Abstract

Significance: The broad classes of O2-binding proteins known as hemoglobins (Hbs) carry out oxygenation and redox functions that allow organisms with significantly different physiological demands to exist in a wide range of environments. This is aided by allosteric controls that modulate the protein's redox reactions as well as its O2-binding functions. Recent Advances: The controls of Hb's redox reactions can differ appreciably from the molecular controls for Hb oxygenation and come into play in elegant mechanisms for dealing with nitrosative stress, in the malarial resistance conferred by sickle cell Hb, and in the as-yet unsuccessful designs for safe and effective blood substitutes. Critical Issues: An important basic principle in consideration of Hb's redox reactions is the distinction between kinetic and thermodynamic reaction control. Clarification of these modes of control is critical to gaining an increased understanding of Hb-mediated oxidative processes and oxidative toxicity in vivo. Future Directions: This review addresses emerging concepts and some unresolved questions regarding the interplay between the oxygenation and oxidation reactions of structurally diverse Hbs, both within red blood cells and under acellular conditions. Developing methods that control Hb-mediated oxidative toxicity will be critical to the future development of Hb-based blood substitutes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 2298–2313.

General Principles

Emergence of proteins capable of transporting O2

In this review, we examine the adaptive changes in the molecular controls of hemoglobin (Hb) oxygenation and oxidation that have evolved to meet the highly varied physiological and environmental demands of respiring organisms. Globins came into being during the planet's long early period of anoxia/hypoxia, and recent studies show that globins are either expressed or inducible in almost all cells (98). Studies have shown that one evolutionary pathway of Hb is that of a multipurpose domain attached to a variety of unrelated proteins, thus forming molecules with different functions (126). This pathway has allowed structurally distinct Hbs to evolve: (i) to protect against the high levels of nitrosative stress of the earth's early environment; (ii) to protect against O2-linked oxidation; (iii) to act as O2 sensors that help regulate the expression of proteins during periods of hypoxia or anoxia; and (iv) to enable aerobic respiration by facilitating diffusion and/or acting as O2 carriers (44, 56, 57, 70, 71, 73, 107). A common theme in the fascinating story of Hb evolution is the emergence of distinct mechanisms for controlling Hb's oxygenation and redox functions.

Since increased amounts of O2 were released in our planet's early history, O2 toxicity brought about species extinction on a global scale. On the other hand, this “oxygen pollution” made possible a new biological process, that of aerobic respiration. A tremendous gain in the energy obtainable from oxidation of energy-rich metabolites was achieved when organisms evolved aerobic respiration pathways that used molecular O2 as the final electron acceptor. Before O2 was widely available, survival during anoxic/hypoxic interludes may have been enabled by the combined strong O2-binding and redox functionalities of Hbs and Mbs. It is intriguing in this regard that some non-symbiotic plant Hbs enable sustained energy production under anaerobic/hypoxic conditions by exploiting a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) oxidase enzymatic function (9, 66), similar to that of the flavohemoglobin (Hmp) of Escherichia coli (56). The combined O2-binding and redox functions of Hbs and Mbs play important roles in the tissues of current-day organisms (including many invertebrates) where hypoxic interludes are common (122), and protection against nitrosative stress is required (26).

The evolution of aerobic respiration needed the emergence of two broad classes of proteins, one to transport molecular O2 reversibly to cells where respiration takes place, and the other to carry out controlled redox reactions linked to energy production. These functions are made possible by the redox active metals that form the active sites of all O2-carrying proteins. In vertebrate Hbs and Mbs, O2 is reversibly bound by reduced (ferrous) iron, Fe2+. The challenging task accomplished by natural evolutionary processes in designing these O2-carrying proteins was to ensure that the reduced iron does not become oxidized (Fe3+) when it contacts O2. This was made possible by the high sensitivity of both the oxidation-reduction potential and the kinetics of the iron redox reaction to the ligand atoms provided by the globin in the active site iron first and second coordination shell. At physiological pH, the reduction potential of molecular O2 (+0.815 V) is higher than that of aqueous  (+0.770 V), and, hence, molecular O2 has a strong tendency to oxidize

(+0.770 V), and, hence, molecular O2 has a strong tendency to oxidize  . The seemingly impossible feat of allowing reduced metals to contact O2 without becoming oxidized was accomplished by two distinct kinds of proteins, the iron-containing globins (like Hb and Mb) and the copper-containing hemocyanins. In spite of the thermodynamic driving force to produce oxidized Fe3+ and Cu2+ in the active sites of these proteins, the kinetics of the underlying reactions allow these proteins to exist in the reduced state even when they are in contact with O2. This accomplishment allowed multicellular organisms to exploit the advantages of aerobic respiration and triggered the development of intelligent life on our planet.

. The seemingly impossible feat of allowing reduced metals to contact O2 without becoming oxidized was accomplished by two distinct kinds of proteins, the iron-containing globins (like Hb and Mb) and the copper-containing hemocyanins. In spite of the thermodynamic driving force to produce oxidized Fe3+ and Cu2+ in the active sites of these proteins, the kinetics of the underlying reactions allow these proteins to exist in the reduced state even when they are in contact with O2. This accomplishment allowed multicellular organisms to exploit the advantages of aerobic respiration and triggered the development of intelligent life on our planet.

Equation 1 represents the reversible O2 binding by Hb. An alternative oxidative pathway, shown in Equation 2, leads to iron oxidation and a cascade of associated redox reactions.

|

[1] |

|

[2] |

sThe interaction of O2 with Hb via the pathway of Equation 2 produces the superoxide radical anion (O2•−) and ferric (met) Hb, which is unable to participate in O2 binding and transport. This autoxidation reaction occurs over a period of several hours for free Hb, but occurs in a few seconds for free heme. Equation 2 has the potential of initiating a damaging and sometimes life-threatening oxidative cascade (3). The active site geometry provided by the globin of mature normal human Hb (Hb A) does a remarkable job of making the pathway of Equation 1 highly favored over the oxidative pathway of Equation 2. However, in spite of the kinetic obstacles which nature has provided that slow the process of Hb oxidation, ∼1%–3% of the Hb within red blood cells is oxidized daily, and returned to the reduced state by intracellular reductants such as NAD(P)H and other antioxidants within red blood cells (31, 67).

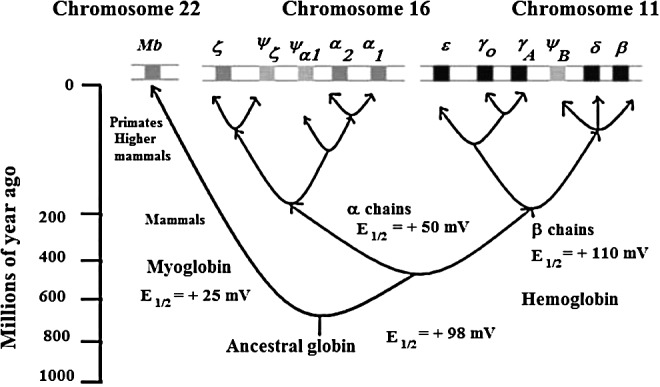

The release of O2 from oxy Hb at sites of cellular respiration is a pivotal event in the aerobic respiration of multicellular organisms where O2 is used as the final electron acceptor in the electron transport chain. Figure 1 shows that an ancestral globin appeared on earth approximately a billion years ago. However, as also shown in Figure 1, nearly 600 million years elapsed before the appearance of tetrameric Hb that is composed of interacting α and β subunits. The formation of Hb heterotetramers not only allowed for cooperativity in O2 affinity, but also created a molecule capable of cooperative redox reactions. The isolated α and β chains of human Hb have rather large differences in redox potential (Fig. 1), even though they bind O2 with similar affinities (27).

FIG. 1.

A cartoon representation of the evolutionary appearance of different heme proteins associated with the hemoglobins (Hbs). The vertical scale gives the time in millions of years when the respective proteins evolved. The top panel shows the gene that encodes different heme proteins. The E1/2 values are versus NHE. The data for myoglobin (horse heart Mb) and Hb (Hb A) are from Ref. (114). Conditions: 0.05 M 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) at pH 7.1. E1/2 values of individual α and β-Hb chains are from Ref. (27). Conditions: 1 M Glycine buffer at pH 6 at 6°C.

Hbs of diverse species have structural features that allow organisms with widely different physiological demands to exist in a wide range of environments. The basis of this functional flexibility, which has intrigued researchers over the years, lies in the ability of strategic amino acid residues to alter the protein's intrinsic O2 affinity and redox potential, and to respond to metabolites that exert allosteric effects. Since Hb oxidation is a normal occurrence in vivo, there are advantages of having allosteric controls that modulate the redox reactions of Hb as well as its O2 transport functions. These advantages and their importance in human physiology and in the life-processes of other organisms are now becoming appreciated. As might have been anticipated, the controls of Hb oxidation can vary from species to species. Moreover, as pointed out in the following sections, the controls of the redox reactions of Hb can differ appreciably from the molecular controls for Hb oxygenation. Although much has been learned, new and often surprising aspects of the Hb story are still being discovered.

Influence of protein structure and heterotropic ligands on Hb oxygenation and oxidation

In this section, we briefly review the structural features that make it possible for the molecular controls of the oxygenation reactions of Hb to differ appreciably from the molecular controls for redox reactions of Hb. We then illustrate the existence of differences in these molecular controls by showing the effects of anions on Hill plots of oxygenation and Nernst plots of oxidation.

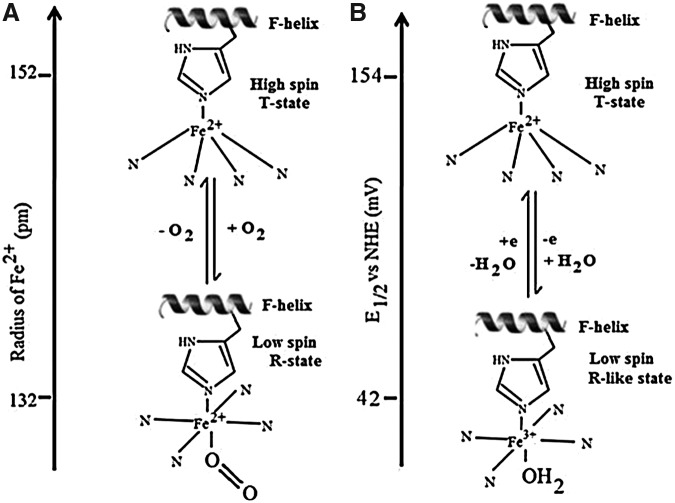

As shown in Figure 2, in the active site of deoxy human Hb, the penta-coordinated Fe2+ (high spin) lies out of the heme plane by about 0.06 nm due to its linkage with the proximal histidine (His) in the F helix (8, 37, 125). O2 approaches and binds the Fe2+-Hb at the heme vacant sixth coordination site, forming a six coordinate Fe2+ complex (low spin). The Fe2+ is not readily oxidized to the Fe3+ state, because the kinetics for Equation 1 are preferred over those for Equation 2. Instead, a change in protein conformation (T- to R-state) is initiated with the result that the reduced metal is pulled into the plane of the heme, and the porphyrin ring becomes less domed. Oxidation of deoxy human Hb results in a similar movement of the heme and active site iron, along with H2O coordination and production of a six coordinate H2O-Fe3+-Hb (metHb) species (8, 37, 42, 125).

FIG. 2.

Cartoon showing a similar in-plane movement of heme iron on oxygenation (left) and oxidation (right). (A) A schematic representation of the movement of the Fe2+ center in Hb associated with the oxygenation process. The deoxy (T-state) Hb having low O2 affinity has a high spin Fe2+ electron configuration with five ligands. On O2 binding, a change in spin state to low spin Fe2+ leads to a more planar oxy (R-state) Hb with higher O2 affinity. The vertical scale on the left shows the change in ionic radius of Fe2+ on changing from the high spin to low spin state. (B) A similar movement of iron on oxidation from Fe2+ deoxy T-state to aquomet R-like Fe3+ state and the vertical scale on the left represents the E1/2 values (vs. NHE) for T- and R-state Hb, respectively. The E1/2 values quoted in (B) are for Hb A in the presence of a large excess of inositol hexaphosphate (IHP) and NaNO3 (T-state stabilized) and carboxypeptidase digested Hb A (R-state stabilized) (42). Conditions: 0.05 M MOPS at pH 7.1.

The proximal-side linkage of heme to the protein's amino acid backbone allows changes in the globin to alter the protein's active site geometry, and the resulting “proximal pull” exerts a direct effect on O2 affinity and redox potential. Distal-side residues also come into play, because the primary heme ligands (O2, CO, and NO) cannot enter or leave the heme pocket without movement of distal residues (8, 37, 93, 125). This constraint is even more dramatic in the hexacoordinate Hbs of some plants and invertebrates, where a distal His bond to the heme iron center should be broken to allow ligand binding (37). In the recently discovered neural globin of Caenorhabditis elegans, the distal His linkage is so strong that ligands (O2, CO, NO) cannot bind. The protein exhibits rapid two-state autoxidation kinetics in the presence of physiological O2 levels, as well as a low redox potential, suggesting a role for this protein in redox signaling and/or electron transfer (125). The rate and extent of distal-side conformational fluctuations that allow for entry and exit of heme ligands can thus be modified by structural alterations of the heme pocket, or by induced alterations as a result of interactions with anionic effectors.

The structure-function relationships underlying the variations of ligand affinity and selectivity among Hbs have been intensively studied since the pivotal determination of Hb's significantly different oxy and deoxy structures (91, 92). As pointed out recently (119), the combined proximal and distal effects in the heme pocket of Hb give rise to a “Sliding Scale Rule” for the physiologically significant heme ligands. By this rule, although there is a million-fold variation in their equilibrium dissociation constants, the ratios for NO:CO:O2 binding stay roughly the same, 1:∼103:∼106, for a wide range of globins when the proximal ligand is a histidine and the distal site is apolar. However, these ratios, which denote the degree of ligand-binding selectivity, can be changed by evolutionary changes or by molecular-engineering alterations of the proximal heme ligand and/or the polarity of the distal site. As brought out in subsequent sections of this review, hindrance to ligand entry or exit from the heme pocket can be altered not only by changes in Hb's amino acid sequence, but also by Hb cross-linking, by binding of anions at regions remote from the heme pocket, and by protonation of strategic residues in Hbs that have evolved the Root effect.

Binding of O2 and other heme ligands to Hb is often represented by graphing the ligand-dependent saturation of the active-site hemes as a Hill plot (60) (Equation 3).

|

[3] |

where θ=concentration of oxyheme, 1−θ=concentration of deoxyheme, L=free (unbound) ligand concentration, Kd=the ligand dissociation constant (equilibrium constant), and n=the Hill coefficient, whose value denotes the degree of cooperativity of ligand binding.

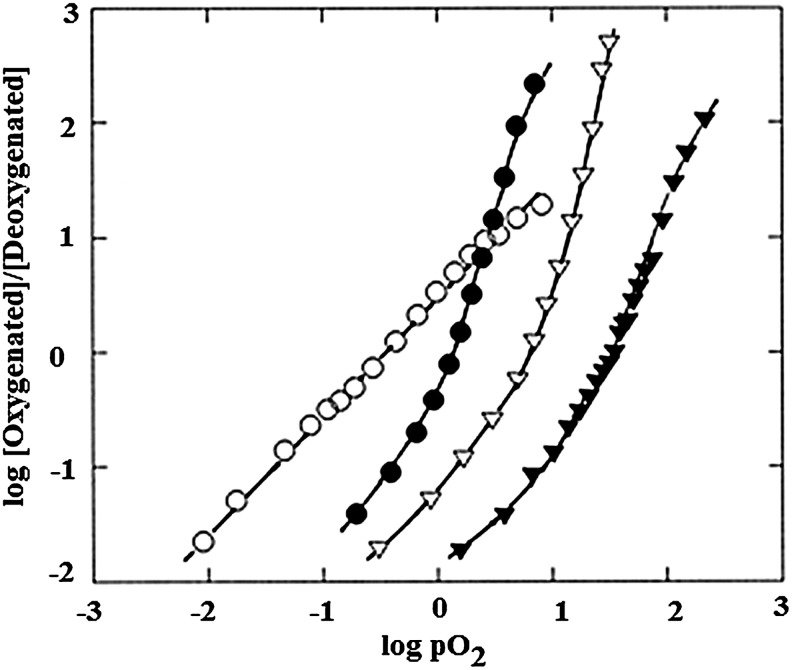

Figure 3 shows that Hill plots of O2 binding to human Hb exhibit sigmoidal curves with nmax values greater than 1, indicative of cooperative interactions between the heme binding sites. Cooperativity is a highly useful functional property exhibited by most mammalian Hbs, which allows for O2 binding and release over a narrow range of O2 concentrations. As is also shown, Hill plots showing non-cooperative ligand binding, with n equal to 1 throughout the binding curve, are exhibited by monomeric proteins such as Mb. Figure 3 also illustrates the shifts in Hb's O2 affinity that are brought about by anionic effectors (41).

FIG. 3.

Hill plots for Hb A and hMb under varied conditions. Plot reproduced from Ref. (41) and used with permission. Symbols: open circles, hMb in 0.05 M MOPS, 0.2 M NaNO3 (log P50=−0.48); closed circle, Hb A in 0.05 M MOPS (log P50=0.15); open triangles, Hb A in 0.05 M MOPS, 0.2 M NaNO3 (log P50=−0.87); closed triangles, Hb A in 0.05 M MPOS, 0.2 M NaNO3, 16-fold excess IHP (log P50=+1.55). The log P50 values show a gradual increase toward higher partial pressure of oxygen from hMb to Hb A in the presence of the T-state stabilizer IHP, representing greater difficulty of oxygenation for T-state stabilized heme proteins. Experiments were performed at neutral pH and at room temperature.

Protons and anions (heterotropic effectors) present in the Hb's environment influence the protein's oxygen affinity, with somewhat different effects exhibited by the constituent α and β chains (8, 72, 82, 85, 87, 92, 96, 103). These effectors have a significant influence on the magnitude of the O2 affinity shift that occurs as the protein shifts between quaternary conformations, to the extent that in some recent articles the importance of the quaternary conformational shift based on homotropic O2 binding has been characterized as being “greatly over-rated” relative to the influence of heterotropic effectors (124). In support of this concept, as shown in Figure 3, the shifts between R- and T-states (estimated by affinities at initial and final stages of the binding curves) are clearly less, under some conditions, than the affinity shifts associated with the binding of effectors.

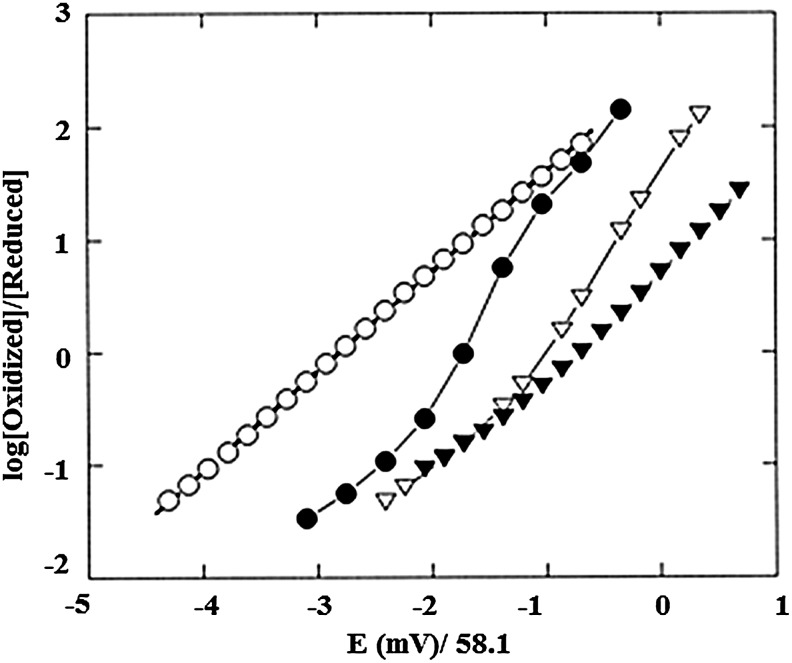

Anaerobic Hb oxidation, similar to Hb oxygenation, is subject to homotropic and heterotropic allosteric controls. These aspects of Hb oxidation are evident in the Nernst plots shown in Figure 4, based on the Nernst equation (Equation 4).

|

[4] |

FIG. 4.

Nernst plot of Hb A and hMb under different conditions obtained from spectroelectrochemistry experiments at 20°C at neutral pH. The potentials are reported versus Ag/AgCl electrode. Plot reproduced from Ref. (41) and used with permission. Symbols: open circles, hMb in 0.05 M MOPS, 0.2 M NaNO3 (E1/2=−160 mV); closed circle, Hb A in 0.05 M MOPS (E1/2=−104 mV); open triangles, Hb A in 0.05 M MOPS, 0.2 M NaNO3 (E1/2=−63 mV); closed triangles, Hb A in 0.05 M MOPS, 0.2 M NaNO3, 10-fold excess IHP (E1/2=−40 mV). The E1/2 values (vs. Ag/AgCl) show a gradual shift toward more positive values as the heme protein conformation changes from R-to-T state, indicating greater ease of reduction for T-state stabilized heme proteins. See text for more explanation.

In Equation 4, R is the gas constant in JK−1 mol−1, T is the temperature in degrees K, n indicates the number of electrons involved in the redox process for an ideal system with Nernstian behavior, F is the Faraday constant, [Ox] and [Red] are the molar concentrations of oxidized and reduced species, Eapp is the solution potential, and E1/2 is the mid-point redox potential of the protein where [Ox]=[Red].

As shown in the Nernst plots of Figure 4, Mb oxidation shows simple Nernstian behavior with a Nernst plot slope (n) of unity, while Hb shows cooperative redox behavior (n>1) and redox shifts in the presence of anionic effectors. Development of cationic mediators (41, 42) for measurement of Hb's redox potential and improved spectroelectrochemical assay methods (112–114) has allowed precise evaluation of the homotropic and heterotropic controls of Hb oxidation under conditions similar to those used for determinations of Hb oxygenation. When the isolated chains are mixed and form tetrameric Hbs, the assembled protein is more resistant to oxidation. The underlying “heterogeneity” of the redox potential of the interacting subunits significantly reduces the slope of the Nernst plots for the assembled Hbs. The nmax values of ∼2 observed for Hb's redox reactions are, as a consequence, less than for Hill plots for oxygenation, where nmax values of >3 are observed.

The similarities and differences in the molecular controls of Hb oxygenation (Fig. 3) relative to those of Hb oxidation (Fig. 4) are central elements of this review.

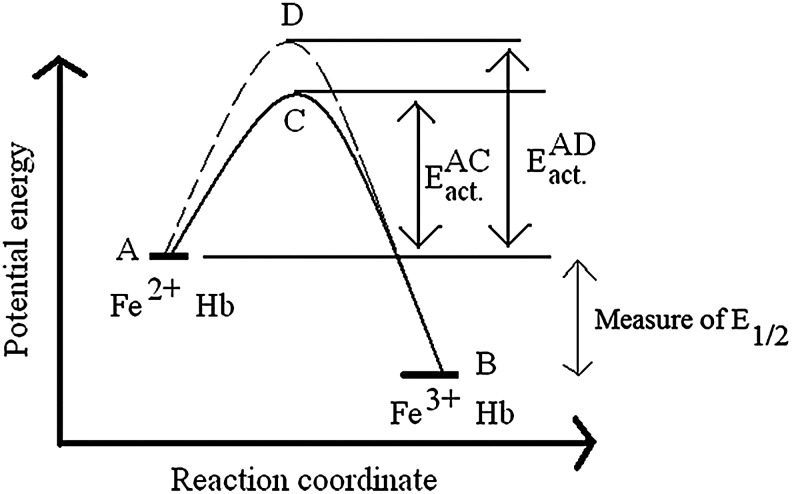

Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of Hb oxidation

In this section, we emphasize a critical issue in studies of Hb's redox functions. This critical issue is the distinction between kinetic and thermodynamic reaction control, as qualitatively illustrated in Figure 5. A fact that is often disregarded in discussing Hb's redox functions is that knowing the redox potential of a reaction provides no information about the kinetics of the oxidative process. Figure 5 illustrates this by showing the oxidation of two hypothetical Hbs showing different rates of oxidation but with identical redox potentials. Energy levels A and B in Figure 5 represent the relative energy levels of the reduced (Fe2+) and oxidized (Fe3+) forms of the two Hbs. The energy difference between A and B defines the redox potential E1/2, which is a measure of the thermodynamic driving force for oxidation.

FIG. 5.

A qualitative energy-level diagram showing the relative energies of Fe2+-Hb and Fe3+-Hb from two different hypothetical Hb samples (represented by solid and dashed lines). The points C and D represent the activated complexes for the two Hb samples that are formed in the course of auto-oxidation as discussed in the text. EACact. and EADact. are measures of how fast the auto-oxidation process would be in these two hypothetical Hb samples. For clarity, the energies of the Fe2+-Hb and Fe3+-Hb from two different species are considered unaltered between species. See text for more explanation.

For the two Hbs to become oxidized (to go from A to B), they should first be activated sufficiently to assume the transition state conformations represented by points C and D in Figure 5. Reactions involving Hb oxidation will occur at different rates depending on the Hb type and the experimental conditions that affect the energy levels of transition states, depicted as EADact and EACact. in Figure 5. The activation energy required, which determines the oxidation reaction rate, is determined by both steric and electronic factors around the heme active site. By evolutionary alterations of these controlling factors in the Hb tetramer, the kinetics of the iron “rusting” process have been dramatically slowed over those observed for free heme.

Hbs with extreme pH and anion sensitivity in O2 binding: the root effect Hbs

Some important general principles of the molecular controls of Hb oxygenation and oxidation have been brought out in recent studies of Root effect Hbs (20). Root effect Hbs (101) are characterized by extreme pH and anion sensitivity. The Root effect enables Hbs to serve as elegant proton-driven molecular pumps for delivering O2 to the swim bladder and eyes of fish, even at great depths. At low pH, their O2 affinities may be so low that full saturation may not be achieved even at 100 atm pressure (16, 104). The remarkable ability of Root effect Hbs to pump O2 against high-pressure gradients results from extreme, acid-induced reductions in O2 affinity and cooperativity. The Root effect has been generally attributed to a great stabilization of the T-state (or destabilization of the R-state) as a result of proton binding. The structural basis of the extreme pH dependence of O2 binding to Root effect Hbs has been a long-standing puzzle in the field of protein chemistry, as no uniform consensus sequence has been identified among the Hbs that demonstrate the phenomena.

Although proton binding generally favors the low affinity (T-state) of Hb, the behavior of Root effect Hbs poses considerable challenges to the two-state model of Hb function (26). Notably, at low pH, the oxygen affinity of a Root effect Hb tends to decrease, rather than increase, as progressive oxygen molecules are bound, in contrast with the situation at higher pH. This apparent negative cooperativity of Root effect Hbs results in highly asymmetric Hill plots of oxygen binding and has been ascribed to significant differences in the pH dependence of oxygen binding to α and β chains of Root effect Hbs (90, 102). Moreover, it has been shown that allosteric effectors can not only shift the equilibrium between T- and R-states, but also alter the intrinsic affinities of the apparent T- and R-states of Root effect Hbs (102). As a result, the oxygen affinity of a Root-effect Hb at low pH can drop well below that of the T-state which is apparent at high pH, which is inconsistent with one of the key assumptions of the two-state model (77).

In a recent article (20), it was pointed out that in the absence of anionic effectors, the Root effect confers five-fold greater pH sensitivity to the Root effect Hbs of Spot and Carp relative to Hb A and even larger relative elevations of pH sensitivity of oxygenation in the presence of 0.2 M phosphate. Remarkably, these authors (20) showed that the Root effect is not evident in the redox reactions of these Root effect Hbs in either the presence or absence of phosphate. This finding rules out pH-dependent alterations in the thermodynamic properties of the heme iron, measured by the anaerobic oxidation reaction, as the basis of the Root effect. The alternative explanation supported by these results is that the elevated pH sensitivity of oxygenation of Root effect Hbs is attributable to globin-dependent steric effects that alter O2 affinity by constraining conformational fluidity, but which have little influence on electron exchange via the heme edge. This elegant mode of allosteric control can regulate oxygen affinity within a given quaternary state, in addition to modifying the T-R equilibrium. Evolution of multiple types of sequence differences that alter steric barriers to heme oxygenation could provide a general mechanism to account for the evolution of the Root effect in the structurally diverse Hbs of many species (20).

Consequences of the Redox Reactions of Hb

In the Oxidative toxicity of heme proteins sub-section, we review evidence that Hb oxidation not only affects O2 transport, but also produces superoxide and other activated-oxygen species with potentially adverse physiological effects (5, 76, 123). In a broad perspective, biochemical reactions that generate O2-containing free radicals participate in the development or promotion of cancer, heart disease, stroke, and emphysema (25, 45, 54, 55, 108, 115). In the sub-sections Autoxidation, Redox reactions of Hb with monoxygenase substrates, Redox reactions facilitated by metHb ligands, and Redox reactions of Hb with nitrite, we discuss specific mechanisms of Hb oxidation in relation to oxidative toxicity.

Oxidative toxicity of heme proteins

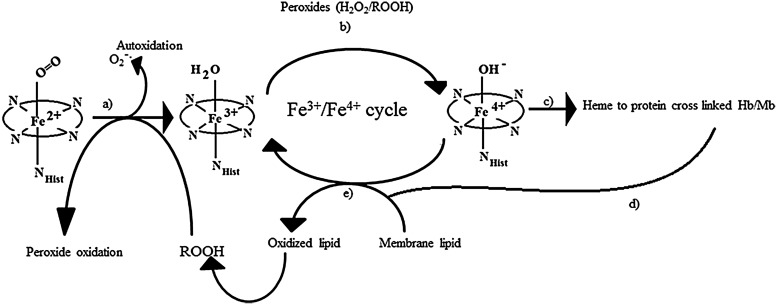

Among the least-well-documented pathophysiological consequences of Hb-free in circulation are its so-called “enzymatic” pseudo-peroxidase activities (51). These activities, which have been studied using several forms of Mb generated by site-directed mutagenesis (6), initiate and feed a cascade cycle of lipid oxidation and down-stream oxidative reactions with pathological consequences, as shown in Figure 6.

FIG. 6.

A schematic representation of pathways for lipid oxidation and pathological complications resulting from oxidation of heme proteins (Hb and Mb), adapted from Ref. (95). The various pathways shown are as follows: Auto-oxidation of oxy-ferrous Hb can produce ferric-Hb (a). This ferric Hb can enter a redox cycle in the presence of peroxide, producing ferryl Hb and protein radicals (b). These protein radicals can combine to produce cross-linked heme-protein products (c), which accelerates lipid oxidation (d). Both native and “modified” ferryl heme proteins can initiate lipid oxidation at the membrane by the abstraction of a proton that subsequently can lead to vasoconstriction, acidosis, and pathological complications (e).

The H2O2-linked oxidative reactions of Hb have been studied extensively as models for the propagation of oxidative reactions by the pseudo-peroxidase activities of Hb in cell cultures, and in animals infused with free and chemically modified Hbs (4). The redox reaction between H2O2 and ferrous Hb (Fe2+-Hb) is a two-electron process that results in the formation of ferryl Hb (Fe4+-Hb) as shown in Equation 5. As shown in Equation 6, when H2O2 reacts with ferric Hb (Fe3+-Hb), a reactive cation radical species (•HbFe4+=O) is formed as an additional reaction product (94).

|

[5] |

|

[6] |

Due to their high redox potentials, both ferryl heme and the reactive protein radicals formed via Equations 5 and 6 are capable of inducing a wide range of adverse oxidative reactions, as shown schematically in Figure 6. These reactive species connect the Hb-linked oxidative cascade to other biological molecules, as well as fuel a self-destructive pathway that involves irreversible oxidation of key amino acids on the Hb molecule (111).

Autoxidation

Autoxidation is the term used to denote the spontaneous oxidation of Hb via Equation 2 under normal aerobic conditions. In addition to the initiation of a damaging oxidative cascade as described earlier (Fig. 6), autoxidation of Hb is also responsible for rapid heme loss and protein denaturation, as these processes are kinetically favored in met-Hb (Fe3+-Hb) compared with Fe2+-Hb (67). It should be noted that these down-stream consequences of the autoxidation process are not reversible. Moreover, “bench-top” assays of Hb autoxidation cannot fully replicate the oxidative events that accompany Hb autoxidation in the more complex in vivo environment. This caveat applies not only to Hb autoxidation, but also to all “bench-top” assays of Hb's redox functions.

The mechanism and controls of the spontaneous oxidation of Hb have been debated for many years (10, 24, 67, 106, 111, 121). The rate of the autoxidation process varies appreciably among mammalian Hbs, and the reaction typically shows both pH- and temperature dependence (10, 40, 64, 111, 120, 121). Examination of Hb autoxidation rates (using both “bench-top” and in vivo assays) has revealed that the rate of the transition from ferrous to ferric Hb depends on several factors, including the O2 pressure, temperature, integrity of the red blood cells, and levels of intracellular reductants and anionic effectors. There is high sequence homology among mammalian and fish Hbs. However, the rates of autoxidation and hemin loss vary significantly among these Hbs (10). The enhanced autoxidation of Hb that has been observed at acidic pH is particularly relevant to oxidative stress in vivo, as acidosis often occurs after ischemia reperfusion or a hemolytic event.

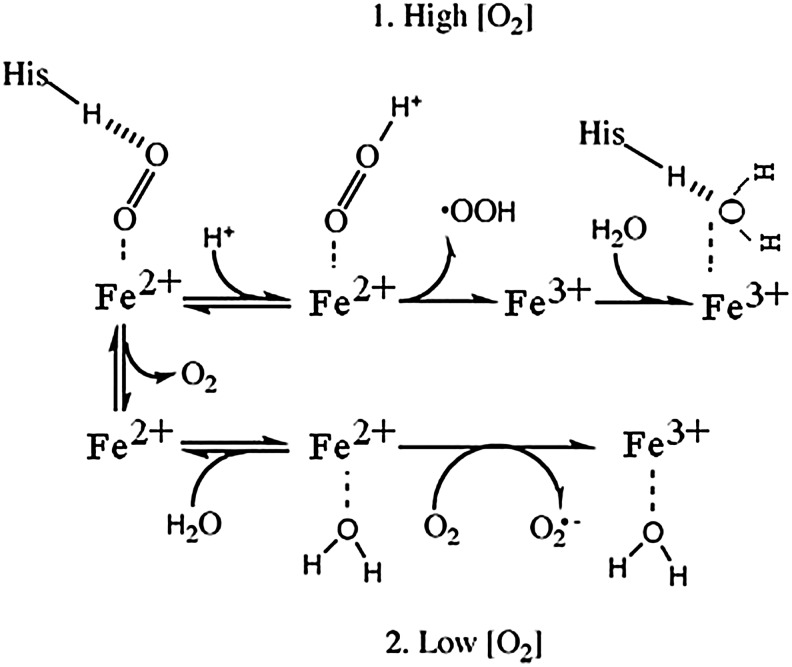

Figure 7 illustrates two pathways that are proposed to account for the fact that high O2 levels decrease the oxidation rate (10, 24). In both pathways shown, the final product is ferric Hb. At high O2, when the active site is occupied by bound O2, a relatively slow intramolecular electron transfer process allows O2 to become protonated and to dissociate as a neutral superoxide radical, HO2•. At low O2 concentrations, a faster process can occur in which molecular O2 diffuses to the active site, where it interacts with a water molecule that is weakly bound to the active site, producing superoxide radical anion. The rate of this reaction is independent of dioxygen concentration. Electron abstraction produces the superoxide anion, which then exits the heme pocket (10). A slower rate at high O2 tension in Figure 7 corresponds to a higher activation barrier (EADact Fig. 5) versus a lower activation energy barrier (EACact Fig. 5) at low O2 tension, leading to faster autoxidation. A third oxidation pathway has been suggested by Gonzalez et al. in which the oxyheme first dissociates to form deoxyheme, and the dissociated O2 accepts an electron from a penta coordinated deoxyheme in an outer-sphere mechanism (52).

FIG. 7.

Schematic representation of parallel pathways of autoxidation in heme proteins. The heme proteins are represented as Fe2+ or Fe3+ for clarity. In pathway 1, with a high concentration of O2, the bound O2 is protonated and leads to oxidation of the Fe2+ center to Fe3+, followed by dissociation of peroxide radical. Water coordinates to the Fe3+ center, which is H-bonded with distal histidine (His). In pathway 2, under low O2 partial pressure, water can replace the bound O2/ligand. Re-entry of O2 leads to oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ in the heme protein, which is facilitated by the coordinated water, and O2 leaves as a superoxide radical anion. Figure reproduced from Ref. (10) and used with permission.

Redox reactions of Hb with monoxygenase substrates

Perhaps the least appreciated of the externally induced oxidative reactions of Hb are its monoxygenase reactions, represented by Equation 7. In this simplified representation of the multi-step monoxygenase reaction, RH represents any aromatic molecule, such as aniline, that is able to enter the heme pocket and undergo a reaction.

|

[7] |

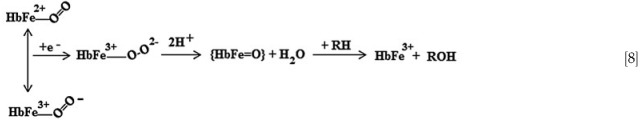

Hb's active site can accommodate many of the substrates (RH) of cytochrome P450-type reactions that make aromatic molecules, such as aniline, more soluble by creating -OH side chains. As in similar reactions catalyzed by cytochrome P450, O2 bound at the ferrous active site of Hb forms an oxyferryl complex when the protein accepts additional electrons in a bound dioxygen delocalized antibonding orbital. Activation of O2, which is critical to the monoxygenase function, is accomplished by ferryl heme formation (74). The hypothetical reaction mechanism for this process is shown in Equation 8, where {HbFe=O} represents an oxenoid intermediate which may be written as HbFe3+–Oo↔HbFe4+–O−↔HbFe5+–O2−.

Once the monoxygenase reaction has taken place, the active site is left in an oxidized condition, with the opportunity for further cyclic reactions once the active site is returned to the ferrous state by intracellular reductants.

Redox reactions facilitated by metHb ligands

A number of redox reactions of Hb are brought about by reversible or irreversible reactions with ligands that complex strongly with oxidized heme. The strong binding affinity of these ligands for the met form of Hb shifts the redox equilibrium toward the Fe3+-Hb state, compromising the O2 transport property of the protein. The role of anions in facilitating these reactions was discussed in previous reviews (121). Cyanide is perhaps the best known of the ligands that promote Hb oxidation via strong binding to the oxidized form. NO and nitrite are also ferric heme ligands (8), but their interactions with ferrous heme are much stronger. The complex of NO with ferric heme has, however, been proposed as an intermediate in some of Hb's NO-linked reactions (7, 80, 81).

Redox reactions of Hb with nitrite

Of the redox reactions catalyzed by Hb, by far, the most attention in recent years has been paid to Hb's reactions with nitrite. The ability of nitrite, present in some well waters and foods, to oxidize Hb and promote methemoglobinemia has been known for many years (67). While the complex reactions of Hb with nitrite have been the subject of many earlier investigations, it is only recently that this reaction has been highlighted in the context of possible NO-linked blood pressure control (48–50).

Under anaerobic conditions, Hb behaves functionally as an NO synthase as it undergoes reactions with nitrite. The transfer of electrons from reduced iron to nitrite, a nitrite reduction reaction, as shown in Equation 9, yields metHb and NO, with a rapid production of NOHb as the NO formed reacts with unreacted deoxy Hb.

|

[9] |

There is a linear dependence of initial rates of metHb formation on nitrite concentration and an autocatalytic time course of the redox reaction (60, 61). Although only deoxy heme catalyzes the reaction, O2 tensions that half-saturate Hb maximize the release of NO-equivalents to the vasculature, as evidenced by nitrite-induced vasorelaxation (49, 53, 75). This has been attributed to the redox potential shift associated with formation of some R-state Hb as O2 is bound (49, 53, 75). However, it is more appropriately ascribed to a shift in kinetics of the reaction than to the redox potential, which specifies the thermodynamic driving potential for heme oxidation/reduction and does not define the reaction rate (see Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of Hb oxidation section).

A more complex process of Hb oxidation that does not involve NO production occurs when nitrite reacts with oxygenated Hb. The time course has a slow initial phase that has been shown to be associated with the oxidation of ferrous heme and the formation of H2O2. The subsequent interaction between met-Hb and peroxide leads to formation of protein radicals, ferryl heme, and a progressive, autocataylytic increase in the rate of metHb formation (38).

The time course of nitrite-induced oxidation of Hb and of the NO-synthase reaction is variably affected by the nature of the Hb and the levels of O2 and allosteric effectors. As shown in Table 1, several cross-linked Hbs have significantly enhanced rates of nitrite-induced oxidation relative to Hb A (18). The T-state stabilized, low-O2-affinity cross-linked Hbs might have been expected to have slower rates of reaction with nitrite. However, their observed behavior is in keeping with previous studies indicating that these T-state stabilized Hbs have enhanced rates of transition to metHb and ferryl heme on exposure to H2O2 (5, 79, 81). Their faster rates of interaction with nitrite are also consistent with data suggesting that the conformational constraints induced by cross-linking result in more solvent-accessible heme pockets (5, 35). The results in Table 1 also show that inorganic anions and inositol hexaphosphate (IHP), effectors that lower Hb's O2 affinity, exert opposite effects on the rate of nitrite-induced oxidation. These results show that the conformation and reactivity of Hb in its physiologically important redox reactions can be variably affected by the allosteric effects of anions, and by constraints induced by cross-linking reactions (18).

Table 1.

Half Times for Nitrite-Induced Hemoglobin Oxidation

| Nitrite-induced oxidation half time (t50) in min | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.007 M Cl− | 0.2 M Cl− | 0.7 M Cl− | 600 μM IHP | ||

| Hemoglobin type | Deoxy | Oxy | Oxy | Oxy | Oxy |

| Hb A | 8.6±0.2 | 28±1.5 | 15±2 | 15±2 | 47±4 |

| Hb-DBBF | — | 18±2 | — | — | — |

| PolyHbBv | 5.7±0.2 | 18±2 | — | — | — |

| HbDex | 7.5±0.2 | 17±2 | — | — | — |

| O-R-PolyHb A | 5.6±0.2 | 18±2 | — | — | — |

Data recorded in 0.05 M bis-Tris/HCl at pH 7.5, 20°C. Half times of oxidation were observed after addition of 100-fold excess nitrite over heme. Table adapted from Ref. (18) and used with permission.

Hb-DBBF, stroma free Hb cross-linked between α-chains by DBBF; PolyHbBv, purified bovine Hb cross-linked intra and inter molecularly by glutaraldehyde; HbDex, human Hb polymer formed by inter and intra tetrameric cross-link by dextran; O-R-PolyHb A, human Hb polymer formed by inter and intra-tetrameric cross-link by O-raffinose; DBBF, Bis(3, 5-dibromosalicyl)fumarate; IHP, inositol hexaphosphate.

Molecular Controls of Oxygenation and Redox Reactions of Hb

Redox properties of structurally diverse Hbs

The allosterically controlled conformations of Hb clearly influence its redox reactions with nitrites and the formation and degradation of S-nitrosated Hb (SNO-Hb). Specifically, NO-dependent reactions involving formation of SNO-Hb have been shown to be under the control of allosteric reactions that alter the reactivity of β93Cys (8, 65). In addition, in the presence of nitrite, Hb functions as an allosteric nitrite reductase, with maximal NO generation around the intrinsic oxygen affinity (P50) of Hb, suggestive of allosteric controls of this reaction (75). It is by virtue of the differences in reactivity of Hb's R- and T-states that its reactions with nitrites and/or formation of SNO-Hb have been proposed to have specific therapeutic application during intravascular hemolysis and during administration of Hb-based blood substitutes, or even as means of reversing of storage-induced alterations in the properties of red blood cells (75). These recently proposed strategies of averting the oxidative stress associated with acellular Hb, either arising from introduction of Hb-based blood substitutes, or from hemolysis of aged stored blood, have Hb's allosteric properties as key features. The haptoglobin (Hp)-mediated protection against the toxicity of acellular Hb, which has recently been demonstrated (12), is also closely tied to Hb's allosteric properties. Hp reacts exclusively with Hb dimers (made available by dissociation of R-state Hb). Hb tetramers, which are highly stabilized in deoxy, T-state Hb, do not interact with Hp (100).

There are many Hbs with differences in the amino acid sequence where the strategic alterations in structure have resulted in rather dramatic alterations in function. Of the Hb variations associated with adverse physiological consequences, the best known is the single amino acid substitution on the β-chain at position E6 (β 6Glu to Val) that results in HbS. This substitution alters Hb's behavior in vivo and is the molecular basis of sickle cell disease (SCD) and associated circulatory problems (see Redox activity of sickle cell Hb and the mechanism of malarial defense section) (78, 97).

Allosteric controls of the oxygenation and redox reactions of Hb

Although many studies of anaerobic redox reactions have shown that Hbs stabilized in high-O2-affinity R-state conformations are typically more readily oxidized than T-state stabilized forms, the structural differences which affect heme oxygenation do not show a uniform correlation with alterations in heme redox potential (22, 24, 33, 34, 47, 72, 83, 99, 111, 118). Notably, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, IHP has a much more pronounced effect on the initial stages of Hb oxygenation than on oxidation (41). The difference is attributable to steric controls that have more influence on Hb oxygenation than on Hb oxidation. Steric effects are also involved in the significantly different effects of salts on Hb oxygenation and oxidation as salt concentrations are increased above 0.2 M (114). From 0 to 0.2 M salt, there are decreases in oxygen affinity and parallel decreases in ease of oxidation as a result of anionic stabilization of the low-affinity T-state. Selective responses of the α-chains are likely to be involved in the increased T-state stabilization, as high-affinity oxygen-linked binding sites for inorganic anions exist at the N-terminus of the human Hb α-chains (11, 15). Although increasing salt concentrations progressively lower Hb's O2 affinity, there is a dramatic reversal (decrease in E1/2) in the direction of change of the anion effect on the redox potential above 0.2 M salt. The decreases in redox potential as salt concentrations are increased above 0.2 M appear to result from salt-induced increases in solvent exposure of the heme pocket that facilitates electron withdrawal and consequent better “solvation” of the Fe3+-Hb species (114). The biphasic anion effect on Hb redox potential is potentially relevant to studies of the interactions of varied levels of nitrite anions with Hb, and the protein's nitrite reductase activity.

Steric hindrance to ligation has been clearly demonstrated in both model compounds and heme proteins by comparison of the binding of CO with more bulky homotropic ligands such as the isocyanides (85, 96, 116, 117). Similarly, as shown in studies of model heme compounds (120) and as is evident in a comparison of Figures 3 and 4, allosteric effectors can significantly alter O2-binding affinity without having significant effects on the oxidation process. Thus, from both theoretical and experimental considerations, it is evident that changes in the stereochemistry of the active site, whether brought about by a globin alteration or a constraint imposed by an allosteric effector, can alter the active-site ligand affinity without significantly altering the redox potential.

Effects of heme pocket geometry on rates of redox reactions of Hb

The importance of heme redox potential in Hb's NO synthase reactions was highlighted in recent studies of Hbs S and F (53). These Hbs, whose redox potentials are shifted toward increased ease of oxidation, showed elevated rates of nitrite reductase (NO-synthase) activity (53). However, the kinetics of the process are more relevant than the redox potentials of the participating Hbs. Many redox reactions of Hbs have rates that are only indirectly related to the thermodynamic driving potential for the transition between the ferrous and the ferric form. For example, as shown in Table 1, the rates of NO production via the reaction of nitrite with deoxy cross-linked Hbs are faster than those of unmodified deoxy Hb, in spite of the fact that they have lowered O2 affinity and have redox potentials which are indicative of reduced ease of oxidation. The faster reactions of the cross-linked Hbs with nitrite appear to arise as a result of their having more open heme pockets, which facilitates the access of nitrite to the heme sites (18).

The results of studies of the structurally distinct Hbs of the clam Lucina pectinata provide perhaps the clearest picture of how rates of Hb's redox reactions with nitrite can be controlled by accessibility of the oxidant to the active site (herein referred to as heme accessibility). Lucina pectinata is a large tropical clam that lives in the black sulfide-rich muds of mangrove swamps. Its gills harbor symbiotic bacteria that supply metabolic byproducts to the clam only when supplied with both O2 and hydrogen sulfide. Hydrogen sulfide is an environmental chemical found in mangrove swamps and elsewhere and is usually a respiratory poison that abolishes O2 transport by heme oxidation. The clam contributes to the symbiosis by producing high levels of structurally distinct Hbs in its gills. Lucina Hb I transports hydrogen sulfide, while Lucina Hb II, which is remarkably resistant to hydrogen sulfide, carries out O2 transport functions (68).

Lucina Hbs I and II were found to have similar O2-binding affinities and redox potentials. Remarkably, air-equilibrated samples of Lucina Hb I are more rapidly oxidized by nitrite than any previously studied Hb, while those of Lucina Hb II, which is resistant to hydrogen sulfide, strongly resist nitrite-induced oxidation (19). These extreme differences in rates of reaction with nitrite were found to result from differences in heme accessibility; that is, accessibility of oxidant to the redox active site. A distal-side hydrogen bonding network, including hydrogen bonding to bound O2, was shown to play an essential role in “clamming up” the active site of Lucina Hb II and preventing nitrite-induced oxidation (19).

Pivotal Questions Still Under Investigation

NO-linked redox reactions of Hb

The NO-linked redox reactions of Hb are of particular interest in light of the identification of NO as the elusive endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) that binds to the heme protein guanylate cyclase and stimulates the dilation of blood vessels (32, 46, 62, 88). The discovery of NO as EDRF poses some immediate questions with regard to NO-dependent blood pressure regulation, particularly in light of the fact that Hb is very reactive with NO, is present at high concentrations in circulating red blood cells, and is, at times, present at elevated levels as acellular Hb. A key question is whether some of the NO generated by endothelial cells is degraded, trapped, or carried to remote sites by interactions with Hb. If any of these events happen to a significant extent, how is NO-dependent normal blood pressure maintained in healthy individuals? These questions are fundamental to understanding NO-dependent regulation of blood pressure and in seeking means of dealing with adverse conditions of high and low blood pressure. In spite of significant advances in the field of NO and Hb biochemistry, these questions have only partially been answered.

NO-mediated hypoxic responses that have been attributed to Hb's redox reactions are derived from biochemical analysis, experiments carried out in isolated organs, and in a limited number of animal studies. These rather-limited studies provide the basis for currently used and proposed therapeutic applications that exploit bioactive NO released from red blood cells or even free Hb. Notable among these applications are NO-dependent reactions that have been proposed to reverse the toxicity of free Hb in circulation which results from hemolytic anemias, partial lysis of cells of stored blood, or from use of free Hb as an oxygen therapeutic (see next sub-section).

A number of laboratories have proposed that red blood cells release NO or NO equivalents into the circulation in an Hb-mediated, oxygen-dependent fashion (7, 48, 49, 60, 65, 75, 106). The postulated role of Hb in NO-linked reactions in an oxygen-sensing pathway, which could explain Hb-induced hypoxic vasodilation, is presumably driven by the R-to-T allosteric transition of Hb. In the “SNO-Hb” proposal of how this might occur (65), data were reported that showed differences between arterial and venous blood, indicative of NO transport in a cyclic fashion, similar to the O2/CO2 cycle. Data showing significant levels of SNO-Hb in red blood cells provided a rationale for how NO transport might occur, with SNO-Hb forming in the lungs and releasing NO or NO equivalents in tissues. Exposure of Hb to NO and formation of HbNO in the absence of O2 does not trigger SNO-Hb formation in either T- or R-states (39), but transfer of NO+ from intraerythrocytic S-nitrosoglutathione to the reactive thiol group of β93 Cys in the R-state of Hb could occur in the lungs, forming a limited amount of SNO-Hb. SNO-Hb could also result from formation of nitrosating agents such as NOx when NO is generated from nitrite in the presence of O2 (7, 21, 39). Deoxygenation of SNO-Hb in the microvasculature, accompanied by the reverse R-to-T process, was hypothesized to cause the release of NO equivalents. However, SNO-Hb was subsequently shown to be remarkably stable in both R and T conformations (17, 21), and could not be a significant storage form of bioactive NO due to its instability in the reductive environment of red blood cells (21, 50). In subsequent revisions of the SNO-Hb proposal, release of bioactive NO was suggested to be facilitated by Hb binding to the anion exchanger 1 (AE1) protein (Band 3) in the red blood cell membrane, with transfer of NO+ from Cysβ93 of SNO-Hb to thiols in AE1 and subsequent release (89). However, the Band 3 complex when mixed with SNO-Hb was found to be stable in both oxy and deoxy conditions (21). The possible action of low-molecular-weight thiols in red blood cells as transnitrosating agents may be found to play a role in vivo, but how NO is released in a bioactive state from SNO-Hb remains an unanswered question.

Means by which NO can be released from a Hb-rich environment is also the pivotal unresolved aspect of a second proposal for how intracellular Hb could play a role in blood pressure regulation. In this scenario, nitrite rather than SNO-Hb is proposed as the species responsible for the Hb-induced hypoxic vasodilation (75), with Hb participating in the process via its functionality as an allosteric nitrite reductase with maximal NO generation around Hb's intrinsic oxygen affinity (P50). The dependence of this enzymatic activity of Hb on hypoxia and acidosis could allow for metabolic “sensing” mechanisms that lead to maximal NO generation in ischemic/hypoxic tissues. However, to provide a mechanism for NO release from red blood cells, the nitrite reductase activity of Hb should be linked to yet another reaction that releases NO or NO equivalents. NO-containing complexes (such as the highly unstable N2O3) have been proposed as intermediates that might act directly to moderate vascular tension or be converted to bioactive NO (59).

Both of these proposals for how Hb may be involved in Hb-induced hypoxic vasodilation involve multiple Hb and NO redox intermediates. The postulated intermediates are hard to detect or measure in vivo under controlled experimental settings, and are themselves potential sources of oxidative damage. In addition, neither of these proposals provides a credible mechanism for efficient transfer of NOx equivalents from the red blood cell to the vessel wall, particularly in the face of the extremely rapid and irreversible intraerythrocytic consumption of NO by a reaction with dioxygen bound to the heme of oxyHb or by a reaction with deoxyHb (69).

Hemodynamic imbalances, manifested by blood pressure elevation at both systemic and pulmonary levels, have been documented in patients infused with cell-free Hb solutions, and in patients with SCD who have elevated levels of circulating cell-free Hb (2). Since these imbalances have been attributed to Hb-linked scavenging of NO, several strategies have been explored that focused on controlling hemodynamic imbalances after infusion of Hb-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs) by use of NO donors or by the inhibition of NO synthetic pathways. These approaches seem to blunt the NO-dependent responses that transiently increase blood pressure, but clearer experimental demonstrations of effectiveness and clinical safety are needed.

As further insight is gained into the mechanisms underlying Hb's non-oxygen-carrying functions, it is hoped that Hb forms can be engineered which have greatly reduced adverse oxidative effects and both carry and deliver NO, thus compensating for Hb-linked decreases in NO bioavailability and reversing hemodynamic imbalances that result from having cell-free Hb in circulation. To date, however, even the most imaginative strategies that control blood pressure elevation, including recombinant engineering of an NO-less reactive Hb (86), transformation of the Hb molecule into a possible NO carrier (via S-nitrosation of cysteine residues as described earlier), or enzymatically transforming Hb in the presence of nitrite into a source for NO (via its nitrite reductase functionality as described earlier) have failed to eliminate the toxicity associated with introduction of HBOCs into the circulation. Disappointing news from a recent clinical trial underlines the failure of recent approaches to control pulmonary blood pressure increases triggered by free Hb (32). The clinical trial investigated an NO-modulating strategy in patients with sickle cell anemia. The failure of the clinical trial led some leading authorities in sickle cell research and clinical management to question the utility of treating these patients with NO or its metabolites as therapeutic modalities. In fact, some went as far as questioning the existence of any association between NO scavenging by free Hb and the pathophysiology of SCD sufficient to warrant intervention with NO-based therapies (58). These approaches seem to blunt the NO-dependent responses that transiently increase blood pressure, but clearer experimental demonstrations of effectiveness and clinical safety are needed.

Redox activity of sickle cell Hb and the mechanism of malarial defense

A number of unresolved questions pertain to the ways redox reactions affect the manifestation or severity of SCD. Oxidation-related mechanisms are likely to be of direct pathophysiological relevance in people with SCD. Notably, sickle cell Hb (Hb S) has an altered redox potential (21) and autoxidizes 1.7-fold faster than Hb A in solution (58). Its enhanced rate of autoxidation has been shown to be caused in part by adventitious free iron, which has been shown to associate with Hb S but not with Hb A obtained from the very same red blood cell. Via a different mechanism, Hb S oxidizes 3.4-fold faster than Hb A on its (abnormal) interaction with membranes. Both processes result in conversion of ferrous to metHb and generation of superoxide ( ), resulting in greatly enhanced propensity for Hb denaturation with heme loss, including its transfer to membrane lipids if it is lipid-induced (58). Once heme is released from Hb, a phenomenon favored in the case of Hb S, free heme becomes cytotoxic via its redox activity (13, 93, 105). Further work is required to discover ways to counter this deleterious effect, which is offset in part by the increased expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) as discussed elsewhere (83).

), resulting in greatly enhanced propensity for Hb denaturation with heme loss, including its transfer to membrane lipids if it is lipid-induced (58). Once heme is released from Hb, a phenomenon favored in the case of Hb S, free heme becomes cytotoxic via its redox activity (13, 93, 105). Further work is required to discover ways to counter this deleterious effect, which is offset in part by the increased expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) as discussed elsewhere (83).

In a recent limited clinical trial in sickle cell patients, N-acetylcysteine was found to be effective in reducing Hb-induced oxidative stress. Notably, erythrocyte phosphatidylserine expression, which is a direct indicator of oxidative damage to erythrocyte membranes, was reduced (84).

Hb S confers a survival advantage to individuals living in endemic areas of malaria, the disease caused by Plasmodium infection. It is relevant that mice which express Hb S do not succumb to experimental cerebral malaria (43). This protective effect is exerted irrespective of parasite load, revealing that it is the presence of Hb S which confers host tolerance to Plasmodium infection (41, 43). It is known that subjects with Hb S show increased expression of HO-1 in hematopoietic cells, via a mechanism involving the transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2. CO, a byproduct of heme catabolism by HO-1 that prevents further accumulation of circulating free heme after Plasmodium infection, also reduces the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria.

Another intriguing study was reported recently that provides further evidence for a role for the redox reactions of HbS in protection against malarial infection. Within red blood cells, the presence of Hb S alters the trafficking system that directs parasite-encoded proteins to the surface of infected erythrocytes. Hb-linked oxidation products, which are enriched in Hb S erythrocytes, have been shown to inhibit actin polymerization in vitro (36). It was suggested that this alteration in cellular actin may change the internal processing of malarial proteins, thereby accounting in part for the protective role of Hb S in malaria.

Related studies have revealed similarities in erythrocytes containing Hb S and Hb C (abnormal Hb leading to anemia). These erythrocytes have dysfunctional cytoskeletons, among other abnormalities (25). Both Hb S and Hb C are relatively unstable compared with Hb A and more readily oxidize to metHb and hemichromes, which accumulate more than 10-fold over normal levels (36). Moreover, ferryl Hb, one of the Hb-linked oxidation products readily formed in human erythrocytes under conditions of oxidative stress, was shown in this study to interfere with actin remodeling, thereby preventing the malarial parasite from creating its own actin cytoskeleton within the host cell cytoplasm. This inhibitory effect could be reproduced in vitro by ferryl Hb, but not by Hb or metHb, and was dependent on the percentage of ferryl Hb in the total Hb. As a result, Maurer's clefts, irregular cytoplasmic fragments thought to aid in the parasite's life cycle, do not properly form; vesicular transport is impaired; and the export of parasite-encoded disease-mediating adhesins to the erythrocyte surface is distorted (36). This mechanism appears to explain how both Hb S and Hb C confer protection against malaria.

Hb-based blood substitutes

Oxygen therapeutics using Hb-based technology, also known as HBOCs or “blood substitutes,” have been under active development for almost 30 years (29). In spite of many promising experimental innovations both in vitro and in vivo, no clinically viable product based on free Hb for oxygen therapeutics has been approved for human use in the United States. Development of HBOCs has stalled in recent years because of problems with their safety, and most specifically with safety problems associated with uncontrolled Hb-linked oxidative side reactions as shown in Figure 6. In addition, complex biochemical changes that are introduced into the Hb molecule caused by chemical or genetic modifications present a barrier to a full understanding of how these engineered forms of free Hb operate in vivo.

Hemodynamic imbalances, as manifested by blood pressure elevation, have been noted in response to infusion of HBOCs (3). These imbalances are viewed by many as implicating Hb as a participant in a critical step of NO modulation. By creating hemodynamic imbalances, HBOCs can trigger downstream NO-dependent effects. The scavenging of NO by free Hb is not the only Hb-linked reaction that can cause hemodynamic imbalances. Other, less-studied enzymatic activities of Hb, initiated by endogenous oxidants as they react with the heme moiety of Hb, may have more extensive tissue-damaging effects than the removal of NO, which acts mainly in the microenvironment of cells (3).

Some of the most commonly reported adverse events associated with increased levels of free Hb due to pathological conditions or purposeful introduction of HBOCs have direct and/or indirect relationships to redox reactions initiated at Hb's heme centers. Adverse effects include gastrointestinal effects, pancreatic and liver enzyme elevations, cardiac involvement, inflammatory responses, neurotoxicity, and oxidative stress (3).

Two lines of experimental evidence that support the predominance of oxidative reactions of Hb in contributing to the well-documented adverse events associated with use of HBOCs come from recent studies of animals infused with unmodified cell-free Hb and with engineered forms of Hb designed for use as HBOCs. Rats, unlike guinea pigs or humans, maintain high levels of endogenous ascorbate (a reducing agent) in their circulation. Rats controlled the oxidation of infused HBOCs far better than guinea pigs infused with same HBOCs. Guinea pigs, unlike the rats used in the study, experienced marked histopathological changes in their kidneys (30). In two separate animal models, dogs and guinea pigs, introduction of Hp, a protective antioxidant, was observed to limit the toxic effects of HBOC infusion. The benefits of increased levels of Hp in dogs were first studied after glucocorticoid-mediated Hp induction (23). Separate studies in guinea pigs evaluated the ability of Hp administered pharmacologically to prevent Hb-induced hemodynamic responses and oxidative toxicity of the extravascular environment. Data obtained from both models showed definitively that Hp formed a Hb-Hp complex which attenuated the hypertensive response to free Hb exposure, and prevented Hb-induced peroxidative toxicity in extravascular compartments, such as the kidney (23).

In an in vitro follow-up investigation (28), it was shown that the avid binding of Hp to Hb results in a site-specific protection of key amino acids from the oxidizing effects of H2O2. Moreover, the Hb-Hp complex stabilized both ferryl Hb and the associated protein radicals that emanate from the heme after addition of H2O2 (35a). These species are rendered kinetically inert and are no longer able to promote oxidative damage to either the Hb of the Hb-Hp complex or neighboring molecules. The Hb-Hp complex formation also resulted in a considerable drop in the redox potential of Hb (14). This negative shift in the redox potential of the Hb-Hp complex and the longer lived ferryl state established the central elements in Hp protection against Hb-induced oxidative damage and confirmed it to be the predominant oxidative pathway operative in toxicity of Hb in vivo (14, 35a).

There have been recent setbacks on what appeared to be promising approaches to development of Hb-based technology for use as oxygen carriers or blood substitutes (4). These setbacks may spur researchers to investigate new and fundamentally different approaches for the development of a new generation of HBOCs. Nature has often used solutions for centuries that scientists benefit from discovering. Accordingly, it may prove useful to explore some of the naturally occurring mechanisms for providing anti-oxidative protection and clearing of acellular Hb as a basis of future Hb-based therapeutics (1).

Effects of free radical scavengers on the Hb-induced oxidative cascade

A pivotal question under investigation in many laboratories is whether the oxidative cascade initiated by Hb oxidation can be avoided or quenched. A promising result, suggestive that this might be possible, was the demonstration that Hb oxidation by nitrite can be significantly slowed by materials that scavenge free radicals (110).

Ascorbate, a radical scavenger, can reduce metHb and ferrylHb. The reduction occurs at different rates for varied forms of HBOCs. Notably, when the oxidized forms of Bis(3, 5-dibromosalicyl)fumarate (DBBF)-Hb and a bovine polymerized Hb (Oxyglobin™) were rapidly mixed with ascorbate, reduction of ferryl Hb back to ferric by ascorbate was found to be significantly faster for Oxyglobin (t1/2= 0.018 s) than for DBBF (t1/2= 0.13 s) (18). These findings offer important implications for clinical therapies for conditions where cell-free Hbs are present at abnormally high levels, or for improved conditions for injection of HBOCs. Further studies are needed in order to determine whether the co-administration of reducing agents such as ascorbic acid with Hb can control or reduce Hb-mediated oxidative toxicity (109).

Abbreviations Used

- AE1

anion exchanger 1

- DBBF

bis(3, 5-dibromosalicyl)fumarate

- EDRF

endothelium-derived relaxing factor

- Hb A

mature human hemoglobin

- Hb C

abnormal hemoglobin leading to anemia

- Hb F

fetal hemoglobin

- Hb S

sickle cell hemoglobin

- Hb(s)

hemoglobin(s)

- HBOC

hemoglobin based oxygen carriers

- His

histidine

- hMb

horse myoglobin

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- Hp

haptoglobin

- IHP

inositol hexaphosphate

- Mb(s)

myoglobin(s)

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- Oxyglobin

polymerized bovine Hb

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- SNO-Hb

S-nitrosated hemoglobin

Acknowledgments

A.L.C. thanks the National Science Foundation (CHE 0809466) and Duke University for financial support and the hospitality of the Santa Fe Institute during the period when this review was written.

References

- 1.Alayash AI. Haptoglobin: old protein with new functions. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alayash AI. Hemoglobin-based blood substitutes: oxygen carriers, pressor agents, or oxidants? Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:545–549. doi: 10.1038/9849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alayash AI. Oxygen therapeutics: can we tame haemoglobin? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:152–159. doi: 10.1038/nrd1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alayash AI. Setbacks in blood substitutes research and development: a biochemical perspective. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alayash AI. Fratantoni JC. Bonaventura C. Bonaventura J. Bucci E. Consequences of chemical modifications on the free radical reactions of human hemoglobin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:114–120. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alayash AI. Ryan BA. Eich RF. Olson JS. Cashon RE. Reactions of sperm whale myoglobin with hydrogen peroxide: effects of distal pocket mutations on the formation and stability of ferryl intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2029–2037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angelo M. Singel DJ. Stamler JS. An S-nitrosothiol (SNO) synthase function of hemoglobin that utilizes nitrite as a substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8366–8371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600942103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonini E. Brunori M. Hemoglobin and Myoglobin in Their Reactions with Ligands. Amsterdam-London: North Holland Publishing Company; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Appleby CA. The origin and functions of haemoglobin in plants. Sci Prog. 1992;76:365–398. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aranda R., IV Cai H. Worley CE. Levin EJ. Li R. Olson JS. Phillips GN., Jr. Richards MP. Structural analysis of fish versus mammalian hemoglobins: effect of the heme pocket environment on autooxidation and hemin loss. Proteins. 2009;75:217–230. doi: 10.1002/prot.22236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnone A. Benesch RE. Benesch R. Structure of human deoxy hemoglobin specifically modified with pyridoxal compounds. J Mol Biol. 1977;115:627–642. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baek JH. D'Agnillo F. Vallelian F. Pereira CP. Williams MC. Jia Y. Schaer DJ. Buehler PW. Hemoglobin-driven pathophysiology is an in vivo consequence of the red blood cell storage lesion that can be attenuated in guinea pigs by haptoglobin therapy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1444–1458. doi: 10.1172/JCI59770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balla J. Jacob HS. Balla G. Nath K. Vercellotti GM. Endothelial cell heme oxygenase and ferritin induction by heme proteins: a possible mechanism limiting shock damage. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1992;105:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee S. Yiping J. Siburt CJP. Abraham B. Wood F. Bonaventura C. Henkens R. Crumbliss AL. Alayash AI. Haptoglobin alters oxygenation and oxidation of hemoglobin and decreases propagation of peroxide induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beek GGMV. Zuiderweg ERP. Bruin SHD. The binding of chloride ions to ligated and unligated human hemoglobin and its influence on the Bohr effect. Eur J Biochem. 1979;99:379–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonaventura C. Crumbliss AL. Weber RE. New insights into the proton-dependent shifts in oxygen affinity of Root effect hemoglobins. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;182:245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonaventura C. Godette G. Ferruzzi G. Tesh S. Stevens RD. Henkens R. Responses of normal and sickle cell hemoglobin to S-nitroscysteine: implications for therapeutic applications of NO in treatment of sickle cell disease. Biophys Chem. 2002;98:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonaventura C. Henkens R. Alayash AI. Crumbliss AL. Allosteric effects on oxidative and nitrosative reactions of cell-free hemoglobins. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:498–505. doi: 10.1080/15216540601188546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaventura C. Henkens R. De Jesus-Bonilla W. Lopez-Garriga J. Jia Y. Alayash AI. Siburt CJ. Crumbliss AL. Extreme differences between hemoglobins I and II of the clam Lucina pectinalis in their reactions with nitrite. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1988–1995. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonaventura C. Henkens R. Friedman J. Siburt CJ. Kraiter D. Crumbliss AL. Steric factors moderate conformational fluidity and contribute to the high proton sensitivity of Root effect hemoglobins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonaventura C. Taboy CH. Low PS. Stevens RD. Lafon C. Crumbliss AL. Heme redox properties of S-nitrosated Hb A0 and Hb S. J Biol Chem. 2002;227:14557–14563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonaventura J. Bonaventura C. Sullivan B. Godette G. Hemoglobin Deer Lodge (β2His→Arg) consequences of altering the 2, 3-diphosphoglycerate binding site. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:9250–9255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boretti FS. Buehler PW. D'Agnillo F. Kluge K. Glaus T. Butt OI. Jia Y. Goede J. Pereira CP. Maggiorini M. Schoedon G. Alayash AI. Schaer DJ. Sequestration of extracellular hemoglobin within a haptoglobin complex decreases its hypertensive and oxidative effects in dogs and guinea pigs. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2271–2280. doi: 10.1172/JCI39115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brantley RE., Jr. Smerdon SJ. Wilkinson AJ. Singleton EW. Olson JS. The mechanism of autooxidation of myoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6995–7010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brawn K. Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases: Threat and defense. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1980;492:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunori M. Nitric oxide, cytochrome-c oxidase and myoglobin. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:21–23. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunori M. Alfsen A. Saggese U. Antonini E. Wyman J. Studies on the oxidation-reduction potentials of heme proteins: VII. Oxidation-reduction equilibrium of hemoglobin bound to haptoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:2950–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buehler PW. Abraham B. Vallelian F. Linnemayr C. Pereira CP. Cipollo JF. Jia Y. Mikolajczyk M. Boretti FS. Schoedon G. Alayash AI. Schaer DJ. Haptoglobin preserves the CD163 hemoglobin scavenger pathway by shielding hemoglobin from peroxidative modification. Blood. 2009;113:2578–2586. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-174466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buehler PW. Alayash AI. All hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers are not created equally. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1378–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buehler PW. D'Agnillo F. Hoffman V. Alayash AI. Effects of endogenous ascorbate on oxidation, oxygenation, and toxicokinetics of cell-free modified hemoglobin after exchange transfusion in rat and guinea pig. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:49–60. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.126409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buehler PW. Karnaukhova E. Gelderman MP. Alayash AI. Blood aging, safety, and transfusion: capturing the “radical” menace. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1713–1728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bunn HF. Nathan DG. Dover GJ. Hebbel RP. Platt OS. Rosse WF. Ware RE. Pulmonary hypertension and nitric oxide depletion in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;116:687–692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carver TE. Brantley RE. Singleton EW. Arduini RM. Quillin ML. Phillips GN. Olson JS. A novel site-directed mutant of myoglobin with an unusually high O2 affinity and low autooxidation rate. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14443–14450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang CK. Traylor TG. Kinetics of oxygen and carbon monoxide binding to synthetic analogs of the myoglobin and hemoglobin active sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1166–1170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chevalier A. Guillochon D. Nedjar N. Piot J. Daniel MWV. Glutaraldehyde effect on hemoglobin: evidence for an ion environment modification based on electron paramagnetic resonance and Mossbauer spectroscopies. Biochem Cell Biol. 1990;68:813–818. doi: 10.1139/o90-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a.Cooper CE. Schaer DJ. Buehler PW. Wilson MT. Reeder BJ. Silkstone G. Svistunenko DA. Bulow L. Alayash AI. Haptoglobin binding stabilizes hemoglobin ferryl iron and the globin radical on tyrosine β145. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:2264–2273. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cyrklaff M. Sanchez CP. Kilian N. Bisseye C. Simpore J. Frischknecht F. Lanzer M. Hemoglobins S and C interfere with actin remodeling in Plasmodium falciparum–infected erythrocytes. Science. 2011;334:1283–1286. doi: 10.1126/science.1213775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Sanctis D. Pesce A. Nardini M. Bolognesi M. Bocedi A. Ascenzi P. Structure-function relationships in the growing hexa-coordinate hemoglobin sub-family. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:643–651. doi: 10.1080/15216540500059640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doyle MP. Herman JG. Dykstra RL. Autocatalytic oxidation of hemoglobin induced by nitrite: activation and chemical inhibition. J Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1:145–153. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fago A. Crumbliss AL. Peterson J. Pearce L. Bonaventura C. The Case of the reappearing nitrosylhemoglobin: reversible spectral changes suggestive of heme redox reactions reflect changes in NO-heme geometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12087–12092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2032603100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faivre B. Menu P. Labrude P. Vigneron C. Hemoglobin autooxidation/oxidation mechanisms and methemoglobin prevention or reduction processes in the bloodstream. Literature review and outline of autooxidation reaction. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 1998;26:17–26. doi: 10.3109/10731199809118943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faulkner KM. Bonaventura C. Crumbliss AL. A Spectroelectrochemical method for differentiation of steric and electronic effects in hemoglobins and myoglobins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13604–13612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.23.13604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faulkner KM. Bonaventura C. Crumbliss AL. A spectroelectrochemical method for evaluating factors which regulate the redox potential of hemoglobins. Inorg Chim Acta. 1994;226:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreira A. Marguti I. Bechmann I. Jeney V. Chora Â. Palha NR. Rebelo S. Henri A. Beuzard Y. Soares MP. Sickle hemoglobin confers tolerance to Plasmodium infection. Cell. 2011;145:398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frey AD. Farrés J. Bollinger CJT. Kallio PT. Bacterial hemoglobins and flavohemoglobins for alleviation of nitrosative stress in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4835–4840. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4835-4840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridovich I. The biology of oxygen radicals. Science. 1978;201:875–880. doi: 10.1126/science.210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furchgott RF. Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geibel J. Cannon J. Campbell D. Traylor TG. Model compounds for R-state and T-state hemoglobins. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:3575–3585. [Google Scholar]