced apoptosis in several cancer cell lines.27 The pan-caspase inhibitor (zVAD-fmk) inhibited MG132-induced cell death. However, zVAD-fmk had no effect on β-lapachone-induced morphological changes, reduction of cell viability and induction of PI uptake (Figures 1d–f). To confirm caspase-independent cell death by β-lapachone, we assessed DEVDase (caspase-3) activity. β-Lapachone did not increase caspase-3 activity, whereas MG132 markedly induced activation of caspase-3 (Figure 1g). These data suggest that β-lapachone-induced cell death is independent of caspase activation in SK-Hep1 cells.

Figure 1.

β-Lapachone induces necrotic cell death in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells. (a–c) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h. The cell morphologies were determined by interference light microscopy. Images were magnified × 200 (a). Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (b). Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI), and PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry (c). (d–f) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone or 5 μM MG132 for 18 h in the presence or absence of zVAD-fmk (50 μM) for 18 h. The cell morphologies were determined by interference light microscopy. Images were magnified × 200 (d). Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (e). Cells were stained with propidium iodide, and PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry (f). (g) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone or 5 μM MG132 for 18 h. Caspase activities were determined with colorimetric assays using caspase-3 DEVDase assay kits. (h) Transmission electron microscopic observation was conducted on SK-Hep1 cells treated with 4 μM β-lapachone for 18 h. (i) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with 4 μM β-lapachone or 5 μM MG132 for 18 h, collected and stained with 7-AAD and Annexin V. Cell death was determined by flow cytometry. Values correspond to the percentage of cells in those quadrants. (j) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with 4 μM β-lapachone for 18 h, collected and stained with propidium iodide. PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry. (k) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with 4 μM β-lapachone for 18 h, stained with PI and Hoechst33342, and analyzed with a fluorescence microscope. (l) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h (left panel) or 4 μM β-lapachone for indicated time periods (right panel). The levels of HMGB1 in whole cell and culture media were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-HMGB1 antibody. The values in b, c, e, f, g, and j represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3). *P<0.05 compared with the control

To verify β-lapachone-induced cell death, we checked detailed cellular images with transmission electron microscope (TEM). We observed the disappearance of plasma membrane integrity and the presence of cellular organelles in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figure 1h). Flow cytometry analysis with Annexin V/7-AAD double staining and PI staining were used to distinguish apoptotic cells and necrotic cells.28 β-Lapachone induced the Annexin V(−)/7AAD(+) and Annexin V(+)/7AAD(+) population, but MG132 induced the Annexin V(+)/7AAD(−) and Annexin V(+)/7AAD(+) population (Figure 1i). Uptake of PI was also increased (Figures 1j and k). To further confirm that β-lapachone-mediated cell death is associated with necrotic cell death, we checked whether the high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) was passively released in β-lapachone-treated cells.29, 30 Release of HMGB-1 to culture media (supernatant) was dose- and time-dependently increased in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figure 1l). These results indicate that a reduction of viability by β-lapachone is related to necrotic cell death.

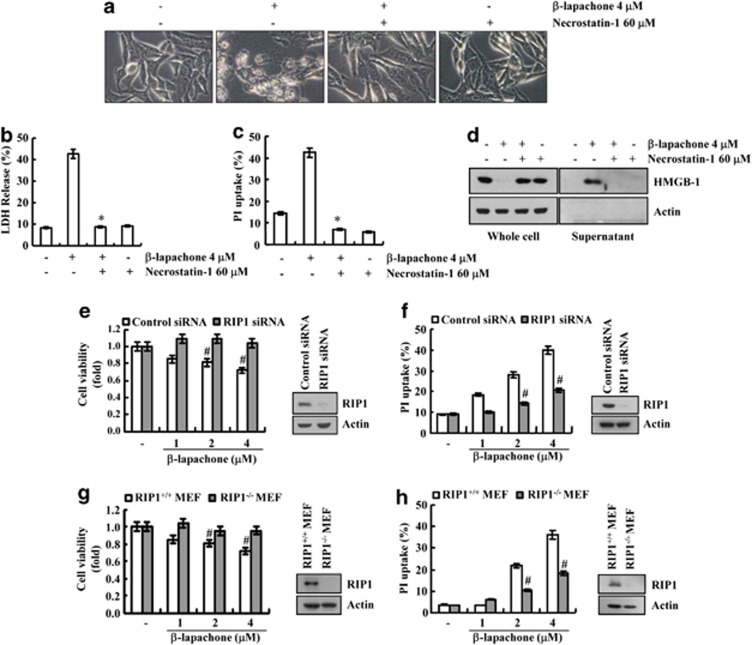

β-Lapachone induces RIP1-dependent necroptosis in SK-Hep1 cells

In our system, to test whether β-lapachone-induced necrosis is truly programmed necrosis, we used a necrostatin-1, an inhibitor for RIP1-dependent programmed necrosis.19 Necrostatin-1 completely blocked β-lapachone-induced morphological change, cell death and PI uptake (Figures 2a–c). β-Lapachone-induced leakage of HMGB-1 was also inhibited by necrostatin-1 (Figure 2d). Furthermore, knock down of RIP1 by RIP1 siRNA markedly inhibited β-lapachone-mediated suppression of cell viability and induction of PI uptake (Figures 2e and f). To further examine whether β-lapachone-induced cell death is mediated through RIP1, we investigated the effects of β-lapachone on cell death in wild-type MEF cells and RIP1−/− MEF cells. β-Lapachone reduced cell viability in wild-type MEF cells, whereas β-lapachone had no effect on cell viability and PI uptake in RIP1−/− MEF cells (Figures 2g and h). These data indicate that β-lapachone induces RIP1-dependent necroptosis in SK-Hep1 cells.

Figure 2.

β-Lapachone induces RIP1-dependent necroptosis. (a) SK-Hep1 cells stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 60 μM necrostatin-1 for 18 h. The cell morphologies were determined by interference light microscopy. Images were magnified × 200. (b, c) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 60 μM necrostatin-1 for 18 h. Cell death was analyzed with the LDH release (b). Cells stained with propidium iodide, and PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry (c). (d) SK-Hep1 cells stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 60 μM necrostatin-1 for 18 h. The levels of HMGB1 in whole cell and culture media were determined by immunoblotting with an anti-HMGB1 antibody. (e, f) SK-Hep1 cells were transfected with RIP1 siRNA or control siRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h. Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (left panel). The RIP1 protein levels were determined by Western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control (right panel) (e). Cells stained with propidium iodide, and PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry (f). (g, h) MEF and RIP1−/− MEF cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h. Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (left panel). The RIP1 protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control (right panel) (g). Cells stained with propidium iodide, and PI uptake was determined by flow cytometry (h). The values in b, c, e, f, g, h represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3). *P<0.05 compared with the β-lapachone alone. #P<0.05 compared with the control siRNA or RIP+/+ MEF

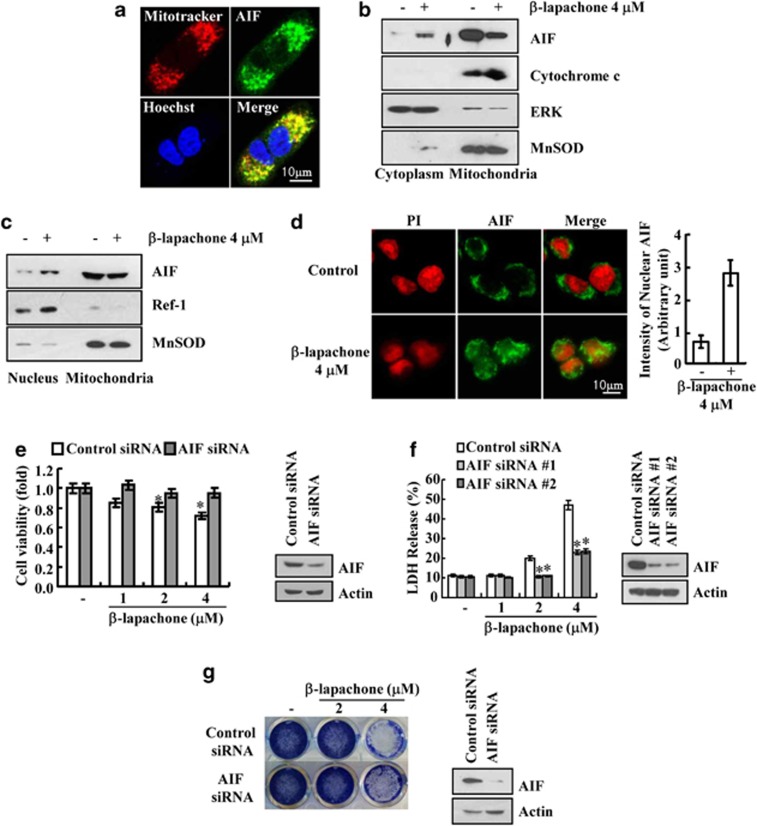

AIF is involved in β-lapachone-induced necroptosis in SK-Hep1 cells

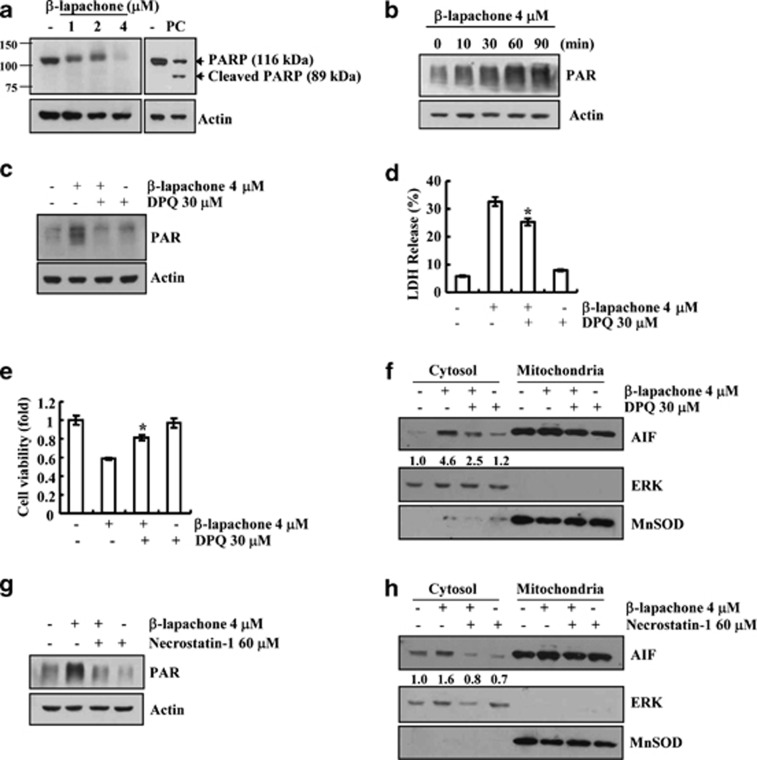

Because AIF is another mediator of necroptosis, we checked whether AIF is associated with β-lapachone-mediated necroptosis. In the absence of stimuli, AIF existed in the mitochondria (Figure 3a), but β-lapachone induced the translocation of AIF from the mitochondria to the cytosol and nucleus of SK-Hep1 cells (Figures 3b–d). However, cytochrome C remained in mitochondrial fraction in β-lapachone-treated cells. Therefore, we ruled out general mitochondrial disruption (Figure 3b). Furthermore, knock down of AIF by siRNA overcame this β-lapachone-mediated cell death (Figures 3e and f). Furthermore, β-lapachone markedly reduced clonogenicity, and knock down of AIF by siRNA partially reversed the reduction of clonogenicity (Figure 3g). There is accumulating evidence that the activation of PARP-1 induced nuclear translocation of AIF.22, 31 To examine the involvement of PARP-1 in β-lapachone-induced necroptosis, we examined whether β-lapachone induces PAR accumulation, which is an indicator of PARP-1 hyperactivation. β-Lapachone induced a loss of the PARP pro-form and increased an atypical PARP form. However, the caspase-mediated cleaved PARP form (89 kDa fragment) was not detected in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figure 4a). Furthermore, β-lapachone induced PAR accumulation (Figure 4b). To confirm the accumulation of PARP-1-mediated PAR, we examined the effects of pharmacological PARP inhibitor, DPQ, on PAR accumulation. DPQ markedly inhibited PAR accumulation and cell death, and reduced the inhibition of cell viability in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figures 4c–e). In addition, DPQ blocked β-lapachone-induced AIF translocation to the cytosol (Figure 4f). These data indicate that PARP1-mediated AIF translocation is associated with β-lapachone-induced necroptosis.

Figure 3.

β-Lapachone-induced AIF translocation is associated with necroptosis. (a) SK-Hep1 cells were stained for mitochondria with MitoTracker Red, for AIF with an anti-AIF antibody followed by an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody and for nuclei with Hoechst staining. (b, c) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone. Cytoplasmic and nucleus fractions were analyzed for cytosol and nucleus translocation of AIF. The protein levels of AIF and cytochrome C were determined by western blotting. The level of ERK was used as a loading control. Ref-1 was used as a nucleus loading control and MnSOD was used as a mitochondria loading control. (d) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone and incubated with antibody against AIF followed by labeling with the FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (PI). Yellow, nuclear translocation of AIF is shown by overlap of AIF (green fluorescence) and nuclear PI staining (red fluorescence). Graph represents relative intensity of nuclear AIF (right panel). (e, f) SK-Hep1 cells were transfected with AIF siRNA or control siRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h. Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (e). Cell death was analyzed using LDH assay (f). The AIF protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control (e, f). (g) SK-Hep1 cells were transfected with AIF siRNA or control siRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 5 days. After treatment, cells were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye. The AIF protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control. The values in d, e, f represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3). *P<0.05 compared with the control siRNA

Figure 4.

β-Lapachone induces necroptosis via RIP1-PARP-1-AIF signaling. (a) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone and 300 ng/ml TRAIL (PC; positive control) for 18 h. (b) SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated time of 4 μM β-lapachone. (c) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 30 μM DPQ for 1 h. (d, e) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 30 μM DPQ for 18 h. Cell death was analyzed with the LDH release (d). Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (e). (f) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of 50 μM DPQ for 14 h. Cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed for AIF cytosol translocation. (g) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of necrostatin-1 (60 μM) for 1 h. (h) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of necrostatin-1 (60 μM) for 14 h. Cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed for AIF cytosol translocation. Fractionation was performed and the translocation of AIF was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-AIF antibody. The PARP (a), PAR (b, c, g), and AIF (f, h) protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin and ERK was used as a loading control. MnSOD was used as a mitochondria loading control. The values in d, e represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3). *P<0.05 compared with the β-lapachone

Because RIP1 is associated with PARP-1 activation and AIF translocation,32, 33 we investigated whether RIP1 is an upstream signal of PARP-1 and AIF. Necrostatin-1 markedly blocks β-lapachone-mediated PAR accumulation and AIF translocation to the cytosol (Figures 4g and h). These data indicate that RIP1 regulates PARP1 hyperactivation and AIF translocation, leading to the induction of necroptosis.

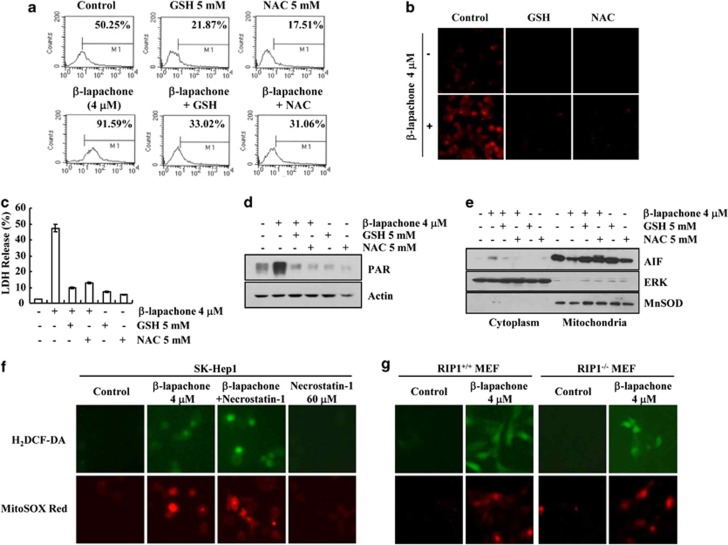

β-Lapachone induces necroptosis via ROS generation in SK-Hep1 cells

Intracellular ROS production is a crucial event mediating cancer cell death, and ROS are also important mediators of necroptosis.34 Furthermore, when NQO1 metabolizes β-lapachone, ROS are induced. Therefore, we examined whether ROS are involved in β-lapachone-induced necroptosis.7, 8, 9 As shown in Figures 5a and b, β-lapachone increased intracellular ROS generation. When ROS scavengers (Glutathione (GSH) and N-acetylcysteine (NAC)) were pretreated in β-lapachone-treated cells, β-lapachone-induced ROS production was completely blocked (Figures 5a and b). Moreover, β-lapachone-induced cell death was also inhibited by GSH and NAC (Figure 5c). Next, we examined whether ROS are upstream signals of PARP-1 and AIF. GSH and NAC markedly reduced PAR accumulation (Figure 5d) and blocked AIF translocation to the cytosol in β-lapachone-treated cells (Figure 5e). These results clearly suggest that upregulation of intracellular ROS is involved in β-lapachone-induced necroptosis.

Figure 5.

β-Lapachone induces programmed necrosis via ROS generation in SK-Hep1 cells. (a, b) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of GSH (5 mM) or NAC (5 mM) for 1 h, and loaded with a fluorescent dye, H2DCF-DA. H2DCF-DA fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry (a). MitoSOX Red intensity was analyzed with fluorescent microscope (b). (c, d) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of GSH (5 mM) or NAC (5 mM) for 18 h (c) or 1 h (d). Cell death was analyzed via the LDH release (c). PAR accumulation was determined by western blotting (d). (e) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of GSH (5 mM) or NAC (5 mM) for 14 h. Fractionation was performed and the translocation of AIF was determined by immunoblotting with an anti-AIF antibody. The level of ERK was used as a loading control and cytoplasmic fraction marker, and MnSOD was used as a loading control and mitochondria fraction marker. (f) SK-Hep1 cells were stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of necrostatin-1 (60 μM) for 1 h, and loaded with fluorescent dye, H2DCF-DA or MitoSOX Red. H2DCF-DA and MitoSOX Red fluorescence intensity was analyzed with fluorescent microscope. (g) RIP1+/+ MEF and RIP1−/− MEF cells were treated with or without 4 μM β-lapachone for 1 h, and loaded with H2DCF-DA or MitoSOX Red. H2DCF-DA and MitoSOX Red intensity was analyzed with fluorescent microscope. The values in c represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3)

Because ROS could induce RIP1 activation,35 we checked whether β-lapachone-mediated ROS production acts as an upstream signaling of RIP1. As shown in Figure 5f, β-lapachone markedly increased intracellular ROS production, but necrostatin-1 had no effect on β-lapachone-mediated ROS production. To further confirm these data, we determined ROS levels in β-lapachone-treated wild-type MEF cells and RIP1−/− MEF cells. As expected, β-lapachone increased intracellular ROS production in both cells of wild-type MEF cells and RIP1−/− MEF cells (Figure 5g). These data indicate that ROS act as an upstream signal of RIP1 and are important mediators in β-lapachone-induced necroptosis in SK-Hep1 cells.

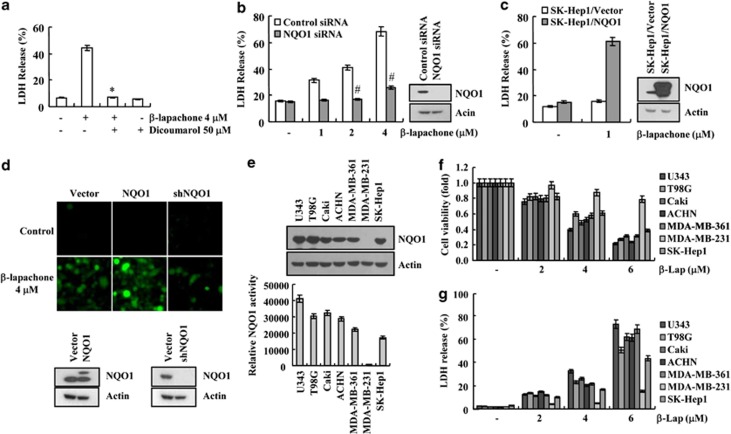

β-Lapachone-induced necroptosis is dependent on NAD(P)H: quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1)

According to previous reports, the anticancer activity of β-lapachone is mainly mediated and promoted by NQO1.7 Therefore, we examined the relationship between NOQ1 and β-lapachone-induced necroptosis in SK-Hep1 cells. First, we tested whether dicoumarol, a well-known NQO1 enzyme activity inhibitor, modulated β-lapachone-induced necroptosis. Dicoumarol completely blocked β-lapachone-induced necroptosis (Figure 6a). Downregulation of NQO1 by NQO1 siRNA markedly reduced β-lapachone-induced necroptosis (Figure 6b). In contrast, when NQO1 was overexpressed, sensitivity against β-lapachone-induced cell death was markedly increased (Figure 6c). In our study, 1 μM β-lapachone had no effect on cell death, but NQO1 overexpresssion potentiated β-lapachone-mediated cell death (Figure 6c). In addition, we examined whether NQO1 levels affected β-lapachone-induced ROS generation. β-Lapachone greatly induced ROS production in NQO1-overexpressed cells, whereas knockdown of NQO1 by shNQO1 reduced β-lapachone-mediated ROS production (Figure 6d). To further confirm the functional importance of NQO1, we examined whether expression levels of NQO1 are related with sensitivity against β-lapachone-induced cell death in human glioma cells (U343 and T98G), human renal carcinoma cells (Caki and ACHN), human breast carcinoma cells (MDA-MB-361 and MDA-MB-231) and SK-Hep1 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells expressed low NQO1 levels and activity, and they were the most resistant against β-lapachone, while other cells showed similar expression levels and activity of NQO1, and reduction of cell viability was markedly reduced by β-lapachone (Figures 6e–g). Therefore, our data suggest that β-lapachone-induced necroptosis is associated with NQO1 activity. Taken together, our results reveal first that RIP1 is an important upstream signaling molecule on β-lapachone-induced necroptosis. Furthermore, β-lapachone induces necroptosis through the ROS-mediated RIP1-PARP1-AIF signaling pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells. Collectively, we suggest that β-lapachone might be an effective therapeutic agent in NQO1-expressed tumor cells.

Figure 6.

β-Lapachone induces programmed necrosis through NQO1 enzyme activity in SK-Hep1 cells. (a) SK-Hep1 cells stimulated with 4 μM β-lapachone in the presence or absence of dicoumarol (50 μM) for 18 h. Cell death was analyzed with LDH release. (b) SK-Hep1 cells were transfected with NQO1 siRNA or control siRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 18 h. Western blotting analysis and LDH assay were performed. (c) Vector cells (SK-Hep1/Vector) and NQO1 overexpressed cells (SK-Hep1/NQO1) were treated with 1 μM β-lapachone for 18 h. Cell death was analyzed using LDH assay (left panel). Western blotting analysis was performed for confirmed overexpression of NQO1 (right panel). (d) SK-Hep1 cells were transfected with vector, NQO1 and NQO1 shRNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell were treated with 4 μM β-lapachone for 1 h, and loaded with fluorescent dye, H2DCF-DA. H2DCF-DA fluorescence intensity was analyzed with a fluorescent microscope. The NQO1 protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control. (e) The NQO1 protein levels were determined by western blotting. The level of actin was used as a loading control (upper panel). NQO1 activity was determined in cell extracts prepared from U343, T98G, Caki, ACHN, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-231 and SK-Hep1 cells (lower panel). (f, g) U343, T98G, Caki, ACHN, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-231 and SK-Hep1 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of β-lapachone for 14 h. Cell viability was analyzed using XTT assay (f). Cell death was analyzed with LDH assay (g). The values in a, b, c, e, f, g represent the mean±S.D. from three independent samples (n =3). *P<0.05 compared with the β-lapachone. #P<0.05 compared with the control siRNA, respectively

Discussion

In this study, we show that β-lapachone induces both PARP-1 hyperactivation-mediated AIF release from the mitochondria to the nucleus and RIP1-dependent necroptosis. β-Lapachone markedly induced ROS production, and intracellular ROS production was associated with this necroptosis. In addition, we found that NQO1 expression was closely correlated with sensitivity against β-lapachone-mediated cell death. Collectively, our results suggest that β-lapachone induces necroptosis through activation of the ROS-mediated RIP1-PARP1-AIF signaling pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma SK-Hep1 cells.

β-Lapachone has been known to induce cell death in breast and non-small-cell lung cancer cells through NQO1 activity and PARP-1 hyperactivation.36, 37, 38 Bey et al.36 reported that β-lapachone increased TUNEL positive in NQO1 activity and PARP-1 hyperactivation-dependent manner. Furthermore, Huang et al.37 reported that β-lapachone killed tumor cells, including non-small-cell lung cancer cells, via PARP-1-dependent necroptosis. However, neither report examined whether RIP1 was involved in β-lapachone-mediated cell death. In our study, β-lapachone increased PARP-1 hyperactivation and the nucleus localization of AIF. We revealed first that RIP1 kinase activity is important to β-lapachone-induced necroptosis, and RIP1 is an upstream signaling molecule of PARP-1-AIF signal in β-lapachone-treated cells.

It has been shown that RIP1 kinase activation is dependent upon receptor-mediated signaling. However, Shen et al.35 suggested that ROS also induce RIP kinase activation in a receptor-independent manner. When H2O2 (500 μM) increases caspase-independent cell death in MEF cells, H2O2-induced RIP activation is independent of TNF receptor activation. H2O2 induces RIP1 localization in the membrane lipid raft, and then it initiates RIP1-dependent death signal.34 In our study, because β-lapachone also markedly increased intracellular ROS production (Figures 5a, b, f and g), β-lapachone probably activated RIP1 through upregulation of localization of RIP into the membrane lipid raft. However, we need further experiments to clarify this hypothesis.

The anticancer activity of β-lapachone is correlated with the enzyme activity of NQO1. For example, when the expression and enzyme activity of NQO-1 are high, β-lapachone induced cell death and dicoumarol inhibited cell death. In contrast, LNCap (prostate cancer) and MDA-MB-468 (breast cancer) cells, in which NQO1 are unexpressed and NQO1 enzyme activity is very low, showed a resistance against β-lapachone, and dicoumarol had no effect on cell death.6, 7 In our study, because β-lapachone-induced cell death was completely inhibited by dicoumarol, β-lapachone increased cell death in a NQO1-dependent manner (Figure 6a). Furthermore, we also found that ectopic expression of NQO1 increased sensitivity against β-lapachone (Figure 6c), and the level and enzyme activity of NQO1 are correlated with β-lapachone-mediated cell death in multiple cells (Figure 6e–g). In normal human hepatocytes, NQO1 expression and activity are very low, but NQO1 is usually elevated in the pre-neoplastic lesions of liver and liver cancers.11 Therefore, our results suggest that β-lapachone may be an effective agent for the induction of cell death in highly NQO-1-expressed cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (SK-Hep1), human glioma cells (T98G), human renal carcinoma cells (Caki and ACHN), human breast carcinoma cells (MDA-MB-361 and MDA-MB-231) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA), and the U343 glioma cell line was generously provided by Dr. Yun C.O. (Hanyang University, Korea). RIP+/+ MEF and RIP1−/− MEF were a gift from Dr. You-Sun Kim (Ajou University, Korea). The culture medium used throughout these experiments was Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 20 mM HEPES buffer and 100 μg/ml gentamycin. β-Lapachone, MG132, N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), glutathione (GSH), diphenyliodonium (DPI), DPQ and dicoumarol were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Necrostatin-1 and zVAD-fmk were obtained from Merck millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) was obtained from Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany). Anti-PARP-1, PAR, AIF and NQO1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-RIP1 antibody was purchased from BD Transduction Labortories (San Jose, CA, USA). The anti-ERK antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The anti-HMGB1 was purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA), and anti-actin was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.

Cell viability assay

XTT assay was employed to measure the cell viability using WelCount Cell Viability Assay Kit (WelGENE, Daegu, Korea). In brief, 24 h after drug treatment, reagent was added to each well and was then measured with a multi-well plate reader (at 450 nm/690 nm).

DEVDase (caspase-3) activity assay

To evaluate DEVDase (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-ase) activity, cell lysates were prepared after being administered the appropriate treatment. The assays were performed in 96-well plates by incubating 20 μg of cell lysate in 100 μl of reaction buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 137 mM NaCl and 10% glycerol) containing the caspase substrate (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-chromophore p-nitroanilide; DEVD-pNA) at 5 μM. Lysates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Thereafter, activity was measured at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Transmission Electron microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), adherent cells were washed twice with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, detached using a cell scraper and mixed with cells floating in media. Cells were then centrifuged at 625 × g for 7 min, and pellets were prefixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 h, followed by post fixation in 1% osmium tetraoxide (OsO4) in 0.2 M cacodylate buffer. Cells were subsequently dehydrated in an ascending graded ethanol series, embedded in resin and polymerized for 48 h at 60 °C. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and examined using a Philips EM 208 electron microscope (Philips Electronic Instruments, Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Annexin V and 7-AAD Staining

FITC-conjugated Annexin V (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (BD Pharmingen) were used for distinguishing cell death mode. Cells were washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in Annexin V–binding buffer at a concentration of 3 × 106/ml. This suspension (100 μl) was stained with 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl 7-AAD. 7-AAD is a nucleic acid dye that was used for the exclusion of nonviable cells. The cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After addition of 400 μl of binding buffer to each tube, cells were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on a FACS Canto (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA).

Western blotting

Cellular lysates were prepared by suspending 0.4 × 106 cells in 100 μl of lysis buffer (137 mM NaCl, 15 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 25 mM MOPS, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 20 μM leupeptin, adjusted to pH 7.2). The cells were disrupted by vortex and extracted at 4 °C for 30 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant fractions were collected. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). The detection of specific proteins was carried out using a chemiluminescence western blotting kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (WBKLS0500; Millipore Corporation).

Propidium iodide (PI) uptake and staining

The cells were collected, resuspended in 100 μl of binding buffer, and stained by applying propidium iodide (final 5 μg/ml) and Hoechst33342 (final 10 μg/ml) for 15 min at room temperature. The stained cells were analyzed by FACS and fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Gőettingen, Germany).

Medium concentration for HMGB-1 release

For detection of the released HMGB-1 protein, whole media were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min to remove cellular debris. Then, supernatants were then collected and concentrated by 14 000 × g for 10 min using Nanosep 10 K centrifugal devices (Pall Life Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Lactate dehydrogenase Release assay

Cell death was estimated by determining LDH released into the culture medium. LDH released into the phenol red-free medium was determined using a LDH assay kit and procedures described by the manufacturer's instruction (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany).

Fractionation of cytosolic, nuclear and mitochondrial extracts

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, then resuspended in isotonic buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na-EDTA, 1 mM Na-EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing a proteinase inhibitor and left on ice for 10 min and then lysate was passed through a 25G needle 10 times using a 1 ml syringe. The lysates were centrifuged at 720 × g for 5 min, supernatant (contain cytoplasm and mitochondria fraction) was transferred to a new tube and nuclear fraction (pellets) was suspended with lysis buffer and boiled with 5 × loading buffer. The supernatants were spin down again at 6000 × g for 10 min, mitochondria fraction was obtained from pellets and cytosolic fraction was obtained from the supernatant. Cytosolic fraction was boiled with 5 × loading buffer, and mitochondrial fraction was suspended with lysis buffer and boiled with 5 × loading buffer.

Small-interfering RNAs

The GFP (control), RIP1, AIF (#1 and #2) and NQO1 small-interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes used in this study were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides using Oligofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy for AIF Translocation

Cells were cytospun onto noncharged slides (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), fixed for 20 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed again with PBS and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature and washed with PBS. To reduce nonspecific antibody binding, slides were incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature before incubation with rabbit polyclonal antibody to human AIF overnight at 4 °C. Slides were then washed for 30 min in PBS and incubated for 1 h with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA). Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide for 15 min at room temperature. Slides were washed and dried in air before they were mounted on coverslips with ProLong Antifade mounting medium (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). They were then examined under a Zeiss LSM 510 multiphoton confocal microscope (Zeiss, Gőettingen, Germany).

Clonogenic assay

Cells were suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS, then plated in six-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well). Cells were treated with β-lapachone for 5 days. After treatment, colonies were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye.

Measurement of ROS and mitochondrial ROS Generation

The generation of ROS was measured by using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) as a substrate, and mitochondrial superoxide/ROS generation was determined by MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen). In brief, cells were incubated with 10 μM H2DCF-DA or 2.5 μM MitoSOX Red for 30 min before collection. For quantitative assessment of ROS generation, cells were collected, suspended in PBS and analyzed by the green fluorescence intensity from 10 000 cells with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For image taking, H2DCF-DA or MitoSOX Red loaded cells were visualized using a fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss, Axiovert 200).

Cloning of human NQO1 and stable cell

Human NQO1 gene was amplified by PCR using specific primers from the human NQO1 gene (Accession No. BC007659.2). The sequences of the sense and antisense primers for NQO1were 5′-GCCCCAGATCTCACCAGAGCCATG-3′ and 5′-TCCAG TCTAGAGAATCTCATTTTC-3′, respectively. The NQO1 cDNA fragment was digested with Bgl II and Xba I and subcloned into the pFLAG-CMV-4 vector and termed pFLAG-CMV-4-NQO1. The SK-Hep1 cells were transfected in a stable manner with the pFLAG-CMV-4-NQO1 and control plasmid pFLAG-CMV-4 vector using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h of incubation, transfected cells were selected in cell culture medium containing 700 μg/ml G418. After 2 or 3 weeks, single independent clones were randomly isolated, and each individual clone was plated separately. After clonal expansion, cells from each independent clone were tested for NQO1 expression by immunoblotting.

NQO1 and shNQO1 transfection

For transfection, cells were plated in six-well plates (2 × 106 cells/well) for overnight, and then the cells were incubated for 24 h with the NQO1 and shNQO1 plasmids in the Fugene transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science). shNQO1 was generously provided by Dr. H. J. Park (Inha University, Korea).

NQO1 Activity Assay

Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in NQO1 activity assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). After centrifugation for 5 min at 9000 × g, an appropriate amount of cell lysates was added to the reaction mixture, containing 100 μM NADPH in a final volume of 200 μl PBS (pH 7.4). The reaction was initiated by the addition of resorufin, resulting in a final concentration of 500 nM resorufin in the mixture. The activity was monitored at 590/522 nm in a microplate reader at room temperature for 5 min in the absence or presence of 10 μM dicoumarol.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc comparisons (Student-Newman-Keuls) using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mid-Career Researcher Program through an NRF grant funded by the MEST (No. 2011-0016239) and Keimyung Basic Medical Research Promoting Grant launched from 2012.

Glossary

- NQO1

NAD(P)H: quinine oxidoreductase-1

- PARP-1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RIP1

receptor interacting protein-1

- MNNG

N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine

- HMGB1

high mobility group box-1

- GSH

glutathione

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by A Oberst

References

- Schaffner-Sabba K, Schmidt-Ruppin KH, Wehrli W, Schuerch AR, Wasley JW. beta-Lapachone: synthesis of derivatives and activities in tumor models. J Med Chem. 1984;27:990–994. doi: 10.1021/jm00374a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CJ, Wang C, Pardee AB. Induction of apoptosis by beta-lapachone in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3712–3715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau YP, Shiah SG, Don MJ, Kuo ML. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in topoisomerase inhibitor beta-lapachone-induced apoptosis and differentiation in human leukemia cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:660–670. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Ji IM, Ahn KJ, Choi EK, Park HJ, Lim BU, et al. Synergistic effect of ionizing radiation and beta-Lapachone against RKO human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res Treatment. 2005;37:183–190. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Amano M, Choi J, Park HJ, Williams BW, Ono K, et al. Synergistic effects of radiation and beta-lapachone in DU-145 human prostate cancer cells in vitro. Radiation Res. 2006;165:525–531. doi: 10.1667/RR3554.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchon SM, Pink JJ, Tagliarino C, Bornmann WG, Varnes ME, Boothman DA. beta-Lapachone-induced apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells: involvement of NQO1/xip3. Exp Cell Res. 2001;267:95–106. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink JJ, Planchon SM, Tagliarino C, Varnes ME, Siegel D, Boothman DA. NAD(P)H:Quinone oxidoreductase activity is the principal determinant of beta-lapachone cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5416–5424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D, Yan C, Ross D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in the sensitivity and resistance to antitumor quinones. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129:77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docampo R, Cruz FS, Boveris A, Muniz RP, Esquivel DM. beta-Lapachone enhancement of lipid peroxidation and superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide formation by sarcoma 180 ascites tumor cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:723–728. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D, Ross D. Immunodetection of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in human tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:246–253. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassburg A, Strassburg CP, Manns MP, Tukey RH. Differential gene expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase and NRH:quinone oxidoreductase in human hepatocellular and biliary tissue. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:320–325. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor NA, Morris HP. The activity of the D-T diaphorase in experimental hepatomas. Cancer Biochem Biophys. 1977;2:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresteil T, Jaiswal AK. High levels of expression of the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) gene in tumor cells compared to normal cells of the same origin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90284-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlager JJ, Powis G. Cytosolic NAD(P)H: (quinone-acceptor)oxidoreductase in human normal and tumor tissue: effects of cigarette smoking and alcohol. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:403–409. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon LJ, Pasupuleti N, Gorin F, Carraway KL., 3rd A cell-permeant amiloride derivative induces caspase-independent, AIF-mediated programmed necrotic death of breast cancer cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e63038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Mier JW, Panka DJ. Differential modulatory effects of GSK-3beta and HDM2 on sorafenib-induced AIF nuclear translocation (programmed necrosis) in melanoma. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:115. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Sun X, Yin J, Starovasnik MA, Fairbrother WJ, Dixit VM. Identification of a novel homotypic interaction motif required for the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein (RIP) by RIP3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9505–9511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch'en IL, Korkina O, Teng X, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Kroemer G. RIP kinases initiate programmed necrosis. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009;1:8–10. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delavallee L, Cabon L, Galan-Malo P, Lorenzo HK, Susin SA. AIF-mediated caspase-independent necroptosis: a new chance for targeted therapeutics. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:221–232. doi: 10.1002/iub.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boujrad H, Gubkina O, Robert N, Krantic S, Susin SA. AIF-mediated programmed necrosis: a highly regulated way to die. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2612–2619. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabon L, Galan-Malo P, Bouharrour A, Delavallee L, Brunelle-Navas MN, Lorenzo HK, et al. BID regulates AIF-mediated caspase-independent necroptosis by promoting BAX activation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:245–256. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Huang S, Liu ZG, Han J. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 signaling to mitochondria in necrotic cell death requires RIP1/TRAF2-mediated JNK1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8788–8795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu LY, Ho FM, Shiah SG, Chang Y, Lin WW. Oxidative stress initiates DNA damager MNNG-induced poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1-dependent parthanatos cell death. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenknecht B, Hermisson M, Groscurth P, Liston P, Krammer PH, Weller M. Proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis of glioma cells involves the processing of multiple caspases and cytochrome c release. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2288–2297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darzynkiewicz Z, Juan G, Li X, Gorczyca W, Murakami T, Traganos F. Cytometry in cell necrobiology: analysis of apoptosis and accidental cell death (necrosis) Cytometry. 1997;27:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysko DV, Vanden Berghe T, D'Herde K, Vandenabeele P. Apoptosis and necrosis: detection, discrimination and phagocytosis. Methods. 2008;44:205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings BS, Wills LP, Schnellmann RG. Measurement of cell death in Mammalian cells. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2012;56:12.8.1–12.8.24. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph1208s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk SJ, Hageman GJ. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 mediated caspase-independent cell death after ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouan-Lanhouet S, Arshad MI, Piquet-Pellorce C, Martin-Chouly C, Le Moigne-Muller G, Van Herreweghe F, et al. TRAIL induces necroptosis involving RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent PARP-1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:2003–2014. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chua CC, Kong J, Kostrzewa RM, Kumaraguru U, Hamdy RC, et al. Necrostatin-1 protects against glutamate-induced glutathione depletion and caspase-independent cell death in HT-22 cells. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2004–2014. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Yi J. Cancer cell killing via ROS: to increase or decrease, that is the question. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1875–1884. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.7067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Lin Y, Choksi S, Tran J, Jin T, Chang L, et al. Essential roles of receptor-interacting protein and TRAF2 in oxidative stress-induced cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5914–5922. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5914-5922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey EA, Reinicke KE, Srougi MC, Varnes M, Anderson VE, Pink JJ, et al. Catalase abrogates beta-lapachone-induced PARP1 hyperactivation-directed programmed necrosis in NQO1-positive breast cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2110–2120. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Dong Y, Bey EA, Kilgore JA, Bair JS, Li LS, et al. An NQO1 substrate with potent antitumor activity that selectively kills by PARP1-induced programmed necrosis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3038–3047. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey EA, Bentle MS, Reinicke KE, Dong Y, Yang CR, Girard L, et al. An NQO1- and PARP-1-mediated cell death pathway induced in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by beta-lapachone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11832–11837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702176104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]